S Protein on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Spike (S) glycoprotein (sometimes also called spike protein, formerly known as E2) is the largest of the four major

The spike protein is very large, often 1200 to 1400

The spike protein is very large, often 1200 to 1400

Spike glycoprotein is heavily

Spike glycoprotein is heavily

The spike protein is not required for viral assembly or the formation of

The spike protein is not required for viral assembly or the formation of

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein in its pre-fusion conformation is in a

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein in its pre-fusion conformation is in a

structural protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respon ...

s found in coronavirus

Coronaviruses are a group of related RNA viruses that cause diseases in mammals and birds. In humans and birds, they cause respiratory tract infections that can range from mild to lethal. Mild illnesses in humans include some cases of the comm ...

es. The spike protein assembles into trimers that form large structures, called spikes or peplomer

In virology, a spike protein or peplomer protein is a protein that forms a large structure known as a spike or peplomer projecting from the surface of an enveloped virus. as cited in The proteins are usually glycoproteins that form dimers ...

s, that project from the surface of the virion

A virion (plural, ''viria'' or ''virions'') is an inert virus particle capable of invading a Cell (biology), cell. Upon entering the cell, the virion disassembles and the genetic material from the virus takes control of the cell infrastructure, t ...

. The distinctive appearance of these spikes when visualized using negative stain In microscopy, negative staining is an established method, often used in diagnostic microscopy, for contrasting a thin specimen with an optically opaque fluid. In this technique, the background is stained, leaving the actual specimen untouched, ...

transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) is a microscopy technique in which a beam of electrons is transmitted through a specimen to form an image. The specimen is most often an ultrathin section less than 100 nm thick or a suspension on a g ...

, "recalling the solar corona

In astronomy, a corona (: coronas or coronae) is the outermost layer of a star's Stellar atmosphere, atmosphere. It is a hot but relatively luminosity, dim region of Plasma (physics), plasma populated by intermittent coronal structures such as so ...

", gives the virus family its main name.

The function of the spike glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide (sugar) chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known a ...

is to mediate viral entry

Viral entry is the earliest stage of infection in the viral life cycle, as the virus comes into contact with the host cell (biology), cell and introduces viral material into the cell. The major steps involved in viral entry are shown below. Desp ...

into the host cell

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include ...

by first interacting with molecules on the exterior cell surface and then fusing the viral and cellular membranes

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

. Spike glycoprotein is a class I fusion protein that contains two regions, known as S1 and S2, responsible for these two functions. The S1 region contains the receptor-binding domain

A domain is a geographic area controlled by a single person or organization. Domain may also refer to:

Law and human geography

* Demesne, in English common law and other Medieval European contexts, lands directly managed by their holder rather ...

that binds to receptors on the cell surface. Coronaviruses use a very diverse range of receptors; HCoV-NL63, SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

(which causes SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus. The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the ...

) and SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

(which causes COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a contagious disease caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. In January 2020, the disease spread worldwide, resulting in the COVID-19 pandemic.

The symptoms of COVID‑19 can vary but often include fever ...

) all interact with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an enzyme that can be found either attached to the membrane of cells (mACE2) in the intestines, kidney, testis, gallbladder, and heart or in a soluble form (sACE2). Both membrane bound and soluble ACE2 ...

(ACE2). The S2 region contains the fusion peptide

Membrane fusion proteins (not to be confused with chimeric or fusion proteins) are proteins that cause fusion of biological membranes. Membrane fusion is critical for many biological processes, especially in eukaryotic development and viral entry ...

and other fusion infrastructure necessary for membrane fusion with the host cell, a required step for infection and viral replication

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome ...

. Spike glycoprotein determines the virus' host range

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasite, parasitic, a mutualism (biology), mutualistic, or a commensalism, commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with ...

(which organisms it can infect) and cell tropism

Endothelial cell tropism or endotheliotropism is a type of tissue tropism or host tropism that characterizes an pathogen's ability to recognize and infect an endothelial cell. Pathogens, such as viruses, can target a specific tissue type or multipl ...

(which cells or tissues it can infect within an organism).

Spike glycoprotein is highly immunogenic

Immunogenicity is the ability of a foreign substance, such as an antigen, to provoke an immune response in the body of a human or other animal. It may be wanted or unwanted:

* Wanted immunogenicity typically relates to vaccines, where the injectio ...

. Antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

against spike glycoprotein are found in patients recovered from SARS and COVID-19. Neutralizing antibodies target epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The part of an antibody that binds to the epitope is called a paratope. Although e ...

s on the receptor-binding domain. Most COVID-19 vaccine

A COVID19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID19).

Knowledge about the structure and fun ...

development efforts in response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

aim to activate the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

against the spike protein.

Structure

The spike protein is very large, often 1200 to 1400

The spike protein is very large, often 1200 to 1400 amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

residues long; it is 1273 residues in SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

. It is a single-pass transmembrane protein with a short C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, carboxy tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When t ...

tail on the interior of the virus, a transmembrane helix

A transmembrane domain (TMD, TM domain) is a membrane-spanning protein domain. TMDs may consist of one or several alpha-helices or a transmembrane beta barrel. Because the interior of the lipid bilayer is hydrophobic, the amino acid residues in T ...

, and a large N-terminal

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the amin ...

ectodomain

An ectodomain is the domain of a membrane protein that extends into the extracellular space (the space outside a cell). Ectodomains are usually the parts of proteins that initiate contact with surfaces, which leads to signal transduction. A n ...

exposed on the virus exterior.

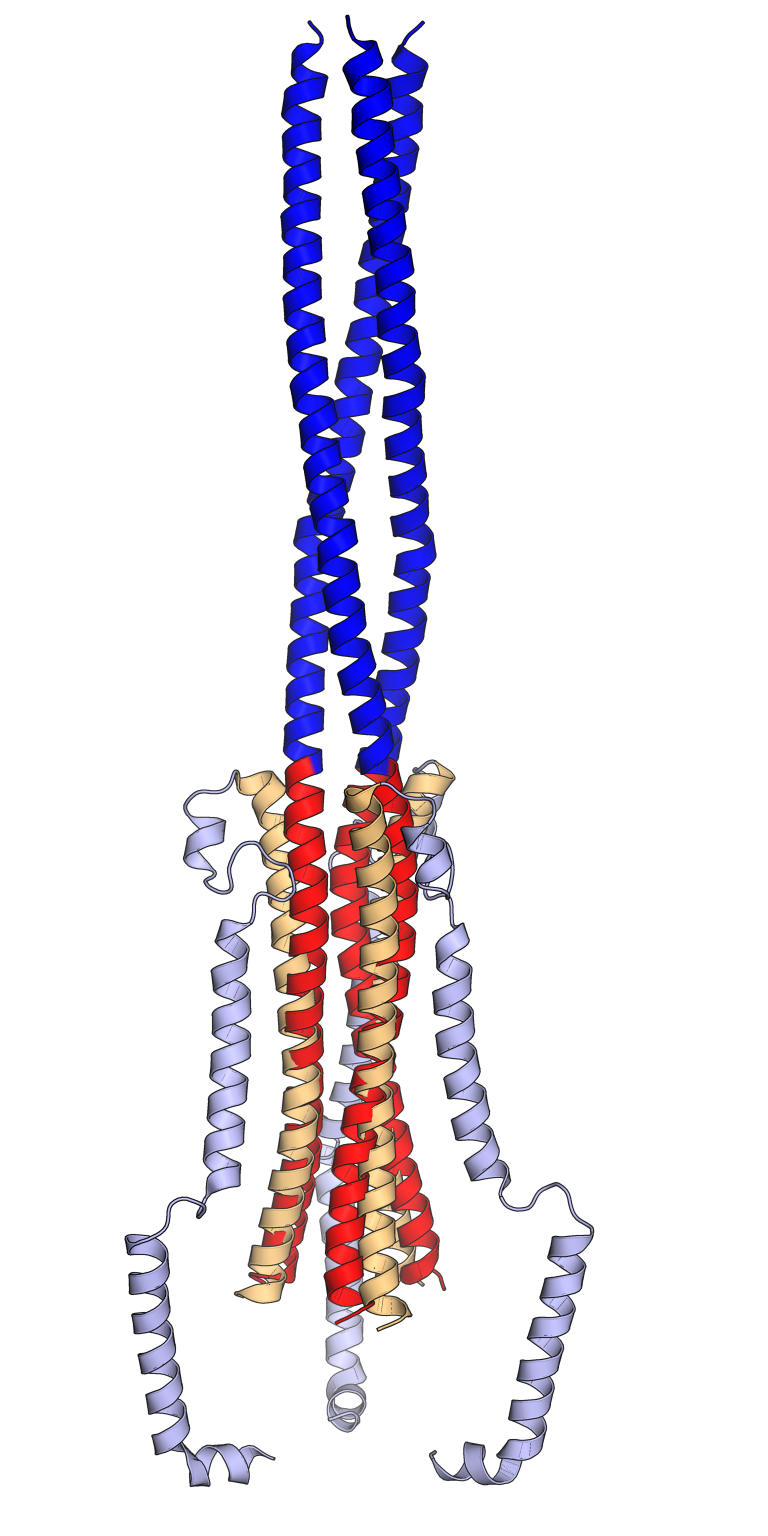

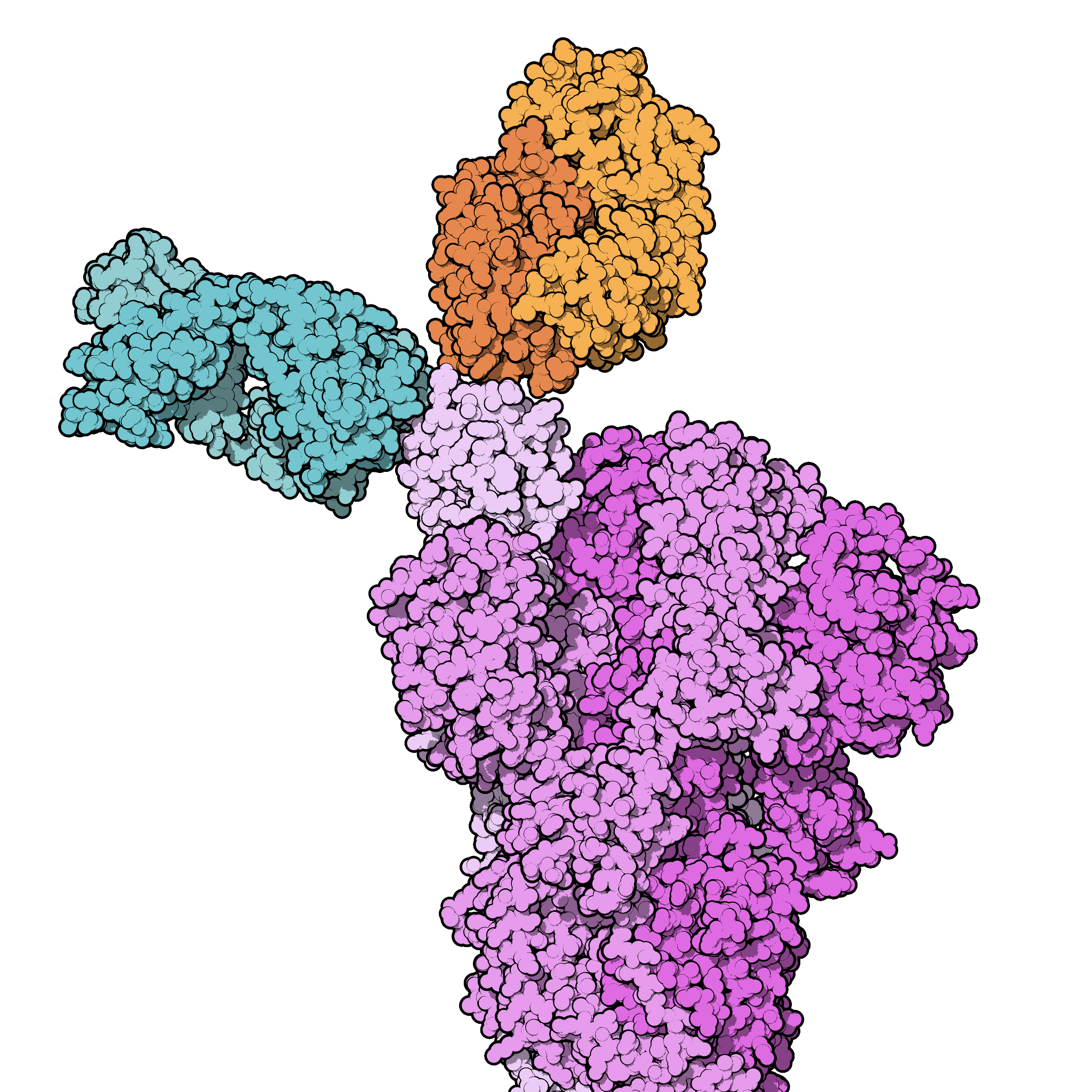

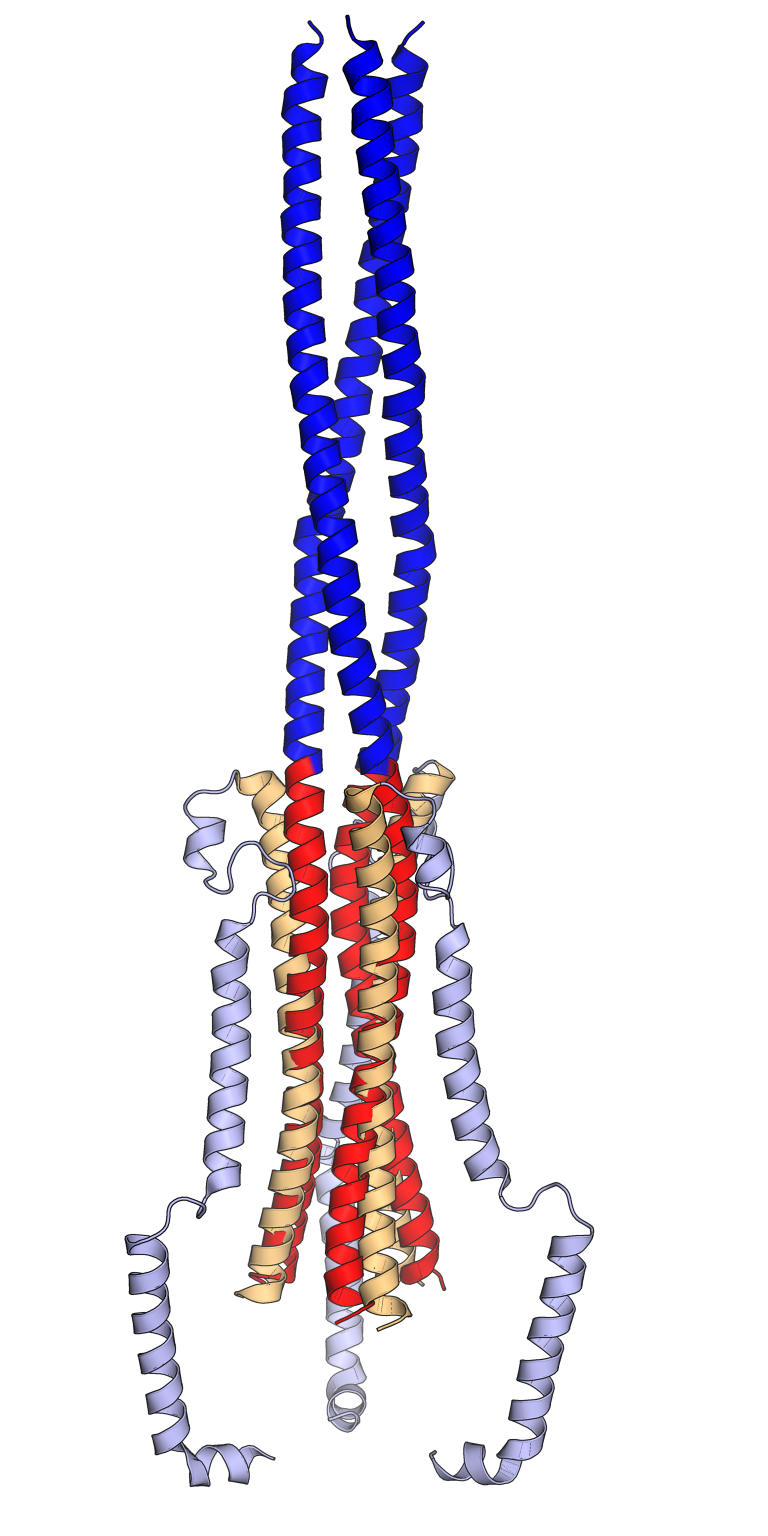

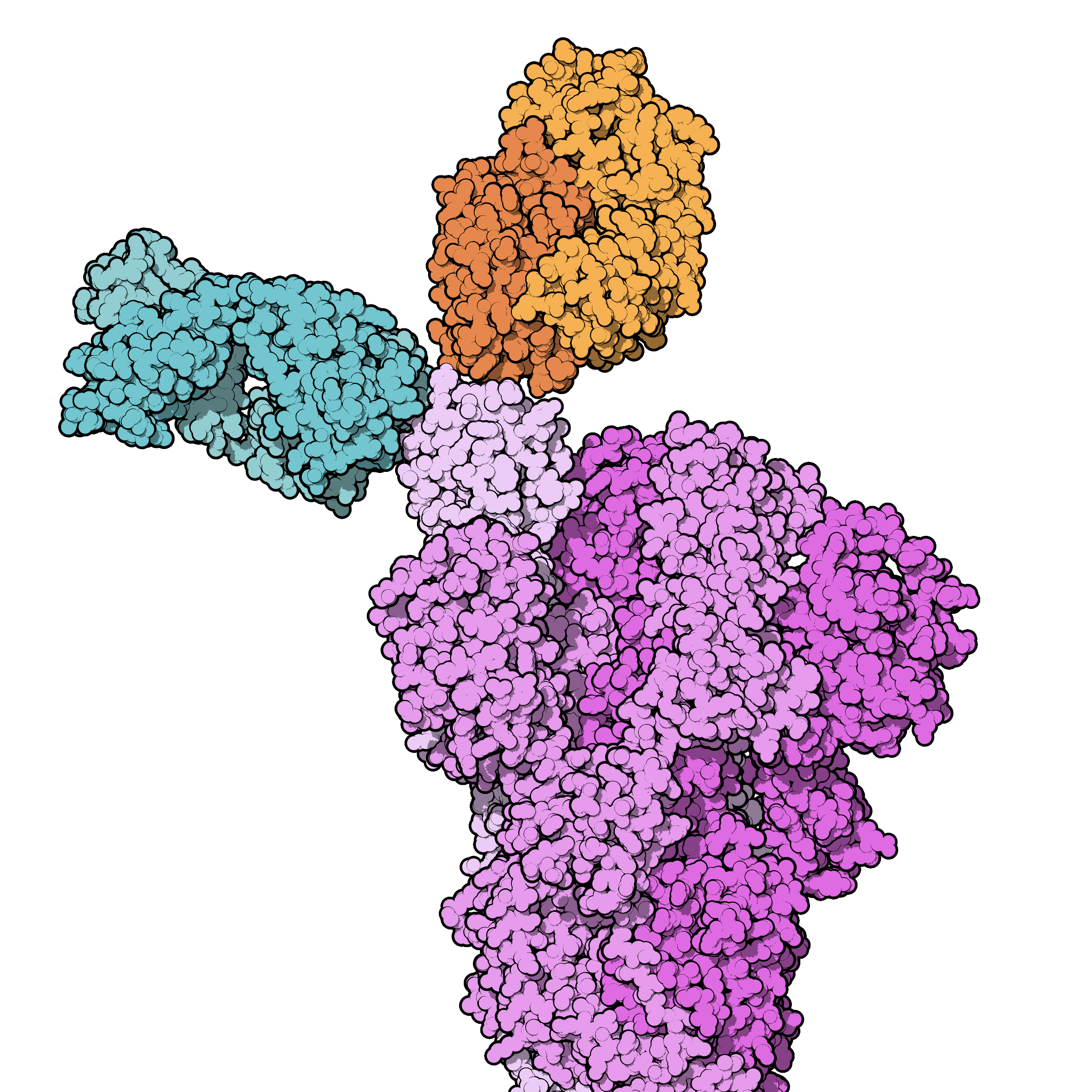

Spike glycoprotein forms homotrimers in which three copies of the protein interact through their ectodomains. The trimer structures have been described as club- pear-, or petal-shaped. Each spike protein contains two regions known as S1 and S2, and in the assembled trimer the S1 regions at the N-terminal end form the portion of the protein furthest from the viral surface while the S2 regions form a flexible "stalk" containing most of the protein-protein interactions that hold the trimer in place.

S1

The S1 region of the spike glycoprotein is responsible for interacting with receptor molecules on the surface of the host cell in the first step ofviral entry

Viral entry is the earliest stage of infection in the viral life cycle, as the virus comes into contact with the host cell (biology), cell and introduces viral material into the cell. The major steps involved in viral entry are shown below. Desp ...

. S1 contains two domains, called the N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminal domain (CTD), sometimes also known as the A and B domains. Depending on the coronavirus, either or both domains may be used as receptor-binding domains (RBD). Target receptors can be very diverse, including cell surface receptor

Cell surface receptors (membrane receptors, transmembrane receptors) are receptors that are embedded in the plasma membrane of cells. They act in cell signaling by receiving (binding to) extracellular molecules. They are specialized integra ...

proteins and sugars such as sialic acid

Sialic acids are a class of alpha-keto acid sugars with a nine-carbon backbone.

The term "sialic acid" () was first introduced by Swedish biochemist Gunnar Blix in 1952. The most common member of this group is ''N''-acetylneuraminic acid ...

s as receptors or coreceptors. In general, the NTD binds sugar molecules while the CTD binds proteins, with the exception of mouse hepatitis virus which uses its NTD to interact with a protein receptor called CEACAM1

Carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (biliary glycoprotein) (CEACAM1) also known as CD66a (Cluster of Differentiation 66a), is a human glycoprotein, and a member of the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) gene family.

Function ...

. The NTD has a galectin-like protein fold

A protein superfamily is the largest grouping (clade) of proteins for which common ancestry can be inferred (see homology). Usually this common ancestry is inferred from structural alignment and mechanistic similarity, even if no sequence similar ...

, but binds sugar molecules somewhat differently than galectins. The observed binding of N-acetylneuraminic acid by the NTD and loss of that binding through mutation of the corresponding sugar binding pocket in emergent variants of concern has suggested a potential role for tranisent sugar-binding in the zoonosis of SARS-CoV-2, consistent with prior evolutionary proposals.

The CTD is responsible for the interactions of MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV, ''Betacoronavirus cameli'') or EMC/2012 ( HCoV-EMC/2012), is the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is a species of coronavirus which infects humans, ba ...

with its receptor dipeptidyl peptidase-4, and those of SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

and SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

with their receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) is an enzyme that can be found either attached to the membrane of cells (mACE2) in the intestines, kidney, testis, gallbladder, and heart or in a soluble form (sACE2). Both membrane bound and soluble ACE2 ...

(ACE2). The CTD of these viruses can be further divided into two subdomains, known as the core and the extended loop or receptor-binding motif (RBM), where most of the residues that directly contact the target receptor are located. There are subtle differences, mainly in the RBM, between the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins' interactions with ACE2. Comparisons of spike proteins from multiple coronaviruses suggest that divergence in the RBM region can account for differences in target receptors, even when the core of the S1 CTD is structurally very similar.

Within coronavirus lineages, as well as across the four major coronavirus subgroups, the S1 region is less well conserved than S2, as befits its role in interacting with virus-specific host cell receptors. Within the S1 region, the NTD is more highly conserved than the CTD.

S2

The S2 region of spike glycoprotein is responsible formembrane fusion

In membrane biology, fusion is the process by which two initially distinct lipid bilayers merge their hydrophobic cores, resulting in one interconnected structure. If this fusion proceeds completely through both leaflets of both bilayers, an aqueou ...

between the viral envelope

A viral envelope is the outermost layer of many types of viruses. It protects the genetic material in their life cycle when traveling between host cells. Not all viruses have envelopes. A viral envelope protein or E protein is a protein in the en ...

and the host cell

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include ...

, enabling entry of the virus' genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

into the cell. The S2 region contains the fusion peptide

Membrane fusion proteins (not to be confused with chimeric or fusion proteins) are proteins that cause fusion of biological membranes. Membrane fusion is critical for many biological processes, especially in eukaryotic development and viral entry ...

, a stretch of mostly hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

amino acids whose function is to enter and destabilize the host cell membrane. S2 also contains two heptad repeat

The heptad repeat is an example of a structural motif that consists of a repeating pattern of seven amino acids:

''a b c d e f g''

H P P H C P C

where H represents hydrophobic residues, C represents, typically, charged residues, and P repre ...

subdomains known as HR1 and HR2, sometimes called the "fusion core" region. These subdomains undergo dramatic conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

s during the fusion process to form a six-helix bundle, a characteristic feature of the class I fusion proteins. The S2 region is also considered to include the transmembrane helix

A transmembrane domain (TMD, TM domain) is a membrane-spanning protein domain. TMDs may consist of one or several alpha-helices or a transmembrane beta barrel. Because the interior of the lipid bilayer is hydrophobic, the amino acid residues in T ...

and C-terminal

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, carboxy tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When t ...

tail located in the interior of the virion.

Relative to S1, the S2 region is very well conserved among coronaviruses.

Post-translational modifications

Spike glycoprotein is heavily

Spike glycoprotein is heavily glycosylated

Glycosylation is the reaction in which a carbohydrate (or ' glycan'), i.e. a glycosyl donor, is attached to a hydroxyl or other functional group of another molecule (a glycosyl acceptor) in order to form a glycoconjugate. In biology (but not ...

through N-linked glycosylation

''N''-linked glycosylation is the attachment of an oligosaccharide, a carbohydrate consisting of several sugar molecules, sometimes also referred to as glycan, to a nitrogen atom (the amide nitrogen of an asparagine (Asn) residue of a protein), i ...

. Studies of the SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

spike protein have also reported O-linked glycosylation

''O''-linked glycosylation is the attachment of a sugar molecule to the oxygen atom of serine (Ser) or threonine (Thr) residues in a protein. ''O''-glycosylation is a post-translational modification that occurs after the protein has been synthesis ...

in the S1 region. The C-terminal tail, located in the interior of the virion, is enriched in cysteine

Cysteine (; symbol Cys or C) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine enables the formation of Disulfide, disulfide bonds, and often participates in enzymatic reactions as ...

residues and is palmitoylated.

Spike proteins are activated through proteolytic cleavage

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Protein degradation is a major regulatory mechanism of gene expression and contributes substantially to shaping mammalian proteomes. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis o ...

. They are cleaved by host cell protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s at the S1-S2 boundary and later at what is known as the S2' site at the N-terminus of the fusion peptide. This cleavage may occur upon receptor binding, or the spike protein may be pre-cleaved such as by Furin at a furin cleavage site if one is present.

Conformational change

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein undergoes a very largeconformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

during the fusion process. Both the pre-fusion and post-fusion states of several coronaviruses, especially SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

, have been studied by cryo-electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a transmission electron microscopy technique applied to samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An ...

. Functionally important protein dynamics

In molecular biology, proteins are generally thought to adopt unique structures determined by their amino acid sequences. However, proteins are not strictly static objects, but rather populate ensembles of (sometimes similar) conformations. Tran ...

have also been observed within the pre-fusion state, in which the relative orientations of some of the S1 regions relative to S2 in a trimer can vary. In the closed state, all three S1 regions are packed closely and the region that makes contact with host cell receptors is sterically inaccessible, while the open states have one or two S1 RBDs more accessible for receptor binding, in an open or "up" conformation.

Expression and localization

Thegene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

encoding the spike protein is located toward the 3' end

Directionality, in molecular biology and biochemistry, is the end-to-end chemical orientation of a single strand of nucleic acid. In a single strand of DNA or RNA, the chemical convention of naming carbon atoms in the nucleotide pentose-sugar-ri ...

of the virus's positive-sense RNA genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, along with the genes for the other three structural proteins and various virus-specific accessory protein

A viral regulatory and accessory protein is a type of viral protein that can play an indirect role in the function of a virus.

An example is Nef (protein), Nef.

References

Further reading

*

Viral proteins

{{virus-stub ...

s. Protein trafficking

Protein targeting or protein sorting is the biological mechanism by which proteins are transported to their appropriate destinations within or outside the cell. Proteins can be targeted to the inner space of an organelle, different intracellular m ...

of spike proteins appears to depend on the coronavirus subgroup: when expressed in isolation without other viral proteins, spike proteins from betacoronavirus

''Betacoronavirus'' (β-CoVs or Beta-CoVs) is one of four genera (''Alphacoronavirus, Alpha''-, ''Beta-'', ''Gammacoronavirus, Gamma-'', and ''Deltacoronavirus (genus), Delta-'') of coronaviruses. Member viruses are Viral envelope, enveloped, p ...

es are able to reach the cell surface

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extra ...

, while those from alphacoronavirus

Alphacoronaviruses (Alpha-CoV) are members of the first of the four genera (''Alpha''-, '' Beta-'', '' Gamma-'', and '' Delta-'') of coronaviruses. They are positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses that infect mammals, including humans. They ...

es and gammacoronavirus

''Gammacoronavirus'' (Gamma-CoV) is one of the four genera (''Alphacoronavirus, Alpha''-, ''Betacoronavirus, Beta-'', ''Gamma-'', and ''Deltacoronavirus (genus), Delta-'') of coronaviruses. It is in the subfamily ''Orthocoronavirinae'' of the fa ...

es are retained intracellularly. In the presence of the M protein, spike protein trafficking is altered and instead is retained at the ERGIC, the site at which viral assembly occurs. In SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

, both the M and the E protein modulate spike protein trafficking through different mechanisms.

The spike protein is not required for viral assembly or the formation of

The spike protein is not required for viral assembly or the formation of virus-like particle

Virus-like particles (VLPs) are molecules that closely resemble viruses, but are non-infectious because they contain no viral genetic material. They can be naturally occurring or synthesized through the individual expression of viral structural pro ...

s; however, presence of spike may influence the size of the envelope. Incorporation of the spike protein into virions during assembly and budding is dependent on protein-protein interactions with the M protein through the C-terminal tail. Examination of virions using cryo-electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a transmission electron microscopy technique applied to samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An ...

suggests that there are approximately 25 to 100 spike trimers per virion.

Function

The spike protein is responsible forviral entry

Viral entry is the earliest stage of infection in the viral life cycle, as the virus comes into contact with the host cell (biology), cell and introduces viral material into the cell. The major steps involved in viral entry are shown below. Desp ...

into the host cell

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasitic, a mutualistic, or a commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with nourishment and shelter. Examples include ...

, a required early step in viral replication

Viral replication is the formation of biological viruses during the infection process in the target host cells. Viruses must first get into the cell before viral replication can occur. Through the generation of abundant copies of its genome ...

. It is essential for replication. It performs this function in two steps, first binding to a receptor on the surface of the host cell through interactions with the S1 region, and then fusing the viral and cellular membranes through the action of the S2 region. The location of fusion varies depending on the specific coronavirus, with some able to enter at the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

and others entering from endosome

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of the endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membra ...

s after endocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which Chemical substance, substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a Vesicle (biology and chem ...

.

Attachment

The interaction of the receptor-binding domain in the S1 region with its target receptor on the cell surface initiates the process of viral entry. Different coronaviruses target different cell-surface receptors, sometimes using sugar molecules such assialic acid

Sialic acids are a class of alpha-keto acid sugars with a nine-carbon backbone.

The term "sialic acid" () was first introduced by Swedish biochemist Gunnar Blix in 1952. The most common member of this group is ''N''-acetylneuraminic acid ...

s, or forming protein-protein interactions with proteins exposed on the cell surface. Different coronaviruses vary widely in their target receptor, although some such as SARS-CoV-1

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1), previously known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), is a strain (biology), strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the ...

and HCoV-NL63 use the same receptor despite having widely divergent spike proteins (21% amino acid identity, and only 14% in the RBD

RBD was a Mexican Latin pop group that gained popularity from Televisa's telenovela ''Rebelde'' (2004–2006). It was composed of Anahí, Dulce María, Maite Perroni, Alfonso Herrera, Christopher von Uckermann and Christian Chávez. The group ac ...

). The presence of a target receptor that S1 can bind is a determinant of host range

In biology and medicine, a host is a larger organism that harbours a smaller organism; whether a parasite, parasitic, a mutualism (biology), mutualistic, or a commensalism, commensalist ''guest'' (symbiont). The guest is typically provided with ...

and cell tropism

Endothelial cell tropism or endotheliotropism is a type of tissue tropism or host tropism that characterizes an pathogen's ability to recognize and infect an endothelial cell. Pathogens, such as viruses, can target a specific tissue type or multipl ...

. Human serum albumin binds to the S1 region, competing with ACE2 and therefore restricting viral entry into cells.

Proteolytic cleavage

Proteolytic cleavage

Proteolysis is the breakdown of proteins into smaller polypeptides or amino acids. Protein degradation is a major regulatory mechanism of gene expression and contributes substantially to shaping mammalian proteomes. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis o ...

of the spike protein, sometimes known as "priming", is required for membrane fusion. Relative to other class I fusion proteins, this process is complex and requires two cleavages at different sites, one at the S1/S2 boundary and one at the S2' site to release the fusion peptide

Membrane fusion proteins (not to be confused with chimeric or fusion proteins) are proteins that cause fusion of biological membranes. Membrane fusion is critical for many biological processes, especially in eukaryotic development and viral entry ...

. Coronaviruses vary in which part of the viral life cycle these cleavages occur, particularly the S1/S2 cleavage. Many coronaviruses are cleaved at S1/S2 before viral exit from the virus-producing cell, by furin and other proprotein convertase

Proprotein convertases (PPCs) are a family of proteins that activate other proteins. Many proteins are inactive when they are first synthesized, because they contain chains of amino acids that block their activity. Proprotein convertases remove tho ...

s; in SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

a polybasic furin cleavage site is present at this position. Others may be cleaved by extracellular proteases such as elastase

In molecular biology, elastase is an enzyme from the class of proteases (peptidases) that break down proteins, specifically one that can break down elastin. In other words, the name only refers to the substrate specificity (i.e. what proteins i ...

, by proteases located on the cell surface after receptor binding, or by proteases found in lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

s after endocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which Chemical substance, substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a Vesicle (biology and chem ...

. The specific proteases responsible for this cleavage depends on the virus, cell type, and local environment. In SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

, the serine protease

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Serin ...

TMPRSS2

Transmembrane protease, serine 2 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''TMPRSS2'' gene. It belongs to the TMPRSS family of proteins, whose members are transmembrane proteins which have a serine protease activity. The TMPRSS2 protein is ...

is important for this process, with additional contributions from cysteine protease

Cysteine proteases, also known as thiol proteases, are hydrolase enzymes that degrade proteins. These proteases share a common catalytic mechanism that involves a nucleophilic cysteine thiol in a catalytic triad or dyad.

Discovered by Gopal Chu ...

s cathepsin B and cathepsin L in endosomes. Trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

and trypsin-like proteases have also been reported to contribute. In SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

, TMPRSS2 is the primary protease for S2' cleavage, and its presence is reported to be essential for viral infection, with cathepsin L protease being functional, but not essential.

Membrane fusion

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein in its pre-fusion conformation is in a

Like other class I fusion proteins, the spike protein in its pre-fusion conformation is in a metastable

In chemistry and physics, metastability is an intermediate energetic state within a dynamical system other than the system's state of least energy.

A ball resting in a hollow on a slope is a simple example of metastability. If the ball is onl ...

state. A dramatic conformational change

In biochemistry, a conformational change is a change in the shape of a macromolecule, often induced by environmental factors.

A macromolecule is usually flexible and dynamic. Its shape can change in response to changes in its environment or othe ...

is triggered to induce the heptad repeat

The heptad repeat is an example of a structural motif that consists of a repeating pattern of seven amino acids:

''a b c d e f g''

H P P H C P C

where H represents hydrophobic residues, C represents, typically, charged residues, and P repre ...

s in the S2 region to refold into an extended six-helix bundle, causing the fusion peptide

Membrane fusion proteins (not to be confused with chimeric or fusion proteins) are proteins that cause fusion of biological membranes. Membrane fusion is critical for many biological processes, especially in eukaryotic development and viral entry ...

to interact with the cell membrane and bringing the viral and cell membranes into close proximity. Receptor binding and proteolytic cleavage (sometimes known as "priming") are required, but additional triggers for this conformational change vary depending on the coronavirus and local environment. ''In vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

'' studies of SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

suggest a dependence on calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

concentration. Unusually for coronaviruses, infectious bronchitis virus

Infectious bronchitis virus (IBV) is a species of virus from the genus ''Gammacoronavirus'' that infects birds. It causes avian infectious bronchitis, a highly infectious disease that affects the respiratory tract, gut, kidney and reproductive ...

, which infects birds, can be triggered by low pH alone; for other coronaviruses, low pH is not itself a trigger but may be required for activity of proteases, which in turn are required for fusion. The location of membrane fusion—at the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

or in endosome

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of the endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membra ...

s—may vary based on the availability of these triggers for conformational change. Fusion of the viral and cell membranes permits the entry of the virus' positive-sense RNA genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

into the host cell cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

, after which expression of viral proteins begins.

In addition to fusion of viral and host cell membranes, some coronavirus spike proteins can initiate membrane fusion between infected cells and neighboring cells, forming syncytia

A syncytium (; : syncytia; from Greek: σύν ''syn'' "together" and κύτος ''kytos'' "box, i.e. cell") or symplasm is a multinucleate cell that can result from multiple cell fusions of uninuclear cells (i.e., cells with a single nucleus), ...

. This behavior can be observed in infected cells in cell culture

Cell culture or tissue culture is the process by which cell (biology), cells are grown under controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. After cells of interest have been Cell isolation, isolated from living tissue, ...

. Syncytia have been observed in patient tissue samples from infections with SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

, MERS-CoV

Middle East respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (MERS-CoV, ''Betacoronavirus cameli'') or EMC/2012 ( HCoV-EMC/2012), is the virus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). It is a species of coronavirus which infects humans, ba ...

, and SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

, though some reports highlight a difference in syncytia formation between the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spikes attributed to sequence differences near the S1/S2 cleavage site.

Immunogenicity

Because it is exposed on the surface of the virus, the spike protein is a majorantigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

to which neutralizing antibodies are developed. Its extensive glycosylation

Glycosylation is the reaction in which a carbohydrate (or ' glycan'), i.e. a glycosyl donor, is attached to a hydroxyl or other functional group of another molecule (a glycosyl acceptor) in order to form a glycoconjugate. In biology (but not ...

can serve as a glycan

The terms glycans and polysaccharides are defined by IUPAC as synonyms meaning "compounds consisting of a large number of monosaccharides linked glycosidically". However, in practice the term glycan may also be used to refer to the carbohydrate ...

shield that hides epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The part of an antibody that binds to the epitope is called a paratope. Although e ...

s from the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

. Due to the outbreak of SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus. The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the ...

and the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, antibodies to SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

and SARS-CoV-2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‑CoV‑2) is a strain of coronavirus that causes COVID-19, the respiratory illness responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic. The virus previously had the Novel coronavirus, provisional nam ...

spike proteins have been extensively studied. Antibodies to the SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins have been identified that target epitopes on the receptor-binding domain or interfere with the process of conformational change. The majority of antibodies from infected individuals target the receptor-binding domain. More recently antibodies targeting the S2 subunit of the spike protein have been reported with broad neutralization activities against variants.

COVID-19 response

Vaccines

In response to theCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, a number of COVID-19 vaccine

A COVID19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID19).

Knowledge about the structure and fun ...

s have been developed using a variety of technologies, including mRNA vaccine

An mRNA vaccine is a type of vaccine that uses a copy of a molecule called messenger RNA (mRNA) to produce an immune response. The vaccine delivers molecules of antigen-encoding mRNA into cells, which use the designed mRNA as a blueprint to b ...

s and viral vector vaccine

A viral vector vaccine is a vaccine that uses a viral vector to deliver genetic material (DNA) that can be transcribed by the recipient's host cells as mRNA coding for a desired protein, or antigen, to elicit an immune response. , six viral vector ...

s. Most vaccine development has targeted the spike protein. Building on techniques previously used in vaccine research aimed at respiratory syncytial virus

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), also called human respiratory syncytial virus (hRSV) and human orthopneumovirus, is a virus that causes infections of the respiratory tract. It is a negative-sense, single-stranded RNA virus. Its name is derive ...

and SARS-CoV

Severe acute respiratory syndrome–related coronavirus (SARSr-CoV or SARS-CoV'', Betacoronavirus pandemicum'')The terms ''SARSr-CoV'' and ''SARS-CoV'' are sometimes used interchangeably, especially prior to the discovery of SARS-CoV-2. This m ...

, many SARS-CoV-2 vaccine development efforts have used constructs that include mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s to stabilize the spike protein's pre-fusion conformation, facilitating development of antibodies against epitope

An epitope, also known as antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, or T cells. The part of an antibody that binds to the epitope is called a paratope. Although e ...

s exposed in this conformation.

Monoclonal antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies

A monoclonal antibody (mAb, more rarely called moAb) is an antibody produced from a Lineage (evolution), cell lineage made by cloning a unique white blood cell. All subsequent antibodies derived this way trace back to a unique parent cell.

Mon ...

that target the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein have been developed as COVID-19 treatments. As of July 8, 2021, three monoclonal antibody products had received Emergency Use Authorization in the United States: bamlanivimab/etesevimab, casirivimab/imdevimab

Casirivimab/imdevimab, sold under the brand name REGEN‑COV among others, Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. is a combination medici ...

, and sotrovimab

Sotrovimab, sold under the brand name Xevudy, is a human neutralizing monoclonal antibody with activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, known as Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, SARS-CoV-2. Text was co ...

. Bamlanivimab/etesevimab was not recommended in the United States due to the increase in SARS-CoV-2 variant

Variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are viruses that, while similar to the original, have genetic changes that are of enough significance to lead virologists to label them separately. SARS-CoV-2 is the v ...

s that are less susceptible to these antibodies.

SARS-CoV-2 variants

Throughout theCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, the genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

of SARS-CoV-2 viruses was sequenced

In genetics and biochemistry, sequencing means to determine the primary structure (sometimes incorrectly called the primary sequence) of an unbranched biopolymer. Sequencing results in a symbolic linear depiction known as a sequence which succi ...

many times, resulting in identification of thousands of distinct variants

Variant may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Variant'' (magazine), a former British cultural magazine

* Variant cover, an issue of comic books with varying cover art

* ''Variant'' (novel), a novel by Robison Wells

* " The Variant", 2021 epis ...

. Many of these possess mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s that change the amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

sequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is cal ...

of the spike protein. In a World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

analysis from July 2020, the spike (''S'') gene was the second most frequently mutated in the genome, after ''ORF1ab

ORF1ab (also ORF1a/b) refers collectively to two open reading frames (ORFs), ORF1a and ORF1b, that are conserved in the genomes of nidoviruses, a group of viruses that includes coronaviruses. The genes express large polyproteins that undergo p ...

'' (which encodes most of the virus' nonstructural proteins). The evolution rate in the spike gene is higher than that observed in the genome overall. Analyses of SARS-CoV-2 genomes suggests that some sites in the spike protein sequence, particularly in the receptor-binding domain, are of evolutionary importance and are undergoing positive selection

In population genetics, directional selection is a type of natural selection in which one extreme phenotype is favored over both the other extreme and moderate phenotypes. This genetic selection causes the allele frequency to shift toward the ...

.

Spike protein mutations raise concern because they may affect infectivity

In epidemiology, infectivity is the ability of a pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be refer ...

or transmissibility, or facilitate immune escape

Antigenic escape, immune escape, immune evasion or escape mutation occurs when the immune system of a host, especially of a human being, is unable to respond to an infectious agent: the host's immune system is no longer able to recognize and elimi ...

. The mutation D614 G has arisen independently in multiple viral lineages and become dominant among sequenced genomes; it may have advantages in infectivity and transmissibility possibly due to increasing the density of spikes on the viral surface, increasing the proportion of binding-competent conformations or improving stability, but it does not affect vaccines. The mutation N501Y is common to the Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Omicron Variants of SARS-CoV-2

Variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are viruses that, while similar to the original, have genetic changes that are of enough significance to lead virologists to label them separately. SARS-CoV-2 is the v ...

and has contributed to enhanced infection and transmission, reduced vaccine efficacy, and the ability of SARS-CoV-2 to infect new rodent species. N501Y increases the affinity of spike for human ACE2 by around 10-fold, which could underlie some of fitness advantages conferred by this mutation even though the relationship between affinity and infectivity is complex. The mutation P681R alters the furin cleavage site, and has been responsible for increased infectivity, transmission and global impact of the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant

The Delta variant (B.1.617.2) was a variant of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. It was first detected in India on 5 October 2020. The Delta variant was named on 31 May 2021 and had spread to over 179 countries by 22 November 202 ...

. Mutations at position E484, particularly E484 K, have been associated with immune escape

Antigenic escape, immune escape, immune evasion or escape mutation occurs when the immune system of a host, especially of a human being, is unable to respond to an infectious agent: the host's immune system is no longer able to recognize and elimi ...

and reduced antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

binding.

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant

Omicron (B.1.1.529) is a Variants of SARS-CoV-2, variant of SARS-CoV-2 first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) by the Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa on 24 November 2021. It was first detected in Botswana and has ...

is notable for having an unusually high number of mutations in the spike protein. The SARS CoV-2 spike gene (S gene, S-gene) mutation 69–70del (Δ69-70) causes a TaqPath PCR test probe to not bind to its S gene target, leading to S gene target failure (SGTF) in SARS CoV-2 positive samples. This effect was used as a marker to monitor the propagation of the Alpha variant

The Alpha variant (B.1.1.7) was a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern. It was estimated to be 40–80% more transmissible than the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 (with most estimates occupying the middle to higher end of this range). Scientists more widel ...

and the Omicron variant

Omicron (B.1.1.529) is a Variants of SARS-CoV-2, variant of SARS-CoV-2 first reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) by the Network for Genomics Surveillance in South Africa on 24 November 2021. It was first detected in Botswana and has ...

.

Additional Key Role in Illness

In 2021, Circulation Research and Salk had a new study that proves COVID-19 can be also a vascular disease, not only respiratory disease. The scientists created an “pseudovirus”, surrounded by SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins but without any actual virus. And pseudovirus resulted in damaging lungs and arteries of animal models. It shows SARS-CoV-2 spike protein alone can cause vascular disease and could explain some covid-19 patients who suffered from strokes, or other vascular problems in other parts of human body at the same time. The team replicated the process by removing replicating capabilities of virus and showed the same damaging effect on vascular cells again.Misinformation

During theCOVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, anti-vaccination misinformation about COVID-19 circulated on social media platforms related to the spike protein's role in COVID-19 vaccine

A COVID19 vaccine is a vaccine intended to provide acquired immunity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID19).

Knowledge about the structure and fun ...

s. Spike proteins were said to be dangerously "cytotoxic

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are toxic metals, toxic chemicals, microbe neurotoxins, radiation particles and even specific neurotransmitters when the system is out of balance. Also some types of dr ...

" and mRNA vaccines containing them therefore in themselves dangerous. Spike proteins are not cytotoxic or dangerous. Spike proteins were also said to be "shed" by vaccinated people, in an erroneous allusion to the phenomenon of vaccine-induced viral shedding, which is a rare effect of live-virus vaccines unlike those used for COVID-19. "Shedding" of spike proteins is not possible.

Evolution, conservation and recombination

The class I fusion proteins, a group whose well-characterized examples include the coronavirus spike protein,influenza virus

''Orthomyxoviridae'' () is a family of negative-sense RNA viruses. It includes nine genera: '' Alphainfluenzavirus'', '' Betainfluenzavirus'', '' Gammainfluenzavirus'', '' Deltainfluenzavirus'', '' Isavirus'', '' Mykissvirus'', '' Quaranjavir ...

hemagglutinin

The term hemagglutinin (alternatively spelt ''haemagglutinin'', from the Greek , 'blood' + Latin , 'glue') refers to any protein that can cause red blood cells (erythrocytes) to clump together (" agglutinate") ''in vitro''. They do this by bindin ...

, and HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

Gp41

Gp41 also known as glycoprotein 41 is a subunit of the envelope protein complex of retroviruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Gp41 is a transmembrane protein that contains several sites within its ectodomain that are required fo ...

, are thought to be evolutionarily related. The S2 region of the spike protein responsible for membrane fusion is more highly conserved than the S1 region responsible for receptor interactions. The S1 region appears to have undergone significant diversifying selection.

Within the S1 region, the N-terminal domain (NTD) is more conserved than the C-terminal domain (CTD). The NTD's galectin-like protein fold

A protein superfamily is the largest grouping (clade) of proteins for which common ancestry can be inferred (see homology). Usually this common ancestry is inferred from structural alignment and mechanistic similarity, even if no sequence similar ...

suggests a relationship with structurally similar cellular proteins from which it may have evolved through gene capture from the host. It has been suggested that the CTD may have evolved from the NTD by gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

. The surface-exposed position of the CTD, vulnerable to the host immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

, may place this region under high selective pressure. Comparisons of the structures of different coronavirus CTDs suggests they may be under diversifying selection and in some cases, distantly related coronaviruses that use the same cell-surface receptor may do so through convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

.

References

External links

* * {{Viral proteins Coronavirus proteins Viral protein class Viral structural proteins