Steve Biko on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Bantu Stephen Biko OMSG (18 December 1946 – 12 September 1977) was a South African anti-apartheid activist. Ideologically an

African nationalist

African nationalism is an umbrella term which refers to a group of political ideologies in sub-Saharan Africa, which are based on the idea of national self-determination and the creation of nation states.African socialist, he was at the forefront of a grassroots anti-apartheid campaign known as the

Biko's given name "Bantu" means "people" in

Biko's given name "Bantu" means "people" in

Biko was initially interested in studying law at university, but many of those around him discouraged this, believing that law was too closely intertwined with political activism. Instead they convinced him to choose medicine, a subject thought to have better career prospects. He secured a scholarship, and in 1966 entered the

Biko was initially interested in studying law at university, but many of those around him discouraged this, believing that law was too closely intertwined with political activism. Instead they convinced him to choose medicine, a subject thought to have better career prospects. He secured a scholarship, and in 1966 entered the

In December 1975, attempting to circumvent the restrictions of the banning order, the BPC declared Biko their honorary president. After Biko and other BCM leaders were banned, a new leadership arose, led by Muntu Myeza and Sathasivian Cooper, who were considered part of the Durban Moment. Myeza and Cooper organised a BCM demonstration to mark

In December 1975, attempting to circumvent the restrictions of the banning order, the BPC declared Biko their honorary president. After Biko and other BCM leaders were banned, a new leadership arose, led by Muntu Myeza and Sathasivian Cooper, who were considered part of the Durban Moment. Myeza and Cooper organised a BCM demonstration to mark

Speaking publicly about Biko's death, the country's police minister Jimmy Kruger initially implied that it had been the result of a

Speaking publicly about Biko's death, the country's police minister Jimmy Kruger initially implied that it had been the result of a

Biko is viewed as the "father" of the Black Consciousness Movement and the anti-apartheid movement's first icon.

Biko is viewed as the "father" of the Black Consciousness Movement and the anti-apartheid movement's first icon.

The Steve Biko Foundation

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Biko, Steve 1946 births 1977 deaths 1977 in South Africa 20th-century Christians 20th-century South African male writers 20th-century South African politicians South African anti-apartheid activists Assassinated South African activists Assassinated South African politicians Assassinated civil rights activists Biko family Black Consciousness Movement Deaths by beating Deaths in police custody in South Africa Extrajudicial killings in South Africa People from Qonce People murdered by law enforcement officers Police brutality in South Africa Prisoners who died in South African detention South African Christians South African writers South African pan-Africanists South African people who died in prison custody South African prisoners and detainees South African revolutionaries Steve Biko affair University of Natal alumni Victims of police brutality Xhosa people African politicians assassinated in the 1970s Politicians assassinated in 1977 Alumni of Lovedale

Black Consciousness Movement

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Af ...

during the late 1960s and 1970s. His ideas were articulated in a series of articles published under the pseudonym Frank Talk.

Raised in a poor Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

family, Biko grew up in Ginsberg township in the Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

. In 1966, he began studying medicine at the University of Natal

The University of Natal was a university in the former South African province Natal which later became KwaZulu-Natal. The University of Natal no longer exists as a distinct legal entity, as it was incorporated into the University of KwaZulu- ...

, where he joined the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). Strongly opposed to the apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

system of racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

and white-minority rule in South Africa, Biko was frustrated that NUSAS and other anti-apartheid groups were dominated by white liberals, rather than by the blacks who were most affected by apartheid. He believed that well-intentioned white liberals failed to comprehend the black experience and often acted in a paternalistic manner. He developed the view that to avoid white domination, black people had to organise independently, and to this end he became a leading figure in the creation of the South African Students' Organisation (SASO) in 1968. Membership was open only to "blacks", a term that Biko used in reference not just to Bantu-speaking Africans but also to Coloureds

Coloureds () are multiracial people in South Africa, Namibia and, to a smaller extent, Zimbabwe and Zambia. Their ancestry descends from the interracial mixing that occurred between Europeans, Africans and Asians. Interracial mixing in South ...

and Indians. He was careful to keep his movement independent of white liberals, but opposed anti-white hatred and had white friends. The white-minority National Party government were initially supportive, seeing SASO's creation as a victory for apartheid's ethos of racial separatism.

Influenced by the Martinican philosopher Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

and the African-American Black Power movement, Biko and his compatriots developed Black Consciousness as SASO's official ideology. The movement campaigned for an end to apartheid and the transition of South Africa toward universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

and a socialist economy

Socialist economics comprises the economic theories, practices and norms of hypothetical and existing socialist economic systems. A socialist economic system is characterized by social ownership and operation of the means of production that m ...

. It organised Black Community Programmes (BCPs) and focused on the psychological empowerment of black people. Biko believed that black people needed to rid themselves of any sense of racial inferiority, an idea he expressed by popularizing the slogan "black is beautiful

Black is beautiful is a cultural movement that was started in the United States in the 1960s by African Americans. It later spread beyond the United States, most prominently in the writings of the Black Consciousness Movement of Steve Biko ...

". In 1972, he was involved in founding the Black People's Convention (BPC) to promote Black Consciousness ideas among the wider population. The government came to see Biko as a subversive threat and placed him under a banning order in 1973, severely restricting his activities. He remained politically active, helping organise BCPs such as a healthcare centre and a crèche in the Ginsberg area. During his ban he received repeated anonymous threats, and was detained by state security services on several occasions. Following his arrest in August 1977, Biko was beaten to death by state security officers. Over 20,000 people attended his funeral.

Biko's fame spread posthumously. He became the subject of numerous songs and works of art, while a 1978 biography by his friend Donald Woods formed the basis for the 1987 film ''Cry Freedom

''Cry Freedom'' is a 1987 epic biographical drama film directed and produced by Richard Attenborough, set in late-1970s apartheid-era South Africa. The screenplay was written by John Briley based on a pair of books by journalist Donald Woods. ...

''. During Biko's life, the government alleged that he hated whites, various anti-apartheid activists accused him of sexism, and African racial nationalists criticised his united front with Coloureds and Indians. Nonetheless, Biko became one of the earliest icons of the movement against apartheid, and is regarded as a political martyr and the "Father of Black Consciousness". His political legacy remains a matter of contention.

Biography

Early life: 1946–1966

Bantu Stephen Biko was born on 18 December 1946, at his grandmother's house in Tarkastad,Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

. The third child of Mzingaye Mathew Biko and Alice 'Mamcete' Biko, he had an older sister, Bukelwa, an older brother, Khaya, and a younger sister, Nobandile. His parents had married in Whittlesea, where his father worked as a police officer. Mzingaye was transferred to Queenstown, Port Elizabeth

Gqeberha ( , ), formerly named Port Elizabeth, and colloquially referred to as P.E., is a major seaport and the most populous city in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is the seat of the Nelson Mandela Bay Metropolitan Municipal ...

, Fort Cox, and finally King William's Town

Qonce, formerly King William's Town, is a town in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa along the banks of the Buffalo River (Eastern Cape), Buffalo River. The town is about northwest of the Indian Ocean port of East London, South Africa, ...

, where he and Alice settled in Ginsberg township. This was a settlement of around 800 families, with every four families sharing a water supply and toilet. Both Africans

The ethnic groups of Africa number in the thousands, with each ethnicity generally having their own language (or dialect of a language) and culture. The ethnolinguistic groups include various Afroasiatic, Khoisan, Niger-Congo, and Nilo-Sahara ...

and Coloured

Coloureds () are multiracial people in South Africa, Namibia and, to a smaller extent, Zimbabwe and Zambia. Their ancestry descends from the interracial mixing that occurred between Europeans, Africans and Asians. Interracial mixing in South ...

people lived in the township

A township is a form of human settlement or administrative subdivision. Its exact definition varies among countries.

Although the term is occasionally associated with an urban area, this tends to be an exception to the rule. In Australia, Canad ...

, where Xhosa

Xhosa may refer to:

* Xhosa people, a nation, and ethnic group, who live in south-central and southeasterly region of South Africa

* Xhosa language, one of the 11 official languages of South Africa, principally spoken by the Xhosa people

See als ...

, Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

, and English were all spoken. After resigning from the police force, Mzingaye worked as a clerk in the King William's Town Native Affairs Office, while studying for a law degree by correspondence from the University of South Africa

The University of South Africa (UNISA) is the largest university system in South Africa by enrollment. It attracts a third of all higher education students in South Africa. Through various colleges and affiliates, UNISA has over 400,000 student ...

. Alice was employed first in domestic work for local white households, then as a cook at Grey Hospital in King William's Town. According to his sister, it was this observation of his mother's difficult working conditions that resulted in Biko's earliest politicisation.

Biko's given name "Bantu" means "people" in

Biko's given name "Bantu" means "people" in IsiXhosa

Xhosa ( , ), formerly spelled ''Xosa'' and also known by its local name ''isiXhosa'', is a Bantu language, indigenous to Southern Africa and one of the official languages of South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Xhosa is spoken as a first language ...

; Biko interpreted this in terms of the saying ''"Umntu ngumntu ngabantu"'' ("a person is a person by means of other people"). As a child he was nicknamed "Goofy" and "Xwaku-Xwaku", the latter a reference to his unkempt appearance. He was raised in his family's Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

Christian faith. In 1950, when Biko was four, his father fell ill, was hospitalised in St. Matthew's Hospital, Keiskammahoek, and died, making the family dependent on his mother's income.

Biko spent two years at St. Andrews Primary School and four at Charles Morgan Higher Primary School, both in Ginsberg. Regarded as a particularly intelligent pupil, he was allowed to skip a year. In 1963 he transferred to the Forbes Grant Secondary School in the township. Biko excelled at maths and English and topped the class in his exams. In 1964 the Ginsberg community offered him a bursary to join his brother Khaya as a student at Lovedale, a prestigious boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

in Alice, Eastern Cape

Alice, officially Dikeni, is a small town in Eastern Cape, South Africa that is named after Princess Alice of the United Kingdom, Princess Alice, the daughter of the British Queen Victoria. It was settled in 1824 by British colonists. It is a ...

. Within three months of Steve's arrival, Khaya was accused of having connections to Poqo, the armed wing of the Pan Africanist Congress

The Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, often shortened to the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), is a South African pan-Africanist national liberation movement that is now a political party. It was founded by an Africanist group, led by Robert So ...

(PAC), an African nationalist

African nationalism is an umbrella term which refers to a group of political ideologies in sub-Saharan Africa, which are based on the idea of national self-determination and the creation of nation states.Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

boarding school in Mariannhill, Natal. The college had a liberal political culture, and Biko developed his political consciousness there. He became particularly interested in the replacement of South Africa's white minority government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

with an administration that represented the country's black majority. Among the anti-colonialist

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholars of decolon ...

leaders who became Biko's heroes at this time were Algeria's Ahmed Ben Bella

Ahmed Ben Bella (; 25 December 1916 – 11 April 2012) was an Algerian politician, soldier and socialist revolutionary who served as the head of government of Algeria from 27 September 1962 to 15 September 1963 and then the first president of ...

and Kenya's Jaramogi Oginga Odinga. He later said that most of the "politicos" in his family were sympathetic to the PAC, which had anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

and African racialist ideas. Biko admired what he described as the PAC's "terribly good organisation" and the courage of many of its members, but he remained unconvinced by its racially exclusionary approach, believing that members of all racial groups should unite against the government. In December 1964, he travelled to Zwelitsha for the ulwaluko

''Ulwaluko'' is a traditional circumcision and initiation rite practised (though not exclusively) by the Xhosa people, and is commonly practised throughout South Africa. The ritual is traditionally intended as a teaching institution, to prepare ...

circumcision

Circumcision is a procedure that removes the foreskin from the human penis. In the most common form of the operation, the foreskin is extended with forceps, then a circumcision device may be placed, after which the foreskin is excised. T ...

ceremony, symbolically marking his transition from boyhood to manhood.

Early student activism: 1966–1968

Biko was initially interested in studying law at university, but many of those around him discouraged this, believing that law was too closely intertwined with political activism. Instead they convinced him to choose medicine, a subject thought to have better career prospects. He secured a scholarship, and in 1966 entered the

Biko was initially interested in studying law at university, but many of those around him discouraged this, believing that law was too closely intertwined with political activism. Instead they convinced him to choose medicine, a subject thought to have better career prospects. He secured a scholarship, and in 1966 entered the University of Natal

The University of Natal was a university in the former South African province Natal which later became KwaZulu-Natal. The University of Natal no longer exists as a distinct legal entity, as it was incorporated into the University of KwaZulu- ...

Medical School. There, he joined what his biographer Xolela Mangcu called "a peculiarly sophisticated and cosmopolitan group of students" from across South Africa; many of them later held prominent roles in the post-apartheid era. The late 1960s was the heyday of radical student politics across the world, as reflected in the protests of 1968

The protests of 1968 comprised a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, which were predominantly characterized by the rise of left-wing politics, Anti-war movement, anti-war sentiment, Civil and political rights, civil rights urgency, youth C ...

, and Biko was eager to involve himself in this environment. Soon after he arrived at the university, he was elected to the Students' Representative Council (SRC).

The university's SRC was affiliated with the National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). NUSAS had taken pains to cultivate a multi-racial membership but remained white-dominated because the majority of South Africa's students were from the country's white minority. As Clive Nettleton, a white NUSAS leader, put it: "the essence of the matter is that NUSAS was founded on white initiative, is financed by white money and reflects the opinions of the majority of its members who are white". NUSAS officially opposed apartheid, but it moderated its opposition in order to maintain the support of conservative white students. Biko and several other black African NUSAS members were frustrated when it organised parties in white dormitories, which black Africans were forbidden to enter. In July 1967, a NUSAS conference was held at Rhodes University

Rhodes University () is a public research university located in Makhanda (formerly Grahamstown) in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. It is one of four universities in the province.

Established in 1904, Rhodes University is the prov ...

in Grahamstown

Makhanda, formerly known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 75,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Gqeberha and southwest of East London. It is the largest town in the Makana Local Mun ...

; after the students arrived, they found that dormitory accommodation had been arranged for the white and Indian delegates but not the black Africans, who were told that they could sleep in a local church. Biko and other black African delegates walked out of the conference in anger. Biko later related that this event forced him to rethink his belief in the multi-racial approach to political activism:

Founding the South African Students' Organisation: 1968–1972

Developing SASO

Following the 1968 NUSAS conference inJohannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

, many of its members attended a July 1968 conference of the University Christian Movement at Stutterheim. There, the black African members decided to hold a December conference to discuss the formation of an independent black student group. The South African Students' Organisation (SASO) was officially launched at a July 1969 conference at the University of the North

The University of Limpopo () is a public university in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. It was formed on 1 January 2005, by merger of the University of the North and the Medical University of South Africa (MEDUNSA). These previous institutio ...

; there, the group's constitution and basic policy platform were adopted. The group's focus was on the need for contact between centres of black student activity, including through sport, cultural activities, and debating competitions. Though Biko played a substantial role in SASO's creation, he sought a low public profile during its early stages, believing that this would strengthen its second level of leadership, such as his ally Barney Pityana. Nonetheless, he was elected as SASO's first president; Pat Matshaka was elected vice president and Wuila Mashalaba elected secretary. Durban became its ''de facto'' headquarters.

Biko developed SASO's ideology of "Black Consciousness" in conversation with other black student leaders. A SASO policy manifesto produced in July 1971 defined this ideology as "an attitude of mind, a way of life. The basic tenet of Black Consciousness is that the Blackman must reject all value systems that seek to make him a foreigner in the country of his birth and reduce his basic human dignity." Black Consciousness centred on psychological empowerment, through combating the feelings of inferiority that most black South Africans exhibited. Biko believed that, as part of the struggle against apartheid and white-minority rule, blacks should affirm their own humanity by regarding themselves as worthy of freedom and its attendant responsibilities. It applied the term "black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

" not only to Bantu-speaking Africans, but also to Indians and Coloureds. SASO adopted this term over "non-white" because its leadership felt that defining themselves in opposition to white people was not a positive self-description. Biko promoted the slogan "black is beautiful

Black is beautiful is a cultural movement that was started in the United States in the 1960s by African Americans. It later spread beyond the United States, most prominently in the writings of the Black Consciousness Movement of Steve Biko ...

", explaining that this meant "Man, you are okay as you are. Begin to look upon yourself as a human being."

Biko presented a paper on "White Racism and Black Consciousness" at an academic conference

An academic conference or scientific conference (also congress, symposium, workshop, or meeting) is an Convention (meeting), event for researchers (not necessarily academics) to present and discuss their scholarly work. Together with academic jou ...

in the University of Cape Town

The University of Cape Town (UCT) (, ) is a public university, public research university in Cape Town, South Africa.

Established in 1829 as the South African College, it was granted full university status in 1918, making it the oldest univer ...

's Abe Bailey Centre in January 1971. He also expanded on his ideas in a column written for the ''SASO Newsletter'' under the pseudonym "Frank Talk". His tenure as president was taken up largely by fundraising activities, and involved travelling around various campuses in South Africa to recruit students and deepen the movement's ideological base. Some of these students censured him for abandoning NUSAS' multi-racial approach; others disapproved of SASO's decision to allow Indian and Coloured students to be members. Biko stepped down from the presidency after a year, insisting that it was necessary for a new leadership to emerge and thus avoid any cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

forming around him.

SASO decided after a debate to remain non-affiliated with NUSAS, but would nevertheless recognise the larger organisation as the national student body. One of SASO's founding resolutions was to send a representative to each NUSAS conference. In 1970 SASO withdrew its recognition of NUSAS, accusing it of attempting to hinder SASO's growth on various campuses. SASO's split from NUSAS was a traumatic experience for many white liberal youth who had committed themselves to the idea of a multi-racial organisation and felt that their attempts were being rebuffed. The NUSAS leadership regretted the split, but largely refrained from criticising SASO. The governmentwhich regarded multi-racial liberalism as a threat and had banned multi-racial political parties in 1968was pleased with SASO's emergence, regarding it as a victory of apartheid thinking.

Attitude to liberalism and personal relations

The early focus of theBlack Consciousness Movement

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Af ...

(BCM) was on criticising anti-racist white liberals and liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

itself, accusing it of paternalism

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy against their will and is intended to promote their own good. It has been defended in a variety of contexts as a means of protecting individuals from significant harm, s ...

and being a "negative influence" on black Africans. In one of his first published articles, Biko stated that although he was "not sneering at the hite Hite or HITE may refer to:

*HiteJinro, a South Korean brewery

**Hite Brewery

*Hite (surname)

*Hite, California, former name of Hite Cove, California

*Hite, Utah

Historic Hite is a flooded ghost town at the north end of Lake Powell along the Co ...

liberals and their involvement" in the anti-apartheid movement, "one has to come to the painful conclusion that the hite Hite or HITE may refer to:

*HiteJinro, a South Korean brewery

**Hite Brewery

*Hite (surname)

*Hite, California, former name of Hite Cove, California

*Hite, Utah

Historic Hite is a flooded ghost town at the north end of Lake Powell along the Co ...

liberal is in fact appeasing his own conscience, or at best is eager to demonstrate his identification with the black people only insofar as it does not sever all ties with his relatives on his side of the colour line."

Biko and SASO were openly critical of NUSAS' protests against government policies. Biko argued that NUSAS merely sought to influence the white electorate; in his opinion, this electorate was not legitimate, and protests targeting a particular policy would be ineffective for the ultimate aim of dismantling the apartheid state. SASO regarded student marches, pickets, and strikes to be ineffective and stated it would withdraw from public forms of protest. It deliberately avoided open confrontation with the state until such a point when it had a sufficiently large institutional structure. Instead, SASO's focus was on establishing community projects and spreading Black Consciousness ideas among other black organisations and the wider black community. Despite this policy, in May 1972 it issued the Alice Declaration, in which it called for students to boycott lectures in response to the expulsion of SASO member Abram Onkgopotse Tiro from the University of the North after he made a speech criticising its administration. The Tiro incident convinced the government that SASO was a threat.

In Durban, Biko entered a relationship with a nurse, Nontsikelelo "Ntsiki" Mashalaba; they married at the King William's Town magistrates court in December 1970. Their first child, Nkosinathi, was born in 1971. Biko initially did well in his university studies, but his grades declined as he devoted increasing time to political activism. Six years after starting his degree, he found himself repeating his third year. In 1972, as a result of his poor academic performance, the University of Natal barred him from further study.

Black Consciousness activities and Biko's banning: 1971–1977

Black People's Convention

In August 1971, Biko attended a conference on "The Development of the African Community" in Edendale. There, a resolution was presented calling for the formation of the Black People's Convention (BPC), a vehicle for the promotion of Black Consciousness among the wider population. Biko voted in favour of the group's creation but expressed reservations about the lack of consultation with South Africa's Coloureds or Indians. A. Mayatula became the BPC's first president; Biko did not stand for any leadership positions. The group was formally launched in July 1972 inPietermaritzburg

Pietermaritzburg (; ) is the capital and second-largest city in the province of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa after Durban. It was named in 1838 and is currently governed by the Msunduzi Local Municipality. The town was named in Zulu after King ...

. By 1973, it had 41 branches and 4000 members, sharing much of its membership with SASO.

While the BPC was primarily political, Black Consciousness activists also established the Black Community Programmes (BCPs) to focus on improving healthcare and education and fostering black economic self-reliance. The BCPs had strong ecumenical links, being part-funded by a program on Christian action, established by the Christian Institute of Southern Africa and the South African Council of Churches. Additional funds came from the Anglo-American Corporation, the International University Exchange Fund, and Scandinavian churches. In 1972, the BCP hired Biko and Bokwe Mafuna, allowing Biko to continue his political and community work. In September 1972, Biko visited Kimberley

Kimberly or Kimberley may refer to:

Places and historical events

Australia

Queensland

* Kimberley, Queensland, a coastal locality in the Shire of Douglas

South Australia

* County of Kimberley, a cadastral unit in South Australia

Ta ...

, where he met the PAC founder and anti-apartheid activist Robert Sobukwe

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe Order for Meritorious Service, OMSG (5 December 1924 – 27 February 1978) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid revolutionary and founding member of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, ...

.

Biko's banning order in 1973 prevented him from working officially for the BCPs from which he had previously earned a small stipend, but he helped to set up a new BPC branch in Ginsberg, which held its first meeting in the church of a sympathetic white clergyman, David Russell. Establishing a more permanent headquarters in Leopold Street, the branch served as a base from which to form new BCPs; these included self-help schemes such as classes in literacy, dressmaking and health education. For Biko, community development was part of the process of infusing black people with a sense of pride and dignity. Near King William's Town, a BCP Zanempilo Clinic was established to serve as a healthcare centre catering for rural black people who would not otherwise have access to hospital facilities. He helped to revive the Ginsberg crèche, a daycare for children of working mothers, and establish a Ginsberg education fund to raise bursaries for promising local students. He helped establish Njwaxa Home Industries, a leather goods company providing jobs for local women. In 1975, he co-founded the Zimele Trust, a fund for the families of political prisoners.

Biko endorsed the unification of South Africa's black liberationist groupsamong them the BCM, PAC, and African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC)in order to concentrate their anti-apartheid efforts. To this end, he reached out to leading members of the ANC, PAC, and Unity Movement. His communications with the ANC were largely via Griffiths Mxenge, and plans were being made to smuggle him out of the country to meet Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and activist who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography Childhood

Oliver Tambo was ...

, a leading ANC figure. Biko's negotiations with the PAC were primarily through intermediaries who exchanged messages between him and Sobukwe; those with the Unity Movement were largely via Fikile Bam Fikile is a given name. Notable people with the name include:

* Fikile Khosa, Zambian footballer

* Fikile Magadlela (1952–2003), South African painter

*Fikile Mbalula

Fikile April Mbalula (born 8 April 1971) is a South African politician and ...

.

Banning order

By 1973, the government regarded Black Consciousness as a threat. It sought to disrupt Biko's activities, and in March 1973 placed a banning order on him. This prevented him from leaving the King William's Town magisterial district, prohibited him from speaking either in public or to more than one person at a time, barred his membership of political organisations, and forbade the media from quoting him. As a result, he returned to Ginsberg, living initially in his mother's house and later in his own residence. In December 1975, attempting to circumvent the restrictions of the banning order, the BPC declared Biko their honorary president. After Biko and other BCM leaders were banned, a new leadership arose, led by Muntu Myeza and Sathasivian Cooper, who were considered part of the Durban Moment. Myeza and Cooper organised a BCM demonstration to mark

In December 1975, attempting to circumvent the restrictions of the banning order, the BPC declared Biko their honorary president. After Biko and other BCM leaders were banned, a new leadership arose, led by Muntu Myeza and Sathasivian Cooper, who were considered part of the Durban Moment. Myeza and Cooper organised a BCM demonstration to mark Mozambique

Mozambique, officially the Republic of Mozambique, is a country located in Southeast Africa bordered by the Indian Ocean to the east, Tanzania to the north, Malawi and Zambia to the northwest, Zimbabwe to the west, and Eswatini and South Afr ...

's independence from Portuguese colonial rule in 1975. Biko disagreed with this action, correctly predicting that the government would use it to crack down on the BCM. The government arrested around 200 BCM activists, nine of whom were brought before the Supreme Court, accused of subversion by intent. The state claimed that Black Consciousness philosophy was likely to cause "racial confrontation" and therefore threatened public safety. Biko was called as a witness for the defence; he sought to refute the state's accusations by outlining the movement's aims and development. Ultimately, the accused were convicted and imprisoned on Robben Island

Robben Island () is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometres (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, north of Cape Town, South Africa. It takes its name from the Dutch language, Dutch word for seals (''robben''), hence the Dutch/Afrika ...

.

In 1973, Biko had enrolled for a law degree by correspondence from the University of South Africa. He passed several exams, but had not completed the degree at his time of death. His performance on the course was poor; he was absent from several exams and failed his Practical Afrikaans module. The state security services repeatedly sought to intimidate him; he received anonymous threatening phone calls, and gun shots were fired at his house. A group of young men calling themselves 'The Cubans' began guarding him from these attacks. The security services detained him four times, once for 101 days. With the ban preventing him from gaining employment, the strained economic situation impacted his marriage.

During his ban, Biko asked for a meeting with Donald Woods, the white liberal editor of the '' Daily Dispatch''. Under Woods' editorship, the newspaper had published articles criticising apartheid and the white-minority regime and had also given space to the views of various black groups, but not the BCM. Biko hoped to convince Woods to give the movement greater coverage and an outlet for its views. Woods was initially reticent, believing that Biko and the BCM advocated "for racial exclusivism in reverse". When he met Biko for the first time, Woods expressed his concern about the anti-white liberal sentiment of Biko's early writings. Biko acknowledged that his earlier "antiliberal" writings were "overkill", but said that he remained committed to the basic message contained within them.

Over the coming years the pair became close friends. Woods later related that, although he continued to have concerns about "the unavoidably racist aspects of Black Consciousness", it was "both a revelation and education" to socialise with blacks who had "psychologically emancipated attitudes". Biko also remained friends with another prominent white liberal, Duncan Innes, who served as NUSAS President in 1969; Innes later commented that Biko was "invaluable in helping me to understand black oppression, not only socially and politically, but also psychologically and intellectually". Biko's friendship with these white liberals came under criticism from some members of the BCM.

Death: 1977

Arrest and death

In 1977, Biko broke his banning order by travelling toCape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, hoping to meet Unity Movement leader Neville Alexander

Neville Edward Alexander OLS (22 October 1936 – 27 August 2012) was a proponent of a multilingual South Africa and a former revolutionary who spent ten years on Robben Island as a fellow prisoner of Nelson Mandela.

Early life

Alexander was ...

and deal with growing dissent in the Western Cape

The Western Cape ( ; , ) is a provinces of South Africa, province of South Africa, situated on the south-western coast of the country. It is the List of South African provinces by area, fourth largest of the nine provinces with an area of , an ...

branch of the BCM, which was dominated by Marxists

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, and ...

like Johnny Issel. Biko drove to the city with his friend Peter Jones on 17 August, but Alexander refused to meet with Biko, fearing that he was being monitored by the police. Biko and Jones drove back toward King William's Town, but on 18 August they were stopped at a police roadblock

A roadblock is a temporary installation set up to control or block traffic along a road. The reasons for one could be:

* Roadworks

*Temporary road closure during special events

* Police chase

*Robbery

* Sobriety checkpoint

* Protests

In peaceful ...

near Grahamstown

Makhanda, formerly known as Grahamstown, is a town of about 75,000 people in the Eastern Cape province of South Africa. It is situated about northeast of Gqeberha and southwest of East London. It is the largest town in the Makana Local Mun ...

. Biko was arrested for having violated the order restricting him to King William's Town. Unsubstantiated claims have been made that the security services were aware of Biko's trip to Cape Town and that the road block had been erected to catch him. Jones was also arrested at the roadblock; he was subsequently held without trial for 533 days, during which time he was interrogated on numerous occasions.

The security services took Biko to the Walmer police station in Port Elizabeth, where he was held naked in a cell with his legs in shackles. On 6 September, he was transferred from Walmer to room 619 of the security police headquarters in the Sanlam Building in central Port Elizabeth, where he was interrogated for 22 hours, handcuffed and in shackles, and chained to a grille. Exactly what happened has never been ascertained, but during the interrogation he was severely beaten by at least one of the ten security police officers. He suffered three brain lesions that resulted in a massive brain haemorrhage

Bleeding, hemorrhage, haemorrhage or blood loss, is blood escaping from the circulatory system from damaged blood vessels. Bleeding can occur internally, or externally either through a natural opening such as the mouth, nose, ear, urethra, vag ...

on 6 September. Following this incident, Biko's captors forced him to remain standing and shackled to the wall. The police later said that Biko had attacked one of them with a chair, forcing them to subdue him and place him in handcuffs and leg irons

Legcuffs are physical restraints used on the ankles of a person to allow walking only with a restricted stride and to prevent running and effective physical resistance. Frequently used alternative terms are leg cuffs, (leg/ankle) shackles, foo ...

.

Biko was examined by a doctor, Ivor Lang, who stated that there was no evidence of injury on Biko. Later scholarship has suggested Biko's injuries must have been obvious. He was then examined by two other doctors who, after a test showed blood cells to have entered Biko's spinal fluid, agreed that he should be transported to a prison hospital in Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

. On 11 September, police loaded him into the back of a Land Rover

Land Rover is a brand of predominantly four-wheel drive, off-road capable vehicles, owned by British multinational car manufacturer Jaguar Land Rover (JLR), since 2008 a subsidiary of India's Tata Motors. JLR builds Land Rovers in Brazil ...

, naked and manacled, and drove him to the hospital. There, Biko died alone in a cell on 12 September 1977. According to an autopsy

An autopsy (also referred to as post-mortem examination, obduction, necropsy, or autopsia cadaverum) is a surgical procedure that consists of a thorough examination of a corpse by dissection to determine the cause, mode, and manner of deat ...

, an "extensive brain injury" had caused "centralisation of the blood circulation to such an extent that there had been intravasal blood coagulation

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a thrombus, blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of co ...

, acute kidney failure

Kidney failure, also known as renal failure or end-stage renal disease (ESRD), is a medical condition in which the kidneys can no longer adequately filter waste products from the blood, functioning at less than 15% of normal levels. Kidney fa ...

, and uremia

Uremia is the condition of having high levels of urea in the blood. Urea is one of the primary components of urine. It can be defined as an excess in the blood of amino acid and protein metabolism end products, such as urea and creatinine, which ...

". He was the twenty-first person to die in a South African prison in twelve months, and the forty-sixth political detainee to die during interrogation since the government introduced laws permitting imprisonment without trial in 1963.

Response and investigation

News of Biko's death spread quickly across the world, and became symbolic of the abuses of the apartheid system. His death attracted more global attention than he had ever attained during his lifetime. Protest meetings were held in several cities; many were shocked that the security authorities would kill such a prominent dissident leader. Biko's Anglican funeral service, held on 25 September 1977 at King William's Town's Victoria Stadium, took five hours and was attended by around 20,000 people. The vast majority were black, but a few hundred whites also attended, including Biko's friends, such as Russell and Woods, and prominent progressive figures likeHelen Suzman

Helen Suzman, Order for Meritorious Service, OMSG, Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, DBE (née Gavronsky; 7 November 1917 – 1 January 2009) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and p ...

, Alex Boraine

Alexander Lionel Boraine (10 January 1931 – 5 December 2018) was a South African politician, minister, and anti-apartheid activist.

Early life

Alex Boraine was born in Cape Town and grew up in a poor white housing estate. He would leave hi ...

, and Zach de Beer. Foreign diplomats from thirteen nations were present, as was an Anglican delegation headed by Bishop Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop ...

. The event was later described as "the first mass political funeral in the country". Biko's coffin had been decorated with the motifs of a clenched black fist, the African continent, and the statement "One Azania, One Nation"; Azania was the name that many activists wanted South Africa to adopt post-apartheid. Biko was buried in the cemetery at Ginsberg. Two BCM-affiliated artists, Dikobé Ben Martins and Robin Holmes, produced a T-shirt marking the event; the design was banned the following year. Martins also created a commemorative poster for the funeral, the first in a tradition of funeral posters that proved popular throughout the 1980s.

hunger strike

A hunger strike is a method of non-violent resistance where participants fasting, fast as an act of political protest, usually with the objective of achieving a specific goal, such as a policy change. Hunger strikers that do not take fluids are ...

, a statement he later denied. His account was challenged by some of Biko's friends, including Woods, who said that Biko had told them that he would never kill himself in prison. Publicly, he stated that Biko had been plotting violence, a claim repeated in the pro-government press. South Africa's attorney general initially stated that no one would be prosecuted for Biko's death. Two weeks after the funeral, the government banned all Black Consciousness organisations, including the BCP, which had its assets seized.

Both domestic and international pressure called for a public inquest

An inquest is a judicial inquiry in common law jurisdictions, particularly one held to determine the cause of a person's death. Conducted by a judge, jury, or government official, an inquest may or may not require an autopsy carried out by a cor ...

to be held, to which the government agreed. It began in Pretoria's Old Synagogue courthouse in November 1977, and lasted for three weeks. Both the running of the inquest and the quality of evidence submitted came in for extensive criticism. An observer from the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, or simply the Lawyers' Committee, is an American civil rights organization founded in 1963 at the request of President John F. Kennedy.

When the Lawyers' Committee was created, its existence w ...

stated that the affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or ''deposition (law), deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by la ...

's statements were "sometimes redundant, sometimes inconsistent, frequently ambiguous"; David Napley described the police investigation of the incident as "perfunctory in the extreme". The security forces alleged that Biko had acted aggressively and had sustained his injuries in a scuffle, in which he had banged his head against the cell wall. The presiding magistrate accepted the security forces' account of events and refused to prosecute any of those involved.

The verdict was treated with scepticism by much of the international media and the US Government led by President Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

. On 2 February 1978, based on the evidence given at the inquest, the attorney general of the Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

stated that he would not prosecute the officers. After the inquest, Biko's family brought a civil case against the state; at the advice of their lawyers, they agreed to a settlement of R65,000 (US$

The United States dollar (Currency symbol, symbol: Dollar sign, $; ISO 4217, currency code: USD) is the official currency of the United States and International use of the U.S. dollar, several other countries. The Coinage Act of 1792 introdu ...

78,000) in July 1979. Shortly after the inquest, the South African Medical and Dental Council initiated proceedings against the medical professionals who had been entrusted with Biko's care; eight years later two of the medics were found guilty of improper conduct. The failure of the government-employed doctors to diagnose or treat Biko's injuries has been frequently cited as an example of a repressive state influencing medical practitioners' decisions, and Biko's death as evidence of the need for doctors to serve the needs of patients before those of the state.

After the abolition of apartheid and the establishment of a majority government in 1994, a Truth and Reconciliation Commission

A truth commission, also known as a truth and reconciliation commission or truth and justice commission, is an official body tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government (or, depending on the circumstances, non-state ac ...

was established to investigate past human-rights abuses. The commission made plans to investigate Biko's death, but his family petitioned against this on the grounds that the commission could grant amnesty

Amnesty () is defined as "A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet be ...

to those responsible, thereby preventing the family's right to justice and redress. In 1996, the Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ru ...

ruled against the family, allowing the investigation to proceed. Five police officers ( Harold Snyman, Gideon Nieuwoudt, Ruben Marx, Daantjie Siebert, and Johan Beneke) appeared before the commission and requested amnesty in return for information about the events surrounding Biko's death. In December 1998, the Commission refused amnesty to the five men; this was because their accounts were conflicting and thus deemed untruthful, and because Biko's killing had no clear political motive, but seemed to have been motivated by "ill-will or spite". In October 2003, South Africa's justice ministry announced that the five policemen would not be prosecuted because the statute of limitations

A statute of limitations, known in civil law systems as a prescriptive period, is a law passed by a legislative body to set the maximum time after an event within which legal proceedings may be initiated. ("Time for commencing proceedings") In ...

had elapsed and there was insufficient evidence to secure a prosecution.

Ideology

The ideas of the Black Consciousness Movement were not developed solely by Biko, but through lengthy discussions with other black students who were rejecting white liberalism. Biko was influenced by his reading of authors likeFrantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

, Malcolm X

Malcolm X (born Malcolm Little, later el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz; May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965) was an African American revolutionary, Islam in the United States, Muslim minister and human rights activist who was a prominent figur ...

, Léopold Sédar Senghor

Léopold Sédar Senghor ( , , ; 9 October 1906 – 20 December 2001) was a Senegalese politician, cultural theorist and poet who served as the first president of Senegal from 1960 to 1980.

Ideologically an African socialist, Senghor was one ...

, James Cone, and Paulo Freire

Paulo Reglus Neves Freire (19 September 1921 – 2 May 1997) was a Brazilian educator and philosopher whose work revolutionized global thought on education. He is best known for ''Pedagogy of the Oppressed'', in which he reimagines teaching ...

. The Martinique-born Fanon, in particular, has been cited as a profound influence over Biko's ideas about liberation. Biko's biographer Xolela Mangcu cautioned that it would be wrong to reduce Biko's thought to an interpretation of Fanon, and that the impact of "the political and intellectual history of the Eastern Cape" had to be appreciated too. Additional influences on Black Consciousness were the United States–based Black Power movement, and forms of Christianity like the activist-oriented black theology

Black theology, or black liberation theology, refers to a theological perspective which originated among African-American seminarians and scholars, and in some black churches in the United States and later in other parts of the world. It contex ...

.

Black Consciousness and empowerment

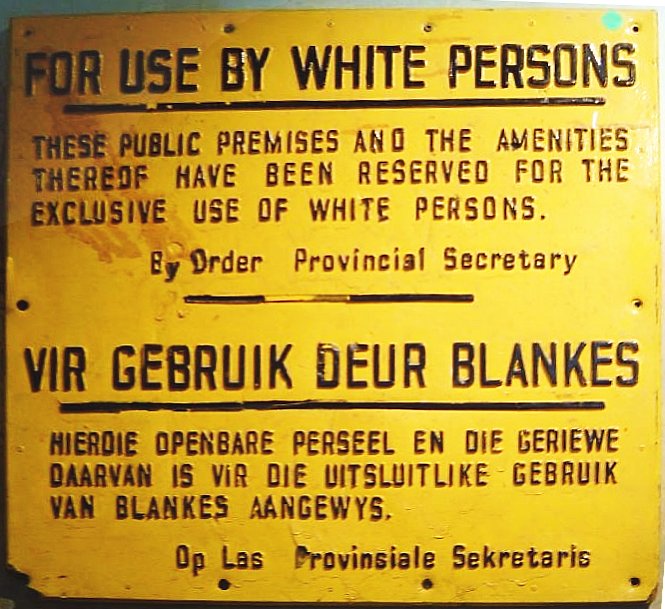

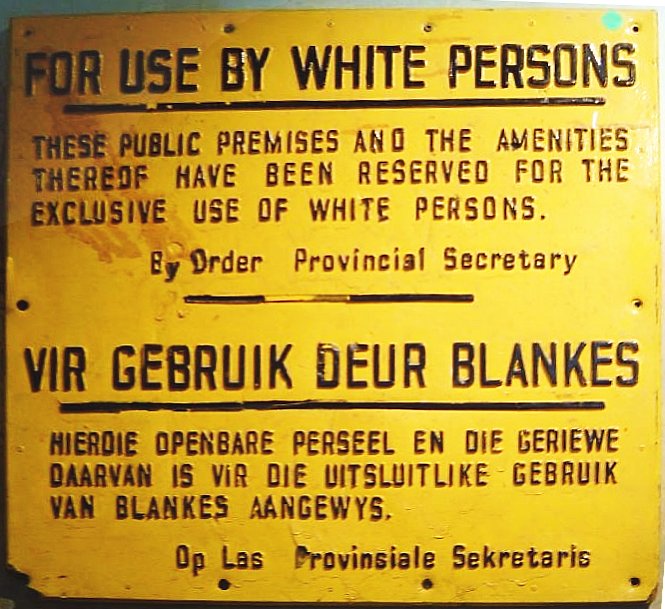

Biko rejected the apartheid government's division of South Africa's population into "whites" and "non-whites", a distinction that was marked on signs and buildings throughout the country. Building on Fanon's work, Biko regarded "non-white" as a negative category, defining people in terms of an absence of whiteness. In response, Biko replaced "non-white" with the category "black", which he regarded as being neither derivative nor negative. He defined blackness as a "mental attitude" rather than a "matter of pigmentation", referring to "blacks" as "those who are by law or tradition politically, economically and socially discriminated against as a group in the South African society" and who identify "themselves as a unit in the struggle towards the realization of their aspirations". In this way, he and the Black Consciousness Movement used "black" in reference not only to Bantu-speaking Africans but also to Coloureds and Indians, who together made up almost 90% of South Africa's population in the 1970s. Biko was not a Marxist and believed that it was oppression based on race, rather than class, which would be the main political motivation for change in South Africa. He argued that those on the "white left" often promoted a class-based analysis as a "defence mechanism... primarily because they want to detach us from anything relating to race. In case it has a rebound effect on them because they are white". Biko saw white racism in South Africa as the totality of the white power structure. He argued that under apartheid, white people not only participated in the oppression of black people but were also the main voices in opposition to that oppression. He thus argued that in dominating both the apartheid system and the anti-apartheid movement, white people totally controlled the political arena, leaving black people marginalised. He believed white people were able to dominate the anti-apartheid movement because of their access to resources, education, and privilege. He nevertheless thought that white South Africans were poorly suited to this role because they had not personally experienced the oppression that their black counterparts faced. Biko and his comrades regarded multi-racial anti-apartheid groups as unwittingly replicating the structure of apartheid because they contained whites in dominant positions of control. For this reason, Biko and the others did not participate in these multi-racial organisations. Instead, they called for an anti-apartheid programme that was controlled by black people. Although he called on sympathetic whites to reject any concept that they themselves could be spokespeople for the black majority, Biko nevertheless believed that they had a place in the anti-apartheid struggle, asking them to focus their efforts on convincing the wider white community on the inevitability of apartheid's fall. Biko clarified his position to Woods: "I don't reject liberalism as such or white liberals as such. I reject only the concept that black liberation can be achieved through the leadership of white liberals." He added that "thehite Hite or HITE may refer to:

*HiteJinro, a South Korean brewery

**Hite Brewery

*Hite (surname)

*Hite, California, former name of Hite Cove, California

*Hite, Utah

Historic Hite is a flooded ghost town at the north end of Lake Powell along the Co ...

liberal is no enemy, he's a friend – but for the moment he holds us back, offering a formula too gentle, too inadequate for our struggle".

Biko's approach to activism focused on psychological empowerment, and both he and the BCM saw their main purpose as combating the feeling of inferiority that most black South Africans experienced. Biko expressed dismay at how "the black man has become a shell, a shadow of man ... bearing the yoke of oppression with sheepish timidity", and stated that "the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed". He believed that blacks needed to affirm their own humanity by overcoming their fears and believing themselves worthy of freedom and its attendant responsibilities. He defined Black Consciousness as "an inward-looking process" that would "infuse people with pride and dignity". To promote this, the BCM adopted the slogan "Black is Beautiful".

One of the ways that Biko and the BCM sought to achieve psychological empowerment was through community development. Community projects were seen not only as a way to alleviate poverty in black communities but also as a means of transforming society psychologically, culturally, and economically. They would also help students to learn about the "daily struggles" of ordinary black people and to spread Black Consciousness ideas among the population. Among the projects that SASO set its members to conduct in the holidays were repairs to schools, house-building, and instructions on financial management and agricultural techniques. Healthcare was also a priority, with SASO members focusing on primary and preventative care.

Foreign and domestic relations

Biko opposed any collaboration with the apartheid government, such as the agreements that the Coloured and Indian communities made with the regime. In his view, theBantustan

A Bantustan (also known as a Bantu peoples, Bantu homeland, a Black people, black homeland, a Khoisan, black state or simply known as a homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party (South Africa), National Party administration of the ...

system was "the greatest single fraud ever invented by white politicians", stating that it was designed to divide the Bantu-speaking African population along tribal lines. He openly criticised the Zulu leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi (; 27 August 1928 – 9 September 2023) was a South African politician and Zulu people, Zulu prince who served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death in 2023. He ...

, stating that the latter's co-operation with the South African government " ilutedthe cause" of black liberation. He believed that those fighting apartheid in South Africa should link with anti-colonial struggles elsewhere in the world and with activists in the global African diaspora combating racial prejudice and discrimination. He also hoped that foreign countries would boycott South Africa's economy.

Biko believed that while apartheid and white-minority rule continued, "sporadic outbursts" of violence against the white minority were inevitable. He wanted to avoid violence, stating that "if at all possible, we want the revolution to be peaceful and reconciliatory". He noted that views on violence differed widely within the BCMwhich contained both pacifists

Pacifism is the opposition to war or violence. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaigner Émile Arnaud and adopted by other peace activists at the tenth Universal Peace Congress in Glasgow in 1901. A related term is ''a ...

and believers in violent revolutionalthough the group had agreed to operate peacefully, and unlike the PAC and ANC, had no armed wing.

A staunch anti-imperialist

Anti-imperialism in political science and international relations is opposition to imperialism or neocolonialism. Anti-imperialist sentiment typically manifests as a political principle in independence struggles against intervention or influenc ...

, Biko saw the South African situation as a "microcosm" of the broader "black–white power struggle" which manifests as "the global confrontation between the Third World

The term Third World arose during the Cold War to define countries that remained non-aligned with either NATO or the Warsaw Pact. The United States, Canada, Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the Southern Cone, NATO, Western European countries and oth ...

and the rich white nations of the world". He was suspicious of the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

's motives in supporting African liberation movements, relating that "Russia is as imperialistic as America", although he acknowledged that "in the eyes of the Third World they have a cleaner slate". He also acknowledged that the material assistance provided by the Soviets was "more valuable" to the anti-apartheid cause than the "speeches and wrist-slapping" provided by Western governments. He was cautious of the possibility of a post-apartheid South Africa getting caught up in the imperialist Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

rivalries of the United States and the Soviet Union.

On a post-apartheid society

Biko hoped that a future socialist South Africa could become a completely non-racial society, with people of all ethnic backgrounds living peacefully together in a "joint culture" that combined the best of all communities. He did not support guarantees of minority rights, believing that doing so would continue to recognise divisions along racial lines. Instead he supported aone person, one vote

"One man, one vote" or "one vote, one value" is a slogan used to advocate for the principle of equal representation in voting. This slogan is used by advocates of democracy and political equality, especially with regard to electoral reforms like ...

system. Initially arguing that one-party state

A one-party state, single-party state, one-party system or single-party system is a governance structure in which only a single political party controls the ruling system. In a one-party state, all opposition parties are either outlawed or en ...

s were appropriate for Africa, he developed a more positive view of multi-party system

In political science, a multi-party system is a political system where more than two meaningfully-distinct political parties regularly run for office and win elections. Multi-party systems tend to be more common in countries using proportional ...

s after conversations with Woods. He saw individual liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

as desirable, but regarded it as a lesser priority than access to food, employment, and social security.

Biko was neither a communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

nor capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

. Described as a proponent of African socialism

African socialism is a distinct variant of socialist theory developed in post-colonial Africa during the mid-20th century. As a shared ideological project among several African thinkers over the decades, it encompasses a variety of competing inte ...

, he called for "a socialist solution that is an authentic expression of black communalism". This idea was derided by some of his Marxist contemporaries, but later found parallels in the ideas of the Mexican Zapatistas. Noting that there was significant inequality in the distribution of wealth in South Africa, Biko believed that a socialist society

The Socialist Society was founded in 1981 by a group of British socialists, including Raymond Williams and Ralph Miliband, who founded it as an organisation devoted to socialist education and research, linking the left of the British Labour Part ...

was necessary to ensure social justice. In his view, this required a move towards a mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

that allowed private enterprise

A privately held company (or simply a private company) is a company whose Stock, shares and related rights or obligations are not offered for public subscription or publicly negotiated in their respective listed markets. Instead, the Private equi ...

but in which all land was owned by the state and in which state industries played a significant part in forestry, mining, and commerce. He believed that, if post-apartheid South Africa remained capitalist, some black people would join the bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

but inequality and poverty would remain. As he put it, if South Africa transitioned to proportional democracy without socialist economic reforms, then "it would not change the position of ''economic'' oppression of the blacks".

In conversation with Woods, Biko insisted that the BCM would not degenerate into anti-white hatred "because it isn't a negative, hating thing. It's a positive black self-confidence thing involving no hatred of anyone". He acknowledged that a "fringe element" may retain "anti-white bitterness"; he added: "we'll do what we can to restrain that, but frankly it's not one of our top priorities or one of our major concerns. Our main concern is the liberation of the blacks." Elsewhere, Biko argued that it was the responsibility of a vanguard movement to ensure that, in a post-apartheid society, the black majority would not seek vengeance upon the white minority. He stated that this would require an education of the black population in order to teach them how to live in a non-racial society.

Personal life and personality

Tall and slim in his youth, by his twenties Biko was over six feet tall, with the "bulky build of a heavyweight boxer carrying more weight than when in peak condition", according to Woods. His friends regarded him as "handsome, fearless, a brilliant thinker". Woods saw him as "unusually gifted ... His quick brain, superb articulation of ideas and sheer mental force were highly impressive." According to Biko's friend Trudi Thomas, with Biko "you had a remarkable sense of being in the presence of a great mind". Woods felt that Biko "could enable one to share his vision" with "an economy of words" because "he seemed to communicate ideas through extraverbal media – almost psychically." Biko exhibited what Woods referred to as "a new style of leadership", never proclaiming himself to be a leader and discouraging anycult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

from growing up around him. Other activists did regard him as a leader and often deferred to him at meetings. When engaged in conversations, he displayed an interest in listening and often drew out the thoughts of others.

Biko and many others in his activist circle had an antipathy toward luxury items because most South African blacks could not afford them. He owned few clothes and dressed in a low-key manner. He had a large record collection and particularly liked gumba. He enjoyed parties, and according to his biographer Linda Wilson, he often drank substantial quantities of alcohol. Religion did not play a central role in his life. He was often critical of the established Christian churches, but remained a believer in God and found meaning in the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

s. Woods described him as "not conventionally religious, although he had genuine religious feeling in broad terms". Mangcu noted that Biko was critical of organised religion and denominationalism and that he was "at best an unconventional Christian".

The Nationalist government portrayed Biko as a hater of whites, but he had several close white friends, and both Woods and Wilson insisted that he was not a racist. Woods related that Biko "simply wasn't a hater of people", and that he did not even hate prominent National Party politicians like B. J. Vorster

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster (; 13 December 1915 – 10 September 1983), better known as John Vorster, was a South African politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state president of So ...

and Andries Treurnicht, instead hating their ideas. It was rare and uncharacteristic of him to display any rage, and was rare for him to tell people about his doubts and inner misgivings, reserving those for a small number of confidants.

Biko never addressed questions of gender

Gender is the range of social, psychological, cultural, and behavioral aspects of being a man (or boy), woman (or girl), or third gender. Although gender often corresponds to sex, a transgender person may identify with a gender other tha ...

and sexism

Sexism is prejudice or discrimination based on one's sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but primarily affects women and girls. It has been linked to gender roles and stereotypes, and may include the belief that one sex or gender is int ...

in his politics. The sexism was evident in many ways, according to Mamphela Ramphele, a BCM activist and doctor at the Zanempilo Clinic, including that women tended to be given responsibility for the cleaning and catering at functions. "There was no way you could think of Steve making a cup of tea or whatever for himself", another activist said. Feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

was viewed as irrelevant "bra-burning". Surrounded by women who cared about him, Biko developed a reputation as a womaniser, something that Woods described as "well earned". He displayed no racial prejudice, sleeping with both black and white women. At NUSAS, he and his friends competed to see who could have sex with the most female delegates. Responding to this behaviour, the NUSAS general secretary Sheila Lapinsky accused Biko of sexism, to which he responded: "Don't worry about my sexism. What about your white racist friends in NUSAS?" Sobukwe also admonished Biko for his womanising, believing that it set a bad example to other activists.

Biko married Ntsiki Mashalaba in December 1970. They had two children together: Nkosinathi, born in 1971, and Samora, born in 1975. Biko's wife chose the name Nkosinathi ("The Lord is with us"), and Biko named their second child after the Mozambican revolutionary leader Samora Machel

Samora Moisés Machel (29 September 1933 – 19 October 1986) was a Mozambique, Mozambican politician and revolutionary. A Socialism, socialist in the tradition of Marxism–Leninism, he served as the first President of Mozambique from the coun ...

. Angered by her husband's serial adultery, Mashalaba ultimately moved out of their home, and by the time of his death, she had begun divorce proceedings. Biko had also begun an extra-marital relationship with Mamphela Ramphele. In 1974, they had a daughter, Lerato, who died after two months. A son, Hlumelo, was born to Ramphele in 1978, after Biko's death. Biko was also in a relationship with Lorrain Tabane; they had a child named Motlatsi in 1977.

Legacy

Influence

Biko is viewed as the "father" of the Black Consciousness Movement and the anti-apartheid movement's first icon.

Biko is viewed as the "father" of the Black Consciousness Movement and the anti-apartheid movement's first icon. Nelson Mandela