Russian battleship Potemkin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

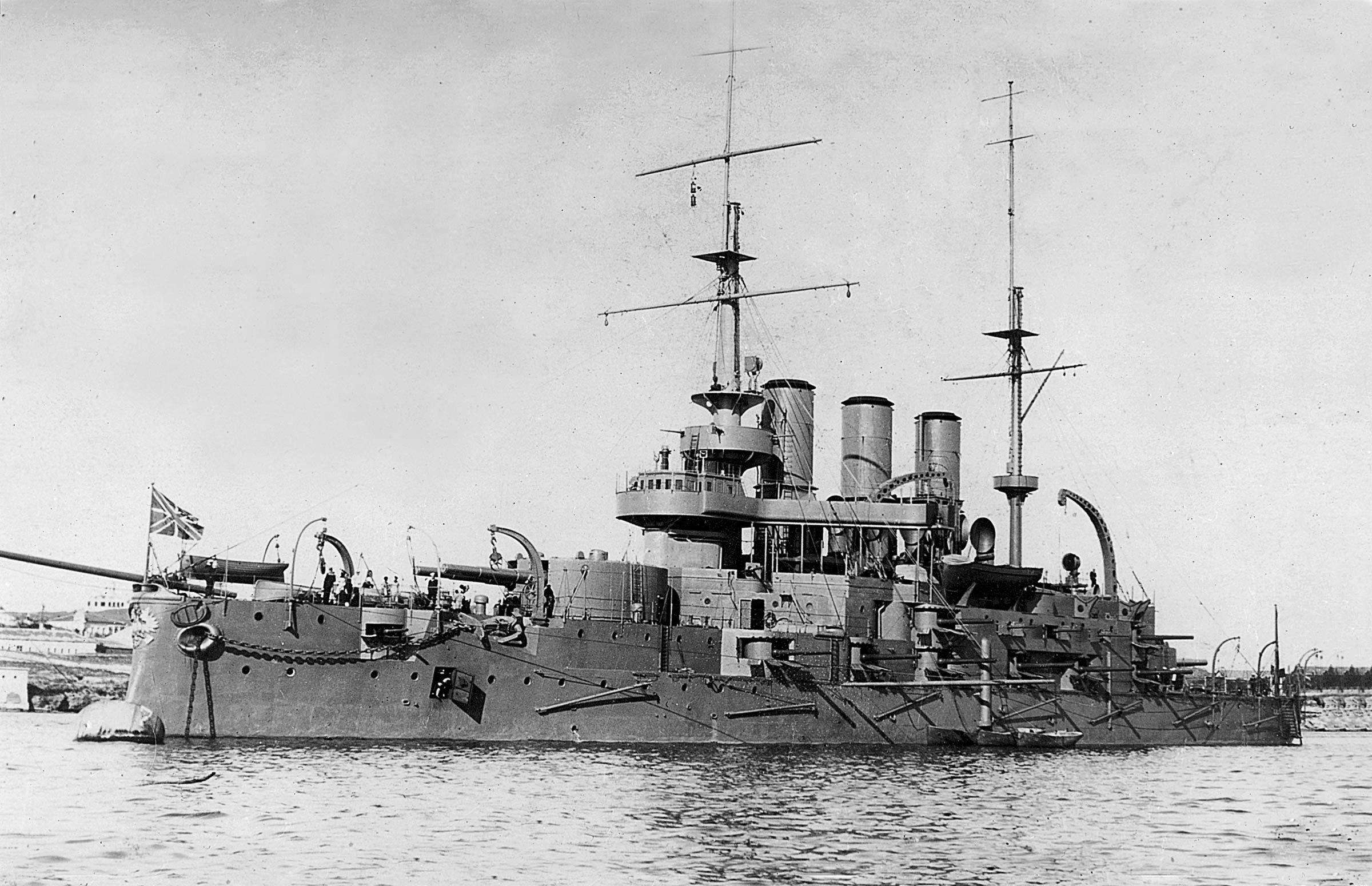

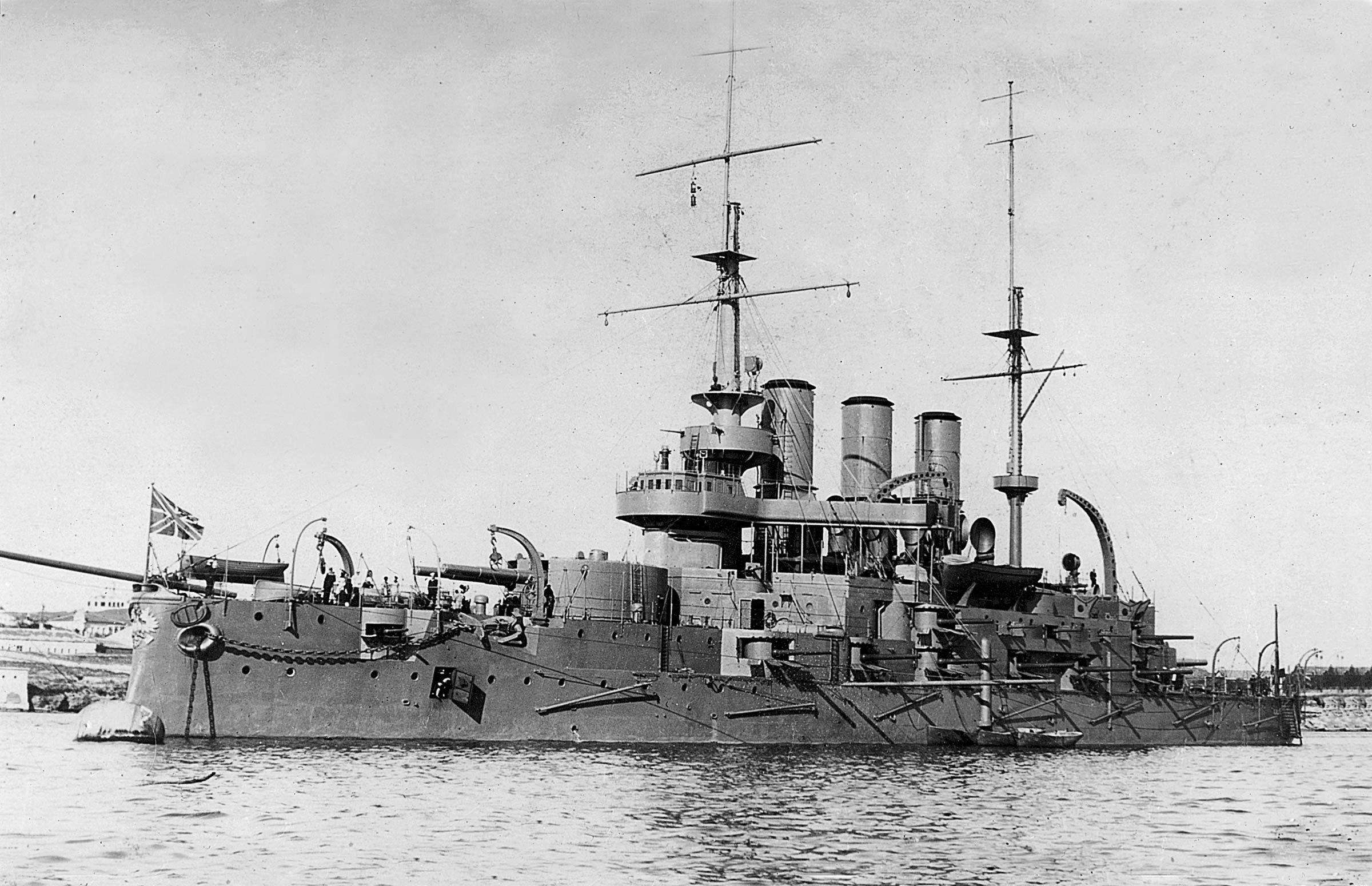

The Russian battleship ''Potemkin'' (, "Prince Potemkin of

The battleship's

The battleship's

The committee decided to head for

The committee decided to head for

Taurida

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula, historically known as ''Tauris'', ''Taurica'' (), and the ''Tauric Chersonese'' (, "Tauric Peninsula"), begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast ...

") was a pre-dreadnought battleship

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appli ...

built for the Imperial Russian Navy

The Imperial Russian Navy () operated as the navy of the Russian Tsardom and later the Russian Empire from 1696 to 1917. Formally established in 1696, it lasted until being dissolved in the wake of the February Revolution and the declaration of ...

's Black Sea Fleet

The Black Sea Fleet () is the Naval fleet, fleet of the Russian Navy in the Black Sea, the Sea of Azov and the Mediterranean Sea. The Black Sea Fleet, along with other Russian ground and air forces on the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, are subordin ...

. She became famous during the Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

, when her crew mutinied against their officers. This event later formed the basis for Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein; (11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenwriter, film editor and film theorist. Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, he was a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is no ...

's 1925 silent film '' Battleship Potemkin''.

After the mutineers sought asylum in Constanța

Constanța (, , ) is a city in the Dobruja Historical regions of Romania, historical region of Romania. A port city, it is the capital of Constanța County and the country's Cities in Romania, fourth largest city and principal port on the Black ...

, Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, and after the Russians recovered the ship, her name was changed to ''Panteleimon''. She accidentally sank a Russian submarine in 1909 and was badly damaged when she ran aground in 1911. During World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, ''Panteleimon'' participated in the Battle of Cape Sarych

The Battle of Cape Sarych was a naval engagement fought off the coast of Cape Sarych in the Black Sea during the First World War. In November 1914, two modern Ottoman Empire, Ottoman warships, specifically a light cruiser and a battlecruiser, eng ...

in late 1914. She covered several bombardments of the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

fortifications in early 1915, including one where the ship was attacked by the Ottoman battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' – ''Panteleimon'' and the other Russian pre-dreadnoughts present drove her off before she could inflict any serious damage. The ship was relegated to secondary roles after Russia's first dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

entered service in late 1915. She was by then obsolete and was reduced to reserve in 1918 in Sevastopol

Sevastopol ( ), sometimes written Sebastopol, is the largest city in Crimea and a major port on the Black Sea. Due to its strategic location and the navigability of the city's harbours, Sevastopol has been an important port and naval base th ...

.

''Panteleimon'' was captured when the Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

took Sevastopol in May 1918 and was handed over to the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

after the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

in November 1918. Her engines were destroyed by the British in 1919 when they withdrew from Sevastopol to prevent the advancing Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

from using them against the White Russians. The ship was abandoned when the Whites evacuated the Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

in 1920 and was finally scrapped by the Soviets

The Soviet people () were the citizens and nationals of the Soviet Union. This demonym was presented in the ideology of the country as the "new historical unity of peoples of different nationalities" ().

Nationality policy in the Soviet Union ...

in 1923.

Background and description

Planning began in 1895 for a new battleship that would utilise aslipway

A slipway, also known as boat ramp or launch or boat deployer, is a ramp on the shore by which ships or boats can be moved to and from the water. They are used for building and repairing ships and boats, and for launching and retrieving smal ...

slated to become available at the Nikolayev Admiralty Shipyard in 1896. The Naval Staff and the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, Vice Admiral

Vice admiral is a senior naval flag officer rank, usually equivalent to lieutenant general and air marshal. A vice admiral is typically senior to a rear admiral and junior to an admiral.

Australia

In the Royal Australian Navy, the rank of Vice ...

K. P. Pilkin, agreed on a copy of the design, but they were over-ruled by General Admiral Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich. The General Admiral decided that the long range and less powerful guns of the ''Peresvet'' class were inappropriate for the narrow confines of the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

, and ordered the design of an improved version of the battleship instead. The improvements included a higher forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

to improve the ship's seakeeping

Seakeeping ability or seaworthiness is a measure of how well-suited a watercraft is to conditions when underway. A ship or boat which has good seakeeping ability is said to be very seaworthy and is able to operate effectively even in high sea stat ...

qualities, Krupp cemented armour

Krupp armour was a type of steel naval armour used in the construction of capital ships starting shortly before the end of the nineteenth century. It was developed by Germany's Krupp Arms Works in 1893 and quickly replaced Harvey armour as the ...

and Belleville boilers. The design process was complicated by numerous changes demanded by various departments of the Naval Technical Committee. The ship's design was finally approved on 12 June 1897, although design changes continued to be made that slowed the ship's construction.

''Potemkin'' was long at the waterline and long overall. She had a beam of and a maximum draught of . The battleship displaced , more than her designed displacement of . The ship's crew consisted of 26 officers and 705 enlisted men.McLaughlin 2003, p. 116

''Potemkin'' had a pair of three-cylinder vertical triple-expansion steam engines, each of which drove one propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

, that had a total designed output of . Twenty-two Belleville boilers provided steam to the engines at a pressure of . The 8 boilers in the forward boiler room were oil-fired and the remaining 14 were coal-fired. During her sea trials on 31 October 1903, she reached a top speed of . Leaking oil caused a serious fire on 2 January 1904 that caused the navy to convert her boilers to coal firing at a cost of 20,000 ruble

The ruble or rouble (; rus, рубль, p=rublʲ) is a currency unit. Currently, currencies named ''ruble'' in circulation include the Russian ruble (RUB, ₽) in Russia and the Belarusian ruble (BYN, Rbl) in Belarus. These currencies are s ...

s. The ship carried a maximum of of coal at full load that provided a range of at a speed of .

Armament

The battleship's

The battleship's main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

consisted of four 40-calibre

In guns, particularly firearms, but not artillery, where a different definition may apply, caliber (or calibre; sometimes abbreviated as "cal") is the specified nominal internal diameter of the gun barrel bore – regardless of how or wher ...

guns mounted in twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechanis ...

s fore and aft of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

. The electrically operated turrets were derived from the design of those used by the s. These guns had a maximum elevation of +15° and their rate of fire was very slow, only one round every four minutes during gunnery trials.McLaughlin 2003, p. 119 They fired a shell at a muzzle velocity

Muzzle velocity is the speed of a projectile (bullet, pellet, slug, ball/ shots or shell) with respect to the muzzle at the moment it leaves the end of a gun's barrel (i.e. the muzzle). Firearm muzzle velocities range from approximately t ...

of . At an elevation of +10° the guns had a range of . ''Potemkin'' carried 60 rounds for each gun.

The sixteen 45-calibre, Canet Pattern 1891 quick-firing (QF) guns were mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armoured structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" ...

s. Twelve of these were placed on the sides of the hull and the other four were positioned at the corners of the superstructure. They fired shells that weighed with a muzzle velocity of . They had a maximum range of when fired at an elevation of +20°. The ship stowed 160 rounds per gun.

Smaller guns were carried for close-range defence against torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s. These included fourteen 50-calibre Canet QF guns: four in hull embrasure

An embrasure (or crenel or crenelle; sometimes called gunhole in the domain of Age of Gunpowder, gunpowder-era architecture) is the opening in a battlement between two raised solid portions (merlons). Alternatively, an embrasure can be a sp ...

s and the remaining ten mounted on the superstructure. ''Potemkin'' carried 300 shells for each gun. They fired an shell at a muzzle velocity of to a maximum range of . She also mounted six Hotchkiss gun

The Hotchkiss gun can refer to different types of the Hotchkiss arms company starting in the late 19th century. It usually refers to the 1.65-inch (42 mm) light mountain gun. There were also navy (47 mm) and 3-inch (76 mm) ...

s. Four of these were mounted in the fighting top and two on the superstructure. They fired a shell at a muzzle velocity of .

''Potemkin'' had five underwater torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s: one in the bow and two on each broadside. She carried three torpedoes for each tube. The model of torpedo in use changed over time; the first torpedo that the ship would have been equipped with was the M1904. It had a warhead

A warhead is the section of a device that contains the explosive agent or toxic (biological, chemical, or nuclear) material that is delivered by a missile, rocket (weapon), rocket, torpedo, or bomb.

Classification

Types of warheads include:

*E ...

weight of and a speed of with a maximum range of .

In 1907, telescopic sight

A telescopic sight, commonly called a scope informally, is an optical sighting device based on a refracting telescope. It is equipped with some form of a referencing pattern – known as a ''reticle'' – mounted in a focally appropriate p ...

s were fitted for the 12-inch and 6-inch guns. In that or the following year rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to Length measurement, measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, suc ...

s were installed. The bow torpedo tube was removed in 1910–1911, as was the fighting top. The following year the main-gun turret machinery was upgraded and the guns were modified to improve their rate of fire to one round every 40 seconds.McLaughlin 2003, pp. 294–295

Two anti-aircraft (AA) guns were mounted on ''Potemkin''s superstructure on 3–6 June 1915; they were supplemented by two 75 mm AA guns, one on top of each turret, probably during 1916. In February 1916, the ship's four remaining torpedo tubes were removed. At some point during World War I, her 75 mm guns were also removed.

Protection

The maximum thickness of the Krupp cemented armour waterline belt was which reduced to abreast themagazines

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

. It covered of the ship's length and plates protected the waterline to the ends of the ship. The belt was high, of which was below the waterline

The waterline is the line where the hull of a ship meets the surface of the water.

A waterline can also refer to any line on a ship's hull that is parallel to the water's surface when the ship is afloat in a level trimmed position. Hence, wate ...

, and tapered down to a thickness of at its bottom edge. The main part of the belt terminated in transverse bulkheads.

Above the belt was the upper strake

On a vessel's Hull (watercraft), hull, a strake is a longitudinal course of Plank (wood), planking or Plate (metal), plating which runs from the boat's stem (ship), stempost (at the Bow (ship), bows) to the stern, sternpost or transom (nautica ...

of six-inch armour that was long and closed off by six-inch transverse bulkheads fore and aft. The upper casemate protected the six-inch guns and was five inches thick on all sides. The sides of the turrets were thick and they had a two-inch roof. The conning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

's sides were nine inches thick. The nickel-steel armour deck was two inches thick on the flat amidships, but thick on the slope connecting it to the armour belt. Fore and aft of the armoured citadel, the deck was to the bow and stern. In 1910–1911, additional armour plates were added fore and aft; their exact location is unknown, but they were probably used to extend the height of the two-inch armour strake at the ends of the ship.

Construction and career

Construction of ''Potemkin'' began on 27 December 1897 and she waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the Nikolayev Admiralty Shipyard on 10 October 1898. She was named in honour of Prince Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (A number of dates as late as 1742 have been found on record; the veracity of any one is unlikely to be proved. This is his "official" birth-date as given on his tombstone.) was a Russian mi ...

, a Russian soldier and statesman. The ship was launched on 9 October 1900 and transferred to Sevastopol for fitting out on 4 July 1902. She began sea trial

A sea trial or trial trip is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a "shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on op ...

s in September 1903 and these continued, off and on, until early 1905 when her gun turrets were completed.

Mutiny

During theRusso-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

of 1904–1905, many of the Black Sea Fleet's most experienced officers and enlisted men were transferred to the ships in the Pacific to replace losses. This left the fleet with primarily raw recruits and less capable officers. With the news of the disastrous Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known in Japan as the , was the final naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 27–28 May 1905 in the Tsushima Strait. A devastating defeat for the Imperial Russian Navy, the ...

in May 1905, morale dropped to an all-time low, and any minor incident could be enough to spark a major catastrophe. Taking advantage of the situation, plus the disruption caused by the ongoing riots and uprisings, the Central Committee of the Social Democratic Organisation of the Black Sea Fleet, called "Tsentralka", had started preparations for a simultaneous mutiny

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, ...

on all of the ships of the fleet, although the timing had not been decided.

On 27 June 1905, ''Potemkin'' was at gunnery practice near Tendra Spit off the Ukrainian coast when many enlisted men refused to eat the borscht

Borscht () is a sour soup, made with meat stock, vegetables and seasonings, common in Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. In English, the word ''borscht'' is most often associated with the soup's variant of Ukrainian origin, made with red b ...

made from rotten meat infested with maggot

A maggot is the larva of a fly (order Diptera); it is applied in particular to the larvae of Brachycera flies, such as houseflies, cheese flies, hoverflies, and blowflies, rather than larvae of the Nematocera, such as mosquitoes and cr ...

s. Brought aboard the warship the previous day from shore suppliers, the carcasses had been passed as suitable for eating by the ship's senior surgeon Dr Sergei Smirnov after several perfunctory examinations.

The uprising was triggered when Ippolit Giliarovsky, the ship's second in command, allegedly threatened to shoot crew members for their refusal. He summoned the ship's marine guards as well as a tarpaulin

A tarpaulin ( , ) or tarp is a large sheet of strong, flexible, water-resistant or waterproof material, often cloth such as canvas or polyester coated with polyurethane, or made of plastics such as polyethylene. Tarpaulins often have reinf ...

to protect the ship's deck from any blood in an attempt to intimidate the crew. Giliarovsky was killed after he mortally wounded Grigory Vakulinchuk, one of the mutiny's leaders. The mutineers killed seven of the ''Potemkin''s eighteen officers, including Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Evgeny Golikov ( ru), Executive Officer Giliarovsky and Surgeon Smirnov; and captured the accompanying torpedo boat (No. 267). They organised a ship's committee of 25 sailors, led by Afanasi Matushenko

Afanasy Nikolayevich Matushenko (; ; 2 May 1879 – ) was a Russian sailor. He was a non-commissioned officer in the Black Sea Fleet, revolutionary socialist, and ringleader of the mutiny on the Russian battleship Potemkin, Russian battleship ''P ...

, to run the battleship.

The committee decided to head for

The committee decided to head for Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

flying a red flag and arrived there later that day at 22:00. A general strike

A general strike is a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large coalitions ...

had been called in the city and there was some rioting as police tried to quell the strikers. The following day the mutineers refused to supply a landing party to help the striking revolutionaries take over the city, preferring instead to await the arrival of the other battleships of the Black Sea Fleet. Later that day the mutineers aboard ''Potemkin'' captured a military transport, '' Vekha'', that had arrived in the city. The riots continued as much of the port area was destroyed by fire. On the afternoon of 29 June, Vakulinchuk's funeral turned into a political demonstration and the army attempted to ambush the sailors who participated in the funeral. In retaliation, ''Potemkin'' fired two six-inch shells at the theatre where a high-level military meeting was scheduled to take place, but missed.

Vice Admiral Grigoriy Chukhnin, commander of the Black Sea Fleet, issued an order to send two squadrons to Odessa either to force ''Potemkin''s crew to give up or sink the battleship. ''Potemkin'' sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warf ...

d on the morning of 30 June to meet the three battleships ''Tri Sviatitelia'', , and of the first squadron, but the loyal ships turned away. The second squadron arrived with the battleships and later that morning, and Vice Admiral Aleksander Krieger, acting commander of the Black Sea Fleet, ordered the ships to proceed to Odessa. ''Potemkin'' sortied again and sailed through the combined squadrons as Krieger failed to order his ships to fire. Captain Kolands of ''Dvenadsat Apostolov'' attempted to ram

Ram, ram, or RAM most commonly refers to:

* A male sheep

* Random-access memory, computer memory

* Ram Trucks, US, since 2009

** List of vehicles named Dodge Ram, trucks and vans

** Ram Pickup, produced by Ram Trucks

Ram, ram, or RAM may also ref ...

''Potemkin'' and then detonate his ship's magazines, but he was thwarted by members of his crew. Krieger ordered his ships to fall back, but the crew of ''Georgii Pobedonosets'' mutinied and joined ''Potemkin''.

The following morning, loyalist members of ''Georgii Pobedonosets'' retook control of the ship and ran her aground in Odessa harbour. The crew of ''Potemkin'', together with ''Ismail'', decided to sail for Constanța later that day where they could restock food, water and coal. The Romanians refused to provide the supplies, backed by the presence of their small protected cruiser

Protected cruisers, a type of cruiser of the late 19th century, took their name from the armored deck, which protected vital machine-spaces from fragments released by explosive shells. Protected cruisers notably lacked a belt of armour alon ...

''Elisabeta'', so the ship's committee decided to sail for the small, barely defended port of Theodosia in the Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

where they hoped to resupply. The ship arrived on the morning of 5 July, but the city's governor refused to give them anything other than food. The mutineers attempted to seize several barges of coal the following morning, but the port's garrison ambushed them and killed or captured 22 of the 30 sailors involved. They decided to return to Constanța that afternoon.

''Potemkin'' reached its destination at 23:00 on 7 July and the Romanians agreed to give asylum to the crew if they would disarm themselves and surrender the battleship. ''Ismail''s crew decided the following morning to return to Sevastopol and turn themselves in, but ''Potemkin''s crew voted to accept the terms. Captain Nicolae Negru, commander of the port, came aboard at noon and hoisted the Romanian flag and then allowed the ship to enter the inner harbor. Before the crew disembarked, Matushenko ordered that ''Potemkin''s Kingston valves be opened so she would sink to the bottom.

Later service

WhenRear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

Pisarevsky reached Constanța on the morning of 9 July, he found ''Potemkin'' half sunk in the harbour and flying the Romanian flag. After several hours of negotiations with the Romanian government, the battleship was handed over to the Russians. Later that day the Russian Navy Ensign was raised over the battleship. She was then easily refloated by the navy, but the salt water had damaged her engines and boilers. The ship left Constanța on 10 July, having to be towed back to Sevastopol, where she arrived on 14 July.McLaughlin 2003, p. 121 The ship was renamed ''Panteleimon'' (), after Saint Pantaleon, on 12 October 1905. Some members of ''Panteleimon''s crew joined a mutiny that began aboard the protected cruiser ''Ochakov'' ( ru) in November, but it was easily suppressed as both ships had been earlier disarmed.

''Panteleimon'' received an experimental underwater communications set in February 1909. Later that year, she accidentally rammed and sank the submarine ''Kambala'' ( ru) at night on 11 June ccording to Russian sources, ''Kambala'' sank in a collision with ''Rostislav'', not with ''Panteleimon'', killing the 16 crewmen aboard the submarine

While returning from a port visit to Constanța in 1911, ''Panteleimon'' ran aground on 2 October. It took several days to refloat her and make temporary repairs, and the full extent of the damage to its bottom was not fully realised for several more months. The ship participated in training and gunnery exercises for the rest of the year; a special watch was kept to ensure that no damaged seams were opened during firing. Permanent repairs, which involved replacing its boiler foundations, plating, and a large number of its hull frames, lasted from 10 January to 25 April 1912. The navy took advantage of these repairs to overhaul ''Panteleimon''s engines and boilers.

World War I

''Panteleimon'',flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the 1st Battleship Brigade, accompanied by the pre-dreadnoughts , , and ''Tri Sviatitelia'', covered the pre-dreadnought ''Rostislav'' while she bombarded Trebizond on the morning of 17 November 1914. They were intercepted the following day by the Ottoman battlecruiser ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' (the ex-German ) and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

''Midilli'' (the ex-German ) on their return voyage to Sevastopol in what came to be known as the Battle of Cape Sarych

The Battle of Cape Sarych was a naval engagement fought off the coast of Cape Sarych in the Black Sea during the First World War. In November 1914, two modern Ottoman Empire, Ottoman warships, specifically a light cruiser and a battlecruiser, eng ...

. Despite the noon hour the conditions were foggy; the capital ship

The capital ships of a navy are its most important warships; they are generally the larger ships when compared to other warships in their respective fleet. A capital ship is generally a leading or a primary ship in a naval fleet.

Strategic i ...

s initially did not spot each other. Although several other ships opened fire, hitting the ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' once, ''Panteleimon'' held her fire because her turrets could not see the Ottoman ships before they disengaged.

''Tri Sviatitelia'' and ''Rostislav'' bombarded Ottoman fortifications at the mouth of the Bosphorus

The Bosporus or Bosphorus Strait ( ; , colloquially ) is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul, Turkey. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara and forms one of the continental bo ...

on 18 March 1915, the first of several attacks intended to divert troops and attention from the ongoing Gallipoli campaign, but fired only 105 rounds before sailing north to rejoin ''Panteleimon'', ''Ioann Zlatoust'' and ''Evstafi''. ''Tri Sviatitelia'' and ''Rostislav'' were intended to repeat the bombardment the following day, but were hindered by heavy fog. On 3 April, ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' and several ships of the Ottoman navy raided the Russian port at Odessa; the Russian battleship squadron sortied to intercept them. The battleships pursued ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' the entire day, but were unable to close to effective gunnery range and were forced to break off the chase. On 25 April ''Tri Sviatitelia'' and ''Rostislav'' repeated their bombardment of the Bosphorus forts. ''Tri Sviatitelia'', ''Rostislav'' and ''Panteleimon'' bombarded the forts again on 2 and 3 May. This time a total of 337 main-gun rounds were fired in addition to 528 six-inch shells between the three battleships.Nekrasov, pp. 49, 54

On 9 May 1915, ''Tri Sviatitelia'' and ''Panteleimon'' returned to bombard the Bosphorus forts, covered by the remaining pre-dreadnoughts. ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' intercepted the three ships of the covering force, although no damage was inflicted by either side. ''Tri Sviatitelia'' and ''Panteleimon'' rejoined their consorts and the latter scored two hits on ''Yavuz Sultan Selim'' before it broke off the action. The Russian ships pursued it for six hours before giving up the chase. On 1 August, all of the Black Sea pre-dreadnoughts were transferred to the 2nd Battleship Brigade, after the more powerful dreadnought entered service. On 1 October the new dreadnought provided cover while ''Ioann Zlatoust'' and ''Pantelimon'' bombarded Zonguldak

Zonguldak () is a List of cities in Turkey, city of about 100 thousand people in the Black Sea region of Turkey. It is the seat of Zonguldak Province and Zonguldak District.Varna twice in October 1915; during the second bombardment on 27 October, she entered Varna Bay and was unsuccessfully attacked by two German submarines stationed there.

''Panteleimon'' supported Russian troops in early 1916 as they captured Trebizond and participated in an anti-shipping sweep off the north-western

The immediate effects of the mutiny are difficult to assess. It may have influenced

The immediate effects of the mutiny are difficult to assess. It may have influenced

Battleship ''Kniaz Potemkin Tavricheskiy'' on Black Sea Fleet

* [http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/jul/10d.htm A brief contemporary article by Lenin on the mutiny with the text of the sailors' manifesto]

Christian Rakovsky, The Origins of the Potemkin Mutiny (1907)

Annotated version of Zecca's ''La Révolution en Russe''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Potemkin Potemkin mutiny, * 1900 ships Russian Revolution of 1905 Battleships of the Imperial Russian Navy Captured ships Conflicts in 1905 Military history of Odesa Maritime incidents in 1905 Shipwrecks in the Black Sea Shipwrecks of Romania Scuttled vessels Naval mutinies Ships built at Shipyard named after 61 Communards Ships of the Romanian Naval Forces Battleships of Russia World War I battleships of Russia Ships built in the Russian Empire

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

n coast in January 1917 that destroyed 39 Ottoman sailing ships. On 13 April 1917, after the February Revolution

The February Revolution (), known in Soviet historiography as the February Bourgeois Democratic Revolution and sometimes as the March Revolution or February Coup was the first of Russian Revolution, two revolutions which took place in Russia ...

, the ship was renamed ''Potemkin-Tavricheskiy'' (), and then on 11 May was renamed ''Borets za svobodu'' ( – ''Freedom Fighter'').

Reserve and decommissioning

''Borets za Svobodu '' was placed in reserve in March 1918 and was captured by the Germans at Sevastopol in May. They handed the ship over to the Allies in December 1918 after the Armistice. The British wrecked her engines on 19 April 1919 when they left the Crimea to prevent the advancing Bolsheviks from using her against the White Russians. Thoroughly obsolete by this time, the battleship was captured by both sides during theRussian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, but was abandoned by the White Russians when they evacuated the Crimea in November 1920. ''Borets za Svobodu'' was scrapped beginning in 1923, although she was not stricken from the Navy List until 21 November 1925.

Legacy

The immediate effects of the mutiny are difficult to assess. It may have influenced

The immediate effects of the mutiny are difficult to assess. It may have influenced Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

Nicholas II's decisions to end the Russo-Japanese War and accept the October Manifesto, as the mutiny demonstrated that his régime no longer had the unquestioning loyalty of the military. The mutiny's failure did not stop other revolutionaries from inciting insurrections later that year, including the Sevastopol Uprising. Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, leader of the Bolshevik Party

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

, called the 1905 Revolution, including the ''Potemkin'' mutiny, a "dress rehearsal" for his successful revolution in 1917. The communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

seized upon it as a propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

symbol for their party and unduly emphasised their role in the mutiny. In fact, Matushenko explicitly rejected the Bolsheviks because he and the other leaders of the mutiny were socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

of one type or another and cared nothing for communism.Bascomb, pp. 183–184

The mutiny was memorialised most famously by Sergei Eisenstein

Sergei Mikhailovich Eisenstein; (11 February 1948) was a Soviet film director, screenwriter, film editor and film theorist. Considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, he was a pioneer in the theory and practice of montage. He is no ...

in his 1925 silent film '' Battleship Potemkin'', although the French silent film '' La Révolution en Russie'' (''Revolution in Russia'' or ''Revolution in Odessa'', 1905), directed by Lucien Nonguet was the first film to depict the mutiny, preceding Eisenstein's far more famous film by 20 years. Filmed shortly after the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922, with the derelict ''Dvenadsat Apostolov'' standing in for the broken-up ''Potemkin'', Eisenstein recast the mutiny into a predecessor of the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917 that swept the Bolsheviks to power. He emphasised their role, and implied that the mutiny failed because Matushenko and the other leaders were not better Bolsheviks. Eisenstein made other changes to dramatise the story, ignoring the major fire that swept through Odessa's dock area while ''Potemkin'' was anchored there, combining the many different incidents of rioters and soldiers fighting into a famous sequence on the steps (today known as the Potemkin Stairs), and showing a tarpaulin thrown over the sailors to be executed.

In accordance with the Marxist

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflic ...

doctrine that history is made by collective action, not individuals, Eisenstein forbore to single out any person in his film, but rather focused on the "mass protagonist". Soviet film critics hailed this approach, including the dramaturge and critic, Adrian Piotrovsky, writing for the Leningrad newspaper ''Krasnaia gazeta'': The hero is the sailors' battleship, the Odessa crowd, but characteristic figures are snatched here and there from the crowd. For a moment, like a conjuring trick, they attract all the sympathies of the audience: like the sailor Vakulinchuk, like the young woman and child on the Odessa Steps, but they emerge only to dissolve once more into the mass. This signifies: no film stars but a film of real-life types.Similarly, theatre critic Alexei Gvozdev wrote in the journal ''Artistic Life'' (''Zhizn ikusstva''): "In ''Potemkin'' there is no individual hero as there was in the old theatre. It is the mass that acts: the battleship and its sailors and the city and its population in revolutionary mood." The last survivor of the mutiny was Ivan Beshoff, who died on 25 October 1987 at the age of 102 in Dublin, Ireland.

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Battleship ''Kniaz Potemkin Tavricheskiy'' on Black Sea Fleet

* [http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/jul/10d.htm A brief contemporary article by Lenin on the mutiny with the text of the sailors' manifesto]

Christian Rakovsky, The Origins of the Potemkin Mutiny (1907)

Annotated version of Zecca's ''La Révolution en Russe''

{{DEFAULTSORT:Potemkin Potemkin mutiny, * 1900 ships Russian Revolution of 1905 Battleships of the Imperial Russian Navy Captured ships Conflicts in 1905 Military history of Odesa Maritime incidents in 1905 Shipwrecks in the Black Sea Shipwrecks of Romania Scuttled vessels Naval mutinies Ships built at Shipyard named after 61 Communards Ships of the Romanian Naval Forces Battleships of Russia World War I battleships of Russia Ships built in the Russian Empire