Tanystropheus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Tanystropheus'' (~ 'long' + 'hinged') is an extinct

Vertebrate Palaeontology at Milano University. Retrieved 2007-02-19. In 1886, Francesco Bassani interpreted the unusual tricuspid fossil as a

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were found in the mid-19th century. They included eight large vertebrae from the Upper

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were found in the mid-19th century. They included eight large vertebrae from the Upper

''Tanystropheus'' was one of the longest known non-archosauriform archosauromorphs. Vertebrae referred to "''T. conspicuus''" may correspond to an animal up to five or six meters (16.4 to 20 feet'')'' in length''.'' ''T. hydroides'' was around the same size, with the largest specimens at an estimated length of 5.25 meters (17.2 feet). ''T. longobardicus'' was significantly smaller, with an absolute maximum size of two meters (6.6 feet). Despite the large size of some ''Tanystropheus'' species, the animal was lightly built. One mass estimate used crocodiles as a density guideline for a 3.6 meter (11.8 feet)-long model of a ''Tanystropheus'' skeleton. For a ''Tanystropheus'' individual of that length, the weight estimate varied between 32.9 kg (72.5 lbs) and 74.8 kg (164.9 lbs), depending on the volume estimation method. This was significantly lighter than crocodiles of the same length, and more similar to large lizards.

''Tanystropheus'' was one of the longest known non-archosauriform archosauromorphs. Vertebrae referred to "''T. conspicuus''" may correspond to an animal up to five or six meters (16.4 to 20 feet'')'' in length''.'' ''T. hydroides'' was around the same size, with the largest specimens at an estimated length of 5.25 meters (17.2 feet). ''T. longobardicus'' was significantly smaller, with an absolute maximum size of two meters (6.6 feet). Despite the large size of some ''Tanystropheus'' species, the animal was lightly built. One mass estimate used crocodiles as a density guideline for a 3.6 meter (11.8 feet)-long model of a ''Tanystropheus'' skeleton. For a ''Tanystropheus'' individual of that length, the weight estimate varied between 32.9 kg (72.5 lbs) and 74.8 kg (164.9 lbs), depending on the volume estimation method. This was significantly lighter than crocodiles of the same length, and more similar to large lizards.

The parietals are strongly modified in ''T. hydroides''. They are fused into a single X-shaped bone, somewhat resembling the parietals of erythrosuchids. This shape may have resulted from fusion between the parietals' anterolateral processes (front branches) and the postfrontals, which are separate bones in ''T. longobardicus'' but not apparent in ''T. hydroides''. A prominent pineal foramen is positioned near the straight contact with the frontals, one of the few similarities with ''T. longobardicus''. Strong supratemporal fossae excavate into the outer edge of the parietal and define a low

The parietals are strongly modified in ''T. hydroides''. They are fused into a single X-shaped bone, somewhat resembling the parietals of erythrosuchids. This shape may have resulted from fusion between the parietals' anterolateral processes (front branches) and the postfrontals, which are separate bones in ''T. longobardicus'' but not apparent in ''T. hydroides''. A prominent pineal foramen is positioned near the straight contact with the frontals, one of the few similarities with ''T. longobardicus''. Strong supratemporal fossae excavate into the outer edge of the parietal and define a low  ''T. hydroides'' is a rare example of an early archosauromorph with a three-dimensionally preserved braincase. The basioccipital (rear lower component of the braincase) was small, with inset basitubera (vertical plates connecting to neck muscles) linked by a transverse ridge, similar to allokotosaurs and archosauriforms. The parabasisphenoid (front lower component) is less specialized; it lies flat and tapers forwards to a blade-like cultriform process. The rear part of the bone has a deep triangular excavation (known as a median pharyngeal recess) on its underside, flanked by low crests and a pair of small basipterygoid processes (knobs connecting to the pterygoid). The remainder of the braincase is fully fused together into a strongly ossified composite bone, and its constituents must be estimated by comparison to other reptiles. The exoccipitals, which mostly encompass the

''T. hydroides'' is a rare example of an early archosauromorph with a three-dimensionally preserved braincase. The basioccipital (rear lower component of the braincase) was small, with inset basitubera (vertical plates connecting to neck muscles) linked by a transverse ridge, similar to allokotosaurs and archosauriforms. The parabasisphenoid (front lower component) is less specialized; it lies flat and tapers forwards to a blade-like cultriform process. The rear part of the bone has a deep triangular excavation (known as a median pharyngeal recess) on its underside, flanked by low crests and a pair of small basipterygoid processes (knobs connecting to the pterygoid). The remainder of the braincase is fully fused together into a strongly ossified composite bone, and its constituents must be estimated by comparison to other reptiles. The exoccipitals, which mostly encompass the  In the lower jaw, the dentaries meet each other at a robust

In the lower jaw, the dentaries meet each other at a robust

The most recognisable feature of ''Tanystropheus'' is its hyperelongate neck, equivalent to the combined length of the body and tail. ''Tanystropheus'' has 13 cervical (neck) vertebrae, most of which are massive, though the two closest to the head are smaller and less strongly developed. The

The most recognisable feature of ''Tanystropheus'' is its hyperelongate neck, equivalent to the combined length of the body and tail. ''Tanystropheus'' has 13 cervical (neck) vertebrae, most of which are massive, though the two closest to the head are smaller and less strongly developed. The

There are 12 dorsal (torso) vertebrae. This count is very low among early archosauromorphs: ''Protorosaurus'' has up to 19, ''Prolacerta'' has 18, and ''Macrocnemus'' has 17. ''Tanystropheuss dorsals are smaller and less specialized than the cervicals. Though their neural spines are taller than those of the cervicals, they are still rather short. The dorsal ribs are double-headed close to the shoulder and single-headed in the rest of the torso, sitting on stout

There are 12 dorsal (torso) vertebrae. This count is very low among early archosauromorphs: ''Protorosaurus'' has up to 19, ''Prolacerta'' has 18, and ''Macrocnemus'' has 17. ''Tanystropheuss dorsals are smaller and less specialized than the cervicals. Though their neural spines are taller than those of the cervicals, they are still rather short. The dorsal ribs are double-headed close to the shoulder and single-headed in the rest of the torso, sitting on stout

The pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) has a fairly standard form shared with other tanystropheids. The

The pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) has a fairly standard form shared with other tanystropheids. The

The components of the

The components of the

In the 1980s, the advent of

In the 1980s, the advent of

The diet of ''Tanystropheus'' has been strongly debated in the past, though most recent studies consider it a

The diet of ''Tanystropheus'' has been strongly debated in the past, though most recent studies consider it a

While long necks were a successful evolutionary strategy for many marine reptile clades during the Mesozoic, they also increased the animals' vulnerability to predation. Spiekman and Mujal (2023) investigated two ''Tanystropheus'' fossils (PIMUZ T 2819 and PIMUZ T 3901), each consisting solely of a skull attached to an articulated partial neck. PIMUZ T 2819 (a large specimen of ''T. hydroides'') is preserved up to cervical vertebra 10, which is splintered by punctures and scoring. The shape of the marks indicate that the neck was severed in two rapid bites by a predator attacking from above and behind. A similar predation attempt occurred against PIMUZ T 3901 (the Meride Limestone specimen of ''T. longobardicus''), which was bitten at cervical 5 and severed at cervical 7. The authors further suggested that since the decapitation occurred in the mid-section of the neck, this was likely an optimal target due to its distance from the head and the muscular base of the neck. While many contemporary marine reptiles were capable of attacking PIMUZ T 3901, only the largest predators of the Besano Formation could have attacked PIMUZ T 2819. '' Paranothosaurus giganteus'', '' Cymbospondylus buchseri'', and '' Helveticosaurus zollingeri'' are all candidates for the latter case.

While long necks were a successful evolutionary strategy for many marine reptile clades during the Mesozoic, they also increased the animals' vulnerability to predation. Spiekman and Mujal (2023) investigated two ''Tanystropheus'' fossils (PIMUZ T 2819 and PIMUZ T 3901), each consisting solely of a skull attached to an articulated partial neck. PIMUZ T 2819 (a large specimen of ''T. hydroides'') is preserved up to cervical vertebra 10, which is splintered by punctures and scoring. The shape of the marks indicate that the neck was severed in two rapid bites by a predator attacking from above and behind. A similar predation attempt occurred against PIMUZ T 3901 (the Meride Limestone specimen of ''T. longobardicus''), which was bitten at cervical 5 and severed at cervical 7. The authors further suggested that since the decapitation occurred in the mid-section of the neck, this was likely an optimal target due to its distance from the head and the muscular base of the neck. While many contemporary marine reptiles were capable of attacking PIMUZ T 3901, only the largest predators of the Besano Formation could have attacked PIMUZ T 2819. '' Paranothosaurus giganteus'', '' Cymbospondylus buchseri'', and '' Helveticosaurus zollingeri'' are all candidates for the latter case.

Impressions on the frontal bones of ''Tanystropheus longobardicus'' fossils indicate that that species at least had a bulbous

Impressions on the frontal bones of ''Tanystropheus longobardicus'' fossils indicate that that species at least had a bulbous

The lifestyle of ''Tanystropheus'' is controversial, with different studies favoring a terrestrial or aquatic lifestyle for the animal. Major studies on ''Tanystropheus'' anatomy and ecology by Rupert Wild (1973/1974, 1980) argued that it was an active terrestrial predator, keeping its head held high with an S-shaped flexion.Wild, R. 1973. Tanystropheus longbardicus (Bassani) (Neue Egerbnisse). in Kuhn-Schnyder, E., Peyer, B. (eds) — Triasfauna der Tessiner Kalkalpen XXIII. Schweiz. Paleont. Abh. Vol. 95 Basel, Germany. Though this interpretation is not wholly consistent with its proposed neck biomechanics, more recent arguments have supported the idea that ''Tanystropheus'' was fully capable of movement on land.

Renesto (2005) argued that the neck of ''Tanystropheus'' was lighter than previously suggested, and that the entire front half of the body was more lightly built than the more robust and muscular rear half. In addition to strengthening the hind limbs, the large hip and tail muscles would have shifted the animal's center of mass rearwards, stabilizing the animal as it maneuvered its elongated neck. The neck of ''Tanystropheus'' has low neural spines, a condition which posits that its epaxial musculature was underdeveloped. This would suggest that intrinsic back muscles (such as the ''m. longus cervicis'') were the driving force behind neck movement instead. The zygapophyses of the neck overlap horizontally, which would have limited lateral movement. The elongated cervical ribs would have formed a brace along the underside of the neck. They may have played a similar role to the ossified tendons of many large dinosaurs, transmitting forces from the weight of the head and neck down to the pectoral girdle, as well as providing passive support by limiting dorsoventral (vertical) flexion.Tschanz, K. 1988. Allometry and Heterochrony in the Growth of the Neck of Triassic Prolacertiform Reptiles. Paleontology. 31:997–1011. Unlike ossified tendons, the cervical ribs of ''Tanystropheus'' are dense and fully ossified throughout the animal's lifetime, so its neck was even more inflexible than that of dinosaurs.

A pair of 2015 blog posts by paleoartist

The lifestyle of ''Tanystropheus'' is controversial, with different studies favoring a terrestrial or aquatic lifestyle for the animal. Major studies on ''Tanystropheus'' anatomy and ecology by Rupert Wild (1973/1974, 1980) argued that it was an active terrestrial predator, keeping its head held high with an S-shaped flexion.Wild, R. 1973. Tanystropheus longbardicus (Bassani) (Neue Egerbnisse). in Kuhn-Schnyder, E., Peyer, B. (eds) — Triasfauna der Tessiner Kalkalpen XXIII. Schweiz. Paleont. Abh. Vol. 95 Basel, Germany. Though this interpretation is not wholly consistent with its proposed neck biomechanics, more recent arguments have supported the idea that ''Tanystropheus'' was fully capable of movement on land.

Renesto (2005) argued that the neck of ''Tanystropheus'' was lighter than previously suggested, and that the entire front half of the body was more lightly built than the more robust and muscular rear half. In addition to strengthening the hind limbs, the large hip and tail muscles would have shifted the animal's center of mass rearwards, stabilizing the animal as it maneuvered its elongated neck. The neck of ''Tanystropheus'' has low neural spines, a condition which posits that its epaxial musculature was underdeveloped. This would suggest that intrinsic back muscles (such as the ''m. longus cervicis'') were the driving force behind neck movement instead. The zygapophyses of the neck overlap horizontally, which would have limited lateral movement. The elongated cervical ribs would have formed a brace along the underside of the neck. They may have played a similar role to the ossified tendons of many large dinosaurs, transmitting forces from the weight of the head and neck down to the pectoral girdle, as well as providing passive support by limiting dorsoventral (vertical) flexion.Tschanz, K. 1988. Allometry and Heterochrony in the Growth of the Neck of Triassic Prolacertiform Reptiles. Paleontology. 31:997–1011. Unlike ossified tendons, the cervical ribs of ''Tanystropheus'' are dense and fully ossified throughout the animal's lifetime, so its neck was even more inflexible than that of dinosaurs.

A pair of 2015 blog posts by paleoartist

Contrary to earlier arguments, Renesto and Saller (2018) found some evidence that ''Tanystropheus'' was adapted for an unusual style of swimming. They noted that, based on reconstructions of muscle mass, the hind limbs would have been quite flexible and powerful according to muscle correlations on the legs, pelvis, and tail vertebrae. Their proposal was that ''Tanystropheus'' made use of a specialized mode of underwater movement: extending the hind limbs forward and then simultaneously retracting them, creating a powerful 'jump' forward. Further support for this hypothesis is based on the

Contrary to earlier arguments, Renesto and Saller (2018) found some evidence that ''Tanystropheus'' was adapted for an unusual style of swimming. They noted that, based on reconstructions of muscle mass, the hind limbs would have been quite flexible and powerful according to muscle correlations on the legs, pelvis, and tail vertebrae. Their proposal was that ''Tanystropheus'' made use of a specialized mode of underwater movement: extending the hind limbs forward and then simultaneously retracting them, creating a powerful 'jump' forward. Further support for this hypothesis is based on the

George Olshevsky expands on the history of "P." ''exogyrarum''

, on the Dinosaur Mailing List * Huene, 1902. "Übersicht über die Reptilien der Trias" eview of the Reptilia of the Triassic ''Geologische und Paläontologische Abhandlungen''. 6, 1-84. * Fritsch, 1905. "Synopsis der Saurier der böhm. Kreideformation" ynopsis of the saurians of the Bohemian Cretaceous formation ''Sitzungsberichte der königlich-böhmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften'', II Classe. 1905(8), 1–7.

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of archosauromorph reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

which lived during the Triassic Period

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is the ...

in Europe, Asia, and North America. It is recognisable by its extremely elongated neck, longer than the torso and tail combined. The neck was composed of 13 vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

e strengthened by extensive cervical rib Cervical ribs are the ribs of the neck in many tetrapods. In most mammals, including humans, cervical ribs are not normally present as separate structures. They can, however, occur as a pathology. In humans, pathological cervical ribs are usually no ...

s. ''Tanystropheus'' is one of the most well-described non- archosauriform archosauromorphs, known from numerous fossils, including nearly complete skeletons. Some species within the genus may have reached a total length of , making ''Tanystropheus'' the longest non-archosauriform archosauromorph as well. ''Tanystropheus'' is the namesake of the family Tanystropheidae

Tanystropheidae is an extinct family (biology), family of archosauromorph reptiles that lived throughout the Triassic Period, often considered to be "protorosaurs". They are characterized by their long, stiff necks formed from elongated cervical ...

, a clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

collecting many long-necked Triassic archosauromorphs previously described as " protorosaurs" or " prolacertiforms".

''Tanystropheus'' contains at least two valid species as well as fossils which cannot be referred to a specific species. The type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of ''Tanystropheus'' is ''T. conspicuus'', a dubious name applied to particularly large fossils from Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

and Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. Complete skeletons are common in the Besano Formation

The Besano Formation is a geological formation in the southern Alps of northwestern Italy and southern Switzerland. This formation, a thin but fossiliferous succession of Dolomite (rock), dolomite and Shale, black shale, is famous for its preserva ...

at Monte San Giorgio

Monte San Giorgio is a Swiss mountain and UNESCO World Heritage Site near the border between Switzerland and Italy. It is part of the Lugano Prealps, overlooking Lake Lugano in the Swiss Canton of Ticino.

Monte San Giorgio is a wooded mountai ...

, on the border of Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. Monte San Giorgio fossils belong to two species: the smaller ''T. longobardicus'' and the larger ''T. hydroides''. These two species were formally differentiated in 2020 primarily on the basis of their strongly divergent skull anatomy. When ''T. longobardicus'' was first described in 1886, it was initially mistaken for a pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

and given the name "''Tribelesodon''". Starting in the 1920s, systematic excavations at Monte San Giorgio unearthed many more ''Tanystropheus'' fossils, revealing that the putative wing bones of ''"Tribelesodon"'' were actually neck vertebrae.

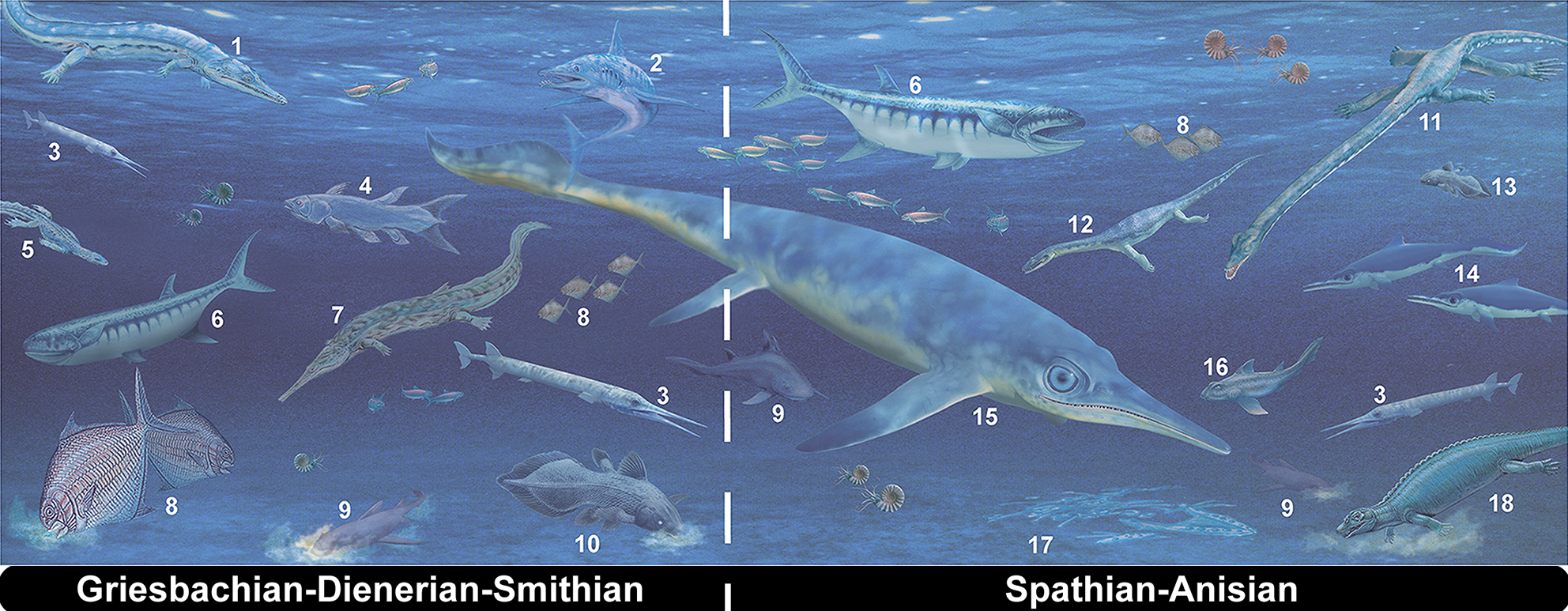

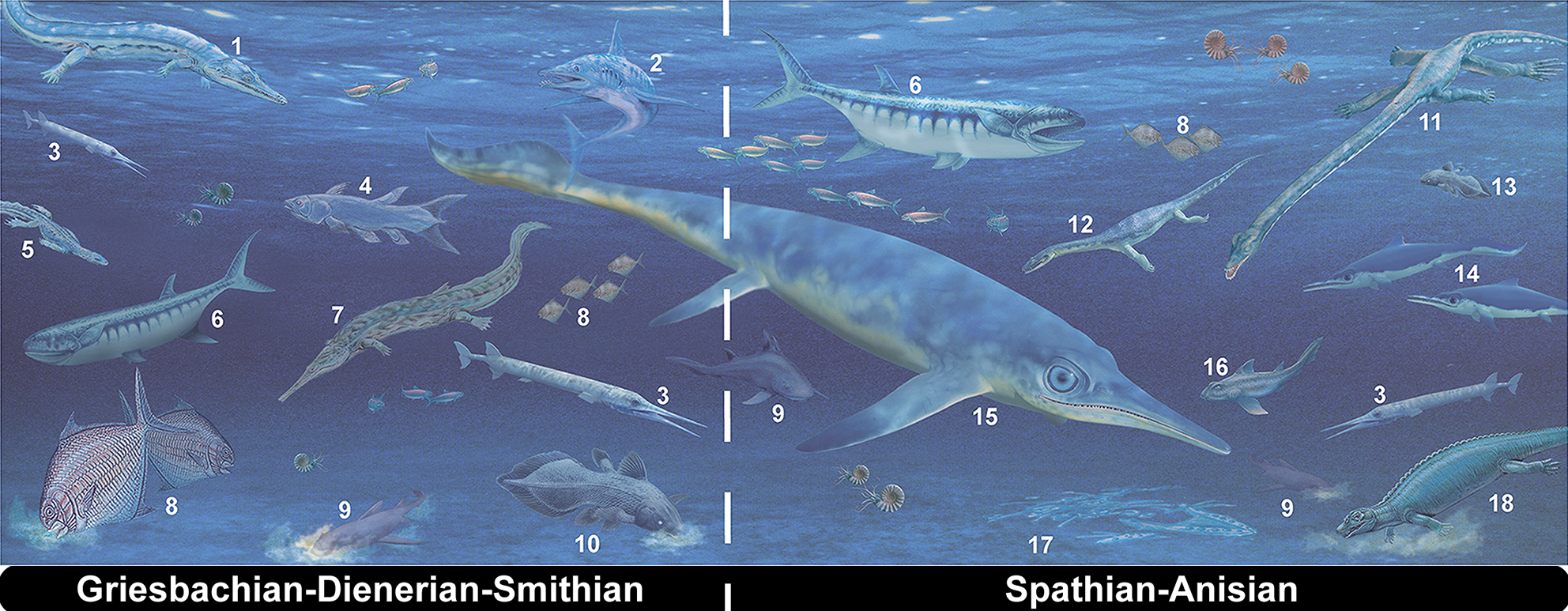

Most ''Tanystropheus'' fossils hail from marine or coastal deposits of the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

epoch (Anisian

In the geologic timescale, the Anisian is the lower stage (stratigraphy), stage or earliest geologic age, age of the Middle Triassic series (stratigraphy), series or geologic epoch, epoch and lasted from million years ago until million years ag ...

and Ladinian

The Ladinian is a stage and age in the Middle Triassic series or epoch. It spans the time between Ma and ~237 Ma (million years ago). The Ladinian was preceded by the Anisian and succeeded by the Carnian (part of the Upper or Late Triassic ...

stages), with some exceptions. For example, a vertebra from Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

was recovered from primarily freshwater sediments. The youngest fossils in the genus are a pair of well-preserved skeletons from the Zhuganpo Formation, a geological unit in China which dates to the earliest part of the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

(early Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227.3 ...

stage). The oldest putative fossils belong to ''"T. antiquus"'', a European species from the latest part of the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 251.9 Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which ...

(late Olenekian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age (geology), age in the Early Triassic epoch (geology), epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the Lower Triassic series (stratigraphy), series. It spans the time betw ...

stage). ''T. antiquus'' had a proportionally shorter neck than other ''Tanystropheus'' species, so some paleontologists consider that ''T. antiquus'' deserves a separate genus, '' Protanystropheus''.

The lifestyle of ''Tanystropheus'' has been the subject of much debate.Dal Sasso, C. and Brillante, G. (2005). ''Dinosaurs of Italy''. Indiana University Press. , . ''Tanystropheus'' is unknown from drier environments and its neck is rather stiff and ungainly, suggesting a reliance on water. Conversely, the limbs and tail lack most adaptations for swimming and closely resemble their equivalents in terrestrial reptiles. Recent studies have supported an intermediate position, reconstructing ''Tanystropheus'' as an animal equally capable on land and in the water. Despite its length, the neck was lightweight and stabilized by tendon

A tendon or sinew is a tough band of fibrous connective tissue, dense fibrous connective tissue that connects skeletal muscle, muscle to bone. It sends the mechanical forces of muscle contraction to the skeletal system, while withstanding tensi ...

s, so it would not been a fatal hindrance to terrestrial locomotion. The hindlimbs and the base of the tail were large and muscular, capable of short bursts of active swimming in shallow water. ''Tanystropheus'' was most likely a piscivorous

A piscivore () is a carnivorous animal that primarily eats fish. Fish were the diet of early tetrapod evolution (via water-bound amphibians during the Devonian period); insectivory came next; then in time, the more terrestrially adapted rept ...

ambush predator

Ambush predators or sit-and-wait predators are carnivorous animals that capture their prey via stealth, luring or by (typically instinctive) strategies utilizing an element of surprise. Unlike pursuit predators, who chase to capture prey u ...

: the narrow subtriangular skull of ''T. longobardicus'' is supplied with three-cusped teeth suited for holding onto slippery prey, while the broader skull of ''T. hydroides'' bears an interlocking set of large curved fangs similar to the fully aquatic plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s.

History and species

Monte San Giorgio species

19th century excavations atMonte San Giorgio

Monte San Giorgio is a Swiss mountain and UNESCO World Heritage Site near the border between Switzerland and Italy. It is part of the Lugano Prealps, overlooking Lake Lugano in the Swiss Canton of Ticino.

Monte San Giorgio is a wooded mountai ...

, a UNESCO world heritage site

World Heritage Sites are landmarks and areas with legal protection under an treaty, international treaty administered by UNESCO for having cultural, historical, or scientific significance. The sites are judged to contain "cultural and natural ...

on the Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

-Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

border, revealed a fragmentary fossil of an animal with three-cusped (tricuspid) teeth and elongated bones. Monte San Giorgio preserves the Besano Formation

The Besano Formation is a geological formation in the southern Alps of northwestern Italy and southern Switzerland. This formation, a thin but fossiliferous succession of Dolomite (rock), dolomite and Shale, black shale, is famous for its preserva ...

(also known as the Grenzbitumenzone), a late Anisian

In the geologic timescale, the Anisian is the lower stage (stratigraphy), stage or earliest geologic age, age of the Middle Triassic series (stratigraphy), series or geologic epoch, epoch and lasted from million years ago until million years ag ...

-early Ladinian

The Ladinian is a stage and age in the Middle Triassic series or epoch. It spans the time between Ma and ~237 Ma (million years ago). The Ladinian was preceded by the Anisian and succeeded by the Carnian (part of the Upper or Late Triassic ...

lagerstätte

A Fossil-Lagerstätte (, from ''Lager'' 'storage, lair' '' Stätte'' 'place'; plural ''Lagerstätten'') is a sedimentary deposit that preserves an exceptionally high amount of palaeontological information. ''Konzentrat-Lagerstätten'' preserv ...

recognised for its spectacular fossils.''Tanystropheus''Vertebrate Palaeontology at Milano University. Retrieved 2007-02-19. In 1886, Francesco Bassani interpreted the unusual tricuspid fossil as a

pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

, which he named ''Tribelesodon longobardicus''. The holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

specimen of ''Tribelesodon longobardicus'' was stored in the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano

The Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano (Milan Natural History Museum) is a museum in Milan, Italy. It was founded in 1838 when the naturalist Giuseppe de Cristoforis donated his collections to the city. Its first director was the taxono ...

(Natural History Museum of Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

), and was destroyed by allied bombing of Milan in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

Excavations by University of Zürich

The University of Zurich (UZH, ) is a public university, public research university in Zurich, Switzerland. It is the largest university in Switzerland, with its 28,000 enrolled students. It was founded in 1833 from the existing colleges of the ...

paleontologist Bernhard Peyer

Bernhard Peyer (25 July 1885 – 23 February 1963) was a Swiss paleontologist and anatomist who served as a professor at the University of Zurich. A major contribution was on the evolution of vertebrate teeth.

Peyer was born in Schaffhausen, Swit ...

in the late 1920s and 1930s revealed many more complete fossils of the species from Monte San Giorgio. Peyer's discoveries allowed ''Tribelesodon longobardicus'' to be recognised as a non-flying reptile, more than 40 years after its original description. Its supposed elongated finger bones were recognized as neck vertebrae, which compared favorably with those previously described as ''Tanystropheus'' from Germany and Poland. Thus, ''Tribelesodon longobardicus'' was renamed to ''Tanystropheus longobardicus'' and its anatomy was revised into a long-necked, non-pterosaur reptile. Specimen PIMUZ T 2791, which was discovered in 1929, has been designated as the neotype

In biology, a type is a particular specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to anchor or centralizes ...

of the species.

Well-preserved ''T. longobardicus'' fossils continue to be recovered from Monte San Giorgio up to the present day. Fossils from the mountain are primarily stored at the rebuilt Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Milano (MSNM), the Paleontological Museum of Zürich (PIMUZ), and the Museo Cantonale di Scienze Naturali di Lugano

Lugano ( , , ; ) is a city and municipality within the Lugano District in the canton of Ticino, Switzerland. It is the largest city in both Ticino and the Italian-speaking region of southern Switzerland. Lugano has a population () of , and an u ...

(MCSN). Rupert Wild reviewed and redescribed all specimens known at the time via several large monographs in 1973/4 and 1980. In 2005, Silvio Renesto described a ''T. longobardicus'' specimen from Switzerland which preserved the impressions of skin and other soft tissue. Five new MSNM specimens of ''T. longobardicus'' were described by Stefania Nosotti in 2007, allowing for a more comprehensive view of the species' anatomy.

A small but well-preserved skull and neck, specimen PIMUZ T 3901, was found in the slightly younger Meride Limestone at Monte San Giorgio. Wild (1980) gave it a new species, ''T. meridensis'', based on a set of skull and vertebral traits proposed to differ from ''T. longobardicus''. Later reinvestigations failed to confirm the validity of these differences, rendering ''T. meridensis'' a junior synonym

In taxonomy, the scientific classification of living organisms, a synonym is an alternative scientific name for the accepted scientific name of a taxon. The botanical and zoological codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

...

of ''T. longobardicus''. A 2019 revision of ''Tanystropheus'' found that ''T. longobardicus'' and ''T. antiquus'' were the only valid species in the genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

.

''Tanystropheus'' specimens from Monte San Giorgio have long been segregated into two morphotypes based on their tooth structure. Smaller specimens bear tricuspid teeth at the back of the jaw while larger specimens have a set of single-pointed fangs. The two morphotypes were originally considered to represent juvenile and adult specimens of ''T. longobardicus'', though many studies have supported the hypothesis that they represent separate species. A 2020 study found numerous differences between the skulls of large and small specimens, formalizing the proposal to divide the two into separate species. Moreover, a histological

Histology,

also known as microscopic anatomy or microanatomy, is the branch of biology that studies the microscopic anatomy of biological tissue (biology), tissues. Histology is the microscopic counterpart to gross anatomy, which looks at large ...

investigation revealed that one small specimen, PIMUZ T 1277, was a skeletally mature adult at a length of only 1.5 meters (4.9 ft). The larger one-cusped morphotype was named as a new species, ''Tanystropheus hydroides'' (referencing the Hydra of Greek mythology

Greek mythology is the body of myths originally told by the Ancient Greece, ancient Greeks, and a genre of ancient Greek folklore, today absorbed alongside Roman mythology into the broader designation of classical mythology. These stories conc ...

), while the smaller tricuspid morphotype retains the name ''T. longobardicus''.

Polish and German species

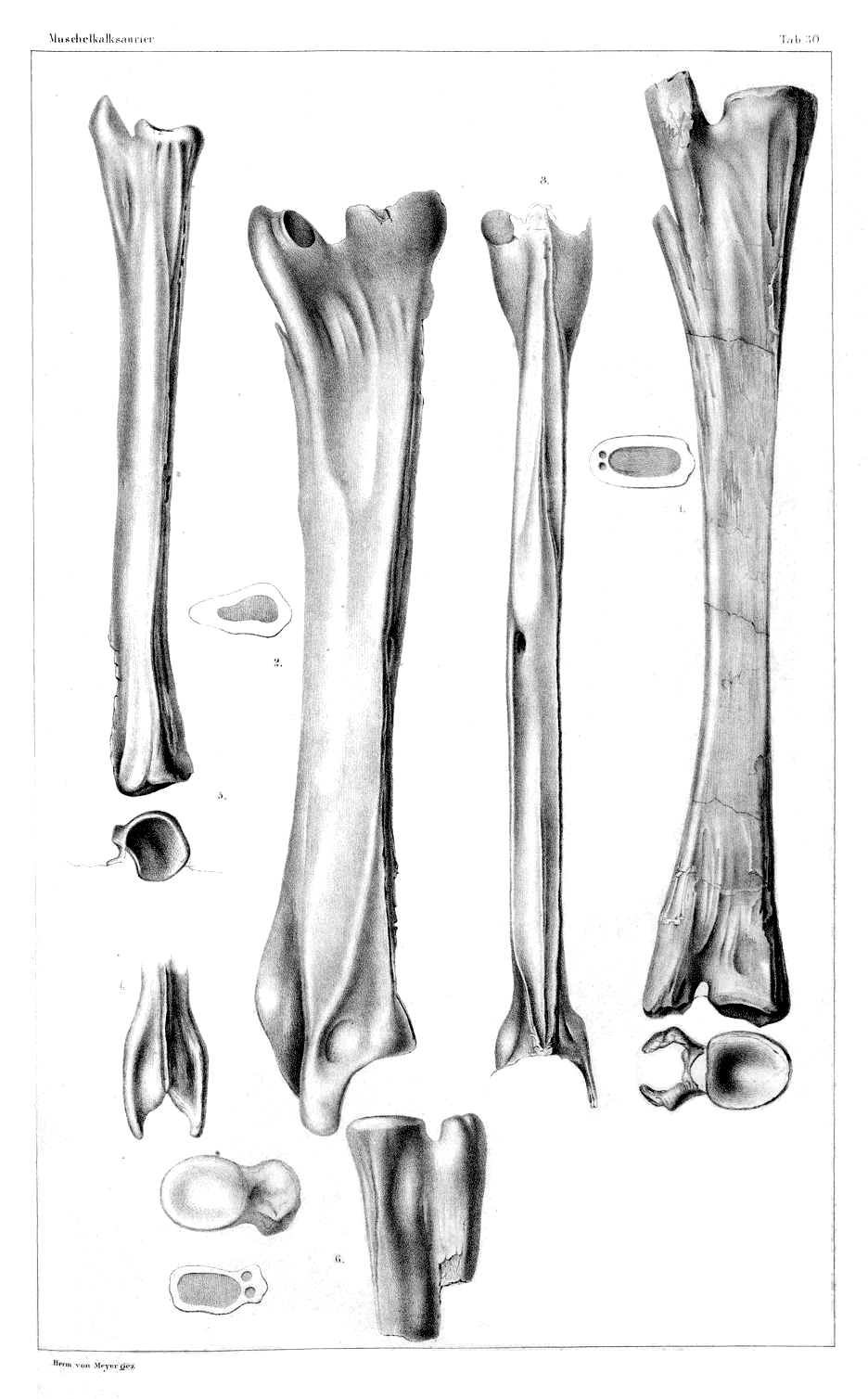

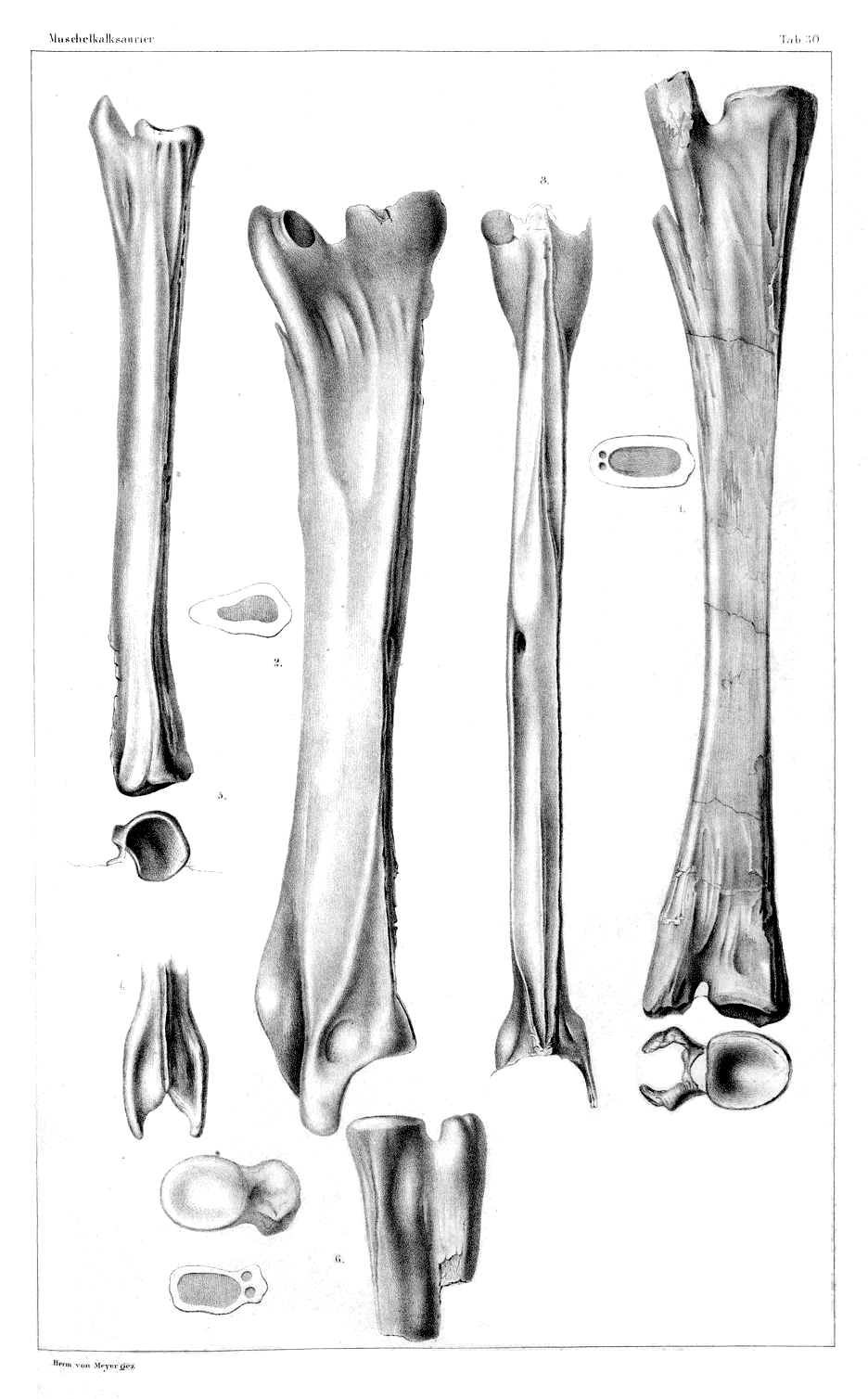

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were found in the mid-19th century. They included eight large vertebrae from the Upper

The first ''Tanystropheus'' specimens to be described were found in the mid-19th century. They included eight large vertebrae from the Upper Muschelkalk

The Muschelkalk (German for "shell-bearing limestone"; ) is a sequence of sedimentary rock, sedimentary rock strata (a lithostratigraphy, lithostratigraphic unit) in the geology of central and western Europe. It has a Middle Triassic (240 to 230 m ...

of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and a partial skeleton from the Lower Keuper of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. These geological units occupy part of the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

, from the latest Anisian

In the geologic timescale, the Anisian is the lower stage (stratigraphy), stage or earliest geologic age, age of the Middle Triassic series (stratigraphy), series or geologic epoch, epoch and lasted from million years ago until million years ag ...

to middle Ladinian

The Ladinian is a stage and age in the Middle Triassic series or epoch. It spans the time between Ma and ~237 Ma (million years ago). The Ladinian was preceded by the Anisian and succeeded by the Carnian (part of the Upper or Late Triassic ...

stages. Though the fossils were initially given the name ''Macroscelosaurus'' by Count Georg Zu Münster, the publication containing this name is lost and its genus is considered a ''nomen oblitum

In zoological nomenclature, a ''nomen oblitum'' (plural: ''nomina oblita''; Latin for "forgotten name") is a disused scientific name which has been declared to be obsolete (figuratively "forgotten") in favor of another "protected" name.

In its pr ...

''. In 1855, Hermann von Meyer supplied the name ''Tanystropheus conspicuus'', the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of ''Tanystropheus'', to the fossils. They were later regarded as ''Tanystropheus'' fossils undiagnostic relative to other species, rendering ''T. conspicuus'' a ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

'' possibly synonymous with ''T. hydroides''.

Over 500 "''Tanystropheus conspicuus''" specimens have been recovered from a Lower Keuper bonebed near the Silesian village of Miedary. This is the largest known concentration of ''Tanystropheus'' fossils, more than double the number collected from Monte San Giorgio. Though the Miedary specimens are individually limited to isolated postcranial bones, they are preserved in three dimensions and show great potential for elucidating the morphology of the genus. The Miedary locality represents an isolated brackish body of water close to the coast, and the abundance of ''Tanystropheus'' fossils suggests that it was an animal well-suited for this kind of habitat.

In the late 1900s, Friedrich von Huene

Baron Friedrich Richard von Hoyningen-Huene (22 March 1875 – 4 April 1969) was a German nobleman paleontologist who described a large number of dinosaurs, more than anyone else in 20th-century Europe. He studied a range of Permo-Carbonife ...

named several dubious ''Tanystropheus'' species from Germany and Poland. ''T. posthumus'', from the Norian of Germany, was later reevaluated as an indeterminate theropod vertebra and a ''nomen dubium''. Several more von Huene species, including "''Procerosaurus cruralis''", "''Thecodontosaurus

''Thecodontosaurus'' ("socket-tooth lizard") is a genus of herbivorous basal sauropodomorph dinosaur that lived during the late Triassic period (Carnian? age).

Its remains are known mostly from Triassic "fissure fillings" in South England. ''T ...

latespinatus''", and "''Thecodontosaurus primus''", have been reconsidered as indeterminate material of ''Tanystropheus'' or other archosauromorphs.

One of Von Huene's species appears to be valid: ''T. antiquus'', from the Gogolin Formation

Gogolin Formation – Triassic geologic formation, hitherto named the Gogolin Beds,Assmann P., 1913 – Beitrag zur Kenntniss der Stratigraphie des oberschlesischen Muschelkalks. Jb. Preuss. Geol. Landesanst., 34: 658 – 671, Berlin.Assmann P., ...

of Poland, was based on cervical vertebrae which were proportionally shorter than those of other ''Tanystropheus'' species. Long considered destroyed in World War II, several ''T. antiquus'' fossils were rediscovered in the late 2010s. The proportions of ''T. antiquus'' fossils are easily distinguishable, and it is currently considered a valid species of archosauromorph, though its referral to the genus ''Tanystropheus'' has been questioned''.'' The Gogolin Formation ranges from the upper Olenekian

In the geologic timescale, the Olenekian is an age (geology), age in the Early Triassic epoch (geology), epoch; in chronostratigraphy, it is a stage (stratigraphy), stage in the Lower Triassic series (stratigraphy), series. It spans the time betw ...

(latest part of the Early Triassic

The Early Triassic is the first of three epochs of the Triassic Period of the geologic timescale. It spans the time between 251.9 Ma and Ma (million years ago). Rocks from this epoch are collectively known as the Lower Triassic Series, which ...

) to the lower Anisian in age. Assuming they belong within ''Tanystropheus'', the fossils of ''T. antiquus'' may be the oldest in the genus. Specimens likely referable to ''T. antiquus'' are also known from throughout Germany and the fossiliferous Winterswijk site in the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

.

Other ''Tanystropheus'' fossils

In the 1880s, E.D. Cope named three supposed new ''Tanystropheus'' species (''T. bauri'', ''T. willistoni'', and ''T. longicollis'') from the Late Triassic Chinle Formation inNew Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

. However, these fossils were later determined to be tail vertebrae belonging to theropod dinosaurs, which were named under the new genus ''Coelophysis

''Coelophysis'' ( Traditional English pronunciation of Latin, traditionally; or , as heard more commonly in recent decades) is a genus of coelophysid Theropoda, theropod dinosaur that lived Approximation, approximately 215 to 201.4 million y ...

''. Authentic ''Tanystropheus'' specimens from the Makhtesh Ramon

Makhtesh Ramon (; ''lit.'' Ramon Crater/ Makhtesh; ; ''lit.'' The Ruman Wadi) is a geological feature of Israel's Negev desert. Located some 85 km south of Beersheba, the landform is the world's largest "erosion cirque" (steephead valley ...

in Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

were described as a new species, ''T. haasi'', in 2001. However, this species may be dubious due to the difficulty of distinguishing its vertebrae from ''T. conspicuus'' or ''T. longobardicus''. Another new species, ''T. biharicus'', was described from Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

in 1975. It has also been considered possibly synonymous with ''T. longobardicus''. A ''Tanystropheus''-like vertebra from the middle Ladinian Erfurt Formation (Lettenkeuper) of Germany was described in 1846 as one of several fossils gathered under the name "'' Zanclodon laevis''". Though likely the first ''Tanystropheus'' fossil to be discovered, the vertebra is now lost, and surviving jaw fragments and other fossil scraps of "''Zanclodon laevis"'' represent indeterminate archosauriforms with no relation to ''Tanystropheus''.Schoch, R.R. (2011). New archosauriform remains from the German Lower Keuper. ''Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen'' 260: 87–100. . ''Tanystropheus'' vertebrae have also been found in the Villány Mountains

Villány Mountains ( ) is a relatively low mountain range located west from the town of Villány, in Baranya county, Southern Hungary.

Its highest summit, the Szársomlyó is 442 metres high. The latter has an extraordinary flora: on its sou ...

of Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

.

The most well-preserved ''Tanystropheus'' fossils outside of Monte San Giorgio come from the Guizhou

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption =

, image_map = Guizhou in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_alt = Map showing the location of Guizhou Province

, map_caption = Map s ...

province of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

, as described by Li (2007) and Rieppel (2010). They are also among the youngest and easternmost fossils in the genus, hailing from the upper Ladinian or lower Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage (stratigraphy), stage of the Upper Triassic series (stratigraphy), Series (or earliest age (geology), age of the Late Triassic Epoch (reference date), Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227.3 ...

Zhuganpo Formation. Although the postcrania is complete and indistinguishable from the fossils of Monte San Giorgio, no skull material is preserved, and their younger age precludes unambiguous placement into any ''Tanystropheus'' species. The Chinese material includes a large morphotype (''T. hydroides?'') specimen, GMPKU-P-1527, and an indeterminate juvenile skeleton, IVPP V 14472.

Indeterminate ''Tanystropheus'' remains are also known from the Jilh Formation of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

and various Anisian-Ladinian sites in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

, Italy, and Switzerland. The youngest ''Tanystropheus'' fossil in Europe is a vertebra from the lower Carnian Fusea site in Friuli, Italy. In 2015, a large ''Tanystropheus'' cervical vertebra was described from the Economy Member of the Wolfville Formation

The Wolfville Formation is a Triassic geologic formation of Nova Scotia. The formation is of Carnian to early Norian age. Fossils of small land vertebrates have been found in the formation, including procolophonid and early archosauromorph rep ...

, in the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy () is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world.

The bay was ...

of Nova Scotia, Canada

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. The Wolfville Formation spans the Anisian to Carnian stages, and the Economy Member is likely Middle Triassic (Anisian-Ladinian) in age. It is a rare example of predominantly freshwater strata preserving ''Tanystropheus'' fossils. ''Tanystropheus''-like tanystropheid fossils are known from another freshwater formation in North America: the Anisian-age Moenkopi Formation

The Moenkopi Formation is a geological formation that is spread across the U.S. states of New Mexico, northern Arizona, Nevada, southeastern California, eastern Utah and western Colorado. This unit is considered to be a Geological unit, group ...

of Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

and New Mexico.

Several new tanystropheid genera have been named from former ''Tanystropheus'' fossils. Fossils from the Anisian Röt Formation in Germany, previously referred to ''Tanystropheus antiquus,'' were named as a new genus and species in 2006: '' Amotosaurus rotfeldensis''. In 2011, fossils from the Lipovskaya Formation of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

were given the new genus and species '' Augustaburiania vatagini'' by A.G. Sennikov. He also named the new genus '' Protanystropheus'' for ''T. antiquus,'' though a few studies continued to retain that species within ''Tanystropheus''. ''Tanystropheus fossai,'' from the Norian

The Norian is a division of the Triassic geological period, Period. It has the rank of an age (geology), age (geochronology) or stage (stratigraphy), stage (chronostratigraphy). It lasted from ~227.3 to Mya (unit), million years ago. It was prec ...

-age Argillite di Riva di Solto in Italy, was given its own genus '' Sclerostropheus'' in 2019.

Anatomy

Skull of ''Tanystropheus longobardicus''

The skull of ''Tanystropheus longobardicus'' is roughly triangular when seen from the side and top, narrowing towards the snout. Eachpremaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

(the toothed bone at the tip of the snout) has a long tooth row, with six teeth. The premaxillary teeth are conical, fluted by longitudinal ridges, and have subthecodont implantation, meaning that the inner wall of each tooth socket is lower than the outer wall. The premaxilla meets the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

(the succeeding toothed bone) along a long, slanted contact. This shape is produced by an elongated postnarial process (rear prong) of the premaxilla, which extends below and behind the nares (nostril holes). The nasals (bones at the top edge of the snout) are poorly known, but were likely narrow and flat. A 2020 reinvestigation revealed that the front part of the nasals and the inner spur of the premaxillae are too short to keep the nares divided. This leaves a single central narial opening for the nostrils, opening upwards. An undivided naris is seen in few other archosauromorphs, namely rhynchosaur

Rhynchosaurs are a group of extinct herbivorous Triassic archosauromorph reptiles, belonging to the order Rhynchosauria. Members of the group are distinguished by their triangular skulls and elongated, beak like premaxillary bones. Rhynchosaurs ...

s, most allokotosaurs, modern crocodilia

Crocodilia () is an order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorph pseudosuchia ...

ns, and '' Teyujagua''.

The maxilla is triangular, reaching its maximum height at mid-length and tapering to the front and rear. There are up to 14 or 15 teeth in the maxilla, though some individuals have fewer. ''T. longobardicus'' is a reptile with heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

Human dentition is heterodont and diphyodont as an example.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals wher ...

dentition, meaning that it had more than one type of tooth shape. In contrast to the simple fang-like premaxillary teeth, most or all of the maxillary teeth have a distinctive tricuspid shape, with the crown

A crown is a traditional form of head adornment, or hat, worn by monarchs as a symbol of their power and dignity. A crown is often, by extension, a symbol of the monarch's government or items endorsed by it. The word itself is used, parti ...

split into three stout triangular cusps (points). The cusps are arranged in a line from front-to-back, with the central cusp larger than the other two cusps. Among Triassic reptiles, early pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

s such as ''Eudimorphodon

''Eudimorphodon'' is an extinct genus of pterosaur that was discovered in 1973 by Mario Pandolfi in the town of Cene, Lombardy, Cene, Italy and described the same year by Rocco Zambelli. The nearly complete skeleton was retrieved from shale depos ...

'' developed an equivalent tooth shape, and tricuspid teeth can also be found in a few modern lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

species. Some individuals of ''T. longobardicus'' have tricuspid teeth along their entire maxilla, while in others up to seven maxillary teeth are single-cusped fangs similar to the premaxillary teeth.

The front edge of each orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

(eye socket) is marked by two bones: the prefrontal and lacrimal. The prefrontal is tall and projects a low vertical ridge in front of the orbit. The small, sliver-shaped lacrimal is nestled further down along the maxilla. The lower edge of the orbit is formed by the jugal, a bone with a slender anterior process (front branch) and a somewhat broader dorsal process (upper branch). There is also a very short pointed posterior process (rear branch) which ends freely and fails to contact any other bone. The shape of the jugal in ''Tanystropheus'' is typical for early archosauromorphs; the underdeveloped posterior process indicates that the margin of the infratemporal fenestra (lower skull hole behind the eye) was incomplete and open from below. The postorbital bone

The ''postorbital'' is one of the bones in vertebrate skulls which forms a portion of the dermal skull roof and, sometimes, a ring about the orbit. Generally, it is located behind the postfrontal and posteriorly to the orbital fenestra. In some ...

, which links the jugal to the top of the skull, was tall and roughly boomerang-shaped, though poor preservation obscures some details. The squamosal bone

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral ...

, which extends behind the postorbital, is also poorly known in ''T. longobardicus'', and many supposed squamosal fossils in the species have been reinterpreted as displaced postorbitals. The quadrate bone

The quadrate bone is a skull bone in most tetrapods, including amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, birds), and early synapsids.

In most tetrapods, the quadrate bone connects to the quadratojugal and squamosal bones in the skull, and forms up ...

, which forms the rear edge of the skull and upper half of the jaw joint, is wide and tall. It has a strong lateral crest and a low pterygoid ramus (a vertical internal plate, articulating with the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal specie ...

in the roof of the mouth). No fossils of ''T. longobardicus'' preserve a quadratojugal The quadratojugal is a skull bone present in many vertebrates, including some living reptiles and amphibians.

Anatomy and function

In animals with a quadratojugal bone, it is typically found connected to the jugal (cheek) bone from the front and ...

, a bone which normally lies along the quadrate at the rear lower corner of the skull. Nevertheless, a quadratojugal was likely present in the species, since it occurs in ''T. hydroides'' and nearly every other early archosauromorph.

The paired frontals (skull roof bones above the orbits) have been described as "axe-shaped flanges", projecting broad curved plates above each orbit. Together, the frontals are narrowest at the front, terminating at a three-lobed contact with the nasals. The sutures between the frontals and their neighboring bones are coarse and interdigitating (interlocking). A small triangular bone, the postfrontal The postfrontal is a paired cranial bone found in many tetrapods. It occupies an area of the skull roof between and behind the orbits (eye sockets), lateral to the frontal and parietal bones, and anterior to the postorbital bone.

The postfrontal ...

, wedges behind the rear outer corner of each frontal. A pair of larger plate-like bones, the parietals, sit directly behind the frontals on the skull roof. In ''T. longobardicus'', the parietals are fairly broad and flat, with a shallowly concave outer edge. Like the frontals, the paired parietals are seemingly separate bones, unfused to each other in every member of the species. A large hole, the pineal foramen

A parietal eye (third eye, pineal eye) is a part of the epithalamus in some vertebrates. The eye is at the top of the head; is photoreceptive; and is associated with the pineal gland, which regulates circadian rhythmicity and hormone production ...

(sometimes called the parietal foramen), is present at the midline of the skull between the front part of each parietal. When seen from below, a pair of curved crests along the frontals and parietals mark the edge of the forebrain

In the anatomy of the brain of vertebrates, the forebrain or prosencephalon is the rostral (forward-most) portion of the brain. The forebrain controls body temperature, reproductive functions, eating, sleeping, and the display of emotions.

Ve ...

, as defined by a bulbous central hollow.

The eye was supported by more than 10 rectangular ossicles (tiny plate-like bones) connecting into a scleral ring, though a full reconstruction of the ring, with 18 ossicles, is conjectural. Few details of the braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calv ...

and palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

(bony roof of the mouth) are known for ''T. longobardicus''. The scant available evidence suggests that these regions of the skull are rather unspecialized in this species. The vomer

The vomer (; ) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxillary bones. The vomer forms ...

s (front components of the palate) are narrow and dotted with at least nine tiny teeth. The succeeding palatine

A palatine or palatinus (Latin; : ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman Empire, Roman times.

and pterygoid Pterygoid, from the Greek for 'winglike', may refer to:

* Pterygoid bone, a bone of the palate of many vertebrates

* Pterygoid processes of the sphenoid bone

** Lateral pterygoid plate

** Medial pterygoid plate

* Lateral pterygoid muscle

* Medial ...

bones are also supplied with rows of teeth: up to six relatively large teeth in the former and at least 12 small teeth in the latter. Teeth on the vomers, palatines, and pterygoids are the norm for early archosauromorphs and reptiles as a whole.

The lower jaw

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

is slender, and most of its length is devoted to the toothed dentary

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone ...

bone. The dentary is downturned at its tip and its outer surface is dotted with a row of prominent foramina (blood vessel pits). There are up to 19 teeth in the dentary. Most commonly, the first six teeth are prominent conical fangs, akin to the premaxilla, while the remainder are small and tricuspid, akin to the maxilla. There is some variation in the number of each tooth shape, and some individuals may have up to 11 conical teeth. The inner surface of the dentary is joined by a splint-shaped bone, the splenial

The splenial is a small bone in the lower jaw of reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology ...

, at its lower edge. The splenial was most likely not visible in lateral view. At its rear, the dentary seems to be partially overlapped by the surangular

The surangular or suprangular is a jaw bone found in most land vertebrates, except mammals. Usually in the back of the jaw, on the upper edge, it is connected to all other jaw bones: dentary, angular bone, angular, splenial and articular. It is o ...

, a bone which comprises much of the rear part of the jaw. Although it is plausible that a small coronoid bone could be present in front of the surangular, evidence is ambiguous at best for all ''Tanystropheus'' species. A sheathe-like bone, the angular, is well-exposed under the dentary and surangular, though sutures between these bones are difficult to interpret with certainty. The joint at the back of the jaw lies on the articular

The articular bone is part of the lower jaw of most vertebrates, including most jawed fish, amphibians, birds and various kinds of reptiles, as well as ancestral mammals.

Anatomy

In most vertebrates, the articular bone is connected to two o ...

, a lumpy rectangular bone which is floored and reinforced by a similar bone: the prearticular. In ''Tanystropheus'' species with known skull material, both the articular and prearticular contribute equally to a segment of the jaw extending back beyond the level of the jaw joint. This projection, known as a retroarticular process, is enlarged to a similar degree to that of early rhynchosaurs.

Skull of ''Tanystropheus hydroides''

The skull of ''Tanystropheus hydroides'' is broader and flatter than that of ''T. longobardicus''. The first five of six teeth in the premaxilla are very large and fang-like, forming an interlocking "fish trap" similar to '' Dinocephalosaurus'' and manysauropterygia

Sauropterygia ("lizard flippers") is an extinct taxon of diverse, aquatic diapsid reptiles that developed from terrestrial ancestors soon after the end-Permian extinction and flourished during the Triassic before all except for the Plesiosau ...

ns such as plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

s and nothosaur

Nothosaurs (superfamily Nothosauroidea) were Triassic marine sauropterygian reptiles. They averaged about in length, with a long body and tail. The feet were paddle-like, and are known to have been webbed in life, to help power the animal when sw ...

s. All teeth in the skull have a single cusp which is sharp, curved, and unserrated. They have an oval-shaped cross section and shallow subthecodont implantation. Like ''T. longobardicus'', ''T. hydroides'' has a single central narial opening. Unlike ''T. longobardicus'', ''T. hydroides'' has a nearly vertical rear edge of the premaxilla, without a postnarial process. The maxilla is low, with a large and rectangular front portion. There is a perforation near the front of the bone, which would have been penetrated by the tenth dentary tooth when the mouth was closed. Towards the rear, the maxilla develops a concave edge overlooking a long and slender posterior process (rear branch) that projects under the rounded orbit. There are 15 teeth in the maxilla, increasing in size up to the eighth tooth, which is about as large as the premaxillary fangs. ''T.hydroides'' is not known to possess a septomaxilla, a neomorphic bone at the rear tip of the naris in some reptiles. The nasals are broad and plate-like, with a depressed central portion. The lacrimal and prefrontal, though incompletely known, were likely similar to those of ''T. longobardicus''. ''T. hydroides'' has a particularly large nasolacrimal duct

The nasolacrimal duct (also called the tear duct) carries tears from the lacrimal sac of the eye into the nasal cavity. The duct begins in the eye socket between the maxillary and lacrimal bones, from where it passes downwards and backwards. ...

, a tubular channel opening out of the rear of the lacrimal. The frontals are quite wide and form much of the upper edge of the orbit, a condition akin to ''T. longobardicus''. However, the paired frontals meet along a straight suture with a low ridge on the lower (internal) surface, in contrast to ''T. longobardicus'', where the frontals meet at an interdigitating suture with a broad furrow on the underside.sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

along the midline of the skull. This trend is shared with other large archosauromorphs, like ''Dinocephalosaurus'' and '' Azendohsaurus''. The supratemporal fenestrae

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the Temple (anatomy), temporal region of the skull of some Amniote, amniotes, behind the Orbit (anatomy), orbit (eye socket). These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of re ...

(upper skull holes behind the eye) are wide and semi-triangular, exposed almost entirely from above. The postorbital has large and blocky ventral and medial processes (lower and inward branches), which meet at a sharper angle than in any other early archosauromorph. The jugal, conversely, is basically indistinguishable from that of ''T. longobardicus''. The squamosal is deep and rectangular when viewed from the side, with little differentiation between the tall suture with the postorbital and the small suture with the quadratojugal. As a result, most of the posterior skull is clustered together, and the infratemporal fenestra is reduced to a small diagonal hole. The quadratojugal is a curved sliver of bone which twists back alongside the quadrate. Relative to ''T. longobardicus'', the quadrate has a larger pterygoid ramus and a strongly hooked projection at its upper extent.

The palate of ''T. hydroides'' has several unique traits. The vomers are wide and tongue-shaped, each hosting a single row of 15 relatively large curved teeth along the outer edge of the bone, adjacent to the elongated choana

The choanae (: choana), posterior nasal apertures or internal nostrils are two openings found at the back of the nasal passage between the nasal cavity and the pharynx, in humans and other mammals (as well as crocodilians and most skinks). They ...

e (internal openings of the nasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nas ...

). Most other archosauromorphs, ''T. longobardicus'' included, have restricted vomers with rows of minuscule teeth. The rest of the palate is completely toothless in ''T. hydroides'', even the palatines and pterygoids, which bear tooth rows in most early archosauromorphs. The pterygoids are also unusual for their broad palatal ramus (front plate) and a loose, strongly overlapping connection to the ectopterygoids (linking bones between the pterygoid and maxilla). The epipterygoids (vertical bones in front of the braincase) are tall and flattened from the side.

''T. hydroides'' is a rare example of an early archosauromorph with a three-dimensionally preserved braincase. The basioccipital (rear lower component of the braincase) was small, with inset basitubera (vertical plates connecting to neck muscles) linked by a transverse ridge, similar to allokotosaurs and archosauriforms. The parabasisphenoid (front lower component) is less specialized; it lies flat and tapers forwards to a blade-like cultriform process. The rear part of the bone has a deep triangular excavation (known as a median pharyngeal recess) on its underside, flanked by low crests and a pair of small basipterygoid processes (knobs connecting to the pterygoid). The remainder of the braincase is fully fused together into a strongly ossified composite bone, and its constituents must be estimated by comparison to other reptiles. The exoccipitals, which mostly encompass the

''T. hydroides'' is a rare example of an early archosauromorph with a three-dimensionally preserved braincase. The basioccipital (rear lower component of the braincase) was small, with inset basitubera (vertical plates connecting to neck muscles) linked by a transverse ridge, similar to allokotosaurs and archosauriforms. The parabasisphenoid (front lower component) is less specialized; it lies flat and tapers forwards to a blade-like cultriform process. The rear part of the bone has a deep triangular excavation (known as a median pharyngeal recess) on its underside, flanked by low crests and a pair of small basipterygoid processes (knobs connecting to the pterygoid). The remainder of the braincase is fully fused together into a strongly ossified composite bone, and its constituents must be estimated by comparison to other reptiles. The exoccipitals, which mostly encompass the foramen magnum

The foramen magnum () is a large, oval-shaped opening in the occipital bone of the skull. It is one of the several oval or circular openings (foramina) in the base of the skull. The spinal cord, an extension of the medulla oblongata, passes thro ...

(spinal cord hole), are perforated with nerve foramina. Each exoccipital merges outwards into the opisthotic, which sends out a straight, elongated paroccipital process (thick outer branch) to the edge of the cranium. In ''T. longobardicus'', the paroccipital processes are shorter and narrower at their base. The stapes

The ''stapes'' or stirrup is a bone in the middle ear of humans and other tetrapods which is involved in the conduction of sound vibrations to the inner ear. This bone is connected to the oval window by its annular ligament, which allows the f ...

, a bone which transmits vibrations from the ear to the braincase, is slender and splits into two small prongs where it contacts the opisthotic. The opisthotic merges forwards into the prootic, which extensively contacts the parabasisphenoid and hosts a range of larger nerve foramina. The prootic forms much of the front edge of the paroccipital process, akin to the condition in archosauriforms. Another archosauriform-like feature is the presence of a laterosphenoid, an additional braincase component in front of the prootic and above the exit hole for the trigeminal nerve

In neuroanatomy, the trigeminal nerve (literal translation, lit. ''triplet'' nerve), also known as the fifth cranial nerve, cranial nerve V, or simply CN V, is a cranial nerve responsible for Sense, sensation in the face and motor functions ...

(also known as cranial nerve V). The laterosphenoid is small, similar to that of ''Azendohsaurus''. The upper rear part of the braincase is formed by the supraoccipitals, which were presumably fused together as a continuous surface sloping smoothly down to the foramen magnum.

In the lower jaw, the dentaries meet each other at a robust

In the lower jaw, the dentaries meet each other at a robust symphysis

A symphysis (, : symphyses) is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is a type of cartilaginous joint, specifically a secondary cartilaginous joint.

# A symphysis is an amphiarthrosis, a slightly movable joint.

# A growing together o ...

with an interdigitating suture. The front end of the dentary hosts a prominent keel on its lower edge, a unique trait of the species. There are at least 18 dentary teeth; the first three are by far the largest teeth in the skull, forming the lower half of the interlocking "fish trap" with the premaxilla. Most other teeth in the dentary are small, with the exception of the tenth tooth, which juts up to pierce the maxilla. The remainder of the jaw contains the same set of bones as in ''T. longobardicus'', but some details differ in ''T. hydroides''. For example, the splenial is plate-like and covers a larger portion of the internal dentary than in ''T. longobardicus''. In addition, the rear of the dentary overlaps a large portion of the surangular, rather than the surangular acting as the overlapping bone where they meet. The surangular internally bears a large fossa for the jaw's ''adductor'' (vertical biting) muscles, and a prominent surangular foramen is positioned in front of the jaw joint.

Neck

The most recognisable feature of ''Tanystropheus'' is its hyperelongate neck, equivalent to the combined length of the body and tail. ''Tanystropheus'' has 13 cervical (neck) vertebrae, most of which are massive, though the two closest to the head are smaller and less strongly developed. The

The most recognisable feature of ''Tanystropheus'' is its hyperelongate neck, equivalent to the combined length of the body and tail. ''Tanystropheus'' has 13 cervical (neck) vertebrae, most of which are massive, though the two closest to the head are smaller and less strongly developed. The atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

(first cervical), which connects to the skull, is a small, four-part bone complex. It consists of an atlantal intercentrum (small lower component) and pleurocentrum (large lower component), and a pair of atlantal neural arches (prong-like upper components). There does not appear to be a proatlas, which slots between the atlas and skull in some other reptiles. The intercentrum and pleurocentrum are not fused to each other, unlike the single-part atlas of allokotosaurs. The tiny crescent-shaped intercentrum is overlain by a semicircular pleurocentrum, which acts as a base to the backswept neural arches. The axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics