Proteolytic on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Proteolysis is the breakdown of

Proteolysis is the breakdown of

The intracellular degradation of protein may be achieved in two ways—proteolysis in

The intracellular degradation of protein may be achieved in two ways—proteolysis in

Research on Biological Roles and Variation of Snake Venoms.

Loma Linda University. including effects that are: * cytotoxic (cell-destroying) * hemotoxic (blood-destroying) * myotoxic (muscle-destroying) * hemorrhagic (bleeding)

The Journal of Proteolysis

is an open access journal that provides an international forum for the electronic publication of the whole spectrum of high-quality articles and reviews in all areas of proteolysis and proteolytic pathways.

Proteolysis MAP from Center on Proteolytic Pathways

{{Authority control Post-translational modification Metabolism EC 3.4

protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s into smaller polypeptide

Peptides are short chains of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. A polypeptide is a longer, continuous, unbranched peptide chain. Polypeptides that have a molecular mass of 10,000 Da or more are called proteins. Chains of fewer than twenty ...

s or amino acids

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the Proteinogenic amino acid, 22 α-amino acids incorporated into p ...

. Protein degradation is a major regulatory mechanism of gene expression and contributes substantially to shaping mammalian proteomes. Uncatalysed, the hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

of peptide bonds is extremely slow, taking hundreds of years. Proteolysis is typically catalysed by cellular enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s called protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s, but may also occur by intra-molecular digestion.

Proteolysis in organisms serves many purposes; for example, digestive enzymes break down proteins in food to provide amino acids for the organism, while proteolytic processing of a polypeptide chain after its synthesis may be necessary for the production of an active protein. It is also important in the regulation of some physiological and cellular processes including apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, as well as preventing the accumulation of unwanted or misfolded proteins in cells. Consequently, abnormality in the regulation of proteolysis can cause diseases.

Proteolysis can also be used as an analytical tool for studying proteins in the laboratory, and it may also be used in industry, for example in food processing and stain removal.

Biological functions

Post-translational proteolytic processing

Limited proteolysis of a polypeptide during or aftertranslation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

in protein synthesis often occurs for many proteins. This may involve removal of the N-terminal methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans.

As the precursor of other non-essential amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine play ...

, signal peptide

A signal peptide (sometimes referred to as signal sequence, targeting signal, localization signal, localization sequence, transit peptide, leader sequence or leader peptide) is a short peptide (usually 16–30 amino acids long) present at the ...

, and/or the conversion of an inactive or non-functional protein to an active one. The precursor to the final functional form of protein is termed proprotein, and these proproteins may be first synthesized as preproprotein. For example, albumin is first synthesized as preproalbumin and contains an uncleaved signal peptide. This forms the proalbumin after the signal peptide is cleaved, and a further processing to remove the N-terminal 6-residue propeptide yields the mature form of the protein.

Removal of N-terminal methionine

The initiating methionine (and, in bacteria, fMet) may be removed during translation of the nascent protein. For '' E. coli'', fMet is efficiently removed if the second residue is small and uncharged, but not if the second residue is bulky and charged. In bothprokaryotes

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

and eukaryotes

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of ...

, the exposed N-terminal residue may determine the half-life of the protein according to the N-end rule The ''N''-end rule is a rule that governs the rate of proteolysis, protein degradation through recognition of the N-terminal residue of proteins. The rule states that the N-terminus, ''N''-terminal amino acid of a protein determines its half-life (t ...

.

Removal of the signal sequence

Proteins that are to be targeted to a particular organelle or for secretion have an N-terminalsignal peptide

A signal peptide (sometimes referred to as signal sequence, targeting signal, localization signal, localization sequence, transit peptide, leader sequence or leader peptide) is a short peptide (usually 16–30 amino acids long) present at the ...

that directs the protein to its final destination. This signal peptide is removed by proteolysis after their transport through a membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

.

Cleavage of polyproteins

Some proteins and most eukaryotic polypeptide hormones are synthesized as a large precursor polypeptide known as a polyprotein that requires proteolytic cleavage into individual smaller polypeptide chains. The polyproteinpro-opiomelanocortin

Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) is a precursor polypeptide with 241 amino acid residues. POMC is Protein biosynthesis, synthesized in Corticotropic cell, corticotrophs of the anterior pituitary from the 267-amino-acid-long Precursor polypeptide, pol ...

(POMC) contains many polypeptide hormones. The cleavage pattern of POMC, however, may vary between different tissues, yielding different sets of polypeptide hormones from the same polyprotein.

Many viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are found in almo ...

also produce their proteins initially as a single polypeptide chain that were translated from a polycistronic mRNA. This polypeptide is subsequently cleaved into individual polypeptide chains. Common names for the polyprotein include ''gag'' ( group-specific antigen) in retroviruses and '' ORF1ab'' in Nidovirales. The latter name refers to the fact that a slippery sequence in the mRNA that codes for the polypeptide causes ribosomal frameshifting, leading to two different lengths of peptidic chains (''a'' and ''ab'') at an approximately fixed ratio.

Cleavage of precursor proteins

Many proteins and hormones are synthesized in the form of their precursors - zymogens,proenzyme

In biochemistry, a zymogen (), also called a proenzyme (), is an inactive precursor of an enzyme. A zymogen requires a biochemical change (such as a hydrolysis reaction revealing the active site, or changing the configuration to reveal the acti ...

s, and prehormones. These proteins are cleaved to form their final active structures. Insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

, for example, is synthesized as preproinsulin, which yields proinsulin after the signal peptide has been cleaved. The proinsulin is then cleaved at two positions to yield two polypeptide chains linked by two disulfide bonds. Removal of two C-terminal residues from the B-chain then yields the mature insulin. Protein folding

Protein folding is the physical process by which a protein, after Protein biosynthesis, synthesis by a ribosome as a linear chain of Amino acid, amino acids, changes from an unstable random coil into a more ordered protein tertiary structure, t ...

occurs in the single-chain proinsulin form which facilitates formation of the ultimate inter-peptide disulfide bonds, and the ultimate intra-peptide disulfide bond, found in the native structure of insulin.

Proteases in particular are synthesized in the inactive form so that they may be safely stored in cells, and ready for release in sufficient quantity when required. This is to ensure that the protease is activated only in the correct location or context, as inappropriate activation of these proteases can be very destructive for an organism. Proteolysis of the zymogen yields an active protein; for example, when trypsinogen is cleaved to form trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

, a slight rearrangement of the protein structure that completes the active site of the protease occurs, thereby activating the protein.

Proteolysis can, therefore, be a method of regulating biological processes by turning inactive proteins into active ones. A good example is the blood clotting cascade whereby an initial event triggers a cascade of sequential proteolytic activation of many specific proteases, resulting in blood coagulation. The complement system

The complement system, also known as complement cascade, is a part of the humoral, innate immune system and enhances (complements) the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear microbes and damaged cells from an organism, promote inf ...

of the immune response also involves a complex sequential proteolytic activation and interaction that result in an attack on invading pathogens.

Protein degradation

Protein degradation may take place intracellularly or extracellularly. In digestion of food, digestive enzymes may be released into the environment for extracellular digestion whereby proteolytic cleavage breaks proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids so that they may be absorbed and used. In animals the food may be processed extracellularly in specialized organs or guts, but in many bacteria the food may be internalized viaphagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

. Microbial degradation of protein in the environment can be regulated by nutrient availability. For example, limitation for major elements in proteins (carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur) induces proteolytic activity in the fungus '' Neurospora crassa'' as well as in of soil organism communities.

Proteins in cells are broken into amino acids. This intracellular degradation of protein serves multiple functions: It removes damaged and abnormal proteins and prevents their accumulation. It also serves to regulate cellular processes by removing enzymes and regulatory proteins that are no longer needed. The amino acids may then be reused for protein synthesis.

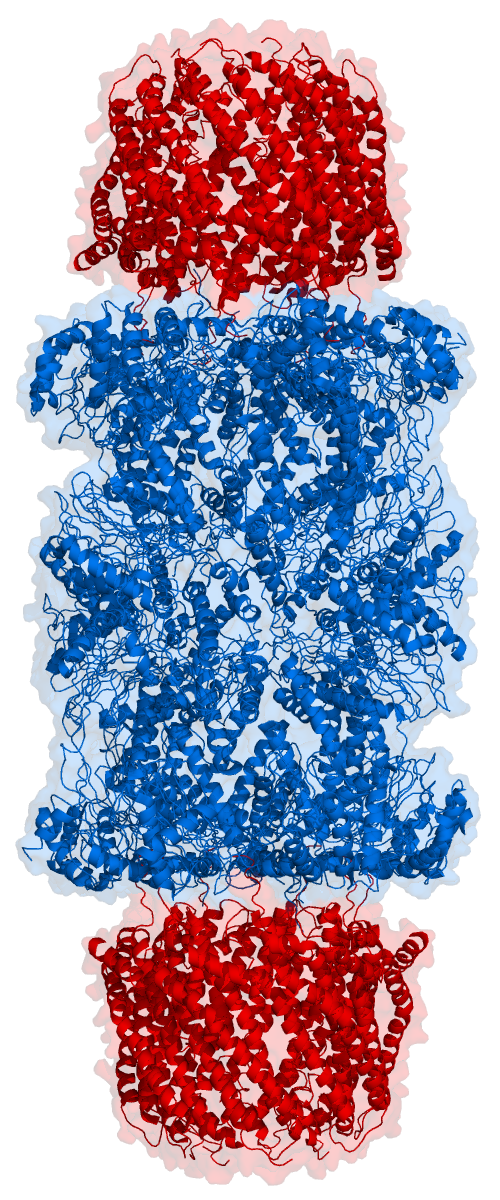

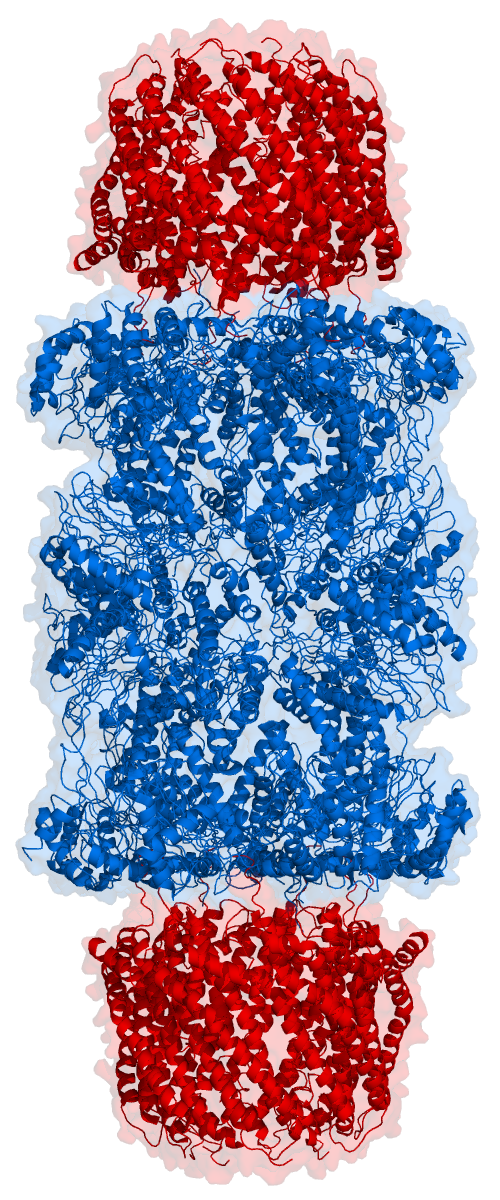

Lysosome and proteasome

The intracellular degradation of protein may be achieved in two ways—proteolysis in

The intracellular degradation of protein may be achieved in two ways—proteolysis in lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

, or a ubiquitin-dependent process that targets unwanted proteins to proteasome. The autophagy

Autophagy (or autophagocytosis; from the Greek language, Greek , , meaning "self-devouring" and , , meaning "hollow") is the natural, conserved degradation of the cell that removes unnecessary or dysfunctional components through a lysosome-depe ...

-lysosomal pathway is normally a non-selective process, but it may become selective upon starvation whereby proteins with peptide sequence KFERQ or similar are selectively broken down. The lysosome contains a large number of proteases such as cathepsins.

The ubiquitin-mediated process is selective. Proteins marked for degradation are covalently linked to ubiquitin. Many molecules of ubiquitin may be linked in tandem to a protein destined for degradation. The polyubiquinated protein is targeted to an ATP-dependent protease complex, the proteasome. The ubiquitin is released and reused, while the targeted protein is degraded.

Rate of intracellular protein degradation

Different proteins are degraded at different rates. Abnormal proteins are quickly degraded, whereas the rate of degradation of normal proteins may vary widely depending on their functions. Enzymes at important metabolic control points may be degraded much faster than those enzymes whose activity is largely constant under all physiological conditions. One of the most rapidly degraded proteins is ornithine decarboxylase, which has a half-life of 11 minutes. In contrast, other proteins likeactin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ...

and myosin

Myosins () are a Protein family, family of motor proteins (though most often protein complexes) best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are adenosine triphosphate, ATP- ...

have a half-life of a month or more, while, in essence, haemoglobin

Hemoglobin (haemoglobin, Hb or Hgb) is a protein containing iron that facilitates the transportation of oxygen in red blood cells. Almost all vertebrates contain hemoglobin, with the sole exception of the fish family Channichthyidae. Hemoglobi ...

lasts for the entire life-time of an erythrocyte.

The N-end rule The ''N''-end rule is a rule that governs the rate of proteolysis, protein degradation through recognition of the N-terminal residue of proteins. The rule states that the N-terminus, ''N''-terminal amino acid of a protein determines its half-life (t ...

may partially determine the half-life of a protein, and proteins with segments rich in proline, glutamic acid

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; known as glutamate in its anionic form) is an α- amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can ...

, serine, and threonine (the so-called PEST proteins) have short half-life. Other factors suspected to affect degradation rate include the rate deamination of glutamine and asparagine and oxidation of cystein, histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an Amine, α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under Physiological condition, biological conditions), a carboxylic ...

, and methionine, the absence of stabilizing ligands, the presence of attached carbohydrate or phosphate groups, the presence of free α-amino group, the negative charge of protein, and the flexibility and stability of the protein. Proteins with larger degrees of intrinsic disorder also tend to have short cellular half-life, with disordered segments having been proposed to facilitate efficient initiation of degradation by the proteasome.

The rate of proteolysis may also depend on the physiological state of the organism, such as its hormonal state as well as nutritional status. In time of starvation, the rate of protein degradation increases.

Digestion

In humandigestion

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

, proteins in food are broken down into smaller peptide chains by digestive enzymes such as pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. It is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, where it helps digest the proteins in food. Pe ...

, trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

, chymotrypsin, and elastase, and into amino acids by various enzymes such as carboxypeptidase

A carboxypeptidase ( EC number 3.4.16 - 3.4.18) is a protease enzyme that hydrolyzes (cleaves) a peptide bond at the carboxy-terminal (C-terminal) end of a protein or peptide. This is in contrast to an aminopeptidases, which cleave peptide b ...

, aminopeptidase

Aminopeptidases are enzymes that catalyze the cleavage of amino acids from the N-terminus (beginning), of proteins or peptides. They are found in many organisms; in the cell, they are found in many organelles, in the cytosol (internal cellular f ...

, and dipeptidase. It is necessary to break down proteins into small peptides (tripeptides and dipeptides) and amino acids so they can be absorbed by the intestines, and the absorbed tripeptides and dipeptides are also further broken into amino acids intracellularly before they enter the bloodstream. Different enzymes have different specificity for their substrate; trypsin, for example, cleaves the peptide bond after a positively charged residue (arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidinium, guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) a ...

and lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. Lysine contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form when the lysine is dissolved in water at physiological pH), an α-carboxylic acid group ( ...

); chymotrypsin cleaves the bond after an aromatic residue (phenylalanine

Phenylalanine (symbol Phe or F) is an essential α-amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . It can be viewed as a benzyl group substituent, substituted for the methyl group of alanine, or a phenyl group in place of a terminal hydrogen of ...

, tyrosine, and tryptophan); elastase cleaves the bond after a small non-polar residue such as alanine or glycine.

In order to prevent inappropriate or premature activation of the digestive enzymes (they may, for example, trigger pancreatic self-digestion causing pancreatitis

Pancreatitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas is a large organ behind the stomach that produces digestive enzymes and a number of hormone

A hormone (from the Ancient Greek, Greek participle , "se ...

), these enzymes are secreted as inactive zymogen. The precursor of pepsin

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. It is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, where it helps digest the proteins in food. Pe ...

, pepsinogen

Pepsin is an endopeptidase that breaks down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids. It is one of the main digestive enzymes in the digestive systems of humans and many other animals, where it helps digest the proteins in food. Pe ...

, is secreted by the stomach, and is activated only in the acidic environment found in stomach. The pancreas

The pancreas (plural pancreases, or pancreata) is an Organ (anatomy), organ of the Digestion, digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity, abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a ...

secretes the precursors of a number of proteases such as trypsin

Trypsin is an enzyme in the first section of the small intestine that starts the digestion of protein molecules by cutting long chains of amino acids into smaller pieces. It is a serine protease from the PA clan superfamily, found in the dig ...

and chymotrypsin. The zymogen of trypsin is trypsinogen, which is activated by a very specific protease, enterokinase, secreted by the mucosa of the duodenum

The duodenum is the first section of the small intestine in most vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In mammals, it may be the principal site for iron absorption.

The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest p ...

. The trypsin, once activated, can also cleave other trypsinogens as well as the precursors of other proteases such as chymotrypsin and carboxypeptidase to activate them.

In bacteria, a similar strategy of employing an inactive zymogen or prezymogen is used. Subtilisin, which is produced by ''Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'' (), known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacill ...

'', is produced as preprosubtilisin, and is released only if the signal peptide is cleaved and autocatalytic proteolytic activation has occurred.

Cellular regulation

Proteolysis is also involved in the regulation of many cellular processes by activating or deactivating enzymes, transcription factors, and receptors, for example in the biosynthesis of cholesterol, or the mediation of thrombin signalling through protease-activated receptors. Some enzymes at important metabolic control points such as ornithine decarboxylase is regulated entirely by its rate of synthesis and its rate of degradation. Other rapidly degraded proteins include the protein products of proto-oncogenes, which play central roles in the regulation of cell growth.Cell cycle regulation

Cyclins

Cyclins are proteins that control the progression of a cell through the cell cycle by activating cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK).

Etymology

Cyclins were originally discovered by R. Timothy Hunt in 1982 while studying the cell cycle of sea urch ...

are a group of proteins that activate kinases involved in cell division. The degradation of cyclins is the key step that governs the exit from mitosis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new Cell nucleus, nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identic ...

and progress into the next cell cycle

The cell cycle, or cell-division cycle, is the sequential series of events that take place in a cell (biology), cell that causes it to divide into two daughter cells. These events include the growth of the cell, duplication of its DNA (DNA re ...

. Cyclins accumulate in the course the cell cycle, then abruptly disappear just before the anaphase of mitosis. The cyclins are removed via a ubiquitin-mediated proteolytic pathway.

Apoptosis

Caspases are an important group of proteases involved inapoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

or programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD) sometimes referred to as cell, or cellular suicide is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usual ...

. The precursors of caspase, procaspase, may be activated by proteolysis through its association with a protein complex that forms apoptosome, or by granzyme B, or via the death receptor pathways.

Autoproteolysis

Autoproteolysis takes place in some proteins, whereby the peptide bond is cleaved in a self-catalyzedintramolecular reaction

In chemistry, intramolecular describes a Chemical process, process or characteristic limited within the Chemical structure, structure of a single molecule, a property or phenomenon limited to the extent of a single molecule.

Relative rates

In i ...

. Unlike zymogens, these autoproteolytic proteins participate in a "single turnover" reaction and do not catalyze further reactions post-cleavage. Examples include cleavage of the Asp-Pro bond in a subset of von Willebrand factor type D (VWD) domains and '' Neisseria meningitidis'' FrpC self-processing domain, cleavage of the Asn-Pro bond in ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

'' FlhB protein, '' Yersinia'' YscU protein, as well as cleavage of the Gly-Ser bond in a subset of sea urchin sperm protein, enterokinase, and agrin (SEA) domains. In some cases, the autoproteolytic cleavage is promoted by conformational strain of the peptide bond.

Proteolysis and diseases

Abnormal proteolytic activity is associated with many diseases. Inpancreatitis

Pancreatitis is a condition characterized by inflammation of the pancreas. The pancreas is a large organ behind the stomach that produces digestive enzymes and a number of hormone

A hormone (from the Ancient Greek, Greek participle , "se ...

, leakage of proteases and their premature activation in the pancreas results in the self-digestion of the pancreas

The pancreas (plural pancreases, or pancreata) is an Organ (anatomy), organ of the Digestion, digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity, abdomen behind the stomach and functions as a ...

. People with diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained hyperglycemia, high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or th ...

may have increased lysosomal activity and the degradation of some proteins can increase significantly. Chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term autoimmune disorder that primarily affects synovial joint, joints. It typically results in warm, swollen, and painful joints. Pain and stiffness often worsen following rest. Most commonly, the wrist and h ...

may involve the release of lysosomal enzymes into extracellular space that break down surrounding tissues. Abnormal proteolysis may result in age-related neurological diseases such as Alzheimer

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

's due to the generation and ineffective removal of peptides that aggregate in cells.

Proteases may be regulated by antiproteases or protease inhibitors, and imbalance between proteases and antiproteases can result in diseases, for example, in the destruction of lung tissues in emphysema

Emphysema is any air-filled enlargement in the body's tissues. Most commonly emphysema refers to the permanent enlargement of air spaces (alveoli) in the lungs, and is also known as pulmonary emphysema.

Emphysema is a lower respiratory tract di ...

brought on by smoking

Smoking is a practice in which a substance is combusted, and the resulting smoke is typically inhaled to be tasted and absorbed into the bloodstream of a person. Most commonly, the substance used is the dried leaves of the tobacco plant, whi ...

tobacco. Smoking is thought to increase the neutrophils and macrophages

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

in the lung which release excessive amount of proteolytic enzymes such as elastase, such that they can no longer be inhibited by serpins such as α1-antitrypsin, thereby resulting in the breaking down of connective tissues in the lung. Other proteases and their inhibitors may also be involved in this disease, for example matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).

Other diseases linked to aberrant proteolysis include muscular dystrophy

Muscular dystrophies (MD) are a genetically and clinically heterogeneous group of rare neuromuscular diseases that cause progressive weakness and breakdown of skeletal muscles over time. The disorders differ as to which muscles are primarily affe ...

, degenerative skin disorders, respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases, and malignancy.

Non-enzymatic processes

Protein backbones are very stable in water at neutral pH and room temperature, although the rate of hydrolysis of different peptide bonds can vary. The half life of a peptide bond under normal conditions can range from 7 years to 350 years, even higher for peptides protected by modified terminus or within the protein interior. The rate of hydrolysis however can be significantly increased by extremes of pH and heat. Spontaneous cleavage of proteins may also involve catalysis by zinc on serine and threonine. Strong mineral acids can readily hydrolyse the peptide bonds in a protein ( acid hydrolysis). The standard way to hydrolyze a protein or peptide into its constituent amino acids for analysis is to heat it to 105 °C for around 24 hours in 6Mhydrochloric acid

Hydrochloric acid, also known as muriatic acid or spirits of salt, is an aqueous solution of hydrogen chloride (HCl). It is a colorless solution with a distinctive pungency, pungent smell. It is classified as a acid strength, strong acid. It is ...

. However, some proteins are resistant to acid hydrolysis. One well-known example is ribonuclease A, which can be purified by treating crude extracts with hot sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid (American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen, ...

so that other proteins become degraded while ribonuclease A is left intact.

Certain chemicals cause proteolysis only after specific residues, and these can be used to selectively break down a protein into smaller polypeptides for laboratory analysis. For example, cyanogen bromide cleaves the peptide bond after a methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans.

As the precursor of other non-essential amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine play ...

. Similar methods may be used to specifically cleave tryptophanyl, aspartyl, cysteinyl, and asparaginyl peptide bonds. Acids such as trifluoroacetic acid

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) is a synthetic organofluorine compound with the chemical formula CF3CO2H. It belongs to the subclass of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) known as ultrashort-chain perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs). TFA is not ...

and formic acid

Formic acid (), systematically named methanoic acid, is the simplest carboxylic acid. It has the chemical formula HCOOH and structure . This acid is an important intermediate in chemical synthesis and occurs naturally, most notably in some an ...

may be used for cleavage.

Like other biomolecules, proteins can also be broken down by high heat alone. At 250 °C, the peptide bond may be easily hydrolyzed, with its half-life dropping to about a minute. Protein may also be broken down without hydrolysis through pyrolysis

Pyrolysis is a process involving the Bond cleavage, separation of covalent bonds in organic matter by thermal decomposition within an Chemically inert, inert environment without oxygen. Etymology

The word ''pyrolysis'' is coined from the Gree ...

; small heterocyclic compounds may start to form upon degradation. Above 500 °C, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons may also form, which is of interest in the study of generation of carcinogen

A carcinogen () is any agent that promotes the development of cancer. Carcinogens can include synthetic chemicals, naturally occurring substances, physical agents such as ionizing and non-ionizing radiation, and biologic agents such as viruse ...

s in tobacco smoke and cooking at high heat.

Laboratory applications

Proteolysis is also used in research and diagnostic applications: * Cleavage of fusion protein so that the fusion partner and protein tag used in protein expression and purification may be removed. The proteases used have high degree of specificity, such as thrombin, enterokinase, and TEV protease, so that only the targeted sequence may be cleaved. * Complete inactivation of undesirable enzymatic activity or removal of unwanted proteins. For example, proteinase K, a broad-spectrum proteinase stable inurea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest am ...

and SDS, is often used in the preparation of nucleic acids

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nucleic a ...

to remove unwanted nuclease contaminants that may otherwise degrade the DNA or RNA.

* Partial inactivation, or changing the functionality, of specific protein. For example, treatment of DNA polymerase I with subtilisin yields the Klenow fragment, which retains its polymerase function but lacks 5'-exonuclease activity.

* Digestion of proteins in solution for proteome analysis by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). This may also be done by in-gel digestion of proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, re ...

after separation by gel electrophoresis for the identification by mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

.

* Analysis of the stability of folded domain under a wide range of conditions.

* Increasing success rate of crystallisation projects

* Production of digested protein used in growth media to culture bacteria and other organisms, e.g. tryptone

Tryptone is the assortment of peptides formed by the digestion of casein by the protease trypsin.

Tryptone is commonly used in microbiology to produce lysogeny broth, lysogeny broth (LB) for the growth of ''Escherichia coli, E. coli'' and other m ...

in Lysogeny Broth

Lysogeny broth (LB) is a Nutrient, nutritionally rich Growth medium, medium primarily used for the Bacterial growth, growth of bacteria. Its creator, Giuseppe Bertani, intended LB to stand for lysogeny broth, but LB has also come to colloquially ...

.

Protease enzymes

Proteases may be classified according to the catalytic group involved in its active site. * Cysteine protease * Serine protease * Threonine protease * Aspartic protease * Glutamic protease * Metalloprotease * Asparagine peptide lyaseVenoms

Certain types of venom, such as those produced by venomoussnake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s, can also cause proteolysis. These venoms are, in fact, complex digestive fluids that begin their work outside of the body. Proteolytic venoms cause a wide range of toxic effects,Hayes WK. 2005Research on Biological Roles and Variation of Snake Venoms.

Loma Linda University. including effects that are: * cytotoxic (cell-destroying) * hemotoxic (blood-destroying) * myotoxic (muscle-destroying) * hemorrhagic (bleeding)

See also

* The Proteolysis Map * PROTOMAP a proteomic technology for identifying proteolytic substrates * Proteasome * In-gel digestion * UbiquitinReferences

Further reading

*External links

The Journal of Proteolysis

is an open access journal that provides an international forum for the electronic publication of the whole spectrum of high-quality articles and reviews in all areas of proteolysis and proteolytic pathways.

Proteolysis MAP from Center on Proteolytic Pathways

{{Authority control Post-translational modification Metabolism EC 3.4