Richard Harris (lichenologist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Richard St John Francis Harris (1 October 1930 – 25 October 2002) was an Irish actor and singer. Having studied at the

Harris starred in a Western for

Harris starred in a Western for  He appeared in another action film, '' Golden Rendezvous'' (1977), based on a novel by Alistair Maclean, shot in South Africa. Harris was sued by the film's producer for his drinking; Harris counter-sued for defamation and the matter was settled out of court. ''Golden Rendezvous'' was a flop but ''

He appeared in another action film, '' Golden Rendezvous'' (1977), based on a novel by Alistair Maclean, shot in South Africa. Harris was sued by the film's producer for his drinking; Harris counter-sued for defamation and the matter was settled out of court. ''Golden Rendezvous'' was a flop but ''

In 1957, Harris married Elizabeth Rees-Williams, daughter of David Rees-Williams, 1st Baron Ogmore. They had three children: actor Jared Harris, actor Jamie Harris, and director

In 1957, Harris married Elizabeth Rees-Williams, daughter of David Rees-Williams, 1st Baron Ogmore. They had three children: actor Jared Harris, actor Jamie Harris, and director

On 30 September 2006, Manuel Di Lucia, of

On 30 September 2006, Manuel Di Lucia, of

''Richard Harris file at Limerick City Library, Ireland''

at the '' World Socialist Web Site'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Harris, Richard 1930 births 2002 deaths 20th-century Irish male actors 20th-century Irish male singers 21st-century Irish male actors Alumni of the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art Audiobook narrators Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actor winners Deaths from lymphoma in England Deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma Dunhill Records artists European Film Awards winners (people) Garryowen Football Club players Grammy Award winners Irish emigrants to the United Kingdom Irish film directors Irish male film actors Irish male radio actors Irish male stage actors Irish male television actors Irish rugby union players Knights of Malta Male actors from Limerick (city) People educated at Crescent College Musicians from Limerick (city) Racquets players University of Scranton faculty Rugby union players from Limerick (city) Fellows of the American Physical Society

London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art

The London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) is a drama school located in Hammersmith, London. It is the oldest specialist drama school in the British Isles and a founding member of the Federation of Drama Schools.

LAMDA's Principal is ...

, he rose to prominence as an icon

An icon () is a religious work of art, most commonly a painting, in the cultures of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Catholic churches. They are not simply artworks; "an icon is a sacred image used in religious devotion". The most ...

of the British New Wave. He received numerous accolades including the Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actor

The Best Actor Award (french: Prix d'interprétation masculine) is an award presented at the Cannes Film Festival since 1946. It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance and chosen by the jury from the films in official co ...

, and a Grammy Award

The Grammy Awards (stylized as GRAMMY), or simply known as the Grammys, are awards presented by the Recording Academy of the United States to recognize "outstanding" achievements in the music industry. They are regarded by many as the most pres ...

. In 2020, he was listed at number 3 on ''The Irish Times

''The Irish Times'' is an Irish daily broadsheet newspaper and online digital publication. It launched on 29 March 1859. The editor is Ruadhán Mac Cormaic. It is published every day except Sundays. ''The Irish Times'' is considered a newspaper ...

''s list of Ireland's greatest film actors.

Harris received two Academy Award for Best Actor

The Academy Award for Best Actor is an award presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). It is given to an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance in a leading role in a film released that year. The ...

nominations for his performances in '' This Sporting Life'' (1963), and '' The Field'' (1990). Other notable roles include in '' The Guns of Navarone'' (1961), '' Red Desert'' (1964), '' A Man Called Horse'' (1970), ''Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

'' (1970), '' Unforgiven'' (1992), ''Gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

'' (2000), and ''The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with ''The Three Musketeers''. Li ...

'' (2002). He gained cross generational acclaim for his role as Albus Dumbledore in the first two ''Harry Potter

''Harry Potter'' is a series of seven fantasy literature, fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young Magician (fantasy), wizard, Harry Potter (character), Harry Potter, and his friends ...

'' films: '' Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone'' (2001) and '' Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets'' (2002), the latter of which was his final film role.

He portrayed King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

in the 1967 film ''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'' based on the Lerner and Loewe musical of the same name. For his performance he received the Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Musical or Comedy

The Golden Globe Award for Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Musical or Comedy is a Golden Globe Award presented annually by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. It is given in honor of an actor who has delivered an outstanding performance i ...

. He reprised the role in the 1981 Broadway musical revival. He received a Laurence Olivier Award for Best Actor for his role in Pirandello's '' Henry IV''.(1991).

Harris received a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited Series or Movie

The Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Limited or Anthology Series or Movie is an award presented annually by the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS). It is given in honor of an actor who has delivered an outstanding pe ...

nomination for his role in '' The Snow Goose'' (1971). Harris had a number-one singing hit in Australia, Jamaica and Canada, and a top-ten hit in the United Kingdom, Ireland, and the United States with his 1968 recording of Jimmy Webb's song "MacArthur Park

MacArthur Park (originally Westlake Park) is a park dating back to the late 19th century in the Westlake, Los Angeles, Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the early 1940s, it was renamed after General Douglas MacArthur, and later designated ...

". He received a Grammy Award for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance nomination for the song.

Early life

Harris was born on 1 October 1930, at Overdale, 8 Landsdown Villas, Ennis Road,Limerick

Limerick ( ; ga, Luimneach ) is a western city in Ireland situated within County Limerick. It is in the province of Munster and is located in the Mid-West which comprises part of the Southern Region. With a population of 94,192 at the 2016 ...

, and was the fifth in a family of eight children, (six boys & two girls), to flour merchant Ivan Harris and Mildred (née Harty). Overdale was "a tall, elegant, early 19th-century redbrick" house with nine bedrooms, in a wealthy part of Limerick, the houses "built at the turn of the 20th century for Limerick's burgeoning middle class... people who could afford properly grand drawing rooms, a bedroom each for the children and one for the pot, plus space for a few servants". He was educated by the Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

at Crescent College. A talented rugby

Rugby may refer to:

Sport

* Rugby football in many forms:

** Rugby league: 13 players per side

*** Masters Rugby League

*** Mod league

*** Rugby league nines

*** Rugby league sevens

*** Touch (sport)

*** Wheelchair rugby league

** Rugby union: 1 ...

player, he appeared on several Munster Junior and Senior Cup teams for Crescent, and played for Garryowen. Harris's athletic career was cut short when he caught tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

in his teens. He remained an ardent fan of the Munster Rugby and Young Munster teams until his death, attending many of their matches, and there are numerous stories of japes at rugby matches with actors and fellow rugby fans Peter O'Toole

Peter Seamus O'Toole (; 2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was a British stage and film actor. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic ...

and Richard Burton.

After recovering from tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, Harris moved to Great Britain, wanting to become a director. He could not find any suitable training courses, and enrolled in the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art

The London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art (LAMDA) is a drama school located in Hammersmith, London. It is the oldest specialist drama school in the British Isles and a founding member of the Federation of Drama Schools.

LAMDA's Principal is ...

to learn acting. He had failed an audition at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and had been rejected by the Central School of Speech and Drama, because they felt he was too old at 24. While still a student, he rented the tiny "off- West End" Irving Theatre, and there directed his own production of Clifford Odets's play ''Winter Journey (The Country Girl)''.

After completing his studies at the academy, he joined Joan Littlewood's Theatre Workshop. He began getting roles in West End theatre productions, starting with '' The Quare Fellow'' in 1956, a transfer from the Theatre Workshop. He spent nearly a decade in obscurity, learning his profession on stages throughout the UK.

Career

1959–1963: Early roles and breakthrough

Harris made his film debut in 1959 in the film '' Alive and Kicking'', and played the lead role in '' The Ginger Man'' in the West End in 1959. In his second film he had a small role as an IRA Volunteer in ''Shake Hands with the Devil ''Shake Hands with the Devil'' may refer to:

* ''Shake Hands with the Devil'' (1959 film), American drama set in 1921 Ireland

* ''Shake Hands with the Devil'' (album), Kris Kristofferson 1979 release on Monument Records

* ''Shake Hands with the ...

'' (1959), supporting James Cagney

James Francis Cagney Jr. (; July 17, 1899March 30, 1986) was an American actor, dancer and film director. On stage and in film, Cagney was known for his consistently energetic performances, distinctive vocal style, and deadpan comic timing. He ...

. The film was shot in Ireland and directed by Michael Anderson who offered Harris a role in his next movie, ''The Wreck of the Mary Deare

''The Wreck of the Mary Deare'' (in the UK published as ''The Mary Deare'') is a 1956 novel written by British author Hammond Innes, which was later adapted as a film starring Gary Cooper released in 1959 by MGM. According to Jack Adrian, the ...

'' (1959), shot in Hollywood.

Harris played another IRA Volunteer in '' A Terrible Beauty'' (1960), alongside Robert Mitchum. He had a memorable bit part

In acting, a bit part is a role in which there is direct interaction with the principal actors and no more than five lines of dialogue, often referred to as a five-or-less or under-five in the United States, or under sixes in British television, ...

in the film '' The Guns of Navarone'' (1961) as a Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

pilot who reports that blowing up the "bloody guns" of the island of Navarone is impossible by an air raid. He had a larger part in '' The Long and the Short and the Tall'' (1961), playing a British soldier; Harris clashed with Laurence Harvey

Laurence Harvey (born Zvi Mosheh Skikne; 1 October 192825 November 1973) was a Lithuanian-born British actor and film director. He was born to Lithuanian Jewish parents and emigrated to South Africa at an early age, before later settling in th ...

and Richard Todd during filming. For his role in the film '' Mutiny on the Bounty'' (1962), despite being virtually unknown to film audiences, Harris reportedly insisted on third billing, behind Trevor Howard and Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Considered one of the most influential actors of the 20th century, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, which spanned six decades, including two Academ ...

, an actor he greatly admired. However, Harris fell out with Brando over the latter's behaviour during the film's production.

Harris's first starring role was in the film '' This Sporting Life'' (1963), as a bitter young coal miner, Frank Machin, who becomes an acclaimed rugby league

Rugby league football, commonly known as just rugby league and sometimes football, footy, rugby or league, is a full-contact sport played by two teams of thirteen players on a rectangular field measuring 68 metres (75 yards) wide and 112 ...

football player. It was based on the novel by David Storey and directed by Lindsay Anderson. For his role, Harris won Best Actor

Best Actor is the name of an award which is presented by various film, television and theatre organizations, festivals, and people's awards to leading actors in a film, television series, television film or play.

The term most often refers to th ...

in 1963 at the Cannes Film Festival

The Cannes Festival (; french: link=no, Festival de Cannes), until 2003 called the International Film Festival (') and known in English as the Cannes Film Festival, is an annual film festival held in Cannes, France, which previews new films o ...

and an Academy Award nomination

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

. Harris followed this with a leading role in the Italian film, Michelangelo Antonioni

Michelangelo Antonioni (, ; 29 September 1912 – 30 July 2007) was an Italian filmmaker. He is best known for directing his "trilogy on modernity and its discontents"—''L'Avventura'' (1960), ''La Notte'' (1961), and ''L'Eclisse'' (1962 ...

's ''Il Deserto Rosso

''Red Desert'' ( it, Il deserto rosso) is a 1964 drama film directed by Michelangelo Antonioni and starring Monica Vitti with Richard Harris. Written by Antonioni and Tonino Guerra, it was Antonioni's first color film. The story follows a trouble ...

'' (''Red Desert'', 1964). This won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival.

Harris received an offer to support Kirk Douglas

Kirk Douglas (born Issur Danielovitch; December 9, 1916 – February 5, 2020) was an American actor and filmmaker. After an impoverished childhood, he made his film debut in ''The Strange Love of Martha Ivers'' (1946) with Barbara Stanwyck. Do ...

in a British war film, ''The Heroes of Telemark

''The Heroes of Telemark'' is a 1965 British war film directed by Anthony Mann based on the true story of the Norwegian heavy water sabotage during the Second World War from ''Skis Against the Atom'', the memoirs of Norwegian resistance soldier ...

'' (1965), directed by Anthony Mann

Anthony Mann (born Emil Anton Bundsmann; June 30, 1906 – April 29, 1967) was an American film director and stage actor.

Mann initially started as a theatre actor appearing in numerous stage productions. In 1937, he moved to Hollywood where ...

, playing a Norwegian resistance leader. He then went to Hollywood to support Charlton Heston

Charlton Heston (born John Charles Carter; October 4, 1923April 5, 2008) was an American actor and political activist.

As a Hollywood star, he appeared in almost 100 films over the course of 60 years. He played Moses in the epic film ''The Ten C ...

in Sam Peckinpah

David Samuel Peckinpah (; February 21, 1925 – December 28, 1984) was an American film director and screenwriter. His 1969 Western epic ''The Wild Bunch'' received an Academy Award nomination and was ranked No. 80 on the American Film Institute ...

's '' Major Dundee'' (1965), as an Irish immigrant who became a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

cavalryman during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

. He played Cain

Cain ''Káïn''; ar, قابيل/قايين, Qābīl/Qāyīn is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He wa ...

in John Huston

John Marcellus Huston ( ; August 5, 1906 – August 28, 1987) was an American film director, screenwriter, actor and visual artist. He wrote the screenplays for most of the 37 feature films he directed, many of which are today considered ...

's film '' The Bible: In the Beginning...'' (1966). More successful at the box office was ''Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

'' (1966), in which Harris starred alongside Julie Andrews

Dame Julie Andrews (born Julia Elizabeth Wells; 1 October 1935) is an English actress, singer, and author. She has garnered numerous accolades throughout her career spanning over seven decades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Fi ...

and Max von Sydow.

1967–1971: Rise to prominence

As a change of pace, he was the romantic lead in aDoris Day

Doris Day (born Doris Mary Kappelhoff; April 3, 1922 – May 13, 2019) was an American actress, singer, and activist. She began her career as a big band singer in 1939, achieving commercial success in 1945 with two No. 1 recordings, " Sent ...

spy spoof comedy, '' Caprice'' (1967), directed by Frank Tashlin

Frank Tashlin (born Francis Fredrick von Taschlein, February 19, 1913 – May 5, 1972), also known as Tish Tash and Frank Tash, was an American animator, cartoonist, children's writer, illustrator, screenwriter, and film director. He was best kn ...

. Harris next performed the role of King Arthur

King Arthur ( cy, Brenin Arthur, kw, Arthur Gernow, br, Roue Arzhur) is a legendary king of Britain, and a central figure in the medieval literary tradition known as the Matter of Britain.

In the earliest traditions, Arthur appears as a ...

in the film adaptation of the musical play ''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'' (1967). Critic Roger Ebert

Roger Joseph Ebert (; June 18, 1942 – April 4, 2013) was an American film critic, film historian, journalist, screenwriter, and author. He was a film critic for the ''Chicago Sun-Times'' from 1967 until his death in 2013. In 1975, Ebert beca ...

described the casting of Harris and Vanessa Redgrave

Dame Vanessa Redgrave (born 30 January 1937) is an English actress and activist. Throughout her career spanning over seven decades, Redgrave has garnered numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a British Academy Television Award, two ...

as "about the best King Arthur and Queen Guenevere I can imagine". Harris revived the role on Broadway at the Winter Garden Theatre

The Winter Garden Theatre is a Broadway theatre at 1634 Broadway in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It opened in 1911 under designs by architect William Albert Swasey. The Winter Garden's current design dates to 1922, when ...

from 15 November 1981, to 2 January 1982, and broadcast on HBO

Home Box Office (HBO) is an American premium television network, which is the flagship property of namesake parent subsidiary Home Box Office, Inc., itself a unit owned by Warner Bros. Discovery. The overall Home Box Office business unit is ba ...

a year later. Starring Meg Bussert

Meg Bussert (born October 21, 1949) is an American actress, singer and a university professor.

Early life

Born in Chicago, Illinois,Richard Muenz

Richard Muenz (born March 9, 1948) is an American actor and baritone who is mostly known for his work within American theatre. Muenz has frequently performed in musicals and in concerts. He has also periodically acted on television.

Early life an ...

as Lancelot and Thor Fields

Thor Fields (born September 19, 1968) is an American actor and guitarist.

Career

Fields began his career in television commercials and made his Broadway debut in ''The King and I'' in 1978. This was the first revival starring Yul Brynner and C ...

as Tom of Warwick. Harris, who had starred in the film, and Muenz also took the show on tour nationwide.

In ''The Molly Maguires

''The Molly Maguires'' is a 1970 American historical drama film directed by Martin Ritt, starring Richard Harris and Sean Connery.''Variety Film Reviews, Variety'' film review; January 21, 1970, page 18. It is based on the 1964 book ''Lament for ...

'' (1970), he played James McParland

James McParland (''né'' McParlan; 1844, County Armagh, Ireland – 18 May 1919, Denver, Colorado) was an American private detective and Pinkerton agent.

McParland arrived in New York in 1867. He worked as a laborer, policeman and then in Chica ...

, the detective who infiltrates the title organisation, headed by Sean Connery

Sir Sean Connery (born Thomas Connery; 25 August 1930 – 31 October 2020) was a Scottish actor. He was the first actor to portray fictional British secret agent James Bond on film, starring in seven Bond films between 1962 and 1983. Origina ...

. It was a box office flop. However '' A Man Called Horse'' (1970), with Harris in the title role, an 1825 English aristocrat who is captured by Native Americans, was a major success. He played the title role in the film ''Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three Ki ...

'' in 1970 opposite Alec Guinness

Sir Alec Guinness (born Alec Guinness de Cuffe; 2 April 1914 – 5 August 2000) was an English actor. After an early career on the stage, Guinness was featured in several of the Ealing comedies, including ''Kind Hearts and Coronets'' (194 ...

as King Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of England, Scotland, and Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649. He was born into the House of Stuart as the second son of King James VI of ...

. That year British exhibitors voted him the 9th-most popular star at the UK box office.

In 1971 Harris starred in a BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

TV film adaptation '' The Snow Goose'', from a screenplay by Paul Gallico. It won a Golden Globe

The Golden Globe Awards are accolades bestowed by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association beginning in January 1944, recognizing excellence in both American and international film and television. Beginning in 2022, there are 105 members of t ...

for Best Movie made for TV and was nominated for both a BAFTA and an Emmy

The Emmy Awards, or Emmys, are an extensive range of awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international television industry. A number of annual Emmy Award ceremonies are held throughout the calendar year, each with the ...

. and was shown in the U.S. as part of the ''Hallmark Hall of Fame

''Hallmark Hall of Fame'', originally called ''Hallmark Television Playhouse'', is an anthology program on American television, sponsored by Hallmark Cards, a Kansas City-based greeting card company. The longest-running prime-time series in t ...

''. He made his directorial debut with '' Bloomfield'' (1971) and starred in ''Man in the Wilderness

''Man in the Wilderness'' is a 1971 American revisionist Western film about a scout for a group of mountain men who are traversing the Northwestern United States during the 1820s. The scout is mauled by a bear and left to die by his companions ...

'' (1971), a revisionist Western based on the Hugh Glass

Hugh Glass ( 1783 – 1833) was an American frontiersman, fur trapper, trader, hunter and explorer. He is best known for his story of survival and forgiveness after being left for dead by companions when he was mauled by a grizzly bear.

No rec ...

story.

1973–1981: Established actor

Harris starred in a Western for

Harris starred in a Western for Samuel Fuller

Samuel Michael Fuller (August 12, 1912 – October 30, 1997) was an American film director, screenwriter, novelist, journalist, and World War II veteran known for directing low-budget B movie, genre movies with controversial themes, often ...

, ''Riata'', which stopped production several weeks into filming. The project was re-assembled with a new director and cast, except for Harris, who returned: ''The Deadly Trackers

''The Deadly Trackers'' is a 1973 American Western film directed by Barry Shear and starring Richard Harris, Rod Taylor and Al Lettieri. It is based on the novel ''Riata'' by Samuel Fuller.

Plot

Sheriff Sean Kilpatrick (Harris) is a pacifist ...

'' (1973). In 1973, Harris published a book of poetry, ''I, In the Membership of My Days'', which was later reissued in part in an audio LP format, augmented by self-penned songs such as "I Don't Know".

Harris starred in two thrillers: ''99 and 44/100% Dead

''99 and 44/100% Dead!'' is a 1974 American action comedy film directed by John Frankenheimer and starring Richard Harris. The title is a play on an advertising slogan for Ivory soap.

Plot

Harry Crown, a stylish professional hit man with a pair ...

'' (1974), for John Frankenheimer, and ''Juggernaut

A juggernaut (), in current English usage, is a literal or metaphorical force regarded as merciless, destructive, and unstoppable. This English usage originated in the mid-nineteenth century and was adapted from the Sanskrit word Jagannath.

...

'' (1974), for Richard Lester. In ''Echoes of a Summer

''Echoes of a Summer'' is a 1976 Canadian-American family drama film directed by Don Taylor, based on the play ''Isle of Children'' by Robert L. Joseph, who also adapted the screenplay. It stars Jodie Foster, Richard Harris, Lois Nettleton, Br ...

'' (1976) he played the father of a young girl with a terminal illness. He had a cameo as Richard the Lionheart in '' Robin and Marian'' (1976), for Lester, then was in ''The Return of a Man Called Horse

''The Return of a Man Called Horse'' is a 1976 Western film directed by Irvin Kershner and written by Jack DeWitt. It is a sequel to the 1970 film '' A Man Called Horse'', in turn based on Dorothy M. Johnson’s short story of the same name, w ...

'' (1976). Harris led the all-star cast in the train disaster film '' The Cassandra Crossing'' (1976). He played Gulliver in the part-animated ''Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

'' (1977) and was reunited with Michael Anderson in ''Orca

The orca or killer whale (''Orcinus orca'') is a toothed whale belonging to the oceanic dolphin family, of which it is the largest member. It is the only Extant taxon, extant species in the genus ''Orcinus'' and is recognizable by its black ...

'' (1977), battling a killer whale.

He appeared in another action film, '' Golden Rendezvous'' (1977), based on a novel by Alistair Maclean, shot in South Africa. Harris was sued by the film's producer for his drinking; Harris counter-sued for defamation and the matter was settled out of court. ''Golden Rendezvous'' was a flop but ''

He appeared in another action film, '' Golden Rendezvous'' (1977), based on a novel by Alistair Maclean, shot in South Africa. Harris was sued by the film's producer for his drinking; Harris counter-sued for defamation and the matter was settled out of court. ''Golden Rendezvous'' was a flop but ''The Wild Geese

''The Wild Geese'' is a 1978 war film directed by Andrew V. McLaglen and starring Richard Burton, Roger Moore, Richard Harris, and Hardy Krüger. The screenplay concerns a group of mercenaries in Africa. It was the result of a long-held ambit ...

'' (1978), where Harris played one of several mercenaries, was a big success outside America. '' Ravagers'' (1979) was more action, set in a post-apocalyptic world. '' Game for Vultures'' (1979) was set in Rhodesia and shot in South Africa.

In Hollywood he appeared in '' The Last Word'' (1979), then supported Bo Derek in '' Tarzan, the Ape Man'' (1981). He made a film in Canada, ''Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid

''Your Ticket is No Longer Valid'' is a 1981 Canadian film directed by George Kaczender and starring Richard Harris, George Peppard, Jennifer Dale, and Jeanne Moreau. Harris later regarded the film as one of the biggest artistic disappointments o ...

'' (1981), a drama about impotence. He followed it with another Canadian film, ''Highpoint Highpoint can refer to:

*Highpoint, Florida, an unincorporated community near Tampa Bay

*Highpoint Shopping Centre in Melbourne, Australia

*Highpoint (building), an apartment building in London, United Kingdom.

*Highpoint I, a set of 1930s apartment ...

'', a movie so bad it was not released for several years.

1980–1988: Continued success

For a while in the 1980s, Harris went into semi-retirement onParadise Island

Paradise Island is an island in The Bahamas formerly known as Hog Island. The island, with an area of (2.8 km2/1.1 sq mi), is located just off the shore of the city of Nassau, which is itself located on the northern edge of the island of ...

, in the Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, where he kicked his drinking habit and embraced a healthier lifestyle. It had a beneficial effect. Harris's career was revived by his success on stage in ''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'', and powerful performance in the West End run of Pirandello's '' Henry IV''.

He was the subject of ''This Is Your Life This Is Your Life may refer to:

Television

* ''This Is Your Life'' (American franchise), an American radio and television documentary biography series hosted by Ralph Edwards

* ''This Is Your Life'' (Australian TV series), the Australian versio ...

'' in 1990, when he was surprised by Michael Aspel during the curtain call of the Pirandello's play ''Henry IV'' at the Wyndham's Theatre in London.

Over several years in the late 1980s, Harris worked with Irish author Michael Feeney Callan

Michael Feeney Callan is an Irish novelist and poet. An award winner for his short fiction and also for non-fiction, he joined BBC television drama as a story editor, and wrote screenplays for ''The Professionals'', and for American television.

...

on his biography, which was published by Sidgwick & Jackson in 1990. His film work during this period included: '' Triumphs of a Man Called Horse'' (1983), ''Martin's Day

''Martin's Day'' is a 1985 American drama film directed by Alan Gibson. It stars Richard Harris and Lindsay Wagner.

Synopsis

The film follows an escaped convict named Martin who kidnaps a boy, also named Martin, while trying to flee via plane. W ...

'' (1985), ''Strike Commando 2'' (1988), ''King of the Wind

''King of the Wind'' is a novel by Marguerite Henry that won the Newbery Medal for excellence in American children's literature in 1949. It was made into a film of the same name in 1990.

'' (1990) and ''Mack the Knife

"Mack the Knife" or "The Ballad of Mack the Knife" (german: "Die Moritat von Mackie Messer", italic=no, link=no) is a song composed by Kurt Weill with lyrics by Bertolt Brecht for their 1928 music drama ''The Threepenny Opera'' (german: Die Dreig ...

'' (1990) (a film version of ''The Threepenny Opera

''The Threepenny Opera'' ( ) is a "play with music" by Bertolt Brecht, adapted from a translation by Elisabeth Hauptmann of John Gay's 18th-century English ballad opera, ''The Beggar's Opera'', and four ballads by François Villon, with music ...

'' in which he played J.J. Peachum ) plus the TV film version of Maigret, opposite Barbara Shelley. This indicated declining popularity which Harris told his biographer, Michael Feeney Callan

Michael Feeney Callan is an Irish novelist and poet. An award winner for his short fiction and also for non-fiction, he joined BBC television drama as a story editor, and wrote screenplays for ''The Professionals'', and for American television.

...

, he was "utterly reconciled to".

1989–2002: Stardom and final roles

In June 1989, director Jim Sheridan cast Harris in the lead role in '' The Field'', written by the esteemed Irish playwrightJohn B. Keane

John Brendan Keane (21 July 1928 – 30 May 2002) was an Irish playwright, novelist and essayist from Listowel, County Kerry.

Biography

A son of a national school teacher, William B. Keane, and his wife Hannah (née Purtill), Keane was ...

. The lead role of "Bull" McCabe was to be played by former Abbey Theatre

The Abbey Theatre ( ga, Amharclann na Mainistreach), also known as the National Theatre of Ireland ( ga, Amharclann Náisiúnta na hÉireann), in Dublin, Ireland, is one of the country's leading cultural institutions. First opening to the pu ...

actor Ray McAnally. When McAnally died suddenly on 15 June 1989, Harris was offered the McCabe role. ''The Field'' was released in 1990 and earned Harris his second Academy Award nomination for Best Actor. He lost to Jeremy Irons for ''Reversal of Fortune

''Reversal of Fortune'' is a 1990 American drama film adapted from the 1985 book ''Reversal of Fortune: Inside the von Bülow Case'', written by law professor Alan Dershowitz. It recounts the true story of the unexplained coma of socialite Sunny ...

''. In 1992, Harris had a supporting role in the film '' Patriot Games''. He had good roles in '' Unforgiven'' (1992), ''Wrestling Ernest Hemingway

''Wrestling Ernest Hemingway'' is a 1993 American romantic drama film written by Steve Conrad and directed by Randa Haines, starring Richard Harris, Robert Duvall, Sandra Bullock, Shirley MacLaine, and Piper Laurie. The film is about two elder ...

'' (1993) and ''Silent Tongue

''Silent Tongue'' is a 1994 American Western horror film written and directed by Sam Shepard. It was filmed in the spring of 1992, but not released until 1994. It was filmed near Roswell, New Mexico and features Richard Harris, Sheila Tousey, ...

'' (1994). He played the title role in ''Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

'' (1994) and had the lead in ''Cry, the Beloved Country

''Cry, the Beloved Country'' is a 1948 novel by South African writer Alan Paton. Set in the prelude to apartheid in South Africa, it follows a black village priest and a white farmer who must deal with news of a murder.

American publisher Benne ...

'' (1995).

A lifelong supporter of Jesuit education principles, Harris established a friendship with University of Scranton President Rev. J. A. Panuska and raised funds for a scholarship for Irish students established in honour of his brother and manager, Dermot, who had died the previous year of a heart attack. He chaired acting workshops and cast the university's production of ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

'' in November 1987.

Harris appeared in two films which won the Academy Award for Best Picture

The Academy Award for Best Picture is one of the Academy Awards presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) since the awards debuted in 1929. This award goes to the producers of the film and is the only category ...

: firstly as the gunfighter "English Bob" in the revisionist Western '' Unforgiven'' (1992); secondly as the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

in Ridley Scott

Sir Ridley Scott (born 30 November 1937) is a British film director and producer. Directing, among others, science fiction films, his work is known for its atmospheric and highly concentrated visual style. Scott has received many accolades thr ...

's ''Gladiator

A gladiator ( la, gladiator, "swordsman", from , "sword") was an armed combatant who entertained audiences in the Roman Republic and Roman Empire in violent confrontations with other gladiators, wild animals, and condemned criminals. Some gla ...

'' (2000). He also played a lead role alongside James Earl Jones

James Earl Jones (born January 17, 1931) is an American actor. He has been described as "one of America's most distinguished and versatile" actors for his performances in film, television, and theater, and "one of the greatest actors in America ...

in the Darrell Roodt film adaptation of ''Cry, the Beloved Country

''Cry, the Beloved Country'' is a 1948 novel by South African writer Alan Paton. Set in the prelude to apartheid in South Africa, it follows a black village priest and a white farmer who must deal with news of a murder.

American publisher Benne ...

'' (1995). In 1999, Harris starred in the film ''To Walk with Lions

''To Walk with Lions'' is a 1999 film directed by Carl Schultz and starring Richard Harris as George Adamson and John Michie as Tony Fitzjohn. It follows the later years of Lion advocate Adamson.

After his marriage to Joy Adamson of ''Born Free'' ...

''. After ''Gladiator'', Harris played the supporting role of Albus Dumbledore in the first two of the ''Harry Potter

''Harry Potter'' is a series of seven fantasy literature, fantasy novels written by British author J. K. Rowling. The novels chronicle the lives of a young Magician (fantasy), wizard, Harry Potter (character), Harry Potter, and his friends ...

'' films, '' Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone'' (2001) and '' Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets'' (2002), the latter of which was his final film role. Harris portrayed Abbé Faria

Abbé Faria (), or Abbé (Abbot) (born José Custódio de Faria; 31 May 1756 – 20 September 1819), was a Luso- Goan Catholic monk who was one of the pioneers of the scientific study of hypnotism, following on from the work of Franz Mesmer ...

in Kevin Reynolds' film adaptation of ''The Count of Monte Cristo

''The Count of Monte Cristo'' (french: Le Comte de Monte-Cristo) is an adventure novel written by French author Alexandre Dumas (''père'') completed in 1844. It is one of the author's more popular works, along with ''The Three Musketeers''. Li ...

'' (2002). The film '' Kaena: The Prophecy'' (2003) was dedicated to him posthumously as he had voiced the character Opaz before his death.

Harris hesitated to take the role of Dumbledore in '' Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone'' (2001) owing to the multi-film commitment and his declining health, but he ultimately accepted because, according to his account of the story, his 11-year-old granddaughter threatened never to speak to him again if he did not take it. In an interview with the ''Toronto Star

The ''Toronto Star'' is a Canadian English-language broadsheet daily newspaper. The newspaper is the country's largest daily newspaper by circulation. It is owned by Toronto Star Newspapers Limited, a subsidiary of Torstar Corporation and part ...

'' in 2001, Harris expressed his concern that his association with the ''Harry Potter'' films would outshine the rest of his career. He explained, "Because, you see, I don't just want to be remembered for being in those bloody films, and I'm afraid that's what's going to happen to me."

Harris also made part of the Bible TV movie project filmed as a cinema production for the TV, a project produced by Lux Vide Italy with the collaboration of RAI and Channel 5 of France, and premiered in the United States in the channel TNT in the 1990s. He portrayed the main and title character

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

in the production ''Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the special relationship between the Jew ...

'' (1993) as well as Saint John of Patmos in the 2000 TV film production ''Apocalypse

Apocalypse () is a literary genre in which a supernatural being reveals cosmic mysteries or the future to a human intermediary. The means of mediation include dreams, visions and heavenly journeys, and they typically feature symbolic imager ...

''.

Singing career

Harris recorded several albums of music, one of which, ''A Tramp Shining

''A Tramp Shining'' is the debut album of Richard Harris, released in 1968 by Dunhill Records. The album was written, arranged, and produced by singer-songwriter Jimmy Webb. Although Harris sang several numbers on the soundtrack album to the film ...

'', included the seven-minute hit song "MacArthur Park

MacArthur Park (originally Westlake Park) is a park dating back to the late 19th century in the Westlake, Los Angeles, Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the early 1940s, it was renamed after General Douglas MacArthur, and later designated ...

" (Harris insisted on singing the lyric as "MacArthur's Park"). This song was written by Jimmy Webb, and it reached number 2 on the American ''Billboard

A billboard (also called a hoarding in the UK and many other parts of the world) is a large outdoor advertising structure (a billing board), typically found in high-traffic areas such as alongside busy roads. Billboards present large advertise ...

'' Hot 100

The ''Billboard'' Hot 100 is the music industry standard record chart in the United States for songs, published weekly by '' Billboard'' magazine. Chart rankings are based on sales (physical and digital), radio play, and online streaming ...

chart. It also topped several music sales charts in Europe during the summer of 1968. "MacArthur Park" sold over one million copies and was awarded a gold disc. A second album, also consisting entirely of music composed by Webb, '' The Yard Went on Forever'', was released in 1969. In the 1973 TV special "Burt Bacharach

Burt Freeman Bacharach ( ; born May 12, 1928) is an American composer, songwriter, record producer and pianist who composed hundreds of pop songs from the late 1950s through the 1980s, many in collaboration with lyricist Hal David. A six-time Gra ...

in Shangri-La", after singing Webb's "Didn't We", Harris tells Bacharach that since he was not a trained singer he approached songs as an actor concerned with words and emotions, acting the song with the sort of honesty the song is trying to convey. Then he proceeds to sing "If I Could Go Back", from the ''Lost Horizon

''Lost Horizon'' is a 1933 novel by English writer James Hilton. The book was turned into a film, also called ''Lost Horizon'', in 1937 by director Frank Capra. It is best remembered as the origin of Shangri-La, a fictional utopian lamaser ...

'' soundtrack.

Personal life

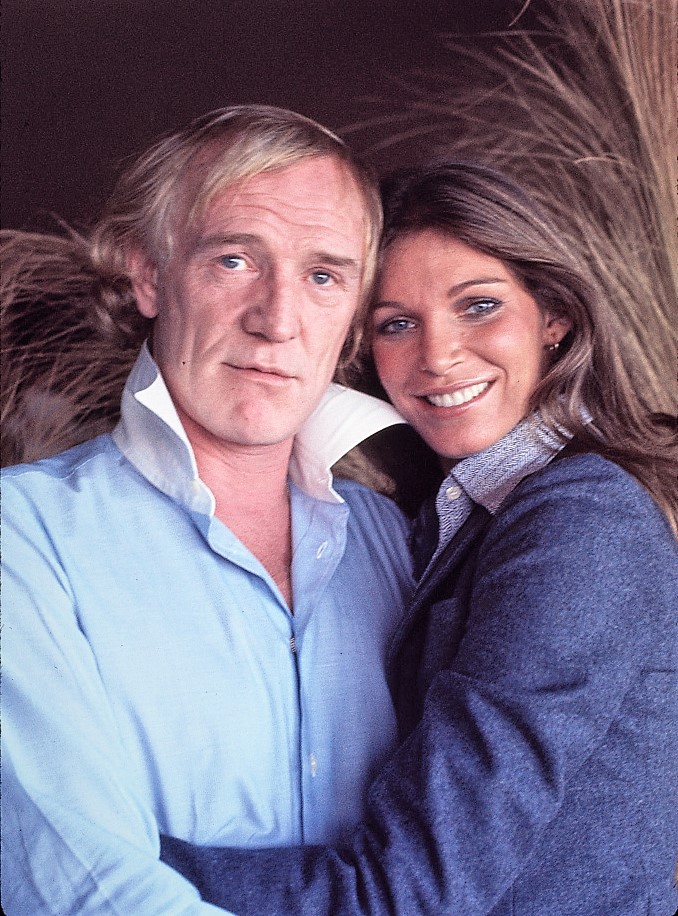

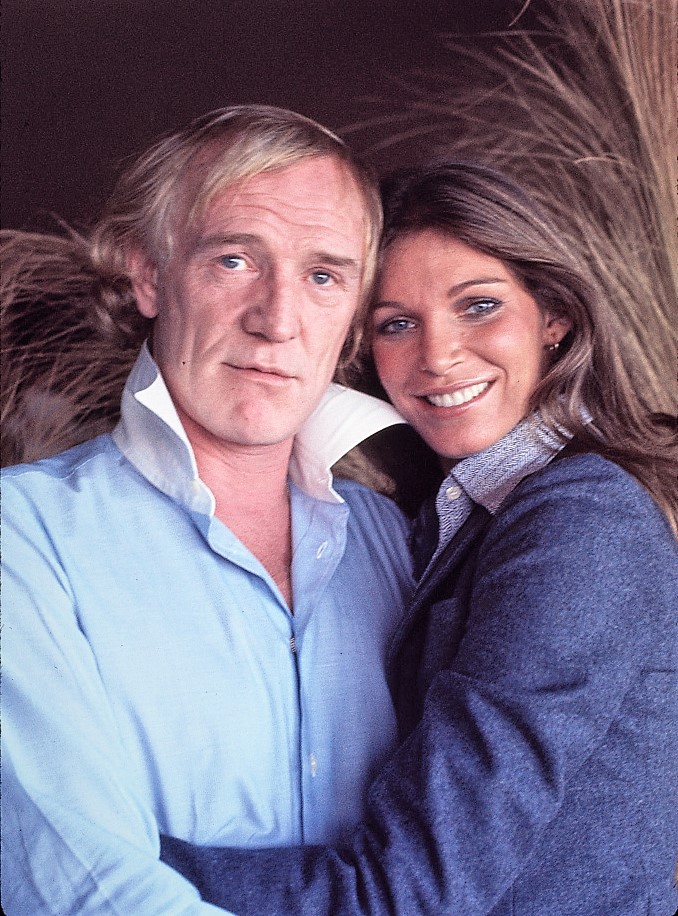

In 1957, Harris married Elizabeth Rees-Williams, daughter of David Rees-Williams, 1st Baron Ogmore. They had three children: actor Jared Harris, actor Jamie Harris, and director

In 1957, Harris married Elizabeth Rees-Williams, daughter of David Rees-Williams, 1st Baron Ogmore. They had three children: actor Jared Harris, actor Jamie Harris, and director Damian Harris

Damian David Harris (born 2 August 1958) is a British film director and screenwriter. He is the eldest son of the actor Richard Harris and socialite Elizabeth Rees-Williams.

Career

In 1968, Harris debuted on screen playing Miles in the film ' ...

. Harris and Rees-Williams divorced in 1969, after which Elizabeth married Rex Harrison

Sir Reginald Carey "Rex" Harrison (5 March 1908 – 2 June 1990) was an English actor. Harrison began his career on the stage in 1924. He made his West End debut in 1936 appearing in the Terence Rattigan play ''French Without Tears'', in what ...

. Harris's second marriage was to the American actress Ann Turkel

Ann Kathryn Turkel (born July 16, 1946) is an American actress and former model. Turkel studied acting at the Musical Theatre Academy.

Life and career

Turkel was born in New York City to a Jewish family. She was photographed for American ''Vog ...

in 1974, they divorced in 1982.

Harris was a member of the Knights of Malta

The Sovereign Military Order of Malta (SMOM), officially the Sovereign Military Hospitaller Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, of Rhodes and of Malta ( it, Sovrano Militare Ordine Ospedaliero di San Giovanni di Gerusalemme, di Rodi e di Malta; ...

.

Harris paid £75,000 for William Burges

William Burges (; 2 December 1827 – 20 April 1881) was an English architect and designer. Among the greatest of the Victorian art-architects, he sought in his work to escape from both nineteenth-century industrialisation and the Neoc ...

' Tower House

A tower house is a particular type of stone structure, built for defensive purposes as well as habitation. Tower houses began to appear in the Middle Ages, especially in mountainous or limited access areas, in order to command and defend strateg ...

in Holland Park in 1968, after discovering that the American entertainer Liberace

Władziu Valentino Liberace (May 16, 1919 – February 4, 1987) was an American pianist, singer, and actor. A child prodigy born in Wisconsin to parents of Italian and Polish origin, he enjoyed a career spanning four decades of concerts, recordi ...

had arranged to buy the house but had not yet put down a deposit. Harris employed the original decorators, Campbell Smith & Company Ltd., to carry out extensive restoration work on the interior.

Harris was a vocal supporter of the Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reun ...

(PIRA) from 1973 until 1984. In January 1984, remarks he made on the previous month's Harrods bombing caused great controversy, after which he discontinued his support for the PIRA.

At the height of his stardom in the 1960s and early 1970s, Harris was almost as well known for his hellraiser lifestyle and heavy drinking as he was for his acting career. He was a longtime alcoholic until he became a teetotaller in 1981. Nevertheless, he did resume drinking Guinness

Guinness () is an Irish dry stout that originated in the brewery of Arthur Guinness at St. James's Gate, Dublin, Ireland, in 1759. It is one of the most successful alcohol brands worldwide, brewed in almost 50 countries, and available in ove ...

a decade later. He gave up drugs after almost dying from a cocaine

Cocaine (from , from , ultimately from Quechuan languages, Quechua: ''kúka'') is a central nervous system (CNS) stimulant mainly recreational drug use, used recreationally for its euphoria, euphoric effects. It is primarily obtained from t ...

overdose in 1978.

Illness and death

Harris was diagnosed withHodgkin's disease

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma, in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the patient's lymph nodes. The condition wa ...

in August 2002, reportedly after being hospitalised with pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

. He died at University College Hospital

University College Hospital (UCH) is a teaching hospital in the Fitzrovia area of the London Borough of Camden, England. The hospital, which was founded as the North London Hospital in 1834, is closely associated with University College London ...

in Bloomsbury

Bloomsbury is a district in the West End of London. It is considered a fashionable residential area, and is the location of numerous cultural, intellectual, and educational institutions.

Bloomsbury is home of the British Museum, the largest mus ...

, London, on 25 October 2002, aged 72. Harris had quipped that "It was the food!" as he was wheeled out of the Savoy Hotel for the last time. Harris spent his final three days in a coma. Harris's body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered in The Bahamas

The Bahamas (), officially the Commonwealth of The Bahamas, is an island country within the Lucayan Archipelago of the West Indies in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic. It takes up 97% of the Lucayan Archipelago's land area and is home to ...

, where he owned a home.

Harris was a lifelong friend of actor Peter O'Toole

Peter Seamus O'Toole (; 2 August 1932 – 14 December 2013) was a British stage and film actor. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and began working in the theatre, gaining recognition as a Shakespearean actor at the Bristol Old Vic ...

, and his family reportedly hoped that O'Toole would replace Harris as Dumbledore in ''Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

''Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban'' is a fantasy novel written by British author J. K. Rowling and is the third in the ''Harry Potter'' series. The book follows Harry Potter, a young wizard, in his third year at Hogwarts School of W ...

'' (2004). There were, however, concerns about insuring O'Toole for the six remaining films in the series. Harris was ultimately succeeded as Dumbledore by Michael Gambon

Sir Michael John Gambon (; born 19 October 1940) is an Irish-English actor. Regarded as one of Ireland and Britain's most distinguished actors, he is known for his work on stage and screen. Gambon started his acting career with Laurence Olivi ...

. Chris Columbus, director of the first two ''Harry Potter'' films, had visited Harris during his last days and had promised not to recast Dumbledore, confident of his eventual recovery. In a 2021 interview with ''The Hollywood Reporter

''The Hollywood Reporter'' (''THR'') is an American digital and print magazine which focuses on the Cinema of the United States, Hollywood film industry, film, television, and entertainment industries. It was founded in 1930 as a daily trade pap ...

'', Columbus revealed that Harris was writing an autobiography during his stay at the hospital, but it has not been published since.

Memorials and legacy

On 30 September 2006, Manuel Di Lucia, of

On 30 September 2006, Manuel Di Lucia, of Kilkee

Kilkee () is a small coastal town in County Clare, Ireland. It is in the parish of Kilkee, formerly Kilfearagh. Kilkee is midway between Kilrush and Doonbeg on the N67 road. The town is popular as a seaside resort. The horseshoe bay is pr ...

, County Clare, a longtime friend, organised the placement in Kilkee of a bronze life-size statue of Richard Harris. It shows Harris at the age of eighteen playing the sport of Racquetball. (He had won the local competition three or four times in a row during the late 1940s.) The sculptor was Seamus Connolly and the work was unveiled by Russell Crowe

Russell Ira Crowe (born 7 April 1964) is an actor. He was born in New Zealand, spent ten years of his childhood in Australia, and moved there permanently at age twenty one. He came to international attention for his role as Roman General Maxi ...

. Harris was an accomplished squash racquets

Squash is a racket-and-ball sport played by two or four players in a four-walled court with a small, hollow, rubber ball. The players alternate in striking the ball with their rackets onto the playable surfaces of the four walls of the court. Th ...

player, winning the Tivoli Cup in Kilkee four years in a row from 1948 to 1951, a record unsurpassed to this day.

Another life-size statue of Richard Harris, as King Arthur from his film ''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'', has been erected in Bedford Row, in the centre of his home town of Limerick. The sculptor of this statue was the Irish sculptor Jim Connolly, a graduate of the Limerick School of Art and Design

The Limerick School of Art and Design (LSAD; ga, Scoil Ealaíne Agus Deartha Luimnigh) is a constituent art college of the Technological University of the Shannon, located in Limerick, Ireland.

The school operates on three of TUS: Midwest's ...

.

At the 2009 BAFTAs, Mickey Rourke dedicated his Best Actor award to Harris, calling him a "good friend and great actor".

In 2013, Rob Gill and Zeb Moore founded the annual Richard Harris International Film Festival.

The Richard Harris Film Festival is one of Ireland's fastest-growing film festivals, growing from just ten films in 2013 to over 115 films in 2017. Each year, one of Harris's sons attends the festival in Limerick.

In 2015, the Limerick Writers' Centre unveiled a commemorative plaque outside Charlie St George's pub on Parnell Street. The pub was a favourite drinking place of Harris on his visits to Limerick. The plaque, celebrating Harris's literary output as part of a Literary Walking Tour of Limerick, was unveiled by his son Jared Harris.

In 1996, Harris was honoured with a commemorative Irish postage stamp for the "Centenary of Irish Cinema", a four-stamp set featuring twelve Irish actors in four Irish films. He was again honoured in ‘Irish Abroad’ stamps in 2020.

Filmography

Film

Television

Theatre

Awards and nominations

Discography

Albums

* ''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'' (Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1967)

* ''A Tramp Shining

''A Tramp Shining'' is the debut album of Richard Harris, released in 1968 by Dunhill Records. The album was written, arranged, and produced by singer-songwriter Jimmy Webb. Although Harris sang several numbers on the soundtrack album to the film ...

'' (1968)

* '' The Yard Went On Forever'' (1968)

* ''The Richard Harris Love Album'' (1970)

* ''My Boy

"My Boy" is a popular song from the early 1970s. The music was composed by Jean-Pierre Bourtayre and Claude François, and the lyrics were translated from the original version "Parce que je t'aime, mon enfant" (Because I Love You My Child) into E ...

'' (1971)

* ''Slides'' (1972)

* ''Tommy

Tommy may refer to:

People

* Tommy (given name)

* Tommy Atkins, or just Tommy, a slang term for a common soldier in the British Army

Arts and entertainment Film and television

* ''Tommy'' (1931 film), a Soviet drama film

* ''Tommy'' (1975 fil ...

'' (1972)

* ''His Greatest Performances'' (1973)

* ''The Prophet'' (1974) (music by Arif Mardin, based on ''The Prophet

A prophet is a person who is believed to speak through divine inspiration.

Prophet or The Prophet may also refer to:

People People referred to as "The Prophet" as a title

* The Prophet (musician) (born 1968), Dutch gabber and hardstyle DJ ...

'' by Kahlil Gibran)

* ''I, in the Membership of My Days'' (1974)

* ''Gulliver Travels'' (1977)

* ''Camelot'' (Original 1982 London Cast recording) (1982)

* ''Mack The Knife'' (Original Soundtrack) (1989)

* ''Little Tramp'' (Musical) (1992)

* ''The Apocalypse'' (The Story of John the Apostle on an Island named Patmos) (2004)

Singles

* "Here in My Heart" (Theme from '' This Sporting Life'')" (1963) * "How to Handle a Woman (from ''Camelot

Camelot is a castle and court associated with the legendary King Arthur. Absent in the early Arthurian material, Camelot first appeared in 12th-century French romances and, since the Lancelot-Grail cycle, eventually came to be described as the ...

'')" (1968)

* "MacArthur Park

MacArthur Park (originally Westlake Park) is a park dating back to the late 19th century in the Westlake, Los Angeles, Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles. In the early 1940s, it was renamed after General Douglas MacArthur, and later designated ...

" (1968)

* " Didn't We?" (1968)

* "The Yard Went On Forever" (1968)

* "The Hive" (1969)

* "One of the Nicer Things" (1969)

* "Fill the World With Love" (1969)

* "Ballad of '' A Man Called Horse''" (1970)

* "Morning of the Mourning for Another Kennedy" (1970)

* "My Boy

"My Boy" is a popular song from the early 1970s. The music was composed by Jean-Pierre Bourtayre and Claude François, and the lyrics were translated from the original version "Parce que je t'aime, mon enfant" (Because I Love You My Child) into E ...

" (1971)

* "Turning Back the Pages" (1972)

* "Half of Every Dream" (1972)

* " Go to the Mirror" (1973)

* "Trilogy (Love, Marriage, Children)" (1974)

* "The Last Castle (Theme from ''Echoes of a Summer

''Echoes of a Summer'' is a 1976 Canadian-American family drama film directed by Don Taylor, based on the play ''Isle of Children'' by Robert L. Joseph, who also adapted the screenplay. It stars Jodie Foster, Richard Harris, Lois Nettleton, Br ...

'')" (1976)

* "Lilliput (Theme from ''Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

'')" (1977)

Soundtracks

* ''Camelot'' (Original 1982 London Cast Recording) (1988) * ''Mack the Knife'' (Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1989) * ''Tommy'' (studio recording) (1990) * ''Camelot'' (Motion Picture Soundtrack) (1993)Compilations

* ''A Tramp Shining'' (1993) * ''The Prophet'' (1995) * ''The Webb Sessions 1968–1969'' (1996) * ''MacArthur Park'' (1997) * ''Slides/My Boy'' (2-CD Set) (2005) * ''My Boy'' (2006) * ''Man of Words Man of Music The Anthology 1968–1974'' (2008)References

Further reading

*External links

* * * *''Richard Harris file at Limerick City Library, Ireland''

at the '' World Socialist Web Site'' {{DEFAULTSORT:Harris, Richard 1930 births 2002 deaths 20th-century Irish male actors 20th-century Irish male singers 21st-century Irish male actors Alumni of the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art Audiobook narrators Best Musical or Comedy Actor Golden Globe (film) winners Cannes Film Festival Award for Best Actor winners Deaths from lymphoma in England Deaths from Hodgkin lymphoma Dunhill Records artists European Film Awards winners (people) Garryowen Football Club players Grammy Award winners Irish emigrants to the United Kingdom Irish film directors Irish male film actors Irish male radio actors Irish male stage actors Irish male television actors Irish rugby union players Knights of Malta Male actors from Limerick (city) People educated at Crescent College Musicians from Limerick (city) Racquets players University of Scranton faculty Rugby union players from Limerick (city) Fellows of the American Physical Society