Sultanate Of Morocco (1665-1912) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Alawi Sultanate, officially known as the Sharifian Sultanate () and as the Sultanate of Morocco, was the state ruled by the '

By this time, the Dala'iyya's realm, which once extended over Fez and most of central Morocco, had largely receded to their original home in the Middle Atlas. Al-Rashid was left in control of the 'Alawi forces and in less than a decade he managed to extend 'Alawi control over almost all of Morocco, reuniting the country under a new sharifian dynasty. Early on, he won over more rural Arab tribes to his side and integrated them into his military system. Also known as ''

By this time, the Dala'iyya's realm, which once extended over Fez and most of central Morocco, had largely receded to their original home in the Middle Atlas. Al-Rashid was left in control of the 'Alawi forces and in less than a decade he managed to extend 'Alawi control over almost all of Morocco, reuniting the country under a new sharifian dynasty. Early on, he won over more rural Arab tribes to his side and integrated them into his military system. Also known as ''

He also moved the capital from Fez to

He also moved the capital from Fez to

Muhammad IV also reorganized the state and began to institutionalize a more professional, regular administration and military, often by following Western European models. This trend was taken further by his talented successor, Hassan I (). Hassan I also campaigned tirelessly to collect tax revenues and reimpose central rule on outlying provinces.

In the latter part of the 19th century Morocco's instability resulted in European countries intervening to protect investments and to demand economic concessions. Hassan I called for the

Muhammad IV also reorganized the state and began to institutionalize a more professional, regular administration and military, often by following Western European models. This trend was taken further by his talented successor, Hassan I (). Hassan I also campaigned tirelessly to collect tax revenues and reimpose central rule on outlying provinces.

In the latter part of the 19th century Morocco's instability resulted in European countries intervening to protect investments and to demand economic concessions. Hassan I called for the

In Bilad el-Makhzen,

In Bilad el-Makhzen,

Alawi dynasty

The Alawi dynasty () – also rendered in English as Alaouite, Alawid, or Alawite – is the current Moroccan royal family and reigning dynasty. They are an Arab Sharifian dynasty and claim descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his ...

over what is now Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, from their rise to power in the 1660s to the 1912 Treaty of Fes that marked the start of the French protectorate.

The dynasty, which remains the ruling monarchy of Morocco today, originated from the Tafilalt

Tafilalt or Tafilet (), historically Sijilmasa, is a region of Morocco, centered on its largest oasis.

Etymology

There are many speculations regarding the origin of the word "Tafilalt", however it is known that Tafilalt is a Berber word meaning ...

region and rose to power following the collapse of the Saadi Sultanate

The Saadi Sultanate (), also known as the Sharifian Sultanate (), was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of Northwest Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was led by the Saadi dynasty, an Arab Sharifian dynasty.

The dyna ...

in the 17th century. Sultan al-Rashid () was the first to establish his authority over the entire country. The sultanate reached an apogee of political power during the reign of his successor, Moulay Isma'il (), who exercised strong central rule.

After Isma'il's death, Morocco underwent periods of turmoil and renewal under different sultans. A long period of stability returned under Sidi Mohammed ibn Abdallah (). Regional stability was disrupted by the French conquest of Algeria

The French conquest of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Regency of Algiers, and the French consul (representative), consul escalated into a blockade, following which the Jul ...

in 1830 and thereafter Morocco faced serious challenges from European encroachment in the region.

Morocco remained independent under 'Alawi rule until 1912, when it was placed under the control of a French protectorate. The 'Alawi sultans continued to act as nominal monarchs under French colonial rule until Morocco regained independence in 1956, with the Alawi sultan Mohammed V as its sovereign. In 1957, Mohammed V formally adopted the title of "King" and Morocco is now officially known as the Kingdom of Morocco.

Name and etymology

Morocco, since the rule of theSaadi dynasty

The Saadi Sultanate (), also known as the Sharifian Sultanate (), was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of Northwest Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was led by the Saadi dynasty, an Arab Sharifism, Sharifian dynasty.

...

, was sometimes referred to as the Sharifian Sultanate as a reference to the ruling dynasty's claim to noble ancestry. This was rendered in French as (; ) according to the Treaty of Fes. This name was still in official usage until 1956 when Morocco regained its independence from colonial rule. It was also referred to as Sultanate of Morocco in English, including in the Anglo-Moroccan Treaty of 1856.

The Alawi dynasty

The Alawi dynasty () – also rendered in English as Alaouite, Alawid, or Alawite – is the current Moroccan royal family and reigning dynasty. They are an Arab Sharifian dynasty and claim descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad through his ...

claims descent from Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

via Hasan

Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

*Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scotti ...

, the son of Ali

Ali ibn Abi Talib (; ) was the fourth Rashidun caliph who ruled from until his assassination in 661, as well as the first Shia Imam. He was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Born to Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib an ...

. The name Alawi'' () stems either from the name of Ali, from which the dynasty ultimately traces its descent, or from the name of the dynasty's early founder Ali al-Sharif of the Tafilalt

Tafilalt or Tafilet (), historically Sijilmasa, is a region of Morocco, centered on its largest oasis.

Etymology

There are many speculations regarding the origin of the word "Tafilalt", however it is known that Tafilalt is a Berber word meaning ...

.

History

Origins

The ruling dynasty of the Sultanate, the Alawis (; sometimes rendered Filali Sharifs), rose from the settlement ofSijilmassa

Sijilmasa (; also transliterated Sijilmassa, Sidjilmasa, Sidjilmassa and Sigilmassa) was a medieval Moroccan city and trade entrepôt at the northern edge of the Sahara in Morocco. The ruins of the town extend for five miles along the River Ziz ...

in the eastern oasis of Tafilalt

Tafilalt or Tafilet (), historically Sijilmasa, is a region of Morocco, centered on its largest oasis.

Etymology

There are many speculations regarding the origin of the word "Tafilalt", however it is known that Tafilalt is a Berber word meaning ...

. Little is known of their history prior to the 17th century, but by this century they had become the main leaders of the Tafilalt.

The Alawis are believed to have been descendants of immigrants from Yanbu

Yanbu (), also known as Yambu or Yenbo, is a city in the Medina Province of western Saudi Arabia. It is approximately 300 kilometers northwest of Jeddah (at ). The population is 31,800 (2025 census). Many residents are foreign expatriates wo ...

in the Hejaz

Hejaz is a Historical region, historical region of the Arabian Peninsula that includes the majority of the western region of Saudi Arabia, covering the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif and Al Bahah, Al-B ...

who settled in North Africa during a drought that affected the region in the 13th century. The dynasty claims descent to the Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

through his grandson Hasan

Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

*Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scotti ...

, the son of Ali

Ali ibn Abi Talib (; ) was the fourth Rashidun caliph who ruled from until his assassination in 661, as well as the first Shia Imam. He was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Born to Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib an ...

and Muhammad's daughter Fatima

Fatima bint Muhammad (; 605/15–632 CE), commonly known as Fatima al-Zahra' (), was the daughter of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and his wife Khadija. Fatima's husband was Ali, the fourth of the Rashidun caliphs and the first Shia imam. ...

.

Their status as '' shurafa'' (descendants of the Prophet) was part of the reason for their success, as in this era many communities in Morocco increasingly saw sharifian status and noble lineage as the best claim to political legitimacy. The Saadian dynasty

The Saadi Sultanate (), also known as the Sharifian Sultanate (), was a state which ruled present-day Morocco and parts of Northwest Africa in the 16th and 17th centuries. It was led by the Saadi dynasty, an Arab Sharifism, Sharifian dynasty.

...

, which ruled Morocco during the 16th century and preceded the 'Alawis, also claimed sharifian lineage and played an important role in engraining this model of political-religious legitimacy in Moroccan society.

The patriarch of the dynasty is believed to be Moulay Hassan ben al-Qasim ad-Dakhil, who established a religious aristocracy with his sharifian lineage throughout the oasis. Known for his deep piety, he was believed to have moved to Sijilmassa in 1265 under the rule of the Marinids at the request of locals who promoted him as imam of Tafilalt and viewed the presence of sharifs in the region as beneficial for religious legitimity.

He left behind a son, Mohamed, who in turn had only one descendant who bore the same name as his grandfather. One of this descendant's sons, , undertook the pilgrimage to Mecca

Hajj (; ; also spelled Hadj, Haj or Haji) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for capable Muslims that must be carried out at least once in their lifetim ...

and participated in the Moroccan–Portuguese wars of the 16th century and was also invited by the Nasrids to fight against Castile in the Iberian Peninsula

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, comprisin ...

during the Granada War

The Granada War was a series of military campaigns between 1482 and 1492 during the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, against the Nasrid dynasty's Emirate of Granada. It ended with the defeat o ...

. He declined to settle in Granada

Granada ( ; ) is the capital city of the province of Granada, in the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia, Spain. Granada is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada (Spain), Sierra Nevada mountains, at the confluence ...

at the request of scholars in the city but rather settled for many years in Fez and Sefrou

Sefrou () is a city in central Morocco situated in the Fès-Meknès region. It recorded a population of 79,887 in the 2014 Moroccan census, up from 63,872 in the 2004 census.

Sefrou is known for its historical Jewish population, and its annual che ...

before returning to Tafilalt.

Rise to power

The family's rise to power took place in the context of early-to-mid-17th century Morocco, when the power of the Saadian sultans ofMarrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

was in serious decline and multiple regional factions fought for control of the country. Among the most powerful of these factions were the Dala'iyya (also spelled Dila'iyya or Dilaites), a federation of Amazigh (Berbers) in the Middle Atlas

The Middle Atlas (Amazigh: ⴰⵟⵍⴰⵚ ⴰⵏⴰⵎⵎⴰⵙ, ''Atlas Anammas'', Arabic: الأطلس المتوسط, ''al-Aṭlas al-Mutawassiṭ'') is a mountain range in Morocco. It is part of the Atlas mountain range, a mountainous regio ...

who increasingly dominated central Morocco at this time, reaching the peak of their power in the 1640s. Another, was 'Ali Abu Hassun al-Semlali (or Abu Hassun), who had become leader of the Sous valley since 1614. When Abu Hassun extended his control to the Tafilalt

Tafilalt or Tafilet (), historically Sijilmasa, is a region of Morocco, centered on its largest oasis.

Etymology

There are many speculations regarding the origin of the word "Tafilalt", however it is known that Tafilalt is a Berber word meaning ...

region in 1631, the Dala'iyya in turn sent forces to enforce their own influence in the area. The local inhabitants chose as their leader the head of the 'Alawi family, Muhammad al-Sharif – known as Mawlay Ali al-Sharif, Mawlay al-Sharif, or Muhammad I – recognizing him as Sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

. Mawlay al-Sharif led an attack against Abu Hassun's garrison at Tabu'samt in 1635 or 1636 (1045 AH) but failed to expel them. Abu Hassun forced him to go into exile to the Sous valley, but also treated him well; among other things, Abu Hassun gifted him a slave concubine who later gave birth to one of his sons, Mawlay Isma'il.

While their father remained in exile, al-Sharif's sons took up the struggle. His son Sidi Mohammed

Sidi Mohammed was the Garad (chief) of the Hadiya Sultanate in the beginning of the seventeenth century. He is considered a descendant of some of the Silt'e clan originators as well as the founder of Halaba ethnic group.

Political career

Ga ...

(or Muhammad II), became the leader after 1635 and successfully led another rebellion which expelled Abu Hassun's forces in 1640 or 1641 (1050 AH). With this success, he was proclaimed sultan in place of his father who relinquished the throne to him. However, the Dala'iyya invaded the region again in 1646 and following their victory at Al Qa'a forced him to acknowledge their control over all the territory west and south of Sijilmasa. Unable to oppose them, Sidi Mohammed instead decided to expand in the opposite direction, to the northeast. He advanced as far as al-Aghwat and Tlemcen

Tlemcen (; ) is the second-largest city in northwestern Algeria after Oran and is the capital of Tlemcen Province. The city has developed leather, carpet, and textile industries, which it exports through the port of Rachgoun. It had a population of ...

in Algeria in 1650. His forays into Algeria provoked a response from the leaders of the Ottoman Regency of Algiers, who sent an army that chased him back to Sijilmasa. In negotiations with a legation from Algiers, Sidi Mohammed agreed not to cross into Ottoman territory again and the Tafna River was set as their northern border. In 1645 and again in 1652, Sidi Mohammed also imposed his rule on Tuat

Tuat, or Touat (), is a natural region of desert in central Algeria that contains a string of small oasis, oases. In the past, the oases were important for Camel caravan, caravans crossing the Sahara.

Geography

Tuat lies to the south of the Gr ...

, an oasis in the Sahara to the southeast.

Despite some territorial setbacks, the 'Alawis' influence slowly grew, partly thanks to their continued alliance with certain Arab tribes of the region. In June 1650, the leaders of Fez (or more specifically Fes el-Bali, the old city), with the support of the local Arab tribes, rejected the authority of the Dala'iyya and invited Sidi Mohammed to join them. Soon after he arrived, however, the Dala'iyya army approached the city and the local leaders, realizing they did not have enough strength to oppose them, stopped their uprising and asked Sidi Mohammed to leave.

Al-Sharif died in 1659, and Sidi Mohammed was once again proclaimed sovereign. However, this provoked a succession clash between Sidi Mohammed and one of his younger half-brothers, al-Rashid. Details of this conflict are lengthy, but ultimately Al-Rashid appears to have fled Sijilmasa in fear of his brother and took refuge with the Dala'iyya in the Middle Atlas. He then moved around northern Morocco, spending time in Fez, before settling in Angad (northeastern Morocco today). He managed to secure an alliance with the same Banu Ma'qil

The Banu Ma'qil () is an Arab nomadic tribe that originated in South Arabia. The tribe emigrated to the Maghreb region of North Africa with the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym tribes in the 11th century. They mainly settled in and around the Saharan w ...

Arab tribes who had previously supported his brother and also with the Ait Yaznasin (Beni Snassen), a Zenata

The Zenata (; ) are a group of Berber tribes, historically one of the largest Berber confederations along with the Sanhaja and Masmuda. Their lifestyle was either nomadic or semi-nomadic.

Society

The 14th-century historiographer Ibn Khaldun repo ...

Amazigh tribe. These groups recognized him as sultan in 1664, while around the same time Sidi Mohammed made a new base for himself as far west as Azrou

Azrou () is a Morocco, Moroccan town 89 kilometres south of Fes, Fez in Ifrane Province of the Fès-Meknès regions of Morocco, region.

Etymology

''Azrou'' is a geomorphological name taken from the landform of a large rock outcrop (Aẓro, ⴰⵥ ...

. The power of the Dala'iyya was in decline, and both brothers sought to take advantage of this, but both stood in each other's way. When Sidi Mohammed attacked Angad to force his rebellious brother's submission on August 2, 1664, he was instead unexpectedly killed and his armies defeated.

By this time, the Dala'iyya's realm, which once extended over Fez and most of central Morocco, had largely receded to their original home in the Middle Atlas. Al-Rashid was left in control of the 'Alawi forces and in less than a decade he managed to extend 'Alawi control over almost all of Morocco, reuniting the country under a new sharifian dynasty. Early on, he won over more rural Arab tribes to his side and integrated them into his military system. Also known as ''

By this time, the Dala'iyya's realm, which once extended over Fez and most of central Morocco, had largely receded to their original home in the Middle Atlas. Al-Rashid was left in control of the 'Alawi forces and in less than a decade he managed to extend 'Alawi control over almost all of Morocco, reuniting the country under a new sharifian dynasty. Early on, he won over more rural Arab tribes to his side and integrated them into his military system. Also known as ''guich

''Guich'' tribes, ''Gish'' tribes, or ''Jaysh'' tribes ( or ), or sometimes ''Makhzen'' tribes, were tribes of usually Arab origin organized by the sultans of Moroccan dynasties under the pre-colonial Makhzen regime to serve as troops and milita ...

'' tribes ("Army" tribes, also transliterated as ''gish''), they became one of his most important means of imposing control over regions and cities. In 1664 he had taken control of Taza

Taza () is a city in northern Morocco occupying the corridor between the Rif mountains and Middle Atlas mountains, about 120 km east of Fez and 150 km south of Al Hoceima. It recorded a population of 148,406 in the 2019 Moroccan ...

, but Fez rejected his authority and a siege of the city in 1665 failed. After further campaigning in the Rif

The Rif (, ), also called Rif Mountains, is a geographic region in northern Morocco. It is bordered on the north by the Mediterranean Sea and Spain and on the west by the Atlantic Ocean, and is the homeland of the Rifians and the Jebala people ...

region, where he won more support, Al-Rashid returned and secured the city's surrender in June 1666. He made the city his capital, but settled his military tribes in other lands and in a new kasbah

A kasbah (, also ; , , Maghrebi Arabic: ), also spelled qasbah, qasba, qasaba, or casbah, is a fortress, most commonly the citadel or fortified quarter of a city. It is also equivalent to the term in Spanish (), which is derived from the same ...

outside the city (Kasbah Cherarda

Kasbah Cherarda () is a kasbah in the city of Fez, Morocco, located on the northern outskirts of Fes Jdid, Fes el-Jdid. It was initially referred to as Kasbah el-Khemis () as there was an open market held every Thursday outside the wall.

today) to head off complaints from the city's inhabitants about their behaviour. He then defeated the remnants of the Dala'iyya by invading and destroying their capital in the Middle Atlas

The Middle Atlas (Amazigh: ⴰⵟⵍⴰⵚ ⴰⵏⴰⵎⵎⴰⵙ, ''Atlas Anammas'', Arabic: الأطلس المتوسط, ''al-Aṭlas al-Mutawassiṭ'') is a mountain range in Morocco. It is part of the Atlas mountain range, a mountainous regio ...

in June 1668. In July he captured Marrakesh from Abu Bakr ben Abdul Karim Al-Shabani, the son of the usurper who had ruled the city since assassinating his nephew Ahmad al-Abbas

Ahmad al-Abbas () (? – 1659) was the last Sultan of the Saadi Sultanate, Saadi dynasty of Saadi Sultanate, Morocco. He was proclaimed Sultan in Marrakesh in the year Islamic calendar, H.1064 (Common Era, CE November 22, 1653 - November 11, 1654 ...

, the last Saadian sultan. Al-Rashid's forces took the Sous valley and the Anti-Atlas

The Anti-Atlas, also known as Lesser Atlas or Little Atlas, is a mountain range in Morocco, a part of the Atlas Mountains in the northwest of Africa. The Anti-Atlas extends from the Atlantic Ocean in the southwest toward the northeast, to the heig ...

in the south, forced Salé

Salé (, ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the right bank of the Bou Regreg river, opposite the national capital Rabat, for which it serves as a commuter town. Along with some smaller nearby towns, Rabat and Salé form together a single m ...

and its pirate republic to acknowledge his authority, while in the north, except for the European enclaves, he was in control of all the Rif comprising Ksar al-Kebir, Tetouan and Oujda in the northeast. Al-Rashid had thus succeeded in reuniting the country under one rule. He was not able to enjoy this success for very long, however, and died young in 1672 while in Marrakesh.

The reign of Mawlay Isma'il

Upon Al-Rashid's death his younger half-brother Mawlay Isma'il became sultan. As sultan, Isma'il's 55-year reign was one of longest in Moroccan history. He distinguished himself as a ruler who wished to establish a unified Moroccan state as the absolute authority in the land, independent of any particular group within Morocco – in contrast to previous dynasties which relied on certain tribes or regions as the base of their power. He succeeded in part by creating a new army composed ofBlack

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

slaves (the '' Abid al-Bukhari'') from Sub-Saharan Africa

Sub-Saharan Africa is the area and regions of the continent of Africa that lie south of the Sahara. These include Central Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, and West Africa. Geopolitically, in addition to the list of sovereign states and ...

(or descendants of previously imported slaves), many of them Muslims, whose loyalty was to him alone. Mawlay Isma'il himself was half Black, his mother having been a Black slave concubine of Muhammad al-Sharif. This standing army also made effective use of modern artillery. He continuously led military campaigns against rebels, rivals, and European positions along the Moroccan coast. In practice, he still had to rely on various groups to control outlying areas, but he nonetheless succeeded in retaking many coastal cities occupied by England and Spain and managed to enforce direct order and heavy taxation throughout his territories. He put a definitive end to Ottoman attempts to gain influence in Morocco and established Morocco on more equal diplomatic footing with European powers in part by forcing them to ransom Christian captives at his court. These Christians were mostly captured by Moroccan pirate fleets which he heavily sponsored as a means of both revenue and warfare. While in captivity, prisoners were often forced into labour on his construction projects. All of these activities and policies gave him a reputation for ruthlessness and cruelty among European writers and a mixed reputation among Moroccan historians as well, though he is credited with unifying Morocco under strong (but brutal) leadership.

He also moved the capital from Fez to

He also moved the capital from Fez to Meknes

Meknes (, ) is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco, located in northern central Morocco and the sixth largest city by population in the kingdom. Founded in the 11th century by the Almoravid dynasty, Almoravids as a military settlement, Mekne ...

, where he built a vast imperial kasbah, a fortified palace-city whose construction continued throughout his reign. He also built fortifications across the country, especially along its eastern frontier, which many of his ''Abid'' troops garrisoned. This was partly a response to continued Turkish interference in Morocco, which Isma'il managed to stop after many difficulties and rebellions. Al-Khadr Ghaylan, a former leader in northern Morocco who fled to Algiers during Al-Rashid's advance, returned to Tetouan at the beginning of Isma'il's reign with Algerian help and led a rebellion in the north which was joined by the people of Fez. He recognized Isma'il's nephew, Ahmad ibn Mahriz, as sultan, who in turn had managed to take control of Marrakesh and was recognized also by the tribes of the Sous valley. Ghaylan was defeated and killed in 1673, and a month later Fez was brought back under control. Ahmad ibn Mahriz was only defeated and killed in 1686 near Taroudant

Taroudant (, ) is a city in the Sous in southwestern Morocco. It is situated east of Agadir on the road to Ouarzazate and south of Marrakesh. Today, it is a small market town and a tourist destination.

History

The Almoravids occupied the town ...

. Meanwhile, the Ottomans supported further dissidents via Ahmad al-Dala'i, the grandson of Muhammad al-Hajj who had led the Dala'iyya to dominion over a large part of Morocco earlier that century, prior to Al-Rashid's rise. The Dala'is had been expelled to Tlemcen but and they returned to the Middle Atlas at the instigation of Algiers and under Ahmad's leadership in 1677. They managed to defeat Isma'il's forces and control Tadla for a time, but were defeated in April 1678 near Wadi al-'Abid. Ahmad al-Dala'i escaped and eventually died in early 1680. After the defeat of the Dala'is and of his nephew, Isma'il was finally able to impose his rule without serious challenge over all of Morocco and was able to push back against Ottoman influence. After Ghaylan's defeat, he sent raids and military expeditions into Algeria in 1679, 1682, and 1695–96. A final expedition in 1701 ended poorly. Peace was re-established and the two sides agreed to recognize their pre-existing mutual border.

Isma'il also sought to project renewed Moroccan power abroad and in former territories. Following the decline of central rule in the late Saadian period earlier that century, the Pashalik of Timbuktu

The Pashalik of Timbuktu, also known as the Pashalik of Sudan, was a West African political entity that existed between the 16th and the 19th century. It was formed after the Battle of Tondibi, when a military expedition sent by Saadian sultan ...

, created after Ahmad al-Mansur

Ahmad al-Mansur (; 1549 – 25 August 1603), also known by the nickname al-Dhahabī () was the Saadi Sultanate, Saadi Sultan of Morocco from 1578 to his death in 1603, the sixth and most famous of all rulers of the Saadis. Ahmad al-Mansur was an ...

's invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

of the Songhai Empire

The Songhai Empire was a state located in the western part of the Sahel during the 15th and 16th centuries. At its peak, it was one of the largest African empires in history. The state is known by its historiographical name, derived from its lar ...

, had become de facto independent and the trans-Saharan trade routes fell into decline. The 'Alawis had become masters over Tuat in 1645, which rebelled many times after this but Isma'il established direct control there from 1676 onwards. In 1678–79 he organized a major military expedition to the south, forcing the Emirates of Trarza and Brakna to become his vassals and extending his overlordship up to the Senegal River

The Senegal River ( or "Senegal" - compound of the Serer term "Seen" or "Sene" or "Sen" (from Roog Seen, Supreme Deity in Serer religion) and "O Gal" (meaning "body of water")); , , , ) is a river in West Africa; much of its length mark ...

. In 1694 he appointed a ''qadi

A qadi (; ) is the magistrate or judge of a Sharia court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.

History

The term '' was in use from ...

'' to control in Taghaza

Taghaza () or Teghaza is an abandoned salt-mining centre located in a salt pan in the desert region of northern Mali. It was an important source of rock salt for West Africa up to the end of the 16th century when it was abandoned and replaced by ...

(present-day northern Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

) on behalf of Morocco. Later, in 1724, he sent an army to support the amir of Trarza (present-day Mauritania

Mauritania, officially the Islamic Republic of Mauritania, is a sovereign country in Maghreb, Northwest Africa. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Western Sahara to Mauritania–Western Sahara border, the north and northwest, ...

) against the French presence in Senegal

Senegal, officially the Republic of Senegal, is the westernmost country in West Africa, situated on the Atlantic Ocean coastline. It borders Mauritania to Mauritania–Senegal border, the north, Mali to Mali–Senegal border, the east, Guinea t ...

and also used the opportunity to appoint his own governor in Shinqit (Chinguetti). Despite this reassertion of control, trans-Saharan trade did not resume in the long-term on the same levels it existed before the 17th century.

In 1662 Portuguese-controlled Tangier

Tangier ( ; , , ) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. The city is the capital city, capital of the Tanger-Tetouan-Al Hoceima region, as well as the Tangier-Assilah Prefecture of Moroc ...

was transferred to English control as part of Catherine of Braganza

Catherine of Braganza (; 25 November 1638 – 31 December 1705) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland during her marriage to Charles II of England, King Charles II, which la ...

's dowry to Charles II of England

Charles II (29 May 1630 – 6 February 1685) was King of Scotland from 1649 until 1651 and King of England, Scotland, and King of Ireland, Ireland from the 1660 Restoration of the monarchy until his death in 1685.

Charles II was the eldest su ...

. Mawlay Isma'il unsuccessfully besieged the city in 1680, but this pressure, along with attacks from local Muslim '' mujahidin'' (also known as the " Army of the Rif"), led the English to evacuate Tangier in 1684. Mawlay Isma'il immediately claimed the city and sponsored its Muslim resettlement, but granted local authority to 'Ali ar-Rifi, the governor of Tetouan who had played an active part in besieging the city and became the chieftain of northern Morocco around this time. Isma'il also conquered Spanish-controlled Mahdiya in 1681, Al-Ara'ish (Larache) in 1689, and Asilah

Asilah () is a fortified town on the northwest tip of the Atlantic coast of Morocco, about south of Tangier. Its ramparts and gateworks remain fully intact.

History

The town's history dates back to 1500 B.C., when Phoenicians occupied a site ...

in 1691. Moreover, he sponsored Moroccan pirates which preyed on European merchant ships. Despite this, he also allowed Europeans merchants to trade inside Morocco, but he strictly regulated their activities and forced them to negotiate with his government for permission, allowing him to efficiently collect taxes on trade. Isma'il also allowed European countries, often through the proxy of Spanish Franciscan

The Franciscans are a group of related organizations in the Catholic Church, founded or inspired by the Italian saint Francis of Assisi. They include three independent Religious institute, religious orders for men (the Order of Friars Minor bei ...

friars, to negotiate ransoms for the release of Christians captured by pirates or in battle. He also pursued relations with Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

of France starting in 1682, hoping to secure an alliance against Spain, but France was less interested in this idea and relations eventually collapsed after 1718.

Disorder and civil war under Isma'il's sons

After Mawlay Isma'il's death, Morocco was plunged into one of its greatest periods of turmoil between 1727 and 1757, with Isma'il's sons fighting for control of the sultanate and never holding onto power for long. Isma'il had left hundreds of sons who were theoretically eligible for the throne. Conflict between his sons was compounded by rebellions against the heavily taxing and autocratic government which Isma'il had previously imposed. Furthermore, the ''Abid'' of Isma'il's reign came to wield enormous power and were able to install or depose sultans according to their interests throughout this period, though they also had to compete with the ''guich'' tribes and some of the Amazigh (Berber) tribes. Meknes remained the capital and the scene of most of these political changes, but Fez was also a key player. Ahmad adh-Dhahabi was the first to succeed his father but was immediately contested and ruled twice only briefly before his death in 1729, with his brotherAbd al-Malik

Abdul Malik () is an Arabic (Muslim or Christian) male given name and, in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' Abd'', ''al-'' and ''Malik''. The name means "servant of the King", in the Christian instance 'King' meaning 'King ...

ruling in between his reigns in 1728. After this his brother Abdallah ruled for most of the period between 1729 and 1757 but was deposed four times. Abdallah was initially supported by the ''Abid'' but eventually made enemies of them after 1733. Eventually he was able to gain advantage over them by forming an alliance with the Amazigh tribe of Ait Idrasin, the Oudaya

The Oudaya () also written as Udaya, Oudaia and sometimes referred to as Wadaya () is an Arabs, Arab tribe in Morocco of Maqil origin. They are situated around Fez, Morocco, Fez and Meknes, Marrakesh and in Rabat. They were recruited by Ismail Ibn ...

''guich'' tribe, and the leaders of Fez (whom he alienated early on but later reconciled with). This alliance steadily wore down the ''Abid''s power and paved the way for their submission in the later part of the 18th century.

In this period, the north of Morocco also became virtually independent of the central government, being ruled instead by Ahmad ibn 'Ali ar-Rifi, the son of 'Ali al-Hamami ar-Rifi whom Mawlay Isma'il had granted local authority in the region of Tangier. Ahmad al-Hamami ar-Rifi used Tangier as the capital of his territory and profited from an arms trade with the British at Gibraltar, with whom he also established diplomatic relations. Sultan Ahmad al-Dahabi had tried to appoint his own governor in Tetouan to undermine Ar-Rifi's power in 1727, but without success. Ahmad ar-Rifi was initially uninterested in the politics playing out in Meknes, but became embroiled due to an alliance he formed with al-Mustadi', one of the ephemeral sultans installed by the 'Abid installed in May 1738. When Al-Mustadi' was in turn deposed in January 1740 to accommodate Abdallah's return to power, Ar-Rifi opposed the latter and invaded Fez in 1741. Mawlay Abdallah's alliance of factions was able to finally defeat and kill him on the battlefield in 1743, and soon after the sultan's authority was re-established along the coastal cities of Morocco. In 1647, Abdallah strategically established his two sons as ''Khalifa'' (Viceroy

A viceroy () is an official who reigns over a polity in the name of and as the representative of the monarch of the territory.

The term derives from the Latin prefix ''vice-'', meaning "in the place of" and the Anglo-Norman ''roy'' (Old Frenc ...

) in politically important cities. His eldest Mawlay Ahmed was appointed ''Khalifa'' of Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ) is the Capital (political), capital city of Morocco and the List of cities in Morocco, country's seventh-largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan population of over 1.2 million. ...

and his youngest. Sidi Mohammed, ''Khalifa'' of Marrakesh. His eldest son would die before him in 1750. After 9 years of uninterrupted reign, Abdallah died at Dar Dbibegh on November 10, 1757.

Restoration of authority under Mohammed ibn Abdallah

Order and control was firmly re-established only under Abdallah's son, Sidi Mohammed ibn Abdallah (Mohammed III), who became sultan in 1757 after a decade as viceroy in Marrakesh. Many of the 'Abid had by then deserted their contingents and joined the common population of the country, and Sidi Mohammed III was able to reorganize those who remained into his own elite military corps. The Oudaya, who had supported his father but had been a burden on the population of Fez where they lived, became the main challenge to the new sultan's power. In 1760 he was forced to march with an army to Fez where he arrested their leaders and destroyed their contingents, killing many of their soldiers. In the aftermath the sultan created a new, much smaller, Oudaya regiment which was given new commanders and garrisoned in Meknes instead. Later, in 1775, he tried to distance the ''Abid'' from power by ordering their transfer from Meknes to Tangier in the north. The ''Abid'' resisted him and attempted to proclaim his son Yazid (the later Mawlay Yazid) as sultan, but the latter soon changed his mind and was reconciled with his father. After this, Sidi Mohammed III dispersed the ''Abid'' contingents to garrisons in Tangier, Larache, Rabat, Marrakesh and the Sous, where they continued to cause trouble until 1782. These disturbances were compounded by drought and severe famine between 1776 and 1782 and an outbreak of plague in 1779–1780, which killed many Moroccans and forced the sultan to import wheat, reduce taxes, and distribute food and funds to locals and tribal leaders in order to alleviate the suffering. By now, however, the improved authority of the sultan allowed the central government to weather these difficulties and crises. Sidi Mohammed ibn Abdallah maintained the peace in part through a relatively more decentralized regime and lighter taxes, relying instead on greater trade with Europe to make up the revenues. In line with this policy, in 1764 he foundedEssaouira

Essaouira ( ; ), known until the 1960s as Mogador (, or ), is a port city in the western Moroccan region of Marrakesh-Safi, on the Atlantic coast. It has 77,966 inhabitants as of 2014.

The foundation of the city of Essaouira was the work of t ...

, a new port city through which he funneled European trade with Marrakesh. The last Portuguese outpost on the Moroccan coast, Mazagan (El Jadida

El Jadida (, ) is a major port city on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, located south of the city of Casablanca, in the province of El Jadida and the region of Casablanca-Settat. It has a population of 170,956 as of 2023.

The fortified city, b ...

today), was taken by Morocco in 1729, leaving only the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta

Ceuta (, , ; ) is an Autonomous communities of Spain#Autonomous cities, autonomous city of Spain on the North African coast. Bordered by Morocco, it lies along the boundary between the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean. Ceuta is one of th ...

and Melilla

Melilla (, ; ) is an autonomous city of Spain on the North African coast. It lies on the eastern side of the Cape Three Forks, bordering Morocco and facing the Mediterranean Sea. It has an area of . It was part of the Province of Málaga un ...

as the remaining European outposts in Morocco. Muhammad also signed a Treaty of Friendship with the United States in 1787 after becoming the first head of state to recognize the new country. He was interested in scholarly pursuits and also cultivated a productive relationship with the ''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

'', or Muslim religious scholars, who supported some of his initiatives and reforms.

Sidi Mohammed's opening of Morocco to international trade was not welcomed by some, however. After his death in 1790, his son and successor Mawlay Yazid ruled with more xenophobia and violence, punished Jewish communities, and launched an ill-fated attack against Spanish-held Ceuta in 1792 in which he was mortally wounded. After his death, he was succeeded by his brother Suleyman (or Mawlay Slimane), though the latter had to defeat two more brothers who contested the throne: Maslama in the north and Hisham in Marrakesh to the south. Suleyman brought trade with Europe nearly to a halt. Although less violent and bigoted than Yazid, he was still portrayed by European sources as xenophobic. Some of this lack of engagement with Europe was likely a consequence of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (sometimes called the Great French War or the Wars of the Revolution and the Empire) were a series of conflicts between the French and several European monarchies between 1792 and 1815. They encompas ...

, during which the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

blockaded France and Spain, both of whom threatened Morocco into not taking sides in the conflict. After 1811, Suleyman also pushed a fundamentalist Wahhabist ideology at home and attempted to suppress local Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

orders and brotherhoods, in spite of their popularity and despite his own membership in the Tijaniyya order.

European encroachment and reforms

Suleyman's successor,Abd al-Rahman

Abdelrahman or Abd al-Rahman or Abdul Rahman or Abdurrahman or Abdrrahman ( or occasionally ; DMG ''ʿAbd ar-Raḥman'') is a male Arabic Muslim given name, and in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' Abd'', ''al-'' and '' ...

(), tried to reinforce national unity by recruiting local elites of the country and orchestrating military campaigns designed to bolster his image as a defender of Islam against encroaching European powers. The French conquest of Algeria

The French conquest of Algeria (; ) took place between 1830 and 1903. In 1827, an argument between Hussein Dey, the ruler of the Regency of Algiers, and the French consul (representative), consul escalated into a blockade, following which the Jul ...

in 1830, however, destabilized the region and put the sultan in a very difficult position. It marked a major shift in Morocco's diplomatic and military situation. Until then, European powers had been an intermittent concern, but now they became a permanent presence whose influence grew in politics, the economy, and society. French conquests in the region progressively surrounded Morocco afterwards, while colonial encroachment on Morocco itself was slowed mainly due to rivalries between the European powers.

Wide popular support for the Algerians against the French invasion led Morocco to allow the flow of aid and arms to the resistance movement led by Emir Abd al-Qadir, while the Moroccan ''ulama'' delivered a fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

for supporting jihad in 1837. On the other hand, Abd al-Rahman was reluctant to provide the French with a clear reason to attack Morocco if he ever intervened. He managed to maintain the appearance of neutrality until 1844, when he was compelled to provide refuge to Abd al-Qadir in Morocco. The French, led by the marshall Bugeaud, pursued him and thoroughly routed the Moroccan army at the Battle of Isly

The Battle of Isly () was fought on August 14, 1844, between France and Morocco, near the . French forces under Marshal Thomas Robert Bugeaud routed a much larger, but poorly organized, Moroccan force, mainly fighters from the tribes of , but a ...

, near Oujda, on August 14. At the same time, the French navy bombarded Tangiers on August 6 and bombarded Mogador (Essaouira) on August 16. In the aftermath, Morocco signed the Convention of Lalla Maghnia on March 18, 1845. The treaty made the superior power of France clear and forced the sultan to recognize French authority over Algeria. Abd al-Qadir turned rebel against the sultan and took refuge in the Rif region until his surrender to the French in 1848.

Between 1848 and 1865, Britain, France and Spain competed for influence in Morocco. Britain sought to keep France at bay in the region, especially since Morocco was next to Gibraltar. British consul John Hay Drummond Hay pressured Abd ar-Rahman into signing the Anglo-Moroccan Treaty of 1856, which removed government restrictions on trade and granted special privileges to the British. Among the latter was the establishment of a ''protégé'' system whereby Britain could extend legal protection to individuals within Morocco. British influence in Morocco encouraged other European powers to replicate their success. The Spanish government was eager to expand its presence in Africa in order to distract from its own domestic difficulties. The next direct confrontation between Morocco and Europe was the Hispano-Moroccan War, which took place from 1859 to 1860. The subsequent Treaty of Wad Ras

The Treaty of Wad Ras (, ) was a treaty signed between Morocco and Spain at the conclusion of the Hispano-Moroccan War (1859–60), War of Tetuan on April 26, 1860, at Wad Ras, located between Tétouan, Tetuan and Tangier. The conditions of the ...

led the Moroccan government to take a massive British loan larger than its national reserves to pay off its war debt

War reparations are compensation payments made after a war by one side to the other. They are intended to cover Collateral damage, damage or injury inflicted during a war. War reparations can take the form of hard currency, precious metals, natur ...

to Spain.

Right before the war, Abd al-Rahman died and was succeeded by his son Muhammad IV (). Following the war, the new sultan was determined to follow a policy of reforms to address the state's weaknesses. These reforms took place progressively and in a piecemeal fashion. The sultan tried to increase revenues by streamlining the taxation of Morocco's fertile regions, forcing the payment of an annual fixed sum instead of the more flexible taxation regime that existed earlier. This was more efficient but it took a heavy toll on the rural economy and the food security of its population. At the same time, the urban population grew along with international trade, which fostered the emergence of an urban bourgeoisie, both Muslim and Jewish, who spurred further social changes. Despite this growth, the state remained in financial difficulties, in part due to the devaluation of the Moroccan currency.

Muhammad IV also reorganized the state and began to institutionalize a more professional, regular administration and military, often by following Western European models. This trend was taken further by his talented successor, Hassan I (). Hassan I also campaigned tirelessly to collect tax revenues and reimpose central rule on outlying provinces.

In the latter part of the 19th century Morocco's instability resulted in European countries intervening to protect investments and to demand economic concessions. Hassan I called for the

Muhammad IV also reorganized the state and began to institutionalize a more professional, regular administration and military, often by following Western European models. This trend was taken further by his talented successor, Hassan I (). Hassan I also campaigned tirelessly to collect tax revenues and reimpose central rule on outlying provinces.

In the latter part of the 19th century Morocco's instability resulted in European countries intervening to protect investments and to demand economic concessions. Hassan I called for the Madrid Conference

The Madrid Conference of 1991 was a peace conference, held from 30 October to 1 November 1991 in Madrid, hosted by Spain and co-sponsored by the United States and the Soviet Union. It was an attempt by the international community to revive the ...

of 1880 in response to France and Spain's abuse of the ''protégé'' system, but the result was an increased European presence in Morocco—in the form of advisors, doctors, businessmen, adventurers, and even missionaries.

Crisis and installation of French and Spanish Protectorates

After Sultan Abdelaziz appointed his brother Abdelhafid as viceroy of Marrakesh, the latter sought to have him overthrown by fomenting distrust over Abdelaziz's European ties. Abdelhafid was aided by Madani el-Glaoui, older brother of T'hami, one of the Caids of the Atlas. He was assisted in the training of his troops byAndrew Belton

Andrew Belton (17 April 1882 – 1970) was a British Army officer and veteran of campaigns in South Africa and Morocco. He was an early exponent of the use of aircraft for military purposes, enrolling at the Chicago School of Aviation in Apr ...

, a British officer and veteran of the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

. For a brief period, Abdelaziz reigned from Rabat while Abdelhafid reigned in Marrakesh and Fez and a conflict known as the Hafidiya (1907–1908) ensued. In 1908 Abdelaziz was defeated in battle. In 1909, Abdelhafid became the recognized leader of Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

.

In 1911, rebellion broke out against the sultan. This led to the Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis, was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in July 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, ...

, also known as the Second Moroccan Crisis. These events led Abdelhafid to abdicate after signing the Treaty of Fes on 30 March 1912, which made Morocco a French protectorate. He signed his abdication only when on the quay in Rabat, with the ship that would take him to France already waiting. When news of the treaty finally leaked to the Moroccan populace, it was met with immediate and violent backlash in the Intifada of Fez. His brother Youssef was proclaimed Sultan by the French administration several months later (13 August 1912). At the same time a large part of northern Morocco was placed under Spanish control.

Government and politics

Moroccan authors during the Sultanate classified it as both being acaliphate

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

and an imamate

The term imamate or ''imamah'' (, ''imāmah'') means "leadership" and refers to the office of an ''imam'' or a Muslim theocratic state ruled by an ''imam''.

Theology

*Imamate in Shia doctrine, the doctrine of the leadership of the Muslim commu ...

. Morocco was led by an absolute monarchy, with no clear rules of succession.

Makhzen

The governing administration in Morocco, known as the Makhzen (), was an hierarchical administration which ruled underIslamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

. The authority of the Sultan in Morocco were both political and religious, with his authority revolving around his title of Commander of the Faithful

() or Commander of the Faithful is a Muslim title designating the supreme leader of an Islamic community.

Name

Although etymologically () is equivalent to English "commander", the wide variety of its historical and modern use allows for a ...

(''amir al-muminin'') and oaths of allegiance ( ''bayahs'') made by tribes to the Sultan.

The Sultanate was divided into provinces led by pasha

Pasha (; ; ) was a high rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignitary, dignitaries, and others. ''Pasha'' was also one of the highest titles in the 20th-century Kingdom of ...

s and regions led by caids, which were all appointed by the Makhzen and were described as "local despots" by .

These caids were unpaid until 1856, when Hay proposed that Sultan Mohammed IV give government workers wages from the Makhzen's treasury. A few caids consolidated power and embraced despotism, establishing a form of oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

involving three families: the El Glaoui (through Madani El Glaoui

Sidi, Si El Madani El Glaoui (1860–July 1918; born Madani El Mezouari El Glaoui, ; ), nicknamed the Faqīh, faqih (the literate) was a prominent Statesman (politician), statesman in Morocco during the late 19th century and early 20th century. H ...

), Gontafi and Mtouggi clans.

The extent of the Sultan's authority was classified in two categories mainly based on taxation. Bled el-Makhzen (), which included most of the country's Atlantic coast and urban area

An urban area is a human settlement with a high population density and an infrastructure of built environment. Urban areas originate through urbanization, and researchers categorize them as cities, towns, conurbations or suburbs. In urbani ...

s and was directly governed and taxed by the Makhzen under the direct rule of the Sultan. In contrast, Bled es-Siba () held tribal autonomy and self-governance but held an oath of allegiance to the Sultan and recognized his religious and spiritual status but refused to pay taxes to the Makhzen.

Despite this, the distinction between Bled el-Makhzen and Bled es-Siba remained vague and fluctuated. The decision by some tribes to refuse to pay taxes to the Makhzen were sometimes used as a bargaining chip to obtain favors rather than dissent from the Sultan. In many cases, governors in Bled es-Siba reported their investiture

Investiture (from the Latin preposition ''in'' and verb ''vestire'', "dress" from ''vestis'' "robe") is a formal installation or ceremony that a person undergoes, often related to membership in Christian religious institutes as well as Christian kn ...

to the Sultan.

Judiciary

In Bilad el-Makhzen,

In Bilad el-Makhzen, common law

Common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law primarily developed through judicial decisions rather than statutes. Although common law may incorporate certain statutes, it is largely based on prece ...

matters and some civil and criminal cases were judged by courtrooms which ruled by Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

and were presided by a ''qadi

A qadi (; ) is the magistrate or judge of a Sharia court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.

History

The term '' was in use from ...

'' (judge), where parties could choose an '' oukil'' (council; equivalent to a lawyer) to represent them in court and present ''fatwas'' (advisories) written by a '' faqih'' (jurist) using Islamic jurisprudence

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

to present their case or defense. After the sentence was pronounced, a governor for the Makhzen was charged with enforcing the decision. Contracts and marriage certificates were registered by two '' adouls'' (notaries) and were signed also signed by a ''qadi''.

Most Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

civil

Civil may refer to:

*Civility, orderly behavior and politeness

*Civic virtue, the cultivation of habits important for the success of a society

*Civil (journalism)

''The Colorado Sun'' is an online news outlet based in Denver, Colorado. It lau ...

and criminal cases were judged by a courtroom ran by the Makhzen and led by a pasha

Pasha (; ; ) was a high rank in the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignitary, dignitaries, and others. ''Pasha'' was also one of the highest titles in the 20th-century Kingdom of ...

(governor) or a qaid

Qaid ( ', "commander"; pl. ', or '), also spelled kaid or caïd, is a word meaning "commander" or "leader." It was a title in the Normans, Norman kingdom of Sicily, applied to palatine officials and members of the ''curia'', usually to thos ...

(commander) which enforced tazir

In Islamic Law, ''tazir'' (''ta'zeer'' or ''ta'zir'', ) lit. scolding; refers to punishment for offenses at the discretion of the judge (Qadi) or ruler of the state. The Makhzen courts were often favored over religious courts due to their

One of the main literary genres of Morocco during this period were works devoted to describing the history of local

One of the main literary genres of Morocco during this period were works devoted to describing the history of local

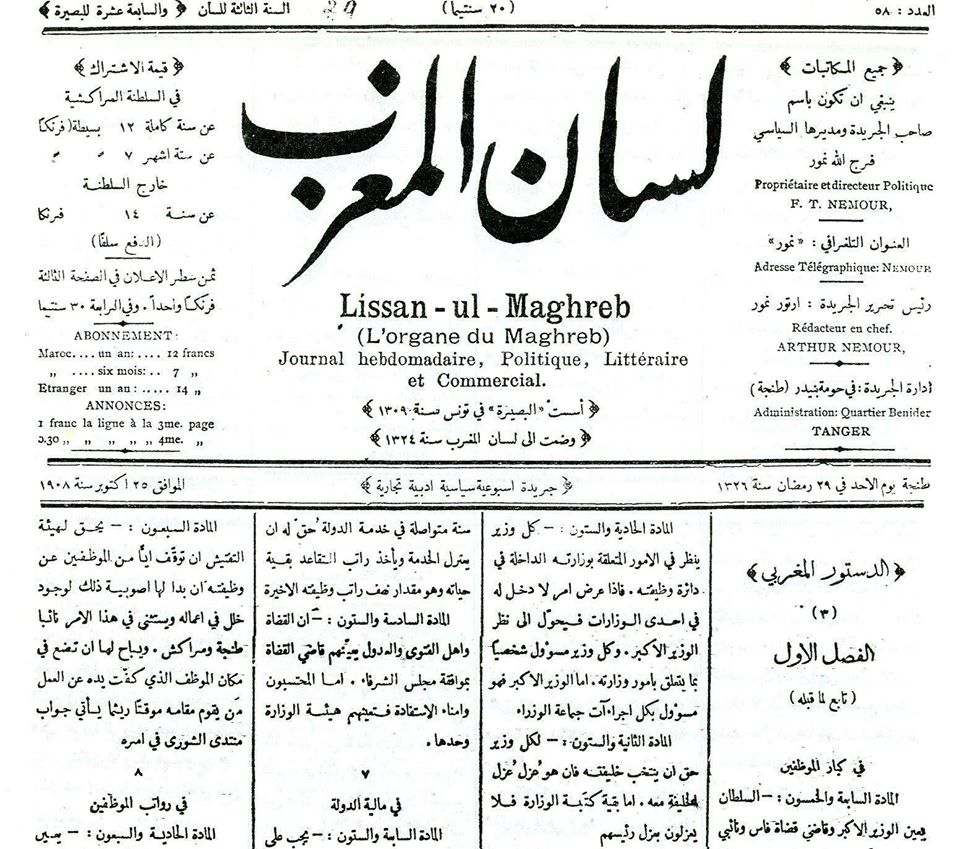

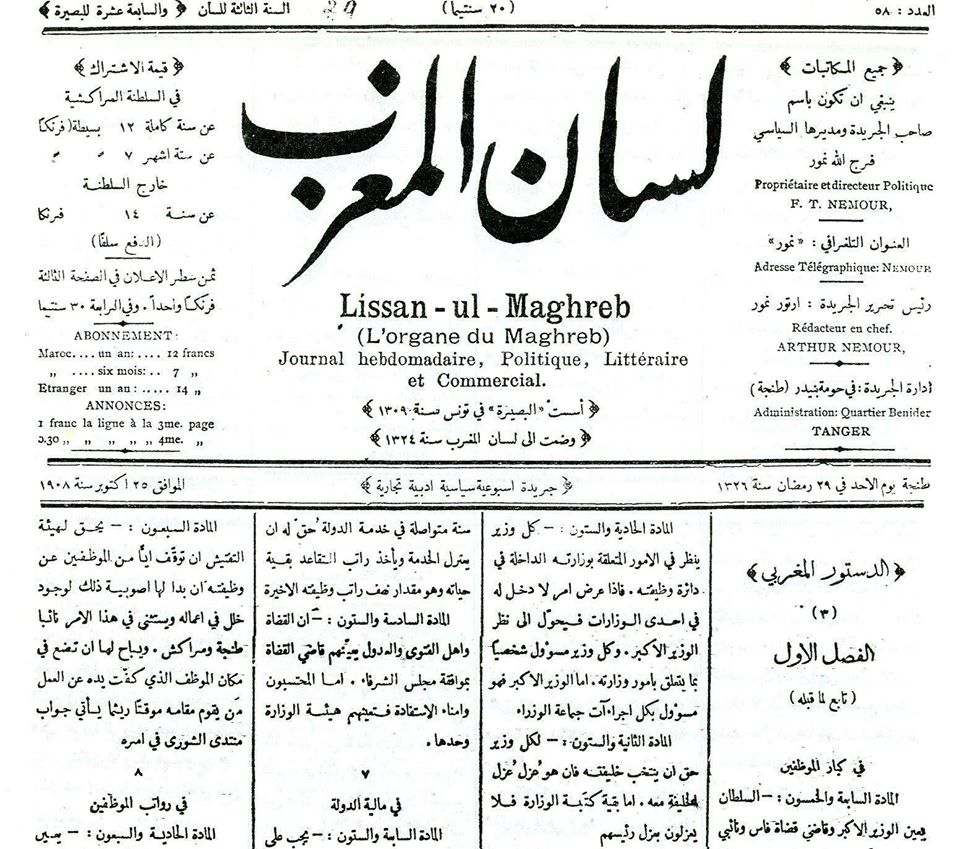

During modernization attempts for the Moroccan state under Moulay Abdelhafid to counter European influence, a draft constitution was published in the October 1908 issue of newspaper '' Lissan-ul-Maghreb'' in Tangier. The 93-article draft emphasized and codified the concepts of

During modernization attempts for the Moroccan state under Moulay Abdelhafid to counter European influence, a draft constitution was published in the October 1908 issue of newspaper '' Lissan-ul-Maghreb'' in Tangier. The 93-article draft emphasized and codified the concepts of

Moulay Isma'il () is notable for building a vast imperial palace complex in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today. During this era, valuable architectural elements from earlier buildings built by the Saadi dynasty, such as the huge Badi Palace in Marrakesh, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of Moulay Isma'il. Other Alawi sultans built or expanded the royal palaces in Fez, in Marrakesh, and in Rabat.

Moulay Isma'il () is notable for building a vast imperial palace complex in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today. During this era, valuable architectural elements from earlier buildings built by the Saadi dynasty, such as the huge Badi Palace in Marrakesh, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of Moulay Isma'il. Other Alawi sultans built or expanded the royal palaces in Fez, in Marrakesh, and in Rabat.

In 1684, during Moulay Isma'il's reign, Tangier was also returned to Moroccan control and much of the city's current Islamic architecture dates from his reign or after. In 1765, Mohammed ibn Abdallah started the construction of the new port city of

In 1684, during Moulay Isma'il's reign, Tangier was also returned to Moroccan control and much of the city's current Islamic architecture dates from his reign or after. In 1765, Mohammed ibn Abdallah started the construction of the new port city of

The first Moroccan bank in the

The first Moroccan bank in the

The Negative Impacts of Colonization on the Local Population: Evidence from Morocco

/ref> Despite economic setbacks occurring periodically, civil conflicts at both national and local levels and the primitive tools employed, there remained a significant emphasis on soil exploitation and agriculture constituted the primary occupation for the majority of rural inhabitants. Numerous lands became contested territories among various groups and tribes, which sometimes prompted the Makhzen to intervene in order to settle the disputes. Pierre Tralle, a French prisoner who also participated in the construction of

speedy trial

In criminal law, the right to a speedy trial is a human right under which it is asserted that a government prosecutor may not delay the trial of a criminal suspect arbitrarily and indefinitely. Otherwise, the power to impose such delays would ...

s. However, the jurisdiction of the quasi-secular Makhzen courts and the religious courts often overlapped and a party in a Makhzen dispute could request to raise the case to a religious court. The death sentence

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence ordering that an offender be punished in s ...

could only be ruled with the authorization of the Sultan.

Moroccan Jews were given judicial autonomy and were allowed to set up courtrooms which enforced Hebraic law and rabbinical jurisprudence among themselves. However, Islamic religious courts were favored to judge in cases involving both Jews and Muslims. Matters involving Europeans were judged by the consul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

of their home countries. If a Moroccan was subject to a lawsuit from a European, the consul would file the complaint to a Makhzen courthouse on behalf of the European complainant.

Within Bled es-Siba, a number of rural courtrooms were set up by tribes in Morocco which judged based on a mix of Berber

Berber or Berbers may refer to:

Ethnic group

* Berbers, an ethnic group native to Northern Africa

* Berber languages, a family of Afro-Asiatic languages

Places

* Berber, Sudan, a town on the Nile

People with the surname

* Ady Berber (1913–196 ...

customary law

A legal custom is the established pattern of behavior within a particular social setting. A claim can be carried out in defense of "what has always been done and accepted by law".

Customary law (also, consuetudinary or unofficial law) exists wher ...

and Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

. These included arbitrational "court of laws" in villages for civil disputes and tribal "court of appeals" in criminal or appellate case. In some cases, complainants were authorized to enforce legal rulings in their favor through means of violence.

Flag

The Alawis are said to have adopted a plain red flag in the 17th century. Such a red flag was still being used until 1915, when a green star was added to the current Moroccan flag. Different origins have been proposed for the red flag. Moroccan researcher Nabil Mouline has suggested that it was adopted when Sultan al-Rashid captured Rabat, which was inhabited at the time by Andalusians who used the red flag. Others have claimed that the red colour represents the Alawis' claim of sharifian descent, much like theSharifs of Mecca

The Sharif of Mecca () was the title of the leader of the Sharifate of Mecca, traditional steward of the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina. The term ''sharif'' is Arabic for "noble", "highborn", and is used to describe the descendants of ...

(who also claimed descent from the Islamic prophet Muhammad) used a red flag. Nabil Mouline suggests that the Alawis also used a green flag.

Religion

Islam in Morocco was primarily defined by Maliki doctrine intertwined withSufism

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

.

Inspired by Wahhabism

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to oth ...

, a crackdown on Sufi brotherhoods and mystical orders (tariqa

A ''tariqa'' () is a religious order of Sufism, or specifically a concept for the mystical teaching and spiritual practices of such an order with the aim of seeking , which translates as "ultimate truth".

A tariqa has a (guide) who plays the ...

s) in the country was led by Moulay Slimane for practices he deemed to be sinful. This crackdown stopped under the reign of Moulay Abderrahmane ben Hisham, which helped him consolidate his rule.

Culture

Literature

One of the main literary genres of Morocco during this period were works devoted to describing the history of local

One of the main literary genres of Morocco during this period were works devoted to describing the history of local Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

"saints

In Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Anglican, Oriental Orth ...

" and teachers, which were common since the 14th century. Such works from Fez, for example, are especially abundant from the 17th to 20th centuries.

During the 18th century, a number of Tachelhit

( ; from its name in Moroccan Arabic, ), now more commonly known as Tashelhiyt or Tachelhit ( ; from the endonym , ), is a Berber language spoken in southwestern Morocco. When referring to the language, anthropologists and historians prefer the ...

poets arose including Muhammad ibn Ali al-Hawzali in Taroudant and Sidi Hammou Taleb in Moulay Brahim. Ahmed at-Tijani (d. 1815), originally from Aïn Madhi

Aïn Madhi is a town and commune in Laghouat Province, Algeria, and the seat of Aïn Madhi District. According to the 1998 census it has a population of 6,263.

Aïn Madhi is the birthplace of Ahmad al-Tijani, founder of the Tijaniyyah Sufi orde ...

in Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

, lived in Fez and later established the Tijaniyyah

The Tijjani order () is a Sufi Tariqa, order of Sunni Islam named after Ahmad al-Tijani. It originated in Algeria but now more widespread in Maghreb, West Africa, particularly in Senegal, The Gambia, Gambia, Mauritania, Mali, Guinea, Niger, ...

Sufi order. He was associated with the North African literary elite and the religious scholars of the Tijaniyyah order were among the most prolific producers of literature in the Maghreb.

Towards the beginning of the 20th century, Moroccan literature began to diversify, with polemic or political works becoming more common at this time. For example, there were Muhammad Bin Abdul-Kabir Al-Kattani's anti-colonial periodical '' at-Tā'ūn'' (), and his uncle Muhammad ibn Jaqfar al-Kattani's popular ''Nasihat ahl al-Islam'' ('Advice to the People of Islam'), published in Fez in 1908, both of which called on Moroccans to unite against European encroachment.

Mass media

News media

The news media or news industry are forms of mass media that focus on delivering news to the general public. These include News agency, news agencies, newspapers, news magazines, News broadcasting, news channels etc.

History

Some of the fir ...

came to Morocco in 1860 through Spanish-language newspaper El Eco de Tetuan in Tetouan, which was founded shortly after the Treaty of Wad Ras

The Treaty of Wad Ras (, ) was a treaty signed between Morocco and Spain at the conclusion of the Hispano-Moroccan War (1859–60), War of Tetuan on April 26, 1860, at Wad Ras, located between Tétouan, Tetuan and Tangier. The conditions of the ...

. The Treaty of Madrid in 1880 allowed for the rise of two newspaper, '' al-Moghreb al-Aksa'', printed in Spanish by G.T. Abrines, and the ''Times of Morocco

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events, and a fundamental quantity of measuring systems.

Time or times may also refer to:

Temporal measurement

* Time in physics, defined by its measurement

* Time standard, civil time specificat ...

'', printed in English by Edward Meakin. Three years later, the French-language '' Le Réveil du Maroc'' was founded by Abraham Lévy-Cohen, a Moroccan Jewish businessman.

During modernization attempts for the Moroccan state under Moulay Abdelhafid to counter European influence, a draft constitution was published in the October 1908 issue of newspaper '' Lissan-ul-Maghreb'' in Tangier. The 93-article draft emphasized and codified the concepts of

During modernization attempts for the Moroccan state under Moulay Abdelhafid to counter European influence, a draft constitution was published in the October 1908 issue of newspaper '' Lissan-ul-Maghreb'' in Tangier. The 93-article draft emphasized and codified the concepts of separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

, good citizenship, and human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

for the first time in the country's history.

The draft, which was written by an anonymous author and was never signed by Moulay Abdelhafid, was inspired by the late 19th century constitutions of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, and Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq to the west, Turkey, Azerbaijan, and Armenia to the northwest, the Caspian Sea to the north, Turkmenistan to the nort ...

. In 2008, al-Massae claimed that the draft was written by members of a "Moroccan Association of Unity and Progress" composed of an elite close to Moulay Abdelhafid which supported the toppling of his predecessor, Abdelaziz.

Architecture

Starting with the Saadians and continuing with the Alawis, Moroccan art and architecture is often described by art historians as being relatively conservative; meaning that it continued to reproduce the earlier Hispano-Maghrebi architectural style with high fidelity but did not introduce major new innovations. Many of the mosques and palaces standing in Morocco today have been built or restored under the Alawi sultans at some point or another. Religious monuments that were built or rebuilt during this period include the Zawiya of Moulay Idris II in Fez, the Lalla Aouda Mosque in Meknes, and the current Ben Youssef Mosque in Marrakesh. Moulay Isma'il () is notable for building a vast imperial palace complex in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today. During this era, valuable architectural elements from earlier buildings built by the Saadi dynasty, such as the huge Badi Palace in Marrakesh, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of Moulay Isma'il. Other Alawi sultans built or expanded the royal palaces in Fez, in Marrakesh, and in Rabat.

Moulay Isma'il () is notable for building a vast imperial palace complex in Meknes, where the remains of his monumental structures can still be seen today. During this era, valuable architectural elements from earlier buildings built by the Saadi dynasty, such as the huge Badi Palace in Marrakesh, were also stripped and reused in buildings elsewhere during the reign of Moulay Isma'il. Other Alawi sultans built or expanded the royal palaces in Fez, in Marrakesh, and in Rabat.

In 1684, during Moulay Isma'il's reign, Tangier was also returned to Moroccan control and much of the city's current Islamic architecture dates from his reign or after. In 1765, Mohammed ibn Abdallah started the construction of the new port city of

In 1684, during Moulay Isma'il's reign, Tangier was also returned to Moroccan control and much of the city's current Islamic architecture dates from his reign or after. In 1765, Mohammed ibn Abdallah started the construction of the new port city of Essaouira

Essaouira ( ; ), known until the 1960s as Mogador (, or ), is a port city in the western Moroccan region of Marrakesh-Safi, on the Atlantic coast. It has 77,966 inhabitants as of 2014.

The foundation of the city of Essaouira was the work of t ...