Pterodon (mammal) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Pterodon'' (

In 1838, French zoologist

In 1838, French zoologist

The taxonomic positions of ''Pterodon'' and ''Hyaenodon'' for much of the 19th century were disputed by many palaeontologists. In 1846,

The taxonomic positions of ''Pterodon'' and ''Hyaenodon'' for much of the 19th century were disputed by many palaeontologists. In 1846,

The order Hyaenodonta is diagnosed as having an elongated and narrow skull with a narrow cranial base (basicranium), a high and narrow

The order Hyaenodonta is diagnosed as having an elongated and narrow skull with a narrow cranial base (basicranium), a high and narrow

The subfamily Hyainailourinae within the family Hyainailouridae is diagnosed in the upper dentition as having high and secant-shaped paraconid cusps and cone-shaped metacone and paracone cusps on the M1-M2 molars, a weak to absent P3 lingual cingulum, and a lack of any continuous lingual cingulum on P4. For lower dentition, the M3 talonid cusp is reduced compared to those on M1-M2, and the protoconid and paraconid cusps are roughly equal in length in the molars.

''Pterodon'' ''sensu lato'' is diagnosed in its dental differences with other hyainailourid genera. It differs from ''Metapterodon'' in being larger, the presence of an M3 talonid cusp, larger M1-M2 tanolid cusps, narrower upper molars with shorter metastyle ridges, and an incomplete paracone-metacone cusp fusion. It differs also from ''Akhnatenavus'' in the talonid cusps of the molars being as wide as its trigonid cusps, roughly equal sizes of the protoconid and paraconid cusp sizes in the molars, unreduced premolar sizes, and a lack of diastemata for premolar spaces. ''Pterodon'' differs from ''Hyainailouros'' and ''

The subfamily Hyainailourinae within the family Hyainailouridae is diagnosed in the upper dentition as having high and secant-shaped paraconid cusps and cone-shaped metacone and paracone cusps on the M1-M2 molars, a weak to absent P3 lingual cingulum, and a lack of any continuous lingual cingulum on P4. For lower dentition, the M3 talonid cusp is reduced compared to those on M1-M2, and the protoconid and paraconid cusps are roughly equal in length in the molars.

''Pterodon'' ''sensu lato'' is diagnosed in its dental differences with other hyainailourid genera. It differs from ''Metapterodon'' in being larger, the presence of an M3 talonid cusp, larger M1-M2 tanolid cusps, narrower upper molars with shorter metastyle ridges, and an incomplete paracone-metacone cusp fusion. It differs also from ''Akhnatenavus'' in the talonid cusps of the molars being as wide as its trigonid cusps, roughly equal sizes of the protoconid and paraconid cusp sizes in the molars, unreduced premolar sizes, and a lack of diastemata for premolar spaces. ''Pterodon'' differs from ''Hyainailouros'' and '' In the upper dentition, the two incisors, conical in shape, are unequal in size, the central incisor being twice or thrice as large as the lateral incisor. Their shapes suggest that they play a role in piercing through food rather than cutting them. The upper canines, although much larger than other teeth of the upper dental row, are not as strong as those of extant

In the upper dentition, the two incisors, conical in shape, are unequal in size, the central incisor being twice or thrice as large as the lateral incisor. Their shapes suggest that they play a role in piercing through food rather than cutting them. The upper canines, although much larger than other teeth of the upper dental row, are not as strong as those of extant

In 1977, Radinsky made early size estimates for hyaenodonts with known skeletons and no known complete which he based size estimates off of other "creodonts." He estimated that ''P. dasyuroides'' had an estimated body length range of - and an estimated body weight range of -. However, due to the proportions of hyaenodonts being different from extant carnivorans, estimated values of them may not reflect their actual sizes.

Estimating the body sizes of hyaenodonts has proven difficult because they are extinct and have no modern analogues, plus dentally or cranially derived body sizes based on extant carnivorans are problematic since they have large crania in comparison to carnivorans, which produce unreasonably large estimated size values. As a result, hyaenodonts are measured more based on body mass and not estimated body size.

In 2015, Solé et al. estimated that based on the length of M1-M3 being , it may have weighed . Hyainailourids have been known for growing to typically larger sizes compared to other hyaenodonts, including the Paleogene and especially the Miocene. The estimated weight values for ''P. dasyuroides'' and other studied hyaenodonts remained unchanged in a 2020 paper by Solé et al.

In 1977, Radinsky made early size estimates for hyaenodonts with known skeletons and no known complete which he based size estimates off of other "creodonts." He estimated that ''P. dasyuroides'' had an estimated body length range of - and an estimated body weight range of -. However, due to the proportions of hyaenodonts being different from extant carnivorans, estimated values of them may not reflect their actual sizes.

Estimating the body sizes of hyaenodonts has proven difficult because they are extinct and have no modern analogues, plus dentally or cranially derived body sizes based on extant carnivorans are problematic since they have large crania in comparison to carnivorans, which produce unreasonably large estimated size values. As a result, hyaenodonts are measured more based on body mass and not estimated body size.

In 2015, Solé et al. estimated that based on the length of M1-M3 being , it may have weighed . Hyainailourids have been known for growing to typically larger sizes compared to other hyaenodonts, including the Paleogene and especially the Miocene. The estimated weight values for ''P. dasyuroides'' and other studied hyaenodonts remained unchanged in a 2020 paper by Solé et al.

The order Hyaenodonta occupied a wide range of body sizes/body masses and ranged from mesocarnivorous to

The order Hyaenodonta occupied a wide range of body sizes/body masses and ranged from mesocarnivorous to

For much of the Eocene, the world's environments were shaped by warm and humid climates, with subtropical to tropical closed forests being the dominant habitats. Multiple carnivorous mammal groups arose in Europe, Asia, Afro-Arabia, and North America, namely mesonychians, hyaenodonts, oxyaenids, and carnivoramorphs, dispersing between the continents. Several other prominent mammal orders arose within the continents by the early Eocene including the

For much of the Eocene, the world's environments were shaped by warm and humid climates, with subtropical to tropical closed forests being the dominant habitats. Multiple carnivorous mammal groups arose in Europe, Asia, Afro-Arabia, and North America, namely mesonychians, hyaenodonts, oxyaenids, and carnivoramorphs, dispersing between the continents. Several other prominent mammal orders arose within the continents by the early Eocene including the

The Grande Coupure extinction and faunal turnover event of western Europe, dating back to the earliest

The Grande Coupure extinction and faunal turnover event of western Europe, dating back to the earliest

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: (wing) + (tooth) meaning "wing tooth") is an extinct genus of hyaenodont in the family Hyainailouridae

Hyainailouridae ("hyena-like Felidae, cats") is a Paraphyly, paraphyletic family of extinct predatory mammals within the Polyphyly, polyphyletic superfamily Hyaenodonta, Hyainailouroidea within extinct order Hyaenodonta. Hyainailourids arose duri ...

, containing two species. The type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

''Pterodon dasyuroides'' is known exclusively from the late Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

to the earliest Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

of western Europe. The genus was first erected by the French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques-la-Bataille, Arques, near Dieppe, Seine-Maritime, Dieppe. As a young man, he went to Paris to study a ...

in 1839, who said that Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

presented one of its fossils to a conference in 1828 but died before he could make a formal description of it. It was the second hyaenodont genus with taxonomic validity after ''Hyaenodon

''Hyaenodon'' ("hyena-tooth") is an Extinction (biology), extinct genus of Carnivore, carnivorous Placentalia, placental mammals from extinct tribe Hyaenodontini within extinct subfamily Hyaenodontinae (in extinct Family (biology), family Hyaenod ...

'', but this resulted in taxonomic confusion over the validities of the two genera by other taxonomists. Although the taxonomic status of ''Pterodon'' was revised during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it became a wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined by e ...

for other hyaenodont species found in Africa and Asia. Today, only the type species is recognized as belonging to the genus while just one is pending reassessment to another genus.

''P. dasyuroides'' had cranial and dental characteristics typical of the Hyainailouridae such as an elongated, narrow, and proportionally large skull which measures ~ in length and dentition for hypercarnivorous

A hypercarnivore is an animal that has a diet that is more than 70% meat, either via active predation or by scavenging. The remaining non-meat diet may consist of non-animal foods such as fungi, fruits or other plant material. Some extant example ...

diets and bone-crushing similar to modern hyenas. Due to the scarcely known postcranial materials of the species, its overall anatomy is unknown, although it likely weighed and may have been similar to another Eocene-aged European hyainailourine '' Kerberos''.

The hyainailourine made its appearance in western Europe back when it was a semi-isolated archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

, likely originating from a ghost lineage from Afro-Arabia. It was one of the larger-sized carnivores of the continent, a typical trait of hyainailourines. It coexisted largely with faunas that were adapted to tropical to subtropical environments and grew strong levels of endemism, becoming a regular component based on fossil evidence from multiple localities. ''Pterodon'' went extinct by the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction and faunal turnover event in the earliest Oligocene of Europe, which was caused by shifts towards seasonality plus glaciation as well as closing seaway barriers that allowed for large faunal dispersals from Asia. Its extinction causes are uncertain but may have been the result of rapid habitat turnover, competition with immigrant faunas, or some combination of the two.

Taxonomy

Research history

Early history

In 1838, French zoologist

In 1838, French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 – 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques-la-Bataille, Arques, near Dieppe, Seine-Maritime, Dieppe. As a young man, he went to Paris to study a ...

made a review of palaeontological history and taxonomy as built upon from previous decades. Blainville recognized the importance of dentition in determining the affinities of fossil animals but criticized the overreliance of dental systems as automatically indicating taxonomic affinities. He then went on to examine reported fossil "didelphid

Opossums () are members of the marsupial order Didelphimorphia () endemic to the Americas. The largest order of marsupials in the Western Hemisphere, it comprises 126 species in 18 genera. Opossums originated in South America and entered North A ...

s" (the taxonomic group now known as "marsupial

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a r ...

s") in European land. He conducted reviews of fossils as previously described by Laizer and Parieu, concluding that ''Hyaenodon

''Hyaenodon'' ("hyena-tooth") is an Extinction (biology), extinct genus of Carnivore, carnivorous Placentalia, placental mammals from extinct tribe Hyaenodontini within extinct subfamily Hyaenodontinae (in extinct Family (biology), family Hyaenod ...

'' is a valid genus based on its dentition but rejected the idea of it being a didelph based on its dental system and its molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

being closer in affinity to modern carnivorans.

Blainville also mentioned a fossil of an upper jaw that the late Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

found and previously thought was close in affinity to the Tasmanian devil

The Tasmanian devil (''Sarcophilus harrisii''; palawa kani: ''purinina'') is a carnivorous marsupial of the family Dasyuridae. It was formerly present across mainland Australia, but became extinct there around 3,500 years ago; it is now con ...

(''Sarcophilus harrisii'') of New Holland (Australia)

''New Holland'' () is a historical European name for mainland Australia, Janszoon voyage of 1605–1606, first encountered by Europeans in 1606, by Dutch navigator Willem Janszoon aboard . The name was first applied to Australia in 1644 by the ...

. Previously, Cuvier presented the fossil to the French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in 1828 and thought that it was a large species of thylacine

The thylacine (; binomial name ''Thylacinus cynocephalus''), also commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, was a carnivorous marsupial that was native to the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmani ...

(''Thylacinus cynocephalus'') but died before he could make a formal description of it. Of note is that although the article of ''Hyaenodon'' by Blainville was first written and published in 1838, it was not until a year later in 1839 when it was republished that Blainville added a footnote to the paragraph about the upper jaw. In it, he said that he restudied that fossil from the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin () is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in ...

and again was certain that it was a "monodelphian" (today placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguished ...

) predator, which he named ''Pterodon dasyuroides''. The genus name means "wing tooth" and is a combination of the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

words "" (wing) and "" (tooth). The etymology of the type species name derives from the Australian marsupial genus ''Dasyurus

Quolls (; genus ''Dasyurus'') are carnivorous marsupials native to Australia and New Guinea. They are primarily nocturnal, and spend most of the day in a den. Of the six species of quoll, four are found in Australia and two in New Guinea. Anot ...

'' and the Greek suffix "" meaning "like" due to apparent initial confusion of the genus affinity by Blainville.

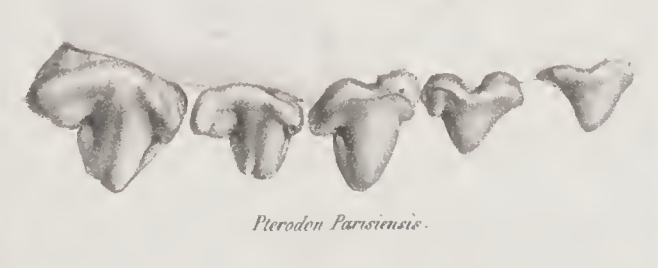

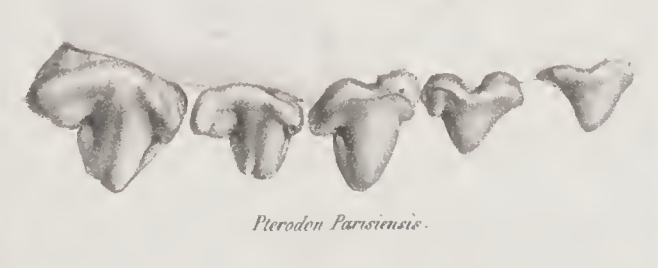

In 1841-1842, Blainville mentioned the genus ''Pterodon'' but replaced the previous species name with ''P. parisiensis''. He also stated that despite thinking that the mammal did not have close affinities with ''Dasyurus'', he did not have sufficient skull material to prove what mammal group it was closest to. The species name is in reference to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

where its first fossil was found.

Taxonomic disputes

The taxonomic positions of ''Pterodon'' and ''Hyaenodon'' for much of the 19th century were disputed by many palaeontologists. In 1846,

The taxonomic positions of ''Pterodon'' and ''Hyaenodon'' for much of the 19th century were disputed by many palaeontologists. In 1846, Auguste Pomel

Nicolas Auguste Pomel (20 September 1821 – 2 August 1898) was a French geologist, paleontologist and botanist. He worked as a mines engineer in Algeria and became a specialist in north African vertebrate fossils. He was Senator of Algeria for Or ...

argued that he was unsure if ''Pterodon'' belonged to the didelph clade based on its dentition being apparently similar to thylacines but having different skull structures from them and other marsupials. However, he rejected the position that ''Pterodon'' was more closely related to the monodelphs due to thinking that the skull did not closely resemble its members. Additionally, he said that it, ''Taxotherium'', and ''Hyaenodon'' are functionally the same genus if not the same species, therefore stating that the latter two genera are synonymous with ''Pterodon''. Pomel defined four species for the genus ''Pterodon'': ''P. parisiensis'', ''P. cuvieri'' (erected previously for ''Taxotherium'' as ''T. parisiense'' by Blainville), ''P. leptorhynchus'' (erected for ''Hyaenodon'' by Lazier and Parieu), and ''P. brachyrhynchus'' (previously named for ''Hyaenodon'' by Blainville).

In 1846, Paul Gervais

Paul Gervais (full name: François Louis Paul Gervais) (26 September 1816 – 10 February 1879) was a French palaeontologist and entomologist.

Biography

Gervais was born in Paris, where he obtained the diplomas of doctor of science and of medic ...

recognized the species ''P. requieni'', having named the species in honor of French naturalist Esprit Requien

Esprit Requien (6 May 1788, Avignon – 30 May 1851, Bonifacio, Corse-du-Sud) was a French naturalist, who made contributions in the fields of conchology, paleontology and especially botany.

From the age of 18, he was associated with the bo ...

, the founder and director of the Musee d' Avignon (now the Musée Requien

Museum Requien (and not Musée Requien) is a natural history museum in Avignon, France. Some of Jean Henri Fabre's work is displayed here.

Muséum Requien is named in honor of French naturalist Esprit Requien (6 May 1788, Avignon – 30 May 18 ...

) who allowed him and Marcel de Serres

Marcel may refer to:

People

* Marcel (given name), people with the given name Marcel

* Marcel (footballer, born August 1981), Marcel Silva Andrade, Brazilian midfielder

* Marcel (footballer, born November 1981), Marcel Augusto Ortolan, Brazilian ...

to study local fossil mammal specimens. In 1848-1852, however, he reclassified the species as ''Hyaenodon requieni'' (having recognized the validity of the genus) and listed ''P. dasyuroides'' as the only species of ''Pterodon''.

In 1853, Pomel changed his position by recognizing the validity of ''Hyaenodon'', restoring the taxonomic affinities of species previously classified as belonging to it and therefore establishing that they no are no longer classified under ''Pterodon'' (''H. leptorhynchus'' and ''H. brachyrhynchus''). He also reclassified ''Taxotherium'' as a junior synonym of ''Hyaenodon'' instead of ''Pterodon''. Within the genus ''Pterodon'', he recognized the species name ''P. dasyuroides'' instead of ''P. parisiensis'' and created two additional species based on dentition shapes and sizes: ''P. cuvieri'' and ''P. coquandi''.

European hyaenodont revisions

Gervais erected the species ''P. exiguum'' in 1873 based on dentition with some similarities to both ''Pterodon'' and ''Hyaenodon'' but noted that it may constitute a new genus once he has more fossil material. The palaeontologist then corrected himself in 1876 by stating that the species belongs to ''Hyaenodon'' as ''H. exiguum'', not ''Pterodon''. In 1876, Filhol recognized only ''P. dasyuroides'' among all species previously erected for the genus and named a new species ''P. biincisivus'' from the phosphorite deposits of Escamps, France. He, in addition to confirming the taxonomic validities of the two species, erected a third named ''P. quercyi'' in 1882. The French naturalist named a new species ''Oxyaena

''Oxyaena'' ("sharp hyena") is an extinct genus of placental mammals from extinct subfamily Oxyaeninae within extinct family Oxyaenidae, that lived in Europe, Asia and North America (with most specimens being found in Colorado) during the early E ...

galliæ'' based on dental remains being apparently similar to that of species of ''Oxyaena'' previously described by Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

in the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

deposits of New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

, United States. in The same year, Filhol also reported that an individual whose last name was Pradines recently discovered anterior portions of the skull of ''P. dasyuroides'' from the phosphate deposits of Limogne-en-Quercy.

English naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

made a review of known pan-carnivoran genera in 1884, classifying them within the order Carnivora and rejecting Cope's classification of the members into the suborder Creodonta

Creodonta ("meat teeth") is a former order of extinct carnivorous placental mammals that lived from the early Paleocene to the late Miocene epochs in North America, Europe, Asia and Africa. Originally thought to be a single group of animals ance ...

within the order Bunotheria. While Cope originally assigned ''Hyaenodon'' as the sole member of Hyaenodontidae

Hyaenodontidae ("hyena teeth") is a family of placental mammals in the extinct superfamily Hyaenodonta, Hyaenodontoidea. Hyaenodontids arose during the early Eocene and persisted well into the early Miocene. Fossils of this group have been found ...

and ''Pterodon'' plus ''Oxyaena'' into Oxyaenidae

Oxyaenidae ("sharp hyenas") is a family of extinct carnivorous placental mammals. Traditionally classified in order Creodonta, this group is now classified in its own order Oxyaenodonta ("sharp tooth hyenas") within clade Pan-Carnivora in mirord ...

, Lydekker felt that ''Pterodon'' was close in affinity to ''Hyaenodon'' and therefore belonged in Hyaenodontidae. For ''H. brachyhynchus'', he listed ''P. brachyhynchus'', ''P. requieni'', and ''H. requieni'' as junior synonyms. He also listed ''P. leptorhynchus'' as a junior synonym of ''H. leptorhynchus'' as well as ''H. exiguus'' and ''P. exiguus'' as synonyms of ''H. vulpinus''. For ''Pterodon'', he recognized ''P. dasyuroides'' as the main valid species of the genus and listed ''P. parisiensis'' as a definite synonym as well as ''P. cuvieri'' and ''P. coquandi'' as possible synonyms, although he did not invalidate ''P. biincisivus''. He also listed the species ''Oxyæna galliæ'' but thought that the genus could be merged into ''Pterodon'' due to minor dental differences and similarities to ''P. biincisivus''.

Swiss palaeontologist Ludwig Rütimeyer

(Karl) Ludwig Rütimeyer (26 February 1825 in Biglen, Canton of Bern – 25 November 1895 in Basel) was a Swiss zoologist, anatomist and paleontologist, who is considered one of the fathers of zooarchaeology.

Career

Rütimeyer studied at the Univ ...

erected another species named ''P. magnus'' in 1891 based on the larger dentition sizes compared to typical species of ''Pterodon''. However, in 1906, German scientist Rudolf Martin

Rudolf Martin (born 31 July 1967) is a German actor working mainly in the United States. He first appeared in off-Broadway productions and then moved on to extensive TV and film work. He has made guest appearances on numerous hit television seri ...

said that he wanted to synonymize ''P. magnum'' and the questionable ''P. quercyi'' with ''P. dasyuroides''. He also listed ''P. biincisivus'' as a synonym of ''P. dasyuroides'' and stated that only one species is valid within ''Pterodon''. Additionally, he revalidated the species ''O. galliæ'' but created the genus '' Paroxyaena'' for it, arguing that because oxyaenids are very weakly represented in Europe compared to North America and that therefore the species' similarities to oxyaenids may have an instance of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

.

In 1979, Brigitte Lange-Badré made a systematic review of known hyaenodonts from Europe including ''Pterodon''. She listed ''P. parisiensis'', ''P. cuvieri'', ''P. coquandi'', ''P. biincisivus'', and ''P. quercyi'' as synonyms of the only European species ''P. dasyuroides''. In addition, she listed ''P. magnum'' as a synonym of ''Paroxyaena galliae'' and listed ''Hyaenodon exiguus'' as taking taxonomic priority over ''H. vulpinus'', therefore making the latter name and ''P. exiguum'' synonyms.

Wastebasket history

For much of its history, ''Pterodon'' was awastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined by e ...

for middle to late Paleogene and Miocene hyainailourines that lacked unique or advanced dental traits that ''Hyaenodon'' had. Many of the species classified or formerly classified to ''Pterodon'' were of African or Asian origins. Within the 20th century, the species formerly classified to the genus ''Pterodon'' were '' Apterodon macrognathus'', '' Akhnatenavus leptognathus'', "''Hyainailouros

''Hyainailouros'' ("hyena-cat") is an extinct polyphyletic genus of hyaenodont belonging to the family Hyainailouridae that lived during the Early to Late Miocene, of which there were at least three species spread across Eurasia and Africa

...

''" ''bugtiensis'', ''Orienspterodon

''Orienspterodon'' ("eastern '' Pterodon''")

is an extinct genus of hyaenodonts from extinct paraphyletic subfamily Hyainailourinae within paraphyletic family Hyainailouridae, that lived from middle to late Eocene in China and Myanmar

My ...

dahkoensis'', and '' Neoparapterodon rechetovi''. Several species names previously assigned to ''Pterodon'' were later considered to be synonyms of ''Hyaenodon'' species, namely "''P. exploratus''" (= ''H. incertus''), "''P. californicus''" (= ''H. vetus''), and "''P. mongoliensis''" (= ''H. mongoliensis''). Also, both "''Pterodon nyanzae''" and "''Hyainailouros nyanzae''" were synonymized with ''Hyainailouros napakensis''. Additionally, ''Hemipsalodon

''Hemipsalodon'' ("half-scissor tooth") is an extinct genus of hyainailourid hyaenodonts from the subfamily Hyainailourinae that lived in North America during the middle to late Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch th ...

'' was made a synonym of ''Pterodon'' by Robert Joseph Gay Savage in 1965 while ''Metapterodon

''Metapterodon'' ("next to '' Pterodon''") is an extinct genus of hyainailourid hyaenodonts of the subfamily Hyainailourinae, that lived in Africa during the early Oligocene to early Miocene. Fossils of ''Metapterodon'' were recovered from the ...

'' was synonymized with it by Leigh M. Van Valen in 1967, but the synonymies were unsupported by later authors.

In 2025, the three African species previously assigned to ''Pterodon'', ''P. africanus''; ''P. phiomensis''; and ''P. syrtos''; were reassigned to newer genera. Shorouq F. Al-Ashqar et al. erected '' Sekhmetops'' for the former two species and ''Bastetodon

''Bastetodon'' (meaning "Bastet tooth") is an extinct genus of carnivorous hyaenodont mammals from the Early Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation of Egypt. The genus contains single species, ''B. syrtos'', which was originally assigned to the genu ...

'' for the latter. As a result of the synonymies, only one species assigned to ''Pterodon'' remains pending reassessment to another genus: ''P. hyaenoides'', which is classified as belonging to the Hyaenodontinae

Hyaenodontinae ("hyena teeth") is an extinct subfamily of predatory placental mammals from extinct family Hyaenodontidae. Fossil remains of these mammals are known from early Eocene to early Miocene deposits in Europe, Asia and North America

...

and is located in Asia.

In 1999, A.V. Lavrov mentioned in his dissertation paper a genus he erected named "''Epipterodon''" for which "''Pterodon''" ''hyaenoides'' would have been reclassified to. However, as the genus name has not yet been referenced and taxonomically validated in any peer-reviewed source, its name currently remains invalid.

Classification

''Pterodon'' has historically been classified undisputedly as at least being within the clade of hyaenodonts within the later 20th century, later being included within the subfamily Hyainailourinae. However, it was since 2015 that Floréal Solé et al. proposed the cladeHyainailouridae

Hyainailouridae ("hyena-like Felidae, cats") is a Paraphyly, paraphyletic family of extinct predatory mammals within the Polyphyly, polyphyletic superfamily Hyaenodonta, Hyainailouroidea within extinct order Hyaenodonta. Hyainailourids arose duri ...

, uniting the Hyainailourinae and Apterodontinae

Apterodontinae ("without winged tooth") is an extinct subfamily of hyaenodonts from extinct paraphyletic family Hyainailouridae, specialised for aquatic, otter-like habits. They lived in Africa and Europe from the late Eocene to middle Oligocene ...

under the family and therefore making it taxonomically differentiated from the Hyaenodontidae. They also suggested usage of the hyainailourine tribes Hyainailourini

Hyainailourinae ("hyena-like cats") is a paraphyletic subfamily of hyaenodonts from extinct paraphyletic family Hyainailouridae. They arose during the Middle Eocene in Africa, and persisted well into the Late Miocene. Fossils of this group have b ...

(where ''Pterodon'' was classified) and Paroxyaenini, although the tribe name usages for hyaenodonts remain uncommon in academic literature. In 2016, Matthew Borths et al. suggested that the Hyainailouridae had a close relationship with the Teratodontinae and therefore arranged the superfamily Hyainailouroidea to include them and include the Proviverrinae, Hyaenodontidae, and North American hyaenodont groups. The family Hyainailouridae has since become more accepted in academic literature, although there are alternate clade rank methods for hyainailourines.

The order Hyaenodonta

Hyaenodonta (" hyena teeth") is an extinct order of hypercarnivorous placental mammals of clade Pan-Carnivora from mirorder Ferae. Hyaenodonts were important mammalian predators that arose during the early Paleocene in Europe and persisted w ...

(replacing the now-invalidated clade Creodonta) is known first from the middle Paleocene of Afro-Africa, expanding to both Europe and Asia from Afro-Arabia in multiple "out-of-Africa" dispersal events. Although the true origins of the Hyainailouroidea is somewhat ambiguous, the Bayesian topologies support evidence that the Hyainailourinae, Apterodontinae, and Teratodontinae all had Afro-Arabian origins. Hyaenodonts made their first appearances in Europe in terms of the Mammal Paleogene zones

The Mammal Paleogene zones or MP zones are a system of biostratigraphic zones in the stratigraphic record used to correlate mammal-bearing fossil localities of the Paleogene period of Europe. It consists of thirty consecutive zones (numbered MP 1 ...

by MP7 (or early Eocene), mostly predominantly the Proviverrinae. In terms of carnivorous mammal assemblages of Europe, MP8-MP10 marked the extinctions of the Viverravidae

Viverravidae ("ancestors of viverrids") is an extinct monophyletic family of mammals from extinct superfamily Viverravoidea within the clade Carnivoramorpha, that lived from the early Palaeocene to the late Eocene in North America, Europe and A ...

, Oxyaenidae, Sinopinae, and Mesonychidae

Mesonychidae (meaning "middle claws") is an extinct family of small to large-sized omnivorous- carnivorous mammals. They were endemic to North America and Eurasia during the Early Paleocene to the Early Oligocene, and were the earliest group o ...

. As a result, the endemic hyaenodonts and carnivoraforms remained the two only carnivorous mammal groups for much of the Eocene of Europe. Hyaenodonts were more diverse than carnivoraforms for much of the Eocene and increased in diversity with the appearances of the hyainailourines in MP16 and hyaenodontines in MP17A. The former group likely dispersed from Africa while the latter may have dispersed from Asia. Compared to the proviverrines which never exceeded , the hyainailourines were much larger in size.

''Pterodon'' as defined ''sensu lato'' (in a loose sense) is polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

when including species other than ''P. dasyuroides''. This is because ''P. dasyuroides'' does not form a natural clade with non-European species classified within the genus, therefore meaning that they are pending reassessments to other genera. ''Pterodon'' ''sensu stricto'' (in a strict sense) made its appearance in western Europe by MP18 (late Eocene) in the form of ''P. dasyuroides'' and lasted up to MP20. ''P. dasyuroides'' was likely part of a ghost lineage of dispersing hyainailourines from Africa, and '' Kerberos'' did not appear to have descended into ''Pterodon'' or '' Parapterodon''.

The phylogenetic tree for the superfamily Hyainailouroidea within the order Hyaenodonta as created by Floréal Solé et al. in 2021 is outlined below:

Description

Skull

The order Hyaenodonta is diagnosed as having an elongated and narrow skull with a narrow cranial base (basicranium), a high and narrow

The order Hyaenodonta is diagnosed as having an elongated and narrow skull with a narrow cranial base (basicranium), a high and narrow occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

, and a transversely constricted interorbital region

The interorbital region of the skull is located between the eyes, anterior to the braincase. The form of the interorbital region may exhibit significant variation between taxonomic groups.

In oryzomyine rodents, for example, the width, form, and ...

. Within the order, members of the Hyainailouridae share traits including a proportionally massive skull with an absence of any suture between the parietal bone

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

and frontal bone

In the human skull, the frontal bone or sincipital bone is an unpaired bone which consists of two portions.'' Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bo ...

, and a weak postorbital process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

(or projection), an extended pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal specie ...

in its underside and side areas, the presence of a preglenoid crest, and side expansions of the squamosal

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestra ...

relative to the back position of the zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of temporal bone, zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the ...

.

The skull of ''P. dasyuroides'' (specimen Qu8301, National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History ( ; abbr. MNHN) is the national natural history museum of France and a of higher education part of Sorbonne University. The main museum, with four galleries, is located in Paris, France, within the ...

) was described by Lange-Badré in 1979 as retaining proportions similar to members of the Proviverrinae, its maximum height barely reaching a third of its maximum length because of a lack of elevation of the cranial vault

The cranial vault is the space in the skull within the neurocranium, occupied by the brain.

Development

In humans, the cranial vault is imperfectly composed in newborns, to allow the large human head to pass through the birth canal. During bir ...

. The muzzle is narrow and cylindrical in shape, barely projecting at the level of the roots of the canines. The cranium

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

is equally as narrow, is shaped like an hourglass, and is shorter than the facial skeleton

The facial skeleton comprises the ''facial bones'' that may attach to build a portion of the skull. The remainder of the skull is the neurocranium.

In human anatomy and development, the facial skeleton is sometimes called the ''membranous visc ...

. The known skull measures in length, and it is similar to that of ''Kerberos'' in being elongated and having a long rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

and neurocranium

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the cal ...

. It is one of the two only known Eocene hyainailourine genera to be known by skull material, the other being ''Kerberos''.

In the upper view of the skull, the nasals are convex dorsally (top area in the case of the skull) and extend far into the back beyond the front edge of the orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

. A short tubercle

In anatomy, a tubercle (literally 'small tuber', Latin for 'lump') is any round nodule, small eminence, or warty outgrowth found on external or internal organs of a plant or an animal.

In plants

A tubercle is generally a wart-like projectio ...

emerges from the nasals into the lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bones are two small and fragile bones of the facial skeleton; they are roughly the size of the little fingernail and situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. They each have two surfaces and four borders. Several bon ...

, and then the nasals come into contact with the frontal bone by a W-shaped suture. The frontal eminence

A frontal eminence (or ''tuber frontale'') is either of two rounded elevations on the frontal bone of the skull. They lie about 3 cm above the supraorbital margin on each side of the frontal suture. They are the site of ossification

Ossific ...

s of the frontal bone, or the rounded elevations of the front of the upper skull, are not very prominent based on the weak depressions that are widely open. The skull lacks any postorbital process

The postorbital process is a projection on the frontal bone near the rear upper edge of the eye socket. In many mammals, it reaches down to the zygomatic arch, forming the postorbital bar.

References

See also

* Orbital process

In the human s ...

projections within its front area. The blunt brow ridge

The brow ridge, or supraorbital ridge known as superciliary arch in medicine, is a bony ridge located above the eye sockets of all primates and some other animals. In humans, the eyebrows are located on their lower margin.

Structure

The brow ri ...

s arise back from the upper edge of the orbits as triangular-shaped roughnesses and arrive at the sagittal plane

The sagittal plane (; also known as the longitudinal plane) is an anatomical plane that divides the body into right and left sections. It is perpendicular to the transverse and coronal planes. The plane may be in the center of the body and divi ...

area in front of the post-orbital constriction

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets (the orbits, hence the name) found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-hu ...

. The coronal suture

The coronal suture is a dense, fibrous connective tissue joint that separates the two parietal bones from the frontal bone of the skull.

Structure

The coronal suture lies between the paired parietal bones and the frontal bone of the skull ...

is destroyed in known specimens and therefore has an unknown position relative to the post-orbital constriction. The cranial vault is formed by the two parietal bones, and is gradually detached from the high and thin sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

, which meets with the supraoccipital crest and forms a small triangular facet. The maximum width of the cranium barely exceeds that of the frontal bones at the upper edges of the orbits.

In a lateral (or side) view, the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

e are short and extend a small distance between the nasals and maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

e, slightly preceding the canines. Their thick upper front edges form a roughly heart-shaped and subvertical nasal opening with a maximum width at the level of the nasal premaxillary suture. There is a slight projection of the root of the canine on the upper maxilla which is followed by an elongated depression that precedes that the long, narrow opening of the infraorbital canal

The infraorbital canal is a canal found at the base of the orbit that opens on to the maxilla. It is continuous with the infraorbital groove and opens onto the maxilla at the infraorbital foramen. The infraorbital nerve and infraorbital artery t ...

. The lacrimal bone extends widely onto the face in a large semicircle shape which restricts frontal-maxillary contact. There is no lacrimal tubercle

The lateral margin of the groove of the frontal process of the maxilla is named the anterior lacrimal crest, and is continuous below with the orbital margin; at its junction with the orbital surface is a small tubercle, the lacrimal tubercle, whi ...

present in the skull. The squamosal suture

The squamosal suture, or squamous suture, arches backward from the pterion and connects the temporal squama with the lower border of the parietal bone: this suture is continuous behind with the short, nearly horizontal parietomastoid suture, wh ...

is low in position, not very convex, and is very inclined towards the zygomatic arches, explaining the triangular cross section of the skull. The squamosal roots of the zygomatic arches are found in a completely marginal position and, unlike modern carnivora

Carnivora ( ) is an order of placental mammals specialized primarily in eating flesh, whose members are formally referred to as carnivorans. The order Carnivora is the sixth largest order of mammals, comprising at least 279 species. Carnivor ...

ns, are not under the temporal wall of the skull but outside it. The mastoid part of the temporal bone

The mastoid part of the temporal bone is the posterior (back) part of the temporal bone, one of the bones of the skull. Its rough surface gives attachment to various muscles (via tendons) and it has openings for blood vessels. From its borders, t ...

is between the retrotympanic part of the squamosal and the paroccipital process of the exoccipital region. While the zygomatic arches were not completely preserved in ''P. dasyuroides'', those of the related ''Apterodon macrognathus'' and ''Kerberos langebadreae'' are dorsoventrally deep for robustness to support masseter muscle

In anatomy, the masseter is one of the muscles of mastication. Found only in mammals, it is particularly powerful in herbivores to facilitate chewing of plant matter. The most obvious muscle of mastication is the masseter muscle, since it is the ...

s.

The face of the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

is narrow and has a fan-like shape due to the strong narrowing at the level of the supraoccipital-squamosal suture followed by a strongly concave squamous part of the occipital bone. Due to this development, it differs strongly from that of ''Hyaenodon'' but is comparable to that of ''Apterodon''.

Typical of mammals with elongated snouts, the lower edge of the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

(specimen Qu8636, National Museum of Natural History, France) is slightly curved. After the receding mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral ha ...

region, the mandible is rectilinear without any change in shape in the preangular region. The angle of the mandible

__NOTOC__

The angle of the mandible (a.k.a. gonial angle, Masseteric Tuberosity, and Masseteric Insertion) is located at the posterior border at the junction of the lower border of the ramus of the mandible.

The angle of the mandible, which may ...

is short and stocky for which the medial pterygoid muscle

The medial pterygoid muscle (or internal pterygoid muscle) is a thick, quadrilateral muscle of the face. It is supplied by the mandibular branch of the trigeminal nerve (V). It is important in mastication (chewing).

Structure

The medial pter ...

would have connected to.

Endocast anatomy

''P. dasyuroides'' is known by a brain endocast, which was first described by Jean Piveteau in 1935. The natural endocast is stored at the National Museum of Natural History, France with no catalogue number. It is estimated to have an endocast volume of . Only limited morphologies can be observed as that of the surface was not well-preserved. The endocast shape reflects well the general appearance of the rectilinear sagittal profile of the skull. There is an absence of any form of occipital tilt, and the brain endocast is made up of theolfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OF ...

s, the cerebrum

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfac ...

, and the cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

. The back view of an artificial endocast as studied by Lange-Badré reveals that it has a triangular to ovate shape, with its olfactory bulbs as its top part and the cerebellar hemispheres. The maximum height of the brain cast is at the level of the cerebellum. Overall, the molding appears low in position, the cerebellum taking up a large volume of it compared to the cerebrum.

The olfactory lobes, the structures involved in the sense of smell, are not covered by the cerebral hemisphere

The vertebrate cerebrum (brain) is formed by two cerebral hemispheres that are separated by a groove, the longitudinal fissure. The brain can thus be described as being divided into left and right cerebral hemispheres. Each of these hemispheres ...

s and diverge from each other somewhat. It is detached from the structures of the olfactory nerve

The olfactory nerve, also known as the first cranial nerve, cranial nerve I, or simply CN I, is a cranial nerve that contains sensory nerve fibers relating to the sense of smell.

The afferent nerve fibers of the olfactory receptor neurons t ...

which crossed into the cribriform plate

In mammalian anatomy, the cribriform plate (Latin for lit. '' sieve-shaped''), horizontal lamina or lamina cribrosa is part of the ethmoid bone. It is received into the ethmoidal notch of the frontal bone and roofs in the nasal cavities. It s ...

of the ethmoid bone

The ethmoid bone (; from ) is an unpaired bone in the skull that separates the nasal cavity from the brain. It is located at the roof of the nose, between the two orbits. The cubical (cube-shaped) bone is lightweight due to a spongy constructi ...

. The olfactory peduncle

The olfactory tract (olfactory peduncle or olfactory stalk) is a bilateral bundle of afferent nerve fibers from the mitral and tufted cells of the olfactory bulb that connects to several target regions in the brain, including the piriform cor ...

s attach the olfactory bulbs to the non-prominent olfactory tubercle

The olfactory tubercle (OT), also known as the tuberculum olfactorium, is a multi-sensory processing center that is contained within the olfactory cortex and ventral striatum and plays a role in reward cognition. The OT has also been shown to ...

s. Within the rhinencephalon, the piriform cortex

The piriform cortex, or pyriform cortex, is a region in the brain, part of the rhinencephalon situated in the cerebrum. The function of the piriform cortex relates to the sense of smell.

Structure

The piriform cortex is part of the rhinencephal ...

is the most voluminous section, appearing folded under the neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

and having a compact shape.

The neocortex of ''P. dasyuroides'' is more developed compared to the earlier hyaenodontid ''Cynohyaenodon

''Cynohyaenodon'' ("dog-like ''Hyaenodon''") is an extinct paraphyletic genus of placental mammals from extinct family Hyaenodontidae that lived from the early to middle Eocene in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the North ...

cayluxi'' because of the lower positions of the rhinals and the larger number of sulci

Sulci or Sulki (in Greek , Stephanus of Byzantium, Steph. B., Ptolemy, Ptol.; , Strabo; , Pausanias (geographer), Paus.), was one of the most considerable cities of ancient Sardinia, situated in the southwest corner of the island, on a small isla ...

(or furrows). The cerebral hemispheres are separated from the cerebellum by a large gap and, in the front area of the brain, do not cover the olfactory bulbs. The neocortex is unremarkable and only in front of the piriform lobe. ''P. dasyuroides'' may have had five neopallium fissures, including a lateral sulcus

The lateral sulcus (or lateral fissure, also called Sylvian fissure, after Franciscus Sylvius) is the most prominent sulcus (neuroanatomy), sulcus of each cerebral hemisphere in the human brain. The lateral sulcus (neuroanatomy), sulcus is a deep ...

, a suprasylvia preceded by a coronal or Y-shaped furrow, and a possible postsylvia. ''P. dasyuroides'' was previously thought to have had a primitive, simple, two-furrowed neocortex, which Lange-Badré concluded was incorrect because of the significant development of the neocortex itself and the lower position of the rhinals compared to ''Cynohyaenodon''.

Therese Flink et al. in 2021 discussed how palaeontologists interpreted the endocast of ''P. dasyuroides'', stating while Piveteau in 1935 and Lange-Badré in 1979 thought that the midbrain

The midbrain or mesencephalon is the uppermost portion of the brainstem connecting the diencephalon and cerebrum with the pons. It consists of the cerebral peduncles, tegmentum, and tectum.

It is functionally associated with vision, hearing, mo ...

was exposed, Leonard Radinsky in 1977 suggested that instead, the neocortex's edge reached the cerebellum and olfactory bulbs. After a reexamination of the natural endocast, Flink et al. were inclined to agree with the latter view and stated that if there truly was any midbrain exposure, it would not have been well-pronounced in comparison to the other hyaenodonts '' Thinocyon velox'' or '' Proviverra typica''.

The cerebellum is bulky compared to the front portion of the cerebrum because the former's cavity is not as large as the cerebral fossa and lack of coverage by the neocortex. The cerebellum appears higher in position than the cerebrum, and the cerebellar vermis

The cerebellar vermis (from Latin ''vermis,'' "worm") is located in the medial, cortico-nuclear zone of the cerebellum, which is in the posterior cranial fossa, posterior fossa of the cranium. The primary fissure in the vermis curves ventrolatera ...

strongly projects between the cerebellum's two hemispheres. The primary fissure of the cerebellum, located on the paleocerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

-neocerebellum

The posterior lobe of cerebellum or neocerebellum is one of the lobes of the cerebellum, below the primary fissure. The posterior lobe is much larger than anterior lobe. The anterior lobe is separated from the posterior lobe by the primary fissu ...

boundary, is in a backwards position, more so than certain "condylarth

Condylarthra is an informal group – previously considered an Order (biology), order – of extinct placental mammals, known primarily from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. They are considered early, primitive ungulates and is now largely consid ...

s" such as ''Arctocyon

''Arctocyon'' (from Greek ''arktos'' and ''kyôn'', "bear/dog-like") is an extinct genus of large placental mammals, part of the possibly polyphyletic family Arctocyonidae. The type species is ''A. primaevus'', though up to five other species may ...

'' and ''Pleuraspidotherium

''Pleuraspidotherium'' is an extinct genus of condylarth of the family Pleuraspidotheriidae, whose fossils have been found in the Late Paleocene Marnes de Montchenot of France and the Tremp Formation of modern Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom ...

''. There is no other known transverse furrow on the cerebellar vermis.

Dentition

The subfamily Hyainailourinae within the family Hyainailouridae is diagnosed in the upper dentition as having high and secant-shaped paraconid cusps and cone-shaped metacone and paracone cusps on the M1-M2 molars, a weak to absent P3 lingual cingulum, and a lack of any continuous lingual cingulum on P4. For lower dentition, the M3 talonid cusp is reduced compared to those on M1-M2, and the protoconid and paraconid cusps are roughly equal in length in the molars.

''Pterodon'' ''sensu lato'' is diagnosed in its dental differences with other hyainailourid genera. It differs from ''Metapterodon'' in being larger, the presence of an M3 talonid cusp, larger M1-M2 tanolid cusps, narrower upper molars with shorter metastyle ridges, and an incomplete paracone-metacone cusp fusion. It differs also from ''Akhnatenavus'' in the talonid cusps of the molars being as wide as its trigonid cusps, roughly equal sizes of the protoconid and paraconid cusp sizes in the molars, unreduced premolar sizes, and a lack of diastemata for premolar spaces. ''Pterodon'' differs from ''Hyainailouros'' and ''

The subfamily Hyainailourinae within the family Hyainailouridae is diagnosed in the upper dentition as having high and secant-shaped paraconid cusps and cone-shaped metacone and paracone cusps on the M1-M2 molars, a weak to absent P3 lingual cingulum, and a lack of any continuous lingual cingulum on P4. For lower dentition, the M3 talonid cusp is reduced compared to those on M1-M2, and the protoconid and paraconid cusps are roughly equal in length in the molars.

''Pterodon'' ''sensu lato'' is diagnosed in its dental differences with other hyainailourid genera. It differs from ''Metapterodon'' in being larger, the presence of an M3 talonid cusp, larger M1-M2 tanolid cusps, narrower upper molars with shorter metastyle ridges, and an incomplete paracone-metacone cusp fusion. It differs also from ''Akhnatenavus'' in the talonid cusps of the molars being as wide as its trigonid cusps, roughly equal sizes of the protoconid and paraconid cusp sizes in the molars, unreduced premolar sizes, and a lack of diastemata for premolar spaces. ''Pterodon'' differs from ''Hyainailouros'' and ''Megistotherium

''Megistotherium'' is an extinct genus of hyaenodont belonging to the family Hyainailouridae that lived in Africa and possibly Asia as well. It first appeared in Early Miocene to late Middle Miocene from 22.5 to 12.0 million years ago, existing ...

'' by its smaller size and larger talonids on its lower molars. The diagnosis reflects the inclusion of other species included in ''Pterodon'' outside of the type species. ''P. dasyuroides'' differs from ''Kerberos'' by smaller-sized P1 and P1 premolars, a reduced number of upper incisors, a smaller protocone cusp on P3, and smaller size. ''P. dasyuroides'' is also described as having a dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of . There is no evidence of any sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

based on dentition.

In the upper dentition, the two incisors, conical in shape, are unequal in size, the central incisor being twice or thrice as large as the lateral incisor. Their shapes suggest that they play a role in piercing through food rather than cutting them. The upper canines, although much larger than other teeth of the upper dental row, are not as strong as those of extant

In the upper dentition, the two incisors, conical in shape, are unequal in size, the central incisor being twice or thrice as large as the lateral incisor. Their shapes suggest that they play a role in piercing through food rather than cutting them. The upper canines, although much larger than other teeth of the upper dental row, are not as strong as those of extant hyena

Hyenas or hyaenas ( ; from Ancient Greek , ) are feliform carnivoran mammals belonging to the family Hyaenidae (). With just four extant species (each in its own genus), it is the fifth-smallest family in the order Carnivora and one of the sma ...

s, as they are less robust in relation to the skull. P1 is small-sized, lacks any cingulate prominence except the anterior-lingual region where it connects with a ridge from the top of a cusp, and is formed by a conical cusp with a back half that is stretched into a lower edge. P2 is similar to P1 in shape; its hook shape in its main cusp is prominent, and the cingulum runs from the ridges over the entire lingual surface. P3 differs from the two other premolars by the top of the main cusp occupying a median position. The P4 has a lingual expansion of the median area of the paraconid cusp but is difficult to distinguish by itself from the P4 of ''Hyaenodon requieni''. The first two upper molars have compressed and stretched metastyle ridges for a bladelike appearance that makes carnivorous diets unambiguous. The shapes of the two molars are of a right triangle with a front (anterior) base, and the first is smaller and more conservative in cuspid development than the second. M3 is wider than it is long and comes in two variants: it is either as wide as the two molars that precede it or is narrower than the two other molars and is stockier than the other variant.

In terms of the lower dentition, there are 8-9 teeth, meaning a reduction in dentition compared to primitive placental mammals. The known individual specimens from Quercy only show one pair of lower incisors, which are rarely preserved and are thick with flat wear. Similar to the upper canines, the lower canines are long, slender, and not very curved. The P1 is most often absent in development, although one specimen reveals one on the left side but not right of a mandible while another has them on both sides. It is a conical, short, and thick tooth with no distal stretching and two roots fused into one. P2-P3 have low and stubby crowns while P4 is high and long, its height being 1.5 to 2 times that of P3. The M1, rarely adequately preserved, is subject to early and severe wear that levels the trigonid and talonid cusps, likely caused by frequent maximum-force occlusion with P4. The M2 and M3, despite the disappearance of the metaconid cusp and the receded talonid cusp, are thick and not very sharp. The protoconid cusp is slender and is the dominant cusp within the last two molars. M3 differs from M2 by being larger in size and the smaller, triangular-shaped talonid cusp.

Postcranial remains

''P. dasyuroides'' is known by very few postcranial remains, which themselves currently have no known whereabouts. Blainville illustrated postcranial remains designated to "''Taxotherium parisiense''" in 1841, but only theulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

and fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

were referenced as belonging to ''P. dasyuroides'' by later palaeontologists like Léonard Ginsburg in 1980, leaving the taxonomic statuses of the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

, carpals + metacarpals

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular skeleton, appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones (wrist, wris ...

, astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

, and calcaneus

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel; : calcanei or calcanea) or heel bone is a bone of the Tarsus (skeleton), tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other ...

ambiguous, especially since ''Taxotherium'' was synonymized with ''Hyaenodon''.

According to Ginsburg, the ulna of ''Hyainailouros sulzeri'' is arched and has a high plus well-developed olecranon

The olecranon (, ), is a large, thick, curved bony process on the proximal, posterior end of the ulna. It forms the protruding part of the elbow and is opposite to the cubital fossa or elbow pit (trochlear notch). The olecranon serves as a lever ...

(bony prominence on the elbow) and a long and strong diaphysis

The diaphysis (: diaphyses) is the main or midsection (shaft) of a long bone. It is made up of cortical bone and usually contains bone marrow and adipose tissue (fat).

It is a middle tubular part composed of compact bone which surrounds a centr ...

up to the distal end of the bone. The olecranon of ''H. sulzeri'' is long compared to those of carnivorans and it in a back position similar to artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s. The antero-external tubercle is diminished while the antero-internal tubercle well-developed, a trait Ginsburg said was also found to be similar to a sketched ulna of ''P. dasyuroides'' by Blainville in 1841. The fibula of ''H. sulzeri'' was described as being thicker in comparison to carnivorans, with the diaphysis being twice as antero-posteriorly elongated in its distal area as its proximal area. The fibula's astragalus surface being wide and long is similar to that of ''P. dasyuroides'' as also depicted by Blainville.

Size

In 1977, Radinsky made early size estimates for hyaenodonts with known skeletons and no known complete which he based size estimates off of other "creodonts." He estimated that ''P. dasyuroides'' had an estimated body length range of - and an estimated body weight range of -. However, due to the proportions of hyaenodonts being different from extant carnivorans, estimated values of them may not reflect their actual sizes.

Estimating the body sizes of hyaenodonts has proven difficult because they are extinct and have no modern analogues, plus dentally or cranially derived body sizes based on extant carnivorans are problematic since they have large crania in comparison to carnivorans, which produce unreasonably large estimated size values. As a result, hyaenodonts are measured more based on body mass and not estimated body size.

In 2015, Solé et al. estimated that based on the length of M1-M3 being , it may have weighed . Hyainailourids have been known for growing to typically larger sizes compared to other hyaenodonts, including the Paleogene and especially the Miocene. The estimated weight values for ''P. dasyuroides'' and other studied hyaenodonts remained unchanged in a 2020 paper by Solé et al.

In 1977, Radinsky made early size estimates for hyaenodonts with known skeletons and no known complete which he based size estimates off of other "creodonts." He estimated that ''P. dasyuroides'' had an estimated body length range of - and an estimated body weight range of -. However, due to the proportions of hyaenodonts being different from extant carnivorans, estimated values of them may not reflect their actual sizes.

Estimating the body sizes of hyaenodonts has proven difficult because they are extinct and have no modern analogues, plus dentally or cranially derived body sizes based on extant carnivorans are problematic since they have large crania in comparison to carnivorans, which produce unreasonably large estimated size values. As a result, hyaenodonts are measured more based on body mass and not estimated body size.

In 2015, Solé et al. estimated that based on the length of M1-M3 being , it may have weighed . Hyainailourids have been known for growing to typically larger sizes compared to other hyaenodonts, including the Paleogene and especially the Miocene. The estimated weight values for ''P. dasyuroides'' and other studied hyaenodonts remained unchanged in a 2020 paper by Solé et al.

Palaeobiology

The order Hyaenodonta occupied a wide range of body sizes/body masses and ranged from mesocarnivorous to

The order Hyaenodonta occupied a wide range of body sizes/body masses and ranged from mesocarnivorous to hypercarnivorous

A hypercarnivore is an animal that has a diet that is more than 70% meat, either via active predation or by scavenging. The remaining non-meat diet may consist of non-animal foods such as fungi, fruits or other plant material. Some extant example ...

diets. The Hyainailourinae, which includes ''P. dasyuroides'', was one hyaenodont lineage that gained hypercarnivorous adaptations given its various specific dental configurations. The diets of pan-carnivorans like ''P. dasyuroides'' were also inferred from Hunter-Schreger bands (HSB) on the tooth enamel

Tooth enamel is one of the four major Tissue (biology), tissues that make up the tooth in humans and many animals, including some species of fish. It makes up the normally visible part of the tooth, covering the Crown (tooth), crown. The other ...

s of placental mammals. ''P. dasyuroides'' and some other hyaenodonts have only zigzag HSB patterns, patterns observed in extant carnivorans with high bite force

Bite force quotient (BFQ) is a numerical value commonly used to represent the bite force of an animal adjusted for its body mass, while also taking factors like the allometry effects.

The BFQ is calculated as the regression of the quotient of an ...

s due to adaptations for bone-crushing since the zigzag HSBs render the enamel resistant to tensile stress. Because of its overall dentition morphology, ''P. dasyuroides'' is thought to have had adaptations to both meat cutting and bone crushing, the latter trait being shared with other later hyaenodonts.

Due to an overall lack of postcranial remains known for ''P. dasyuroides'' in the modern day, the locomotion of the Paleogene hyainailourid is unknown. In comparison, adequate postcranial remains are known for ''Hyainailouros sulzeri'', ''Kerberos langebadreae'', and ''Simbakubwa kutokaafrika'', allowing for determinations of the locomotion methods of the hyainailourids. The elbow of ''H. sulzeri'' reveals incapability of flexible pronation-supination movements compared to typical cursorial mammals. The angulations and lengths of the fingers in relation to the metapodial

Metapodials are long bone

The long bones are those that are longer than they are wide. They are one of five types of bones: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones, especially the femur and tibia, are subjected to most of the l ...

bones, and the relation of the radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

to the ulna suggest digitigrade movements of the forelimbs. The hindlimbs indicate similar results of digitigrade movement but, according to Ginsburg, have remnant traits of ancestral plantigrade movement. He theorized that it may have been semi-digitigrade overall with capabilities of leaping and occasional plantigrade movement. Similar traits of semi-digitigrady were also observed in ''S. kutokaafrika'', with no capability of full digitigrade movement. Such adaptations of Miocene hyainailourines were likely the result of responses to more open environments.

In comparison, however, the Paleogene hyainailourid ''Kerberos'' shows plantigrade stances and terrestrial locomotion based on known postcranial evidence. The locomotion method made it differ from the more cursorial hyaenodontid ''Hyaenodon'' as well as hyaenids and borophagine

The extinct Borophaginae form one of three subfamily, subfamilies found within the Canidae, canid family. The other two canid subfamilies are the extinct Hesperocyoninae and extant Caninae. Borophaginae, called "bone-crushing dogs", were endemic ...