Sun Yat-senUsually known as Sun Zhongshan () in Chinese; also known by

several other names. (; 12 November 186612 March 1925) was a Chinese physician, revolutionary, statesman, and

political philosopher

Political philosophy studies the theoretical and conceptual foundations of politics. It examines the nature, scope, and legitimacy of political institutions, such as states. This field investigates different forms of government, ranging from de ...

who founded the

Republic of China

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

(ROC) and its first political party, the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

(KMT). As the paramount leader of the

1911 Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). The revolution was the culmination of a decade ...

, Sun is credited with overthrowing the

Qing imperial dynasty and served as the first president of the

Provisional Government of the Republic of China (1912) and as the inaugural

leader of the Kuomintang.

Born to a peasant family in

Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

, Sun was educated overseas in

Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

and returned to China to graduate from medical school in

Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

. He led underground

anti-Qing revolutionaries in

South China

South China ( zh, s=, p=Huá'nán, j=jyut6 naam4) is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is ...

, the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, and

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

as one of the

Four Bandits and rose to prominence as the founder of multiple

resistance movements

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through e ...

, including the

Revive China Society

The Revive China Society (), also known as the Society for Regenerating China or the Proper China Society was founded by Sun Yat-sen on 24 November 1894 to forward the goal of establishing prosperity for China and as a platform for future 19 ...

and the

Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China was a secret society and underground resistance movement founded by Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren, and others in Tokyo, Empire of Japan, on 20 August 1905, with the goal of overthrowing China's Qing dynasty. It was formed ...

. He is considered one of the most important figures of modern China, and his political life campaigning against

Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized Ethnic minorities in China, ethnic minority in China and the people from wh ...

rule in favor of a Chinese republic featured constant struggles and frequent periods of exile.

After the success of the 1911 Revolution, Sun proclaimed the

establishment of the Republic of China but had to relinquish the presidency to general

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 18596 June 1916) was a Chinese general and statesman who served as the second provisional president and the first official president of the Republic of China, head of the Beiyang government from 1912 to 1916 and ...

who controlled the powerful

Beiyang Army

The Beiyang Army (), named after the Beiyang region, was a Western-style Imperial Chinese Army established by the Qing dynasty in the early 20th century. It was the centerpiece of a general reconstruction of the Qing military system in the wake ...

, ultimately going into exile in Japan. He later returned to launch a revolutionary government in

southern China

Northern China () and Southern China () are two approximate regions that display certain differences in terms of their geography, demographics, economy, and culture.

Extent

The Qinling–Daba Mountains serve as the transition zone between ...

to challenge the

warlords

Warlords are individuals who exercise military, economic, and political control over a region, often one without a strong central or national government, typically through informal control over local armed forces. Warlords have existed throug ...

who controlled much of the country following Yuan's death in 1916. In 1923, Sun invited representatives of the

Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

to

Guangzhou

Guangzhou, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Canton or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, southern China. Located on the Pearl River about nor ...

to reorganize the KMT and formed the

First United Front

The First United Front , also known as the KMT–CCP Alliance, of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was formed in 1924 as an alliance to end Warlord Era, warlordism in China. Together they formed the National Revolution ...

with the

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP). He did not live to see his party unify the country under his successor,

Chiang Kai-shek, in the

Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT) against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The purpose of the campaign was to reunify China prop ...

. While residing in

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, Sun died of gallbladder cancer in 1925.

Uniquely among 20th-century Chinese leaders, Sun is revered in both Taiwan (where he is officially the "

Father of the Nation

The Father of the Nation is an honorific title given to a person considered the driving force behind the establishment of a country, state, or nation. Pater Patriae was a Roman honorific meaning the "Father of the Fatherland", bestowed by th ...

") and in the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(where he is officially the "Forerunner of the Revolution") for his instrumental role in ending Qing rule and overseeing the conclusion of the Chinese

dynastic system. His political philosophy, known as the

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (), also known as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, San Min Chu-i, or Tridemism is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China during the Republi ...

, sought to modernise China by advocating for

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

,

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

, and the

livelihood of the people in

an ethnically harmonious union (''

Zhonghua minzu

''Zhonghua minzu'' () is a political term in modern Chinese nationalism related to the concepts of nation-building, ethnicity, and race in the Chinese nationality. Collectively, the term refers to the 56 ethnic groups of China, but being ...

''). The philosophy is commemorated as the

National Anthem of the Republic of China

The "National Anthem of the Republic of China", also known by its incipit "Three Principles of the People", is the national anthem of the Republic of China, commonly called Taiwan, as well as the party anthem of the Kuomintang. It was adop ...

, which Sun composed.

Names

Sun's genealogical name was Sun Deming (

Cantonese

Cantonese is the traditional prestige variety of Yue Chinese, a Sinitic language belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family. It originated in the city of Guangzhou (formerly known as Canton) and its surrounding Pearl River Delta. While th ...

: ; ).

[ Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition .] As a child, his

milk name was Tai Tseung (; ).

In school, a teacher gave him the name Sun Wen (; ), which was used by Sun for most of his life. Sun's

courtesy name

A courtesy name ( zh, s=字, p=zì, l=character), also known as a style name, is an additional name bestowed upon individuals at adulthood, complementing their given name. This tradition is prevalent in the East Asian cultural sphere, particula ...

was Zaizhi (; ), and his baptized name was Rixin (; ).

While at school in

British Hong Kong

Hong Kong was under British Empire, British rule from 1841 to 1997, except for a Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, brief period of Japanese occupation during World War II from 1941 to 1945. It was a crown colony of the United Kingdom from 1841 ...

, he got the

art name

An art name (pseudonym or pen name), also known by its native names ''hào'' (in Mandarin Chinese), ''gō'' (in Japanese), ' (in Korean), and ''tên hiệu'' (in Vietnamese), is a professional name used by artists, poets and writers in the Sinosp ...

Yat-sen ().

Sun Zhongshan (; , also romanized ''Chung Shan''), the most popular of his Chinese names in China, is derived from his

Japanese name

in modern times consist of a family name (surname) followed by a given name. Japanese names are usually written in kanji, where the pronunciation follows a special set of rules. Because parents when naming children, and foreigners when adoptin ...

''Kikori Nakayama'' (; ), the pseudonym given to him by

Tōten Miyazaki when he was in hiding in Japan.

His birthplace city was renamed

Zhongshan

Zhongshan ( zh, c=中山 ), alternately romanized via Cantonese as Chungshan, is a prefecture-level city in the south of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, China. As of the 2020 census, the whole city with 4,418,060 inhabitants is n ...

in his honour likely shortly after his death in 1925. Zhongshan is one of the few

cities named after people in China and has remained the official name of the city during Communist rule.

Early years

Birthplace and early life

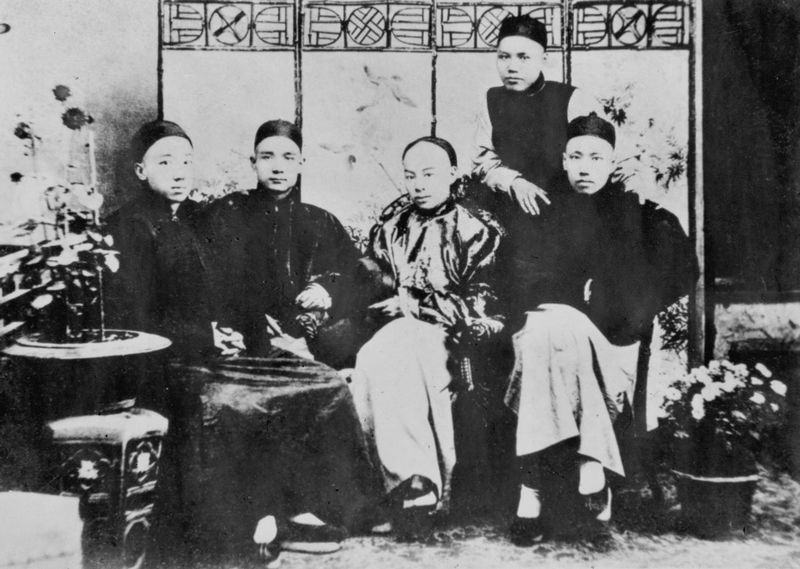

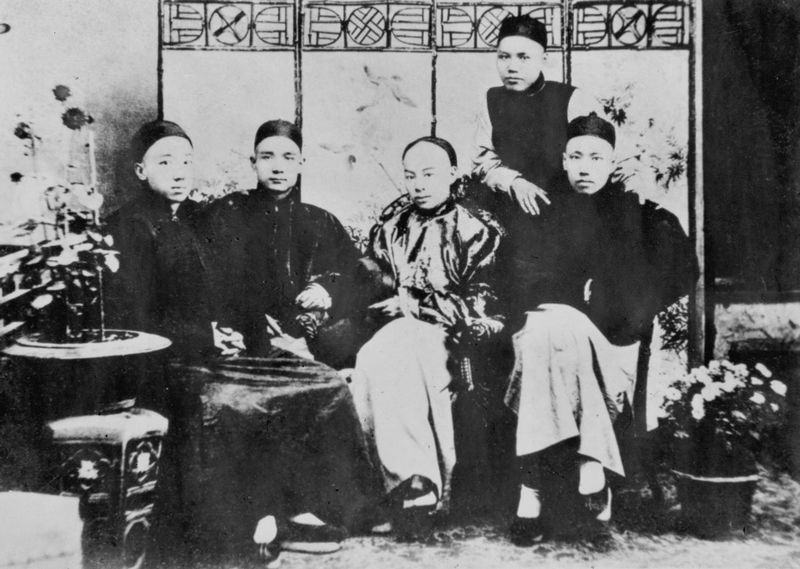

Sun Deming was born on 12 November 1866 to Sun Dacheng and

Madame Yang.

His birthplace was the village of

Cuiheng,

Xiangshan County (now

Zhongshan

Zhongshan ( zh, c=中山 ), alternately romanized via Cantonese as Chungshan, is a prefecture-level city in the south of the Pearl River Delta in Guangdong province, China. As of the 2020 census, the whole city with 4,418,060 inhabitants is n ...

City), Canton Province (now

Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

).

He was of

Hakka

The Hakka (), sometimes also referred to as Hakka-speaking Chinese, or Hakka Chinese, or Hakkas, are a southern Han Chinese subgroup whose principal settlements and ancestral homes are dispersed widely across the provinces of southern China ...

and

Cantonese

Cantonese is the traditional prestige variety of Yue Chinese, a Sinitic language belonging to the Sino-Tibetan language family. It originated in the city of Guangzhou (formerly known as Canton) and its surrounding Pearl River Delta. While th ...

[ ] descent. His father owned very little land and worked as a tailor in

Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

and as a journeyman and a porter. After finishing primary education and meeting childhood friend

Lu Haodong

Lu Zhonggui (30 September 1868 – 7 November 1895), courtesy name Xianxiang, better known by his art name Lu Haodong, was a Chinese revolutionary who lived in the late Qing dynasty. He is best known for designing the Blue Sky with a White Sun ...

,

he moved to

Honolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

in the

Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ɛ ɐwˈpuni həˈvɐjʔi, was an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country from 1795 to 1893, which eventually encompassed all of the inhabited Hawaii ...

, where he lived a comfortable life of modest wealth supported by his elder brother

Sun Mei.

Education

During his stay in Honolulu, Sun began his education at the age of 10,

attending secondary school in Hawaii. In 1878, after receiving a few years of local schooling, a 13-year-old Sun went to live with his elder brother

Sun Mei,

who would later make major contributions to overthrowing the

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

, and who financed Sun's attendance of the

ʻIolani School

Iolani School is a private coeducational K-12 college preparatory school in Honolulu, Hawaiʻi. It serves over 2,200 students with a boarding program for grades 9 - 12 as well as a summer boarding program for middle school grades. Founded in 18 ...

.

There, he studied English,

British history

The history of the British Isles began with its sporadic human habitation during the Palaeolithic from around 900,000 years ago. The British Isles has been continually occupied since the early Holocene, the current geological epoch, which star ...

, mathematics, science, and Christianity.

Sun was initially unable to speak English, but quickly acquired it, received a prize for academic achievement from King

Kalākaua

Kalākaua (David Laʻamea Kamanakapuʻu Māhinulani Nālaʻiaʻehuokalani Lumialani Kalākaua; November 16, 1836 – January 20, 1891), was the last king and penultimate monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, reigning from February 12, 1874, u ...

, and graduated in 1882.

He then attended

Oahu College (now known as

Punahou School

Punahou School (known as Oahu College until 1934) is a private, co-educational, college preparatory school in Honolulu, Hawaii. More than 3,700 students attend the school from kindergarten through 12th grade. The school was established by P ...

) for one semester.

By 1883, Sun's interest in Christianity had become deeply worrisome for his brother—who, seeing his conversion as inevitable, sent Sun back to China.

Upon returning to China, a 17-year-old Sun met with his childhood friend Lu Haodong at the Beiji Temple () in Cuiheng,

where villagers engaged in traditional

folk healing and worshipped an

effigy

An effigy is a sculptural representation, often life-size, of a specific person or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certain ...

of the

North Star God. Feeling contemptuous of these practices,

Sun and Lu incurred the wrath of their fellow villagers by breaking the wooden idol; as a result, Sun's parents felt compelled to dispatch him to Hong Kong.

In November 1883, Sun began attending the Diocesan Home and Orphanage on

Eastern Street (now the

Diocesan Boys' School

The Diocesan Boys' School (DBS) is a day and boarding Anglican boys' school in Hong Kong, located at 131 Argyle Street, Hong Kong, Argyle Street, Mong Kok, Kowloon. The school's mission is "to provide a liberal education based on Christianity ...

), and from 15 April 1884 he attended The Government Central School on

Gough Street (now

Queen's College), until graduating in 1886.

In 1886, Sun studied medicine at the

Guangzhou Boji Hospital under the Christian missionary

John Glasgow Kerr.

According to his book "Kidnapped in London", in 1887 Sun heard of the opening of the

Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese (the forerunner of the

University of Hong Kong

The University of Hong Kong (HKU) is a public research university in Pokfulam, Hong Kong. It was founded in 1887 as the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese by the London Missionary Society and formally established as the University of ...

).

He immediately sought to attend, and went on to obtain a license to practice medicine from the institution in 1892;

out of a class of twelve students, Sun was one of two who graduated.

['' Singtao Daily''. 28 February 2011. 特別策劃 section A10. "Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition".][''South China Morning Post. "Birth of Sun heralds dawn of revolutionary era for China". 11 November 1999.]

Religious views and Christian baptism

In the early 1880s, Sun Mei had sent his brother to ʻIolani School, which was under the supervision of the

Church of Hawaii and directed by an

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

prelate,

Alfred Willis, with the language of instruction being English. At the school, the young Sun first came in contact with Christianity.

Sun was later

baptized

Baptism (from ) is a Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by sprinkling or pouring water on the head, or by immersing in water either partially or completely, traditionally three ...

in Hong Kong on 4 May 1884 by

Rev. Charles Robert Hager, an American missionary of the

Congregational Church of the United States (

American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions

The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM) was among the first American Christian mission, Christian missionary organizations. It was created in 1810 by recent graduates of Williams College. In the 19th century it was the l ...

), to his brother's disdain. The minister would also develop a friendship with Sun.

[Soong, (1997) p. 151–178] Sun attended To Tsai Church (), founded by the

London Missionary Society

The London Missionary Society was an interdenominational evangelical missionary society formed in England in 1795 at the instigation of Welsh Congregationalist minister Edward Williams. It was largely Reformed tradition, Reformed in outlook, with ...

in 1888,

while he studied medicine in

Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese. Sun pictured a revolution as similar to the salvation mission of the

Christian church

In ecclesiology, the Christian Church is what different Christian denominations conceive of as being the true body of Christians or the original institution established by Jesus Christ. "Christian Church" has also been used in academia as a syn ...

. His conversion to Christianity was related to his revolutionary ideals and push for advancement.

Becoming a revolutionary

Four Bandits

During the Qing-dynasty rebellion around 1888, Sun was in Hong Kong with a group of revolutionary thinkers, nicknamed the

Four Bandits, at the

Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese.

[Bard, Solomon. ''Voices from the past: Hong Kong, 1842–1918''. (2002). HK University Press. . p. 183.]

From Furen Literary Society to Revive China Society

In 1891, Sun met revolutionary friends in Hong Kong including

Yeung Ku-wan who was the leader and founder of the

Furen Literary Society.

[Curthoys, Ann; Lake, Marilyn (2005). ''Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective''. ANU publishing. . p. 101.] The group was spreading the idea of overthrowing the Qing. In 1894, Sun wrote an 8,000-character petition to Qing

Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi ( zh, t=李鴻章; also Li Hung-chang; February 15, 1823 – November 7, 1901) was a Chinese statesman, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in importan ...

presenting his ideas for modernizing China.

[Wei, Julie Lee. Myers Ramon Hawley. Gillin, Donald G. (1994). ''Prescriptions for saving China: selected writings of Sun Yat-sen''. Hoover press. .] He traveled to

Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

to personally present the petition to Li but was not granted an audience. After that experience, Sun turned irrevocably toward revolution. He left China for Hawaii and founded the

Revive China Society

The Revive China Society (), also known as the Society for Regenerating China or the Proper China Society was founded by Sun Yat-sen on 24 November 1894 to forward the goal of establishing prosperity for China and as a platform for future 19 ...

, which was committed to revolutionizing China's prosperity. It was the first Chinese nationalist revolutionary society.

Members were drawn mainly from Chinese expatriates, especially from the lower social classes. The same month in 1894, the Furen Literary Society was merged with the Hong Kong chapter of the Revive China Society.

Thereafter, Sun became the secretary of the newly merged Revive China Society, which Yeung Ku-wan headed as president.

[(Chinese) Yang, Bayun; Yang, Xing'an (2010). ''Yeung Ku-wan – A Biography Written by a Family Member''. Bookoola. p. 17. ] They disguised their activities in Hong Kong under the running of a business under the name "Kuen Hang Club" ().

Heaven and Earth Society and overseas travels to seek financial support

A "Heaven and Earth Society" sect known as

Tiandihui

The Tiandihui, the Heaven and Earth Society, also called Hongmen (the Vast Family), is a Chinese fraternal organization and historically a secretive folk religious sect in the vein of the Ming loyalist White Lotus Sect, the Tiandihu ...

had been around for a long time.

[João de Pina-Cabral. (2002). ''Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao''. Berg publishing. . p. 209.] The group has also been referred to as the "three cooperating organizations", as well as the

triads.

Sun mainly used the group to leverage his overseas travels to gain further financial and resource support for his revolution.

First Sino-Japanese War

In 1895, China suffered a serious defeat during the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First China–Japan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

. There were two types of responses. One group of intellectuals contended that the

Manchu

The Manchus (; ) are a Tungusic peoples, Tungusic East Asian people, East Asian ethnic group native to Manchuria in Northeast Asia. They are an officially recognized Ethnic minorities in China, ethnic minority in China and the people from wh ...

Qing government could restore its legitimacy by successfully modernizing.

[Bevir, Mark (2010). ''Encyclopedia of Political Theory''. Sage publishing. . p 168.] Stressing that overthrowing the Manchu would result in chaos and would lead to China being carved up by imperialists, intellectuals like

Kang Youwei

Kang Youwei (; Cantonese: ''Hōng Yáuh-wàih''; 19March 185831March 1927) was a political thinker and reformer in China of the late Qing dynasty. His increasing closeness to and influence over the young Guangxu Emperor sparked confli ...

and

Liang Qichao

Liang Qichao (Chinese: 梁啓超; Wade–Giles: ''Liang2 Chʻi3-chʻao1''; Yale romanization of Cantonese, Yale: ''Lèuhng Kái-chīu''; ) (February 23, 1873 – January 19, 1929) was a Chinese politician, social and political activist, jour ...

supported responding with initiatives like the

Hundred Days' Reform

The Hundred Days' Reform or Wuxu Reform () was a failed 103-day national, cultural, political, and educational reform movement that occurred from 11 June to 22 September 1898 during the late Qing dynasty. It was undertaken by the young Guangxu Emp ...

.

In another faction, Sun Yat-sen and others like

Zou Rong wanted a revolution to replace the dynastic system with a modern

nation-state

A nation state, or nation-state, is a political entity in which the state (a centralized political organization ruling over a population within a territory) and the nation (a community based on a common identity) are (broadly or ideally) con ...

in the form of a

republic

A republic, based on the Latin phrase ''res publica'' ('public affair' or 'people's affair'), is a State (polity), state in which Power (social and political), political power rests with the public (people), typically through their Representat ...

.

The Hundred Days' reform turned out to be a failure by 1898.

First uprising and exile

First Guangzhou Uprising

In the second year of the establishment of the Revive China Society, on 26 October 1895, the group planned and launched the

First Guangzhou uprising against the Qing in

Guangzhou

Guangzhou, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Canton or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, southern China. Located on the Pearl River about nor ...

.

directed the uprising starting from Hong Kong.

However, plans were leaked out, and more than 70 members, including

Lu Haodong

Lu Zhonggui (30 September 1868 – 7 November 1895), courtesy name Xianxiang, better known by his art name Lu Haodong, was a Chinese revolutionary who lived in the late Qing dynasty. He is best known for designing the Blue Sky with a White Sun ...

, were captured by the Qing government. The uprising was a failure. Sun received financial support mostly from his brother, who sold most of his 12,000 acres of ranch and cattle in Hawaii.

Additionally, members of his family and relatives of Sun would take refuge at the home of his brother Sun Mei at Kamaole in

Kula,

Maui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

.

Exile in the United Kingdom

While in exile in

London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

in 1896, Sun raised money for his revolutionary party and to support uprisings in China. While the events leading up to it are unclear, Sun Yat-sen was detained at the

Chinese Legation in London, where the Chinese secret service planned to smuggle him back to China to execute him for his revolutionary actions. He was released after 12 days by the efforts of

James Cantlie, ''

The Globe'', ''

The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', and the

Foreign Office

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with other countries

* Ministry of Foreign Affairs, in many countries

** Foreign Office, a department of the UK government

** Foreign office and foreign minister

* United ...

, which left Sun a hero in the United Kingdom. James Cantlie, Sun's former teacher at the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, maintained a lifelong friendship with Sun and later wrote an early biography of him Sun wrote a book in 1897 about his detention, "Kidnapped in London."

The bronze plaque of Sun is currently mounted on an outside wall of the building of "City Junior School" at 4 Gray's Inn Place.

Exile in Japan

Sun traveled by way of

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

to

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

to begin his exile there. He arrived in

Yokohama

is the List of cities in Japan, second-largest city in Japan by population as well as by area, and the country's most populous Municipalities of Japan, municipality. It is the capital and most populous city in Kanagawa Prefecture, with a popu ...

on 16 August 1897 and met with the Japanese politician

Tōten Miyazaki. Most Japanese who actively worked with Sun were motivated by a

pan-Asian

Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism) is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asiani ...

opposition to

Western imperialism

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism foc ...

. In Japan, Sun also met

Mariano Ponce

Mariano Ponce y Collantes (; March 22, 1863 – May 23, 1918) commonly known as just Mariano Ponce was a Filipino physician, writer, statesman, and active member of the Propaganda Movement. In Spain, he was among the founders of ''La Solidarid ...

, a diplomat of the

First Philippine Republic

The Philippine Republic (), now officially remembered as the First Philippine Republic and also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was a state established in Malolos, Bulacan, during the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish ...

.

During the

Philippine Revolution

The Philippine Revolution ( or ; or ) was a war of independence waged by the revolutionary organization Katipunan against the Spanish Empire from 1896 to 1898. It was the culmination of the 333-year History of the Philippines (1565–1898), ...

and the

Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

, Sun helped Ponce procure weapons that had been salvaged from the

Imperial Japanese Army

The Imperial Japanese Army (IJA; , ''Dai-Nippon Teikoku Rikugun'', "Army of the Greater Japanese Empire") was the principal ground force of the Empire of Japan from 1871 to 1945. It played a central role in Japan’s rapid modernization during th ...

and ship the weapons to the Philippines. By helping the Philippine Republic, Sun hoped that the Filipinos would retain their independence so that he could be sheltered in the country in staging another Chinese revolution. However, as the war ended in July 1902, the United States emerged victorious from a bitter three-year war against the Republic. Therefore, Sun did not have the opportunity to ally with the Philippines in his revolution in China.

In 1897, through an introduction by

Miyazaki Toten, Sun Yat-sen met

Tōyama Mitsuru

was a Japanese far right and ultra nationalist politician who founded secret societies called Genyosha ('' Black Ocean Society'') and Kokuryukai (''Black Dragon Society''). Tōyama was an Anti Communist and a strong proponent of Pan Asianism ...

of the political organization

Genyosha. Through Tōyama, he received financial support for his activities and living expenses in Tokyo from . Additionally, his residence, a 2,000-square-meter mansion in Waseda-Tsurumaki-cho, was arranged by

Inukai Tsuyoshi

Inukai Tsuyoshi (, 4 June 1855 – 15 May 1932) was a Japanese statesman who was Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1931 to his assassination in 1932. At the age of 76, Inukai was Japan's second oldest serving prime minister, ...

.

In 1899, the

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

occurred. The following year, Sun Yat-sen attempted another uprising in Huizhou, but it ended in failure. In 1902, despite already having a wife in China, he married the

Japanese teenage girl

Kaoru Otsuki.

Furthermore, he kept as a mistress and frequently had her accompany him.

From failed uprisings to revolution

Huizhou Uprising

On 22 October 1900, Sun ordered the launch of the

Huizhou Uprising to attack

Huizhou

Huizhou ( zh, c= ) is a city in east-central Guangdong Province, China, forty-three miles north of Hong Kong. Huizhou borders the provincial capital of Guangzhou to the west, Shenzhen and Dongguan to the southwest, Shaoguan to the north, Hey ...

and provincial authorities in Guangdong. That came five years after the failed Guangzhou Uprising. This time, Sun appealed to the

triads for help. The uprising was another failure. Miyazaki, who participated in the revolt with Sun, wrote an account of the revolutionary effort under the title "33-Year Dream" () in 1902.

Getting support from Siamese Chinese

In 1903, Sun made a secret trip to

Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai language, Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estim ...

in which he sought funds for his cause in Southeast Asia. His loyal followers published newspapers, providing invaluable support to the dissemination of his revolutionary principles and ideals among

Siamese Chinese in

Siam

Thailand, officially the Kingdom of Thailand and historically known as Siam (the official name until 1939), is a country in Southeast Asia on the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese Peninsula. With a population of almost 66 million, it spa ...

. In Bangkok, Sun visited

Yaowarat Road

Yaowarat Road (, , ; ) in Samphanthawong District is the main artery of Bangkok's Chinatown. Modern Chinatown now covers a large area around Yaowarat and Charoen Krung Road. It has been the main centre for trading by the Chinese community si ...

, in the city's

Chinatown

Chinatown ( zh, t=唐人街) is the catch-all name for an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, Asia, Africa, O ...

. On that street, Sun gave a speech claiming that

Overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese people are Chinese people, people of Chinese origin who reside outside Greater China (mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan). As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese. As of 2023, there were 10.5 milli ...

were "the Mother of the Revolution." He also met the local Chinese merchant Seow Houtseng, who sent financial support to him.

Sun's speech on Yaowarat Road was commemorated by the street later being named "Sun Yat Sen Street" or "Soi Sun Yat Sen" () in his honour.

Getting support from American Chinese

According to Lee Yun-ping, chairman of the Chinese historical society, Sun needed a certificate to enter the United States since the

Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 would have otherwise blocked him.

In March 1904, while residing in

Kula,

Maui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

, Sun Yat-sen obtained a Certificate of Hawaiian Birth, issued by the

Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territories of the United States, organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from Apri ...

, stating that "he was born in the

Hawaiian Islands

The Hawaiian Islands () are an archipelago of eight major volcanic islands, several atolls, and numerous smaller islets in the Pacific Ocean, North Pacific Ocean, extending some from the Hawaii (island), island of Hawaii in the south to nort ...

on the 24th day of November, A.D. 1870."

He renounced it after it served its purpose to circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act.

[Smyser, A.A. (2000)]

''Sun Yat-sen's strong links to Hawaii''

Honolulu Star Bulletin. "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898." Official files of the United States show that Sun had United States nationality, moved to China with his family at age 4, and returned to Hawaii 10 years later.

[ Note that one immigration official recorded that Sun was born in Kula, a district of ]Maui

Maui (; Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ) is the second largest island in the Hawaiian archipelago, at 727.2 square miles (1,883 km2). It is the List of islands of the United States by area, 17th-largest in the United States. Maui is one of ...

, Hawaii.

On 6 April 1904, on his first attempt to enter the United States, Sun Yat-sen landed in

San Francisco

San Francisco, officially the City and County of San Francisco, is a commercial, Financial District, San Francisco, financial, and Culture of San Francisco, cultural center of Northern California. With a population of 827,526 residents as of ...

. He was detained and faced with possible deportation.

Sun, represented by the law firm of Ralston & Siddons, based in

Washington DC

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and Federal district of the United States, federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from ...

, filed an appeal with the Commissioner-General of Immigration on 26 April 1904. On 28 April 1904, the acting secretary of the

Department of Commerce and Labor

The United States Department of Commerce and Labor was a short-lived United States Cabinet, Cabinet department of the United States Government of the United States, government, which was concerned with fostering and supervising big business. It ...

in a four-page decision contained in the case file, set aside the order of deportation and ordered the Commissioner of Immigration in San Francisco to "permit the said Sun Yat-sen to land." Sun was then freed to embark on his fundraising tour in the United States.

Returned to exile in Japan

In 1900, Sun Yat-sen temporarily

exile

Exile or banishment is primarily penal expulsion from one's native country, and secondarily expatriation or prolonged absence from one's homeland under either the compulsion of circumstance or the rigors of some high purpose. Usually persons ...

d himself to Japan again. During his stay in Japan, he expressed his thoughts to

Inukai Tsuyoshi

Inukai Tsuyoshi (, 4 June 1855 – 15 May 1932) was a Japanese statesman who was Prime Minister of Japan, prime minister of Japan from 1931 to his assassination in 1932. At the age of 76, Inukai was Japan's second oldest serving prime minister, ...

, saying, "The

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored Imperial House of Japan, imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Althoug ...

is the first step of the Chinese revolution, and the Chinese revolution is the second step of the Meiji Restoration."

Around this time, Sun married

Soong Ching-ling

Soong Ch'ing-ling (27 January 1893 – 29 May 1981), Christian name Rosamonde or Rosamond, was a Chinese political figure. She was the wife of Sun Yat-sen, therefore known by Madame Sun Yat-sen and the "''Father of the Nation, Mother of Mode ...

, the second daughter of

Soong Jiashu, who was also a Hakka like him. There are various theories about the year of their marriage, but it is generally believed to have taken place between

1913

Events January

* January – Joseph Stalin travels to Vienna to research his ''Marxism and the National Question''. This means that, during this month, Stalin, Hitler, Trotsky and Tito are all living in the city.

* January 3 &ndash ...

and

1916

Events

Below, the events of the First World War have the "WWI" prefix.

January

* January 1 – The British Empire, British Royal Army Medical Corps carries out the first successful blood transfusion, using blood that has been stored ...

while Sun was exiled in Japan. The arrangement of their marriage was supported by

Umeya Shokichi, a Japanese supporter who provided financial aid.

[2007年2月25日NHK BS1 『世界から見たニッポン~大正編』]

At that time,

Fusanosuke Kuhara, a prominent figure in Japan's political and business circles, invited Sun to his villa, the Nihonkan, located where the current restaurant "Kochuan" in Shirokane Happo-en stands. Kuhara offered Sun the newly built "Orchid Room" to encourage and support his friend living in a foreign land.

The Orchid Room was equipped with a secret escape route known as "Sun Yat-sen's Escape Passage." This precautionary measure included a hidden door behind the fireplace, which led to an underground tunnel, providing an escape route in case of emergencies.

Unifying forces of Tongmenghui in Tokyo

In 1904, Sun Yat-sen came about with the goal "to expel the

Tatar barbarians (specifically, the Manchu), to revive

Zhonghua, to establish a Republic, and to

distribute land equally among the people" ().

[計秋楓, 朱慶葆. (2001). 中國近代史, Volume 1. Chinese University Press. . p. 468.] One of Sun's major legacies was the creation of his political philosophy of the

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (), also known as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, San Min Chu-i, or Tridemism is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China during the Republi ...

. These Principles included the principle of nationalism (minzu, ), of democracy (minquan, ), and of welfare (minsheng, ).

On 20 August 1905, Sun joined forces with revolutionary Chinese students studying in Tokyo to form the unified group

Tongmenghui

The Tongmenghui of China was a secret society and underground resistance movement founded by Sun Yat-sen, Song Jiaoren, and others in Tokyo, Empire of Japan, on 20 August 1905, with the goal of overthrowing China's Qing dynasty. It was formed ...

(United League), which sponsored uprisings in China.

By 1906 the number of Tongmenghui members reached 963.

Getting support from Malayan Chinese

Sun's notability and popularity extended beyond the

Greater China

In ethnogeography, "Greater China" is a loosely-defined term that refers to the region sharing cultural and economic ties with the Chinese people, often used by international enterprises or organisations in unofficial usage. The notion contains ...

region, particularly to

Nanyang (Southeast Asia), where a large concentration of

overseas Chinese

Overseas Chinese people are Chinese people, people of Chinese origin who reside outside Greater China (mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan). As of 2011, there were over 40.3 million overseas Chinese. As of 2023, there were 10.5 milli ...

resided in

Malaya (

Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

and Singapore). In Singapore, he met the local Chinese merchants Teo Eng Hock (), Tan Chor Nam () and Lim Nee Soon (), which mark the commencement of direct support from the

Nanyang Chinese. The Singapore chapter of the Tongmenghui was established on 6 April 1906,

[Yan, Qinghuang. (2008). ''The Chinese in Southeast Asia and beyond: socioeconomic and political dimensions''. World Scientific publishing.. pp. 182–187.] but some records claim the founding date to be end of 1905.

The

villa

A villa is a type of house that was originally an ancient Roman upper class country house that provided an escape from urban life. Since its origins in the Roman villa, the idea and function of a villa have evolved considerably. After the f ...

used by Sun was known as

Wan Qing Yuan.

Singapore then was the headquarters of the Tongmenghui.

After founding the Tongmenghui, Sun advocated the establishment of the ''

Chong Shing Yit Pao'' as the alliance's mouthpiece to promote revolutionary ideas. Later, he initiated the establishment of reading clubs across Singapore and Malaysia to disseminate revolutionary ideas by the lower class through public readings of newspaper stories. The United Chinese Library, founded on 8 August 1910, was one such reading club, first set up at leased property on the second floor of the Wan He Salt Traders in North Boat Quay.

The first actual United Chinese Library building was built between 1908 and 1911 below Fort Canning, on 51 Armenian Street, and commenced operations in 1912. The library was set up as a part of the 50 reading rooms by the Chinese republicans to serve as an information station and liaison point for the revolutionaries. In 1987, the library was moved to its present site at Cantonment Road.

Uprisings

On 1 December 1907, Sun led the

Zhennanguan Uprising against the Qing at

Friendship Pass

Friendship Pass (), also commonly known by its older name Ải Nam Quan (), is a pass near the China-Vietnam border, between China's Guangxi and Vietnam's Lạng Sơn province. The pass itself lies just inside the Chinese side of the border ...

, which is the border between

Guangxi

Guangxi,; officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam (Hà Giang Province, Hà Giang, Cao Bằn ...

and

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

.

[Khoo, Salma Nasution. (2008). ''Sun Yat Sen in Penang''. Areca publishing. .] The uprising failed after seven days of fighting.

In 1907, there were a total of four failed uprisings, including

Huanggang uprising,

Huizhou seven women lake uprising and

Qinzhou uprising.

In 1908, two more uprisings failed: the

Qin-lian Uprising and

Hekou Uprising.

Anti-Sun factionalism

Because of the failures, Sun's leadership was challenged by elements from within the Tongmenghui who wished to remove him as leader. In Tokyo, members from the recently merged

Restoration society raised doubts about Sun's credentials.

and

Zhang Binglin

Zhang Binglin (January 12, 1869 – June 14, 1936), also known by his art name Zhang Taiyan, was a Chinese philologist, textual critic, philosopher, and revolutionary.

His philological works include ''Wen Shi'' (文始 "The Origin of Writing"), ...

publicly denounced Sun in an open leaflet, "A declaration of Sun Yat-sen's Criminal Acts by the Revolutionaries in Southeast Asia",

which was printed and distributed in reformist newspapers like ''Nanyang Zonghui Bao''.

The goal was to target Sun as a leader leading a revolt only for

profiteering

Profiteering is a pejorative term for the act of making a profit by methods considered unethical.

Overview

Business owners may be accused of profiteering when they raise prices during an emergency ( especially a war). The term is also applied to ...

.

The revolutionaries were polarized and split between pro-Sun and anti-Sun camps.

Sun publicly fought off comments about how he had something to gain financially from the revolution.

However, by 19 July 1910, the Tongmenghui headquarters had to relocate from Singapore to Penang to reduce the anti-Sun activities.

It was also in Penang that Sun and his supporters would launch the first Chinese "daily" newspaper, the ''

Kwong Wah Yit Poh

''Kwong Wah Yit Poh'' or ''Kwong Wah Daily'' () is a Malaysian Chinese daily that was founded in 1910 by Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen. It is the oldest surviving Chinese-language newspaper in Southeast Asia.

History

Background

During ...

'', in December 1910.

1911 revolution

To sponsor more uprisings, Sun made a personal plea for financial aid at the

Penang conference, held on 13 November 1910 in Malaya.

[ Bergère: 188] The high-powered preparatory meeting of Sun's supporters was subsequently held in Ipoh, Singapore, at the villa of Teh Lay Seng, the chairman of the Tungmenghui, to raise funds for the

Huanghuagang Uprising, also known as the Yellow Flower Mound Uprising. The Ipoh leaders were Teh Lay Seng, Wong I Ek, Lee Guan Swee, and Lee Hau Cheong. The leaders launched a major drive for donations across the

Malay Peninsula

The Malay Peninsula is located in Mainland Southeast Asia. The landmass runs approximately north–south, and at its terminus, it is the southernmost point of the Asian continental mainland. The area contains Peninsular Malaysia, Southern Tha ...

and raised

HK$187,000.

On 27 April 1911, the revolutionary

Huang Xing

Huang Xing or Huang Hsing (; 25 October 1874 – 31 October 1916) was a Chinese revolutionary leader and politician, and the first commander-in-chief of the Republic of China. As one of the founders of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Republic of ...

led the

Yellow Flower Mound Uprising against the Qing. The revolt failed and ended in disaster. The bodies of only 72 revolutionaries were identified of the 86 that were found.

[王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. . pp. 195–198.] The revolutionaries are remembered as

martyrs

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

.

Despite the failure of this uprising, which was due to a leak, it was successful in triggering off the trend of nation-wide revolts.

On 10 October 1911, the military

Wuchang Uprising

The Wuchang Uprising was an armed rebellion against the ruling Qing dynasty that took place in Wuchang (now Wuchang District of Wuhan) in the Chinese province of Hubei on 10 October 1911, beginning the Xinhai Revolution that successfully overthr ...

took place and was led again by Huang Xing. The uprising expanded to the

Xinhai Revolution

The 1911 Revolution, also known as the Xinhai Revolution or Hsinhai Revolution, ended China's last imperial dynasty, the Qing dynasty, and led to the establishment of the Republic of China (ROC). The revolution was the culmination of a decade ...

, also known as the "Chinese Revolution", to overthrow the last emperor,

Puyi

Puyi (7 February 190617 October 1967) was the final emperor of China, reigning as the eleventh monarch of the Qing dynasty from 1908 to 1912. When the Guangxu Emperor died without an heir, Empress Dowager Cixi picked his nephew Puyi, aged tw ...

. Sun had no direct involvement in it, as he was in

Denver

Denver ( ) is a List of municipalities in Colorado#Consolidated city and county, consolidated city and county, the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Colorado, most populous city of the U.S. state of ...

,

Colorado

Colorado is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States. It is one of the Mountain states, sharing the Four Corners region with Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. It is also bordered by Wyoming to the north, Nebraska to the northeast, Kansas ...

, and had spent much of the year in the United States in search of support from

Chinese Americans

Chinese Americans are Americans of Chinese ancestry. Chinese Americans constitute a subgroup of East Asian Americans which also constitute a subgroup of Asian Americans. Many Chinese Americans have ancestors from mainland China, Hong Kong ...

. That put Huang in charge of the revolution that ended over 2000 years of imperial rule in China. On 12 October, when Sun learned of the successful rebellion against the Qing emperor from press reports, he returned to China from the United States and was accompanied by his closest foreign advisor, the American "General"

Homer Lea, an adventurer whom Sun had met in London when they attempted to arrange British financing for the future Chinese republic. Both sailed for China, arriving there on 21 December 1911.

Republic of China with multiple governments

Provisional government

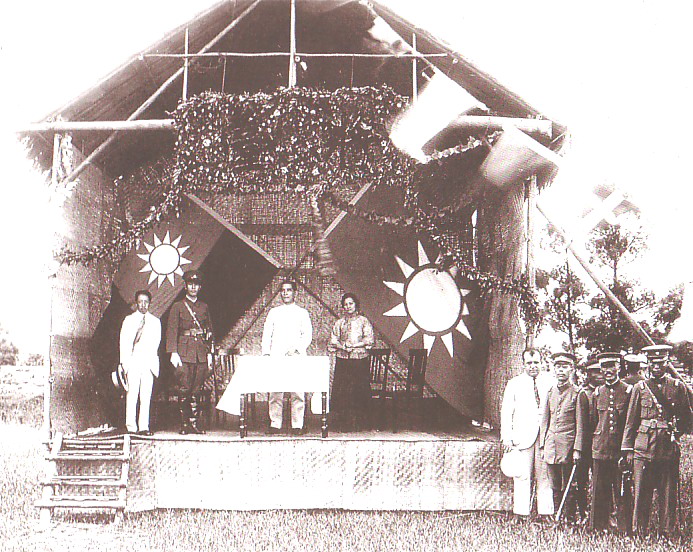

On 29 December 1911, a meeting of representatives from provinces in Nanjing elected Sun as the

provisional president. 1 January 1912 was set as the

epoch

In chronology and periodization, an epoch or reference epoch is an instant in time chosen as the origin of a particular calendar era. The "epoch" serves as a reference point from which time is measured.

The moment of epoch is usually decided b ...

of the new

republican calendar.

[Welland, Sasah Su-ling. (2007). ''A Thousand Miles of Dreams: The Journeys of Two Chinese Sisters''. Rowman Littlefield Publishing. . p. 87.] Li Yuanhong

Li Yuanhong (; courtesy name ; October 19, 1864 – June 3, 1928) was a prominent Chinese military and political leader during the Qing Dynasty and the Republic of China. He was the Provisional Vice President of the Republic of China from 191 ...

was made provisional vice-president, and Huang Xing became the minister of the army. It was argued Sun was a 'compromise candidate' to end an impasse and power struggle between Li Yuanhong and Huang Xing over the role of the Generalissimo. A new

provisional government

A provisional government, also called an interim government, an emergency government, a transitional government or provisional leadership, is a temporary government formed to manage a period of transition, often following state collapse, revoluti ...

for the Republic of China was created, along with a

provisional constitution. Sun is credited for funding the revolutions and for keeping revolutionary spirit alive, even after a series of false starts. His successful merger of smaller revolutionary groups into a single coherent party provided a better base for those who shared revolutionary ideals. Under Sun's provisional government, several innovations were introduced, such as the aforementioned calendar system, and fashionable

Zhongshan suits.

Beiyang government

Yuan Shikai

Yuan Shikai (; 16 September 18596 June 1916) was a Chinese general and statesman who served as the second provisional president and the first official president of the Republic of China, head of the Beiyang government from 1912 to 1916 and ...

, who was in control of the

Beiyang Army

The Beiyang Army (), named after the Beiyang region, was a Western-style Imperial Chinese Army established by the Qing dynasty in the early 20th century. It was the centerpiece of a general reconstruction of the Qing military system in the wake ...

, had been promised the position of president of the Republic of China if he could get the Qing court to abdicate.

On 12 February 1912, the Emperor did abdicate the throne.

Sun stepped down as president, and Yuan became the new provisional president in Beijing on 10 March 1912.

The provisional government did not have any military forces of its own. Its control over elements of the new army that had mutinied was limited, and significant forces still had not declared against the Qing.

Sun Yat-sen sent telegrams to the leaders of all provinces to request them to elect and to establish the

National Assembly in 1912. In May 1912, the legislative assembly moved from Nanjing to Beijing, with its 120 members divided between members of the Tongmenghui and a republican party that supported Yuan Shikai.

[Ch'ien Tuan-sheng. ''The Government and Politics of China 1912–1949''. Harvard University Press, 1950; rpr. Stanford University Press. . pp. 83–91.] Many revolutionary members were already alarmed by Yuan's ambitions and the northern-based

Beiyang government

The Beiyang government was the internationally recognized government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China between 1912 and 1928, based in Beijing. It was dominated by the generals of the Beiyang Army, giving it its name.

B ...

.

New Nationalist party in 1912, failed Second Revolution and new exile

The Tongmenghui member

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren (, ; Chinese name, Given name at birth: Liàn 鍊; Courtesy name: Dùnchū 鈍初; 5 April 1882 – 22 March 1913) was a Republic of China (1912–1949), Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuom ...

quickly tried to control the assembly. He mobilized the old Tongmenghui at the core with the mergers of a number of new small parties to form a new political party, the

Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

(Chinese Nationalist Party, commonly abbreviated as "KMT") on 25 August 1912 at

Huguang Guild Hall

The Huguang Guild Hall () in Beijing is one of Beijing's most renowned Peking opera theaters.

History

Built in 1807, and at the height of its glory, the Huguang Guild Hall, along with the Zhengyici Peking Opera Theater was known as one of the ...

, Beijing.

The

1912–1913 National assembly election was considered a huge success for the KMT, which won 269 of the 596 seats in the lower house and 123 of the 274 seats in the upper house.

[Fu, Zhengyuan. (1993). ''Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics''(Cambridge University Press. ). pp. 153–154.] In retaliation, the KMT leader

Song Jiaoren

Song Jiaoren (, ; Chinese name, Given name at birth: Liàn 鍊; Courtesy name: Dùnchū 鈍初; 5 April 1882 – 22 March 1913) was a Republic of China (1912–1949), Chinese republican revolutionary, political leader and a founder of the Kuom ...

was assassinated, almost certainly by a secret order of Yuan, on 20 March 1913.

The

Second Revolution took place by Sun and KMT military forces trying to overthrow Yuan's forces of about 80,000 men in an armed conflict in July 1913. The revolt against Yuan was unsuccessful. In August 1913, Sun fled to Japan, where he later enlisted financial aid by the politician and industrialist

Fusanosuke Kuhara.

Warlords chaos

In 1915, Yuan proclaimed the

Empire of China with himself as

Emperor of China

Throughout Chinese history, "Emperor" () was the superlative title held by the monarchs of imperial China's various dynasties. In traditional Chinese political theory, the emperor was the " Son of Heaven", an autocrat with the divine mandat ...

. Sun took part in the

National Protection War

The National Protection War ( zh, t=護國戰爭, s=护国战争, p=Hù guó zhànzhēng), also known as the Anti-Monarchy War, was a civil war that took place in China between 1915 and 1916. Following the overthrow of the Qing dynasty three yea ...

of the

Constitutional Protection Movement

The Constitutional Protection Movement () was a series of movements led by Sun Yat-sen to resist the Beiyang government between 1917 and 1922, in which Sun established another government in Guangzhou as a result. It was known as the Fourth Revolut ...

and also supported bandit leaders like

Bai Lang during the

Bai Lang Rebellion, which marked the beginning of the

Warlord Era

The Warlord Era was the period in the history of the Republic of China between 1916 and 1928, when control of the country was divided between rival Warlord, military cliques of the Beiyang Army and other regional factions. It began after the de ...

. In 1915, Sun wrote to the

Second International

The Second International, also called the Socialist International, was a political international of Labour movement, socialist and labour parties and Trade union, trade unions which existed from 1889 to 1916. It included representatives from mo ...

, a

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

-based organization in

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, and asked it to send a team of specialists to help China set up the world's first socialist republic. The same year, Sun received the

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n communist

M.N. Roy as a guest. There were then

many theories and proposals of what China could be. In the political mess, both Sun Yat-sen and

Xu Shichang

Xu Shichang (Hsu Shih-chang; ; courtesy name: Juren (Chu-jen; 菊人); October 20, 1855 – June 5, 1939) was a Chinese politician who served as the President of the Republic of China, in Beijing, from 10 October 1918 to 2 June 1922. The only p ...

were announced as president of the Republic of China.

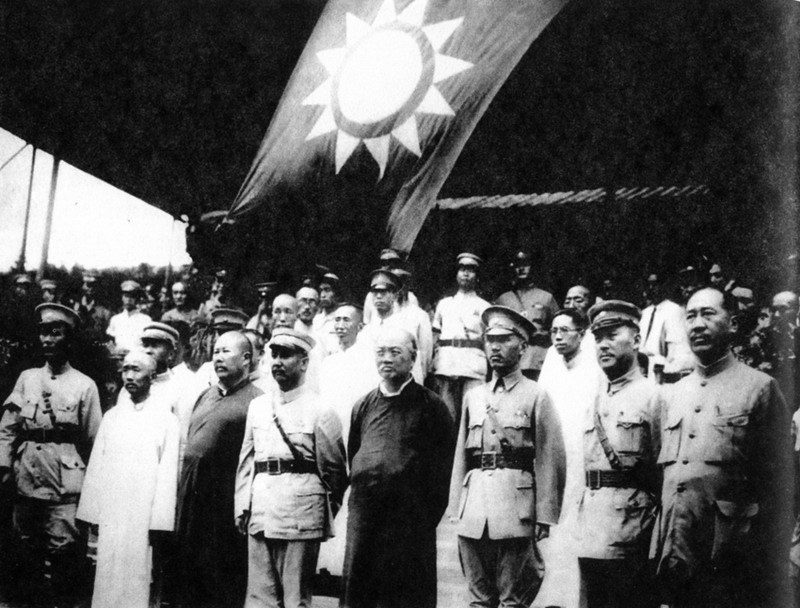

Alliance with Communist Party and Northern Expedition

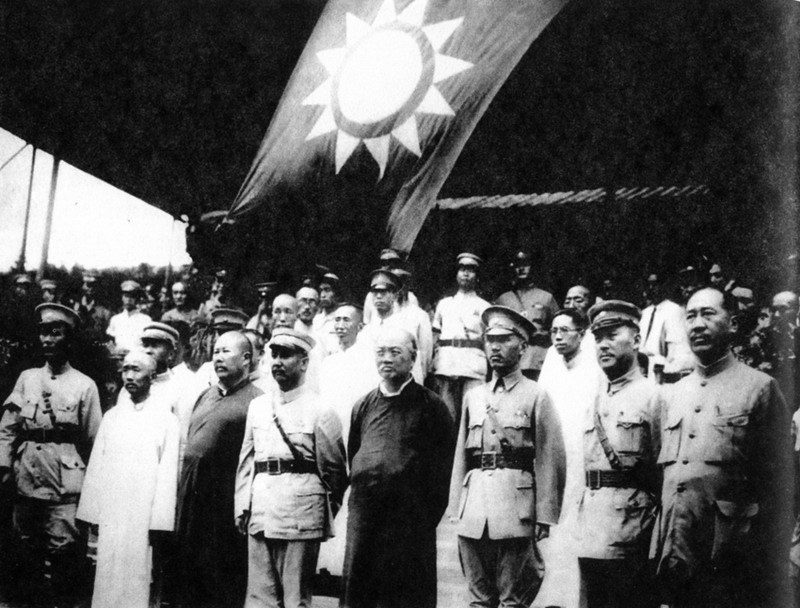

Guangzhou militarist government

China had become divided among regional military leaders. Sun saw the danger and returned to China in 1916 to advocate

Chinese reunification. In 1921, he started a

self-proclaimed military government in

Guangzhou

Guangzhou, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Canton or Kwangchow, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Guangdong Provinces of China, province in South China, southern China. Located on the Pearl River about nor ...

and was elected

Grand Marshal.

[ Bergère & Lloyd: 273] According to historian William C. Kirby, between 1912 and 1927, three governments were set up in South China: the

Provisional government in Nanjing (1912), the

Military government in Guangzhou (1923–1925), and the

National government in Guangzhou and later Wuhan (1925–1927). The governments in the south were established to rival the Beiyang government in the north.

Yuan Shikai had banned the KMT. The short-lived

Chinese Revolutionary Party was a temporary replacement for the KMT. On 10 October 1919, Sun resurrected the KMT with the new name

Chung-kuo Kuomintang

The Kuomintang (KMT) is a major political party in the Republic of China (Taiwan). It was the one party state, sole ruling party of the country Republic of China (1912-1949), during its rule from 1927 to 1949 in Mainland China until Retreat ...

, or "Nationalist Party of China."

First United Front

Sun was now convinced that the only hope for a unified China lay in a military conquest from his base in the south, followed by a period of , which would culminate in the transition to democracy. To hasten the conquest of China, he began a policy of active co-operation with the

Chinese Communist Party

The Communist Party of China (CPC), also translated into English as Chinese Communist Party (CCP), is the founding and One-party state, sole ruling party of the People's Republic of China (PRC). Founded in 1921, the CCP emerged victorious in the ...

(CCP). Sun and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

's

Adolph Joffe

Adolph Abramovich Joffe (; alternatively transliterated as Adolf Ioffe or Yoffe; 10 October 1883 – 16 November 1927) was a Russian revolutionary, Bolshevik politician and Soviet diplomat of Karaite descent.

Biography Revolutionary career ...

signed the

Sun-Joffe Manifesto in January 1923.

[Tung, William L. (1968). ''The political institutions of modern China''. Springer publishing. . pp. 92, 106.] Sun received help from the

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

for his acceptance of communist members into his KMT. Sun received assistance from Soviet advisor

Mikhail Borodin

Mikhail Markovich Gruzenberg, known by the alias Borodin (9 July 1884 – 29 May 1951), was a Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist International (Comintern) agent. He was an advisor to Sun Yat-sen and the Kuomintang (KMT) in China during the ...

, whom Sun described as his "

Lafayette".

The Russian revolutionary and socialist leader

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

praised Sun and his KMT for its ideology, principles, attempts at social reformation, and fight against foreign imperialism. Sun also returned the praise by calling Lenin a "great man" and indicated that he wished to follow the same path as Lenin. In 1923, after having been in contact with Lenin and other Moscow communists, Sun sent representatives to study the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

, and in turn, the Soviets sent representatives to help reorganize the KMT at Sun's request.

With the Soviets' help, Sun was able to develop the military power needed for the

Northern Expedition

The Northern Expedition was a military campaign launched by the National Revolutionary Army (NRA) of the Kuomintang (KMT) against the Beiyang government and other regional warlords in 1926. The purpose of the campaign was to reunify China prop ...

against the military at the north. He established the

Whampoa Military Academy

The Republic of China Military Academy ( zh, t=中華民國陸軍軍官學校, p=Zhōnghúa Mīngúo Lùjūn Jūnguān Xúexiào, poj=Tiong-hôa Bîn-kok Lio̍k-kun Kun-koaⁿ Ha̍k-hāu), also known as the Chinese Military Academy (CMA), is ...

near Guangzhou with

Chiang Kai-shek as the

commandant

Commandant ( or ; ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ...

of the

National Revolutionary Army

The National Revolutionary Army (NRA; zh, labels=no, t=國民革命軍) served as the military arm of the Kuomintang, Chinese Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, or KMT) from 1924 until 1947.

From 1928, it functioned as the regular army, de facto ...

(NRA). Other Whampoa leaders include

Wang Jingwei

Wang Zhaoming (4 May 188310 November 1944), widely known by his pen name Wang Jingwei, was a Chinese politician who was president of the Reorganized National Government of the Republic of China, a puppet state of the Empire of Japan. He was in ...

and

Hu Hanmin

Hu Hanmin (; 9 December 1879 – 12 May 1936) was a Chinese philosopher and politician who was one of the early conservative right-wing faction leaders in the Kuomintang (KMT) during revolutionary China.

Biography

Hu was of Hakka descent fro ...

as political instructors. This full collaboration was called the

First United Front

The First United Front , also known as the KMT–CCP Alliance, of the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was formed in 1924 as an alliance to end Warlord Era, warlordism in China. Together they formed the National Revolution ...

.

Financial concerns

In 1924 Sun appointed his brother-in-law

T. V. Soong to set up the first Chinese central bank, the

Canton Central Bank. To establish national capitalism and a banking system was a major objective for the KMT. However, Sun met opposition by the

Canton Merchant Volunteers Corps Uprising against him.

Final years

Final speeches

In February 1923, Sun made a presentation to the

Students' Union

A students' union or student union, is a student organization present in many colleges, universities, and high schools. In higher education, the students' union is often accorded its own building on the campus, dedicated to social, organizat ...

in

Hong Kong University

The University of Hong Kong (HKU) is a public research university in Pokfulam, Hong Kong. It was founded in 1887 as the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese by the London Missionary Society and formally established as the University of ...

and declared that the corruption of China and the

peace, order, and good government of Hong Kong had turned him into a revolutionary. The same year, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed his

Three Principles of the People

The Three Principles of the People (), also known as the Three People's Principles, San-min Doctrine, San Min Chu-i, or Tridemism is a political philosophy developed by Sun Yat-sen as part of a philosophy to improve China during the Republi ...

as the foundation of the country and the

Five-Yuan Constitution as the guideline for the political system and bureaucracy. Part of the speech was made into the

National Anthem of the Republic of China

The "National Anthem of the Republic of China", also known by its incipit "Three Principles of the People", is the national anthem of the Republic of China, commonly called Taiwan, as well as the party anthem of the Kuomintang. It was adop ...

.

On 10 November 1924, Sun traveled north to

Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

and delivered a speech to suggest a gathering for a "national conference" for the Chinese people. He called for the end of warlord rules and the abolition of all

unequal treaties

The unequal treaties were a series of agreements made between Asian countries—most notably Qing China, Tokugawa Japan and Joseon Korea—and Western countries—most notably the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, the Unit ...

with the

Western powers. Two days later, he traveled to Beijing to discuss the future of the country despite his deteriorating health and the ongoing civil war of the warlords. Among the people whom he met was the Muslim warlord General

Ma Fuxiang

Ma Fuxiang (, Xiao'erjing: , French romanization: Ma-Fou-hiang or Ma Fou-siang; 4 February 1876 – 19 August 1932) was a Chinese Muslim scholar and military and political figure, spanning from the Qing Dynasty through the early Republic of ...

, who informed Sun that he would welcome Sun's leadership. On 28 November 1924 Sun traveled to Japan and gave a

speech on Pan-Asianism at

Kobe

Kobe ( ; , ), officially , is the capital city of Hyōgo Prefecture, Japan. With a population of around 1.5 million, Kobe is Japan's List of Japanese cities by population, seventh-largest city and the third-largest port city after Port of Toky ...

, Japan.

Illness and death

For many years, it was popularly believed that Sun died of

liver cancer

Liver cancer, also known as hepatic cancer, primary hepatic cancer, or primary hepatic malignancy, is cancer that starts in the liver. Liver cancer can be primary in which the cancer starts in the liver, or it can be liver metastasis, or secondar ...

. On 26 January 1925, Sun underwent an

exploratory laparotomy

An exploratory laparotomy is a general surgical operation where the abdomen is opened and the abdominal organs are examined for injury or disease. It is the standard of care in various blunt and penetrating trauma situations in which there may b ...

at