Quetzalcoatlus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Quetzalcoatlus'' () is a

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is based on fossils discovered in rocks pertaining to the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation in Big Bend National Park,

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is based on fossils discovered in rocks pertaining to the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation in Big Bend National Park,  Lawson announced his discovery in the journal ''

Lawson announced his discovery in the journal '' Prior to the announcement of the discovery, Langston had returned to Big Bend with a group of fossil preparators in February 1973, primarily aiming to excavate bones of the dinosaur '' Alamosaurus''. One of the preparators, a young man named Bill Amaral who went on to be a respected field worker, had been skipping his lunches to conduct additional explorations of the area. He came across some additional fragments of pterosaur bone on a different portion of the ridge, around 50 kilometers away from the original site. Two more new sites quickly followed nearby, producing many fragments which the crew figured could be fit back together, in addition to a complete carpal and intact wing bone. Langston noted in his field notes that none of these bones suggested animals as large as Lawson's original specimen. Further remains came from Amaral's first site in April 1974, after Lawson's site had been exhausted; a long neck vertebra and a pair of jawbones appeared. Associated structures were initially hoped to represent filamentous pycnofibres, but were later confirmed to be conifer needles. Near the end of the 1974 season, Langston stumbled over a much more complete pterosaur skeleton; it consisted of a wing, multiple vertebrae, a femur and multiple other long bones. They lacked time to fully excavate it, leaving it in the ground until the next field season. This area, where many smaller specimens began to emerge, came to be known as Pterodactyl Ridge. Two of the smaller individuals were reported in the first 1975 paper by Lawson, presumed to belong to the same species, though Langston would begin to question the idea they belonged to ''Q. northropi'' by the early 1980s. Excavations continued in 1976, and eight new specimens emerged in 1977; in 1979, despite complications due to losing the field notes form 1977, Langston discovered another new site that would produce an additional ten specimens. Most importantly, a humerus of the smaller animal was finally found, which Langston considered of great importance to understanding ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Several further new localities followed in 1980, but 1981 proved less successful and Langston began to suspect the ridge may have been mostly depleted of pterosaur fossils. There was similarly little success in 1982, and visits during 1983 and 1985 proved to provide the last substantive discoveries of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' fossils. Langston returned in 1989, 1991, 1992, and 1996, but only found isolated bones and fragments. Eventually a handful of additional specimens were discovered by former student Thomas Lehman. A visit to Lawson's initial site during 1991 showed that all traces of excavation had by now eroded away. Langston would visit Big Bend for the last time in 1999, having concluded the pterosaur expeditions to focus on the excavation of two skulls of ''

Prior to the announcement of the discovery, Langston had returned to Big Bend with a group of fossil preparators in February 1973, primarily aiming to excavate bones of the dinosaur '' Alamosaurus''. One of the preparators, a young man named Bill Amaral who went on to be a respected field worker, had been skipping his lunches to conduct additional explorations of the area. He came across some additional fragments of pterosaur bone on a different portion of the ridge, around 50 kilometers away from the original site. Two more new sites quickly followed nearby, producing many fragments which the crew figured could be fit back together, in addition to a complete carpal and intact wing bone. Langston noted in his field notes that none of these bones suggested animals as large as Lawson's original specimen. Further remains came from Amaral's first site in April 1974, after Lawson's site had been exhausted; a long neck vertebra and a pair of jawbones appeared. Associated structures were initially hoped to represent filamentous pycnofibres, but were later confirmed to be conifer needles. Near the end of the 1974 season, Langston stumbled over a much more complete pterosaur skeleton; it consisted of a wing, multiple vertebrae, a femur and multiple other long bones. They lacked time to fully excavate it, leaving it in the ground until the next field season. This area, where many smaller specimens began to emerge, came to be known as Pterodactyl Ridge. Two of the smaller individuals were reported in the first 1975 paper by Lawson, presumed to belong to the same species, though Langston would begin to question the idea they belonged to ''Q. northropi'' by the early 1980s. Excavations continued in 1976, and eight new specimens emerged in 1977; in 1979, despite complications due to losing the field notes form 1977, Langston discovered another new site that would produce an additional ten specimens. Most importantly, a humerus of the smaller animal was finally found, which Langston considered of great importance to understanding ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Several further new localities followed in 1980, but 1981 proved less successful and Langston began to suspect the ridge may have been mostly depleted of pterosaur fossils. There was similarly little success in 1982, and visits during 1983 and 1985 proved to provide the last substantive discoveries of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' fossils. Langston returned in 1989, 1991, 1992, and 1996, but only found isolated bones and fragments. Eventually a handful of additional specimens were discovered by former student Thomas Lehman. A visit to Lawson's initial site during 1991 showed that all traces of excavation had by now eroded away. Langston would visit Big Bend for the last time in 1999, having concluded the pterosaur expeditions to focus on the excavation of two skulls of ''

In 2021, a comprehensive description of the genus was finally published, the 19th entry in the Memoir series of special publications by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in the '' Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology''. It consisted of five studies published together. Kevin Padian was the primary organizer of the project. A paper on the history of discoveries in Big Bend National Park was authored by Matthew J. Brown, Chris Sagebiel, and Brian Andres. It focused on curating a comprehensive list of specimens belonging to each species to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and the locality information of each within Big Bend. Thomas Lehman contributed a study on the paleonvironment that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have resided within, based upon work he had begun with Langston as early as 1993. Brian Andres published a study on the morphology and taxonomy of the genus, established the species ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni'' for the smaller animal that had gone for decades without a name. The specific name honoured Lawson, who discovered ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Despite not contributing directly to the written manuscript, the authors of the memoir and Langston's family agreed that he posthumously be considered a co-author due the basis of the work in the decades of research he dedicates to the subject. Also authored by Andres was a phylogenetic study of ''Quetzacoatlus'' and its relationships within Pterosauria, with a focus on the persistence of many lineages into the

In 2021, a comprehensive description of the genus was finally published, the 19th entry in the Memoir series of special publications by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in the '' Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology''. It consisted of five studies published together. Kevin Padian was the primary organizer of the project. A paper on the history of discoveries in Big Bend National Park was authored by Matthew J. Brown, Chris Sagebiel, and Brian Andres. It focused on curating a comprehensive list of specimens belonging to each species to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and the locality information of each within Big Bend. Thomas Lehman contributed a study on the paleonvironment that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have resided within, based upon work he had begun with Langston as early as 1993. Brian Andres published a study on the morphology and taxonomy of the genus, established the species ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni'' for the smaller animal that had gone for decades without a name. The specific name honoured Lawson, who discovered ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Despite not contributing directly to the written manuscript, the authors of the memoir and Langston's family agreed that he posthumously be considered a co-author due the basis of the work in the decades of research he dedicates to the subject. Also authored by Andres was a phylogenetic study of ''Quetzacoatlus'' and its relationships within Pterosauria, with a focus on the persistence of many lineages into the

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' consists of two valid species: the

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' consists of two valid species: the  Though Lawson originally considered all ''Quetzalcoatlus'' remains to belong to one species, today two species are recognized: the large ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' and the smaller ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni''. The exact nature of what material belongs to each species remains unclear, due in part to the distribution of specimens across various localities and stratigraphic levels found at Big Bend, as well as the limited scope of ''Q. northropi'' material to compare to. The name-bearing

Though Lawson originally considered all ''Quetzalcoatlus'' remains to belong to one species, today two species are recognized: the large ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' and the smaller ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni''. The exact nature of what material belongs to each species remains unclear, due in part to the distribution of specimens across various localities and stratigraphic levels found at Big Bend, as well as the limited scope of ''Q. northropi'' material to compare to. The name-bearing

Though most pterosaur remains from Big Bend have been referred to ''Quetzalcoatlus'', some other material exists. Most prominent amongst these is a specimen discovered around north of the Pterodactyl Ridge localities, designated as TMM 42489-2 and compromising a partial skull and jaws as well as five articulated neck vertebrae. It was immediately noted for its distinct shorted-jawed anatomy compared to what had come to be expected from ''Q. lawsoni'' specimens. Despite this distinctiveness, it was referred to as a separate ''Quetzalcoatlus sp.'' in a 1991 book by Langston. As early as 1996, however, this was revised with recognition it was certainly a new genus informally known as the "short-faced pterosaur". It was formally named in the 2021 paper alongside ''Q. lawsoni'', as the genus '' Wellnhopterus''. In addition to this specimen, several indeterminate azhdarchid remains and some remains too fragmentary to assign beyond Pterosauria are known from Big Bend. Some of these represent smaller animals than the uniformly sized ''Q. lawsoni'' remains. Whether any of these remains represented separate animals from ''Quetzalcoatlus'' cannot be determined.

Several specimens from across Late Cretaceous North America were historically referred to ''Quetzalcoatlus''. In 1982 a femur from the

Though most pterosaur remains from Big Bend have been referred to ''Quetzalcoatlus'', some other material exists. Most prominent amongst these is a specimen discovered around north of the Pterodactyl Ridge localities, designated as TMM 42489-2 and compromising a partial skull and jaws as well as five articulated neck vertebrae. It was immediately noted for its distinct shorted-jawed anatomy compared to what had come to be expected from ''Q. lawsoni'' specimens. Despite this distinctiveness, it was referred to as a separate ''Quetzalcoatlus sp.'' in a 1991 book by Langston. As early as 1996, however, this was revised with recognition it was certainly a new genus informally known as the "short-faced pterosaur". It was formally named in the 2021 paper alongside ''Q. lawsoni'', as the genus '' Wellnhopterus''. In addition to this specimen, several indeterminate azhdarchid remains and some remains too fragmentary to assign beyond Pterosauria are known from Big Bend. Some of these represent smaller animals than the uniformly sized ''Q. lawsoni'' remains. Whether any of these remains represented separate animals from ''Quetzalcoatlus'' cannot be determined.

Several specimens from across Late Cretaceous North America were historically referred to ''Quetzalcoatlus''. In 1982 a femur from the

''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' was among the largest azhdarchids, though was rivalled in size by ''Arambourgiania'' and '' Hatzegopteryx'' (and possibly '' Cryodrakon''). Azhdarchids were split into two primary categories: short-necked taxa with short, robust beaks (i.e. ''Hatzegopteryx'' and ''Wellnhopterus''), and long-necked taxa with longer, slenderer beaks (i.e. '' Zhejiangopterus''). Of these, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' falls squarely into the latter. Based on the limb morphology of ''Q. lawsoni'', related azhdarchids such as ''Zhejiangopterus'', and pterosaurs at large, in addition to azhdarchid tracks from South Korea, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was likely quadrupedal. As a pterosaur, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have been covered in hair-like pycnofibres, and had extensive wing-membranes, which would have been distended by a long wing-finger. There have been various models of the morphology of pterodactyloid wings, though based on multiple well-preserved pterosaur specimens, it is likely that azhdarchids had broad wings, with a brachiopatagium extending down to the ankle. The

''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' was among the largest azhdarchids, though was rivalled in size by ''Arambourgiania'' and '' Hatzegopteryx'' (and possibly '' Cryodrakon''). Azhdarchids were split into two primary categories: short-necked taxa with short, robust beaks (i.e. ''Hatzegopteryx'' and ''Wellnhopterus''), and long-necked taxa with longer, slenderer beaks (i.e. '' Zhejiangopterus''). Of these, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' falls squarely into the latter. Based on the limb morphology of ''Q. lawsoni'', related azhdarchids such as ''Zhejiangopterus'', and pterosaurs at large, in addition to azhdarchid tracks from South Korea, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was likely quadrupedal. As a pterosaur, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have been covered in hair-like pycnofibres, and had extensive wing-membranes, which would have been distended by a long wing-finger. There have been various models of the morphology of pterodactyloid wings, though based on multiple well-preserved pterosaur specimens, it is likely that azhdarchids had broad wings, with a brachiopatagium extending down to the ankle. The

''Quetzalcoatlus'' is regarded as one of the largest pterosaurs, though its exact size has been difficult to determine. In 1975, Douglas Lawson compared the wing bones of ''Q. northropi'' to equivalent elements in '' Dsungaripterus'' and ''

''Quetzalcoatlus'' is regarded as one of the largest pterosaurs, though its exact size has been difficult to determine. In 1975, Douglas Lawson compared the wing bones of ''Q. northropi'' to equivalent elements in '' Dsungaripterus'' and ''

Like other pterosaurs, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' had light, hollow bones, supported internally by struts called trabeculae. The neck of ''Q. lawsoni'', measured from the third cervical (neck)

Like other pterosaurs, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' had light, hollow bones, supported internally by struts called trabeculae. The neck of ''Q. lawsoni'', measured from the third cervical (neck)  ''Quetzalcoatlus''

''Quetzalcoatlus''

When describing ''Quetzalcoatlus'' in 1975, Douglas Lawson and Crawford Greenewalt opted not to assign it to a clade more specific than Pterodactyloidea, though comparisons with '' Arambourgiania'' (then ''Titanopteryx'') from

When describing ''Quetzalcoatlus'' in 1975, Douglas Lawson and Crawford Greenewalt opted not to assign it to a clade more specific than Pterodactyloidea, though comparisons with '' Arambourgiania'' (then ''Titanopteryx'') from

The nature of flight in ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and other giant azhdarchids was poorly understood until serious biomechanical studies were conducted in the 21st century. A 1984 experiment by Paul MacCready used practical aerodynamics to test the flight of ''Quetzalcoatlus''. MacCready constructed a model flying machine or, ornithopter, with a simple computer functioning as an

The nature of flight in ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and other giant azhdarchids was poorly understood until serious biomechanical studies were conducted in the 21st century. A 1984 experiment by Paul MacCready used practical aerodynamics to test the flight of ''Quetzalcoatlus''. MacCready constructed a model flying machine or, ornithopter, with a simple computer functioning as an  Other flight capability estimates have disagreed with Henderson's research, suggesting instead an animal superbly adapted to long-range, extended flight. In 2010, Mike Habib, a professor of biomechanics at Chatham University, and Mark Witton, a British paleontologist, undertook further investigation into the claims of flightlessness in large pterosaurs. After factoring wingspan, body weight, and aerodynamics, computer modeling led the two researchers to conclude that ''Q. northropi'' was capable of flight up to for 7 to 10 days at altitudes of . Habib further suggested a maximum flight range of for ''Q. northropi''. Henderson's work was also further criticized by Witton and Habib in another study, which pointed out that, although Henderson used excellent mass estimations, they were based on outdated pterosaur models, which caused Henderson's mass estimations to be more than double what Habib used in his estimations and that anatomical study of ''Q. northropi'' and other big pterosaur forelimbs showed a higher degree of robustness than would be expected if they were purely quadrupedal. This study proposed that large pterosaurs most likely utilized a short burst of powered flight to then transition to thermal soaring. However, a study from 2022 suggests that they would only have flown occasionally and for short distances, like the Kori bustard (the world's heaviest bird that actively flies) and that they were not able to soar at all. Studies of ''Q. northropi'' and ''Q. lawsoni'' published in 2021 by Kevin Padian et al. instead suggested that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was a very powerful flier. While Padian himself also suggested that the legs and feet were likely tucked under the body during flight as in modern birds, co-authors John Conway and James Cunningham endorsed a system more in line with conventional models of pterosaur flight, wherein the hind limbs were splayed out while the animal was airborne.

Other flight capability estimates have disagreed with Henderson's research, suggesting instead an animal superbly adapted to long-range, extended flight. In 2010, Mike Habib, a professor of biomechanics at Chatham University, and Mark Witton, a British paleontologist, undertook further investigation into the claims of flightlessness in large pterosaurs. After factoring wingspan, body weight, and aerodynamics, computer modeling led the two researchers to conclude that ''Q. northropi'' was capable of flight up to for 7 to 10 days at altitudes of . Habib further suggested a maximum flight range of for ''Q. northropi''. Henderson's work was also further criticized by Witton and Habib in another study, which pointed out that, although Henderson used excellent mass estimations, they were based on outdated pterosaur models, which caused Henderson's mass estimations to be more than double what Habib used in his estimations and that anatomical study of ''Q. northropi'' and other big pterosaur forelimbs showed a higher degree of robustness than would be expected if they were purely quadrupedal. This study proposed that large pterosaurs most likely utilized a short burst of powered flight to then transition to thermal soaring. However, a study from 2022 suggests that they would only have flown occasionally and for short distances, like the Kori bustard (the world's heaviest bird that actively flies) and that they were not able to soar at all. Studies of ''Q. northropi'' and ''Q. lawsoni'' published in 2021 by Kevin Padian et al. instead suggested that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was a very powerful flier. While Padian himself also suggested that the legs and feet were likely tucked under the body during flight as in modern birds, co-authors John Conway and James Cunningham endorsed a system more in line with conventional models of pterosaur flight, wherein the hind limbs were splayed out while the animal was airborne.

Early interpretations of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' launching relied on bipedal models. In 2004, Sankar Chatterjee and R.J. Templin used a model and utilized a running launch cycle powered by the hind limbs, in which ''Q. northropi'' was only barely able to take off. In 2008, Michael Habib suggested that the only feasible takeoff method for a ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was one that was mainly powered by the forelimbs. In 2010, Mark Witton and Habib noted that the femur of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was only a third as strong as what would be expected from a bird of equal size, whereas the humerus is considerably stronger, and affirmed that an azhdarchid the size of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have great difficulty taking off bipedally. Thus, they considered a quadrupedal launching method, with the forelimbs applying most of the necessary force, a likelier method of takeoff. In 2021, Kevin Padian et al. attempted to resurrect the bipedal launch model, using a comparatively light weight estimate of . They suggested that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' hind limbs were more powerful than previously suggested, and that they were strong enough to launch its body as high as off the ground without the aid of the forelimbs. A large breastbone would support the necessary muscles to create a flight stroke, allowing ''Quetzalcoatlus'' to gain enough clearance to begin the downstrokes needed for takeoff. In an blog post written in response to the Padian et al. study, Mark Witton wrote that little of ''Quetzalcoatlus''

Early interpretations of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' launching relied on bipedal models. In 2004, Sankar Chatterjee and R.J. Templin used a model and utilized a running launch cycle powered by the hind limbs, in which ''Q. northropi'' was only barely able to take off. In 2008, Michael Habib suggested that the only feasible takeoff method for a ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was one that was mainly powered by the forelimbs. In 2010, Mark Witton and Habib noted that the femur of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was only a third as strong as what would be expected from a bird of equal size, whereas the humerus is considerably stronger, and affirmed that an azhdarchid the size of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have great difficulty taking off bipedally. Thus, they considered a quadrupedal launching method, with the forelimbs applying most of the necessary force, a likelier method of takeoff. In 2021, Kevin Padian et al. attempted to resurrect the bipedal launch model, using a comparatively light weight estimate of . They suggested that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' hind limbs were more powerful than previously suggested, and that they were strong enough to launch its body as high as off the ground without the aid of the forelimbs. A large breastbone would support the necessary muscles to create a flight stroke, allowing ''Quetzalcoatlus'' to gain enough clearance to begin the downstrokes needed for takeoff. In an blog post written in response to the Padian et al. study, Mark Witton wrote that little of ''Quetzalcoatlus''

Definitive fossils of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' have only been found from the Javelina Formation of Texas, though similar and potentially congeneric azhdarchids are known from isolated bones across North America. The formation consists of around of

Definitive fossils of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' have only been found from the Javelina Formation of Texas, though similar and potentially congeneric azhdarchids are known from isolated bones across North America. The formation consists of around of

In 1975, Douglas Lawson rejected the notion that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' might have had a fish-eating (piscivorous) lifestyle like pteranodontids. The Big Bend site where the holotype was discovered is roughly removed from the coastline, and since Lawson believed that the river systems of the locality were too small to support an animal the size of ''Q. northropi'', he instead suggested that it was a scavenger, similar to vultures. The holotype was found in close association with the skeletons of '' Alamosaurus'', a titanosaur

In 1975, Douglas Lawson rejected the notion that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' might have had a fish-eating (piscivorous) lifestyle like pteranodontids. The Big Bend site where the holotype was discovered is roughly removed from the coastline, and since Lawson believed that the river systems of the locality were too small to support an animal the size of ''Q. northropi'', he instead suggested that it was a scavenger, similar to vultures. The holotype was found in close association with the skeletons of '' Alamosaurus'', a titanosaur  The predominant model of azhdarchid feeding behavior is the "terrestrial stalking" hypothesis, which suggests that they fed upon small terrestrial prey. A predecessor to this hypothesis was proposed by

The predominant model of azhdarchid feeding behavior is the "terrestrial stalking" hypothesis, which suggests that they fed upon small terrestrial prey. A predecessor to this hypothesis was proposed by

''Quetzalcoatlus''

at EarthArchives.org * * * * {{Portal bar, Paleontology, United States Azhdarchidae Late Cretaceous pterosaurs of North America Ojo Alamo Formation Maastrichtian genus extinctions Taxa named by Douglas A. Lawson Fossil taxa described in 1975 Quetzalcoatl

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of azhdarchid pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

that lived during the Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian ( ) is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age (uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage) of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or Upper Cretaceous series (s ...

age of the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

in North America. The type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

, recovered in 1971 from the Javelina Formation of Texas, United States, consists of several wing fragments and was described as ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' in 1975 by Douglas Lawson. The first part of the name refers to the Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

serpent god of the sky, Quetzalcōātl, while the second part honors Jack Northrop, designer of a tailless fixed-wing aircraft. The remains of a second species were found between 1972 and 1974, also by Lawson, around from the ''Q. northropi'' locality. In 2021, these remains were assigned to the name ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni'' by Brian Andres and (posthumously) Wann Langston Jr, as part of a series of publications on the genus.

''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' has gained fame as a candidate for the largest flying animal ever discovered, though estimating its size has been difficult due to the fragmentary nature of the only known specimen. While wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the opposite wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingsp ...

estimates over the years have ranged from , more recent estimates hover around . The smaller and more complete ''Q. lawsoni'' had a wingspan of around . Unlike most azhdarchids, ''Q. lawsoni'' had a small head crest, an extension of the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

. Two different forms have been identified: one had a rectangular head crest and a taller nasoantorbital fenestra (a structure combining the naris and antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with Archosauriformes, archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among Extant ...

in many pterosaurs), and the other had a more rounded head crest and a shorter nasoantorbital fenestra. The proportions of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' behind the skull were typical of azhdarchids, with a very long neck and beak, shortened non-wing digits that were well adapted for walking

Walking (also known as ambulation) is one of the main gaits of terrestrial locomotion among legged animals. Walking is typically slower than running and other gaits. Walking is defined as an " inverted pendulum" gait in which the body vaults o ...

, and a very short tail.

Historical interpretations of the diet of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' have ranged from scavenging to skim-feeding like the modern skimmer bird. However, more recent research has found that it most likely hunted small prey on the ground, in a similar way to stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons and ibise ...

s and ground hornbills. This has been dubbed the terrestrial stalking hypothesis and is thought to be a common feeding behavior among large azhdarchids. On the other hand, the second species, ''Q. lawsoni'', appears to have been associated with alkaline lakes, and a diet of small aquatic invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s has been suggested. Similarly, while ''Q. northropi'' is speculated to have been fairly solitary, ''Q. lawsoni'' appears to have been highly gregarious (social). Azhdarchids like ''Quetzalcoatlus'' were highly terrestrial by pterosaur standards, though even the largest were nonetheless capable of flight. Based on the work of Mark P. Witton and Michael Habib in 2010, it now seems likely that pterosaurs, especially larger taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

such as ''Quetzalcoatlus'', launched quadrupedally (from a four-legged posture), using the powerful muscles of their forelimbs to propel themselves off the ground and into the air.

Research history and taxonomy

Discovery and naming

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is based on fossils discovered in rocks pertaining to the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation in Big Bend National Park,

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' is based on fossils discovered in rocks pertaining to the Late Cretaceous Javelina Formation in Big Bend National Park, Texas

Texas ( , ; or ) is the most populous U.S. state, state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. It borders Louisiana to the east, Arkansas to the northeast, Oklahoma to the north, New Mexico to the we ...

. Remains of dinosaurs and other prehistoric life had been found in the area since the beginning of the 20th century. The first ''Quetzalcoatlus'' fossils were discovered in 1971 by the graduate student Douglas A. Lawson while conducting field work for his Master's degree

A master's degree (from Latin ) is a postgraduate academic degree awarded by universities or colleges upon completion of a course of study demonstrating mastery or a high-order overview of a specific field of study or area of professional prac ...

project on the paleoecology

Paleoecology (also spelled palaeoecology) is the study of interactions between organisms and/or interactions between organisms and their environments across geologic timescales. As a discipline, paleoecology interacts with, depends on and informs ...

of the Javelina Formation. This field work was supervised by Wann Langston Jr., an experienced paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

who had been doing field work in the region since 1938 and since 1963 led expeditions through his position as curator

A curator (from , meaning 'to take care') is a manager or overseer. When working with cultural organizations, a curator is typically a "collections curator" or an "exhibitions curator", and has multifaceted tasks dependent on the particular ins ...

at the Texas Science and Natural History Museum. The two had first visited the park together in March 1970, with Lawson discovering the first ''Tyrannosaurus rex'' fossil from Texas. Returning in 1971, Lawson discovered a bone while investigating an arroyo on the western edge of the park, and returned to Austin with a section of it. He and Langston then identified it as a pterosaur

Pterosaurs are an extinct clade of flying reptiles in the order Pterosauria. They existed during most of the Mesozoic: from the Late Triassic to the end of the Cretaceous (228 million to 66 million years ago). Pterosaurs are the earli ...

fossil based on its hollow internal structure with thin walls. Returning in November 1971 for further excavations, they were struck by the unprecedented size of the remains compared to known pterosaurs. The initial material consisted of a giant radius and ulna, two fused wristbones known as syncarpals, and the end of the wing finger. Altogether, the material comprised a partial left wing from an individual (specimen number TMM 41450-3) later estimated at over in wingspan

The wingspan (or just span) of a bird or an airplane is the distance from one wingtip to the opposite wingtip. For example, the Boeing 777–200 has a wingspan of , and a wandering albatross (''Diomedea exulans'') caught in 1965 had a wingsp ...

. Lawson described the remains in his 1972 thesis as "Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (; from and ) is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of over . They lived during the late Cretaceous geological period of North America in presen ...

gigas", and diagnosed it as being "nearly twice as large as any previously described species of ''Pteranodon''". As a thesis is not recognized as a published worked by the International Code for Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), "Pteranodon gigas" is not a valid name. Further field work at the site was conducted in March 1973, when fragments were found alongside a long and delicate bone connected to an apparently larger element. This fossil was left in the ground until April 1974, when they fully excavated the larger element, a humerus. Due to the close association of discovered remains, Langston felt confident there were nothing more to be found at the site. Several later excavations of the site have indeed been unsuccessful.

Lawson announced his discovery in the journal ''

Lawson announced his discovery in the journal ''Science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

'' in March 1975, with a depiction of the animal's size compared to a large aircraft and a ''Pteranodon'' gracing the cover of the issue. Lawson wrote that it was "without doubt the largest flying animal presently known". He illustrated and briefly described the remains known at the time, but did not offer a name and indicated that a more extensive description was in preparation that would diagnose the species. In May, he submitted a short response to his original paper to the journal, considering how such an enormous animal could have flown. Within the paper, he briefly established the name ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'', but did still not provide a diagnosis or a more detailed description, which would later cause nomenclatural problems. Though not specified in the original publication, Lawson's named the genus after the Aztec

The Aztecs ( ) were a Mesoamerican civilization that flourished in central Mexico in the Post-Classic stage, post-classic period from 1300 to 1521. The Aztec people included different Indigenous peoples of Mexico, ethnic groups of central ...

feathered serpent god Quetzalcōātl, while the specific name honors John Knudsen Northrop, the founder of Northrop Corporation

Northrop Corporation was an American aircraft manufacturer from its formation in 1939 until its 1994 merger with Grumman to form Northrop Grumman. The company is known for its development of the flying wing design, most successfully the B-2 Spiri ...

, who drove the development of large tailless Northrop YB-49 aircraft designs resembling ''Quetzalcoatlus''. The discovery of the giant pterosaur left a strong impression on both the scientific community and the general public, and was reported on throughout the world. It was featured in Time Magazine

''Time'' (stylized in all caps as ''TIME'') is an American news magazine based in New York City. It was published weekly for nearly a century. Starting in March 2020, it transitioned to every other week. It was first published in New York Cit ...

and appeared on the cover of Scientific American

''Scientific American'', informally abbreviated ''SciAm'' or sometimes ''SA'', is an American popular science magazine. Many scientists, including Albert Einstein and Nikola Tesla, have contributed articles to it, with more than 150 Nobel Pri ...

in 1981 alongside an article on pterosaurs by Langston. The species would become referenced by over 500 scientific publications, with ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' becoming the single most cited pterosaur species and ''Quetzalcoatlus'' the fourth most cited pterosaur genus after ''Pteranodon'', '' Rhamphorhynchus'', and '' Pterodactylus'', much older genera with many more species than ''Quetzalcoatlus''.

Prior to the announcement of the discovery, Langston had returned to Big Bend with a group of fossil preparators in February 1973, primarily aiming to excavate bones of the dinosaur '' Alamosaurus''. One of the preparators, a young man named Bill Amaral who went on to be a respected field worker, had been skipping his lunches to conduct additional explorations of the area. He came across some additional fragments of pterosaur bone on a different portion of the ridge, around 50 kilometers away from the original site. Two more new sites quickly followed nearby, producing many fragments which the crew figured could be fit back together, in addition to a complete carpal and intact wing bone. Langston noted in his field notes that none of these bones suggested animals as large as Lawson's original specimen. Further remains came from Amaral's first site in April 1974, after Lawson's site had been exhausted; a long neck vertebra and a pair of jawbones appeared. Associated structures were initially hoped to represent filamentous pycnofibres, but were later confirmed to be conifer needles. Near the end of the 1974 season, Langston stumbled over a much more complete pterosaur skeleton; it consisted of a wing, multiple vertebrae, a femur and multiple other long bones. They lacked time to fully excavate it, leaving it in the ground until the next field season. This area, where many smaller specimens began to emerge, came to be known as Pterodactyl Ridge. Two of the smaller individuals were reported in the first 1975 paper by Lawson, presumed to belong to the same species, though Langston would begin to question the idea they belonged to ''Q. northropi'' by the early 1980s. Excavations continued in 1976, and eight new specimens emerged in 1977; in 1979, despite complications due to losing the field notes form 1977, Langston discovered another new site that would produce an additional ten specimens. Most importantly, a humerus of the smaller animal was finally found, which Langston considered of great importance to understanding ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Several further new localities followed in 1980, but 1981 proved less successful and Langston began to suspect the ridge may have been mostly depleted of pterosaur fossils. There was similarly little success in 1982, and visits during 1983 and 1985 proved to provide the last substantive discoveries of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' fossils. Langston returned in 1989, 1991, 1992, and 1996, but only found isolated bones and fragments. Eventually a handful of additional specimens were discovered by former student Thomas Lehman. A visit to Lawson's initial site during 1991 showed that all traces of excavation had by now eroded away. Langston would visit Big Bend for the last time in 1999, having concluded the pterosaur expeditions to focus on the excavation of two skulls of ''

Prior to the announcement of the discovery, Langston had returned to Big Bend with a group of fossil preparators in February 1973, primarily aiming to excavate bones of the dinosaur '' Alamosaurus''. One of the preparators, a young man named Bill Amaral who went on to be a respected field worker, had been skipping his lunches to conduct additional explorations of the area. He came across some additional fragments of pterosaur bone on a different portion of the ridge, around 50 kilometers away from the original site. Two more new sites quickly followed nearby, producing many fragments which the crew figured could be fit back together, in addition to a complete carpal and intact wing bone. Langston noted in his field notes that none of these bones suggested animals as large as Lawson's original specimen. Further remains came from Amaral's first site in April 1974, after Lawson's site had been exhausted; a long neck vertebra and a pair of jawbones appeared. Associated structures were initially hoped to represent filamentous pycnofibres, but were later confirmed to be conifer needles. Near the end of the 1974 season, Langston stumbled over a much more complete pterosaur skeleton; it consisted of a wing, multiple vertebrae, a femur and multiple other long bones. They lacked time to fully excavate it, leaving it in the ground until the next field season. This area, where many smaller specimens began to emerge, came to be known as Pterodactyl Ridge. Two of the smaller individuals were reported in the first 1975 paper by Lawson, presumed to belong to the same species, though Langston would begin to question the idea they belonged to ''Q. northropi'' by the early 1980s. Excavations continued in 1976, and eight new specimens emerged in 1977; in 1979, despite complications due to losing the field notes form 1977, Langston discovered another new site that would produce an additional ten specimens. Most importantly, a humerus of the smaller animal was finally found, which Langston considered of great importance to understanding ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Several further new localities followed in 1980, but 1981 proved less successful and Langston began to suspect the ridge may have been mostly depleted of pterosaur fossils. There was similarly little success in 1982, and visits during 1983 and 1985 proved to provide the last substantive discoveries of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' fossils. Langston returned in 1989, 1991, 1992, and 1996, but only found isolated bones and fragments. Eventually a handful of additional specimens were discovered by former student Thomas Lehman. A visit to Lawson's initial site during 1991 showed that all traces of excavation had by now eroded away. Langston would visit Big Bend for the last time in 1999, having concluded the pterosaur expeditions to focus on the excavation of two skulls of ''Deinosuchus

''Deinosuchus'' is an extinct genus of eusuchian, either an Alligatoroidea, alligatoroid Crocodilia, crocodilian or a stem-group crocodilian, which lived during the Late Cretaceous around . The first remains were discovered in North Carolina ...

'', another famous fossil of the area.

Later research

The expected further description implicated by Lawson never came. For the next 50 years, the material would remain under incomplete study, and few concrete anatomical details were documented within the literature. Much confusion surrounded the smaller individuals from Pterodactyl Ridge. In a 1981 article on pterosaurs, Langston expressed reservations whether they were truly the same species as the immense ''Q. northropi''. In the meantime, Langston focused on the animal's publicity. He worked on a life-sized gliding replica of ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' with aeronautical engineer Paul MacCready between 1981 and 1985, promoting it in a dedicated IMAX film. The model was created to understand the flight of the animal — prior to Lawson's discovery such a large flier wasn't thought possible, and the subject remained controversial at the time. Furthermore, the model was intended to allow people to experience the animal in a more dynamic manner than a mere static display or film. Around this time he also created a skeletal mount of the genus that was exhibited at the Texas Memorial Museum. The next scientific effort of note was a 1996 paper by Langston and pterosaur specialist Alexander Kellner. By this time, Langston was confident the smaller animals were a separate species. A full publication establishing such a species was still in preparation at the time, but due to the importance of the skull material for the understanding of azhdarchid anatomy, the skull anatomy was published first. In this publication, he animal was referred to as ''Quetzalcoatlus'' sp., a placeholder designation for material not assigned to any particularly valid species. Once again, the planned further publication failed to materialize for decades, and ''Quetzalcoatlus'' sp. remained in limbo. A publication on the bioaeromechanics of the genus was also planned by Langston and James Cunningham, but this failed to materialize and the partially completed manuscript later became lost. Ultimately, a comprehensive publication on ''Quetzalcoatlus'' sp. would not appear before Langston's death in 2013. By this point he had produced many notes and individual descriptions, but had not begun writing any formal manuscript that could be published. In 2021, a comprehensive description of the genus was finally published, the 19th entry in the Memoir series of special publications by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in the '' Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology''. It consisted of five studies published together. Kevin Padian was the primary organizer of the project. A paper on the history of discoveries in Big Bend National Park was authored by Matthew J. Brown, Chris Sagebiel, and Brian Andres. It focused on curating a comprehensive list of specimens belonging to each species to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and the locality information of each within Big Bend. Thomas Lehman contributed a study on the paleonvironment that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have resided within, based upon work he had begun with Langston as early as 1993. Brian Andres published a study on the morphology and taxonomy of the genus, established the species ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni'' for the smaller animal that had gone for decades without a name. The specific name honoured Lawson, who discovered ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Despite not contributing directly to the written manuscript, the authors of the memoir and Langston's family agreed that he posthumously be considered a co-author due the basis of the work in the decades of research he dedicates to the subject. Also authored by Andres was a phylogenetic study of ''Quetzacoatlus'' and its relationships within Pterosauria, with a focus on the persistence of many lineages into the

In 2021, a comprehensive description of the genus was finally published, the 19th entry in the Memoir series of special publications by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in the '' Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology''. It consisted of five studies published together. Kevin Padian was the primary organizer of the project. A paper on the history of discoveries in Big Bend National Park was authored by Matthew J. Brown, Chris Sagebiel, and Brian Andres. It focused on curating a comprehensive list of specimens belonging to each species to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and the locality information of each within Big Bend. Thomas Lehman contributed a study on the paleonvironment that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have resided within, based upon work he had begun with Langston as early as 1993. Brian Andres published a study on the morphology and taxonomy of the genus, established the species ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni'' for the smaller animal that had gone for decades without a name. The specific name honoured Lawson, who discovered ''Quetzalcoatlus''. Despite not contributing directly to the written manuscript, the authors of the memoir and Langston's family agreed that he posthumously be considered a co-author due the basis of the work in the decades of research he dedicates to the subject. Also authored by Andres was a phylogenetic study of ''Quetzacoatlus'' and its relationships within Pterosauria, with a focus on the persistence of many lineages into the Late Cretaceous

The Late Cretaceous (100.5–66 Ma) is the more recent of two epochs into which the Cretaceous Period is divided in the geologic time scale. Rock strata from this epoch form the Upper Cretaceous Series. The Cretaceous is named after ''cre ...

contra classical interpretations of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' as the last of a dying lineage. Finally, a study on the functional morphology of the genus was authored by Padian, James Cunningham, and John Conway (who contributed scientific illustrations and cover art to the Memoir), with Langston once again considered a posthumous co-author due to his foundational work on the subject. Brown and Padian prefaced the Memoir, who once again emphasized their gratitude to Langston for his decades of work on the animal leading up to the publication.

Taxonomy and material

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' consists of two valid species: the

The genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' consists of two valid species: the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

''Q. northropi'' and the second species ''Q. lawsoni''. Though the name was introduced in 1975, the lack of a formal description complicated its validity for several decades. The oldest name for the species is "''Pteranodon'' gigas", from Lawson's 1973 thesis. However, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted Convention (norm), convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific name, scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the I ...

(ICZN) does not consider a thesis to be a formal publication capable of establishing of a taxon, and the name has not been used since. Regarding the genus ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and species ''Q. northropi'', the name being established in a separate publication than the anatomical diagnosis also failed ICZN standards. As such, it was argued that the name was a ''nomen nudum

In Taxonomy (biology), taxonomy, a ''nomen nudum'' ('naked name'; plural ''nomina nuda'') is a designation which looks exactly like a scientific name of an organism, and may have originally been intended to be one, but it has not been published ...

'', an intended but invalid scientific name, though some authors argued the second publication referencing the initial description was sufficient. The species received a diagnosis in a 1991 paper by Lev Nessov, but no action was taken to formalize the name. Furthermore, a study by Mark Witton and colleagues in 2010 doubted whether ''Quetzalcoatlus'' could be validly diagnosed at all. They noted that the bones preserved in the holotype of ''Q. northropi'' were not typically considered to be taxonomically informative between close relatives, and that they appeared extremely similar to those of other giant azhdarchids such as the Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

n azhdarchid '' Hatzegopteryx''. Both of these issues were settled in the 2021 paper, whose rediagnosis affirmed ''Quetzalcoatlus'' as distinct. The authors agreed that the original paper did not constitute a valid establishment of the name. The authors noted their publication could serve as the a basis for the name, but did not wish to change the previously presumed authorship of the name. Thus, they submitted an application for the ICZN in 2017 to make an exception to the requirements, and had Lawson's second 1975 paper to be declared as the valid authority of the genus and species. The approval of this ICZN petition on August 30, 2019, conserved and formalized the binomen ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' as the type species.

Though Lawson originally considered all ''Quetzalcoatlus'' remains to belong to one species, today two species are recognized: the large ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' and the smaller ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni''. The exact nature of what material belongs to each species remains unclear, due in part to the distribution of specimens across various localities and stratigraphic levels found at Big Bend, as well as the limited scope of ''Q. northropi'' material to compare to. The name-bearing

Though Lawson originally considered all ''Quetzalcoatlus'' remains to belong to one species, today two species are recognized: the large ''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' and the smaller ''Quetzalcoatlus lawsoni''. The exact nature of what material belongs to each species remains unclear, due in part to the distribution of specimens across various localities and stratigraphic levels found at Big Bend, as well as the limited scope of ''Q. northropi'' material to compare to. The name-bearing type specimen

In biology, a type is a particular wikt:en:specimen, specimen (or in some cases a group of specimens) of an organism to which the scientific name of that organism is formally associated. In other words, a type is an example that serves to ancho ...

of ''Q. northropi'' is TMM 41450-3, a partial wing. It includes a humerus, radius, ulna, wrist bones, finger bones, and many elements of the elongate wing finger, in addition to thousands of unidentifiable fragments. It is from the uppermost rocks of the Javelina Formation, making it one of the youngest pterosaur specimens known. Only a single other specimen can confidently be referred to the same species, a left ulna designated TMM 44036-1 known from the Black Peaks Formation, around three quarters the size of the type specimen and sharing distinctive anatomy. Four other specimens share a similarly giant size, but cannot be definitively assigned to ''Q. northropi'' in lack of overlapping material or distinguishing anatomical regions. TMM 41047-1 and TMM 41398-3, are both partial femurs, the former twice the size of that seen in ''Q. lawsoni''. Their anatomy indicates they belonged to the same species, and is distinct from that of ''Q. lawsoni''. Part of a wing finger, TMM 41398-4, is also of the correct size to belong to ''Q. northropi'' but does not preserve the essential anatomy to confirm its identity. This specimen and the smaller femur were the first two specimens Lawson discovered, prior to uncovering the type specimen. Finally, one of the oldest pterosaur specimens in Big Bend is a giant cervical vertebra not matching that of smaller species from the formation. Whilst conventional pterosaur research would assign all of these to ''Q. northropi'', the 2021 redescription preferred to be cautious and merely assigned them to ''Q. cf. northropi'', indicating uncertainty.

The assignment of remains to ''Q. lawsoni'' has proved more simplistic; a large quantity of similar remains were found together in nearby sites, 50 km from the ''Q. northropi'' locality. In total, 305 different fossil elements from 214 specimens are known, all of which are considered consistent with assignment to the same species. This is the most amount of remains referred to any singular species of pterosaur. The vast majority of the dozens of specimens are disarticulated individual bones. A few individual animals are, however, represented by associated remains; identification of these individuals was complicated by each bone being catalogued under a separate number, which was revised as part of the 2021 study. The most complete specimen is TMM 41961-1, which possesses the most complete skull as well as several neck vertebrae, much of both wings, femurs, tibiotarsi, two metatarsals, and one of the toe bones. It was one of the original specimens described by Langston in 1975, and in accordance with Langston's wishes and its completeness was designated as the type specimen. Two less complete specimens, TMM 42180-14 and TMM 42161-1, were also preserved in partial articulation, the former mostly composed of limb and neck bones whilst the latter consists of neck and skull bones. Beyond this, identification of individual specimens is difficult. Two other specimens are more loosely associated, and others may have belonged to a single individual but are too weathered to identify with confidence. In some cases two or three neck vertebrae were found in presumed association, and similar loose associations of one or two limbs bones are seen in several cases. Taken together, nearly the entirely skeleton is represented, with the exception of some of the back of the skull. Eight different specimens preserve various portions of the skull, together allowing for a rather complete picture (excepting a portion of the back of the skull), and similarly the entire mandible is represented when cross-referencing four specimens. All nine neck vertebrae are known, and most torso vertebrae are known through the preservation of the notarium and synsacrum, structures consisting of several fused vertebrae in ornithocheiroid pterosaurs; it is unknown how many unfused vertebrae may have existed between these structures. Every single bone in the arm is known from at least one complete specimen, and the hindlimbs and pelvis are also more or less all present, though the femur and pelvis suffer from poor preservation.

Other referred and reclassified material

Campanian

The Campanian is the fifth of six ages of the Late Cretaceous epoch on the geologic timescale of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). In chronostratigraphy, it is the fifth of six stages in the Upper Cretaceous Series. Campa ...

aged Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta

Alberta is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province in Canada. It is a part of Western Canada and is one of the three Canadian Prairies, prairie provinces. Alberta is bordered by British Columbia to its west, Saskatchewan to its east, t ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

was referred to the genus by Philip J. Currie and Dale Russell. Currie later described further remains from Dinosaur Park in a 2005 book, noting their morphological similarity to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' but expressing caution against referral to the genus. In 2019, however, all azhdarchid remains from the formation were revised as distinct from ''Quetzalcoatlus'' and named as the new genus '' Cryodrakon''. A humerus from the Two Medicine Formation in Montana

Montana ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota to the east, South Dakota to the southeast, Wyoming to the south, an ...

was also provisionally referred to the genus; it was considered an indeterminate azhdarchid or a specimen of '' Montanazhdarcho'' by subsequent studies. A neck vertebra from the Hell Creek Formation, also from Montana but dating to the Maastrichtian

The Maastrichtian ( ) is, in the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) geologic timescale, the latest age (geology), age (uppermost stage (stratigraphy), stage) of the Late Cretaceous epoch (geology), Epoch or Upper Cretaceous series (s ...

, was discovered in 2002 and initially referred in 2006 to ''Quetzalcoatlus''. The 2021 paper merely considered it an azhdarchiform specimen of uncertain affinities, but the 2025 study named it as the holotype of a distinct genus '' Infernodrakon''.

Another neck vertebra, discovered in the similarly aged Lance Formation in Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States, Western United States. It borders Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho t ...

and first described in 1964, was later referred to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' by Brent H. Breithaupt in 1982; later studies referred it to '' Azhdarcho'' or as an indeterminate azhdarchid or azhdarchiform. The 2025 ''Infernodrakon'' study found it to be distinguishable from taxon, but anatomically compatible with ''Q. lawsoni''; when tested in a phylogenetic analysis, they found it to form a polytomy with ''Q. lawsoni'', ''Q. northropi'', and a Moroccan specimen. Therefore, they considered it plausible it belonged to a small ''Q. lawsoni'' individually, but decided to merely make a tentative referral to ''Quetzalcoatlus'' at the genus level due to the incomplete nature of the specimen. The Moroccan specimen, from the Ouled Abdoun Basin (Maastrichtian), is designated as FSAC-OB 14 and was referred to aff. ''Quetzalcoatlus'' by a 2018 study. This indicates it is considered unlikely to belong to the genus but bears extreme anatomical similarity to it.

Description

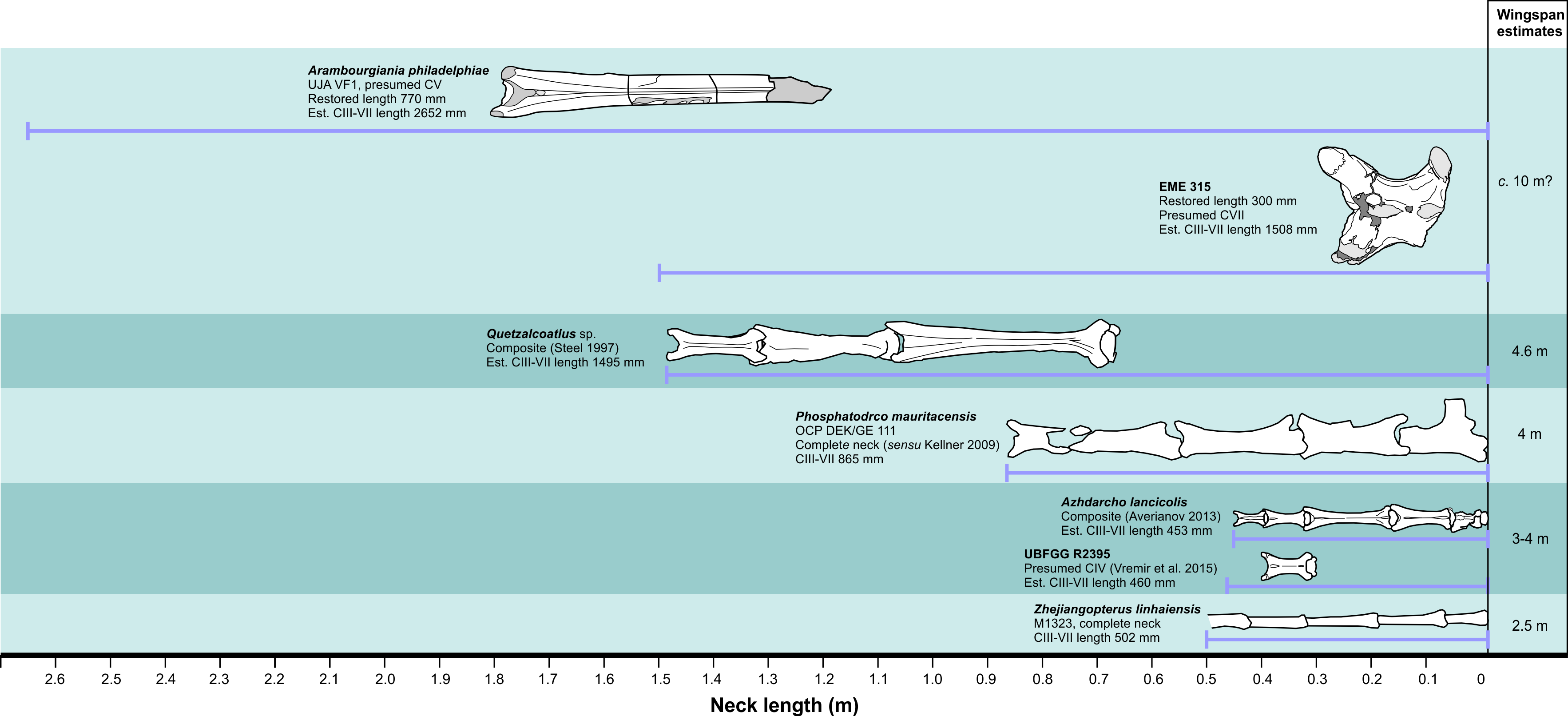

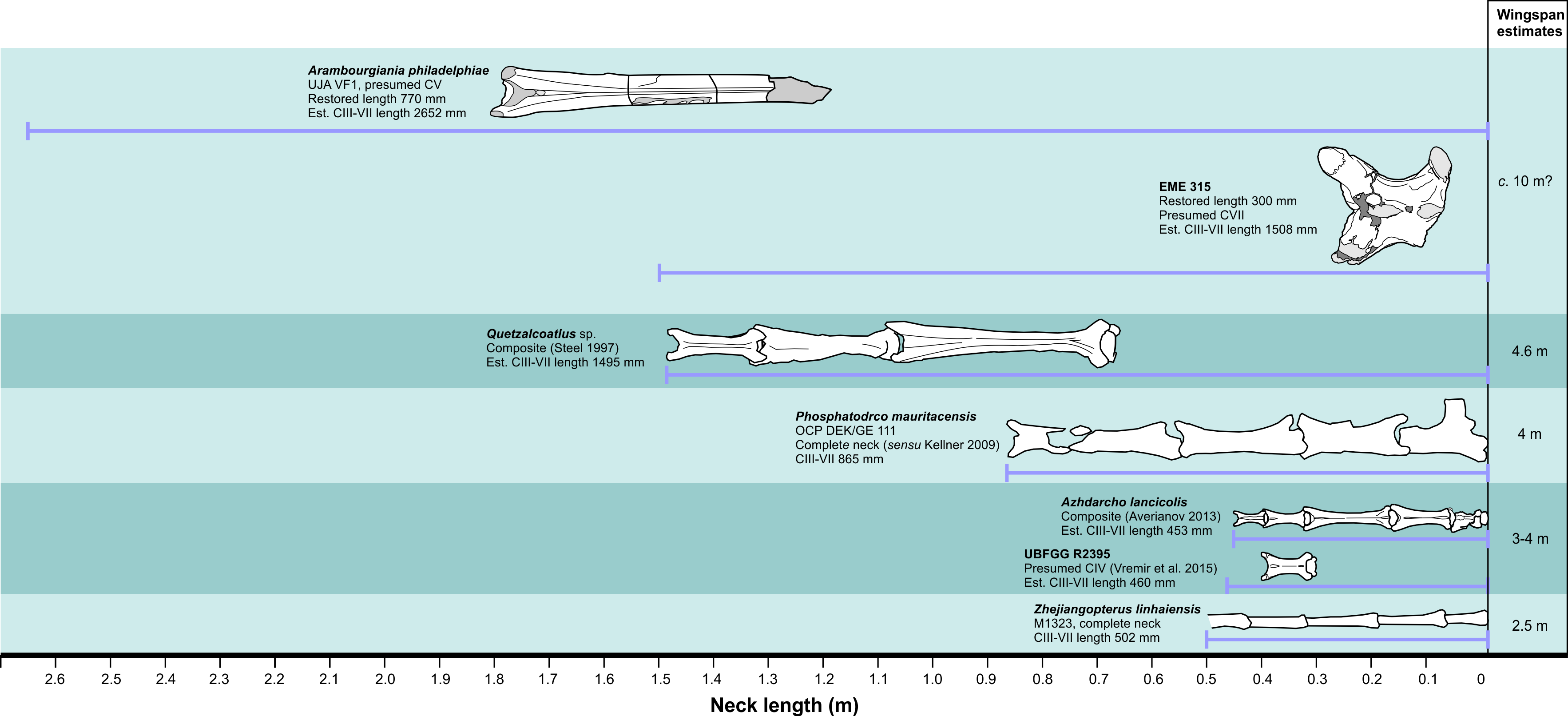

''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' was among the largest azhdarchids, though was rivalled in size by ''Arambourgiania'' and '' Hatzegopteryx'' (and possibly '' Cryodrakon''). Azhdarchids were split into two primary categories: short-necked taxa with short, robust beaks (i.e. ''Hatzegopteryx'' and ''Wellnhopterus''), and long-necked taxa with longer, slenderer beaks (i.e. '' Zhejiangopterus''). Of these, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' falls squarely into the latter. Based on the limb morphology of ''Q. lawsoni'', related azhdarchids such as ''Zhejiangopterus'', and pterosaurs at large, in addition to azhdarchid tracks from South Korea, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was likely quadrupedal. As a pterosaur, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have been covered in hair-like pycnofibres, and had extensive wing-membranes, which would have been distended by a long wing-finger. There have been various models of the morphology of pterodactyloid wings, though based on multiple well-preserved pterosaur specimens, it is likely that azhdarchids had broad wings, with a brachiopatagium extending down to the ankle. The

''Quetzalcoatlus northropi'' was among the largest azhdarchids, though was rivalled in size by ''Arambourgiania'' and '' Hatzegopteryx'' (and possibly '' Cryodrakon''). Azhdarchids were split into two primary categories: short-necked taxa with short, robust beaks (i.e. ''Hatzegopteryx'' and ''Wellnhopterus''), and long-necked taxa with longer, slenderer beaks (i.e. '' Zhejiangopterus''). Of these, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' falls squarely into the latter. Based on the limb morphology of ''Q. lawsoni'', related azhdarchids such as ''Zhejiangopterus'', and pterosaurs at large, in addition to azhdarchid tracks from South Korea, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' was likely quadrupedal. As a pterosaur, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' would have been covered in hair-like pycnofibres, and had extensive wing-membranes, which would have been distended by a long wing-finger. There have been various models of the morphology of pterodactyloid wings, though based on multiple well-preserved pterosaur specimens, it is likely that azhdarchids had broad wings, with a brachiopatagium extending down to the ankle. The aspect ratio

The aspect ratio of a geometry, geometric shape is the ratio of its sizes in different dimensions. For example, the aspect ratio of a rectangle is the ratio of its longer side to its shorter side—the ratio of width to height, when the rectangl ...

of azhdarchid wings is 8.1, similar to that of stork

Storks are large, long-legged, long-necked wading birds with long, stout bills. They belong to the family Ciconiidae, and make up the order Ciconiiformes . Ciconiiformes previously included a number of other families, such as herons and ibise ...

s and birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as (although not the same as) raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively predation, hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and smaller birds). In addition to speed ...

that engage in static soaring (relying on air current

In meteorology, air currents are concentrated areas of winds. They are mainly due to differences in atmospheric pressure or temperature. They are divided into horizontal and vertical currents; both are present at Mesoscale meteorology, mesoscale w ...

s to gain altitude and remain aloft).

Size

Pteranodon

''Pteranodon'' (; from and ) is a genus of pterosaur that included some of the largest known flying reptiles, with ''P. longiceps'' having a wingspan of over . They lived during the late Cretaceous geological period of North America in presen ...

'' and suggested that it represented an individual with a wingspan of around , or, alternatively, or . Estimates put forward in subsequent years varied dramatically, ranging from , owing to differences in methodology. Among the supporters of the initial size estimates was Robert T. Bakker, who, in his 1988 book '' The Dinosaur Heresies'', contended that ''Quetzalcoatlus'' may indeed have reached the upper estimates, and that it may have remained flighted by altering its method of flapping. Other estimates contemporary to Bakker's, however, consistently supported a smaller size of . More recent estimates based on greater knowledge of azhdarchid proportions place its wingspan at . This would approach the maximum size possible for azhdarchids, estimated at ; while higher wingspans may technically be possible, they would require significant morphological changes, and the animal would struggle to become airborne due to increased strain on its joints and long bone

The long bones are those that are longer than they are wide. They are one of five types of bones: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones, especially the femur and tibia, are subjected to most of the load during daily activities ...

s. In one paper from the 2021 Memoir which redescribed ''Quetzalcoatlus'', ''Q. lawsoni'' was estimated to have a wingspan of around . In 2022, Gregory S. Paul

Gregory Scott Paul (born December 24, 1954) is an American freelance researcher, author and illustrator who works in paleontology. He is best known for his work and research on theropoda, theropod dinosaurs and his detailed illustrations, both l ...

suggested that it had a somewhat larger wingspan of around and a body length, from beak to tail, of . Large azhdarchids such as ''Q. northropi'' have been estimated to have a shoulder height of about , and the head may have been held at a similar height to that of an extant giraffe.

Body mass estimates for ''Quetzalcoatlus'' have, similarly, been historically variable. Mass estimates for giant azhdarchids are problematic because no existing species shares a similar size or body plan, and in consequence, published results vary widely. Crawford Greenewalt gave mass estimates of between for ''Q. northropi'', with the former figure assuming a small wingspan of , and the latter assuming a far larger wingspan of . In 2010, Donald M. Henderson recovered the body mass of ''Quetzalcoatlus'' at , twice that of other contemporary estimates, citing it as evidence for secondary flightlessness in the genus. However, the vast majority of estimates published since the 2000s have hovered around , due largely to a greater understanding of how aberrant the anatomy of azhdarchids was in comparison to other pterosaur clades. In 2021, Kevin Padian and colleagues estimated that ''Q. northropi'' would have weighed around , and that ''Q. lawsoni'' would have weighed , while a year later, Gregory S. Paul estimated a body mass of for the latter species.

Skull

Complete skulls are not known from either ''Quetzalcoatlus'' species. Reconstructions of its skull anatomy must therefore draw from eight separate ''Q. lawsoni'' specimens which preserve skull elements. Based on the length of the mandible (lower jaw), the skull of ''Q. lawsoni'' likely measured about in length. The distance between the condyloid (articular) processes of the mandible is around . The ratio between the length of the skull and the length of the average dorsal (back) vertebra is very high in ''Q. lawsoni'', and is surpassed only by ''Pteranodon'' and '' Tupuxuara''. The nasoantorbital fenestra, a massive opening found in many pterosaurs which combined thenasal cavity

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nas ...

(which housed the external nostril) and antorbital fenestra

An antorbital fenestra (plural: fenestrae) is an opening in the skull that is in front of the eye sockets. This skull character is largely associated with Archosauriformes, archosauriforms, first appearing during the Triassic Period. Among Extant ...

, was very large in ''Q. lawsoni'', occupying about a third of the total length of the skull. In the largest specimen, TMM 41961-1.1, it measured in length and in height. ''Q. lawsoni''maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

on the upper jaw, and the dentary on the lower jaw. Beak tips are not preserved in any specimen, so it is not clear whether its tip was sharp or had some other morphology, such as a keel. The dentary had a slight sinusoidal

A sine wave, sinusoidal wave, or sinusoid (symbol: ∿) is a periodic wave whose waveform (shape) is the trigonometric sine function. In mechanics, as a linear motion over time, this is '' simple harmonic motion''; as rotation, it correspond ...

curve, which is also observed in '' Hatzegopteryx''. The mandibular symphyses would have widened slightly as the jaw opened, slightly separating the mandibles, which has led to suggestions that some sort of gular pouch was present. At the base of the beak, formed from the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

, was a crest, referred to by some authors as a sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

. A premaxillary crest is also observed in ''Wellnhopterus'', though is smaller and more anterior. The exact form of the crest in ''Q. lawsoni'' has yet to be determined, due to the poor preservation of the rear half of ''Q. lawsoni''s skull. From what is known, two distinct morphotypes have been suggested: one with a square sagittal crest and a tall nasoantorbital fenestra, and one with a more semicircular sagittal crest and a shorter nasoantorbital fenestra. Additionally, one morphotype is larger than the other, and has a proportionally shorter beak. Despite their differences, both share the diagnostic traits of ''Q. lawsoni'', and are considered the same species. The reason for there being two morphotypes is unclear, though it may correlate to individual variation, ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the ovum, egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to t ...

, or sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

.

Skeleton

Like other pterosaurs, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' had light, hollow bones, supported internally by struts called trabeculae. The neck of ''Q. lawsoni'', measured from the third cervical (neck)

Like other pterosaurs, ''Quetzalcoatlus'' had light, hollow bones, supported internally by struts called trabeculae. The neck of ''Q. lawsoni'', measured from the third cervical (neck) vertebra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

to the seventh, has been estimated at . It consisted of nine elongated vertebrae, which were procoelous, meaning that they were concave at the front. All of them were compressed dorsoventrally (top to bottom), and were better suited for dorsoventral motion than lateral

Lateral is a geometric term of location which may also refer to:

Biology and healthcare

* Lateral (anatomy), a term of location meaning "towards the side"

* Lateral cricoarytenoid muscle, an intrinsic muscle of the larynx

* Lateral release ( ...

(side-to-side) motion. However, the lateral range of motion was still extensive, and the neck and head could swing left and right in an arc of about 180 degrees. Like in other azhdarchoids, the cervical vertebrae were low, with neural arches that were essentially inside the centrum. In most azhdarchids, the neural spine of the seventh cervical vertebra was fairly long. This was not the case in ''Q. lawsoni'', where the neural spine was shorter. Internally, the cervical vertebrae were supported by trabeculae that increased their buckling load substantially (about 90%). This may have been an adaptation for counteracting shear force

In solid mechanics, shearing forces are unaligned forces acting on one part of a Rigid body, body in a specific direction, and another part of the body in the opposite direction. When the forces are Collinearity, collinear (aligned with each ot ...

s exerted on the neck while in flight, though may have also enabled agonistic neck-bashing behaviors like those seen in giraffe

The giraffe is a large Fauna of Africa, African even-toed ungulate, hoofed mammal belonging to the genus ''Giraffa.'' It is the Largest mammals#Even-toed Ungulates (Artiodactyla), tallest living terrestrial animal and the largest ruminant on ...

s. While airborne, the neck of ''Q. northropi'' would have likely assumed a slight S-shaped curve, similar to swans. Similar to other azhdarchids, the torso was proportionally small, about half as long again as the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

. In ''Quetzalcoatlus'' specifically, the vertebrae at the base of the neck and the pectoral girdle (shoulder girdle) are poorly known. The first four dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

The fus ...

(back) vertebrae are fused into a notarium, as in some other pterosaurs and birds, particularly ornithocheiroids. The vertebral count of the notarium is unlike '' Zhejiangopterus'', which had six notarial vertebrae, but like '' Azhdarcho''. Most other dorsal vertebrae are absent, except for three which had been integrated into the sacrum. Around seven dorsal vertebrae were free of the notarium and sacrum. Four true sacral vertebrae are preserved, though there were likely seven in all. No caudal (tail) vertebrae are preserved. ''Quetzalcoatlus''

''Quetzalcoatlus''scapula