Siglo de oro on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Spanish Golden Age (

The Spanish Golden Age (

During the

During the

The

The

The Plaza Mayor in Madrid, built during the

The Plaza Mayor in Madrid, built during the

Unlike most cathedrals in Spain, construction of this cathedral had to await the acquisition of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada from its Muslim rulers in 1492. While its very early plans had Gothic designs, such as are evident in the Royal Chapel of Granada by Enrique Egas, the construction of the church in the main occurred at a time when Renaissance designs were supplanting the Gothic regnant in Spanish architecture of prior centuries. Foundations for the church were laid by the architect Egas starting from 1518 to 1523 atop the site of the city's main mosque; by 1529, Egas was replaced by Diego de Siloé who labored for nearly four decades on the structure from ground to cornice, planning the

Unlike most cathedrals in Spain, construction of this cathedral had to await the acquisition of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada from its Muslim rulers in 1492. While its very early plans had Gothic designs, such as are evident in the Royal Chapel of Granada by Enrique Egas, the construction of the church in the main occurred at a time when Renaissance designs were supplanting the Gothic regnant in Spanish architecture of prior centuries. Foundations for the church were laid by the architect Egas starting from 1518 to 1523 atop the site of the city's main mosque; by 1529, Egas was replaced by Diego de Siloé who labored for nearly four decades on the structure from ground to cornice, planning the

The

The

''The "Spanish Century"''

Sor Juana, The Poet: The Sonnets

Digitized collection of Spanish Golden Theatre

a

Text search on (untranscribed) images of the BNE Digitized collection of Spanish Golden Theatre

Scholarly articles

about the Spanish Old Masters and the Spanish golden Age at

Spanish Old Masters Gallery

{{Authority control 1490s in Spain 16th century in Spain 17th century in Spain Baroque art Baroque music Baroque literature Renaissance art Renaissance music Renaissance literature Early modern history of Spain Golden ages (metaphor)

The Spanish Golden Age (

The Spanish Golden Age (Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

: ''Siglo de Oro'', , "Golden Century"; 1492 – 1681) was a period of literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

and the arts

The arts or creative arts are a vast range of human practices involving creativity, creative expression, storytelling, and cultural participation. The arts encompass diverse and plural modes of thought, deeds, and existence in an extensive ...

in Spain that coincided with the political rise of the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered ...

under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain

The Catholic Monarchs were Queen Isabella I of Castile () and King Ferdinand II of Aragon (), whose marriage and joint rule marked the '' de facto'' unification of Spain. They were both from the House of Trastámara and were second cousins, ...

, and the Spanish Habsburgs.

The Spanish Golden Age is broadly associated with the reigns of Isabella I

Isabella I (; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''Isabel la Católica''), was Queen of Castile and List of Leonese monarchs, León from 1474 until her death in 1504. She was also Queen of Aragon ...

, Ferdinand II, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

, Philip II, Philip III, and Philip IV, when Spain was at the peak of its power and influence in Europe and the world.

Overview

The Spanish Golden Age began after the union of KingFerdinand II of Aragon

Ferdinand II, also known as Ferdinand I, Ferdinand III, and Ferdinand V (10 March 1452 – 23 January 1516), called Ferdinand the Catholic, was King of Aragon from 1479 until his death in 1516. As the husband and co-ruler of Queen Isabella I of ...

and Queen Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I (; 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504), also called Isabella the Catholic (Spanish: ''Isabel la Católica''), was Queen of Castile and List of Leonese monarchs, León from 1474 until her death in 1504. She was also Queen of Aragon ...

, which brought stability following years of conflict. After the conquest of Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

(Muslim Spain

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

) and the expulsion of the Jews, the various Christian kingdoms under the Catholic Monarchs of Spain unified into a single state. This era saw a flourishing of literature and the arts in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. The most significant patron of Spanish art and culture during this time was King Philip II (1556–1598).

During this period, Philip II's royal palace, El Escorial

El Escorial, or the Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial (), or (), is a historical residence of the king of Spain located in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, up the valley ( road distance) from the town of El Escorial, Madrid, El ...

, known in its own time as the '' eighth wonder of the world'', attracted some of Europe's greatest architects and painters, including El Greco

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (, ; 1 October 1541 7 April 1614), most widely known as El Greco (; "The Greek"), was a Greek painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance, regarded as one of the greatest artists of all time. ...

. These artists introduced foreign styles to Spanish art, contributing to the development of a uniquely Spanish style of painting.

The start of the Golden Age can be placed in 1492, with the end of the ''Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

'', the voyages of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

to the New World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

, the expulsion of Jews from Spain

The Expulsion of Jews from Spain was the expulsion of practicing Jews following the Alhambra Decree in 1492, which was enacted to eliminate their influence on Spain's large ''converso'' population and to ensure its members did not revert to Judais ...

, and the publication of Antonio de Nebrija

Antonio de Nebrija (14445 July 1522) was the most influential Spanish humanist of his era. He wrote poetry, commented on literary works, and encouraged the study of classical languages and literature, but his most important contributions were i ...

's ''Grammar of the Castilian Language''. Amongst scholars of the period, it is generally accepted that it came to an end around the time of the Treaty of the Pyrenees

The Treaty of the Pyrenees(; ; ) was signed on 7 November 1659 and ended the Franco-Spanish War that had begun in 1635.

Negotiations were conducted and the treaty was signed on Pheasant Island, situated in the middle of the Bidasoa River on ...

(1659), that concluded the Franco-Spanish War of 1635 to 1659. Others, however, extend the Golden Age up to 1681 with the death of Pedro Calderón de la Barca

Pedro Calderón de la Barca y Barreda González de Henao Ruiz de Blasco y Riaño (17 January 160025 May 1681) (, ; ) was a Spanish dramatist, poet, and writer. He is known as one of the most distinguished Spanish Baroque literature, poets and ...

, the last great writer of the age. Generally, it is divided into a Plateresque

Plateresque, meaning "in the manner of a silversmith" (''plata'' being silver in Spanish language, Spanish), was an artistic movement, especially Architecture, architectural, developed in Spanish Empire, Spain and its territories, which appeared ...

/Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

period and the early part of the Spanish Baroque period.

The Spanish Golden Age spans the work of Miguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

, the author of '' Don Quixote de la Mancha;'' and of Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist who was a key figure in the Spanish Golden Age (1492–1659) of Spanish Baroque literature, Baroque literature. In the literature of ...

, Spain's most prolific playwright, who wrote around 1,000 plays during his lifetime, of which over 400 survive to the present day. Lope de Vega, Luis de Gongora, Quevedo, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, and many other prominent poets attended the famous Medrano Academy

The Medrano Academy (Spanish language, Spanish: ''Academia Medrano''), also known as the Poetic Academy of Madrid, was a prominent ''academia literaria'' of the Spanish Golden Age, founded by Dr. Sebastian Francisco de Medrano, Sebastián Francisc ...

(also known as the Poetic Academy of Madrid) established by Sebastián Francisco de Medrano in 1616.

Diego Velázquez

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (baptised 6 June 15996 August 1660) was a Spanish painter, the leading artist in the Noble court, court of King Philip IV of Spain, Philip IV of Spain and Portugal, and of the Spanish Golden Age. He i ...

, regarded as one of the most influential painters of European history and a greatly respected artist in his own time, was patronized by King Philip IV and his chief minister, the Count-Duke of Olivares.

What is widely acknowledged as some of Spain's greatest music was written during this period. Composers such as Tomás Luis de Victoria

Tomás Luis de Victoria (sometimes Italianised as ''da Vittoria''; ) was the most famous Spanish composer of the Renaissance. He stands with Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Orlande de Lassus as among the principal composers of the late Re ...

, Cristóbal de Morales, Francisco Guerrero, Luis de Milán and Alonso Lobo helped to shape Renaissance music

Renaissance music is traditionally understood to cover European music of the 15th and 16th centuries, later than the Renaissance era as it is understood in other disciplines. Rather than starting from the early 14th-century ''ars nova'', the mus ...

and the styles of counterpoint

In music theory, counterpoint is the relationship of two or more simultaneous musical lines (also called voices) that are harmonically dependent on each other, yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. The term originates from the Latin ...

and polychoral

An antiphon (Greek ἀντίφωνον, ἀντί "opposite" and φωνή "voice") is a short chant in Christian ritual, sung as a refrain. The texts of antiphons are usually taken from the Psalms or Scripture, but may also be freely composed. T ...

music. Their influence lasted long into the Baroque period, resulting in a revolution of music.

Painting

During the

During the Italian Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

, few great artists from Italy visited Spain, but the Italian holdings and relationships established by Ferdinand of Aragon, Queen Isabella's husband and, later, Spain's sole monarch, prompted a steady flow of intellectuals across the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

between Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

, Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, and Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

. Luis de Morales, one of the leading exponents of Spanish Mannerist

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

painting, retained a distinctly Spanish style in his work, reminiscent of medieval art

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, with over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional ar ...

. Spanish art, particularly Morales's, was notable for its mysticism and religious themes, which were encouraged by the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also sometimes called the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to, and as an alternative to or from similar insights as, the Protestant Reformations at the time. It w ...

and by the patronage of Spain's Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

monarchs and aristocracy. Spanish rule of Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

was important for making connections between Italian and Spanish art, with many Spanish administrators bringing Italian works back to Spain.

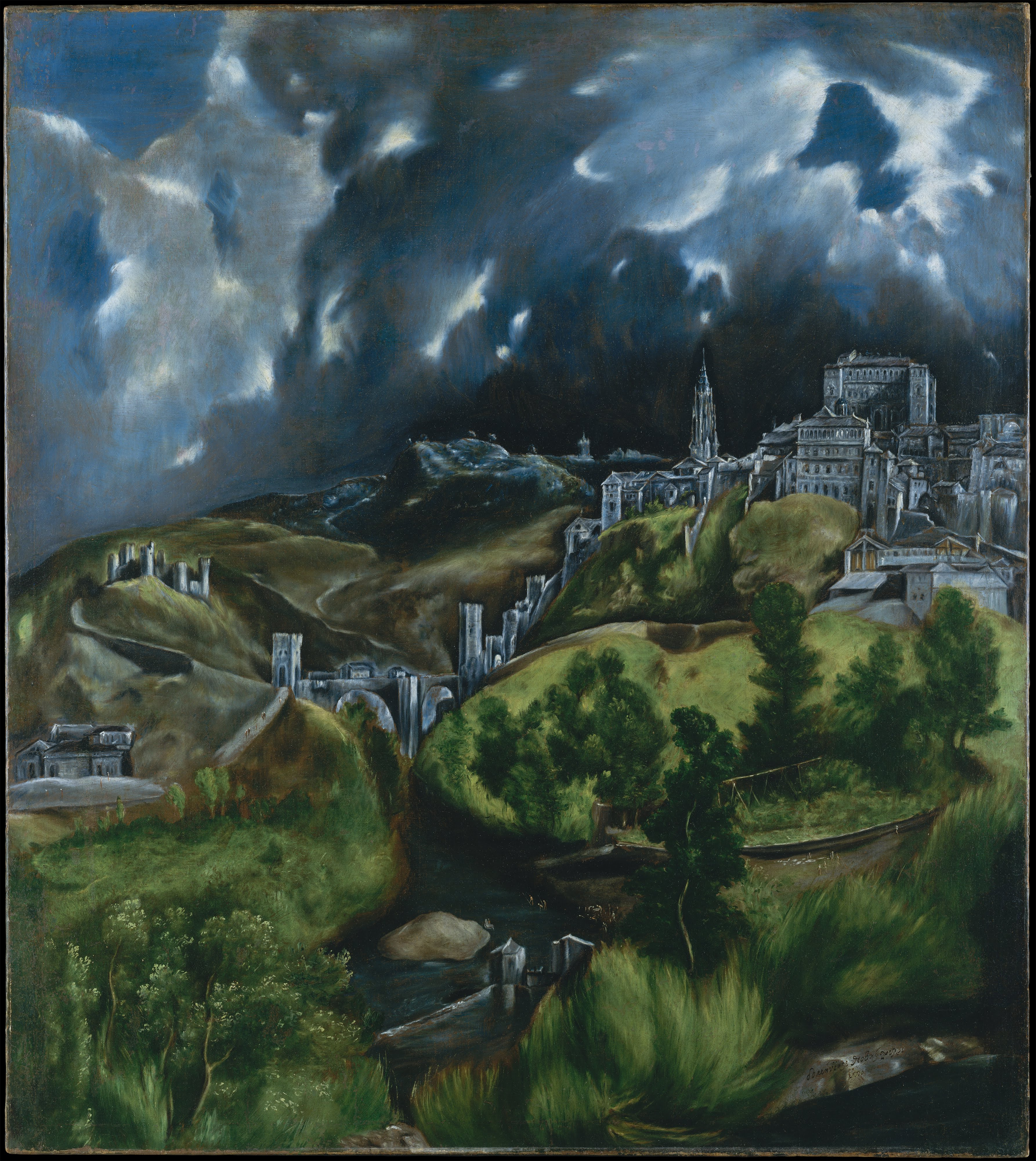

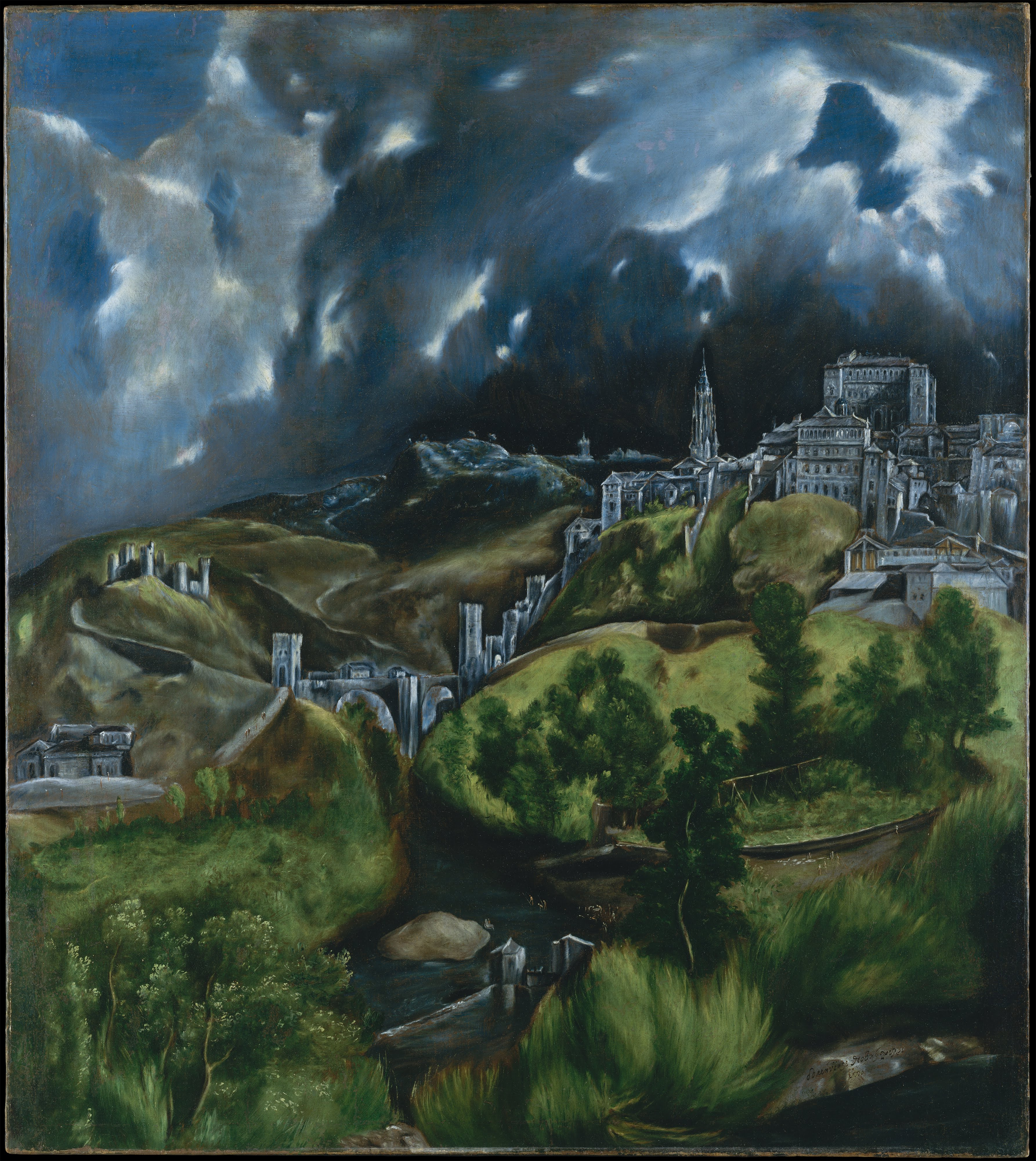

El Greco

Known for his unique expressionistic style, which elicited both puzzlement and admiration,El Greco

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (, ; 1 October 1541 7 April 1614), most widely known as El Greco (; "The Greek"), was a Greek painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance, regarded as one of the greatest artists of all time. ...

("the Greek") was originally from the island of Crete. He was not Spanish but Greek by birth. El Greco studied the great Italian masters of his time—Titian

Tiziano Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.

Ti ...

, Tintoretto

Jacopo Robusti (late September or early October 1518Bernari and de Vecchi 1970, p. 83.31 May 1594), best known as Tintoretto ( ; , ), was an Italian Renaissance painter of the Venetian school. His contemporaries both admired and criticized th ...

, and Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

—during his stay in Italy from 1568 to 1577. According to legend, El Greco once claimed he would paint a mural as good as one of Michelangelo's if one of the Italian artist's murals was demolished first. After falling out of favor in Italy, he found a new home in Toledo, central Spain. During this period, Spain was an ideal environment for the Venetian-trained painter, with art flourishing throughout the empire and Toledo being a great place to receive commissions. His paintings of the city became models for a new European tradition in landscapes and influenced the work of later Dutch masters. In his lifetime, El Greco was influential in creating a style based on impressions and emotion, characterized by elongated fingers and vibrant color and brushwork. His works uniquely featured faces that captured expressions of somber attitudes and withdrawal while still having his subjects bear witness to the terrestrial world.

Diego Velázquez

Diego Velázquez

Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez (baptised 6 June 15996 August 1660) was a Spanish painter, the leading artist in the Noble court, court of King Philip IV of Spain, Philip IV of Spain and Portugal, and of the Spanish Golden Age. He i ...

was born on June 6, 1599, in Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, to parents of minor nobility and was the eldest of six children. Widely regarded as one of Spain's most important and influential artists, he became a court painter for King Philip IV and gained increasing demand across Europe for his portraits of statesmen, aristocrats, and clergymen. His portraits of the King, his chief minister the Count-Duke of Olivares, and the Pope showcased his belief in artistic realism and a style comparable to many of the Dutch masters. Following the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

, Velázquez met the Marqués de Spinola and painted his famous Surrender of Breda (1635), celebrating Spinola's victory at Breda in 1625. Spinola was impressed by Velázquez's ability to convey emotion through realism in both his portraits and landscapes, the latter of which became a lasting influence on Western painting. Velázquez's friendship with Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo ( , ; late December 1617, baptized January 1, 1618April 3, 1682) was a Spanish Baroque painter. Although he is best known for his religious works, Murillo also produced a considerable number of paintings of contempor ...

, a leading Spanish painter of the next generation, ensured the enduring influence of his artistic approach.

Velázquez's most famous painting is the celebrated (1656, Prado Museum in Madrid) in which the artist includes himself as one of the subjects.

Francisco de Zurbarán

The religious element in Spanish art gained prominence in many circles during the Counter-Reformation. The austere, ascetic, and severe works of Francisco de Zurbarán exemplified this trend in Spanish art, alongside the compositions ofTomás Luis de Victoria

Tomás Luis de Victoria (sometimes Italianised as ''da Vittoria''; ) was the most famous Spanish composer of the Renaissance. He stands with Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Orlande de Lassus as among the principal composers of the late Re ...

. Philip IV actively patronized artists whose views aligned with his perspectives on the Counter-Reformation and religion. The mysticism in Zurbarán's work, influenced by Saint Theresa of Avila, became a defining characteristic of Spanish art in subsequent generations. Influenced by Michelangelo da Caravaggio and the Italian masters, Zurbarán dedicated himself to an artistic expression of religion and faith. His paintings of St. Francis of Assisi, the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the doctrine that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception. It is one of the four Mariology, Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Debated by medieval theologians, it was not def ...

, and the Crucifixion

Crucifixion is a method of capital punishment in which the condemned is tied or nailed to a large wooden cross, beam or stake and left to hang until eventual death. It was used as a punishment by the Achaemenid Empire, Persians, Ancient Carthag ...

of Christ

Jesus ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Christianity, central figure of Christianity, the M ...

reflected a significant aspect of seventeenth-century Spanish culture, set against the backdrop of religious conflict across Europe. Zurbarán diverged from Velázquez's sharp realist interpretation of art and, to some extent, drew inspiration from the emotive content of El Greco

Doménikos Theotokópoulos (, ; 1 October 1541 7 April 1614), most widely known as El Greco (; "The Greek"), was a Greek painter, sculptor and architect of the Spanish Renaissance, regarded as one of the greatest artists of all time. ...

and earlier Mannerist painters. Nevertheless, Zurbarán respected and maintained the lighting and physical nuance characteristic of Velázquez's style.

It is unknown whether Zurbarán had the opportunity to study Caravaggio's paintings; nonetheless, he adopted Caravaggio's realistic use of chiaroscuro

In art, chiaroscuro ( , ; ) is the use of strong contrasts between light and dark, usually bold contrasts affecting a whole composition. It is also a technical term used by artists and art historians for the use of contrasts of light to ach ...

. The painter who may have had the greatest influence on his characteristically severe compositions was Juan Sánchez Cotán. Additionally, polychrome sculpture—which had reached a high level of sophistication in Seville by the time of Zurbarán's apprenticeship and surpassed that of the local painters—served as another important stylistic model for the young artist. The work of Juan Martínez Montañés

Juan Martínez Montañés (March 16, 1568 – June 18, 1649), known as el Dios de la Madera (''the God of Wood''), was a Spanish sculpture, sculptor, born at Alcalá la Real, in the Jaén (Spanish province), province of Jaén. He was one of th ...

is particularly close to Zurbarán's in spirit.

Zurbarán painted directly from nature and frequently utilized the lay figure in his study of draperies, in which he was particularly skilled. He had a notable talent for depicting white draperies, leading to numerous representations of the white-robed Carthusians

The Carthusians, also known as the Order of Carthusians (), are a Latin enclosed religious order of the Catholic Church. The order was founded by Bruno of Cologne in 1084 and includes both monks and nuns. The order has its own rule, called the ...

in his works. Zurbarán is said to have adhered to these meticulous methods throughout his career, which was successful and spent entirely in Spain. His subjects were predominantly austere and ascetic religious scenes, often depicting the spirit subduing the flesh. These compositions were frequently simplified to a single figure. His style is more reserved and subdued than Caravaggio's, with a color tone that is often bluish. Exceptional effects are achieved through precisely finished foregrounds, primarily utilizing light and shade.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo ( , ; late December 1617, baptized January 1, 1618April 3, 1682) was a Spanish Baroque painter. Although he is best known for his religious works, Murillo also produced a considerable number of paintings of contempor ...

began his art studies under Juan del Castillo in Seville. The city's great commercial importance at the time ensured that he was also subject to influences from other regions, which enabled him to become familiar with Flemish painting

Flemish painting flourished from the early 15th century until the 17th century, gradually becoming distinct from the painting of the rest of the Low Countries, especially the modern Netherlands. In the early period, up to about 1520, the painti ...

. His first works were influenced by Zurbarán, Jusepe de Ribera

Jusepe de Ribera (; baptised 17 February 1591 – 3 November 1652) was a Spanish painter and Printmaking, printmaker. Ribera, Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and the singular Diego Velázquez, are regarded as the major artist ...

and Alonso Cano, with whom he shared a strongly realist approach. As his painting developed, however, his more important works evolved into a polished style that suited the bourgeois and aristocratic tastes of the time, especially his Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

religious works.

In 1642, at the age of 26, he moved to Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

. While there, it is highly likely that he became familiar with the work of Velázquez and that he viewed the work of Venetian and Flemish masters in the royal collections; the influence of both can be seen in the rich colors and softly modeled forms of his later work. Murillo returned to Seville in 1645, where in the same year he painted 13 canvases for the monastery of St. Francisco el Grande. This proved a boost to his reputation. Following the completion of a pair of pictures for the Seville Cathedral

The Cathedral of Saint Mary of the See (), better known as Seville Cathedral (), is a Catholic cathedral and former mosque in Seville, Andalusia, Spain. It was registered in 1987 by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with the adjoining Alc� ...

, he began to specialize in the themes that brought him his greatest successes: Mary and the Child Jesus, and the Immaculate Conception

The Immaculate Conception is the doctrine that the Virgin Mary was free of original sin from the moment of her conception. It is one of the four Mariology, Marian dogmas of the Catholic Church. Debated by medieval theologians, it was not def ...

.

After another period in Madrid from 1658 to 1660, he returned to Seville. There, he was one of the founders of the Academia de Bellas Artes (Academy of Fine Arts), sharing its direction in 1660 with the architect Francisco Herrera the Younger. This was his period of greatest activity, during which he received numerous important commissions, among them the altarpieces for the Augustinian monastery and the paintings for Santa María la Blanca (completed in 1665). He died in 1682.

Other significant painters

* Luis de Morales *José de Ribera

Jusepe de Ribera (; baptised 17 February 1591 – 3 November 1652) was a Spanish painter and printmaker. Ribera, Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and the singular Diego Velázquez, are regarded as the major artists of Spani ...

* Juan Sánchez Cotán

* Juan van der Hamen

Juan van der Hamen y (Gómez de) León (baptized 8 April 1596 – 28 March 1631) was a Spanish painter, a master of still life paintings, also called bodegón, bodegones. Prolific and versatile, he painted allegories, landscapes, and large-scal ...

* Francisco Ribalta

* Juan de Valdés Leal

* Juan Carreño de Miranda

* Claudio Coello

Sculpture

Sculptors of the Renaissance

*Alonso Berruguete

Alonso González de Berruguete ( – 1561) was a Spanish Painting, painter, Sculpture, sculptor and architect. He is considered to be the most important sculptor of the Spanish Renaissance, and is known for his emotive sculptures depicting re ...

* Felipe Bigarny

* Damià Forment

* Juan de Juni

* Bartolomé Ordóñez

* Diego de Siloé

Sculptors of the Early Baroque period

* Alonso Cano * Gregorio Fernández *Juan Martínez Montañés

Juan Martínez Montañés (March 16, 1568 – June 18, 1649), known as el Dios de la Madera (''the God of Wood''), was a Spanish sculpture, sculptor, born at Alcalá la Real, in the Jaén (Spanish province), province of Jaén. He was one of th ...

* Pedro de Mena

* Juan de Mesa

Architecture

Palace of Charles V

The

The Palace of Charles V

The Palace of Charles V is a Renaissance building in Granada, southern Spain, inside the Alhambra, a former Nasrid palace complex on top of the Sabika hill. Construction began in 1527 but dragged on and was left unfinished after 1637. The palace ...

is a Renaissance construction located on the top of the hill of the Assabica, inside the Nasrid fortification of the Alhambra

The Alhambra (, ; ) is a palace and fortress complex located in Granada, Spain. It is one of the most famous monuments of Islamic architecture and one of the best-preserved palaces of the historic Muslim world, Islamic world. Additionally, the ...

. It was commanded by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (as Charles I) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy (as Charles II) ...

, who wished to establish his residence close to the Alhambra palaces. Although the Catholic Monarchs

The Catholic Monarchs were Isabella I of Castile, Queen Isabella I of Crown of Castile, Castile () and Ferdinand II of Aragon, King Ferdinand II of Crown of Aragón, Aragon (), whose marriage and joint rule marked the ''de facto'' unification of ...

had already altered some rooms of the Alhambra after the conquest of the city in 1492, Charles V intended to construct a permanent residence befitting an emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

. The project was given to Pedro Machuca, an architect whose biography and influences are poorly understood. Even if accounts that place Machuca in the atelier

An atelier () is the private workshop or studio of a professional artist in the fine or decorative arts or an architect, where a principal master and a number of assistants, students, and apprentices can work together producing fine art or vi ...

of Michelangelo are accepted, at the time of the construction of the palace in 1527 the latter had yet to design the majority of his architectural works. At the time, Spanish architecture was immersed in the Plateresque

Plateresque, meaning "in the manner of a silversmith" (''plata'' being silver in Spanish language, Spanish), was an artistic movement, especially Architecture, architectural, developed in Spanish Empire, Spain and its territories, which appeared ...

style, still with traces of Gothic origin. Machuca built a palace corresponding stylistically to Mannerism

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

, a mode still in its infancy in Italy.

El Escorial

El Escorial

El Escorial, or the Royal Site of San Lorenzo de El Escorial (), or (), is a historical residence of the king of Spain located in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, up the valley ( road distance) from the town of El Escorial, Madrid, El ...

is the historical residence of the king of Spain. It is one of the Spanish royal sites and functions as a monastery, royal palace, museum, and school. It is located about northwest of the Spanish capital, Madrid, in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial

San Lorenzo de El Escorial, also known as El Escorial de Arriba, is a town and municipality in the Community of Madrid, Spain, located to the northwest of the region in the southeastern side of the Sierra de Guadarrama, at the foot of Moun ...

. El Escorial comprises two architectural complexes of great historical and cultural significance: El Real Monasterio de El Escorial itself and La Granjilla de La Fresneda, a royal hunting lodge and monastic retreat about five kilometers away. These sites have a dual nature; that is to say, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, they were places in which the temporal power of the Spanish monarchy

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish monarchy is constitu ...

''and'' the ecclesiastical predominance of the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

religion in Spain found a common architectural manifestation. El Escorial was at once, a monastery and a Spanish royal palace. Originally a property of the Hieronymite monks, it is now a monastery of the Order of Saint Augustine

The Order of Saint Augustine (), abbreviated OSA, is a mendicant order, mendicant catholic religious order, religious order of the Catholic Church. It was founded in 1244 by bringing together several eremitical groups in the Tuscany region who ...

.

Philip II of Spain, reacting to the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

sweeping through Europe during the sixteenth century, devoted much of his lengthy reign (1556–1598) and much of his seemingly inexhaustible supply of New World silver to stemming the Protestant tide sweeping through Europe while simultaneously fighting the Islamic Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. His protracted efforts were, in the long run, partly successful. However, the same counter-reformational impulse had a much more benign expression thirty years earlier, in Philip's decision to build the complex at El Escorial.

Philip engaged the Spanish architect, Juan Bautista de Toledo, to be his collaborator in the design of El Escorial. Juan Bautista had spent the greater part of his career in Rome, where he had worked on the basilica of St. Peter's, and in Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, where he had served the king's viceroy, whose recommendation brought him to the king's attention. Philip appointed him architect-royal in 1559, and together they designed El Escorial as a monument to Spain's role as a center of the Christian world.

Plaza Mayor in Madrid

Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

period, is a central plaza

A town square (or public square, urban square, city square or simply square), also called a plaza or piazza, is an open public space commonly found in the heart of a traditional town or city, and which is used for community gatherings. Rela ...

in the city of Madrid, Spain. It is located only a few blocks away from another famous plaza, the Puerta del Sol. The Plaza Mayor is rectangular in shape, measuring 129 by 94 meters, and is surrounded by three-story residential buildings having 237 balconies facing the Plaza. It has a total of nine entranceways. The Casa de la Panadería, serving municipal and cultural functions, dominates the Plaza Mayor.

The origins of the Plaza date back to 1589 when Philip II of Spain asked Juan de Herrera, a renowned Renaissance architect, to discuss a plan to remodel the busy and chaotic area of the old Plaza del Arrabal. Juan de Herrera was the architect who designed the first project in 1581 to remodel the old Plaza del Arrabal but construction did not start until 1617, during Philip III's reign. The king asked Juan Gómez de Mora to continue with the project, and he finished the porticoes in 1619. Nevertheless, the Plaza Mayor as we know it today is the work of the architect Juan de Villanueva who was entrusted with its reconstruction in 1790 after a spate of big fires. Giambologna's equestrian statue of Philip III dates to 1616, but it was not placed in the center of the square until 1848.

Granada Cathedral

Unlike most cathedrals in Spain, construction of this cathedral had to await the acquisition of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada from its Muslim rulers in 1492. While its very early plans had Gothic designs, such as are evident in the Royal Chapel of Granada by Enrique Egas, the construction of the church in the main occurred at a time when Renaissance designs were supplanting the Gothic regnant in Spanish architecture of prior centuries. Foundations for the church were laid by the architect Egas starting from 1518 to 1523 atop the site of the city's main mosque; by 1529, Egas was replaced by Diego de Siloé who labored for nearly four decades on the structure from ground to cornice, planning the

Unlike most cathedrals in Spain, construction of this cathedral had to await the acquisition of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada from its Muslim rulers in 1492. While its very early plans had Gothic designs, such as are evident in the Royal Chapel of Granada by Enrique Egas, the construction of the church in the main occurred at a time when Renaissance designs were supplanting the Gothic regnant in Spanish architecture of prior centuries. Foundations for the church were laid by the architect Egas starting from 1518 to 1523 atop the site of the city's main mosque; by 1529, Egas was replaced by Diego de Siloé who labored for nearly four decades on the structure from ground to cornice, planning the triforium

A triforium is an interior Gallery (theatre), gallery, opening onto the tall central space of a building at an upper level. In a church, it opens onto the nave from above the side aisles; it may occur at the level of the clerestory windows, o ...

and five naves instead of the usual three. Most unusually, he created a circular capilla mayor rather than a semicircular apse, perhaps inspired by Italian ideas for circular 'perfect buildings' (e.g., in Alberti's works). Within its structure the cathedral combines other orders of architecture. It took 181 years for the cathedral to be built.

Subsequent architects included Juan de Maena (1563–1571), followed by Juan de Orea (1571–1590), and Ambrosio de Vico (1590–?). In 1667, Alonso Cano, working with Gaspar de la Peña, altered the initial plan for the main façade, introducing Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

elements. The magnificence of the building would be even greater if the two large 81-meter towers foreseen in the plans had been built; however, the project remained incomplete for various reasons, including finance.

Granada Cathedral had been intended to become the royal mausoleum for Charles I of Spain, but Philip II of Spain moved the site for his father and subsequent kings to El Escorial outside of Madrid.

The main chapel contains two kneeling effigies of the Catholic King and Queen, Ferdinand and Isabel, by Pedro de Mena y Medrano. The busts of Adam and Eve were made by Alonso Cano. The Chapel of the Trinity has a marvelous retablo with paintings by El Greco, Alonso Cano, and José de Ribera

Jusepe de Ribera (; baptised 17 February 1591 – 3 November 1652) was a Spanish painter and printmaker. Ribera, Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, and the singular Diego Velázquez, are regarded as the major artists of Spani ...

(The ''Spagnoletto'').

Cathedral of Valladolid

The

The Cathedral of Valladolid

The Cathedral of Our Lady of the Holy Assumption (), better known as Valladolid Cathedral, is a Catholic Church architecture, church in Valladolid, Spain. The main layout was designed by Juan de Herrera in a Renaissance architecture, Renaissance- ...

, like all the buildings of the late Spanish Renaissance

The Spanish Renaissance was a movement in Spain, emerging from the Italian Renaissance in Italy during the 14th century, that spread to Spain during the 15th and 16th centuries.

This new focus in art, literature,

Quotation, quotes and scienc ...

built by Herrera and his followers, is known for its purist and sober decoration, with its style being typical Spanish ''clasicismo'', also called "Herrerian

The Herrerian style ( or ''arquitectura herreriana'') of architecture was developed in Spain during the last third of the 16th century under the reign of Philip II of Spain, Philip II (1556–1598), and continued in force in the 17th century ...

". Using classical and Renaissance decorative motifs, Herrerian buildings are characterized by their extremely sober decorations, their formal austerity, and its like for monumentality.

The cathedral has its origins in a late Gothic college that started in the late 15th century. Before becoming the capital of Spain, Valladolid was not a bishopric and thus lacked the right to build a cathedral. Soon enough, though, the Collegiate became obsolete due to the changes of preference during the period, and thanks to the newly established episcopal in the city, the Town Council decided to build a cathedral that would share similar architecture to neighboring capitals.

Had the building been finished, it would have been one of the biggest cathedrals in Spain. When the building was started, Valladolid was the ''de facto'' capital of Spain, housing King Philip II and his court. However, due to strategic and geopolitical reasons, by the 1560s, the capital was moved to Madrid, making Valladolid lose its political and economic relevance. By the late sixteenth century, Valladolid's importance had been severely reduced, and many of the monumental projects, such as the cathedral, started during its prosperous years, had to be modified due to a lack of proper finance. Thus, the building that stands now could not be finished completely, and due to several additions built during the 17th and 18th centuries, it lacks the purported stylistical uniformity sought by Herrera. Although mainly faithful to the project of Juan de Herrera, the building would undergo many modifications.

Significant architects

Renaissance and Plateresque period

* Alonso de Covarrubias * Juan de Herrera * Rodrigo Gil de Hontañón * Pedro Machuca * Francisco de Mora * Diego de Riaño * Hernán Ruiz the Younger * Diego de Siloé * Juan Bautista de Toledo * Andrés de VandelviraEarly Baroque period

* Domingo Antonio de Andrade * Eufrasio López de Rojas * Juan Gómez de MoraMusic

Tomás Luis de Victoria

Tomás Luis de Victoria

Tomás Luis de Victoria (sometimes Italianised as ''da Vittoria''; ) was the most famous Spanish composer of the Renaissance. He stands with Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina and Orlande de Lassus as among the principal composers of the late Re ...

, a Spanish composer of the sixteenth century, mainly of choral music, is widely regarded as one of the greatest Spanish classical composers. He joined the cause of Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola ( ; ; ; ; born Íñigo López de Oñaz y Loyola; – 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Basque Spaniard Catholic priest and theologian, who, with six companions, founded the religious order of the S ...

in the fight against the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

and, in 1575, became a priest. He lived for a short time in Italy, where he became acquainted with the polyphonic work of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (between 3 February 1525 and 2 February 1526 – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer of late Renaissance music. The central representative of the Roman School, with Orlande de Lassus and Tomás Luis de V ...

. Like Zurbarán, Victoria mixed the technical qualities of Italian art with the religion and culture of his native Spain. He invigorated his work with emotional appeal, experimental mystical rhythm, and choruses. He broke from the dominant tendency among his contemporaries by avoiding complex counterpoint, preferring longer, simpler, less technical, and more mysterious melodies, and employing dissonance in ways that the Italian members of the Roman School

In music history, the Roman School was a group of composers of predominantly church music, in Rome, during the 16th and 17th centuries, therefore spanning the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras. The term also refers to the music they prod ...

shunned. He demonstrated considerable invention in musical thought by connecting the tone and emotion of his music to those of his lyrics, particularly in his motet

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the preeminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to the Eng ...

s. Like Velázquez, Victoria was employed by the monarch – in Victoria's case, in the service of the queen. The Officium Defunctorum (Requiem) he wrote upon her death in 1603 is regarded as one of his most enduring and complex works.

Francisco Guerrero

Francisco Guerrero, a Spanish composer of the 16th century. He was second only to Victoria as a major Spanish composer of church music in the second half of the 16th century. Of all theSpanish Renaissance

The Spanish Renaissance was a movement in Spain, emerging from the Italian Renaissance in Italy during the 14th century, that spread to Spain during the 15th and 16th centuries.

This new focus in art, literature,

Quotation, quotes and scienc ...

composers, he was the one who mostly lived and worked in Spain. Others, e.g., Morales and Victoria, spent large portions of their careers in Italy. Guerrero's music was both religious and secular, unlike that of Victoria and Morales, the two other Spanish 16th-century composers of the first rank. He wrote numerous secular songs and instrumental pieces, in addition to masses, motets, and passions. He was able to capture an astonishing variety of moods in his music, from elation to despair, longing, depression, and devotion. His music remained popular for hundreds of years, especially in cathedrals in Latin America. Stylistically, he preferred homophonic

Homophony and Homophonic are from the Greek language, Greek ὁμόφωνος (''homóphōnos''), literally 'same sounding,' from ὁμός (''homós''), "same" and φωνή (''phōnē''), "sound". It may refer to:

*Homophones − words with the s ...

textures rather than Spanish contemporaries. One feature of his style is how he anticipated functional harmonic usage: there is a case of a Magnificat

The Magnificat (Latin for "y soulmagnifies he Lord) is a canticle, also known as the Song of Mary or Canticle of Mary, and in the Byzantine Rite as the Ode of the Theotokos (). Its Western name derives from the incipit of its Latin text. This ...

discovered in Lima, Peru, once thought to be an anonymous 18th century work, which turned out to be his work.

Alonso Lobo

Victoria's work was complemented by Alonso Lobo – a man Victoria respected as his equal. Lobo's work—also choral and religious in its content – stressed the austere, minimalist nature of religious music. Lobo sought out a medium between the emotional intensity of Victoria and the technical ability ofPalestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; , ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon ...

; the solution he found became the foundation of the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

musical style in Spain.

Cristóbal de Morales

Regarded as one of the finest composers in Europe around the middle of the 16th century, Cristóbal de Morales was born inSeville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

in 1500 and employed in Rome from 1535 until 1545 by the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

. Almost all of his music is religious, and all of it is vocal, though instruments may have been used in an accompanying role in performance. Morales also wrote two masses on the famous ''L'homme armé

"L'homme armé" () is a secular song from the Late Middle Ages, of the Burgundian School. According to Allan W. Atlas, "the tune circulated in both the Mixolydian mode and Dorian mode (transposed to G)." It was the most popular tune used for mus ...

'' melody, which was often set by composers in the late 15th and 16th centuries. One of these masses is for four voices, and the other for five. The four voice mass uses the tune as a strict cantus firmus, and the setting for five voices treats it more freely, migrating it from one voice to another.

Other significant musicians

* Antonio de Cabezón * Francisco Correa de Arauxo * Juan Cabanilles * Juan del Encina * Luis Milán * Luis de Narváez * Enríquez de Valderrábano * Diego Pisador * Alonso Mudarra * Pablo BrunaLiterature

The Spanish Golden Age was a period of remarkable growth inpoetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

, prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

, and drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

, driven by Spain's deep engagement with European literary

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, plays, and poems. It includes both print and digital writing. In recent centuries, ...

and philosophical

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

currents, particularly its strong connections to Renaissance Italy

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in History of Italy, Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Western Europe and marked t ...

. A Spanish college in Bologna

Bologna ( , , ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Emilia-Romagna region in northern Italy. It is the List of cities in Italy, seventh most populous city in Italy, with about 400,000 inhabitants and 150 different nationalities. Its M ...

(1360s) enabled scholars like Antonio de Nebrija

Antonio de Nebrija (14445 July 1522) was the most influential Spanish humanist of his era. He wrote poetry, commented on literary works, and encouraged the study of classical languages and literature, but his most important contributions were i ...

to study abroad, while Alfonso V of Aragon

Alfonso the Magnanimous (Alfons el Magnànim in Catalan language, Catalan) (139627 June 1458) was King of Aragon and King of Sicily (as Alfons V) and the ruler of the Crown of Aragon from 1416 and King of Naples (as Alfons I) from 1442 until his ...

transformed Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

into a cultural hub (1442). Spanish intellectuals traveled to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, absorbing influences from Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

, Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio ( , ; ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was s ...

, and Sannazaro, while Italian scholars were welcomed in Spain. This exchange also revived interest in classical literature

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek and Roman literature and their original languages, ...

(Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; 15 October 70 BC21 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Rome, ancient Roman poet of the Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Augustan period. He composed three of the most fa ...

, Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). Th ...

, Ovid

Publius Ovidius Naso (; 20 March 43 BC – AD 17/18), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Augustan literature (ancient Rome), Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a younger contemporary of Virgil and Horace, with whom he i ...

) and Neoplatonism

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

, enriching Spanish language and thought. Francisco de Medrano, a lyric poet

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

The term for both modern lyric poetry and modern song lyrics derives from a form of Ancient Greek literature, t ...

from Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

, is considered one of the best of the Spanish imitators of Horace, comparing favorably in that respect with Luis de León.

Cervantes and ''Don Quixote''

Regarded by many as one of the finest works in any language, '' El ingenioso hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha'' byMiguel de Cervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 Old Style and New Style dates, NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelist ...

was the first novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

published in Europe; it gave Cervantes a stature in the Spanish-speaking world comparable to his contemporary William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

in English. The novel, like Spain itself, was caught between the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and the modern world. A veteran of the Battle of Lepanto (1571)

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of the Ottoman Empire in the Gulf o ...

, Cervantes had fallen on hard times in the late 1590s and was imprisoned for debt in 1597, and some believe that during these years he began work on his best-remembered novel. The first part of the novel was published in 1605; the second in 1615, a year before the author's death. ''Don Quixote'' resembled both the medieval, chivalric romances of an earlier time and the novels of the early modern world. It parodied classical morality and chivalry, found comedy in knighthood, and criticized social structures and the perceived madness of Spain's rigid society. The work has endured to the present day as a landmark in world literary history, and it was an international hit in its own time, interpreted variously as a satirical comedy, social commentary and forebear of self-referential literature.

Lope de Vega and ''comedia''

A contemporary ofCervantes

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra ( ; ; 29 September 1547 (assumed) – 22 April 1616 NS) was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his no ...

, Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist who was a key figure in the Spanish Golden Age (1492–1659) of Spanish Baroque literature, Baroque literature. In the literature of ...

played a key role in shaping Spanish commercial drama, known as '' comedia'', by defining its essential genres and structures throughout the 17th century. All ''comedia'' was reviewed by Dr. Sebastián Francisco de Medrano, a commissioner

A commissioner (commonly abbreviated as Comm'r) is, in principle, a member of a commission or an individual who has been given a commission (official charge or authority to do something).

In practice, the title of commissioner has evolved to incl ...

of the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition () was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile and lasted until 1834. It began toward the end of ...

, who served as its official

An official is someone who holds an office (function or Mandate (politics), mandate, regardless of whether it carries an actual Office, working space with it) in an organization or government and participates in the exercise of authority (eithe ...

censor.

Although he also wrote prose

Prose is language that follows the natural flow or rhythm of speech, ordinary grammatical structures, or, in writing, typical conventions and formatting. Thus, prose ranges from informal speaking to formal academic writing. Prose differs most n ...

and poetry

Poetry (from the Greek language, Greek word ''poiesis'', "making") is a form of literature, literary art that uses aesthetics, aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meaning (linguistics), meanings in addition to, or in ...

, Lope de Vega is best remembered for his plays, particularly those rooted in Spanish history. Like Cervantes, he served in the Spanish army

The Spanish Army () is the terrestrial army of the Spanish Armed Forces responsible for land-based military operations. It is one of the oldest Standing army, active armies – dating back to the late 15th century.

The Spanish Army has existed ...

and was deeply interested in the nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

. Lope de Vega's vast body of work—ranging from Biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

and classical mythology

Classical mythology, also known as Greco-Roman mythology or Greek and Roman mythology, is the collective body and study of myths from the ancient Greeks and ancient Romans. Mythology, along with philosophy and political thought, is one of the m ...

to legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

ary and contemporary Spanish history—often incorporated humor

Humour ( Commonwealth English) or humor (American English) is the tendency of experiences to provoke laughter and provide amusement. The term derives from the humoral medicine of the ancient Greeks, which taught that the balance of fluids i ...

, much like Cervantes. He frequently transformed conventional moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

plays by infusing them with wit, cynicism, and comedic elements, aiming primarily to entertain the public. His ability to blend morality

Morality () is the categorization of intentions, Decision-making, decisions and Social actions, actions into those that are ''proper'', or ''right'', and those that are ''improper'', or ''wrong''. Morality can be a body of standards or principle ...

, comedy

Comedy is a genre of dramatic works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium.

Origins

Comedy originated in ancient Greec ...

, drama

Drama is the specific Mode (literature), mode of fiction Mimesis, represented in performance: a Play (theatre), play, opera, mime, ballet, etc., performed in a theatre, or on Radio drama, radio or television.Elam (1980, 98). Considered as a g ...

, and popular appeal has drawn comparisons to Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

.

As a social critic, Lope de Vega—like Cervantes—challenged traditional Spanish institutions, including the aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

, chivalry

Chivalry, or the chivalric language, is an informal and varying code of conduct that developed in Europe between 1170 and 1220. It is associated with the medieval Christianity, Christian institution of knighthood, with knights being members of ...

, and rigid moral codes. His artistic approach contrasted with the religious asceticism of Francisco Zurbarán. His ''cloak-and-sword'' plays, which combined intrigue, romance, and comedy, influenced his literary successor, Pedro Calderón de la Barca

Pedro Calderón de la Barca y Barreda González de Henao Ruiz de Blasco y Riaño (17 January 160025 May 1681) (, ; ) was a Spanish dramatist, poet, and writer. He is known as one of the most distinguished Spanish Baroque literature, poets and ...

, who continued the tradition into the late 17th century.

Poetry

This period also produced some of the most important Spanish works of poetry. The introduction and influence of Italian Renaissance verse are apparent perhaps most vividly in the works of Garcilaso de la Vega and illustrate a profound influence on later poets. Mystical literature in Spanish reached its summit with the works of San Juan de la Cruz andTeresa of Ávila

Teresa of Ávila (born Teresa Sánchez de Cepeda Dávila y Ahumada; 28March 15154or 15October 1582), also called Saint Teresa of Jesus, was a Carmelite nun and prominent Spanish mystic and religious reformer.

Active during the Counter-Re ...

. Baroque poetry was dominated by the contrasting styles of Francisco de Quevedo

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Santibáñez Villegas, Order of Santiago, Knight of the Order of Santiago (; 14 September 1580 – 8 September 1645) was a Spanish nobleman, politician and writer of the Baroque era. Along with his lifelong rival, ...

and Luis de Góngora

Luis de Góngora y Argote (born Luis de Argote y Góngora; ; 11 July 1561 – 24 May 1627) was a Spanish Baroque lyric poet and a Catholic prebendary for the Church of Córdoba. Góngora and his lifelong rival, Francisco de Quevedo, are widel ...

; both had a lasting influence on subsequent writers and even on the Spanish language itself.

Lope de Vega

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (; 25 November 156227 August 1635) was a Spanish playwright, poet, and novelist who was a key figure in the Spanish Golden Age (1492–1659) of Spanish Baroque literature, Baroque literature. In the literature of ...

was a gifted poet of his own, and there were a vast quantity of remarkable poets at that time, though less known: Francisco de Rioja, Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola

Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola (August 1562February 4, 1631), Spain, Spanish poet and historian.

Biography

Bartolomé Leonardo de Argensola was baptized at Barbastro on August 26, 1562. He studied at Huesca, took orders, and was presented to the ...

, Lupercio Leonardo de Argensola, Bernardino de Rebolledo, Rodrigo Caro, and Andrés Rey de Artieda. Another poet was Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, from the Spanish colonies overseas in New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( ; Nahuatl: ''Yankwik Kaxtillan Birreiyotl''), originally the Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain. It was one of several ...

(modern day Mexico

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in North America. It is the northernmost country in Latin America, and borders the United States to the north, and Guatemala and Belize to the southeast; while having maritime boundar ...

).

The picaresque

The picaresque novel (Spanish: ''picaresca'', from ''pícaro'', for ' rogue' or 'rascal') is a genre of prose fiction. It depicts the adventures of a roguish but appealing hero, usually of low social class, who lives by his wits in a corrupt ...

genre flourished in this era, describing the life of ''pícaros'', living by their wits in a decadent society. Distinguished examples are ''El buscón

''El Buscón'' (full title ''Historia de la vida del Buscón, llamado Don Pablos, ejemplo de vagamundos y espejo de tacaños'' (literally: History of the life of the Swindler, called Don Pablos, model for hobos and mirror of misers); translated as ...

'', by Francisco de Quevedo

Francisco Gómez de Quevedo y Santibáñez Villegas, Order of Santiago, Knight of the Order of Santiago (; 14 September 1580 – 8 September 1645) was a Spanish nobleman, politician and writer of the Baroque era. Along with his lifelong rival, ...

, ''Guzmán de Alfarache

''Guzmán de Alfarache'' () is a picaresque novel written by Mateo Alemán and published in two parts: the first in Madrid in 1599 with the title , and the second in 1604, titled '.

The works tells the first person adventures of a ''picaro'', a ...

'' by Mateo Alemán, '' Estebanillo González'' and the anonymously published ''Lazarillo de Tormes

''The Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and of His Fortunes and Adversities'' ( ) is a Spanish novella, published anonymously because of its anticlerical content. It was published simultaneously in three cities in 1554: Alcalá de Henares, Burgos a ...

'' (1554), which created the genre.

Other significant authors

*Juana Inés de la Cruz

Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (12 November 1651 – 17 April 1695), was a Hieronymite nun and a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer and poet of the Baroque period, nicknamed "Th ...

was a Mexican writer, philosopher

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, composer

A composer is a person who writes music. The term is especially used to indicate composers of Western classical music, or those who are composers by occupation. Many composers are, or were, also skilled performers of music.

Etymology and def ...

, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

of the Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

period, and Hieronymite nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service and contemplation, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 5 ...

. She wrote poetry and prose dealing with such topics as love

Love is a feeling of strong attraction and emotional attachment (psychology), attachment to a person, animal, or thing. It is expressed in many forms, encompassing a range of strong and positive emotional and mental states, from the most su ...

, feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

, and religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

. In addition to the two comedies; ''Pawns of a House'' (''Los empeños de una casa'') and ''Love is but a Labyrinth'' (''Amor es mas laberinto''), Sor Juana is attributed as the author of a possible ending to the comedy by Agustin de Salazar, ''The Second Celestina'' (''La Segunda Celestina'').

* Alonso de Ercilla

Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga (7 August 153329 November 1594) was a Spanish soldier and poet, born in Madrid. While in Chile (1556–63) he fought against the Araucanians (Mapuche), and there he began the epic poem '' La Araucana'', considered one ...

wrote the epic poem '' La Araucana'' about the Spanish conquest

The Spanish Empire, sometimes referred to as the Hispanic Monarchy or the Catholic Monarchy, was a colonial empire that existed between 1492 and 1976. In conjunction with the Portuguese Empire, it ushered in the European Age of Discovery. It ...

of Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

.

* Gil Vicente was Portuguese, but his influence on Spanish playwriting was so wide that he is often considered part of the Spanish Golden Era.

* Francisco de Avellaneda was a prolific writer of short comedies and dances.

Other well-known playwrights of the period include:

* Alonso de Castillo Solórzano

* Tirso de Molina

* Agustín Moreto

Agustín is a Spanish given name and sometimes a surname. It is related to Augustín.

People with the name include:

Given name

* Agustín Adorni (born 1990), Argentine footballer

* Agustín Allione (born 1994), Argentine footballer

* Ag ...

* Juan Pérez de Montalbán Juan Pérez de Montalbán (1602 – 25 June 1638) was a Spanish Catholic priest, dramatist, poet and novelist.

Biography

He was born in Madrid. At the age of eighteen, he became a licentiate in theology. He was ordained priest in 1625 and appointed ...

* Juan Ruiz de Alarcón

* Guillén de Castro

* Antonio Mira de Amescua

Rhetoric

As elsewhere in Europe, Spanish scholars participated in thehumanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

recovery and theorizing of Greek and Roman rhetorics. Early Spanish humanists include Antonio Nebrija and Juan Luis Vives

Juan Luis Vives y March (; ; ; ; 6 March 6 May 1540) was a Spaniards, Spanish (Valencian people, Valencian) scholar and Renaissance humanist who spent most of his adult life in the southern Habsburg Netherlands. His beliefs on the soul, insigh ...