St. Chad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Chad (died 2 March 672) was a prominent 7th-century

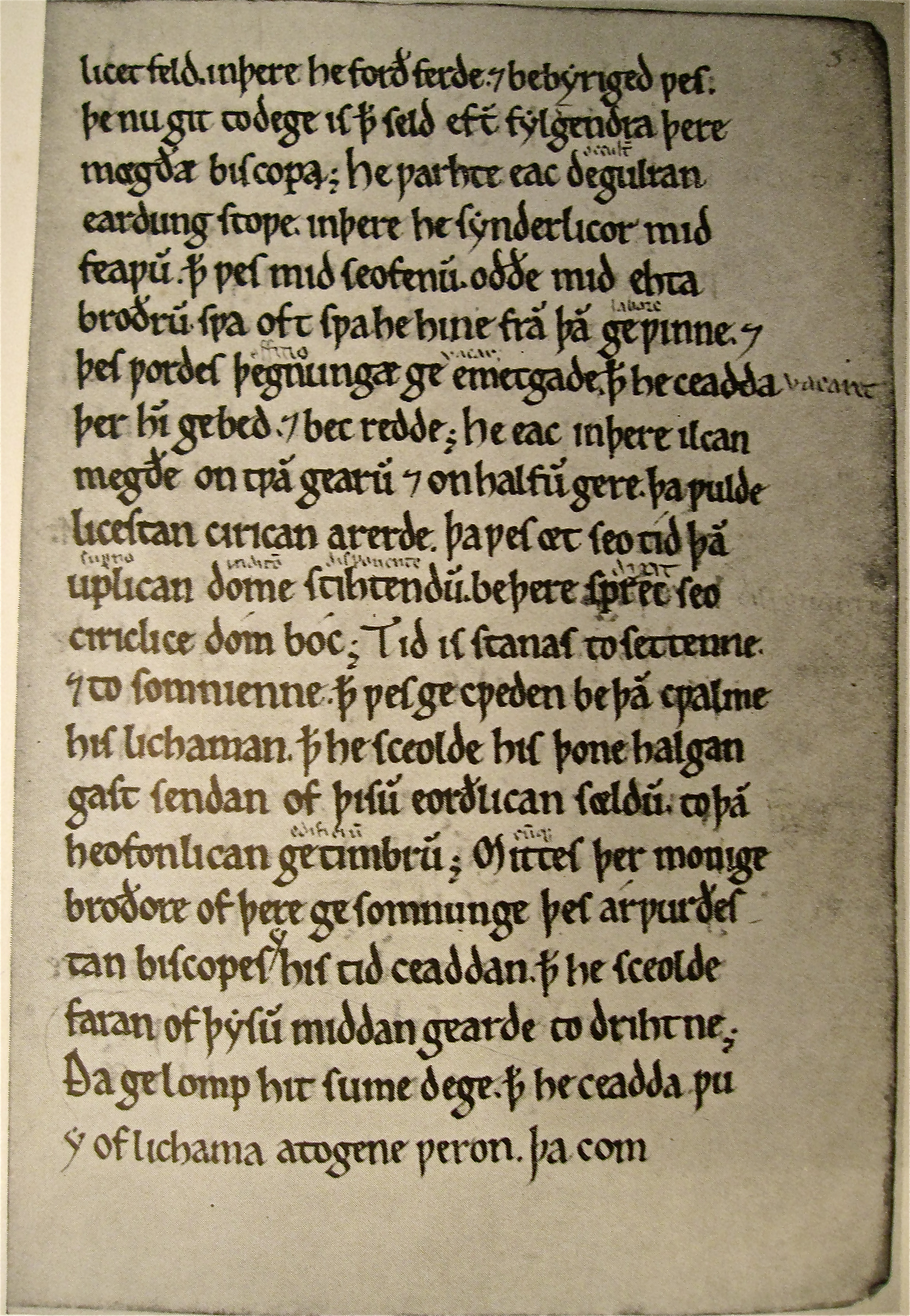

Most of what is known of Chad comes from the writings of Bede and the biography of Bishop

Most of what is known of Chad comes from the writings of Bede and the biography of Bishop

King

King

Vol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 28 September 2021

Chad is considered a saint in the

Chad is considered a saint in the

File:Chad Peada Wulfhere at Lichfield.jpeg, St Chad (left), alongside Mercian kings

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

monk. He was an abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

, Bishop of the Northumbrians and then Bishop of the Mercians and Lindsey People. After his death he was known as a saint.

He was the brother of Bishop Cedd, also a saint. He features strongly in the work of Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

and is credited, together with Bishop Wilfrid

Wilfrid ( – 709 or 710) was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and beca ...

of Ripon, with introducing Christianity to the Mercian kingdom

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

.

Sources

Wilfrid

Wilfrid ( – 709 or 710) was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and beca ...

written by Stephen of Ripon. Bede tells us that he obtained his information about Chad and his brother, Cedd, from the monk

A monk (; from , ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a man who is a member of a religious order and lives in a monastery. A monk usually lives his life in prayer and contemplation. The concept is ancient and can be seen in many reli ...

s of Lastingham

Lastingham is a village and civil parishes in England, civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is on the southern fringe of the North York Moors, north-east of Kirkbymoorside, and to the east of Hutton-le-Hole. It was home to the early m ...

, where both were abbot

Abbot is an ecclesiastical title given to the head of an independent monastery for men in various Western Christian traditions. The name is derived from ''abba'', the Aramaic form of the Hebrew ''ab'', and means "father". The female equivale ...

s. Bede also refers to information he received from Trumbert

Trumbert (or Tunberht or Tunbeorht) was a monk of Jarrow, a disciple of Chad and later Bishop of Hexham.

Life

Trumbert was educated at Lastingham by Chad, and was a teacher of Bede.Bede ''Ecclesiastical History of England'' iv 3 He was the bi ...

, "who tutored me in the Scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and ...

s and who had been educated in the monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

by that master had. In other words, Bede considered himself to stand in the spiritual lineage of Chad and had gathered information from at least one who knew him personally.

Early life and education

Family links

Chad was one of four brothers, all active in theAnglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

church. The others were Cedd

Cedd (; 620 – 26 October 664) was an Anglo-Saxon monk and bishop from the Kingdom of Northumbria. He was an evangelist of the Middle Angles and East Saxons in England and a significant participant in the Synod of Whitby, a meeting which r ...

, Cynibil

Cynibil was one of four Northumbrian brothers named by Bede as prominent in the early Anglo-Saxon Church. The others were Chad of Mercia, Cedd and Caelin.

Bede comments on how unusual it would be for four brothers to become priests and two of th ...

and Caelin. Chad seems to have been Cedd's junior, arriving on the political scene about ten years after Cedd. It is reasonable to suppose that Chad and his brothers were drawn from the Northumbrian nobility. They certainly had close connections throughout the Northumbrian ruling class. However, the name ''Chad'' is actually of British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

, rather than Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

origin. It is an element found in the personal names of many Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, of or about Wales

* Welsh language, spoken in Wales

* Welsh people, an ethnic group native to Wales

Places

* Welsh, Arkansas, U.S.

* Welsh, Louisiana, U.S.

* Welsh, Ohio, U.S.

* Welsh Basin, during t ...

princes and nobles of the period and signifies "battle".

Education

The only major fact that Bede gives about Chad's early life is that he was a student ofAidan

Aidan, Aiden and Ayden are anglicised versions of the Irish male given name ''Aodhán''. The Irish language female equivalent is ''Aodhnait''.

Etymology and spelling

The name is derived from the name ''Aodhán'', which is a pet form of '' Aod ...

at the Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

at Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th centu ...

. In fact, Bede attributes the general pattern of Chad's ministry to the example of Aidan and his own brother, Cedd

Cedd (; 620 – 26 October 664) was an Anglo-Saxon monk and bishop from the Kingdom of Northumbria. He was an evangelist of the Middle Angles and East Saxons in England and a significant participant in the Synod of Whitby, a meeting which r ...

, who was also a student of St Aidan.

Aidan was a disciple of Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

and was invited by King Oswald of Northumbria

Oswald (; c 604 – 5 August 641/642Bede gives the year of Oswald's death as 642. However there is some question of whether what Bede considered 642 is the same as what would now be considered 642. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology and H ...

to come from Iona

Iona (; , sometimes simply ''Ì'') is an island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaeli ...

to establish a monastery. Aidan arrived in Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

in 635 and died in 651. Chad must have studied at Lindisfarne some time between these years.

Travels in Ireland and dating of Chad's life

A number of ecclesiastical settlements were established in 7th-century Ireland to accommodate European monks, particularly Anglo-Saxon monks. Around 668, Bishop Colman resigned his see atLindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th centu ...

and returned to Ireland. Less than three years later he erected an abbey in County Mayo exclusively for the English monks in the village of Mayo, subsequently known as ''Maigh Eo na Saxain'' ("Mayo of the Saxons").

Chad is thought to have completed his education in Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

as a monk before he was ordained a priest, but Bede does not explicitly mention this. One of his companions in Ireland would have been Egbert of Ripon. Egbert was of the Anglian nobility, probably from Northumbria. Bede places them among English scholars who arrived in Ireland while Finan and Colmán were bishops at Lindisfarne. This suggests that they left for Ireland some time after Aidan's death in 651. They went to Rath Melsigi

Rath Melsigi was a monastery in Ireland which trained Anglo-Saxon monks. A number of monks who studied there were active in the Anglo-Saxon mission on the continent. The monastery also developed a style of script that may have influenced the write ...

, an Anglo-Saxon monastery in County Carlow

County Carlow ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county located in the Southern Region, Ireland, Southern Region of Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. Carlow is the List of Irish counties by area, second smallest and t ...

, for further study. In the controversy over the keeping of Easter, Rath Melsigi accepted the Roman computation.

In 664, the twenty-five year old Egbert barely survived a plague that had killed all his other companions. Chad had by then already left Ireland to help his brother Cedd establish the monastery of Lastingham or Laestingaeu in Yorkshire.

The Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

rule was slowly spreading across Western Europe. Chad was trained in an entirely distinct monastic tradition that tended to look back to Martin of Tours

Martin of Tours (; 316/3368 November 397) was the third bishop of Tours. He is the patron saint of many communities and organizations across Europe, including France's Third French Republic, Third Republic. A native of Pannonia (present-day Hung ...

as an exemplar. The Irish and early Anglo-Saxon monasticism experienced by Chad was peripatetic, stressed ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

practices and had a strong focus on Biblical exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

, which generated a profound eschatological consciousness. Egbert recalled later that he and Chad "followed the monastic life together very strictly – in prayers and continence, and in meditation on Holy Scripture". Some of the scholars quickly settled in Irish monasteries, while others wandered from one master to another in search of knowledge. Bede says that the Irish monks gladly taught them and fed them, and even let them use their valuable books, without charge.

Founding of Lastingham

King

King Oswiu of Northumbria

Oswiu, also known as Oswy or Oswig (; c. 612 – 15 February 670), was King of Bernicia from 642 and of Northumbria from 654 until his death. He is notable for his role at the Synod of Whitby in 664, which ultimately brought the church in Northu ...

appointed his nephew, Œthelwald, to administer the coastal area of Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/ or ; or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic , meaning 'oak' ( in modern Welsh), in which case ...

. Chad's brother Cælin was chaplain at Œthelwald's court. It was on the initiative of Cælin that Ethelwald donated land for the building of a monastery at Lastingham near Pickering in the North York Moors

The North York Moors is an upland area in north-eastern Yorkshire, England. It contains one of the largest expanses of Calluna, heather moorland in the United Kingdom. The area was designated as a national parks of England and Wales, National P ...

, close to one of the still-usable Roman road

Roman roads ( ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Republic and the Roman Em ...

s. Caelin introduced Ethelwold to Cedd. The monastery became a base for Cedd, who was serving as a missionary bishop in Essex.

Bede says that Cedd "fasted strictly in order to cleanse it from the filth of wickedness previously committed there". On the thirtieth day of his forty-day fast, he was called away on urgent business. Cynibil, another of his brothers, took over the fast for the remaining ten days. The incident indicates the brothers ties with Northumbria's ruling dynasty. Laestingaeu was conceived as a base for the family and destined to be under their control for the foreseeable future – not an unusual arrangement in this period. Cedd was stricken by the plague, and upon his death in 664, Chad succeeded him as abbot.Burton, Edwin. "St. Ceadda." The Catholic EncyclopediaVol. 3. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1908. 28 September 2021

Abbot of Lastingham

Chad's first appearance as an ecclesiastical prelate occurs in 664, shortly after theSynod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby was a Christianity, Christian administrative gathering held in Northumbria in 664, wherein King Oswiu ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Roman Catholic, Ro ...

, when many Church leaders had been wiped out by the plague – among them Cedd, who died that year at Lastingham. On the death of his elder brother, Chad succeeded to the position of abbot.

Bede tells us of a man called Owin (Owen), who appeared at the door of Lastingham. Owin was a household official of Æthelthryth

Æthelthryth (or Æðelþryð or Æþelðryþe; 23 June 679) was an East Anglian princess, a Fenland and Northumbrian queen and Abbess of Ely. She is an Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the Englis ...

, an East Anglian princess who had come to marry Ecgfrith Ecgfrith () was the name of several Anglo-Saxon kings in England, including:

* Ecgfrith of Northumbria, died 685

* Ecgfrith of Mercia

Ecgfrith was king of Mercia from 29 July to December 796. He was the son of Offa, one of the most powerful ki ...

, Oswiu's younger son. He decided to renounce the world, and as a sign of this appeared at Lastingham in ragged clothes and carrying an axe. He had come primarily to work manually. He became one of Chad's closest associates.

Chad's eschatological consciousness and its effect on others is brought to life in a reminiscence attributed to Trumbert

Trumbert (or Tunberht or Tunbeorht) was a monk of Jarrow, a disciple of Chad and later Bishop of Hexham.

Life

Trumbert was educated at Lastingham by Chad, and was a teacher of Bede.Bede ''Ecclesiastical History of England'' iv 3 He was the bi ...

, who was one of his students at Lastingham. Chad used to break off reading whenever a gale sprang up and call on God to have pity on humanity. If the storm intensified, he would shut his book altogether and prostrate himself in prayer. During prolonged storms or thunderstorms he would go into the church itself to pray and sing psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

until calm returned. His monks regarded this as an extreme reaction even to English weather and asked him to explain. Chad explained that storms are sent by God to remind humans of the day of judgement and to humble their pride. The typically Celtic Christian involvement with nature was not like the modern romantic preoccupation but a determination to read in it the mind of God, particularly in relation to the last things.

Rise of a dynasty

It is possible that he had only recently returned from Ireland when prominence was thrust upon him. However, the growing importance of his family within the Northumbrian state is clear from Bede's account of Cedd's career of the founding of their monastery at Lastingham in North Yorkshire. This concentration of ecclesiastical power and influence within the network of a noble family was probably common in Anglo-Saxon England: an obvious parallel would be the children of KingMerewalh Merewalh (sometimes given as Merwal or Merewald was a sub-king of the Magonsæte, a western cadet kingdom of Mercia thought to have been located in Herefordshire and Shropshire. Merewalh is thought to have lived in the mid to late 7th century, havin ...

in Mercia in the following generation.

Cedd

Cedd (; 620 – 26 October 664) was an Anglo-Saxon monk and bishop from the Kingdom of Northumbria. He was an evangelist of the Middle Angles and East Saxons in England and a significant participant in the Synod of Whitby, a meeting which r ...

, probably the elder brother, had become a prominent figure in the Church while Chad was in Ireland. Probably as a newly ordained priest, he was sent in 653 by Oswiu on a difficult mission to the Middle Angles

The Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon period.

Origins and territory

It is likely that Angles (tribe), Angles broke into the English Midlands ...

, at the request of their sub-king Peada, part of a developing pattern of Northumbrian intervention in Mercian affairs. After perhaps a year, he was recalled and sent on a similar mission to the East Saxons

The Kingdom of the East Saxons (; ), referred to as the Kingdom of Essex , was one of the seven traditional kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. It was founded in the 6th century and covered the territory later occupied by the counties of Essex ...

, being ordained bishop shortly afterwards. Cedd's position as both a Christian missionary and a royal emissary compelled him to travel often between Essex and Northumbria.

Bishop of the Northumbrians

Need for a bishop

Bede gives great prominence to theSynod of Whitby

The Synod of Whitby was a Christianity, Christian administrative gathering held in Northumbria in 664, wherein King Oswiu ruled that his kingdom would calculate Easter and observe the monastic tonsure according to the customs of Roman Catholic, Ro ...

in 663/4, which he shows resolving the main issues of practice in the Northumbrian Church in favour of Roman practice. Cedd is shown acting as the main go-between in the synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the Ancient Greek () ; the term is analogous with the Latin word . Originally, ...

because of his facility with all of the relevant languages. Cedd was not the only prominent churchman to die of plague shortly after the synod. This was one of several outbreaks of the plague; they badly hit the ranks of the Church leadership, with most of the bishops in the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms dead, including the archbishop of Canterbury. Bede tells us that Colmán, the bishop of the Northumbrians at the time of the Synod, had left for Scotland after the Synod went against him. He was succeeded by Tuda, who lived only a short time after his accession. The tortuous process of replacing him is covered by Bede briefly, but in some respects puzzlingly.

Mission of Wilfrid

The first choice to replace Tuda wasWilfrid

Wilfrid ( – 709 or 710) was an English bishop and saint. Born a Northumbrian noble, he entered religious life as a teenager and studied at Lindisfarne, at Canterbury, in Francia, and at Rome; he returned to Northumbria in about 660, and beca ...

, a zealous partisan of the Roman cause. Because of the plague, there were not the requisite three bishops available to ordain him, so he had gone to the Frankish

Frankish may refer to:

* Franks, a Germanic tribe and their culture

** Frankish language or its modern descendants, Franconian languages, a group of Low Germanic languages also commonly referred to as "Frankish" varieties

* Francia, a post-Roman ...

Kingdom of Neustria

Neustria was the western part of the Kingdom of the Franks during the Early Middle Ages, in contrast to the eastern Frankish kingdom, Austrasia. It initially included land between the Loire and the Silva Carbonaria, in the north of present-day ...

to seek ordination. This was on the initiative of Alfrid, sub-king of Deira, although presumably Oswiu knew and approved this action at the time. Bede tells us that Alfrid sought a bishop for himself and his own people. This probably means the people of Deira. According to Bede, Tuda had been succeeded as abbot of Lindisfarne by Eata, who had been elevated to the rank of bishop.

Wilfrid met with his own teacher and patron, Agilbert, a spokesman for the Roman side at Whitby, who had been made bishop of Paris. Agilbert set in motion the process of ordaining Wilfrid canonically, summoning several bishops to Compiègne

Compiègne (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Oise Departments of France, department of northern France. It is located on the river Oise (river), Oise, and its inhabitants are called ''Compiégnois'' ().

Administration

Compiègne is t ...

for the ceremony. Bede tells us that he then lingered abroad for some time after his ordination.

Elevation

Bede implies that Oswiu decided to take further action because Wilfrid was away for longer than expected. It is unclear whether Oswiu changed his mind about Wilfrid, or whether he despaired of his return, or whether he never really intended him to become bishop but used this opportunity to get him out of the country. Chad was invited then to become bishop of the Northumbrians by King Oswiu. Chad is often listed as aBishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers t ...

, but was more likely made Bishop of Northumbria. Bede generally uses ethnic, not geographical, designations for Chad and other early Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

bishops. However at this point, he does also refer to Oswiu's desire that Chad become bishop of the church in York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

. York later became the diocesan city partly because it had already been designated as such in the earlier Roman-sponsored mission of Paulinus to Deira, so it is not clear whether Bede is simply echoing the practice of his own day, or whether Oswiu and Chad were considering a territorial basis and a see for his episcopate. It is clear that Oswiu intended Chad to be bishop over the entire Northumbrian people, over-riding the claims of both Wilfrid and Eata.

Chad faced the same problem over ordination as Wilfrid, and so set off to seek ordination amid the chaos caused by the plague. Bede tells us that he travelled first to Canterbury, where he found that Archbishop Deusdedit was dead and his replacement was still awaited. Bede does not tell us why Chad diverted to Canterbury. The journey seems pointless, since the archbishop had died three years previously, which must have been well known in Northumbria, and was the reason Wilfrid had to go abroad. The most obvious reason for Chad's tortuous travels would be that he was also on a diplomatic mission from Oswiu, seeking to build an encircling alliance around Mercia, which was rapidly recovering from its position of weakness. From Canterbury he travelled to Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

, where he was ordained by bishop Wini Wini or WINI can refer to:

*Wini, Indonesia, a village in Indonesia with a border crossing to East Timor

*Wine (bishop)

__NOTOC__

Wine (died before 672) was a medieval Bishop of London, having earlier been consecrated the first Bishop of Winch ...

of the West Saxons

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Saxons beli ...

and two British, i.e. Welsh, bishops. None of these bishops was recognised by Rome. Bede points out that "at that time there was no other bishop in all Britain canonically ordained except Wini" and the latter had been installed irregularly by the king of the West Saxons.

Bede describes Chad at this point as "a diligent performer in deed of what he had learnt in the Scriptures should be done." Bede also tells us that Chad was teaching the values of Aidan and Cedd. His life was one of constant travel. Bede says that Chad visited continually the towns, countryside, cottages, villages and houses to preach the Gospel

Gospel originally meant the Christianity, Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the second century Anno domino, AD the term (, from which the English word originated as a calque) came to be used also for the books in which the message w ...

. The model he followed was one of the bishop as prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

or missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

. Basic Christian rites of passage, baptism

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

and confirmation

In Christian denominations that practice infant baptism, confirmation is seen as the sealing of the covenant (religion), covenant created in baptism. Those being confirmed are known as confirmands. The ceremony typically involves laying on o ...

, were almost always performed by a bishop, and for decades to come they were generally carried out in mass ceremonies, probably with little systematic instruction or counselling.

Removal

In c. 666, Wilfrid returned from Neustria, "bringing many rules of Catholic observance", as Bede says. He found Chad already occupying the same position. It seems that he did not in fact challenge Chad's pre-eminence in his own area. Rather, he would have worked assiduously to build up his own support in sympathetic monasteries, like Gilling andRipon

Ripon () is a cathedral city and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. The city is located at the confluence of two tributaries of the River Ure, the Laver and Skell. Within the boundaries of the historic West Riding of Yorkshire, the ...

. He did, however, assert his episcopal rank by going into Mercia

Mercia (, was one of the principal kingdoms founded at the end of Sub-Roman Britain; the area was settled by Anglo-Saxons in an era called the Heptarchy. It was centred on the River Trent and its tributaries, in a region now known as the Midlan ...

and even Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

to ordain priests. Bede tells us that the net effect of his efforts on the Church was that the Irish monks who still lived in Northumbria either came into line with Catholic practices or left for home. Nevertheless, Bede cannot conceal that Oswiu and Chad had broken with Roman practice in many ways and that the Church in Northumbria had been divided by the ordination of rival bishops.

In 669, a new Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Theodore of Tarsus

Theodore of Tarsus (; 60219 September 690) was Archbishop of Canterbury from 668 to 690. Theodore grew up in Tarsus, but fled to Constantinople after the Persian Empire conquered Tarsus and other cities. After studying there, he relocated to ...

, sent by Pope Vitalian

Pope Vitalian (; died 27 January 672) was the bishop of Rome from 30 July 657 to his death in 672. His pontificate was marked by the dispute between the papacy and the imperial government in Constantinople over Monothelitism, which Rome condem ...

arrived in England. He immediately set off on a tour of the country, tackling abuses of which he had been forewarned. He instructed Chad to step down and Wilfrid to take over. According to Bede, Theodore was so impressed by Chad's show of humility that he confirmed his ordination as bishop, while insisting he step down from his position. Chad retired gracefully and returned to his post as abbot of Lastingham, leaving Wilfrid as bishop of the Northumbrians at York.

Bishop of the Mercians

Recall

Later that same year, KingWulfhere of Mercia

Wulfhere or Wulfar (died 675) was King of Mercia from 658 until 675 AD. He was the first Christian king of all of Mercia, though it is not known when or how he converted from Anglo-Saxon paganism. His accession marked the end of Oswiu of North ...

requested a bishop. Wulfhere and the other sons of Penda

Penda (died 15 November 655)Manuscript A of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' gives the year as 655. Bede also gives the year as 655 and specifies a date, 15 November. R. L. Poole (''Studies in Chronology and History'', 1934) put forward the theor ...

had converted to Christianity, although Penda himself had remained a pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

until his death (655). Penda had allowed bishops to operate in Mercia, although none had succeeded in establishing the Church securely without active royal support.

Archbishop Theodore refused to consecrate a new bishop. Instead he recalled Chad out of his retirement at Lastingham. According to Bede, Theodore was impressed by Chad's humility and holiness. This was displayed particularly in his refusal to use a horse; he insisted on walking everywhere. Despite his regard for Chad, Theodore ordered him to ride on long journeys and went so far as to lift him into the saddle on one occasion.

Chad was consecrated bishop of the Mercians (literally, frontier people) and of the Lindsey people (Lindisfaras

The Lindisfaras or Lindesfaras (Old English: ''Lindisfaran'') were an Anglian tribe who, in the 6th century, established the kingdom of Lindsey between the valleys of the rivers Humber and Witham, in the north of what is now Lincolnshire. They re ...

). Bede tells us that Chad was actually the third bishop agreed by Wulfhere, making him the fifth bishop of the Mercians. The Kingdom of Lindsey

The Kingdom of Lindsey or Linnuis () was a lesser Anglo-Saxon kingdom, which was absorbed into Northumbria in the 7th century. The name Lindsey derives from the Old English toponym , meaning "Isle of Lind". was the Roman name of the settlement w ...

, covering the north-eastern area of modern Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

, was under Mercian control, although it had in the past sometimes fallen under Northumbrian control. Later Anglo-Saxon episcopal lists sometimes add the Middle Angles

The Middle Angles were an important ethnic or cultural group within the larger kingdom of Mercia in England in the Anglo-Saxons, Anglo-Saxon period.

Origins and territory

It is likely that Angles (tribe), Angles broke into the English Midlands ...

to his responsibilities. They were a distinct part of the Mercian kingdom, centred on the middle Trent and lower Tame

Tame may refer to:

*Taming, the act of training wild animals

* River Tame, Greater Manchester

*River Tame, West Midlands and the Tame Valley

* Tame, Arauca, a Colombian town and municipality

* "Tame" (song), a song by the Pixies from their 1989 a ...

– the area around Tamworth, Lichfield and Repton

Repton is a village and civil parish in the South Derbyshire district of Derbyshire, England, located on the edge of the River Trent floodplain, about north of Swadlincote. The population taken at the 2001 census was 2,707, increasing to 2 ...

that formed the core of the wider Mercian polity. It was their sub-king, Peada, who had secured the services of Chad's brother Cedd in 653, and they were frequently considered separately from the Mercians proper, a people who lived further to the west and north.

Monastic foundations

Under the patronage of Wulfhere, many monasteries were founded by Wilfrid and the site at Lichfield was selected as the centre for the new Mercian diocese. Archbishop Theodore made Chad Bishop of Mercia in 669. The Lichfield minster was similar to that at Lastingham, and Bede made clear that it was partly staffed by monks from Lastingham, including Chad's faithful retainer, Owin. Lichfield was close to the oldRoman road

Roman roads ( ; singular: ; meaning "Roman way") were physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state, built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Republic and the Roman Em ...

of Watling Street

Watling Street is a historic route in England, running from Dover and London in the southeast, via St Albans to Wroxeter. The road crosses the River Thames at London and was used in Classical Antiquity, Late Antiquity, and throughout the M ...

, the main route across Mercia, and Icknield Street

Icknield Street or Ryknild Street is a Roman road in England, with a route roughly south-west to north-east. It runs from the Fosse Way at Bourton on the Water in Gloucestershire () to Templeborough in South Yorkshire (). It passes through ...

to the north.

Wulfhere also gave Chad land for a monastery at Barrow upon Humber

Barrow upon Humber is a village and civil parish in North Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2021 census was about 3,000.

The village is near the Humber, about east from Barton-upon-Humber. The small port of Barrow Haven, north, ...

in North Lincolnshire

North Lincolnshire is a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area with Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough status in Lincolnshire, England. At the 2011 United Kingdom census, 2011 Census, it had a population of 167,446. T ...

. He travelled about on foot until the Archbishop of Canterbury gave him a horse and ordered him to ride it, at least on long journeys. Chad's shrine at Lichfield, sponsored by Bishop Walter de Langton, was destroyed in 1538.

Wulfhere also donated land sufficient for fifty families at a place in Lindsey, referred to by Bede as ''Ad Barwae''. This is probably Barrow upon Humber

Barrow upon Humber is a village and civil parish in North Lincolnshire, England. The population at the 2021 census was about 3,000.

The village is near the Humber, about east from Barton-upon-Humber. The small port of Barrow Haven, north, ...

: where an Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

monastery of a later date has been excavated. This was easily reached by river from the Midlands and close to an easy crossing of the River Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary between ...

, allowing rapid communication along surviving Roman roads with Lastingham. Chad remained abbot of Lastingham throughout his life, as well as heading the communities at both Lichfield and Barrow.

Ministry among the Mercians

Chad then proceeded to carry out missionary and pastoral work within the kingdom. Bede tells us that Chad governed the bishopric of the Mercians and of the people of Lindsey 'in the manner of the ancient fathers and in great perfection of life'. However, Bede gives little concrete information about the work of Chad in Mercia, implying that in style and substance it was a continuation of what he had done in Northumbria. The area he covered was very large, stretching across England from coast to coast. It was also, in many places, difficult terrain, with woodland, heath and mountain over much of the centre and large areas of marshland to the east. Bede does tell us that Chad built for himself a small house at Lichfield, a short distance from the church, sufficient to hold his core of seven or eight brothers, who gathered to pray and study with him there when he was not out on business. Chad worked in Mercia and Lindsey for only two and a half years before he too died during a plague. Yet Bede could write in a letter that Mercia came to the faith and Essex was recovered for it by the two brothers Cedd and Chad. In other words, Bede considered that Chad's two years as bishop were decisive in Christianising Mercia.Death

Chad died on 2 March 672, and was buried near the Church of Saint Mary which later became part ofLichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of Saint Mary and Saint Chad in Lichfield, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Lichfield, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Lichfield and the principal church of the diocese ...

. Bede relates the death story as that of a man who was already regarded as a saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

. Bede has stressed throughout his narrative that Chad's holiness communicated across boundaries of culture and politics, to Theodore, for example, in his own lifetime. The death story is important to Bede, confirming Chad's holiness and vindicating his life. The account occupies more space in Bede's account than all the rest of Chad's ministry in Northumbria and Mercia together.

Bede noted that Owin was working outside the oratory at Lichfield. Inside, Chad studied alone because the other monks were at worship in the church. Suddenly Owin heard the sound of joyful singing, coming from heaven, at first to the south-east, but gradually coming closer until it filled the roof of the oratory itself. Then there was silence for half an hour, followed by the same singing going back the way it had come. Owin at first did nothing, but about an hour later Chad called him in and told him to fetch the seven brothers from the church. Chad gave his final address to the brothers, urging them to keep the monastic discipline they had learnt. Only after this did he tell them that he knew his own death was near, speaking of death as "that friendly guest who is used to visiting the brethren". He asked them to pray, then blessed and dismissed them. The brothers left, sad and downcast.

Owin returned a little later and saw Chad privately. He asked about the singing. Chad told him that he must keep it to himself for the time being: angels had come to call him to his heavenly reward, and in seven days they would return to fetch him. So it was that Chad weakened and died after seven days on 2 March, which remains his feast day. Bede wrote that: "he had always looked forward to this day, or rather his mind had always been on the Day of the Lord". Many years later, his old friend Egbert told a visitor that someone in Ireland had seen the heavenly company coming for Chad's soul and returning with it to heaven. Significantly, with the heavenly host was Cedd. Bede was not sure whether or not the vision was actually Egbert's own.

Bede's account of Chad's death confirms the main themes of his life. Primarily he was a monastic leader, deeply involved in the small communities of loyal brothers who formed his mission team. His consciousness was strongly eschatological: focussed on the last things and their significance. Finally, he was inextricably linked with Cedd and his other brothers.

Cult and relics

Chad is considered a saint in the

Chad is considered a saint in the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

, the Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

churches, the Celtic Orthodox Church

The Celtic Orthodox Church (COC; ), also called the Holy Celtic Church, is an autocephalous Christian church in the Western Rite and Oriental Orthodox traditions founded in the 20th century in France.

Since 25 December 2007, the Celtic Orthod ...

and is also noted as a saint in a new edition of the Eastern Orthodox

Eastern Orthodoxy, otherwise known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity or Byzantine Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism ...

Synaxarion

Synaxarion or Synexarion (plurals Synaxaria, Synexaria; , from συνάγειν, ''synagein'', "to bring together"; cf. etymology of '' synaxis'' and ''synagogue''; Latin: ''Synaxarium'', ''Synexarium''; ; Ge'ez: ሲናክሳሪየም(ስንክ� ...

(Book of Saints). His feast day is celebrated on 2 March.

According to Bede, Chad was venerated as a saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

immediately after his death, and his relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

s were translated to a new shrine. He remained the centre of an important cult, focused on healing, throughout the Middle Ages. The cult had twin foci: his tomb in the nave and more particularly his skull, kept in a special Head Chapel, alongside the south choir aisle

An aisle is a linear space for walking with rows of non-walking spaces on both sides. Aisles with seating on both sides can be seen in airplanes, in buildings such as churches, cathedrals, synagogues, meeting halls, parliaments, courtrooms, ...

.

The transmission of the relics after the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

was tortuous. At the dissolution of the shrine on the instructions of King Henry VIII in 1538, Prebendary Arthur Dudley of Lichfield Cathedral removed and passed them to his nieces, Bridget and Katherine Dudley, of Russells Hall near Dudley. In 1651, they reappeared when a farmer Henry Hodgetts of Sedgley

Sedgley is a town in the north of the Dudley district, in the county of the West Midlands, England.

Historically part of Staffordshire, Sedgley is on the A459 road between Wolverhampton and Dudley, and was formerly the seat of an ancient ...

was on his death-bed and kept praying to St Chad. When the priest hearing his last confession, Fr Peter Turner SJ, asked him why he called upon Chad. Henry replied, "because his bones are in the head of my bed". He instructed his wife to give the relics to the priest, whence some of the relics found their way to the Seminary at St Omer, in France. In the early 19th century, they found their way into the hands of Sir Thomas Fitzherbert-Brockholes of Aston

Aston is an area of inner Birmingham, in the county of the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. Located immediately to the north-west of Birmingham city centre, Central Birmingham, Aston constitutes a wards of the United Kingdom, war ...

Hall, near Stone, Staffordshire

Stone is a market town and civil parish in Staffordshire, England; it is situated approximately 7 miles (11 km) north of the county town of Stafford, 7 miles (11 km) south of Stoke-on-Trent and 15 miles (24 km) north of Rugeley. As a notable c ...

. When his chapel was cleared after his death, his chaplain, Fr Benjamin Hulme, discovered the box containing the relics, which were examined and presented to Bishop Thomas Walsh, the Roman Catholic Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District

The Vicariate Apostolic of the Midland District (later of the Central District) was an ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Roman Catholic Church in England and Wales. It was led by a vicar apostolic) who was a titular bishop. The Apostolic Vicar ...

in 1837 and were enshrined in the new St Chad's Cathedral, Birmingham

The Metropolitan Cathedral Church and Basilica of Saint Chad is a Catholic cathedral in Birmingham, England. It is the mother church of the Archdiocese of Birmingham and is dedicated to Saint Chad of Mercia.

Designed by Augustus Welby Pugin ...

, opened in 1841, in a new ark designed by Augustus Pugin

Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin ( ; 1 March 1812 – 14 September 1852) was an English architect, designer, artist and critic with French and Swiss origins. He is principally remembered for his pioneering role in the Gothic Revival architecture ...

.

The relics, six bones, were enshrined on the altar of St Chad's Cathedral. They were examined by the Oxford Archaeological Laboratory by radiocarbon dating

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for Chronological dating, determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of carbon-14, radiocarbon, a radioactive Isotop ...

in 1985, and all but one of the bones (which was a third femur, and therefore could not have come from Chad) were dated to the 7th century, and were authenticated as 'true relics' by the Vatican authorities. In 1919, an Annual Mass and Solemn Outdoor Procession of the Relics was held at St Chad's Cathedral in Birmingham. This observance continues to the present, on the Saturday nearest to his Feast Day, 2 March.

In November 2022, one bone relic was returned to Lichfield Cathedral and is housed in a new shrine in the retrochoir and close to where they were located in medieval times. Lichfield Cathedral is a significant pilgrimage church-cathedral and the new shrine is a focus for all pilgrims ending their journey.

The Lichfield Angel

The Lichfield Angel is a late 8th-century Anglo-Saxon stone carving discovered at Lichfield Cathedral in Staffordshire, England, in 2003. It depicts the archangel Gabriel, likely as the left-hand portion of a larger plaque showing the Annunciatio ...

, a late 8th-century Anglo-Saxon stone carving, was discovered at Lichfield Cathedral in 2003. It depicts the archangel Gabriel

In the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, Islam), Gabriel ( ) is an archangel with the power to announce God's will to mankind, as the messenger of God. He is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament and the Quran. Many Chris ...

, likely as the left-hand portion of a larger plaque showing the annunciation

The Annunciation (; ; also referred to as the Annunciation to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Annunciation of Our Lady, or the Annunciation of the Lord; ) is, according to the Gospel of Luke, the announcement made by the archangel Gabriel to Ma ...

, along with a lost right-hand panel of the Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

. The carving is thought to be the end piece of a shrine containing the remains of Chad.

Chad is remembered in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

and the US Episcopal Church

The Episcopal Church (TEC), also known as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (PECUSA), is a member of the worldwide Anglican Communion, based in the United States. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is ...

on 2 March.

Portrayals of St Chad

There are no portraits or descriptions of St Chad from his own time. The only hint comes in the legend of Theodore lifting him bodily into the saddle, possibly suggesting that he was remembered as small in stature.Peada

Peada (died 656), a son of Penda, was briefly King of southern Mercia after his father's death in November 655The year could be pushed back to 654 if a revised interpretation of Bede's dates is used. and until his own death at the hands of his w ...

and Wulfhere

Wulfhere or Wulfar (died 675) was King of Mercia from 658 until 675 AD. He was the first Christian king of all of Mercia, though it is not known when or how he converted from Anglo-Saxon paganism. His accession marked the end of Oswiu of Nort ...

, as portrayed in 19th-century sculpture above the western entrance to Lichfield Cathedral.

File:London-Victoria and Albert Museum-Stained glass-01.jpg, "Saint Chad", stained glass window by Christopher Whall

Christopher Whitworth Whall (1849 – 23 December 1924) was a British stained-glass artist who worked from the 1880s and on into the 20th century. He is recognised as a leader in the Arts and Crafts movement and a key figure in the moder ...

. Currently exhibited at Victoria and Albert Museum

The Victoria and Albert Museum (abbreviated V&A) in London is the world's largest museum of applied arts, decorative arts and design, housing a permanent collection of over 2.8 million objects. It was founded in 1852 and named after Queen ...

, London.

Image:St Chad Church (5) - geograph.org.uk - 1592962.jpg, An example of a late sculpture of St Chad, from the Church of St Chad, Lichfield, 1930.

File:St Chad - Statue at Lichfield Cathedral.jpg, A sculpture of St Chad unveiled in 2021 outside Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of Saint Mary and Saint Chad in Lichfield, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Lichfield, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Lichfield and the principal church of the diocese ...

.

Notable dedications

Churches

Chad gives his name toBirmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

's Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

cathedral

A cathedral is a church (building), church that contains the of a bishop, thus serving as the central church of a diocese, Annual conferences within Methodism, conference, or episcopate. Churches with the function of "cathedral" are usually s ...

, where there are some relic

In religion, a relic is an object or article of religious significance from the past. It usually consists of the physical remains or personal effects of a saint or other person preserved for the purpose of veneration as a tangible memorial. Reli ...

s of the saint: about eight long bones. It is the only cathedral in England that has the relics of its patron saint enshrined upon its high altar. The Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

Lichfield Cathedral

Lichfield Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of Saint Mary and Saint Chad in Lichfield, is a Church of England cathedral in the city of Lichfield, England. It is the seat of the bishop of Lichfield and the principal church of the diocese ...

, at the site of his burial, is dedicated to Chad, and St Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under various titles such as virgin or queen, many of them mentioned in the Litany of Loreto. ...

, and still has a head chapel, where the skull of the saint was kept until it was lost during the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

. The site of the medieval shrine is also marked.

Chad also gives his name to a parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

in Lichfield (with Chad's Well, where traditionally Chad baptised

Baptism (from ) is a Christians, Christian sacrament of initiation almost invariably with the use of water. It may be performed by aspersion, sprinkling or affusion, pouring water on the head, or by immersion baptism, immersing in water eit ...

converts: now a listed building

In the United Kingdom, a listed building is a structure of particular architectural or historic interest deserving of special protection. Such buildings are placed on one of the four statutory lists maintained by Historic England in England, Hi ...

).

Dedications are densely concentrated in the West Midlands. The city of Wolverhampton

Wolverhampton ( ) is a city and metropolitan borough in the West Midlands (county), West Midlands of England. Located around 12 miles (20 km) north of Birmingham, it forms the northwestern part of the West Midlands conurbation, with the towns of ...

, for example, has two Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

churches and an Academy

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

dedicated to Chad, while the nearby village of Pattingham

Pattingham is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Pattingham and Patshull, in the South Staffordshire district, in the county of Staffordshire, England, near the county boundary with Shropshire. Pattingham is seven miles we ...

has both an Anglican church and primary school

A primary school (in Ireland, India, the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, South Africa, and Singapore), elementary school, or grade school (in North America and the Philippines) is a school for primary ...

. Shrewsbury had a large medieval church of St Chad which fell down in 1788: it was quickly replaced by a circular church in Classical style by George Steuart, on a different site but with the same dedication. Parish Church in Montford, built in 1735–38, site of the graves of the parents of Charles Darwin. Parish Church in Coseley

Coseley ( ) is a village in the Metropolitan Borough of Dudley, Dudley district, in the county of the West Midlands (county), West Midlands, England. It is situated north of Dudley itself, on the border with Wolverhampton and Sandwell. It f ...

built in 1882. In Rugby, Warwickshire

Rugby is a market town in eastern Warwickshire, England, close to the River Avon, Warwickshire, River Avon. At the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 census, its population was 78,117, making it the List of Warwickshire towns by population, secon ...

, an Orthodox Church

Orthodox Church may refer to:

* Eastern Orthodox Church, the second-largest Christian church in the world

* Oriental Orthodox Churches, a branch of Eastern Christianity

* Orthodox Presbyterian Church, a confessional Presbyterian denomination loc ...

is named for him. Further afield, there is a considerable number of dedications in areas associated with Chad's career, like the churches in Church Wilne

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a place/building for Christian religious activities and praying

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian comm ...

in Derbyshire

Derbyshire ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It borders Greater Manchester, West Yorkshire, and South Yorkshire to the north, Nottinghamshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south-east, Staffordshire to the south a ...

, Far Headingley

Far Headingley is an area of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England approximately north of the city centre. The parish of Far Headingley was created in 1868.

The area is part of the Weetwood ward of Leeds City Council and Leeds North West parliamenta ...

in Leeds

Leeds is a city in West Yorkshire, England. It is the largest settlement in Yorkshire and the administrative centre of the City of Leeds Metropolitan Borough, which is the second most populous district in the United Kingdom. It is built aro ...

, the Parish Church of Rochdale

Rochdale ( ) is a town in Greater Manchester, England, and the administrative centre of the Metropolitan Borough of Rochdale. In the United Kingdom 2021 Census, 2021 Census, the town had a population of 111,261, compared to 223,773 for the wid ...

, Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester is a ceremonial county in North West England. It borders Lancashire to the north, Derbyshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Cheshire to the south, and Merseyside to the west. Its largest settlement is the city of Manchester. ...

, and the Church of St Chad, Haggerston in London, as well as some in the Commonwealth, like Chelsea in Australia. There is also a St Chad's College

St Chad's College is one of the Colleges of Durham University#Types of College, recognised colleges of Durham University. Founded in 1904 as St Chad's Hall for the training of Church of England clergy, the college ceased theological training in ...

within the University of Durham

Durham University (legally the University of Durham) is a collegiate public research university in Durham, England, founded by an Act of Parliament in 1832 and incorporated by royal charter in 1837. It was the first recognised university to ...

, founded in 1904 as an Anglican hall.

In Canada, St Chad's Chapel and College was built in 1918 in Regina. Originally, it was a Catholic church and boys' school. In 1964, it became an Anglican school for girls, called St Chad's Girls' School. Today, it is a protected historic building in Regina.

The Principal Parish of the Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross

The Personal Ordinariate of Our Lady of the Southern Cross is a personal ordinariate of the Latin Church of the Catholic Church primarily within the territory of the Australian Catholic Bishops' Conference. It is organised to serve groups of ...

is named the Church of St Ninian

Ninian is a Christian saint, first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland. For this reason, he is known as the Apostle to the Southern Picts, and there are numerous dedicatio ...

and St Chad.

The chapel of Brasenose College, Oxford is named the Chapel of St Hugh and St Chad.

Toponyms

Chadkirk Chapel inRomiley

Romiley is a village in the Metropolitan Borough of Stockport, Greater Manchester, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of Cheshire, it borders Marple, Greater Manchester, Marple, Bredbury and Woodley, Greater Manchester, Wood ...

, Greater Manchester

Greater Manchester is a ceremonial county in North West England. It borders Lancashire to the north, Derbyshire and West Yorkshire to the east, Cheshire to the south, and Merseyside to the west. Its largest settlement is the city of Manchester. ...

, may have been dedicated to St Chad; as Kenneth Cameron points out, -''kirk'' ("church") toponyms incorporate the name of the dedicatee more often than that of the patron. The chapel dates back to the 14th century, but the site is much older, possibly dating back to the 7th century when it is believed St Chad visited to bless the well there.

St Chad's Well near Battle Bridge on the River Fleet

The River Fleet is the largest of Subterranean rivers of London, London's subterranean rivers, all of which today contain foul water for treatment. It has been used as a culverted sewer since the development of Joseph Bazalgette's London sewe ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

was a medicinal well dedicated to St Chad. It was destroyed by the Midland Railway company in 1860, and is remembered in the street name of St Chad's Place.

The Worcestershire town of Kidderminster

Kidderminster is a market town and civil parish in Worcestershire, England, south-west of Birmingham and north of Worcester, England, Worcester. Located north of the River Stour, Worcestershire, River Stour and east of the River Severn, in th ...

was thought by one 19th-century author to be named for a minster dedicated to Chad or Cedd, but modern scholars give the etymology of the name as "Cydela's monastery".

Schools

Denstone College

Denstone College is a co-educational, private, boarding and day school in Denstone, Uttoxeter, Staffordshire, England. It is a Woodard School, having been founded by Nathaniel Woodard, and so Christian traditions are practised as part of Coll ...

in Denstone

Denstone is a village and civil parish situated between the towns of Uttoxeter in East Staffordshire and Ashbourne in Derbyshire. It is located next to the River Churnet. The village has a church, village hall, primary school and a pub. The ne ...

, Uttoxeter

Uttoxeter ( , ) is a market town and civil parish in the East Staffordshire borough of Staffordshire, England. It is near to the Derbyshire county border.

The town is from Burton upon Trent via the A50 and the A38, from Stafford via the A51 ...

, in Staffordshire

Staffordshire (; postal abbreviation ''Staffs''.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West Midlands (region), West Midlands of England. It borders Cheshire to the north-west, Derbyshire and Leicestershire to the east, ...

was founded by Nathaniel Woodard

Nathaniel Woodard ( ; 21 March 1811 – 25 April 1891) was a priest in the Church of England. He founded 11 schools for the middle classes in England whose aim was to provide education based on "sound principle and sound knowledge, firmly groun ...

as the flagship Woodard School

Woodard Schools is a group of Anglican schools (both primary and secondary) affiliated to the Woodard Corporation (formerly the Society of St Nicolas) which has its origin in the work of Nathaniel Woodard, a Church of England priest in the Anglo-C ...

of the Midlands. The school was founded as St Chad's College, Denstone. The school chapel is named the Chapel of St Chad with depictions of him around the chapel's narthex

The narthex is an architectural element typical of Early Christian art and architecture, early Christian and Byzantine architecture, Byzantine basilicas and Church architecture, churches consisting of the entrance or Vestibule (architecture), ve ...

. The students of the school wear the cross of St Chad which is the school's logo. The motto of the school is ''Lignum Crucis Arbor Scientae'' which is Latin for ‘The Wood of the Cross is the Tree of Knowledge’. There are also depictions of him in the school's quadrangle.

Chad as a personal name

Chad remains a fairly popular given name, one of the few personal names current among 7th-century Anglo-Saxons to do so. However, it was little used for many centuries before a modest revival in the mid-20th century.Patronage

Due to the somewhat confused nature of Chad's appointment and the continued references to ' chads', small pieces of ballot papers punched out by voters using voting machines in the2000 US Presidential Election

Presidential elections were held in the United States on November 7, 2000. Republican Governor George W. Bush of Texas, the eldest son of 41st President George H. W. Bush, and former Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney narrowly defeated incumbe ...

, it has been jocularly suggested that Chad is the patron saint of botched elections. There is no official patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of elections, although the Church has designated a later English official, Thomas More

Sir Thomas More (7 February 1478 – 6 July 1535), venerated in the Catholic Church as Saint Thomas More, was an English lawyer, judge, social philosopher, author, statesman, theologian, and noted Renaissance humanist. He also served Henry VII ...

, the patron of politicians.

The ''Spa Research Fellowship'' states that Chad is the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of medicinal springs, although other listings do not mention this patronage.

St Chad's Day (2 March) is traditionally considered the most propitious day to sow broad beans

''Vicia faba'', commonly known as the broad bean, fava bean, or faba bean, is a species of vetch, a flowering plant in the pea and bean family Fabaceae. It is widely cultivated as a crop for human consumption, and also as a cover crop. Vari ...

in England.

Legacy

St Chad's College is a college of Durham University. St. Chad's Episcopal Church inAlbuquerque, New Mexico

Albuquerque ( ; ), also known as ABQ, Burque, the Duke City, and in the past 'the Q', is the List of municipalities in New Mexico, most populous city in the U.S. state of New Mexico, and the county seat of Bernalillo County, New Mexico, Bernal ...

was established in the 1970s.

Notes

References

Further reading

*Bassett, Steven, Ed. ''The Origins of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms''. Leicester University Press, 1989. . *Fletcher, Richard. ''The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371–1386''. HarperCollins, 1997. . * * Rudolf Vleeskruijer ''The Life of St.Chad, an Old English Homily edited with introduction, notes, illustrative texts and glossary by R. Vleeskruyer'', North-Holland, Amsterdam (1953) *Lepine, David (2021) 'Glorious Confessor. The cult of St Chad at Lichfield Cathedral during the Middle Ages'. ''SAHS transactions.'' 52, 29-52.External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Chad Of Mercia 7th-century births 672 deaths Anglo-Saxon bishops of Lichfield Bishops of York Mercian saints Northumbrian saints Christian miracle workers Yorkshire saints 7th-century English bishops 7th-century Christian saints Burials at Lichfield Cathedral People from Ryedale (district) Anglican saints