Spartan Constitution on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Spartan Constitution (or Spartan

ephor – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

/ref> Ephors themselves had more power than anyone in Sparta, although the fact that they only stayed in power for a single year reduced their ability to conflict with already established powers in the state. Since reelection was not possible, an ephor who abused his power, or confronted an established power center, would have to suffer retaliation. Although the five ephors were the only officials with regular legitimization by popular vote, in practice they were often the most conservative force in Spartan politics.

politeia

''Politeia'' ( πολιτεία) is an ancient Greek word used in Greek political thought, especially that of Plato and Aristotle. Derived from the word '' polis'' ("city-state"), it has a range of meanings from " the rights of citizens" to a " ...

) are the government and laws of the classical Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archa ...

city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

of Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

. All classical Greek city-states had a politeia; the politeia of Sparta however, was noted by many classical authors for its unique features, which supported a rigidly layered social system and a strong hoplite army.

The Spartans had no historical records, literature, or written laws, which were, according to tradition, prohibited. Attributed to the mythical figure of Lycurgus

Lycurgus (; ) was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its (), involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The Spartans i ...

, the legendary law-giver, the Spartan system of government is known mostly from the ''Constitution of the Lacedaemonians

The ''Lacedaemonion Politeia'' (), known in English as the ''Polity'', ''Constitution'', or ''Republic of the Lacedaemonians'', or the ''Spartan Constitution'',Hall 204.Marincola 349.Lipka 9: "Both arguments carry all the more weight since the ''S ...

'', a treatise attributed to the ancient Greek historian Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

, describing the institutions, customs, and practices of the ancient Spartans.

The act of the foundation

Great Rhetra

According toPlutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, Lycurgus

Lycurgus (; ) was the legendary lawgiver of Sparta, credited with the formation of its (), involving political, economic, and social reforms to produce a military-oriented Spartan society in accordance with the Delphic oracle. The Spartans i ...

(to whom is attributed the establishment of the severe reforms for which Sparta has become renowned, sometime in the 9th century BC) first sought counsel from the god Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

by obtaining an oracle from Delphi regarding the formation of his government. The divine proclamation, which he received in this manner, is known as a " rhetra" and is given in part by Plutarch as follows:

::When thou hast built a temple to Zeus Syllanius and Athena Syllania, divided the people into 'phylai

''Phyle'' (, ; Plural, pl. ''phylai'', ; derived from Greek , ''phyesthai'' ) is an ancient Greek term for tribe or clan. Members of the same ''phyle'' were known as ''symphyletai'' () meaning 'fellow tribesmen'. During the late 6th century BC, C ...

' and into 'obai', and established a senate of thirty members, including the 'archagetai', then from time to time 'appellazein' between Babyca and Cnacion, and there introduce and rescind measures; but the people must have the deciding voice and the power.

Plutarch provides by way of explanation: "In these clauses, the "phylai" and the "obai" refer to divisions and distributions of the people into clans and phratries, or brotherhoods; by "archagetai" the kings are designated, and "appellazein" means to assemble the people, with a reference to Apollo, the Pythian god, who was the source and author of the polity. The Babyca is now called Cheimarrus, and the Cnacion Oenus; but Aristotle says that Cnacion is a river, and Babyca a bridge."

Another version of the rhetra is given by H. Michell:

::After having built a temple to Zeus Syllanius and Athene Syllania, and having 'phyled the phyles' (φυλάς φυλάξαντα) and 'obed the obes' (ώβάς ώβάξαντα) you shall establish a council of thirty elders, the leaders included.

That is to say that after the people had been divided according to their different tribes ("phyles" and "obes"), they would welcome the new Lycurgan reforms

Laws of Lycurgus

The Spartans had nohistorical

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

records, literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, or written law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior, with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been variously described as a science and as the ar ...

s, which were, according to tradition

A tradition is a system of beliefs or behaviors (folk custom) passed down within a group of people or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common e ...

, expressly prohibited by an ordinance of Lycurgus, excluding the Great Rhetra.

Issuance of coinage was forbidden. Spartans were obliged to use iron obols (bars or spits), meant to encourage self-sufficiency and discourage avarice and the hoarding of wealth. A Spartan citizen in good standing (a Spartiate) was one who maintained his fighting skills, showed bravery in battle, ensured that his farms were productive, was married and had healthy children. Spartiate women were the only Greek women to hold property rights on their own, and were required to practice sports before marriage. Although they had no formal political rights, they were expected to speak their minds boldly and their opinions were heard.

Structure of Spartan society and government

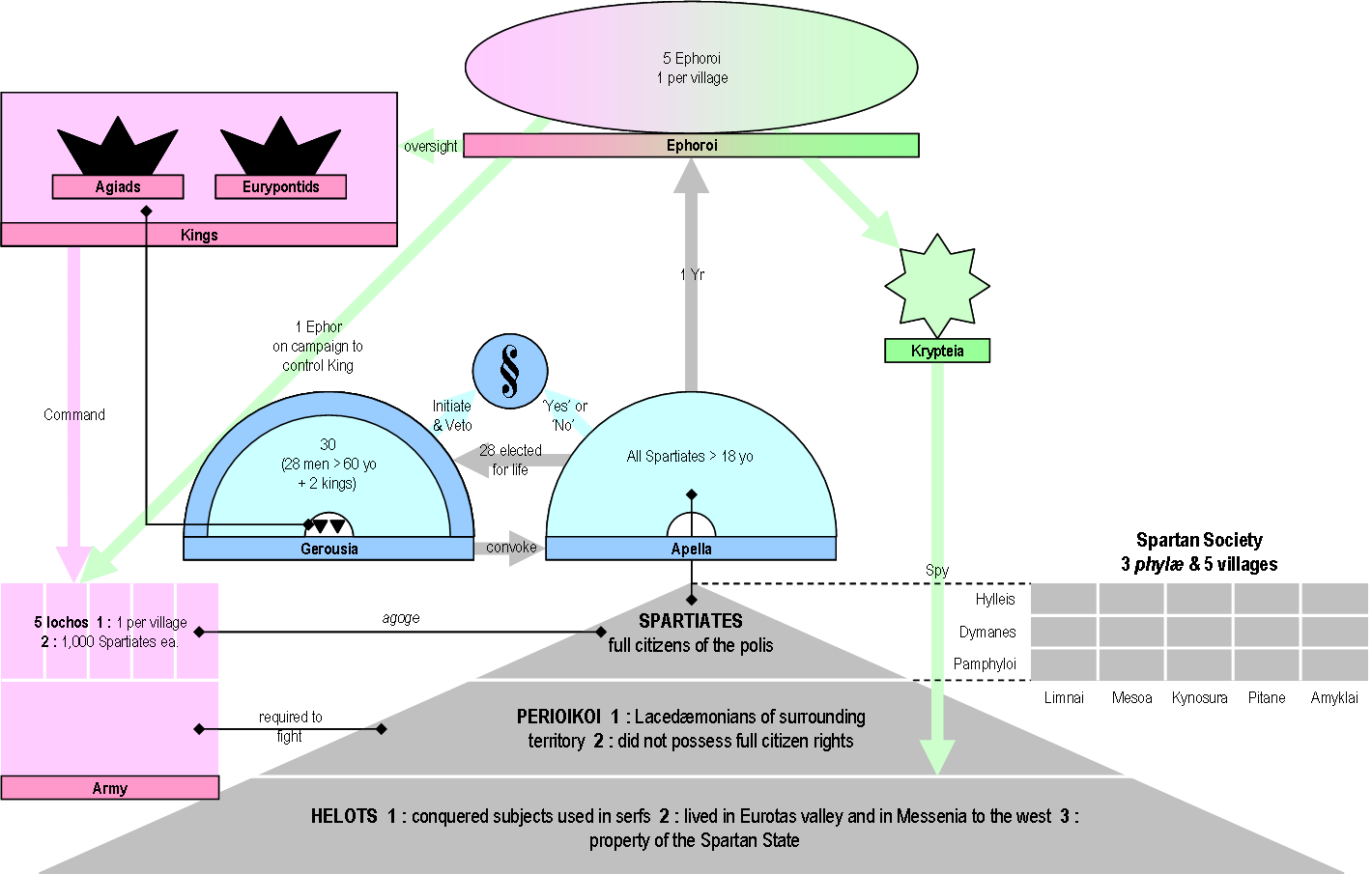

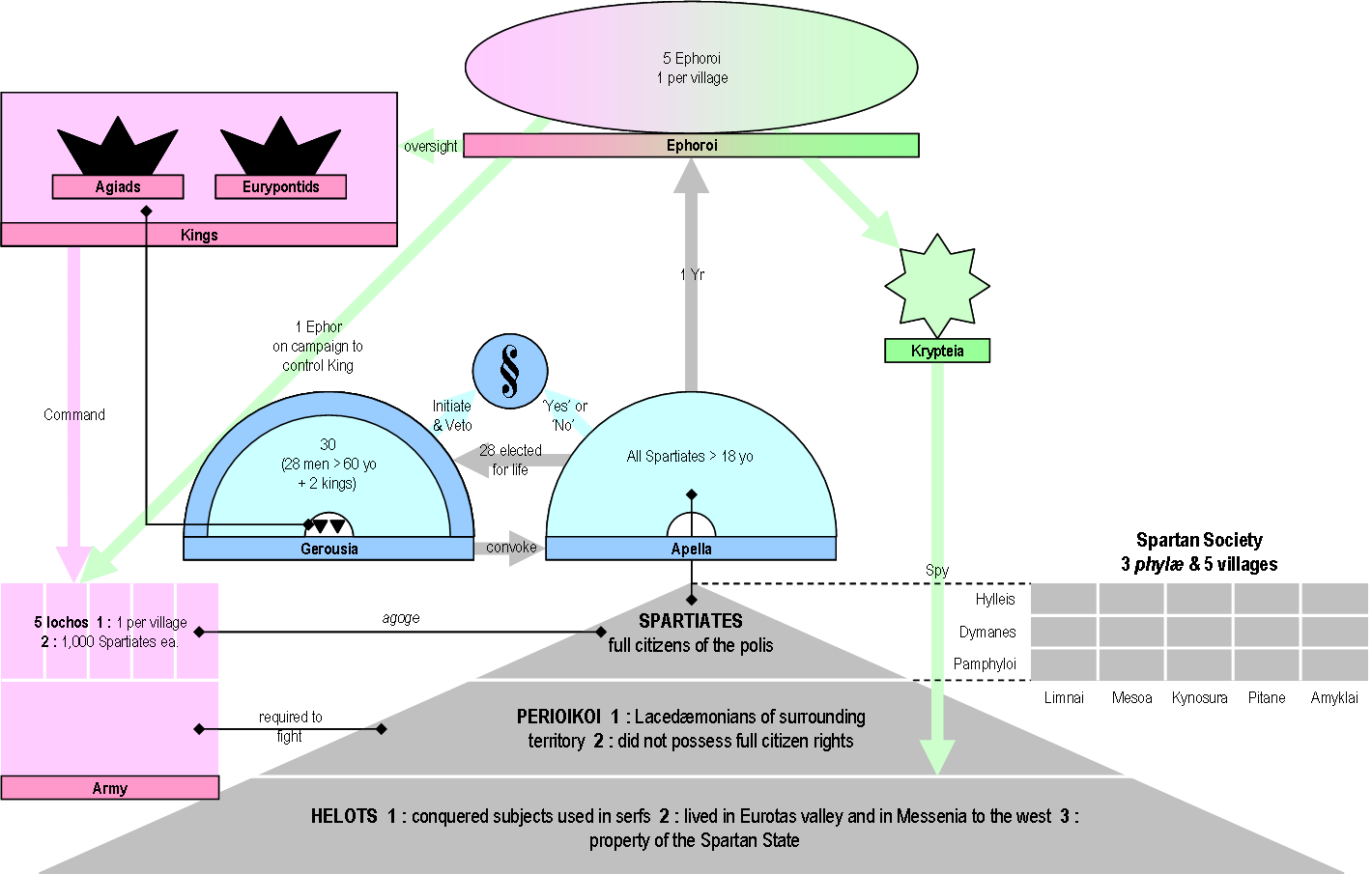

Spartan society can be represented by a three-layer pyramid ruled by the government.

Society

Legally-defined social classes were quite rigid and important in ancient Sparta. They substantially controlled social roles. The Helots did agricultural labour, spinning, weaving, and other manual labour. The Perioeci carried out most of the trade and commerce, since Spartiates were forbidden from engaging in commercial activity. Villafane Silva, C (2015) The Perioikoi: a Social, Economic and Military Study of the Other Lacedaemonians. PhD thesis, University of Liverpool. https://livrepository.liverpool.ac.uk/3001055/ Spartiate-class people were expected to be supported by their kleroi and Helots, and to do no work, except that related to military conflict. All classes, including Helots, fought in the Spartan military. The Mothax class were particularly prominent as military leaders, and the Helots made up about 80% of the armed forces.Spartiates

Spartiates

A Spartiate (, ''Spartiátēs'') or ''Homoios'' (pl. ''Homoioi'', , "alike") was an elite full-citizen men of the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. Spartiate-class men (including boys) were a small minority: estimates are that they made up be ...

were full citizens of the Spartan state (or part of the ''demos''). Most inhabitants of Sparta were not considered citizens. Only those who had successfully undertaken military training, called the agoge

The ( in Attic Greek, or , in Doric Greek) was the training program prerequisite for Spartiate (citizen) status. Spartiate-class boys entered it at age seven, and would stop being a student of the agoge at age 21. It was considered violent by ...

, and who were members in good standing of syssitia

The syssitia ( ''syssítia'', plural of ''syssítion'') were, in ancient Greece, common meals for men and youths in social or religious groups, especially in Crete and Sparta, but also in Megara in the time of Theognis of Megara (sixth century ...

(mess hall), were eligible. Usually, the only people eligible to receive the agoge were sons of Spartiate—men who could trace their ancestry to the original inhabitants of the city. There were two exceptions to this rule. '' Trophimoi'' ("foster sons") were foreign teenagers invited to study. This was meant as a supreme honour. The pro-Spartan Athenian magnate Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

sent his two sons to Sparta for their education as ''trophimoi''. Alcibiades

Alcibiades (; 450–404 BC) was an Athenian statesman and general. The last of the Alcmaeonidae, he played a major role in the second half of the Peloponnesian War as a strategic advisor, military commander, and politician, but subsequently ...

, being an Alcmaeonid and thus a member of a family with old and strong connections to Sparta, was admitted as a ''trophimos'' and famously excelled in the ''agoge'' as well as otherwise (he was rumoured to have seduced one of the two queen consorts with his exceptional looks). The other exception was that a helot's son could be enrolled as ''syntrophoi'' (comrades, literally "the ones fed, or reared, together") if a Spartiate formally adopted him and paid his way.

A free-born Spartan who had successfully completed the ''agoge'' became a "peer" (ὅμοιος, ''hómoios'', literally "similar") with full civil rights at the age of 20, and remained one as long as he could contribute his equal share of grain to the syssitia, a common military mess in which he was obliged to dine every evening for as long as he was battle-worthy (usually until the age of 60). The ''hómoioi'' were also required to sleep in the barracks until the age of 30, regardless of whether they were married or not.

Free non-citizen classes

Besides the Spartiate class, there were many free non-citizen underclasses, many of them poorly described in classical sources. The Perioeci or Períoikoi, a social class and population group of non-citizen inhabitants. The Perioeci were free, unlike thehelots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

, but were not full Spartan citizens. They had a central role in the Spartan economy, controlling commerce and business, as well as being responsible for crafts and manufacturing. The Sciritae were similar but fought as infantry not hopalites.

There were also the Hypomeion

A Spartiate (, ''Spartiátēs'') or ''Homoios'' (pl. ''Homoioi'', , "alike") was an elite full-citizen men of the ancient Greek city-state of Sparta. Spartiate-class men (including boys) were a small minority: estimates are that they made up be ...

es, literally "inferiors", men who were probably Spartiates who had lost their social rank (probably mostly because they could not afford syssitia

The syssitia ( ''syssítia'', plural of ''syssítion'') were, in ancient Greece, common meals for men and youths in social or religious groups, especially in Crete and Sparta, but also in Megara in the time of Theognis of Megara (sixth century ...

dues). The Mothax

Mothax (, ''mothax'', pl.: μόθακες, ''mothakes'') is a Doric Greek word meaning "stepbrother".

The term was used for a sociopolitical class in ancient Sparta, particularly during the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC). The mothakes were prima ...

(singular Mothon) were fostered with Spartiates and are generally thought to have been the children of slave rape by Spartiates. They were prominent in military leadership.

In the late 5th century BC and later, a new class, the Neodamodes

The neodamodes (, ''neodamōdeis'') were helots freed after passing a time of service as hoplites in the Spartan army.

The date of their first apparition is uncertain. Thucydides does not explain the origin of this special category. Jean Ducat, ...

, literally "new to the community", seems to have been composed of liberated Helots. The Epeunacti and Partheniae were among the other free non-citizen classes.

The Trophimoi were a metic

In ancient Greece, a metic (Ancient Greek: , : from , , indicating change, and , 'dwelling') was a resident of Athens and some other cities who was a citizen of another polis. They held a status broadly analogous to modern permanent residency, b ...

guest class.

Unfree classes

Helots

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristic ...

were the state-owned serfs

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed dur ...

who made up 90 percent of the population. They were citizens of conquered states, such as Messenia, who were conquered for their fertile land during the First Messenian War.

Earlier sources conflate helots and douloi, who were chattel slaves

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, but later sources distinguish them. All free classes seem to have owned douloi.

Government

The Doric state of Sparta, copying the DoricCretans

Crete ( ; , Modern: , Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the 88th largest island in the world and the fifth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, Sardinia, Cyprus, and Corsica. Crete is loc ...

, instituted a mixed governmental state: it was composed of elements of monarchical, oligarchical, and democratic systems. Isocrates

Isocrates (; ; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and writte ...

refers to the Spartans as "subject to an oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

at home, to a kingship on campaign" (iii. 24).

Dual Kingship

The state was ruled by two hereditary kings of the Agiad and the Eurypontid dynasties, both descendants ofHeracles

Heracles ( ; ), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a Divinity, divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of ZeusApollodorus1.9.16/ref> and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive descent through ...

and equal in authority so that one could not act against the power and political enactments of his colleague, though the Agiad king received greater honour by virtue of seniority of his family for being the "oldest extant" (Herod. vi. 5).

There are several legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

ary explanations for this unusual dual kingship, which differ only slightly; for example, that King Aristodemus

In Greek mythology, Aristodemus (Ancient Greek: Ἀριστόδημος) was one of the Heracleidae, son of Aristomachus and brother of Cresphontes and Temenus. He was a great-great-grandson of Heracles and helped lead the fifth and final atta ...

had twin sons, who agreed to share the kingship, and this became perpetual. Modern scholar

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a termina ...

s have advanced various theories

A theory is a systematic and rational form of abstract thinking about a phenomenon, or the conclusions derived from such thinking. It involves contemplative and logical reasoning, often supported by processes such as observation, experimentation, ...

to account for the anomaly. Some theorise that this system was created in order to prevent absolutism, and is paralleled by the analogous instance of the dual consuls of Rome. Others believe that it points to a compromise arrived at to end the struggle between two families or communities

A community is a Level of analysis, social unit (a group of people) with a shared socially-significant characteristic, such as place (geography), place, set of Norm (social), norms, culture, religion, values, Convention (norm), customs, or Ide ...

. Other theories suggest that this was an arrangement that was met when a community of villages combined to form the city of Sparta. Subsequently the two chiefs from the largest villages became kings. Another theory suggests that the two royal houses represent respectively the Spartan conquerors and their Achaean predecessors: those who hold this last view appeal to the words attributed by Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

(v. 72) to Cleomenes I

Cleomenes I (; Greek Κλεομένης; died c. 490 BC) was Agiad King of Sparta from c. 524 to c. 490 BC. One of the most important Spartan kings, Cleomenes was instrumental in organising the Greek resistance against the Persian Empire of Da ...

: "I am no Dorian, but an Achaean"; although this is usually explained by the (equally legendary) descent of Aristodemus from Heracles

Heracles ( ; ), born Alcaeus (, ''Alkaios'') or Alcides (, ''Alkeidēs''), was a Divinity, divine hero in Greek mythology, the son of ZeusApollodorus1.9.16/ref> and Alcmene, and the foster son of Amphitryon.By his adoptive descent through ...

. Either way, kingship in Sparta was hereditary and thus every king Sparta had was a descendant of the Agiad and the Eurypontid families. Accession was given to the male child who was first born after a king's accession.

The duties of the kings were primarily religious

Religion is a range of social- cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural ...

, judicial, and militaristic. They were the chief priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

s of the state, and performed certain sacrifice

Sacrifice is an act or offering made to a deity. A sacrifice can serve as propitiation, or a sacrifice can be an offering of praise and thanksgiving.

Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Gree ...

s and also maintained communication

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether Intention, unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not onl ...

with the Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

c sanctuary, which always exercised great authority in Spartan politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

. In the time of Herodotus (about 450 BC), their judicial functions had been restricted to cases dealing with heiresses, adoption

Adoption is a process whereby a person assumes the parenting of another, usually a child, from that person's biological or legal parent or parents. Legal adoptions permanently transfer all rights and responsibilities, along with filiation, fro ...

s (although that seems to have been merely the religious duty of being present instead of making any decision) and the public roads (the meaning of that last term is unclear, and has been interpreted in a number of ways, including the possibility of "voyages"; that is, the royal duties in communicating with Delphi including the organization of the official missions, though that possibility was later deemed unlikely by the very researcher who proposed it.). Civil cases were decided by the ephor

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''éph ...

s, and criminal

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a State (polity), state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definiti ...

jurisdiction had been passed to the ephors, as well as to a council of elders. By 500 BC the Spartans had become increasingly involved in the political affairs of the surrounding city-states, often putting their weight behind pro-Spartan candidates. Shortly before 500 BC, as described by Herodotus, such an action fueled a confrontation between Sparta and Athens, when the two kings, Demaratus and Cleomenes, took their troops to Athens. However, just before the heat of battle, King Demaratus changed his mind about attacking the Athenians and abandoned his co-king. For this reason, Demaratus was banished, and eventually found himself at the side of Persian King Xerxes for his invasion of Greece twenty years later (480 BC), after which the Spartans enacted a law demanding that one king remain behind in Sparta while the other commanded the troops in battle.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

describes the kingship at Sparta as "a kind of unlimited and perpetual generalship" (Pol. iii. I285a), Here also, however, the royal prerogatives were curtailed over time. Dating from the period of the Persian wars, the king lost the right to declare war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gover ...

, and was accompanied in the field by two ephors. He was supplanted also by the ephors in the control of foreign policy. Over time, the kings became mere figureheads except in their capacity as general

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

s. Real power was transferred to the ephors and to the gerousia

The Gerousia (γερουσία) was the council of elders in ancient Sparta. Sometimes called Spartan senate in the literature, it was made up of the two Spartan kings, plus 28 Spartiates over the age of sixty, known as gerontes. The Gerousia ...

.

Despite eventually losing much of their power, the kings retained much respect in the religious sense. They were highly revered after death, with elaborate mourning rituals described as duties of both Spartiates and Perioeci. In addition, there tended to be extreme reluctance to execute them for crimes; even in cases of a king being convicted of treason, he was often given the opportunity to seek asylum in other states.

Ephors

Theephors

The ephors were a board of five magistrates in ancient Sparta. They had an extensive range of judicial, religious, legislative, and military powers, and could shape Sparta's home and foreign affairs.

The word "''ephors''" (Ancient Greek ''éph ...

, chosen by popular election

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold Public administration, public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative d ...

from the whole body of citizens, represented a democratic element in the constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

.

After the ephors were introduced, they, together with the two kings, were the executive branch of the state./ref> Ephors themselves had more power than anyone in Sparta, although the fact that they only stayed in power for a single year reduced their ability to conflict with already established powers in the state. Since reelection was not possible, an ephor who abused his power, or confronted an established power center, would have to suffer retaliation. Although the five ephors were the only officials with regular legitimization by popular vote, in practice they were often the most conservative force in Spartan politics.

Gerousia

Sparta had a special policy maker, theGerousia

The Gerousia (γερουσία) was the council of elders in ancient Sparta. Sometimes called Spartan senate in the literature, it was made up of the two Spartan kings, plus 28 Spartiates over the age of sixty, known as gerontes. The Gerousia ...

, a council consisting of 28 elders over the age of 60, elected for life and usually part of the royal households, and the two kings. High state policy decisions were discussed by this council who could then propose action alternatives to the ''demos''.

Ekklesia

The collective body of Spartan citizenry would select one of the alternatives by voting. Unlike most Greek ''poleis'', the Spartan citizen assembly ( Ekklesia), could neither set the agenda of issues to be decided, nor debate them, merely vote on the alternatives presented to them. Neither could foreign embassies or emissaries address the assembly; they had to present their case to the Gerousia, which would then consult with the Ephors. Sparta considered all discourse from outside as a potential threat and all other states as past, present, or future enemies, to be treated with caution in the very least, even when bound with alliance treaties.Notes

References

Bibliography

* * {{refendConstitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

Ancient Greek constitutions

Diarchies