Quehanna Wild Area on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Quehanna Wild Area () is a

The southern part of Quehanna Wild Area is now in parts of Covington, Girard, and Karthaus townships in Clearfield County; they were incorporated in 1817, 1832, and 1841. The northwest part of Quehanna is in Benezette Township in

The southern part of Quehanna Wild Area is now in parts of Covington, Girard, and Karthaus townships in Clearfield County; they were incorporated in 1817, 1832, and 1841. The northwest part of Quehanna is in Benezette Township in  As lumber became an industry in Pennsylvania, the rivers and creeks were declared public highways by the

As lumber became an industry in Pennsylvania, the rivers and creeks were declared public highways by the  There were only two major roads on the Quehanna plateau in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both originally turnpikes. The Caledonia Pike ran east–west from Bellefonte to Smethport, and passed south of what became the wild area, while the Driftwood Pike ran from near Karthaus north to

There were only two major roads on the Quehanna plateau in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both originally turnpikes. The Caledonia Pike ran east–west from Bellefonte to Smethport, and passed south of what became the wild area, while the Driftwood Pike ran from near Karthaus north to

As the timber was exhausted and the land burned, many companies abandoned their holdings. Conservationists such as Joseph Rothrock became concerned that the forests would not regrow without proper management. They called for a change in the philosophy of forest management and for the state to purchase land from the lumber companies. In 1895, Rothrock was appointed the first forestry commissioner in what became the Pennsylvania Department of Forests and Waters, the forerunner of today's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). In 1897, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed legislation that authorized the purchase of "unseated lands for forest reservations", and the first of the Pennsylvania state forest lands were acquired the following year.

The state first bought land that became the Moshannon State Forest in 1898; the second purchase, and first in the Quehanna region, was in the Three Runs area, acquired for $1 an acre ($2.47 a hectare) in 1900. Three smaller state forests (Karthaus, Sinnemahoning, and Moshannon) were merged to form the present Moshannon State Forest; in 1997, the forest covered . The first purchase for the Elk State Forest was made in 1900, and by 1997 it encompassed . Forty-six percent, or , of the total of Quehanna Wild Area lies in the Elk State Forest. The remainder lies in the Moshannon State Forest.

The state established a tree nursery in the Moshannon State Forest in 1911, which became the largest in Pennsylvania before it closed in 1980. In addition to planting millions of trees, in 1913 the state encouraged use of state forest lands by allowing permanent leases for camp sites; when the state stopped issuing new permits in 1970, 4,500 campsites had been leased. The

As the timber was exhausted and the land burned, many companies abandoned their holdings. Conservationists such as Joseph Rothrock became concerned that the forests would not regrow without proper management. They called for a change in the philosophy of forest management and for the state to purchase land from the lumber companies. In 1895, Rothrock was appointed the first forestry commissioner in what became the Pennsylvania Department of Forests and Waters, the forerunner of today's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). In 1897, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed legislation that authorized the purchase of "unseated lands for forest reservations", and the first of the Pennsylvania state forest lands were acquired the following year.

The state first bought land that became the Moshannon State Forest in 1898; the second purchase, and first in the Quehanna region, was in the Three Runs area, acquired for $1 an acre ($2.47 a hectare) in 1900. Three smaller state forests (Karthaus, Sinnemahoning, and Moshannon) were merged to form the present Moshannon State Forest; in 1997, the forest covered . The first purchase for the Elk State Forest was made in 1900, and by 1997 it encompassed . Forty-six percent, or , of the total of Quehanna Wild Area lies in the Elk State Forest. The remainder lies in the Moshannon State Forest.

The state established a tree nursery in the Moshannon State Forest in 1911, which became the largest in Pennsylvania before it closed in 1980. In addition to planting millions of trees, in 1913 the state encouraged use of state forest lands by allowing permanent leases for camp sites; when the state stopped issuing new permits in 1970, 4,500 campsites had been leased. The  During the

During the

In 1956 Curtiss-Wright began isotope work at the facility, and ''

In 1956 Curtiss-Wright began isotope work at the facility, and ''

A group of NUMEC employees discovered that irradiating hardwood treated with plastics produced very durable flooring. In 1978 they formed PermaGrain Products, Inc. as a separate company from ARCO, and purchased the rights to the process as well as "the main irradiator, a smaller shielded irradiator and related equipment". PermaGrain sold the flooring for use in

A group of NUMEC employees discovered that irradiating hardwood treated with plastics produced very durable flooring. In 1978 they formed PermaGrain Products, Inc. as a separate company from ARCO, and purchased the rights to the process as well as "the main irradiator, a smaller shielded irradiator and related equipment". PermaGrain sold the flooring for use in  After the accidental release, another radiological survey was performed, and the state government concluded that PermaGrain needed to be relocated. The DCNR made the policy decision that Quehanna Wild Area would be closed to industrial uses. After looking at multiple sites with Clearfield County development authorities, a new site for PermaGrain Products was purchased, and the company submitted its plans for a new building and license to the NRC in October 2001. In order to approve the move to the new site, the NRC required PermaGrain to provide an inventory of all their cobalt-60 sources, dispose of a damaged source, and dispose of any other sources not mechanically certified. However in late December 2002, PermaGrain filed for bankruptcy under Chapter Seven. PermaGrain had employed 135 people in 1988 and 80 in 1995.

When PermaGrain went bankrupt, about 100,000 curies of cobalt-60 were abandoned at the reactor facility, which was now under the control of Pennsylvania's government. The DEP assumed responsibility for the NRC license and legacy contamination. The

After the accidental release, another radiological survey was performed, and the state government concluded that PermaGrain needed to be relocated. The DCNR made the policy decision that Quehanna Wild Area would be closed to industrial uses. After looking at multiple sites with Clearfield County development authorities, a new site for PermaGrain Products was purchased, and the company submitted its plans for a new building and license to the NRC in October 2001. In order to approve the move to the new site, the NRC required PermaGrain to provide an inventory of all their cobalt-60 sources, dispose of a damaged source, and dispose of any other sources not mechanically certified. However in late December 2002, PermaGrain filed for bankruptcy under Chapter Seven. PermaGrain had employed 135 people in 1988 and 80 in 1995.

When PermaGrain went bankrupt, about 100,000 curies of cobalt-60 were abandoned at the reactor facility, which was now under the control of Pennsylvania's government. The DEP assumed responsibility for the NRC license and legacy contamination. The

On September 20, 1967, two Bureau of Forestry employees attempted to remove a metal ladder from a metal

On September 20, 1967, two Bureau of Forestry employees attempted to remove a metal ladder from a metal

The industrial complex covers about on both sides of Quehanna Highway at the southeast edge of the Quehanna Wild Area. Although the industrial complex lies within the historic 16-sided polygon, it is no longer part of the wild area. After Curtiss-Wright's lease ended and it donated six of the eight buildings in the complex to the state in 1963, Pennsylvania formed the Commonwealth Industrial Research Corporation to administer and lease the Quehanna facilities, which it did until 1967. Over the years a series of tenants have occupied parts of the industrial complex. One company manufactured logging

The industrial complex covers about on both sides of Quehanna Highway at the southeast edge of the Quehanna Wild Area. Although the industrial complex lies within the historic 16-sided polygon, it is no longer part of the wild area. After Curtiss-Wright's lease ended and it donated six of the eight buildings in the complex to the state in 1963, Pennsylvania formed the Commonwealth Industrial Research Corporation to administer and lease the Quehanna facilities, which it did until 1967. Over the years a series of tenants have occupied parts of the industrial complex. One company manufactured logging

In December 1970 the state forest commission officially changed the designation from Quehanna Wilderness Area to Quehanna Wild Area, making it the first state forest wild area in Pennsylvania. Elk and Moshannon state forests jointly administer Quehanna's ; for comparison, this is over three times larger than the area of

In December 1970 the state forest commission officially changed the designation from Quehanna Wilderness Area to Quehanna Wild Area, making it the first state forest wild area in Pennsylvania. Elk and Moshannon state forests jointly administer Quehanna's ; for comparison, this is over three times larger than the area of  The state forest system also has natural areas, with more restricted usage. According to the Bureau of Forestry, "A natural area is an area of unique scenic, historic, geologic or ecological value that will be maintained in a natural condition by allowing physical and biological processes to operate, usually without direct human intervention." Quehanna Wild Area contains two state forest natural areas: the M.K. Goddard/Wykoff Run Natural Area in the center, and the Marion Brooks Natural Area on the northwest edge. Note: this includes four chapters on sites within the Quehanna Wild Area, Marion Brooks Natural Area (3), Beaver Run Dam Wildlife Viewing Area (4), Hoover Farm Wildlife Viewing Area (5), and M.K. Goddard/Wykoff Run Natural Area (6). Marion Brooks Natural Area, known for its stand of

The state forest system also has natural areas, with more restricted usage. According to the Bureau of Forestry, "A natural area is an area of unique scenic, historic, geologic or ecological value that will be maintained in a natural condition by allowing physical and biological processes to operate, usually without direct human intervention." Quehanna Wild Area contains two state forest natural areas: the M.K. Goddard/Wykoff Run Natural Area in the center, and the Marion Brooks Natural Area on the northwest edge. Note: this includes four chapters on sites within the Quehanna Wild Area, Marion Brooks Natural Area (3), Beaver Run Dam Wildlife Viewing Area (4), Hoover Farm Wildlife Viewing Area (5), and M.K. Goddard/Wykoff Run Natural Area (6). Marion Brooks Natural Area, known for its stand of

Quehanna Wild Area lies at an elevation of on the

Quehanna Wild Area lies at an elevation of on the

On May 31, 1985, an outbreak of 43 tornadoes struck northeastern

On May 31, 1985, an outbreak of 43 tornadoes struck northeastern

The clearcutting and repeated fires changed all of this. New growth was often composed of different plants and trees than had originally been there. Near Beaver Run in Quehanna there are wetlands that were originally hemlock forest. Hemlocks transpiration, transpire large amounts of water and once they were gone the soil was too wet to support most trees; the bracken and ferns that replaced the hemlocks altered the soil qualities to discourage trees as well. Within the Quehanna Wild Area are wetlands. Fires and erosion removed nutrients from the soil, and in some areas the soil was so poor in nutrients that only white birch, a pioneer species, would grow there. Marion Brooks Natural Area has the largest stand of white birch in Pennsylvania and the eastern United States. These trees are now 80 to 90 years old and reaching the end of their lifespans.

Besides forest fires and tornado damage, there have been other threats to Quehanna's forests in the 20th century. Many trees were lost when chestnut blight wiped out the American chestnut trees by 1925; in the Quehanna area, this species constituted between one-quarter and one-half of the hardwoods. In the 1960s, White oak, white and chestnut oak trees had high mortality from pit scale insects and associated fungi. Larvae of Archips semiferanus, oak leaf roller moths, which folivore, defoliate oaks, first appeared on of Quehanna Wild Area in the late 1960s; at their peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s they had defoliated of Moshannon State Forest and in Elk State Forest, with moderate to heavy tree mortality. A similar pest, Croesia semipurpurana, oak leaf tier, stripped of oaks in Elk State Forest by 1970. The gypsy moth defoliated over of deciduous trees in the 1970s and 1980s. The forests within the Quehanna Important Bird Area are 84 percent hardwoods, 4 percent mixed hardwood and evergreens, less than 1 percent evergreens, 7 percent transitional between forests and fields, and 3 percent perennial herbaceous plants. As well as trees, the forests have blueberry and huckleberry bushes and thickets of Kalmia latifolia, mountain laurel and rhododendron.

The clearcutting and repeated fires changed all of this. New growth was often composed of different plants and trees than had originally been there. Near Beaver Run in Quehanna there are wetlands that were originally hemlock forest. Hemlocks transpiration, transpire large amounts of water and once they were gone the soil was too wet to support most trees; the bracken and ferns that replaced the hemlocks altered the soil qualities to discourage trees as well. Within the Quehanna Wild Area are wetlands. Fires and erosion removed nutrients from the soil, and in some areas the soil was so poor in nutrients that only white birch, a pioneer species, would grow there. Marion Brooks Natural Area has the largest stand of white birch in Pennsylvania and the eastern United States. These trees are now 80 to 90 years old and reaching the end of their lifespans.

Besides forest fires and tornado damage, there have been other threats to Quehanna's forests in the 20th century. Many trees were lost when chestnut blight wiped out the American chestnut trees by 1925; in the Quehanna area, this species constituted between one-quarter and one-half of the hardwoods. In the 1960s, White oak, white and chestnut oak trees had high mortality from pit scale insects and associated fungi. Larvae of Archips semiferanus, oak leaf roller moths, which folivore, defoliate oaks, first appeared on of Quehanna Wild Area in the late 1960s; at their peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s they had defoliated of Moshannon State Forest and in Elk State Forest, with moderate to heavy tree mortality. A similar pest, Croesia semipurpurana, oak leaf tier, stripped of oaks in Elk State Forest by 1970. The gypsy moth defoliated over of deciduous trees in the 1970s and 1980s. The forests within the Quehanna Important Bird Area are 84 percent hardwoods, 4 percent mixed hardwood and evergreens, less than 1 percent evergreens, 7 percent transitional between forests and fields, and 3 percent perennial herbaceous plants. As well as trees, the forests have blueberry and huckleberry bushes and thickets of Kalmia latifolia, mountain laurel and rhododendron.

Still other animals seem to thrive regardless of the maturity of the forest or the presence of the understory. Common animals found in Quehanna include chipmunks, North American porcupine, porcupine, and North American beaver, beaver, omnivores such as the black bear and raccoon, and predators like bobcat, red fox, and

Still other animals seem to thrive regardless of the maturity of the forest or the presence of the understory. Common animals found in Quehanna include chipmunks, North American porcupine, porcupine, and North American beaver, beaver, omnivores such as the black bear and raccoon, and predators like bobcat, red fox, and

According to the DCNR, Quehanna Wild Area is for the public "to see, use and enjoy for such activities as hiking, hunting, and fishing". The main hiking trail on the Quehanna plateau is the

According to the DCNR, Quehanna Wild Area is for the public "to see, use and enjoy for such activities as hiking, hunting, and fishing". The main hiking trail on the Quehanna plateau is the

Official Quehanna Trail Map, Eastern Section (shows all of Quehanna Wild Area)

Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. {{Featured article Nature reserves in Pennsylvania Protected areas of Clearfield County, Pennsylvania Protected areas of Cameron County, Pennsylvania Protected areas of Elk County, Pennsylvania Allegheny Plateau Protected areas established in 1965 Civilian Conservation Corps in Pennsylvania Works Progress Administration in Pennsylvania

protected area

Protected areas or conservation areas are locations which receive protection because of their recognized natural or cultural values. Protected areas are those areas in which human presence or the exploitation of natural resources (e.g. firewood ...

within parts of Cameron

Cameron may refer to:

People

* Clan Cameron, a Scottish clan

* Cameron (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Cameron (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

;Mononym

* Cam'ron (born 19 ...

, Clearfield and Elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

counties in the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its so ...

of Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania, officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a U.S. state, state spanning the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern United States, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes region, Great Lakes regions o ...

; with a total area of , it covers parts of Elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

and Moshannon State Forests. Founded in the 1950s as a nuclear research

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

center, Quehanna has a legacy of radioactive

Radioactive decay (also known as nuclear decay, radioactivity, radioactive disintegration, or nuclear disintegration) is the process by which an unstable atomic nucleus loses energy by radiation. A material containing unstable nuclei is conside ...

and toxic waste

Toxic waste is any unwanted material in all forms that can cause harm (e.g. by being inhaled, swallowed, or absorbed through the skin). Mostly generated by industry, consumer products like televisions, computers, and phones contain toxic chemi ...

contamination, while also being the largest state forest wild area in Pennsylvania, with herds of elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

. The wild area is bisected by the Quehanna Highway and is home to second growth forest

A secondary forest (or second-growth forest) is a forest or woodland area which has regenerated through largely natural processes after human-caused disturbances, such as timber harvest or agriculture clearing, or equivalently disruptive natura ...

with mixed hardwoods

Hardwood is wood from angiosperm trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostly evergreen. Hardwood (which comes ...

and evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has Leaf, foliage that remains green and functional throughout the year. This contrasts with deciduous plants, which lose their foliage completely during the winter or dry season. Consisting of many diffe ...

s. Quehanna has two state forest natural areas: the M.K. Goddard/Wykoff Run Natural Area, and the Marion Brooks Natural Area. The latter has the largest stand of white birch

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wavelen ...

in Pennsylvania and the eastern United States.

The land that became Quehanna Wild Area was home to Native Americans, including the Susquehannock

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

T ...

and Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

, before it was purchased by the United States in 1784. Settlers soon moved into the region and, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the logging

Logging is the process of cutting, processing, and moving trees to a location for transport. It may include skidder, skidding, on-site processing, and loading of trees or trunk (botany), logs onto logging truck, trucksvirgin forest

An old-growth forest or primary forest is a forest that has developed over a long period of time without Disturbance (ecology), disturbance. Due to this, old-growth forests exhibit unique ecological features. The Food and Agriculture Organizati ...

s; clearcutting

Clearcutting, clearfelling or clearcut logging is a forestry/logging practice in which most or all trees in an area are uniformly cut down. Along with Shelterwood cutting, shelterwood and Seed tree, seed tree harvests, it is used by foresters t ...

and forest fires transformed the once verdant land into the "Pennsylvania Desert". Pennsylvania bought this land for its state forests

A state forest or national forest is a forest that is administered or protected by a sovereign or federated state, or territory.

Background

State forests are forests that are administered or protected by some agency of a sovereign or federate ...

, and in the 1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

worked to improve them. In 1955 the Curtiss-Wright

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation is an American manufacturer and services provider headquartered in Davidson, North Carolina, with factories and operations in and outside the United States. Created in 1929 from the consolidation (business), consoli ...

Corporation bought of state forest to focus on developing nuclear-powered jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine, discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition may include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

s. They named their facility Quehanna for the nearby West Branch Susquehanna River

The West Branch Susquehanna River is one of the two principal branches, along with the North Branch, of the Susquehanna River in the Northeastern United States. The North Branch, which rises in upstate New York, is generally regarded as the ex ...

, itself named for the Susquehannocks.

Curtiss-Wright left in 1960, after which a succession of tenants further contaminated the nuclear reactor facility and its hot cell

A hot cell is a name given to a containment chamber that is shielded against nuclear radiation. The word ''hot'' refers to radioactivity.

Hot cells are used in both the nuclear-energy and the nuclear-medicines industries.

They are required to ...

s with radioactive isotopes

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess numbers of either neutrons or protons, giving it excess nuclear energy, and making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ...

, including strontium-90

Strontium-90 () is a radioactive isotope of strontium produced by nuclear fission, with a half-life of 28.79 years. It undergoes β− decay into yttrium-90, with a decay energy of 0.546 MeV. Strontium-90 has applications in medicine a ...

and cobalt-60

Cobalt-60 (Co) is a synthetic radioactive isotope of cobalt with a half-life of 5.2714 years. It is produced artificially in nuclear reactors. Deliberate industrial production depends on neutron activation of bulk samples of the monoisotop ...

. The manufacture of radiation-treated hardwood flooring continued until 2002. Pennsylvania reacquired the land in 1963 and 1967, and in 1965 established Quehanna as a wild area, albeit one with a nuclear facility and industrial complex. The cleanup

Cleanup, clean up or clean-up may refer to:

* Cleanup (animation), a stage of animation workflow

* Clean-up (environment), environmental action to remove litter from a place

* Cleanup hitter, a baseball position

* Clean-up Records, a record la ...

of the reactor and hot cells took over eight years and cost $30 million; the facility was demolished and its nuclear license terminated in 2009. Since 1992 the industrial complex has been home to Quehanna Motivational Boot Camp, a minimum-security prison. Quehanna Wild Area has many sites where radioactive and toxic waste was buried, some of which have been cleaned up while others were dug up by black bears and white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known Common name, commonly as the whitetail and the Virginia deer, is a medium-sized species of deer native to North America, North, Central America, Central and South America. It is the ...

.

In 1970 the name was officially changed to Quehanna Wild Area, and later that decade a portion of the Quehanna Trail

The Quehanna Trail is a hiking trail in north-central Pennsylvania, forming a loop through Moshannon State Forest and Elk State Forest. For about 34 miles, the trail traverses Quehanna Wild Area, and its main trailhead is at Parker Dam State ...

was routed through the wild area. Primitive camping

Camping is a form of outdoor recreation or outdoor education involving overnight stays with a basic temporary shelter such as a tent. Camping can also include a recreational vehicle, sheltered cabins, a permanent tent, a shelter such as a Bivy bag ...

by hikers is allowed, but the area has no permanent residents. Several other trails are open to cross-country skiing

Cross-country skiing is a form of skiing whereby skiers traverse snow-covered terrain without use of ski lifts or other assistance. Cross-country skiing is widely practiced as a sport and recreational activity; however, some still use it as a m ...

in the winter, but closed to vehicles. Quehanna is on the Allegheny Plateau

The Allegheny Plateau ( ) is a large dissected plateau area of the Appalachian Mountains in western and central New York, northern and western Pennsylvania, northern and western West Virginia, and eastern Ohio. It is divided into the unglacia ...

and was struck by a tornado in 1985. Defoliating insects have further damaged the forests. Quehanna Wild Area was named an Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

by the Pennsylvania Audubon Society

The National Audubon Society (Audubon; ) is an American non-profit environmental organization dedicated to conservation of birds and their habitats. Located in the United States and incorporated in 1905, Audubon is one of the oldest of such orga ...

, and is home to many species of birds and animals. Eco-tourists come to see the birds and elk, and hunters come for the elk, coyote

The coyote (''Canis latrans''), also known as the American jackal, prairie wolf, or brush wolf, is a species of canis, canine native to North America. It is smaller than its close relative, the Wolf, gray wolf, and slightly smaller than the c ...

, and other game.

History

Native Americans

TheIroquoian

The Iroquoian languages () are a language family of indigenous peoples of North America. They are known for their general lack of labial consonants. The Iroquoian languages are polysynthetic and head-marking.

As of 2020, almost all surviving I ...

-speaking Susquehannock

The Susquehannock, also known as the Conestoga, Minquas, and Andaste, were an Iroquoian Peoples, Iroquoian people who lived in the lower Susquehanna River watershed in what is now Pennsylvania. Their name means “people of the muddy river.”

T ...

s were the earliest recorded inhabitants of the West Branch Susquehanna River

The West Branch Susquehanna River is one of the two principal branches, along with the North Branch, of the Susquehanna River in the Northeastern United States. The North Branch, which rises in upstate New York, is generally regarded as the ex ...

basin, which includes Quehanna Wild Area. They were a matriarchal

Matriarchy is a social system in which positions of power and privilege are held by women. In a broader sense it can also extend to moral authority, social privilege, and control of property. While those definitions apply in general English, ...

society that lived in stockade

A stockade is an enclosure of palisades and tall walls, made of logs placed side by side vertically, with the tops sharpened as a defensive wall.

Etymology

''Stockade'' is derived from the French word ''estocade''. The French word was derived f ...

d villages of large long house

A longhouse or long house is a type of long, proportionately narrow, single-room building for communal dwelling. It has been built in various parts of the world including Asia, Europe, and North America.

Many were built from lumber, timber and ...

s.Wallace, "Indians in Pennsylvania", pp. 4–12, 84–89, 99–105, 145–148, 157–164. The Susquehannocks' numbers were greatly reduced by disease and warfare with the Five Nations of the Iroquois

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

, and by 1675 they had died out, moved away, or been assimilated into other tribes. After this, the Iroquois exercised nominal control of the lands of the West Branch Susquehanna River valley. They also lived in long houses, primarily in what is now New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, and had a strong confederacy which gave them power beyond their numbers. To fill the void left by the demise of the Susquehannocks, the Iroquois encouraged such displaced eastern tribes as the Shawnee

The Shawnee ( ) are a Native American people of the Northeastern Woodlands. Their language, Shawnee, is an Algonquian language.

Their precontact homeland was likely centered in southern Ohio. In the 17th century, they dispersed through Ohi ...

and Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

(or Delaware) to settle in the West Branch watershed.Donehoo, pp. 215–220.

The Seneca tribe of the Iroquois hunted in much of Pennsylvania and the Quehanna area. The Iroquois and other tribes used the Great Shamokin Path

The Great Shamokin Path (also known as the "Shamokin Path") was a major Native American trail in the U.S. State of Pennsylvania that ran from the native village of Shamokin (modern-day Sunbury) along the left bank of the West Branch Susqueha ...

, the major native east–west path connecting the Susquehanna and Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ; ; ) is a tributary of the Ohio River that is located in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York in the United States. It runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border, nor ...

basins, which passed south of what is now the wild area. The native village of Chinklacamoose (or Chingleclamouche) was on this path at the West Branch Susquehanna River, at what is now Clearfield to the southwest of Quehanna. The Sinnemahoning Path along Sinnemahoning Creek

Sinnemahoning Creek is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 8, 2011 tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Cameron and Clinton counties, Pennsylvania, in ...

ran north of Quehanna; as the path with the gentlest grade, it may have been the route the first Paleo-Indians

Paleo-Indians were the first peoples who entered and subsequently inhabited the Americas towards the end of the Late Pleistocene period. The prefix ''paleo-'' comes from . The term ''Paleo-Indians'' applies specifically to the lithic period in ...

took entering this part of Pennsylvania from the west.Wallace, "Indian Paths in Pennsylvania", pp. 27–30, 66–72, 155–156.

The French and Indian War

The French and Indian War, 1754 to 1763, was a colonial conflict in North America between Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and Kingdom of France, France, along with their respective Native Americans in the United States, Native American ...

(1754–1763) and the subsequent colonial expansion encouraged the migration of many Native Americans westward to the Ohio River basin. In October 1784, the United States acquired a large tract of land, including what is now Quehanna Wild Area, from the Iroquois in the Second Treaty of Fort Stanwix; this acquisition is known as the Last Purchase, as it completed the series of purchases from the resident Native American tribes of lands within the boundaries of Pennsylvania, initiated by William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quakers, Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonization of the Americas, British colonial era. An advocate of democracy and religi ...

and continued by his heirs.

Although most of the Native Americans left this area of Pennsylvania, the state's Native American heritage can be found in many of its place names. The Susquehannocks were also known as the Susquehanna, from which the Susquehanna River

The Susquehanna River ( ; Unami language, Lenape: ) is a major river located in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, crossing three lower Northeastern United States, Northeast states (New York, Pennsylvani ...

and its West Branch obtained their names. In the 1950s the Curtiss-Wright

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation is an American manufacturer and services provider headquartered in Davidson, North Carolina, with factories and operations in and outside the United States. Created in 1929 from the consolidation (business), consoli ...

Corporation coined the name "Quehanna" for its nuclear reservation, which it derived from the last three syllables of "Susquehanna",Fergus, pp. 117–120, 181–183. "in honor of the river that drained the entire region". Part of Quehanna Wild Area lies in the Moshannon State Forest, named for Moshannon Creek

Moshannon Creek is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed August 8, 2011 tributary of the West Branch Susquehanna River in Centre County, Pennsylvania, Centre County, Pennsylv ...

, which means "moose stream" or "elk stream" in the Lenape language

The Delaware languages, also known as the Lenape languages (), are Munsee and Unami, two closely related languages of the Eastern Algonquian subgroup of the Algonquian language family. Munsee and Unami were spoken aboriginally by the Lenape ...

. Sinnemahoning Creek's name means "stony salt lick

A mineral lick (also known as a salt lick) is a place where animals can go to lick essential mineral nutrients from a deposit of salts and other minerals. Mineral licks can be naturally occurring or artificial (such as blocks of salt that far ...

" in Lenape.

Lumber era

Prior to the arrival ofWilliam Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer, religious thinker, and influential Quakers, Quaker who founded the Province of Pennsylvania during the British colonization of the Americas, British colonial era. An advocate of democracy and religi ...

and his Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

colonists in 1682, forests covered up to 90 percent of what is now Pennsylvania: more than of eastern white pine

''Pinus strobus'', commonly called the eastern white pine, northern white pine, white pine, Weymouth pine (British), and soft pine is a large pine native to eastern North America. It occurs from Newfoundland, Canada, west through the Great Lake ...

, eastern hemlock

''Tsuga canadensis'', also known as eastern hemlock, eastern hemlock-spruce, or Canadian hemlock, and in the French-speaking regions of Canada as ''pruche du Canada'', is a coniferous tree native to eastern North America. It is the state tree of ...

, and a mix of hardwood

Hardwood is wood from Flowering plant, angiosperm trees. These are usually found in broad-leaved temperate and tropical forests. In temperate and boreal ecosystem, boreal latitudes they are mostly deciduous, but in tropics and subtropics mostl ...

s. Scull's 1770 map of the Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn, who received the land through a grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania was derived from ...

showed the colonists' ignorance of the land north of the West Branch Susquehanna River; Sinnemahoning Creek was missing, and the region that includes Quehanna was labeled "Buffaloe Swamp".Seeley, p. 3. This began to change when the land was purchased from the Iroquois in 1784, and became part of Northumberland County. In 1795 it became part of Lycoming County

Lycoming County is a county in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. As of the 2020 census, the population was 114,188. Its county seat is Williamsport. The county is part of the North Central region of the commonwealth.

Lycoming County compris ...

; as the new county was divided into more townships, Quehanna became part of Chingleclamouche Township (named for the native village). Chingleclamouche Township was included in Clearfield County when it was established in 1804. Later it was divided between at least three counties and many townships, and no longer exists under that name.

Elk County Elk County is the name of several places:

* Elk County, Kansas

* Elk County, Pennsylvania

* Ełk County

__NOTOC__

Ełk County () is a unit of territorial administration and local government (powiat) in the Warmian–Masurian Voivodeship, northe ...

, established in 1843. The northeast part of Quehanna is in Cameron County (incorporated in 1860) in Gibson Township, which was formed in 1804 while part of Clearfield County.

The first European American

European Americans are Americans of European ancestry. This term includes both people who descend from the first European settlers in the area of the present-day United States and people who descend from more recent European arrivals. Since th ...

settlers arrived in Chingleclamouche Township in about 1793, and the first sawmill in Clearfield County began operating in 1805. Settlers initially occupied land along the river and creeks, as these provided a means of transportation. Some settlers would harvest timber and float it downstream once a year to make money for items they could not produce themselves, but by 1820 the first full-time lumbering operations began in the region. The white pine was the most sought after tree, yielding spars for ships and timber for buildings. Hardwoods were also harvested, and eventually hemlocks were cut for their wood and their bark, which contained tannin

Tannins (or tannoids) are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and Precipitation (chemistry), precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids. The term ''tannin'' is widel ...

s used in tanning leather.Seeley, pp. 4–6.

As lumber became an industry in Pennsylvania, the rivers and creeks were declared public highways by the

As lumber became an industry in Pennsylvania, the rivers and creeks were declared public highways by the Pennsylvania General Assembly

The Pennsylvania General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The legislature convenes in the State Capitol building in Harrisburg. In colonial times (1682–1776), the legislature was known as the Pennsylvani ...

. This permitted their use to float logs to sawmills and markets. Log boom

A log boom (sometimes called a log fence or log bag) is a barrier placed in a river, designed to collect and or contain floating logs timbered from nearby forests. The term is also used as a place where logs were collected into booms, as at th ...

s were placed on the West Branch Susquehanna River to catch the floating timber; Lock Haven built a boom in 1849, and Williamsport's Susquehanna Boom opened in 1851. Businesses purchased vast tracts of land and built splash dam

A splash dam was a temporary wooden dam used to raise the water level in streams to float logs downstream to sawmills. By impounding water and allowing it to be released on the log drive's schedule, these dams allowed many more logs to be brought ...

s on the creeks; these dams controlled water in small streams that would otherwise be unable to carry logs and rafts. For example, in 1871 a single splash dam on the Bennett Branch of Sinnemahoning Creek could release enough water to produce a wave high on the main stem

In hydrology, a main stem or mainstem (also known as a trunk) is "the primary downstream segment of a river, as contrasted to its tributaries". The mainstem extends all the way from one specific headwater to the outlet of the river, although t ...

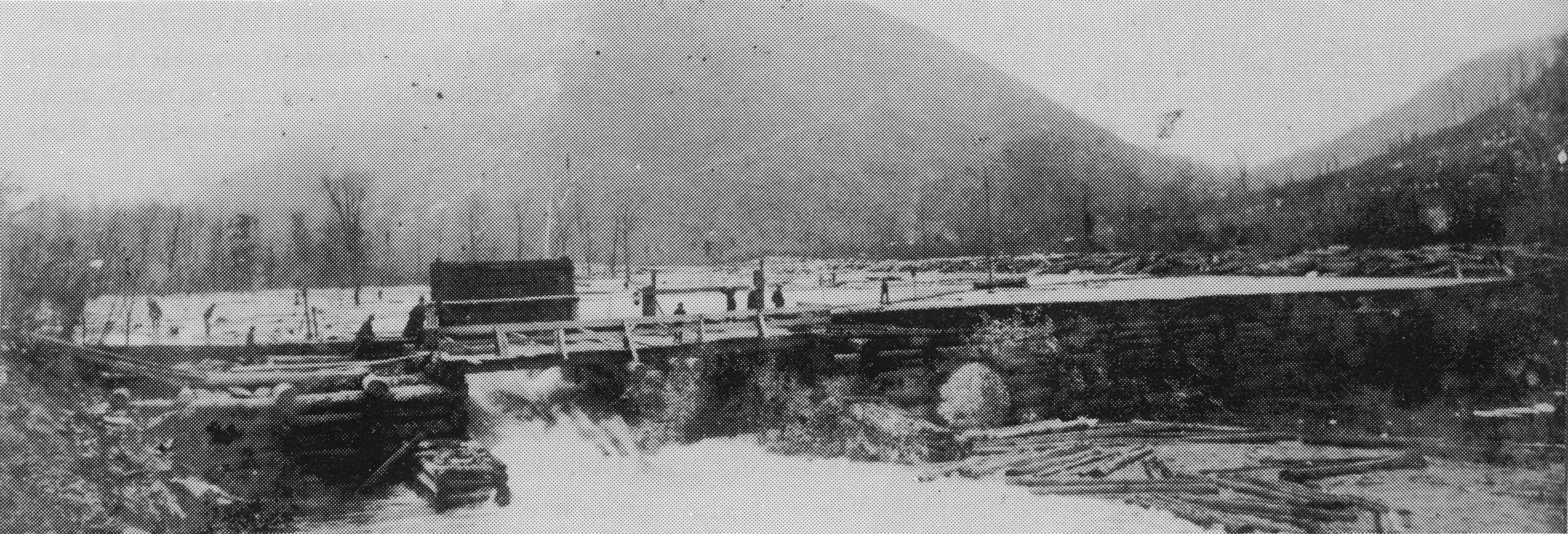

for two hours. Mosquito Creek, which drains much of the southern part of Quehanna Wild Area, had at least nine splash dams in its watershed. This was the predominant lumber transport system in the Quehanna region from 1865 to 1885 and after 1850, five different kinds of lumber rafts could be found on its streams and river.

Much of the timber was too remote to be transported via the streams, and logging railroads

A forest railway, forest tram, timber line, logging railway or logging railroad is a mode of railway transport which is used for forestry tasks, primarily the transportation of felled logs to sawmills or railway stations.

In most cases this f ...

were the next development in the Quehanna lumber era. In or around 1880, these railroads allowed the clearcutting

Clearcutting, clearfelling or clearcut logging is a forestry/logging practice in which most or all trees in an area are uniformly cut down. Along with Shelterwood cutting, shelterwood and Seed tree, seed tree harvests, it is used by foresters t ...

of the remaining forests. The Quehanna plateau was unusual in using standard gauge

A standard-gauge railway is a railway with a track gauge of . The standard gauge is also called Stephenson gauge (after George Stephenson), international gauge, UIC gauge, uniform gauge, normal gauge in Europe, and SGR in East Africa. It is the ...

track for its logging railroads: most such railways were narrow gauge

A narrow-gauge railway (narrow-gauge railroad in the US) is a railway with a track gauge (distance between the rails) narrower than . Most narrow-gauge railways are between and .

Since narrow-gauge railways are usually built with Minimum railw ...

. The logging railroads used special geared steam locomotive

A geared steam locomotive is a type of steam locomotive which uses gearing, usually reduction gearing, in the drivetrain, as opposed to the common directly driven design.

This gearing is part of the machinery within the locomotive and should not ...

s, such as the Shay, Climax

Climax may refer to:

Language arts

* Climax (narrative), the point of highest tension in a narrative work

* Climax (rhetoric), a figure of speech that lists items in order of importance

Biology

* Climax community, a biological community th ...

and Heisler.Seeley, pp. 6–7. Nine companies operated logging railroads in what became Moshannon State Forest; the Goodyear Lumber Company was the largest and cut much of what became Quehanna Wild Area between 1902 and 1912. The Central Pennsylvania Lumber Company logged land in the northern part of the wild area between 1907 and 1911. Note: this is a map on one side and an informational brochure on the other side.

There were only two major roads on the Quehanna plateau in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both originally turnpikes. The Caledonia Pike ran east–west from Bellefonte to Smethport, and passed south of what became the wild area, while the Driftwood Pike ran from near Karthaus north to

There were only two major roads on the Quehanna plateau in the 19th and early 20th centuries, both originally turnpikes. The Caledonia Pike ran east–west from Bellefonte to Smethport, and passed south of what became the wild area, while the Driftwood Pike ran from near Karthaus north to Driftwood

Driftwood is a wood that has been washed onto a shore or beach of a sea, lake, or river by the action of winds, tides or waves. It is part of beach wrack.

In some waterfront areas, driftwood is a major nuisance. However, the driftwood provides ...

on the Sinnemahoning, and passed through the wild area. Wagon train

''Wagon Train'' is an American Western television series that aired for eight seasons, first on the NBC television network (1957–1962) and then on ABC (1962–1965). ''Wagon Train'' debuted on September 18, 1957, and reached the top of the ...

s and railroads brought supplies to the lumber camps in the woods; some wood hicks set up small farms on cleared land that also provided food. There were at least eight farms in Quehanna, though they were not very productive because of "poorly drained acid soil and a short growing season".

The lumber era in Quehanna did not last; the old-growth

An old-growth forest or primary forest is a forest that has developed over a long period of time without Disturbance (ecology), disturbance. Due to this, old-growth forests exhibit unique ecological features. The Food and Agriculture Organizati ...

and second-growth forests were clearcut by the early 20th century. Fire had always been a hazard; the sparks from logging steam engines started many wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, or a bushfire is an unplanned and uncontrolled fire in an area of Combustibility and flammability, combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identified as a ...

s, and more wood may have been lost to fires than to logging in some areas. On the clearcut land nothing remained except the discarded, dried-out tree tops, which were very flammable; much of the land burned and was left barren. The soil was depleted of nutrients, fires baked the ground hard, and jungles of blueberries, blackberries, and mountain laurel covered the clearcut land, which became known as the "Pennsylvania Desert".Owlett, pp. 53–62.

State forests

As the timber was exhausted and the land burned, many companies abandoned their holdings. Conservationists such as Joseph Rothrock became concerned that the forests would not regrow without proper management. They called for a change in the philosophy of forest management and for the state to purchase land from the lumber companies. In 1895, Rothrock was appointed the first forestry commissioner in what became the Pennsylvania Department of Forests and Waters, the forerunner of today's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). In 1897, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed legislation that authorized the purchase of "unseated lands for forest reservations", and the first of the Pennsylvania state forest lands were acquired the following year.

The state first bought land that became the Moshannon State Forest in 1898; the second purchase, and first in the Quehanna region, was in the Three Runs area, acquired for $1 an acre ($2.47 a hectare) in 1900. Three smaller state forests (Karthaus, Sinnemahoning, and Moshannon) were merged to form the present Moshannon State Forest; in 1997, the forest covered . The first purchase for the Elk State Forest was made in 1900, and by 1997 it encompassed . Forty-six percent, or , of the total of Quehanna Wild Area lies in the Elk State Forest. The remainder lies in the Moshannon State Forest.

The state established a tree nursery in the Moshannon State Forest in 1911, which became the largest in Pennsylvania before it closed in 1980. In addition to planting millions of trees, in 1913 the state encouraged use of state forest lands by allowing permanent leases for camp sites; when the state stopped issuing new permits in 1970, 4,500 campsites had been leased. The

As the timber was exhausted and the land burned, many companies abandoned their holdings. Conservationists such as Joseph Rothrock became concerned that the forests would not regrow without proper management. They called for a change in the philosophy of forest management and for the state to purchase land from the lumber companies. In 1895, Rothrock was appointed the first forestry commissioner in what became the Pennsylvania Department of Forests and Waters, the forerunner of today's Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (DCNR). In 1897, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed legislation that authorized the purchase of "unseated lands for forest reservations", and the first of the Pennsylvania state forest lands were acquired the following year.

The state first bought land that became the Moshannon State Forest in 1898; the second purchase, and first in the Quehanna region, was in the Three Runs area, acquired for $1 an acre ($2.47 a hectare) in 1900. Three smaller state forests (Karthaus, Sinnemahoning, and Moshannon) were merged to form the present Moshannon State Forest; in 1997, the forest covered . The first purchase for the Elk State Forest was made in 1900, and by 1997 it encompassed . Forty-six percent, or , of the total of Quehanna Wild Area lies in the Elk State Forest. The remainder lies in the Moshannon State Forest.

The state established a tree nursery in the Moshannon State Forest in 1911, which became the largest in Pennsylvania before it closed in 1980. In addition to planting millions of trees, in 1913 the state encouraged use of state forest lands by allowing permanent leases for camp sites; when the state stopped issuing new permits in 1970, 4,500 campsites had been leased. The Pennsylvania Game Commission

The Pennsylvania Game Commission (PGC) is the state agency responsible for wildlife conservation ethic, conservation and management in Pennsylvania in the United States. It was originally founded years ago and currently utilizes more than 700 ful ...

began purchasing land for state game preserve

A game is a Structure, structured type of play (activity), play usually undertaken for entertainment or fun, and sometimes used as an Educational game, educational tool. Many games are also considered to be Work (human activity), work (such as p ...

s in 1920, and by 1941, State Game Lands 34, which is partly in Quehanna Wild Area, had been established. Despite these conservation efforts, major forest fires swept the Moshannon and Elk state forests in 1912, 1913, 1926, and 1930, and minor fires occurred in other years.Thorpe, pp. 16–18, 32, 59–61, 71–73.

During the

During the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, the Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) was a voluntary government unemployment, work relief program that ran from 1933 to 1942 in the United States for unemployed, unmarried men ages 18–25 and eventually expanded to ages 17–28. The CCC was ...

(CCC) established ten camps in Moshannon State Forest, and ten in Elk State Forest. The young men of the CCC planted trees, blazed new trails, built roads and bridges, and fought fires, which continued to be a problem. In 1938 a fast-moving fire in the Elk State Forest, north of Quehanna, killed eight firefighters. The CCC also built structures and established or improved many of the state parks

State parks are parks or other protected areas managed at the sub-national level within those nations which use "state" as a political subdivision. State parks are typically established by a state to preserve a location on account of its natural ...

, including Parker Dam

Parker Dam is a concrete arch-gravity dam that crosses the Colorado River downstream of Hoover Dam. Built between 1934 and 1938 by the Bureau of Reclamation, it is high, of which are below the riverbed (the deep excavation was necessary in ...

and S. B. Elliott State Parks on the western Quehanna plateau. The United States' entry into World War II ended the CCC, and all its camps were closed by the summer of 1942. The Quehanna Trail

The Quehanna Trail is a hiking trail in north-central Pennsylvania, forming a loop through Moshannon State Forest and Elk State Forest. For about 34 miles, the trail traverses Quehanna Wild Area, and its main trailhead is at Parker Dam State ...

passes near or through the sites of several former CCC camps.

Other Depression-era public works projects shaped the area. The Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

(WPA) had at least two camps for World War I veterans in the Quehanna area, and built the Karthaus emergency landing field for airmail planes, similar to those that became Mid-State Regional Airport

Mid-State Regional Airport (Mid-State Airport) is a small airport in Rush Township, Centre County in Pennsylvania, between Black Moshannon State Park to the east and Moshannon State Forest.

The airport is east of Philipsburg, from U.S. ...

and Cherry Springs Airport. The airfield was built in 1935 and 1936 along Hoover Road (the old Driftwood Pike), just north of what is now M.K. Goddard/Wykoff Run Natural Area. During World War II, the landing strip was blocked to prevent enemy planes from secretly landing there.

In 1946 the Mosquito Creek Sportsmen's Association was founded to promote conservation in the region. One of the association's initial concerns was the acidification of streams, which they originally attributed to tannic acid

Tannic acid is a specific form of tannin, a type of polyphenol. Its weak acidity (Acid dissociation constant, pKa around 6) is due to the numerous phenol groups in the structure. The chemical formula for commercial tannic acid is often given as ...

from the trees used by the beavers to construct their dams

A dam is a barrier that stops or restricts the flow of surface water or underground streams. Reservoirs created by dams not only suppress floods but also provide water for activities such as irrigation, human consumption, industrial use, ...

. With the assistance of Pennsylvania's Department of Forests and Waters, Game Commission, and Fish and Boat Commission, they dynamited 79 dams. Afterward, they discovered the water was acidic upstream of the dams too, and eventually realized that the problem was caused by acid rain

Acid rain is rain or any other form of Precipitation (meteorology), precipitation that is unusually acidic, meaning that it has elevated levels of hydrogen ions (low pH). Most water, including drinking water, has a neutral pH that exists b ...

, not the beavers. The association has operated several stations to reduce the acidity of Mosquito Creek and its tributaries, with technical assistance from the Pennsylvania State University

The Pennsylvania State University (Penn State or PSU) is a Public university, public Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related Land-grant university, land-grant research university with campuses and facilities throughout Pennsyl ...

(Penn State).

Atoms for Peace

In a December 8, 1953 speech to theUnited Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

announced a new Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

policy, and Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

enacted his program into law the following year. Atoms for Peace "made funding accessible to anyone who had the imagination, if not the ability, to harness the atom's power for peaceful purposes". Under the new program, the airplane manufacturer Curtiss-Wright Corporation

The Curtiss-Wright Corporation is an American manufacturer and services provider headquartered in Davidson, North Carolina, with factories and operations in and outside the United States. Created in 1929 from the consolidation of Curtiss, Wrigh ...

sought a large isolated area in central Pennsylvania "for the development of nuclear-powered jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine, discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition may include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

s and to conduct research in nucleonics, metallurgy

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

, ultrasonics

Ultrasound is sound with frequency, frequencies greater than 20 Hertz, kilohertz. This frequency is the approximate upper audible hearing range, limit of human hearing in healthy young adults. The physical principles of acoustic waves apply ...

, electronics

Electronics is a scientific and engineering discipline that studies and applies the principles of physics to design, create, and operate devices that manipulate electrons and other Electric charge, electrically charged particles. It is a subfield ...

, chemicals and plastics". Curtiss-Wright worked closely with the state, and in June 1955, Governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

George M. Leader signed legislation that authorized the construction of a research facility at Quehanna. The Commonwealth

A commonwealth is a traditional English term for a political community founded for the common good. The noun "commonwealth", meaning "public welfare, general good or advantage", dates from the 15th century. Originally a phrase (the common-wealth ...

of Pennsylvania sold Curtiss-Wright for $181,250 ($22.50 an acre, $55.60 a hectare), and gave the company a 99-year lease on the remaining at $30,000 a year. Curtiss-Wright controlled in a regular 16-sided polygon, which was easier to fence than a circular area.

The state constructed $1.6 million of roads to the area; the Quehanna Highway was built on parts of an old CCC road, which followed an earlier logging railroad grade. Pennsylvania also canceled 212 camp site leases to help ensure security for the installation. Curtiss-Wright built three facilities on its land. The first was a nuclear research center with a nuclear reactor

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a Nuclear fission, fission nuclear chain reaction. They are used for Nuclear power, commercial electricity, nuclear marine propulsion, marine propulsion, Weapons-grade plutonium, weapons ...

and six shielded radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'' consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, infr ...

containment

Containment was a Geopolitics, geopolitical strategic foreign policy pursued by the United States during the Cold War to prevent the spread of communism after the end of World War II. The name was loosely related to the term ''Cordon sanitaire ...

chambers for handling radioactive isotopes, referred to as hot cell

A hot cell is a name given to a containment chamber that is shielded against nuclear radiation. The word ''hot'' refers to radioactivity.

Hot cells are used in both the nuclear-energy and the nuclear-medicines industries.

They are required to ...

s, at the end of Reactor Road. The second was for jet engine trials, and had two test cells with bunkers just north of Quehanna Highway, about apart. The northern test cell was at the center of the 16-sided polygon; even if a jet engine broke its moorings, it could not leave the polygonal area. Both of these were on the land which Curtiss-Wright had purchased, which was a regular octagon

In geometry, an octagon () is an eight-sided polygon or 8-gon.

A '' regular octagon'' has Schläfli symbol and can also be constructed as a quasiregular truncated square, t, which alternates two types of edges. A truncated octagon, t is a ...

surrounded with a fence built by forest rangers, supervised from three guard houses on Quehanna Highway and Wykoff Run Road. The third installation was an industrial complex at the southeast edge of the polygon, in Karthaus Township, on the Quehanna Highway. At this site, a Curtiss-Wright division manufactured Curon foam for furniture and household products and used beryllium oxide

Beryllium oxide (BeO), also known as beryllia, is an inorganic compound with the formula BeO. This colourless solid is an electrical insulator with a higher thermal conductivity than any other non-metal except diamond, and exceeds that of most met ...

to make high-temperature ceramic

A ceramic is any of the various hard, brittle, heat-resistant, and corrosion-resistant materials made by shaping and then firing an inorganic, nonmetallic material, such as clay, at a high temperature. Common examples are earthenware, porcela ...

s for application in the nuclear industry.Seeley, pp. 12–13.

In 1956 Curtiss-Wright began isotope work at the facility, and ''

In 1956 Curtiss-Wright began isotope work at the facility, and ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' published two stories on the new nuclear research laboratory that year, followed by a November 1957 report that the one-megawatt nuclear reactor was completed. In 1958, the corporation received a twenty-year license from the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to operate a four-megawatt open pool nuclear research reactor, and received permission from the Pennsylvania Sanitary Water Board to dispose of some radioactive waste

Radioactive waste is a type of hazardous waste that contains radioactive material. It is a result of many activities, including nuclear medicine, nuclear research, nuclear power generation, nuclear decommissioning, rare-earth mining, and nuclear ...

in Meeker Run, a tributary

A tributary, or an ''affluent'', is a stream or river that flows into a larger stream (''main stem'' or ''"parent"''), river, or a lake. A tributary does not flow directly into a sea or ocean. Tributaries, and the main stem river into which they ...

of Mosquito Creek.Stranahan, pp. 188–193, 211–212. The project was billed as "the greatest thing that ever happened in North Central Pennsylvania", and was expected to employ between 7,000 and 8,000 people. Curtiss-Wright spent $30 million on the project, and developed a community for its scientific and technical staff at the village of Pine Glen, southeast of Karthaus in Centre County.

By 1960 the Air Force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

had decided not to pursue nuclear-powered aircraft, and the federal government canceled $70 million in "high-altitude testing contracts" with Curtiss-Wright. By June 1960, the reactor was on standby and only 750 employees remained, 400 of whom were in the Curon foam division; many engineers and scientists had already left. On August 20, 1960, Curtiss-Wright announced that it was donating the reactor facility to Penn State and selling its Curon foam division; the remaining 235 employees lost their jobs. Penn State, located about an hour south of Quehanna, had its own nuclear reactor, but intended to use the Quehanna facility for research and training.

The Curtis-Wright reactor was dismantled and its fuel returned to the AEC. Martin Company, which soon became Martin Marietta

The Martin Marietta Corporation was an American company founded in 1961 through the merger of Glenn L. Martin Company and American-Marietta Corporation. In 1995, it merged with Lockheed Corporation to form Lockheed Martin.

History

Martin Marie ...

, leased the hot cells, intending to use them in the manufacture of small radioisotope thermoelectric generator

A radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG, RITEG), or radioisotope power system (RPS), is a type of nuclear battery that uses an array of thermocouples to convert the Decay heat, heat released by the decay of a suitable radioactive material i ...

s. Curtiss-Wright warned Penn State "that the radiation involved in Martin's operations would be 'extremely high' and of a type that posed a particular risk to human health", but Curtiss-Wright itself had left both solid and liquid radioactive waste in the facility. Some of the Curtiss-Wright waste was contaminated with toxic beryllium oxide. Penn State had acquired the reactor license, and with it came legal responsibility for the nuclear waste on the site; its plan with the AEC called for the release of 90 percent of the liquid radioactive waste into the environment and the burial of most radioactive solids on site. Items coated with beryllium oxide dust "were covered in plastic and buried out in the woods", where some were unearthed by black bears and white-tailed deer

The white-tailed deer (''Odocoileus virginianus''), also known Common name, commonly as the whitetail and the Virginia deer, is a medium-sized species of deer native to North America, North, Central America, Central and South America. It is the ...

.Sayers, p. 72. Once jet engine testing stopped, the bunkers at the test cells were used "to store hazardous and explosive material".

In 1962 Martin Marietta began to manufacture Systems for Nuclear Auxiliary Power

The Systems Nuclear Auxiliary POWER (SNAP) program was a program of experimental radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) and Nuclear power in space, space nuclear reactors flown during the 1960s by NASA.

The SNAP program developed as a resul ...

(SNAP) thermoelectric generators under a contract with the AEC; their AEC license allowed them to have up to 6 million curie Curie may refer to:

*Curie family, a family of distinguished scientists:

:* Jacques Curie (1856–1941), French physicist, Pierre's brother

:* Pierre Curie (1859–1906), French physicist and Nobel Prize winner, Marie's husband

:* Marie Curi ...

s of radioactive strontium-90

Strontium-90 () is a radioactive isotope of strontium produced by nuclear fission, with a half-life of 28.79 years. It undergoes β− decay into yttrium-90, with a decay energy of 0.546 MeV. Strontium-90 has applications in medicine a ...

in the form of strontium titanate

Strontium titanate is an oxide of strontium and titanium with the chemical formula strontium, Srtitanium, Tioxygen, O3. At room temperature, it is a centrosymmetric paraelectricity, paraelectric material with a Perovskite (structure), perovskite st ...

, which powered the SNAP generators. A SNAP-7 reactor made at Quehanna was used in the world's first nuclear-powered lighthouse, the Baltimore Harbor Light, from May 1964 to April 1966. In early 1963, Curtiss-Wright still owned or leased all of Quehanna and sublet land along Quehanna Highway to a firm that recovered copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

from wire by burning off its insulation, a procedure that contaminated the soil. On July 12, 1963, Governor William Scranton

William Warren Scranton (July 19, 1917 – July 28, 2013) was an American Republican Party (United States), Republican Party politician and diplomat. Scranton served as the 38th governor of Pennsylvania from 1963 to 1967, and as United States Am ...

announced the termination of Curtiss-Wright's lease on ; the state paid the company for the roads it had built, and Curtiss-Wright donated six of the eight buildings in the industrial complex to the state.Sayers, pp. 53–59. In 1965 the state legislature passed an act declaring the former leased area a wilderness area

Wilderness or wildlands (usually in the plural) are Earth's natural environments that have not been significantly modified by human activity, or any nonurbanized land not under extensive agricultural cultivation. The term has traditionally ...

, and Maurice K. Goddard, secretary of the Department of Forests and Waters, named it the Quehanna Wilderness Area.

Although Martin Marietta completed its AEC contract and its lease expired on December 21, 1966, it had to stay at the reactor site "until radiation contamination was brought to acceptable levels". Martin Marietta partially decontaminated the site, and in April 1967 undertook a joint radiological survey with Penn State and the AEC. The survey found "licensable quantities of strontium-90 stayed behind as structural contamination and residual radioactivity in piping and tanks, estimated at about 0.2 curies". This met the standards for that day, although Penn State did raise questions about the contamination remaining. Strontium

Strontium is a chemical element; it has symbol Sr and atomic number 38. An alkaline earth metal, it is a soft silver-white yellowish metallic element that is highly chemically reactive. The metal forms a dark oxide layer when it is exposed to ...

is chemically very similar to calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

(both are alkaline earth metal

The alkaline earth metals are six chemical elements in group (periodic table), group 2 of the periodic table. They are beryllium (Be), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), strontium (Sr), barium (Ba), and radium (Ra).. The elements have very similar p ...

s) and can be absorbed by the body, where it is chiefly incorporated into bones. Strontium-90 decays by beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

and has a half-life Half-life is a mathematical and scientific description of exponential or gradual decay.

Half-life, half life or halflife may also refer to:

Film

* Half-Life (film), ''Half-Life'' (film), a 2008 independent film by Jennifer Phang

* ''Half Life: ...

of 29 years; when it is in the body, its radioactivity can lead to bone cancer

A bone tumor is an neoplastic, abnormal growth of tissue in bone, traditionally classified as benign, noncancerous (benign) or malignant, cancerous (malignant). Cancerous bone tumors usually originate from a cancer in another part of the body su ...

and leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia; pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and produce high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or '' ...

.

Many in the conservation movement urged the state to buy back the land, especially after the Curtiss-Wright lease was canceled. In April 1967 Penn State vacated the site and gave the reactor complex to the state. Martin Marietta departed in June 1967, and early in that same year, Pennsylvania bought the remaining land back from Curtiss-Wright for $992,500, about $811,000 more than they had sold it for in 1955. Various usage plans for the area were proposed, including: a vacation resort with a large artificial lake, motels, golf course

A golf course is the grounds on which the sport of golf is played. It consists of a series of holes, each consisting of a teeing ground, tee box, a #Fairway and rough, fairway, the #Fairway and rough, rough and other hazard (golf), hazards, and ...

s, and honeymoon

A honeymoon is a vacation taken by newlyweds after their wedding to celebrate their marriage. Today, honeymoons are often celebrated in destinations considered exotic or romantic. In a similar context, it may also refer to the phase in a couple ...

resort; a Penn State game preserve stocked with exotic animals like bison

A bison (: bison) is a large bovine in the genus ''Bison'' (from Greek, meaning 'wild ox') within the tribe Bovini. Two extant taxon, extant and numerous extinction, extinct species are recognised.

Of the two surviving species, the American ...

and boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

; a large youth camp for several hundred children; and a radioactive waste disposal site. By November 1967, all of the land was back in the state forests and state game lands.

Protected area and reclamation

Reactor facility