Sansovino Library on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Marciana Library or Library of Saint Mark (, but in historical documents commonly referred to as the ) is a

on-line

at . The documents relative to the donation are transcribed in Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., pp. 147–156.The legal act of donation preceded the formal announcement and is dated 14 May 1468. See Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., p. 27, 153–156 and Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., p. 82. Bessarion's first contact with Venice had been in 1438 when, as the newly ordained metropolitan bishop of Nicaea, he arrived with the Byzantine delegation to the Council of Ferrara-Florence, the objective being to heal the In 1463, Bessarion returned to Venice as the

In 1463, Bessarion returned to Venice as the

The construction of the library was an integral part of the (renewal of the city), a vast architectural programme begun under Doge

The construction of the library was an integral part of the (renewal of the city), a vast architectural programme begun under Doge

Work was suspended following the

Work was suspended following the

The effect of the library, overall, is that the entire façade has been encrusted with archaeological artefacts. Statues and carvings abound, and there are no large areas of plain wall. In addition to the abundance of classical decorative elements – obelisks, keystone heads, spandrel figures, and reliefs – the Doric and Ionic orders, each with the appropriate frieze, cornice, and base, follow ancient Roman prototypes, giving the building a sense of authenticity. The proportions, however, do not always respect Vitruvian canons. Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino...'', p. 27 Scamozzi, a rigid classicist, was critical of the arches on the ground floor, considered to be dwarfed and ill-proportioned, and the excessive height of the Ionic entablature with respect to the columns.Scamozzi considered appropriate a ratio between the height of the entablature and the column of 1 to 4 for the Doric order and 1 to 5 of the Ionic order, whereas the ratios in the library are 1 to 3 and 1 to 2 respectively. See Vincenzo Scamozzi, ''L’Idea dell’Architettura Universale'' (Venetiis: ''expensis auctoris'', 1615), Lib. VI, Cap. VII, pp. 20–21. Nevertheless, the classical references were sufficient to satisfy the Venetians’ desire to emulate the great civilizations of Antiquity and to present their own city as the successor of the Roman Republic. At the same time, the design respects many local building traditions and harmonizes with the gothic Doge's Palace through the common use of Istrian limestone, the two-storey arcades, the balustrades, and the elaborate rooflines.

The effect of the library, overall, is that the entire façade has been encrusted with archaeological artefacts. Statues and carvings abound, and there are no large areas of plain wall. In addition to the abundance of classical decorative elements – obelisks, keystone heads, spandrel figures, and reliefs – the Doric and Ionic orders, each with the appropriate frieze, cornice, and base, follow ancient Roman prototypes, giving the building a sense of authenticity. The proportions, however, do not always respect Vitruvian canons. Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino...'', p. 27 Scamozzi, a rigid classicist, was critical of the arches on the ground floor, considered to be dwarfed and ill-proportioned, and the excessive height of the Ionic entablature with respect to the columns.Scamozzi considered appropriate a ratio between the height of the entablature and the column of 1 to 4 for the Doric order and 1 to 5 of the Ionic order, whereas the ratios in the library are 1 to 3 and 1 to 2 respectively. See Vincenzo Scamozzi, ''L’Idea dell’Architettura Universale'' (Venetiis: ''expensis auctoris'', 1615), Lib. VI, Cap. VII, pp. 20–21. Nevertheless, the classical references were sufficient to satisfy the Venetians’ desire to emulate the great civilizations of Antiquity and to present their own city as the successor of the Roman Republic. At the same time, the design respects many local building traditions and harmonizes with the gothic Doge's Palace through the common use of Istrian limestone, the two-storey arcades, the balustrades, and the elaborate rooflines.

Beginning in 1558, the nominated the librarian, a patrician chosen for life. But in 1626, the Senate once again assumed direct responsibility for the nomination of the librarian, whose term was limited by the Great Council in 1775 to three years. Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., p. 211 With few exceptions, the librarians were typically chosen from among the procurators of Saint Mark.

The reform of 1626 established the positions of custodian and attendant, both subordinate to the librarian, with the requirement that the custodian be fluent in Latin and Greek. The attendant was responsible for the general tidiness of the library and was chosen by the procurators, the riformatori, and the librarian. No indications were given regarding the nomination of the custodian, a lifetime appointment, until 1633 when it was prescribed that the election was to be the purview of the in concert with the librarian. To the custodian fell the responsibility for opening and closing the library: opening days (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings) were also fixed whereas access had previously been by appointment only. The custodian assisted readers, including the international scholars attracted by the importance of the manuscripts. Among these were Willem Canter,

Beginning in 1558, the nominated the librarian, a patrician chosen for life. But in 1626, the Senate once again assumed direct responsibility for the nomination of the librarian, whose term was limited by the Great Council in 1775 to three years. Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., p. 211 With few exceptions, the librarians were typically chosen from among the procurators of Saint Mark.

The reform of 1626 established the positions of custodian and attendant, both subordinate to the librarian, with the requirement that the custodian be fluent in Latin and Greek. The attendant was responsible for the general tidiness of the library and was chosen by the procurators, the riformatori, and the librarian. No indications were given regarding the nomination of the custodian, a lifetime appointment, until 1633 when it was prescribed that the election was to be the purview of the in concert with the librarian. To the custodian fell the responsibility for opening and closing the library: opening days (Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings) were also fixed whereas access had previously been by appointment only. The custodian assisted readers, including the international scholars attracted by the importance of the manuscripts. Among these were Willem Canter,

Deposito legale

' ccessed 2 July 2020/ref> The collection was moved from the Doge's Palace to the Zecca, the former mint, in 1904. It is Italian national property, and the library is a state library that depends upon the General Direction for Libraries and Authors' Rights () of the

Saint Mark's Square Museum Ticket

ccessed 26 May 2020/ref>

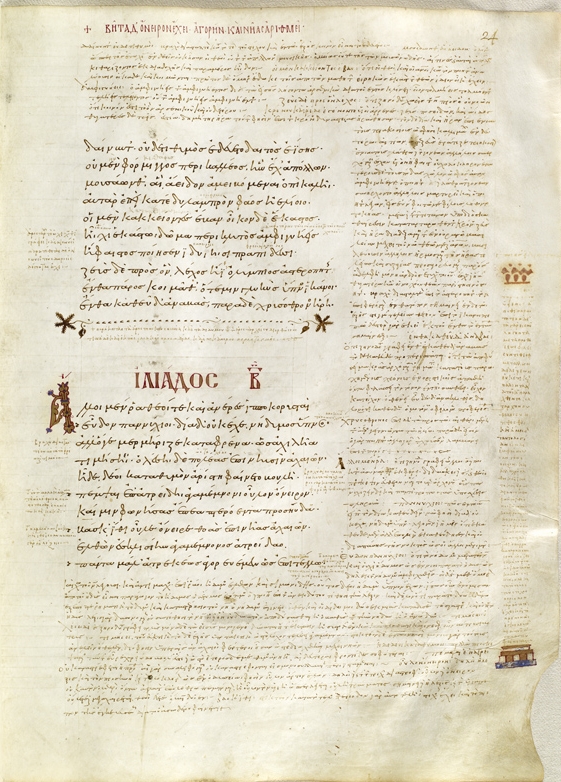

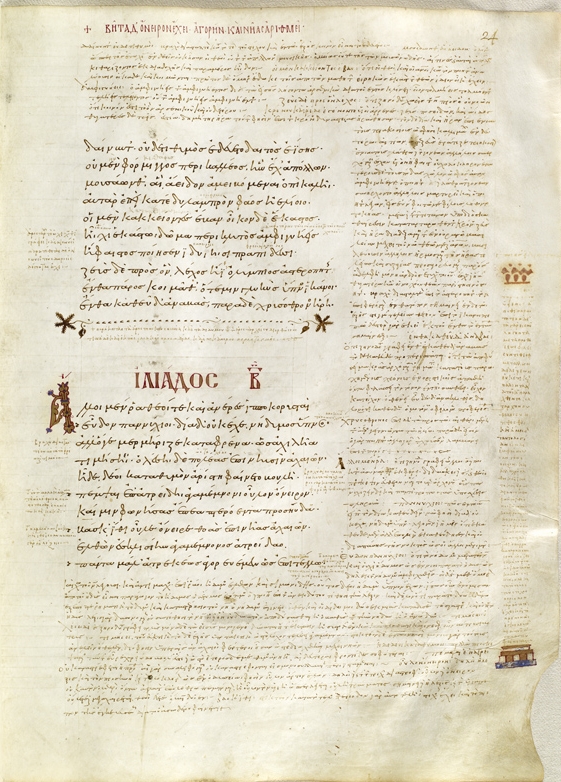

The private library of Cardinal Bessarion constitutes the historical nucleus of the Marciana. In addition to liturgical and theological texts for reference, Bessarion's library initially reflected his particular interests in ancient Greek history,

The private library of Cardinal Bessarion constitutes the historical nucleus of the Marciana. In addition to liturgical and theological texts for reference, Bessarion's library initially reflected his particular interests in ancient Greek history,  Around 1450, Bessarion began to place his ecclesiastical coat of arms on his books and assign shelf marks, an indication that the collection was no longer limited to personal consultation but that he intended to create a lasting library for scholars. In 1454, following the fall of

Around 1450, Bessarion began to place his ecclesiastical coat of arms on his books and assign shelf marks, an indication that the collection was no longer limited to personal consultation but that he intended to create a lasting library for scholars. In 1454, following the fall of

Catalogue of Greek codices

Catalogue of Latin codices (includes French and Italian codices)

{{featured article Archives in Italy Buildings and structures in Venice Jacopo Sansovino buildings Libraries in Venice, Marciana Museums in Venice National libraries in Italy Piazza San Marco Renaissance architecture in Venice Libraries established in the 15th century

public library

A public library is a library, most often a lending library, that is accessible by the general public and is usually funded from public sources, such as taxes. It is operated by librarians and library paraprofessionals, who are also Civil servic ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Italy. It is one of the earliest surviving public libraries and repositories for manuscript

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has ...

s in Italy and holds one of the world's most significant collections of classical texts. It is named after St Mark

Mark the Evangelist (Koine Greek, Koinē Greek: Μᾶρκος, romanized: ''Mârkos''), also known as John Mark (Koine Greek, Koinē Greek language, Greek: Ἰωάννης Μᾶρκος, Romanization of Greek, romanized: ''Iōánnēs Mârkos;'' ...

, the patron saint

A patron saint, patroness saint, patron hallow or heavenly protector is a saint who in Catholicism, Anglicanism, Eastern Orthodoxy or Oriental Orthodoxy is regarded as the heavenly advocate of a nation, place, craft, activity, class, clan, fa ...

of the city.

The library was founded in 1468 when the humanist scholar Cardinal Bessarion

Bessarion (; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the revival of letters in the 15th century. He was educated ...

, bishop of Tusculum and titular Latin patriarch of Constantinople

The Latin Patriarchate of Constantinople was an office established as a result of the Fourth Crusade and its conquest of Constantinople in 1204. It was a Roman Catholic replacement for the Eastern Orthodox Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantino ...

, donated his collection of Greek and Latin manuscripts to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, with the stipulation that a library of public utility be established. The collection was the result of Bessarion's persistent efforts to locate rare manuscripts throughout Greece and Italy and then acquire or copy them as a means of preserving the writings of the classical Greek authors and the literature of Byzantium after the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453. His choice of Venice was primarily due to the city's large community of Greek refugees and its historical ties to the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. The Venetian government was slow, however, to honour its commitment to suitably house the manuscripts with decades of discussion and indecision, owing to a series of military conflicts in the late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries and the resulting climate of political uncertainty. The library was ultimately built during the period of recovery as part of a vast programme of urban renewal aimed at glorifying the republic through architecture and affirming its international prestige as a centre of wisdom and learning.

The original library building is located in Saint Mark's Square, Venice's former governmental centre, with its long façade facing the Doge's Palace

The Doge's Palace (''Doge'' pronounced ; ; ) is a palace built in Venetian Gothic architecture, Venetian Gothic style, and one of the main landmarks of the city of Venice in northern Italy. The palace included government offices, a jail, and th ...

. Constructed between 1537 and 1588, it is considered the masterpiece of the architect Jacopo Sansovino

Jacopo d'Antonio Sansovino (2 July 1486 – 27 November 1570) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor and architect, best known for his works around the Piazza San Marco in Venice. These are crucial works in the history of Venetian Renaissance arc ...

and a key work in Venetian Renaissance architecture

Venetian Renaissance architecture began rather later than in Florence, not really before the 1480s, and throughout the period mostly relied on architects imported from elsewhere in Italy. The city was very rich during the period, and prone to fire ...

. Hartt, ''History of Italian Renaissance Art'', p. 633 The Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

described it as "perhaps the richest and most ornate building that there has been since ancient times up until now" (). The art historian Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (; ; 25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. His best known work is '' The Civilization of the Renaissance in ...

regarded it as "the most magnificent secular Italian building" (), and Frederick Hartt

Frederick Hartt (May 22, 1914 – October 31, 1991) was an Italian Renaissance scholar, author and professor of art history. His books include ''History of Italian Renaissance Art'', '' Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture '' ...

called it "one of the most satisfying structures in Italian architectural history". Also significant for its art, the library holds many works by the great painters of sixteenth-century Venice, making it a comprehensive monument to Venetian Mannerism

Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, spreading by about 1530 and lasting until about the end of the 16th century in Italy, when the Baroque style largely replaced it ...

.

Today, the building is customarily referred to as the '' and is largely a museum. Since 1904, the library offices, the reading rooms, and most of the collection have been housed in the adjoining Zecca, the former mint of the Republic of Venice. The library is now formally known as the . It is the only official institution established by the Venetian Republican government that survives and continues to function.

Historical background

Cathedral libraries andmonastic libraries

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of documents. Topics of interest include accessibility of the collection, acquisition of materials, arrangement and finding tools, the book trade, the influence of th ...

were the principal centres of study and learning throughout Italy in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. But beginning in the fifteenth century, the humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

emphasis on the knowledge of the classical world as essential to the formation of the Renaissance man

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

led to a proliferation of court libraries, patronized by princely rulers, several of which provided a degree of public access. In Venice, an early attempt to found a public library

A public library is a library, most often a lending library, that is accessible by the general public and is usually funded from public sources, such as taxes. It is operated by librarians and library paraprofessionals, who are also Civil servic ...

in emulation of the great libraries of Antiquity

Antiquity or Antiquities may refer to:

Historical objects or periods Artifacts

*Antiquities, objects or artifacts surviving from ancient cultures

Eras

Any period before the European Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries) but still within the histo ...

was unsuccessful, as Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

's personal collection of manuscripts, donated to the republic in 1362, was dispersed at the time of his death.

In 1468, the Byzantine humanist and scholar Cardinal Bessarion

Bessarion (; 2 January 1403 – 18 November 1472) was a Byzantine Greek Renaissance humanist, theologian, Catholic cardinal and one of the famed Greek scholars who contributed to the revival of letters in the 15th century. He was educated ...

donated his collection of 482 Greek and 264 Latin codices

The codex (: codices ) was the historical ancestor format of the modern book. Technically, the vast majority of modern books use the codex format of a stack of pages bound at one edge, along the side of the text. But the term ''codex'' is now r ...

to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, stipulating that a public library be established to ensure their conservation for future generations and availability for scholars. Raines, 'Book Museum of Scholarly Library?...', p. 33Bessarion's private library was among the most important in the fifteenth century. In 1455, the collection of Pope Nicholas V

Pope Nicholas V (; ; 15 November 1397 – 24 March 1455), born Tommaso Parentucelli, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 6 March 1447 until his death in March 1455. Pope Eugene IV made him a Cardinal (Catholic Chu ...

, the largest, contained 1209 codices. Significant private libraries belonged to Niccolò Niccoli (808 volumes) and Coluccio Salutati

Coluccio Salutati (16 February 1331 – 4 May 1406) was an Italian Renaissance humanist and notary, and one of the most important political and cultural leaders of Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history ...

(''circa'' 800 volumes). Among the larger court libraries were those of the Visconti

Visconti is a surname which may refer to:

Italian noble families

* Visconti of Milan, ruled Milan from 1277 to 1447

** Visconti di Modrone, collateral branch of the Visconti of Milan

* Visconti of Pisa and Sardinia, ruled Gallura in Sardinia from ...

(998 volumes in 1426), Federico da Montefeltro

Federico da Montefeltro, also known as Federico III da Montefeltro Order of the Garter, KG (7 June 1422 – 10 September 1482), was one of the most successful mercenary captains (''condottiero, condottieri'') of the Italian Renaissance, and Duk ...

(772 volumes), the Estensi (512 volumes in 1495), and the Gonzaga

Gonzaga may refer to:

Places

*Gonzaga, Lombardy, commune in the province of Mantua, Italy

*Gonzaga, Cagayan, municipality in the Philippines

*Gonzaga, Minas Gerais, town in Brazil

*Forte Gonzaga, fort in Messina, Sicily

Surname

*House of Gonza ...

(''circa'' 300 codices in 1407). With regard to the Greek codices, Bessarion's personal library was unrivaled in Western Europe. The Vatican collection, the second largest, included 414 Greek codices in 1455. See Zorzi, ''Biblioteca Marciana'', p. 20. The formal letter announcing the donation, dated 31 May 1468 and addressed to Doge Cristoforo Moro

Cristoforo Moro (1390 – November 10, 1471) was the 67th Doge of Venice. He reigned from 1462 to 1471.

Family

The Moro family settled in Venice in the 5th century when Stephanus Maurus, a great-grandson of Maurus, built a church on the island ...

() and the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, narrates that following the fall of Constantinople

The Fall of Constantinople, also known as the Conquest of Constantinople, was the capture of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottoman Empire. The city was captured on 29 May 1453 as part of the culmination of a 55-da ...

in 1453 and its devastation by the Turks

Turk or Turks may refer to:

Communities and ethnic groups

* Turkish people, or the Turks, a Turkic ethnic group and nation

* Turkish citizen, a citizen of the Republic of Turkey

* Turkic peoples, a collection of ethnic groups who speak Turkic lang ...

, Bessarion had set ardently about the task of acquiring the rare and important works of ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

and Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion () was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' continued to be used as a n ...

and adding them to his existing collection so as to prevent the further dispersal and total loss of Greek culture. The cardinal's stated desire in offering the manuscripts to Venice specifically was that they should be properly conserved in a city where many Greek refugees

Greek refugees is a collective term used to refer to the more than one million Greek Orthodox natives of Asia Minor, Thrace and the Black Sea areas who fled during the Greek genocide (1914-1923) and Greece's later defeat in the Greco-Turkish W ...

had fled and which he himself had come to consider "another Byzantium" ().The formal letter announcing the donation is preserved in Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana ms Lat. XIV, 14 (=4235) and ion-line

at . The documents relative to the donation are transcribed in Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., pp. 147–156.The legal act of donation preceded the formal announcement and is dated 14 May 1468. See Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., p. 27, 153–156 and Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., p. 82. Bessarion's first contact with Venice had been in 1438 when, as the newly ordained metropolitan bishop of Nicaea, he arrived with the Byzantine delegation to the Council of Ferrara-Florence, the objective being to heal the

schism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

between the Catholic and Orthodox churches and unite Christendom

The terms Christendom or Christian world commonly refer to the global Christian community, Christian states, Christian-majority countries or countries in which Christianity is dominant or prevails.SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christen ...

against the Ottoman Turks. His travels as envoy to Germany for Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II (, ), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini (; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 August 1458 to his death in 1464.

Aeneas Silvius was an author, diplomat, ...

brought him briefly to the city again in 1460 and 1461.For a detailed discussion of Bessarion's legation to Germany and the attempts to raise troops for a crusade, see Kenneth M. Setton, ''The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), vol. II, The Fifteenth Century'' (Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society, 1978), pp. 213–218, . On 20 December 1461, during the second stayover, he was admitted into the Venetian aristocracy with a seat in the Great Council.The deliberation of the Great Council is in the State Archives of Venice in ''Grazie Maggior Consiglio'', fol. 75v (in ''Avogaria di Comun'', b. 168, fasc. 6).

In 1463, Bessarion returned to Venice as the

In 1463, Bessarion returned to Venice as the papal legate

300px, A woodcut showing Henry II of England greeting the Pope's legate.

A papal legate or apostolic legate (from the ancient Roman title '' legatus'') is a personal representative of the Pope to foreign nations, to some other part of the Catho ...

, tasked with negotiating the republic's participation in a crusade to liberate Constantinople from the Turks. For the duration of this extended sojourn (1463–1464), the cardinal lodged and studied in the Benedictine

The Benedictines, officially the Order of Saint Benedict (, abbreviated as O.S.B. or OSB), are a mainly contemplative monastic order of the Catholic Church for men and for women who follow the Rule of Saint Benedict. Initiated in 529, th ...

monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore

San Giorgio Maggiore () is one of the islands of Venice, northern Italy, lying east of the Giudecca and south of the main island group. The island, or more specifically its Palladian church, is an important landmark. It has been much painted, ...

, and it was to the monastery that he initially destined his Greek codices which were to be consigned after his death. But under the influence of the humanist Paolo Morosini and his cousin Pietro, the Venetian ambassador to Rome, Bessarion annulled the legal act of donation in 1467 with papal consent, citing the difficulty readers would have had in reaching the monastery, located on a separate island.The terms of Bessarion's original act of donation to the monastery of San Giorgio (untraced) are recorded in the papal bull

A papal bull is a type of public decree, letters patent, or charter issued by the pope of the Catholic Church. It is named after the leaden Seal (emblem), seal (''bulla (seal), bulla'') traditionally appended to authenticate it.

History

Papal ...

authorizing the revocation that Pope Paul II issued on 16 September 1467. The text of the bull is published in G. Nicoletti, 'Bolla di Paolo II ed istrumento di donazione fatta della propria libreria dal cardinale Bessarione ai procuratori di s. Marco', ''Archivio Storico Italiano'', Serie terza, Vol. 9, No. 2, 54 (1869), pp. 195–197. Also, abbreviated, in Pittoni, ''La libreria di san Marco'', pp. 14–15 (note 1). The following year, Bessarion announced instead his intention to bequeath his entire personal library, both the Greek and Latin codices, to the Republic of Venice with immediate effect.Marino Zorzi attributes the sense of urgency in Bessarion's donation to the conspiracy to assassinate Pope Paul II

Pope Paul II (; ; 23 February 1417 – 26 July 1471), born Pietro Barbo, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 August 1464 to his death in 1471. When his maternal uncle became Pope Eugene IV, Barbo switched fr ...

in February 1468 and the resulting arrest, imprisonment, and torture of several noted Roman humanists, members of the Academy of Julius Pomponius Laetus

Julius Pomponius Laetus (1428 – 9 June 1498), also known as Giulio Pomponio Leto, was an Italian humanist.

Background

Laetus was born at Teggiano, near Salerno, the illegitimate scion of the princely house of Sanseverino, the German historian ...

, who were largely associated with Bessarion's own intellectual circle. There were additional charges of heresy that reflected the pope's deep aversion to Platonism

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary Platonists do not necessarily accept all doctrines of Plato. Platonism has had a profound effect on Western thought. At the most fundam ...

, secular poetry, rhetoric, and astrology. Zorzi argues that in this climate of suspicion and repression, Bessarion would have been anxious to quickly remove his library to safety, outside the territory of the Papal States. See Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., pp. 80–82. For a detailed discussion of the assassination plot against Paul II, see Anthony F. D'Elia, ''A Sudden Terror: The Plot to Murder the Pope in Renaissance Rome'' (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009) . For Paul II's relationship with Humanism, see A. J. Dunston, 'Pope Paul II and the Humanists', ''Journal of Religious History'', 7 (1983), pp. 287–306 .

On 28 June 1468, Pietro Morosini took legal possession of Bessarion's library in Rome on behalf of the republic. The bequest included the 466 codices which were transported to Venice in crates the next year.The full inventory is published in Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., pp. 157–188.In the preliminary letter of acceptance, the Senate valued the manuscripts at 15,000 ducat

The ducat ( ) coin was used as a trade coin in Europe from the later Middle Ages to the 19th century. Its most familiar version, the gold ducat or sequin containing around of 98.6% fine gold, originated in Venice in 1284 and gained wide inter ...

s. The letter, dated 23 March 1468, is published in Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., p. 124. For Bartolomeo Platina

Bartolomeo Sacchi (; 1421 – 21 September 1481), known as il Platina () after his birthplace of Piadena, was an Italian Renaissance humanist writer and gastronomist, author of what is considered the first printed cookbook.

Platina star ...

, Bessarion's precious codices had cost 30,000 golden scudo. See Bartolomeo Platina, ''Panegyricus in Bessarionem doctiss. partriarcham Constantin'' (Colonia: Eucharius Cervicornus

Saint Eucharius is venerated as the first bishop of Trier. He lived in the second half of the 3rd century.

Narrative

According to an ancient legend, he was one of the seventy-two disciples of Christ, and was sent to Gaul by Saint Peter as bi ...

, 1529) p. Regardless of the differing figures, the value was considerable: from several contemporary contracts, a well-paid professor earned 120 ducats a year. See Zorzi, ''La Libreria di San Marco''..., p. 60. To this initial delivery, more codices and ''incunabula

An incunable or incunabulum (: incunables or incunabula, respectively) is a book, pamphlet, or broadside (printing), broadside that was printed in the earliest stages of printing in Europe, up to the year 1500. The specific date is essentiall ...

'' were added following the death of Bessarion in 1472. This second shipment, arranged in 1474 by Federico da Montefeltro

Federico da Montefeltro, also known as Federico III da Montefeltro Order of the Garter, KG (7 June 1422 – 10 September 1482), was one of the most successful mercenary captains (''condottiero, condottieri'') of the Italian Renaissance, and Duk ...

, departed from Urbino, where Bessarion had deposited the remainder of his library for safekeeping. It included the books that the cardinal had reserved for himself or had acquired after 1468.

Despite the grateful acceptance of the donation by the Venetian government and the commitment to establish a library of public utility, the codices remained crated inside the Doge's Palace

The Doge's Palace (''Doge'' pronounced ; ; ) is a palace built in Venetian Gothic architecture, Venetian Gothic style, and one of the main landmarks of the city of Venice in northern Italy. The palace included government offices, a jail, and th ...

, entrusted to the care of the state historian under the direction of the procurators of Saint Mark ''de supra''. Little was done to facilitate access, particularly during the years of the conflict against the Ottomans (1463–1479) when time and resources were directed towards the war effort. In 1485, the need to provide greater space for governmental activities led to the decision to compress the crates into a smaller area of the palace where they were stacked, one atop the other. Access became more difficult and on-site consultation impracticable. Although codices were periodically loaned, primarily to learned members of the Venetian nobility and academics, the requirement to deposit a security was not always enforced.Bessarion stipulated in the act of donation that the codices were to be available for loan, with the requirement that a security be deposited in the amount of twice the value of the codex. See Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., p. 83. A few of the codices were subsequently discovered in private libraries or even for sale in local book shops. In exceptional circumstances, copyists were allowed to duplicate the manuscripts for the private libraries of influential patrons: among others Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

commissioned copies of seven Greek codices. During this period, reproduction of the manuscripts was rarely authorized for printers who needed working copies on which to write notes and make corrections whenever printing critical editions, since it was believed that the value of a manuscript would greatly decline once the ''editio princeps

In Textual scholarship, textual and classical scholarship, the ''editio princeps'' (plural: ''editiones principes'') of a work is the first printed edition of the work, that previously had existed only in manuscripts. These had to be copied by han ...

'' (first edition) had been published.Senator Domenico Malipiero objected to expenditures for the construction of the library on the basis that the codices would have little value once the texts had been printed. This opinion persisted. In 1541, the Avogador Bernardo Zorzi criticized the ease with which copies were made on the grounds that they diminished the value and importance of the originals. Aldus Manutius himself wrote that the examples given to printers were destined to be torn up. See Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., pp. 92–93. Notably, Aldus Manutius

Aldus Pius Manutius (; ; 6 February 1515) was an Italian printer and Renaissance humanism, humanist who founded the Aldine Press. Manutius devoted the later part of his life to publishing and disseminating rare texts. His interest in and preser ...

was able to make only limited use of the codices for his publishing house

Publishing is the activities of making information, literature, music, software, and other content, physical or digital, available to the public for sale or free of charge. Traditionally, the term publishing refers to the creation and distribu ...

.The Aldine editions of Xenophon

Xenophon of Athens (; ; 355/354 BC) was a Greek military leader, philosopher, and historian. At the age of 30, he was elected as one of the leaders of the retreating Ancient Greek mercenaries, Greek mercenaries, the Ten Thousand, who had been ...

's ''Hellenica

''Hellenica'' () simply means writings on Greek (Hellenic) subjects. Several histories of the 4th-century BC Greece have borne the conventional Latin title ''Hellenica'', of which very few survive.Murray, Oswyn, "Greek Historians", in John Boardma ...

'' (1502) and Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

's ''Moralia

The ''Moralia'' (Latin for "Morals", "Customs" or "Mores"; , ''Ethiká'') is a set of essays ascribed to the 1st-century scholar Plutarch of Chaeronea. The eclectic collection contains 78 essays and transcribed speeches. They provide insigh ...

'' (1509) were based on Bessarion's codices. The manuscripts were also consulted for the works by Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

published between 1495 and 1498. See Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco''..., p. 93

Several prominent humanists, including Marcantonio Sabellico in his capacity as official historian and Bartolomeo d'Alviano

Bartolomeo d'Alviano (c. 1455 – October 1515) was an Italian condottiero and captain who distinguished himself in the defence of the Venetian Republic against the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, Maximilian.

Biography

Barto ...

, urged the government over time to provide a more suitable location, but to no avail. The political and financial situation during the long years of the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

stymied any serious plan to do so, notwithstanding the Senate's statement of intent in 1515 to build a library. Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., p. 18The deliberation of the Senate appropriated no funding and was without effect. It nevertheless constitutes the first proposal to construct a library rather than to simply find a suitable location for the collection. The deliberation of the Senate, dated 5 May 1515, is published in Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., pp. 130–131. Access to the collection itself was nevertheless improved after the appointment of Andrea Navagero

Andrea Navagero (1483 – 8 May 1529), known as Andreas Naugerius in Latin, was a Venetian diplomat and writer. Born to a wealthy family, he gained entry to the Great Council of Venice at the age of twenty, five years younger than was normal at ...

as official historian and ''gubernator'' (curator) of the collection. During Navagero's tenure (1516–1524), scholars made greater use of the manuscripts and copyists were authorized with more frequency to reproduce codices for esteemed patrons, including Pope Leo X

Pope Leo X (; born Giovanni di Lorenzo de' Medici, 11 December 14751 December 1521) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 9 March 1513 to his death in December 1521.

Born into the prominent political and banking Med ...

, King Francis I

Francis I (; ; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis&nbs ...

of France, and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; – 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal (catholic), cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's Lord High Almoner, almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and ...

, Lord High Chancellor of England. More editions of the manuscripts were published in this period, notably by Manutius' heirs. With the nomination of Pietro Bembo

Pietro Bembo, (; 20 May 1470 – 18 January 1547) was a Venetian scholar, poet, and literary theory, literary theorist who also was a member of the Knights Hospitaller and a cardinal of the Catholic Church. As an intellectual of the Italian Re ...

as ''gubernator'' in 1530 and the termination of the War of the League of Cognac

The War of the League of Cognac (1526–1530) was fought between the Habsburg dominions of Charles V—primarily the Holy Roman Empire and Spain—and the League of Cognac, an alliance including the Kingdom of France, Pope Clement VII, the Re ...

in that same year, efforts to gather support for the construction of the library were renewed. Probably at the instigation of Bembo, an enthusiast of classical studies, the collection was transferred in 1532 to the upper floor of the Church of Saint Mark, the ducal chapel, where the codices were uncrated and placed on shelves. That same year, Vettore Grimani pressed his fellow procurators, insisting that the time had come to act on the republic's long-standing intention to construct a public library wherein Bessarion's codices could be housed.The record of the procurators’ proceedings is published in Labowsky, ''Bessarion's Library''..., p. 132.

Building

Construction

The construction of the library was an integral part of the (renewal of the city), a vast architectural programme begun under Doge

The construction of the library was an integral part of the (renewal of the city), a vast architectural programme begun under Doge Andrea Gritti

Andrea Gritti (17 April 1455 – 28 December 1538) was the Doge of the Venetian Republic from 1523 to 1538, following a distinguished diplomatic and military career. He started out as a successful merchant in Constantinople and transitioned into ...

(). The programme was intended to heighten Venetian self-confidence and reaffirm the republic's international prestige after the earlier defeat at Agnadello during the War of Cambrai and the subsequent Peace of Bologna, which sanctioned Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

hegemony on the Italian peninsula at the end of the War of the League of Cognac. Championed by the Grimani

The House of Grimani was a prominent Venetian patrician family, including three Doges of Venice. They were active in trade, politics and later the ownership of theatres and opera-houses.

Notable members

Notable members included:

* Antonio Grim ...

family, it called for the transformation of Saint Mark's Square from a medieval town centre with food vendors, money changers, and even latrines into a classical forum. The intent was to evoke the memory of the ancient Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and, in the aftermath of the Sack of Rome in 1527, to present Venice as Rome's true successor. This would visually substantiate Venetian claims that, despite the republic's relative loss of political influence, its longevity and stability were assured by its constitutional structure, consisting in a mixed government

Mixed government (or a mixed constitution) is a form of government that combines elements of democracy, aristocracy and monarchy, ostensibly making impossible their respective degenerations which are conceived in Aristotle's ''Politics'' as a ...

modelled along the lines of the classical republics.The customary interpretation of Venice as an example of the mixed government was that the monarchical element was identifiable in the doge, the aristocratic element in the Senate, and the democratic element in the Great Council. See John G. A. Pocock, ''The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), pp. 311–312.

Monumental in scale, the architectural programme was one of the most ambitious projects of urban renewal in sixteenth-century Italy. In addition to the mint

Mint or The Mint may refer to:

Plants

* Lamiaceae, the mint family

** ''Mentha'', the genus of plants commonly known as "mint"

Coins and collectibles

* Mint (facility), a facility for manufacturing coins

* Mint condition, a state of like-new ...

(begun 1536) and the loggia

In architecture, a loggia ( , usually , ) is a covered exterior Long gallery, gallery or corridor, often on an upper level, sometimes on the ground level of a building. The corridor is open to the elements because its outer wall is only parti ...

of the bell tower of Saint Mark's (begun 1538), it involved replacing the dilapidated thirteenth-century buildings that lined the southern side of the square and the area in front of the Doge's Palace. For this, the procurators of Saint Mark ''de supra'' commissioned Jacopo Sansovino

Jacopo d'Antonio Sansovino (2 July 1486 – 27 November 1570) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor and architect, best known for his works around the Piazza San Marco in Venice. These are crucial works in the history of Venetian Renaissance arc ...

, their ''proto'' (consultant architect and buildings manager), on 14 July 1536. Howard, ''The Architectural History of Venice'', p. 147 Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco...'', p. 127 A refugee from the Sack of Rome, Sansovino possessed the direct knowledge and understanding of ancient Roman prototypes necessary to carry out the architectural programme.

The commission called for a model of a three-storey building, but the project was radically transformed. On 6 March 1537, it was decided that the construction of the new building, now with only two storeys, would be limited to the section directly in front of the palace and that the upper floor was to be reserved for the offices of the procurators and the library.The deliberation of the procurators is in the State Archives of Venice (PS, Atti, reg. 125, c. 2) and is published in Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., p. 163. This would not only satisfy the terms of the donation, it would bring renown to the republic as a centre of wisdom, learning, and culture. Significantly, the earlier decree of 1515, citing as examples the libraries in Rome and in Athens, expressly stated that a perfect library with fine books would serve as an ornament for the city and as a light for all of Italy.Fragmentary descriptions of ancient libraries survive in classical literary sources. See Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., pp. 26 (notes 99 and 100 for bibliographical references). It has been suggested that specifically Pausanias' description of Hadrian's Library

Hadrian's Library was a monumental building created by Roman Emperor Hadrian in AD 132 on the north side of the Acropolis of Athens.

The main entrance to the library was part of the Stoa of Hadrian with columns of Karystian marble and Pentelic ...

in Athens may have served as an architectural prototype for the Marciana Library in consideration of the columns and gilded ceiling. The orientation of the library with the reading room facing east may have been influenced by Vitruvius' recommendation in ''De architectura'' (VI,4,1). See Hartt, ''History of Italian Renaissance Art'', p. 633.

Sansovino's superintendence (1537–)

Construction proceeded slowly. The chosen site for the library, although owned by the government, was occupied by five hostelries (Pellegrino, Rizza, Cavaletto, Luna, Lion) and several food stalls, many of which had long-standing contractual rights. It was thus necessary to find a mutually agreed upon alternative location, and at least three of the hostelries had to remain in the area of Saint Mark's Square. Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., p. 19 In addition, the hostelries and shops provided a steady flow of rental income to the procurators of Saint Mark ''de supra'', the magistrates responsible for the public buildings around Saint Mark's Square. So there was the need to limit the disruption of the revenue by gradually relocating the activities as the building progressed and new space was required to continue. The lean-to bread shops and a portion of the Pellegrino hostelry adjoining the bell tower were demolished in early 1537. But rather than reutilizing the existing foundations, Sansovino built the library detached so as to make the bell tower a freestanding structure and transform Saint Mark's Square into atrapezoid

In geometry, a trapezoid () in North American English, or trapezium () in British English, is a quadrilateral that has at least one pair of parallel sides.

The parallel sides are called the ''bases'' of the trapezoid. The other two sides are ...

. This was intended to give greater visual importance to the Church of Saint Mark located on the eastern side.

Work was suspended following the

Work was suspended following the Ottoman–Venetian War (1537–1540)

The Third Ottoman Venetian War (1537–1540) was one of the Ottoman–Venetian wars which took place during the 16th century. The war arose out of the Franco-Ottoman alliance between Francis I of France and Süleyman I of the Ottoman Empi ...

due to lack of funding but resumed in 1543. The next year, 1544, the rest of the Pellegrino hostelry was torn down, followed by the Rizza. On 18 December 1545, the heavy masonry vault collapsed. In the subsequent enquiry, Sansovino claimed that workmen had prematurely removed the temporary wooden supports before the concrete had set and that a galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

in the basin of Saint Mark, firing her cannon as a salute, had shaken the building. Nevertheless, the architect was sentenced to personally repay the cost of the damage, which took him 20 years. Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., p. 21In 1565, the procurators discharged the remaining debt in exchange for sculptural work by Sansovino. The deliberation of the procurators, dated 20 March 1565, is in the State Archives of Venice (PS, Atti, reg. 130, c. 72). See Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino...'', p. 21. Further, his stipend was suspended until 1547. As a consequence of the collapse, the design was modified with a lighter wooden structure to support the roof.

In the following years, the procurators increased funding by borrowing from trust funds, recovering unpaid rents, selling unprofitable holdings, and drawing upon the interest income from government bonds. Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., pp. 21, 23 Work proceeded rapidly thereafter. The Cavaletto hostelry was relocated in 1550. This was followed by the demolition of the Luna. By 1552, at least the seven bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a ''gulf'', ''sea'', ''sound'', or ''bight''. A ''cove'' is a small, ci ...

s in correspondence to the reading room, had been completed.In 1552, the practice began of extracting by lot the use of the balconies by the procurators and their guests to observe the carnival celebrations in the Piazzetta. That year, seven balconies were awarded. See Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino''..., p. 21 and Morresi, ''Jacopo Sansovino'', p. 202. The commemorative plaque in the adjacent vestibule, corresponding to the next three bays, bears the date of the Venetian year 1133 (''i.e.'' 1554),The Venetian year was calculated beginning with AD 421, the legendary year of the city's foundation on 25 March. See Edward Muir, ''Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice'' (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981), pp. 70–72. an indication that the end of construction was already considered imminent. By then, fourteen bays had been constructed. However, owing to difficulties in finding a suitable alternative location, only in 1556 was the last of the hostelries, the Lion, relocated, allowing the building to reach the sixteenth bay in correspondence with the lateral entry of the mint. Beyond stood the central meat market. This was a significant source of rental income for the procurators, and construction was halted. The work on the interior decorations continued until about 1560. Although it was decided five years later to relocate the meat market and continue the building, Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco...'', p. 135 no further action was taken, and in 1570 Sansovino died.

Scamozzi's superintendence (1582–1588)

The meat market was demolished in 1581. The following yearVincenzo Scamozzi

Vincenzo Scamozzi (2 September 1548 – 7 August 1616) was an Italians, Italian architect and a writer on architecture, active mainly in Vicenza and Republic of Venice area in the second half of the 16th century. He was perhaps the most importan ...

was selected to oversee the construction of the final five bays, continuing Sansovino's design for the façade. This brought the building down to the embankment of Saint Mark's Basin and into alignment with the main façade of the mint. Scamozzi added the crowning statues and obelisks. Zorzi, ''La libreria di san Marco...'', p. 136Only one statue had been placed during Sansovino's superintendence. See Ivanoff, 'La libreria marciana...', p. 8. Since the original plans by Sansovino do not survive, it is not known whether the architect intended for the library to reach the final length of twenty-one bays. Scamozzi's negative comment on the junction of the library with the mint has led some architectural historians to argue that the result could not have been intentionally designed by Sansovino.Scamozzi criticizes the truncating of cornices, bases, and capitals in reference to the junction of the facades of the library and the mint and considers such solutions "indecencies and follies" (''"indecentie e sciocchezze"''). See Vincenzo Scamozzi, ''L'idea della architettura universale di Vincenzo Scamozzi architetto veneto'' (Venetiis: Giorgio Valentini, 1615), Parte seconda, p. 171. However archival research and technical and aesthetic assessments have not been conclusive.The issue is summarized in Deborah Howard, 'The Length of the Library', ''Ateneo veneto'', Anno CXCVII, terza serie, 9/11 (2010), pp. 23–29, .

During Scamozzi's superintendence, the debate regarding the height of the building was reopened. When Sansovino was first commissioned on 14 July 1536, the project expressly called for a three-storey construction similar to the recently rebuilt Procuratie Vecchie

The Procuratie (English: Procuracies) are three connected buildings along the perimeter of Saint Mark's Square in Venice, Italy. Two of the buildings, the Procuratie Vecchie (Old Procuracies) and the Procuratie Nuove (New Procuracies), were c ...

on the northern side of Saint Mark's Square. But by 6 March 1537, when the decision was made to locate the library within the new building, the plan was abandoned in favour of a single floor above the ground level.There are no surviving records regarding the debate, and it is not known what factors were determinative. See, Howard, ''Jacopo Sansovino...'', pp. 15–16. Scamozzi, nonetheless, recommended adding a floor to the library. Engineers were called to assess the existing foundation to determine whether it could bear the additional weight. The conclusions were equivocal, and it was ultimately decided in 1588 that the library would remain with only two floors.Manuela Morresi suggests that in addition to engineering considerations, the decision to retain the height of the library stemmed from the ascendency of the ''giovani'' faction in the aftermath of the constitutional crisis of 1582 and its opposition to the aggressive building programme. See Morresi, ''Jacopo Sansovino'', p. 207.

Architecture

Upper floor

The upper storey is characterized by a series of Serlians, so-called because the architectural element was illustrated and described bySebastiano Serlio

Sebastiano Serlio (6 September 1475 – c. 1554) was an Italian Mannerist architect, who was part of the Italian team building the Palace of Fontainebleau. Serlio helped canonize the classical orders of architecture in his influential treatise ...

in his ''Tutte l'opere d'architettura et prospetiva'', a seven-volume treatise for Renaissance architects and scholarly patrons. Later popularized by the architect Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

, the element is also known as the Palladian window. It is inspired by ancient triumphal arch

A triumphal arch is a free-standing monumental structure in the shape of an archway with one or more arched passageways, often designed to span a road, and usually standing alone, unconnected to other buildings. In its simplest form, a triumphal ...

es such as the Arch of Constantine

The Arch of Constantine () is a triumphal arch in Rome dedicated to the emperor Constantine the Great. The arch was commissioned by the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312 ...

and consists in a high-arched opening that is flanked by two shorter sidelight

A sidelight or sidelite in a building is a window, usually with a vertical emphasis, that flanks a door or a larger window. Sidelights are narrow, usually stationary and found immediately adjacent to doorways.Barr, Peter.Illustrated Glossary", ...

s topped with lintel

A lintel or lintol is a type of beam (a horizontal structural element) that spans openings such as portals, doors, windows and fireplaces. It can be a decorative architectural element, or a combined ornamented/structural item. In the case ...

s and supported by column

A column or pillar in architecture and structural engineering is a structural element that transmits, through compression, the weight of the structure above to other structural elements below. In other words, a column is a compression member ...

s. From his days in Florence, Sansovino was likely familiar with the Serlian, having observed it in the tabernacle of the Merchants' guild by Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), known mononymously as Donatello (; ), was an Italian Renaissance sculpture, Italian sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Republic of Florence, Florence, he studied classical sc ...

and Michelozzo

Michelozzo di Bartolomeo Michelozzi (; – 7 October 1472), known mononymously as Michelozzo, was an Italian architect and sculptor. Considered one of the great pioneers of architecture during the Renaissance, Michelozzo was a favored Medici ...

() on the façade of the Church of Orsanmichele

Orsanmichele or Orsammichele (; from the Tuscan contraction of ''Orto di San Michele'', "Kitchen Garden of St. Michael") is a church in the Italian city of Florence. The building was constructed on the site of the kitchen garden of the monaster ...

. He would have undoubtedly seen Donato Bramante

Donato Bramante (1444 – 11 April 1514), born as Donato di Pascuccio d'Antonio and also known as Bramante Lazzari, was an Italian architect and painter. He introduced Renaissance architecture to Milan and the High Renaissance style to Rom ...

's tripartite window in the Sala Regia of the Vatican during his Roman sojourn and may have been aware of the sixteenth-century nymphaeum

A ''nymphaeum'' (Latin : ''nymphaea'') or ''nymphaion'' (), in ancient Greece and Rome, was a monument consecrated to the nymphs, especially those of springs.

These monuments were originally natural grottoes, which tradition assigned as habit ...

at Genazzano near Rome, attributed to Bramante, where the Serlian is placed in a series. Lotz, 'The Roman Legacy in Sansovino's Venetian Buildings', p. 10The Serlian is placed in a series by Giulio Romano

Giulio Pippi ( – 1 November 1546), known as Giulio Romano and Jules Romain ( , ; ), was an Italian Renaissance painter and architect. He was a pupil of Raphael, and his stylistic deviations from High Renaissance classicism help define the ...

for the riverfront façade of Villa Turini-Lante. See Morresi, ''Jacopo Sansovino'', p. 193 At the Marciana, Sansovino adopted the contracted Serlian of the Orsanmichele prototype, which has narrow sidelights, but these are separated from the tall opening by double columns, placed one behind the other. This solution of the narrow sidelights ensured greater strength to the structural walls, which was necessary to balance the thrust of the barrel vault

A barrel vault, also known as a tunnel vault, wagon vault or wagonhead vault, is an architectural element formed by the extrusion of a single curve (or pair of curves, in the case of a pointed barrel vault) along a given distance. The curves are ...

originally planned for the upper storey.

Layered over the series of Serlians is a row of large Ionic columns

The Ionic order is one of the three canonic orders of classical architecture, the other two being the Doric and the Corinthian. There are two lesser orders: the Tuscan (a plainer Doric), and the rich variant of Corinthian called the composite ...

. The capital

Capital and its variations may refer to:

Common uses

* Capital city, a municipality of primary status

** Capital region, a metropolitan region containing the capital

** List of national capitals

* Capital letter, an upper-case letter

Econom ...

s with the egg-and-dart

Egg-and-dart, also known as egg-and-tongue, egg-and-anchor, or egg-and-star, is an Ornament (architecture), ornamental device adorning the fundamental quarter-round, convex ovolo profile of molding (decorative), moulding, consisting of alternating ...

motif in the echinus and flame palmette

The flame palmette is a motif in decorative art which, in its most characteristic expression, resembles the fan-shaped leaves of a palm tree. Flame palmettes are different from regular palmettes in that, traditionally palmettes tended to have shar ...

s and masks in the collar may have been directly inspired by the Temple of Saturn

The Temple of Saturn (Latin: ''Templum Saturni'' or '' Aedes Saturni''; ) was an ancient Roman temple to the god Saturn, in what is now Rome, Italy. Its ruins stand at the foot of the Capitoline Hill at the western end of the Roman Forum. Th ...

in Rome and perhaps by the Villa Medicea at Poggio a Caiano by Giuliano da Sangallo

Giuliano da Sangallo (c. 1445 – 1516) was an Italian sculptor, architect and military engineer active during the Italian Renaissance. He is known primarily for being the favored architect of Lorenzo de' Medici, his patron. In this role, Giuli ...

. Morresi, ''Jacopo Sansovino'', pp. 193–194 For the bases, as a sign of his architectural erudition, Sansovino adopted the Ionic base as it had been directly observed and noted by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger

Antonio da Sangallo the Younger (12 April 14843 August 1546), also known as Antonio Cordiani, was an Italian architect active during the Renaissance, mainly in Rome and the Papal States. One of his most popular projects that he worked on des ...

and Baldassare Peruzzi

Baldassare Tommaso Peruzzi (7 March 1481 – 6 January 1536) was an Italian architect and painter, born in a small town near Siena (in Ancaiano, ''frazione'' of Sovicille) and died in Rome. He worked for many years with Bramante, Raphael, and l ...

in ancient ruins at Frascati.This Ionic base, utilized once by Palladio for Palazzo Porto

Palazzo Porto is a palace built by Italian Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio in Contrà Porti, Vicenza, Italy. It is one of two palaces in the city designed by Palladio for members of the Porto family (the other being Palazzo Porto in Piazza ...

in Vicenza, is believed to have been part of the Villa of Lucullus at Frascati. See Maria Barbara Guerrieri Borsoi, ''Villa Rufina Falconieri: la rinascita di Frascati e la più antica dimora tuscolana'' (Roma: Gangemi, 2008), p. 13, . For a discussion and comparison with the Attic and Vitruvian bases for the Ionic order, see Howard Burns, '"Ornamenti" and ornamentation in Palladio's architectural theory and practice', ''Pegasus: Berliner Beiträge zum Nachleben der Antike'', 11 (2009), pp. 49–50, . The idea of an ornate frieze

In classical architecture, the frieze is the wide central section of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic order, Ionic or Corinthian order, Corinthian orders, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Patera (architecture), Paterae are also ...

above the columns with festoon

A festoon (from French ''feston'', Italian ''festone'', from a Late Latin ''festo'', originally a festal garland, Latin ''festum'', feast) is a wreath or garland hanging from two points, and in architecture typically a carved ornament depicti ...

s alternating with window openings had already been used by Sansovino for the courtyard of Palazzo Gaddi in Rome (1519–1527). But the insertion of windows into a frieze had been pioneered even earlier by Bramante at Palazzo Caprini

Palazzo Caprini was a Renaissance palazzo in Rome, Italy, in the Borgo rione between Piazza Scossacavalli and via Alessandrina (also named Borgo Nuovo). It was designed by Donato Bramante around 1510, or a few years before.

It was also kno ...

in Rome (1501–1510, demolished 1938) and employed in Peruzzi's early sixteenth-century Villa Farnesina

The Villa Farnesina is a Renaissance suburban villa in the Via della Lungara, in the district of Trastevere in Rome, central Italy. Built between 1506 and 1510 for Agostino Chigi, the Pope's wealthy Sienese banker, it was a novel type of suburb ...

. In the library, the specific pattern of the festoons with ''putti

A putto (; plural putti ) is a figure in a work of art depicted as a chubby male child, usually naked and very often winged. Originally limited to profane passions in symbolism,Dempsey, Charles. ''Inventing the Renaissance Putto''. University ...

'' appears to be based on an early second-century sarcophagus fragment belonging to Cardinal Domenico Grimani

Domenico Grimani (22 February 1461 – 27 August 1523) was an Italian nobleman, theologian and cardinal. Like most noble churchman of his era Grimani was an ecclesiastical pluralist, holding numerous posts and benefices.

Biography

Born in V ...

's collection of antiquities

Antiquities are objects from antiquity, especially the civilizations of the Mediterranean such as the Classical antiquity of Greece and Rome, Ancient Egypt, and the other Ancient Near Eastern cultures such as Ancient Persia (Iran). Artifact ...

.The fragment showing the rape of Proserpina is in the ''Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Venezia'', inv. 167. See also Antonio Foscari, 'Festoni e putti nella decorazione della Libreria di San Marco', ''Arte veneta'', XXXVIII (1984), pp. 23–30.

Ground floor

The ground floor is modelled on theTheatre of Marcellus

The Theatre of Marcellus (, ) was an ancient open-air theatre in Rome, Italy, built in the closing years of the Roman Republic. It is located in the modern rione of Sant'Angelo. In the sixteenth century, it was converted into a palazzo.

Construc ...

and the Colosseum

The Colosseum ( ; , ultimately from Ancient Greek word "kolossos" meaning a large statue or giant) is an Ellipse, elliptical amphitheatre in the centre of the city of Rome, Italy, just east of the Roman Forum. It is the largest ancient amphi ...

in Rome. It consists in a succession of Doric columns

The Doric order is one of the three orders of ancient Greek and later Roman architecture; the other two canonical orders were the Ionic and the Corinthian. The Doric is most easily recognized by the simple circular capitals at the top of t ...

supporting an entablature

An entablature (; nativization of Italian , from "in" and "table") is the superstructure of moldings and bands which lies horizontally above columns, resting on their capitals. Entablatures are major elements of classical architecture, and ...

and is layered over a series of arches resting on pillars. The combination of columns layered over an arcade

Arcade most often refers to:

* Arcade game, a coin-operated video, pinball, electro-mechanical, redemption, etc., game

** Arcade video game, a coin-operated video game

** Arcade cabinet, housing which holds an arcade video game's hardware

** Arcad ...

had been proposed by Bramante for the Palazzo di Giustizia (unexecuted), and was employed by Antonio da Sangallo the younger for the courtyard of Palazzo Farnese

Palazzo Farnese () or Farnese Palace is one of the most important High Renaissance palaces in Rome. Owned by the Italian Republic, it was given to the French government in 1936 for a period of 99 years, and currently serves as the French e ...

(begun 1517).The motif was earlier proposed by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger for Palazzo Farnese and may have been intended for the Church of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome. See, Lotz, 'The Roman Legacy in Sansovino's Venetian Buildings', pp. 8–9. In adopting the solution for the Marciana Library, Sansovino was faithfully adhering to the recommendation of Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, Catholic priest, priest, linguistics, linguist, philosopher, and cryptography, cryptographer; he epitomised the natu ...

that in larger structures the column, inherited from Greek architecture, should only support an entablature, whereas the arch, inherited from Roman mural construction, should be supported on square pillars so that the resulting arcade appears to be the residual of "a wall open and discontinued in several places".

According to the architect's son, Francesco

Francesco, the Italian language, Italian (and original) version of the personal name "Francis (given name), Francis", is one of the List of most popular given names, most common given name among males in Italy. Notable persons with that name inclu ...

, Sansovino's design for the corner of the Doric frieze was much discussed and admired for its faithful adherence to the principles of Ancient Roman architecture

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical ancient Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often consi ...

as outlined by Vitruvius

Vitruvius ( ; ; –70 BC – after ) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work titled . As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissan ...

in ''De architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Ancient Rome, Roman architect and military engineer Vitruvius, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesa ...

''. These principles required that a triglyph

Triglyph is an architectural term for the vertically channeled tablets of the Doric frieze in classical architecture, so called because of the angular channels in them. The rectangular recessed spaces between the triglyphs on a Doric frieze are ...

be centred over the last column and then followed by half a metope

A metope (; ) is a rectangular architectural element of the Doric order, filling the space between triglyphs in a frieze

, a decorative band above an architrave.

In earlier wooden buildings the spaces between triglyphs were first open, and ...

, but the space was insufficient. With no surviving classical examples to guide them, Bramante, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), now generally known in English as Raphael ( , ), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. List of paintings by Raphael, His work is admired for its cl ...

, and other great Renaissance architects had struggled with the dilemma, implementing various ideas, none of which satisfied the Vitruvian dictum.Bramante's solution for the choir of Saint Peter's consisted in placing a metope, and not a triglyph, over the lesene

A lesene, also called a pilaster strip, is an architectural term for a narrow, low-relief vertical pillar on a wall. It resembles a pilaster, but does not have a base or capital. It is typical in Lombardic and Rijnlandish architectural building ...

s. This solution, highly criticized by in his treatise ''In decem libros M. Vitruvii'' (Lyons: Jean de Tournes, 1552), was adopted by Antonio da Sangallo for Palazzo Baldassini

Palazzo Baldassini is a palace in Rome, Italy, designed by the Renaissance architect Antonio da Sangallo the YoungerM. Cogotti, L. Gigli, ''Palazzo Baldassini'', L'erma di Bretschneider, 1995 in about 1516–1519. It was designed for the papal ju ...

and by Raphael for Palazzo Jacopo da Brescia. Giuliano da Sangallo's rendition of the Basilica Aemilia

The Basilica Aemilia (), or the Basilica Paulli, was a civil basilica in the Roman Forum. Lucius Aemilius Paullus initiated its construction, but the building was completed by his son, Paullus Aemilius Lepidus, in 34 BCE. Under Augustus, it was ...

shows the triglyph off-centered with respect to the pilaster. The same architect proposed two solutions for the design of San Lorenzo in Florence: an angular triglyph or an axial triglyph followed by a reduced metope. See Morresi, ''Jacopo Sansovino'', pp. 451–453 (note 139 for bibliographical references). Sansovino's solution was to lengthen the end of the frieze by placing a final pilaster

In architecture, a pilaster is both a load-bearing section of thickened wall or column integrated into a wall, and a purely decorative element in classical architecture which gives the appearance of a supporting column and articulates an ext ...

on a wider pier

A pier is a raised structure that rises above a body of water and usually juts out from its shore, typically supported by piling, piles or column, pillars, and provides above-water access to offshore areas. Frequent pier uses include fishing, b ...

, thus creating the space necessary for a perfect half metope.Lotz suggests that the inspiration may have been the corner pier in Santa Maria presso San Biaggio in Montepulciano which lacks, however, the corner metope. See Lotz, 'The Roman Legacy in Sansovino's Venetian Buildings', p. 9. Francesco Sansovino relates that his father additionally sensationalized the design by challenging the leading architects in Italy to resolve the problem and then triumphantly revealing his own solution.

Carvings

Rather than a two-dimensional wall, the façade is conceived as an assemblage of three-dimensional structural elements, including piers, arcades, columns, and entablatures layered atop one another to create a sense of depth, which is increased by the extensive surface carvings. These are the work of Sansovino's collaborators, includingDanese Cattaneo

Danese Cattaneo (? – 1572) was an Italian sculptor and medallist, active mainly in the Veneto region of Italy.

Danese was Tuscan in origin, born in either Massa di Carrara or Colonnata. He produced primarily sculptures of religious and histo ...

, Pietro da Salò, Bartolomeo Ammannati

Bartolomeo Ammannati (18 June 1511 – 13 April 1592) was an Italian architect and sculptor, born at Settignano, near Florence, Italy. He studied under Baccio Bandinelli and Jacopo Sansovino (assisting on the design of the Library of St. Mark ...

, and Alessandro Vittoria

Alessandro Vittoria funerary monument, San Zaccaria, Venice

Alessandro Vittoria (1525 – 27 May 1608) was an Italian Mannerist sculptor of the Venetian school, "one of the main representatives of the Venetian classical style" and rivalling ...

. Male figures in high relief

High may refer to:

Science and technology

* Height

* High (atmospheric), a high-pressure area

* High (computability), a quality of a Turing degree, in computability theory

* High (tectonics), in geology an area where relative tectonic uplift t ...

are located in the spandrel

A spandrel is a roughly triangular space, usually found in pairs, between the top of an arch and a rectangular frame, between the tops of two adjacent arches, or one of the four spaces between a circle within a square. They are frequently fil ...

s on the ground floor. With the exception of the arch in correspondence to the entry of the library which has Neptune

Neptune is the eighth and farthest known planet from the Sun. It is the List of Solar System objects by size, fourth-largest planet in the Solar System by diameter, the third-most-massive planet, and the densest giant planet. It is 17 t ...

holding a trident and Aeolus

In Greek mythology, Aiolos, transcribed as Aeolus (; ; ) refers to three characters. These three are often difficult to tell apart, and even the ancient mythographers appear to have been perplexed about which Aeolus was which. Diodorus Siculus m ...