South Sea Company on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British

The South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British

The originators of the scheme knew that there was no money to invest in a trading venture, and no realistic expectation that there would ever be a trade to exploit, but nevertheless the potential for great wealth was widely publicised at every opportunity, so as to encourage interest in the scheme. The objective for the founders was to create a company that they could use to become wealthy and that offered scope for further government deals.

The

The

The

The

The 1719 scheme was a distinct success from the government's perspective, and they sought to repeat it. Negotiations took place between Aislabie and Craggs for the government and Blunt, Cashier Knight and his assistant and Caswell. Janssen, the Sub Governor and Deputy Governor were also consulted but negotiations remained secret from most of the company. News from France was of fortunes being made investing in Law's bank, whose shares had risen sharply. Money was moving around Europe, and other flotations threatened to soak up available capital (two insurance schemes in December 1719 each sought to raise £3 million).

Plans were made for a new scheme to take over most of the unconsolidated national debt of Britain (£30,981,712) in exchange for company shares. Annuities were valued as a lump sum necessary to produce the annual income over the original term at an assumed interest of 5%, which favoured those with shorter terms still to run. The government agreed to pay the same amount to the company for all the fixed-term repayable debt as it had been paying before, but after seven years the 5% interest rate would fall to 4% on both the new annuity debt and also that assumed previously. After the first year, the company was to give the government £3 million in four quarterly installments. New stock would be created at a face value equal to the debt, but the share price was still rising and sales of the remaining stock, i.e. the excess of the total market value of the stock over the amount of the debt, would be used to raise the government fee plus a profit for the company. The more the price rose in advance of conversion, the more the company would make. Before the scheme, payments were costing the government £1.5 million per year.Carswell, pp. 102–107

In summary, the total government debt in 1719 was £50 million:

* £18.3m was held by three large corporations:

** £3.4m by the

The 1719 scheme was a distinct success from the government's perspective, and they sought to repeat it. Negotiations took place between Aislabie and Craggs for the government and Blunt, Cashier Knight and his assistant and Caswell. Janssen, the Sub Governor and Deputy Governor were also consulted but negotiations remained secret from most of the company. News from France was of fortunes being made investing in Law's bank, whose shares had risen sharply. Money was moving around Europe, and other flotations threatened to soak up available capital (two insurance schemes in December 1719 each sought to raise £3 million).

Plans were made for a new scheme to take over most of the unconsolidated national debt of Britain (£30,981,712) in exchange for company shares. Annuities were valued as a lump sum necessary to produce the annual income over the original term at an assumed interest of 5%, which favoured those with shorter terms still to run. The government agreed to pay the same amount to the company for all the fixed-term repayable debt as it had been paying before, but after seven years the 5% interest rate would fall to 4% on both the new annuity debt and also that assumed previously. After the first year, the company was to give the government £3 million in four quarterly installments. New stock would be created at a face value equal to the debt, but the share price was still rising and sales of the remaining stock, i.e. the excess of the total market value of the stock over the amount of the debt, would be used to raise the government fee plus a profit for the company. The more the price rose in advance of conversion, the more the company would make. Before the scheme, payments were costing the government £1.5 million per year.Carswell, pp. 102–107

In summary, the total government debt in 1719 was £50 million:

* £18.3m was held by three large corporations:

** £3.4m by the

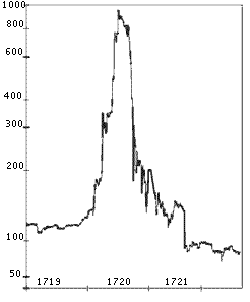

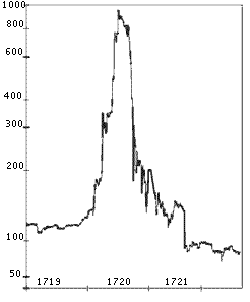

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World; this was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme's acceptance, £550 at the end of May.

What may have supported the company's high multiples (its P/E ratio) was a fund of credit (known to the market) of £70 million available for commercial expansion which had been made available through substantial support, apparently, by Parliament and the King.

Shares in the company were "sold" to politicians at the current market price; however, rather than paying for the shares, these recipients simply held the shares, with the option of selling them back to the company at any time, receiving the increase in market price. This method, as well as winning over the heads of government, the King's mistress, ''et al.'', had the advantage of binding their interests to the interests of the company: in order to secure profits, the stock needed to rise. Meanwhile, by publicising the names of their elite stockholders, the company managed to clothe itself in an aura of legitimacy, which attracted and kept other buyers.

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World; this was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme's acceptance, £550 at the end of May.

What may have supported the company's high multiples (its P/E ratio) was a fund of credit (known to the market) of £70 million available for commercial expansion which had been made available through substantial support, apparently, by Parliament and the King.

Shares in the company were "sold" to politicians at the current market price; however, rather than paying for the shares, these recipients simply held the shares, with the option of selling them back to the company at any time, receiving the increase in market price. This method, as well as winning over the heads of government, the King's mistress, ''et al.'', had the advantage of binding their interests to the interests of the company: in order to secure profits, the stock needed to rise. Meanwhile, by publicising the names of their elite stockholders, the company managed to clothe itself in an aura of legitimacy, which attracted and kept other buyers.

The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about £100 to almost £1,000 per share. Its success caused a country-wide frenzy—

The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about £100 to almost £1,000 per share. Its success caused a country-wide frenzy—

Under the

Under the

online

* * * * Dale, Richard (2004). ''The First Crash: Lessons from the South Sea Bubble'' (Princeton University Press) * Freeman, Mark, Robin Pearson, and James Taylor. (2013) "Law, politics and the governance of English and Scottish joint-stock companies, 1600–1850", ''Business History'' 55#4 (2013): 636–652

online

* Harris, Ron (1994). "The Bubble Act: Its Passage and its Effects on Business Organization", ''The Journal of Economic History'', 54 (3), 610–627 * * Hoppit, Julian. (2002) "The Myths of the South Sea Bubble", ''Transactions of the Royal Historical Society'', (2002) 12#1 pp. 141–16

in JSTOR

* Kleer, Richard A. (2015) "Riding a wave: the Company's role in the South Sea Bubble", ''The Economic History Review'' 68.1 (2015): 264–285

online

* Löwe, Kathleen (2021)

Die Südseeblase in der englischen Kunst des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts. Bilder einer Finanzkrise

', Berlin: Reimer. * * McColloch, William E. (2013) "A shackled revolution? The Bubble Act and financial regulation in eighteenth-century England", ''Review of Keynesian Economics'' 1.3 (2013): 300–313

online

* Mackay, C. ''

online

short summary * Paul, Helen. (2013) ''The South Sea Bubble: An Economic History of its Origins and Consequences'' Routledge, 176 pp. * Paul, Helen

''The "South Sea Bubble", 1720''EGO – European History Online

Mainz

Institute of European History

2015, retrieved: 17 March 2021

pdf

. * Plumb, J. H. (1956) ''Sir Robert Walpole, vol. 1, The Making of a Statesman''. ch 8 * * * Stratmann, Silke (2000) ''Myths of Speculation: The South Sea Bubble and 18th-century English Literature''. Munich: Fink * ;Fiction * . ''Novel set in the South Sea Company bubble.'' * . ''Novel set against the background of the South Sea bubble.''

Famous First Bubbles – South Sea Bubble

* *

The South Sea Bubble

audio programming with Melvyn Bragg and guests, BBC Radio 4. {{Authority control 1711 establishments in Great Britain British slave trade Age of Sail Chartered companies Companies established in 1711 Corruption in the United Kingdom Defunct companies of the United Kingdom Economic bubbles Economic history of Great Britain Financial crises History of banking Political scandals in the United Kingdom South Sea Bubble British companies established in 1711

The South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British

The South Sea Company (officially: The Governor and Company of the merchants of Great Britain, trading to the South Seas and other parts of America and for the encouragement of the Fishery) was a British joint-stock company

A joint-stock company (JSC) is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareho ...

founded in January 1711, created as a public-private partnership to consolidate and reduce the cost of the national debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occ ...

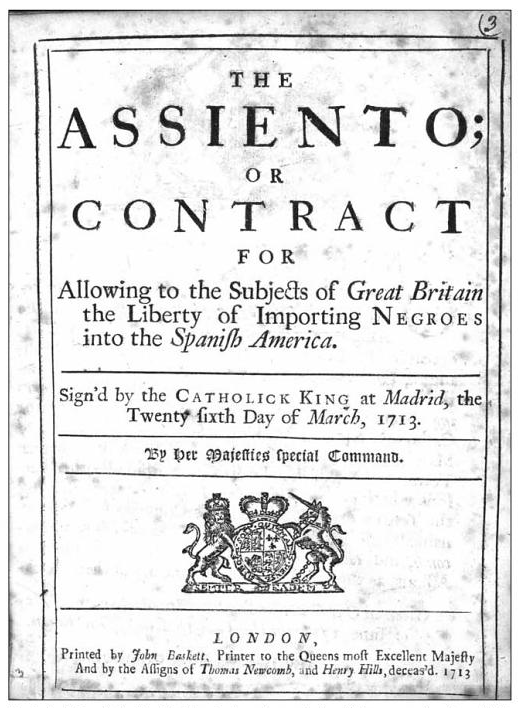

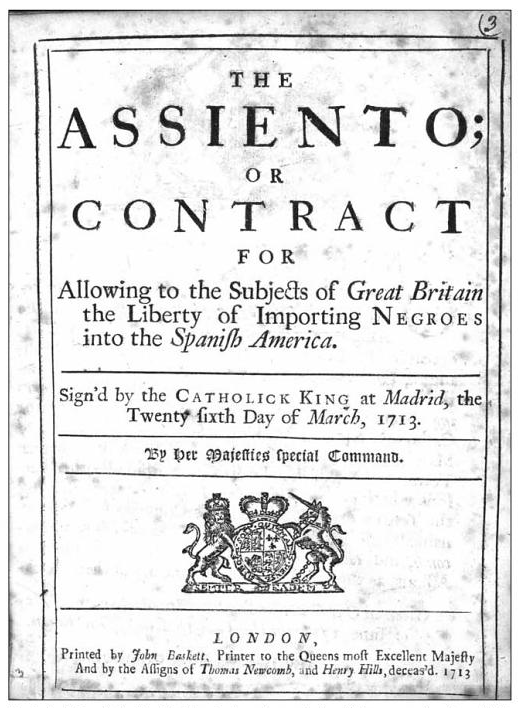

. To generate income, in 1713 the company was granted a monopoly (the ''Asiento de Negros

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide enslaved Africans to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the transatlantic slave trade directly from A ...

'') to supply African slaves to the islands in the "South Seas

Today the term South Seas, or South Sea, most commonly refers to the portion of the Pacific Ocean south of the equator. The term South Sea may also be used synonymously for Oceania, or even more narrowly for Polynesia or the Polynesian Triangle ...

" and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

. When the company was created, Britain was involved in the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

and Spain and Portugal controlled most of South America. There was thus no realistic prospect that trade would take place, and as it turned out, the Company never realised any significant profit from its monopoly. However, Company stock rose greatly in value as it expanded its operations dealing in government debt, and peaked in 1720 before suddenly collapsing to little above its original flotation price. The notorious economic bubble

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

thus created, which ruined thousands of investors, became known as the South Sea Bubble.

The Bubble Act 1720

The Bubble Act 1720 ( 6 Geo. 1. c. 18) (also Royal Exchange and London Assurance Corporation Act 1719) was an act of the Parliament of Great Britain passed on 11 June 1720 that incorporated the Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation and London As ...

( 6 Geo. 1 c. 18), which forbade the creation of joint-stock companies without royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

, was promoted by the South Sea Company itself before its collapse.

In Great Britain, many investors were ruined by the share-price collapse, and as a result, the national economy diminished substantially. The founders of the scheme engaged in insider trading

Insider trading is the trading of a public company's stock or other securities (such as bonds or stock options) based on material, nonpublic information about the company. In various countries, some kinds of trading based on insider informati ...

, by using their advance knowledge of the timings of national debt consolidations to make large profits from purchasing debt in advance. Huge bribes were given to politicians to support the Acts of Parliament necessary for the scheme. Company money was used to deal in its own shares, and selected individuals purchasing shares were given cash loans backed by those same shares to spend on purchasing more shares. The expectation of profits from trade with South America was talked up to encourage the public to purchase shares, but the bubble prices reached far beyond what the actual profits of the business (namely the slave trade) could justify.

A parliamentary inquiry was held after the bursting of the bubble to discover its causes. A number of politicians were disgraced, and people found to have profited unlawfully from the company had personal assets confiscated proportionate to their gains (most had already been rich and remained so). Finally, the Company was restructured and continued to operate for more than a century after the Bubble. The headquarters were in Threadneedle Street

Threadneedle Street is a street in the City of London, England, between Bishopsgate at its northeast end and Bank junction in the southwest. It is one of nine streets that converge at Bank. It lies in the ward of Cornhill.

History

Threadne ...

, at the centre of the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

, the financial district of the capital. At the time of these events, the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

was also a private company dealing in national debt, and the crash of its rival confirmed its position as banker to the British government.

Foundation

When in August 1710 Robert Harley was appointedChancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

, the government had already become reliant on the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

, a privately owned company chartered 16 years previously, which had obtained a monopoly as the lender to the government. The government had become dissatisfied with the service it was receiving and Harley was actively seeking new ways to improve the national finances.

A new parliament met in November 1710 resolved to attend to the national finances, which were suffering from the pressures of two simultaneous wars: the War of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

with France, which ended in 1713, and the Great Northern War

In the Great Northern War (1700–1721) a coalition led by the Tsardom of Russia successfully contested the supremacy of the Swedish Empire in Northern Europe, Northern, Central Europe, Central and Eastern Europe. The initial leaders of the ant ...

, which was not to end until 1721. Harley came prepared, with detailed accounts describing the situation of the national debt, which was customarily a piecemeal arrangement, with each government department borrowing independently as the need arose. He released the information steadily, continually adding new reports of debts incurred and scandalous expenditure, until in January 1711 the House of Commons agreed to appoint a committee to investigate the entire debt. The committee included Harley himself, the two Auditors of the Imprests (whose task was to investigate government spending), Edward Harley (the Chancellor's brother), Paul Foley (the Chancellor's brother-in-law), the Secretary of the Treasury

The United States secretary of the treasury is the head of the United States Department of the Treasury, and is the chief financial officer of the federal government of the United States. The secretary of the treasury serves as the principal a ...

, William Lowndes (who had had significant responsibility for reminting the entire debased British coinage in 1696) and John Aislabie (who represented the October Club, a group of about 200 MPs who had agreed to vote together).

Harley's first concern was to find £300,000 for the next quarter's payroll for the British army operating on the Continent under the Duke of Marlborough. This funding was provided by a private consortium of Edward Gibbon (grandfather of the historian), George Caswall

Sir George Caswall (died 1742) of Muddiford Court, Fenchurch Street, London was a British banker and politician who sat in the House of Commons between 1717 and 1741.

Religiously a Baptist, Caswall was the eldest son of James Caswall of Leomins ...

, and Hoare's Bank

C. Hoare & Co., also known as Hoares, is a British private bank, founded in 1672 by Richard Hoare (banker), Sir Richard Hoare; it is a twelfth generation family business and is owned by eight of Sir Richard's direct descendants. It is the oldest ...

. The Bank of England had been operating a lottery

A lottery (or lotto) is a form of gambling that involves the drawing of numbers at random for a prize. Some governments outlaw lotteries, while others endorse it to the extent of organizing a national or state lottery. It is common to find som ...

on behalf of the government, but in 1710 this had produced less revenue than expected and another begun in 1711 was also performing poorly; Harley granted the authority to sell tickets to John Blunt, a director of the Hollow Sword Blade Company The Hollow Sword Blades Company was a British joint-stock company founded in 1691 by a goldsmith, Sir Stephen Evance, for the manufacture of hollow-ground rapiers.

In 1700 the company was purchased by a syndicate of businessmen who used the corpo ...

, which despite its name was an unofficial bank. Sales commenced on 3 March 1711 and tickets had completely sold out by 7 March, making it the first truly successful English state lottery.

The success was shortly followed by another larger lottery, "The Two Million Adventure" or "The Classis", with tickets costing £100, with a top prize of £20,000 and every ticket winning a prize of at least £10. Although prizes were advertised by their total value, they were in fact paid out by installments in the form of a fixed annuity

In investment, an annuity is a series of payments made at equal intervals based on a contract with a lump sum of money. Insurance companies are common annuity providers and are used by clients for things like retirement or death benefits. Examples ...

over a period of years, so that the government effectively held the prize money as borrowings until the whole value had been paid out to the winners. Marketing was handled by members of the Sword Blade syndicate, Gibbon selling £200,000 of tickets and earning £4,500 commission, and Blunt selling £993,000. Charles Blunt (a relative) was made Paymaster of the lottery with expenses of £5,000.

Conception of the company

The national debt investigation concluded that a total of £9 million was owed by the government, with no specifically allocated income to pay it off. Robert Harley and John Blunt had jointly devised a scheme to consolidate this debt in much the same way that the Bank of England had consolidated previous debts, although the Bank still held the monopoly for operating as a bank. All holders of the debt (creditors) would be required to surrender it to a new company formed for the purpose, the South Sea Company, which in return would issue them shares in itself to the same nominal value. The government would make an annual payment to the Company of £568,279, equating to 6% interest plus expenses, which would then be redistributed to the shareholders as a dividend. The company was also granted a monopoly to trade with South America, a potentially lucrative enterprise, but one controlled by Spain – with which Britain was at war.Carswell, pp. 52–54 At that time, when the continent of America was being explored and colonized, Europeans applied the term "South Seas" only to South America and surrounding waters. The concession both held out the potential for future profits and encouraged a desire for an end to the war, necessary if any profits were to be made. The original suggestion for the South Sea scheme came from William Paterson, one of the founders of the Bank of England and of the financially disastrousDarien Scheme

The Darien scheme was an unsuccessful attempt, backed largely by investors of the Kingdom of Scotland, to gain wealth and influence by establishing New Caledonia, a colony in the Darién Gap on the Isthmus of Panama, in the late 1690s. The pl ...

.

Harley was rewarded for delivering the scheme by being created Earl of Oxford on 23 May 1711 and was promoted to Lord High Treasurer

The Lord High Treasurer was an English government position and has been a British government position since the Acts of Union of 1707. A holder of the post would be the third-highest-ranked Great Officer of State in England, below the Lord H ...

. With a more secure position, he began secret peace negotiations with France.

Initial speculation

The scheme to thus consolidate all government debt and to manage it better in the future held out the prospect of all existing creditors being repaid the full nominal value of their loans, which at the time before the scheme was publicised were valued at a discounted rate of £55 per £100 nominal value, as the lotteries were discredited and the government's ability to repay in full was widely doubted. Thus bonds representing the debt intended to be consolidated under the scheme were available for purchase on the open market at a price that allowed anyone with advance knowledge to buy and resell in the immediate future at a high profit, for as soon as the scheme became publicised the bonds would once again be worth at least their nominal value, as repayment was now more certain a prospect. This anticipation of gain made it possible for Harley to bring further financial supporters into the scheme, such as James Bateman and Theodore Janssen.Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

commented:The originators of the scheme knew that there was no money to invest in a trading venture, and no realistic expectation that there would ever be a trade to exploit, but nevertheless the potential for great wealth was widely publicised at every opportunity, so as to encourage interest in the scheme. The objective for the founders was to create a company that they could use to become wealthy and that offered scope for further government deals.

Flotation

The

The royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

for the company, based on that of the Bank of England, was drawn up by Blunt who was paid £3,846 for his services in setting up the company. Directors would be elected every three years and shareholders would meet twice a year. The company employed a cashier, secretary and accountant. The governor was intended as an honorary position, and was later customarily held by the monarch. The charter allowed the full court of directors to nominate a smaller committee to act on any matter on its behalf. Directors of the Bank of England and of the East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

were barred from being directors of the South Sea Company. Any ship of more than 500 tons owned by the company was to have a Church of England clergyman on board.

The surrender of government debt for company stock was to occur in five separate lots. The first two of these, totaling £2.75 million from about 200 large investors, had already been arranged before the company's charter was issued on 10 September 1711. The government itself surrendered £0.75 million of its own debt held by different departments (at that time individual office holders were at liberty to invest government funds under their control to their own advantage before it was required for government expenditure). Harley surrendered £8,000 of debt and was appointed Governor of the new company. Blunt, Caswall and Sawbridge together surrendered £65,000, Janssen £25,000 of his own plus £250,000 from a foreign consortium, Decker £49,000, Sir Ambrose Crawley £36,791. The company had a Sub-Governor, Bateman; a Deputy Governor, Ongley; and 30 ordinary directors. In total, nine of the directors were politicians, five were members of the Sword Blade consortium, and seven more were financial magnates who had been attracted to the scheme.

The company created a coat of arms with the motto ''A Gadibus usque ad Auroram'' ("from Cadiz to the dawn", from Juvenal

Decimus Junius Juvenalis (), known in English as Juvenal ( ; 55–128), was a Roman poet. He is the author of the '' Satires'', a collection of satirical poems. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, but references in his works to people f ...

, Satires, 10) and rented a large house in the City of London as its headquarters. Seven sub-committees were created to handle its everyday business, the most important being the "committee for the affairs of the company". The Sword Blade company was retained as the company's banker and on the strength of its new government connections issued notes in its own right, notwithstanding the Bank of England's monopoly. The task of the Company Secretary was to oversee trading activities; the Accountant, Grigsby, was responsible for registering and issuing stock; and the Cashier, Robert Knight, acted as Blunt's personal assistant at a salary of £200 per annum.

The slave trade

The

The Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

of 1713 granted Britain an ''Asiento de Negros

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide enslaved Africans to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the transatlantic slave trade directly from A ...

'' lasting 30 years to supply the Spanish colonies with 4,800 enslaved Africans ("slaves") per year. Britain was permitted to open offices in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

, Caracas

Caracas ( , ), officially Santiago de León de Caracas (CCS), is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas). Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern p ...

, Cartagena, Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center.Panama

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama, is a country in Latin America at the southern end of Central America, bordering South America. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean Sea to the north, and ...

, Portobello and Vera Cruz to arrange the Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

. One ship of no more than 500 tons could be sent to one of these places each year (the ''Navío de Permiso'') with general trade goods. One quarter of the profits were to be reserved for the King of Spain. There was provision for two extra sailings at the start of the contract. The Asiento was granted in the name of Queen Anne and then contracted to the company.

By July the company had arranged contracts with the Royal African Company to supply the necessary African slaves to Jamaica. Ten pounds was paid for a slave aged over 16, £8 for one under 16 but over 10. Two-thirds were to be male, and 90% adult. The company trans-shipped 1,230 slaves from Jamaica to America in the first year, plus any that might have been added (against standing instructions) by the ship's captains on their own behalf. On arrival of the first cargoes, the local authorities refused to accept the Asiento, which had still not been officially confirmed there by the Spanish authorities. The slaves were eventually sold at a loss in the West Indies.

In 1714 the government announced that a quarter of profits would be reserved for Queen Anne and a further 7.5% for a financial adviser, Manasseh Gilligan. Some company board members refused to accept the contract on these terms, and the government was obliged to reverse its decision.

Despite these setbacks, the company continued, having raised £200,000 to finance the operations. In 1714 2,680 slaves were carried, and for 1716–17, 13,000 more, but the trade continued to be unprofitable. An import duty of 33 pieces of eight was charged on each slave (although for this purpose some slaves might be counted only as a fraction of a slave, depending on quality). One of the extra trade ships was sent to Cartagena in 1714 carrying woollen goods, despite warnings that there was no market for them there, and they remained unsold for two years.

It has been estimated that the company transported a little over 34,000 slaves with mortality losses comparable to its competitors, showing that slave trading was a significant part of the company's work, and that it was carried out to the standards of the day. Its trading activities therefore offered a financial motivation for investment in the company.

Changes of management

The company was heavily dependent on the goodwill of government; when the government changed, so too did the company board. In 1714 one of the directors who had been sponsored by Harley, Arthur Moore, had attempted to send 60 tons of private goods on board the company ship. He was dismissed as a director, but the result was the beginning of Harley's fall from favour with the company. On 27 July 1714, Harley was replaced as Lord High Treasurer as a result of a disagreement that had broken out within the Tory faction in parliament. Queen Anne died on 1 August 1714; and at the election of directors in 1715 the Prince of Wales (the future King George II) was elected as Governor of the company. The new King George I and the Prince of Wales both had large holdings in the company, as did some prominent Whig politicians, including James Craggs the Elder, the Earl of Halifax and Sir Joseph Jekyll. James Craggs, as Postmaster General, was responsible for intercepting mail on behalf of the government to obtain political and financial information. All Tory politicians were removed from the board and replaced with businessmen. The Whigs Horatio Townshend, brother in law ofRobert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

, and the Duke of Argyll

Duke of Argyll () is a title created in the peerage of Scotland in 1701 and in the peerage of the United Kingdom in 1892. The earls, marquesses, and dukes of Argyll were for several centuries among the most powerful noble families in Scotlan ...

were elected directors.

The change of government led to a revival of the company's share value, which had fallen below its issue price. The previous government had failed to make the interest payments to the company for the preceding two years, owing more than £1 million. The new administration insisted that the debt be written off, but allowed the company to issue new shares to stockholders to the value of the missed payments. At around £10 million, this now represented half the share capital issued in the entire country. In 1714 the company had 2,000 to 3,000 shareholders, more than either of its rivals.

By the time of the next directors' elections in 1718 politics had changed again, with a schism within the Whigs between Walpole's faction supporting the Prince of Wales and James Stanhope's supporting the King. Argyll and Townshend were dismissed as directors, as were surviving Tories Sir Richard Hoare and George Pitt, and King George I became governor. Four MPs remained directors, as did six people holding government financial offices. The Sword Blade Company remained bankers to the South Sea, and indeed had flourished despite the company's dubious legal position. Blunt and Sawbridge remained South Sea directors, and they had been joined by Gibbon and Child. Caswall had retired as a South Sea director to concentrate on the Sword Blade business. In November 1718 Sub-Governor Bateman and Deputy Governor Shepheard both died. Leaving aside the honorary position of Governor, this left the company suddenly without its two most senior and experienced directors. They were replaced by Sir John Fellowes as Sub-Governor and Charles Joye as Deputy.

War

In 1718 war broke out with Spain once again, in theWar of the Quadruple Alliance

The War of the Quadruple Alliance, 1718 to 1720, was a conflict between Spain and a coalition of Austria, Great Britain, France, and Savoy, joined in 1719 by the Dutch Republic. Most of the fighting took place in Sicily and Spain, with minor engag ...

. The company's assets in South America were seized, at a cost claimed by the company to be £300,000. Any prospect of profit from trade, for which the company had purchased ships and had been planning its next ventures, disappeared.

Refinancing government debt

Events in France now came to influence the future of the company. A Scottish economist and financier, John Law, exiled after killing a man in a duel, had travelled around Europe before settling in France. There he founded a bank, which in December 1718 became the Banque Royale, national bank of France, while Law himself was granted sweeping powers to control the economy of France, which operated largely by royal decree. Law's remarkable success was known in financial circles throughout Europe, and now came to inspire Blunt and his associates to make greater efforts to grow their own concerns. In February 1719 Craggs explained to the House of Commons a new scheme for improving the national debt by converting the annuities issued after the 1710 lottery into South Sea stock. By Act of Parliament, the company was granted the right to issue £1,150 of new stock for every £100 per annum of annuity which was surrendered. The government would pay 5% per annum on the stock created, which would halve their annual bill. The conversion was voluntary, amounting to £2.5 million new stock if all converted. The company was to make an additional new loan to the government pro rata up to £750,000, again at 5%. In March there was an abortive attempt to restore the Old Pretender, James Edward Stuart, to the throne of Britain, with a small landing of troops in Scotland. They were defeated at theBattle of Glen Shiel

The Battle of Glen Shiel took place on 10 June 1719 in the Scottish Highlands, during the Jacobite rising of 1719. A Jacobitism, Jacobite army composed of Highland levies and Spanish Marine Infantry, Spanish marines was defeated by British gover ...

on 10 June. The South Sea company presented the offer to the public in July 1719. The Sword Blade company spread a rumour that the Pretender had been captured, and the general euphoria induced the South Sea share price to rise from £100, where it had been in the spring, to £114. Annuitants were still paid out at the same money value of shares, the company keeping the profit from the rise in value before issuing. About two-thirds of the in-force annuities were exchanged.

Trading more debt for equity

The 1719 scheme was a distinct success from the government's perspective, and they sought to repeat it. Negotiations took place between Aislabie and Craggs for the government and Blunt, Cashier Knight and his assistant and Caswell. Janssen, the Sub Governor and Deputy Governor were also consulted but negotiations remained secret from most of the company. News from France was of fortunes being made investing in Law's bank, whose shares had risen sharply. Money was moving around Europe, and other flotations threatened to soak up available capital (two insurance schemes in December 1719 each sought to raise £3 million).

Plans were made for a new scheme to take over most of the unconsolidated national debt of Britain (£30,981,712) in exchange for company shares. Annuities were valued as a lump sum necessary to produce the annual income over the original term at an assumed interest of 5%, which favoured those with shorter terms still to run. The government agreed to pay the same amount to the company for all the fixed-term repayable debt as it had been paying before, but after seven years the 5% interest rate would fall to 4% on both the new annuity debt and also that assumed previously. After the first year, the company was to give the government £3 million in four quarterly installments. New stock would be created at a face value equal to the debt, but the share price was still rising and sales of the remaining stock, i.e. the excess of the total market value of the stock over the amount of the debt, would be used to raise the government fee plus a profit for the company. The more the price rose in advance of conversion, the more the company would make. Before the scheme, payments were costing the government £1.5 million per year.Carswell, pp. 102–107

In summary, the total government debt in 1719 was £50 million:

* £18.3m was held by three large corporations:

** £3.4m by the

The 1719 scheme was a distinct success from the government's perspective, and they sought to repeat it. Negotiations took place between Aislabie and Craggs for the government and Blunt, Cashier Knight and his assistant and Caswell. Janssen, the Sub Governor and Deputy Governor were also consulted but negotiations remained secret from most of the company. News from France was of fortunes being made investing in Law's bank, whose shares had risen sharply. Money was moving around Europe, and other flotations threatened to soak up available capital (two insurance schemes in December 1719 each sought to raise £3 million).

Plans were made for a new scheme to take over most of the unconsolidated national debt of Britain (£30,981,712) in exchange for company shares. Annuities were valued as a lump sum necessary to produce the annual income over the original term at an assumed interest of 5%, which favoured those with shorter terms still to run. The government agreed to pay the same amount to the company for all the fixed-term repayable debt as it had been paying before, but after seven years the 5% interest rate would fall to 4% on both the new annuity debt and also that assumed previously. After the first year, the company was to give the government £3 million in four quarterly installments. New stock would be created at a face value equal to the debt, but the share price was still rising and sales of the remaining stock, i.e. the excess of the total market value of the stock over the amount of the debt, would be used to raise the government fee plus a profit for the company. The more the price rose in advance of conversion, the more the company would make. Before the scheme, payments were costing the government £1.5 million per year.Carswell, pp. 102–107

In summary, the total government debt in 1719 was £50 million:

* £18.3m was held by three large corporations:

** £3.4m by the Bank of England

The Bank of England is the central bank of the United Kingdom and the model on which most modern central banks have been based. Established in 1694 to act as the Kingdom of England, English Government's banker and debt manager, and still one ...

** £3.2m by the British East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company that was founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to Indian Ocean trade, trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (South A ...

** £11.7m by the South Sea Company

* Privately held redeemable debt amounted to £16.5m

* £15m consisted of irredeemable annuities, long-fixed-term annuities of 72–87 years, and short annuities of 22 years remaining to expiry.

The purpose of this conversion was similar to the old one: debt holders and annuitants might receive less return in total, but an illiquid investment was transformed into shares that could be readily traded. Shares backed by national debt were considered a safe investment and a convenient way to hold and move money, far easier and safer than metal coins. The only alternative safe asset, land, was much harder to sell and transfer of its ownership was legally much more complex.

The government received a cash payment and lower overall interest on the debt. Importantly, it also gained control over when the debt had to be repaid, which was not before seven years but then at its discretion. This avoided the risk that debt might become repayable at some future point just when the government needed to borrow more, and could be forced into paying higher interest rates. The payment to the government was to be used to buy in any debt not subscribed to the scheme, which although it helped the government, also helped the company by removing possibly competing securities from the market, including large holdings by the Bank of England.

Company stock was now trading at £123, so the issue amounted to an injection of £5 million of new money into a booming economy just as interest rates were falling. Gross Domestic Product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a monetary measure of the total market value of all the final goods and services produced and rendered in a specific time period by a country or countries. GDP is often used to measure the economic performanc ...

(GDP) for Britain at this point was estimated as £64.4 million.

Public announcement

On 21 January the plan was presented to the board of the South Sea Company, and on 22 JanuaryChancellor of the Exchequer

The chancellor of the exchequer, often abbreviated to chancellor, is a senior minister of the Crown within the Government of the United Kingdom, and the head of HM Treasury, His Majesty's Treasury. As one of the four Great Offices of State, t ...

John Aislabie presented it to Parliament. The House was stunned into silence, but on recovering proposed that the Bank of England should be invited to make a better offer. In response, the South Sea increased its cash payment to £3.5 million, while the Bank proposed to undertake the conversion with a payment of £5.5 million and a fixed conversion price of £170 per £100 face-value Bank stock. On 1 February, the company negotiators led by Blunt raised their offer to £4 million plus a proportion of £3.5 million depending on how much of the debt was converted. They also agreed that the interest rate would decrease after four years instead of seven, and agreed to sell on behalf of the government £1 million of Exchequer bills (formerly handled by the Bank). The House accepted the South Sea offer. Bank stock fell sharply.

Perhaps the first sign of difficulty came when the South Sea Company announced that its Christmas 1719 dividend would be deferred for 12 months. The company now embarked on a show of gratitude to its friends. Select individuals were sold a parcel of company stock at the current price. The transactions were recorded by Knight in the names of intermediaries, but no payments were received and no stock issued – indeed the company had none to issue until the conversion of debt began. The individual received an option to sell his stock back to the company at any future date at whatever market price might then apply. Shares went to the Craggs: the Elder

''The Elder'' is an unreleased independent film adaptation of the 1981 Kiss concept album, '' Music from "The Elder"''. The film's plot derives from that concept, devised by Kiss co-founder Gene Simmons.

The film was being produced by British a ...

and the Younger; Lord Gower; Lord Lansdowne; and four other MPs. Lord Sunderland would gain £500 for every pound that stock rose; George I's mistress, their children and Countess Platen £120 per pound rise, Aislabie £200 per pound, Lord Stanhope £600 per pound. Others invested money, including the Treasurer to the Navy, Hampden, who invested £25,000 of government money on his own behalf.

The proposal was accepted in a slightly altered form in April 1720. Crucial in this conversion was the proportion of holders of irredeemable annuities who could be tempted to convert their securities at a high price for the new shares. (Holders of redeemable debt had effectively no other choice but to subscribe.) The South Sea Company could set the conversion price but could not diverge much from the market price of its shares. The company ultimately acquired 85% of the redeemables and 80% of the irredeemables.

Inflating the share price

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World; this was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme's acceptance, £550 at the end of May.

What may have supported the company's high multiples (its P/E ratio) was a fund of credit (known to the market) of £70 million available for commercial expansion which had been made available through substantial support, apparently, by Parliament and the King.

Shares in the company were "sold" to politicians at the current market price; however, rather than paying for the shares, these recipients simply held the shares, with the option of selling them back to the company at any time, receiving the increase in market price. This method, as well as winning over the heads of government, the King's mistress, ''et al.'', had the advantage of binding their interests to the interests of the company: in order to secure profits, the stock needed to rise. Meanwhile, by publicising the names of their elite stockholders, the company managed to clothe itself in an aura of legitimacy, which attracted and kept other buyers.

The company then set to talking up its stock with "the most extravagant rumours" of the value of its potential trade in the New World; this was followed by a wave of "speculating frenzy". The share price had risen from the time the scheme was proposed: from £128 in January 1720, to £175 in February, £330 in March and, following the scheme's acceptance, £550 at the end of May.

What may have supported the company's high multiples (its P/E ratio) was a fund of credit (known to the market) of £70 million available for commercial expansion which had been made available through substantial support, apparently, by Parliament and the King.

Shares in the company were "sold" to politicians at the current market price; however, rather than paying for the shares, these recipients simply held the shares, with the option of selling them back to the company at any time, receiving the increase in market price. This method, as well as winning over the heads of government, the King's mistress, ''et al.'', had the advantage of binding their interests to the interests of the company: in order to secure profits, the stock needed to rise. Meanwhile, by publicising the names of their elite stockholders, the company managed to clothe itself in an aura of legitimacy, which attracted and kept other buyers.

Bubble Act

The South Sea Company was by no means the only company seeking to raise money from investors in 1720. A large number of other joint-stock companies, making extravagant (sometimes fraudulent) claims about foreign or other ventures or bizarre schemes, had been created. Others represented potentially sound, although novel, schemes, such as for founding insurance companies. These were nicknamed "Bubbles". Some of the companies had no legal basis, while others (such as theHollow Sword Blade Company The Hollow Sword Blades Company was a British joint-stock company founded in 1691 by a goldsmith, Sir Stephen Evance, for the manufacture of hollow-ground rapiers.

In 1700 the company was purchased by a syndicate of businessmen who used the corpo ...

, which acted as the South Sea Company's banker), used existing chartered companies for purposes entirely different from those designated at their creation. The York Buildings Company was set up to provide water to London, but was purchased by Case Billingsley who used it to purchase confiscated Jacobite estates in Scotland, which then formed the assets of an insurance company.Carswell, pp. 116–117

On 22 February 1720, John Hungerford raised the question of bubble companies in the House of Commons, and persuaded the House to set up a committee, which he chaired, to investigate. He identified a number of companies which between them sought to raise £40 million in capital. The committee investigated the companies, establishing a principle that companies should not be operating outside the objects specified in their charters. A potential embarrassment for the South Sea was avoided when the question of the Hollow Sword Blade Company arose. Difficulty was avoided by flooding the committee with MPs who were supporters of the South Sea, and voting down by 75 to 25 the proposal to investigate the Hollow Sword. (At this time, committees of the House were either 'Open' or 'secret'. A secret committee was one with a fixed set of members who could vote on its proceedings. By contrast, any MP could join in with an 'open' committee and vote on its proceedings.) Stanhope, who was a member of the committee, received £50,000 of the 'resaleable' South Sea stock from Sawbridge, a director of the Hollow Sword, at about this time. Hungerford had previously been expelled from the Commons for accepting a bribe.

Amongst the bubble companies investigated were two supported by Lords Onslow and Chetwynd respectively, for insuring shipping. These were criticised heavily, and the questionable dealings of the Attorney-General and Solicitor-General in trying to obtain charters for the companies led to both being replaced. However, the schemes had the support of Walpole and Craggs, so that the larger part of the Bubble Act (which finally resulted in June 1720 from the committee's investigations) was devoted to creating charters for the Royal Exchange Assurance Corporation or London Assurance Corporation. The companies were required to pay £300,000 for the privilege. The act required that a joint stock company could be incorporated only by act of Parliament or royal charter

A royal charter is a formal grant issued by a monarch under royal prerogative as letters patent. Historically, they have been used to promulgate public laws, the most famous example being the English Magna Carta (great charter) of 1215, but ...

. The prohibition on unauthorised joint stock ventures was not repealed until 1825.

The passing of the Act gave a boost to the South Sea Company, its shares leaping to £890 in early June. This peak encouraged people to start to sell; to counterbalance this the company's directors ordered their agents to buy, which succeeded in propping the price up at around £750.

Top reached

The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about £100 to almost £1,000 per share. Its success caused a country-wide frenzy—

The price of the stock went up over the course of a single year from about £100 to almost £1,000 per share. Its success caused a country-wide frenzy—herd behavior

Herd behavior is the behavior of individuals in a group acting collectively without centralized direction. Herd behavior occurs in animals in herds, packs, bird flocks, fish schools, and so on, as well as in humans. Voting, demonstrations, ...

—as all types of people, from peasants to lords, developed a feverish interest in investing: in South Seas primarily, but in stocks generally. One famous apocryphal story is of a company that went public in 1720 as "a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is".

The price finally reached £1,000 in early August 1720, and the level of selling was such that the price started to fall, dropping back to £100 per share before the year was out. This triggered bankruptcies

Bankruptcy is a legal process through which people or other entities who cannot repay debts to creditors may seek relief from some or all of their debts. In most jurisdictions, bankruptcy is imposed by a court order, often initiated by the deb ...

amongst those who had bought on credit, and increased sales, including short selling

In finance, being short in an asset means investing in such a way that the investor will profit if the market value of the asset falls. This is the opposite of the more common Long (finance), long Position (finance), position, where the inves ...

(i.e., selling borrowed shares in the hope of buying them back at a profit if the price fell).

Also, in August 1720, the first of the installment payments of the first and second money subscriptions on new issues of South Sea stock were due. Earlier in the year John Blunt had come up with an idea to prop up the share price: the company would lend people money to buy its shares. As a result, many shareholders could not pay for their shares except by selling them.

Furthermore, a scramble for liquidity appeared internationally as "bubbles" were also ending in Amsterdam and Paris. The collapse coincided with the fall of the Mississippi Company

John Law's Company, founded in 1717 by Scottish economist and financier John Law (economist), John Law, was a joint-stock company that occupies a unique place in French and European monetary history, as it was for a brief moment granted the enti ...

of John Law in France. As a result, the price of South Sea shares began to decline.

Recriminations

By the end of September the stock had fallen to £150. Company failures now extended tobank

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

s and goldsmith

A goldsmith is a Metalworking, metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Modern goldsmiths mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, they have also made cutlery, silverware, platter (dishware), plat ...

s, as they could not collect loans made on the stock, and thousands of individuals were ruined, including many members of the British elite

In political and sociological theory, the elite (, from , to select or to sort out) are a small group of powerful or wealthy people who hold a disproportionate amount of wealth, privilege, political power, or skill in a group. Defined by the ...

. With investors outraged, Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

was recalled in December and an investigation began. Reporting in 1721, it revealed widespread fraud

In law, fraud is intent (law), intentional deception to deprive a victim of a legal right or to gain from a victim unlawfully or unfairly. Fraud can violate Civil law (common law), civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrato ...

amongst the company directors and corruption in the Cabinet. Among those implicated were John Aislabie (the Chancellor of the Exchequer), James Craggs the Elder (the Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters.

History

The practice of having a government official ...

), James Craggs the Younger

James Craggs the Younger (9 April 168616 February 1721), was an English politician.

Life

Craggs was born at Westminster, the son of James Craggs the Elder. Part of his early life was spent abroad, where he made the acquaintance of George L ...

(the Southern Secretary), and even Lord Stanhope and Lord Sunderland (the heads of the Ministry). Craggs the Elder and Craggs the Younger both died in disgrace; the remainder were impeached

Impeachment is a process by which a legislative body or other legally constituted tribunal initiates charges against a public official for misconduct. It may be understood as a unique process involving both political and legal elements.

In Eu ...

for their corruption. The Commons found Aislabie guilty of the "most notorious, dangerous and infamous corruption", and he was imprisoned.

The newly appointed First Lord of the Treasury

The First Lord of the Treasury is the head of the Lords Commissioners of the Treasury exercising the ancient office of Lord High Treasurer in the United Kingdom. Traditional convention holds that the office of First Lord is held by the Prime Mi ...

, Robert Walpole

Robert Walpole, 1st Earl of Orford (; 26 August 1676 – 18 March 1745), known between 1725 and 1742 as Sir Robert Walpole, was a British Whigs (British political party), Whig statesman who is generally regarded as the ''de facto'' first Prim ...

, successfully restored public confidence in the financial system. However, public opinion, as shaped by the many prominent men who lost money, demanded revenge. Walpole supervised the process, which removed all 33 of the company directors and stripped them of, on average, 82% of their wealth. The money went to the victims and the stock of the South Sea Company was divided between the Bank of England and the East India Company. Walpole made sure that King George and his mistresses were protected, and by a margin of three votes he managed to save several key government officials from impeachment. In the process, Walpole won plaudits as the savior of the financial system while establishing himself as the dominant figure in British politics; historians credit him for rescuing the Whig government, and indeed the Hanoverian dynasty, from total disgrace.

Quotations prompted by the collapse

Joseph Spence wrote that Lord Radnor reported to him "When SirIsaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

was asked about the continuance of the rising of South Sea stock ... He answered 'that he could not calculate the madness of people'." He is also quoted as stating, "I can calculate the movement of the stars, but not the madness of men". Newton himself owned nearly £22,000 in South Sea stock in 1722, but it is not known how much he lost, if anything. There are, however, numerous sources stating he lost up to £20,000 (equivalent to £ in ).

A trading company

The South Sea Company was created in 1711 to reduce the size of public debts, but was granted the commercial privilege of exclusive rights of trade to the Spanish Indies, based on the treaty of commerce signed by Britain and the Archduke Charles, candidate to the Spanish throne during theWar of the Spanish Succession

The War of the Spanish Succession was a European great power conflict fought between 1701 and 1714. The immediate cause was the death of the childless Charles II of Spain in November 1700, which led to a struggle for control of the Spanish E ...

. After Philip V became the King of Spain, Britain obtained at the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

the rights to the slave trade to the Spanish Indies (or Asiento de Negros

The () was a monopoly contract between the Spanish Crown and various merchants for the right to provide enslaved Africans to colonies in the Spanish Americas. The Spanish Empire rarely engaged in the transatlantic slave trade directly from A ...

) for 30 years. Those rights were previously held by the Compagnie de Guinée et de l'Assiente du Royaume de la France.

The South Sea Company board opposed taking on the slave trade, which had shown little profitability when chartered companies had engaged in it. To increase the profitability, the Asiento contract included the right to send one yearly 500-ton ship to the fairs at Portobello and Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

loaded with duty-free merchandises, called the ''Navío de Permiso''. The Crown of England and the King of Spain were each entitled to 25% of the profits, according to the terms of the contract, that was a copy of the French Asiento contract, but Queen Anne soon renounced her share. The King of Spain did not receive any payments due to him, and this was one of the sources of contention between the Spanish Crown and the South Sea Company.

As was the case for previous holders of the Asiento, the Portuguese and the French, the profit was not in the slave trade but in the illegal contraband goods smuggled in the slave ships and in the annual ship. Those goods were sold at the Spanish colonies at a handsome price, for they were in high demand; and constituted unfair competition with taxed goods, proving a large drain on the Spanish Crown's trade income. The relationship between the South Sea Company and the Government of Spain was always bad, and worsened with time. The company complained of searches and seizures of goods, lack of profitability, and confiscation of properties during the wars between Britain and Spain of 1718–1723 and 1727–1729, during which the operations of the company were suspended. The Government of Spain complained of the illegal trade, failure of the company to present its accounts as stipulated by the contract, and non-payment of the King's share of the profits. These claims were a major cause of deteriorating relations between the two countries in 1738; and although the Prime Minister Walpole opposed war, there was strong support for it from the King, the House of Commons, and a faction in his own Cabinet. Walpole was able to negotiate a treaty with the King of Spain at the Convention of Pardo in January 1739 that stipulated that Spain would pay British merchants £95,000 in compensation for captures and seized goods, while the South Sea Company would pay the Spanish Crown £68,000 in due proceeds from the Asiento. The South Sea Company refused to pay those proceeds and the King of Spain retained payment of the compensation until payment from the South Sea Company could be secured. The break-up of relations between the South Sea Company and the Spanish Government was a prelude to the '' Guerra del Asiento'', as the first Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

fleets departed in July 1739 for the Caribbean, prior to the declaration of war, which lasted from October 1739 until 1748. This war is known as the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear was fought by Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and History of Spain (1700–1808), Spain between 1739 and 1748. The majority of the fighting took place in Viceroyalty of New Granada, New Granada and the Caribbean ...

.

Slave trade under the Asiento

Under the

Under the Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed in Tordesillas, Spain, on 7 June 1494, and ratified in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Kingdom of Portugal and the Crown of Castile, along a meridian (geography) ...

, Spain was the only European power that could not establish factories in Africa to purchase slaves. The slaves for Spanish America were provided by companies that were granted exclusive rights to their trade. This monopoly contract was called the slave Asiento. Between 1701 and 1713 the Asiento contract was granted to France. In 1711 Britain had created the South Sea Company to reduce debt and to trade with Spanish America, but that commerce was illegal without a permit from Spain, and the only existing permit was the Asiento for the slave trade, so at the Treaty of Utrecht

The Peace of Utrecht was a series of peace treaty, peace treaties signed by the belligerents in the War of the Spanish Succession, in the Dutch city of Utrecht between April 1713 and February 1715. The war involved three contenders for the vac ...

in 1713 Britain obtained the transfer of the Asiento contract from French to British hands for the next 30 years.

The board of directors was reluctant to take on the slave trade, which was not an object of the company and had shown little profitability when carried out by chartered companies, but they finally agreed on 26 March 1714. The Asiento set a sale quota of 4,800 units of slaves per year. An adult male slave counted as one unit; females and children counted as fractions of a unit. Initially the slaves were provided by the Royal African Company.

The South Sea Company established slave reception factories at Cartagena, Colombia

Cartagena ( ), known since the colonial era as Cartagena de Indias (), is a city and one of the major ports on the northern coast of Colombia in the Caribbean Coast Region, along the Caribbean Sea. Cartagena's past role as a link in the route ...

, Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, Mexico, Panama, Portobello, La Guaira

La Guaira () is the capital city of the Venezuelan Vargas (state), state of the same name (formerly named Vargas) and the country's main port, founded in 1577 as an outlet for nearby Caracas.

The city hosts its own professional baseball team i ...

, Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

, La Havana and Santiago de Cuba

Santiago de Cuba is the second-largest city in Cuba and the capital city of Santiago de Cuba Province. It lies in the southeastern area of the island, some southeast of the Cuban capital of Havana.

The municipality extends over , and contains t ...

, and slave deposits at Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

and Barbados

Barbados, officially the Republic of Barbados, is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies and the easternmost island of the Caribbean region. It lies on the boundary of the South American ...

. Despite problems with speculation, the South Sea Company was relatively successful at slave trading and meeting its quota (it was unusual for other, similarly chartered companies to fulfill their quotas). According to records compiled by David Eltis and others, during the course of 96 voyages in 25 years, the South Sea Company purchased 34,000 slaves, of whom 30,000 survived the voyage across the Atlantic. (Thus about 11% of the slaves died on the voyage: a relatively low mortality rate for the Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of Africans sold for enslavement were forcibly transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manu ...

.) The company persisted with the slave trade through two wars with Spain and the calamitous 1720 commercial bubble

Bubble, Bubbles or The Bubble may refer to:

Common uses

* Bubble (physics), a globule of one substance in another, usually gas in a liquid

** Soap bubble

* Economic bubble, a situation where asset prices are much higher than underlying fundame ...

. The company's slave trading peaked during 1725, five years after the bubble burst.

The annual ship

The slave Asiento contract of 1713 granted a permit to send one vessel of 500 tons per year, loaded with duty-free merchandise to be sold at the fairs ofNew Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

, Cartagena and Portobello. This was an unprecedented concession that broke two centuries of strict exclusion of foreign merchants from the Spanish Empire, although a quarter of the profit was to be paid to the Spanish Crown.

The first ship to head for the Americas, the ''Royal Prince'', was scheduled for 1714 but was delayed until August 1716. In consideration of the three annual ships missed since the date of the Asiento, the permitted tonnage of the next ten ships was raised to 650. Only seven annual ships sailed during the Asiento, the last one being the ''Royal Caroline'' in 1732. The company's failure to produce accounts for all the annual ships but the first one, and lack of payment of the proceeds to the Spanish Crown from the profits for all the annual ships, resulted in no permits being granted after the ''Royal Caroline'' trip of 1732–1734.

In contrast to the "legitimate" trade in slaves, the regular trade of the annual ships generated healthy returns, in some case profits were over 100%. Accounts for the voyage of the ''Royal Prince'' were not presented until 1733, following continuous demands by Spanish officials. They reported profits of £43,607. Since the King of Spain was entitled to 25% of the profits, after deducting interest on a loan he claimed £8,678. The South Sea Company never paid the amount due for the first annual ship to the Spanish Crown, nor did it pay any amount for any of the other six trips.

Arctic whaling

The Greenland Company had been established by an act of Parliament, the Greenland Trade Act 1692 ( 4 Will. & Mar. c. 17) in 1693 with the object of catching whales in the Arctic. The products of their "whale-fishery" were to be free of customs and other duties. Partly due to maritime disruption caused by wars with France, the Greenland Company failed financially within a few years. In 1722 Henry Elking published a proposal, directed at the governors of the South Sea Company, that they should resume the "Greenland Trade" and send ships to catch whales in the Arctic. He made very detailed suggestions about how the ships should be crewed and equipped. The British Parliament confirmed that a British Arctic "whale-fishery" would continue to benefit from freedom from customs duties, and in 1724 the South Sea Company decided to commence whaling. They had 12 whale-ships built on the River Thames and these went to the Greenland seas in 1725. Further ships were built in later years, but the venture was not successful. There were hardly any experienced whalemen remaining in Britain, and the company had to engage Dutch and Danish whalemen for the key posts aboard their ships: for instance all commanding officers and harpooners were hired from theNorth Frisia

North Frisia (; ; ; ; ) is the northernmost portion of Frisia, located in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, between the rivers Eider River, Eider and Vidå, Wiedau. It also includes the North Frisian Islands and Heligoland. The region is traditionally ...

n island of Föhr

Föhr (; ''Fering'' North Frisian: ''Feer''; ) is one of the North Frisian Islands on the German coast of the North Sea. It is part of the Nordfriesland district in the federal state of Schleswig-Holstein. Föhr is the second-largest North Sea ...

. Other costs were badly controlled and the catches remained disappointingly few, even though the company was sending up to 25 ships to Davis Strait

The Davis Strait (Danish language, Danish: ''Davisstrædet'') is a southern arm of the Arctic Ocean that lies north of the Labrador Sea. It lies between mid-western Greenland and Baffin Island in Nunavut, Canada. To the north is Baffin Bay. The ...

and the Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

seas in some years. By 1732 the company had accumulated a net loss of £177,782 from their eight years of Arctic whaling.

The South Sea Company directors appealed to the British government for further support. Parliament had passed an act of Parliament in 1732 that extended the duty-free concessions for a further nine years. In 1733 the Whale Fishery Act 1732 ( 6 Geo. 2. c. 33) was passed that also granted a government subsidy to British Arctic whalers, the first in a long series of such acts of Parliament that continued and modified the whaling subsidies throughout the 18th century. This, and the subsequent acts, required the whalers to meet conditions regarding the crewing and equipping of the whale-ships that closely resembled the conditions suggested by Elking in 1722. In spite of the extended duty-free concessions, and the prospect of real subsidies as well, the court and directors of the South Sea Company decided that they could not expect to make profits from Arctic whaling. They sent out no more whale-ships after the loss-making 1732 season.

Government debt after the Seven Years' War

The company continued its trade (when not interrupted by war) until the end of theSeven Years' War