Stefan Bandera on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

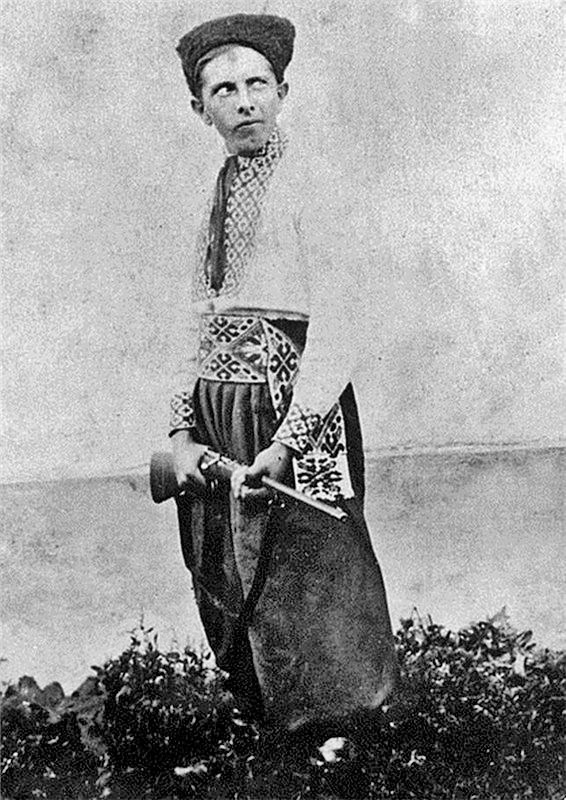

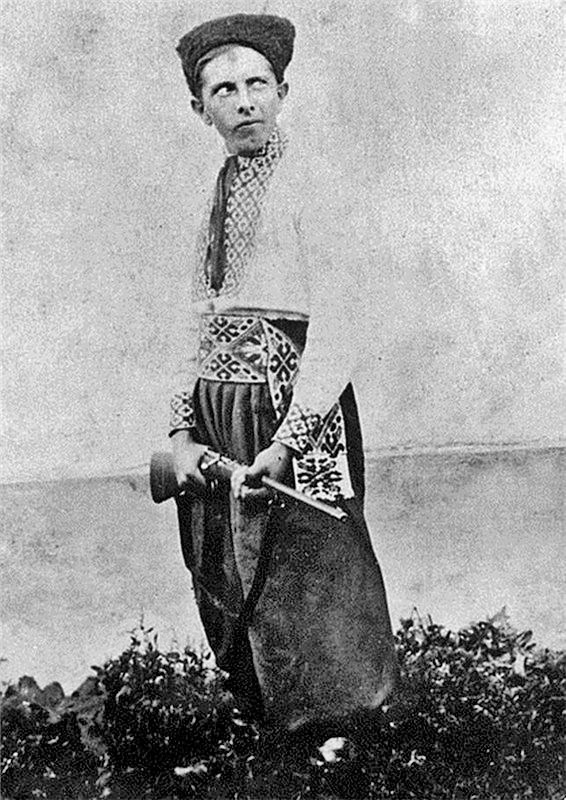

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera (, ; ; 1 January 1909 – 15 October 1959) was a Ukrainian

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in  After the

After the

Bandera associated himself with a variety of Ukrainian organizations during his time in high school, particularly

Bandera associated himself with a variety of Ukrainian organizations during his time in high school, particularly

After the trials, Bandera became renowned and admired among Ukrainians in Poland as a symbol of a revolutionary who fought for Ukrainian independence. While in prison Bandera was "to some extent detached from OUN discourses" but not completely isolated from the global political debates of the late 1930s thanks to Ukrainian and other newspaper subscriptions delivered to his cell.

After the trials, Bandera became renowned and admired among Ukrainians in Poland as a symbol of a revolutionary who fought for Ukrainian independence. While in prison Bandera was "to some extent detached from OUN discourses" but not completely isolated from the global political debates of the late 1930s thanks to Ukrainian and other newspaper subscriptions delivered to his cell.

In his 2006 article discussing "the reinterpretations of andera'scareer", historian David R. Marples, who specialises in the history of this area of Eastern Europe, stated that "the impact of Bandera lies less in his own political life and beliefs than in the events enacted in his name, or the conflicts that arose between his supporters and their enemies." According to ''

In his 2006 article discussing "the reinterpretations of andera'scareer", historian David R. Marples, who specialises in the history of this area of Eastern Europe, stated that "the impact of Bandera lies less in his own political life and beliefs than in the events enacted in his name, or the conflicts that arose between his supporters and their enemies." According to ''

,320 Lenin monuments decommunized, 4 erected to Bandera ''

"With 50 Thousand renamed Objets Place Names, Only 34 Are Named After Bandera"

,

''

''

''

residential Decree 'On conferring the title of Hero of Ukraine on S. Bandera' passed to the decision of the court . President.gov.ua. Retrieved 16 January 2011. This was done after a cassation appeal filed against the ruling by Donetsk District Administrative Court was rejected by the

far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

leader of the radical militant wing of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; ) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established on February 2, 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups. ...

, the OUN-B.

Bandera was born in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, in Galicia, into the family of a priest of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) is a Major archiepiscopal church, major archiepiscopal ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic church that is based in Ukraine. As a particular church of the Cathol ...

, and grew up in Poland. Involved in nationalist organizations from a young age, he joined the Ukrainian Military Organization

The Ukrainian Military Organization (), was a Ukrainian paramilitary body, engaged in terrorism (especially in Poland) during the interwar period.

It was formed after the occupation of Ukraine by Soviet Russia following the Ukrainian–Soviet ...

in 1924. In 1931, he became head of propaganda of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; ) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established on February 2, 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups ...

(OUN), and later became head of the OUN for Poland in 1932. In 1934, he organized the assassination of the Polish interior minister, Bronisław Pieracki

Bronisław Wilhelm Pieracki (28 May 1895 – 15 June 1934) was a Polish military officer and politician.

Life

As a member of the Polish Legions in World War I, Pieracki took part in the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919). He later supported J� ...

, and was sentenced to death after being convicted of terrorism, subsequently commuted to life imprisonment.

Bandera was freed from prison in 1939 following the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, and moved to Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

. In 1940, he became head of the radical faction of the OUN, the OUN-B. On 22 June 1941, the same day as Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

, the German invasion of the Soviet Union, he formed the Ukrainian National Committee. The head of the Committee, Yaroslav Stetsko

Yaroslav Semenovych Stetsko (; 19 January 1912 – 5 July 1986) was a Ukrainian politician, writer and ideologist who served as the leader of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B, from 1941 until his ...

, announced the creation of a Ukrainian state on 30 June 1941, in German-captured Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

. The proclamation pledged to work with Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. The Germans disapproved of the proclamation, and for his refusal to rescind the decree, Bandera was arrested by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

. He was released in September 1944 by the Germans in hope that he could fight the Soviet advance. Bandera negotiated with the Nazis to create the Ukrainian National Army

The Ukrainian National Army (, abbreviated , UNA) was a World War II Ukrainian military group, created on March 17, 1945, in the town of Weimar, Nazi Germany, and subordinate to Ukrainian National Committee.

History

The army, formed on April 1 ...

and the Ukrainian National Committee

The Ukrainian National Committee ( ) was a Ukrainian political structure created under the leadership of Pavlo Shandruk, on March 17 (or March 12), 1945 in Weimar, Nazi Germany, nearly two months before the German Instrument of Surrender, with the ...

in March 1945. After the war, Bandera settled with his family in West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

. In 1959, Bandera was assassinated by a KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

agent in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

.

Bandera remains a highly controversial figure in Ukraine. Many Ukrainians hail him as an example, or as a martyred liberation fighter, while other Ukrainians, particularly in the south and east, condemn him as a fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

, or Nazi collaborator

In World War II, many governments, organizations and individuals Collaborationism, collaborated with the Axis powers, "out of conviction, desperation, or under coercion". Nationalists sometimes welcomed German or Italian troops they believed wou ...

, whose followers, called Banderites

A Banderite or Banderovite (; ; ; ) is a name for the members of the OUN-B, a faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. The term, used from late 1940 onward, derives from the name of Stepan Bandera (1909–1959), the ultranational ...

, were responsible for massacres of Polish and Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

civilians during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. On 22 January 2010, Viktor Yushchenko

Viktor Andriiovych Yushchenko (, ; born 23 February 1954) is a Ukrainian politician who was the third president of Ukraine from 23 January 2005 to 25 February 2010. He aimed to orient Ukraine towards Western world, the West, European Union, and N ...

, the president of Ukraine

The president of Ukraine (, ) is the head of state of Ukraine. The president represents the nation in international relations, administers the foreign political activity of the state, conducts negotiations and concludes international treaties. ...

, awarded Bandera the posthumous title of Hero of Ukraine

A Hero of Ukraine (HOU; ) is the highest national decoration that can be conferred upon an individual citizen by the president of Ukraine.

The decoration was created in 1998 by President Leonid Kuchma. As of 6 June 2025, the total number of re ...

, which was widely condemned. The award was annulled in 2011 given that Stepan Bandera was never a Ukrainian citizen. The controversy regarding Bandera's legacy gained further prominence following the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

in 2022.

Biography

Early life and education

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in

Stepan Andriyovych Bandera was born on 1 January 1909 in Staryi Uhryniv

Staryi Uhryniv (, Polish language, Polish: Uhrynów Stary) is a village in Kalush Raion, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, western Ukraine. The local government is administered by Serednouhrynivska village council. It belongs to Novytsia rural hromada, one ...

, in the region of Galicia in Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

, to Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church

The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) is a Major archiepiscopal church, major archiepiscopal ''sui iuris'' ("autonomous") Eastern Catholic Churches, Eastern Catholic church that is based in Ukraine. As a particular church of the Cathol ...

priest Andriy Bandera (1882–1941) and Myroslava Głodzińska (1890–1921). Bandera had seven siblings, three sisters and four brothers. Bandera's younger brothers included Oleksandr, who earned a doctorate in political economy at the University of Rome, and Vasyl, who finished a degree in philosophy at the University of Lviv

The Ivan Franko National University of Lviv (named after Ivan Franko, ) is a state-sponsored university in Lviv, Ukraine. Since 1940 the university is named after Ukrainian poet Ivan Franko.

The university is the oldest institution of highe ...

.

Bandera grew up in a patriotic and religious household. He did not attend primary school due to World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

and was taught at home by his parents. At a young age, Bandera was undersized and slim. He sang in a choir, played guitar and mandolin, enjoyed hiking, jogging, swimming, ice skating, basketball and chess.

After the

After the dissolution of Austria-Hungary

The dissolution of Austria-Hungary was a major political event that occurred as a result of the growth of internal social contradictions and the separation of different parts of Austria-Hungary. The more immediate reasons for the collapse of the ...

in the wake of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia (; ; ) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv Oblast, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil Oblast, Ternopil), having also essential historic importance in Poland.

Galicia ( ...

briefly became part of the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (; West Ukrainian People's Republic#Name, see other names) was a short-lived state that controlled most of Eastern Galicia from November 1918 to July 1919. It included major cities of Lviv, Ternopil, Kolom ...

. Bandera's father, who joined the Ukrainian Galician Army

The Ukrainian Galician Army ( UGA; ), was the combined military of the West Ukrainian People's Republic during and after the Polish-Ukrainian War. It was called the "Galician army" initially. Dissatisfied with the alliance of Ukraine and Polan ...

as a chaplain, was active in the nationalist movement preceding the Polish–Ukrainian War

The Polish–Ukrainian War, from November 1918 to July 1919, was a conflict between the Second Polish Republic and Ukrainian forces (both the West Ukrainian People's Republic and the Ukrainian People's Republic).

The conflict had its roots in ...

, which was fought between November 1918 to July 1919 and ended with Ukrainian defeat and incorporation of Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia (; ; ) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv Oblast, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil Oblast, Ternopil), having also essential historic importance in Poland.

Galicia ( ...

into Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

.

Mykola Mikhnovsky

Mykola Ivanovych Mikhnovsky (; – 3 May 1924) was a Ukrainian independence activist, lawyer and journalist who was one of the early leaders of the Ukrainian nationalist movement in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mikhnovsky was the a ...

's 1900 publication, ''Independent Ukraine

Independent Ukraine (Ukrainian: Самостійна Україна) is a political pamphlet published in 1900 by Mykola Mikhnovsky in support of the Revolutionary Ukrainian Party

The Revolutionary Ukrainian Party () was a Ukrainian political pa ...

'', influenced Bandera greatly. After graduating from a Ukrainian high school in Stryi

Stryi (, ; ) is a city in Lviv Oblast, western Ukraine. It is located in the left bank of the Stryi (river), Stryi River, approximately south of Lviv in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains. It serves as the administrative center of Stryi R ...

in 1927, where he was engaged in a number of youth organizations, Bandera planned to attend the Husbandry Academy in Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, but he either did not get a passport or the Academy notified him that it was closed. In 1928, Bandera enrolled in the agronomy

Agronomy is the science and technology of producing and using plants by agriculture for food, fuel, fiber, chemicals, recreation, or land conservation. Agronomy has come to include research of plant genetics, plant physiology, meteorology, and ...

program at the Politechnika Lwowska in its branch in Dubliany, but never completed his studies due to his political activities and arrests.

Early activities

Bandera associated himself with a variety of Ukrainian organizations during his time in high school, particularly

Bandera associated himself with a variety of Ukrainian organizations during his time in high school, particularly Plast

The Plast National Scout Organization of Ukraine (), commonly called Ukrainian Plast or simply , is the largest Scouting organization in Ukraine.

History

First Era: 1911–1920

Plast was founded in Lviv (Lwów, Lemberg), Austro-Hungarian Ga ...

, Sokil, and Organization of the Upper Grades of the Ukrainian High Schools (OVKUH). In 1927 Bandera joined Ukrainian Military Organization

The Ukrainian Military Organization (), was a Ukrainian paramilitary body, engaged in terrorism (especially in Poland) during the interwar period.

It was formed after the occupation of Ukraine by Soviet Russia following the Ukrainian–Soviet ...

(UVO). In February 1929 he joined Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; ) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established on February 2, 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups ...

(OUN). Bandera was drawn into national activity by , one of the leaders of the Ukrainian youth movement.

During his studies, he devoted his efforts to underground and nationalist activities, for which he was arrested several times. The first time was on 14 November 1928, for illegally celebrating the 10th anniversary of the ZUNR

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (; see other names) was a short-lived state that controlled most of Eastern Galicia from November 1918 to July 1919. It included major cities of Lviv, Ternopil, Kolomyia, Drohobych, Boryslav, Stanyslaviv ...

; in 1930 with his brother Andrii; and in 1932-33 as many as six times. Between March and June 1932, he spent three months in prison in connection with the investigation of the assassination of by .

In the early 1930s, in response to attacks perpetrated by Ukrainian nationalists, Polish authorities carried out the pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia

The Pacification of Ukrainians in Eastern Galicia was a punitive action against the Ukrainians in Galicia, carried out by police and military of the Second Polish Republic from September until November 1930 in reaction to a wave of sabotage and ...

against the Ukrainian minority. This resulted in destroyed property and mass detentions, and took place in southeastern voivodeship

A voivodeship ( ) or voivodate is the area administered by a voivode (governor) in several countries of central and eastern Europe. Voivodeships have existed since medieval times and the area of extent of voivodeship resembles that of a duchy in ...

s of the Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

.

Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists

Bandera joined OUN in 1929, and quickly climbed through the ranks, thanks to the support of Okhrymovych, becoming in 1930 the head of a section distributing OUN propaganda in Eastern Galicia. A year later, he became director of propaganda for the whole OUN. After Okhrymovych's death and the flight from Poland of his successor Ivan Habrusevych in 1931, he became the leading candidate to become head of the homeland executive. But due to the fact that he was in detention at the time, he was unable to assume this function, and upon his release he became deputy toBohdan Kordiuk Bohdan may refer to:

*Bohdan (name), a Slavic masculine name

*Bohdan, Podlaskie Voivodeship, a village in Poland

*Bohdan, Zakarpattia Oblast

Bohdan (; ) is a village in Rakhiv Raion, Zakarpattia Oblast, Ukraine. It is the centre of Bohdan r ...

, who assumed this function. After the failure of the , Kordiuk had to step down and Bandera took over de facto his function, which was sanctioned at a conference in Berlin on 3–6 June 1933.

On 29 August 1931, Polish politician Tadeusz Hołówko

Tadeusz Ludwik Hołówko (September 17, 1889 – August 29, 1931), codename ''Kirgiz'', was an interwar Polish politician, diplomat and author of many articles and books.

He was most notable for his moderate stance on the "Ukrainian problem" fac ...

was assassinated by two members of the OUN Vasyl Bilas and Dmytro Danylyshyn. Both were sentenced to death. Bandera-led OUN propaganda made them martyrs and ordered Ukrainian priests in Lviv and elsewhere to ring bells on the day of their execution.

Since 1932 Bandera was assistant chief of OUN and around that time controlled several "warrior units" in Poland in places such as the Free City of Danzig

The Free City of Danzig (; ) was a city-state under the protection and oversight of the League of Nations between 1920 and 1939, consisting of the Baltic Sea port of Danzig (now Gdańsk, Poland) and nearly 200 other small localities in the surrou ...

(Wolne Miasto Gdańsk), Drohobycz

Drohobych ( ; ; ) is a city in the south of Lviv Oblast, Ukraine. It is the administrative center of Drohobych Raion and hosts the administration of Drohobych urban hromada, one of the hromadas of Ukraine. In 1939–1941 and 1944–1959 it was ...

, Lwów

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, Stanisławów, Brzezany, and Truskawiec. Bandera collaborated closely with Richard Yary, who would later side with Bandera and help him form OUN-B.

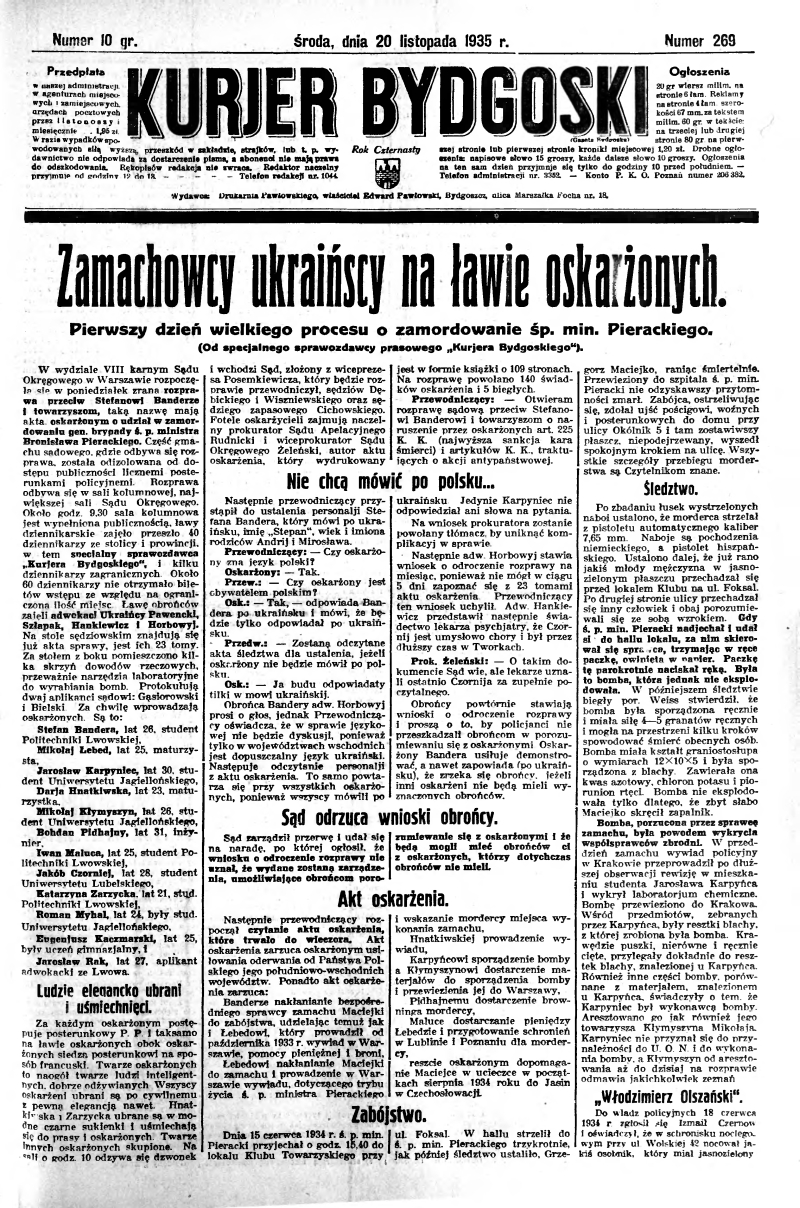

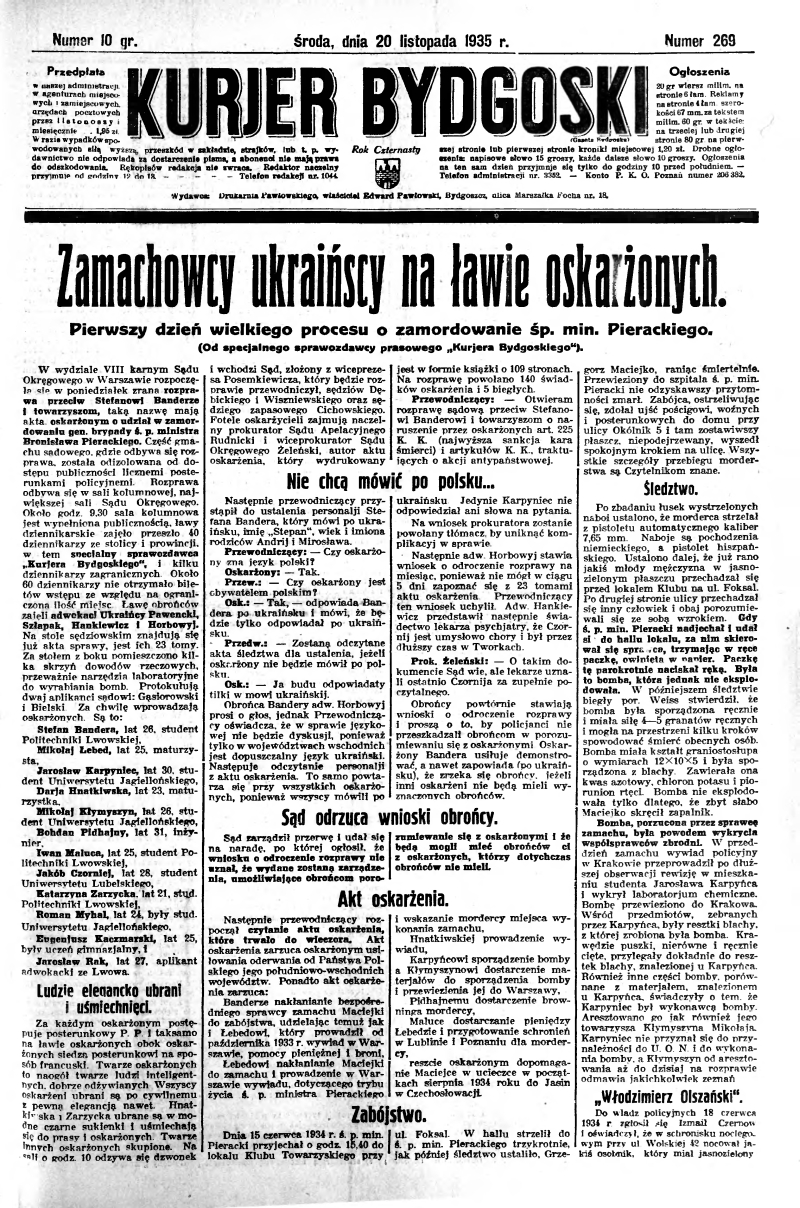

On Bandera's orders OUN began a campaign of terrorist acts, such as attacks on post-offices, bomb-throwing at Polish exhibitions and murders of policemen to mass campaigns against Polish tobacco and alcohol monopolies and against the denationalization of Ukrainian youth. In 1934 Bandera was arrested in Lwów

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

and tried twice: first, concerning involvement in a plot to assassinate the minister of internal affairs, Bronisław Pieracki

Bronisław Wilhelm Pieracki (28 May 1895 – 15 June 1934) was a Polish military officer and politician.

Life

As a member of the Polish Legions in World War I, Pieracki took part in the Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919). He later supported J� ...

, and second at a general trial of OUN executives. He was convicted of terrorism and sentenced to death. The death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

.

After the trials, Bandera became renowned and admired among Ukrainians in Poland as a symbol of a revolutionary who fought for Ukrainian independence. While in prison Bandera was "to some extent detached from OUN discourses" but not completely isolated from the global political debates of the late 1930s thanks to Ukrainian and other newspaper subscriptions delivered to his cell.

After the trials, Bandera became renowned and admired among Ukrainians in Poland as a symbol of a revolutionary who fought for Ukrainian independence. While in prison Bandera was "to some extent detached from OUN discourses" but not completely isolated from the global political debates of the late 1930s thanks to Ukrainian and other newspaper subscriptions delivered to his cell.

World War II

BeforeWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

the territory of today's Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

was split between Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

, the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

and Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. Prior to the 1939 invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, German military intelligence recruited OUN members into the Bergbauernhilfe unit and smuggled Ukrainian nationalists into Poland in order to erode Polish defences by conducting a terror campaign directed at Polish farmers and Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

. OUN leaders Andriy Melnyk (code name Consul I) and Bandera (code name Consul II) both served as agents of the Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

military intelligence Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

Second Department. Their goal was to run diversion activities after Germany's attack on the Soviet Union. This information is part of the testimony that Abwehr Colonel Erwin Stolze gave on 25 December 1945 and submitted to the Nuremberg trials, with a request to be admitted as evidence.

Bandera was freed from Brest (Brześć) Prison in Eastern Poland in early September 1939, as a result of the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

. There are differing accounts of the circumstances of his release. Soon thereafter Eastern Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union. Upon release from prison, Bandera moved first to Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, but after realising it would be occupied by the Soviets, Bandera together with other OUN members, moved to Kraków

, officially the Royal Capital City of Kraków, is the List of cities and towns in Poland, second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city has a population of 804,237 ...

, the capital of Germany's occupational General Government

The General Government (, ; ; ), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia and the Soviet ...

. where, according to Tadeusz Piotrowski, he established close connections with the German Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

and Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

. There, he also came in contact with the leader of the OUN, Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk

Andriy Atanasovych Melnyk (; 12 December 1890 – 1 November 1964) was a Ukrainian military and political leader best known for leading the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists from 1939 onwards and later the Melnykites (OUN-M) following a spl ...

. In 1940, the political differences and expectations between the two leaders caused the OUN to split into two factions, OUN-B and OUN-M (Banderite

A Banderite or Banderovite (; ; ; ) is a name for the members of the OUN-B, a faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. The term, used from late 1940 onward, derives from the name of Stepan Bandera (1909–1959), the ultranation ...

s and Melnykites) each one claiming legitimacy.

The factions differed in ideology, strategy and tactics: the OUN-M

Melnykites () is a colloquial name for members of the OUN-M or OUN(m), a faction of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) that arose out of a split with the Banderite faction in 1940. The term derives from the name of Andriy Melnyk ...

faction led by Melnyk preached a more conservative approach to nation-building, while the OUN-B

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; ) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established on February 2, 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups. ...

faction, led by Bandera, supported a revolutionary approach; however, both factions exhibited similar levels of radical nationalism, fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, xenophobia and violence. The vast majority of young OUN members joined Bandera's faction. OUN-B was devoted to the independence of Ukraine, as a single-party fascist totalitarian state free of national minorities. It was later implicated in the Holocaust

The Holocaust (), known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as the (), was the genocide of History of the Jews in Europe, European Jews during World War II. From 1941 to 1945, Nazi Germany and Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy ...

.

Before the independence proclamation of 30 June 1941, Bandera oversaw the formation of so-called "Mobile Groups" (), which were small (5–15 members) groups of OUN-B members who would travel from General Government

The General Government (, ; ; ), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovak Republic (1939–1945), Slovakia and the Soviet ...

to Western Ukraine and, after a German advance to Eastern Ukraine, encourage support for the OUN-B and establish local authorities run by OUN-B activists.ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х ч Ін-т історії України НАН України К. 2006 In total, approximately 7,000 people participated in these mobile groups, and they found followers among a wide circle of intellectuals, such as Ivan Bahriany, Vasyl Barka

Vasyl Barka (; real name — ''Vasyl Kostiantynovych Ocheret'' (), another pseudo — ''Ivan Vershyna'' (); 16 July 1908, – 11 April 2003, Glen Spey) was an American-residing Ukrainian poet, writer, literary critic, and translator.

...

, Hryhorii Vashchenko and many others.

In spring 1941, Bandera held meetings with the heads of Germany's intelligence, regarding the formation of " Nachtigall" and "Roland

Roland (; ; or ''Rotholandus''; or ''Rolando''; died 15 August 778) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the Matter of France. The historical Roland was mil ...

" Battalions. In the spring of that year, the OUN received 2.5 million marks for subversive activities inside the Soviet Union.I. K. Patrylyak (2004). ''Військова діяльність ОУН(Б) у 1940—1942 роках'' 'Military activity of the OUN-B in 1940–1942'' Kyiv: Institute of Ukrainian History, Shevchenko University Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

and Abwehr

The (German language, German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', though the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context) ) was the German military intelligence , military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ...

officials protected Bandera's followers, as both organizations intended to use them for their own purposes.

On 30 June 1941, with the arrival of Nazi troops in Ukraine, the OUN-B unilaterally declared an independent Ukrainian state ("Act of Renewal of Ukrainian Statehood"). The proclamation

''The Proclamation'' is the debut studio album by American jazz saxophonist Kamasi Washington.

Track listing

Based on:

#The Conception – 15:35

#The Bombshell's Waltz – 12:01

#Fair As Equal – 8:32

#Whacha Say – 4:56

#The Rhythm Changes ...

pledged a cooperation of the new Ukrainian state with Nazi Germany under the leadership of Hitler. The declaration was accompanied by violent pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s. There is no evidence that Bandera actively supported or participated in the Lviv pogroms or acts of violence against Jewish and Polish civilians, but he was well informed about the violence and was "unable or unwilling to instruct Ukrainian nationalist military troops (as Nachtigall, Roland and UPA) to protect vulnerable minorities under their control". As German historian Olaf Glöckner writes, Bandera "failed to manage this problem (ethnic and anti-Semitic hatred) inside his forces, just like Symon Petljura failed 25 years before him."

OUN(b) leaders' expectation that the Nazi regime would post-factum recognize an independent fascist Ukraine as an Axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

ally proved to be wrong. German authorities requested the declaration be withdrawn, Stetsko and Bandera refused. The Germans barred Bandera from moving to newly conquered Lviv

Lviv ( or ; ; ; see #Names and symbols, below for other names) is the largest city in western Ukraine, as well as the List of cities in Ukraine, fifth-largest city in Ukraine, with a population of It serves as the administrative centre of ...

, limiting his residency to occupied Kraków. On 5 July, Bandera was brought to Berlin, where he was placed in honorable captivity. On 12 July, the prime minister of the newly formed Ukrainian National Government, Yaroslav Stetsko

Yaroslav Semenovych Stetsko (; 19 January 1912 – 5 July 1986) was a Ukrainian politician, writer and ideologist who served as the leader of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B, from 1941 until his ...

, was arrested and taken to Berlin. Although released from custody on 14 July, both were required to stay in Berlin. Bandera was free to move around the city, but could not leave it. The Germans closed OUN-B offices in Berlin and Vienna, and on 15 September 1941 Bandera and leading OUN members were arrested by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

.

By the end of 1941 relations between Nazi Germany and the OUN-B had soured to the point where a Nazi document dated 25 November 1941 stated that "the Bandera Movement is preparing a revolt in the which has as its ultimate aim the establishment of an independent Ukraine. All functionaries of the Bandera Movement must be arrested at once and, after thorough interrogation, are to be liquidated".

In January 1942, Bandera was transferred to Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners t ...

's special prison cell building () for high-profile political prisoners such as Horia Sima

Horia Sima (3 July 1906 – 25 May 1993) was a Romanian fascist politician, best known as the second and last leader of the fascist paramilitary movement known as the Iron Guard (also known as the Legion of the Archangel Michael). Sima was a ...

, the chancellor of Austria, Kurt Schuschnigg

Kurt Alois Josef Johann von Schuschnigg (; 14 December 1897 – 18 November 1977) was an Austrian politician who was the Chancellor of Austria, Chancellor of the Federal State of Austria from the 1934 assassination of his predecessor Engelbert D ...

or Stefan Grot-Rowecki and high risk escapees. Bandera was not completely cut off from the outside world; his wife visited him regularly and was able to help him keep in touch with his followers. In April 1944, Bandera and his deputy Yaroslav Stetsko

Yaroslav Semenovych Stetsko (; 19 January 1912 – 5 July 1986) was a Ukrainian politician, writer and ideologist who served as the leader of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B, from 1941 until his ...

were approached by a Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office ( , RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and , the head of the Nazi Party's ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS). The organization's stat ...

official to discuss plans for diversions and sabotage against the Soviet Army.

Bandera's release was preceded by lengthy talks between the Germans and the UPA in Galicia and Volhynia. Local talks and agreements took place as early as the end of 1943, talks at the central level of the OUN-B began in March 1944 and ended with the conclusion of an informal agreement in August or September 1944. The talks from the OUN-B Provid side were led mainly by Ivan Hrynokh. Meanwhile, in July 1944, the formation of the Ukrainian Supreme Liberation Council (UHVR) took place, which was intended as a supra-party organization that constituted the civilian body overseeing the UPA and was intended as the supreme authority in Ukraine. In reality, only members or sympathizers of the OUN-B took part in its formation. became president of the UHVR, but real power rested in the hands of the General Secretariat, headed by Roman Shukhevych

Roman-Taras Osypovych Shukhevych (, also known by his pseudonym, Tur and Taras Chuprynka; 30 June 1907 – 5 March 1950) was a Ukrainian nationalism, Ukrainian nationalist and a military leader of the nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) ...

. At the congress, decisions were made to stop any open collaboration with the Germans, creating a government alongside them was excluded, only taking supplies from them was considered. It was planned to carry out partisan fighting in the rear of the approaching Soviet army. A decision was also taken to move away from radically nationalist rhetoric towards greater democratisation. A UHVR foreign mission led by Mykola Lebed

Mykola Kyrylovych Lebed (January 11, 1909 – July 18, 1998, also spelled Lebid;; also known as Maksym Ruban, Marko, and Yevhen Skyrba) was a Ukrainian nationalist political activist and guerrilla fighter. Lebed was described as a "Ukrainian fa ...

was sent to establish contact with Western governments.

On 28 September 1944, Bandera was released by the German authorities and moved to house arrest. Shortly after, the Germans released some 300 OUN members, including Stetsko and Melnyk. The release of OUN members was one of the few successes of Lebed's mission on behalf of the UHVR, which failed to establish contacts with the Western Allies. Bandera reacted negatively to the changes taking place within the OUN-B in Ukraine. His opposition was provoked by the 'democratisation' of the OUN-B and, above all, the relegation of the former leadership of the organisation to purely symbolic roles. On 5 October 1944, SS-Obergruppenführer Gottlob Berger met with Bandera and offered him the opportunity to join Andrey Vlasov

Andrey Andreyevich Vlasov (, – August 1, 1946) was a Soviet Russian Red Army general. During the Eastern Front (World War II), Axis-Soviet campaigns of World War II, he fought (1941–1942) against the ''Wehrmacht'' in the Battle of Moscow ...

and his Russian Liberation Army

The Russian Liberation Army (; , ), also known as the Vlasov army () was a collaborationist formation, primarily composed of Russians, that fought under German command during World War II. From January 1945, the army was led by Andrey Vlasov, ...

, which Bandera rejected. In December 1944, the Abwehr moved Bandera and Stetsko to Kraków in order to prepare the Ukrainian unit to be parachuted to the rear of the Soviet army. From there they sent Yurii Lopatynskyi as a courier to Shukhevych. Bandera informed him that he was ready to return to Ukraine, while Stetsko informed him that he still considered himself the Ukrainian prime minister.

Lopatynskyi arrived to Shukhevych in early January 1945. At a meeting of the Provid on 5 and 6 February 1945, it was decided that Bandera's return to Ukraine was pointless, and that it might be more beneficial for him to remain in the West, where, as a former Nazi prisoner, he could organize support of international opinion. Bandera was re-elected as leader of the whole OUN. Roman Shukhevych

Roman-Taras Osypovych Shukhevych (, also known by his pseudonym, Tur and Taras Chuprynka; 30 June 1907 – 5 March 1950) was a Ukrainian nationalism, Ukrainian nationalist and a military leader of the nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) ...

resigned as the leader of the OUN and became the leader of OUN in Ukraine and Bandera's deputy. The leaders of the OUN in Ukraine also came to the conclusion that the German-Soviet war would soon end in a Soviet victory, and a decision was made to continue the fight against the Soviets with smaller units, in order to maintain the will to fight among the population. It was also decided to hold talks with the Polish underground to conclude an anti-Soviet alliance. At that point the cooperation with Germans basically ceased with the loss of direct contact and the front moving further west.

In January, Bandera was in Lehnin

Kloster Lehnin, or just Lehnin, is a municipality in the German state of Brandenburg. It lies about west-south-west of Potsdam.

Overview

Kloster Lehnin was established on 1 April 2002 by the merger of 14 villages:

The centre of the municipality ...

, west of Berlin. Later he went to Weimar, where he took part in the formation of the Ukrainian National Committee

The Ukrainian National Committee ( ) was a Ukrainian political structure created under the leadership of Pavlo Shandruk, on March 17 (or March 12), 1945 in Weimar, Nazi Germany, nearly two months before the German Instrument of Surrender, with the ...

(UNK) as one of the leaders alongside Pavlo Shandruk

Pavlo Feofanovych Shandruk (; ; February 28, 1889 – February 15, 1979) was a general in the army of the Ukrainian National Republic, a colonel of the Polish Army, and a prominent general of the Ukrainian National Army, a military force t ...

, Volodymyr Kubijovyč

Volodymyr Kubijovyč (also spelled Kubiiovych or Kubiyovych; ; 23 September 1900 – 2 November 1985) was an anthropological geographer in prewar Poland, a wartime Ukrainian nationalist politician, a Nazi collaborator and a post-war émigré in ...

, Andriy Melnyk, Oleksandr Semenko and Pavlo Skoropadsky

Pavlo Petrovych Skoropadskyi (; – 26 April 1945) was a Ukrainian aristocrat, military and state leader, who served as the hetman of the Ukrainian State throughout 1918 following a coup d'état in April 29 of the same year.

Born the son of a n ...

. In March, the UNK appointed Shandrukh as commander of the newly formed Ukrainian National Army

The Ukrainian National Army (, abbreviated , UNA) was a World War II Ukrainian military group, created on March 17, 1945, in the town of Weimar, Nazi Germany, and subordinate to Ukrainian National Committee.

History

The army, formed on April 1 ...

(UNA), which was to fight the Soviets alongside the Germans; the Waffen-SS Galizien

The 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Galician) (; ), commonly referred to as the Galicia Division, was a World War II infantry division (military), division of the Waffen-SS, the military wing of the German Nazi Party, made up predom ...

division was incorporated. Bandera later denied in conversations with the CIA that he had been involved in the formation of these organisations or any collaboration with Germany after his release. In February 1945, at a conference of the OUN-B in Vienna, Bandera was made the leader of the Foreign Units of the OUN (ZCh OUN). It was there that he openly criticised for the first time the changes that had taken place in the OUN-B in Ukraine. With the Red Army approaching, Bandera left Vienna and travelled to Innsbruck via Prague.

Postwar activity

After the war, Bandera and his family moved several times aroundWest Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

, staying close to and in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, where Bandera organized the ZCh OUN center. He used false identification documents that helped him to conceal his past relationship with the Nazis. On 16 April 1946, the Yaroslav Stetsko

Yaroslav Semenovych Stetsko (; 19 January 1912 – 5 July 1986) was a Ukrainian politician, writer and ideologist who served as the leader of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B, from 1941 until his ...

-led Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations

Anti-Bolshevik Bloc of Nations (ABN) was an international anti-communist organization founded as a coordinating center for anti-communist and nationalist émigré political organizations from Soviet and other socialist countries.

The organizat ...

was founded, with which Bandera also collaborated. The ZCh OUN quickly became the largest organisation in the approximately 110,000-strong Ukrainian diaspora in Germany, with 5,000 members. Part of the organisation was the SB security service, headed by Myron Matviyenko. The OUN-M was three times smaller. The foreign representation of the UHVR (ZP UHVR), led by Mykola Lebed

Mykola Kyrylovych Lebed (January 11, 1909 – July 18, 1998, also spelled Lebid;; also known as Maksym Ruban, Marko, and Yevhen Skyrba) was a Ukrainian nationalist political activist and guerrilla fighter. Lebed was described as a "Ukrainian fa ...

, operated separately from the ZCh OUN, but many of its members belonged to both organizations.

As early as 1945, ZCh had established contacts with Western intelligence; from 1948 onwards, it was permanent cooperation with British intelligence

The Government of the United Kingdom maintains several intelligence agencies that deal with secret intelligence. These agencies are responsible for collecting, analysing and exploiting foreign and domestic intelligence, providing military intell ...

, which helped to transfer couriers to Ukraine in return for receiving intelligence data. ZP UHVR, collaborated with the US intelligence. A September 1945 report by the US Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

said that Bandera had "earned a fierce reputation for conducting a 'reign of terror' during World War II". Bandera was protected by the US-backed Gehlen Organization

The Gehlen Organization or Gehlen Org (often referred to as The Org) was an intelligence agency established in June 1946 by U.S. occupation authorities in the United States zone of post-war occupied Germany, and consisted of former members of the ...

but he also received help from underground organizations of former Nazis who helped Bandera to cross borders between Allied occupation zones

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

.

In 1946, agents of the US Army intelligence agency Counterintelligence Corps

The Counter Intelligence Corps (Army CIC) was a World War II and early Cold War intelligence agency within the United States Army consisting of highly trained special agents. Its role was taken over by the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps in 1961 and ...

(CIC) and NKVD entered into extradition negotiations based on the intra-Allied cooperation wartime agreement made at the Yalta Conference

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

. The CIC wanted Frederick Wilhelm Kaltenbach, who would turn out to be deceased, and in return the Soviet Union proposed Bandera. Bandera and many Ukrainian nationalists had ended up in the American zone after the war. The Soviet Union regarded all Ukrainians as Soviet citizens and demanded their repatriation under the intra-Alied agreement. The US thought Bandera was too valuable to give up due to his knowledge of the Soviet Union, so the US started blocking his extradition under an operation called "Anyface". From the perspective of the US, the Soviet Union and Poland were issuing extradition attempts of these Ukrainians to prevent the US from getting sources of intelligence, so this became one of the factors in the breakdown of the cooperation agreement. However, the CIC still considered Bandera untrustworthy and were concerned about the effect of his activities on Soviet-American relations, and in mid-1947 conducted an extensive and aggressive search to locate him. It failed, having described their quarry as "extremely dangerous" and "constantly en route, frequently in disguise". Some American intelligence reported that he even was guarded by former SS men.

The Bavarian state government initiated a crackdown on Bandera's organization for crimes such as counterfeiting and kidnapping. Gerhard von Mende, a West German government official, provided protection to Bandera who in turn provided him with political reports, which were relayed to the West German Foreign Office. Bandera reached an agreement with the BND, offering them his service, despite the CIA warning the West Germans against cooperating with him.

Following the war Bandera also visited Ukrainian communities in Canada, Austria, Italy, Spain, Belgium, the UK, and Holland.

Death

The MGB, and from 1954, theSoviet KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

, had attempted to kidnap or assassinate Bandera multiple times. On 15 October 1959, Bandera collapsed outside of Kreittmayrstrasse 7 in Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

and died shortly thereafter. A medical examination established that the cause of his death was poisoning by cyanide

In chemistry, cyanide () is an inorganic chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a carbon atom triple-bonded to a nitrogen atom.

Ionic cyanides contain the cyanide anion . This a ...

gas. On 20 October 1959, Bandera was buried in the Waldfriedhof () in Munich. His wife and three children moved to Toronto

Toronto ( , locally pronounced or ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, most populous city in Canada. It is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ontario. With a p ...

, Canada.

Two years after his death, on 17 November 1961, the German judicial bodies announced that Bandera's murderer had been a KGB agent named Bohdan Stashynsky

Bohdan Mykolayovych Stashynsky or Bogdan Nikolayevich Stashinsky (; Russian: Богдáн Николáевич Сташи́нский; born 4 November 1931) is a former Soviet spy who assassinated the Ukrainian nationalist leaders Lev Rebet ...

who used a cyanide dust spraying gun to murder Bandera acting on the orders of Soviet KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

head Alexander Shelepin

Alexander Nikolayevich Shelepin (; 18 August 1918 – 24 October 1994) was a Soviet politician and intelligence officer. A long-time member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, he served as First Deputy Prime M ...

and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

. After a detailed investigation against Stashynsky, who by then had defected from the KGB and confessed the killing, a trial took place from 8 to 15 October 1962. Stashynsky was convicted, and on 19 October he was sentenced to eight years in prison; he was released after four years.

Stashynsky had earlier assassinated Bandera's associate Lev Rebet

Lev Rebet (; 3 March 1912 – 12 October 1957) was a Ukrainian political writer and anti-communist during World War II. He was a key cabinet member in the Ukrainian government (backed by Stepan Bandera's faction of OUN), which proclaimed inde ...

by similar means.

Family

Bandera's brothers, Oleksandr and Vasyl, were arrested by the Germans and sent toAuschwitz

Auschwitz, or Oświęcim, was a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps operated by Nazi Germany in occupied Poland (in a portion annexed into Germany in 1939) during World War II and the Holocaust. It consisted of Auschw ...

concentration camp where they were allegedly killed by Polish inmates in 1942.

His father Andriy was arrested by the Soviets in late May 1941 for harboring an OUN member and transferred to Kyiv

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

. On 8 July he was sentenced to death and executed on the 10th. His sisters Oksana and Marta–Maria were arrested by the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

in 1941 and sent to a gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

in Siberia. Both were released in 1960 without the right to return to Ukraine. Marta–Maria died in Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

in 1982, and Oksana returned to Ukraine in 1989 where she died in 2004. Another sister, Volodymyra, was sentenced to a term in Soviet labor camps from 1946 to 1956. She returned to Ukraine in 1956.

Views

According to historianGrzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe

Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe (born 1979 in Zabrze, Poland as Grzegorz Rossoliński) is a German–Polish historian based in Berlin, associated with the Friedrich Meinecke Institute of the Free University of Berlin. He specializes in the history o ...

, "Bandera's worldview was shaped by numerous far-right values and concepts including ultranationalism

Ultranationalism, or extreme nationalism, is an extremist form of nationalism in which a country asserts or maintains hegemony, supremacy, or other forms of control over other nations (usually through violent coercion) to pursue its specific i ...

, fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

, and antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

; by fascination with violence; by the belief that only war could establish a Ukrainian state; and by hostility to democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

, communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

. Like other young Ukrainian nationalists, he combined extremism with religion and used religion to sacralize politics and violence." Historian Timothy Snyder

Timothy David Snyder (born August 18, 1969) is an American historian specializing in the history of Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union, and the Holocaust. He is on leave from his position as the Richard C. Levin, Richar ...

described Bandera as a fascist who "aimed to make of Ukraine a one-party fascist dictatorship without national minorities". Historian John-Paul Himka

John-Paul Himka (born May 18, 1949) is an American-Canadian historian and retired professor of history of the University of Alberta in Edmonton. Himka received his BA in Byzantine-Slavonic Studies and Ph.D. in History from the University of Michi ...

writes that Bandera remained true to the fascist ideology to the end. Ukrainian historian Andrii Portnov

Andrii Volodymyrovych Portnov (; born 17 May 1979) is a Ukrainian historian, essayist, and editor. He is the chair professor of entangled history of Ukraine at the European University Viadrina in Frankfurt (Oder). and a director of the PRISMA UK ...

writes that Bandera remained a proponent of authoritarian and violent politics until his death.

Historian Per Anders Rudling

Per Anders Rudling (born 11 April 1974 in Karlstad)The Algemeiner Per Anders Rudling.''The Algemeiner'' Jewish & Israel News. Articles by Per Anders Rudling. Retrieved 30 May 2014. is a Swedish-American historian In response to the Canadian-Ukrain ...

said that Bandera and his followers "advocated the selective breeding to create a 'pure' Ukrainian race", and that "the OUN shared the fascist attributes of anti-liberalism

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. Liberals espouse various and often mut ...

, anti-conservatism, and anti-communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

, an armed party, totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public s ...

, antisemitism, , and adoption of fascist greetings. Its leaders eagerly emphasized to Hitler and Ribbentrop

Ulrich Friedrich-Wilhelm Joachim von Ribbentrop (; 30 April 1893 – 16 October 1946) was a German Nazi politician and diplomat who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of Nazi Germany from 1938 to 1945.

Ribbentrop first came to Adolf Hitler' ...

that they shared the Nazi and a commitment to a fascist New Europe."

Historian David R. Marples described Bandera's views as "not untypical of his generation" but as holding "an extreme political stance that rejected any form of cooperation with the rulers of Ukrainian territories: the Poles and the Soviet authorities". Marples also described Bandera as "neither an orator nor a theoretician", and wrote that he had minimal importance as a thinker. Marples considered Rossolinski-Liebe to place too much importance on Bandera's views, writing that Rossolinski-Liebe struggled to find anything of note written by Bandera, and had assumed he was influenced by OUN publicist Dmytro Dontsov

Dmytro Ivanovych Dontsov (; – 30 March 1973) was a Ukrainian nationalist writer, publisher, journalist and political thinker whose radical ideas, known as integral nationalism, were a major influence on the Organization of Ukrainian Nati ...

and OUN journals.

Historian Taras Hunczak argues that Bandera's central article of faith was Ukrainian statehood, and any other goal was secondary to this view. Through an analysis of OUN documents Hunczak demonstrates the consistent expressed goal of an independent Ukrainian state through the whole history, while the OUN's stance towards the German Nazi government was changing, shifting from initial support, towards rejection, as OUN leaders become disillusioned seeing Nazi Germany rejection of Ukrainian independence. The OUN memorandum from 23 June 1941 notes that "German troops entering Ukraine will be, of course, greeted at first as liberators, but this attitude can soon change, in case Germany comes into Ukraine without appropriate promises of tsgoal to reestablish the Ukrainian state." The OUN memorandum from 14 August declares the OUN wish "to work together with Germany not from opportunism, but from a realization of the need of such cooperation for the well-being of Ukraine". Hunczak observes OUN leaders', including Bandera, attitude change after 15 September 1942, following Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

's killing of an OUN member, prompting the OUN to use the rhetoric of "German occupier" in reference to Nazi regime.

Political scientist

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science dealing with systems of governance and Power (social and political), power, and the analysis of political activities, political philosophy, political thought, polit ...

Andreas Umland

Andreas Umland (born 1967) is a German political scientist studying contemporary Russian and Ukrainian history as well as regime transitions. He has published on the post-Soviet extreme right, municipal decentralization, European fascism, post- ...

described Bandera as a "Ukrainian ultranationalist", noting he was not a "Nazi" and commenting that Ukrainian nationalism was "not a copy of Nazism". Political scientist Luboš Veselý criticises Rossoliński-Liebe's book on Bandera as intentionally painting him and all Ukrainian nationalists negatively. Per Veselý, Rossoliński-Liebe "considers nationalism in general to be closely related to fascism" and fails to put Ukrainian nationalism, as well as antisemitism and fascist movements, in context of their rise in other European countries at the time. The book does not mention arguments of other renowned Ukrainian historians, such as Heorhii Kasianov. Veselý says that "Bandera was against closer cooperation with the Nazis and he insisted that the Ukrainian national movement should not be dependent on anyone", thus opposing Rossoliński-Liebe's conclusion that Ukrainian nationalists needed the protection of Nazi Germany and therefore collaborated with them. Veselý concludes that all of this makes Rossoliński-Liebe's assessment of Bandera as a "condemnable symbol of Ukrainian fascism, antisemitism, terrorism and an inspiration for anti-Jewish pogroms and even genocide" "an abusive oversimplification, uprooting events and people from the context of the era or using harsh, unfounded and emotional judgments."

Ukrainian historian Oleksandr Zaitsev

Alexander () is a male name of Greek origin. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are A ...

notes that Rossolinski-Liebe's approach ignores "the fundamental differences between ultra-nationalist movements of nations with and without a state". Zaitsev highlights that the OUN did not identify itself with fascism, but "officially objected to this identification". Zaitsev suggests that it would be more correct to see the OUN and Bandera as the revolutionary ultranationalist movements of stateless nations, which were aiming not on "the reorganization of the existing state according to totalitarian principles, but to create a new state, using all available means, including terror, to this end." According to Zaitsev, Rossolinski-Liebe omits some facts, which do not fit into his "a priori scheme of 'fascism', 'racism' and 'genocidal nationalism'", and denies "the presence of liberatory and democratic elements" in Bandera movement. Historian Dr Raul Cârstocea, too, finds Rossoliński-Liebe's association of Bandera with fascism problematic, for one of the reasons Rossoliński-Liebe's used definition of fascism being too wide.

Views towards Poles

Marples says that Bandera "regarded Russia as the principal enemy of Ukraine, and showed little tolerance for the other two groups inhabiting Ukrainian ethnic territories, Poles and Jews". In late 1942, when Bandera was in a German concentration camp, his organization, theOrganization of Ukrainian Nationalists

The Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN; ) was a Ukrainian nationalist organization established on February 2, 1929 in Vienna, uniting the Ukrainian Military Organization with smaller, mainly youth, radical nationalist right-wing groups. ...

, was involved in a massacre of Poles in Volhynia. In early 1944, ethnic cleansing also spread to Eastern Galicia. It is estimated that more than 35,000 and up to 60,000 Poles, mostly women and children along with unarmed men, were killed during the spring and summer campaign of 1943 in Volhynia, and up to 133,000 if other regions, such as Eastern Galicia, are included.

Though not directly responsible for the 1943-1944 massacres since he was being held in Sachsenhausen concentration camp

Sachsenhausen () or Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg was a German Nazi concentration camp in Oranienburg, Germany, used from 1936 until April 1945, shortly before the defeat of Nazi Germany in May later that year. It mainly held political prisoners t ...

and not in control of the OUN-B at the time, Rossolinki-Liebe wrote that as head of OUN propaganda from 1931 to 1934 and de facto leader of the OUN-B from 1940 to 1941, Bandera had promulgated and propagandised violence towards Poles and other "ethnic and political enemies", in pursuit of an ethnically homogenous Ukrainian state, and Bandera never condemned the massacres in the post-war years. According to Yaroslav Hrytsak

Yaroslav Hrytsak (; born 1 January 1960) is a Ukrainian historian, Doctor of Historical Sciences and professor of the Ukrainian Catholic University. He is also the director of the Institute for Historical Studies of Ivan Franko National Univer ...

, Bandera was not completely aware of events in Ukraine during his internment from the summer of 1941 and had serious differences of opinion with Mykola Lebed

Mykola Kyrylovych Lebed (January 11, 1909 – July 18, 1998, also spelled Lebid;; also known as Maksym Ruban, Marko, and Yevhen Skyrba) was a Ukrainian nationalist political activist and guerrilla fighter. Lebed was described as a "Ukrainian fa ...

, the OUN-B leader who remained in Ukraine and who was one of the chief architects of the massacres of Poles.

Views towards Jews

According to Rossolinski-Liebe Bandera developed antisemitic views in the interwar years, influenced by antisemitism present among Ukrainian nationalists at that time, and Marples described Bandera as showing "little tolerance" for Jews. Speaking about Bandera and his men, political scientist Alexander John Motyl told '' Tablet'' that antisemitism was not a core part of Ukrainian nationalism in the way it was for Nazism, and the Soviet Union and Poland were considered to be the primary enemies of the OUN. According to him, the attitude of the Ukrainian nationalists towards Jews depended on political circumstances, and they considered Jews to be a "problem" because they were "implicated, or believed to be implicated" in aiding the Soviets in taking Ukrainian territory, as well as not being Ukrainian. Norman Goda wrote that "Historian Karel Berkhoff, among others, has shown that Bandera, his deputies, and the Nazis shared a key obsession, namely the notion that the Jews in Ukraine were behind Communism and Stalinist imperialism and must be destroyed." On 10 August 1940, Bandera wrote a letter to Andriy Melnyk saying that he would accept Melnyk's leadership of the OUN, provided he expelled "traitors" in the leadership. One of these was Mykola Stsibors'kyi, who Bandera accused of an absence of "morality and ethics in family life" due to having married a Jewish woman, and especially, a "suspicious" Russian Jewish woman. Portnov argues that "Bandera did not participate personally in the underground war conducted by theUkrainian Insurgent Army

The Ukrainian Insurgent Army (, abbreviated UPA) was a Ukrainian nationalist partisan formation founded by the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) on 14 October 1942. The UPA launched guerrilla warfare against Nazi Germany, the S ...

(UPA), which included the organized ethnic cleansing of the Polish population of Volhynia in north-western Ukraine and killings of the Jews, but he also never condemned them." Similarly, Rossolinski-Liebe and Umland both observe that Bandera personally had no part in the murders of Jews. Rossolinski-Liebe said "he had found no evidence that Bandera supported or condemned 'ethnic cleansing' or killing Jews and other minorities. It was, however, important that people from OUN and UPA 'identified with him. However, Bandera was aware of at least some of his followers' anti-Jewish violence: In June 1941, Yaroslav Stetsko

Yaroslav Semenovych Stetsko (; 19 January 1912 – 5 July 1986) was a Ukrainian politician, writer and ideologist who served as the leader of Stepan Bandera's faction of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists, the OUN-B, from 1941 until his ...

sent Bandera a report in which he stated "We are creating a militia which will help to remove the Jews and protect the population.", p.154

According to Rossoliński-Liebe, "After the Second World War and the Holocaust, both Bandera and his admirers were embarrassed by the vehement antisemitic component of their interwar political views and denied it systematically."

Legacy

In his 2006 article discussing "the reinterpretations of andera'scareer", historian David R. Marples, who specialises in the history of this area of Eastern Europe, stated that "the impact of Bandera lies less in his own political life and beliefs than in the events enacted in his name, or the conflicts that arose between his supporters and their enemies." According to ''