Scotland In The Early Modern Period on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Scotland in the early modern period refers, for the purposes of this article, to

While these events progressed Queen Mary had been raised as a Catholic in France, and married to the Dauphin of France, who became king as Francis II in 1559, making her

While these events progressed Queen Mary had been raised as a Catholic in France, and married to the Dauphin of France, who became king as Francis II in 1559, making her

In 1625, James VI died and was succeeded by his son Charles I. Although born in Scotland, Charles had become estranged from his northern kingdom, with his first visit being for his Scottish coronation in 1633, when he was crowned in

In 1625, James VI died and was succeeded by his son Charles I. Although born in Scotland, Charles had become estranged from his northern kingdom, with his first visit being for his Scottish coronation in 1633, when he was crowned in

The Scots assembled a force of about 12,000, some of which were returned veterans of the

The Scots assembled a force of about 12,000, some of which were returned veterans of the

As the civil war in England developed into a long and protracted conflict, both the King and the English Parliamentarians appealed to the Scots for military aid. The Covenanters opted to side with Parliament and in 1643 they entered into a

As the civil war in England developed into a long and protracted conflict, both the King and the English Parliamentarians appealed to the Scots for military aid. The Covenanters opted to side with Parliament and in 1643 they entered into a

Charles died in 1685 and his brother succeeded him as James VII of Scotland (and II of England). James put Catholics in key positions in the government and even attendance at a conventicle was made punishable by death. He disregarded parliament, purged the council and forced through

Charles died in 1685 and his brother succeeded him as James VII of Scotland (and II of England). James put Catholics in key positions in the government and even attendance at a conventicle was made punishable by death. He disregarded parliament, purged the council and forced through

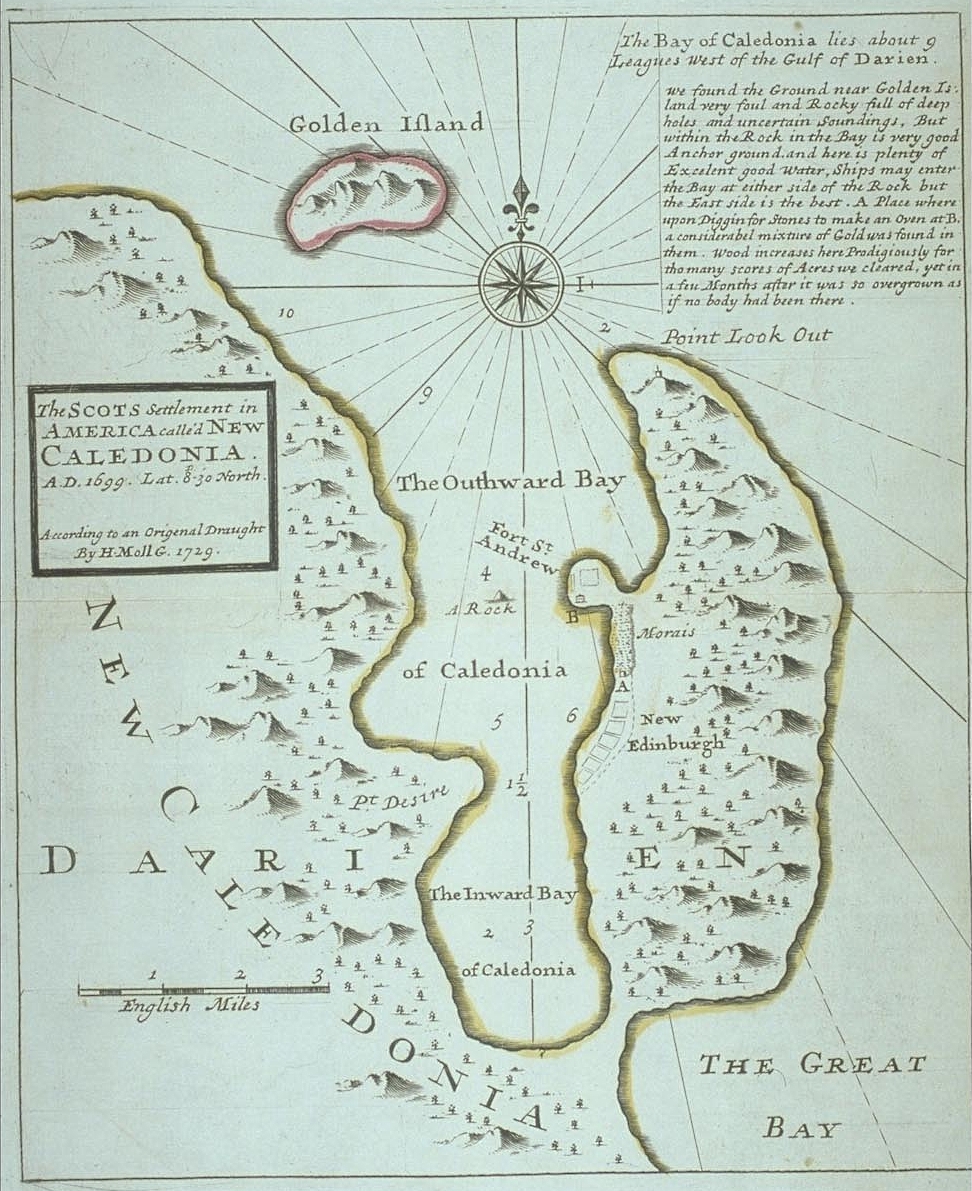

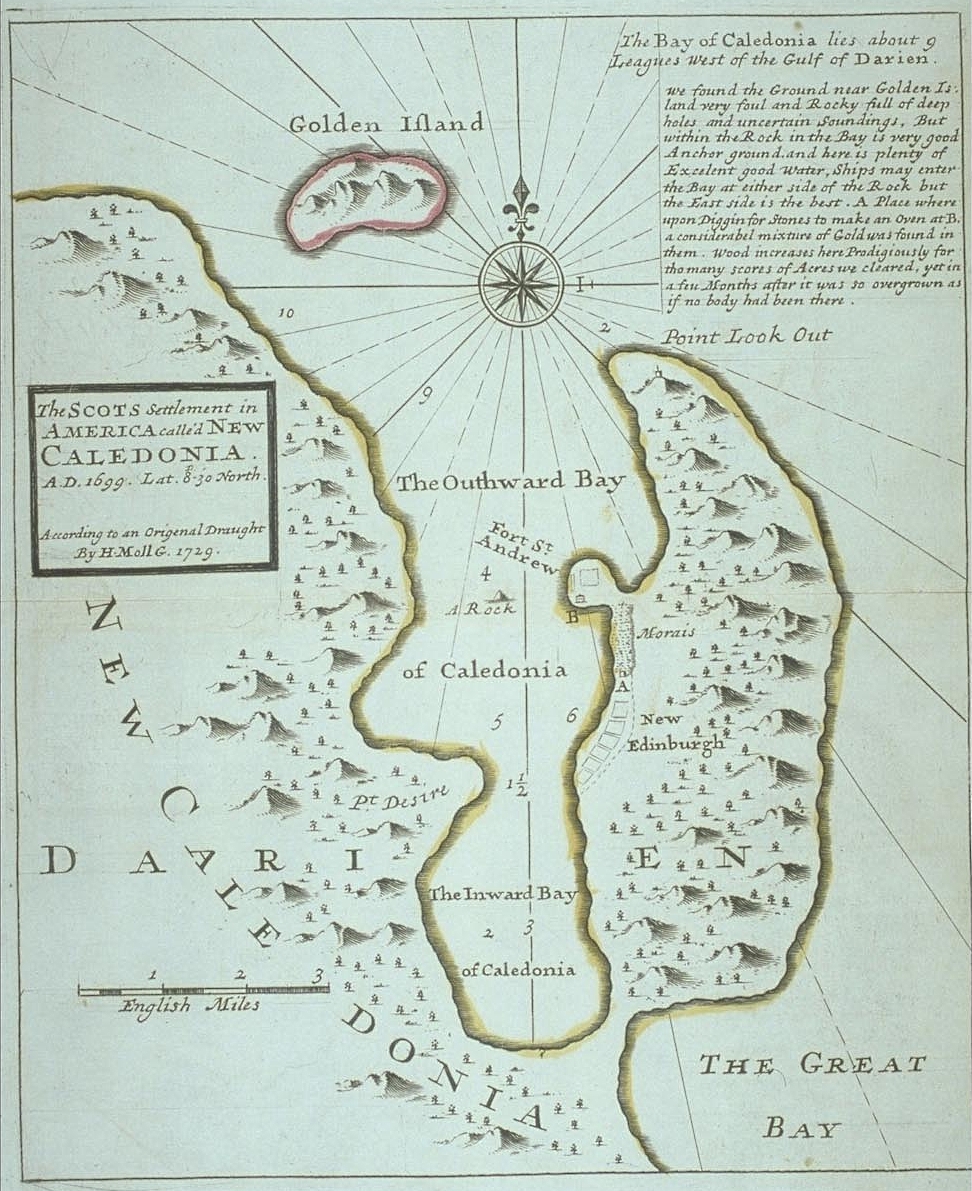

The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw the generally favourable economic conditions that had dominated since the Restoration come to an end. There was a slump in trade with the Baltic and France from 1689 to 1691, caused by French protectionism and changes in the Scottish cattle trade, followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696 and 1698–99), known as the "seven ill years".R. Mitchison, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), , pp. 291–2 and 301-2. The result was severe famine and depopulation, particularly in the north. The Parliament of Scotland of 1695 enacted proposals that might help the desperate economic situation, including setting up the

The closing decade of the seventeenth century saw the generally favourable economic conditions that had dominated since the Restoration come to an end. There was a slump in trade with the Baltic and France from 1689 to 1691, caused by French protectionism and changes in the Scottish cattle trade, followed by four years of failed harvests (1695, 1696 and 1698–99), known as the "seven ill years".R. Mitchison, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), , pp. 291–2 and 301-2. The result was severe famine and depopulation, particularly in the north. The Parliament of Scotland of 1695 enacted proposals that might help the desperate economic situation, including setting up the

Jacobitism was revived by the unpopularity of the union.M. Pittock, ''Jacobitism'' (St. Martin's Press, 1998), , p. 32. In 1708 James Francis Edward Stuart, the son of James VII, who became known as "The Old Pretender", attempted an invasion with a French fleet carrying 6,000 men, but the Royal Navy prevented it from landing troops. A more serious attempt occurred in 1715, soon after the death of Anne and the accession of the first Hanoverian king, the eldest son of Sophie, as

Jacobitism was revived by the unpopularity of the union.M. Pittock, ''Jacobitism'' (St. Martin's Press, 1998), , p. 32. In 1708 James Francis Edward Stuart, the son of James VII, who became known as "The Old Pretender", attempted an invasion with a French fleet carrying 6,000 men, but the Royal Navy prevented it from landing troops. A more serious attempt occurred in 1715, soon after the death of Anne and the accession of the first Hanoverian king, the eldest son of Sophie, as

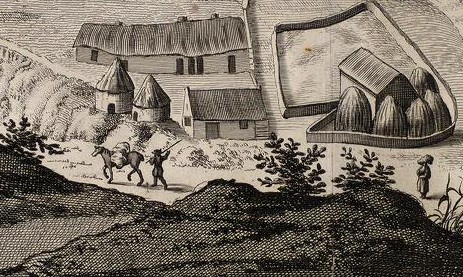

At the beginning of the era, with difficult terrain, poor roads and methods of transport there was little trade between different areas of the country and most settlements depended on what was produced locally, often with very little in reserve in bad years. Most farming was based on the lowland fermtoun or highland baile, settlements of a handful of families that jointly farmed an area notionally suitable for two or three plough teams, allocated in

At the beginning of the era, with difficult terrain, poor roads and methods of transport there was little trade between different areas of the country and most settlements depended on what was produced locally, often with very little in reserve in bad years. Most farming was based on the lowland fermtoun or highland baile, settlements of a handful of families that jointly farmed an area notionally suitable for two or three plough teams, allocated in  In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, with four periods of famine prices between 1620 and 1625. The invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy, with the destruction of crops and the disruption of markets resulting in some of the most rapid price rises of the century. Under the Commonwealth, the country was relatively highly taxed, but gained access to English markets. After the Restoration the formal frontier with England was re-established, along with its customs duties. Economic conditions were generally favourable from 1660 to 1688, as land owners promoted better tillage and cattle-raising. The monopoly of royal

In the early seventeenth century famine was relatively common, with four periods of famine prices between 1620 and 1625. The invasions of the 1640s had a profound impact on the Scottish economy, with the destruction of crops and the disruption of markets resulting in some of the most rapid price rises of the century. Under the Commonwealth, the country was relatively highly taxed, but gained access to English markets. After the Restoration the formal frontier with England was re-established, along with its customs duties. Economic conditions were generally favourable from 1660 to 1688, as land owners promoted better tillage and cattle-raising. The monopoly of royal

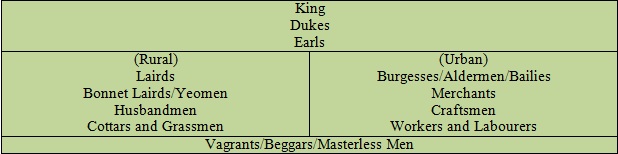

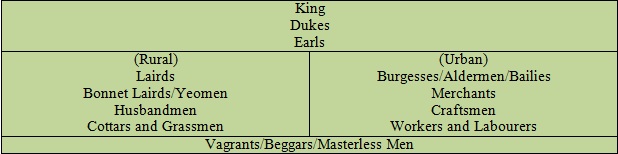

Below the king were a small number of

Below the king were a small number of

There are almost no reliable sources with which to track the population of Scotland before the late seventeenth century. Estimates based on English records suggest that by the end of the Middle Ages, the

There are almost no reliable sources with which to track the population of Scotland before the late seventeenth century. Estimates based on English records suggest that by the end of the Middle Ages, the

In late medieval Scotland there is evidence of occasional prosecutions of individuals for causing harm through witchcraft, but these may have been declining in the first half of the sixteenth century. In the aftermath of the initial Reformation settlement, Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act 1563, similar to that passed in England one year earlier, which made witchcraft a capital crime. Despite the fact that Scotland probably had about one quarter of the population of England, it would have three times the number of witchcraft prosecutions, at about 6,000 for the entire period. James VI's visit to Denmark, a country familiar with witch hunts, may have encouraged an interest in the study of witchcraft. After his return to Scotland, he attended the

In late medieval Scotland there is evidence of occasional prosecutions of individuals for causing harm through witchcraft, but these may have been declining in the first half of the sixteenth century. In the aftermath of the initial Reformation settlement, Parliament passed the Witchcraft Act 1563, similar to that passed in England one year earlier, which made witchcraft a capital crime. Despite the fact that Scotland probably had about one quarter of the population of England, it would have three times the number of witchcraft prosecutions, at about 6,000 for the entire period. James VI's visit to Denmark, a country familiar with witch hunts, may have encouraged an interest in the study of witchcraft. After his return to Scotland, he attended the

Population growth and economic dislocation from the second half of the sixteenth century led to a growing problem of vagrancy. The government reacted with three major pieces of legislation in 1574, 1579 and 1592. The kirk became a major element of the system of poor relief and justices of the peace were given responsibility for dealing with the issue. The 1574 act was modelled on the English act passed two years earlier and limited relief to the deserving poor of the old, sick and infirm, imposing draconian punishments on a long list of "masterful beggars", including jugglers, palmisters and unlicensed tutors. Parish deacons, elders or other overseers were to draw up lists of deserving poor and each would be assessed. Those not belonging to the parish were to be sent back to their place of birth and might be put in the stocks or otherwise punished, probably actually increasing the level of vagrancy. Unlike the English act, there was no attempt to provide work for the able-bodied poor.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 166–8. In practice, the strictures on begging were often disregarded in times of extreme hardship.

This legislation provided the basis of what would later be known as the "Old Poor Law" in Scotland, which remained in place until the mid-nineteenth century. Most subsequent legislation built on the principles of provision for the local deserving poor and punishment of mobile and undeserving "sturdie beggars". The most important later act was that of 1649, which declared that local heritors were to be assessed by kirk session to provide the financial resources for local relief, rather than relying on voluntary contributions. The system was largely able to cope with the general level of poverty and minor crises, helping the old and infirm to survive and provide life support in periods of downturn at relatively low cost, but was overwhelmed in the major subsistence crisis of the 1690s.

Population growth and economic dislocation from the second half of the sixteenth century led to a growing problem of vagrancy. The government reacted with three major pieces of legislation in 1574, 1579 and 1592. The kirk became a major element of the system of poor relief and justices of the peace were given responsibility for dealing with the issue. The 1574 act was modelled on the English act passed two years earlier and limited relief to the deserving poor of the old, sick and infirm, imposing draconian punishments on a long list of "masterful beggars", including jugglers, palmisters and unlicensed tutors. Parish deacons, elders or other overseers were to draw up lists of deserving poor and each would be assessed. Those not belonging to the parish were to be sent back to their place of birth and might be put in the stocks or otherwise punished, probably actually increasing the level of vagrancy. Unlike the English act, there was no attempt to provide work for the able-bodied poor.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 166–8. In practice, the strictures on begging were often disregarded in times of extreme hardship.

This legislation provided the basis of what would later be known as the "Old Poor Law" in Scotland, which remained in place until the mid-nineteenth century. Most subsequent legislation built on the principles of provision for the local deserving poor and punishment of mobile and undeserving "sturdie beggars". The most important later act was that of 1649, which declared that local heritors were to be assessed by kirk session to provide the financial resources for local relief, rather than relying on voluntary contributions. The system was largely able to cope with the general level of poverty and minor crises, helping the old and infirm to survive and provide life support in periods of downturn at relatively low cost, but was overwhelmed in the major subsistence crisis of the 1690s.

For the early part of the era, the authority of the crown was limited by the large number of minorities it had seen since the early fifteenth century. This tended to decrease the level of royal revenues, as regents often alienated land and revenues. Regular taxation was adopted from 1581 and afterwards was called on with increasing frequency and scale until in 1612 a demand of £240,000 resulted in serious opposition. A new tax on annual rents amounting to five per cent on all interest on loans, mainly directed at the merchants of the burghs, was introduced in 1621; but it was widely resented and was still being collected over a decade later. Under Charles I the annual income from all sources in Scotland was under £16,000 sterling and inadequate for the normal costs of government, with the court in London now being financed out of English revenues. The sum of £10,000 a month from the county assessment was demanded by the Cromwellian regime, which Scotland failed to fully supply, but it did contribute £35,000 in excise a year. Although Parliament made a formal grant of £40,000 a year to Charles II, the rising costs civilian government and war meant that this was inadequate to support Scottish government. Under William I and after the Union, engagement in continental and colonial wars led to heavier existing taxes and new taxes, including the Poll and Hearth Taxes.

In the sixteenth century, the court was central to the patronage and dissemination of Renaissance works and ideas. Lavish court display was often tied up with ideas of

For the early part of the era, the authority of the crown was limited by the large number of minorities it had seen since the early fifteenth century. This tended to decrease the level of royal revenues, as regents often alienated land and revenues. Regular taxation was adopted from 1581 and afterwards was called on with increasing frequency and scale until in 1612 a demand of £240,000 resulted in serious opposition. A new tax on annual rents amounting to five per cent on all interest on loans, mainly directed at the merchants of the burghs, was introduced in 1621; but it was widely resented and was still being collected over a decade later. Under Charles I the annual income from all sources in Scotland was under £16,000 sterling and inadequate for the normal costs of government, with the court in London now being financed out of English revenues. The sum of £10,000 a month from the county assessment was demanded by the Cromwellian regime, which Scotland failed to fully supply, but it did contribute £35,000 in excise a year. Although Parliament made a formal grant of £40,000 a year to Charles II, the rising costs civilian government and war meant that this was inadequate to support Scottish government. Under William I and after the Union, engagement in continental and colonial wars led to heavier existing taxes and new taxes, including the Poll and Hearth Taxes.

In the sixteenth century, the court was central to the patronage and dissemination of Renaissance works and ideas. Lavish court display was often tied up with ideas of  James V was the first Scottish monarch to wear the closed imperial crown, in place of the open circlet of medieval kings, suggesting a claim to absolute authority within the kingdom. His

James V was the first Scottish monarch to wear the closed imperial crown, in place of the open circlet of medieval kings, suggesting a claim to absolute authority within the kingdom. His

In the sixteenth century, parliament usually met in

In the sixteenth century, parliament usually met in  Having been officially suspended at the end of the Cromwellian regime, parliament returned after the Restoration of Charles II in 1661. This parliament, later known disparagingly as the 'Drunken Parliament', revoked most of the Presbyterian gains of the last thirty years. Subsequently, Charles' absence from Scotland and use of commissioners to rule his northern kingdom undermined the authority of the body. James' parliament supported him against rivals and attempted rebellions, but after his escape to exile in 1689, William's first parliament was dominated by his supporters and, in contrast to the situation in England, effectively deposed James under the Claim of Right, which offered the crown to William and Mary, placing important limitations on royal power, including the abolition of the Lords of the Articles. The new Williamite parliament would subsequently bring about its own demise by the Act of Union in 1707.

Having been officially suspended at the end of the Cromwellian regime, parliament returned after the Restoration of Charles II in 1661. This parliament, later known disparagingly as the 'Drunken Parliament', revoked most of the Presbyterian gains of the last thirty years. Subsequently, Charles' absence from Scotland and use of commissioners to rule his northern kingdom undermined the authority of the body. James' parliament supported him against rivals and attempted rebellions, but after his escape to exile in 1689, William's first parliament was dominated by his supporters and, in contrast to the situation in England, effectively deposed James under the Claim of Right, which offered the crown to William and Mary, placing important limitations on royal power, including the abolition of the Lords of the Articles. The new Williamite parliament would subsequently bring about its own demise by the Act of Union in 1707.

In the late Middle Ages, justice in Scotland was a mixture of the royal and local, which was often unsystematic with overlapping jurisdictions, undertaken by clerical lawyers, laymen, amateurs and local leaders.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 24–5. Under James IV the legal functions of the council were rationalised, with a royal

In the late Middle Ages, justice in Scotland was a mixture of the royal and local, which was often unsystematic with overlapping jurisdictions, undertaken by clerical lawyers, laymen, amateurs and local leaders.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , pp. 24–5. Under James IV the legal functions of the council were rationalised, with a royal

There were various attempts to create royal naval forces in the fifteenth century. James IV put the enterprise on a new footing, founding a harbour at Newhaven and a dockyard at the Pools of

There were various attempts to create royal naval forces in the fifteenth century. James IV put the enterprise on a new footing, founding a harbour at Newhaven and a dockyard at the Pools of  At the Restoration the Privy Council established a force of several infantry regiments and a few troops of horse and there were attempts to found a national militia on the English model. The standing army was mainly employed in the suppression of Covenanter rebellions and the guerrilla war undertaken by the

At the Restoration the Privy Council established a force of several infantry regiments and a few troops of horse and there were attempts to found a national militia on the English model. The standing army was mainly employed in the suppression of Covenanter rebellions and the guerrilla war undertaken by the

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with

After the Reformation, Scotland's universities underwent a series of reforms associated with

By the early modern period

By the early modern period

Scottish Literature: 1603 and all that

", Association of Scottish Literary Studies (2000), retrieved 18 October 2011. He became patron and member of a loose circle of Scottish Jacobean court poets and musicians, the Castalian Band, which included among others William Fowler and

The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver (c. 1488–1558), a canon of

The outstanding Scottish composer of the first half of the sixteenth century was Robert Carver (c. 1488–1558), a canon of  The return of Mary from France in 1561 to begin her personal reign, and her position as a Catholic, gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Scottish Chapel Royal, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. Like her father she played the lute,

The return of Mary from France in 1561 to begin her personal reign, and her position as a Catholic, gave a new lease of life to the choir of the Scottish Chapel Royal, but the destruction of Scottish church organs meant that instrumentation to accompany the mass had to employ bands of musicians with trumpets, drums, fifes, bagpipes and tabors. Like her father she played the lute,

James V encountered the French version of Renaissance building while visiting for his marriage to Madeleine of Valois in 1536 and his second marriage to Mary of Guise may have resulted in longer term connections and influences.A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , p. 195. Work from his reign largely disregarded the insular style adopted in England under Henry VIII and adopted forms that were recognisably European, beginning with the extensive work at

James V encountered the French version of Renaissance building while visiting for his marriage to Madeleine of Valois in 1536 and his second marriage to Mary of Guise may have resulted in longer term connections and influences.A. Thomas, "The Renaissance", in T. M. Devine and J. Wormald, ''The Oxford Handbook of Modern Scottish History'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), , p. 195. Work from his reign largely disregarded the insular style adopted in England under Henry VIII and adopted forms that were recognisably European, beginning with the extensive work at  Calvinists rejected ornamentation in places of worship, with no need for elaborate buildings divided up by ritual, resulting in the widespread destruction of Medieval church furnishings, ornaments and decoration. There was a need to adapt and build new churches suitable for reformed services, particularly putting the pulpit and preaching at the centre of worship. Many of the earliest buildings were simple gabled rectangles, a style that continued to be built into the seventeenth century. A variation of the rectangular church that developed in post-Reformation Scotland was the T-shaped plan, often used when adapting existing churches, which allowed the maximum number of parishioners to be near the pulpit. In the seventeenth century a

Calvinists rejected ornamentation in places of worship, with no need for elaborate buildings divided up by ritual, resulting in the widespread destruction of Medieval church furnishings, ornaments and decoration. There was a need to adapt and build new churches suitable for reformed services, particularly putting the pulpit and preaching at the centre of worship. Many of the earliest buildings were simple gabled rectangles, a style that continued to be built into the seventeenth century. A variation of the rectangular church that developed in post-Reformation Scotland was the T-shaped plan, often used when adapting existing churches, which allowed the maximum number of parishioners to be near the pulpit. In the seventeenth century a

Surviving stone and wood carvings, wall paintings and tapestries suggest the richness of sixteenth century royal art. At Stirling castle stone carvings on the royal palace from the reign of James V are taken from German patterns, and like the surviving carved oak portrait roundels from the King's Presence Chamber, known as the Stirling Heads, they include contemporary, biblical and classical figures. Scotland's ecclesiastical art suffered as a result of Reformation

Surviving stone and wood carvings, wall paintings and tapestries suggest the richness of sixteenth century royal art. At Stirling castle stone carvings on the royal palace from the reign of James V are taken from German patterns, and like the surviving carved oak portrait roundels from the King's Presence Chamber, known as the Stirling Heads, they include contemporary, biblical and classical figures. Scotland's ecclesiastical art suffered as a result of Reformation

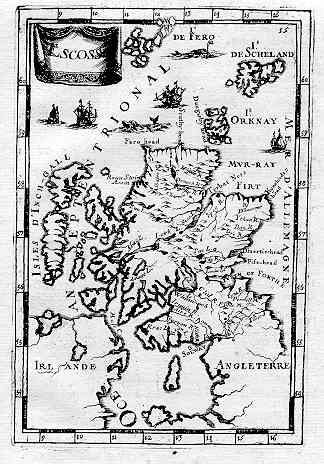

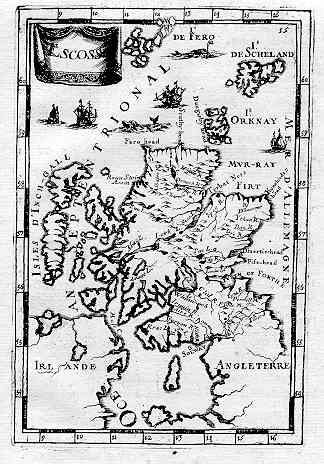

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

between the death of James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

in 1513 and the end of the Jacobite risings

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

in the mid-eighteenth century. It roughly corresponds to the early modern period in Europe, beginning with the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

and Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

and ending with the start of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

.

After a long minority, the personal reign of James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

saw the court become a centre of Renaissance patronage, but it ended in military defeat and another long minority for the infant Mary Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

. Scotland hovered between dominance by the English and French, which ended in the Treaty of Edinburgh

The Treaty of Edinburgh (also known as the Treaty of Leith) was a treaty drawn up on 5 July 1560 between the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I of England with the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, and the French representatives o ...

1560, by which both withdrew their troops, but leaving the way open for religious reform. The Scottish Reformation

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th-century Protestant Reformation.

Fr ...

was strongly influenced by Calvinism

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyteri ...

leading to widespread iconoclasm

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

and the introduction of a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

system of organisation and discipline that would have a major impact on Scottish life. In 1561 Mary returned from France, but her personal reign deteriorated into murder, scandal and civil war, forcing her to escape to England where she was later executed. Her escape left her Protestant opponents in power in the name of the infant James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

. In 1603 he inherited the thrones of England and Ireland, creating a dynastic union and moving the centre of royal patronage and power to London.

His son Charles I attempted to impose elements of the English religious settlement on his other kingdoms. Relations gradually deteriorated resulting in the Bishops' Wars

The Bishops' Wars were two separate conflicts fought in 1639 and 1640 between Scotland and England, with Scottish Royalists allied to England. They were the first of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which also include the First and Second En ...

(1637–40), ending in defeat for Charles and helping to bring about the War of Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union under Charles I. They include the 1639 to 1640 Bishops' Wars, ...

involving England and Ireland. In 1643 Scotland entered into another period of civil war with the Royalist armies supporting the king and the Scottish Covenanters entering the war entered the war in support on the English Parliamentary side. Ultimately the parliamentary forces emerged victorious. Later, they allied with Charles who was defeated and executed. Scotland ultimately accepted his son, Charles II, as their king precipitating the Anglo-Scottish War of 1650-1652 which Scotland lost to a parliamentary army under Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, and was occupied and incorporated into the Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

. The Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660 saw the return of episcopacy

A bishop is an ordained member of the clergy who is entrusted with a position of authority and oversight in a religious institution. In Christianity, bishops are normally responsible for the governance and administration of dioceses. The role ...

and an increasingly absolutist regime, resulting in religious and political upheaval and rebellions. With the accession of the openly Catholic James VII, there was increasing disquiet among Protestants. After the Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

of 1688–89, William of Orange and Mary, the daughter of James, were accepted as monarchs. Presbyterianism was reintroduced and limitations placed on monarchy. After severe economic dislocation in the 1690s there were moves that led to political union with England as the Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

in 1707. The deposed main hereditary line of the Stuarts became a focus for political discontent, known as Jacobitism

Jacobitism was a political ideology advocating the restoration of the senior line of the House of Stuart to the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British throne. When James II of England chose exile after the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, ...

, leading to a series of invasions and rebellions, but with the defeat of the last in 1745, Scotland entered a period of great political stability, economic and intellectual expansion.

Although there was an improving system of roads in early modern Scotland, it remained a country divided by topography, particularly between the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland, and the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act o ...

and the Lowlands. Most of the economic development was in the Lowlands, which saw the beginnings of industrialisation, agricultural improvement and the expansion of eastern burghs, particularly Glasgow, as trade routes to the Americas opened up. The local laird

Laird () is a Scottish word for minor lord (or landlord) and is a designation that applies to an owner of a large, long-established Scotland, Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a Baronage of ...

emerged as a key figure and the heads of names and clans in the Borders and Highlands declined in importance. There was a population expanding towards the end of the period and increasing urbanisation. Social tensions were evident in witch trials and the creation of a system of poor laws

The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief in England and Wales that developed out of the codification of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws in 1587–1598. The system continued until the modern welfare state emerged in the late 1940s.

E ...

. Despite the aggrandisement of the crown and the increase in forms of taxation, revenues remained inadequate. The Privy Council and Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

remained central to government, with changing compositions and importance before the Act of Union in 1707 saw their abolition. The growth of local government saw introduction of Justices of the Peace and Commissioners of Supply

Commissioners of Supply were local administrative bodies in Scotland from 1667 to 1930. Originally established in each sheriffdom to collect tax, they later took on much of the responsibility for the local government of the counties of Scotland. ...

, while the law saw the increasing importance of royal authority and professionalisation. The expansion of parish schools and reform of universities heralded the beginnings of an intellectual flowering in the Enlightenment. There was also a flowering of Scottish literature before the loss of the court as a centre of patronage at the beginning of the seventeenth century. The tradition of church music was fundamentally changed by the Reformation, with the loss of complex polyphonic music

Polyphony ( ) is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just one voice (monophony) or a texture with one dominant melodic voice accompanied by chords (h ...

for a new tradition of metrical psalms singing. In architecture, royal building was strongly influenced by Renaissance styles, while the houses of the great lairds adopted a hybrid form known as Scots baronial

Scottish baronial or Scots baronial is an architectural style of 19th-century Gothic Revival architecture, Gothic Revival which Revivalism (architecture), revived the forms and ornaments of historical Architecture of Scotland in the Middle Ages, ...

and after the Restoration was influenced by Palladian

Palladian architecture is a European architectural style derived from the work of the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio (1508–1580). What is today recognised as Palladian architecture evolved from his concepts of symmetry, perspective and ...

and Baroque

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western Style (visual arts), style of Baroque architecture, architecture, Baroque music, music, Baroque dance, dance, Baroque painting, painting, Baroque sculpture, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from ...

styles. In church architecture a distinctive plain style based on a T-plan emerged. The Reformation also had a major impact on art, with a loss of church patronage leading to a tradition of painted ceilings and walls and the beginnings of a tradition of portraiture and landscape painting.

Political history

Sixteenth century

James V

The death ofJames IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

at the Battle of Flodden

The Battle of Flodden, Flodden Field, or occasionally Branxton or Brainston Moor was fought on 9 September 1513 during the War of the League of Cambrai between the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland and resulted in an English victory ...

in 1513 meant a long period of regency

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

in the name of his infant son James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

. He was declared an adult in 1524, but the next year Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus

Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus (c. 148922 January 1557) was a Scottish nobleman active during the reigns of James V and Mary, Queen of Scots. He was the son of George, Master of Angus, who was killed at the Battle of Flodden, and succ ...

, the young king's stepfather, took custody of James and held him as a virtual prisoner for three years, exercising power on his behalf. He finally managed to escape from the custody of the regents in 1528 and began to take revenge on a number of them and their families.J. Wormald, ''Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), , p. 12. He continued his father's policy of subduing the rebellious Highlands, Western and Northern isles and the troublesome borders. He took punitive measures against the Clan Douglas in the north, summarily executed John Armstrong of Liddesdale

Liddesdale is a district in the Roxburghshire, County of Roxburgh, southern Scotland. It includes the area of the valley of the Liddel Water that extends in a south-westerly direction from the vicinity of Peel Fell to the River Esk, Dumfries and ...

and carried out royal progresses to underline his authority. He also continued the French Auld alliance

The Auld Alliance ( Scots for "Old Alliance") was an alliance between the kingdoms of Scotland and France against England made in 1295. The Scots word ''auld'', meaning ''old'', has become a partly affectionate term for the long-lasting asso ...

that had been in place since the fourteenth century, marrying first the French princess Madeleine of Valois and then after her death Marie of Guise. He increased crown revenues by heavily taxing the church, taking £72,000 in four years, and embarked on a major programme of building at royal palaces. He avoided pursuing the major structural and theological changes to the church undertaken by his contemporary Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

in England. He used the Church as a source of offices for his many illegitimate children and his favourites, particularly David Beaton

David Beaton (also Beton or Bethune; 29 May 1546) was Archbishop of St Andrews and the last Scottish cardinal prior to the Reformation.

Life

David Beaton was said to be the fifth son of fourteen children born to John Beaton (Bethune) of Balf ...

, who became Archbishop of Saint Andrews and a Cardinal. James V's domestic and foreign policy successes were overshadowed by another disastrous campaign against England that led to an overwhelming defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss

The Battle of Solway Moss took place on Solway Moss near the River Esk on the English side of the Anglo-Scottish border in November 1542 between English and Scottish forces.

The Scottish King James V had refused to break from the Catholic Chu ...

(1542). James died a short time later, a demise blamed by contemporaries on "a broken heart". The day before his death, he was brought news of the birth of an heir: a daughter, who would become Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

.M. Nicholls, ''A History of the Modern British Isles, 1529–1603: the Two Kingdoms'' (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 1999), , p. 87.

"Rough Wooing"

At the beginning of the infant Mary's reign, the Scottish political nation was divided between a pro-French faction, led by Cardinal Beaton and by the Queen's mother, Mary of Guise; and a pro-English faction, headed byJames Hamilton, Earl of Arran

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

. Failure of the pro-English to deliver a marriage between the infant Mary and Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, the son of Henry VIII of England, that had been agreed under the Treaty of Greenwich

The Treaty of Greenwich (also known as the Treaties of Greenwich) contained two agreements both signed on 1 July 1543 in Greenwich between representatives of England and Scotland. The accord, overall, entailed a plan developed by Henry VIII of E ...

(1543), led within two years to an English invasion to enforce the match, later known as the "rough wooing".A. Grant and K. J. Stringer, ''Uniting the Kingdom?: the Making of British History'' (Psychology Press, 1995), , pp. 115–6. This took the form of border skirmishing and several English campaigns into Scotland. In 1547, after the death of Henry VIII, forces under the English regent Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset

Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset, 1st Earl of Hertford, 1st Viscount Beauchamp (150022 January 1552) was an English nobleman and politician who served as Lord Protector of England from 1547 to 1549 during the minority of his nephew King E ...

were victorious at the Battle of Pinkie

The Battle of Pinkie, also known as the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh (), took place on 10 September 1547 on the banks of the River Esk near Musselburgh, Scotland. The last pitched battle between Scotland and England before the Union of the Crowns, ...

, followed up by the occupation of the strategic lowland fortress of Haddington and recruitment of " Assured Scots". Arran and Mary of Guise responded by the Treaty of Haddington. and sent the five-year-old Mary to France, as the intended bride of the dauphin Francis

Francis may refer to:

People and characters

*Pope Francis, head of the Catholic Church (2013–2025)

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

* Francis (surname)

* Francis, a character played by YouTuber Boogie2 ...

, heir to the French throne. Mary of Guise stayed in Scotland to look after the interests of young Mary – and of France – although Arran acted as regent until 1554.

The arrival of French troops helped stiffen resistance to the English, who abandoned Haddington in September 1549 and, after the fall of Protector Somerset in England, withdrew from Scotland completely. From 1554, Marie of Guise took over the regency, maintaining a difficult position, partly by giving limited toleration to Protestant dissent and attempting to diffuse resentment over the continued presence of French troops.J. E. A. Dawson, ''Scotland Re-Formed, 1488–1587'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007), , p. 172. When the Protestant Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudo ...

came to the throne of England in 1558, the English party and the Protestants found their positions aligned and asked for English military support to expel the French. The arrival of the English fleet commanded by William Wynter and English troops led to the besieging of the French forces in Leith

Leith (; ) is a port area in the north of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith and is home to the Port of Leith.

The earliest surviving historical references are in the royal charter authorising the construction of ...

, which fell in July 1560. By this point Mary of Guise had died and French and English troops both withdrew under the Treaty of Edinburgh

The Treaty of Edinburgh (also known as the Treaty of Leith) was a treaty drawn up on 5 July 1560 between the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I of England with the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, and the French representatives o ...

, leaving the young queen in France, but pro-English and Protestant parties in the ascendant.

Protestant Reformation

During the sixteenth century, Scotland underwent aProtestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

that created a predominately Calvinist national kirk (church), which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook, severely reducing the powers of bishops, although not abolishing them. In the earlier part of the century, the teachings of first Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

and then John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

began to influence Scotland, particularly through Scottish scholars who had visited continental and English universities and who had often trained in the Catholic priesthood. English influence was also more direct, supplying books and distributing Bibles and Protestant literature in the Lowlands when they invaded in 1547. Particularly important was the work of the Lutheran Scot Patrick Hamilton. His execution with other Protestant preachers in 1528, and of the Zwingli

Huldrych or Ulrich Zwingli (1 January 1484 – 11 October 1531) was a Swiss Christian theologian, musician, and leader of the Reformation in Switzerland. Born during a time of emerging Swiss patriotism and increasing criticism of the Swi ...

-influenced George Wishart

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant martyrs burned at the stake as a heretic.

George Wishart was the son of James and brother of Sir John of Pitarrow ...

in 1546, who was burnt at the stake in St. Andrews on the orders of Cardinal Beaton, did nothing to stem the growth of these ideas. Wishart's supporters, who included a number of Fife lairds, assassinated Beaton soon after and seized St Andrews Castle, which they held for a year before they were defeated with the help of French forces. The survivors, including chaplain John Knox

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

, being condemned to be galley slaves, helping to create resentment of the French and martyrs for the Protestant cause.

Limited toleration and the influence of exiled Scots and Protestants in other countries, led to the expansion of Protestantism, with a group of lairds declaring themselves Lords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves the Faithful, were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scottish ...

in 1557 and representing their interests politically. The collapse of the French alliance and English intervention in 1560 meant that a relatively small, but highly influential, group of Protestants were in a position to impose reform on the Scottish church. A confession of faith, rejecting papal jurisdiction and the mass, was adopted by Parliament in 1560, while the young Mary, Queen of Scots, was still in France. Knox, having escaped the galleys and spent time in Geneva, where he had become a follower of Calvin, emerged as the most significant figure. The Calvinism of the reformers led by Knox resulted in a settlement that adopted a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

system and rejected most of the elaborate trappings of the medieval church. This gave considerable power within the new kirk to local lairds, who often had control over the appointment of the clergy, and resulting in widespread, but generally orderly, iconoclasm

Iconoclasm ()From . ''Iconoclasm'' may also be considered as a back-formation from ''iconoclast'' (Greek: εἰκοκλάστης). The corresponding Greek word for iconoclasm is εἰκονοκλασία, ''eikonoklasia''. is the social belie ...

. At this point the majority of the population was probably still Catholic in persuasion and the kirk would find it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.

Mary, Queen of Scots

While these events progressed Queen Mary had been raised as a Catholic in France, and married to the Dauphin of France, who became king as Francis II in 1559, making her

While these events progressed Queen Mary had been raised as a Catholic in France, and married to the Dauphin of France, who became king as Francis II in 1559, making her queen consort of France

This is a list of the women who were queen consort, queens or empresses as wives of List of French monarchs, French monarchs from the 843 Treaty of Verdun, which gave rise to West Francia, until 1870, when the French Third Republic was declared ...

. This also made her family with King Henry and Queen Catherine of France. When Francis died in 1560, Mary, now 19, elected to return to Scotland to take up the government in a hostile environment. Despite her private deeply catholic religion, she did not attempt to re-impose Catholicism on her largely Protestant subjects, thus angering the chief Catholic nobles. Her six-year personal reign was marred by a series of crises, largely caused by the intrigues and rivalries of the leading nobles. The murder of her secretary, David Riccio, was followed by that of her unpopular second husband Lord Darnley, father of her infant son, and her abduction by and marriage to the Earl of Bothwell, who was implicated in Darnley's murder.

Mary and Bothwell confronted the lords at Carberry Hill

The Battle of Carberry Hill took place on 15 June 1567, near Musselburgh, East Lothian, a few miles east of Edinburgh, Scotland. A number of Scottish lords objected to the rule of Mary, Queen of Scots, after she had married the James Hepburn, 4 ...

and after their forces melted away, he fled and she was captured by Bothwell's rivals. Mary was imprisoned in Lochleven Castle

Lochleven Castle is a ruined castle on an island in Loch Leven, in the Perth and Kinross local authority area of Scotland. Possibly built around 1300, the castle was the site of military action during the Wars of Scottish Independence (1296–1 ...

, and in July 1567, was forced to abdicate in favour of her 13-month-old son James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

. Mary eventually escaped and attempted to regain the throne by force. After her defeat at the Battle of Langside

The Battle of Langside was fought on 13 May 1568 between forces loyal to Mary, Queen of Scots, and forces acting in the name of her infant son James VI. Mary’s short period of personal rule ended in 1567 in recrimination, intrigue, and disast ...

by forces led by Regent Moray in 1568, she took refuge in England. In Scotland the regents fought a civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

on behalf of the king against his mother's supporters. In England, Mary became a focal point for Catholic conspirators and was eventually tried for treason and executed on the orders of her kinswoman Elizabeth I.

James VI

James VI was crowned King of Scots at the age of 13 months on 29 July 1567. He was brought up as a Protestant, while the country was run by a series of regents. In 1579 the Frenchman Esmé Stewart, Sieur d'Aubigny, first cousin of James' father Lord Darnley, arrived in Scotland and quickly established himself as the closest of the then 13-year-old James's powerful malefavourite

A favourite was the intimate companion of a ruler or other important person. In Post-classical Europe, post-classical and Early modern Europe, early-modern Europe, among other times and places, the term was used of individuals delegated signifi ...

s; he was created Earl of Lennox

The Earl or Mormaer of Lennox was the ruler of the region of the Lennox in western Scotland. It was first created in the 12th century for David of Scotland, Earl of Huntingdon and later held by the Stewart dynasty.

Ancient earls

The first e ...

by the king in 1580, and Duke of Lennox

The title Duke of Lennox has been created several times in the peerage of Scotland, for Clan Stewart of Darnley. The dukedom, named for the district of Lennox in Dumbarton

Dumbarton (; , or ; or , meaning 'fort of the Britons (histo ...

in 1581. Lennox was distrusted by Scottish Calvinists

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Christian, Presbyterian, ...

and in August 1582, in what became known as the Raid of Ruthven

The Raid of Ruthven, the kidnapping of King James VI of Scotland, was a political conspiracy in Scotland which took place on 23 August 1582."Ruthven, William", by T. F. Henderson, in ''Dictionary of National Biography'', Volume 50 (Smith, Elder, ...

, the Protestant earls of Gowrie

Gowrie () is a region in central Scotland and one of the original provinces of the Kingdom of Alba. It covered the eastern part of what became Perthshire. It was located to the immediate east of Atholl, and originally included the area aroun ...

and Angus

Angus may refer to:

*Angus, Scotland, a council area of Scotland, and formerly a province, sheriffdom, county and district of Scotland

* Angus, Canada, a community in Essa, Ontario

Animals

* Angus cattle, various breeds of beef cattle

Media

* ...

imprisoned James and forced Lennox to leave Scotland. After James was liberated in June 1583, he assumed increasing control of his kingdom. Between 1584 and 1603, he established effective royal government and relative peace among the lords, assisted by John Maitland of Thirlestane

Thirlestane Castle is a castle set in extensive parklands near Lauder in the Borders of Scotland. The site is aptly named Castle Hill, as it stands upon raised ground. However, the raised land is within Lauderdale, the valley of the Leader Wat ...

, who led the government until 1592. In 1586, James signed the Treaty of Berwick with England, which, with the execution of his mother in 1587, helped clear the way for his succession to the childless Queen Elizabeth I of England. He married Anne of Denmark

Anne of Denmark (; 12 December 1574 – 2 March 1619) was the wife of King James VI and I. She was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from their marriage on 20 August 1589 and List of English royal consorts, Queen of Engl ...

in 1590, daughter of Frederick II, the king of Denmark; they had two sons and a daughter.

Seventeenth century

Union of Crowns

In 1603, James VI King of Scots inherited the throne of theKingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

and left Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

for London where he would reign as James I. The Union was a personal

Personal may refer to:

Aspects of persons' respective individualities

* Privacy

* Personality

* Personal, personal advertisement, variety of classified advertisement used to find romance or friendship

Companies

* Personal, Inc., a Washington, ...

or dynastic union

A dynastic union is a type of union in which different states are governed beneath the same dynasty, with their boundaries, their laws, and their interests remaining distinct from each other.

It is a form of association looser than a personal un ...

, with the crowns remaining both distinct and separate – despite James' best efforts to create a new "imperial" throne of "Great Britain". James retained a keen interest in Scottish affairs, running the government by the rapid interchange of letters, aided by the establishment of an efficient postal system. He controlled everyday policy through the Privy Council of Scotland

The Privy Council of Scotland ( — 1 May 1708) was a body that advised the Scottish monarch. During its existence, the Privy Council of Scotland was essentially considered as the government of the Kingdom of Scotland, and was seen as the most ...

and managed the Parliament of Scotland

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

through the Lords of the Articles

Lords may refer to:

* The plural of Lord

Places

*Lords Creek, a stream in New Hanover County, North Carolina

*Lord's, English Cricket Ground and home of Marylebone Cricket Club and Middlesex County Cricket Club

People

*Traci Lords (born 19 ...

. He also increasingly controlled the meetings of the Scottish General Assembly and increased the number and powers of the Scottish bishops. In 1618, he held a General Assembly and pushed through ''Five Articles'', which included practices that had been retained in England, but largely abolished in Scotland, most controversially kneeling for the reception of communion. Although ratified, they created widespread opposition and resentment and were seen by many as a step back to Catholic practice. Royal authority was more limited in the Highlands, where periodic violence punctuated relationships between the great families of the MacDonalds, Gordons and McGregors and Campbells. The acquisition of the Irish crown along with the English, facilitated a process of settlement by Scots in what was historically the most troublesome area of the kingdom in Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, with perhaps 50,000 Scots settling in the province by the mid-seventeenth century. Attempts to found a Scottish colony in North America in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

were largely unsuccessful, with insufficient funds and willing colonists.

Charles I

In 1625, James VI died and was succeeded by his son Charles I. Although born in Scotland, Charles had become estranged from his northern kingdom, with his first visit being for his Scottish coronation in 1633, when he was crowned in

In 1625, James VI died and was succeeded by his son Charles I. Although born in Scotland, Charles had become estranged from his northern kingdom, with his first visit being for his Scottish coronation in 1633, when he was crowned in St Giles Cathedral

St Giles' Cathedral (), or the High Kirk of Edinburgh, is a parish church of the Church of Scotland in the Old Town of Edinburgh. The current building was begun in the 14th century and extended until the early 16th century; significant alteratio ...

, Edinburgh with full Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

rites.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , p. 202. Charles had relatively few important Scots in his circle and relied heavily in Scottish matters on the generally mistrusted and often indecisive James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Hamilton (19 June 1606 – 9 March 1649), known as the 3rd Marquess of Hamilton from March 1625 until April 1643, was a Scottish nobleman and influential political and military leader during the Thirty Years' War and ...

and the bishops, particularly John Spottiswood, Archbishop of St. Andrews, eventually making him chancellor. At the beginning of his reign, Charles' revocation of alienated lands since 1542 helped secure the finances of the kirk, but it threatened the holdings of the nobility who had gained from the Reformation settlement. His pushing through of legislation and refusal to hear (or legal pursuit of) those raising objections, created further resentment among the nobility.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , p. 203. In England his religious policies caused similar resentment and he ruled without calling a parliament from 1629.

=Bishops' Wars

= In 1635, without reference to a general assembly of the Parliament, the king authorised a book of canons that made him head of the Church, ordained an unpopular ritual and enforced the use of a new liturgy. When the liturgy emerged in 1637 it was seen as an English-style Prayer Book, resulting in anger and widespread rioting, said to have been set off with the throwing of a stool by oneJenny Geddes

Janet "Jenny" Geddes (c. 1600 – c. 1660) was a Scottish people, Scottish market-trader in Edinburgh who is alleged to have thrown a stool at the head of the Minister (Christianity), minister in St Giles' Cathedral in objection to the fir ...

during a service in St Giles Cathedral. The Protestant nobility put themselves at the head of the popular opposition, with Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll emerging as a leading figure. Representatives of various sections of Scottish society drew up the National Covenant

The National Covenant () was an agreement signed by many people of Scotland during 1638, opposing the proposed Laudian reforms of the Church of Scotland (also known as '' the Kirk'') by King Charles I. The king's efforts to impose changes on th ...

on 28 February 1638, objecting to the King's liturgical innovations.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , p. 204. The king's supporters were unable to suppress the rebellion and the king refused to compromise. In December of the same year matters were taken even further, when at a meeting of the General Assembly in Glasgow the Scottish bishops were formally expelled from the Church, which was then established on a full Presbyterian basis.

The Scots assembled a force of about 12,000, some of which were returned veterans of the

The Scots assembled a force of about 12,000, some of which were returned veterans of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

, led by Alexander Leslie

Alexander Leslie, 1st Earl of Leven (4 April 1661) was a Scottish army officer. Born illegitimate and raised as a foster child, he subsequently advanced to the rank of field marshal in Swedish Army, and in Scotland became Lord General in comma ...

, formerly the Field Marshal

Field marshal (or field-marshal, abbreviated as FM) is the most senior military rank, senior to the general officer ranks. Usually, it is the highest rank in an army (in countries without the rank of Generalissimo), and as such, few persons a ...

of the Swedish Army. Charles gathered a force of perhaps 20,000, many of which were ill-trained militia

A militia ( ) is a military or paramilitary force that comprises civilian members, as opposed to a professional standing army of regular, full-time military personnel. Militias may be raised in times of need to support regular troops or se ...

. There were a series of minor actions in the north of Scotland, which secured the Covenanter's rear against Royalist support and skirmishing on the border. As neither side wished to push the matter to a full military conflict, a temporary settlement was concluded, known as the Pacification of Berwick in June 1639, and the First Bishops' War ended with the Covenanters retaining control of the country.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 205–6.

In 1640 Charles attempted again to enforce his authority, opening a second Bishops' War. He recalled the English Parliament, known as the Short Parliament

The Short Parliament was a Parliament of England that was summoned by King Charles I of England on 20 February 1640 and sat from 13 April to 5 May 1640. It was so called because of its short session of only three weeks.

After 11 years of per ...

, but disbanded it after it declined to vote a new subsidy and was critical of his policies. He assembled a poorly provisioned and poorly trained army. The Scots moved south into England, forcing a crossing of the Tyne at Newburn

Newburn is a village and district of Newcastle upon Tyne, in Tyne and Wear, England. Situated on the North bank of the River Tyne, it is built rising up the valley from the river. It is situated approximately from the city centre, east of H ...

to the west of Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne, or simply Newcastle ( , Received Pronunciation, RP: ), is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is England's northernmost metropolitan borough, located o ...

, then occupying the city and eventually most of Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

and Durham. This gave them a stranglehold on the vital coal supply to London.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 208–9. Charles was forced to capitulate, agreeing to most of the Covenanter's demands and paying them £830 a month to support their army. This forced him to recall the English Parliament, known as the Long Parliament

The Long Parliament was an Parliament of England, English Parliament which lasted from 1640 until 1660, making it the longest-lasting Parliament in English and British history. It followed the fiasco of the Short Parliament, which had convened f ...

, which, in exchange for concessions, raised the sum of £200,000 to be paid to the Scots under the Treaty of Ripon

The Treaty of Ripon was a truce between Charles I, King of England, and the Covenanters, a Scottish political movement, which brought a cessation of hostilities to the Second Bishops' War.

The Covenanter movement had arisen in opposition to ...

. The Scots army returned home triumphant. The king's attempts to raise a force in Ireland to invade Scotland from the west prompted a widespread revolt

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

there and as the English moved to outright opposition that resulted in the outbreak of the English Civil War

The English Civil War or Great Rebellion was a series of civil wars and political machinations between Cavaliers, Royalists and Roundhead, Parliamentarians in the Kingdom of England from 1642 to 1651. Part of the wider 1639 to 1653 Wars of th ...

in 1642, he was facing rebellion in all three of his realms.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 209–10.

=Civil wars

= As the civil war in England developed into a long and protracted conflict, both the King and the English Parliamentarians appealed to the Scots for military aid. The Covenanters opted to side with Parliament and in 1643 they entered into a

As the civil war in England developed into a long and protracted conflict, both the King and the English Parliamentarians appealed to the Scots for military aid. The Covenanters opted to side with Parliament and in 1643 they entered into a Solemn League and Covenant

The Solemn League and Covenant was an agreement between the Scottish Covenanters and the leaders of the English Parliamentarians in 1643 during the First English Civil War, a theatre of conflict in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. On 17 August ...

, guaranteeing the Scottish Church settlement and promising further reform in England.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 211–2. In January 1644 a Scots army of 18,000-foot and 3,000 horse and guns under Leslie crossed the border. It helped turn the tide of the war in the North, forcing the royalist army under the Marquis of Newcastle into York where it was besieged by combined Scots and Parliamentary armies. The Royalists were relieved by a force under Prince Rupert

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, Duke of Cumberland, (17 December 1619 ( O.S.) 7 December 1619 (N.S.)– 29 November 1682 (O.S.) December 1682 (N.S) was an English-German army officer, admiral, scientist, and colonial governor. He first rose to ...

, the King's nephew, but the allies under Leslie's command defeated the Royalists decisively at Marston Moor

The Battle of Marston Moor was fought on 2 July 1644, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms of 1639–1653. The combined forces of the English Parliamentarians under Lord Fairfax and the Earl of Manchester and the Scottish Covenanters unde ...

on 2 July, generally seen as the turning point of the war.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 213–4.

In Scotland, former Covenanter James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose

James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose (1612 – 21 May 1650) was a Scottish nobleman, poet, soldier and later viceroy and captain general of Scotland. Montrose initially joined the Covenanters in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, but subsequ ...

led a campaign in favour of the king in the Highlands from 1644. Few Lowland Scots would follow him, but, aided by 1,000 Irish, Highland and Islesmen sent by the Irish Confederates

Confederate Ireland, also referred to as the Irish Catholic Confederation, was a period of Irish Catholic Church, Catholic self-government between 1642 and 1652, during the Irish Confederate Wars, Eleven Years' War. Formed by Catholic aristoc ...

under Alasdair MacDonald (MacColla), he began a highly successful mobile campaign, winning victories over local Covenanter forces at Tippermuir and Aberdeen

Aberdeen ( ; ; ) is a port city in North East Scotland, and is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, third most populous Cities of Scotland, Scottish city. Historically, Aberdeen was within the historic county of Aberdeensh ...

against local levies; at Inverlochy he crushed the Campbells; at Auldearn, Alford and Kilsyth

Kilsyth (; ) is a town and civil parishes in Scotland, civil parish in North Lanarkshire, roughly halfway between Glasgow and Stirling in Scotland. The estimated population is 10,380. The town is famous for the Battle of Kilsyth and the religi ...

he defeated well-led and disciplined armies. He was able to dictate terms to the Covenanters, but as he moved south, his forces, depleted by the loss of MacColla and the Highlanders, were caught and decisively defeated at the Battle of Philiphaugh

The Battle of Philiphaugh was fought on 13 September 1645 during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms near Selkirk in the Scottish Borders. The Royalist army of the Marquis of Montrose was destroyed by the Covenanter army of Sir David Leslie, ...

by an army under David Leslie, nephew of Alexander. Escaping to the north, Montrose attempted to continue the struggle with fresh troops. By this point the king had been heavily defeated at the Battle of Naseby by Parliament's reformed New Model Army

The New Model Army or New Modelled Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 t ...

and surrendered to the Scots forces under Leslie besieging the town of Newark in July 1646. Montrose abandoned the war and left for the continent.J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, ''A History of Scotland'' (London: Penguin, 1991), , pp. 217–8.

Unable to persuade the king to accept a Presbyterian settlement, the Scots exchanged him for half of the £400,000 they were owed by Parliament and returned home. Relations with the English Parliament and the increasingly independent English army grew strained and the balance of power shifted in Scotland, with Hamilton emerging as the leading figure. In 1647 he brokered the Engagement

An engagement or betrothal is the period of time between the declaration of acceptance of a marriage proposal and the marriage itself (which is typically but not always commenced with a wedding). During this period, a couple is said to be ''f ...