Punitive Campaign on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish

Punishment, commonly, is the imposition of an undesirable or unpleasant outcome upon an individual or group, meted out by an authority—in contexts ranging from child discipline to criminal law—as a deterrent to a particular action or behav ...

a political entity

A polity is a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of political institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources.

A polity can be any group of people organized for governance ...

or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state

State most commonly refers to:

* State (polity), a centralized political organization that regulates law and society within a territory

**Sovereign state, a sovereign polity in international law, commonly referred to as a country

**Nation state, a ...

or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong behavior by miscreants, as revenge

Revenge is defined as committing a harmful action against a person or group in response to a grievance, be it real or perceived. Vengeful forms of justice, such as primitive justice or retributive justice, are often differentiated from more fo ...

or corrective action

Corrective and preventive action (CAPA or simply corrective action) consists of improvements to an organization's processes taken to eliminate causes of non-conformities or other undesirable situations. It is usually a set of actions, laws or regu ...

, or to apply strong diplomatic pressure without a formal declaration of war

A declaration of war is a formal act by which one state announces existing or impending war activity against another. The declaration is a performative speech act (or the public signing of a document) by an authorized party of a national gov ...

(e.g. surgical strike

A surgical strike is a military attack which is intended to damage only a legitimate military target, with no or minimal collateral damage to surrounding structures, vehicles, buildings, or the general public infrastructure and utilities.

Desc ...

). In the 19th century, punitive expeditions were used more commonly as pretexts for colonial adventures that resulted in annexations, regime changes or changes in policies of the affected state to favour one or more colonial powers

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an imperialist project, colonialism can also take ...

.

Stowell (1921) provides the following definition:

When the territorial sovereign is too weak or is unwilling to enforce respect for international law, a state which is wronged may find it necessary to invade the territory and to chastise the individuals who violate its rights and threaten its security.

Historical examples

*In the 5th century BC, theAchaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

launched a series of campaigns against Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

to punish certain Greek city-states for involving themselves in the Ionian Revolt

The Ionian Revolt, and associated revolts in Aeolis, Doris (Asia Minor), Doris, Ancient history of Cyprus, Cyprus and Caria, were military rebellions by several Greek regions of Asia Minor against Achaemenid Empire, Persian rule, lasting from 499 ...

.

*In the early 1st century AD, Germanicus

Germanicus Julius Caesar (24 May 15 BC – 10 October AD 19) was a Roman people, Roman general and politician most famously known for his campaigns against Arminius in Germania. The son of Nero Claudius Drusus and Antonia the Younger, Germanicu ...

engaged in punitive expeditions against the Germanic tribes as repercussion for the Roman Legions that were destroyed in the Battle of Teutoburg Forest

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, also called the Varus Disaster or Varian Disaster () by Roman historians, was a major battle fought between an alliance of Germanic peoples and the Roman Empire between September 8 and 11, 9 AD, near mo ...

.

*In 518, Negus

''Negus'' is the word for "king" in the Ethiopian Semitic languages and a Ethiopian aristocratic and court titles, title which was usually bestowed upon a regional ruler by the Ethiopian Emperor, Negusa Nagast, or "king of kings," in pre-1974 Et ...

Kaleb of Axum

Kaleb (, Latin: Caleb), also known as Elesbaan (, ), was King of Aksum, which was situated in what is now Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Name

Procopius calls him "Hellestheaeus," a variant of the Greek version of his regnal name, (''Histories'', 1.20 ...

dispatched a punitive expedition

A punitive expedition is a military journey undertaken to punish a political entity or any group of people outside the borders of the punishing state or union. It is usually undertaken in response to perceived disobedient or morally wrong beha ...

against the Himyarite Kingdom

Himyar was a polity in the southern highlands of Yemen, as well as the name of the region which it claimed. Until 110 BCE, it was integrated into the Qataban, Qatabanian kingdom, afterwards being recognized as an independent kingdom. According ...

in response to the persecution of Christians

The persecution of Christians can be historically traced from the first century of the Christian era to the present day. Christian missionaries and converts to Christianity have both been targeted for persecution, sometimes to the point ...

by the Himyarite Jews.

*In the 13th century, Genghis Khan

Genghis Khan (born Temüjin; August 1227), also known as Chinggis Khan, was the founder and first khan (title), khan of the Mongol Empire. After spending most of his life uniting the Mongols, Mongol tribes, he launched Mongol invasions and ...

, the founder of the Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

, often engaged in punitive expeditions, either as a pretext or to quell rebellions against his rule. Some notable examples include his invasion of Khwarazim and his campaigns against the Western Xia kingdom.

*Also in the 13th century, Kublai Khan

Kublai Khan (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder and first emperor of the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty of China. He proclaimed the ...

, a grandson of Genghis and the founder of the Yuan Dynasty

The Yuan dynasty ( ; zh, c=元朝, p=Yuáncháo), officially the Great Yuan (; Mongolian language, Mongolian: , , literally 'Great Yuan State'), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after Div ...

, sent emissaries demanding tribute from the Singhasari kingdom

Singhasari ( or , ), also known as Tumapel, was a Javanese Hindu-Buddhist kingdom located in east Java between 1222 and 1292. The kingdom succeeded the Kingdom of Kediri as the dominant kingdom in eastern Java. The kingdom's name is cogn ...

of Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

. The ruler of the Singhasari kingdom, Kertanagara

Sri Maharajadiraja Sri Kertanagara Wikrama Dharmatunggadewa, Kritanagara, or Sivabuddha (died 1292), was the last and most important ruler of the Singhasari kingdom of Java, reigning from 1268 to 1292. Under his rule Javanese trade and power deve ...

, refused to pay tribute and tattooed a Chinese messenger, Meng Qi, on his face. A punitive expedition sent by Kublai Khan arrived off the coast of Java in 1293. Jayakatwang

Jayakatwang (died c.1293) was the king of short-lived second Kingdom of Kediri (also known as Gelang-Gelang Kingdom) of Java, after his overthrow of Kertanegara, the last king of Singhasari. He was eventually defeated by Raden Wijaya, Kertanega ...

, a rebel from the Kediri Kingdom, had killed Kertanagara by that time. The Mongols allied with Raden Wijaya

Raden Wijaya or Raden Vijaya, also known as Nararya Sangramawijaya and his regnal name Kertarajasa Jayawardhana was a Javanese emperor and founder of the Majapahit Empire who ruled from 1293 until his death in 1309.Slamet Muljana, 2005, ''Run ...

of Majapahit

Majapahit (; (eastern and central dialect) or (western dialect)), also known as Wilwatikta (; ), was a Javanese people, Javanese Hinduism, Hindu-Buddhism, Buddhist thalassocracy, thalassocratic empire in Southeast Asia based on the island o ...

against Jayakatwang and, once the Singhasari kingdom was destroyed, Wijaya turned against the Mongols and forced them to withdraw in confusion.

*In 1599, the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

conquistador

Conquistadors (, ) or conquistadores (; ; ) were Spanish Empire, Spanish and Portuguese Empire, Portuguese colonizers who explored, traded with and colonized parts of the Americas, Africa, Oceania and Asia during the Age of Discovery. Sailing ...

Juan de Oñate

Juan de Oñate y Salazar (; 1550–1626) was a Spanish conquistador, explorer and viceroy of the province of Santa Fe de Nuevo México in the viceroyalty of New Spain, in the present-day U.S. state of New Mexico. He led early Spanish expedition ...

ordered his nephew Vicente de Zaldívar

Vicente de Zaldívar (c. 1573 – before 1650) was a Spanish soldier and explorer in New Mexico. He led the Spanish force which perpetrated the Acoma Massacre at the Acoma Pueblo in 1599. He led or participated in several expeditions onto the Gr ...

to engage in a punitive expedition against the Keres

In Greek mythology, the Keres (; Ancient Greek: Κῆρες) were female death-spirits. They were the goddesses who personified violent death and who were drawn to bloody deaths on battlefields. Although they were present during death and dyin ...

natives of Acoma Pueblo

Acoma Pueblo ( , ) is a Native American pueblo approximately west of Albuquerque, New Mexico, in the United States.

Four communities make up the village of Acoma Pueblo: Sky City (Old Acoma), Acomita, Anzac, and McCartys. These communities ...

. When the Spanish arrived, they fought a three-day battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

with the Keres leaving about 800 men, women and children dead.

*During the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

, Spanish Admiral Luis Fajardo made a successful raid to the Caribbean

The Caribbean ( , ; ; ; ) is a region in the middle of the Americas centered around the Caribbean Sea in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, mostly overlapping with the West Indies. Bordered by North America to the north, Central America ...

in 1605 with his fleet. He sailed from Spain to Araya, on the Venezuelan coast, where he massacred

A massacre is an event of killing people who are not engaged in hostilities or are defenseless. It is generally used to describe a targeted killing of civilians en masse by an armed group or person.

The word is a loan of a French term for "b ...

a fleet of smugglers and Dutch privateers who blocked the area and were engaged in illegally extracting salt

In common usage, salt is a mineral composed primarily of sodium chloride (NaCl). When used in food, especially in granulated form, it is more formally called table salt. In the form of a natural crystalline mineral, salt is also known as r ...

.

* During the First Anglo-Powhatan War (1610–1614), Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr

Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr ( ; 9 July 1576 – 7 June 1618), was an English nobleman, for whom the bay, the river, and, consequently, a Native American people and U.S. state, all later called "Delaware", were named. A member of the Ho ...

(1577–1618), an English nobleman, was appointed Virginia's first royal governor and ordered to defend the colony against the Powhatan

Powhatan people () are Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.

Their Powh ...

. Lord de la Warr waged a punitive campaign to subdue the Powhatan after they had killed the colony’s council president, John Ratcliffe

John Lee Ratcliffe (born October 20, 1965) is an American politician and attorney who has served as the ninth director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) since 2025. He previously served as the sixth director of national intelligence from ...

.

*In the summer of 1614, Ottomans led by Damat Halil Pasha

Damat Halil Pasha (died 1629, Istanbul), also known as Khalil Pasha, was an Ottoman Armenian statesman. He was grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire in 1616–1619 and 1626–1628.İsmail Hâmi Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, Türkiye Yayın ...

engaged a successful punitive expedition against Sefer Dā'yl, an insurgent in Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis (from , meaning "three cities") may refer to:

Places Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in the Pelasgiotis district, Thessaly, near Larissa ...

.

*In 1784, a brief expedition was carried out by Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

and its native allies against the Anlo Ewe

The Anlo Ewe are a sub-group of the Ewe people of approximately 6 million people, inhabiting southern Togo, southern Benin, southwest Nigeria, and south-eastern parts of the Volta Region of Ghana; meanwhile, a majority of Ewe are located in the ...

. in the so-called Sagbadre War

The Sagbadre War was a brief punitive expedition carried out by Danish Gold Coast, Denmark-Norway and its native allies against the Anlo Ewe.

The war gets its name from a Danish official nicknamed Sagbadre, meaning "gulp" or "swallow" in Ewe ...

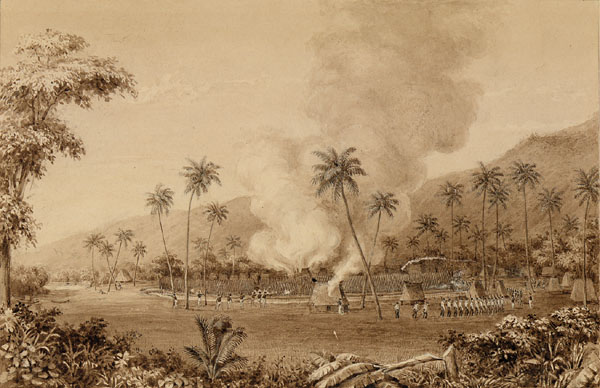

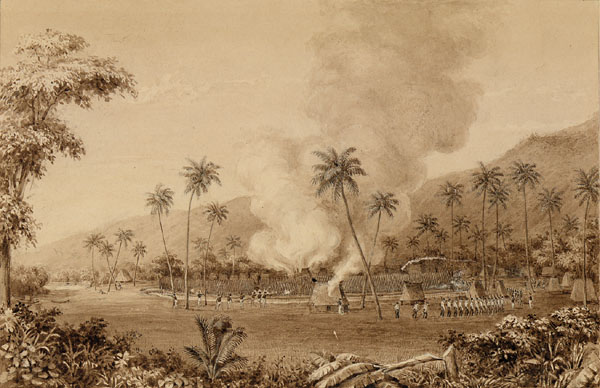

*From 1838 to 1842, ships of the United States Exploring Expedition

The United States Exploring Expedition of 1838–1842 was an exploring and surveying expedition of the Pacific Ocean and surrounding lands conducted by the United States. The original appointed commanding officer was Commodore Thomas ap Catesby ...

engaged in three punitive expeditions against Pacific islanders.

* The First Opium War

The First Opium War ( zh, t=第一次鴉片戰爭, p=Dìyīcì yāpiàn zhànzhēng), also known as the Anglo-Chinese War, was a series of military engagements fought between the British Empire and the Chinese Qing dynasty between 1839 and 1 ...

(1839–1842) was a retaliation against the burning of opiate products by Commissioner Lin Zexu

Lin Zexu (30 August 1785 – 22 November 1850), courtesy name Yuanfu, was a Chinese political philosopher and politician. He was a head of state (Viceroy), Governor General, scholar-official, and under the Daoguang Emperor of the Qing dynasty ...

, which resulted in the opening of a number of ports, the cession

The act of cession is the assignment of property to another entity. In international law it commonly refers to land transferred by treaty. Ballentine's Law Dictionary defines cession as "a surrender; a giving up; a relinquishment of jurisdicti ...

of Hong Kong

Hong Kong)., Legally Hong Kong, China in international treaties and organizations. is a special administrative region of China. With 7.5 million residents in a territory, Hong Kong is the fourth most densely populated region in the wor ...

to Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

, and the Treaty of Nanjing

The Treaty of Nanking was the peace treaty which ended the First Opium War (1839–1842) between Great Britain and the Qing dynasty of China on 29 August 1842. It was the first of what the Chinese later termed the "unequal treaties".

In the ...

.

*The 1842 Ivory Coast Expedition was led by Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a United States Navy officer who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War. He led the Perry Expedition that Bakumatsu, ended Japan' ...

against the Bereby people of West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

after two attacks on American merchant ships.

*The Battle of Kabul in 1842 was undertaken by the British against the Afghans following their disastrous retreat from Kabul in which 16,000 people were killed.

*The French Campaign against Korea in 1866 was a response to the earlier execution by Korea of French priests proselytizing in Korea.

*The 1867 Formosa Expedition

The Formosa Expedition (), or the Taiwan Expedition of 1867, was a punitive expedition launched by the United States against the Paiwan, an indigenous Taiwanese tribe. The expedition was undertaken in retaliation for the ''Rover'' incide ...

was a failed punitive operation of the United States to Taiwan.

*The 1868 British Expedition to Abyssinia

The British Expedition to Abyssinia was a rescue mission and punitive expedition carried out in 1868 by the armed forces of the British Empire against the Ethiopian Empire (also known at the time as Abyssinia). Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia, ...

(Ethiopia) was a rescue mission and punitive expedition against Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia

Tewodros II (, once referred to by the English cognate Theodore; baptized as Kassa, – 13 April 1868) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1855 until his death in 1868. His rule is often placed as the beginning of modern Ethiopia and brought an end to ...

, who had imprisoned several missionaries and two representatives of the British government in an attempt to force the British government to comply with his requests for military assistance. The commander of the expedition, General Sir Robert Napier, was victorious in every battle against the troops of Tewodros, captured the Ethiopian capital, and rescued all the hostages.

*The United States expedition to Korea

The United States expedition to Korea, known in Korea as the ''Shinmiyangyo'' () or simply the Korean Expedition, was an American military action in Korea that took place predominantly on and around Ganghwa Island in 1871.

Background

Freder ...

in 1871 was in retaliation to the ''General Sherman'' incident, where a U.S. merchant ship was burned as it entered Pyongyang.

*The 1874 Japanese expedition against Formosa

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The island of Taiwan, formerly known to Westerners as Formosa, has an area of and makes up 99% of the land under ROC control. It lies about across the Taiwan Strait f ...

.

*Benin Expedition of 1897

The Benin Expedition of 1897 was a punitive expedition by a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British force of 1,200 men under Harry Rawson, Sir Harry Rawson. It came in response to the ambush and slaughter of a 250-strong party led ...

was a British punitive action that led to the annexation of the Kingdom of Benin

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as Great Benin, is a traditional kingdom in southern Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th century until 1975. The Kingdom of Benin's c ...

. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' reported on January 13, 1897 that a "punitive expedition" would be formed to "punish the murderers of the Benin City expedition".

*The Eight-Nation Alliance

The Eight-Nation Alliance was a multinational military coalition that invaded northern China in 1900 during the Boxer Rebellion, with the stated aim of relieving the foreign legations in Beijing, which were being besieged by the popular Boxer ...

's invasion of China in 1900 was in response to the Siege of the International Legations

The siege of the International Legations was a pivotal event during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, in which foreign diplomatic compounds in Peking (now Beijing) were besieged by Chinese Boxers and Qing Dynasty troops. The Boxers, fueled by anti-f ...

during the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

.

*British expedition to Tibet

The British expedition to Tibet, also known as the Younghusband expedition, began in December 1903 and lasted until September 1904. The expedition was effectively a temporary invasion by British Indian Army, British Indian Armed Forces under th ...

in December 1903-September 1904. The expedition was effectively a temporary invasion by British Indian Armed Forces under the auspices of the Tibet Frontier Commission

The Tibet Frontier Commission headed the British expedition to Tibet in 1903–04. The Commission comprised seven diplomats and army officers, led by Colonel Francis Younghusband. Despatched on the orders of George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzo ...

, whose purported mission was to establish diplomatic relations and resolve the dispute over the border between Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

and Sikkim

Sikkim ( ; ) is a States and union territories of India, state in northeastern India. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China in the north and northeast, Bhutan in the east, Koshi Province of Nepal in the west, and West Bengal in the ...

.

*The Herero and Namaqua genocide

Herero may refer to:

* Herero people, a people belonging to the Bantu group, with about 240,000 members alive today

* Herero language, a language of the Bantu family (Niger-Congo group)

* Herero and Nama genocide

* Herero chat, a species of bi ...

in German South-West Africa

German South West Africa () was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

German rule over this territory was punctuated by ...

by the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

.

*During World War I, the battle of Asiago

The Südtirol Offensive, also known as the Battle of Asiago or Battle of the Plateaux (in Italian: Battaglia degli Altipiani), wrongly nicknamed ''Strafexpedition'' "Punitive expedition" (this name has no reference in official Austrian document ...

, nicknamed (punitive expedition), was an unsuccessful counteroffensive launched by Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

against the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

.

*The Pancho Villa Expedition

The Pancho Villa Expedition—now known officially in the United States as the Mexican Expedition, but originally referred to as the "Punitive Expedition, US Army"—was a military operation conducted by the United States Army against the para ...

from 1916 to 1917, led by General John J. Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was an American army general, educator, and founder of the Pershing Rifles. He served as the commander of the American Expeditionary For ...

, was an operation in retaliation against Pancho Villa's incursion into the United States.

*Suppression of the 1920 Iraqi Revolt against the British Mandate of Mesopotamia

The Mandate for Mesopotamia () was a proposed League of Nations mandate to cover Ottoman Iraq (Mesopotamia). It would have been entrusted to the United Kingdom but was superseded by the Anglo-Iraqi Treaty, an agreement between Britain and Ira ...

.

*In World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, German were involved in the mass murders of civilians in Poland and USSR as the punishment for the acts of resistance and collaboration with the communists.

*During the 1965 Indo-Pakistani War, the Indian offensive across the international border into Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

was characterized as a punitive expedition necessitated by Pakistan's offensive across the CFL into Indian Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir Panjal Range. The term has since ...

during Operation Grand Slam

Operation Grand Slam was a key military operation of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. It refers to a plan drawn up by the Pakistan Army in May 1965, that consisted of an attack on the vital Akhnoor Bridge in Jammu and Kashmir, India. The br ...

.

*The 1979 invasion of Vietnam by China was characterised by Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

as an act of punishment necessitated by Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia, saying that "Children who don't listen have to be spanked."

*The destruction of half of the operational ships of the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy

The Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN; ), also referred as the Iranian Navy (abbreviated NEDAJA; ), is the naval warfare service branch of Iran's regular military, the Islamic Republic of Iran Army, Islamic Republic of Iran Army (''Artesh''). I ...

by the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

in 1988 during Operation Praying Mantis

Operation Praying Mantis was the 18 April 1988 attack by the United States on Iranian naval targets in the Persian Gulf in retaliation for the mining of a U.S. warship four days earlier.

On 14 April, the American guided missile frigate stru ...

was punishment for damaging USS ''Samuel B. Roberts'' by mining international waters of the Persian Gulf.

*The 2016 Indo-Pakistani military confrontation began with alleged punitive "surgical strikes" carried out by India. These strikes were a punitive action in response to Pakistan's inaction in curbing the activities of terrorist organisations such as Lashkar-e-Taiba

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) is a Pakistani Islamism, Islamist militant organization driven by a Salafi jihadism, Salafi jihadist ideology. The organisation's primary stated objective is to merge the whole of Kashmir with Pakistan. It was founded in 19 ...

and Jaish-e-Mohammad

Jaish-e-Mohammed (JeM) is a Pakistani Deobandi jihadist Islamist militant group active in Kashmir.: "as soon as he was freed, Masood Azhar was back in Pakistan where he founded a new jihadist movement, Jaish-e-Mohammed, which became one of ...

, which India held responsible for the Uri attack.

*The 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February 2022, , starting the largest and deadliest war in Europe since World War II, in a major escalation of the Russo-Ukrainian War, conflict between the two countries which began in 2014. The fighting has caused hundreds of thou ...

has been described as a punitive expedition.

*Israel's 2024 invasion into the Hamas-run Gaza strip following the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel

On October 7, 2023, Hamas and several other Palestinians, Palestinian militant groups launched coordinated armed incursions from the Gaza Strip into the Gaza envelope of southern Israel, the first invasion of Israeli territory since the 1948 ...

has been labeled a punitive expedition.

See also

* Letter of marque and reprisalNotes

References

* * {{Authority control Penology