Sailing BoatVCG on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sailing employs the wind—acting on

The earliest image suggesting the use of sail on a boat may be on a piece of pottery from

The earliest image suggesting the use of sail on a boat may be on a piece of pottery from

In the early 1800s, fast blockade-running schooners and brigantines—

In the early 1800s, fast blockade-running schooners and brigantines—

While the use of sailing vessels for commerce or naval power has been supplanted with engine-driven vessels, there continue to be commercial operations that take passengers on sailing cruises. Modern navies also employ sailing vessels to train cadets in

While the use of sailing vessels for commerce or naval power has been supplanted with engine-driven vessels, there continue to be commercial operations that take passengers on sailing cruises. Modern navies also employ sailing vessels to train cadets in

File:Shrike-port-beam.jpg, ''Close-hauled'': the flag is streaming backwards, the sails are sheeted in tightly.

File:Shrike-reaching.jpg, ''Reaching'': the flag is streaming slightly to the side as the sails are sheeted to align with the apparent wind.

File:Shrike-running.jpg, ''Running'': the wind is coming from behind the vessel; the sails are "wing on wing" to be at right angles to the apparent wind.

File:Forces on sails for three points of sail.jpg, Apparent wind and forces on a ''sailboat''.

As the boat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind becomes smaller and the lateral component becomes less; boat speed is highest on the beam reach. File:Ice boat apparent wind on different points of sail.jpg, Apparent wind on an ''iceboat''.

As the iceboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind increases slightly and the boat speed is highest on the broad reach. The sail is sheeted in for all three points of sail.

The speed of sailboats through the water is limited by the resistance that results from hull drag in the water. Ice boats typically have the least resistance to forward motion of any sailing craft. Consequently, a sailboat experiences a wider range of apparent wind angles than does an ice boat, whose speed is typically great enough to have the apparent wind coming from a few degrees to one side of its course, necessitating sailing with the sail sheeted in for most points of sail. On conventional sailboats, the sails are set to create lift for those points of sail where it's possible to align the leading edge of the sail with the apparent wind.

For a sailboat, point of sail affects lateral force significantly. The higher the boat points to the wind under sail, the stronger the lateral force, which requires resistance from a keel or other underwater foils, including daggerboard, centerboard, skeg and rudder. Lateral force also induces heeling in a sailboat, which requires resistance by weight of ballast from the crew or the boat itself and by the shape of the boat, especially with a catamaran. As the boat points off the wind, lateral force and the forces required to resist it become less important.

On ice boats, lateral forces are countered by the lateral resistance of the blades on ice and their distance apart, which generally prevents heeling.

Wind and currents are important factors to plan on for both offshore and inshore sailing. Predicting the availability, strength and direction of the wind is key to using its power along the desired course. Ocean currents, tides and river currents may deflect a sailing vessel from its desired course.

If the desired course is within the no-go zone, then the sailing craft must follow a zig-zag route into the wind to reach its waypoint or destination. Downwind, certain high-performance sailing craft can reach the destination more quickly by following a zig-zag route on a series of broad reaches.

Negotiating obstructions or a channel may also require a change of direction with respect to the wind, necessitating changing of tack with the wind on the opposite side of the craft, from before.

Changing tack is called ''tacking'' when the wind crosses over the bow of the craft as it turns and ''jibing'' (or ''gybing'') if the wind passes over the stern.

Wind and currents are important factors to plan on for both offshore and inshore sailing. Predicting the availability, strength and direction of the wind is key to using its power along the desired course. Ocean currents, tides and river currents may deflect a sailing vessel from its desired course.

If the desired course is within the no-go zone, then the sailing craft must follow a zig-zag route into the wind to reach its waypoint or destination. Downwind, certain high-performance sailing craft can reach the destination more quickly by following a zig-zag route on a series of broad reaches.

Negotiating obstructions or a channel may also require a change of direction with respect to the wind, necessitating changing of tack with the wind on the opposite side of the craft, from before.

Changing tack is called ''tacking'' when the wind crosses over the bow of the craft as it turns and ''jibing'' (or ''gybing'') if the wind passes over the stern.

File:Wende (Segeln).png, Tacking from the port tack (bottom) to the starboard (top) tack

File:Tacking Intervals.svg, Beating to windward on short (P1), medium (P2), and long (P3) tacks

A sailing craft can travel directly downwind only at a speed that is less than the wind speed. However, some sailing craft such as

A sailing craft can travel directly downwind only at a speed that is less than the wind speed. However, some sailing craft such as

Winds and oceanic currents are both the result of the sun powering their respective fluid media. Wind powers the sailing craft and the ocean bears the craft on its course, as currents may alter the course of a sailing vessel on the ocean or a river.

*''Wind'' – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take

Winds and oceanic currents are both the result of the sun powering their respective fluid media. Wind powers the sailing craft and the ocean bears the craft on its course, as currents may alter the course of a sailing vessel on the ocean or a river.

*''Wind'' – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take

Trimming refers to adjusting the lines that control sails, including the sheets that control angle of the sails with respect to the wind, the halyards that raise and tighten the sail, and to adjusting the hull's resistance to heeling, yawing or progress through the water.

Trimming refers to adjusting the lines that control sails, including the sheets that control angle of the sails with respect to the wind, the halyards that raise and tighten the sail, and to adjusting the hull's resistance to heeling, yawing or progress through the water.

A sailing vessel heels when the boat leans over to the side in reaction to wind forces on the sails.

A sailing vessel's form stability (derived from the shape of the hull and the position of the center of gravity) is the starting point for resisting heeling. Catamarans and iceboats have a wide stance that makes them resistant to heeling. Additional measures for trimming a sailing craft to control heeling include:

* Ballast in the keel, which counteracts heeling as the boat rolls.

* Shifting of weight, which might be crew on a trapeze or moveable ballast across the boat.

* Reducing sail

* Adjusting the depth of underwater foils to control their lateral resistance force and center of resistance

A sailing vessel heels when the boat leans over to the side in reaction to wind forces on the sails.

A sailing vessel's form stability (derived from the shape of the hull and the position of the center of gravity) is the starting point for resisting heeling. Catamarans and iceboats have a wide stance that makes them resistant to heeling. Additional measures for trimming a sailing craft to control heeling include:

* Ballast in the keel, which counteracts heeling as the boat rolls.

* Shifting of weight, which might be crew on a trapeze or moveable ballast across the boat.

* Reducing sail

* Adjusting the depth of underwater foils to control their lateral resistance force and center of resistance

''Lift'' on a sail, acting as an

''Lift'' on a sail, acting as an

File:Sailboat on broad reach with spinnaker.jpg, Spinnaker set for a broad reach, generating both lift, with separated flow, and drag.

File:Spinnaker trimmed for broad reach.jpg, Spinnaker cross-section trimmed for a broad reach showing transition from boundary layer to separated flow where vortex shedding commences.

File:Amante Choate 48 photo D Ramey Logan.jpg, Symmetric spinnaker while running downwind, primarily generating drag.

File:Symmetrical spinnaker with following apparent wind.jpg, Symmetric spinnaker cross-section with following apparent wind, showing vortex shedding.

Virtual Vault

, an online exhibition of Canadian historical art at Library and Archives Canada * Rousmaniere, John, ''The Annapolis Book of Seamanship'', Simon & Schuster, 1999 * ''Chapman Book of Piloting'' (various contributors), Hearst Corporation, 1999 * Herreshoff, Halsey (consulting editor), ''The Sailor's Handbook'', Little Brown and Company, 1983 * Seidman, David, ''The Complete Sailor'', International Marine, 1995 *

sail

A sail is a tensile structure, which is made from fabric or other membrane materials, that uses wind power to propel sailing craft, including sailing ships, sailboats, windsurfers, ice boats, and even sail-powered land vehicles. Sails may b ...

s, wingsail

A wingsail, twin-skin sail or double skin sail is a variable-Camber (aerodynamics), camber aerodynamic structure that is fitted to a marine vessel in place of conventional sails. Wingsails are analogous to Wing, airplane wings, except that they ...

s or kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have ...

s—to propel a craft on the surface of the ''water'' (sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on Mast (sailing), masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing Square rig, square-rigged or Fore-an ...

, sailboat

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

Types

Although sailboat terminology ...

, raft

A raft is any flat structure for support or transportation over water. It is usually of basic design, characterized by the absence of a hull. Rafts are usually kept afloat by using any combination of buoyant materials such as wood, sealed barre ...

, windsurfer

Windsurfing is a wind-propelled water sport that is a combination of sailing and surfing. It is also referred to as "sailboarding" and "boardsailing", and emerged in the late 1960s from the Californian aerospace and surf culture. Windsurfing gain ...

, or kitesurfer), on ''ice'' (iceboat

An iceboat (occasionally spelled ice boat or traditionally called an ice yacht) is a recreational or competition sailing craft supported on metal runners for traveling over ice. One of the runners is steerable. Originally, such craft were boats w ...

) or on ''land'' (land yacht

Land sailing, also known as sand yachting, land yachting or dirtboating, entails overland travel with a sail-powered vehicle, similar to sailing on water. Originally, a form of transportation or recreation, it has evolved primarily into a racin ...

) over a chosen course, which is often part of a larger plan of navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

.

From prehistory until the second half of the 19th century, sailing craft were the primary means of maritime trade and transportation; exploration across the seas and oceans was reliant on sail for anything other than the shortest distances. Naval power in this period used sail to varying degrees depending on the current technology, culminating in the gun-armed sailing warships of the Age of Sail

The Age of Sail is a period in European history that lasted at the latest from the mid-16th (or mid-15th) to the mid-19th centuries, in which the dominance of sailing ships in global trade and warfare culminated, particularly marked by the int ...

. Sail was slowly replaced by steam as the method of propulsion for ships over the latter part of the 19th century – seeing a gradual improvement in the technology of steam through a number of developmental steps. Steam allowed scheduled services that ran at higher average speeds than sailing vessels. Large improvements in fuel economy allowed steam to progressively outcompete sail in, ultimately, all commercial situations, giving ship-owning investors a better return on capital.

In the 21st century, most sailing represents a form of recreation

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for happiness, enjoyment, amusement, ...

or sport

Sport is a physical activity or game, often Competition, competitive and organization, organized, that maintains or improves physical ability and skills. Sport may provide enjoyment to participants and entertainment to spectators. The numbe ...

. Recreational sailing or yachting

Yachting is recreational boating activities using medium/large-sized boats or small ships collectively called yachts. Yachting is distinguished from other forms of boating mainly by the priority focus on comfort and luxury, the dependence on ma ...

can be divided into racing

In sports, racing is a competition of speed, in which competitors try to complete a given task in the shortest amount of time. Typically this involves traversing some distance, but it can be any other task involving speed to reach a specific g ...

and cruising. Cruising can include extended offshore and ocean-crossing trips, coastal sailing within sight of land, and daysailing.

Sailing relies on the physics of sails as they derive power from the wind, generating both lift and drag. On a given course, the sails are set to an angle that optimizes the development of wind power, as determined by the apparent wind

Apparent wind is the wind experienced by a moving object.

Definition of apparent wind

The ''apparent wind'' is the wind experienced by an observer in motion and is the relative velocity of the wind in relation to the observer.

The ''velocity ...

, which is the wind as sensed from a moving vessel. The forces transmitted via the sails are resisted by forces from the hull, keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

, and rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

of a sailing craft, by forces from skate runners of an iceboat, or by forces from wheels of a land sailing craft which are steering the course. This combination of forces means that it is possible to sail an upwind course as well as downwind. The course with respect to the true wind direction (as would be indicated by a stationary flag) is called a point of sail

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

The principal points of sail roughly correspond to 45° segments of a circle, starting with 0° directly into the wind ...

. Conventional sailing craft cannot derive wind power on a course with a point of sail that is too close into the wind.

History

Throughout history, sailing was a key form of propulsion that allowed for greater mobility than travel over land. This greater mobility increased capacity for exploration, trade, transport, warfare, and fishing, especially when compared to overland options. Until the significant improvements in land transportation that occurred during the 19th century, if water transport was an option, it was faster, cheaper and safer than making the same journey by land. This applied equally to sea crossings, coastal voyages and use of rivers and lakes. Examples of the consequences of this include the largegrain trade

The grain trade refers to the local and international trade in cereals such as wheat, barley, maize, rice, and other food grains. Grain is an important trade item because it is easily stored and transported with limited spoilage, unlike other agri ...

in the Mediterranean during the classical period. Cities such as Rome were totally reliant on the delivery by sailing ships of the large amounts of grain needed. It has been estimated that it cost less for a sailing ship of the Roman Empire to carry grain the length of the Mediterranean than to move the same amount 15 miles by road. Rome consumed about 150,000 tons of Egyptian grain each year over the first three centuries AD.

A similar but more recent trade, in coal, was from the mines situated close to the River Tyne

The River Tyne is a river in North East England. Its length (excluding tributaries) is . It is formed by the North Tyne and the South Tyne, which converge at Warden, Northumberland, Warden near Hexham in Northumberland at a place dubbed 'The ...

to London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

– which was already being carried out in the 14th century and grew as the city increased in size. In 1795, 4,395 cargoes of coal were delivered to London. This would have needed a fleet of about 500 sailing colliers (making 8 or 9 trips a year). This quantity had doubled by 1839. (The first steam-powered collier was not launched until 1852 and sailing colliers continued working into the 20th century.)

Exploration and research

The earliest image suggesting the use of sail on a boat may be on a piece of pottery from

The earliest image suggesting the use of sail on a boat may be on a piece of pottery from Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, dated to the 6th millennium BCE. The image is thought to show a bipod mast mounted on the hull of a reed boat – no sail is depicted. The earliest representation of a sail, from Egypt, is dated to circa 3100 BCE. The Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

is considered a suitable place for early use of sail for propulsion. This is because the river's current flows from south to north, whilst the prevailing wind direction is north to south. Therefore, a boat of that time could use the current to go north – an unobstructed trip of 750 miles – and sail to make the return trip. Evidence of early sailors has also been found in other locations, such as Kuwait, Turkey, Syria, Minoa, Bahrain, and India, among others.

Austronesian peoples

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melan ...

used sails from some time before 2000 BCE. Their expansion from what is now Southern China and Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

started in 3000 BCE. Their technology came to include outriggers

An outrigger is a projecting structure on a boat, with specific meaning depending on types of vessel. Outriggers may also refer to legs on a wheeled vehicle that are folded out when it needs stabilization, for example on a crane that lifts he ...

, catamaran

A catamaran () (informally, a "cat") is a watercraft with two parallel hull (watercraft), hulls of equal size. The wide distance between a catamaran's hulls imparts stability through resistance to rolling and overturning; no ballast is requi ...

s, and crab claw sail

The crab claw sail is a fore-and-aft triangular sail with spars along upper and lower edges. The crab claw sail was first developed by the Austronesian peoples by at least 2000 BCE. It is sometimes known as the Oceanic lateen or the Oceanic ...

s, which enabled the Austronesian Expansion

The Austronesian people, sometimes referred to as Austronesian-speaking peoples, are a large group of peoples who have settled in Taiwan, maritime Southeast Asia, parts of mainland Southeast Asia, Micronesia, coastal New Guinea, Island Melanesi ...

at around 3000 to 1500 BCE into the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia

Maritime Southeast Asia comprises the Southeast Asian countries of Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and East Timor.

The terms Island Southeast Asia and Insular Southeast Asia are sometimes given the same meaning as ...

, and thence to Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of approximately 2,000 small islands in the Northwestern Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: Maritime Southeast Asia to the west, Poly ...

, Island Melanesia

Island Melanesia is a subregion of Melanesia in Oceania.

It is located east of New Guinea island, from the Bismarck Archipelago to New Caledonia.Steadman, 2006. ''Extinction & biogeography of tropical Pacific birds''

See also Archaeology a ...

, Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

, and Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

. Since there is no commonality between the boat technology of China and the Austronesians, these distinctive characteristics must have been developed at or some time after the beginning of the expansion. They traveled vast distances of open ocean in outrigger canoe

Outrigger boats are various watercraft featuring one or more lateral support floats known as outriggers, which are fastened to one or both sides of the main hull (watercraft), hull. They can range from small dugout (boat), dugout canoes to large ...

s using navigation methods such as stick charts. The windward sailing capability of Austronesian boats allowed a strategy of sailing to windward on a voyage of exploration, with a return downwind either to report a discovery or if no land was found. This was well suited to the prevailing winds as Pacific islands were steadily colonized.

By the time of the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

—starting in the 15th century—square-rigged, multi-masted vessels were the norm and were guided by navigation techniques that included the magnetic compass and making sightings of the sun and stars that allowed transoceanic voyages.

During the Age of Discovery, sailing ships figured in European voyages around Africa to China and Japan; and across the Atlantic Ocean to North and South America. Later, sailing ships ventured into the Arctic to explore northern sea routes and assess natural resources. In the 18th and 19th centuries sailing vessels made Hydrographic survey

Hydrographic survey is the science of measurement and description of features which affect maritime navigation, marine construction, dredging, offshore wind farms, offshore oil exploration and drilling and related activities. Surveys may als ...

s to develop charts for navigation and, at times, carried scientists aboard as with the voyages of James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

and the Second voyage of HMS ''Beagle'' with naturalist Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English Natural history#Before 1900, naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all speci ...

.

Commerce

In the early 1800s, fast blockade-running schooners and brigantines—

In the early 1800s, fast blockade-running schooners and brigantines—Baltimore Clipper

A Baltimore clipper is a fast sailing ship historically built on the mid-Atlantic seaboard of the United States, especially at the port of Baltimore, Maryland. An early form of clipper, the name is most commonly applied to two-masted schoone ...

s—evolved into three-masted, typically ship-rigged sailing vessels with fine lines that enhanced speed, but lessened capacity for high-value cargo, like tea from China. Masts were as high as and were able to achieve speeds of , allowing for passages of up to per 24 hours. Clippers yielded to bulkier, slower vessels, which became economically competitive in the mid 19th century. Sail plans with just fore-and-aft sails (schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

s), or a mixture of the two (brigantine

A brigantine is a two-masted sailing vessel with a fully square-rigged foremast and at least two sails on the main mast: a square topsail and a gaff sail mainsail (behind the mast). The main mast is the second and taller of the two masts.

Ol ...

s, barque

A barque, barc, or bark is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel with three or more mast (sailing), masts of which the fore mast, mainmast, and any additional masts are Square rig, rigged square, and only the aftmost mast (mizzen in three-maste ...

s and barquentine

A barquentine or schooner barque (alternatively "barkentine" or "schooner bark") is a sailing vessel with three or more masts; with a square rigged foremast and fore-and-aft rigged main, mizzen and any other masts.

Modern barquentine sailing ...

s) emerged. Coastal top-sail schooners with a crew as small as two managing the sail handling became an efficient way to carry bulk cargo, since only the fore-sails required tending while tacking and steam-driven machinery was often available for raising the sails and the anchor.

Iron-hulled sailing ships represented the final evolution of sailing ships at the end of the Age of Sail. They were built to carry bulk cargo for long distances in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They were the largest of merchant sailing ships, with three to five masts and square sails, as well as other sail plan

A sail plan is a drawing of a sailing craft, viewed from the side, depicting its sails, the spars that carry them and some of the rigging that supports the rig. By extension, "sail plan" describes the arrangement of sails on a craft. A sailing c ...

s. They carried bulk cargoes between continents. Iron-hulled sailing ships were mainly built from the 1870s to 1900, when steamship

A steamship, often referred to as a steamer, is a type of steam-powered vessel, typically ocean-faring and seaworthy, that is propelled by one or more steam engines that typically move (turn) propellers or paddlewheels. The first steamships ...

s began to outpace them economically because of their ability to keep a schedule regardless of the wind. Steel hulls also replaced iron hulls at around the same time. Even into the twentieth century, sailing ships could hold their own on transoceanic voyages such as Australia to Europe, since they did not require bunkerage for coal nor fresh water for steam, and they were faster than the early steamers, which usually could barely make . Ultimately, the steamships' independence from the wind and their ability to take shorter routes, passing through the Suez

Suez (, , , ) is a Port#Seaport, seaport city with a population of about 800,000 in north-eastern Egypt, located on the north coast of the Gulf of Suez on the Red Sea, near the southern terminus of the Suez Canal. It is the capital and largest c ...

and Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

s, made sailing ships uneconomical.

Naval power

Until the general adoption of carvel-built ships that relied on an internal skeleton structure to bear the weight of the ship and for gun ports to be cut in the side, sailing ships were just vehicles for delivering fighters to the enemy for engagement. Early Phoenician, Greek, Roman galleys would ram each other, then pour onto the decks of the opposing force and continue the fight by hand, meaning that these galleys required speed and maneuverability. This need for speed translated into longer ships with multiple rows of oars along the sides, known as biremes andtriremes

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Romans.

The trireme derives its name from its thre ...

. Typically, the sailing ships during this time period were the merchant ships.

By 1500, Gun port

A gunport is an opening in the side of the hull (watercraft), hull of a ship, above the waterline, which allows the muzzle of artillery pieces mounted on the gun deck to fire outside. The origin of this technology is not precisely known, but can ...

s allowed sailing vessels to sail alongside an enemy vessel and fire a broadside of multiple cannon. This development allowed for naval fleets to array themselves into a line of battle

The line of battle or the battle line is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships (known as ships of the line) forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for date ...

, whereby, warships

A warship or combatant ship is a naval ship that is used for naval warfare. Usually they belong to the navy branch of the armed forces of a nation, though they have also been operated by individuals, cooperatives and corporations. As well as ...

would maintain their place in the line to engage the enemy in a parallel or perpendicular line.

Modern applications

While the use of sailing vessels for commerce or naval power has been supplanted with engine-driven vessels, there continue to be commercial operations that take passengers on sailing cruises. Modern navies also employ sailing vessels to train cadets in

While the use of sailing vessels for commerce or naval power has been supplanted with engine-driven vessels, there continue to be commercial operations that take passengers on sailing cruises. Modern navies also employ sailing vessels to train cadets in seamanship

Seamanship is the skill, art, competence (human resources), competence, and knowledge of operating a ship, boat or other craft on water. The'' Oxford Dictionary of English, Oxford Dictionary'' states that seamanship is "The skill, techniques, o ...

. Recreation or sport accounts for the bulk of sailing in modern boats.

Recreation

Recreational sailing can be divided into two categories, day-sailing, where one gets off the boat for the night, and cruising, where one stays aboard. Day-sailing primarily affords experiencing the pleasure of sailing a boat. No destination is required. It is an opportunity to share the experience with others. A variety of boats with no overnight accommodations, ranging in size from to over , may be regarded as day sailors. Cruising on a sailing yacht may be either near-shore or passage-making out of sight of land and entails the use of sailboats that support sustained overnight use. Coastal cruising grounds include areas of the Mediterranean and Black Seas, Northern Europe, Western Europe and islands of the North Atlantic, West Africa and the islands of the South Atlantic, the Caribbean, and regions of North and Central America. Passage-making under sail occurs on routes through oceans all over the world. Circular routes exist between the Americas and Europe, and between South Africa and South America. There are many routes from the Americas, Australia, New Zealand, and Asia to island destinations in the South Pacific. Some cruiserscircumnavigate

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical body (e.g. a planet or moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first circumnavigation of the Earth was the Magellan Exped ...

the globe.

Sport

Sailing as a sport is organized on a hierarchical basis, starting at theyacht club

A yacht club is a boat club specifically related to yachting.

Description

Yacht clubs are mostly located by the sea, although there some that have been established at a lake or riverside locations. Yacht or sailing clubs have either a mar ...

level and reaching up into national and international federations; it may entail racing yachts, sailing dinghies, or other small, open sailing craft, including iceboats and land yachts. Sailboat racing

The sport of sailing involves a variety of competitive sailing formats that are sanctioned through various sailing federations and yacht clubs. Racing disciplines include matches within a fleet of sailing craft, between a pair thereof or among ...

is governed by World Sailing

World Sailing is the international sports governing body for sailing (sport), sailing; it is recognized by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Paralympic Committee (IPC).

History

The creation of the International Yac ...

with most racing formats using the Racing Rules of Sailing

The ''Racing Rules of Sailing'' (often abbreviated to RRS) govern the conduct of yacht racing, windsurfing, kitesurfing, model boat racing, dinghy racing and virtually any other form of racing around a course with more than one vessel while power ...

. It entails a variety of different disciplines, including:

*Oceanic racing, held over long distances and in open water, often last multiple days and include world circumnavigation

Circumnavigation is the complete navigation around an entire island, continent, or astronomical object, astronomical body (e.g. a planet or natural satellite, moon). This article focuses on the circumnavigation of Earth.

The first circumnaviga ...

, such as the Vendée Globe

-->

The Vendée Globe is a single-handed (solo) non-stop, unassisted round the world yacht race. The race was founded by Philippe Jeantot in 1989, and since 1992 has taken place every four years. It is named after the Département of Vendé ...

and The Ocean Race.

*Fleet racing, featuring multiple boats in a regatta

Boat racing is a sport in which boats, or other types of watercraft, race on water. Boat racing powered by oars is recorded as having occurred in ancient Egypt, and it is likely that people have engaged in races involving boats and other wa ...

that comprises multiple races or heats.

*Match racing comprises two boats competing against each other, as is done with the America's Cup

The America's Cup is a sailing competition and the oldest international competition still operating in any sport. America's Cup match races are held between two sailing yachts: one from the yacht club that currently holds the trophy (known ...

, vying to cross a finish line, first.

*Team racing between two teams of three boats each in a format analogous to match racing.

*Speed sailing to set new records for different categories of craft with oversight by the World Sailing Speed Record Council.

*Sail boarding has a variety of disciplines particular to that sport.Navigation

Point of sail

A sailing craft's ability to derive power from the wind depends on thepoint of sail

A point of sail is a sailing craft's direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface.

The principal points of sail roughly correspond to 45° segments of a circle, starting with 0° directly into the wind ...

it is on—the direction of travel under sail in relation to the true wind direction over the surface. The principal points of sail roughly correspond to 45° segments of a circle, starting with 0° directly into the wind. For many sailing craft, the arc spanning 45° on either side of the wind is a "no-go" zone,

where a sail is unable to mobilize power from the wind. Sailing on a course as close to the wind as possible—approximately 45°—is termed "close-hauled". At 90° off the wind, a craft is on a "beam reach". At 135° off the wind, a craft is on a "broad reach". At 180° off the wind (sailing in the same direction as the wind), a craft is "running downwind".

In points of sail that range from close-hauled to a broad reach, sails act substantially like a wing, with lift predominantly propelling the craft. In points of sail from a broad reach to down wind, sails act substantially like a parachute, with drag predominantly propelling the craft. For craft with little forward resistance, such as ice boat

An iceboat (occasionally spelled ice boat or traditionally called an ice yacht) is a recreational or competition sailing craft supported on metal runners for traveling over ice. One of the runners is steerable. Originally, such craft were boats ...

s and land yacht

Land sailing, also known as sand yachting, land yachting or dirtboating, entails overland travel with a sail-powered vehicle, similar to sailing on water. Originally, a form of transportation or recreation, it has evolved primarily into a racin ...

s, this transition occurs further off the wind than for sailboat

A sailboat or sailing boat is a boat propelled partly or entirely by sails and is smaller than a sailing ship. Distinctions in what constitutes a sailing boat and ship vary by region and maritime culture.

Types

Although sailboat terminology ...

s and sailing ship

A sailing ship is a sea-going vessel that uses sails mounted on Mast (sailing), masts to harness the power of wind and propel the vessel. There is a variety of sail plans that propel sailing ships, employing Square rig, square-rigged or Fore-an ...

s.

Wind direction for points of sail always refers to the ''true wind''—the wind felt by a stationary observer. The ''apparent wind

Apparent wind is the wind experienced by a moving object.

Definition of apparent wind

The ''apparent wind'' is the wind experienced by an observer in motion and is the relative velocity of the wind in relation to the observer.

The ''velocity ...

''—the wind felt by an observer on a moving sailing craft—determines the motive power for sailing craft.

Effect on apparent wind

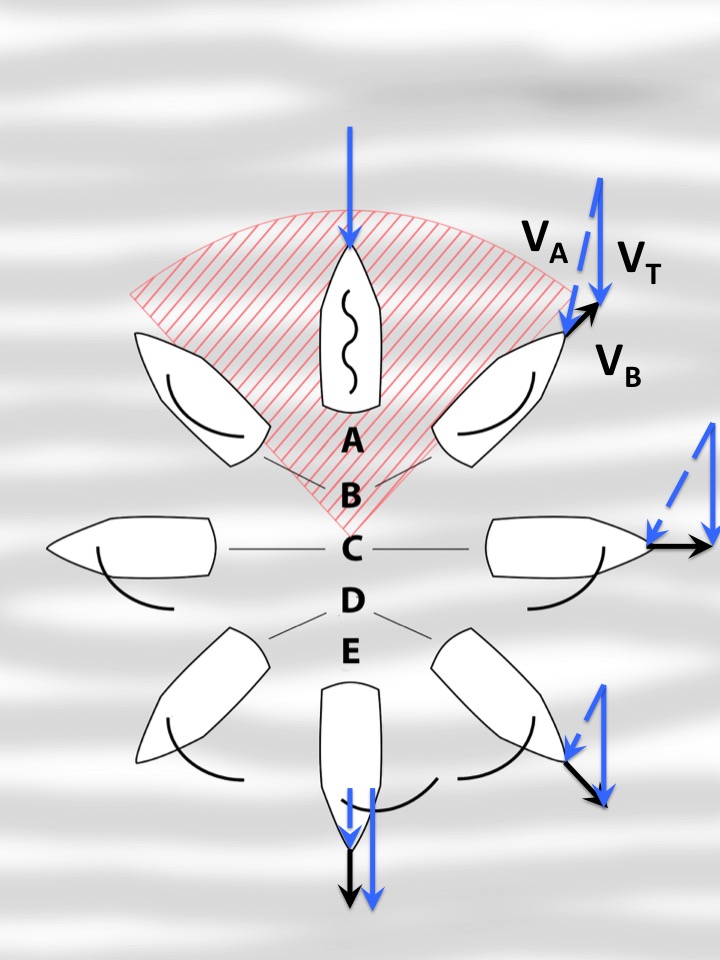

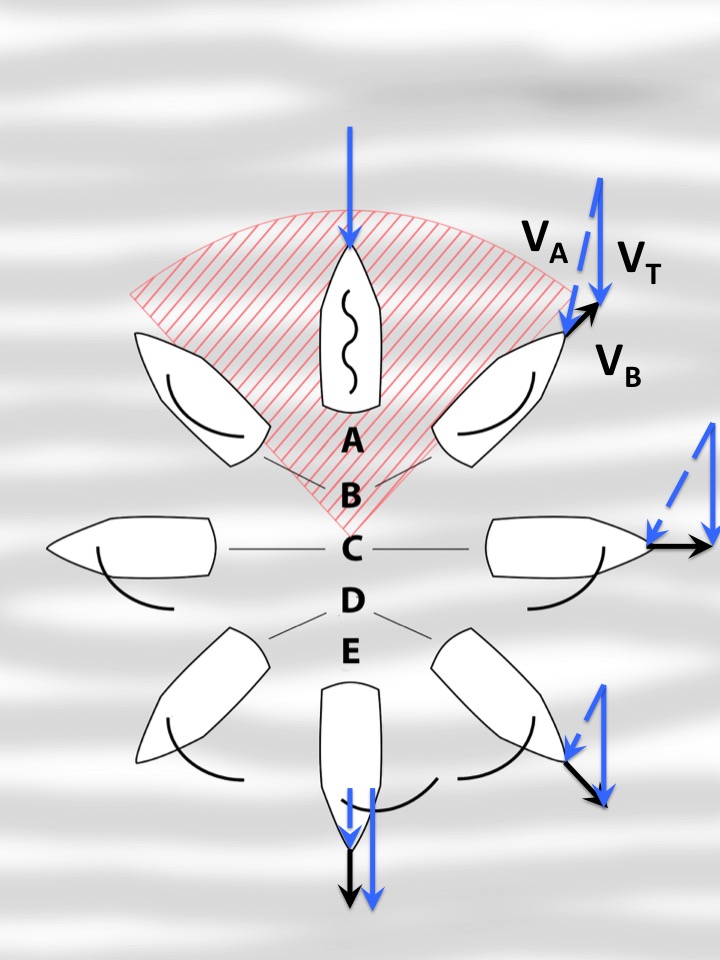

True wind velocity (VT) combines with the sailing craft's velocity (VB) to give the ''apparent wind velocity'' (VA), the air velocity experienced by instrumentation or crew on a moving sailing craft. Apparent wind velocity provides the motive power for the sails on any given point of sail. It varies from being the true wind velocity of a stopped craft in irons in the no-go zone, to being faster than the true wind speed as the sailing craft's velocity adds to the true windspeed on a reach. It diminishes towards zero for a craft sailing dead downwind.As the boat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind becomes smaller and the lateral component becomes less; boat speed is highest on the beam reach. File:Ice boat apparent wind on different points of sail.jpg, Apparent wind on an ''iceboat''.

As the iceboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind increases slightly and the boat speed is highest on the broad reach. The sail is sheeted in for all three points of sail.

Course under sail

Upwind

A sailing craft can sail on a course anywhere outside of its no-go zone. If the next waypoint or destination is within the arc defined by the no-go zone from the craft's current position, then it must perform a series of tacking maneuvers to get there on a zigzag route, called ''beating to windward''. The progress along that route is called the ''course made good''; the speed between the starting and ending points of the route is called the ''speed made good'' and is calculated by the distance between the two points, divided by the travel time. The limiting line to the waypoint that allows the sailing vessel to leave it to leeward is called the ''layline''. Whereas some Bermuda-rigged sailing yachts can sail as close as 30° to the wind, most 20th-Century square riggers are limited to 60° off the wind.Fore-and-aft rig

A fore-and-aft rig is a sailing ship rig with sails set mainly in the median plane of the keel, rather than perpendicular to it, as on a square-rigged vessel.

Description

Fore-and-aft rigged sails include staysails, Bermuda rigged sails, g ...

s are designed to operate with the wind on either side, whereas square rig

Square rig is a generic type of sail plan, sail and rigging arrangement in which a sailing ship, sailing vessel's primary driving sails are carried on horizontal spar (sailing), spars that are perpendicular (or wikt:square#Adjective, square) to t ...

s and kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have ...

s are designed to have the wind come from one side of the sail only.

Because the lateral wind forces are highest when sailing close-hauled, the resisting water forces around the vessel's keel, centerboard, rudder and other foils must also be highest in order to limit sideways motion or leeway

Leeway is the amount of drift motion to leeward of an object floating in the water caused by the component of the wind vector that is perpendicular to the object’s forward motion.Bowditch. (1995). The American Practical Navigator. Pub. No. 9. 1 ...

. Ice boats and land yachts minimize lateral motion with resistance from their blades or wheels.

=Changing tack by tacking

= ''Tacking'' or ''coming about'' is a maneuver by which a sailing craft turns its bow into and through the wind (referred to as "the eye of the wind") so that the apparent wind changes from one side to the other, allowing progress on the opposite tack. The type of sailing rig dictates the procedures and constraints on achieving a tacking maneuver. Fore-and-aft rigs allow their sails to hang limp as they tack; square rigs must present the full frontal area of the sail to the wind, when changing from side to side; andwindsurfer

Windsurfing is a wind-propelled water sport that is a combination of sailing and surfing. It is also referred to as "sailboarding" and "boardsailing", and emerged in the late 1960s from the Californian aerospace and surf culture. Windsurfing gain ...

s have flexibly pivoting and fully rotating masts that get flipped from side to side.

Downwind

A sailing craft can travel directly downwind only at a speed that is less than the wind speed. However, some sailing craft such as

A sailing craft can travel directly downwind only at a speed that is less than the wind speed. However, some sailing craft such as iceboat

An iceboat (occasionally spelled ice boat or traditionally called an ice yacht) is a recreational or competition sailing craft supported on metal runners for traveling over ice. One of the runners is steerable. Originally, such craft were boats w ...

s, sand yachts, and some high-performance sailboats can achieve a higher downwind velocity made good

Velocity made good, or VMG, is a term used in sailing, especially in yacht racing, indicating the speed of a sailboat towards (or from) the direction of the wind. The concept is useful because a sailboat cannot sail directly upwind, and thus often ...

by traveling on a series of broad reaches, punctuated by jibes in between. It was explored by sailing vessels starting in 1975 and now extends to high-performance skiffs, catamarans and foiling sailboats.

Navigating a channel or a downwind course among obstructions may necessitate changes in direction that require a change of tack, accomplished with a jibe.

=Changing tack by jibing

= ''Jibing'' or ''gybing'' is a sailing maneuver by which a sailing craft turns itsstern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

past the eye of the wind so that the apparent wind changes from one side to the other, allowing progress on the opposite tack. This maneuver can be done on smaller boats by pulling the tiller towards yourself (the opposite side of the sail). As with tacking, the type of sailing rig dictates the procedures and constraints for jibing. Fore-and-aft sails with booms, gaffs or sprits are unstable when the free end points into the eye of the wind and must be controlled to avoid a violent change to the other side; square rigs as they present the full area of the sail to the wind from the rear experience little change of operation from one tack to the other; and windsurfer

Windsurfing is a wind-propelled water sport that is a combination of sailing and surfing. It is also referred to as "sailboarding" and "boardsailing", and emerged in the late 1960s from the Californian aerospace and surf culture. Windsurfing gain ...

s again have flexibly pivoting and fully rotating masts that get flipped from side to side.

Wind and currents

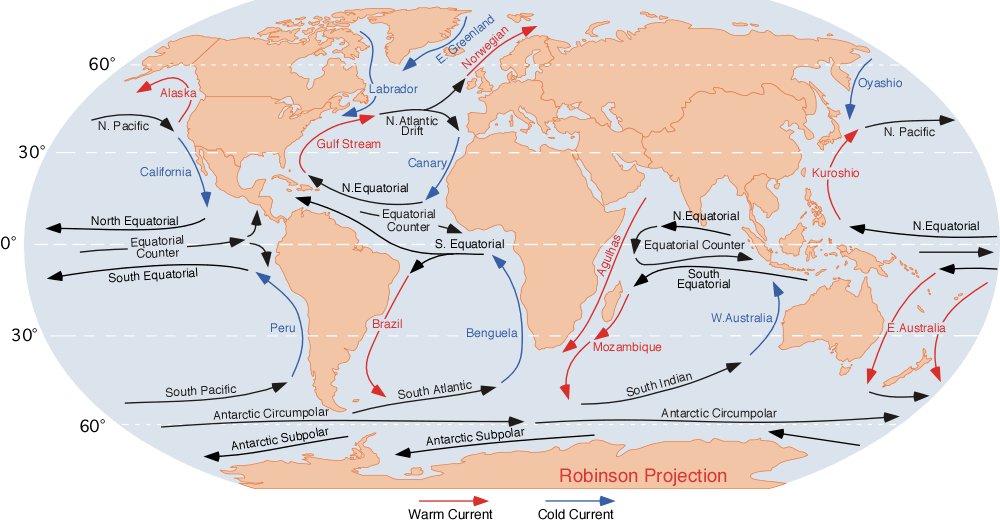

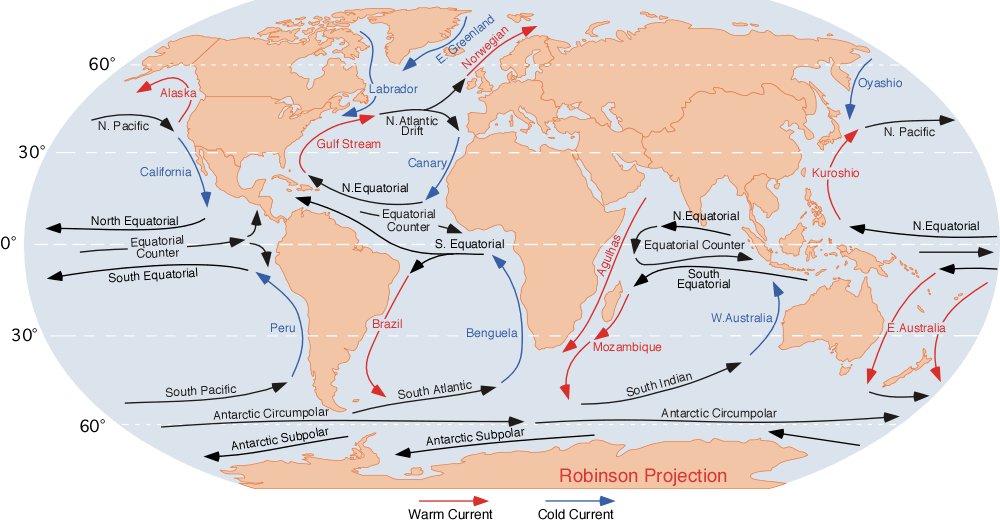

Winds and oceanic currents are both the result of the sun powering their respective fluid media. Wind powers the sailing craft and the ocean bears the craft on its course, as currents may alter the course of a sailing vessel on the ocean or a river.

*''Wind'' – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take

Winds and oceanic currents are both the result of the sun powering their respective fluid media. Wind powers the sailing craft and the ocean bears the craft on its course, as currents may alter the course of a sailing vessel on the ocean or a river.

*''Wind'' – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take atmospheric circulation

Atmospheric circulation is the large-scale movement of Atmosphere of Earth, air and together with ocean circulation is the means by which thermal energy is redistributed on the surface of the Earth. The Earth's atmospheric circulation varies fro ...

into account, which causes zones of westerlies

The westerlies, anti-trades, or prevailing westerlies, are prevailing winds from the west toward the east in the middle latitudes between 30 and 60 degrees latitude. They originate from the high-pressure areas in the horse latitudes (about ...

, easterlies, trade wind

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere, ...

s and high-pressure zones with light winds, sometimes called horse latitude

The horse latitudes are the latitudes about 30 degrees north and south of the Equator. They are characterized by sunny skies, calm winds, and very little precipitation. They are also known as subtropical ridges or highs. It is a high-pressure ...

s, in between. Sailors predict wind direction and strength with knowledge of high- and low-pressure area

In meteorology, a low-pressure area (LPA), low area or low is a region where the atmospheric pressure is lower than that of surrounding locations. It is the opposite of a high-pressure area. Low-pressure areas are commonly associated with incle ...

s, and the weather front

A weather front is a boundary separating air masses for which several characteristics differ, such as air density, wind, temperature, and humidity. Disturbed and unstable weather due to these differences often arises along the boundary. For ins ...

s that accompany them. Along coastal areas, sailors contend with diurnal changes in wind direction—flowing off the shore at night and onto the shore during the day.

Local temporary wind shifts are called ''lifts'', when they improve the sailing craft's ability travel along its ''rhumb line

In navigation, a rhumb line, rhumb (), or loxodrome is an arc crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle, that is, a path with constant azimuth ( bearing as measured relative to true north).

Navigation on a fixed course (i.e., s ...

'' in the direction of the next waypoint. Unfavorable wind shifts are called ''headers''.

*''Currents'' – On a global scale, vessels making long voyages must take major ocean current

An ocean current is a continuous, directed movement of seawater generated by a number of forces acting upon the water, including wind, the Coriolis effect, breaking waves, cabbeling, and temperature and salinity differences. Depth contours, sh ...

circulation into account.

Major oceanic currents, like the Gulf Stream

The Gulf Stream is a warm and swift Atlantic ocean current that originates in the Gulf of Mexico and flows through the Straits of Florida and up the eastern coastline of the United States, then veers east near 36°N latitude (North Carolin ...

in the Atlantic Ocean and the Kuroshio Current

The , also known as the Black Current or is a north-flowing, warm ocean current on the west side of the North Pacific Ocean basin. It was named for the deep blue appearance of its waters. Similar to the Gulf Stream in the North Atlantic, the Ku ...

in the Pacific Ocean require planning for the effect that they will have on a transiting vessel's track. Likewise, tides affect a vessel's track, especially in areas with large tidal ranges, like the Bay of Fundy

The Bay of Fundy () is a bay between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, with a small portion touching the U.S. state of Maine. It is an arm of the Gulf of Maine. Its tidal range is the highest in the world.

The bay was ...

or along Southeast Alaska

Southeast Alaska, often abbreviated to southeast or southeastern, and sometimes called the Alaska(n) panhandle, is the southeastern portion of the U.S. state of Alaska, bordered to the east and north by the northern half of the Canadian provi ...

, or where the tide flows through strait

A strait is a water body connecting two seas or water basins. The surface water is, for the most part, at the same elevation on both sides and flows through the strait in both directions, even though the topography generally constricts the ...

s, like Deception Pass

Deception Pass (; ) is a strait separating Whidbey Island from Fidalgo Island, in the northwest part of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. It connects Skagit Bay, part of Puget Sound, with the Strait of Juan de Fuca. A pair of bri ...

in Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ; ) is a complex estuary, estuarine system of interconnected Marine habitat, marine waterways and basins located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Washington (state), Washington. As a part of the Salish Sea, the sound ...

. Mariners use tide and current tables to inform their navigation. Before the advent of motors, it was advantageous for sailing vessels to enter or leave port or to pass through a strait with the tide.

Trimming

Trimming refers to adjusting the lines that control sails, including the sheets that control angle of the sails with respect to the wind, the halyards that raise and tighten the sail, and to adjusting the hull's resistance to heeling, yawing or progress through the water.

Trimming refers to adjusting the lines that control sails, including the sheets that control angle of the sails with respect to the wind, the halyards that raise and tighten the sail, and to adjusting the hull's resistance to heeling, yawing or progress through the water.

Sails

In their most developed version, square sails are controlled by two each of: sheets, braces, clewlines, and reef tackles, plus four buntlines, each of which may be controlled by a crew member as the sail is adjusted. Towards the end of the Age of Sail, steam-powered machinery reduced the number of crew required to trim sail. Adjustment of the angle of a fore-and-aft sail with respect to the apparent wind is controlled with a line, called a "sheet". On points of sail between close-hauled and a broad reach, the goal is typically to create flow along the sail to maximize power through lift. Streamers placed on the surface of the sail, called tell-tales, indicate whether that flow is smooth or turbulent. Smooth flow on both sides indicates proper trim. A jib and mainsail are typically configured to be adjusted to create a smoothlaminar flow

Laminar flow () is the property of fluid particles in fluid dynamics to follow smooth paths in layers, with each layer moving smoothly past the adjacent layers with little or no mixing. At low velocities, the fluid tends to flow without lateral m ...

, leading from one to the other in what is called the "slot effect".

On downwind points of sail, power is achieved primarily with the wind pushing on the sail, as indicated by drooping tell-tales. Spinnaker

A spinnaker is a sail designed specifically for sailing off the wind on courses between a Point of sail#Reaching, reach (wind at 90° to the course) to Point of sail#Running downwind, downwind (course in the same direction as the wind). Spinna ...

s are light-weight, large-area, highly curved sails that are adapted to sailing off the wind.

In addition to using the sheets to adjust the angle with respect to the apparent wind, other lines control the shape of the sail, notably the outhaul

An outhaul is a control line found on a sailboat. It is an element of the running rigging, used to attach the mainsail clew to the boom and tensions the foot of the sail. It commonly uses a block at the boom end and a cleat on the boom, closer ...

, halyard

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term "halyard" derives from the Middle English ''halier'' ("rope to haul with"), with the last syllable altered by association with the E ...

, boom vang

A boom vang (US) or kicking strap (UK) (often shortened to "vang" or "kicker") is a line or piston system on a sailboat used to exert downward force on the boom and thus control the shape of the sail.

The Collins English Dictionary defines it a ...

and backstay

A backstay is a piece of standing rigging on a sailing vessel that runs from the mast to either its transom or rear quarter, counteracting the forestay and jib. It is an important sail trim control and has a direct effect on the shape of the ma ...

. These control the curvature that is appropriate to the windspeed, the higher the wind, the flatter the sail. When the wind strength is greater than these adjustments can accommodate to prevent overpowering the sailing craft, then reducing sail area through reefing

Reefing reduces the area of a sail, usually by folding or rolling one edge of the canvas in on itself and attaching the unused portion to a Spar (sailing), spar or a , as the primary measure to preserve a sailing vessel's stability in strong wi ...

, substituting a smaller sail or by other means.

Reducing sail

Reducing sail on square-rigged ships could be accomplished by exposing less of each sail, by tying it off higher up with reefing points. Additionally, as winds get stronger, sails can be furled or removed from the spars, entirely until the vessel is surviving hurricane-force winds under "bare poles". On fore-and-aft rigged vessels, reducing sail may furling the jib and by reefing or partially lowering the mainsail, that is reducing the area of a sail without actually changing it for a smaller sail. This results both in a reduced sail area but also in a lower centre of effort from the sails, reducing the heeling moment and keeping the boat more upright. There are three common methods of reefing the mainsail: *Slab reefing, which involves lowering the sail by about one-quarter to one-third of its full length and tightening the lower part of the sail using anouthaul

An outhaul is a control line found on a sailboat. It is an element of the running rigging, used to attach the mainsail clew to the boom and tensions the foot of the sail. It commonly uses a block at the boom end and a cleat on the boom, closer ...

or a pre-loaded reef line through a cringle at the new clew

Sail components include the features that define a sail's shape and function, plus its constituent parts from which it is manufactured. A sail may be classified in a variety of ways, including by its orientation to the vessel (e.g. ''fore-and-a ...

, and hook through a cringle at the new tack

Thermoproteati is a kingdom of archaea. Its synonym, "TACK", is an acronym for Thaumarchaeota (now Nitrososphaerota), Aigarchaeota, Crenarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), and Korarchaeota (now Thermoproteota), the first groups discovered. They ...

.

*In-boom roller-reefing, with a horizontal foil inside the boom. This method allows for standard- or full-length horizontal battens.

*In-mast (or on-mast) roller-reefing. This method rolls the sail up around a vertical foil either inside a slot in the mast, or affixed to the outside of the mast. It requires a mainsail with either no battens, or newly developed vertical battens.

Hull

Hull trim has three aspects, each tied to an axis of rotation, they are controlling: * Heeling (rotation about the longitudinal axis or leaning to either port or starboard) * Helm force (rotation about the vertical axis) * Hull drag (rotation about the horizontal axis amidships) Each is a reaction to forces on sails and is achieved either by weight distribution or by management of the center of force of the underwater foils (keel, daggerboard, etc.), compared with the center of force on the sails.Heeling

A sailing vessel heels when the boat leans over to the side in reaction to wind forces on the sails.

A sailing vessel's form stability (derived from the shape of the hull and the position of the center of gravity) is the starting point for resisting heeling. Catamarans and iceboats have a wide stance that makes them resistant to heeling. Additional measures for trimming a sailing craft to control heeling include:

* Ballast in the keel, which counteracts heeling as the boat rolls.

* Shifting of weight, which might be crew on a trapeze or moveable ballast across the boat.

* Reducing sail

* Adjusting the depth of underwater foils to control their lateral resistance force and center of resistance

A sailing vessel heels when the boat leans over to the side in reaction to wind forces on the sails.

A sailing vessel's form stability (derived from the shape of the hull and the position of the center of gravity) is the starting point for resisting heeling. Catamarans and iceboats have a wide stance that makes them resistant to heeling. Additional measures for trimming a sailing craft to control heeling include:

* Ballast in the keel, which counteracts heeling as the boat rolls.

* Shifting of weight, which might be crew on a trapeze or moveable ballast across the boat.

* Reducing sail

* Adjusting the depth of underwater foils to control their lateral resistance force and center of resistance

Helm force

The alignment of center of force of the sails with center of resistance of the hull and its appendices controls whether the craft will track straight with little steering input, or whether correction needs to be made to hold it away from turning into the wind (a weather helm) or turning away from the wind (a lee helm). A center of force behind the center of resistance causes a weather helm. The center of force ahead of the center of resistance causes a lee helm. When the two are closely aligned, the helm is neutral and requires little input to maintain course.Hull drag

Fore-and-aft weight distribution changes the cross-section of a vessel in the water. Small sailing craft are sensitive to crew placement. They are usually designed to have the crew stationed midships to minimize hull drag in the water.Other aspects of seamanship

Seamanship

Seamanship is the skill, art, competence (human resources), competence, and knowledge of operating a ship, boat or other craft on water. The'' Oxford Dictionary of English, Oxford Dictionary'' states that seamanship is "The skill, techniques, o ...

encompasses all aspects of taking a sailing vessel in and out of port, navigating it to its destination, and securing it at anchor or alongside a dock. Important aspects of seamanship include employing a common language aboard a sailing craft and the management of lines that control the sails and rigging.

Nautical terms

Nautical terms for elements of a vessel:starboard

Port and starboard are Glossary of nautical terms (M-Z), nautical terms for watercraft and spacecraft, referring respectively to the left and right sides of the vessel, when aboard and facing the Bow (watercraft), bow (front).

Vessels with bil ...

(right-hand side), port or larboard (left-hand side), forward or fore (frontward), aft or abaft (rearward), bow (forward part of the hull), stern (aft part of the hull), beam (the widest part). Spars, supporting sails, include masts, booms, yards, gaffs and poles. Moveable lines that control sails or other equipment are known collectively as a vessel's running rigging

Running rigging is the rigging of a sailing, sailing vessel that is used for raising, lowering, shaping and controlling the sails on a sailing vessel—as opposed to the standing rigging, which supports the Mast (sailing), mast and bowsprit. Runn ...

. Lines that raise sails are called ''halyard

In sailing, a halyard or halliard is a line (rope) that is used to hoist a ladder, sail, flag or yard. The term "halyard" derives from the Middle English ''halier'' ("rope to haul with"), with the last syllable altered by association with the E ...

s'' while those that strike them are called ''downhauls''. Lines that adjust (trim) the sails are called '' sheets''. These are often referred to using the name of the sail they control (such as ''main sheet'' or ''jib sheet''). '' Guys'' are used to control the ends of other spars

SPARS was the authorized nickname for the United States Coast Guard (USCG) Women's Reserve. The nickname was derived from the USCG's motto, "—"Always Ready" (''SPAR''). The Women's Reserve was established by law in November 1942 during Wor ...

such as spinnaker pole

A spinnaker pole is a spar used in sailboats (both dinghies and yachts) to help support and control a variety of headsails, particularly the spinnaker. It is also used with other sails, such as genoas and jibs, when sailing downwind with no s ...

s. Lines used to tie a boat up when alongside are called ''docklines'', ''docking cables'' or ''mooring warps''. A ''rode'' is what attaches an anchored boat to its anchor

An anchor is a device, normally made of metal, used to secure a vessel to the bed of a body of water to prevent the craft from drifting due to wind or current. The word derives from Latin ', which itself comes from the Greek ().

Anch ...

. Other than starboard and port, the sides of the boat are defined by their relationship to the wind. The terms to describe the two sides are Windward and leeward

In geography and seamanship, windward () and leeward () are directions relative to the wind. Windward is ''upwind'' from the point of reference, i.e., towards the direction from which the wind is coming; leeward is ''downwind'' from the point o ...

. The windward side of the boat is the side that is upwind while the leeward side is the side that is downwind.

Management of lines

The following knots are commonly used to handle ropes and lines on sailing craft: *Bowline

The bowline () is an ancient and simple knot used to form a fixed loop at the end of a rope. It has the virtues of being both easy to tie and untie; most notably, it is easy to untie after being subjected to a load. The bowline is sometimes refe ...

– forms a loop at the end of a rope or line, useful for lassoing a piling.

* Cleat hitch – affixes a line to a cleat, used with docking lines.

* Clove hitch

The clove hitch is an ancient type of knot, made of two successive single hitches tied around an object. It is most effectively used to secure a middle section of rope to an object it crosses over, such as a line on a fencepost. It can also be ...

– two half hitches, used for tying onto a post or hanging a fender.

* Figure-eight – a stopper knot, prevents a line from sliding past the opening in a fitting.

* Rolling hitch – a friction hitch onto a line or a spar that pulls in one direction and slides in the other.

* Sheet bend

The sheet bend (also known as weaver's knot and weaver's hitch) is a bend knot. It is practical for joining lines of different diameter or rigidity.

It is quick and easy to tie, and is considered so essential it is the first knot given in the ...

– joins two rope ends, when improvising a longer line.

* Reef knot

The reef knot, or square knot, is an ancient and simple binding knot used to secure a rope or line around an object. It is sometimes also referred to as a Hercules knot or Heracles knot. The knot is formed by tying a left-handed overhand knot ...

or square knot – used for reefing or storing a sail by tying two ends of a line together.

Lines and halyards are typically coiled neatly for stowage and reuse.

Sail physics

The physics of sailing arises from a balance of forces between the wind powering the sailing craft as it passes over its sails and the resistance by the sailing craft against being blown off course, which is provided in the water by thekeel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

, rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

, underwater foils and other elements of the underbody of a sailboat, on ice by the runners of an iceboat

An iceboat (occasionally spelled ice boat or traditionally called an ice yacht) is a recreational or competition sailing craft supported on metal runners for traveling over ice. One of the runners is steerable. Originally, such craft were boats w ...

, or on land by the wheels of a sail-powered land vehicle.

Forces on sails depend on wind speed and direction and the speed and direction of the craft. The speed of the craft at a given point of sail contributes to the "apparent wind

Apparent wind is the wind experienced by a moving object.

Definition of apparent wind

The ''apparent wind'' is the wind experienced by an observer in motion and is the relative velocity of the wind in relation to the observer.

The ''velocity ...

"—the wind speed and direction as measured on the moving craft. The apparent wind on the sail creates a total aerodynamic force, which may be resolved into drag—the force component in the direction of the apparent wind—and lift

Lift or LIFT may refer to:

Physical devices

* Elevator, or lift, a device used for raising and lowering people or goods

** Paternoster lift, a type of lift using a continuous chain of cars which do not stop

** Patient lift, or Hoyer lift, mobile ...

—the force component normal (90°) to the apparent wind. Depending on the alignment of the sail with the apparent wind (''angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a Airfoil#Airfoil terminology, reference line on a body (often the chord (aircraft), chord line of an airfoil) and the vector (geometry), vector representing the relat ...

''), lift or drag may be the predominant propulsive component. Depending on the angle of attack of a set of sails with respect to the apparent wind, each sail is providing motive force to the sailing craft either from lift-dominant attached flow or drag-dominant separated flow. Additionally, sails may interact with one another to create forces that are different from the sum of the individual contributions of each sail, when used alone.

Apparent wind velocity

The term "velocity

Velocity is a measurement of speed in a certain direction of motion. It is a fundamental concept in kinematics, the branch of classical mechanics that describes the motion of physical objects. Velocity is a vector (geometry), vector Physical q ...

" refers both to speed and direction. As applied to wind, ''apparent wind velocity'' (VA) is the air velocity acting upon the leading edge of the most forward sail or as experienced by instrumentation or crew on a moving sailing craft. In nautical terminology, wind speeds are normally expressed in knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot or knots may also refer to:

Other common meanings

* Knot (unit), of speed

* Knot (wood), a timber imperfection

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Knots'' (film), a 2004 film

* ''Kn ...

and wind angles in degrees. All sailing craft reach a constant ''forward velocity'' (VB) for a given ''true wind velocity'' (VT) and ''point of sail''. The craft's point of sail affects its velocity for a given true wind velocity. Conventional sailing craft cannot derive power from the wind in a "no-go" zone that is approximately 40° to 50° away from the true wind, depending on the craft. Likewise, the directly downwind speed of all conventional sailing craft is limited to the true wind speed. As a sailboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind becomes smaller and the lateral component becomes less; boat speed is highest on the beam reach. To act like an airfoil, the sail on a sailboat is sheeted further out as the course is further off the wind. As an iceboat sails further from the wind, the apparent wind increases slightly and the boat speed is highest on the broad reach. In order to act like an airfoil, the sail on an iceboat is sheeted in for all three points of sail.

Lift and drag on sails

''Lift'' on a sail, acting as an

''Lift'' on a sail, acting as an airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more Lift (force), lift than Drag (physics), drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foil (fl ...

, occurs in a direction ''perpendicular'' to the incident airstream (the apparent wind velocity for the headsail) and is a result of pressure differences between the windward and leeward surfaces and depends on the angle of attack, sail shape, air density, and speed of the apparent wind. The lift force results from the average pressure on the windward surface of the sail being higher than the average pressure on the leeward side. These pressure differences arise in conjunction with the curved airflow. As air follows a curved path along the windward side of a sail, there is a pressure gradient

In vector calculus, the gradient of a scalar-valued differentiable function f of several variables is the vector field (or vector-valued function) \nabla f whose value at a point p gives the direction and the rate of fastest increase. The g ...

perpendicular to the flow direction with higher pressure on the outside of the curve and lower pressure on the inside. To generate lift, a sail must present an "angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a Airfoil#Airfoil terminology, reference line on a body (often the chord (aircraft), chord line of an airfoil) and the vector (geometry), vector representing the relat ...

" between the chord line of the sail and the apparent wind velocity. The angle of attack is a function of both the craft's point of sail and how the sail is adjusted with respect to the apparent wind.

As the lift generated by a sail increases, so does lift-induced drag

Lift-induced drag, induced drag, vortex drag, or sometimes drag due to lift, in aerodynamics, is an aerodynamic drag force that occurs whenever a moving object redirects the airflow coming at it. This drag force occurs in airplanes due to wings or ...

, which together with parasitic drag

Parasitic drag, also known as profile drag, is a type of aerodynamic drag that acts on any object when the object is moving through a fluid. Parasitic drag is defined as the combination of '' form drag'' and '' skin friction drag''.

It is named a ...

constitute total ''drag'', which acts in a direction ''parallel'' to the incident airstream. This occurs as the angle of attack increases with sail trim or change of course and causes the lift coefficient

In fluid dynamics, the lift coefficient () is a dimensionless quantity that relates the lift generated by a lifting body to the fluid density around the body, the fluid velocity and an associated reference area. A lifting body is a foil or a co ...

to increase up to the point of aerodynamic stall

In fluid dynamics, a stall is a reduction in the lift coefficient generated by a foil as angle of attack exceeds its critical value.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', p. 486. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ...

along with the lift-induced drag coefficient. At the onset of stall, lift is abruptly decreased, as is lift-induced drag. Sails with the apparent wind behind them (especially going downwind) operate in a stalled condition.

Lift and drag are components of the total aerodynamic force on sail, which are resisted by forces in the water (for a boat) or on the traveled surface (for an iceboat or land sailing craft). Sails act in two basic modes; under the ''lift-predominant'' mode, the sail behaves in a manner analogous to a ''wing'' with airflow attached to both surfaces; under the ''drag-predominant'' mode, the sail acts in a manner analogous to a ''parachute'' with airflow in detached flow, eddying around the sail.

Lift predominance (wing mode)

Sails allow progress of a sailing craft to windward, thanks to their ability to generate lift (and the craft's ability to resist the lateral forces that result). Each sail configuration has a characteristic coefficient of lift and attendant coefficient of drag, which can be determined experimentally and calculated theoretically. Sailing craft orient their sails with a favorable angle of attack between the entry point of the sail and the apparent wind even as their course changes. The ability to generate lift is limited by sailing too close to the wind when no effective angle of attack is available to generate lift (causing luffing) and sailing sufficiently off the wind that the sail cannot be oriented at a favorable angle of attack to prevent the sail from stalling withflow separation

In fluid dynamics, flow separation or boundary layer separation is the detachment of a boundary layer from a surface into a wake.

A boundary layer exists whenever there is relative movement between a fluid and a solid surface with viscous fo ...

.

Drag predominance (parachute mode)

When sailing craft are on a course where the angle between the sail and the apparent wind (the angle of attack) exceeds the point of maximum lift, separation of flow occurs. Drag increases and lift decreases with increasing angle of attack as the separation becomes progressively pronounced until the sail is perpendicular to the apparent wind, when lift becomes negligible and drag predominates. In addition to the sails used upwind,spinnaker