SMS Emden on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS ("His Majesty's Ship ") was the second and final member of the of

The 1898 Naval Law authorized the construction of thirty new

The 1898 Naval Law authorized the construction of thirty new

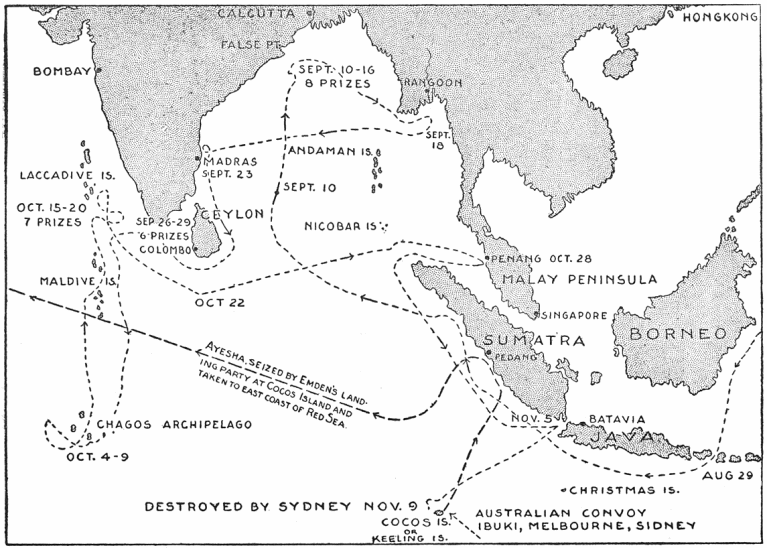

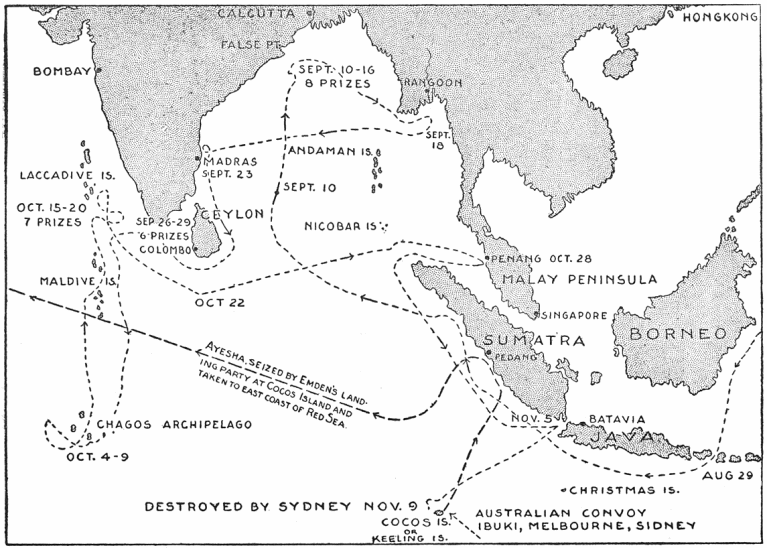

On 14 August, and left the company of the East Asia Squadron, bound for the Indian Ocean. Since the cruiser was already operating in the western Indian Ocean around the

On 14 August, and left the company of the East Asia Squadron, bound for the Indian Ocean. Since the cruiser was already operating in the western Indian Ocean around the  In late September, Müller decided to bombard Madras. Müller believed the attack would demonstrate his freedom of maneuver and decrease British prestige with the local population. At around 20:00 on 22 September, entered the port, which was completely illuminated, despite the blackout order. closed to within from the piers before opening fire. She set fire to two oil tanks and damaged three others, and damaged a merchant ship in the harbor. In the course of the bombardment, fired 130 rounds. The following day, the British again mandated that shipping stop in the Bay of Bengal; during the first month of s raiding career in the Indian Ocean, the value of exports there had fallen by 61.2 percent.

From Madras, Müller had originally intended to rendezvous with his colliers off Simalur Island in Indonesia, but instead decided to make a foray to the western side of Ceylon. On 25 September, sank the British merchantmen ''Tywerse'' and ''King Lund'' two days before capturing the collier ''Buresk'', which was carrying a cargo of high-grade coal. A German

In late September, Müller decided to bombard Madras. Müller believed the attack would demonstrate his freedom of maneuver and decrease British prestige with the local population. At around 20:00 on 22 September, entered the port, which was completely illuminated, despite the blackout order. closed to within from the piers before opening fire. She set fire to two oil tanks and damaged three others, and damaged a merchant ship in the harbor. In the course of the bombardment, fired 130 rounds. The following day, the British again mandated that shipping stop in the Bay of Bengal; during the first month of s raiding career in the Indian Ocean, the value of exports there had fallen by 61.2 percent.

From Madras, Müller had originally intended to rendezvous with his colliers off Simalur Island in Indonesia, but instead decided to make a foray to the western side of Ceylon. On 25 September, sank the British merchantmen ''Tywerse'' and ''King Lund'' two days before capturing the collier ''Buresk'', which was carrying a cargo of high-grade coal. A German

After releasing the British steamer, turned south to Simalur, and rendezvoused with the captured collier ''Buresk''. Müller then decided to attack the British coaling station in the

After releasing the British steamer, turned south to Simalur, and rendezvoused with the captured collier ''Buresk''. Müller then decided to attack the British coaling station in the  Müller made a third attempt to close to torpedo range, but ''Sydney'' quickly turned away. Shortly after 10:00, a shell from ''Sydney'' detonated ready ammunition near the starboard No. 4 gun and started a serious fire. made a fourth and final attempt to launch a torpedo attack, but ''Sydney'' was able to keep the range open. By 10:45, s guns had largely gone silent; the

Müller made a third attempt to close to torpedo range, but ''Sydney'' quickly turned away. Shortly after 10:00, a shell from ''Sydney'' detonated ready ammunition near the starboard No. 4 gun and started a serious fire. made a fourth and final attempt to launch a torpedo attack, but ''Sydney'' was able to keep the range open. By 10:45, s guns had largely gone silent; the

Over a raiding career spanning three months and , had destroyed two Entente warships and sank or captured sixteen British steamers and one Russian merchant ship, totaling . Another four British ships were captured and released, and one British and one Greek ship were used as colliers. In 1915, a Japanese company proposed that be repaired and refloated, but an inspection by the elderly flat-iron gunboat concluded that wave damage to made such an operation unfeasible. By 1919, the wreck had almost completely broken up and disappeared beneath the waves. It was eventually broken up ''

Over a raiding career spanning three months and , had destroyed two Entente warships and sank or captured sixteen British steamers and one Russian merchant ship, totaling . Another four British ships were captured and released, and one British and one Greek ship were used as colliers. In 1915, a Japanese company proposed that be repaired and refloated, but an inspection by the elderly flat-iron gunboat concluded that wave damage to made such an operation unfeasible. By 1919, the wreck had almost completely broken up and disappeared beneath the waves. It was eventually broken up ''

light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s built for the German (Imperial Navy). Named for the town of Emden

Emden () is an Independent city (Germany), independent town and seaport in Lower Saxony in the north-west of Germany and lies on the River Ems (river), Ems, close to the Germany–Netherlands border, Netherlands border. It is the main town in t ...

, she was laid down at the (Imperial Dockyard) in Danzig in 1906. The hull was launched in May 1908, and completed in July 1909. She had one sister ship, . Like the preceding cruisers, was armed with ten guns and two torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s.

spent the majority of her career overseas in the East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron () was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. It was based at Germany's Ji ...

, based in Qingdao

Qingdao, Mandarin: , (Qingdao Mandarin: t͡ɕʰiŋ˧˩ tɒ˥) is a prefecture-level city in the eastern Shandong Province of China. Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, Qingdao was long an important fortress. In 1897, the city was ceded to G ...

, in the Jiaozhou Bay Leased Territory in China. In 1913, Karl von Müller took command of the ship. At the outbreak of World War I, captured a Russian steamer and converted her into the commerce raider

Commerce raiding is a form of naval warfare used to destroy or disrupt logistics of the enemy on the open sea by attacking its merchant shipping, rather than engaging its combatants or enforcing a blockade against them. Privateering is a fo ...

. rejoined the East Asia Squadron, then was detached for independent raiding in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

. The cruiser spent nearly two months operating in the region, and captured nearly two dozen ships. On 28 October 1914, launched a surprise attack on Penang

Penang is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia along the Strait of Malacca. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay Peninsula. Th ...

; in the resulting Battle of Penang, she sank the Russian cruiser and the French destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

.

Müller then took to raid the Cocos Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (; ), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and rel ...

, where he landed a contingent of sailors to destroy British facilities. There, was attacked by the Australian cruiser on 9 November 1914. The more powerful Australian ship quickly inflicted serious damage and forced Müller to run his ship aground to avoid sinking. Out of a crew of 376, 133 were killed in the battle. Most of the survivors were taken prisoner; the landing party, led by Hellmuth von Mücke, commandeered an old schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

and eventually returned to Germany. s wreck was quickly destroyed by wave action, and was broken up for scrap in the 1950s.

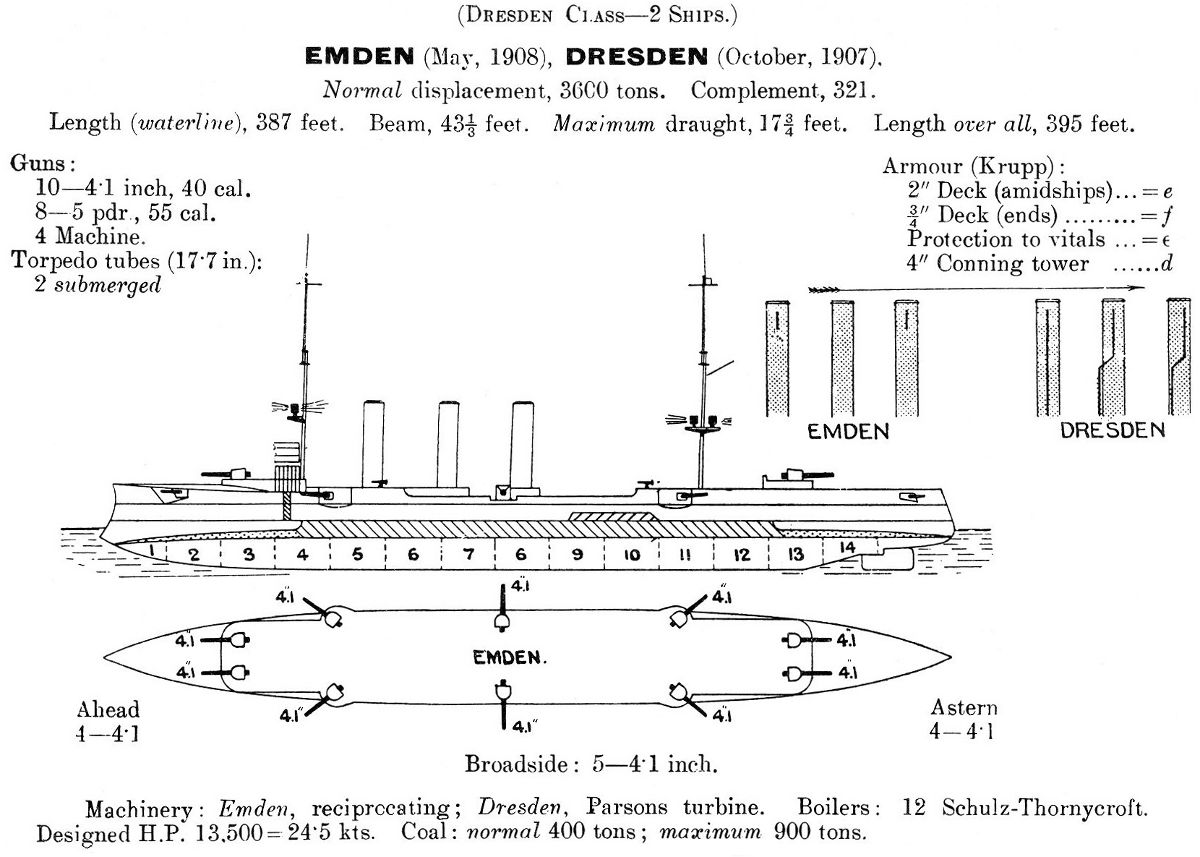

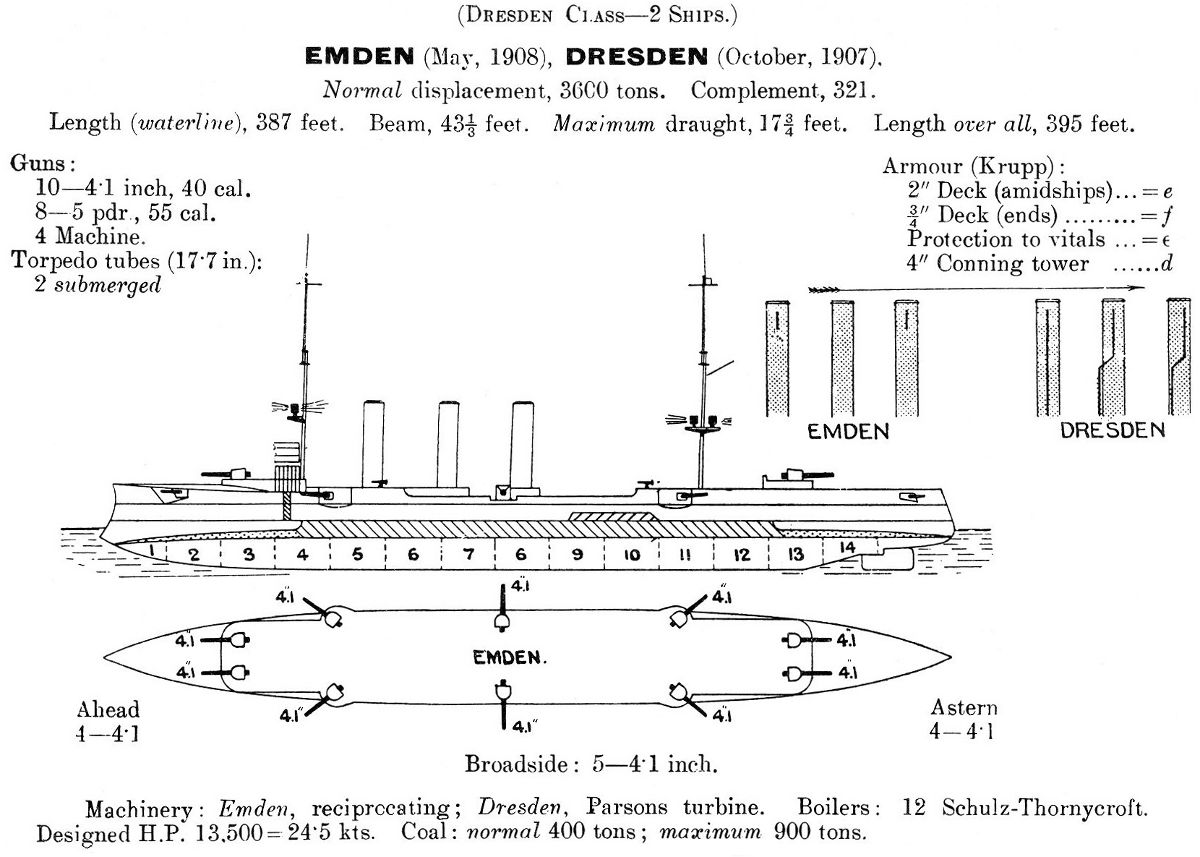

Design

The 1898 Naval Law authorized the construction of thirty new

The 1898 Naval Law authorized the construction of thirty new light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s; the program began with the , which was developed into the and es, both of which incorporated incremental improvements over the course of construction. The primary alteration for the two -class cruisers, assigned to the 1906 fiscal year, consisted of an additional boiler for the propulsion system to increase engine power.

was long overall and had a beam of and a draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of forward. She displaced as designed and up to at full load. The ship had a minimal superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, which consisted of a small conning tower and bridge

A bridge is a structure built to Span (engineering), span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or railway) without blocking the path underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, whi ...

structure. Her hull had a raised forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

and quarterdeck

The quarterdeck is a raised deck behind the main mast of a sailing ship. Traditionally it was where the captain commanded his vessel and where the ship's colours were kept. This led to its use as the main ceremonial and reception area on bo ...

, along with a pronounced ram bow

A ram on the bow of ''Olympias'', a modern reconstruction of an ancient Athenian trireme

A naval ram is a weapon fitted to varied types of ships, dating back to antiquity. The weapon comprised an underwater prolongation of the bow of the sh ...

. She was fitted with two pole masts. She had a crew of 18 officers and 343 enlisted men.

Her propulsion system consisted of two triple-expansion steam engines drove a pair of screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

s. Steam was provided by twelve coal-fired Marine-type water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s that were vented through three funnels

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

. The propulsion system was designed to give for a top speed of . carried up to of coal, which gave a range of at . was the last German cruiser to be equipped with triple-expansion engines; all subsequent cruisers used the more powerful steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s.

The ship's main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

comprised ten SK L/40 guns in single pivot mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle; six were located on the broadside, three on either side; and two were placed side by side aft. The guns could engage targets out to , and were supplied with 1,500 rounds of ammunition, 150 per gun. The secondary armament consisted of eight SK L/55 guns, also in single mounts. She had two torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s with four torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

es, mounted below the waterline, and could carry fifty naval mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel mine, anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are ...

s.

The ship was protected by a curved armored deck that was up to thick. It sloped downward at the sides of the hull to provide defense against incoming fire; the sloped portion was thick. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

had thick sides, and the guns were protected by thick gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun, automatic grenade launcher, or artillery pie ...

s.

Service history

The contract for , ordered as (replacement) , was placed on 6 April 1906 at the (Imperial Dockyard) in Danzig. Her keel was laid down on 1 November 1906. She was launched on 26 May 1908 and christened by the (Lord Mayor) of the city ofEmden

Emden () is an Independent city (Germany), independent town and seaport in Lower Saxony in the north-west of Germany and lies on the River Ems (river), Ems, close to the Germany–Netherlands border, Netherlands border. It is the main town in t ...

, Dr. Leo Fürbringer

Leo is the Latin word for lion. It most often refers to:

* Leo (constellation), a constellation of stars in the night sky

* Leo (astrology), an astrological sign of the zodiac

* Leo (given name), a given name in several languages, usually mas ...

. After fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work was completed by 10 July 1909, she was commissioned into the fleet. The new cruiser began sea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s that day but interrupted them from 11 August to 5 September to participate in the annual autumn maneuvers of the main fleet. During this period, also escorted the imperial yacht with Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty ...

aboard. was decommissioned in September after completing trials.

On 1 April 1910 was reactivated and assigned to the (East Asia Squadron), based at Qingdao

Qingdao, Mandarin: , (Qingdao Mandarin: t͡ɕʰiŋ˧˩ tɒ˥) is a prefecture-level city in the eastern Shandong Province of China. Located on China's Yellow Sea coast, Qingdao was long an important fortress. In 1897, the city was ceded to G ...

in Germany's Jiaozhou Bay Leased Territory in China. The concession had been seized in 1897 in retaliation for the murder of German nationals in the area. left Kiel

Kiel ( ; ) is the capital and most populous city in the northern Germany, German state of Schleswig-Holstein. With a population of around 250,000, it is Germany's largest city on the Baltic Sea. It is located on the Kieler Förde inlet of the Ba ...

on 12 April 1910, bound for Asia by way of a goodwill tour of South America. A month later, on 12 May, she stopped in Montevideo

Montevideo (, ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Uruguay, largest city of Uruguay. According to the 2023 census, the city proper has a population of 1,302,954 (about 37.2% of the country's total population) in an area of . M ...

and met with the cruiser , which was assigned to the (East American) Station. and stayed in Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, controlled by the government of the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires, is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Argentina. It is located on the southwest of the Río de la Plata. Buenos Aires is classified as an Alpha− glob ...

from 17 to 30 May to represent Germany at the celebrations of the hundredth anniversary of Argentinian independence. The two ships then rounded Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

; stopped in Valparaíso

Valparaíso () is a major city, Communes of Chile, commune, Port, seaport, and naval base facility in the Valparaíso Region of Chile. Valparaíso was originally named after Valparaíso de Arriba, in Castilla–La Mancha, Castile-La Mancha, Spain ...

, Chile, while continued on to Peru.

The cruise across the Pacific was delayed because of a lack of good quality coal. eventually took on around of coal at the Chilean naval base at Talcahuano

Talcahuano () (From Mapudungun ''Tralkawenu'', "Thundering Sky") is a port city and commune in the Biobío Region of Chile. It is part of the Greater Concepción conurbation. Talcahuano is located in the south of the Central Zone of Chile.

...

and departed on 24 June. The cruise was used to evaluate the ship on long-distance voyages for use in future light cruiser designs. encountered unusually severe weather on the trip, which included a stop at Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

. She anchored at Papeete

Papeete (Tahitian language, Tahitian: ''Papeʻetē'', pronounced ; old name: ''Vaiʻetē''Personal communication with Michael Koch in ) is the capital city of French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of the France, French Republic in the Pacific ...

, Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian language, Tahitian , ; ) is the largest island of the Windward Islands (Society Islands), Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia, an overseas collectivity of France. It is located in the central part of t ...

to coal on 12 July, as the bunkers were nearly empty after crossing . The ship then proceeded to Apia

Apia () is the Capital (political), capital and largest city of Samoa. It is located on the central north coast of Upolu, Samoa's second-largest island. Apia falls within the political district (''itūmālō'') of Tuamasaga.

The Apia Urban A ...

in German Samoa

German Samoa officially Malo Kaisalika / Kingdom of Samoa (; Samoan: ''Malo Kaisalika'') was a German protectorate from 1900 to 1920, consisting of the islands of Upolu, Savai'i, Apolima and Manono, now wholly within the Independent State ...

, arriving on 22 July. There, she met the rest of the East Asia Squadron, commanded by (Rear Admiral) Erich Gühler

The given name Eric, Erich, Erikk, Erik, Erick, Eirik, or Eiríkur is derived from the Old Norse name ''Eiríkr'' (or ''Eríkr'' in Old East Norse due to monophthongization).

The first element, ''ei-'' may be derived from the older Proto-Nor ...

. The squadron remained in Samoa until October, when the ships returned to their base at Qingdao. was sent to the Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ) is the longest river in Eurasia and the third-longest in the world. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows including Dam Qu River the longest source of the Yangtze, i ...

from 27 October to 19 November, which included a visit to Hankou

Hankou, alternately romanized as Hankow (), was one of the three towns (the other two were Wuchang and Hanyang) merged to become modern-day Wuhan city, the capital of the Hubei province, China. It stands north of the Han and Yangtze Rivers w ...

. The ship visited Nagasaki

, officially , is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese, the port of Portuguese_Nagasaki, Nagasaki became the sole Nanban trade, port used for tr ...

, Japan, before returning to Qingdao on 22 December for an annual refit. The repair work was not carried out; the Sokehs Rebellion erupted on Ponape in the Carolines, which required s presence; she departed Qingdao on 28 December, and left Hong Kong to join her.

The two cruisers reinforced German forces at Ponape, which included the old unprotected cruiser

An unprotected cruiser was a type of naval warship that was in use during the early 1870s Victorian era, Victorian or Pre-dreadnought battleship, pre-dreadnought era (about 1880 to 1905). The name was meant to distinguish these ships from “p ...

. The ships bombarded rebel positions and sent a landing force, which included men from the ships along with colonial police troops, ashore in mid-January 1911. By the end of February the revolt had been suppressed, and on 26 February the unprotected cruiser arrived to take over the German presence in the Carolines. and the other ships held a funeral the following day for those killed in the operation, before departing on 1 March for Qingdao via Guam. After arriving on 19 March, she began an annual overhaul. In mid-1911, the ship went on a cruise to Japan, where she accidentally rammed a Japanese steamer during a typhoon

A typhoon is a tropical cyclone that develops between 180° and 100°E in the Northern Hemisphere and which produces sustained hurricane-force winds of at least . This region is referred to as the Northwestern Pacific Basin, accounting for a ...

. The collision caused damage necessitating another trip to the drydock in Qingdao. She returned to the Yangtze to protect Europeans during the Chinese Revolution that broke out on 10 October. In November, (Vice Admiral) Maximilian von Spee replaced Gühler as the commander of the East Asia Squadron.

At the end of the year, won the Kaiser's (Shooting Prize) for excellent gunnery in the East Asia Squadron. In early December, steamed to Incheon

Incheon is a city located in northwestern South Korea, bordering Seoul and Gyeonggi Province to the east. Inhabited since the Neolithic, Incheon was home to just 4,700 people when it became an international port in 1883. As of February 2020, ...

to assist the grounded German steamer . In May 1913, (Lieutenant Commander) Karl von Müller became the ship's commanding officer; he was soon promoted to (Commander). In mid-June, went on a cruise to the German colonies in the Central Pacific, and was stationed off Nanjing

Nanjing or Nanking is the capital of Jiangsu, a province in East China. The city, which is located in the southwestern corner of the province, has 11 districts, an administrative area of , and a population of 9,423,400.

Situated in the Yang ...

, as fighting between Qing and revolutionary forces raged there. On 26 August, rebels attacked the ship, and s gunners immediately returned fire, silencing the attackers. moved to Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

on 14 August.

World War I

spent the first half of 1914 on the normal routine of cruises in Chinese and Japanese waters without incident. During theJuly Crisis

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the Great power, major powers of Europe in mid-1914, Causes of World War I, which led to the outbreak of World War I. It began on 28 June 1914 when the Serbs ...

that followed the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, was the only German cruiser in Qingdao; Spee's two armored cruiser

The armored cruiser was a type of warship of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was designed like other types of cruisers to operate as a long-range, independent warship, capable of defeating any ship apart from a pre-dreadnought battles ...

s, and , were cruising in the South Pacific and was en route to replace off the coast of Mexico. On 31 July, with war days away, Müller put to sea to begin commerce raiding once war had been formally declared. Two days later, on 2 August, Germany declared war on Russia, and the following day, captured the Russian steamer . The Russian vessel was sent back to Qingdao, and converted into the auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

.

On 5 August, Spee ordered Müller to join him at Pagan Island in the Mariana Islands

The Mariana Islands ( ; ), also simply the Marianas, are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, between the 12th and 21st pa ...

; left Qingdao the following day along with the auxiliary cruiser and the collier . The ships arrived in Pagan on 12 August. The next day, Spee learned that Japan would enter the war on the side of the Triple Entente

The Triple Entente (from French meaning "friendship, understanding, agreement") describes the informal understanding between the Russian Empire, the French Third Republic, and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It was built upon th ...

and had dispatched a fleet to track his squadron down. Spee decided to take the East Asia Squadron to South America, where it could attempt to break through to Germany, harassing British merchant traffic along the way. Müller suggested that one cruiser be detached for independent operations in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, since the squadron would be unable to attack British shipping while it was crossing the Pacific. Spee agreed, and allowed Müller to operate independently, since was the fastest cruiser in the squadron.

Independent raider

On 14 August, and left the company of the East Asia Squadron, bound for the Indian Ocean. Since the cruiser was already operating in the western Indian Ocean around the

On 14 August, and left the company of the East Asia Squadron, bound for the Indian Ocean. Since the cruiser was already operating in the western Indian Ocean around the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

, Müller decided he should cruise in the shipping lanes between Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

and Aden

Aden () is a port city located in Yemen in the southern part of the Arabian peninsula, on the north coast of the Gulf of Aden, positioned near the eastern approach to the Red Sea. It is situated approximately 170 km (110 mi) east of ...

. steamed toward the Indian Ocean by way of the Molucca

The Maluku Islands ( ; , ) or the Moluccas ( ; ) are an archipelago in the eastern part of Indonesia. Tectonically they are located on the Halmahera Plate within the Molucca Sea Collision Zone. Geographically they are located in West Melanesi ...

and Banda Sea

The Banda Sea (, , ) is one of four seas that surround the Maluku Islands of Indonesia, connected to the Pacific Ocean, but surrounded by hundreds of islands, including Timor, as well as the Halmahera Sea, Halmahera and Ceram Seas. It is about ...

s. While seeking to coal off Jampea Island, the Dutch coastal defense ship stopped and asserted Dutch neutrality. Müller steamed into the Lombok Strait

The Lombok Strait () is a strait of the Bali Sea connecting to the Indian Ocean, and is located between the islands of Bali and Lombok in Indonesia. The Gili Islands are on the Lombok side.

Its narrowest point is at its southern opening, with a ...

. There, s radio-intercept officers picked up messages from the British armored cruiser . To maintain secrecy, s crew rigged up a dummy funnel to impersonate a British light cruiser, then steamed up the coast of Sumatra

Sumatra () is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the list of islands by area, sixth-largest island in the world at 482,286.55 km2 (182,812 mi. ...

toward the Indian Ocean.

On 5 September, entered the Bay of Bengal

The Bay of Bengal is the northeastern part of the Indian Ocean. Geographically it is positioned between the Indian subcontinent and the Mainland Southeast Asia, Indochinese peninsula, located below the Bengal region.

Many South Asian and Southe ...

, achieving complete surprise, since the British assumed she was still with Spee's squadron. She operated on shipping routes there without success, until 10 September, when she moved to the Colombo–Calcutta

Kolkata, also known as Calcutta (List of renamed places in India#West Bengal, its official name until 2001), is the capital and largest city of the Indian States and union territories of India, state of West Bengal. It lies on the eastern ba ...

route. There, she captured the Greek collier , which was carrying equipment for the British. Müller took the ship into his service and agreed to pay the crew. captured five more ships; troop transports ''Indus'' and ''Lovat'' and two other ships were sunk, and the fifth, a steamer named ''Kabinga'', was used to carry the crews from the other vessels. On 13 September, Müller released ''Kabinga'' and sank two more British prizes. Off the Ganges

The Ganges ( ; in India: Ganga, ; in Bangladesh: Padma, ). "The Ganges Basin, known in India as the Ganga and in Bangladesh as the Padma, is an international which goes through India, Bangladesh, Nepal and China." is a trans-boundary rive ...

estuary, caught a Norwegian merchantman, which the Germans searched; finding no contraband

Contraband (from Medieval French ''contrebande'' "smuggling") is any item that, relating to its nature, is illegal to be possessed or sold. It comprises goods that by their nature are considered too dangerous or offensive in the eyes of the leg ...

they released her. The Norwegians informed Müller that Entente warships were operating in the area, which persuaded him to return to the eastern coast of India.

stopped and released an Italian freighter, whose crew relayed news of the incident to a British vessel, which in turn informed British naval authorities in the region. The result was an immediate cessation of shipping and the institution of a blackout. Vice Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

Martyn Jerram ordered ''Hampshire'', , and the Japanese protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

to search for . The British armored cruiser and the Japanese armored cruiser were sent to patrol likely coaling stations.

In late September, Müller decided to bombard Madras. Müller believed the attack would demonstrate his freedom of maneuver and decrease British prestige with the local population. At around 20:00 on 22 September, entered the port, which was completely illuminated, despite the blackout order. closed to within from the piers before opening fire. She set fire to two oil tanks and damaged three others, and damaged a merchant ship in the harbor. In the course of the bombardment, fired 130 rounds. The following day, the British again mandated that shipping stop in the Bay of Bengal; during the first month of s raiding career in the Indian Ocean, the value of exports there had fallen by 61.2 percent.

From Madras, Müller had originally intended to rendezvous with his colliers off Simalur Island in Indonesia, but instead decided to make a foray to the western side of Ceylon. On 25 September, sank the British merchantmen ''Tywerse'' and ''King Lund'' two days before capturing the collier ''Buresk'', which was carrying a cargo of high-grade coal. A German

In late September, Müller decided to bombard Madras. Müller believed the attack would demonstrate his freedom of maneuver and decrease British prestige with the local population. At around 20:00 on 22 September, entered the port, which was completely illuminated, despite the blackout order. closed to within from the piers before opening fire. She set fire to two oil tanks and damaged three others, and damaged a merchant ship in the harbor. In the course of the bombardment, fired 130 rounds. The following day, the British again mandated that shipping stop in the Bay of Bengal; during the first month of s raiding career in the Indian Ocean, the value of exports there had fallen by 61.2 percent.

From Madras, Müller had originally intended to rendezvous with his colliers off Simalur Island in Indonesia, but instead decided to make a foray to the western side of Ceylon. On 25 September, sank the British merchantmen ''Tywerse'' and ''King Lund'' two days before capturing the collier ''Buresk'', which was carrying a cargo of high-grade coal. A German prize crew

A prize crew is the selected members of a ship chosen to take over the operations of a captured ship. History

Prize crews were required to take their prize to appropriate prize courts, which would determine whether the ship's officers and crew h ...

went aboard ''Buresk'' which was used to support s operations. Later that day, the German raider sank the British vessels ''Ryberia'' and ''Foyle''. Low on fuel, proceeded to the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives, and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in South Asia located in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, abou ...

, arriving on 29 September and remaining for a day while coal stocks were replenished. The raider then cruised the routes between Aden and Australia and between Calcutta and Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

for two days without success. steamed to Diego Garcia

Diego Garcia is the largest island of the Chagos Archipelago. It has been used as a joint UK–U.S. military base since the 1970s, following the expulsion of the Chagossians by the UK government. The Chagos Islands are set to become a former B ...

for engine maintenance and to rest the crew.

The British garrison at Diego Garcia had not yet learned of the state of war between Britain and Germany, and so treated to a warm reception. She remained there until 10 October, to remove fouling

Fouling is the accumulation of unwanted material on solid surfaces. The fouling materials can consist of either living organisms (biofouling, organic) or a non-living substance (inorganic). Fouling is usually distinguished from other surfac ...

. While searching for merchant ships west of Colombo, picked up ''Hampshire''s wireless signals again; the ship had departed for the Chagos Archipelago

The Chagos Archipelago (, ) or Chagos Islands (formerly , and later the Oil Islands) is a group of seven atolls comprising more than 60 islands in the Indian Ocean about south of the Maldives archipelago. This chain of islands is the southernmo ...

on 13 October. The British had captured on 12 October, depriving of a collier. On 15 October, captured the British steamer ''Benmore'' off Minikoi and sank her the next day. Over the next five days, she captured ''Troiens'', ''Exfort'', ''Graycefale'', ''Sankt Eckbert'', and ''Chilkana''. One was used as a collier, three were sunk, and the fifth was sent to port with the crews of the other vessels. On 20 October, Müller decided to move to a new area of operations.

Attack on Penang

Müller planned a surprise attack onPenang

Penang is a Malaysian state located on the northwest coast of Peninsular Malaysia along the Strait of Malacca. It has two parts: Penang Island, where the capital city, George Town, is located, and Seberang Perai on the Malay Peninsula. Th ...

in British Malaya

The term "British Malaya" (; ) loosely describes a set of states on the Malay Peninsula and the island of Singapore that were brought under British Empire, British hegemony or control between the late 18th and the mid-20th century. Unlike the ...

. coaled in the Nicobar Islands

The Nicobar Islands are an archipelago, archipelagic island chain in the eastern Indian Ocean. They are located in Southeast Asia, northwest of Aceh on Sumatra, and separated from Thailand to the east by the Andaman Sea. Located southeast of t ...

and departed for Penang on the night of 27 October, with the departure timed to arrive off the harbor at dawn. She approached the harbor entrance at 03:00 on 28 October, steaming at , with the fourth dummy funnel erected to disguise her identity. s lookouts quickly spotted a warship in the port with lights on; it turned out to be the Russian protected cruiser , a veteran of the Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known in Japan as the , was the final naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 27–28 May 1905 in the Tsushima Strait. A devastating defeat for the Imperial Russian Navy, the ...

. had put into Penang for boiler repairs; only one was in service, which meant that she could not get under way, nor were the ammunition hoists powered. Only five rounds of ready ammunition were permitted for each gun, with a sixth chambered. pulled alongside at a distance of ; Müller ordered a torpedo to be fired at the Russian cruiser, then gave the order for the 10.5 cm guns to open fire.

quickly inflicted grievous damage on her adversary, then turned around to make another pass at . One of the Russian gun crews managed to get a weapon into action, but scored no hits. Müller ordered a second torpedo to be fired into the burning while his guns continued to batter her. The second torpedo caused a tremendous explosion that tore the ship apart. By the time the smoke cleared, had already slipped beneath the waves, the masts the only parts of the ship still above water. The destruction of killed 81 Russian sailors and wounded 129, of whom seven later died of their injuries. The elderly French torpedo cruiser and the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

opened wildly inaccurate fire on .

Müller then decided to depart, owing to the risk of encountering superior warships. Upon leaving the harbor, he encountered a British freighter, , loaded with ammunition, that had already stopped to pick up a harbor pilot

A maritime pilot, marine pilot, harbor pilot, port pilot, ship pilot, or simply pilot, is a mariner who has specific knowledge of an often dangerous or congested waterway, such as harbors or river mouths. Maritime pilots know local details s ...

. While preparing to take possession of the ship, had to recall her boats having spotted an approaching ship. This proved to be the French destroyer , which was unprepared and was quickly destroyed. stopped to pick up survivors and departed at around 08:00 as the other French ships were raising steam to get underway. One officer and thirty-five sailors were plucked from the water. Another French destroyer tried to follow, but lost sight of the German raider in a rainstorm. On 30 October, stopped the British steamer ''Newburn'' and put the French sailors aboard after they signed statements promising not to return to the war. The attack on Penang was a significant shock to the Entente powers, and caused them to delay the large convoys from Australia, since they would need more powerful escorts.

Battle of Cocos

After releasing the British steamer, turned south to Simalur, and rendezvoused with the captured collier ''Buresk''. Müller then decided to attack the British coaling station in the

After releasing the British steamer, turned south to Simalur, and rendezvoused with the captured collier ''Buresk''. Müller then decided to attack the British coaling station in the Cocos Islands

The Cocos (Keeling) Islands (), officially the Territory of Cocos (Keeling) Islands (; ), are an Australian external territory in the Indian Ocean, comprising a small archipelago approximately midway between Australia and Sri Lanka and rel ...

; he intended to destroy the wireless station there and draw away British forces searching for him in the Indian Ocean. While en route to the Cocos, spent two days combing the Sunda Strait

The Sunda Strait () is the strait between the Indonesian islands of Java island, Java and Sumatra. It connects the Java Sea with the Indian Ocean.

Etymology

The strait takes its name from the Sunda Kingdom, which ruled the western portion of Ja ...

for merchant shipping without success. She steamed to the Cocos, arriving off Direction Island at 06:00 on the morning of 9 November. Since there were no British vessels in the area, Müller sent ashore a landing party led by (First Lieutenant) Hellmuth von Mücke, s executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.

In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer ...

. The party consisted of another two officers, six non-commissioned officers, and thirty-eight sailors armed with four machine guns and thirty rifles.

was using jamming, but the British wireless station was able to transmit the message "Unidentified ship off entrance." The message was received by the Australian light cruiser , which was away, escorting a convoy. ''Sydney'' immediately headed for the Cocos Islands at top speed. picked up wireless messages from the then unidentified vessel approaching, but believed her to be away, giving them much more time than they actually had. At 09:00, lookouts aboard spotted smoke on the horizon, and thirty minutes later identified it as a warship approaching at high speed. Mücke's landing party was still ashore, and there was no time left to recover them.

''Sydney'' closed to a distance of before turning to a parallel course with . The German cruiser opened fire first, and straddled the Australian vessel with her third salvo. s gunners were firing rapidly, with a salvo every ten seconds; Müller hoped to overwhelm ''Sydney'' with a barrage of shells before her heavier armament could take effect. Two shells hit ''Sydney'', one of which disabled the aft fire control station; the other failed to explode. It took slightly longer for ''Sydney'' to find the range, and in the meantime, turned toward ''Sydney'' in an attempt to close to torpedo range. ''Sydney''s more powerful guns soon found the range and inflicted serious damage. The wireless compartment was destroyed and the crew for one of the forward guns was killed early in the engagement. At 09:45, Müller turned his ship toward ''Sydney'' in another attempt to reach a torpedo firing position. Five minutes later, a shell hit disabled the steering gear, and other fragments jammed the hand steering equipment. could only be steered with her propellers. ''Sydney''s gunfire also destroyed the rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s and caused heavy casualties amongst s gun crews.

Müller made a third attempt to close to torpedo range, but ''Sydney'' quickly turned away. Shortly after 10:00, a shell from ''Sydney'' detonated ready ammunition near the starboard No. 4 gun and started a serious fire. made a fourth and final attempt to launch a torpedo attack, but ''Sydney'' was able to keep the range open. By 10:45, s guns had largely gone silent; the

Müller made a third attempt to close to torpedo range, but ''Sydney'' quickly turned away. Shortly after 10:00, a shell from ''Sydney'' detonated ready ammunition near the starboard No. 4 gun and started a serious fire. made a fourth and final attempt to launch a torpedo attack, but ''Sydney'' was able to keep the range open. By 10:45, s guns had largely gone silent; the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

had been shredded and the two rear-most funnels had been shot away, along with the foremast. Müller realized that his ship was no longer able to fight, and beached on North Keeling Island to save the lives of his crew. At 11:15, was run onto the reef, and the engines and boilers were flooded. Her breech blocks and torpedo aiming gear were thrown overboard to render the weapons unusable, and all signal books and secret papers were burned. ''Sydney'' turned to capture the collier ''Buresk'', whose crew scuttled her when the Australian cruiser approached. ''Sydney'' then returned to the wrecked and inquired if she surrendered. The signal books had been destroyed by fire and so the Germans could not reply, and since her flag was still flying, ''Sydney'' resumed fire. The Germans quickly raised white flag

White flags have had different meanings throughout history and depending on the locale.

Contemporary use

The white flag is an internationally recognized protective sign of truce or ceasefire and for negotiation. It is also used to symboliz ...

s and the Australians ceased fire.

In the course of the action, scored sixteen hits on ''Sydney'', killing three of her crew and wounding another thirteen. A fourth crewman died later from his injuries. ''Sydney'' had meanwhile fired some 670 rounds of ammunition, with around 100 hits claimed. had suffered much higher casualties: 133 officers and enlisted men died, out of a crew of 376. Most of the surviving crew, including Müller, were taken into captivity the next day. The wounded men were sent to Australia, while the uninjured were interned at a camp in Malta

Malta, officially the Republic of Malta, is an island country in Southern Europe located in the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and North Africa. It consists of an archipelago south of Italy, east of Tunisia, and north of Libya. The two ...

; the men were returned to Germany in 1920. Mücke's landing party evaded capture. They had observed the battle, and realized that would be destroyed. Mücke therefore ordered the old 97 gross register ton schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

'' Ayesha'' to be prepared for sailing. The Germans departed before ''Sydney'' reached Direction Island, and sailed to Padang

Padang () is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Indonesian Provinces of Indonesia, province of West Sumatra. It had a population of 833,562 at the 2010 CensusBiro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011. and 909,040 at the 2020 Census;Bad ...

in the Dutch East Indies. From there, they traveled to Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

, which was then part of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, an ally of Germany. They then traveled overland to Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, arriving in June 1915. There, they reported to Wilhelm Souchon, the commander of the ex-German battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

. In the meantime, the British sloop arrived at the Cocos Islands about a week after the battle to bury the sailors killed in the battle.

Legacy

Over a raiding career spanning three months and , had destroyed two Entente warships and sank or captured sixteen British steamers and one Russian merchant ship, totaling . Another four British ships were captured and released, and one British and one Greek ship were used as colliers. In 1915, a Japanese company proposed that be repaired and refloated, but an inspection by the elderly flat-iron gunboat concluded that wave damage to made such an operation unfeasible. By 1919, the wreck had almost completely broken up and disappeared beneath the waves. It was eventually broken up ''

Over a raiding career spanning three months and , had destroyed two Entente warships and sank or captured sixteen British steamers and one Russian merchant ship, totaling . Another four British ships were captured and released, and one British and one Greek ship were used as colliers. In 1915, a Japanese company proposed that be repaired and refloated, but an inspection by the elderly flat-iron gunboat concluded that wave damage to made such an operation unfeasible. By 1919, the wreck had almost completely broken up and disappeared beneath the waves. It was eventually broken up ''in situ

is a Latin phrase meaning 'in place' or 'on site', derived from ' ('in') and ' ( ablative of ''situs'', ). The term typically refers to the examination or occurrence of a process within its original context, without relocation. The term is use ...

'' in the early 1950s by a Japanese salvage company; parts of the ship remain scattered around the area.

Following the destruction of , Kaiser Wilhelm II awarded the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, the German Empire (1871–1918), and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). The design, a black cross pattée with a white or silver outline, was derived from the in ...

to the ship and announced that a new would be built to honor the original cruiser. Wilhelm II ordered that the new cruiser wear a large Iron Cross on her bow to commemorate her namesake ship. The third cruiser to bear the name , built in the 1920s for the , also carried the Iron Cross, along with battle honors for the Indian Ocean, Penang, Cocos Islands, and Ösel

Saaremaa (; ) is the largest and most populous island in Estonia. Measuring , its population is 31,435 (as of January 2020). The main island of the West Estonian archipelago (Moonsund archipelago), it is located in the Baltic Sea, south of Hi ...

, where the second had engaged several Russian destroyers and torpedo boats. Three further vessels have been named for the cruiser in the post-war German Navy

The German Navy (, ) is part of the unified (Federal Defense), the German Armed Forces. The German Navy was originally known as the ''Bundesmarine'' (Federal Navy) from 1956 to 1995, when ''Deutsche Marine'' (German Navy) became the official ...

, two of which also carried an Iron Cross: the laid down in 1959, the laid down in 1979, and the laid down in 2020.

Three of the ship's 10.5 cm guns were removed from the wreck three years after the battle. One is preserved in Hyde Park in Sydney, a second is located at the Royal Australian Navy Heritage Centre in , the main naval base in Sydney, and the third is on display at the Australian War Memorial

The Australian War Memorial (AWM) is a national war memorial, war museum, museum and archive dedicated to all Australians who died as a result of war, including peacekeeping duties. The AWM is located in Campbell, Australian Capital Territory, C ...

in Canberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

. In addition, s bell

A bell /ˈbɛl/ () is a directly struck idiophone percussion instrument. Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator. The strike may be m ...

and stern ornament were recovered from the wreck and both are currently in the collection of the Australian War Memorial. A number of other artifacts, including a damaged 10.5 cm shell case, an iron rivet

A rivet is a permanent mechanical fastener. Before being installed, a rivet consists of a smooth cylinder (geometry), cylindrical shaft with a head on one end. The end opposite the head is called the ''tail''. On installation, the deformed e ...

from the hull, and uniforms were also recovered and are held in the Australian War Memorial.

In March 1921, the government of Prussia

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a Germans, German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussia (region), Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, ...

decreed that Prussian former crew members and relatives of those serving aboard the ship during World War I were allowed to add the heritable suffix "-Emden" to their last names as recognition for their service. Other German state governments followed suit. In March 1934, Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German military and political leader who led the Imperial German Army during the First World War and later became President of Germany (1919� ...

, who was then the president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

, decreed that relatives of those who had been killed aboard the ship could also apply for the suffix.

A number of films have been made about s wartime exploits, including the 1915 movies '' How We Beat the Emden'' and '' How We Fought the Emden'' and the 1928 '' The Exploits of the Emden'', all produced in Australia. German films include the 1926 silent film

A silent film is a film without synchronized recorded sound (or more generally, no audible dialogue). Though silent films convey narrative and emotion visually, various plot elements (such as a setting or era) or key lines of dialogue may, w ...

, footage from which was incorporated in of 1932, and , produced in 1934. All three films were directed by Louis Ralph. More recently, in 2012, (The men of the ) was released, which was made about how the crew of made their way back to Germany after the Battle of Cocos.

After the bombardment of Madras, s name, as "Amdan", entered the Sinhala and Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

languages meaning "someone who is tough, manipulative and crafty." In the Malayalam language

Malayalam (; , ) is a Dravidian language spoken in the Indian state of Kerala and the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry ( Mahé district) by the Malayali people. It is one of 22 scheduled languages of India. Malayalam wa ...

the word "Emadan" means "a big and powerful thing" or "as big as Emden".

See also

* HMAS ''Sydney'' I – SMS ''Emden'' MemorialFootnotes

Notes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Emden (1908) Dresden-class cruisers Ships built in Danzig 1908 ships World War I cruisers of Germany World War I commerce raiders Maritime incidents in November 1914 World War I shipwrecks in the Indian Ocean Shipwrecks of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands Recipients of the Iron Cross (1914) Australian Shipwrecks with protected zone