Social Insect on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Eusociality (

Eusociality (

E. O. Wilson extended the concept to include other social insects, such as ants, wasps, and termites. Originally, it was defined to include organisms (only invertebrates) that fulfilled the same three criteria defined by Michener.

Eusociality was then discovered in a group of

E. O. Wilson extended the concept to include other social insects, such as ants, wasps, and termites. Originally, it was defined to include organisms (only invertebrates) that fulfilled the same three criteria defined by Michener.

Eusociality was then discovered in a group of

The order

The order  Reproductive specialization in Hymenoptera generally involves the production of sterile members of the species, which carry out specialized tasks to care for the reproductive members. Individuals may have behavior and morphology modified for group defense, including self-sacrificing behavior. For example, members of the sterile caste of the honeypot ants such as '' Myrmecocystus'' fill their abdomens with liquid food until they become immobile and hang from the ceilings of the underground nests, acting as food storage for the rest of the colony. Not all social hymenopterans have distinct morphological differences between castes. For example, in the Neotropical social wasp '' Synoeca surinama'', caste ranks are determined by social displays in the developing brood. Castes are sometimes further specialized in their behavior based on age, as in '' Scaptotrigona postica'' workers. Between approximately 0–40 days old, the workers perform tasks within the nest such as provisioning cell broods, colony cleaning, and nectar reception and dehydration. Once older than 40 days, ''S. postica'' workers move outside the nest for colony defense and foraging.

Reproductive specialization in Hymenoptera generally involves the production of sterile members of the species, which carry out specialized tasks to care for the reproductive members. Individuals may have behavior and morphology modified for group defense, including self-sacrificing behavior. For example, members of the sterile caste of the honeypot ants such as '' Myrmecocystus'' fill their abdomens with liquid food until they become immobile and hang from the ceilings of the underground nests, acting as food storage for the rest of the colony. Not all social hymenopterans have distinct morphological differences between castes. For example, in the Neotropical social wasp '' Synoeca surinama'', caste ranks are determined by social displays in the developing brood. Castes are sometimes further specialized in their behavior based on age, as in '' Scaptotrigona postica'' workers. Between approximately 0–40 days old, the workers perform tasks within the nest such as provisioning cell broods, colony cleaning, and nectar reception and dehydration. Once older than 40 days, ''S. postica'' workers move outside the nest for colony defense and foraging.

Some gall-inducing insects, including the

Some gall-inducing insects, including the

One plant, the

One plant, the

According to

According to

Among ants, the queen pheromone system of the fire ant '' Solenopsis invicta'' includes both releaser and primer pheromones. A queen recognition (releaser) pheromone is stored in the poison sac along with three other compounds. These compounds elicit a behavioral response from workers. Several primer effects have also been demonstrated. Pheromones initiate reproductive development in new winged females, called female sexuals. These chemicals inhibit workers from rearing male and female sexuals, suppress egg production in other queens of multiple queen colonies, and cause workers to execute excess queens. These pheromones maintain the eusocial phenotype, with one queen supported by sterile workers and sexually active males ( drones). In queenless colonies, the lack of queen pheromones causes winged females to quickly shed their wings, develop ovaries and lay eggs. These virgin replacement queens assume the role of the queen and start to produce queen pheromones. Similarly, queen weaver ants '' Oecophylla longinoda'' have exocrine glands that produce pheromones which prevent workers from laying reproductive eggs.

Similar mechanisms exist in the eusocial wasp '' Vespula vulgaris''. For a queen to dominate all the workers, usually numbering more than 3000 in a colony, she signals her dominance with pheromones. The workers regularly lick the queen while feeding her, and the air-borne

Among ants, the queen pheromone system of the fire ant '' Solenopsis invicta'' includes both releaser and primer pheromones. A queen recognition (releaser) pheromone is stored in the poison sac along with three other compounds. These compounds elicit a behavioral response from workers. Several primer effects have also been demonstrated. Pheromones initiate reproductive development in new winged females, called female sexuals. These chemicals inhibit workers from rearing male and female sexuals, suppress egg production in other queens of multiple queen colonies, and cause workers to execute excess queens. These pheromones maintain the eusocial phenotype, with one queen supported by sterile workers and sexually active males ( drones). In queenless colonies, the lack of queen pheromones causes winged females to quickly shed their wings, develop ovaries and lay eggs. These virgin replacement queens assume the role of the queen and start to produce queen pheromones. Similarly, queen weaver ants '' Oecophylla longinoda'' have exocrine glands that produce pheromones which prevent workers from laying reproductive eggs.

Similar mechanisms exist in the eusocial wasp '' Vespula vulgaris''. For a queen to dominate all the workers, usually numbering more than 3000 in a colony, she signals her dominance with pheromones. The workers regularly lick the queen while feeding her, and the air-borne

International Union for the Study of Social Insects

{{Collective animal behaviour Behavioral ecology Superorganisms Sociobiology 1960s neologisms

Eusociality (

Eusociality (Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

'good' and social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

) is the highest level of organization of sociality

Sociality is the degree to which individuals in an animal population tend to associate in social groups (gregariousness) and form cooperative societies.

Sociality is a survival response to evolutionary pressures. For example, when a mother ...

. It is defined by the following characteristics: cooperative brood care (including care of offspring

In biology, offspring are the young creation of living organisms, produced either by sexual reproduction, sexual or asexual reproduction. Collective offspring may be known as a brood or progeny. This can refer to a set of simultaneous offspring ...

from other individuals), overlapping generations within a colony of adults, and a division of labor into reproductive

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are al ...

and non-reproductive groups. The division of labor creates specialized behavioral groups within an animal society, sometimes called castes. Eusociality is distinguished from all other social systems because individuals of at least one caste usually lose the ability to perform behaviors characteristic of individuals in another caste. Eusocial colonies can be viewed as superorganism

A superorganism, or supraorganism, is a group of synergetically interacting organisms of the same species. A community of synergetically interacting organisms of different species is called a '' holobiont''.

Concept

The term superorganism is ...

s.

Eusociality has evolved among the insect

Insects (from Latin ') are Hexapoda, hexapod invertebrates of the class (biology), class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body (Insect morphology#Head, head, ...

s, crustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

s, trematoda

Trematoda is a class of flatworms known as trematodes, and commonly as flukes. They are obligate internal parasites with a complex life cycle requiring at least two hosts. The intermediate host, in which asexual reproduction occurs, is a mol ...

and mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. It is most widespread in the Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is a large order of insects, comprising the sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants. Over 150,000 living species of Hymenoptera have been described, in addition to over 2,000 extinct ones. Many of the species are parasitic.

Females typi ...

(ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s, bees, and wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

s) and in Isoptera (termite

Termites are a group of detritivore, detritophagous Eusociality, eusocial cockroaches which consume a variety of Detritus, decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, Plant litter, leaf litter, and Humus, soil humus. They are dist ...

s). A colony has caste differences: queens and reproductive

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are al ...

males

Male (symbol: ♂) is the sex of an organism that produces the gamete (sex cell) known as sperm, which fuses with the larger female gamete, or ovum, in the process of fertilisation. A male organism cannot reproduce sexually without access to ...

take the roles of the sole reproducers, while soldiers and workers work together to create and maintain a living situation favorable for the brood. Queens produce multiple queen pheromones to create and maintain the eusocial state in their colonies; they may also eat eggs laid by other females or exert dominance by fighting. There are two eusocial rodent

Rodents (from Latin , 'to gnaw') are mammals of the Order (biology), order Rodentia ( ), which are characterized by a single pair of continuously growing incisors in each of the upper and Mandible, lower jaws. About 40% of all mammal specie ...

s: the naked mole-rat

The naked mole-rat (''Heterocephalus glaber''), also known as the sand puppy, is a burrowing rodent native to the Horn of Africa and parts of Kenya, notably in Somali regions. It is closely related to the blesmols and is the only species in th ...

and the Damaraland mole-rat

The Damaraland mole-rat (''Fukomys damarensis''), Damara mole rat or Damaraland blesmol, is a burrowing rodent found in southern Africa. Along with the smaller, less hairy, naked mole rat, it is a species of eusociality, eusocial mammal. Descript ...

. Some shrimp

A shrimp (: shrimp (American English, US) or shrimps (British English, UK)) is a crustacean with an elongated body and a primarily Aquatic locomotion, swimming mode of locomotion – typically Decapods belonging to the Caridea or Dendrobranchi ...

s, such as ''Synalpheus regalis

''Synalpheus regalis'' is a species of snapping shrimp that commonly live in sponges in the coral reefs along the tropical West Atlantic. They form a prominent component of the diverse marine cryptofauna of the region. For the span of their e ...

'', are eusocial. E. O. Wilson and others have claimed that human

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

s have evolved a weak form of eusociality. It has been suggested that the colonial and epiphytic

An epiphyte is a plant or plant-like organism that grows on the surface of another plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphyt ...

staghorn fern

''Platycerium'' is a genus of about 18 fern species in the polypod family, Polypodiaceae. Ferns in this genus are widely known as staghorn or elkhorn ferns due to their uniquely shaped fronds. This genus is Epiphyte, epiphytic and is native to tr ...

, too, may make use of a primitively eusocial division of labor.

History

The term "eusocial" was introduced in 1966 bySuzanne Batra

Suzanne Wellington Tubby Batra (born December 15, 1937) is an American entomologist best known for her work on the classification of insect societies and for coining the term eusociality.

Education and career

Batra graduated from Saranac Lake ...

, who used it to describe nesting behavior in Halictid bees, on a scale of subsocial/solitary, colonial/communal, semisocial, and eusocial, where a colony is started by a single individual. Batra observed the cooperative behavior of the bees, males and females alike, as they took responsibility for at least one duty (i.e., burrowing, cell construction, oviposition

The ovipositor is a tube-like organ used by some animals, especially insects, for the laying of eggs. In insects, an ovipositor consists of a maximum of three pairs of appendages. The details and morphology of the ovipositor vary, but typica ...

) within the colony. The cooperativeness was essential as the activity of one labor division greatly influenced the activity of another. Eusocial colonies can be viewed as superorganism

A superorganism, or supraorganism, is a group of synergetically interacting organisms of the same species. A community of synergetically interacting organisms of different species is called a '' holobiont''.

Concept

The term superorganism is ...

s, with individual castes being analogous to different tissue or cell types in a multicellular organism

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell (biology), cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, Embryophyte, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organism ...

; castes fulfill a specific role that contributes to the functioning and survival of the whole colony, while being incapable of independent survival outside the colony.

In 1969, Charles D. Michener further expanded Batra's classification with his comparative study of social behavior in bees. He observed multiple species of bees (Apoidea

The superfamily Apoidea is a major group (of over 30 000 species) within the Hymenoptera, which includes two traditionally recognized lineages, the "sphecoid" wasps, and the bees. Molecular phylogeny demonstrates that the bees arose from ...

) in order to investigate the different levels of animal sociality, many of which are different stages that a colony may pass through. Eusociality, which is the highest level of animal sociality a species can attain, specifically had three characteristics that distinguished it from the other levels:

# Egg-layers and worker-like individuals among adult females (reproductive division of labor, with or without sterile castes)

# The overlap of generations (mother and adult offspring)

# Cooperative care of the brood

E. O. Wilson extended the concept to include other social insects, such as ants, wasps, and termites. Originally, it was defined to include organisms (only invertebrates) that fulfilled the same three criteria defined by Michener.

Eusociality was then discovered in a group of

E. O. Wilson extended the concept to include other social insects, such as ants, wasps, and termites. Originally, it was defined to include organisms (only invertebrates) that fulfilled the same three criteria defined by Michener.

Eusociality was then discovered in a group of chordates

A chordate ( ) is a bilaterian animal belonging to the phylum Chordata ( ). All chordates possess, at some point during their larval or adult stages, five distinctive physical characteristics ( synapomorphies) that distinguish them from ot ...

, the mole-rats. Some researchers have argued that another possibly important criterion for eusociality is "the point of no return". This is characterized by having individuals fixed into one behavioral group, usually before reproductive maturity. This prevents them from transitioning between behavioral groups, and creates a society with individuals truly dependent on each other for survival and reproductive success. For many insects, this irreversibility has changed the anatomy of the worker caste, which is sterile and provides support for the reproductive caste. Other researchers have suggested that cooperative breeding and eusociality are not discrete phenomena, but rather form a continuum of fundamentally similar social systems whose main differences lie in the distribution of lifetime reproductive success among group members. Vertebrate and invertebrate cooperative breeders can be arrayed along a common axis, that represents a standardized measure of reproductive variance. In this view, loaded terms like “primitive” and “advanced” eusociality should be dropped. An advantage of this approach is that it unites all occurrences of alloparental helping of kin under a single theoretical umbrella (e.g., Hamilton's rule). Thus, cooperatively breeding vertebrates can be regarded as eusocial, just as eusocial invertebrates are cooperative breeders.

Diversity

Most eusocial societies exist inarthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s, while a few are found in mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s. Some fern

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissue ...

s may exhibit a form of eusocial behavior.

In insects

Eusociality has evolved multiple times in different insect orders, including hymenopterans, termites, thrips, aphids, and beetles.In hymenopterans

The order

The order Hymenoptera

Hymenoptera is a large order of insects, comprising the sawflies, wasps, bees, and ants. Over 150,000 living species of Hymenoptera have been described, in addition to over 2,000 extinct ones. Many of the species are parasitic.

Females typi ...

contains the largest group of eusocial insects, including ant

Ants are Eusociality, eusocial insects of the Family (biology), family Formicidae and, along with the related wasps and bees, belong to the Taxonomy (biology), order Hymenoptera. Ants evolved from Vespoidea, vespoid wasp ancestors in the Cre ...

s, bees, and wasp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

s—divided into castes: reproductive queens

Queens is the largest by area of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located near the western end of Long Island, it is bordered by the ...

, drones, more or less sterile

Sterile or sterility may refer to:

*Asepsis, a state of being free from biological contaminants

* Sterile (archaeology), a sediment deposit which contains no evidence of human activity

*Sterilization (microbiology), any process that eliminates or ...

workers, and sometimes also soldiers that perform specialized tasks. In the well-studied social wasp '' Polistes versicolor'', dominant females perform tasks such as building new cells and ovipositing, while subordinate females tend to perform tasks like feeding the larvae and foraging. The task differentiation between castes can be seen in the fact that subordinates complete 81.4% of the total foraging activity, while dominants only complete 18.6% of the total foraging. Eusocial species with a sterile caste are sometimes called hypersocial.

While only a moderate percentage of species in bees (families Apidae

Apidae is the largest family within the superfamily Apoidea, containing at least 5700 species of bees. The family includes some of the most commonly seen bees, including bumblebees and honey bees, but also includes stingless bees (also used for ...

and Halictidae

Halictidae is the second-largest family of bees (clade Anthophila) with nearly 4,500 species. They are commonly called sweat bees (especially the smaller species), as they are often attracted to perspiration. Halictid species are an extremely div ...

) and wasps (Crabronidae

The Crabronidae is a large family of wasps within the superfamily Apoidea.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

This family has historically been treated as a subfamily in the now-defunct Spheciformes group under the family Sphecidae. The Spheciformes inclu ...

and Vespidae

The Vespidae are a large (nearly 5000 species), diverse, cosmopolitan family of wasps, including nearly all the known eusocial wasps (such as '' Polistes fuscatus'', '' Vespa orientalis'', and ''Vespula germanica'') and many solitary wasps. Eac ...

) are eusocial, nearly all species of ants ( Formicidae) are eusocial. Some major lineages of wasps are mostly or entirely eusocial, including the subfamilies Polistinae

The Polistinae is a subfamily of eusocial wasps belonging to the family Vespidae. They are closely related to the wasps (“yellowjackets” as they are called in North America) and true hornets of the subfamily Vespinae, containing four tribes ...

and Vespinae. The corbiculate bees (subfamily Apinae of family Apidae

Apidae is the largest family within the superfamily Apoidea, containing at least 5700 species of bees. The family includes some of the most commonly seen bees, including bumblebees and honey bees, but also includes stingless bees (also used for ...

) contain four tribes of varying degrees of sociality: the highly eusocial Apini

A honey bee (also spelled honeybee) is a eusocial flying insect within the genus ''Apis'' of the bee clade, all native to mainland Afro-Eurasia. After bees spread naturally throughout Africa and Eurasia, humans became responsible for the c ...

(honey bees) and Meliponini

Stingless bees (SB), sometimes called stingless honey bees or simply meliponines, are a large group of bees (from about 462 to 552 described species), comprising the Tribe (biology), tribe Meliponini (or subtribe Meliponina according to other aut ...

(stingless bees), primitively eusocial Bombini

The Bombini are a tribe of large bristly apid bees which feed on pollen or nectar. Many species are social, forming nests of up to a few hundred individuals; other species, formerly classified as ''Psithyrus'' cuckoo bees, are brood parasites of ...

(bumble bees), and the mostly solitary or weakly social Euglossini

The tribe (biology), tribe Euglossini, in the subfamily Apinae, commonly known as orchid bees or euglossine bees, are the only group of Pollen basket, corbiculate bees whose non-parasitic members do not all possess Eusociality, eusocial behavior. ...

(orchid bees). Eusociality in these families is sometimes managed by a set of pheromones that alter the behavior of specific castes in the colony. These pheromones may act across different species, as observed in '' Apis andreniformis'' (black dwarf honey bee), where worker bees responded to queen pheromone from the related '' Apis florea'' (red dwarf honey bee). Pheromones are sometimes used in these castes to assist with foraging. Workers of the Australian stingless bee ''Tetragonula carbonaria

''Tetragonula carbonaria'' (previously known as ''Trigona carbonaria'') is a stingless bee, endemism, endemic to the north-east coast of Australia. Its common name is sugarbag bee. They are also occasionally referred to as bush bees. The bee is k ...

'', for instance, mark food sources with a pheromone, helping their nest mates to find the food.

Beside corbiculate bees, eusociality is documented within Apidae in xylocopine bees, where only simple colonies containing one or two "worker" females have been documented in the tribes Xylocopini and Ceratinini, though some members of Allodapini have larger eusocial colonies. Similarly, in the Colletidae

The Colletidae are a family (biology), family of bees, and are often referred to collectively as plasterer bees or polyester bees, due to the method of smoothing the walls of their nest cells with secretions applied with their mouthparts; these s ...

, there is only one species reported to exhibit any form of social behavior; occasional nests of the species '' Amphylaeus morosus'' contain a female and a "guard" (a sister or daughter of the female that founded the nest), creating very small social colonies, where both females are capable of reproduction though only the foundress female appears to lay eggs. In Halictidae

Halictidae is the second-largest family of bees (clade Anthophila) with nearly 4,500 species. They are commonly called sweat bees (especially the smaller species), as they are often attracted to perspiration. Halictid species are an extremely div ...

(sweat bees), by contrast, eusociality is well-documented in hundreds of species, primarily in the genera '' Halictus'' and '' Lasioglossum''. In '' Lasioglossum aeneiventre'', a halictid bee from Central America, nests may be headed by more than one female; such nests have more cells, and the number of active cells per female is correlated with the number of females in the nest, implying that having more females leads to more efficient building and provisioning of cells. In several species with only one queen, such as '' Lasioglossum malachurum'' in Europe, or '' Halictus rubicundus'' in North America, the degree of eusociality depends on the clime in which the species is found - they are solitary in colder climates and social in warmer climates.

Reproductive specialization in Hymenoptera generally involves the production of sterile members of the species, which carry out specialized tasks to care for the reproductive members. Individuals may have behavior and morphology modified for group defense, including self-sacrificing behavior. For example, members of the sterile caste of the honeypot ants such as '' Myrmecocystus'' fill their abdomens with liquid food until they become immobile and hang from the ceilings of the underground nests, acting as food storage for the rest of the colony. Not all social hymenopterans have distinct morphological differences between castes. For example, in the Neotropical social wasp '' Synoeca surinama'', caste ranks are determined by social displays in the developing brood. Castes are sometimes further specialized in their behavior based on age, as in '' Scaptotrigona postica'' workers. Between approximately 0–40 days old, the workers perform tasks within the nest such as provisioning cell broods, colony cleaning, and nectar reception and dehydration. Once older than 40 days, ''S. postica'' workers move outside the nest for colony defense and foraging.

Reproductive specialization in Hymenoptera generally involves the production of sterile members of the species, which carry out specialized tasks to care for the reproductive members. Individuals may have behavior and morphology modified for group defense, including self-sacrificing behavior. For example, members of the sterile caste of the honeypot ants such as '' Myrmecocystus'' fill their abdomens with liquid food until they become immobile and hang from the ceilings of the underground nests, acting as food storage for the rest of the colony. Not all social hymenopterans have distinct morphological differences between castes. For example, in the Neotropical social wasp '' Synoeca surinama'', caste ranks are determined by social displays in the developing brood. Castes are sometimes further specialized in their behavior based on age, as in '' Scaptotrigona postica'' workers. Between approximately 0–40 days old, the workers perform tasks within the nest such as provisioning cell broods, colony cleaning, and nectar reception and dehydration. Once older than 40 days, ''S. postica'' workers move outside the nest for colony defense and foraging.

In termites

Termite

Termites are a group of detritivore, detritophagous Eusociality, eusocial cockroaches which consume a variety of Detritus, decaying plant material, generally in the form of wood, Plant litter, leaf litter, and Humus, soil humus. They are dist ...

s (order Blattodea

Blattodea is an order (biology), order of insects that contains cockroaches and termites. Formerly, termites were considered a separate order, Isoptera, but genetics, genetic and molecular evidence suggests they evolved from within the cockroach ...

, infraorder Isoptera) make up another large portion of highly advanced eusocial animals. The colony is differentiated into various castes: the queen and king are the sole reproducing individuals; workers forage and maintain food and resources; and soldiers defend the colony against ant attacks. The latter two castes, which are sterile and perform highly specialized, complex social behaviors, are derived from different stages of pluripotent

Cell potency is a cell's ability to differentiate into other cell types.

The more cell types a cell can differentiate into, the greater its potency. Potency is also described as the gene activation potential within a cell, which like a continuum ...

larvae produced by the reproductive caste. Some soldiers have jaws so enlarged (specialized for defense and attack) that they are unable to feed themselves and must be fed by workers.

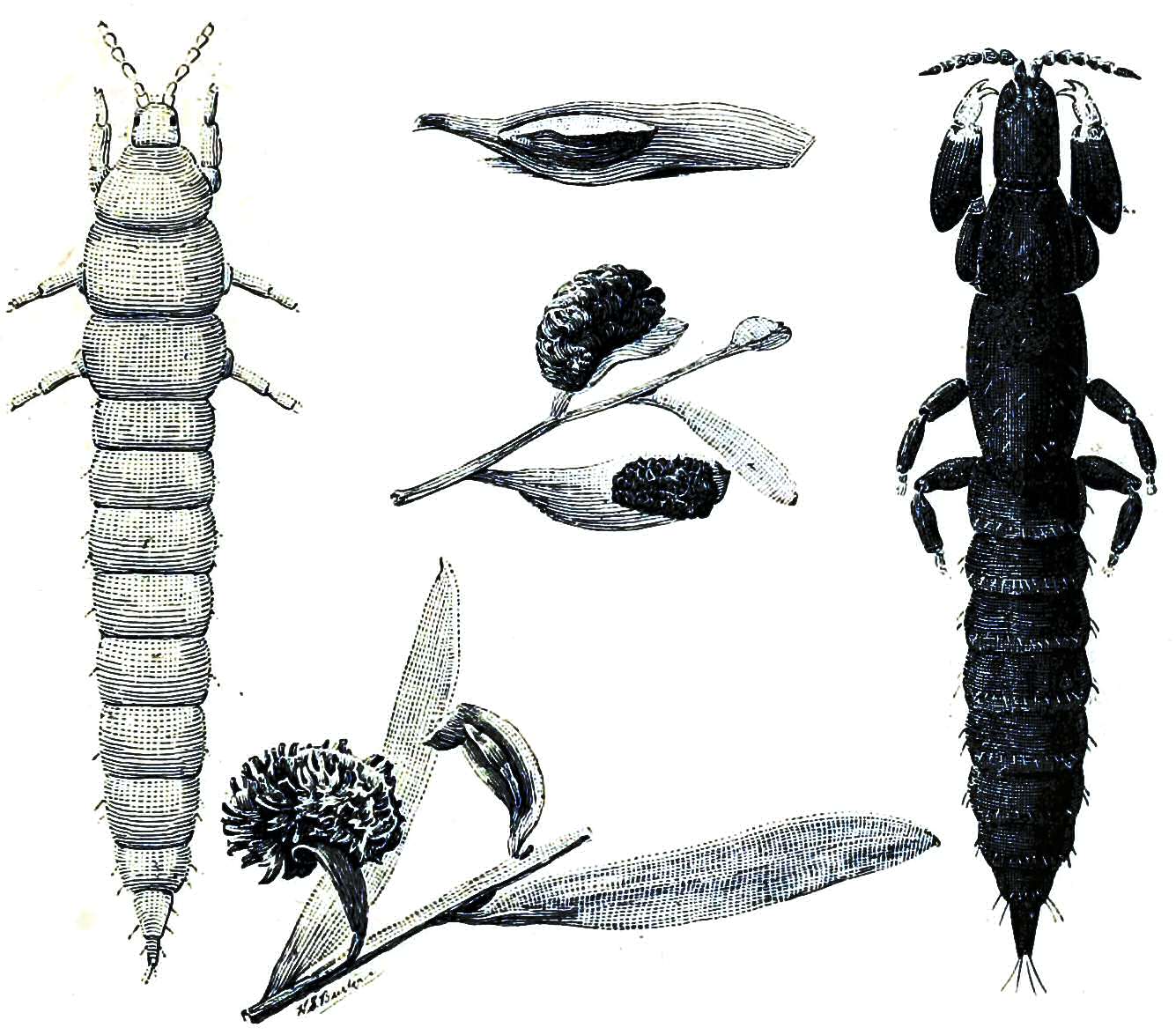

In beetles

'' Austroplatypus incompertus'' is a species ofambrosia beetle

Ambrosia beetles are beetles of the weevil subfamilies Scolytinae and Platypodinae (Coleoptera, Curculionidae), which live in nutritional symbiosis with ambrosia fungi. The beetles excavate tunnels in dead or stressed trees into which they introduc ...

native to Australia, and is the first beetle (order Coleoptera

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

) to be recognized as eusocial. This species forms colonies in which a single female is fertilized, and is protected by many unfertilized females, which serve as workers excavating tunnels in trees. This species has cooperative brood care, in which individuals care for juveniles that are not their own.

In gall-inducing insects

Some gall-inducing insects, including the

Some gall-inducing insects, including the gall

Galls (from the Latin , 'oak-apple') or ''cecidia'' (from the Greek , anything gushing out) are a kind of swelling growth on the external tissues of plants. Plant galls are abnormal outgrowths of plant tissues, similar to benign tumors or war ...

-forming aphid

Aphids are small sap-sucking insects in the Taxonomic rank, family Aphididae. Common names include greenfly and blackfly, although individuals within a species can vary widely in color. The group includes the fluffy white Eriosomatinae, woolly ...

, '' Pemphigus spyrothecae'' (order Hemiptera

Hemiptera (; ) is an order of insects, commonly called true bugs, comprising more than 80,000 species within groups such as the cicadas, aphids, planthoppers, leafhoppers, assassin bugs, bed bugs, and shield bugs. They range in size from ...

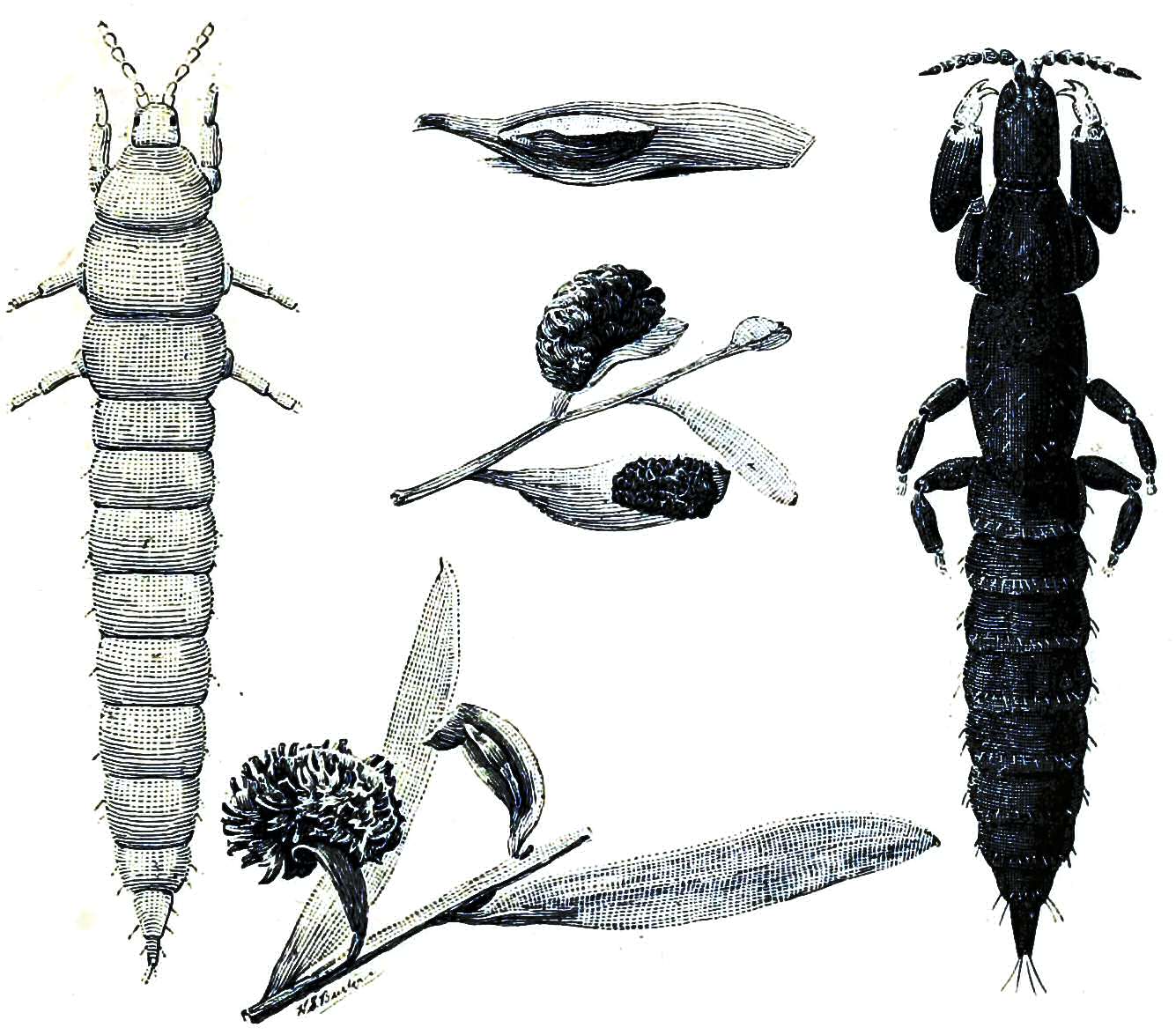

), and thrips

Thrips (Order (biology) , order Thysanoptera) are minute (mostly long or less), slender insects with fringed wings and unique asymmetrical mouthparts. Entomologists have species description , described approximately 7,700 species. They fly on ...

such as '' Kladothrips'' (order Thysanoptera), are described as eusocial. These species have very high relatedness among individuals due to their asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that does not involve the fusion of gametes or change in the number of chromosomes. The offspring that arise by asexual reproduction from either unicellular or multicellular organisms inherit the f ...

(sterile soldier castes being clones produced by parthenogenesis

Parthenogenesis (; from the Greek + ) is a natural form of asexual reproduction in which the embryo develops directly from an egg without need for fertilization. In animals, parthenogenesis means the development of an embryo from an unfertiliz ...

), but the gall-inhabiting behavior gives these species a defensible resource. They produce soldier castes for fortress defense and protection of the colony against predators, kleptoparasite

Kleptoparasitism (originally spelt clepto-parasitism, meaning "parasitism by theft") is a form of feeding in which one animal deliberately takes food from another. The strategy is Evolutionarily stable strategy, evolutionarily stable when stealin ...

s, and competitors. In these groups, eusociality is produced by both high relatedness and by living in a restricted, shared area.

In crustaceans

Eusociality has evolved in three different lineages in the colonialcrustacean

Crustaceans (from Latin meaning: "those with shells" or "crusted ones") are invertebrate animals that constitute one group of arthropods that are traditionally a part of the subphylum Crustacea (), a large, diverse group of mainly aquatic arthrop ...

genus '' Synalphaeus''. '' S. regalis'', '' S. microneptunus'', ''S. filidigitus'', ''S. elizabethae'', ''S. chacei'', ''S. riosi'', ''S. duffyi'', and ''S. cayoneptunus'' are the eight recorded species of parasitic shrimp that rely on fortress defense and live in groups of closely related individuals in tropical reefs and sponges. They live eusocially with a single breeding female, and a large number of male defenders armed with enlarged snapping claws. There is a single shared living space for the colony members, and the non-breeding members act to defend it.

The fortress defense hypothesis additionally points out that because sponges provide both food and shelter, there is an aggregation of relatives (because the shrimp do not have to disperse to find food), and much competition for those nesting sites. Being the target of attack promotes a good defense system (soldier caste); soldiers promote the fitness of the whole nest by ensuring safety and reproduction of the queen.

Eusociality offers a competitive advantage in shrimp populations. Eusocial species are more abundant, occupy more of the habitat, and use more of the available resources than non-eusocial species.

In trematodes

The trematodes are a class of parasitic flatworm, also known as flukes. One species, '' Haplorchis pumilio'', has evolved eusociality involving a colony creating a class of sterile soldiers. One fluke invades a host and establishes a colony of dozens to thousands of clones that work together to take it over. Since rival trematode species can invade and replace the colony, it is protected by a specialized caste of sterile soldier trematodes. Soldiers are smaller, more mobile, and develop along a different pathway than sexually mature reproductives. One difference is that a soldier's mouthparts (pharynx) is five times as big as those of the reproductives. They make up nearly a quarter of the volume of the soldier. These soldiers do not have a germinal mass, never metamorphose to be reproductive, and are, therefore, obligately sterile. Soldiers are readily distinguished from the immature and mature reproductive worms. Soldiers are more aggressive than reproductives, attacking heterospecific trematodes that infect their host ''in vitro''. ''H. pumilio'' soldiers do not attack conspecifics from other colonies. The soldiers are not evenly distributed throughout the host body. They are found in the highest numbers in the basal visceral mass, where competing trematodes tend to multiply during the early phase of infection. This strategic positioning allows them to effectively defend against invaders, similar to how soldier distribution patterns are seen in other animals with defensive castes. They "appear to be an obligately sterile physical caste, akin to that of the most advanced social insects".In nonhuman mammals

Among mammals, two species in the rodent group Phiomorpha are eusocial, thenaked mole-rat

The naked mole-rat (''Heterocephalus glaber''), also known as the sand puppy, is a burrowing rodent native to the Horn of Africa and parts of Kenya, notably in Somali regions. It is closely related to the blesmols and is the only species in th ...

(''Heterocephalus glaber'') and the Damaraland mole-rat

The Damaraland mole-rat (''Fukomys damarensis''), Damara mole rat or Damaraland blesmol, is a burrowing rodent found in southern Africa. Along with the smaller, less hairy, naked mole rat, it is a species of eusociality, eusocial mammal. Descript ...

(''Fukomys damarensis''), both of which are highly inbred

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders an ...

. These mole-rats live in harsh, limiting environments, where dispersal is difficult and dangerous and cooperation is required to find food and defend against predators. Most colony members are workers, and they cooperatively care for offspring of a single reproductive female (the queen) to whom they are closely related. These mole-rats are eusocial under any definition of the term. Interestingly, the discovery of male and female dispersers has revealed that there is a mechanism of inter-colony outbreeding in naked mole-rats. Outbreeding reduces intra-colony genetic relatedness, but reduces inbreeding depression. Dispersers are morphologically, physiologically and behaviorally distinct from colony members and actively seek to leave their burrow when an escape opportunity presents itself. These individuals are equipped with generous fat reserves for their journey. Though they possess high levels of luteinizing hormone

Luteinizing hormone (LH, also known as luteinising hormone, lutropin and sometimes lutrophin) is a hormone produced by gonadotropic cells in the anterior pituitary gland. The production of LH is regulated by gonadotropin-releasing hormone (G ...

, dispersers are only interested in mating with individuals from foreign colonies rather than their own colony's queen. They also show little interest in working cooperatively with workers in their natal colony. Hence, disperser morphs are well-prepared to promote the establishment of new, initially outbred colonies, before cycles of inbreeding resume.

Some mammals in the Carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

and Primates

Primates is an order of mammals, which is further divided into the strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and lorisids; and the haplorhines, which include tarsiers and simians ( monkeys and apes). Primates arose 74–63 ...

have eusocial tendencies, especially meerkat

The meerkat (''Suricata suricatta'') or suricate is a small mongoose found in southern Africa. It is characterised by a broad head, large eyes, a pointed snout, long legs, a thin tapering tail, and a brindled coat pattern. The head-and-body ...

s (''Suricata suricatta'') and dwarf mongooses (''Helogale parvula''). These show cooperative breeding and marked reproductive skews. In the dwarf mongoose, the breeding pair receives food priority and protection from subordinates and rarely has to defend against predators.

In humans

Scientists have debated whether humans areprosocial

Prosocial behavior is a social behavior that "benefit other people or society as a whole", "such as helping, sharing, donating, co-operating, and volunteering". The person may or may not intend to benefit others; the behavior's prosocial benefi ...

or eusocial. Edward O. Wilson called humans eusocial apes, arguing for similarities to ants, and observing that early hominins

The Hominini (hominins) form a taxonomic tribe of the subfamily Homininae (hominines). They comprise two extant genera: ''Homo'' (humans) and '' Pan'' (chimpanzees and bonobos), and in standard usage exclude the genus ''Gorilla'' (gorillas), ...

cooperated to rear their children while other members of the same group hunted and foraged. Wilson and others argued that through cooperation and teamwork, ants and humans form superorganisms. Wilson's claims were vigorously rejected by critics of group selection

Group selection is a proposed mechanism of evolution in which natural selection acts at the level of the group, instead of at the level of the individual or gene.

Early authors such as V. C. Wynne-Edwards and Konrad Lorenz argued that the beha ...

theory, which grounded Wilson's argument, and because human reproductive labor is not divided between castes.

Though controversial, it has been suggested that male homosexuality and female menopause could have evolved through kin selection

Kin selection is a process whereby natural selection favours a trait due to its positive effects on the reproductive success of an organism's relatives, even when at a cost to the organism's own survival and reproduction. Kin selection can lead ...

. This would mean that humans sometimes exhibit a type of alloparental behavior known as " helpers at the nest", with juveniles and sexually mature adolescents helping their parents raise subsequent broods, as in some birds, some non-eusocial bees, and meerkat

The meerkat (''Suricata suricatta'') or suricate is a small mongoose found in southern Africa. It is characterised by a broad head, large eyes, a pointed snout, long legs, a thin tapering tail, and a brindled coat pattern. The head-and-body ...

s. These species are not eusocial: they do not have castes, and helpers reproduce on their own if given the opportunity.

In plants

epiphytic

An epiphyte is a plant or plant-like organism that grows on the surface of another plant and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, water (in marine environments) or from debris accumulating around it. The plants on which epiphyt ...

staghorn fern, '' Platycerium bifurcatum'' (Polypodiaceae

Polypodiaceae is a Family (biology), family of ferns. In the Pteridophyte Phylogeny Group classification of 2016 (PPG I), the family includes around 65 genus, genera and an estimated 1,650 species and is placed in the order Polypodiales, suborder ...

), may exhibit a primitive form of eusocial behavior amongst clones. The evidence for this is that individuals live in colonies, where they are structured in different ways, with frond

A frond is a large, divided leaf. In both common usage and botanical nomenclature, the leaves of ferns are referred to as fronds and some botanists restrict the term to this group. Other botanists allow the term frond to also apply to the lar ...

s of differing size and shape, to collect and store water and nutrients for the colony to use. At the top of a colony, there are both pleated fan-shaped "nest" fronds that collect and hold water, and gutter-shaped "strap" fronds that channel water: no solitary ''Platycerium'' species has both types. At the bottom of a colony, there are "nest" fronds that clasp the trunk of the tree supporting the fern, and drooping photosynthetic fronds. These are argued to be adapted to support the colony structurally, i.e. that the individuals in the colony are to some degree specialized for tasks, a division of labor

The division of labour is the separation of the tasks in any economic system or organisation so that participants may specialise (Departmentalization, specialisation). Individuals, organisations, and nations are endowed with or acquire specialis ...

.

Evolution

Phylogenetic distribution

Eusociality is a rare but widespread phenomenon in species in at least seven orders in the animal kingdom, as shown in thephylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In ...

(non-eusocial groups not shown). All species of termites are eusocial, and it is believed that they were the first eusocial animals to evolve, sometime in the Late Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time scale, geologic time from 161.5 ± 1.0 to 143.1 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic stratum, strata.Owen ...

period (~150 million years ago). The other orders shown contain both eusocial and non-eusocial species, including many lineages where eusociality is inferred to be the ancestral state. Thus the number of independent evolutions of eusociality (clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

s) is not known. The major eusocial groups are shown in boldface in the phylogenetic tree.

Paradox

Prior to thegene-centered view of evolution

The gene-centered view of evolution, gene's eye view, gene selection theory, or selfish gene theory holds that adaptive evolution occurs through the differential survival of competing genes, increasing the allele frequency of those alleles wh ...

, eusociality was seen as paradoxical: if adaptive evolution unfolds by differential reproduction of individual organisms, the evolution of individuals incapable of passing on their genes presents a challenge. In ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life'')The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by M ...

'', Darwin referred to the existence of sterile castes as the "one special difficulty, which at first appeared to me insuperable, and actually fatal to my theory". Darwin anticipated that a possible resolution to the paradox might lie in the close family relationship, which W.D. Hamilton quantified a century later with his 1964 inclusive fitness

Inclusive fitness is a conceptual framework in evolutionary biology first defined by W. D. Hamilton in 1964. It is primarily used to aid the understanding of how social traits are expected to evolve in structured populations. It involves partit ...

theory. After the gene-centered view of evolution was developed in the mid-1970s, non-reproductive individuals were seen as an extended phenotype of the genes, which are the primary beneficiaries of natural selection.

Inclusive fitness and haplodiploidy

Argument that haplodiploidy favors eusociality

inclusive fitness

Inclusive fitness is a conceptual framework in evolutionary biology first defined by W. D. Hamilton in 1964. It is primarily used to aid the understanding of how social traits are expected to evolve in structured populations. It involves partit ...

theory, organisms can gain fitness by increasing the reproductive output of other individuals that share their genes, especially their close relatives. Natural selection favors individuals to help their relatives when the cost of helping is less than the benefit gained by their relative multiplied by the fraction of genes that they share, i.e. when ''Cost < relatedness * Benefit''. W. D. Hamilton suggested in 1964 that eusociality could evolve more easily among haplodiploid

Haplodiploidy is a sex-determination system in which males develop from unfertilized eggs and are haploid, and females develop from fertilized eggs and are diploid. Haplodiploidy is sometimes called arrhenotoky.

Haplodiploidy determines the se ...

species such as Hymenoptera, because of their unusual relatedness structure.

In haplodiploid species, females develop from fertilized eggs and males develop from unfertilized eggs. Because a male is haploid, his daughters share 100% of his genes and 50% of their mother's. Therefore, they share 75% of their genes with each other. This mechanism of sex determination gives rise to what W. D. Hamilton first termed "supersisters", more closely related to their sisters than they would be to their own offspring. Even though workers often do not reproduce, they can pass on more of their genes by helping to raise their sisters than by having their own offspring (each of which would only have 50% of their genes). This unusual situation, where females may have greater fitness when they help rear sisters rather than producing offspring, is often invoked to explain the multiple independent evolutions of eusociality (at least nine separate times) within the Hymenoptera.

Argument that haplodiploidy does not favor eusociality

Against the supposed benefits of haplodiploidy for eusociality,Robert Trivers

Robert Ludlow "Bob" Trivers (; born February 19, 1943) is an American evolutionary biologist and sociobiologist. Trivers proposed the theories of reciprocal altruism (1971), parental investment (1972), facultative sex ratio determination (197 ...

notes that while females share 75% of genes with their sisters in haplodiploid populations, they only share 25% of their genes with their brothers. Accordingly, the average relatedness of an individual to their sibling is 50%. Therefore, helping behavior is only advantageous if it is biased to helping sisters, which would drive the population to a 1:3 sex ratio of males to females. At this ratio, males, as the rarer sex, increase in reproductive value, reducing the benefit of female-biased investment.

Further, not all eusocial species are haplodiploid: termites, some snapping shrimps, and mole rats are not. Conversely, non-eusocial bees are also haplodiploid, and among eusocial species many queens mate with multiple males, resulting in a hive of half-sisters that share only 25% of their genes. The association between haplodiploidy and eusociality is below statistical significance. Haplodiploidy is thus neither necessary nor sufficient for eusociality to emerge. Relatedness does still play a part, as monogamy (queens mating singly) is the ancestral state for all eusocial species so far investigated. If kin selection is an important force driving the evolution of eusociality, monogamy should be the ancestral state, because it maximizes the relatedness of colony members.

Evolutionary ecology

Increased parasitism and predation rates are the primary ecological drivers of social organization. Group living affords colony members defense against enemies, specifically predators, parasites, and competitors, and allows them to gain advantage from superior foraging methods. The importance of ecology in the evolution of eusociality is supported by evidence such as experimentally induced reproductive division of labor, for example when normally solitary queens are forced together. Conversely, femaleDamaraland mole-rat

The Damaraland mole-rat (''Fukomys damarensis''), Damara mole rat or Damaraland blesmol, is a burrowing rodent found in southern Africa. Along with the smaller, less hairy, naked mole rat, it is a species of eusociality, eusocial mammal. Descript ...

s undergo hormonal changes that promote dispersal after periods of high rainfall.

Climate too appears to be a selective agent driving social complexity; across bee lineages and Hymenoptera in general, higher forms of sociality are more likely to occur in tropical than temperate environments. Similarly, social transitions within halictid bees, where eusociality has been gained and lost multiple times, are correlated with periods of climatic warming. Social behavior in facultative social bees is often reliably predicted by ecological conditions, and switches in behavioral type have been experimentally induced by translocating offspring of solitary or social populations to warm and cool climates. In ''H. rubicundus'', females produce a single brood in cooler regions and two or more broods in warmer regions, so the former populations are solitary while the latter are social. In another species of sweat bees, ''L. calceatum'', social phenotype has been predicted by altitude and micro-habitat composition, with social nests found in warmer, sunnier sites, and solitary nests found in adjacent, cooler, shaded locations. Facultatively social bee species, however, which comprise the majority of social bee diversity, have their lowest diversity in the tropics, being largely limited to temperate regions.

Multilevel selection

Once pre-adaptations such as group formation, nest building, high cost of dispersal, and morphological variation are present, between-group competition has been suggested as a driver of the transition to advanced eusociality. M. A. Nowak, C. E. Tarnita, and E. O. Wilson proposed in 2010 that since eusociality produces an extremely altruistic society, eusocial groups should out-reproduce their less cooperative competitors, eventually eliminating all non-eusocial groups from a species. Multilevel selection has been heavily criticized for its conflict with thekin selection

Kin selection is a process whereby natural selection favours a trait due to its positive effects on the reproductive success of an organism's relatives, even when at a cost to the organism's own survival and reproduction. Kin selection can lead ...

theory.

Reversal to solitarity

A reversal to solitarity is an evolutionary phenomenon in which descendants of a eusocial group evolve solitary behavior once again. Bees have been model organisms for the study of reversal to solitarity, because of the diversity of their social systems. Each of the four origins of eusociality in bees was followed by at least one reversal to solitarity, giving a total of at least nine reversals. In a few species, solitary and eusocial colonies appear simultaneously in the same population, and different populations of the same species may be fully solitary or eusocial. This suggests that eusociality is costly to maintain, and can only persist when ecological variables favor it. Disadvantages of eusociality include the cost of investing in non-reproductive offspring, and an increased risk of disease. All reversals to solitarity have occurred among primitively eusocial groups; none have followed the emergence of advanced eusociality. The "point of no return" hypothesis posits that the morphological differentiation of reproductive and non-reproductive castes prevents highly eusocial species such as the honeybee from reverting to the solitary state.Physiology and development

Pheromones

Pheromones play an important role in the physiological mechanisms of eusociality. Enzymes involved in the production and perception of pheromones were important for the emergence of eusociality within both termites and hymenopterans. The best-studied queen pheromone system in social insects is that of the honey bee ''Apis mellifera

The western honey bee or European honey bee (''Apis mellifera'') is the most common of the 7–12 species of honey bees worldwide. The genus name ''Apis'' is Latin for 'bee', and ''mellifera'' is the Latin for 'honey-bearing' or 'honey-carrying', ...

''. Queen mandibular glands produce a mixture of five compounds, three aliphatic

In organic chemistry, hydrocarbons ( compounds composed solely of carbon and hydrogen) are divided into two classes: aromatic compounds and aliphatic compounds (; G. ''aleiphar'', fat, oil). Aliphatic compounds can be saturated (in which all ...

and two aromatic

In organic chemistry, aromaticity is a chemical property describing the way in which a conjugated system, conjugated ring of unsaturated bonds, lone pairs, or empty orbitals exhibits a stabilization stronger than would be expected from conjugati ...

, which control workers. Mandibular gland extracts inhibit workers from constructing queen cells, which can delay the hormonally based behavioral development of workers and suppress their ovarian development. Both behavioral effects mediated by the nervous system often leading to recognition of queens ( releaser) and physiological effects on the reproductive and endocrine system ( primer) are attributed to the same pheromones. These pheromones volatilize or are deactivated within thirty minutes, allowing workers to respond rapidly to the loss of their queen.

The levels of two of the aliphatic compounds increase rapidly in virgin queens within the first week after emergence from the pupa, consistent with their roles as sex attractants during the mating flight. Once a queen is mated and begins laying eggs, she starts producing the full blend of compounds. In several ant species, reproductive activity is associated with pheromone production by queens. Mated egg-laying queens are attractive to workers, whereas young winged virgin queens elicit little or no response.

pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

from the queen's body alerts those workers of her dominance.

The mode of action of inhibitory pheromones which prevent the development of eggs in workers has been demonstrated in the bumble bee '' Bombus terrestris''. The pheromones suppress activity of the endocrine gland, the corpus allatum, stopping it from secreting juvenile hormone

Juvenile hormones (JHs) are a group of acyclic sesquiterpenoids that regulate many aspects of insect physiology. The first discovery of a JH was by Vincent Wigglesworth. JHs regulate development, reproduction, diapause, and polyphenisms.

In ...

. With low juvenile hormone, eggs do not mature. Similar inhibitory effects of lowering juvenile hormone were seen in halictine bees and polistine wasps, but not in honey bees.

Other mechanisms

A variety of other mechanisms give queens of different species of social insects a measure of reproductive control over their nest mates. In many ''Polistes

''Polistes'' is a cosmopolitan genus of paper wasps and the only genus in the tribe Polistini. Vernacular names for the genus include umbrella wasps, coined by Walter Ebeling in 1975 to distinguish it from other types of paper wasp, in refer ...

'' wasps, monogamy is established soon after colony formation by physical dominance interactions among foundresses of the colony including biting, chasing, and food soliciting. Such interactions create a dominance hierarchy headed by larger, older individuals with the greatest ovarian development. The rank of subordinates is correlated with the degree of ovarian development. Workers do not oviposit when queens are present, for a variety of reasons: colonies tend to be small enough that queens can effectively dominate workers; queens practice selective oophagy

Oophagy ( ) or ovophagy, literally "egg eating", is the practice of

embryos feeding on eggs produced by the ovary while still inside the mother's uterus. The word oophagy is formed from the classical Greek (, "egg") and classical Greek (, "to ...

; the flow of nutrients favors queen over workers; and queens rapidly lay eggs in new or vacated cells.

In primitively eusocial bees (where castes are morphologically similar and colonies are small and short-lived), queens frequently nudge their nest mates and then burrow back down into the nest. This draws workers into the lower part of the nest where they may respond to stimuli for cell construction and maintenance. Being nudged by the queen may help to inhibit ovarian development; in addition, the queen eats any eggs laid by workers. Furthermore, temporally discrete production of workers and gyne

The gyne (, from Greek γυνή, "woman") is the primary reproductive female caste of social insects (especially ants, wasps, and bees of order Hymenoptera, as well as termites). Gynes are those destined to become queens, whereas female workers ...

s (actual or potential queens) can cause size dimorphisms between different castes, as size is strongly influenced by the season during which the individual is reared. In many wasps, worker caste is determined by a temporal pattern in which workers precede non-workers of the same generation. In some cases, for example in bumblebees, queen control weakens late in the season, and the ovaries of workers develop. The queen attempts to maintain her dominance by aggressive behavior and by eating worker-laid eggs; her aggression is often directed towards the worker with the greatest ovarian development.

In highly eusocial wasps (where castes are morphologically dissimilar), both the quantity and quality of food are important for caste differentiation. Recent studies in wasps suggest that differential larval nourishment may be the environmental trigger for larval divergence into workers or gynes. All honey bee larvae are initially fed with royal jelly

Royal jelly is a honey bee secretion that is used in the nutrition of larvae and adult queens. It is secreted from the glands in the hypopharynx of nurse bees, and fed to all larvae in the colony, regardless of sex or caste.Graham, J. (ed.) (199 ...

, which is secreted by workers, but normally they are switched over to a diet of pollen and honey as they mature; if their diet is exclusively royal jelly, they grow larger than normal and differentiate into queens. This jelly contains a specific protein, royalactin, which increases body size, promotes ovary development, and shortens the developmental time period. The differential expression in ''Polistes'' of larval genes and proteins (also differentially expressed during queen versus caste development in honey bees) indicates that regulatory mechanisms may operate very early in development.

In popular culture

Stephen Baxter's 2003 science fiction novel ''Coalescent

''Coalescent'' is a science-fiction novel by Stephen Baxter. It is part one of the '' Destiny's Children'' series. The story is set in two main time periods: modern Britain, when George Poole finds that he has a previously unknown sister and ...

'' imagines a human eusocial organisation founded in ancient Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome is the Roman people, Roman civilisation from the founding of Rome, founding of the Italian city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, collapse of the Western Roman Em ...

, in which most individuals are subject to reproductive repression.

Harold Fromm, reviewing ''Groping for Groups'' by E. O. Wilson and others in '' The Hudson Review'', asks whether Wilson's stated "wish" for humans to bring about "a permanent paradise for human beings" would mean "to be group-selected in factories in the style of Huxley's 932 novel''Brave New World

''Brave New World'' is a dystopian novel by English author Aldous Huxley, written in 1931, and published in 1932. Largely set in a futuristic World State, whose citizens are environmentally engineered into an intelligence-based social hier ...

''.

The 1973 novel Hellstrom's Hive, ''Hellstrom’s Hive'' by Frank Herbert revolves around a secret society made up entirely of a race of bioengineered insect-like humanoids that is modeled after the behavior of social insect species.

See also

* Dense heterarchy * Evolutionarily stable strategy * International Union for the Study of Social Insects * Patterns of self-organization in ants * Reciprocity (social psychology) * Stigmergy ** Ant colony optimization (ACO) ** Bee colony optimization * Task allocation and partitioning of social insectsReferences

External links

International Union for the Study of Social Insects

{{Collective animal behaviour Behavioral ecology Superorganisms Sociobiology 1960s neologisms