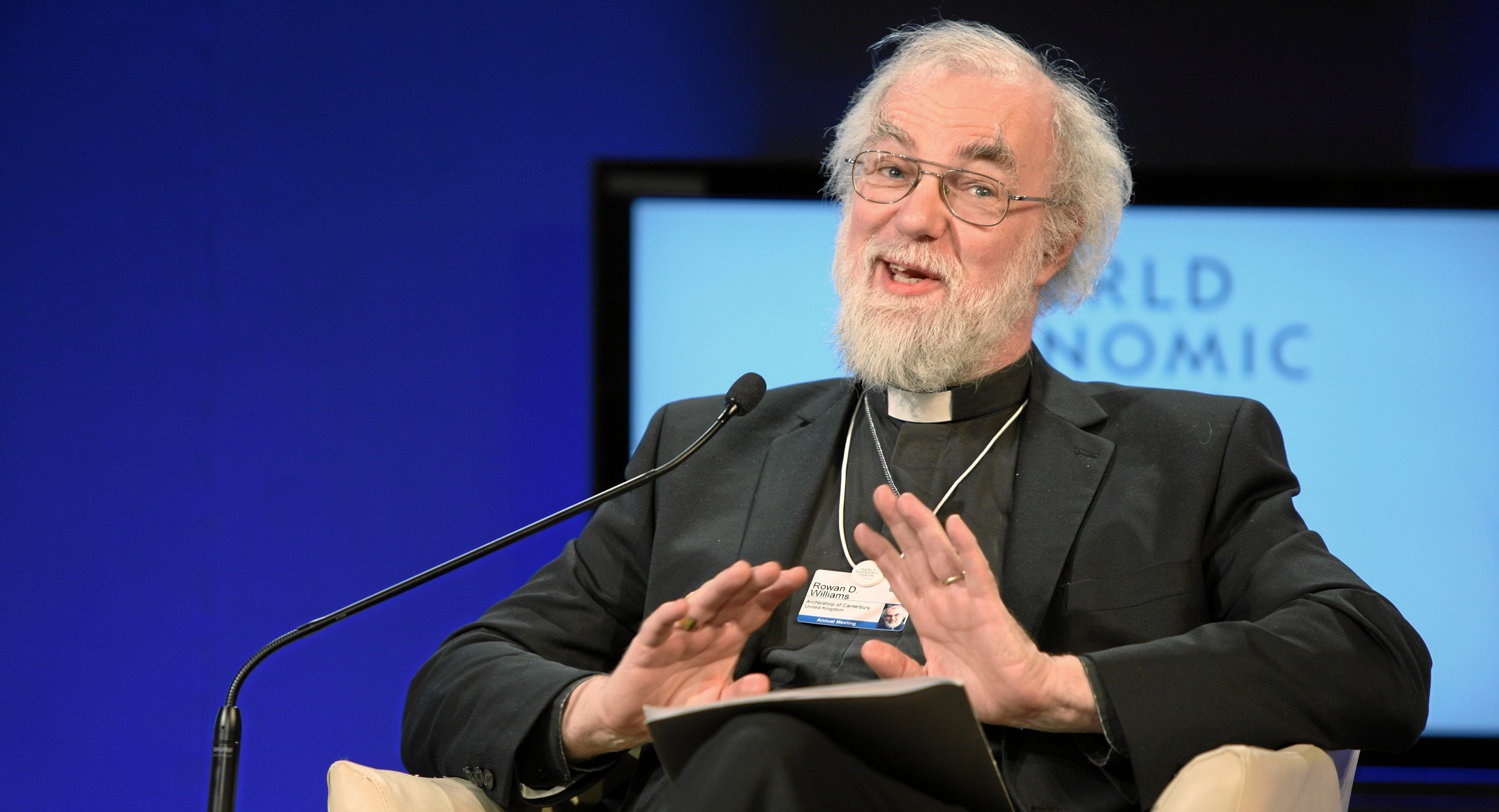

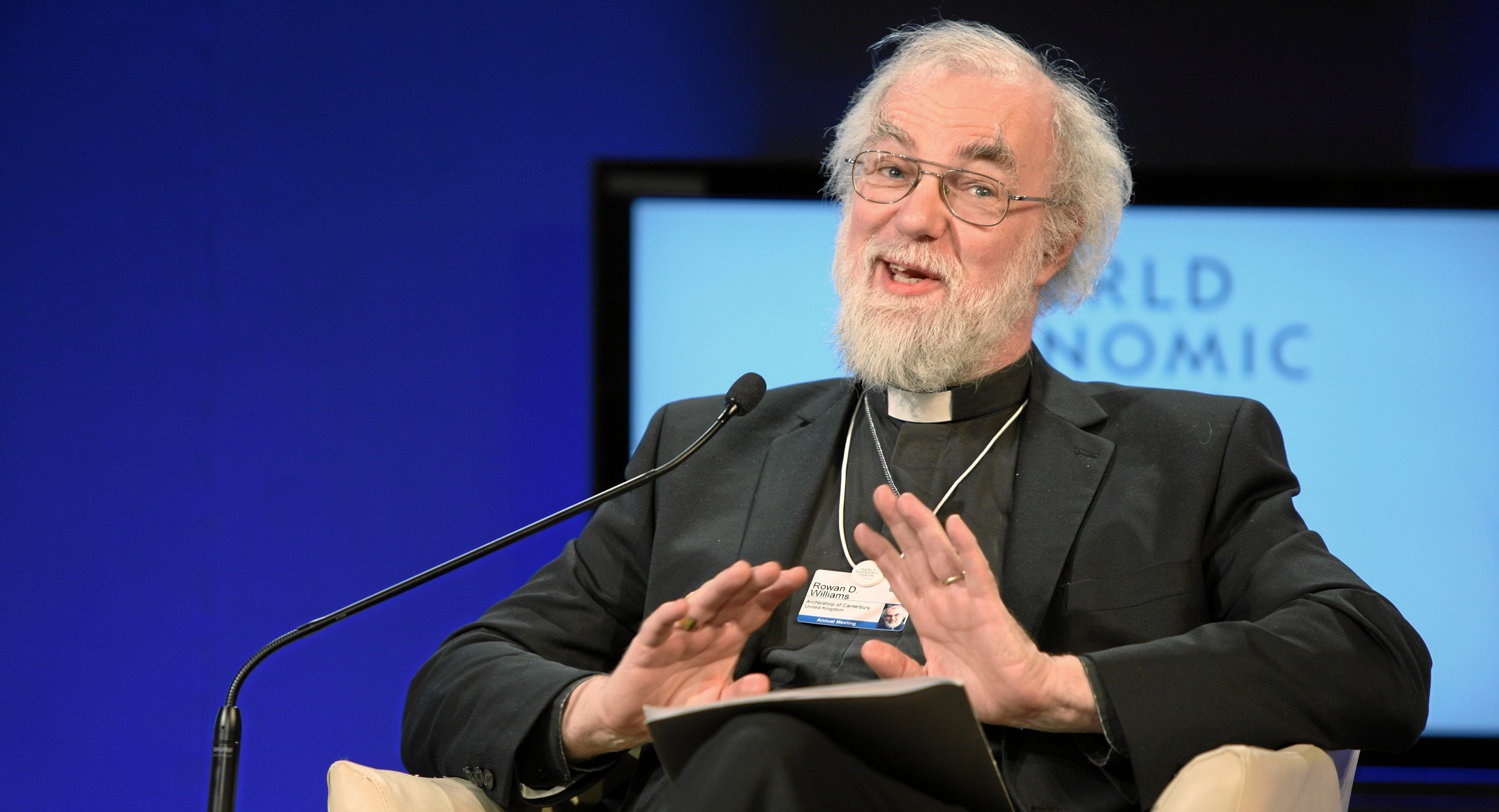

Rowan Williams on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rowan Douglas Williams, Baron Williams of Oystermouth (born 14 June 1950) is a Welsh

The

The

His interest in and involvement with social issues is longstanding. While chaplain of Clare College, Cambridge, Williams took part in

His interest in and involvement with social issues is longstanding. While chaplain of Clare College, Cambridge, Williams took part in  On 15 November 2008 Williams visited the Balaji Temple in Tividale, West Midlands, on a goodwill mission to represent the friendship between Christianity and

On 15 November 2008 Williams visited the Balaji Temple in Tividale, West Midlands, on a goodwill mission to represent the friendship between Christianity and

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury at a particularly difficult time in the relations of the churches of the Anglican Communion. His predecessor, George Carey, had sought to keep the peace between the theologically conservative primates of the communion such as Peter Akinola of Nigeria and Drexel Gomez of the West Indies and liberals such as Frank Griswold, the then primate of the US Episcopal Church.

In 2003, in an attempt to encourage dialogue, Williams appointed Robin Eames,

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury at a particularly difficult time in the relations of the churches of the Anglican Communion. His predecessor, George Carey, had sought to keep the peace between the theologically conservative primates of the communion such as Peter Akinola of Nigeria and Drexel Gomez of the West Indies and liberals such as Frank Griswold, the then primate of the US Episcopal Church.

In 2003, in an attempt to encourage dialogue, Williams appointed Robin Eames,

Williams did his doctoral work on the mid-20th-century Russian Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky. He is currently patron of the Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius, an ecumenical forum for Orthodox and Western (primarily Anglican) Christians. He has expressed his continuing sympathies with Orthodoxy in lectures and writings since that time.

Williams has written on the Spanish Catholic mystic

Williams did his doctoral work on the mid-20th-century Russian Orthodox theologian Vladimir Lossky. He is currently patron of the Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius, an ecumenical forum for Orthodox and Western (primarily Anglican) Christians. He has expressed his continuing sympathies with Orthodoxy in lectures and writings since that time.

Williams has written on the Spanish Catholic mystic

Sitara-e-Pakistan (2012)

* Membership in the

Sitara-e-Pakistan (2012)

* Membership in the

The Theology of Vladimir Nikolaievich Lossky: An Exposition and Critique

' (1975 DPhil thesis) * ''The Wound of Knowledge'' (Darton, Longman and Todd, 1979) * ''Resurrection: Interpreting the Easter Gospel'' (Darton, Longman and Todd, 1982) * ''Eucharistic Sacrifice: The Roots of a Metaphor'' (Grove Books, 1982) * ''Essays Catholic and Radical'' ed. with K. Leech (Bowerdean, 1983) * ''The Truce of God'' (London: Fount, 1983) * ''Peacemaking Theology'' (1984) * ''Open to Judgement: Sermons and Addresses'' (1984) * ''Politics and Theological Identity'' (with David Nicholls) (Jubilee, 1984) * ''Faith in the University'' (1989) * ''Christianity and the Ideal of Detachment'' (1989) * ''Teresa of Avila'' (1991) * ''Open to Judgement: Sermons and Addresses'' (Darton, Longman and Todd, 1994) * ''After Silent Centuries'' (1994) * "A Ray of Darkness" (1995) * '' Lost Icons: Essays on Cultural Bereavement'' (T & T Clark, 2000) * ''On Christian Theology'' (2000) * ''Christ on Trial'' (2000) * ''Arius: Heresy and Tradition'' (2nd ed., SCM Press, 2001) * ''The Poems of Rowan Williams'' (2002) * ''Writing in the Dust: Reflections on 11 September and Its Aftermath'' (Hodder and Stoughton, 2002) * ''Ponder These Things: Praying With Icons of the Virgin'' (Canterbury Press, 2002) * ''Faith and Experience in Early Monasticism'' (2002) * ''Silence and Honey Cakes: The Wisdom of the Desert'' (2003) ) * ''The Dwelling of the Light—Praying with Icons of Christ'' (Canterbury Press, 2003 ) * ''Darkness Yielding'', co-authored with Jim Cotter, Martyn Percy, Sylvia Sands and W. H. Vanstone (2004) * ''Anglican Identities'' (2004) * ''Why Study the Past? The Quest for the Historical Church'' (Eerdmans, 2005 ) * ''Grace and Necessity: Reflections on Art and Love'' (2005) * ''Tokens of Trust. An introduction to Christian belief.'' (Canterbury Press, 2007 ) * ''Wrestling with Angels: Conversations in Modern Theology'', ed. Mike Higton (SCM Press, 2007) *''Where God Happens: Discovering Christ in One Another'' (New Seeds, 2007) *''Dostoevsky: Language, Faith and Fiction'' (Baylor University Press, 2008); *''Choose Life'' (Bloomsbury, 2009) *''Faith in the Public Square'' (Bloomsbury, 2012) *''The Lion's World - A Journey into the Heart of Narnia'' (SPCK, 2012); *''Meeting God in Mark'' (SPCK, 2014), reprinted as ''Meeting God in Mark: Reflections for the Season of Lent'' (Westminster John Knox Press, 2015) *''Being Christian: Baptism, Bible, Eucharist, Prayer'' (Eerdmans, 2014) *''The Edge of Words'' (Bloomsbury, 2014) *''Meeting God in Paul'' (SPCK, 2015) *''On Augustine'' (Bloomsbury, 2016) *''Being Disciples: Essentials of the Christian life'' (SPCK, 2016) *''God With Us: The Meaning of the Cross and resurrection - then and now'' (SPCK, 2017) *''Holy Living: The Christian Tradition for Today'' (Bloomsbury, 2017) *''Christ the Heart of Creation'' (Bloomsbury, 2018) *''Being Human: Bodies, Minds, Persons'' (SPCK, 2018) *''Luminaries: Twenty Lives that Illuminate the Christian Way'' (SPCK, 2019) *''The Book of Taliesin'' (translation and introductions with Gwyneth Lewis; Penguin, 2019) *''The Way of St Benedict'' (Bloomsbury, 2020) *''Looking East in Winter: Contemporary Thought and the Eastern Christian Tradition'' (Bloomsbury, 2021) *''A Century of Poetry 100 poems for searching the heart'' (SPCK, 2022) *''Passions of the Soul'' (Bloomsbury, 2024) *''Discovering Christianity: A Guide for the Curious'' (SPCK, 2025)

God’s Biker: Motorcycles and Misfits

', by Sean Stillman. ( SPCK, 2018)

Archbishop of Canterbury official site

BBC profile

"The Archbishop's guide to Muslim intolerance"

– critical op-ed originally published in

"Early Christianity and Today: Some Shared Questions"

, lecture for

Documents of the Early Arian Controversy: Chronology according to Rowan Williams

"Archbishops attack profiteers and 'bank robbers' in City"

Interview of Williams by James Macintyre

* ttp://rowanwilliams.archbishopofcanterbury.org/pages/archbishop-as-patron.html www.rowanwilliams.archbishopofcanterbury.org

Interview on climate change with Nick Breeze, London 2013

Interviewed by Alan Macfarlane 1 July 2015 (video)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Williams, Rowan 1950 births Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Alumni of Wadham College, Oxford Alumni of the College of the Resurrection Anglo-Catholic bishops Archbishops of Canterbury Archbishops of Wales 20th-century Anglican archbishops 21st-century Anglican archbishops Bards of the Gorsedd Bishops of Monmouth Crossbench life peers Doctors of Divinity 20th-century English Anglican priests 21st-century English Anglican priests Fellows of the British Academy Fellows of Christ Church, Oxford Fellows of Clare College, Cambridge Fellows of the Royal Society of Literature Fellows of the Learned Society of Wales Living people Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Clergy from Swansea People educated at Dynevor School, Swansea British Anglican theologians Anglican pacifists 20th-century Welsh Anglican priests 21st-century Welsh Anglican priests Lady Margaret Professors of Divinity Ordained peers Sub-Prelates of the Venerable Order of Saint John Masters of Magdalene College, Cambridge Staff of Westcott House, Cambridge Welsh-speaking academics Welsh-speaking clergy Anglo-Catholic socialists Welsh Anglo-Catholics Welsh Christian socialists Christian socialist theologians Anglo-Catholic theologians Anglican poets Recipients of the President's Medal (British Academy) Fellows of Merton College, Oxford New Statesman people Life peers created by Elizabeth II 21st-century Anglican theologians 20th-century Anglican theologians Welsh male poets 21st-century Welsh poets Peers retired under the House of Lords Reform Act 2014 Academics of the College of the Resurrection

Anglican

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

bishop, theologian and poet, who served as the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

from 2002 to 2012. Previously the Bishop of Monmouth and Archbishop of Wales

The post of Archbishop of Wales () was created in 1920 when the Church in Wales was separated from the Church of England and disestablished. The four historic Welsh dioceses had previously formed part of the Province of Canterbury, and so came ...

, Williams was the first Archbishop of Canterbury in modern times not to be appointed from within the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

.

Williams's primacy was marked by speculation that the Anglican Communion

The Anglican Communion is a Christian Full communion, communion consisting of the Church of England and other autocephalous national and regional churches in full communion. The archbishop of Canterbury in England acts as a focus of unity, ...

(in which the Archbishop of Canterbury is the leading figure) was on the verge of fragmentation over disagreements on contemporary issues such as homosexuality

Homosexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior between people of the same sex or gender. As a sexual orientation, homosexuality is "an enduring pattern of emotional, romantic, and/or sexu ...

and the ordination of women

The ordination of women to Minister of religion, ministerial or priestly office is an increasingly common practice among some contemporary major religious groups. It remains a controversial issue in certain religious groups in which ordination ...

. Williams worked to keep all sides in dialogue. Notable events during his time as Archbishop of Canterbury include the rejection by a majority of dioceses of his proposed Anglican Covenant and, in the final general synod of his tenure, his unsuccessful attempt to secure a sufficient majority for a measure to allow the appointment of women as bishops in the Church of England.

Having spent much of his earlier career as an academic at the universities of Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

and Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

successively, Williams speaks three languages and reads at least nine. After standing down as archbishop, Williams took up the position of chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

of the University of South Wales

The University of South Wales (USW) () is a public university in Wales, with campuses in Cardiff, Newport and Pontypridd. It was formed on 11 April 2013 from the merger of the University of Glamorgan and the University of Wales, Newport. The ...

in 2014 and served as master of Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

between 2013 and 2020. He also delivered the Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh (, ; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a Public university, public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Founded by the City of Edinburgh Council, town council under th ...

in 2013.

Williams retired as Archbishop of Canterbury on 31 December 2012, succeeded by Justin Welby

Justin Portal Welby (born 6 January 1956) is an Anglican bishop who served as the 105th archbishop of Canterbury in the Church of England from 2013 to 2025.

After an 11-year career in the oil industry, Welby trained for ordination at St John ...

. On 26 December 2012, 10 Downing Street

10 Downing Street in London is the official residence and office of the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, prime minister of the United Kingdom. Colloquially known as Number 10, the building is located in Downing Street, off Whitehall in th ...

announced Williams's elevation to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

as a life peer

In the United Kingdom, life peers are appointed members of the peerage whose titles cannot be inherited, in contrast to hereditary peers. Life peers are appointed by the monarch on the advice of the prime minister. With the exception of the D ...

, so that he could continue to speak in the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

. Following the creation of his title on 8 January and its gazetting on 11 January 2013, he was introduced to the temporal benches of the House of Lords as Baron Williams of Oystermouth on 15 January 2013, sitting as a crossbencher

A crossbencher is a minor party or independent member of some legislatures, such as the Parliament of Australia. In the British House of Lords the term refers to members of the parliamentary group of non-political peers. They take their name fr ...

. Oystermouth is a district of Swansea. He retired from the House on 31 August 2020 and from Magdalene College

Magdalene College ( ) is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary ...

that Autumn, returning to Abergavenny

Abergavenny (; , , archaically , ) is a market town and Community (Wales), community in Monmouthshire, Wales. Abergavenny is promoted as a "Gateway to Wales"; it is approximately from the England–Wales border, border with England and is loca ...

, in his former diocese (Monmouthshire

Monmouthshire ( ; ) is a Principal areas of Wales, county in the South East Wales, south east of Wales. It borders Powys to the north; the English counties of Herefordshire and Gloucestershire to the north and east; the Severn Estuary to the s ...

).

Early life and ordination

Williams was born on 14 June 1950 inSwansea

Swansea ( ; ) is a coastal City status in the United Kingdom, city and the List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, second-largest city of Wales. It forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area, officially known as the City and County of ...

, Wales, into a Welsh-speaking family. He was the only child of Aneurin Williams and his wife Nancy Delphine (known as "Del") Williams (née Morris) – Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

s who became Anglicans in 1961. He was educated at the state sector Dynevor School, Swansea, before reading theology at Christ's College, Cambridge

Christ's College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. The college includes the Master, the Fellows of the College, and about 450 undergraduate and 250 graduate students. The c ...

, whence he graduated with starred first-class honours. He then went to Wadham College, Oxford

Wadham College ( ) is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It is located in the centre of Oxford, at the intersection of Broad Street, Oxford, Broad Street and Parks Road ...

, where he studied under A. M. Allchin and graduated with a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1975 with a thesis entitled ''The Theology of Vladimir Nikolaievich Lossky: An Exposition and Critique''.

Williams lectured and trained for ordination at the College of the Resurrection

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary education, tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding academic degree, degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further educatio ...

in Mirfield

Mirfield () is a town and civil parishes in England, civil parish in the Metropolitan Borough of Kirklees, West Yorkshire, England. Historic counties of England, Historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire, it is on the A644 road (Great B ...

, West Yorkshire, for two years (1975–1977). In 1977, he returned to Cambridge to teach theology as a tutor (as well as chaplain and Director of Studies) at Westcott House; he was made a deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions.

Major Christian denominations, such as the Cathol ...

in the chapel by Eric Wall, Bishop of Huntingdon

The Bishop of Huntingdon is an episcopal title used by a suffragan bishop of the Church of England Diocese of Ely, in the Province of Canterbury, England. The title takes its name after Huntingdon, the historic county town of Huntingdonshire, E ...

, at Michaelmas

Michaelmas ( ; also known as the Feast of Saints Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the Feast of the Archangels, or the Feast of Saint Michael and All Angels) is a Christian festival observed in many Western Christian liturgical calendars on 29 Se ...

(2 October). While there, he was ordained a priest the Petertide following (2 July 1978), by Peter Walker, Bishop of Ely

The Bishop of Ely is the Ordinary (officer), ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Ely in the Province of Canterbury. The diocese roughly covers the county of Cambridgeshire (with the exception of the Soke of Peterborough), together with ...

, at Ely Cathedral

Ely Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of the Holy and Undivided Trinity of Ely, is an Church of England, Anglican cathedral in the city of Ely, Cambridgeshire, England.

The cathedral can trace its origin to the abbey founded in Ely in 67 ...

.

Private life

On 4 July 1981, Williams married Jane Paul, a writer and lecturer in theology. They have two children.Career

Early academic career and pastoral ministry

Williams did not have a formalcuracy

A curate () is a person who is invested with the ''care'' or ''cure'' () of souls of a parish. In this sense, ''curate'' means a parish priest; but in English-speaking countries the term ''curate'' is commonly used to describe clergy who are ass ...

until 1980, when he served at St George's, Chesterton, Cambridge

Chesterton is a suburb in Cambridge, England. As of the 2021 United Kingdom census, 2021 UK census, the suburb had a population of 18,620 people.

History

Archaeological evidence indicates that the area that is now Chesterton has been inhabited ...

, until 1983, after having been appointed a university lecturer in divinity

Divinity (from Latin ) refers to the quality, presence, or nature of that which is divine—a term that, before the rise of monotheism, evoked a broad and dynamic field of sacred power. In the ancient world, divinity was not limited to a single ...

at Cambridge. In 1984 he became dean and chaplain of Clare College and, in 1986 at the age of 36, he was appointed to the Lady Margaret Professor of Divinity at Oxford, a position which brought with it appointment to a residentiary canonry

Canon () is a Christian title usually used to refer to a member of certain bodies in subject to an canon law, ecclesiastical rule.

Originally, a canon was a cleric living with others in a clergy house or, later, in one of the houses within the p ...

of Christ Church Cathedral. In 1989 he received the degree of Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (DD or DDiv; ) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity (academic discipline), divinity (i.e., Christian theology and Christian ministry, ministry or other theologies. The term is more common in the Englis ...

(DD) and, in 1990, was elected a Fellow of the British Academy

The British Academy for the Promotion of Historical, Philosophical and Philological Studies is the United Kingdom's national academy for the humanities and the social sciences.

It was established in 1902 and received its royal charter in the sa ...

(FBA).

Episcopal ministry

On 5 December 1991, Williams was elected Bishop of Monmouth in theChurch in Wales

The Church in Wales () is an Anglican church in Wales, composed of six dioceses.

The Archbishop of Wales does not have a fixed archiepiscopal see, but serves concurrently as one of the six diocesan bishops. The position is currently held b ...

: he was consecrated a bishop on 1 May 1992 at St Asaph Cathedral and enthroned at Newport Cathedral on 14 May. He continued to serve as Bishop of Monmouth after he was elected to also be the Archbishop of Wales

The post of Archbishop of Wales () was created in 1920 when the Church in Wales was separated from the Church of England and disestablished. The four historic Welsh dioceses had previously formed part of the Province of Canterbury, and so came ...

in December 1999, in which capacity he was enthroned again at Newport Cathedral on 26 February 2000.

In 2002, he was announced as the successor to George Carey as Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

— the senior bishop in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. The Archbishop of Canterbury in England acts as a focus of unity recognised as ''primus inter pares

is a Latin phrase meaning first among equals. It is typically used as an honorary title for someone who is formally equal to other members of their group but is accorded unofficial respect, traditionally owing to their seniority in office.

H ...

'' ("first among equals") but does not exercise authority in Anglican provinces outside the Church of England. As a bishop of the disestablished Church in Wales, Williams was the first Archbishop of Canterbury since the English Reformation

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops Oath_of_Supremacy, over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church ...

to be appointed to this office from outside the Church of England. His election by the Chapter of Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

was confirmed by nine bishops in the customary ceremony in London on 2 December 2002, when he officially became Archbishop of Canterbury. He was enthroned at Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

on 27 February 2003 as the 104th Archbishop of Canterbury.

The

The translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

of Williams to Canterbury was widely canvassed. As a bishop he had demonstrated a wide range of interests in social and political matters and was widely regarded, by academics and others, as a figure who could make Christianity credible to the intelligent unbeliever. As a patron of Affirming Catholicism, his appointment was a considerable departure from that of his predecessor and his views, such as those expressed in a widely published lecture on homosexuality were seized on by a number of evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

and conservative Anglicans. The debate had begun to divide the Anglican Communion, however, and Williams, in his new role as its leader was to have an important role.

As Archbishop of Canterbury, Williams acted ''ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, or council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by r ...

'' as visitor

A visitor, in English and Welsh law and history, is an overseer of an autonomous ecclesiastical or eleemosynary institution, often a charitable institution set up for the perpetual distribution of the founder's alms and bounty, who can interve ...

of King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

, the University of Kent

The University of Kent (formerly the University of Kent at Canterbury, abbreviated as UKC) is a Collegiate university, collegiate public university, public research university based in Kent, United Kingdom. The university was granted its roya ...

and Keble College, Oxford

Keble College () is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England. Its main buildings are on Parks Road, opposite the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, University Museum a ...

, governor of Charterhouse School

Charterhouse is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school (English independent boarding school for pupils aged 13–18) in Godalming, Surrey, England. Founded by Thomas Sutton in 1611 on the site of the old Carthusian monastery in Charter ...

, and, since 2005, as (inaugural) chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

of Canterbury Christ Church University

Canterbury Christ Church University (CCCU) is a Public university, public research university located in Canterbury, Kent, England. Founded as a Church of England college for teacher training in 1962, it was granted university status in 2005.

...

. In addition to these ''ex officio'' roles, Cambridge University awarded him an honorary doctorate in divinity in 2006; in April 2007, Trinity College and Wycliffe College, both associated with the University of Toronto

The University of Toronto (UToronto or U of T) is a public university, public research university whose main campus is located on the grounds that surround Queen's Park (Toronto), Queen's Park in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It was founded by ...

, awarded him a joint Doctor of Divinity degree during his first visit to Canada since being enthroned and he also received honorary degrees and fellowships from various universities including Kent

Kent is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England. It is bordered by Essex across the Thames Estuary to the north, the Strait of Dover to the south-east, East Sussex to the south-west, Surrey to the west, and Gr ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and non-metropolitan district in Oxfordshire, England, of which it is the county town.

The city is home to the University of Oxford, the List of oldest universities in continuou ...

, and Roehampton

Roehampton is an area in southwest London, sharing its SW15 postcode with neighbouring Putney and Kingston Vale, and takes up a far western strip, running north to south, in the London Borough of Wandsworth. It contains a number of large counc ...

.

Williams speaks or reads eleven languages: English, Welsh, Spanish, French, German, Russian, Biblical Hebrew

Biblical Hebrew ( or ), also called Classical Hebrew, is an archaic form of the Hebrew language, a language in the Canaanite languages, Canaanitic branch of the Semitic languages spoken by the Israelites in the area known as the Land of Isra ...

, Syriac, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, and both Ancient (koine) and Modern Greek

Modern Greek (, or , ), generally referred to by speakers simply as Greek (, ), refers collectively to the dialects of the Greek language spoken in the modern era, including the official standardized form of the language sometimes referred to ...

. He learnt Russian in order to be able to read the works of Dostoevsky in the original. He has since described his spoken German as a "disaster area" and said that he is "a very clumsy reader and writer of Russian". He also stated that he knows some Italian, that would mean he knows twelve languages.

Williams is also a poet and translator of poetry. His collection ''The Poems of Rowan Williams'', published by Perpetua Press, was longlisted for the Wales Book of the Year award in 2004. Besides his own poems, which have a strong spiritual and landscape flavour, the collection contains several fluent translations from Welsh poets. He was criticised in the press for allegedly supporting a "pagan

Paganism (, later 'civilian') is a term first used in the fourth century by early Christians for people in the Roman Empire who practiced polytheism, or ethnic religions other than Christianity, Judaism, and Samaritanism. In the time of the ...

organisation", the Welsh Gorsedd of Bards, which promotes Welsh language and literature and uses druidic ceremonial but is actually not religious in nature.

In 2005, Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

married Camilla Parker Bowles, a divorcee, in a civil ceremony. Afterwards, Williams gave the couple a formal service of blessing. In fact, the arrangements for the wedding and service were strongly supported by the Archbishop "consistent with the Church of England guidelines concerning remarriage". The "strongly-worded" act of penitence by the couple, a confessional prayer written by Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

, Archbishop of Canterbury, to King Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement w ...

, was interpreted as a confession by the bride and groom of past sins, albeit without specific reference and going "some way towards acknowledging concerns" over their past misdemeanours.

Williams officiated at the wedding of Prince William and Catherine Middleton on 29 April 2011.

On 16 November 2011, Williams attended a special service at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an Anglican church in the City of Westminster, London, England. Since 1066, it has been the location of the coronations of 40 English and British m ...

celebrating the 400th anniversary of the King James Bible

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB) and the Authorized Version (AV), is an Early Modern English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by ...

in the presence of Queen Elizabeth, Prince Philip

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh (born Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark, later Philip Mountbatten; 10 June 19219 April 2021), was the husband of Queen Elizabeth II. As such, he was the consort of the British monarch from h ...

and Prince Charles

Charles III (Charles Philip Arthur George; born 14 November 1948) is King of the United Kingdom and the 14 other Commonwealth realms.

Charles was born at Buckingham Palace during the reign of his maternal grandfather, King George VI, and ...

, Patron of the King James Bible Trust.

To mark the ending of his tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury, Williams presented a BBC television documentary about Canterbury Cathedral

Canterbury Cathedral is the cathedral of the archbishop of Canterbury, the spiritual leader of the Church of England and symbolic leader of the worldwide Anglican Communion. Located in Canterbury, Kent, it is one of the oldest Christianity, Ch ...

, in which he reflected upon his time in office. Entitled ''Goodbye to Canterbury'', the programme was screened on 1 January 2013.

2010 General Synod address

On 9 February 2010, in an address to the General Synod of the Church of England, Williams warned that damaging infighting over the ordination of women as bishops and gay priests could lead to a permanent split in the Anglican Communion. He stressed that he did not "want nor relish" the prospect of division and called on the Church of England and Anglicans worldwide to step back from a "betrayal" of God's mission and to put the work of Christ beforeschism

A schism ( , , or, less commonly, ) is a division between people, usually belonging to an organization, movement, or religious denomination. The word is most frequently applied to a split in what had previously been a single religious body, suc ...

. But he conceded that, unless Anglicans could find a way to live with their differences over women as bishops and homosexual ordination, the church would change shape and become a multi-tier communion of different levels – a schism in all but name.

Williams also said that "it may be that the covenant creates a situation in which there are different levels of relationship between those claiming the name of Anglican. I don’t at all want or relish this, but suspect that, without a major change of heart all round, it may be an unavoidable aspect of limiting the damage we are already doing to ourselves." In such a structure, some churches would be given full membership of the Anglican Communion, while others had a lower-level form of membership, with no more than observer status on some issues. Williams also used his keynote address to issue a profound apology for the way that he had spoken about "exemplary and sacrificial" gay Anglican priests in the past. "There are ways of speaking about the question that seem to ignore these human realities or to undervalue them," he said. "I have been criticised for doing just this, and I am profoundly sorry for the carelessness that could give such an impression."

Subsequent academic career

On 17 January 2013, Williams was admitted as the 35th Master of Magdalene College, Cambridge and served until September 2020. He was also made an honoraryProfessor

Professor (commonly abbreviated as Prof.) is an Academy, academic rank at university, universities and other tertiary education, post-secondary education and research institutions in most countries. Literally, ''professor'' derives from Latin ...

of Contemporary Christian Thought by the University of Cambridge in 2017. On 18 June 2013, the University of South Wales

The University of South Wales (USW) () is a public university in Wales, with campuses in Cardiff, Newport and Pontypridd. It was formed on 11 April 2013 from the merger of the University of Glamorgan and the University of Wales, Newport. The ...

announced his appointment as its new chancellor

Chancellor () is a title of various official positions in the governments of many countries. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the (lattice work screens) of a basilica (court hall), which separa ...

, the ceremonial head of the university.

In 2015, it was reported that Williams had written a play called ''Shakeshafte'', about a meeting between William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

and Edmund Campion, a Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

priest and martyr. Williams suspects that Shakespeare was Catholic, though not a regular churchgoer. The play took to the stage in July 2016 and was received favourably.

Patronage

Williams is patron of the Canterbury Open Centre run by Catching Lives, a local charity supporting the destitute. He has also been patron of the Peace Mala Youth Project For World Peace since 2002, one of his last engagements as Archbishop of Wales being to lead the charity's launch ceremony. In addition, he is president of WaveLength Charity, a UK-wide organisation which gives TVs and radios to isolated and vulnerable people; every Archbishop of Canterbury since the charity's inception in 1939 has actively participated in this role. Williams is also patron of the T. S. Eliot Society and delivered the society's annual lecture in November 2013. Williams was also patron of the Birmingham-based charity The Feast, from 2010 until his retirement as Archbishop of Canterbury. Williams has been a patron of the Cogwheel Trust, a local Cambridgeshire charity providing affordable counselling, since 2015 and is active in his support. On 1 May 2013 he became chair of the board of trustees ofChristian Aid

Christian Aid is a relief and development charity of 41 Christian (Protestant and Orthodox) churches in Great Britain and Ireland, and works to support sustainable development, eradicate poverty, support civil society and provide disaster rel ...

. He is the Chair of Trustees of the Council for the Defence of the British Universities (CDBU).

Together with Grey Ruthven, 2nd Earl of Gowrie, and Sir Daniel Day-Lewis

Sir Daniel Michael Blake Day-Lewis (born 29 April 1957) is an English actor. Often described as one of the greatest actors in the history of cinema, he is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received by Daniel Day-Lewis, numerous a ...

, Williams is a patron of the Wilfred Owen Association, formed in 1989 to commemorate the life and work of the World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

poet Wilfred Owen

Wilfred Edward Salter Owen Military Cross, MC (18 March 1893 – 4 November 1918) was an English poet and soldier. He was one of the leading poets of the First World War. His war poetry on the horrors of Trench warfare, trenches and Chemi ...

.

He is the visitor of the Oratory of the Good Shepherd

The Oratory of the Good Shepherd (OGS) is a dispersed international religious community, within the Anglican Communion. Members of the oratory are bound together by a common rule and discipline, which requires consecrated celibacy, and are strength ...

, a dispersed Anglican religious community of male priests and lay brothers. He also acts as a visitor to the new monastic Holywell Community in Abergavenny

Abergavenny (; , , archaically , ) is a market town and Community (Wales), community in Monmouthshire, Wales. Abergavenny is promoted as a "Gateway to Wales"; it is approximately from the England–Wales border, border with England and is loca ...

.

He is also a patron of the Fellowship of Saint Alban and Saint Sergius which promotes ecumenical relationships between the Anglican and Orthodox churches.

Theology

Williams, a scholar of theChurch Fathers

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical peri ...

and a historian of Christian spirituality, wrote in 1983 that orthodoxy should be seen "as a tool rather than an end in itself..." It is not something which stands still. Thus "old styles come under increasing strain, new speech needs to be generated". He sees orthodoxy as a number of "dialogues": a constant dialogue with Christ, crucified and risen; but also that of the community of faith with the world – "a risky enterprise", as he writes. "We ought to be puzzled", he says, "when the world is not challenged by the gospel." It may mean that Christians have not understood the kinds of bondage to which the gospel is addressed. He has also written that "orthodoxy is inseparable from sacramental practice... The eucharist is the paradigm of that dialogue which is 'orthodoxy'". This stance may help to explain both his social radicalism and his view of the importance of the Church, and thus of the holding together of the Anglican communion over matters such as homosexuality: his belief in the idea of the Church is profound.

John Shelby Spong

John Shelby "Jack" Spong (June 16, 1931 – September 12, 2021) was an American bishop of the Episcopal Church. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, he served as the Bishop of Newark, New Jersey, from 1979 to 2000. Spong was a liberal Christian ...

once accused Williams of being a "neo-medievalist", preaching orthodoxy to the people in the pew but knowing in private that it is not true. In an interview with the magazine ''Third Way

The Third Way is a predominantly centrist political position that attempts to reconcile centre-right and centre-left politics by advocating a varying synthesis of Right-wing economics, right-wing economic and Left-wing politics, left-wing so ...

'', Williams responded:

Although generally considered an Anglo-Catholic

Anglo-Catholicism comprises beliefs and practices that emphasise the Catholicism, Catholic heritage (especially pre-English Reformation, Reformation roots) and identity of the Church of England and various churches within Anglicanism. Anglo-Ca ...

, Williams has broad sympathies. One of his first publications, in the largely evangelical Grove Books series, has the title ''Eucharistic Sacrifice: The Roots of a Metaphor''.

Moral theology

Williams's contributions to Anglican views of homosexuality were perceived as quite liberal before he became the Archbishop of Canterbury. These views are evident in a paper written by Williams called "The Body's Grace", which he originally delivered as the 10th Michael Harding Memorial Address in 1989 to the Lesbian and Gay Christian Movement, and which is now part of a series of essays collected in the book ''Theology and Sexuality'' (ed. Eugene Rogers, Blackwells 2002). At the Lambeth Conference in July 1998, then Bishop Rowan Williams of Monmouth abstained and did not vote in favour of the conservative resolution on human sexuality. These actions, combined with his initial support for openly gay Canon Jeffrey John, gained him support among liberals and caused frustration for conservatives.Social views

His interest in and involvement with social issues is longstanding. While chaplain of Clare College, Cambridge, Williams took part in

His interest in and involvement with social issues is longstanding. While chaplain of Clare College, Cambridge, Williams took part in anti-nuclear

The Anti-nuclear war movement is a social movement that opposes various nuclear technologies. Some direct action groups, environmental movements, and professional organisations have identified themselves with the movement at the local, n ...

demonstrations at United States bases. In 1985, he was arrested for singing psalms

The Book of Psalms ( , ; ; ; ; , in Islam also called Zabur, ), also known as the Psalter, is the first book of the third section of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) called ('Writings'), and a book of the Old Testament.

The book is an anthology of B ...

as part of a protest organised by the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at Lakenheath

Lakenheath is a village and civil parish in the West Suffolk (district), West Suffolk district of Suffolk in eastern England. It has a population of 4,691 according to the 2011 Census, and is situated close to the county boundaries of both Nor ...

, an American air base in Suffolk; his fine

Fine may refer to:

Characters

* Fran Fine, the title character of ''The Nanny''

* Sylvia Fine (''The Nanny''), Fran's mother on ''The Nanny''

* Officer Fine, a character in ''Tales from the Crypt'', played by Vincent Spano

Legal terms

* Fine (p ...

was paid by his college. At this time he was a member of the left-wing Anglo-Catholic Jubilee Group headed by Kenneth Leech and he collaborated with Leech in a number of publications including the anthology of essays to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the Oxford Movement

The Oxford Movement was a theological movement of high-church members of the Church of England which began in the 1830s and eventually developed into Anglo-Catholicism. The movement, whose original devotees were mostly associated with the Un ...

entitled ''Essays Catholic and Radical'' in 1983.

He was in New York at the time of September 2001 attacks, only yards from Ground Zero

A hypocenter or hypocentre (), also called ground zero or surface zero, is the point on the Earth's surface directly below a nuclear explosion, meteor air burst, or other mid-air explosion. In seismology, the hypocenter of an earthquake is its p ...

delivering a lecture; he subsequently wrote a short book, ''Writing in the Dust'', offering reflections on the event. In reference to Al Qaeda

, image = Flag of Jihad.svg

, caption = Jihadist flag, Flag used by various al-Qaeda factions

, founder = Osama bin Laden{{Assassinated, Killing of Osama bin Laden

, leaders = {{Plainlist,

* Osama bin Lad ...

, he said that terrorists "can have serious moral goals" and that "Bombast about evil individuals doesn't help in understanding anything." He subsequently worked with Muslim leaders in England and on the third anniversary of 9/11 spoke, by invitation, at the Al-Azhar University

The Al-Azhar University ( ; , , ) is a public university in Cairo, Egypt. Associated with Al-Azhar Al-Sharif in Islamic Cairo, it is Egypt's oldest degree-granting university and is known as one of the most prestigious universities for Islamic ...

Institute in Cairo on the subject of the Trinity. He stated that the followers of the will of God should not be led into ways of violence. He contributed to the debate prior to the 2005 general election criticising assertions that immigration was a cause of crime. Williams has argued that the provisional adoption of Islamic

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

law as a valid means of arbitration (in matters such as marriage) among Muslim communities in the United Kingdom is "unavoidable", and should not be resisted.

On 15 November 2008 Williams visited the Balaji Temple in Tividale, West Midlands, on a goodwill mission to represent the friendship between Christianity and

On 15 November 2008 Williams visited the Balaji Temple in Tividale, West Midlands, on a goodwill mission to represent the friendship between Christianity and Hinduism

Hinduism () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for a range of Indian religions, Indian List of religions and spiritual traditions#Indian religions, religious and spiritual traditions (Sampradaya, ''sampradaya''s) that are unified ...

. On 6 May 2010 Williams met Indian Islamic leader, Mohammed Burhanuddin, at ''Huseini Mosque'' in Northolt

Northolt is a town in North West London, England, spread across both sides of the A40 trunk road. It is west-northwest of Charing Cross and is one of the seven major towns that make up the London Borough of Ealing and a smaller part in th ...

, London, to discuss the need for interfaith co-operation; and planted a "tree of faith" in the mosque's grounds to signify the many commonalities between the two religions.

Economics

In 2002, Williams delivered theRichard Dimbleby

Frederick Richard Dimbleby (25 May 1913 – 22 December 1965) was an English journalist and broadcaster who became the BBC's first war correspondent and then its leading TV news commentator.

As host of the long-running current affairs pro ...

lecture and chose to talk about the problematic nature of the nation-state but also of its successors. He cited the "market state" as offering an inadequate vision of the way a state should operate, partly because it was liable to short-term and narrowed concerns (thus rendering it incapable of dealing with, for instance, issues relating to the degradation of the natural environment) and partly because a public arena which had become value-free was liable to disappear amidst the multitude of competing private interests. (He noted the same moral vacuum in British society after his visit to China in 2006.) He is not uncritical of communitarianism

Communitarianism is a philosophy that emphasizes the connection between the individual and the community. Its overriding philosophy is based on the belief that a person's social identity and personality are largely molded by community relation ...

, but his reservations about consumerism

Consumerism is a socio-cultural and economic phenomenon that is typical of industrialized societies. It is characterized by the continuous acquisition of goods and services in ever-increasing quantities. In contemporary consumer society, the ...

have been a constant theme. These views have often been expressed in quite strong terms; for example, he once commented that "Every transaction in the developed economies of the West can be interpreted as an act of aggression against the economic losers in the worldwide game."

Williams has supported the Robin Hood tax campaign since March 2010, re-affirming his support in a November 2011 article he published in the ''Financial Times''. He is also a vocal opponent of tax avoidance and a proponent of corporate social responsibility, arguing that "economic growth and prosperity are about serving the human good, not about serving private ends".

Iraq War and possible attack on Syria or Iran

Williams was to repeat his opposition to American action in October 2002 when he signed a petition against theIraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

as being against United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN) ethics and Christian teaching, and "lowering the threshold of war unacceptably". Again on 30 June 2004, together with then-Archbishop of York

The archbishop of York is a senior bishop in the Church of England, second only to the archbishop of Canterbury. The archbishop is the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of York and the metropolitan bishop of the province of York, which covers the ...

, David Hope, and on behalf of all 114 Church of England bishops, he wrote to Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party (UK), Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He was Leader ...

expressing deep concern about UK government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

policy and criticising the coalition

A coalition is formed when two or more people or groups temporarily work together to achieve a common goal. The term is most frequently used to denote a formation of power in political, military, or economic spaces.

Formation

According to ''A G ...

troops' conduct in Iraq

Iraq, officially the Republic of Iraq, is a country in West Asia. It is bordered by Saudi Arabia to Iraq–Saudi Arabia border, the south, Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq border, the east, the Persian Gulf and ...

. The letter cited the abuse of Iraqi detainees, which was described as having been "deeply damaging" — and stated that the government's apparent double standards "diminish the credibility of western governments". In December 2006 he expressed doubts in an interview on the Today programme on BBC Radio 4 about whether he had done enough to oppose the war.

On 5 October 2007, Williams visited Iraqi refugees in Syria. In a BBC interview after his trip he described advocates of a United States attack on Syria or Iran as "criminal, ignorant and potentially murderous". He said, "When people talk about further destabilization of the region and you read some American political advisers speaking of action against Syria and Iran, I can only say that I regard that as criminal, ignorant and potentially murderous folly." A few days earlier, the former US ambassador to the UN John R. Bolton had called for the bombing of Iran at a fringe meeting of the Conservative Party conference. In Williams's Humanitas Programme lecture at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

in January 2014, he "characterized the impulse to intervene as a need to be seen to do something rather than nothing" and advocated for "a religiously motivated nonviolence which refuses to idolise human intervention in all circumstances."

Unity of the Anglican Communion

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury at a particularly difficult time in the relations of the churches of the Anglican Communion. His predecessor, George Carey, had sought to keep the peace between the theologically conservative primates of the communion such as Peter Akinola of Nigeria and Drexel Gomez of the West Indies and liberals such as Frank Griswold, the then primate of the US Episcopal Church.

In 2003, in an attempt to encourage dialogue, Williams appointed Robin Eames,

Williams became Archbishop of Canterbury at a particularly difficult time in the relations of the churches of the Anglican Communion. His predecessor, George Carey, had sought to keep the peace between the theologically conservative primates of the communion such as Peter Akinola of Nigeria and Drexel Gomez of the West Indies and liberals such as Frank Griswold, the then primate of the US Episcopal Church.

In 2003, in an attempt to encourage dialogue, Williams appointed Robin Eames, Archbishop of Armagh

The Archbishop of Armagh is an Episcopal polity, archiepiscopal title which takes its name from the Episcopal see, see city of Armagh in Northern Ireland. Since the Reformation in Ireland, Reformation, there have been parallel apostolic success ...

and Primate of All Ireland, as chairman of the Lambeth Commission on Communion, to examine the challenges to the unity of the Anglican Communion, stemming from the consecration of Gene Robinson

Vicky Gene Robinson (born May 29, 1947) is a retired bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of New Hampshire. Robinson was elected Coadjutor bishop, bishop coadjutor in 2003 and succeeded as bishop diocesan in March 2004. Before becoming bishop, he se ...

as Bishop of New Hampshire, and the blessing of same-sex unions in the Diocese of New Westminster. (Robinson was in a same-sex relationship.) The Windsor Report, as it was called, was published in October 2004. It recommended solidifying the connection between the churches of the communion by having each church ratify an "Anglican Covenant" that would commit them to consulting the wider communion when making major decisions. It also urged those who had contributed to disunity to express their regret.

In November 2005, following a meeting of Anglicans of the "global south" in Cairo at which Williams had addressed them in conciliatory terms, 12 primates who had been present sent him a letter sharply criticising his leadership which said that "We are troubled by your reluctance to use your moral authority to challenge the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada." The letter acknowledged his eloquence but strongly criticised his reluctance to take sides in the communion's theological crisis and urged him to make explicit threats to those more liberal churches. Questions were later asked about the authority and provenance of the letter as two additional signatories' names had been added although they had left the meeting before it was produced. Subsequently, the Church of Nigeria appointed an American cleric to deal with relations between the United States and Nigerian churches outside the normal channels. Williams expressed his reservations about this to the General Synod of the Church of England.

Williams later established a working party to examine what a "covenant" between the provinces of the Anglican Communion would mean in line with the Windsor Report.

Position on Freemasonry

In a leaked private letter, Williams said that he "had real misgivings about the compatibility ofMasonry

Masonry is the craft of building a structure with brick, stone, or similar material, including mortar plastering which are often laid in, bound, and pasted together by mortar (masonry), mortar. The term ''masonry'' can also refer to the buildin ...

and Christian profession" and that while he was Bishop of Monmouth he had prevented the appointment of Freemasons to senior positions within his diocese. The leaking of this letter in 2003 caused a controversy, which he sought to defuse by apologising for the distress caused and stating that he did not question "the good faith and generosity of individual Freemasons", not least as his father had been a Freemason. However, he also reiterated his concern about Christian ministers adopting "a private system of profession and initiation, involving the taking of oaths of loyalty."

Opinion about hijab and terrorism

Williams objected to a proposed French law banning the wearing of thehijab

Hijab (, ) refers to head coverings worn by Women in Islam, Muslim women. Similar to the mitpaḥat/tichel or Snood (headgear), snood worn by religious married Jewish women, certain Christian head covering, headcoverings worn by some Christian w ...

, a traditional Islamic headscarf for women, in French schools. He said that the hijab and any other religious symbols should not be outlawed.

Williams also spoke up against the scapegoating

Scapegoating is the practice of singling out a person or group for unmerited blame and consequent negative treatment. Scapegoating may be conducted by individuals against individuals (e.g., "he did it, not me!"), individuals against groups (e.g ...

of Muslims in the aftermath of the 7 July 2005 London bombings

The 7 July 2005 London bombings, also referred to as 7/7, were a series of four co-ordinated suicide attacks carried out by Islamist terrorists that targeted commuters travelling on Transport in London, London's public transport during the ...

on underground trains and a bus, which killed 52 and wounded about 700. The initial blame was placed on Al-Qaeda

, image = Flag of Jihad.svg

, caption = Jihadist flag, Flag used by various al-Qaeda factions

, founder = Osama bin Laden{{Assassinated, Killing of Osama bin Laden

, leaders = {{Plainlist,

* Osama bin Lad ...

, but Muslims at large were targeted for reprisals: four mosques in England were assaulted and Muslims were verbally insulted in streets and their cars and houses were vandalised. Williams strongly condemned the terrorist attacks and stated that they could not be justified. However, he added that "any person can commit a crime in the name of religion and it is not particularly Islam to be blamed. Some persons committed deeds in the name of Islam but the deeds contradict Islamic belief and philosophy completely."

Creationism

Williams responded to a controversy regardingcreationism

Creationism is the faith, religious belief that nature, and aspects such as the universe, Earth, life, and humans, originated with supernatural acts of Creation myth, divine creation, and is often Pseudoscience, pseudoscientific.#Gunn 2004, Gun ...

being taught in privately sponsored academies saying that it should not be presented in schools as an alternative to evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. When asked if he was comfortable with the teaching of creationism, he said "I think creationism is, in a sense, a kind of category mistake

A category mistake (or category error, categorical mistake, or mistake of category) is a semantic or ontological error in which things belonging to a particular category are presented as if they belong to a different category, or, alternatively, ...

, as if the Bible were a theory like other theories" and "My worry is creationism can end up reducing the doctrine of creation rather than enhancing it."

Williams has maintained traditional support amongst Anglicans and their leaders for the teaching of evolution as fully compatible with Christianity. This support has dated at least back to Frederick Temple

Frederick Temple (30 November 1821 – 23 December 1902) was an English academic, teacher and Clergy, churchman, who served as Bishop of Exeter (1869–1885), Bishop of London (1885–1896) and Archbishop of Canterbury (1896–1902).

Early ...

's tenure as Archbishop of Canterbury.

Interview with ''Emel'' magazine

In November 2007, Williams gave an interview for ''Emel'' magazine, a British Muslim magazine. Williams condemned the United States and certain Christian groups for their role in the Middle East, while his criticism of some trends withinIslam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

went largely unreported. As reported by ''The Times

''The Times'' is a British Newspaper#Daily, daily Newspaper#National, national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its modern name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its si ...

'', he was greatly critical of the United States, the Iraq War

The Iraq War (), also referred to as the Second Gulf War, was a prolonged conflict in Iraq lasting from 2003 to 2011. It began with 2003 invasion of Iraq, the invasion by a Multi-National Force – Iraq, United States-led coalition, which ...

, and Christian Zionists, yet made "only mild criticisms of the Islamic world". He claimed "the United States wields its power in a way that is worse than Britain during its imperial heyday". He compared Muslims in Britain to the Good Samaritans, and praised the Muslim salat

''Salah'' (, also spelled ''salat'') is the practice of formal ibadah, worship in Islam, consisting of a series of ritual prayers performed at prescribed times daily. These prayers, which consist of units known as rak'a, ''rak'ah'', include ...

ritual of five prayers a day, but said in Muslim nations, the "present political solutions aren't always very impressive".

Sharia law

Williams was the subject of a media and press furore in February 2008 following a lecture he gave to the Temple Foundation at theRoyal Courts of Justice

The Royal Courts of Justice, commonly called the Law Courts, is a court building in Westminster which houses the High Court and Court of Appeal of England and Wales. The High Court also sits on circuit and in other major cities. Designed by Ge ...

Civil and Religious Law in England: a Religious Perspective. 7 February 2008 on the subject of "Islam and English Law". He raised the question of conflicting loyalties which communities might have, cultural, religious and civic. He also argued that theology has a place in debates about the very nature of law "however hard our culture may try to keep it out" and noted that there is, in a "dominant human rights philosophy", a reluctance to acknowledge the liberty of conscientious objection. He spoke of "supplementary jurisdictions" to that of the civil law. Noting the anxieties which the word sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

provoked in the West, he drew attention to the fact that there was a debate within Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

between what he called "primitivists" for whom, for instance, apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

should still be punishable and those Muslims who argued that sharia was a developing system of Islamic jurisprudence

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.Fiqh

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

and that such a view was no longer acceptable. He made comparisons with Orthodox Jewish practice ( beth din) and with the recognition of the exercise of conscience of Christians.

Williams's words were critically interpreted as proposing a parallel jurisdiction to the civil law for Muslims (Sharia) and were the subject of demands from elements of the press and media for his resignation. He also attracted criticism from elements of the Anglican Communion.

In response, Williams stated in a BBC interview that "certain provision of sharia are already recognised in our society and under our law; ... we already have in this country a number of situations in which the internal law of religious communities is recognised by the law of the land as justified conscientious objections in certain circumstances in providing certain kinds of social relations" and that "we have Orthodox Jewish courts operating in this country legally and in a regulated way because there are modes of dispute resolution and customary provisions which apply there in the light of Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

." Williams also denied accusations of proposing a parallel Islamic legal system within Britain. Williams also said of sharia: "In some of the ways it has been codified and practised across the world, it has been appalling and applied to women in places like Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

, it is grim."

Williams's position received more support from the legal community, following a speech given on 4 July 2008 by Nicholas Phillips, Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales

The Lord or Lady Chief Justice of England and Wales is the head of the judiciary of England and Wales and the president of the courts of England and Wales.

Until 2005 the lord chief justice was the second-most senior judge of the English and ...

. He supported the idea that sharia could be reasonably employed as a basis for "mediation or other forms of alternative dispute resolution". He went further to defend the position Williams had taken earlier in the year, explaining that "It was not very radical to advocate embracing sharia law in the context of family disputes, for example, and our system already goes a long way towards accommodating the archbishop's suggestion."; and that "It is possible in this country for those who are entering into a contractual agreement to agree that the agreement shall be governed by a law other than English law." However, some concerns have been raised over the question of how far "embracing" sharia law would be compliant with the UK's obligation under human rights law.

In March 2014, the Law Society of England and Wales

The Law Society of England and Wales (officially The Law Society) is the professional association that represents solicitors for the jurisdiction of England and Wales. It provides services and support to practising and training solicitors, as ...

issued instructions on how to draft sharia-compliant wills for the network of sharia courts which has grown up in Islamic communities to deal with disputes between Muslim families, and so Williams's idea of sharia in the UK was, for a time, seen to bear fruit. The instructions were withdrawn in November 2014.

Comments on the British government

On 8 June 2011, Williams said that the British government was committing Britain to "radical, long-term policies for which no-one voted". Writing in the ''New Statesman

''The New Statesman'' (known from 1931 to 1964 as the ''New Statesman and Nation'') is a British political and cultural news magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first c ...

'' magazine, Williams raised concerns about the coalition's health, education and welfare reforms. He said there was "indignation" due to a lack of "proper public argument". He also said that the " Big Society" idea was viewed with "widespread suspicion", noting also that "we are still waiting for a full and robust account of what the Left would do differently and what a Left-inspired version of localism would look like". The article also said there was concern that the government would abandon its responsibility for tackling child poverty, illiteracy and poor access to the best schools. He also expressed concern about the "quiet resurgence of the seductive language of 'deserving' and 'undeserving' poor" and the steady pressure to increase "what look like punitive responses to alleged abuses of the system

The letter of the law and the spirit of the law are two possible ways to regard rules or laws. To obey the "letter of the law" is to follow the literal reading of the words of the law, whereas following the "spirit of the law" is to follow th ...

". In response, David Cameron

David William Donald Cameron, Baron Cameron of Chipping Norton (born 9 October 1966) is a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 2010 to 2016. Until 2015, he led the first coalition government in the UK s ...

said that he "profoundly disagreed" with Williams's claim that the government was forcing through "radical policies for which no one voted". Cameron said that the government was acting in a "good and moral" fashion and defended the "Big Society" and the coalition's deficit reduction, welfare and education plans. "I am absolutely convinced that our policies are about actually giving people a greater responsibility and greater chances in their life, and I will defend those very vigorously", he said. "By all means let us have a robust debate but I can tell you, it will always be a two-sided debate."

On 26 November 2013, at Clare College, Cambridge, Williams gave the annual T. S. Eliot Lecture, with the title ''Eliot's Christian Society and the Current Political Crisis''. In this, he recalled the poet's assertion that a competent agnostic would make a better prime minister than an incompetent Christian. "I don't know what he would make of our present prime minister", he said. "I have a suspicion that he might have approved of him. I don't find that a very comfortable thought."

Comments on antisemitism

In August 2017, Williams condemnedantisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and backed a petition to remove the works of David Irving

David John Cawdell Irving (born 24 March 1938) is an English author and Holocaust denier who has written on the military and political history of World War II, especially Nazi Germany. He was found to be a Holocaust denier in a British court ...

and other Holocaust denial

Historical negationism, Denial of the Holocaust is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that asserts that the genocide of Jews by the Nazi Party, Nazis is a fabrication or exaggeration. It includes making one or more of the following false claims:

...

books from the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The University of Manchester is c ...

. In a letter to the university, Williams said "At a time when there is, nationally and internationally, a measurable rise in the expression of extremist views I believe this question needs urgent attention."

Climate and ecological crisis

In October 2018, he signed the call to action supportingExtinction Rebellion

Extinction Rebellion (abbreviated as XR) is a UK-founded global environmental movement, with the stated aim of using nonviolent civil disobedience to compel government action to avoid tipping points in the climate system, biodiversity loss, and ...

.

2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

In March 2022, following the2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine