Pylos (, ; ), historically also known as Navarino, is a town and a former

municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

in

Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

,

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

,

Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. Since the 2011 local government reform, it has been part of the municipality

Pylos-Nestoras, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit.

It was the capital of the former

Pylia Province. It is the main harbour on the Bay of Navarino. Nearby villages include

Gialova, Pyla, Elaiofyto, Schinolakka, and Palaionero. The town of Pylos has 2,568 inhabitants, the municipal unit of Pylos 4,559 (2021).

The municipal unit has an area of 143.911 km

2.

Pylos has been inhabited since

Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

times. It was a significant kingdom in

Mycenaean Greece

Mycenaean Greece (or the Mycenaean civilization) was the last phase of the Bronze Age in ancient Greece, spanning the period from approximately 1750 to 1050 BC.. It represents the first advanced and distinctively Greek civilization in mainla ...

, with the remains of the so-called "

Palace of Nestor" excavated nearby, named after

Nestor, the king of Pylos in

Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

''. In

Classical times, the site was uninhabited, but became the site of the

Battle of Pylos

The naval Battle of Pylos took place in 425 BC during the Peloponnesian War at the peninsula of Pylos, on the present-day Navarino Bay, Bay of Navarino in Messenia, and was an Athens, Athenian victory over Sparta. An Athenian fleet had been driv ...

in 425 BC, during the

Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

. After that, Pylos is scarcely mentioned until the 13th century, when it became part of the

Frankish Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom of Thes ...

. Increasingly known by its French name of ''Port-de-Jonc'' or its Italian name ''Navarino'', in the 1280s the Franks built the

Old Navarino castle on the site. Pylos came under the control of the

Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

from 1417 until 1500, when it was conquered by the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. The Ottomans used Pylos and its bay as a naval base, and built the

New Navarino fortress there. The area remained under Ottoman control, with the exception of a brief period of

renewed Venetian rule from 1685–1715 and a Russian occupation from 1770–71, until the outbreak of the

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

in 1821.

Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt recovered it for the Ottomans in 1825, but the defeat of the Turco-Egyptian fleet in the 1827

Battle of Navarino and the French military intervention of the 1828

Morea expedition forced Ibrahim to withdraw from the Peloponnese and confirmed Greek independence. The current city was built outside the fortress walls by the military engineers of the Morea expedition from 1829 and the name ''Pylos'' was

revived by royal decree in 1833.

Name

Pylos retained its ancient name into Byzantine times, but after the

Frankish conquest in the early 13th century, two new names appear:

* a French one, ("

Rush Harbour") or , with some variants and derivatives: in Italian , or , in medieval Catalan , in Latin , ( or ) in Greek, etc. It takes that name from the marshes surrounding the place.

* a Greek one, (), later shortened to () or lengthened to () by

epenthesis

In phonology, epenthesis (; Greek ) means the addition of one or more sounds to a word, especially in the first syllable ('' prothesis''), the last syllable ('' paragoge''), or between two syllabic sounds in a word. The opposite process in whi ...

, which became in Italian (probably by

rebracketing

Rebracketing (also known as resegmentation or metanalysis) is a process in historical linguistics where a word originally derived from one set of morphemes is broken down or bracketed into a different set. For example, '' hamburger'', originally ...

) and in French.

Its etymology is not certain. A traditional etymology, proposed by the early 15th-century traveller

Nompar de Caumont and repeated as late as the works of

Karl Hopf in the 19th century, ascribed the name to the

Navarrese Company, but that is clearly an error since the name was in use long before the Navarrese presence in Greece. In 1830,

Fallmereyer proposed that it could originate from a body of

Avars who settled there, a view adopted by a few later scholars like

William Miller. Modern scholarship, on the other hand, considers it more likely that it originates from a

Slavic name meaning "place of

maple

''Acer'' is a genus of trees and shrubs commonly known as maples. The genus is placed in the soapberry family Sapindaceae.Stevens, P. F. (2001 onwards). Angiosperm Phylogeny Website. Version 9, June 2008 nd more or less continuously updated si ...

s".

The name of /, although in use before the Frankish period, came into widespread use and eclipsed the French name of and its derivations only in the 15th century, after the collapse of the Frankish

Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom of Thes ...

.

In the late 14th or early 15th century, when it was held by the

Navarrese Company, it was also known as , and called (, "village of the Spaniards") by the local Greeks.

Under

Ottoman rule (1498–1685, 1715–1821), the Turkish name was (). After the construction of the new Ottoman fortress () in 1571/2, it became known as ( or , "new castle") among the local Greeks, while the old Frankish castle became known as ( or , "old castle").

History

Neolithic Pylos

The region of Pylos has a long history, which goes hand in hand with that of Peloponnese. It starts in the depths of prehistory, as the region has been inhabited since the

Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

, when populations from

Anatolia

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

began to spread in the Balkans and Greece around 6500 BC, bringing with them the practice of agriculture and farming. Excavations have demonstrated a continuous human presence from the Late Neolithic period (5300 BC) on several sites of

Pylia, in particular in those of

''Voidokilia'' and of ''Nestor's'' ''cave'', where numerous

ostraca

An ostracon (Greek language, Greek: ''ostrakon'', plural ''ostraka'') is a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In an archaeology, archaeological or epigraphy, epigraphical context, ''ostraca'' refer ...

or fragments of painted, black and polished ceramics have been found, as well as later engraved and written pottery. The Neolithic period ended with the appearance of

bronze metallurgy around 3000 BC.

Mycenaean Pylos

During the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

(3000–1000 BC), the

Mycenaean civilization developed, particularly in Peloponnese. Pylos then became the capital of one of the most important human centers of this civilization and of a powerful kingdom, often referred to as

Nestor's kingdom of "sandy Pylos" (''ἠμαθόεις'') and described later by

Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

in both his ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'' and his ''

Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'' (Book 17) when

Telemachus says:

The Mycenaean state of Pylos (1600–1200 BC) covered an area of and had a minimum population of 50,000 according to the

Linear B

Linear B is a syllabary, syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest Attested language, attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examp ...

tablets discovered there, or even perhaps as large as 80,000–120,000.

[ Jack L. Davis, ''Sandy Pylos: An Archaeological History from Nestor to Navarino'', University of Texas Press 1998; Greek Translation 2004; second edition 2007). With S.E. Alcock, J. Bennet, Y. Lolos, C. Shelmerdine, and E. Zangger.] It should not however be confused with the current city of Pylos. The urban center of ancient Pylos indeed remains only partially identified to date. The various archaeological remains of palaces and administrative or residential infrastructures that have been found in the region so far suggest to modern scholars that the ancient city would have developed over a much larger area, that of the

Pylia Province.

The typical point of reference for the Mycenaean city remains the

Palace of Nestor, but many other palaces (such as those of

Nichoria

Nichoria () is a site in Messenia, on a ridgetop near modern Rizomylos, at the northwestern corner of the Messenian Gulf. From the Middle to Late Bronze Age it cultivated olive and terebinth for export.Palaima (2000), p. 17. During the Helladic ...

and

Iklaina) or villages (such as Malthi) of the Mycenaean era have been recently discovered, which were quickly subordinated to Pylos.

Its

port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

and its

acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

were probably established on the ''Koryphasion'' promontory (or ''Cape Coryphasium'') commanding the northern entrance to the bay, 4 km north of the modern city and south of Nestor's palace, but no remains were found.

The Pylos site is located on the hill of Ano Englianos, about 9 km northeast of the bay , near the village of

Chora

Chora may refer to:

Places Greece

* Chora, old capital of the island of Alonnisos

* Chora, village on the island of Folegandros

* Chora, Ios, capital of the island of Ios

* Chora, Messenia, a small town in Messenia in the Peloponnese

* Chora, p ...

and about 17 kilometres from the modern city of Pylos. It hosts one of the most important Mycenaean palaces in Greece, known as the great "

Palace of Nestor" described in the Homeric poems. This palace remains today the best preserved palace in Greece and one of the most important of all Mycenaean civilization. It was discovered and first excavated in 1939 by American archaeologist

Carl Blegen

Carl William Blegen (January 27, 1887 – August 24, 1971) was an American archaeologist who worked at the site of Pylos in Greece and Troy in modern-day Turkey. He directed the University of Cincinnati excavations of the mound of Hisarlik, th ...

(1887–1971) of the

University of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati, informally Cincy) is a public university, public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1819 and had an enrollment of over 53,000 students in 2024, making it the ...

and the

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, and by

Konstantinos Kourouniotis (1872–1945) of the Greek archaeological service. Their excavations were interrupted by the Second World War, and then resumed in 1952 under the direction of Blegen until 1966. He found many architectural elements such as the throne room with its foyer, an anteroom, rooms and passageways all covered with

fresco

Fresco ( or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting become ...

es of Minoan inspiration, and also large warehouses, the external walls of the palace, unique baths, galleries, and 90 meters outside the palace, a

beehive "tholos" tomb, perfectly restored in 1957 (''Tholos tomb IV'').

In addition to the archaeological remains of the palace, Blegen also found there thousands of clay tablets with inscriptions written in

Linear B

Linear B is a syllabary, syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest Attested language, attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examp ...

, a

syllabic script used between 1425 and 1200 BC for writing

Mycenaean Greek

Mycenaean Greek is the earliest attested form of the Greek language. It was spoken on the Greek mainland and Crete in Mycenaean Greece (16th to 12th centuries BC). The language is preserved in inscriptions in Linear B, a script first atteste ...

. Pylos is the largest source in Greece of these tablets with 1,087 fragments found on the site of the Nestor's Palace. In 1952, when self-taught linguist

Michael Ventris

Michael George Francis Ventris, (; 12 July 1922 – 6 September 1956) was an English architect, classics, classicist and philology, philologist who deciphered Linear B, the ancient Mycenaean Greek script. A student of languages, Ventris had ...

and

John Chadwick

John Chadwick, (21 May 1920 – 24 November 1998) was an English linguist and classical scholar who was most notable for the decipherment, with Michael Ventris, of Linear B.

Early life, education and wartime service

John Chadwick was born at ...

deciphered the script, Mycenaean Greek turned out to be the earliest

attested form of

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, some elements of which have survived in the language of Homer thanks to a long oral tradition of epic poetry. Thus, these clay tablets, generally used for administrative purposes or for recording economic transactions, clearly demonstrate that the site itself was already called "Pylos" by its Mycenaean inhabitants (''Pulos'' in Mycenaean Greek; attested in Linear B as

''pu-ro,'' ).

In 2015, the team of American archaeologists

Sharon Stocker and

Jack L. Davis of the

University of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati, informally Cincy) is a public university, public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1819 and had an enrollment of over 53,000 students in 2024, making it the ...

and under the aegis of the

American School of Classical Studies at Athens, discovered near the ''Tholos tomb IV'', a

shaft tomb (non-tholos) dated to the

Late Helladic IIA (LHIIA, 1600–1470 BC), of an individual of 30–35 years old and 1.70 m tall, the "Griffin warrior", named for the mythological creature, part eagle, part lion, engraved on an ivory plaque in his tomb. The tomb also contained armor, weapons, mirror and many pearl and gold jewels, including several gold signet rings of exceptional craftsmanship and thoroughness. Researchers believe it could be the grave of a

Wanax, a tribal king, lord or military leader during the Mycenaean era. It was also in this tomb that was found the

Pylos Combat Agate, a seal made of

agate dated from around 1450 BCE, which represents a warrior engaged in a hand-to-hand combat.

In 2017, the same team discovered two other exceptional tholos tombs, ''Tholos tombs VI and VII''. Although their domes had collapsed, they discovered that they were littered with flakes of gold leaf that once papered the walls and found a multitude of cultural artifacts and delicate jewelry, including a gold pendant representing the head of the Egyptian goddess

Hathor

Hathor (, , , Meroitic language, Meroitic: ') was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god R ...

, which showed for the first time that Pylos clearly had trade relations with Egypt and the Middle East around 1500 BCE.

[Rory Sullivan and Elinda Labropoulou]

Archaeologists uncover treasure-filled 'princely' tombs in Greece

, cnn.com, 18 December 2019.[Archaeologists find Bronze Age tombs lined with gold](_blank)

, heritagedaily.com, 18 December 2019.

Pylos was the only palace of that time to have no walls or fortifications. It was destroyed by fire around 1180 BC and many clay tablets in linear B clearly bear the stigmata of the fire. The Linear B archives found there, preserved by the heat of the fire that destroyed the palace, mention hasty defence preparations due to an imminent attack without giving any detail about the attacking force. The site of the Mycenaean Pylos then seems to have been abandoned during the

Dark Ages (1100–800 BC). The region of Pylos, together with that of the

ancient Messene, was later enslaved by

Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

.

The ruins of a crude stone fortress on nearby

Sphacteria, apparently of Mycenaean origin, were used by the

Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

ns during the

Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

. (Thucydides iv. 31)

Classical Pylos

It was one of the last places which held out against the Spartans in the

Second Messenian War, after which the inhabitants emigrated to

Cyllene, and from there, with the other

Messenians, to

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

. Its name is mentioned again in the seventh year of the Peloponnesian War. According to the Greek historian

Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

in his ''

History of the Peloponnesian War

The ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' () is a historical account of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), which was fought between the Peloponnesian League (led by Sparta) and the Delian League (led by Classical Athens, Athens). The account, ...

'', the area was "together with most of the country round, unpopulated". The ancient city was not located at the modern Pylos, but north of the isle of

Sphacteria. In 425 BC the

Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

politician

Cleon sent an expedition to Pylos where the Athenians fortified the rocky promontory now known as Koryphasion (Κορυφάσιον) or

Old Pylos at the northern edge of the bay, near the

Gialova Lagoon, and after a conflict with Spartan ships in the

Battle of Pylos

The naval Battle of Pylos took place in 425 BC during the Peloponnesian War at the peninsula of Pylos, on the present-day Navarino Bay, Bay of Navarino in Messenia, and was an Athens, Athenian victory over Sparta. An Athenian fleet had been driv ...

, seized and occupied the bay.

Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

, the Athenian commander, completed the fort in 424 BC.

The erection of this fort led to one of the most memorable events in the Peloponnesian War. Thucydides has given a minute account of the topography of the district, which, though clear and consistent with itself, does not coincide, in all points, with the existing locality, Thucydides describes the harbour, of which the promontory Coryphasium (''Koryphasion'') formed the northern termination, as fronted and protected by the island Sphacteria, which stretched along the coast, leaving only two narrow entrances to the harbour,--the one at the northern end, opposite to Coryphasium, being only wide enough to admit two triremes abreast, and the other at the southern end wide enough for eight or nine triremes. The island was about 15 stadia in width, covered with wood, uninhabited and untrodden.

Pausanias also says that the island Sphacteria lies before the harbour of Pylos like Rheneia before the anchorage of Delos. A little later the Athenians captured a number of Spartan troops besieged on the adjacent island of Sphacteria (see

Battle of Sphacteria). Spartan anxiety over the return of the prisoners, who were taken to Athens as hostages, contributed to their acceptance of the

Peace of Nicias in 421 BC.

Middle Ages

Little is known of Pylos under

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

rule, except for a mention of raids by

Cretan Saracens in the area c. 872/3.

In the 12th century, the Muslim geographer

al-Idrisi mentioned it as the "commodious port" of ''Irūda'' in his ''Nuzhat al-Mushtaq''.

In 1204, following the

Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

, the Peloponnese became the

Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom of Thes ...

, a

Crusader state. Pylos fell quickly to the Crusaders according to a brief reference in the ''

Chronicle of the Morea'', but it is not until the 1280s that it is mentioned again. According to the French and Greek versions of the ''Chronicle'',

Nicholas II of Saint Omer, the lord of

Thebes, who in c. 1281 received extensive lands in Messenia in exchange for his wife's possessions of

Kalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

and

Chlemoutsi, erected a

castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

at Navarino. According to the Greek version, he intended this as a future fief for his nephew,

Nicholas III, although the Aragonese version attributes the construction to Nicholas III himself, a few years later. According to A. Bon, a construction under Nicholas II in the 1280s is more likely, possibly in the period 1287–89 when he served as the viceroy () of Achaea.

Despite Nicholas II's intentions, however, it is unclear whether his nephew did indeed inherit Navarino. If he did, it remained his until his death in 1317, when it and all the Messenian lands of the family reverted to the princely domain, as Nicholas III had no children.

The fortress remained relatively unimportant thereafter, except for the

naval battle in 1354 between

Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

and

Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

,

and an episode in 1364, during the conflict between

Mary of Bourbon and the Prince

Philip of Taranto, due to Mary's attempt to claim the Principality following the death of her husband,

Robert of Taranto

Robert II of Taranto (1319 or early winter 1326 – 10 September 1364), of the Capetian House of Anjou, Angevin family, Principality of Taranto, Prince of Taranto (1331–1346), Kingdom of Albania (medieval), King of Albania (1331–1332), ...

. Mary had been given possession of Navarino (along with Kalamata and

Mani

Mani may refer to:

People

* Mani (name), (), a given name and surname (including a list of people with the name)

** Mani (prophet) (c. 216–274), a 3rd century Iranian prophet who founded Manichaeism

** Mani (musician) (born 1962), an English ...

) by Robert in 1358, and the local

castellan

A castellan, or constable, was the governor of a castle in medieval Europe. Its surrounding territory was referred to as the castellany. The word stems from . A castellan was almost always male, but could occasionally be female, as when, in 1 ...

, loyal to Mary, briefly imprisoned the new Prince's , Simon del Poggio. Mary retained control of Navarino until her death in 1377. At about this time,

Albanians

The Albanians are an ethnic group native to the Balkan Peninsula who share a common Albanian ancestry, Albanian culture, culture, Albanian history, history and Albanian language, language. They are the main ethnic group of Albania and Kosovo, ...

settled in the area, while in 1381/2, Navarrese, Gascon and Italian mercenaries were active there.

From the early years of the 15th century, Venice set its eyes on the fortress of Navarino, fearing lest its rivals the Genoese seize it and use it as a base for attacks against the Venetian outposts of

Modon and

Coron. In the event, the Venetians seized the fortress themselves in 1417 and, after prolonged diplomatic manoeuvring, succeeded in legitimizing their new possession in 1423.

First Venetian and first Ottoman periods

In 1423, Navarino, like the rest of the Peloponnese, suffered its first Ottoman raid, led by

Turakhan Bey, which was repeated in 1452.

It was also at Navarino that Emperor

John VIII Palaiologos embarked in 1437, heading for the

Council of Ferrara, and where the last

Despot of the Morea,

Thomas Palaiologos, embarked with his family in 1460, following the Ottoman conquest of the Despotate of the Morea.

After 1460, the fortress, along with the other Venetian outposts and

Monemvasia

Monemvasia (, or ) is a town and municipality in Laconia, Greece. The town is located in mainland Greece on a tied island off the east coast of the Peloponnese, surrounded by the Myrtoan Sea. Monemvasia is connected to the rest of the mainland by a ...

and the

Mani Peninsula, were the only Christian-held areas in the peninsula.

Venetian control over Navarino survived the

First Ottoman–Venetian War (1463–79), but not the

Second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

(1499–1503): following the Venetian defeat in the

Battle of Modon in August 1500, the 3,000-strong garrison surrendered, although it was well provisioned for a siege. The Venetians recaptured it shortly after, on 3/4 December, but on 20 May 1501, a joint Ottoman land and sea attack under

Kemal Reis and

Hadım Ali Pasha retook it.

The Ottomans used Navarino (which they called or ) as a naval base, either for piratical raids or for major fleet operations in the Ionian and Adriatic seas.

In 1572/3, the Ottoman chief admiral (

Kapudan Pasha

The Kapudan Pasha (, modern Turkish: ), also known as the (, modern: , "Captain of the Sea") was the grand admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Typically, he was based at Galata and Gallipoli during the winter and charged with annual sailings durin ...

)

Uluç Ali Reis built a

new fortress at Navarino (, "New Navarino", or , in Greek), to replace the outdated Frankish castle.

The Venetians briefly captured Navarino in the 1650s during the

Cretan War.

In 1668,

Evliya Çelebi described the city in his ''

Seyahatname'':

Anavarin-i Atik is an unequalled castle... the harbor is a safe anchorage...

in most streets of Anavarin-i Cedid there are many fountains of running water... The city is embellished with trees and vines so that the sun does not beat into the fine marketplace at all, and

all the city notables sit here, playing backgammon, chess, various kinds of draughts, and other board games....

Second Venetian period and Ottoman reconquest

In 1685, during the early stages of the

Morean War

The Morean war (), also known as the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War, was fought between 1684–1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the "Great Turkish War", between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Military operations ranged ...

, the Venetians under

Francesco Morosini and

Otto Wilhelm Königsmarck invaded the Peloponnese and captured most of it, successfully storming the two fortresses of Navarino in the process. With the peninsula safely in Venetian hands, Navarino became an administrative centre in the new "

Kingdom of the Morea

The Kingdom of the Morea or Realm of the Morea (; ; ) was the official name the Republic of Venice gave to the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece (which was more widely known as the Morea until the 19th century) when it was conquered from ...

", as the Venetian province was called, until 1715, when the Ottomans

recovered the Peloponnese.

The Venetian census of 1689 gave the population as 1,413, while twenty years later it had risen to 1,797 inhabitants.

After the Ottoman reconquest, Navarino became the centre of a ''

kaza

A kaza (, "judgment" or "jurisdiction") was an administrative divisions of the Ottoman Empire, administrative division of the Ottoman Empire. It is also discussed in English under the names district, subdistrict, and juridical district. Kazas co ...

'' in the

Sanjak of the Morea.

On 10 April 1770, after a six-day siege, the fortress of New Navarino surrendered to the Russians during the

Orlov Revolt. The Ottoman garrison was allowed to depart for Crete, while the Russians repaired the fortress to make it their base. On 1 June, however, the Russians left, and the Ottomans re-entered the fort and burned and partially demolished it.

Meanwhile, the population gathered there had escaped to nearby Sphacteria, where Albanian mercenaries of the Ottomans slaughtered most of them.

The Greek War of Independence of 1821

After the outbreak of the

Greek War of Independence

The Greek War of Independence, also known as the Greek Revolution or the Greek Revolution of 1821, was a successful war of independence by Greek revolutionaries against the Ottoman Empire between 1821 and 1829. In 1826, the Greeks were assisted ...

against the Ottoman occupation in mid-March 1821, the Greeks quickly won many victories and proclaimed their independence on 1 January 1822. Navarino was besieged by the local Greeks on 29 March. The garrison, augmented by the local Muslim population of

Kyparissia

Kyparissia () is a town and a former municipality in northwestern Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. The municipal unit has ...

, held out until the first week of August, when they were forced to capitulate. Despite their promise for safe conduct, the Greeks

massacred them all.

The Greek victories was short lived. The Sultan called for aid from his Egyptian vassal

Muhammad Ali

Muhammad Ali (; born Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr.; January 17, 1942 – June 3, 2016) was an American professional boxer and social activist. A global cultural icon, widely known by the nickname "The Greatest", he is often regarded as the gr ...

, who dispatched his son

Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt to Greece with a fleet and 8,000 men, and later added 25,000 troops.

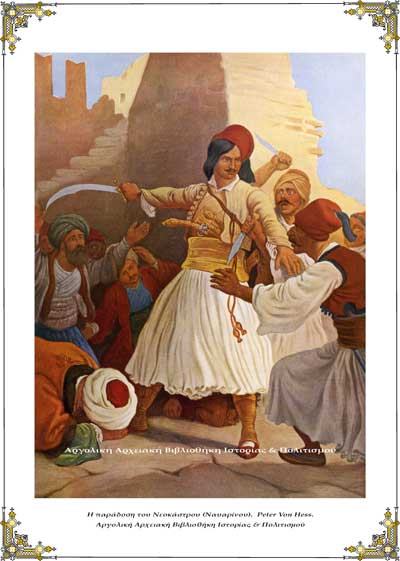

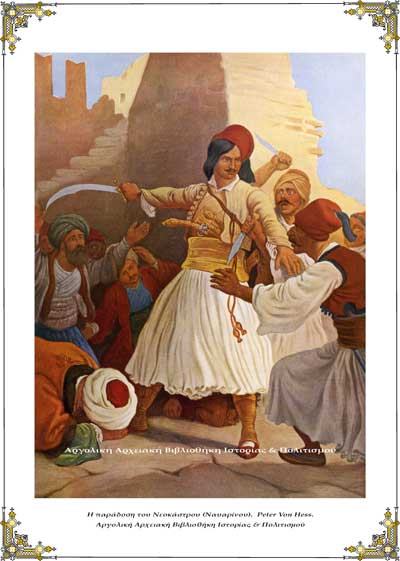

[''An Index of events in the military history of the Greek nation.'', Hellenic Army General Staff, Army History Directorate, Athens, 1998, pp. 51 and 54. ] Ibrahim's intervention proved decisive: the region of Pylos fell on 18 May 1825 after the battles of

Sphacteria (8 May) and

Neokastro (11 May), much of the

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

was reconquered in 1825; the gateway town of

Messolonghi fell in 1826; and Athens was taken in 1827. The only territory still held by Greek nationalists was in

Nafplion,

Mani

Mani may refer to:

People

* Mani (name), (), a given name and surname (including a list of people with the name)

** Mani (prophet) (c. 216–274), a 3rd century Iranian prophet who founded Manichaeism

** Mani (musician) (born 1962), an English ...

,

Hydra,

Spetses and

Aegina

Aegina (; ; ) is one of the Saronic Islands of Greece in the Saronic Gulf, from Athens. Tradition derives the name from Aegina (mythology), Aegina, the mother of the mythological hero Aeacus, who was born on the island and became its king.

...

.

[C. M. Woodhouse, ''The Philhellenes'', London, Hodder et Stoughton, 1969, 192 p.]

The Naval Battle of Navarino (20 October 1827)

A strong current of

philhellenism had developed in Western Europe, especially after the fall in 1826 of Missolonghi, where the poet

Lord Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

had died in 1824. Many artists and intellectuals like

Chateaubriand,

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

,

Alexander Pushkin

Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin () was a Russian poet, playwright, and novelist of the Romantic era.Basker, Michael. Pushkin and Romanticism. In Ferber, Michael, ed., ''A Companion to European Romanticism''. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005. He is consid ...

,

Gioachino Rossini

Gioachino Antonio Rossini (29 February 1792 – 13 November 1868) was an Italian composer of the late Classical period (music), Classical and early Romantic music, Romantic eras. He gained fame for his 39 operas, although he also wrote man ...

,

Hector Berlioz

Louis-Hector Berlioz (11 December 1803 – 8 March 1869) was a French Romantic music, Romantic composer and conductor. His output includes orchestral works such as the ''Symphonie fantastique'' and ''Harold en Italie, Harold in Italy'' ...

or

Eugène Delacroix

Ferdinand Victor Eugène Delacroix ( ; ; 26 April 1798 – 13 August 1863) was a French people, French Romanticism, Romantic artist who was regarded as the leader of the French Romantic school.Noon, Patrick, et al., ''Crossing the Channel: ...

(in his paintings ''Scenes massacres of Scio'' in 1824, and ''Greece on the ruins of Missolonghi'' in 1826), amplified the current of sympathy for the Greek cause in the public opinion. By the

Treaty of London of July 1827, France, Russia and the United Kingdom recognised the autonomy of Greece, which remained a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The three powers agreed to a limited intervention in order to convince the

Porte to accept the terms of the convention. A plan to send a naval expedition as a demonstration of force was proposed and adopted; subsequently a fleet of 27 warships of the allied navies of

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

was sent to exert diplomatic pressure against Constantinople.

It included twelve British ships (for 456 guns), seven French ships (352 guns) and eight Russian ships (490 guns), for a total firepower of nearly 1,300 guns. The

Battle of Navarino (20 October 1827) resulted in the total destruction of the combined Ottoman–Egyptian fleet (around 60 warships destroyed).

An obelisk-shaped memorial dedicated to the victory of the Allied fleets and their three admirals, the British

Edward Codrington, the French

Henri de Rigny and the Russian

Lodewijk van Heiden

Lodewijk Sigismund Vincent Gustaaf Reichsgraf van Heiden (; ; 6 September 1773 – 17 October 1850) was a Dutch naval officer and Orangism (Dutch Republic), Orangist who went into exile from the Batavian Republic and served in the Russian N ...

was later erected on the central square of Pylos. The monument was the work of the sculptor Thomas Thomopoulos (1873–1937) and its unveiling took place in 1930, although it was completed in 1933.

The liberation of Pylos (6 October 1828) and the construction of the modern city

On 6 October 1828, Pylos was definitively liberated from the Ottoman–Egyptian troops of Ibrahim Pasha by the French troops of the

Morea expedition commanded by

Marshal Nicolas-Joseph Maison.

[ Marshal Nicolas-Joseph Maison, ''Dépêches adressées au ministre de la Guerre Louis-Victor de Caux, vicomte de Blacquetot'', octobre 1828, in Jacques Mangeart, Supplemental Chapter of the ]

Souvenirs de la Morée: recueillis pendant le séjour des Français dans le Péloponèse

'', Igonette, Paris, 1830. The mission of this expeditionary corps of 15,000 men, sent by king

Charles X of France

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother of reigning kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported th ...

to the Peloponnese between 1828 and 1833, was to implement the Treaty London of 1827, an agreement under which the Greeks would have the right to an independent state. The French troops liberated the cities of Navarino (Pylos), Modon (

Methoni), Coron (

Koroni) and

Patras

Patras (; ; Katharevousa and ; ) is Greece's List of cities in Greece, third-largest city and the regional capital and largest city of Western Greece, in the northern Peloponnese, west of Athens. The city is built at the foot of Mount Panachaiko ...

in October 1828.

The current city of Pylos was built starting in the spring of 1829, outside the walls of Neokastro, on the model of the

bastides of Southwest France and the cities of the

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

(which share common features, such as a central geometrical square bordered by covered galleries built with a succession of contiguous

arch

An arch is a curved vertical structure spanning an open space underneath it. Arches may support the load above them, or they may perform a purely decorative role. As a decorative element, the arch dates back to the 4th millennium BC, but stru ...

es, each supported by a

colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

, as the

arcades of Pylos or

Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

).

[ Kalogerakou Pigi P. (''Καλογεράκου Πηγή Π.''), ''The contribution of the French expeditionary force to the restoration of the fortresses and the cities of Messinia'' (]

Η συμβολή του Γαλλικού εκστρατευτικού σώματος στην αποκατάσταση των φρουρίων και των πόλεων της Μεσσηνίας

)'', in Οι πολιτικοστρατιωτικές σχέσεις Ελλάδας – Γαλλίας (19ος – 20ός αι.), Directorate of the Army History (''Διεύθυνση Ιστορίας Στρατού''), 13–41, Athens, 2011. Pylos's urban framework was designed by

Joseph-Victor Audoy, lieutenant-colonel of the

military engineering

Military engineering is loosely defined as the art, science, and practice of designing and building military works and maintaining lines of military transport and military communications. Military engineers are also responsible for logistics b ...

of the Morea expedition, who originated from

Tarn, a department of Southwest France. This plan was approved by the governor of independent Greece

Ioannis Kapodistrias

Count Ioannis Antonios Kapodistrias (; February 1776 –27 September 1831), sometimes anglicized as John Capodistrias, was a Greek statesman who was one of the most distinguished politicians and diplomats of 19th-century Europe.

Kapodistrias's ...

on 15 January 1831, making it the second urban plan (after that of Methoni) in the history of the modern Greek state. The fortifications of ''Neokastro'' were raised, a barracks was built (the "Maison's building" which houses nowadays the Archaeological Museum of Pylos), many improvements were made to the city (installation of school, hospital, church, postal service, shops, bridges, squares, fountains, gardens, etc.), the old Ottoman aqueduct, which had fallen into ruins until 1828, was restored (it then served until 1907), and the road between Navarin and Modon, the first road of independent Greece (which is still used today), was also built by the French engineers.

Part of the Morea expedition were also 19 scientists from the "Morea Scientific Mission",

[ Jean-Baptiste Bory de Saint-Vincent, ]

Relation de l'Expédition scientifique de Morée: Section des sciences physiques

'', F.-G. Levrault, Paris, 1836. whose work proved essential to the ongoing development of the

new Greek State and, more broadly, marked a major milestone in the modern history of archaeology, cartography and natural sciences, as well as in the study of Greece. According to one of their population censuses in the province of Navarino in 1829, it had a total of 1,596 inhabitants.

Some French merchants and officers of the Morea expedition, who remained in the city with their families after the troops returned to France in 1833, settled in a district located in the north of the city, near a Catholic church that has since been demolished. This district is still called today "Francomahalas" (in

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: Φραγκομαχαλάς, from

Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

: محلة (''

mahallah

is an Arabic word variously translated as district, Quarter (country subdivision), quarter, Ward (country subdivision), ward, or neighborhood in many parts of the Arab world, the Balkans, Western Asia, the Indian subcontinent, and nearby nations.

...

''), district) or "Francoklisa" (in

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: Φραγκοκλησά, church of the French).

The French always had a particular interest in the city, and at that time, the greatest French writers wrote texts specifically dedicated to Pylos, such as

François-René de Chateaubriand

François-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand (4 September 1768 – 4 July 1848) was a French writer, politician, diplomat and historian who influenced French literature of the nineteenth century. Descended from an old aristocratic family from Bri ...

in 1806,

Eugène Sue

Marie-Joseph "Eugène" Sue (; 26 January 18043 August 1857) was a French novelist. He was one of several authors who popularized the genre of the serial novel in France with his very popular and widely imitated '' The Mysteries of Paris'', whi ...

and

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

in 1827,

Edgar Quinet in 1830

[Edgar Quinet (member of the scientific commission of the Morea expedition), ]

De la Grèce moderne, et de ses rapports avec l'antiquité.

'', F.-G. Levrault, Paris, 1830. and

Alphonse de Lamartine in 1832.

In 1833, after the departure of the French, the name "Pylos" (in reference to the ancient city of King Nestor) was given to the new city of Navarino by royal decree of the newly installed king

Otto I of Greece.

20th century

The fortress of Pylos was transformed into a place of deportation of political opponents during the

totalitarian regime of Metaxas between 1936 and 1941. Administratively, Pylos was the seat of the Municipality of Pylos between 1912 and 1946, then became the seat of the Deme of Pylos between 1946 and 2010. Since the 2011 reform, Pylos has been the seat of the new Municipality of

Pylos-Nestor

Pylos-Nestoras () is a municipality in the Messenia regional unit, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Pylos. The municipality has an area of 554.265 km2.

Municipality

The municipality Pylos-Nestora ...

.

Geography

Site

The city of Pylos is located at the foot of a promontory which extends Mount Aghios Nikolaos (482 m) and carries the fortress. It is located at the south-western end of

Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

, on the

Ionian coast. It is an important shipping center and, in recent years, it has experienced significant tourist development, exploiting its magnificent coastline. The narrow

island of Sphacteria serves as a natural breakwater for Navarino Bay, making the port of Pylos one of the safest anchors of the Ionian coast.

Communication

Pylos has excellent roads and all the communication amenities of a modern city.

Greek National Road 82 departs from the center of Pylos and connects directly to

Kalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

in less than an hour, and from there to

Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

in two hours.

Kalamata International Airport (KLX, Captain Vassilis C. Constantakopoulos Airport), which is expanding rapidly, offers many scheduled flights to the major cities of Greece, and many charter flights during the touristic season from many international destinations.

Population

According to the census of 2021, the municipality (deme) of Pylos-Nestor has 17,194 inhabitants. The municipal unit of Pylos has 4,559 inhabitants, while the community of Pylos has 2,568 inhabitants, making it the seventh most populous city in

Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

, after the capital

Kalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

(58,816),

Messini (5,958),

Kyparissia

Kyparissia () is a town and a former municipality in northwestern Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is the seat and a municipal unit. The municipal unit has ...

(5,763),

Filiatra

Filiatra (), is a town and a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is a muni ...

(4,729),

Gargalianoi

Gargalianoi () is a town and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Trifylia, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area of 122.680 ...

(4,724) and

Chora

Chora may refer to:

Places Greece

* Chora, old capital of the island of Alonnisos

* Chora, village on the island of Folegandros

* Chora, Ios, capital of the island of Ios

* Chora, Messenia, a small town in Messenia in the Peloponnese

* Chora, p ...

(2,609).

Urban landscape

Navarino castles

The city of Pylos has two castles (''Kastra''): the Frankish ''Paleokastro'' (old castle) and the Ottoman ''Neokastro'' (new castle). The first is located northwest of Navarino Bay and north of the

island of Sphacteria, while the second is southwest of the bay, on the heights of the city of Pylos. The ''Paleokastro'', located on the top of the promontory of Coryphasium ''(Koryphasion)'' (which is in geological continuity with the island of Sphacteria from which it is only separated by the narrow pass of ''Sykia''), is built on the site of the ancient acropolis of Pylos. It offers a panoramic view, stretching from the

Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

to the Plain of

Pylia. Below is Nestor's cave, where, according to mythology, the king of Pylos raised his oxen, and the

bay of Voidokilia, whose beach is regularly ranked among the most beautiful in the world.

The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

,

'My favourite beach in the world'

'' – readers' tips, Thursday 11 February 2016.The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

,

20 last-minute holidays to empty European beaches

'', by Chris Leadbeater, 9 April 2019. It borders the

Gialova lagoon (''Osman-aga lake''), located to the east and Navarino bay to the south. However, access to the ''Paleokastro'' may present some risks for the safety of visitors, due to its great deterioration. On the other side of the Navarino bay, the ''Neokastro'', which is in a better state of conservation, looks out onto the island of Sphacteria, the bay of Navarino, and the city. It is one of the best preserved castles in Greece. It contains within its walls the well-preserved ''Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior'', built by the Franks, later transformed into a mosque, then again into a Christian church. In the pine forest of the ''Neokastro'' is also the old barracks built by the French troops of the Morea expedition, which now houses th

new archaeological museum of Pylos

Navarino aqueduct

South of the city of Pylos, on the road to Methoni, is the old Navarino

aqueduct, built in the 16th century by the Ottomans to meet the water supply needs of the ''Neokastro''. Composed by two hydraulic systems, it led the waters from the water intakes of the ''plateau of Koumbeh'' (located near the town of Chandrinou about 15 kilometers northeast of Pylos on the road to Kalamata) and ''Paleo Nero'' (located near the village of Palaionero). The two systems combined into a single system that can still be seen today around Pylos in the district of ''Kamares''. Then, thanks to an underground conduit of the aqueduct, the water penetrated inside the fortress to feed there the fountains of the ''Neokastro''.' Fallen into ruins until 1828, it was restored in 1832 by the French engineers of the Morea expedition, and was used to supply Pylos with water until 1907.

Pylos city center

Leaning against two hills, one of which is overlooked by the fortress of the ''Neokastro,'' the town of Pylos faces the bay of Navarino. Pylos preserves many houses from the 19th century. These are built of stone, with typical

Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

n architecture and surrounded by spacious courtyards and gardens. They are built mainly between narrow streets, generally symmetrical, and according to the original urban plan established by French military engineers of the

Morea expedition at the beginning of the 19th century.

Many of the streets have retained their original stone paving, and several of those which climb the hills, are pedestrianized and have steps.

Near the seafront is the

central city square, the Square of the Three Admirals, surrounded by buildings whose ground floor houses, most often under

arcade galleries, markets, bakeries, shops and traditional cafes. The seaside, to the north-west of the city, follows a recently

pedestrianized street which leads from the central square to the

modern port, passing through the ''Francomahalas'' district. In this street, aligned along the old port, are several traditional

fish taverns. The port is dominated by the

City Hall of Pylos. Next to it is recently renovated two-story house of the

Olympic champion Kostis Tsiklitiras, in which a museum has been installed, which exposes a collection of paintings, engravings and ancient documents collected by the French philhellene, historian and writer

René Puaux (1878–1936). A little further, still following the seaside, is the historic building of the College of Pylos which was founded in September 1921 by royal decree and built in 1924.

The Historical College of Pylos (1921–1987)

(Ιστορικό Γυμνάσιο Πύλου)'', Archaiologia.gr, 4 June 2020. In Greek. After the cessation of its activities in 1987, the building housed until very recently the Institute of Physical Astrophysics "Nestor" of the National Observatory of Greece. The institute is in charge of the international research project NESTOR and its

underwater neutrino detector, which is installed more than 4,000 meters deep, in the deepest

marine trench of the Mediterranean Sea, 31 km off Pylos. In September 1992, the historic building of the College of Pylos was classified by the Ministry of Culture as a ''Preserved Historic Monument

'' and will house soon in the near future the public library and gallery of the municipality of Pylos.

The city also has bank branches, a post office, various clinics, a health center, a fire station, a sailing school, nurseries, primary schools, a college, a high school and a music conservatory recognized by the State. The city is also home to several cultural and development associations.

The central square of the Three Admirals

Also built by French troops of the

Morea expedition in 1829, the central square of Pylos is characterized by its triangular geometric pattern, one of the sides of which opens onto the sea and the port of Pylos, and whose two other sides are bordered by covered galleries with

arcades, built with a succession of contiguous

arch

An arch is a curved vertical structure spanning an open space underneath it. Arches may support the load above them, or they may perform a purely decorative role. As a decorative element, the arch dates back to the 4th millennium BC, but stru ...

es, each supported by a

colonnade

In classical architecture, a colonnade is a long sequence of columns joined by their entablature, often free-standing, or part of a building. Paired or multiple pairs of columns are normally employed in a colonnade which can be straight or curv ...

, recalling the architecture of the central squares of the

bastides of Southwest France and those of the cities of the

Ionian Islands

The Ionian Islands (Modern Greek: , ; Ancient Greek, Katharevousa: , ) are a archipelago, group of islands in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece. They are traditionally called the Heptanese ("Seven Islands"; , ''Heptanēsa'' or , ''Heptanē ...

(such as

Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

).

These galleries are home to many small markets and businesses, as well as traditional and more modern cafes and restaurants. Most of their terraces extend over the square itself, which is shaded by several hundred-year-old

plane trees

''Platanus'' ( ) is a genus consisting of a small number of tree species native to the Northern Hemisphere. They are the sole living members of the family Platanaceae.

All mature members of ''Platanus'' are tall, reaching in height. The type ...

. In the center, surrounded by two majestic

phoenix, is a monument commemorating the

battle of Navarino, an

obelisk

An obelisk (; , diminutive of (') ' spit, nail, pointed pillar') is a tall, slender, tapered monument with four sides and a pyramidal or pyramidion top. Originally constructed by Ancient Egyptians and called ''tekhenu'', the Greeks used th ...

dedicated to the victory of the Allied fleets and their three

admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

s, the British

Edward Codrington, the French

Henri de Rigny and the Russian

Lodewijk van Heiden

Lodewijk Sigismund Vincent Gustaaf Reichsgraf van Heiden (; ; 6 September 1773 – 17 October 1850) was a Dutch naval officer and Orangism (Dutch Republic), Orangist who went into exile from the Batavian Republic and served in the Russian N ...

.

Churches

On the eastern slope of Pylos hill is the Church of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary (''Ieros Naos tis Kimiseos tis Theotokou''), while to the west, inside the ''Neokastro'', is the former Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior (''Ieros Naos tis Metamorphosis tou Sotiros''), both of which belong to the Metropolis of Messenia. The Church of the Transfiguration occasionally organizes religious activities (it has been converted into a museum and exhibition center), while that of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary still gathers many faithful during its regular services, and particularly during the celebration of Easter and the Myrtidiotissa Virgin (the Virgin with

myrtles, to whom the church is dedicated) which attract many pilgrims from Athens and abroad who come to take part in processions that take place in the center of the city.

File:Pylos, Holy Assumption Church 1.jpg, The Church of the Dormition of the Virgin Mary

File:Ναός της Μεταμορφώσεως του Σωτήρος (Νιόκαστρο, Πύλος) Θέα απο το κάστρο.STG 7387-2.jpg, The Church of the Transfiguration of the Savior

The port and the marina

The port of Pylos is one of the safest boarding destinations for ships traveling in the

Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

. Navarino Bay continues to regularly serve as a shelter for ships during storms in the Mediterranean Sea. In addition, its strategic location between the

Ionian Sea

The Ionian Sea (, ; or , ; , ) is an elongated bay of the Mediterranean Sea. It is connected to the Adriatic Sea to the north, and is bounded by Southern Italy, including Basilicata, Calabria, Sicily, and the Salento peninsula to the west, ...

and the

Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

makes it an ideal destination for an intermediate station on the route to the

Cyclades

The CYCLADES computer network () was a French research network created in the early 1970s. It was one of the pioneering networks experimenting with the concept of packet switching and, unlike the ARPANET, was explicitly designed to facilitate i ...

, the

Dodecanese Islands or to

Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

. With its modern pier, it frequently welcomes many

cruise ship

Cruise ships are large passenger ships used mainly for vacationing. Unlike ocean liners, which are used for transport, cruise ships typically embark on round-trip voyages to various ports of call, where passengers may go on Tourism, tours k ...

s during the summer season. To the east of the port, there is also the

marina

A marina (from Spanish , Portuguese and Italian : "related to the sea") is a dock or basin with moorings and supplies for yachts and small boats.

A marina differs from a port in that a marina does not handle large passenger ships or cargo ...

of Pylos, for which a project of modernization is currently running to meet the requirements for the rapid tourism development of the region.

Around Pylos

The Palace of Nestor

North of Pylos () and south of the town of

Chora

Chora may refer to:

Places Greece

* Chora, old capital of the island of Alonnisos

* Chora, village on the island of Folegandros

* Chora, Ios, capital of the island of Ios

* Chora, Messenia, a small town in Messenia in the Peloponnese

* Chora, p ...

(4 kilometres), is the hill of ''Ano Englianos'' which houses the Mycenaean

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

palace known as the "Palace of Nestor" (1600–1200 BC). This palace remains today in Greece the best preserved palace and one of the most important of all

Mycenaean civilization. The remains of the palace consist of the throne room with its foyer, an anteroom, passageways, large warehouses, the external walls of the palace, unique baths, galleries, and 90 meters away from the palace, a

beehive tholos tomb (funerary chamber with dome) perfectly restored in 1957 (''Tholos tomb IV)''. Very recently, in 2015, the team of American archaeologists

Sharon Stocker and

Jack L. Davis of the

University of Cincinnati

The University of Cincinnati (UC or Cincinnati, informally Cincy) is a public university, public research university in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States. It was founded in 1819 and had an enrollment of over 53,000 students in 2024, making it the ...

discovered and excavated, near the palace, the

tomb of the "Griffin Warrior", and even more recently in 2017, two other tholos tombs (''Tholos tombs VI and VII''), all three containing a multitude of cultural artifacts and jewels of exceptional delicacy (such as the

Pylos Combat Agate or a golden pendant depicting the head of the Egyptian goddess

Hathor

Hathor (, , , Meroitic language, Meroitic: ') was a major ancient Egyptian deities, goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god R ...

, which show that Pylos had trading connections, previously unknown, with Egypt and the Near East around 1500 B.C.E).

In June 2016, the site reopened to the public after 3 years of work to replace the old roof of the 1960s with a modern structure with elevated walkways for visitors. The archaeological site of the Palace of Nestor can be visited every day, except on holidays and on Tuesdays.

[Admission days and hours on the site of the Ministry of Culture and Sports: ]

Palace of Nestor

''

File:Two Mycenaean chariot warriors on a fresco from Pylos about 1350 BC.jpg, Warriors on a chariot. Fresco in Nestor's palace (LHIIIA/B period, around 1350 BC)

File:Lyre Player and Bird Fresco from Pylos Throne Room.jpg, Lyre Player and Bird. Fresco in Nestor's palace (LHIIIB period, around 1300 BC)

File:Battle Scene Fresco from Pylos.jpg, Battle Scene. Fresco in Nestor's palace (LHIIIB period, around 1300 BC)

The Archaeological Museum of Chora

The archaeological museum is located in the center of the village of

Chora

Chora may refer to:

Places Greece

* Chora, old capital of the island of Alonnisos

* Chora, village on the island of Folegandros

* Chora, Ios, capital of the island of Ios

* Chora, Messenia, a small town in Messenia in the Peloponnese

* Chora, p ...

, located 4 kilometres north of the Palace of Nestor. The museum was built in 1969 to house the artifacts discovered in Nestor's Palace and in the rest of the region. However, some of them are currently exposed in the

National Archaeological Museum of Athens, in the first room devoted to Mycenaean civilization. The Museum of Chora has three rooms. The first room contains finds almost exclusively from the tombs of the region: pots, weapons and jewelry. The second room contains finds from the region of Englianos and from the Palace of Nestor. In addition to the large storage jars and other ceramics from the palace warehouses, there are some wall

fresco

Fresco ( or frescoes) is a technique of mural painting executed upon freshly laid ("wet") lime plaster. Water is used as the vehicle for the dry-powder pigment to merge with the plaster, and with the setting of the plaster, the painting become ...

es, such as that depicting a lyre player with a bird, as well as war and hunting scenes. In the last room are exposed other finds from the hill of Englianos and the Palace of Nestor and in particular part of the contents of the tombs of this region, such as giant vases, cups and jewelry. The Archaeological Museum of Chora can be visited every day, except on public holidays and on Tuesdays.

[Admission days and hours on the site of the Ministry of Culture and Sports: ]

Archaeological Museum of Chora

''

The lagoon of Gialova and the beaches of Voïdokilia and Divari

North of Navarino Bay, near the village of

Gialova, the

Gialova wetland (''Osman-aga lake'') is one of 10 major lagoons in Greece.

Part of the

Natura 2000 network, it is considered a place of remarkable natural beauty and as one of the important bird areas in Europe. It has also been listed as a 1500-acre archaeological site, lying between Gialova and the bay of Voidokilia. Its alternative name of ''Vivari'' is Latin, meaning 'fishponds'. With a depth, at its deepest point, of no more than four meters, its pond constitutes an

ornithological reserve of exceptional importance in Europe, as it is the southernmost stopover of

birds migrating between the Balkans and Africa. It gives shelter to no fewer than 270 bird species, among them

greater flamingos,

glossy ibis

The glossy ibis (''Plegadis falcinellus'') is a water bird in the order Pelecaniformes and the ibis and spoonbill family Threskiornithidae. The scientific name derives from Ancient Greek ''plegados'' and Latin, ''falcis'', both meaning "sickle" a ...

,

grey herons,

great egret

The great egret (''Ardea alba''), also known as the common egret, large egret, great white egret, or great white heron, is a large, widely distributed egret. The four subspecies are found in Asia, Africa, the Americas, and southern Europe. R ...

s,

little egrets,

Eurasian curlews,

golden plovers,

black-winged stilts,

great cormorants,

common kingfisher

The common kingfisher (''Alcedo atthis''), also known as the Eurasian kingfisher and river kingfisher, is a small kingfisher with seven subspecies recognized within its wide distribution across Eurasia and North Africa. It is resident in much of ...

s,

ruff Ruff may refer to:

Places

*Ruff, Virginia, United States, an unincorporated community

*Ruff, Washington, United States, an unincorporated community

Other uses

*Ruff (bird) (''Calidris pugnax'' or ''Philomachus pugnax''), a bird in the wader famil ...

s,

garganey

The garganey (''Spatula querquedula'') is a small dabbling duck. It breeds in much of Europe and across the Palearctic, but is strictly bird migration, migratory, with the entire population moving to Africa, India (in particular Santragachi), Ban ...

s, but also

Audouin's gulls and birds of prey (

lesser kestrels,

osprey

The osprey (; ''Pandion haliaetus''), historically known as sea hawk, river hawk, and fish hawk, is a diurnal, fish-eating bird of prey with a cosmopolitan range. It is a large raptor, reaching more than in length and a wingspan of . It ...

s,

peregrine falcon

The peregrine falcon (''Falco peregrinus''), also known simply as the peregrine, is a Cosmopolitan distribution, cosmopolitan bird of prey (raptor) in the family (biology), family Falconidae renowned for its speed. A large, Corvus (genus), cro ...

s and

imperial eagles). It is Gialova, too, which plays host to a very rare species, nearing extinction throughout Europe, the