Sultan Abdülhamit II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Abdulhamid II or Abdul Hamid II (; ; 21 September 184210 February 1918) was the 34th

Abdul Hamid's biggest fear, near dissolution, was realized with the Russian declaration of war on 24 April 1877. In that conflict, the Ottoman Empire fought without help from European allies. Russian chancellor Prince Gorchakov had by that time effectively purchased Austrian neutrality with the

Abdul Hamid's biggest fear, near dissolution, was realized with the Russian declaration of war on 24 April 1877. In that conflict, the Ottoman Empire fought without help from European allies. Russian chancellor Prince Gorchakov had by that time effectively purchased Austrian neutrality with the

Abdul Hamid's distrust of the reformist admirals of the

Abdul Hamid's distrust of the reformist admirals of the

Starting around 1890, Armenians began demanding implementation of the reforms promised to them at the

Starting around 1890, Armenians began demanding implementation of the reforms promised to them at the

Abdul Hamid did not believe that the

Abdul Hamid did not believe that the

In 1898, U.S. Secretary of State

In 1898, U.S. Secretary of State

The

The

Abdul Hamid was conveyed into captivity at Salonica (now

Abdul Hamid was conveyed into captivity at Salonica (now

Abdul Hamid II was a skilled carpenter and personally crafted some high-quality furniture, which can be seen at the

Abdul Hamid II was a skilled carpenter and personally crafted some high-quality furniture, which can be seen at the

Abdul Hamid wrote poetry, following in the footsteps of many other Ottoman sultans. One of his poems translates thus:

Abdul Hamid wrote poetry, following in the footsteps of many other Ottoman sultans. One of his poems translates thus:

Grand Master of the

Grand Master of the  Grand Master of the

Grand Master of the  Grand Master of the

Grand Master of the  Knight of the

Knight of the  Knight of the

Knight of the  Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, ''July 1881'' (

Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Kamehameha I, ''July 1881'' ( Knight Grand Cross of the

Knight Grand Cross of the  Knight Grand Cross of the

Knight Grand Cross of the  Knight of the

Knight of the  Knight Grand Cross of the

Knight Grand Cross of the  Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saint Alexander, ''1897'' (

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saint Alexander, ''1897'' ( Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the

Knight Grand Cross with Collar of the  Knight of the

Knight of the  Knight of the

Knight of the  Knight of the

Knight of the

File: V.M. Doroshevich-East and War-Eunuch near Door of Sultan's Harem enhaced.jpg,

Abdul Hamid II Biography

All Documents about Abdul Hamid in English from a Turkish Web Site

* * Overy, Richard. ''The Times Complete History of the World'', HarperCollins (2010)

II. Abdul Hamid Forum in English

Ödev Sitesi

– about 1,800 photographs mounted in albums, ca. 1880–1893 * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Abdul Hamid II 1842 births 1918 deaths Dethroned monarchs 19th-century sultans of the Ottoman Empire 20th-century sultans of the Ottoman Empire Ottoman people of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) Ottoman people of the Greco-Turkish War (1897) Turks from the Ottoman Empire People from the Ottoman Empire of Circassian descent Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary Sons of sultans Leaders ousted by a coup Conservatism in Turkey Survivors of terrorist attacks

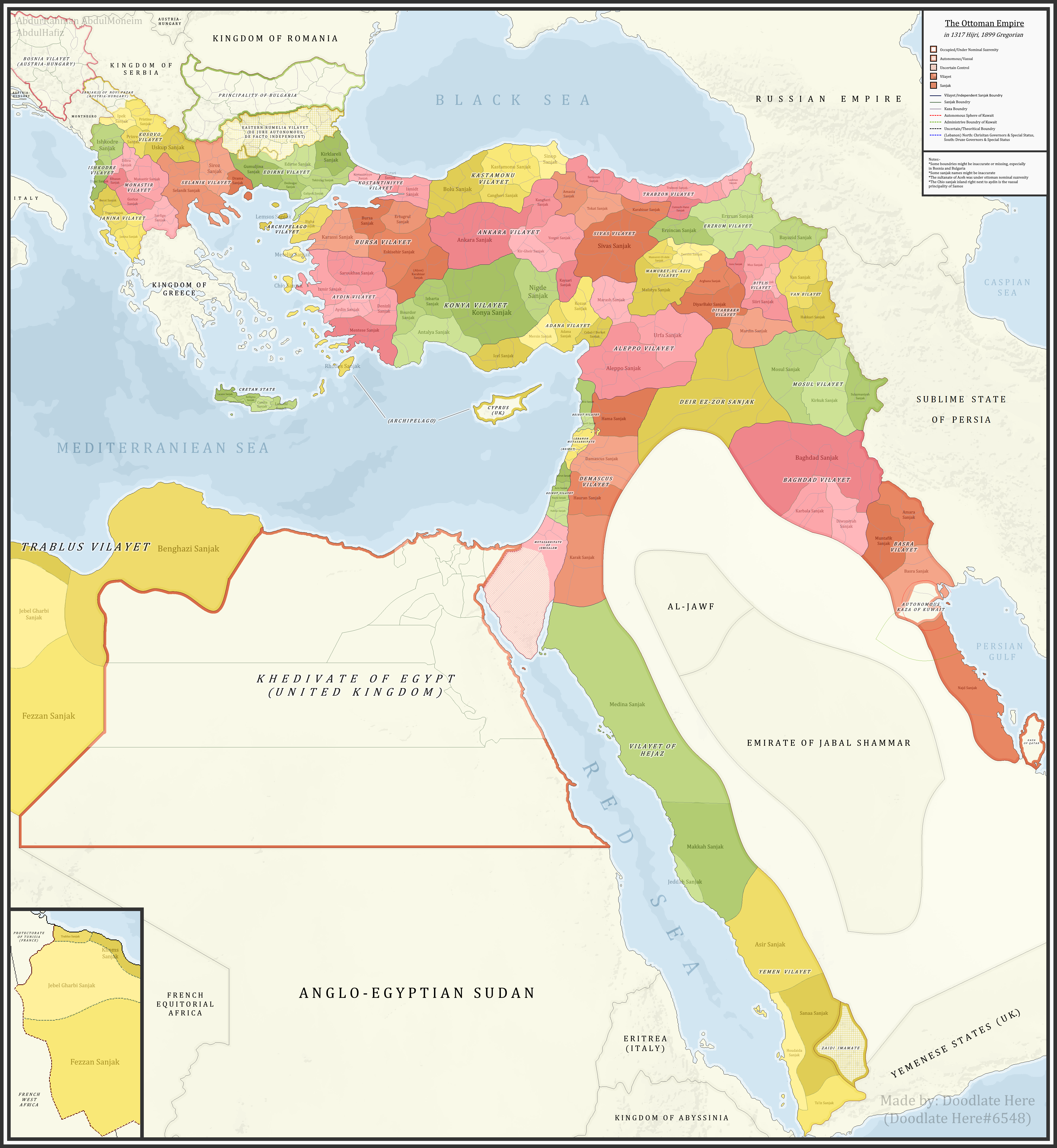

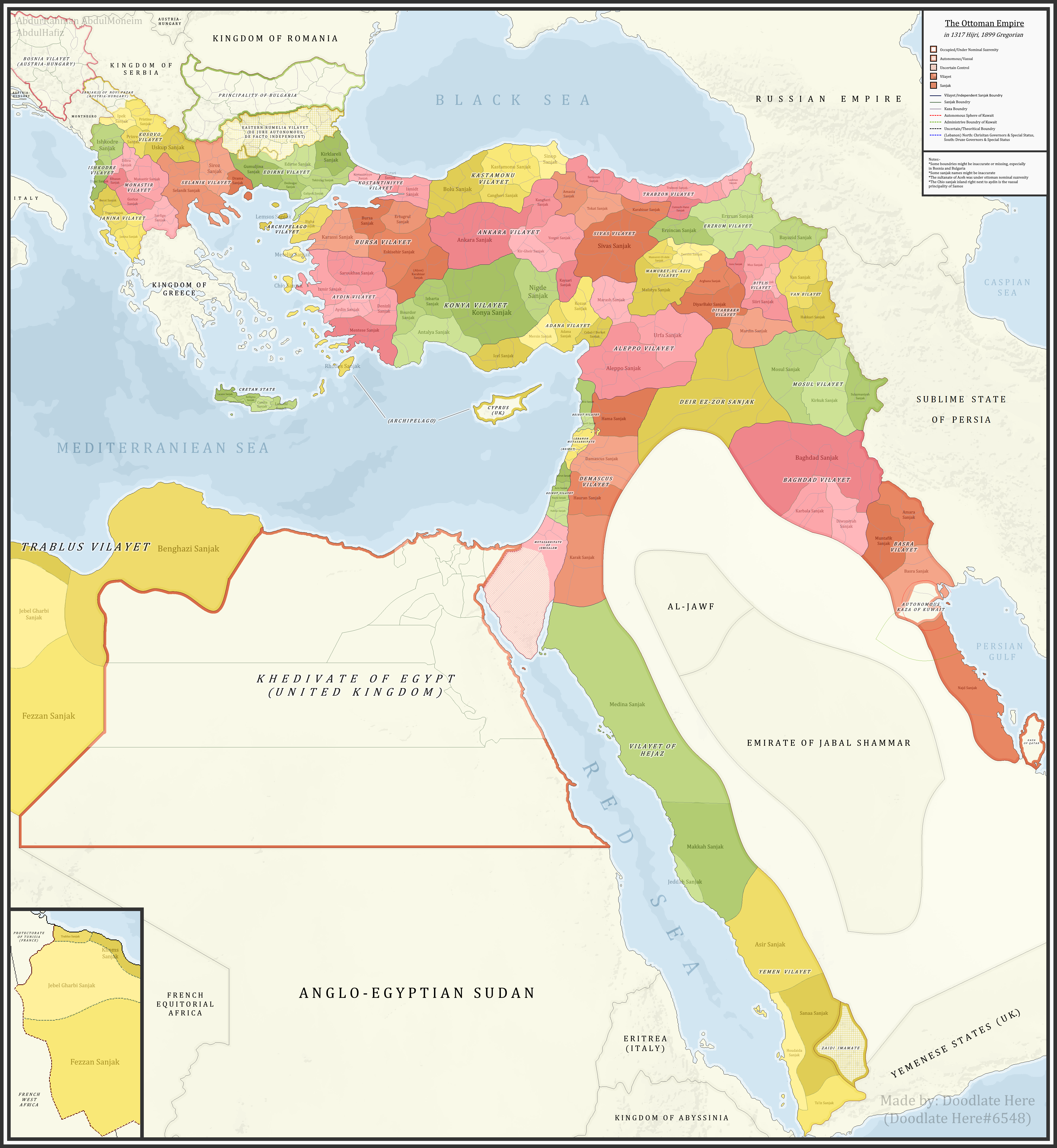

sultan of the Ottoman Empire

The sultans of the Ottoman Empire (), who were all members of the Ottoman dynasty (House of Osman), ruled over the Boundaries between the continents, transcontinental empire from its perceived inception in 1299 to Dissolution of the Ottoman Em ...

, from 1876 to 1909, and the last sultan to exert effective control over the fracturing state. He oversaw a period of decline with rebellions (particularly in the Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

), and presided over an unsuccessful war with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(1877–78), the loss of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Bulgaria

Bulgaria, officially the Republic of Bulgaria, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern portion of the Balkans directly south of the Danube river and west of the Black Sea. Bulgaria is bordered by Greece and Turkey t ...

, Serbia, Montenegro, Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

, and Thessaly

Thessaly ( ; ; ancient Aeolic Greek#Thessalian, Thessalian: , ) is a traditional geographic regions of Greece, geographic and modern administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece, comprising most of the ancient Thessaly, a ...

from Ottoman control (1877–1882), followed by a successful war against Greece in 1897, though Ottoman gains were tempered by subsequent Western European intervention.

Elevated to power in the wake of Young Ottoman

The Young Ottomans (; ) were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the ''Tanzimat'' reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough. The Young Ottomans sough ...

coups, he promulgated the Ottoman Empire's first constitution, a sign of the progressive thinking that marked his early rule. But his enthronement came in the context of the Great Eastern Crisis

The Great Eastern Crisis of 1875–1878 began in the Ottoman Empire's Rumelia, administrative territories in the Balkan Peninsula in 1875, with the outbreak of several uprisings and wars that resulted in the intervention of international powers, ...

, which began with the Empire's default on its loans, uprisings by Christian Balkan minorities, and a war with the Russian Empire. At the end of the crisis, Ottoman rule in the Balkans and its international prestige were severely diminished, and the Empire lost its economic sovereignty as its finances came under the control of the Great Powers

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power ...

through the Ottoman Public Debt Administration

The Ottoman Public Debt Administration (OPDA) (, or simply ''Düyun-u Umumiye'' as it was popularly known, , ), was a European-controlled organization that was established in 1881 to collect the payments which the Ottoman Empire owed to European ...

.

In 1878, Abdul Hamid consolidated his rule by suspending both the constitution and the parliament, , and curtailing the power of the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

. He ruled as an autocrat for three decades. Ideologically an Islamist, the sultan asserted his title of Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

to Muslims around the world. His paranoia about being overthrown, like his uncle

An uncle is usually defined as a male relative who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent, as well as the parent of the cousins. Uncles who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. The female counterpart of an un ...

and half-brother

A sibling is a relative that shares at least one parent with the other person. A male sibling is a brother, and a female sibling is a sister. A person with no siblings is an only child.

While some circumstances can cause siblings to be raised ...

, led to the creation of secret

Secrecy is the practice of hiding information from certain individuals or groups who do not have the "need to know", perhaps while sharing it with other individuals. That which is kept hidden is known as the secret.

Secrecy is often controver ...

police

The police are Law enforcement organization, a constituted body of Law enforcement officer, people empowered by a State (polity), state with the aim of Law enforcement, enforcing the law and protecting the Public order policing, public order ...

organizations and a censorship regime. The Ottoman Empire's modernization and centralization continued during his reign, including reform of the bureaucracy, extension of the Rumelia Railway and the Anatolia Railway, and construction of the Baghdad Railway

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

and the Hejaz Railway. Systems for population registration, sedentarization

In anthropology, sedentism (sometimes called sedentariness; compare sedentarism) is the practice of living in one place for a long time. As of , the large majority of people belong to sedentary cultures. In evolutionary anthropology and arch ...

of tribal groups, and control over the press were part of a unique imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

system in fringe provinces known as borrowed colonialism. The farthest-reaching reforms were in education, with many professional schools established in fields such as law, arts, trades, civil engineering, veterinary medicine, customs, farming, and linguistics, along with the first local modern law school in 1898. A network of primary, secondary, and military schools extended throughout the Empire. German firms played a major role in developing the Empire's railway and telegraph systems.

Ironically, the same education institutions that the Sultan sponsored proved to be his downfall. Large sections of the pro-constitutionalist Ottoman intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

sharply criticized and opposed him for his repressive policies, which coalesced into the Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

movement. Ethnic minorities started organizing their own national liberation movements

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ...

, resulting in insurgencies in Macedonia

Macedonia (, , , ), most commonly refers to:

* North Macedonia, a country in southeastern Europe, known until 2019 as the Republic of Macedonia

* Macedonia (ancient kingdom), a kingdom in Greek antiquity

* Macedonia (Greece), a former administr ...

and Eastern Anatolia

The Eastern Anatolia region () is a geographical region of Turkey. The most populous province in the region is Van Province. Other populous provinces are Malatya, Erzurum and Elazığ.

It is bordered by the Black Sea Region and Georgia in th ...

. Armenians especially suffered from massacres

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

and pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s at the hands of the ''Hamidiye'' regiments. Of the many assassination attempts during Abdul Hamid's reign, one of the most famous is the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (, abbr. ARF (ՀՅԴ) or ARF-D), also known as Dashnaktsutyun (Armenians, Armenian: Դաշնակցություն, Literal translation, lit. "Federation"), is an Armenian nationalism, Armenian nationalist a ...

's Yıldız assassination attempt of 1905. In 1908, the Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

forced him to recall parliament and reinstate the constitution in the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II ...

. Abdul Hamid II attempted to reassert his absolutism a year later, resulting in his deposition by pro-constitutionalist forces in the 31 March incident

The 31 March incident () was an uprising in the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. The incident broke out during the night of 30–31 Mart 1325 in Rumi calendar ( GC 12–13 April 1909), thus named after 31 Mar ...

, though the role he played in these events is disputed.

Abdul Hamid has been long vilified as a reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

"Red Sultan" for his tyrannical leadership and condoning of atrocities. It was initial consensus that his personal rule accelerated disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, holding back modernization during the otherwise dynamic Belle Époque

The Belle Époque () or La Belle Époque () was a period of French and European history that began after the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871 and continued until the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Occurring during the era of the Fr ...

. Recent assessments have highlighted his promotion of education and public works projects, his reign a culmination and advancement of the ''Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

'' reforms. Since the AKP's rise to power, scholars have attributed a resurgence in his personality cult an attempt to check Mustafa Kemal Atatürk

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk ( 1881 – 10 November 1938) was a Turkish field marshal and revolutionary statesman who was the founding father of the Republic of Turkey, serving as its first President of Turkey, president from 1923 until Death an ...

's established image as the founder of modern Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

.

Early life

HamidEfendi

Effendi or effendy ( ; ; originally from ) is a title of nobility meaning ''sir'', ''lord'' or ''master'', especially in the Ottoman Empire and the Caucasus''.'' The title itself and its other forms are originally derived from Medieval Greek ...

was born on 21 September 1842 either in Çırağan Palace

Çırağan Palace (), a former Ottoman palace, is now a five-star hotel in the Kempinski Hotels chain. It is located on the European shore of the Bosporus, between Beşiktaş and Ortaköy in Istanbul, Turkey.

The Sultan Suite, billed at pe ...

, Ortaköy

Ortaköy (, ''Middle Village)'' is a neighbourhood in the municipality and district of Beşiktaş, Istanbul Province, Turkey. Its population is 9,121 (2024). It is on the European shore of the Bosphorus. it was originally a small fishing villag ...

, or at Topkapı Palace

The Topkapı Palace (; ), or the Seraglio, is a large museum and library in the east of the Fatih List of districts of Istanbul, district of Istanbul in Turkey. From the 1460s to the completion of Dolmabahçe Palace in 1856, it served as the ad ...

, both in Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. He was the son of Sultan Abdulmejid I ʻAbd al-Majīd (ALA-LC romanization of , ), also spelled as Abd ul Majid, Abd ul-Majid, Abd ol Majid, Abd ol-Majid, and Abdolmajid, is a Muslim male given name and, in modern usage, surname. It is built from the Arabic words '' ʻabd'' and ''al-Maj ...

and Tirimüjgan Kadın

Gülnihal Tirimüjgan Kadın (16 October 1819 – 3 October 1852; , ''young rose'' and ''darting eyelashes'') was a consort of Sultan Abdulmejid I, and the mother of Sultan Abdul Hamid II of the Ottoman Empire.

Early life

Tirimüjgan was of Sha ...

(Circassia

Circassia ( ), also known as Zichia, was a country and a historical region in . It spanned the western coastal portions of the North Caucasus, along the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. Circassia was conquered by the Russian Empire during ...

, 20 August 1819Constantinople, Feriye Palace

The Feriye Palace () is a complex of Ottoman imperial palace buildings along the European shoreline of the Bosphorus strait in Istanbul, Turkey. Currently, the buildings host educational institutions such as a high school and a university.

Histo ...

, 2 November 1853), originally named Virjinia. Following his mother's death, he became the adoptive son of his father's legal wife, Perestu Kadın

Rahime Perestu Sultan ( and 'swallow'; 1830 – 1904), also known as Rahime Perestu Kadın, was the first legal wife of Sultan Abdulmejid I of the Ottoman Empire. She was given the title and position of Valide sultan (Queen mother) when Abdul ...

. Perestu was also the adoptive mother of Abdul Hamid's half-sister Cemile Sultan

Cemile Sultan (; "''beautiful, radiant''"; 17 August 1843 – 26 February 1915) was an Ottoman dynasty, Ottoman princess, the daughter of Sultan Abdulmejid I and Düzdidil Hanım. She was the half sister of Sultans Murad V, Abdul Hamid II, Mehme ...

, whose mother Düzdidil Kadın had died in 1845, leaving her motherless at the age of two. The two were brought up in the same household, where they spent their childhood together.

Unlike many other Ottoman sultans, Abdul Hamid II visited distant countries. In the summer of 1867, nine years before he ascended the throne, he accompanied his uncle Sultan Abdul Aziz on a visit to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

(30 June – 10 July 1867), London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

(12–23 July 1867), Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

(28–30 July 1867), and capitals or cities of a number of other European countries.

Accession to the Ottoman throne

Abdul Hamid ascended the throne after his brotherMurad

Murad or Mourad () is an Arabic name. It is also common in Armenian, Azerbaijani, Bengali, Turkish, Persian, and Berber as a male given name or surname and is commonly used throughout the Muslim world and Middle East.

Etymology

It is derived ...

was deposed on 31 August 1876. At his accession, some commentators were impressed that he rode practically unattended to the Eyüp Sultan Mosque

The Eyüp Sultan Mosque () is a mosque in Eyüp district of Istanbul, Turkey. The mosque complex includes a mausoleum marking the spot where Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, Ebu Eyüp el-Ansari (Abu Ayyub al-Ansari), the standard-bearer and companion of the ...

, where he was presented with the Sword of Osman

The Sword of Osman (; ) is an important sword of state that was used during the enthronement ceremony () of the sultans of the Ottoman Empire, from the accession of Murad II onwards. This particular type of enthronement ceremony was the Ottoman va ...

. Most people expected Abdul Hamid II to support liberal movements, but he acceded to the throne at a critical time. Economic and political turmoil, local wars in the Balkans, and the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

threatened the Empire's very existence.

First Constitutional Era, 1876–1878

Abdul Hamid worked with theYoung Ottomans

The Young Ottomans (; ) were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the '' Tanzimat'' reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough. The Young Ottomans soug ...

to realize some form of constitutional arrangement. This new form could help bring about a liberal transition with an Islamic provenance. The Young Ottomans believed that the modern parliamentary system was a restatement of the practice of consultation, or ''shura

Shura () is the term for collective decision-making in Islam. It can, for example, take the form of a council or a referendum. The Quran encourages Muslims to decide their affairs in consultation with each other.

Shura is mentioned as a praise ...

'', that had existed in early Islam.

In December 1876, due to the 1875 insurrection in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the ongoing war with Serbia and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, and the feeling aroused throughout Europe by the cruelty used in stamping out the 1876 Bulgarian rebellion, Abdul Hamid promulgated a constitution and a parliament. Midhat Pasha

Ahmed Şefik Midhat Pasha (; 1822 – 26 April 1883) was an Ottoman politician, reformist, and statesman. He was the author of the Constitution of the Ottoman Empire.

Midhat was born in Istanbul and educated from a private . In July 1872, he ...

headed the commission to establish a new constitution, and the cabinet passed the constitution on 6 December 1876, allowing for a bicameral legislature

Bicameralism is a type of legislature that is divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single ...

with senatorial appointments made by the sultan. The first ever election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

in the Ottoman Empire was held in 1877. Crucially, the constitution gave Abdul Hamid the right to exile anyone he deemed a threat to the state.

The delegates to the Constantinople Conference

The 1876–77 Constantinople Conference ( "Shipyard Conference", after the venue ''Tersane Sarayı'' "Shipyard Palace") of the Great Powers (Austria-Hungary, Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Russia) was held in Constantinople (now Istanbul) f ...

were surprised by the promulgation of a constitution, but European powers at the conference rejected the constitution as a too-radical change; they preferred the 1856 constitution ('' Islâhat Hatt-ı Hümâyûnu)'' or the 1839 Gülhane edict ( ''Hatt-ı Şerif''), and questioned whether a parliament was necessary to act as an official voice of the people.

In any event, like many other would-be reforms of the Ottoman Empire, it proved nearly impossible. Russia continued to mobilize for war, and early in 1877 the Ottoman Empire went to war with the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

.

War with Russia

Abdul Hamid's biggest fear, near dissolution, was realized with the Russian declaration of war on 24 April 1877. In that conflict, the Ottoman Empire fought without help from European allies. Russian chancellor Prince Gorchakov had by that time effectively purchased Austrian neutrality with the

Abdul Hamid's biggest fear, near dissolution, was realized with the Russian declaration of war on 24 April 1877. In that conflict, the Ottoman Empire fought without help from European allies. Russian chancellor Prince Gorchakov had by that time effectively purchased Austrian neutrality with the Reichstadt Agreement

On the occasion of the Balkan crisis, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary and Russian Tsar Alexander II met on 8 July 1876 for secret talks, the results of which were later termed the Reichstadt Agreement (also: Reichstadt Convention) by h ...

. The British Empire, though still fearing the Russian threat to the British presence in India, did not involve itself in the conflict because of public opinion against the Ottomans, following reports of Ottoman brutality in putting down the Bulgarian uprising. Russia's victory was quick; the conflict ended in February 1878. The Treaty of San Stefano

The 1878 Preliminary Treaty of San Stefano (; Peace of San-Stefano, ; Peace treaty of San-Stefano, or ) was a treaty between the Russian and Ottoman empires at the conclusion of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. It was signed at San Ste ...

, signed at the end of the war, imposed harsh terms: the Ottoman Empire gave independence to Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Serbia, and Montenegro; it granted autonomy to Bulgaria; instituted reforms in Bosnia and Herzegovina; and ceded parts of Dobrudzha to Romania and parts of Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

to Russia, which was also paid an enormous indemnity. After the war, Abdul Hamid suspended the constitution in February 1878 and dismissed the parliament, after its only meeting, in March 1877. For the next three decades, Abdul Hamid ruled the Ottoman Empire from Yıldız Palace

Yıldız Palace (, ) is a vast complex of former imperial Ottoman Empire, Ottoman pavilions and villas in Beşiktaş, Istanbul, Turkey, built in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was used as a residence by the List of sultans of the Ottoman ...

.

As Russia could dominate the newly independent states, the Treaty of San Stefano greatly increased its influence in Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

. At the Great Powers' insistence (especially the United Kingdom's), the treaty was revised at the Congress of Berlin

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

so as to reduce the great advantages Russia gained. In exchange for these favors, Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

was ceded to Britain in 1878. There were troubles in Egypt, where a discredited ''khedive

Khedive ( ; ; ) was an honorific title of Classical Persian origin used for the sultans and grand viziers of the Ottoman Empire, but most famously for the Khedive of Egypt, viceroy of Egypt from 1805 to 1914.Adam Mestyan"Khedive" ''Encyclopaedi ...

'' had to be deposed. Abdul Hamid mishandled relations with Urabi Pasha

Ahmed Urabi (; Arabic: ; 31 March 1841 – 21 September 1911), also known as Ahmed Ourabi or Orabi Pasha, was an Egyptian military officer. He was the first political and military leader in Egypt to rise from the ''fellahin'' (peasantry). Urabi p ...

, and as a result, Britain gained de facto control over Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

by sending its troops in 1882 to establish control over the two provinces. Cyprus, Egypt, and Sudan ostensibly remained Ottoman provinces until 1914, when Britain officially annexed them in response to the Ottoman participation in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

on the side of the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

.

Reign

Disintegration

Abdul Hamid's distrust of the reformist admirals of the

Abdul Hamid's distrust of the reformist admirals of the Ottoman Navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

(whom he suspected of plotting against him and trying to restore the constitution) and his subsequent decision to lock the Ottoman fleet (the world's third-largest fleet during the reign of his predecessor Abdul Aziz) inside the Golden Horn

The Golden Horn ( or ) is a major urban waterway and the primary inlet of the Bosphorus in Istanbul, Turkey. As a natural estuary that connects with the Bosphorus Strait at the point where the strait meets the Sea of Marmara, the waters of the ...

indirectly caused the loss of Ottoman overseas territories and islands in North Africa, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Aegean Sea during and after his reign.

Financial difficulties forced him to consent to foreign control over the Ottoman national debt. In a decree issued in December 1881, a large portion of the empire's revenues were handed over to the Public Debt Administration for the benefit of (mostly foreign) bondholders (see Kararname of 1296).

The 1885 union of Bulgaria with Eastern Rumelia

Eastern Rumelia (; ; ) was an autonomous province (''oblast'' in Bulgarian, ''vilayet'' in Turkish) of the Ottoman Empire with a total area of , which was created in 1878 by virtue of the Treaty of Berlin (1878), Treaty of Berlin and ''de facto'' ...

was another blow to the Empire. The creation of an independent and powerful Bulgaria was viewed as a serious threat to the Empire. For many years Abdul Hamid had to deal with Bulgaria in a way that did not antagonize the Russians or the Germans. There were also key problems regarding the Albania

Albania ( ; or ), officially the Republic of Albania (), is a country in Southeast Europe. It is located in the Balkans, on the Adriatic Sea, Adriatic and Ionian Seas within the Mediterranean Sea, and shares land borders with Montenegro to ...

n question resulting from the Albanian League of Prizren

The League of Prizren (), officially the League for the Defense of the Rights of the Albanian Nation (), was an Albanian political organization that was officially founded on June 10, 1878 in the old town of Prizren in the Kosovo Vilayet of th ...

and with the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

and Montenegrin frontiers, where the European powers were determined that the Berlin Congress

At the Congress of Berlin (13 June – 13 July 1878), the major European powers revised the territorial and political terms imposed by the Russian Empire on the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of San Stefano (March 1878), which had ended the Rus ...

's decisions be carried out.

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

was granted "extended privileges", but these did not satisfy the population, which sought unification with Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. In early 1897 a Greek expedition sailed to Crete to overthrow Ottoman rule on the island. This act was followed by the Greco-Turkish War, in which the Ottoman Empire defeated Greece, but as a result of the Treaty of Constantinople, Crete was taken over ''en depot'' by the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. Prince George of Greece

Prince George of Greece and Denmark (; 24 June 1869 – 25 November 1957) was the second son and child of George I of Greece and Olga Konstantinovna of Russia, and is remembered chiefly for having once saved the life of his cousin the future E ...

was appointed ruler and Crete was effectively lost to the Ottoman Empire. The ʿAmmiyya, a revolt in 1889–90 among Druze

The Druze ( ; , ' or ', , '), who Endonym and exonym, call themselves al-Muwaḥḥidūn (), are an Arabs, Arab Eastern esotericism, esoteric Religious denomination, religious group from West Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic ...

and other Syrians

Syrians () are the majority inhabitants of Syria, indigenous to the Levant, most of whom have Arabic, especially its Levantine Arabic, Levantine and Mesopotamian Arabic, Mesopotamian dialects, as a mother tongue. The culture of Syria, cultural ...

against excesses of the local sheikhs, similarly led to capitulation to the rebels' demands, as well as concessions to Belgian and French companies to provide a railroad between Beirut and Damascus.

Political decisions and reforms

Most people expected Abdul Hamid II to have liberal ideas, and some conservatives were inclined to regard him with suspicion as a dangerous reformer. Despite working with the reformistYoung Ottomans

The Young Ottomans (; ) were a secret society established in 1865 by a group of Ottoman intellectuals who were dissatisfied with the '' Tanzimat'' reforms in the Ottoman Empire, which they believed did not go far enough. The Young Ottomans soug ...

while still crown prince and appearing to be a liberal leader, he became increasingly conservative after taking the throne. In a process known as ''İstibdad'', Abdul Hamid reduced his ministers to acting as secretaries and concentrated much of the Empire's administration into his own hands. Default in the public funds, an empty treasury, the 1875 insurrection in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the war with Serbia and Montenegro

, image_flag = Flag of Montenegro.svg

, image_coat = Coat of arms of Montenegro.svg

, coa_size = 80

, national_motto =

, national_anthem = ()

, image_map = Europe-Mont ...

, the result of Russo-Turkish war

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, and the feeling aroused throughout Europe by Abdul Hamid's government in stamping out the Bulgarian rebellion all contributed to his apprehension regarding enacting significant changes.

His push for education resulted in the establishment of 18 professional schools; and in 1900, Darülfünûn-u Şahâne, now known as Istanbul University

Istanbul University, also known as University of Istanbul (), is a Public university, public research university located in Istanbul, Turkey. Founded by Mehmed II on May 30, 1453, a day after Fall of Constantinople, the conquest of Constantinop ...

, was established. He also created a large system of primary, secondary, and military schools throughout the empire. 51 secondary schools were constructed in a 12-year period (1882–1894). As the goal of the educational reforms in the Hamidian era were to counter foreign influence, these secondary schools used European teaching techniques while instilling in students a strong sense of Ottoman identity and Islamic morality.

Abdul Hamid also reorganized the Ministry of Justice

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice, is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a ...

and developed rail and telegraph systems. The telegraph system was expanded to incorporate the furthest parts of the Empire. Railways connected Constantinople and Vienna by 1883, and shortly afterward the Orient Express

The ''Orient Express'' was a long-distance passenger luxury train service created in 1883 by the Belgian company ''Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits'' (CIWL) that operated until 2009. The train traveled the length of continental Europe, w ...

connected Paris to Constantinople. During his rule, railways within the Ottoman Empire expanded to connect Ottoman-controlled Europe and Anatolia with Constantinople as well. The increased ability to travel and communicate within the Ottoman Empire served to strengthen Constantinople's influence over the rest of the Empire.

Abdul Hamid introduced legislation against the slave trade via the Anglo-Ottoman Convention of 1880 and the Kanunname of 1889.

Abdul Hamid took stringent measures regarding his security. The memory of the deposition of Abdul Aziz was on his mind and convinced him that a constitutional government was not a good idea. Because of this, information was tightly controlled and the press rigidly censored. A secret police ( Umur-u Hafiye) and a network of informants was present throughout the empire, and many leading figures of the Second Constitutional Era

The Second Constitutional Era (; ) was the period of restored parliamentary rule in the Ottoman Empire between the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the 1920 retraction of the constitution, after the dissolution of the Chamber of Deputies, during the ...

and Ottoman successor states were arrested or exiled. School curricula were closely inspected to prevent dissidence. Ironically, the schools that Abdul Hamid founded and tried to control became "breeding grounds of discontent" as students and teachers alike chafed at the censors' clumsy restrictions.

Armenian question

Starting around 1890, Armenians began demanding implementation of the reforms promised to them at the

Starting around 1890, Armenians began demanding implementation of the reforms promised to them at the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

. To prevent such measures, in 1890–91 Abdul Hamid gave semi-official status to the bandits who were already actively mistreating the Armenians

Armenians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to the Armenian highlands of West Asia.Robert Hewsen, Hewsen, Robert H. "The Geography of Armenia" in ''The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiq ...

in the provinces. Made up of Kurds and other ethnic groups such as Turcomans, and armed by the state, they came to be called the '' Hamidiye Alayları'' ("Hamidian Regiments"). The Hamidiye and Kurdish brigands were given free rein to attack Armenians – confiscating stores of grain, foodstuffs, and driving off livestock – confident of escaping punishment as they were subject only to court-martial. In the face of such violence, the Armenians established revolutionary organizations: the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party

The Social Democrat Hunchakian Party (SDHP) (), is the oldest continuously-operating Armenian political party, founded in 1887 by a group of students in Geneva, Switzerland. It was the first socialist party to operate in the Ottoman Empire and i ...

(Hunchak; founded in Switzerland in 1887) and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation (, abbr. ARF (ՀՅԴ) or ARF-D), also known as Dashnaktsutyun (Armenians, Armenian: Դաշնակցություն, Literal translation, lit. "Federation"), is an Armenian nationalism, Armenian nationalist a ...

(the ARF or Dashnaktsutiun, founded in 1890 in Tiflis

Tbilisi ( ; ka, თბილისი, ), in some languages still known by its pre-1936 name Tiflis ( ), ( ka, ტფილისი, tr ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Georgia (country), largest city of Georgia ( ...

). Unrest ensued and clashes occurred in 1892 at Merzifon

Merzifon is a town in Amasya Province in the central Black Sea region of Turkey. It is the seat of Merzifon District.

and in 1893 at Tokat

Tokat is a city of Turkey in the mid-Black Sea region of Anatolia. It is the seat of Tokat Province and Tokat District.

. Abdul Hamid put these revolts down with harsh methods. As a result, 300,000 Armenians were killed in what became known as the Hamidian massacres

The Hamidian massacres also called the Armenian massacres, were massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in the mid-1890s. Estimated casualties ranged from 100,000 to 300,000, Akçam, Taner (2006) '' A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide a ...

. News of the massacres was widely reported in Europe and the United States and drew strong responses from foreign governments and humanitarian organizations. Abdul Hamid was called the "Bloody Sultan" or "Red Sultan" in the West. On 21 July 1905, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation attempted to assassinate him with a car bomb during a public appearance, but he was delayed for a minute, and the bomb went off too early, killing 26, wounding 58 (four of whom died during their treatment in hospital), and destroying 17 cars. This continued aggression, along with the handling of the Armenian desire for reform, led western European powers to take a more hands-on approach with the Turks. Abdul Hamid survived an attempted stabbing in 1904 as well.

Foreign policy

Pan-Islamism

Abdul Hamid did not believe that the

Abdul Hamid did not believe that the Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

movement could succeed in helping the disparate peoples of the empire achieve a common identity, such as Ottomanism

Ottomanism or ''Osmanlılık'' (, . ) was a concept which developed prior to the 1876–1878 First Constitutional Era of the Ottoman Empire. Its proponents believed that it could create the Unity of the Peoples, , needed to keep religion-based ...

. He adopted a new ideological principle, Pan-Islamism

Pan-Islamism () is a political movement which advocates the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Historically, after Ottomanism, which aimed at ...

; since, beginning in 1517, Ottoman sultans were also nominally Caliphs, he wanted to promote that fact and emphasized the Ottoman Caliphate

The Ottoman Caliphate () was the claim of the heads of the Turkish Ottoman dynasty, rulers of the Ottoman Empire, to be the caliphs of Islam during the Late Middle Ages, late medieval and Early Modern period, early modern era.

Ottoman rulers ...

. Given the great diversity of ethnicities in the Ottoman Empire, he believed that Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

was the only way to unite his people.

Pan-Islamism encouraged Muslims living under European powers to unite under one polity. This threatened several European countries: Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

through Bosnian Muslim

Islam is the most widespread religion in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It was introduced to the local population in the 15th and 16th centuries as a result of the Ottoman conquest of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Muslims make the largest religious co ...

s; Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

through Tatars

Tatars ( )Tatar

in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

and in the Collins English Dictionary are a group of Turkic peoples across Eas ...

Kurds

Kurds (), or the Kurdish people, are an Iranian peoples, Iranic ethnic group from West Asia. They are indigenous to Kurdistan, which is a geographic region spanning southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeastern Syri ...

; France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

through Moroccan Muslims; and Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

through India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n Muslims. Foreigners' privileges in the Ottoman Empire, which were an obstacle to effective government, were curtailed. At the very end of his reign, Abdul Hamid finally provided funds to start construction of the strategically important Constantinople-Baghdad Railway and the Constantinople-Medina Railway, which would ease the trip to Mecca for the Hajj

Hajj (; ; also spelled Hadj, Haj or Haji) is an annual Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, the holiest city for Muslims. Hajj is a mandatory religious duty for capable Muslims that must be carried out at least once in their lifetim ...

; after he was deposed, the CUP accelerated and completed construction of both railways. Missionaries were sent to distant countries preaching Islam and the Caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

's supremacy. During his rule, Abdul Hamid refused Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian Jewish journalist and lawyer who was the father of Types of Zionism, modern political Zionism. Herzl formed the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organizat ...

's offers to pay down a substantial portion of the Ottoman debt (150 million pounds sterling in gold) in exchange for a charter allowing the Zionists

Zionism is an ethnocultural nationalist movement that emerged in Europe in the late 19th century that aimed to establish and maintain a national home for the Jewish people, pursued through the colonization of Palestine, a region roughly cor ...

to settle in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

. He is famously quoted as telling Herzl's Emissary, "as long as I am alive, I will not have our body divided; only our corpse they can divide."

Pan-Islamism was a considerable success. After the Greco-Ottoman war, many Muslims celebrated the Ottoman victory as their victory. Uprisings, lockouts, and objections to European colonization in newspapers were reported in Muslim regions after the war. But Abdul Hamid's appeals to Muslim sentiment were not always very effective, due to widespread disaffection within the Empire. In Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

and Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, disturbance was endemic; nearer home, a semblance of loyalty was maintained in the army and among the Muslim population only by a system of deflation and espionage.

America and the Philippines

In 1898, U.S. Secretary of State

In 1898, U.S. Secretary of State John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a Secretary to the President of the United States, private secretary for Abraha ...

asked United States Minister to the Ottoman Empire Oscar Straus to request that Abdul Hamid, in his capacity as caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

, write a letter to the Sulu Muslims, a Moro subgroup, of the Sulu Sultanate

The Sultanate of Sulu (; ; ) is a Sunni Muslim subnational monarchy in the Republic of the Philippines that includes the Sulu Archipelago, coastal areas of Zamboanga City and certain portions of Palawan in today's Philippines. Historicall ...

in the Philippines, ordering them not to join the Moro Rebellion

The Moro Rebellion (1902–1913) was an armed conflict between the Moro people and the United States military during the Philippine–American War. The rebellion occurred after the conclusion of the conflict between the United States and Fir ...

and submit to American suzerainty and American military rule. The Sultan obliged the Americans and wrote the letter, which was sent to Mecca, whence two Sulu chiefs brought it to Sulu. It was successful, since the "Sulu Mohammedans ... refused to join the insurrectionists and had placed themselves under the control of our army, thereby recognizing American sovereignty."

Despite Abdul Hamid's "pan-Islamic" ideology, he had readily acceded to Straus's request for help in telling the Sulu Muslims to not resist America, since he felt no need to cause hostilities between the West and Muslims. Collaboration between the American military and Sulu Sultanate was due to the Ottoman Sultan persuading the Sulu Sultan. John P. Finley wrote:

President McKinley did not mention the Ottoman role in the pacification of the Sulu Moros in his address to the first session of the Fifty-sixth Congress in December 1899, since the agreement with the Sultan of Sulu was not submitted to the Senate until 18 December. The Bates Treaty, which the Americans signed with the Moro Sulu Sultanate, and which guaranteed the Sultanate's autonomy in its internal affairs and governance, was then violated by the Americans, who then invaded Moroland, causing the Moro Rebellion

The Moro Rebellion (1902–1913) was an armed conflict between the Moro people and the United States military during the Philippine–American War. The rebellion occurred after the conclusion of the conflict between the United States and Fir ...

to break out in 1904, with war raging between the Americans and Moro Muslims and atrocities committed against Moro Muslim women and children, such as the Moro Crater Massacre

The First Battle of Bud Dajo, also known as the Moro Crater Massacre, was a counterinsurgency action conducted by the United States Army and United States Marine Corps, Marine Corps against the Moro people in March 1906, during the Moro Rebellion ...

.

Germany's support

The

The Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

– the United Kingdom, France and Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

– had strained relations with the Ottoman Empire. Abdul Hamid and his close advisors believed the Empire should be treated as an equal player by these great powers. In the Sultan's view, the Ottoman Empire was a European empire that was distinguished by having more Muslims than Christians.

Over time, the hostile diplomatic attitudes of France (the occupation of Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

in 1881) and Great Britain (the 1882 establishment of de facto control in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

) caused Abdul Hamid to gravitate towards Germany. Abdul Hamid twice hosted Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty ...

in Istanbul, on 21 October 1889 and on 5 October 1898. (Wilhelm II later visited Constantinople a third time, on 15 October 1917, as a guest of Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd (; or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) was the penultimate List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1909 to 1918. Mehmed V reigned as a Constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarch. He had ...

.) German officers such as Baron von der Goltz and Bodo-Borries von Ditfurth were employed to oversee the organization of the Ottoman Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire () was the armed forces of the Ottoman Empire. It was founded in 1299 and dissolved in 1922.

Army

The Military of the Ottoman Empire can be divided in five main periods. The foundation era covers the years ...

.

German government officials were brought in to reorganize the Ottoman government's finances. The German emperor was also rumored to have counseled Abdul Hamid in his controversial decision to appoint his third son as his successor. Germany's friendship was not altruistic; it had to be fostered by railway and loan concessions. In 1899, a significant German wish, the construction of a Berlin-Baghdad railway, was granted.

Kaiser Wilhelm II also requested the Sultan's help when he had trouble with Chinese Muslim troops. During the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

, the Chinese Muslim Kansu Braves

The Gansu Braves or Gansu Army was a combined army division of 10,000 Chinese Muslim troops from the northwestern province of Kansu (Gansu) in the last decades of the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). Loyal to the Qing, the Braves were recruited i ...

fought the German Army, routing them and the other Eight Nation Alliance forces. The Muslim Kansu Braves and Boxers defeated the Alliance forces led by the German Captain Guido von Usedom at the Battle of Langfang

The Battle of Langfang () took place during the Seymour Expedition during the Boxer Rebellion, in June 1900, involving Chinese imperial troops, the Chinese Muslim Kansu Braves and Boxers ambushing and defeating the Eight-Nation Alliance expedi ...

during the Seymour Expedition

The Seymour Expedition () was an attempt by a multinational military force led by Admiral Edward Seymour to march to Beijing and relieve the Siege of the Legations from attacks by Qing China government troops and the Boxers in 1900. The Chines ...

, in 1900, and besieged the trapped Alliance forces during the Siege of the International Legations

The siege of the International Legations was a pivotal event during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, in which foreign diplomatic compounds in Peking (now Beijing) were besieged by Chinese Boxers and Qing Dynasty troops. The Boxers, fueled by anti-f ...

. It was only on the second attempt, in the Gasalee Expedition

The Gaselee Expedition was a successful relief by a multi-national military force to march to Beijing and protect the diplomatic legations and foreign nationals in the city from attacks in 1900. The expedition was part of the war of the Boxer Re ...

, that the Alliance forces managed to get through to battle the Chinese Muslim troops at the Battle of Peking. Wilhelm was so alarmed by the Chinese Muslim troops that he requested that Abdul Hamid find a way to stop the Muslim troops from fighting. Abdul Hamid agreed to Wilhelm's demands and sent Hasan Enver Pasha

Hasan Enver Pasha, (; 1857, Istanbul – 1929, Istanbul) was an Ottoman Turkish general.

Personal life

He was the son of Mustafa Celalettin Pasha a Polish convert to Islam, who fled to the Ottoman Empire after a failed Polish uprising agains ...

(no relation to the Young Turk leader) to China in 1901, but the rebellion was over by that time. Because the Ottomans did not want conflict with the European nations and because the Ottoman Empire was ingratiating itself to gain German assistance, an order imploring Chinese Muslims to avoid assisting the Boxers was issued by the Ottoman Khalifa and reprinted in Egyptian and Muslim Indian newspapers.

Opposition

Abdul Hamid II made many enemies in the Ottoman Empire. His reign featured several coup d'état plans and many rebellions. The Sultan triumphed in a challenge byKâmil Pasha

Mehmed Kâmil Pasha (; , "Mehmed Kâmil Pasha the Cypriot"), also spelled as Kâmil Pasha (1833 – 14 November 1913), was an Ottoman Anglophile statesman and liberal politician of Turkish Cypriot origin in the late-19th-century and early-20th ...

of absolute rule in 1895. A large conspiracy by the Committee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

was also foiled in 1896

Events

January

* January 2 – The Jameson Raid comes to an end as Jameson surrenders to the Boers.

* January 4 – Utah is admitted as the 45th U.S. state.

* January 5 – An Austrian newspaper reports Wilhelm Röntgen's dis ...

. His ascendancy finally ended in a revolution

In political science, a revolution (, 'a turn around') is a rapid, fundamental transformation of a society's class, state, ethnic or religious structures. According to sociologist Jack Goldstone, all revolutions contain "a common set of elements ...

in 1908, and his reign for good ended with the 31 March Incident

The 31 March incident () was an uprising in the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. The incident broke out during the night of 30–31 Mart 1325 in Rumi calendar ( GC 12–13 April 1909), thus named after 31 Mar ...

. These conspiracies were primarily driven by members of inside the Ottoman government, due to dissatisfaction with autocracy. Journalists had to contend with a strict censorship regime, while the intelligentsia chafed under the surveillance of intelligence agencies. It was in this context that a broad opposition movement to the sultan emerged, known as the Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

to European observers. Most Young Turks were ambitious military officers, constitutionalists, and bureaucrats of the Sublime Porte

The Sublime Porte, also known as the Ottoman Porte or High Porte ( or ''Babıali''; ), was a synecdoche or metaphor used to refer collectively to the central government of the Ottoman Empire in Istanbul. It is particularly referred to the buildi ...

.

With state policy fostering an Islamist Ottomanism, Christian minority groups also began to turn against the government, going so far as to advocate for separatism. By the 1890s, Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian, and Aromanian militant groups started fighting Ottoman authorities, and each other, in the Macedonian conflict. Using the '' İdare-i Örfiyye'', a clause in the defunct Ottoman constitution comparable to declaring a state of siege

''State of Siege'' () is a 1972 French–Italian–West German political thriller film directed by Costa-Gavras starring Yves Montand and Renato Salvatori. The story is based on an actual incident in 1970, when U.S. official Dan Mitrione was k ...

, the government suspended civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

in the Ottoman Balkans. ''İdare-i Örfiyye'' was also soon declared in Eastern Anatolia

The Eastern Anatolia region () is a geographical region of Turkey. The most populous province in the region is Van Province. Other populous provinces are Malatya, Erzurum and Elazığ.

It is bordered by the Black Sea Region and Georgia in th ...

to more effectively prosecute fedayi. The statute persisted under the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey until the 1940s.

Educated Muslim women resented the Salafist

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a fundamentalist revival movement within Sunni Islam, originating in the late 19th century and influential in the Islamic world to this day. The name "''Salafiyya''" is a self-designation, claiming a retur ...

'' Hatts'' that mandated veils be worn outside the home and to be accompanied by men, though these decrees were mostly ignored.

Young Turk Revolution

The national humiliation of the Macedonian conflict, together with the resentment in the army against the palace spies and informers, at last brought matters to a crisis. TheCommittee of Union and Progress

The Ottoman Committee of Union and Progress (CUP, also translated as the Society of Union and Progress; , French language, French: ''Union et Progrès'') was a revolutionary group, secret society, and political party, active between 1889 and 1926 ...

(CUP), a Young Turks

The Young Turks (, also ''Genç Türkler'') formed as a constitutionalist broad opposition-movement in the late Ottoman Empire against the absolutist régime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II (). The most powerful organization of the movement, ...

organization that was especially influential in the Rumelian army units, undertook the Young Turk Revolution

The Young Turk Revolution (July 1908; ) was a constitutionalist revolution in the Ottoman Empire. Revolutionaries belonging to the Internal Committee of Union and Progress, an organization of the Young Turks movement, forced Sultan Abdul Hamid II ...

in the summer of 1908. Upon learning that the troops in Salonica

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

were marching on Istanbul (23 July), Abdul Hamid capitulated. On 24 July an ''irade'' announced the restoration of the suspended constitution of 1876

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

; the next day, further ''irades'' abolished espionage and censorship, and ordered the release of political prisoners.

On 17 December, Abdul Hamid reopened the General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

with a speech from the throne

A speech from the throne, or throne speech, is an event in certain monarchies in which the reigning sovereign, or their representative, reads a prepared speech to members of the nation's legislature when a Legislative session, session is opened. ...

in which he said that the first parliament had been "temporarily dissolved until the education of the people had been brought to a sufficiently high level by the extension of instruction throughout the empire."

Deposition

Abdul Hamid's new attitude did not save him from the suspicion of intriguing with the state's powerful reactionary elements, a suspicion confirmed by his attitude toward the counter-revolution of 13 April 1909, known as the31 March Incident

The 31 March incident () was an uprising in the Ottoman Empire in April 1909, during the Second Constitutional Era. The incident broke out during the night of 30–31 Mart 1325 in Rumi calendar ( GC 12–13 April 1909), thus named after 31 Mar ...

, when an insurrection of the soldiers backed by a conservative upheaval in some parts of the military in the capital overthrew Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha

Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha ( , also spelled Hussein Hilmi Pasha) (1 April 1855 – 1922) was an Ottoman statesman and imperial administrator. He was twice the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire around the time of the Second Constitutional Era. He wa ...

's government. With the Young Turks driven out of the capital, Abdul Hamid appointed Ahmet Tevfik Pasha

Ahmet Tevfik Pasha (; 11 February 1843 – 8 October 1936), later Ahmet Tevfik Okday after the Turkish Surname Law of 1934, was an Ottoman diplomat and statesman of Crimean Tatar origin. He was the last grand vizier of the Ottoman Empir ...

in his place, and once again suspended the constitution and shuttered the parliament. But the Sultan controlled only Constantinople, while the Unionists were still influential in the rest of the army and provinces. The CUP appealed to Mahmud Şevket Pasha to restore the status quo. Şevket Pasha organized an ''ad hoc'' formation known as the Action Army, which marched on Constantinople. Şevket Pasha's chief of staff was captain Mustafa Kemal

Mustafa () is one of the names of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and the name means "chosen, selected, appointed, preferred", used as an Arabic given name and surname. Mustafa is a common name in the Muslim world.

Given name Moustafa

* Moustafa A ...

. The Action Army stopped first in Aya Stefanos, and negotiated with the rival government established by deputies who escaped from the capital, which was led by Mehmed Talat

Mehmed Talât (1 September 187415 March 1921), commonly known as Talaat Pasha or Talat Pasha, was an Ottoman Young Turks, Young Turk activist, revolutionary, politician, and Ottoman Special Military Tribunal, convicted war criminal who served ...

. It was secretly decided there that Abdul Hamid must be deposed. When the Action Army entered Istanbul, a ''fatwa'' was issued condemning Abdul Hamid, and the parliament voted to dethrone him. On 27 April, Abdul Hamid's half-brother Reshad Efendi was proclaimed as Sultan Mehmed V

Mehmed V Reşâd (; or ; 2 November 1844 – 3 July 1918) was the penultimate List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1909 to 1918. Mehmed V reigned as a Constitutional monarchy, constitutional monarch. He had ...

.

The Sultan's countercoup, which had appealed to conservative Islamists against the Young Turks' liberal reforms, resulted in the massacre of tens of thousands of Christian Armenians in the Adana province, known as the Adana massacre

The Adana massacres (, ) occurred in the Adana Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire in April 1909. Many Armenians were slain by Ottoman Muslims in the city of Adana as the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 triggered a series of pogroms throughout the prov ...

.

After deposition

Thessaloniki

Thessaloniki (; ), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, Salonika, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece (with slightly over one million inhabitants in its Thessaloniki metropolitan area, metropolitan area) and the capital cit ...

), mostly at the Villa Allatini in the city's southern outskirts. In 1912, when Salonica fell to Greece, he was returned to captivity in Constantinople. He spent his last days studying, practicing carpentry, and writing his memoirs in custody at Beylerbeyi Palace

The Beylerbeyi Palace () is a 19th-century Ottoman palace located in the Beylerbeyi neighborhood of Istanbul’s Üsküdar district, on the Asian shore of the Bosporus. Commissioned by Sultan Abdulaziz and completed between 1861 and 1865, the ...

in the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

, in the company of his wives and children. He died there in 1918.

In 1930, his nine widows and thirteen children were granted $50 million from his estate after a lawsuit that lasted five years. His estate was worth $1.5 billion.

Abdul Hamid was the last sultan of the Ottoman Empire to hold absolute power. He presided over 33 years of decline, during which other European countries regarded the empire as the "sick man of Europe

"Sick man of Europe" is a label given to a state located in Europe that is experiencing economic difficulties, social unrest or impoverishment. It is most famously used to refer to the Ottoman Empire (predecessor of present-day Turkey) whilst it w ...

".

Personal life

Abdul Hamid II was a skilled carpenter and personally crafted some high-quality furniture, which can be seen at the

Abdul Hamid II was a skilled carpenter and personally crafted some high-quality furniture, which can be seen at the Yıldız Palace

Yıldız Palace (, ) is a vast complex of former imperial Ottoman Empire, Ottoman pavilions and villas in Beşiktaş, Istanbul, Turkey, built in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It was used as a residence by the List of sultans of the Ottoman ...

, Şale Köşkü, and Beylerbeyi Palace

The Beylerbeyi Palace () is a 19th-century Ottoman palace located in the Beylerbeyi neighborhood of Istanbul’s Üsküdar district, on the Asian shore of the Bosporus. Commissioned by Sultan Abdulaziz and completed between 1861 and 1865, the ...

in Istanbul. He was also interested in opera and personally wrote the first-ever Turkish translations of many classic operas. He also composed several opera pieces for the ''Mızıka-yı Hümâyun'' (Ottoman Imperial Band/Orchestra, established by his grandfather Mahmud II

Mahmud II (, ; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839. Often described as the "Peter the Great of Turkey", Mahmud instituted extensive administrative, military, and fiscal reforms ...

who had appointed Donizetti Pasha as its Instructor General in 1828), and hosted the famous performers of Europe at the Opera House of Yıldız Palace, which was restored in the 1990s and featured in the 1999 film ''Harem Suare

''Harem Suare'' is a 1999 Turkish drama film directed by Ferzan Özpetek. It was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival.

Plot

The old Safiye is telling a young woman the life that she lived during the early ...

'' (it begins with a scene of Abdul Hamid watching a performance). One of his guests was the French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt

Sarah Bernhardt (; born Henriette-Rosine Bernard; 22 October 1844 – 26 March 1923) was a French stage actress who starred in some of the most popular French plays of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including by Alexandre Dumas fils, ...

, who performed for audiences.

Abdul Hamid was also a good wrestler at Yağlı güreş

Oil wrestling (), also called Turkish oil wrestling, is the national sport of Turkey. Oil wrestling includes oil and traditional dress, and its rules are comparable to karakucak.

In Assyria, ancient Egypt, and Babylonia, oil wrestling was perfo ...