Tethrippon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

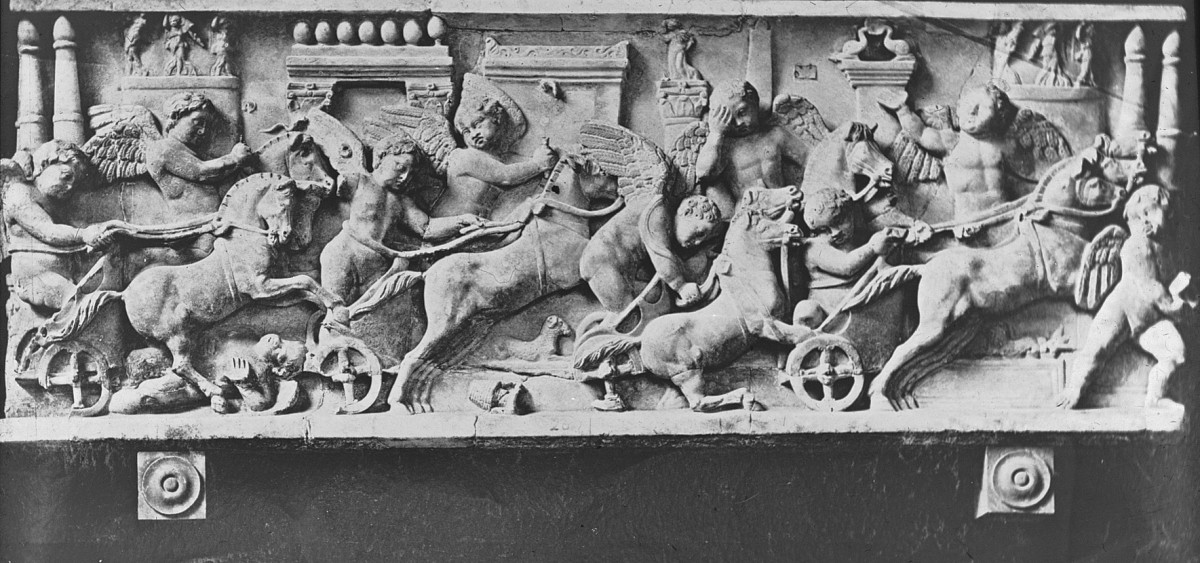

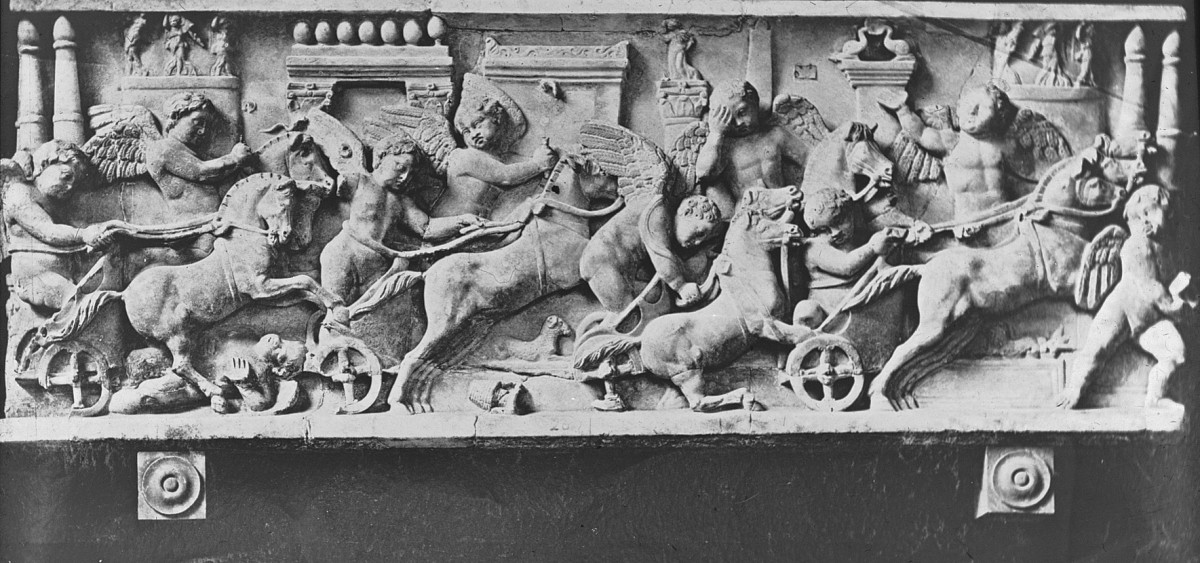

Chariot racing (, ''harmatodromía''; ) was one of the most popular

The Olympic Games were traditionally founded in 776 BC, by the Eleans, a wealthy, prestigious horse-owning aristocracy.

The Olympic Games were traditionally founded in 776 BC, by the Eleans, a wealthy, prestigious horse-owning aristocracy.  Races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps. The most immediate and challenging aspect of the races for drivers, judges and stewards was ensuring a fair start, and keeping false starts and crushes to a minimum. Then as now, the marshalling of over-excited racehorses could prove a major difficulty. Various mechanical devices were used to reduce the likelihood of human error. Portable starting gates (''hyspleges'', singular: hysplex), employed a tight cord in a wooden frame, loosened to drop forwards and start the race. According to Pausanias, the chariot furthest from the start-line began to move, followed by the rest in sequence, so that when the final gate was opened, all the chariots would be in motion at the starting line. A bronze eagle (a sign of

Races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps. The most immediate and challenging aspect of the races for drivers, judges and stewards was ensuring a fair start, and keeping false starts and crushes to a minimum. Then as now, the marshalling of over-excited racehorses could prove a major difficulty. Various mechanical devices were used to reduce the likelihood of human error. Portable starting gates (''hyspleges'', singular: hysplex), employed a tight cord in a wooden frame, loosened to drop forwards and start the race. According to Pausanias, the chariot furthest from the start-line began to move, followed by the rest in sequence, so that when the final gate was opened, all the chariots would be in motion at the starting line. A bronze eagle (a sign of

The Romans probably borrowed chariot technology and racing track design from the

The Romans probably borrowed chariot technology and racing track design from the

The ''spina'' carried lap-counters, in the form of eggs or dolphins; the eggs were suggestive of

The ''spina'' carried lap-counters, in the form of eggs or dolphins; the eggs were suggestive of

The best charioteers could earn a great deal of prize money, in addition to their contracted subsistence pay. The prize money for up to fourth place was advertised beforehand, with first place winning up to 60,000 sesterces. Detailed records were kept of drivers' performances, and the names, breeds and pedigrees of famous horses. Betting on results was widespread, among all classes. Most races involved four-horse chariots (''

The best charioteers could earn a great deal of prize money, in addition to their contracted subsistence pay. The prize money for up to fourth place was advertised beforehand, with first place winning up to 60,000 sesterces. Detailed records were kept of drivers' performances, and the names, breeds and pedigrees of famous horses. Betting on results was widespread, among all classes. Most races involved four-horse chariots (''

Most Roman chariot drivers, and many of their supporters, belonged to one of four factions; social and business organisations that raised money to sponsor the races. The factions offered security to their members in return for their loyalty and contributions, and were headed by a patron or patrons. Each faction employed a large staff to serve and support their charioteers. Every circus seems to have independently followed the same model of organisation, including the four-colour naming system: Red, White, Blue, and Green. Senior managers () were usually of equestrian class. Investors were often wealthy, but of lower social status; driving a racing chariot was thought a very low class occupation, beneath the dignity of any citizen, but making money from it was truly disgraceful, so investors of high social status usually resorted to negotiations discreetly through agents, rather than risk losing reputation, status and privilege through ''

Most Roman chariot drivers, and many of their supporters, belonged to one of four factions; social and business organisations that raised money to sponsor the races. The factions offered security to their members in return for their loyalty and contributions, and were headed by a patron or patrons. Each faction employed a large staff to serve and support their charioteers. Every circus seems to have independently followed the same model of organisation, including the four-colour naming system: Red, White, Blue, and Green. Senior managers () were usually of equestrian class. Investors were often wealthy, but of lower social status; driving a racing chariot was thought a very low class occupation, beneath the dignity of any citizen, but making money from it was truly disgraceful, so investors of high social status usually resorted to negotiations discreetly through agents, rather than risk losing reputation, status and privilege through ''

9

By his time, there were four factions; the Reds were dedicated to

Most races and wins were team efforts, results of co-operation between charioteers of the same faction, but victories won in single races were the most highly esteemed by drivers and their public. Charioteers followed a ferociously competitive, charismatic profession, routinely risked violent death, and aroused a compulsive, even morbid reverence among their followers. A supporter of the Red faction is said to have thrown himself on the funeral pyre of his favourite charioteer. More usually, some charioteers and supporters tried to enlist supernatural help by covertly burying

Most races and wins were team efforts, results of co-operation between charioteers of the same faction, but victories won in single races were the most highly esteemed by drivers and their public. Charioteers followed a ferociously competitive, charismatic profession, routinely risked violent death, and aroused a compulsive, even morbid reverence among their followers. A supporter of the Red faction is said to have thrown himself on the funeral pyre of his favourite charioteer. More usually, some charioteers and supporters tried to enlist supernatural help by covertly burying

The horses, too, could become celebrities; they were purpose-bred and were trained relatively late, from 5 years old. The Romans favoured particular native breeds from

The horses, too, could become celebrities; they were purpose-bred and were trained relatively late, from 5 years old. The Romans favoured particular native breeds from

The ''diversium'' was unique to Byzantine chariot racing, a formal rematch between the winner and a loser, in which the competing charioteers drove each other's team and chariot. A winning charioteer could thus win twice over, driving the same horse team that he had defeated earlier, virtually eliminating mere chance or better horses as the deciding factors in both victories. In Byzantine chariot racing, the expected standards of professional athleticism were very high. Competitors were sometimes assigned to age categories, though very loosely; youths under approximately 17 (described as "beardless"), young men (17–20), and adult men over 20; but skill counted more than age, or stamina. In some circumstances, the charioteers themselves performed formal, ritualised mimes, or dances, which won them fame and adulation Preparation for races could involve ritualised public dialogues between charioteers, imperial officials and emperors, a prescribed liturgy of questions, answers, and processional orders of precedence. Each race required the emperor's consent.

The ''diversium'' was unique to Byzantine chariot racing, a formal rematch between the winner and a loser, in which the competing charioteers drove each other's team and chariot. A winning charioteer could thus win twice over, driving the same horse team that he had defeated earlier, virtually eliminating mere chance or better horses as the deciding factors in both victories. In Byzantine chariot racing, the expected standards of professional athleticism were very high. Competitors were sometimes assigned to age categories, though very loosely; youths under approximately 17 (described as "beardless"), young men (17–20), and adult men over 20; but skill counted more than age, or stamina. In some circumstances, the charioteers themselves performed formal, ritualised mimes, or dances, which won them fame and adulation Preparation for races could involve ritualised public dialogues between charioteers, imperial officials and emperors, a prescribed liturgy of questions, answers, and processional orders of precedence. Each race required the emperor's consent.

In the eastern provinces, and Constantinople itself, the earliest evidence for colour factions is from AD 315, coincident with the extension of imperial authority into local government and public life. The cost of financing the races was split between the factions, the state, the Emperors, and senior officials. The annually appointed consuls were obliged to personally fund their own inaugural games.

Members of racing factions (known as

In the eastern provinces, and Constantinople itself, the earliest evidence for colour factions is from AD 315, coincident with the extension of imperial authority into local government and public life. The cost of financing the races was split between the factions, the state, the Emperors, and senior officials. The annually appointed consuls were obliged to personally fund their own inaugural games.

Members of racing factions (known as

Perseus Project

*

Perseus Project

* Pindar. ''Olympian Odes – Olympian 1''. See original text i

Perseus Project

* Pindar. ''Pythian Odes – Pythian 5''. See original text i

Perseus Project

* * *

Latin library

Chariot Races (United Nations of Roma Victrix (UNRV) History – Roman Empire)

* * ttp://www.sportsinantiquity.com Pasko Varnica – Sports In Antiquity {{Authority control Ancient Olympic sports Ancient Roman sports Horse racing

ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

, and Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

sports. In Greece, chariot

A chariot is a type of vehicle similar to a cart, driven by a charioteer, usually using horses to provide rapid Propulsion, motive power. The oldest known chariots have been found in burials of the Sintashta culture in modern-day Chelyabinsk O ...

racing played an essential role in aristocratic funeral games

Funeral games are athletic competitions held in honor of a recently deceased person. The celebration of funeral games was common to a number of ancient civilizations. Athletics and games such as wrestling are depicted on Sumerian statues dating ...

from a very early time. With the institution of formal races and permanent racetracks, chariot racing was adopted by many Greek states and their religious festivals. Horses and chariots were very costly. Their ownership was a preserve of the wealthiest aristocrats, whose reputations and status benefitted from offering such extravagant, exciting displays. Their successes could be further broadcast and celebrated through commissioned odes and other poetry.

In standard Greek racing practise, each chariot held a single driver and was pulled by four horses, or sometimes two. Drivers and horses risked serious injury or death through collisions and crashes; this added to the excitement and interest for spectators. Most charioteers were slaves or contracted professionals. While records almost invariably credit victorious owners and their horses for winning, their drivers are often not mentioned at all. In the ancient Olympic Games

The ancient Olympic Games (, ''ta Olympia''.), or the ancient Olympics, were a series of Athletics (sport), athletic competitions among representatives of polis, city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at ...

, and other Panhellenic Games

Panhellenic Games is the collective term for four separate religious festivals held in ancient Greece that became especially well known for the athletic competitions they included. The four festivals were: the Ancient Olympic Games, Olympic Games, ...

, chariot racing was one of the most important equestrian events, and could be watched by unmarried women. Married women were banned from watching any Olympic events but a Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

n noblewoman is known to have trained horse-teams for the Olympics and won two races, one of them as driver.

In ancient Rome, chariot racing was the most popular of many subsidised public entertainments, and was an essential component in several religious festivals. Roman chariot drivers had very low social status, but were paid a fee simply for taking part. Winners were celebrated and well paid for their victories, regardless of status, and the best could earn more than the wealthiest lawyers and senators. Racing team managers may have competed for the services of particularly skilled drivers and their horses. The drivers could race as individuals, or under team colours: Blue, Green, Red or White. Spectators generally chose to support a single team, and identify themselves with its fortunes. Private betting on the races raised large sums for the teams, drivers and wealthy backers. Generous imperial subsidies of "bread and circuses

"Bread and circuses" (or "bread and games"; from Latin: ''panem et circenses'') is a metonymic phrase referring to superficial appeasement. It is attributed to Juvenal (''Satires'', Satire X), a Roman poet active in the late first and early seco ...

" kept the Roman masses fed, entertained and distracted. Organised violence between rival racing factions was not uncommon, but it was generally contained. Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

and later Byzantine emperors

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

, mistrustful of private organisations as potentially subversive, took control of the teams, especially the Blues and Greens, and appointed officials to manage them.

Chariot racing faded in importance in the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

after the fall of Rome

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

; the last known race there was staged in the Circus Maximus in 549, by the Ostrogoth

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

ic king, Totila

Totila, original name Baduila (died 1 July 552), was the penultimate King of the Ostrogoths, reigning from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of the Gothic War (535–554), Gothic War, recovering b ...

. In the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, the traditional Roman chariot-racing factions continued to play a prominent role in mass entertainment, religion and politics for several centuries. Supporters of the Blue teams vied with supporters of the Greens for control of foreign, domestic and religious policies, and imperial subsidies for themselves. Their displays of civil discontent and disobedience culminated in an indiscriminate slaughter of Byzantine citizenry by the military in the Nika riots

The Nika riots (), Nika revolt or Nika sedition took place against Byzantine emperor Justinian I in Constantinople over the course of a week in 532 AD. They are often regarded as the most violent riots in the city's history, with nearly half of ...

. Thereafter, rising costs and a failing economy saw the gradual decline of Byzantine chariot racing.

Early Greece

Images onpottery

Pottery is the process and the products of forming vessels and other objects with clay and other raw materials, which are fired at high temperatures to give them a hard and durable form. The place where such wares are made by a ''potter'' is al ...

show that chariot racing existed in thirteenth century BC Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainla ...

. The first literary reference to a chariot race is in Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's poetic account of the funeral games for Patroclus

In Greek mythology, Patroclus (generally pronounced ; ) was a Greek hero of the Trojan War and an important character in Homer's ''Iliad''. Born in Opus, Patroclus was the son of the Argonaut Menoetius. When he was a child, he was exiled from ...

, in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', combining practices from the author's own time (c. 8th century) with accounts based on a legendary past.Homer. ''The Iliad'', 23.257–23.652. The participants in this race were drawn from leading figures among the Greeks; Diomedes

Diomedes (Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. ''Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary''. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.) or Diomede (; ) is a hero in Greek mythology, known for his participation in the Trojan ...

of Argos, the poet Eumelus, the Achaean prince Antilochus

In Greek mythology, Antilochus (; Ancient Greek: Ἀντίλοχος ''Antílokhos'') was a prince of Pylos and one of the Achaeans in the Trojan War. He was the youngest prince to command troops.

Family

Antilochus was the son of King Nestor ...

, King Menelaus

In Greek mythology, Menelaus (; ) was a Greek king of Mycenaean (pre- Dorian) Sparta. According to the ''Iliad'', the Trojan war began as a result of Menelaus's wife, Helen, fleeing to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris. Menelaus was a central ...

of Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

, and the hero

A hero (feminine: heroine) is a real person or fictional character who, in the face of danger, combats adversity through feats of ingenuity, courage, or Physical strength, strength. The original hero type of classical epics did such thin ...

Meriones. The race, which was one lap around the stump of a tree, was won by Diomedes, who received a slave

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

woman and a cauldron

A cauldron (or caldron) is a large cookware and bakeware, pot (kettle) for cooking or boiling over an open fire, with a lid and frequently with an arc-shaped hanger and/or integral handles or feet. There is a rich history of cauldron lore in r ...

as his prize. A chariot race also was said to be the event that founded the Olympic Games

The modern Olympic Games (Olympics; ) are the world's preeminent international Olympic sports, sporting events. They feature summer and winter sports competitions in which thousands of athletes from around the world participate in a Multi-s ...

; according to one legend, mentioned by Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

, King Oenomaus

In Greek mythology, King Oenomaus (also Oenamaus; , ''Oinómaos'') of Pisa (Greece), Pisa, was the father of Hippodamia (daughter of Oenomaus), Hippodamia and the son of Ares. His name ''Oinomaos'' denotes a wine man.

Family

Oenomaeus' mother ...

challenged suitors for his daughter Hippodamia to a race, but was defeated by Pelops

In Greek mythology, Pelops (; ) was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region (, lit. "Pelops' Island"). He was the son of Tantalus and the father of Atreus.

He was venerated at Olympia, where his cult developed into the founding myth of the ...

, who founded the Games in honour of his victory.

Olympic Games

The Olympic Games were traditionally founded in 776 BC, by the Eleans, a wealthy, prestigious horse-owning aristocracy.

The Olympic Games were traditionally founded in 776 BC, by the Eleans, a wealthy, prestigious horse-owning aristocracy. Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

, the earliest source for the Olympics, includes chariot racing among their five foundation events. Much later, Pausanias claims that chariot races were added only from 680 BC, and that the games were extended from one day to two days to accommodate them. In this tradition, the foot race of a stadion (approximately 600 feet) offered the greater prestige. Votive offerings associated with Olympic victories include horses and chariots. The single horse race (the ) was a late arrival at the games, dropped early in their history. The major chariot-races of the Olympic and other Panhellenic Games, were four-horse (, ) and two-horse (, ) events.

Pausanias describes the Olympic hippodrome of the second century AD, when Greece was part of the Roman Empire. The perimeter groundplan, southeast of the sanctuary itself, was approximately 780 meters long and 320 meters wide. Competitors raced from the starting-place counter-clockwise around the nearest (western) turning post, then turned at the eastern turning post and headed back west. The number of circuits varied according to the event. Spectators could watch from natural embankments to the north, and artificial embankments to the south and east. A place on the western side of the north bank was reserved for the judges. Pausanias does not describe a central dividing barrier at Olympia, but archaeologist Vikatou presumes one.

Pausanias offers several theories regarding the origins of an object named Taraxippus ("Horse-disturber"), an ancient round altar, tomb or '' Heroon'' embedded within one of the entrance-ways to the track. It was thought to be malevolent, as it terrified horses for no apparent reason when they raced past it, and was a major cause of crashes. Pausanias reports that consequently "the charioteers offer sacrifice, and pray that Taraxippus may show himself propitious". It might simply have marked the most dangerous and difficult section of track, at the semi-circular end. Pausanias describes very similar, identically named places in other Greek hippodromes. Their name may have been an epithet

An epithet (, ), also a byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) commonly accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a real or fictitious person, place, or thing. It is usually literally descriptive, as in Alfred the Great, Suleima ...

of Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

, patron deity of horses and horse-racing.

Races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps. The most immediate and challenging aspect of the races for drivers, judges and stewards was ensuring a fair start, and keeping false starts and crushes to a minimum. Then as now, the marshalling of over-excited racehorses could prove a major difficulty. Various mechanical devices were used to reduce the likelihood of human error. Portable starting gates (''hyspleges'', singular: hysplex), employed a tight cord in a wooden frame, loosened to drop forwards and start the race. According to Pausanias, the chariot furthest from the start-line began to move, followed by the rest in sequence, so that when the final gate was opened, all the chariots would be in motion at the starting line. A bronze eagle (a sign of

Races began with a procession into the hippodrome, while a herald announced the names of the drivers and owners. The tethrippon consisted of twelve laps. The most immediate and challenging aspect of the races for drivers, judges and stewards was ensuring a fair start, and keeping false starts and crushes to a minimum. Then as now, the marshalling of over-excited racehorses could prove a major difficulty. Various mechanical devices were used to reduce the likelihood of human error. Portable starting gates (''hyspleges'', singular: hysplex), employed a tight cord in a wooden frame, loosened to drop forwards and start the race. According to Pausanias, the chariot furthest from the start-line began to move, followed by the rest in sequence, so that when the final gate was opened, all the chariots would be in motion at the starting line. A bronze eagle (a sign of Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

, who was patron of the Olympic games) was raised to start the race, and at each lap, a bronze dolphin (a sign of Poseidon) was lowered. The central pair of horses did most of the heavy pulling, via the yoke. The flanking pair pulled and guided, using their traces. Horse teams were highly trained, and tractable. Greek aficionadoes thought mares the best horses for chariot racing.

Owners and charioteers

In most cases, the owner and the driver of the Greek racing chariot were different persons. In 416 BC, theAthenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

general Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

had seven chariots in the race, and came in first, second, and fourth; evidently, he could not have been racing all seven chariots himself.Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

. ''History of the Peloponnesian War

The ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' () is a historical account of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), which was fought between the Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) and the Delian League (led by Classical Athens, Athens). The account, ...

'', 6.16.2. Chariot teams were costly to own and train, and the case of Alcibiades shows that for the wealthy, this was an effective and honourable form of self-publicity; they were not expected to risk their own lives. On the other hand, they were not necessarily dishonoured when they did. The poet Pindar

Pindar (; ; ; ) was an Greek lyric, Ancient Greek lyric poet from Thebes, Greece, Thebes. Of the Western canon, canonical nine lyric poets of ancient Greece, his work is the best preserved. Quintilian wrote, "Of the nine lyric poets, Pindar i ...

praised Herodotes for driving his own chariot, "using his own hands rather than another's".

Entries were exclusively Greek, or claimed to be so. Philip II of Macedon

Philip II of Macedon (; 382 BC – October 336 BC) was the king (''basileus'') of the ancient kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedonia from 359 BC until his death in 336 BC. He was a member of the Argead dynasty, founders of the ...

, pre-eminent through his conquest of most Greek states and self-promotion as a divinity, entered his horse and chariot teams in several major pan-Hellenic events, and won several. He celebrated the fact on his coinage, claiming it as divine confirmation of his legitimacy as Greek overlord.

Women could win races through ownership, though there was a ban on the participation of married women as competitors or even spectators at the Olympics, supposedly on pain of death; this was not typical of Greek festivals in general, and there is no consistent record of this ban, or the penalty's enforcement. The Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

n Cynisca, daughter of Archidamus II, entered and won the Olympic chariot race, twice as owner and trainer, and at least once as driver.

Most charioteers were slaves or hired professionals. Drivers and their horses needed strength, skill, courage, endurance and prolonged, intensive training. Like jockeys, charioteers were ideally slight of build, and therefore often young, but unlike jockeys, they were also tall. The names of very few charioteers are known from the Greek racing circuits, Victory songs, epigrams and other monuments routinely omit the names of winning drivers.

The chariots themselves resembled war chariots, essentially wooden two-wheeled carts with an open back, though by this time chariots were no longer used in battle. Charioteers stood throughout the race. They traditionally wore only a sleeved garment called a ''xystis'', which would have offered at least some protection from crashes and dust. It fell to the ankles and was fastened high at the waist with a plain belt. Two straps that crossed high at the upper back prevented the ''xystis'' from "ballooning" during the race The body of the chariot rested on the axle, so the ride was bumpy. The most exciting parts of the chariot race, at least for the spectators, were the turns at the ends of the hippodrome. These turns were dangerous and sometimes deadly. In a full-sized racing stadium, the chariots could reach high speeds along the straights, then overturn or be crushed along with their horses and driver by the following chariots as they wheeled around the post. Driving into an opponent to make him crash was technically illegal, but most crashes were accidental and often unavoidable. In Homer's account of Patroclus' funeral games, Antilochus

In Greek mythology, Antilochus (; Ancient Greek: Ἀντίλοχος ''Antílokhos'') was a prince of Pylos and one of the Achaeans in the Trojan War. He was the youngest prince to command troops.

Family

Antilochus was the son of King Nestor ...

inflicts such a crash on Menelaus

In Greek mythology, Menelaus (; ) was a Greek king of Mycenaean (pre- Dorian) Sparta. According to the ''Iliad'', the Trojan war began as a result of Menelaus's wife, Helen, fleeing to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris. Menelaus was a central ...

.

Pan-Hellenic festivals

Race winners were celebrated throughout the Greek festival circuit, both on their own account and on behalf of their cities. In the classical era, other great festivals emerged inAsia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, Magna Graecia

Magna Graecia refers to the Greek-speaking areas of southern Italy, encompassing the modern Regions of Italy, Italian regions of Calabria, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, and Sicily. These regions were Greek colonisation, extensively settled by G ...

, and the mainland, providing the opportunity for cities to compete for honour and renown, and for their athletes to gain fame and riches. Apart from the Olympics, the most notable were the Isthmian Games

Isthmian Games or Isthmia (Ancient Greek: Ἴσθμια) were one of the Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were named after the Isthmus of Corinth, where they were held. As with the Nemean Games, the Isthmian Games were held both the year be ...

in Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, the Nemean Games

The Nemean Games ( or Νέμεια) were one of the four Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece, and were held at Nemea every two years (or every third).

With the Isthmian Games, the Nemean Games were held both the year before and the year after th ...

, the Pythian Games

The Pythian Games () were one of the four Panhellenic Games of Ancient Greece. Founded circa the 6th century BCE, the festival was held in honor of the god Apollo and took place at his sanctuary in Delphi to commemorate the mytho-historic slayin ...

in Delphi, and the Panathenaic Games

The Panathenaic Games () were held every four years in Athens in Ancient Greece from 566 BC to the 3rd century AD. These Games incorporated religious festival, ceremony (including prize-giving), athletic competitions, and cultural events hosted ...

in Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, where the winner of the four-horse chariot race was awarded 140 amphorae

An amphora (; ; English ) is a type of container with a pointed bottom and characteristic shape and size which fit tightly (and therefore safely) against each other in storage rooms and packages, tied together with rope and delivered by land ...

of olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

, a highly valued commodity. Prizes elsewhere included corn in Eleusis

Elefsina () or Eleusis ( ; ) is a suburban city and Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Athens metropolitan area. It belongs to West Attica regional unit of Greece. It is located in the Thriasio Plain, at the northernmost ...

, bronze shields in Argos, and silver vessels in Marathon

The marathon is a long-distance foot race with a distance of kilometres ( 26 mi 385 yd), usually run as a road race, but the distance can be covered on trail routes. The marathon can be completed by running or with a run/walk strategy. There ...

. Winning Greek athletes, no matter their social status, were greatly honoured by their own communities. Chariot racing at the Panathenaic Games included a two-man event, the ''apobatai'', in which one of the team was armoured, and periodically leapt off the moving chariot, ran alongside it, then leapt back on again. The second charioteer took the reins when the ''apobates'' jumped out; in the catalogues of winners, the names of both these athletes are given. Images of this contest show warriors, armed with helmets and shields, perched on the back of their racing chariots. Some scholars believe that the event preserved traditions of Homeric warfare.

Roman chariot racing

The Romans probably borrowed chariot technology and racing track design from the

The Romans probably borrowed chariot technology and racing track design from the Etruscans

The Etruscan civilization ( ) was an ancient civilization created by the Etruscans, a people who inhabited Etruria in List of ancient peoples of Italy, ancient Italy, with a common language and culture, and formed a federation of city-states. Af ...

, who in turn had borrowed them from the Greeks. Rome's public entertainments were also influenced directly by Greek examples. Chariot racing as a feature of Roman is attested in Rome's foundation myths, and on 66 of the 177 days of religious festival

A religious festival is a time of special importance marked by adherents to that religion. Religious festivals are commonly celebrated on recurring cycles in a calendar year or lunar calendar. The science of religious rites and festivals is kno ...

games scheduled in a late Roman Calendar of 354. Races were held as part of triumphal processions, foundation anniversary rites and funeral games subsidised by magnates during the Regal and Republican eras, and by the emperors during the imperial era. According to Roman legend, Rome in its earliest days was faced with a lack of marriagable women. Romulus

Romulus (, ) was the legendary founder and first king of Rome. Various traditions attribute the establishment of many of Rome's oldest legal, political, religious, and social institutions to Romulus and his contemporaries. Although many of th ...

, the city's founder, invited the Sabine

The Sabines (, , , ; ) were an Italic people who lived in the central Apennine Mountains (see Sabina) of the ancient Italian Peninsula, also inhabiting Latium north of the Anio before the founding of Rome.

The Sabines divided int ...

people to celebrate the Consualia, honouring the grain-god Consus

In ancient Roman religion, the god Consus was the protector of grains. He was represented by a grain seed. His altar ''( ara)'' was located at the first ''meta'' of the Circus Maximus. It was either underground, or according to other sources, co ...

with horse races and chariot races at the Circus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian language, Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot racing, chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine Hill, Avent ...

. While the Sabines were enjoying the spectacle, Romulus and his men seized the Sabine women. The women eventually married their captors, and were instrumental in persuading Sabines and Romans to unite as one people. Chariot racing thus played a part in Rome's foundation myth and local politics.

Consuls were obliged to subsidise races at the beginning and end of their annual terms, as a sort of tax on their office and a gift to the people of Rome. Races on January 1 accompanied the renewal of loyalty vows; emperors gave annual games on the anniversary of their succession, and on their own and other imperial birthdays.

Chariot races were preceded by a parade () that featured the charioteers, music, costumed dancers, and gilded images of the gods, headed by Victoria, goddess of victory. These images were placed on dining couches, which were arranged on a viewing platform () to observe the races, which were nominally held in their honour. The sponsor or of the races shared the with these divine images. In the imperial era, the in the Circus Maximus was directly connected to the imperial palace, on the Palatine Hill.

Several deities had permanent temples, shrines or images on the dividing barrier ( or ) of the circus. While the entertainment value of chariot races tended to overshadow any sacred purpose, in late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

the Church Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

still saw them as a traditional "pagan" practice and advised Christians

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the world. The words '' Christ'' and ''C ...

not to participate. Soon after the end of the Roman Empire in the West, the influential Christian scholar, administrator and historian Cassiodorus

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator (c. 485 – c. 585), commonly known as Cassiodorus (), was a Christian Roman statesman, a renowned scholar and writer who served in the administration of Theodoric the Great, king of the Ostrogoths. ''Senato ...

describes chariot racing as an instrument of the Devil.

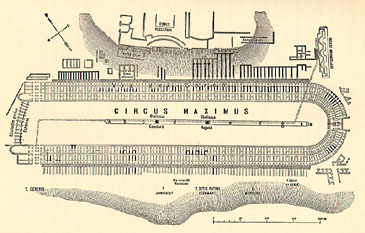

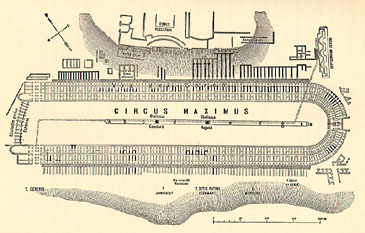

Roman circuses

Most cities had at least one dedicated chariot racing circuit. The city of Rome had several; its main centre was theCircus Maximus

The Circus Maximus (Latin for "largest circus"; Italian language, Italian: ''Circo Massimo'') is an ancient Roman chariot racing, chariot-racing stadium and mass entertainment venue in Rome, Italy. In the valley between the Aventine Hill, Avent ...

which developed on the natural slopes and valley (the '' Vallis Murcia'') between the Palatine Hill

The Palatine Hill (; Classical Latin: ''Palatium''; Neo-Latin: ''Collis/Mons Palatinus''; ), which relative to the seven hills of Rome is the centremost, is one of the most ancient parts of the city; it has been called "the first nucleus of the ...

and Aventine Hill

The Aventine Hill (; ; ) is one of the Seven Hills on which ancient Rome was built. It belongs to Ripa, the modern twelfth ''rione'', or ward, of Rome.

Location and boundaries

The Aventine Hill is the southernmost of Rome's seven hills. I ...

. It had a vast seating capacity; Boatwright estimates this as 150,000 before its rebuilding under Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, and 250,000 under Trajan

Trajan ( ; born Marcus Ulpius Traianus, 18 September 53) was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier ...

. According to Humphrey, the higher seating estimate is traditional but excessive, and even at its greatest capacity, the circus probably accommodated no more than about 150,000. It was Rome's earliest and greatest circus. Its basic form and footprint were thought more or less coeval with the city's foundation, or with Rome's earliest Etruscan kings. Julius Caesar rebuilt it around 50 BC to a length of about and width of . It had a semi-circular end, and a semi-open, slightly angled end where the chariots lined up across the track to begin the race, each enclosed within a cell known as a ''carcere'' ("prison") behind a spring-loaded gate. These were functionally equivalent to the Greek ''hysplex'' but were further staggered to accommodate a median barrier, known originally as a ''euripus'' (canal) but much later as the ''spina'' (spine). When the chariots were ready the ''editor'', usually a high-status magistrate, dropped a white cloth; all the gates sprang open at the same time, allowing a fair start for all participants. Races were run counter-clockwise; starting positions were allocated by lottery.

The ''spina'' carried lap-counters, in the form of eggs or dolphins; the eggs were suggestive of

The ''spina'' carried lap-counters, in the form of eggs or dolphins; the eggs were suggestive of Castor and Pollux

Castor and Pollux (or Polydeuces) are twin half-brothers in Greek and Roman mythology, known together as the Dioscuri or Dioskouroi.

Their mother was Leda, but they had different fathers; Castor was the mortal son of Tyndareus, the king of ...

, the mythic dioscuri

Castor and Pollux (or Polydeuces) are twin half-brothers in Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology, known together as the Dioscuri or Dioskouroi.

Their mother was Leda (mythology), Leda, but they had different fathers; Castor was the mortal ...

, one human and one divine. They were born from an egg, divine patrons of horsemen and the Equestrian order

The (; , though sometimes referred to as " knights" in English) constituted the second of the property/social-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an ().

Descript ...

. Dolphins were thought to be the swiftest of all creatures; they symbolised Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun. It is the List of Solar System objects by size, fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 t ...

, god of the sea, earthquakes and horses.

The ''spina'' bore water-feature elements, blended with decorative and architectural features. It eventually became very elaborate, with temples, statues and obelisks and other forms of art, though the addition of these multiple adornments obstructed the view of spectators on the trackside's lower seats, which were close to the action. At each end of the spina was a '' meta'', or turning point, consisting of three large gilded columns.

Spectators

Seats in the Circus were free for the poor, and either free or subsidised for the mass of citizens (plebs

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Etymology

The precise origins of the gro ...

), whose lack of involvement in late Republican and Imperial politics was compensated, as far as Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ; 55–128), was a Roman poet. He is the author of the '' Satires'', a collection of satirical poems. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, but references in his works to people f ...

was concerned, by an endless supply of handouts and entertainments, or ''panem et circenses'' ("bread and circuses

"Bread and circuses" (or "bread and games"; from Latin: ''panem et circenses'') is a metonymic phrase referring to superficial appeasement. It is attributed to Juvenal (''Satires'', Satire X), a Roman poet active in the late first and early seco ...

"). The seating nearest the track was reserved for senators, the rows behind them for equites

The (; , though sometimes referred to as " knights" in English) constituted the second of the property/social-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an ().

Descript ...

and the remainder for everyone else. The better-off could pay for shaded seats with a better view. The Vestal virgins

In Religion in ancient Rome, ancient Rome, the Vestal Virgins or Vestals (, singular ) were Glossary of ancient Roman religion#sacerdos, priestesses of Vesta (mythology), Vesta, virgin goddess of Rome's sacred hearth and its flame.

The Vestals ...

occupied their own privileged seating, close to the track. Men and women were supposed to occupy segregated seating but the "law of the place" allowed most to sit together, which for the Augustan poet Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

presented opportunities for seduction. The circus was one of few places where the populace could assemble in vast numbers, and exercise the freedom of speech associated with theatre factions and claques, voicing support or criticism of their rulers and each other.

The races

The charioteers had to keep to their own lanes for the first two laps. Then they were free to jockey for position, cutting across the paths of their competitors, moving as close to the ''spina'' as they could, and whenever possible forcing their opponents to find another, much longer route forwards. Every team included a ''hortator'', who rode horseback and signalled their faction's charioteers to help them navigate the dangers of the track. Roman drivers wrapped the reins round their waist, and steered using their body weight; with the reins looped around their torsos, they could lean from one side to the other to direct the horses' movement while keeping the hands free "for the whip and such". A driver who became entangled in a crash risked being trampled or dragged along the track by his own horses; charioteers carried a curved knife (''falx'') to cut their reins, and wore helmets and other protective gear. Spectacular crashes in which the chariot was destroyed and the charioteer and horses were incapacitated were called ''naufragia,'' (a "shipwreck").quadriga

A quadriga is a car or chariot drawn by four horses abreast and favoured for chariot racing in classical antiquity and the Roman Empire. The word derives from the Latin , a contraction of , from ': four, and ': yoke. In Latin the word is almos ...

e''), or less often, two-horse chariots (''bigae''). Just to display the skill of the driver and his horses, up to ten horses could be yoked to a single chariot. The ''quadriga'' races were the most important and frequent.

Frequency and laps

Magnates and emperors courted popularity by staging and subsidising as many races as they could, as often as possible. In Rome, races usually lasted 7 laps, or even 5, rather than the typical 12 laps of the Greek race. Some emperors were spendthrift enthusiasts;Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), also called Gaius and Caligula (), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Augustus' granddaughter Ag ...

sponsored 10–12 races a day, Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

sponsored 20–24 a day. Commodus

Commodus (; ; 31 August 161 – 31 December 192) was Roman emperor from 177 to 192, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father Marcus Aurelius and then ruling alone from 180. Commodus's sole reign is commonly thought to mark the end o ...

once held and subsidised 30 races in just 2 hours of a single afternoon; Dio Cassius

Lucius Cassius Dio (), also known as Dio Cassius ( ), was a Roman historian and senator of maternal Greek origin. He published 80 volumes of the history of ancient Rome, beginning with the arrival of Aeneas in Italy. The volumes documented the ...

predicted that such extravagance could only lead to government bankruptcy. In a previous century, the emperor Domitian

Domitian ( ; ; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was Roman emperor from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavian dynasty. Described as "a r ...

had managed to squeeze an extraordinary 100 races into a single afternoon, presumably by drastically lowering the number of laps from the standard 7. Twenty four races in a single day became the norm, until the slow collapse of Rome's economy in the West, when costs rose, sponsors were lost and racetracks were abandoned. In the 4th century AD, 24 races were held every day on 66 days each year. By the end of that century, public entertainments in Italy had come to an end in all but a few towns. The Circus Maximus was still adequately maintained for use, though for what purposes is uncertain. The last known beast-hunt there was in 523. The last recorded race there was in 549 AD, staged by the Ostrogoth

The Ostrogoths () were a Roman-era Germanic peoples, Germanic people. In the 5th century, they followed the Visigoths in creating one of the two great Goths, Gothic kingdoms within the Western Roman Empire, drawing upon the large Gothic populatio ...

ic king, Totila

Totila, original name Baduila (died 1 July 552), was the penultimate King of the Ostrogoths, reigning from 541 to 552 AD. A skilled military and political leader, Totila reversed the tide of the Gothic War (535–554), Gothic War, recovering b ...

; whether this was a display of horsemanship or a chariot-race is not known.

Factions

Most Roman chariot drivers, and many of their supporters, belonged to one of four factions; social and business organisations that raised money to sponsor the races. The factions offered security to their members in return for their loyalty and contributions, and were headed by a patron or patrons. Each faction employed a large staff to serve and support their charioteers. Every circus seems to have independently followed the same model of organisation, including the four-colour naming system: Red, White, Blue, and Green. Senior managers () were usually of equestrian class. Investors were often wealthy, but of lower social status; driving a racing chariot was thought a very low class occupation, beneath the dignity of any citizen, but making money from it was truly disgraceful, so investors of high social status usually resorted to negotiations discreetly through agents, rather than risk losing reputation, status and privilege through ''

Most Roman chariot drivers, and many of their supporters, belonged to one of four factions; social and business organisations that raised money to sponsor the races. The factions offered security to their members in return for their loyalty and contributions, and were headed by a patron or patrons. Each faction employed a large staff to serve and support their charioteers. Every circus seems to have independently followed the same model of organisation, including the four-colour naming system: Red, White, Blue, and Green. Senior managers () were usually of equestrian class. Investors were often wealthy, but of lower social status; driving a racing chariot was thought a very low class occupation, beneath the dignity of any citizen, but making money from it was truly disgraceful, so investors of high social status usually resorted to negotiations discreetly through agents, rather than risk losing reputation, status and privilege through ''infamia

In ancient Rome, (''in-'', "not", and ''fama'', "reputation") was a loss of legal or social standing. As a technical term in Roman law, was juridical exclusion from certain protections of Roman citizenship, imposed as a legal penalty by a ce ...

''. No contemporary source describes these factions as official, but unlike many unofficial organisations in Rome, they were evidently tolerated as useful and effective rather than feared as secretive and potentially subversive.

Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

claims that there were originally just two factions, White and Red, sacred to winter and summer respectively.Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

. '' De Spectaculis''9

By his time, there were four factions; the Reds were dedicated to

Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

, the Whites to the Zephyrus

In Greek mythology and religion, Zephyrus () (), also spelled in English as Zephyr (), is the god and personification of the West wind, one of the several wind gods, the Anemoi. The son of Eos (the goddess of the dawn) and Astraeus, Zephyrus is t ...

, the Greens to Mother Earth or spring, and the Blues to the sky and sea or autumn. Each faction could enter up to three chariots in a race. Members of the same faction often collaborated against the other entrants, for example to force them to crash into the ''spina'' (a legal and encouraged tactic). The driver's clothing was color-coded in accordance with his faction, which would help distant spectators to keep track of the race's progress.

The emperor Domitian

Domitian ( ; ; 24 October 51 – 18 September 96) was Roman emperor from 81 to 96. The son of Vespasian and the younger brother of Titus, his two predecessors on the throne, he was the last member of the Flavian dynasty. Described as "a r ...

created two new factions, the Purples and Golds, but they vanished from the record very soon after his death. The Blues and the Greens gradually became the most prestigious factions, supported by emperors and the populace alike. Blue versus Green clashes sometimes broke out during the races. The Reds and Whites are seldom mentioned in the literature, but their continued activity is documented in inscriptions and in curse tablets

A curse tablet (; ) is a small tablet with a curse written on it from the Greco-Roman world. Its name originated from the Greek and Latin words for "pierce" and "bind". The tablets were used to ask the gods, place spirits, or the deceased to perfo ...

.

Roman charioteers

Charioteers occupied a peculiar position in Roman society. If originally citizens, their chosen career made '' infames'' of them, denying them many of the privileges, protections and dignities of full citizenship. Undertakers, prostitutes and pimps, butchers, executioners, and heralds were considered infamous, for various reasons; but although gladiators, actors, charioteers and any others who earned a living on stage, arena or racetrack were ''infames'', the best of them could earn popular and elite support that verged on adoration, and near-fabulous wealth if not respectability.Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ; 55–128), was a Roman poet. He is the author of the '' Satires'', a collection of satirical poems. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, but references in his works to people f ...

bewailed that the earnings of the charioteer Lacerta were a hundred times more than a lawyer's fee. Emperors who took the reins as charioteer, or promoted drivers to elite status or freely mixed with ''arenarii''—as did Caligula

Gaius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (31 August 12 – 24 January 41), also called Gaius and Caligula (), was Roman emperor from AD 37 until his assassination in 41. He was the son of the Roman general Germanicus and Augustus' granddaughter Ag ...

, Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

and Elagabalus

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Sextus Varius Avitus Bassianus, 204 – 13 March 222), better known by his posthumous nicknames Elagabalus ( ) and Heliogabalus ( ), was Roman emperor from 218 to 222, while he was still a teenager. His short r ...

, for example—were also notoriously "bad" rulers. Two jurists of the later imperial era, and some modern scholars, argue against the legal status of charioteers as ''infames'', on the grounds that athletic competitions were not mere entertainment but "seemed useful" as honourable displays of Roman strength and ''virtus

() was a specific virtue in ancient Rome that carried connotations of valor, masculinity, excellence, courage, character, and worth, all perceived as masculine strengths. It was thus a frequently stated virtue of Roman emperors, and was perso ...

''.

Most Roman charioteers started their careers as slaves, who had neither reputation nor honour to lose. Of more than 200 dedications to named charioteers catalogued by , more than half are of unknown social status. Of the remainder, 66 are slaves, 14 are freedmen, 13 either slaves or freedmen and only one a freeborn citizen.

All race competitors, regardless of their social status or whether they completed the race, were paid a driver's fee. Slave-charioteers could not lawfully own property, including money, but their masters could pay them regardless, or retain all or some accumulated driving fees and winnings on their behalf, as the price of their eventual manumission

Manumission, or enfranchisement, is the act of freeing slaves by their owners. Different approaches to manumission were developed, each specific to the time and place of a particular society. Historian Verene Shepherd states that the most wi ...

. While most freed slave-charioteers would have become clients of their former master, some would have earned more than enough to buy their freedom outright, assuming they survived that long. Scorpus won over 2,000 races before being killed in a collision at the ''meta'' when he was about 27 years old. The charioteer Florus' tomb inscription describes him as ''infans'' (not adult). Gaius Appuleius Diocles won 1,462 out of 4,257 races for various teams during his exceptionally long and lucky career. When he retired at the age of 42, his lifetime winnings reportedly totalled 35,863,120 sesterces (HS), not counting driver's fees. His personal share of this is unknown but Vamplew calculates that even if Diocles' personal winnings were only a tenth part of the declared prize money, this would have yielded him an average annual income of 150,000 HS.

Most races and wins were team efforts, results of co-operation between charioteers of the same faction, but victories won in single races were the most highly esteemed by drivers and their public. Charioteers followed a ferociously competitive, charismatic profession, routinely risked violent death, and aroused a compulsive, even morbid reverence among their followers. A supporter of the Red faction is said to have thrown himself on the funeral pyre of his favourite charioteer. More usually, some charioteers and supporters tried to enlist supernatural help by covertly burying

Most races and wins were team efforts, results of co-operation between charioteers of the same faction, but victories won in single races were the most highly esteemed by drivers and their public. Charioteers followed a ferociously competitive, charismatic profession, routinely risked violent death, and aroused a compulsive, even morbid reverence among their followers. A supporter of the Red faction is said to have thrown himself on the funeral pyre of his favourite charioteer. More usually, some charioteers and supporters tried to enlist supernatural help by covertly burying curse tablets

A curse tablet (; ) is a small tablet with a curse written on it from the Greco-Roman world. Its name originated from the Greek and Latin words for "pierce" and "bind". The tablets were used to ask the gods, place spirits, or the deceased to perfo ...

at or near the track, appealing to spirits and deities of the underworld for the success of their favourites or disaster for their opponents; a common practise among Romans of all classes though like all magic, strictly illegal, and punishable by death.

Some of the most talented and successful charioteers were suspected of winning through the illicit agency of dark forces. Ammianus Marcellinus

Ammianus Marcellinus, occasionally anglicized as Ammian ( Greek: Αμμιανός Μαρκελλίνος; born , died 400), was a Greek and Roman soldier and historian who wrote the penultimate major historical account surviving from antiquit ...

, writing during Valentinian's reign (AD 364–375), describes various cases of chariot drivers prosecuted for witchcraft or the procurement of spells. One charioteer was beheaded for having his young son trained in witchcraft to help him win his races; and another burnt at the stake for practising witchcraft.

Horses

The horses, too, could become celebrities; they were purpose-bred and were trained relatively late, from 5 years old. The Romans favoured particular native breeds from

The horses, too, could become celebrities; they were purpose-bred and were trained relatively late, from 5 years old. The Romans favoured particular native breeds from Hispania

Hispania was the Ancient Rome, Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two Roman province, provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divide ...

and north Africa. One of Diocles' horses, named Cotynus, raced with him in various teams 445 times, alongside Abigeius, a treasured "trace" horse. A chariot's "trace" horses partly pulled the chariot and partly guided it, as flankers to the central pair, who were yoked to the chariot and provided both speed and power. A left-side trace horse's steady performance could mean the difference between victory and disaster; mares were thought the steadiest. Left-side trace horses were the closest to the ''spina'', and are most likely to be named in the race record. Another key performer in a standard ''quadriga'' race was the right-hand yoke-horse. Celebrity horses named in Diocles' extraordinary record of 445 races and more than 100 wins in a year include Pompeianus, Lucidus and Galata.

Byzantine context

Constantine I

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

(r. 306–337) refounded the eastern Greek city of Byzantium as a "New Rome", to serve as the administrative center of the eastern half of the Empire, and renamed it Constantinople. He replaced or restored the city's chariot-racing circuit (''hippodrome''), which had been provided by Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

. As a Christian emperor, or at least one with Christian leanings, Constantine supported and financed Constantinople's chariot racing infrastructure and overheads in preference to gladiator

A gladiator ( , ) was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gladiators were volunteers who risked their ...

ial combat, which he considered a vestige of paganism

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

. A possibility of spiritual damage through the witnessing of traditional public spectacles had concerned Christian apologists since at least Tertullian

Tertullian (; ; 155 – 220 AD) was a prolific Early Christianity, early Christian author from Roman Carthage, Carthage in the Africa (Roman province), Roman province of Africa. He was the first Christian author to produce an extensive co ...

's time. The Olympic Games were eventually ended by Emperor Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. He won two civil wars and was instrumental in establishing the Nicene Creed as the orthodox doctrine for Nicene C ...

(r. 379–395) in 393, perhaps in a move to suppress paganism and promote Christianity. Gladiator contests were eventually abandoned, but chariot racing and theatrical entertainments remained popular. The Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a place/building for Christian religious activities and praying

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian comm ...

did not, or perhaps could not, prevent them, although prominent Christian writers attacked them.

Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

's reformed legal code specifically prohibits drivers from placing curses on their opponents, and invites their co-operation in bringing offenders before the authorities, rather than acting like assassins or vigilantes. This not only reiterates a very longstanding prohibition of witchcraft throughout the Empire but confirms a reputation that charioteers had for living at the very edge of the law, for violent thefts, blackmail and bullying as debt collectors on their masters' behalf, and an easy-going criminality that could extend to the murder of opponents and enemies, disguised as rough but rightful justice.

A sixth-seventh century Byzantine graffito in the Hagia Sophia shows a charioteer named Samonas, performing a victory lap. The graffito, no earlier than 537, includes an engraved cross to seek God's help for the charioteer. Samonas is otherwise unknown.

Several earlier Byzantine charioteers are known by name or race records, six of them through short, laudatory verse epigrams

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word derives from the Greek (, "inscription", from [], "to write on, to inscribe"). This literary device has been practiced for over two millennia. ...

; namely, Anastasius; Julianus of Tyre; Faustinus and his son Constantinus; Uranius; and Porphyrius. Among these, the single epigram to Anastasius offers very little personal information, but Porphyrius is the subject of thirty-four. He is described as the best charioteer of his time; and as the only charioteer known to have won the ''diversium'' twice in one day.

The ''diversium'' was unique to Byzantine chariot racing, a formal rematch between the winner and a loser, in which the competing charioteers drove each other's team and chariot. A winning charioteer could thus win twice over, driving the same horse team that he had defeated earlier, virtually eliminating mere chance or better horses as the deciding factors in both victories. In Byzantine chariot racing, the expected standards of professional athleticism were very high. Competitors were sometimes assigned to age categories, though very loosely; youths under approximately 17 (described as "beardless"), young men (17–20), and adult men over 20; but skill counted more than age, or stamina. In some circumstances, the charioteers themselves performed formal, ritualised mimes, or dances, which won them fame and adulation Preparation for races could involve ritualised public dialogues between charioteers, imperial officials and emperors, a prescribed liturgy of questions, answers, and processional orders of precedence. Each race required the emperor's consent.

The ''diversium'' was unique to Byzantine chariot racing, a formal rematch between the winner and a loser, in which the competing charioteers drove each other's team and chariot. A winning charioteer could thus win twice over, driving the same horse team that he had defeated earlier, virtually eliminating mere chance or better horses as the deciding factors in both victories. In Byzantine chariot racing, the expected standards of professional athleticism were very high. Competitors were sometimes assigned to age categories, though very loosely; youths under approximately 17 (described as "beardless"), young men (17–20), and adult men over 20; but skill counted more than age, or stamina. In some circumstances, the charioteers themselves performed formal, ritualised mimes, or dances, which won them fame and adulation Preparation for races could involve ritualised public dialogues between charioteers, imperial officials and emperors, a prescribed liturgy of questions, answers, and processional orders of precedence. Each race required the emperor's consent.

Byzantine racing factions

In the eastern provinces, and Constantinople itself, the earliest evidence for colour factions is from AD 315, coincident with the extension of imperial authority into local government and public life. The cost of financing the races was split between the factions, the state, the Emperors, and senior officials. The annually appointed consuls were obliged to personally fund their own inaugural games.

Members of racing factions (known as

In the eastern provinces, and Constantinople itself, the earliest evidence for colour factions is from AD 315, coincident with the extension of imperial authority into local government and public life. The cost of financing the races was split between the factions, the state, the Emperors, and senior officials. The annually appointed consuls were obliged to personally fund their own inaugural games.

Members of racing factions (known as deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or (, plural: ''demoi'', δήμοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Classical Athens, Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside existed in the 6th century BC and earlier, bu ...

s), were a minority among chariot racing enthusiasts as a whole. In Byzantium as elsewhere, racing fans cheered on their favorite charioteers, and sought out the company of like-minded supporters. Charioteers could change their factional allegiance but their fans did not necessarily follow them. Semi-permanent alliances of Blues (, ''Vénetoi'') and Greens (, ''Prásinoi'') overshadowed the Whites (, ''Leukoí'') and Reds (, ''Rhoúsioi''). In the 5th century, the outstanding Byzantine charioteer Porphyrius raced as a "Blue" or a "Green" at various times; he was celebrated by each faction, and by the reigning Emperor, and was honoured with several imperially subsidised monuments on a grand scale in the Hippodrome. While the racing factions, their supporters and the populace at large were overwhelmingly composed of commoners, as in Rome, Cameron (1976) sees no justification for the description of any Byzantine racing faction, racing sponsor or factional ideology as "populist", nor the conflicts between factions and authorities as expressions of "class conflict" or religious squabling on a grand scale. The urban mass disturbances that characterise much of Byzantium's early history were not associated with racing factions until the 5th century, when the imperial government appointed managers of both the Circus races and the Theatres, responsible for the production and performance of the chants, theatrical displays and lavish religious ceremonies that accompanied imperial court rituals and chariot races. The acclamations of emperors and of winning charioteers employed much the same triumphalist language, symbolism, honours and pledges of allegiance. From around the mid-fifth century, the support and approval of the factions in confirming the legitimacy of emperors became a formal requirement. The factions were represented as loyal commoners, or "the people".