Strategic Bombing In World War II on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Ethics of Bombing

''The Royal Air Force Quarterly'', No. 2, Summer 1967 Three separate lines of ethical reasoning emerged.Johnson, James Turner

Bombing, Ethics of

In Chambers, John Whiteclay

''The Oxford Companion to American Military History''

New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. The first was based on the

p 74.

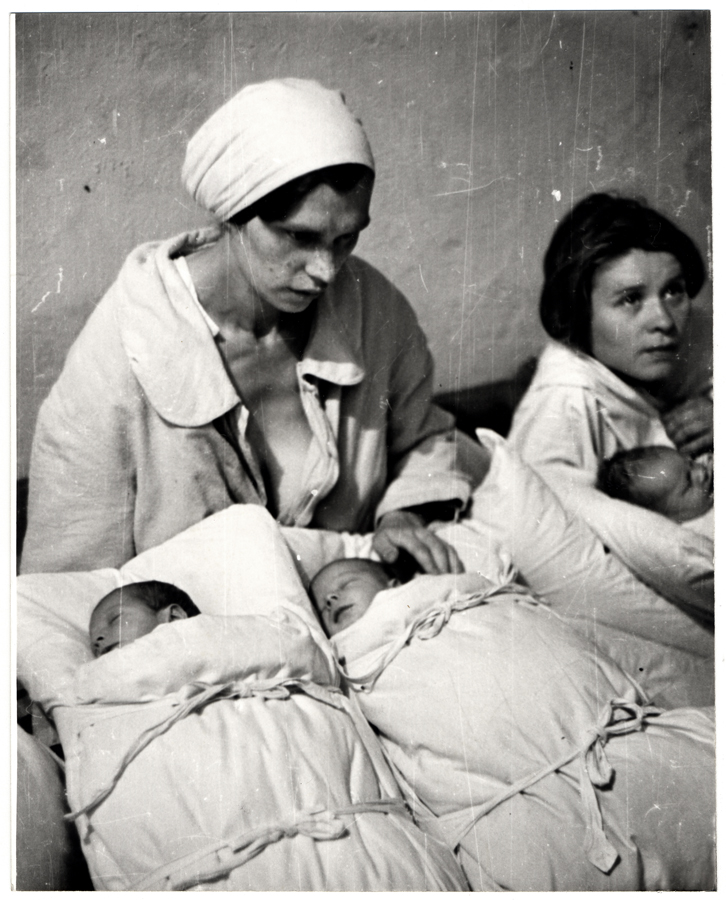

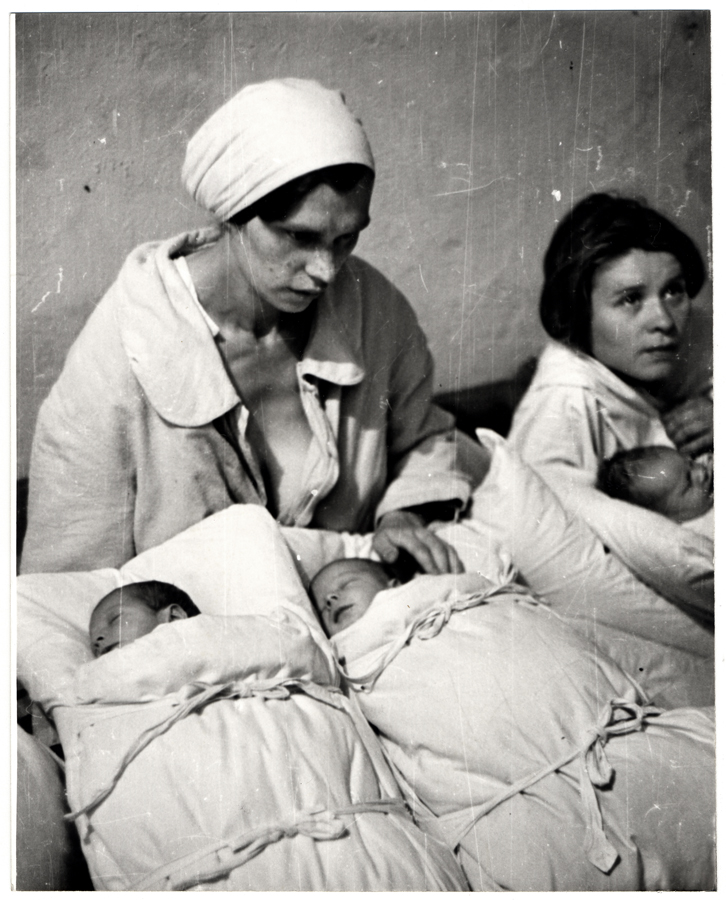

/ref> bombing civilian infrastructure such as hospitalsSylwia Słomińska

, Z dziejów dawnego Wielunia "History of old Wielun", site by Dr Tadeusz Grabarczyk, Historical Institute at University of Lodz, and targeting fleeing refugees.Norman Davies. (1982). ''God's Playground: A History of Poland'', Columbia University Press

p 437.

/ref> Notably, the ''Luftwaffe'' bombed the Polish capital of Warsaw, and the small towns Preparations were made for a concentrated attack (Operation Wasserkante) by all bomber forces against targets in Warsaw. However, the operation was cancelled, according to Polish professor

Preparations were made for a concentrated attack (Operation Wasserkante) by all bomber forces against targets in Warsaw. However, the operation was cancelled, according to Polish professor

p 1613.

/ref> On 14 September, the French

''Hamburger Abendblatt'' Railway yards at Cologne were attacked on the same night. During May,

On 6 August Göring finalised plans for "Operation Eagle Attack" with his commanders: destruction of RAF Fighter Command across the south of England was to take four days, then bombing of military and economic targets was to systematically extend up to the Midlands until daylight attacks could proceed unhindered over the whole of Britain, then a major attack was to be made on London causing a crisis with refugees when the intended

On 6 August Göring finalised plans for "Operation Eagle Attack" with his commanders: destruction of RAF Fighter Command across the south of England was to take four days, then bombing of military and economic targets was to systematically extend up to the Midlands until daylight attacks could proceed unhindered over the whole of Britain, then a major attack was to be made on London causing a crisis with refugees when the intended

Goering's first chief of staff, ''Generalleutnant'' Walther Wever, was a big advocate of the Ural bomber program, but when he died in a flying accident in 1936, support for the strategic bomber program began to dwindle rapidly under Goering's influence. Under pressure from Goering, Albert Kesselring, Wever's replacement, opted for a medium, all-purpose, twin-engine tactical bomber.

Goering's first chief of staff, ''Generalleutnant'' Walther Wever, was a big advocate of the Ural bomber program, but when he died in a flying accident in 1936, support for the strategic bomber program began to dwindle rapidly under Goering's influence. Under pressure from Goering, Albert Kesselring, Wever's replacement, opted for a medium, all-purpose, twin-engine tactical bomber.  The only heavy bomber design to see service with the ''Luftwaffe'' in World War II was the trouble-prone

The only heavy bomber design to see service with the ''Luftwaffe'' in World War II was the trouble-prone

Lindemann was liked and trusted by

Lindemann was liked and trusted by  On 14 February 1942, the

On 14 February 1942, the  At this stage of the air war, the most effective and disruptive examples of area bombing were the "thousand-bomber raids". Bomber Command was able by organization and drafting in as many aircraft as possible to assemble very large forces which could then attack a single area, overwhelming the defences. The aircraft would be staggered so that they would arrive over the target in succession: the new technique of the "bomber stream".

On 30 May 1942, between 0047 and 0225 hours, in

At this stage of the air war, the most effective and disruptive examples of area bombing were the "thousand-bomber raids". Bomber Command was able by organization and drafting in as many aircraft as possible to assemble very large forces which could then attack a single area, overwhelming the defences. The aircraft would be staggered so that they would arrive over the target in succession: the new technique of the "bomber stream".

On 30 May 1942, between 0047 and 0225 hours, in

''Adevărul'', 22 February 2011. Retrieved 20 June 2018. In all, the bombardments killed some 7,693 civilians and wounded another 7,809. After the 23 August 1944 coup, the Luftwaffe began bombing Bucharest in the attempt to remove the King and Government from power. The raids lasted from 24 to 26 August and killed or wounded over 300 civilians and damaged many buildings.

Italy, first as an Axis member and later as a German-occupied country, was heavily bombed by Allied forces for all the duration of the war. In

Italy, first as an Axis member and later as a German-occupied country, was heavily bombed by Allied forces for all the duration of the war. In

German-occupied France contained a number of important targets that attracted the attention of the British, and later American bombing. In 1940, RAF Bomber Command launched attacks against German preparations for Operation Sealion, the proposed invasion of England, attacking Channel Ports in France and Belgium and sinking large numbers of barges that had been collected by the Germans for use in the invasion.Richards 1995, pp. 84–87. France's Atlantic ports were important bases for both German surface ships and submarines, while French industry was an important contributor to the German war effort."The Bombing of France 1940–1945 Exhibition"

German-occupied France contained a number of important targets that attracted the attention of the British, and later American bombing. In 1940, RAF Bomber Command launched attacks against German preparations for Operation Sealion, the proposed invasion of England, attacking Channel Ports in France and Belgium and sinking large numbers of barges that had been collected by the Germans for use in the invasion.Richards 1995, pp. 84–87. France's Atlantic ports were important bases for both German surface ships and submarines, while French industry was an important contributor to the German war effort."The Bombing of France 1940–1945 Exhibition"

Bombing, States and Peoples in Western Europe, 1940–1945. ''University of Exeter Centre for the Study of War, State and Society''. Retrieved 15 July 2012. Before 1944, the Allies bombed targets in France that were part of the German war industry. This included raids such as those on the Renault factory in Boulogne-Billancourt in March 1942 or the port facilities of Nantes in September 1943 (which killed 1,500 civilians). In preparation of Allied Invasion of Normandy, landings in Normandy and Operation Dragoon, those in the south of France, French infrastructure (mainly rail transport) was intensively targeted by RAF and USAAF in May and June 1944. Despite intelligence provided by the French Resistance, many residential areas were hit in error or lack of accuracy. This included cities like Marseille (2,000 dead), Lyon (1,000 dead), Saint-Étienne, Rouen, Orléans, Grenoble, Nice, Paris and surrounds (1000+ dead), and so on. The Free French Air Force, operational since 1941, used to opt for the more risky skimming tactic when operating in national territory, to avoid civilian casualties. On 5 January 1945, British bombers struck the "Atlantic pocket" of Royan and destroyed 85% of this city. A later raid, using napalm was carried out before it was freed from Nazi occupation in April. Of the 3,000 civilians left in the city, 442 died. French civilian casualties due to Allied strategic bombing are estimated at half of the 67,000 French civilian dead during Allied operations in 1942–1945; the other part being mostly killed during tactical bombing in the Normandy campaign. 22% of the bombs dropped in Europe by British and American air forces between 1940 and 1945 were in France.Eddy Florentin, "Quand les alliés bombardaient la France, 1940–1945", Perrin, Paris, 2008. The port city of Le Havre had been destroyed by 132 bombings during the war (5,000 dead) until September 1944. It has been rebuilt by architect Auguste Perret and is now a World Heritage Site.

Although designed to "break the enemy's will", the opposite often happened. The British did not crumble under the German Blitz and other air raids early in the war. British workers continued to work throughout the war and food and other basic supplies were available throughout.

The impact of bombing on German morale was significant according to Professor John Buckley (historian), John Buckley. Around a third of the urban population under threat of bombing had no protection at all. Some of the major cities saw 55–60 percent of dwellings destroyed. Mass evacuations were a partial answer for six million civilians, but this had a severe effect on morale as German families were split up to live in difficult conditions. By 1944, absenteeism rates of 20–25 percent were not unusual and in post-war analysis 91 percent of civilians stated bombing was the most difficult hardship to endure and was the key factor in the collapse of their own morale.Buckley 1998, p. 166. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that the bombing was not stiffening morale but seriously depressing it; fatalism, apathy, defeatism were apparent in bombed areas. The ''Luftwaffe'' was blamed for not warding off the attacks and confidence in the Nazi regime fell by 14 percent. By the spring of 1944, some 75 percent of Germans believed the war was lost, owing to the intensity of the bombing.

Buckley argues the German war economy did indeed expand significantly following Albert Speer's appointment as Reichsminister of Armaments, "but it is spurious to argue that because production increased then bombing had no real impact". The bombing offensive did do serious damage to German production levels. German tank and aircraft production, though reached new records in production levels in 1944, was in particular one-third lower than planned.Buckley 1998, p. 165. In fact, German aircraft production for 1945 was planned at 80,000, showing Erhard Milch and other leading German planners were pushing for even higher outputs; "unhindered by Allied bombing German production would have risen far higher".Murray 1983, p. 253.

Journalist Max Hastings and the authors of the official history of the bomber offensive, Noble Frankland among them, has argued bombing had a limited effect on morale. In the words of the British Bombing Survey Unit (BBSU), "The essential premise behind the policy of treating towns as unit targets for area attack, namely that the German economic system was fully extended, was false." This, the BBSU noted, was because official estimates of German war production were "more than 100 percent in excess of the true figures". The BBSU concluded, "Far from there being any evidence of a cumulative effect on (German) war production, it is evident that, as the (bombing) offensive progressed ... the effect on war production became progressively smaller (and) did not reach significant dimensions."

Although designed to "break the enemy's will", the opposite often happened. The British did not crumble under the German Blitz and other air raids early in the war. British workers continued to work throughout the war and food and other basic supplies were available throughout.

The impact of bombing on German morale was significant according to Professor John Buckley (historian), John Buckley. Around a third of the urban population under threat of bombing had no protection at all. Some of the major cities saw 55–60 percent of dwellings destroyed. Mass evacuations were a partial answer for six million civilians, but this had a severe effect on morale as German families were split up to live in difficult conditions. By 1944, absenteeism rates of 20–25 percent were not unusual and in post-war analysis 91 percent of civilians stated bombing was the most difficult hardship to endure and was the key factor in the collapse of their own morale.Buckley 1998, p. 166. The United States Strategic Bombing Survey concluded that the bombing was not stiffening morale but seriously depressing it; fatalism, apathy, defeatism were apparent in bombed areas. The ''Luftwaffe'' was blamed for not warding off the attacks and confidence in the Nazi regime fell by 14 percent. By the spring of 1944, some 75 percent of Germans believed the war was lost, owing to the intensity of the bombing.

Buckley argues the German war economy did indeed expand significantly following Albert Speer's appointment as Reichsminister of Armaments, "but it is spurious to argue that because production increased then bombing had no real impact". The bombing offensive did do serious damage to German production levels. German tank and aircraft production, though reached new records in production levels in 1944, was in particular one-third lower than planned.Buckley 1998, p. 165. In fact, German aircraft production for 1945 was planned at 80,000, showing Erhard Milch and other leading German planners were pushing for even higher outputs; "unhindered by Allied bombing German production would have risen far higher".Murray 1983, p. 253.

Journalist Max Hastings and the authors of the official history of the bomber offensive, Noble Frankland among them, has argued bombing had a limited effect on morale. In the words of the British Bombing Survey Unit (BBSU), "The essential premise behind the policy of treating towns as unit targets for area attack, namely that the German economic system was fully extended, was false." This, the BBSU noted, was because official estimates of German war production were "more than 100 percent in excess of the true figures". The BBSU concluded, "Far from there being any evidence of a cumulative effect on (German) war production, it is evident that, as the (bombing) offensive progressed ... the effect on war production became progressively smaller (and) did not reach significant dimensions."

Hamburg, Juli 1943

in ''Der Spiegel'' SPIEGEL ONLINE 2003 (in German) * Matthew White

Twentieth Century Atlas – Death Tolls

' lists the following totals and sources: * more than 305,000: (1945 Strategic Bombing Survey); * 400,000: ''Hammond Atlas of the 20th century'' (1996) * 410,000: R. J. Rummel, 100% Democide, democidal; * 499,750: Micheal Clodfelter ''Warfare and Armed Conflict: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618–1991''; * 593,000: John Keegan ''The Second World War'' (1989); * 593,000: J. A. S. Grenville citing "official Germany" in ''A History of the World in the Twentieth Century (1994)'' * 600,000: Paul Johnson (writer), Paul Johnson ''Modern Times'' (1983) In the United Kingdom, 60,595 Britons were killed by German bombing, and in France, 67,078 French people were killed by Allied bombing raids. * 60,000, John Keegan ''The Second World War'' (1989); "bombing" * 60,000: Boris Urlanis, ''Wars and Population'' (1971) * 60,595: Harper Collins Atlas of the Second World War * 60,600: John Ellis, World War II: a statistical survey (Facts on File, 1993) "killed and missing" * 92,673, (incl. 30,248 merchant mariners and 60,595 killed by bombing): ''Encyclopædia Britannica'', 15th edition, 1992 printing. "Killed, died of wounds, or in prison .... exclud[ing] those who died of natural causes or were suicides." * 92,673: Norman Davies,''Europe A History'' (1998) same as Britannica's war dead in most cases * 92,673: Micheal Clodfelter ''Warfare and Armed Conflict: A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1618–1991''; * 100,000: William Eckhardt, a three-page table of his war statistics printed in ''World Military and Social Expenditures 1987–88'' (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard. "Deaths", including "massacres, political violence, and famines associated with the conflicts." The British kept accurate records during World War II, and 60,595 people killed was the official death total with 30,248 for the British merchant mariners (most of whom are listed on the Tower Hill Memorial)Olivier Wieviorka, "Normandy: the landings to the liberation of Paris" p.131 Belgrade was heavily bombed by the Luftwaffe on 6 April 1941, when more than 17,000 people were killed. According to ''The Oxford companion to World War II'', "After Italy's surrender the Allies kept up the bombing of the northern part occupied by the Germans and more than 50,000 Italians were killed in these raids."Ian Dear, Michael Richard Daniell Foot (2001).

The Oxford companion to World War II

'. Oxford University Press. p. 837. An National Institute of Statistics (Italy), Istat study of 1957 stated that 64,354 Italians were killed by aerial bombing, 59,796 of whom were civilians. Historians Marco Gioannini and Giulio Massobrio argued in 2007 that this figure is inaccurate due to loss of documents, confusion and gaps, and estimated the total number of civilian casualties in Italy due to aerial bombing as comprised between 80,000 and 100,000. Over 160,000 Allied airmen and 33,700 planes were lost in the European theatre of World War II, European theatre.

The first U.S. raid on the Japanese main island was the Doolittle Raid of 18 April 1942, when sixteen B-25 Mitchells were launched from the to attack targets including Yokohama and Tokyo and then fly on to airfields in China. The raid was a military pinprick but a significant propaganda victory. Because they were launched prematurely, none of the aircraft had enough fuel to reach their designated landing sites, and so either crashed or ditched (except for one aircraft, which landed in the Soviet Union, where the crew was interned). Two crews were captured by the Japanese.

The key development for the bombing of Japan was the B-29 Superfortress, which had an operational range of 1,500 miles (2,400 km); almost 90% of the bombs (147,000 tons) dropped on the home islands of Japan were delivered by this bomber. The Bombing of Yawata (June 1944), first raid by B-29s on Japan was on 15 June 1944, from China. The B-29s took off from Chengdu, over 1,500 miles away. This raid was also not particularly effective: only forty-seven of the sixty-eight bombers hit the target area.

The first U.S. raid on the Japanese main island was the Doolittle Raid of 18 April 1942, when sixteen B-25 Mitchells were launched from the to attack targets including Yokohama and Tokyo and then fly on to airfields in China. The raid was a military pinprick but a significant propaganda victory. Because they were launched prematurely, none of the aircraft had enough fuel to reach their designated landing sites, and so either crashed or ditched (except for one aircraft, which landed in the Soviet Union, where the crew was interned). Two crews were captured by the Japanese.

The key development for the bombing of Japan was the B-29 Superfortress, which had an operational range of 1,500 miles (2,400 km); almost 90% of the bombs (147,000 tons) dropped on the home islands of Japan were delivered by this bomber. The Bombing of Yawata (June 1944), first raid by B-29s on Japan was on 15 June 1944, from China. The B-29s took off from Chengdu, over 1,500 miles away. This raid was also not particularly effective: only forty-seven of the sixty-eight bombers hit the target area.

Raids of Japan from mainland China, called Operation Matterhorn, were carried out by the Twentieth Air Force under XX Bomber Command. Initially the commanding officer of the Twentieth Air Force was Hap Arnold, and later Curtis LeMay. Bombing Japan from China was never a satisfactory arrangement because not only were the Chinese airbases difficult to supply—materiel being sent by air from India over "the Hump"—but the B-29s operating from them could only reach Japan if they traded some of their bomb load for extra fuel in tanks in the bomb-bays. When Admiral Chester Nimitz's Leapfrogging (strategy), island-hopping campaign captured Pacific islands close enough to Japan to be within the B-29's range, the Twentieth Air Force was assigned to XXI Bomber Command, which organized a much more effective bombing campaign of the Japanese home islands. Based in the Mariana Islands, Marianas (Guam and Tinian in particular), the B-29s were able to carry their full bomb loads and were supplied by cargo ships and tankers. The first raid from the Mariana was on 24 November 1944, when 88 aircraft bombed Tokyo. The bombs were dropped from around 30,000 feet (10,000 m) and it is estimated that only around 10% hit their targets.

Raids of Japan from mainland China, called Operation Matterhorn, were carried out by the Twentieth Air Force under XX Bomber Command. Initially the commanding officer of the Twentieth Air Force was Hap Arnold, and later Curtis LeMay. Bombing Japan from China was never a satisfactory arrangement because not only were the Chinese airbases difficult to supply—materiel being sent by air from India over "the Hump"—but the B-29s operating from them could only reach Japan if they traded some of their bomb load for extra fuel in tanks in the bomb-bays. When Admiral Chester Nimitz's Leapfrogging (strategy), island-hopping campaign captured Pacific islands close enough to Japan to be within the B-29's range, the Twentieth Air Force was assigned to XXI Bomber Command, which organized a much more effective bombing campaign of the Japanese home islands. Based in the Mariana Islands, Marianas (Guam and Tinian in particular), the B-29s were able to carry their full bomb loads and were supplied by cargo ships and tankers. The first raid from the Mariana was on 24 November 1944, when 88 aircraft bombed Tokyo. The bombs were dropped from around 30,000 feet (10,000 m) and it is estimated that only around 10% hit their targets.

Unlike all other forces in theater, the Bomber Command#USAAF, USAAF Bomber Commands did not report to the commanders of the theaters but directly to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In July 1945, they were placed under the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, which was commanded by Carl Spaatz.

As in Europe, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) tried daylight precision bombing. However, it proved to be impossible due to the weather around Japan, "during the best month for bombing in Japan, visual bombing was possible for [just] seven days. The worst had only one good day." Further, bombs dropped from a great height were tossed about by high winds.

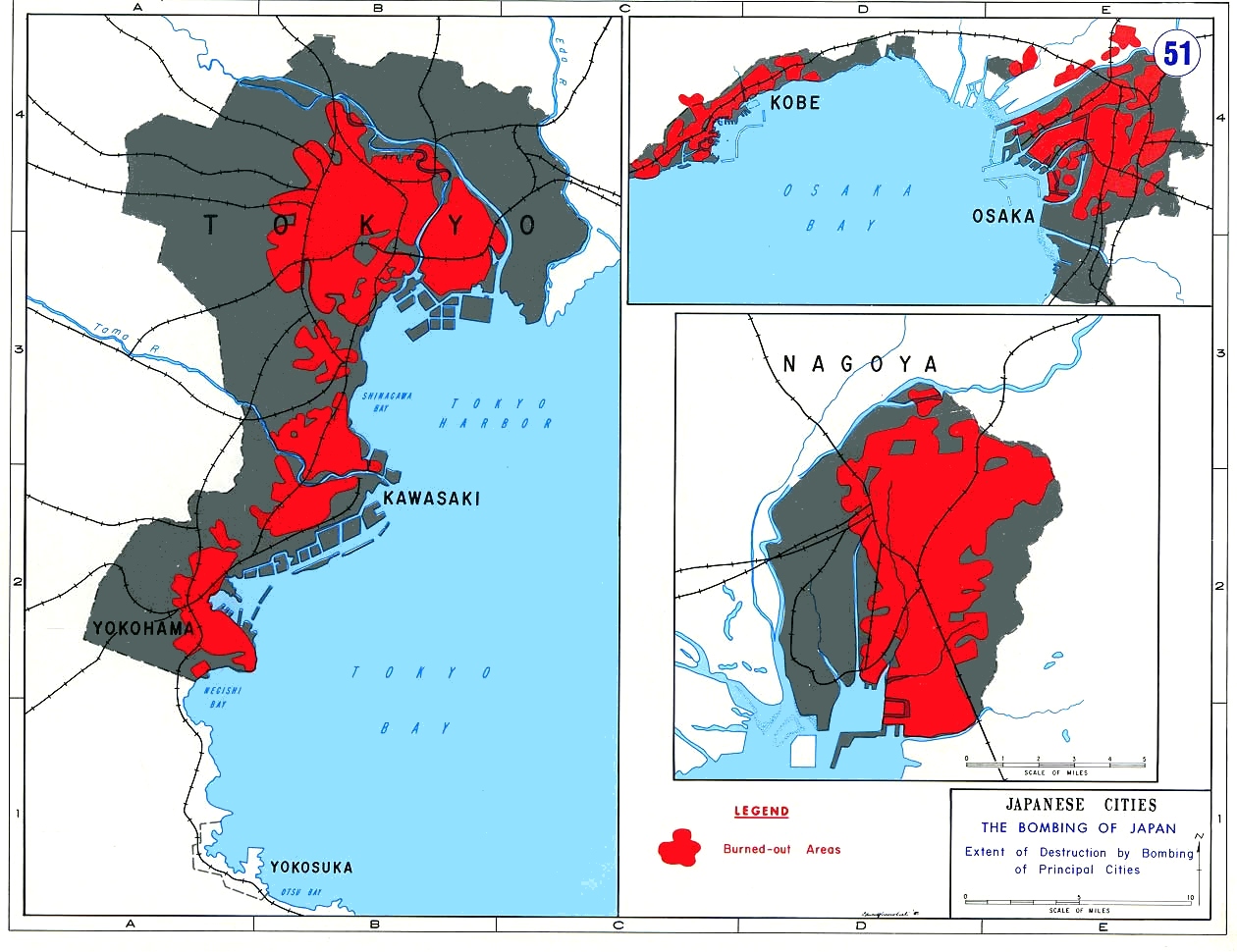

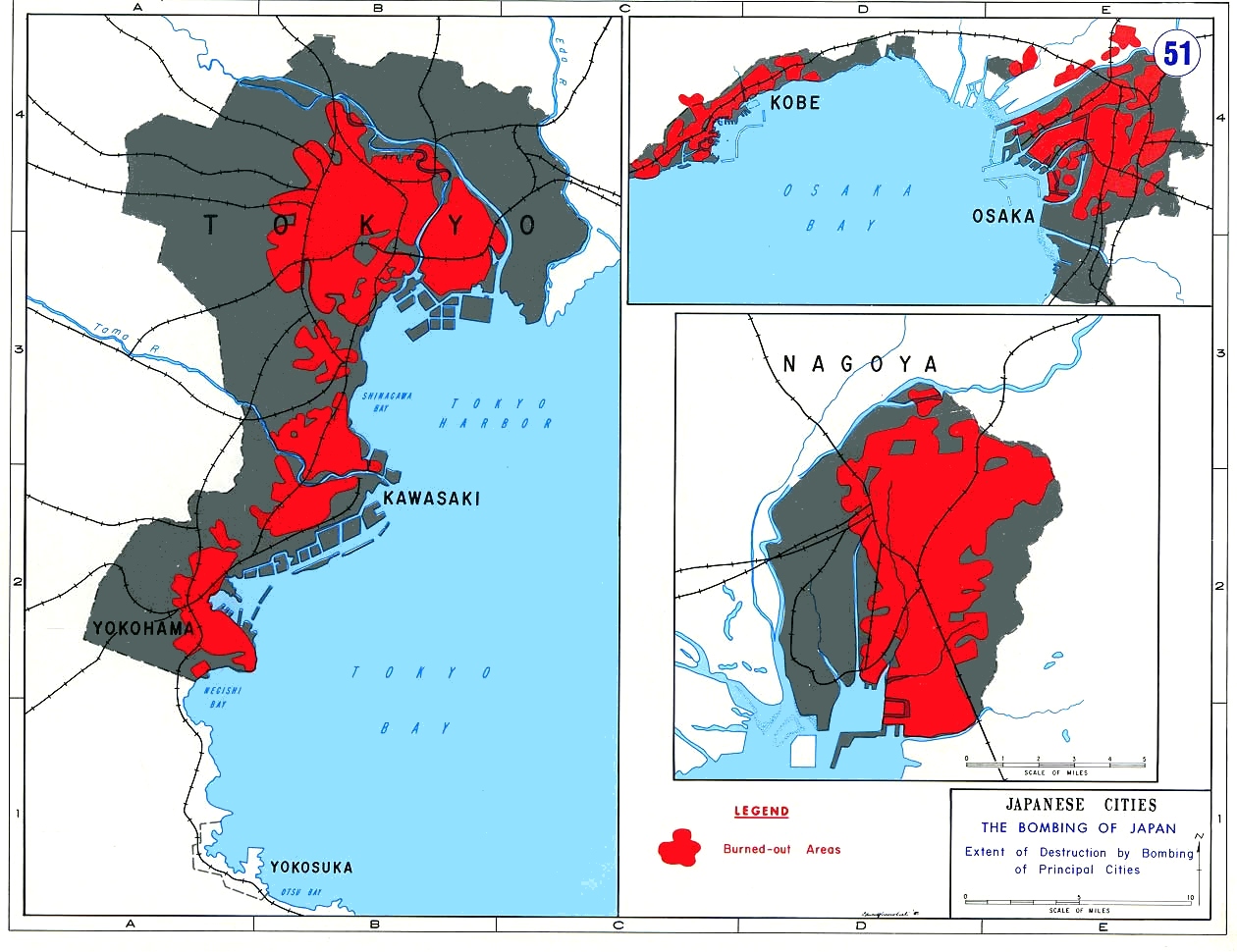

General LeMay, commander of XXI Bomber Command, instead switched to mass firebombing night attacks from altitudes of around 7,000 feet (2,100 m) on the major conurbations. "He looked up the size of the large Japanese cities in the ''World Almanac'' and picked his targets accordingly." Priority targets were Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. Despite limited early success, particularly against Nagoya, LeMay was determined to use such bombing tactics against the vulnerable Japanese cities. Attacks on strategic targets also continued in lower-level daylight raids.

The first successful firebombing raid was Bombing of Kobe in World War II, on Kobe on 3 February 1945, and following its relative success the USAAF continued the tactic. Nearly half of the principal factories of the city were damaged, and production was reduced by more than half at one of the port's two shipyards.

Bombing of Tokyo in World War II, The first raid of this type on Tokyo was on the night of 23–24 February when 174 B-29s destroyed around one square mile (3 km2) of the city. Following on that success, as Bombing of Tokyo (10 March 1945), Operation Meetinghouse, 334 B-29s raided on the night of 9–10 March, of which 282 Superforts reached their targets, dropping around 1,700 tons of bombs. Around 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city was destroyed and over 100,000 people are estimated to have died in the fire storm. It was the most destructive conventional raid, and the deadliest single bombing raid of any kind in terms of lives lost, in all of military aviation history, even when the missions on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are taken as single events. The city was made primarily of wood and paper, and the fires burned out of control. The effects of the Tokyo firebombing proved the fears expressed by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Yamamoto in 1939: "Japanese cities, being made of wood and paper, would burn very easily. The Army talks big, but if war came and there were large-scale air raids, there's no telling what would happen."Spector, Ronald (1985). "Eagle Against the Sun." New York: Vintage Books. p. 503.

In the following two weeks, there were almost 1,600 further sorties against the four cities, destroying 31 square miles (80 km2) in total at a cost of 22 aircraft. By June, over forty percent of the urban area of Japan's largest six cities (Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, Osaka, Yokohama, and Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Kawasaki) was devastated. LeMay's fleet of nearly 600 bombers destroyed tens of smaller cities and manufacturing centres in the following weeks and months.

Leaflets were dropped over cities before they were bombed, warning the inhabitants and urging them to escape the city. Though many, even within the Air Force, viewed this as a form of psychological warfare, a significant element in the decision to produce and drop them was the desire to assuage American anxieties about the extent of the destruction created by this new war tactic. Warning leaflets were also dropped on cities not in fact targeted, to create uncertainty and absenteeism.

A year after the war, the Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific War), U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported that American military officials had underestimated the power of strategic bombing combined with naval blockade and previous military defeats to bring Japan to unconditional surrender without invasion. By July 1945, only a fraction of the planned strategic bombing force had been deployed yet there were few targets left worth the effort. In hindsight, it would have been more effective to use land-based and carrier-based air power to strike merchant shipping and begin aerial mining at a much earlier date so as to link up with effective Allied submarines in the Pacific War, submarine anti-shipping campaign and completely isolate the island nation. This would have accelerated the strangulation of Japan and perhaps ended the war sooner. A postwar Naval Ordnance Laboratory survey agreed, finding naval mines dropped by B-29s had accounted for 60% of all Japanese shipping losses in the last six months of the war.Hallion, Dr. Richard P

Unlike all other forces in theater, the Bomber Command#USAAF, USAAF Bomber Commands did not report to the commanders of the theaters but directly to the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In July 1945, they were placed under the U.S. Strategic Air Forces in the Pacific, which was commanded by Carl Spaatz.

As in Europe, the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) tried daylight precision bombing. However, it proved to be impossible due to the weather around Japan, "during the best month for bombing in Japan, visual bombing was possible for [just] seven days. The worst had only one good day." Further, bombs dropped from a great height were tossed about by high winds.

General LeMay, commander of XXI Bomber Command, instead switched to mass firebombing night attacks from altitudes of around 7,000 feet (2,100 m) on the major conurbations. "He looked up the size of the large Japanese cities in the ''World Almanac'' and picked his targets accordingly." Priority targets were Tokyo, Nagoya, Osaka, and Kobe. Despite limited early success, particularly against Nagoya, LeMay was determined to use such bombing tactics against the vulnerable Japanese cities. Attacks on strategic targets also continued in lower-level daylight raids.

The first successful firebombing raid was Bombing of Kobe in World War II, on Kobe on 3 February 1945, and following its relative success the USAAF continued the tactic. Nearly half of the principal factories of the city were damaged, and production was reduced by more than half at one of the port's two shipyards.

Bombing of Tokyo in World War II, The first raid of this type on Tokyo was on the night of 23–24 February when 174 B-29s destroyed around one square mile (3 km2) of the city. Following on that success, as Bombing of Tokyo (10 March 1945), Operation Meetinghouse, 334 B-29s raided on the night of 9–10 March, of which 282 Superforts reached their targets, dropping around 1,700 tons of bombs. Around 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city was destroyed and over 100,000 people are estimated to have died in the fire storm. It was the most destructive conventional raid, and the deadliest single bombing raid of any kind in terms of lives lost, in all of military aviation history, even when the missions on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are taken as single events. The city was made primarily of wood and paper, and the fires burned out of control. The effects of the Tokyo firebombing proved the fears expressed by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Yamamoto in 1939: "Japanese cities, being made of wood and paper, would burn very easily. The Army talks big, but if war came and there were large-scale air raids, there's no telling what would happen."Spector, Ronald (1985). "Eagle Against the Sun." New York: Vintage Books. p. 503.

In the following two weeks, there were almost 1,600 further sorties against the four cities, destroying 31 square miles (80 km2) in total at a cost of 22 aircraft. By June, over forty percent of the urban area of Japan's largest six cities (Tokyo, Nagoya, Kobe, Osaka, Yokohama, and Kawasaki, Kanagawa, Kawasaki) was devastated. LeMay's fleet of nearly 600 bombers destroyed tens of smaller cities and manufacturing centres in the following weeks and months.

Leaflets were dropped over cities before they were bombed, warning the inhabitants and urging them to escape the city. Though many, even within the Air Force, viewed this as a form of psychological warfare, a significant element in the decision to produce and drop them was the desire to assuage American anxieties about the extent of the destruction created by this new war tactic. Warning leaflets were also dropped on cities not in fact targeted, to create uncertainty and absenteeism.

A year after the war, the Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific War), U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey reported that American military officials had underestimated the power of strategic bombing combined with naval blockade and previous military defeats to bring Japan to unconditional surrender without invasion. By July 1945, only a fraction of the planned strategic bombing force had been deployed yet there were few targets left worth the effort. In hindsight, it would have been more effective to use land-based and carrier-based air power to strike merchant shipping and begin aerial mining at a much earlier date so as to link up with effective Allied submarines in the Pacific War, submarine anti-shipping campaign and completely isolate the island nation. This would have accelerated the strangulation of Japan and perhaps ended the war sooner. A postwar Naval Ordnance Laboratory survey agreed, finding naval mines dropped by B-29s had accounted for 60% of all Japanese shipping losses in the last six months of the war.Hallion, Dr. Richard P

''Decisive Air Power Prior to 1950''

Air Force History and Museums Program. In October 1945, Prince Fumimaro Konoe said the sinking of Japanese vessels by U.S. aircraft combined with the B-29 aerial mining campaign were just as effective as B-29 attacks on industry alone, though he admitted, "the thing that brought about the determination to make peace was the prolonged bombing by the B-29s." Prime Minister Baron Kantarō Suzuki reported to U.S. military authorities it "seemed to me unavoidable that in the long run Japan would be almost destroyed by air attack so that merely on the basis of the B-29s alone I was convinced that Japan should sue for peace."

While the bombing campaign against Japan continued, the U.S. and its allies were preparing to Operation Downfall, invade the Japanese home islands, which they anticipated to be heavily costly in terms of life and property. On 1 April 1945, U.S. troops Battle of Okinawa, invaded the island of Okinawa and fought there fiercely against not only enemy soldiers, but also enemy civilians. After two and a half months, 12,000 U.S. servicemen, 107,000 Japanese soldiers, and over 150,000 Okinawan civilians (included those forced to fight) were killed. Given the casualty rate in Okinawa, American commanders realized a grisly picture of the intended invasion of mainland Japan. When President Harry S. Truman was briefed on what would happen during an invasion of Japan, he could not afford such a horrendous casualty rate, added to over 400,000 U.S. servicemen who had already died fighting in both the European and Pacific theaters of the war.

Hoping to forestall the invasion, the United States, the United Kingdom, and China issued a Potsdam Declaration on 26 July 1945, demanding that the Japanese government accept an unconditional surrender. The declaration also stated that if Japan did not surrender, it would be faced with "prompt and utter destruction", a process which was already underway with the incendiary bombing raids destroying 40% of targeted cities, and by naval warfare isolating and starving Japan of imported food. The Japanese government ignored (''mokusatsu'') this ultimatum, thus signalling that they were not going to surrender.

In the wake of this rejection, Stimson and George Marshall (the Army chief of staff) and Hap Arnold (head of the Army Air Forces) set the atomic bombing in motion.

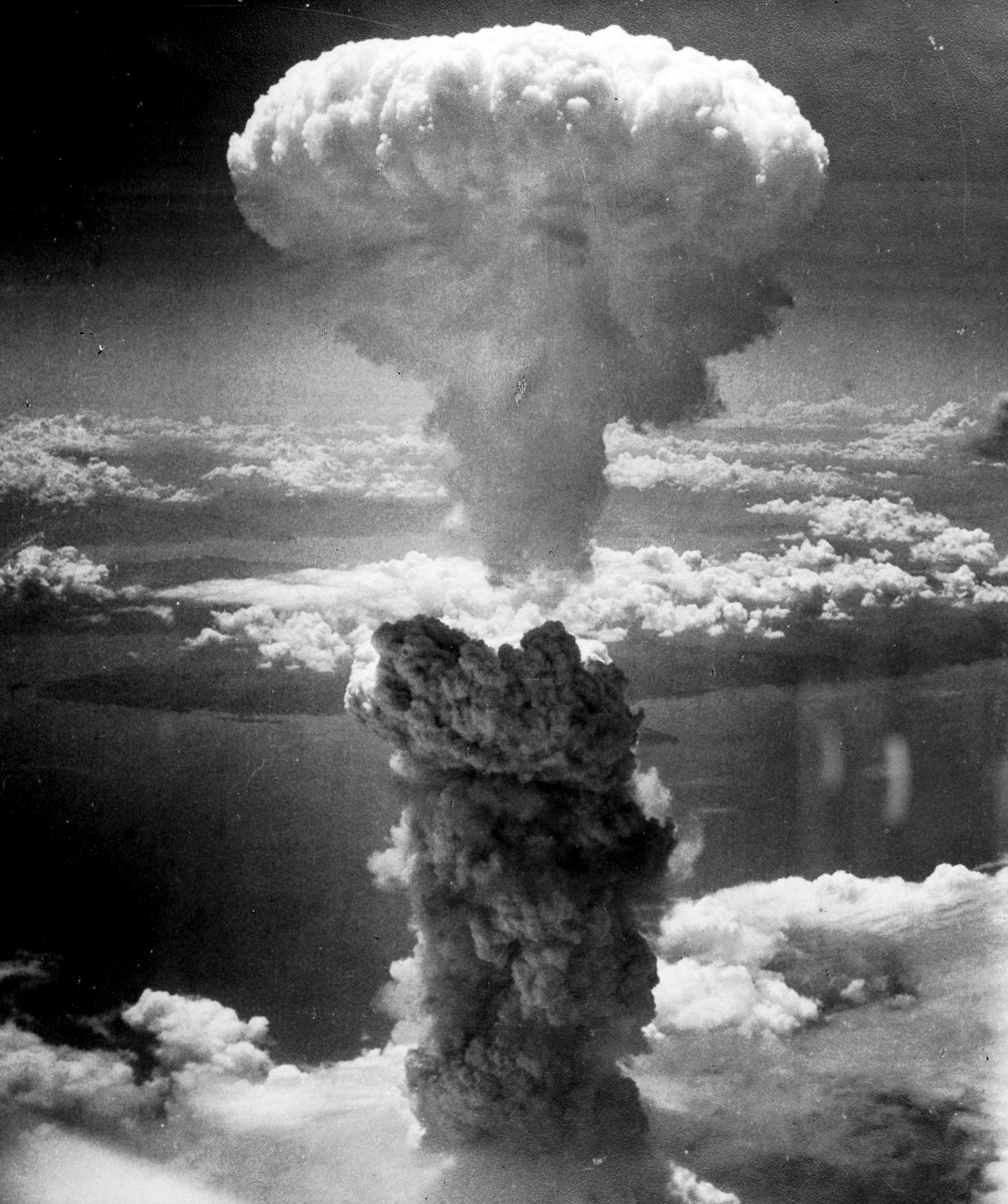

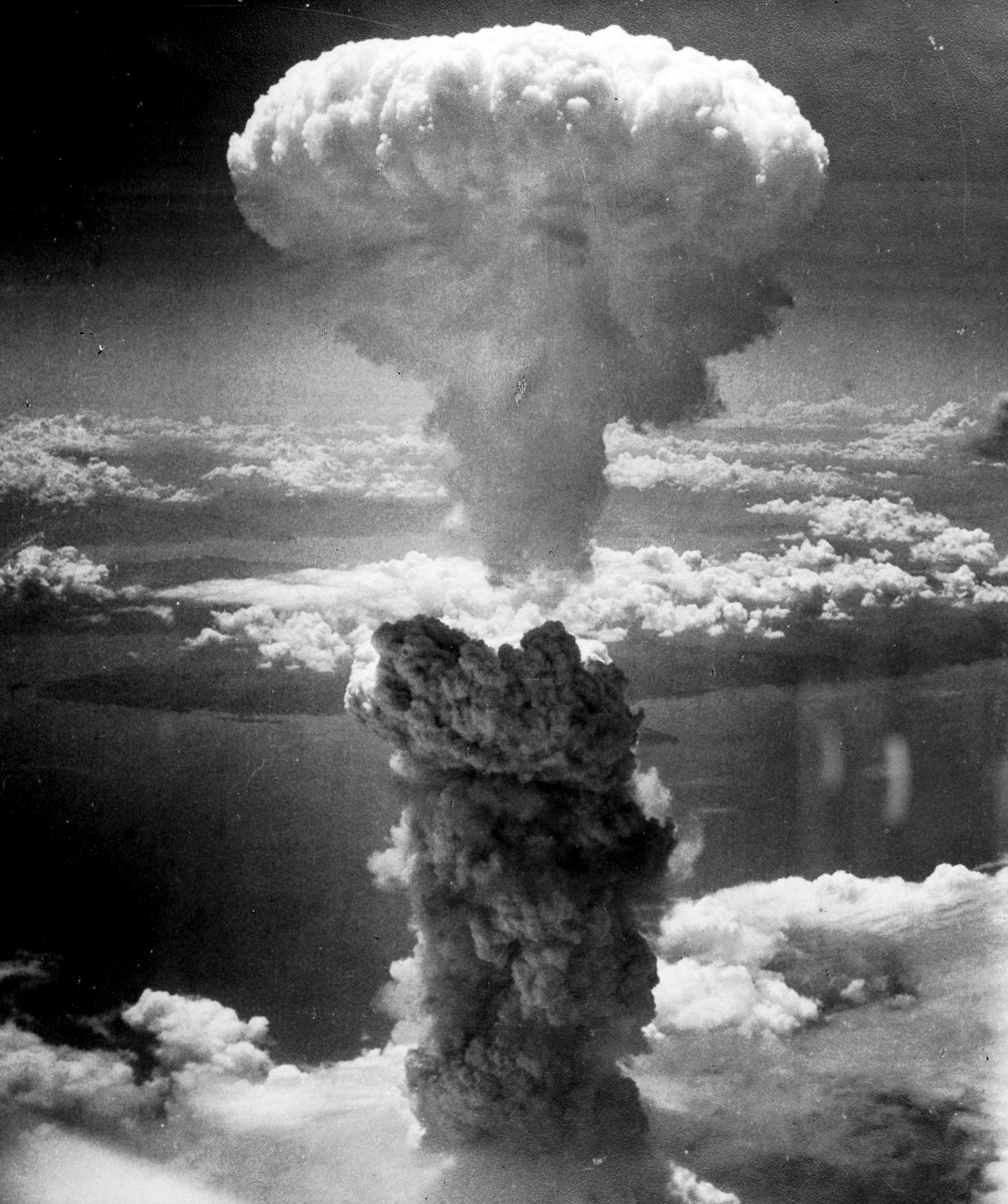

On 6 August 1945, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay flew over the Japanese city of Hiroshima in southwest Honshū and dropped a Gun-type fission weapon, gun-type uranium-235 atomic bomb (code-named Little Boy by the U.S.) on it. Two other B-29 aircraft were airborne nearby for the purposes of instrumentation and photography. When the planes first approached Hiroshima, Japanese anti-aircraft units in the city initially thought they were reconnaissance aircraft, since they were ordered not to shoot at one or few aircraft that did not pose a threat, in order to conserve their ammunition for large-scale air raids. The bomb killed roughly 90,000–166,000 people; half of these died quickly while the other half suffered lingering deaths. The death toll included an estimated 20,000 Korean slave laborers and 20,000 Japanese soldiers and destroyed 48,000 buildings (including the headquarters of the Second General Army and 5th Division (Imperial Japanese Army), Fifth Division). On 9 August, three days later, the B-29 Bockscar flew over the Japanese city of Nagasaki in northwest Kyushu and dropped an Nuclear weapon design#Implosion-type weapon, implosion-type, plutonium-239 atomic bomb (code-named Fat Man by the U.S.) on it, again accompanied by two other B-29 aircraft for instrumentation and photography. This bomb's effects killed roughly 39,000–80,000 people, including roughly 23,000–28,000 Japanese war industry employees, an estimated 2,000 Korean forced workers, and at least 150 Japanese soldiers. The bomb destroyed 60% of the city. The industrial damage in Nagasaki was high, partly owing to the inadvertent targeting of the industrial zone, leaving 68–80% of the non-dock industrial production destroyed.

Six days after the detonation over Nagasaki, Gyokuon-hoso, Hirohito announced Japan's surrender to the Allies on 15 August 1945, signing the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, Instrument of Surrender on 2 September 1945, officially ending the Pacific War and World War II. The two atomic bombings generated strong sentiments in Japan against all nuclear weapons. Japan adopted the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, which forbade the nation from developing nuclear armaments. Across the world anti-nuclear activists have made Hiroshima the central symbol of what they are opposing.

While the bombing campaign against Japan continued, the U.S. and its allies were preparing to Operation Downfall, invade the Japanese home islands, which they anticipated to be heavily costly in terms of life and property. On 1 April 1945, U.S. troops Battle of Okinawa, invaded the island of Okinawa and fought there fiercely against not only enemy soldiers, but also enemy civilians. After two and a half months, 12,000 U.S. servicemen, 107,000 Japanese soldiers, and over 150,000 Okinawan civilians (included those forced to fight) were killed. Given the casualty rate in Okinawa, American commanders realized a grisly picture of the intended invasion of mainland Japan. When President Harry S. Truman was briefed on what would happen during an invasion of Japan, he could not afford such a horrendous casualty rate, added to over 400,000 U.S. servicemen who had already died fighting in both the European and Pacific theaters of the war.

Hoping to forestall the invasion, the United States, the United Kingdom, and China issued a Potsdam Declaration on 26 July 1945, demanding that the Japanese government accept an unconditional surrender. The declaration also stated that if Japan did not surrender, it would be faced with "prompt and utter destruction", a process which was already underway with the incendiary bombing raids destroying 40% of targeted cities, and by naval warfare isolating and starving Japan of imported food. The Japanese government ignored (''mokusatsu'') this ultimatum, thus signalling that they were not going to surrender.

In the wake of this rejection, Stimson and George Marshall (the Army chief of staff) and Hap Arnold (head of the Army Air Forces) set the atomic bombing in motion.

On 6 August 1945, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay flew over the Japanese city of Hiroshima in southwest Honshū and dropped a Gun-type fission weapon, gun-type uranium-235 atomic bomb (code-named Little Boy by the U.S.) on it. Two other B-29 aircraft were airborne nearby for the purposes of instrumentation and photography. When the planes first approached Hiroshima, Japanese anti-aircraft units in the city initially thought they were reconnaissance aircraft, since they were ordered not to shoot at one or few aircraft that did not pose a threat, in order to conserve their ammunition for large-scale air raids. The bomb killed roughly 90,000–166,000 people; half of these died quickly while the other half suffered lingering deaths. The death toll included an estimated 20,000 Korean slave laborers and 20,000 Japanese soldiers and destroyed 48,000 buildings (including the headquarters of the Second General Army and 5th Division (Imperial Japanese Army), Fifth Division). On 9 August, three days later, the B-29 Bockscar flew over the Japanese city of Nagasaki in northwest Kyushu and dropped an Nuclear weapon design#Implosion-type weapon, implosion-type, plutonium-239 atomic bomb (code-named Fat Man by the U.S.) on it, again accompanied by two other B-29 aircraft for instrumentation and photography. This bomb's effects killed roughly 39,000–80,000 people, including roughly 23,000–28,000 Japanese war industry employees, an estimated 2,000 Korean forced workers, and at least 150 Japanese soldiers. The bomb destroyed 60% of the city. The industrial damage in Nagasaki was high, partly owing to the inadvertent targeting of the industrial zone, leaving 68–80% of the non-dock industrial production destroyed.

Six days after the detonation over Nagasaki, Gyokuon-hoso, Hirohito announced Japan's surrender to the Allies on 15 August 1945, signing the Japanese Instrument of Surrender, Instrument of Surrender on 2 September 1945, officially ending the Pacific War and World War II. The two atomic bombings generated strong sentiments in Japan against all nuclear weapons. Japan adopted the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, which forbade the nation from developing nuclear armaments. Across the world anti-nuclear activists have made Hiroshima the central symbol of what they are opposing.

''Decisive Air Power Prior to 1950''

USAF History and Museums Program. * Max Hastings, Hastings, Max (1979). ''RAF Bomber Command''. Pan Books. * Hinchcliffe, Peter (1996) ''The other battle : Luftwaffe night aces versus Bomber Command.'' Airlife Publishing, * Hooton, E.R (1994). ''Phoenix Triumphant; The Rise and Rise of the Luftwaffe''. London: Arms & Armour Press. * Hooton, E.R (1997). ''Eagle in Flames; The Fall of the Luftwaffe''. London: Arms & Armour Press. * Hooton, E.R (2007). ''Luftwaffe at War; Blitzkrieg in the West: Volume 2''. London: Chevron/Ian Allan. . * * Jane's (1989). ''All the World's Aircraft 1940/41/42/43/44/45.'' London, Random House, * * * * * Nelson, Hank (2003)

''A different war: Australians in Bomber Command''

paper presented at the 2003 History Conference – Air War Europe * Nelson, Hank (2006). ''Chased by the Sun: The Australians in Bomber Command in World War II'', Allen & Unwin, , * Overy, Richard J. (1980) ''The Air War'' Stein and Day. * (hardcover, paperback, 2002) * * * Poeppel, Hans and Prinz von Preußen, Wilhelm-Karl and von Hase, Karl-Günther. (2000) ''Die Soldaten der Wehrmacht.'' Herbig Verlag. * Price, Alfred. Kampfflieger -Bombers of the Luftwaffe January 1942-Summer 1943, Volume 3. 2005, Classic Publications. * * * Ray, John. ''The Night Blitz''. Booksales. . * * Richards, Denis. ''The Hardest Victory: RAF Bomber Command in the Second World War''. London: Coronet, 1995. . * R.J. Rummel

Was World War II American Urban Bombing Democide?

* Sherwood Ross.

How the United States Reversed Its Policy on Bombing Civilians

', The Humanist, Vol. 65, July–August 2005 * Smith, J. Richard and Creek, Eddie J. (2004). ''Kampflieger. Vol. 1.: Bombers of the Luftwaffe 1933–1940'' Classic Publications. * Smith, J. Richard and Creek, Eddie J. (2004). ''Kampflieger. Vol. 2.: Bombers of the Luftwaffe July 1940 – December 1941.'' Classic Publications. * Spaight. James M

''Bombing Vindicated''

Geoffrey Bles, London 1944. ASIN: B0007IVW7K (Spaight was Principal Assistant Secretary of the British Air Ministry) * Ronald H. Spector, Spector, Ronald (1985). ''Eagle Against the Sun.'' Vintage Books. * * * Saward, Dudley. (1985) ''Bomber Harris''. Doubleday. * * United States Strategic Bombing Survey

''Summary Report (Pacific War)''

1 July 1946. * United States Strategic Bombing Survey

30 September 1945. * United States Strategic Bombing Survey

1947. * United States Strategic Bombing Survey. ''The Effects of Strategic Bombing on German Transportation''. 1947. * United States Strategic Bombing Survey. ''The Effects of Strategic Bombing on the German War Economy''. 1945. * Willmott, H.P. (1991). ''The Great Crusade.'' Free Press, 1991. * Wood & Dempster (1990) ''The Narrow Margin'' Chapter "Second Phase" * Wood, Derek and Dempster, Derek. (1990). ''The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain and the Rise of Air Power'', London: Tri-Service Press, third revised edition. . * 徐 (Xú), 露梅 (Lùméi). ''隕落 (Fallen): 682位空军英烈的生死档案 - 抗战空军英烈档案大解密 (A Decryption of 682 Air Force Heroes of The War of Resistance-WWII and Their Martyrdom)''. 东城区, 北京, 中国: 团结出版社, 2016. .

online

* * Hayward, Joel S.A. ''Stopped at Stalingrad: The Luftwaffe and Hitler's Defeat in the East, 1942–1943''. University Press of Kansas, 1998. * * * * * * * * * * * * Smith, Major Phillip A. ''Bombing to Surrender: The contribution of air power to the collapse of Italy, 1943'' (Pickle Partners Publishing, 2014). * * – Spaight was Principal Assistant Secretary of the Air Ministry (U.K) * *

The Blitz: Sorting the Myth from the Reality

by ''BBC History''

Liverpool Blitz— Experience 24 hours in a city under fire in the Blitz

from National Museums Liverpool

Coventry Blitz Resource Centre

The 376th Heavy Bombardment Group Oral Histories

at Ball State University

Allied Bombers and Crews

– slideshow by ''Life magazine''

Annotated bibliography for conventional bombing during World War II

from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

The Revenger's Tragedy

by Leo McKinstry (in ''New Statesman'') {{DEFAULTSORT:Strategic Bombing During World War Ii World War II strategic bombing,

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1939–1945) involved sustained strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a systematically organized and executed military attack from the air which can utilize strategic bombers, long- or medium-range missiles, or nuclear-armed fighter-bomber aircraft to attack targets deemed vital to the enemy' ...

of railways, harbours, cities, workers' and civilian housing, and industrial districts in enemy territory. Strategic bombing as a military strategy

Military strategy is a set of ideas implemented by military organizations to pursue desired Strategic goal (military), strategic goals. Derived from the Greek language, Greek word ''strategos'', the term strategy, when first used during the 18th ...

is distinct both from close air support

Close air support (CAS) is defined as aerial warfare actions—often air-to-ground actions such as strafes or airstrikes—by military aircraft against hostile targets in close proximity to friendly forces. A form of fire support, CAS requires ...

of ground forces and from tactical air power. During World War II, many military strategists of air power

Airpower or air power consists of the application of military aviation, military strategy and strategic theory to the realm of aerial warfare and close air support. Airpower began in the advent of powered flight early in the 20th century. A ...

believed that air forces could win major victories by attacking industrial and political infrastructure

Infrastructure is the set of facilities and systems that serve a country, city, or other area, and encompasses the services and facilities necessary for its economy, households and firms to function. Infrastructure is composed of public and pri ...

, rather than purely military targets. Strategic bombing often involved bombing areas inhabited by civilians

A civilian is a person who is not a member of an armed force. It is illegal under the law of armed conflict to target civilians with military attacks, along with numerous other considerations for civilians during times of war. If a civilian enga ...

, and some campaigns were deliberately designed to target civilian populations in order to terrorize them or to weaken their morale

Morale ( , ) is the capacity of a group's members to maintain belief in an institution or goal, particularly in the face of opposition or hardship. Morale is often referenced by authority figures as a generic value judgment of the willpower, ...

. International law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

at the outset of World War II did not specifically forbid the aerial bombardment of cities – despite the prior occurrence of such bombing during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

(1914–1918), the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

(1936–1939), and the Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War was fought between the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the Empire of Japan between 1937 and 1945, following a period of war localized to Manchuria that started in 1931. It is considered part ...

(1937–1945).

Strategic bombing during World War II in Europe began on 1 September 1939 when Germany invaded Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak Republic, and the Soviet ...

and the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' (German Air Force) began bombing Polish cities and the civilian population in an aerial bombardment campaign. As the war continued to expand, bombing by both the Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

and the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

increased significantly. The Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, in retaliation for Luftwaffe attacks on the UK which started on 16 October 1939, began bombing military targets in Germany, commencing with the Luftwaffe seaplane air base at Hörnum on the 19–20 March 1940. In September 1940 the Luftwaffe began targeting British civilians in the Blitz

The Blitz (English: "flash") was a Nazi Germany, German bombing campaign against the United Kingdom, for eight months, from 7 September 1940 to 11 May 1941, during the Second World War.

Towards the end of the Battle of Britain in 1940, a co ...

. After the beginning of Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

in June 1941, the Luftwaffe attacked Soviet cities and infrastructure. From February 1942 onward, the British bombing campaign against Germany became even less restricted and increasingly targeted industrial sites and civilian areas.Garrett 1993 When the United States began flying bombing missions against Germany, it reinforced British efforts. The Allies attacked oil installations, and controversial firebombings took place against Hamburg (1943), Dresden

Dresden (; ; Upper Saxon German, Upper Saxon: ''Dräsdn''; , ) is the capital city of the States of Germany, German state of Saxony and its second most populous city after Leipzig. It is the List of cities in Germany by population, 12th most p ...

(1945), and other German cities.

In the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War or the Pacific Theatre, was the Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II fought between the Empire of Japan and the Allies of World War II, Allies in East Asia, East and Southeast As ...

, the Japanese frequently bombed civilian populations as early as 1937–1938, such as in Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

and Chongqing

ChongqingPostal Romanization, Previously romanized as Chungking ();. is a direct-administered municipality in Southwestern China. Chongqing is one of the four direct-administered municipalities under the State Council of the People's Republi ...

. US air raids on Japan

During the Pacific War, Allies of World War II, Allied forces conducted air raids on Japan from 1942 to 1945, causing extensive destruction to the country's cities and killing between 241,000 and 900,000 people. During the first years of the Pa ...

escalated from October 1944, culminating in widespread firebombing

Firebombing is a bombing technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs. In popular usage, any act in which an incendiary d ...

, and later in August 1945 with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On 6 and 9 August 1945, the United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, during World War II. The aerial bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civili ...

. The effectiveness of the strategic bombing campaigns is controversial.J.K. Galbraith, "The Affluent Society", chapter 12 "The Illusion of National Security", first published 1958. Galbraith was a director of the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey.Williamson Murray, Allan Reed Millett, "A War To Be Won: fighting the Second World War", p. 319

Although they did not produce decisive military victories in themselves, some argue that strategic bombing of non-military targets significantly reduced enemy industrial capacity and production, and was vindicated by the surrender of Japan

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was Hirohito surrender broadcast, announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally Japanese Instrument of Surrender, signed on 2 September 1945, End of World War II in Asia, ending ...

. Estimates of the death toll from strategic bombing range from hundreds of thousands to over a million. Millions of civilians were made homeless, and many major cities were destroyed, especially in Europe and Asia.

Legal considerations

TheHague Conventions of 1899 and 1907

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions were amon ...

, which address the codes of wartime conduct on land and at sea, were adopted before the rise of air power. Despite repeated diplomatic attempts to update international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict or the laws of war, is the law that regulates the conduct of war (''wikt:jus in bello, jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit ...

to include aerial warfare

Aerial warfare is the use of military aircraft and other flying machines in warfare. Aerial warfare includes bombers attacking tactical bombing, enemy installations or a concentration of enemy troops or Strategic bombing, strategic targets; fi ...

, it was not updated before the outbreak of World War II. The absence of specific international humanitarian law did not mean aerial warfare was not covered under the laws of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

, but rather that there was no general agreement of how to interpret those laws. This means that aerial bombardment of civilian areas in enemy territory by all major belligerents during World War II was not prohibited by positive

Positive is a property of positivity and may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Positive formula, a logical formula not containing negation

* Positive number, a number that is greater than 0

* Plus sign, the sign "+" used to indicate a positi ...

or specific customary international humanitarian law.

Many reasons exist for the absence of international law regarding aerial bombing in World War II. Most nations had refused to ratify such laws or agreements because of the vague or impractical wording in treaties such as the 1923 Hague Rules of Air Warfare. Also, the major powers' possession of newly developed advanced bombers was a great military advantage; they would be hard pressed to accept any negotiated limitations regarding this new weapon. In the absence of specific laws relating to aerial warfare, the belligerents' aerial forces at the start of World War II used the 1907 Hague Conventions — signed and ratified by most major powers — as the customary standard to govern their conduct in warfare, and these conventions were interpreted by both sides to allow the indiscriminate bombing of enemy cities throughout the war.

General Telford Taylor

Telford Taylor (February 24, 1908 – May 23, 1998) was an American lawyer and professor. Taylor was known for his role as lead counsel in the prosecution of war criminals after World War II, his opposition to McCarthyism in the 1950s, and his o ...

, Chief Counsel for War Crimes

A war crime is a violation of the laws of war that gives rise to individual criminal responsibility for actions by combatants in action, such as intentionally killing civilians or intentionally killing prisoners of war, torture, taking hos ...

at the Nuremberg Trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

, wrote that:

Article 25 of the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions on Land Warfare also did not provide a clear guideline on the extent to which civilians may be spared; the same can be held for naval forces. Consequently, cyclical arguments, such as those advanced by Italian general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

and air power

Airpower or air power consists of the application of military aviation, military strategy and strategic theory to the realm of aerial warfare and close air support. Airpower began in the advent of powered flight early in the 20th century. A ...

theorist Giulio Douhet

Giulio Douhet (30 May 1869 – 15 February 1930) was an Italian general and air power theorist. He was a key proponent of strategic bombing in aerial warfare. He was a contemporary of the air warfare advocates Walther Wever, Billy Mitchell, ...

, do not appear to violate any of the convention's provisions. Due to these reasons, the Allies at the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE), also known as the Tokyo Trial and the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal, was a military trial convened on 29 April 1946 to try leaders of the Empire of Japan for their crimes against peace ...

never criminalized aerial bombardment of non-combatant targets and Axis leaders who ordered a similar type of practice were not prosecuted. Chris Jochnick and Roger Normand in their article ''The Legitimation of Violence 1: A Critical History of the Laws of War'' explains that: "By leaving out morale bombing and other attacks on civilians unchallenged, the Tribunal conferred legal legitimacy on such practices."

Ethical considerations

The concept ofstrategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a systematically organized and executed military attack from the air which can utilize strategic bombers, long- or medium-range missiles, or nuclear-armed fighter-bomber aircraft to attack targets deemed vital to the enemy' ...

and its wide-scale implementation during WWII led to a post-war debate if it was moral.Air Marshal Sir Robert Saundby, Royal Air ForceThe Ethics of Bombing

''The Royal Air Force Quarterly'', No. 2, Summer 1967 Three separate lines of ethical reasoning emerged.Johnson, James Turner

Bombing, Ethics of

In Chambers, John Whiteclay

''The Oxford Companion to American Military History''

New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. The first was based on the

Just War theory

The just war theory () is a doctrine, also referred to as a tradition, of military ethics that aims to ensure that a war is morally justifiable through a series of #Criteria, criteria, all of which must be met for a war to be considered just. I ...

and emphasized that noncombatants possess an inherent right to be spared from the harm of war and should not be intentionally targeted. John C. Ford

John Cuthbert Ford, SJ, (December 20, 1902 - January 14, 1989) was a Catholic moral theologian. His work was widely relied upon by Catholics in the twentieth century for guidance on a wide range of moral questions. He was a professor of moral th ...

, SJ, made such an argument in an article in 1944. Noncombatant immunity and proportionality in use of force were insisted upon.

The second approach was grounded in the so-called "industrial web theory" that proposed to concentrate on destroying enemy military, industrial, and economic infrastructure instead of forces in the field as the fastest way to win the war. Proponents of this approach argued that civilian deaths inflicted by strategic bombing of the cities during the WWII were justified in the sense that they allowed a shortening of the war and thus helped to avoid many more casualties.

The third approach was demonstrated by Michael Walzer

Michael Laban Walzer (born March 3, 1935) is an American Political theory, political theorist and public intellectual. A professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) in Princeton, New Jersey, he is editor emeritus of the left-win ...

in his ''Just and Unjust Wars

''Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations'' is a 1977 book by the philosopher Michael Walzer. Published by Basic Books, it is still in print, now as part of the Basic Books Classics Series. A second edition was publish ...

'' (1977). Walzer formulated the so-called " supreme emergency" thesis. While agreeing in general with prior Just War theoretical postulates, he came to a conclusion that a grave threat to a moral order would justify the use of an indiscriminate force.

Air Marshal Sir Robert Saundby

Air Marshal Sir Robert Henry Magnus Spencer Saundby, (26 April 1896 – 26 September 1971) was a senior Royal Air Force officer whose career spanned both the First and Second World Wars. He distinguished himself by gaining five victories during ...

concluded his analysis of the ethics of bombing by these words,

Europe

Policy at the start of the war

Before World War II began, the rapid pace of aviation technology created a belief that groups of bombers would be capable of devastating cities. For example, British Prime MinisterStanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley (3 August 186714 December 1947), was a British statesman and Conservative politician who was prominent in the political leadership of the United Kingdom between the world wars. He was prime ministe ...

warned in 1932, "The bomber will always get through

"The bomber will always get through" was a phrase used by Stanley Baldwin in a 1932 speech "A Fear for the Future" given to the British Parliament. His speech stated that contemporary bomber aircraft had the performance necessary to conduct a ...

."

When the war began on 1 September 1939 with Germany's invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, President of the armed neutralitarian United States, issued an appeal to the major belligerents (Britain, France, Germany, and Poland) to confine their air raids to military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

targets, and "under no circumstances undertake bombardment from the air of civilian populations in unfortified cities". The British and French agreed to abide by the request, with the British reply undertaking to "confine bombardment to strictly military objectives upon the understanding that these same rules of war

The law of war is a component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of hostilities (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territories, ...

fare will be scrupulously observed by all their opponents". Germany also agreed to abide by Roosevelt's request and explained the bombing of Warsaw as within the agreement because it was supposedly a fortified city—Germany did not have a policy of targeting enemy civilians as part of their doctrine prior to World War II.

The British Government's policy was formulated on 31 August 1939: if Germany initiated unrestricted air action, the RAF "should attack objectives vital to Germany's war effort, and in particular her oil resources". If the ''Luftwaffe'' confined attacks to purely military targets, the RAF should "launch an attack on the German fleet at Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

" and "attack warships at sea when found within range". The government communicated to their French allies the intention "not to initiate air action which might involve the risk of civilian casualties".

While it was acknowledged bombing Germany would cause civilian casualties, the British government renounced deliberate bombing of civilian property, outside combat zones, as a military tactic. The British changed their policy on 15 May 1940, one day after the German bombing of Rotterdam, when the RAF was given permission to attack targets in the Ruhr Area

The Ruhr ( ; , also ''Ruhrpott'' ), also referred to as the Ruhr Area, sometimes Ruhr District, Ruhr Region, or Ruhr Valley, is a polycentric urban area in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. With a population density of 1,160/km2 and a populati ...

, including oil plants and other civilian industrial targets which aided the German war effort, such as blast furnace

A blast furnace is a type of metallurgical furnace used for smelting to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron, but also others such as lead or copper. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure.

In a ...

s that at night were self-illuminating. The first RAF raid on the interior of Germany took place on the night of 15/16 May 1940 while the Battle of France

The Battle of France (; 10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign (), the French Campaign (, ) and the Fall of France, during the Second World War was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of the Low Countries (Belgium, Luxembour ...

was still continuing.

Early war in Europe

Poland

During the German invasion of Poland, the ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' engaged in massive air raids against Polish cities,Bruno Coppieters, N. Fotion, eds. (2002) ''Moral constraints on war: principles and cases'', Lexington Booksp 74.

/ref> bombing civilian infrastructure such as hospitalsSylwia Słomińska

, Z dziejów dawnego Wielunia "History of old Wielun", site by Dr Tadeusz Grabarczyk, Historical Institute at University of Lodz, and targeting fleeing refugees.Norman Davies. (1982). ''God's Playground: A History of Poland'', Columbia University Press

p 437.

/ref> Notably, the ''Luftwaffe'' bombed the Polish capital of Warsaw, and the small towns

Wieluń

Wieluń () is a town in south-central Poland with 21,624 inhabitants (2021). The town is the seat of the Gmina Wieluń and Wieluń County, and is located within the Łódź Voivodeship. Wieluń is a capital of the historical Wieluń Land.

W ...

and Frampol

Frampol is a town in Poland, in Biłgoraj County, Lublin Voivodeship. It has 1,431 inhabitants (December 2021), and lies in eastern Lesser Poland, near the Roztocze Upland. Frampol is surrounded by the Szczebrzeszyn Landscape Park and the Janów ...

. The bombing of Wieluń

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

, one of the first military acts of World War II and the first major act of bombing, was carried out on a town that had little to no military value. Similarly, the bombing of Frampol has been described as an experiment to test the German tactics and weapons effectiveness. British historian Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a British and Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Profes ...

writes in '' Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory'': "Frampol was chosen partly because it was completely defenceless, and partly because its baroque street plan presented a perfect geometric grid for calculations and measurements."

In his book, ''Augen am Himmel'' (''Eyes on the Sky''), Wolfgang Schreyer

Wolfgang Schreyer (20 November 1927 – 14 November 2017) was a German writer of fiction, historic adventures mixed with documentary, science fiction for TV shows and movies and is best known as the author of over 20 adventure stories.

Life ...

wrote:

Frampol was chosen as an experimental object, because test bombers, flying at low speed, weren't endangered by AA fire. Also, the centrally placed town hall was an ideal orientation point for the crews. We watched possibility of orientation after visible signs, and also the size of village, what guaranteed that bombs nevertheless fall down on Frampol. From one side it should make easier the note of probe, from second side it should confirm the efficiency of used bombs.The directives issued to the ''Luftwaffe'' for the Polish Campaign were to prevent the

Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force () is the aerial warfare Military branch, branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 26,000 military personnel an ...

from influencing the ground battles or attacking German territory.Speidel, p. 18 In addition, it was to support the advance of German ground forces through direct tactical and indirect air support with attacks against Polish mobilisation centres and thus delay an orderly Polish strategic concentration of forces and to deny mobility for Polish reinforcements through the destruction of strategic Polish rail routes.

Preparations were made for a concentrated attack (Operation Wasserkante) by all bomber forces against targets in Warsaw. However, the operation was cancelled, according to Polish professor

Preparations were made for a concentrated attack (Operation Wasserkante) by all bomber forces against targets in Warsaw. However, the operation was cancelled, according to Polish professor Tomasz Szarota

Tomasz Marceli Szarota (born 2 January 1940 in Warsaw) is a Polish historian and publicist. As a historian, his areas of expertise relate to history of World War II, and everyday life in occupied Poland, in particular, in occupied Warsaw and oth ...

due to bad weather conditions, while German author Horst Boog

Horst Boog (5 January 1928 – 8 January 2016) was a German historian who specialised in the history of Nazi Germany and World War II. He was the research director at the Military History Research Office (MGFA). Boog was a contributor to ...

claims it was possibly due to Roosevelt's plea to avoid civilian casualties; according to Boog the bombing of military and industrial targets within the Warsaw residential area called Praga was prohibited. Polish reports from the beginning of September note strafing of civilians by German attacks and bombing of cemeteries and marked hospitals (marking of hospitals proved counterproductive as German aircraft began to specifically target them, until hospitals were moved into the open to avoid such targeting), and indiscriminate attacks on fleeing civilians which according to Szarota was a direct violation of the Hague Convention.Straty Warszawy 1939–1945.Raport pod red. Wojciecha Fałkowskiego, Naloty na Warszawę podczas II wojny światowej Tomasz Szarota, pages 240–281. Warszawa: Miasto Stołeczne Warszawa 2005 Warsaw was first attacked by German ground forces on 9 September and was put under siege on 13 September. German author Boog claims that with the arrival of German ground forces, the situation of Warsaw changed; under the Hague Convention, the city could be legitimately attacked as it was a defended city in the front line that refused calls to surrender.Boog 2001, p. 361.

The bombing of the rail network, crossroads, and troop concentrations played havoc on Polish mobilisation, while attacks upon civilian and military targets in towns and cities disrupted command and control by wrecking the antiquated Polish signal network. Over a period of a few days, ''Luftwaffe'' numerical and technological superiority took its toll on the Polish Air Force. Polish Air Force bases across Poland were also subjected to ''Luftwaffe'' bombing from 1 September 1939.

On 13 September, following orders of the Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe (German ''Oberbefehlshaber der Luftwaffe'' (''ObdL'')) to launch an attack on Warsaw's Jewish Quarter, justified as being for unspecified crimes committed against German soldiers but probably in response to a recent defeat by Polish ground troops, and intended as a terror attack,Hooton 1994, p. 187. 183 bomber sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

s were flown with 50:50 load of high explosive and incendiary bombs, reportedly set the Jewish Quarter ablaze. On 22 September, Wolfram von Richthofen

Wolfram Karl Ludwig Moritz Hermann Freiherr von Richthofen (10 October 1895 – 12 July 1945) was a German World War I flying ace who rose to the rank of ''Generalfeldmarschall'' (Field Marshal) in the Luftwaffe during World War II.

In the ...

messaged, "Urgently request exploitation of last opportunity for large-scale experiment as devastation terror raid ... Every effort will be made to eradicate Warsaw completely". His request was rejected. However, Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

issued an order to prevent civilians from leaving the city and to continue with the bombing, which he thought would encourage Polish surrender.Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts, (2004). ''Encyclopedia of World War II: a political, social and military history'', ABC-CLIOp 1613.

/ref> On 14 September, the French

Air attaché

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosphere ...

in Warsaw reported to Paris, "the German Air Force acted in accordance to the international laws of war ..and bombed only targets of military nature. Therefore, there is no reason for French retorsion Retorsion (from , from , influenced by Late Latin, 1585–1595, , a twisting, wringing it), a term used in international law, is an act perpetrated by one nation upon another in retaliation for a similar act perpetrated by the other nation. A typica ...

s." That day – the Jewish New Year – the Germans concentrated again on the Warsaw's Jewish population, bombing the Jewish quarter and targeting synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

s. According to professor Szarota the report was inaccurate – as its author Armengaud didn't know about the most barbaric bombings like those in Wieluń or Kamieniec, left Poland on 12 September, and was motivated by his personal political goal to avoid French involvement in the war, in addition the report published in 1948 rather than in 1939.

Three days later, Warsaw was surrounded by the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

, and hundreds of thousands of leaflets were dropped on the city, instructing citizens to evacuate the city pending a possible bomber attack. On 25 September the ''Luftwaffe'' flew 1,150 sorties and dropped 560 tonnes of high explosive and 72 tonnes of incendiaries.Hooton 1994, p. 92. (Overall, incendiaries made up only three percent of the total tonnage dropped.)

To conserve the strength of the bomber units for the upcoming Western campaign, the modern He 111