DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

within each of the 23 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

. A small DNA molecule is found within individual mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

. These are usually treated separately as the nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Human genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

s include both protein-coding DNA sequences and various types of DNA that does not encode proteins. The latter is a diverse category that includes DNA coding for non-translated RNA, such as that for ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

, transfer RNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

, ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to Catalysis, catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozy ...

s, small nuclear RNA

Small nuclear RNA (snRNA) is a class of small RNA molecules that are found within the Cell nucleus#Splicing speckles, splicing speckles and Cajal body, Cajal bodies of the cell nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The length of an average snRNA is approxi ...

s, and several types of regulatory RNAs. It also includes promoters and their associated gene-regulatory elements, DNA playing structural and replicatory roles, such as scaffolding regions, telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

s, centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fiber ...

s, and origins of replication, plus large numbers of transposable elements, inserted viral DNA, non-functional pseudogene

Pseudogenes are nonfunctional segments of DNA that resemble functional genes. Pseudogenes can be formed from both protein-coding genes and non-coding genes. In the case of protein-coding genes, most pseudogenes arise as superfluous copies of fun ...

s and simple, highly repetitive sequences. Intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e., a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gen ...

s make up a large percentage of non-coding DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, microRNA, piRNA, ribosomal RNA, and reg ...

. Some of this non-coding DNA is non-functional junk DNA

Junk DNA (non-functional DNA) is a DNA sequence that has no known biological function. Most organisms have some junk DNA in their genomes—mostly pseudogenes and fragments of transposons and viruses—but it is possible that some organ ...

, such as pseudogenes, but there is no firm consensus on the total amount of junk DNA.

Although the sequence of the human genome has been completely determined by DNA sequencing in 2022 (including methylome), it is not yet fully understood. Most, but not all, gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s have been identified by a combination of high throughput experimental and bioinformatics

Bioinformatics () is an interdisciplinary field of science that develops methods and Bioinformatics software, software tools for understanding biological data, especially when the data sets are large and complex. Bioinformatics uses biology, ...

approaches, yet much work still needs to be done to further elucidate the biological functions of their protein and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

products.

Size of the human genome

In 2000, scientists reported the sequencing of 88% of human genome, but as of 2020, at least 8% was still missing. In 2021, scientists reported sequencing a complete, female genome (i.e., without the Y chromosome). The human Y chromosome, consisting of 62,460,029 base pairs from a different cell line and found in all males, was sequenced completely in January 2022. The current version of the standard reference genome is called GRCh38.p14 (July 2023). It consists of 22 autosomes plus one copy of the X chromosome and one copy of the Y chromosome. It contains approximately 3.1 billion base pairs. This represents the size of a composite genome based on data from multiple individuals but it is a good indication of the typical amount of DNA in a haploid set of chromosomes because the Y chromosome is quite small. Most human cells are diploid so they contain twice as much DNA (~6.2 billion base pairs). In 2023, a draft human pangenome reference was published. It is based on 47 genomes from persons of varied ethnicity. Plans are underway for an improved reference capturing still more biodiversity from a still wider sample. While there are significant differences among the genomes of human individuals (on the order of 0.1% due tosingle-nucleotide variant

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP ; plural SNPs ) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in ...

s and 0.6% when considering indel

Indel (insertion-deletion) is a molecular biology term for an insertion or deletion of bases in the genome of an organism. Indels ≥ 50 bases in length are classified as structural variants.

In coding regions of the genome, unless the lengt ...

s), these are considerably smaller than the differences between humans and their closest living relatives, the bonobo

The bonobo (; ''Pan paniscus''), also historically called the pygmy chimpanzee (less often the dwarf chimpanzee or gracile chimpanzee), is an endangered great ape and one of the two species making up the genus ''Pan (genus), Pan'' (the other bei ...

s and chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of Hominidae, great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close rel ...

s (~1.1% fixed

Fixed may refer to:

* ''Fixed'' (EP), EP by Nine Inch Nails

* ''Fixed'' (film), an upcoming animated film directed by Genndy Tartakovsky

* Fixed (typeface), a collection of monospace bitmap fonts that is distributed with the X Window System

* Fi ...

single-nucleotide variants and 4% when including indels).

Molecular organization and gene content

The total length of the humanreference genome

A reference genome (also known as a reference assembly) is a digital nucleic acid sequence database, assembled by scientists as a representative example of the genome, set of genes in one idealized individual organism of a species. As they are a ...

does not represent the sequence of any specific individual, nor does it represent the sequence of all of the DNA found within a cell. The human reference genome only includes one copy of each of the paired, homologous autosomes plus one copy of each of the two sex chromosomes (X and Y). The total amount of DNA in this reference genome is 3.1 billion base pairs.

Protein-coding genes

Protein-coding sequences represent the most widely studied and best understood component of the human genome. These sequences ultimately lead to the production of all humanprotein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, although several biological processes (e.g. DNA rearrangements and alternative pre-mRNA splicing) can lead to the production of many more unique proteins than the number of protein-coding genes.

The human reference genome contains somewhere between 19,000 and 20,000 protein-coding genes. These genes contain an average of 10 introns and the average size of an intron is about 6 kb (6,000 bp). This means that the average size of a protein-coding gene is about 62 kb and these genes take up about 40% of the genome.

Exon sequences consist of coding DNA and untranslated regions (UTRs) at either end of the mature mRNA. The total amount of coding DNA is about 1-2% of the genome.

Many people divide the genome into coding and non-coding DNA based on the idea that coding DNA is the most important functional component of the genome. About 98-99% of the human genome is non-coding DNA.

Non-coding genes

Noncoding RNA molecules play many essential roles in cells, especially in the many reactions ofprotein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis, or protein synthesis, is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via degradation or export) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critica ...

and RNA processing. Noncoding genes include those for tRNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

s, ribosomal

Ribosomes () are macromolecular machines, found within all cells, that perform biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA molecules to fo ...

RNAs, microRNA

Micro ribonucleic acid (microRNA, miRNA, μRNA) are small, single-stranded, non-coding RNA molecules containing 21–23 nucleotides. Found in plants, animals, and even some viruses, miRNAs are involved in RNA silencing and post-transcr ...

s, snRNAs and long non-coding RNA

Long non-coding RNAs (long ncRNAs, lncRNA) are a type of RNA, generally defined as transcripts more than 200 nucleotides that are not translated into protein. This arbitrary limit distinguishes long ncRNAs from small non-coding RNAs, such as mic ...

s (lncRNAs). The number of reported non-coding genes continues to rise slowly but the exact number in the human genome is yet to be determined. Many RNAs are thought to be non-functional.

Many ncRNAs are critical elements in gene regulation and expression. Noncoding RNA also contributes to epigenetics, transcription, RNA splicing, and the translational machinery. The role of RNA in genetic regulation and disease offers a new potential level of unexplored genomic complexity.

Pseudogenes

Pseudogenes are inactive copies of protein-coding genes, often generated bygene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

, that have become nonfunctional through the accumulation of inactivating mutations. The number of pseudogenes in the human genome is on the order of 13,000, and in some chromosomes is nearly the same as the number of functional protein-coding genes. Gene duplication is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution

Molecular evolution describes how Heredity, inherited DNA and/or RNA change over evolutionary time, and the consequences of this for proteins and other components of Cell (biology), cells and organisms. Molecular evolution is the basis of phylogen ...

.

For example, the olfactory receptor

Olfactory receptors (ORs), also known as odorant receptors, are chemoreceptors expressed in the cell membranes of olfactory receptor neurons and are responsible for the detection of odorants (for example, compounds that have an odor) which give ...

gene family is one of the best-documented examples of pseudogenes in the human genome. More than 60 percent of the genes in this family are non-functional pseudogenes in humans. By comparison, only 20 percent of genes in the mouse olfactory receptor gene family are pseudogenes. Research suggests that this is a species-specific characteristic, as the most closely related primates all have proportionally fewer pseudogenes. This genetic discovery helps to explain the less acute sense of smell in humans relative to other mammals.

Regulatory DNA sequences

The human genome has many differentregulatory sequences

Regulation is the management of complex systems according to a set of rules and trends. In systems theory, these types of rules exist in various fields of biology and society, but the term has slightly different meanings according to context. F ...

which are crucial to controlling gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

. Conservative estimates indicate that these sequences make up 8% of the genome, however extrapolations from the ENCODE

The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) is a public research project which aims "to build a comprehensive parts list of functional elements in the human genome."

ENCODE also supports further biomedical research by "generating community resourc ...

project give that 20 or more of the genome is gene regulatory sequence. Some types of non-coding DNA are genetic "switches" that do not encode proteins, but do regulate when and where genes are expressed (called enhancers

In genetics, an enhancer is a short (50–1500 bp) region of DNA that can be bound by proteins ( activators) to increase the likelihood that transcription of a particular gene will occur. These proteins are usually referred to as transcriptio ...

).

Regulatory sequences have been known since the late 1960s. The first identification of regulatory sequences in the human genome relied on recombinant DNA technology. Later with the advent of genomic sequencing, the identification of these sequences could be inferred by evolutionary conservation. The evolutionary branch between the primates

Primates is an order of mammals, which is further divided into the strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and lorisids; and the haplorhines, which include tarsiers and simians ( monkeys and apes). Primates arose 74–63 ...

and mouse

A mouse (: mice) is a small rodent. Characteristically, mice are known to have a pointed snout, small rounded ears, a body-length scaly tail, and a high breeding rate. The best known mouse species is the common house mouse (''Mus musculus'' ...

, for example, occurred 70–90 million years ago. So computer comparisons of gene sequences that identify conserved non-coding sequences will be an indication of their importance in duties such as gene regulation.

Other genomes have been sequenced with the same intention of aiding conservation-guided methods, one example being the pufferfish

Tetraodontidae is a family of marine and freshwater fish in the order Tetraodontiformes. The family includes many familiar species variously called pufferfish, puffers, balloonfish, blowfish, blowers, blowies, bubblefish, globefish, swellfis ...

genome. However, regulatory sequences disappear and re-evolve during evolution at a high rate.

As of 2012, the efforts have shifted toward finding interactions between DNA and regulatory proteins by the technique ChIP-Seq

ChIP-sequencing, also known as ChIP-seq, is a method used to analyze protein interactions with DNA. ChIP-seq combines chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with Massively parallel signature sequencing, massively parallel DNA sequencing to identify t ...

, or gaps where the DNA is not packaged by histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes ...

s ( DNase hypersensitive sites), both of which tell where there are active regulatory sequences in the investigated cell type.

Repetitive DNA sequences

Repetitive DNA sequences comprise approximately 50% of the human genome. About 8% of the human genome consists of tandem DNA arrays or tandem repeats, low complexity repeat sequences that have multiple adjacent copies (e.g. "CAGCAGCAG..."). The tandem sequences may be of variable lengths, from two nucleotides to tens of nucleotides. These sequences are highly variable, even among closely related individuals, and so are used for genealogical DNA testing and forensic DNA analysis. Repeated sequences of fewer than ten nucleotides (e.g. the dinucleotide repeat (AC)n) are termed microsatellite sequences. Among the microsatellite sequences, trinucleotide repeats are of particular importance, as sometimes occur withincoding region

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding DNA sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for a protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared ...

s of genes for proteins and may lead to genetic disorders. For example, Huntington's disease results from an expansion of the trinucleotide repeat (CAG)n within the ''Huntingtin

Huntingtin (Htt) is the protein coded for in humans by the ''HTT'' gene, also known as the ''IT15'' ("interesting transcript 15") gene. Mutation, Mutated ''HTT'' is the cause of Huntington's disease (HD), and has been investigated for this role an ...

'' gene on human chromosome 4. Telomeres (the ends of linear chromosomes) end with a microsatellite hexanucleotide repeat of the sequence (TTAGGG)n.

Tandem repeats of longer sequences (arrays of repeated sequences 10–60 nucleotides long) are termed minisatellite

In genetics, a minisatellite is a tract of repetitive DNA in which certain DNA motifs (ranging in length from 10–60 base pairs) are typically repeated two to several hundred times. Minisatellites occur at more than 1,000 locations in the huma ...

s.

Transposable genetic elements, DNA sequences that can replicate and insert copies of themselves at other locations within a host genome, are an abundant component in the human genome. The most abundant transposon lineage, ''Alu'', has about 50,000 active copies, and can be inserted into intragenic and intergenic regions. One other lineage, LINE-1, has about 100 active copies per genome (the number varies between people). Together with non-functional relics of old transposons, they account for over half of total human DNA. Sometimes called "jumping genes", transposons have played a major role in sculpting the human genome. Some of these sequences represent endogenous retroviruses, DNA copies of viral sequences that have become permanently integrated into the genome and are now passed on to succeeding generations. There are also a significant number of retroviruses in human DNA, at least 3 of which have been proven to possess an important function (i.e., HIV-like functional HERV-K; envelope genes of non-functional viruses HERV-W and HERV-FRD play a role in placenta formation by inducing cell-cell fusion).

Mobile elements within the human genome can be classified into LTR retrotransposons (8.3% of total genome), SINEs (13.1% of total genome) including Alu elements

An Alu element is a short stretch of DNA originally characterized by the action of the ''Arthrobacter luteus (Alu)'' restriction endonuclease. ''Alu'' elements are the most abundant transposable elements in the human genome, present in excess of ...

, LINEs (20.4% of total genome), SVAs (SINE- VNTR-Alu) and Class II DNA transposons (2.9% of total genome).

Junk DNA

There is no consensus on what constitutes a "functional" element in the genome since geneticists, evolutionary biologists, and molecular biologists employ different definitions and methods. Due to the ambiguity in the terminology, different schools of thought have emerged. In evolutionary definitions, "functional" DNA, whether it is coding or non-coding, contributes to the fitness of the organism, and therefore is maintained by negativeevolutionary pressure

Evolutionary pressure, selective pressure or selection pressure is exerted by factors that reduce or increase reproductive success in a portion of a population, driving natural selection. It is a quantitative description of the amount of change o ...

whereas "non-functional" DNA has no benefit to the organism and therefore is under neutral selective pressure. This type of DNA has been described as junk DNA

Junk DNA (non-functional DNA) is a DNA sequence that has no known biological function. Most organisms have some junk DNA in their genomes—mostly pseudogenes and fragments of transposons and viruses—but it is possible that some organ ...

. In genetic definitions, "functional" DNA is related to how DNA segments manifest by phenotype and "nonfunctional" is related to loss-of-function effects on the organism. In biochemical definitions, "functional" DNA relates to DNA sequences that specify molecular products (e.g. noncoding RNAs) and biochemical activities with mechanistic roles in gene or genome regulation (i.e. DNA sequences that impact cellular level activity such as cell type, condition, and molecular processes). There is no consensus in the literature on the amount of functional DNA since, depending on how "function" is understood, ranges have been estimated from up to 90% of the human genome is likely nonfunctional DNA (junk DNA) to up to 80% of the genome is likely functional.. It is also possible that junk DNA may acquire a function in the future and therefore may play a role in evolution, but this is likely to occur only very rarely. Finally DNA that is deliterious to the organism and is under negative selective pressure is called garbage DNA.

Sequencing

The first human genome sequences were published in nearly complete draft form in February 2001 by theHuman Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

and Celera Corporation. Completion of the Human Genome Project's sequencing effort was announced in 2004 with the publication of a draft genome sequence, leaving just 341 gaps in the sequence, representing highly repetitive and other DNA that could not be sequenced with the technology available at the time. The human genome was the first of all vertebrates to be sequenced to such near-completion, and as of 2018, the diploid genomes of over a million individual humans had been determined using next-generation sequencing

Massive parallel sequencing or massively parallel sequencing is any of several high-throughput approaches to DNA sequencing using the concept of massively parallel processing; it is also called next-generation sequencing (NGS) or second-generation ...

.

These data are used worldwide in biomedical science, anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

, forensics

Forensic science combines principles of law and science to investigate criminal activity. Through crime scene investigations and laboratory analysis, forensic scientists are able to link suspects to evidence. An example is determining the time and ...

and other branches of science. Such genomic studies have led to advances in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, and to new insights in many fields of biology, including human evolution

''Homo sapiens'' is a distinct species of the hominid family of primates, which also includes all the great apes. Over their evolutionary history, humans gradually developed traits such as Human skeletal changes due to bipedalism, bipedalism, de ...

.

By 2018, the total number of genes had been raised to at least 46,831, plus another 2300 micro-RNA genes. A 2018 population survey found another 300 million bases of human genome that was not in the reference sequence. Prior to the acquisition of the full genome sequence, estimates of the number of human genes ranged from 50,000 to 140,000 (with occasional vagueness about whether these estimates included non-protein coding genes). As genome sequence quality and the methods for identifying protein-coding genes improved, the count of recognized protein-coding genes dropped to 19,000–20,000.

In 2022, the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) consortium reported the complete sequence of a human female genome, filling all the gaps in the X chromosome

The X chromosome is one of the two sex chromosomes in many organisms, including mammals, and is found in both males and females. It is a part of the XY sex-determination system and XO sex-determination system. The X chromosome was named for its u ...

(2020) and the 22 autosomes (May 2021). The previously unsequenced parts contain immune response

An immune response is a physiological reaction which occurs within an organism in the context of inflammation for the purpose of defending against exogenous factors. These include a wide variety of different toxins, viruses, intra- and extracellula ...

genes that help to adapt to and survive infections, as well as genes that are important for predicting drug response. The completed human genome sequence will also provide better understanding of human formation as an individual organism and how humans vary both between each other and other species.

Although the 'completion' of the human genome project was announced in 2001, there remained hundreds of gaps, with about 5–10% of the total sequence remaining undetermined. The missing genetic information was mostly in repetitive heterochromatic regions and near the centromere

The centromere links a pair of sister chromatids together during cell division. This constricted region of chromosome connects the sister chromatids, creating a short arm (p) and a long arm (q) on the chromatids. During mitosis, spindle fiber ...

s and telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

s, but also some gene-encoding euchromatic regions. There remained 160 euchromatic gaps in 2015 when the sequences spanning another 50 formerly unsequenced regions were determined. Only in 2020 was the first truly complete telomere-to-telomere sequence of a human chromosome determined, namely of the X chromosome

The X chromosome is one of the two sex chromosomes in many organisms, including mammals, and is found in both males and females. It is a part of the XY sex-determination system and XO sex-determination system. The X chromosome was named for its u ...

. The first complete telomere-to-telomere sequence of a human autosomal chromosome, chromosome 8, followed a year later. The complete human genome (without Y chromosome) was published in 2021, while with Y chromosome in January 2022.

In 2023, a draft human pangenome reference was published. It is based on 47 genomes from persons of varied ethnicity. Plans are underway for an improved reference capturing still more biodiversity from a still wider sample.

Genomic variation in humans

Human reference genome

With the exception of identical twins, all humans show significant variation in genomic DNA sequences. The humanreference genome

A reference genome (also known as a reference assembly) is a digital nucleic acid sequence database, assembled by scientists as a representative example of the genome, set of genes in one idealized individual organism of a species. As they are a ...

(HRG) is used as a standard sequence reference.

There are several important points concerning the human reference genome:

* The HRG is a haploid sequence. Each chromosome is represented once.

* The HRG is a composite sequence, and does not correspond to any actual human individual.

* The HRG is periodically updated to correct errors, ambiguities, and unknown "gaps".

* The HRG in no way represents an "ideal" or "perfect" human individual. It is simply a standardized representation or model that is used for comparative purposes.

The Genome Reference Consortium is responsible for updating the HRG. Version 38 was released in December 2013.

Measuring human genetic variation

Most studies of human genetic variation have focused onsingle-nucleotide polymorphism

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP ; plural SNPs ) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in a ...

s (SNPs), which are substitutions in individual bases along a chromosome. Most analyses estimate that SNPs occur 1 in 1000 base pairs, on average, in the euchromatic human genome, although they do not occur at a uniform density. Thus follows the popular statement that "we are all, regardless of race, genetically 99.9% the same", although this would be somewhat qualified by most geneticists. For example, a much larger fraction of the genome is now thought to be involved in copy number variation

Copy number variation (CNV) is a phenomenon in which sections of the genome are repeated and the number of repeats in the genome varies between individuals. Copy number variation is a type of structural variation: specifically, it is a type of ...

. A large-scale collaborative effort to catalog SNP variations in the human genome is being undertaken by the International HapMap Project

The International HapMap Project was an organization that aimed to develop a haplotype map (HapMap) of the human genome, to describe the common patterns of human genetic variation. HapMap is used to find genetic variants affecting health, disease ...

.

The genomic loci and length of certain types of small repetitive sequences are highly variable from person to person, which is the basis of DNA fingerprinting

DNA profiling (also called DNA fingerprinting and genetic fingerprinting) is the process of determining an individual's deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) characteristics. DNA analysis intended to identify a species, rather than an individual, is cal ...

and DNA paternity testing

DNA paternity testing uses DNA profiling, DNA profiles to determine whether an individual is the biology, biological parent of another individual. Paternity testing can be essential when the rights and duties of the father are in issue, and a ch ...

technologies. The heterochromatic portions of the human genome, which total several hundred million base pairs, are also thought to be quite variable within the human population (they are so repetitive and so long that they cannot be accurately sequenced with current technology). These regions contain few genes, and it is unclear whether any significant phenotypic

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

effect results from typical variation in repeats or heterochromatin.

Most gross genomic mutations in gamete

A gamete ( ) is a Ploidy#Haploid and monoploid, haploid cell that fuses with another haploid cell during fertilization in organisms that Sexual reproduction, reproduce sexually. Gametes are an organism's reproductive cells, also referred to as s ...

germ cells probably result in inviable embryos; however, a number of human diseases are related to large-scale genomic abnormalities. Down syndrome, Turner Syndrome

Turner syndrome (TS), commonly known as 45,X, or 45,X0,Also written as 45,XO. is a chromosomal disorder in which cells of females have only one X chromosome instead of two, or are partially missing an X chromosome (sex chromosome monosomy) lea ...

, and a number of other diseases result from nondisjunction

Nondisjunction is the failure of homologous chromosomes or sister chromatids to separate properly during cell division (mitosis/meiosis). There are three forms of nondisjunction: failure of a pair of homologous chromosomes to separate in meiosis I ...

of entire chromosomes. Cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

cells frequently have aneuploidy

Aneuploidy is the presence of an abnormal number of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, for example a human somatic (biology), somatic cell having 45 or 47 chromosomes instead of the usual 46. It does not include a difference of one or more plo ...

of chromosomes and chromosome arms, although a cause and effect relationship between aneuploidy and cancer has not been established.

Mapping human genomic variation

Whereas a genome sequence lists the order of every DNA base in a genome, a genome map identifies the landmarks. A genome map is less detailed than a genome sequence and aids in navigating around the genome. An example of a variation map is the HapMap being developed by theInternational HapMap Project

The International HapMap Project was an organization that aimed to develop a haplotype map (HapMap) of the human genome, to describe the common patterns of human genetic variation. HapMap is used to find genetic variants affecting health, disease ...

. The HapMap is a haplotype

A haplotype (haploid genotype) is a group of alleles in an organism that are inherited together from a single parent.

Many organisms contain genetic material (DNA) which is inherited from two parents. Normally these organisms have their DNA orga ...

map of the human genome, "which will describe the common patterns of human DNA sequence variation." It catalogs the patterns of small-scale variations in the genome that involve single DNA letters, or bases.

Researchers published the first sequence-based map of large-scale structural variation across the human genome in the journal ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' in May 2008. Large-scale structural variations are differences in the genome among people that range from a few thousand to a few million DNA bases; some are gains or losses of stretches of genome sequence and others appear as re-arrangements of stretches of sequence. These variations include differences in the number of copies individuals have of a particular gene, deletions, translocations and inversions.

Structural variation

Structural variation refers to genetic variants that affect larger segments of the human genome, as opposed to pointmutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s. Often, structural variants (SVs) are defined as variants of 50 base pairs (bp) or greater, such as deletions, duplications, insertions, inversions and other rearrangements. About 90% of structural variants are noncoding deletions but most individuals have more than a thousand such deletions; the size of deletions ranges from dozens of base pairs to tens of thousands of bp. On average, individuals carry ~3 rare structural variants that alter coding regions, e.g. delete exon

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequence ...

s. About 2% of individuals carry ultra-rare megabase-scale structural variants, especially rearrangements. That is, millions of base pairs may be inverted within a chromosome; ultra-rare means that they are only found in individuals or their family members and thus have arisen very recently.

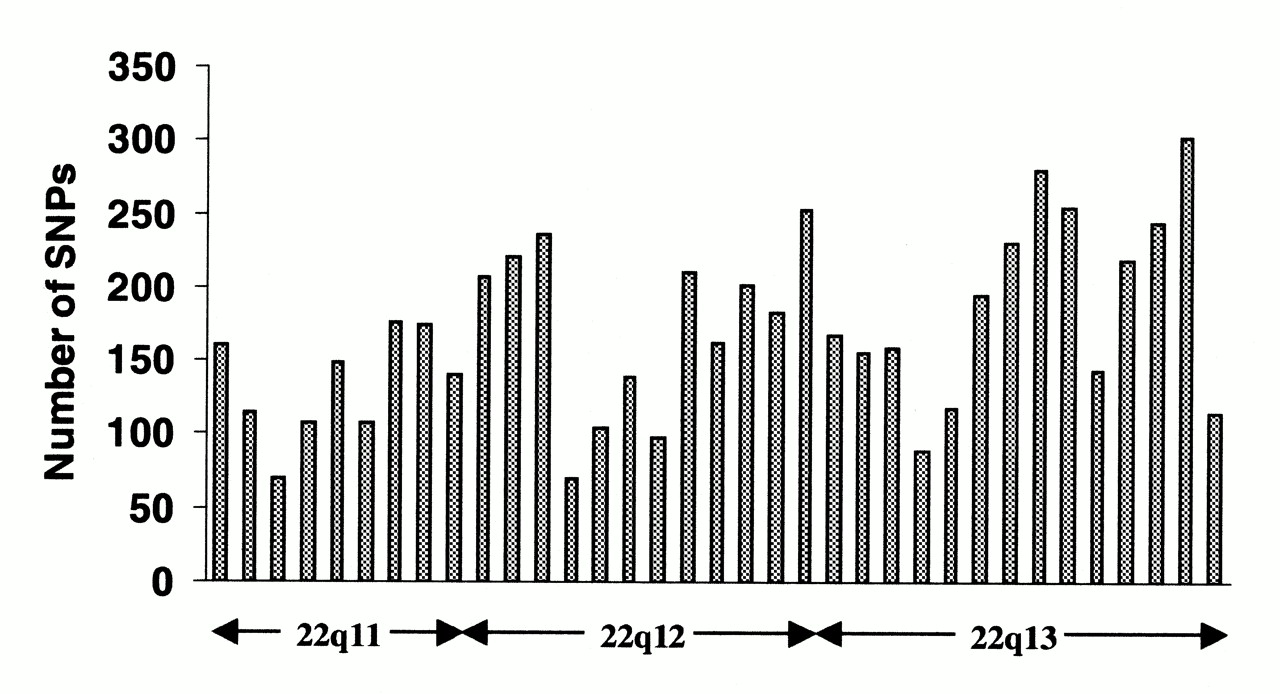

SNP frequency across the human genome

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) do not occur homogeneously across the human genome. In fact, there is enormous diversity in SNP frequency between genes, reflecting different selective pressures on each gene as well as different mutation and recombination rates across the genome. However, studies on SNPs are biased towards coding regions, the data generated from them are unlikely to reflect the overall distribution of SNPs throughout the genome. Therefore, the SNP Consortium protocol was designed to identify SNPs with no bias towards coding regions and the Consortium's 100,000 SNPs generally reflect sequence diversity across the human chromosomes. The SNP Consortium aims to expand the number of SNPs identified across the genome to 300 000 by the end of the first quarter of 2001. Changes in non-coding sequence and synonymous changes in coding sequence are generally more common than non-synonymous changes, reflecting greater selective pressure reducing diversity at positions dictating amino acid identity. Transitional changes are more common than transversions, with CpG dinucleotides showing the highest mutation rate, presumably due to deamination.

Changes in non-coding sequence and synonymous changes in coding sequence are generally more common than non-synonymous changes, reflecting greater selective pressure reducing diversity at positions dictating amino acid identity. Transitional changes are more common than transversions, with CpG dinucleotides showing the highest mutation rate, presumably due to deamination.

Personal genomes

A personal genome sequence is a (nearly) completesequence

In mathematics, a sequence is an enumerated collection of objects in which repetitions are allowed and order matters. Like a set, it contains members (also called ''elements'', or ''terms''). The number of elements (possibly infinite) is cal ...

of the chemical base pairs that make up the DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

of a single person. Because medical treatments have different effects on different people due to genetic variations such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP ; plural SNPs ) is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in ...

(SNPs), the analysis of personal genomes may lead to personalized medical treatment based on individual genotypes.

The first personal genome sequence to be determined was that of Craig Venter

John Craig Venter (born October 14, 1946) is an American scientist. He is known for leading one of the first draft sequences of the human genome and led the first team to transfect a cell with a synthetic chromosome. Venter founded Celera Geno ...

in 2007. Personal genomes had not been sequenced in the public Human Genome Project to protect the identity of volunteers who provided DNA samples. That sequence was derived from the DNA of several volunteers from a diverse population. However, early in the Venter-led Celera Genomics genome sequencing effort the decision was made to switch from sequencing a composite sample to using DNA from a single individual, later revealed to have been Venter himself. Thus the Celera human genome sequence released in 2000 was largely that of one man. Subsequent replacement of the early composite-derived data and determination of the diploid sequence, representing both sets of chromosomes

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most importa ...

, rather than a haploid sequence originally reported, allowed the release of the first personal genome. In April 2008, that of James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biology, molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in ''Nature (journal), Nature'' proposing the Nucleic acid ...

was also completed. In 2009, Stephen Quake published his own genome sequence derived from a sequencer of his own design, the Heliscope. A Stanford team led by Euan Ashley published a framework for the medical interpretation of human genomes implemented on Quake's genome and made whole genome-informed medical decisions for the first time. That team further extended the approach to the West family, the first family sequenced as part of Illumina's Personal Genome Sequencing program. Since then hundreds of personal genome sequences have been released, including those of Desmond Tutu

Desmond Mpilo Tutu (7 October 193126 December 2021) was a South African Anglican bishop and theologian, known for his work as an anti-apartheid and human rights activist. He was Bishop of Johannesburg from 1985 to 1986 and then Archbishop ...

, and of a Paleo-Eskimo

The Paleo-Eskimo meaning ''"old Eskimos"'', also known as, pre-Thule people, Thule or pre-Inuit, were the peoples who inhabited the Arctic region from Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Chukotka (e.g., Chertov Ovrag) in present-day Russia across North Am ...

. In 2012, the whole genome sequences of two family trios among 1092 genomes was made public. In November 2013, a Spanish family made four personal exome datasets (about 1% of the genome) publicly available under a Creative Commons public domain license. The Personal Genome Project (started in 2005) is among the few to make both genome sequences and corresponding medical phenotypes publicly available.

The sequencing of individual genomes further unveiled levels of genetic complexity that had not been appreciated before. Personal genomics helped reveal the significant level of diversity in the human genome attributed not only to SNPs but structural variations as well. However, the application of such knowledge to the treatment of disease and in the medical field is only in its very beginnings. Exome sequencing

Exome sequencing, also known as whole exome sequencing (WES), is a genomic technique for sequencing all of the protein-coding regions of genes in a genome (known as the exome). It consists of two steps: the first step is to select only the subs ...

has become increasingly popular as a tool to aid in diagnosis of genetic disease because the exome contributes only 1% of the genomic sequence but accounts for roughly 85% of mutations that contribute significantly to disease.

Human knockouts

In humans, gene knockouts naturally occur asheterozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mos ...

or homozygous

Zygosity (the noun, zygote, is from the Greek "yoked," from "yoke") () is the degree to which both copies of a chromosome or gene have the same genetic sequence. In other words, it is the degree of similarity of the alleles in an organism.

Mos ...

loss-of-function

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, mitosis ...

gene knockouts. These knockouts are often difficult to distinguish, especially within heterogeneous

Homogeneity and heterogeneity are concepts relating to the uniformity of a substance, process or image. A homogeneous feature is uniform in composition or character (i.e., color, shape, size, weight, height, distribution, texture, language, i ...

genetic backgrounds. They are also difficult to find as they occur in low frequencies.

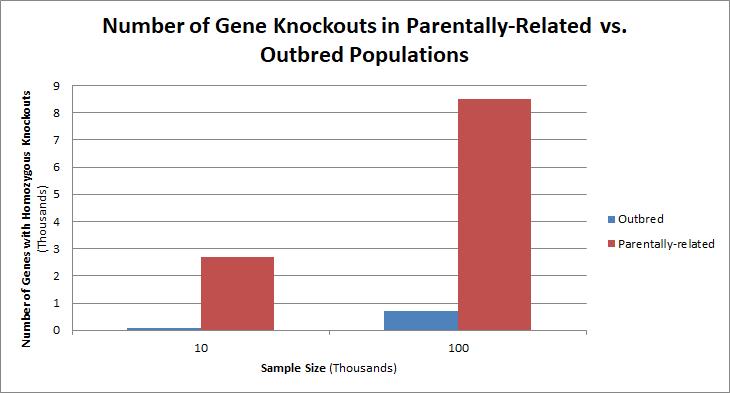

Populations with high rates of

Populations with high rates of consanguinity

Consanguinity (from Latin '':wikt: consanguinitas, consanguinitas'' 'blood relationship') is the characteristic of having a kinship with a relative who is descended from a common ancestor.

Many jurisdictions have laws prohibiting people who are ...

, such as countries with high rates of first-cousin marriages, display the highest frequencies of homozygous gene knockouts. Such populations include Pakistan, Iceland, and Amish populations. These populations with a high level of parental-relatedness have been subjects of human knock out research which has helped to determine the function of specific genes in humans. By distinguishing specific knockouts, researchers are able to use phenotypic analyses of these individuals to help characterize the gene that has been knocked out.

Knockouts in specific genes can cause genetic diseases, potentially have beneficial effects, or even result in no phenotypic effect at all. However, determining a knockout's phenotypic effect and in humans can be challenging. Challenges to characterizing and clinically interpreting knockouts include difficulty calling of DNA variants, determining disruption of protein function (annotation), and considering the amount of influence mosaicism has on the phenotype.

One major study that investigated human knockouts is the Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction study. It was found that individuals possessing a heterozygous loss-of-function gene knockout for the APOC3 gene had lower triglycerides in the blood after consuming a high fat meal as compared to individuals without the mutation. However, individuals possessing homozygous loss-of-function gene knockouts of the APOC3 gene displayed the lowest level of triglycerides in the blood after the fat load test, as they produce no functional APOC3 protein.

Knockouts in specific genes can cause genetic diseases, potentially have beneficial effects, or even result in no phenotypic effect at all. However, determining a knockout's phenotypic effect and in humans can be challenging. Challenges to characterizing and clinically interpreting knockouts include difficulty calling of DNA variants, determining disruption of protein function (annotation), and considering the amount of influence mosaicism has on the phenotype.

One major study that investigated human knockouts is the Pakistan Risk of Myocardial Infarction study. It was found that individuals possessing a heterozygous loss-of-function gene knockout for the APOC3 gene had lower triglycerides in the blood after consuming a high fat meal as compared to individuals without the mutation. However, individuals possessing homozygous loss-of-function gene knockouts of the APOC3 gene displayed the lowest level of triglycerides in the blood after the fat load test, as they produce no functional APOC3 protein.

DNA damage

In each cell of the human body, the human genome experiences, on average, tens of thousands of DNA damages per day. These damages can block genome replication or genome transcription, and if they are not repaired or are repaired incorrectly, they may lead tomutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s, or other genome alterations in the human genome that threaten cell viability.

Human genetic disorders

Most aspects of human biology involve both genetic (inherited) and non-genetic (environmental) factors. Some inherited variation influences aspects of our biology that are not medical in nature (height, eye color, ability to taste or smell certain compounds, etc.). Moreover, some genetic disorders only cause disease in combination with the appropriate environmental factors (such as diet). With these caveats, genetic disorders may be described as clinically defined diseases caused by genomic DNA sequence variation. In the most straightforward cases, the disorder can be associated with variation in a single gene. For example,cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

is caused by mutations in the CFTR gene and is the most common recessive disorder in caucasian populations with over 1,300 different mutations known.

Disease-causing mutations in specific genes are usually severe in terms of gene function and are rare, thus genetic disorders are similarly individually rare. However, since there are many genes that can vary to cause genetic disorders, in aggregate they constitute a significant component of known medical conditions, especially in pediatric medicine. Molecularly characterized genetic disorders are those for which the underlying causal gene has been identified. Currently there are approximately 2,200 such disorders annotated in the OMIM

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) is a continuously updated catalog of human genes and genetic disorders and traits, with a particular focus on the gene-phenotype relationship. , approximately 9,000 of the over 25,000 entries in OMIM ...

database.

Studies of genetic disorders are often performed by means of family-based studies. In some instances, population based approaches are employed, particularly in the case of so-called founder populations such as those in Finland, French-Canada, Utah, Sardinia, etc. Diagnosis and treatment of genetic disorders are usually performed by a geneticist

A geneticist is a biologist or physician who studies genetics, the science of genes, heredity, and variation of organisms. A geneticist can be employed as a scientist or a lecturer. Geneticists may perform general research on genetic process ...

-physician trained in clinical/medical genetics. The results of the Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

are likely to provide increased availability of genetic testing

Genetic testing, also known as DNA testing, is used to identify changes in DNA sequence or chromosome structure. Genetic testing can also include measuring the results of genetic changes, such as RNA analysis as an output of gene expression, or ...

for gene-related disorders, and eventually improved treatment. Parents can be screened for hereditary conditions and counselled on the consequences, the probability of inheritance, and how to avoid or ameliorate it in their offspring.

There are many different kinds of DNA sequence variation, ranging from complete extra or missing chromosomes down to single nucleotide changes. It is generally presumed that much naturally occurring genetic variation in human populations is phenotypically neutral, i.e., has little or no detectable effect on the physiology of the individual (although there may be fractional differences in fitness defined over evolutionary time frames). Genetic disorders can be caused by any or all known types of sequence variation. To molecularly characterize a new genetic disorder, it is necessary to establish a causal link between a particular genomic sequence variant and the clinical disease under investigation. Such studies constitute the realm of human molecular genetics.

With the advent of the Human Genome and International HapMap Project

The International HapMap Project was an organization that aimed to develop a haplotype map (HapMap) of the human genome, to describe the common patterns of human genetic variation. HapMap is used to find genetic variants affecting health, disease ...

, it has become feasible to explore subtle genetic influences on many common disease conditions such as diabetes, asthma, migraine, schizophrenia, etc. Although some causal links have been made between genomic sequence variants in particular genes and some of these diseases, often with much publicity in the general media, these are usually not considered to be genetic disorders ''per se'' as their causes are complex, involving many different genetic and environmental factors. Thus there may be disagreement in particular cases whether a specific medical condition should be termed a genetic disorder.

Additional genetic disorders of mention are Kallman syndrome and Pfeiffer syndrome

Pfeiffer syndrome is a rare genetic disorder, characterized by the premature fusion of certain bones of the human skull, skull (craniosynostosis), which affects the shape of the head and face. The syndrome includes abnormalities of the hands an ...

(gene FGFR1), Fuchs corneal dystrophy (gene TCF4), Hirschsprung's disease (genes RET and FECH), Bardet-Biedl syndrome 1 (genes CCDC28B and BBS1), Bardet-Biedl syndrome 10 (gene BBS10), and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy type 2 (genes D4Z4 and SMCHD1).

Genome sequencing is now able to narrow the genome down to specific locations to more accurately find mutations that will result in a genetic disorder. Copy number variants (CNVs) and single nucleotide variants (SNVs) are also able to be detected at the same time as genome sequencing with newer sequencing procedures available, called Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). This only analyzes a small portion of the genome, around 1–2%. The results of this sequencing can be used for clinical diagnosis of a genetic condition, including Usher syndrome, retinal disease, hearing impairments, diabetes, epilepsy, Leigh disease, hereditary cancers, neuromuscular diseases, primary immunodeficiencies, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), and diseases of the mitochondria. NGS can also be used to identify carriers of diseases before conception. The diseases that can be detected in this sequencing include Tay-Sachs disease, Bloom syndrome, Gaucher disease, Canavan disease, familial dysautonomia, cystic fibrosis, spinal muscular atrophy, and fragile-X syndrome. The Next Genome Sequencing can be narrowed down to specifically look for diseases more prevalent in certain ethnic populations.

Evolution

Comparative genomics

Comparative genomics is a branch of biological research that examines genome sequences across a spectrum of species, spanning from humans and mice to a diverse array of organisms from bacteria to chimpanzees. This large-scale holistic approach c ...

studies of mammalian genomes suggest that approximately 5% of the human genome has been conserved by evolution since the divergence of extant lineages approximately 200 million years ago, containing the vast majority of genes. The published chimpanzee

The chimpanzee (; ''Pan troglodytes''), also simply known as the chimp, is a species of Hominidae, great ape native to the forests and savannahs of tropical Africa. It has four confirmed subspecies and a fifth proposed one. When its close rel ...

genome differs from that of the human genome by 1.23% in direct sequence comparisons. Around 20% of this figure is accounted for by variation within each species, leaving only ~1.06% consistent sequence divergence between humans and chimps at shared genes. This nucleotide by nucleotide difference is dwarfed, however, by the portion of each genome that is not shared, including around 6% of functional genes that are unique to either humans or chimps.

In other words, the considerable observable differences between humans and chimps may be due as much or more to genome level variation in the number, function and expression of genes rather than DNA sequence changes in shared genes. Indeed, even within humans, there has been found to be a previously unappreciated amount of copy number variation (CNV) which can make up as much as 5–15% of the human genome. In other words, between humans, there could be +/- 500,000,000 base pairs of DNA, some being active genes, others inactivated, or active at different levels. The full significance of this finding remains to be seen. On average, a typical human protein-coding gene differs from its chimpanzee ortholog

Sequence homology is the biological homology between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences, defined in terms of shared ancestry in the evolutionary history of life. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of three phenomena: either a speci ...

by only two amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

substitutions; nearly one third of human genes have exactly the same protein translation as their chimpanzee orthologs. A major difference between the two genomes is human chromosome 2

Chromosome 2 is one of the twenty-three pairs of chromosomes in humans. People normally have two copies of this chromosome. Chromosome 2 is the second-largest human chromosome, spanning more than 242 million base pairs and representing almost ei ...

, which is equivalent to a fusion product of chimpanzee chromosomes 12 and 13. (later renamed to chromosomes 2A and 2B, respectively).

Humans have undergone an extraordinary loss of olfactory receptor

Olfactory receptors (ORs), also known as odorant receptors, are chemoreceptors expressed in the cell membranes of olfactory receptor neurons and are responsible for the detection of odorants (for example, compounds that have an odor) which give ...

genes during our recent evolution, which explains our relatively crude sense of smell compared to most other mammals. Evolutionary evidence suggests that the emergence of color vision

Color vision, a feature of visual perception, is an ability to perceive differences between light composed of different frequencies independently of light intensity.

Color perception is a part of the larger visual system and is mediated by a co ...

in humans and several other primate

Primates is an order (biology), order of mammals, which is further divided into the Strepsirrhini, strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and Lorisidae, lorisids; and the Haplorhini, haplorhines, which include Tarsiiformes, tarsiers a ...

species has diminished the need for the sense of smell.

In September 2016, scientists reported that, based on human DNA genetic studies, all non-Africans in the world today can be traced to a single population that exited Africa between 50,000 and 80,000 years ago.

Mitochondrial DNA

The humanmitochondrial DNA

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA and mDNA) is the DNA located in the mitochondrion, mitochondria organelles in a eukaryotic cell that converts chemical energy from food into adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Mitochondrial DNA is a small portion of the D ...

is of tremendous interest to geneticists, since it undoubtedly plays a role in mitochondrial disease. It also sheds light on human evolution; for example, analysis of variation in the human mitochondrial genome has led to the postulation of a recent common ancestor for all humans on the maternal line of descent (see Mitochondrial Eve

In human genetics, the Mitochondrial Eve (more technically known as the Mitochondrial-Most Recent Common Ancestor, shortened to mt-Eve or mt-MRCA) is the matrilineal most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all living humans. In other words, she ...

).

Due to the damage induced by the exposure to Reactive Oxygen Species mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has a more rapid rate of variation than nuclear DNA. This 20-fold higher mutation rate allows mtDNA to be used for more accurate tracing of maternal ancestry. Studies of mtDNA in populations have allowed ancient migration paths to be traced, such as the migration of Native Americans from Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

or Polynesia

Polynesia ( , ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of more than 1,000 islands scattered over the central and southern Pacific Ocean. The indigenous people who inhabit the islands of Polynesia are called Polynesians. They have many things in ...

ns from southeastern Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

. It has also been used to show that there is no trace of Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

DNA in the European gene mixture inherited through purely maternal lineage. Due to the restrictive all or none manner of mtDNA inheritance, this result (no trace of Neanderthal mtDNA) would be likely unless there were a large percentage of Neanderthal ancestry, or there was strong positive selection for that mtDNA. For example, going back 5 generations, only 1 of a person's 32 ancestors contributed to that person's mtDNA, so if one of these 32 was pure Neanderthal an expected ~3% of that person's autosomal DNA would be of Neanderthal origin, yet they would have a ~97% chance of having no trace of Neanderthal mtDNA.

Epigenome

Epigenetics describes a variety of features of the human genome that transcend its primary DNA sequence, such aschromatin

Chromatin is a complex of DNA and protein found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. The primary function is to package long DNA molecules into more compact, denser structures. This prevents the strands from becoming tangled and also plays important r ...

packaging, histone

In biology, histones are highly basic proteins abundant in lysine and arginine residues that are found in eukaryotic cell nuclei and in most Archaeal phyla. They act as spools around which DNA winds to create structural units called nucleosomes ...

modifications and DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a biological process by which methyl groups are added to the DNA molecule. Methylation can change the activity of a DNA segment without changing the sequence. When located in a gene promoter (genetics), promoter, DNA methylati ...

, and which are important in regulating gene expression, genome replication and other cellular processes. Epigenetic markers strengthen and weaken transcription of certain genes but do not affect the actual sequence of DNA nucleotides. DNA methylation is a major form of epigenetic control over gene expression and one of the most highly studied topics in epigenetics. During development, the human DNA methylation profile experiences dramatic changes. In early germ line cells, the genome has very low methylation levels. These low levels generally describe active genes. As development progresses, parental imprinting tags lead to increased methylation activity.

Epigenetic patterns can be identified between tissues within an individual as well as between individuals themselves. Identical genes that have differences only in their epigenetic state are called epialleles. Epialleles can be placed into three categories: those directly determined by an individual's genotype, those influenced by genotype, and those entirely independent of genotype. The epigenome is also influenced significantly by environmental factors. Diet, toxins, and hormones impact the epigenetic state. Studies in dietary manipulation have demonstrated that methyl-deficient diets are associated with hypomethylation of the epigenome. Such studies establish epigenetics as an important interface between the environment and the genome.

See also

*Human Genome Organisation

The Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) is a non-profit organization founded in 1988. HUGO represents an international coordinating scientific body in response to initiatives such as the Human Genome Project. HUGO has four active committees, includi ...

* Genome Reference Consortium

* Human Genome Project

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a ...

* Genetics

Genetics is the study of genes, genetic variation, and heredity in organisms.Hartl D, Jones E (2005) It is an important branch in biology because heredity is vital to organisms' evolution. Gregor Mendel, a Moravian Augustinians, Augustinian ...

* Genomics

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, ...

* Genographic Project

The Genographic Project, launched on 13 April 2005 by the National Geographic Society and IBM, was a Molecular anthropology, genetic anthropological study (sales discontinued on 31 May 2019) that aimed to map historical human migrations patter ...

* Genomic organization

* Karyotype

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by de ...

* Low copy repeats

* Non-coding DNA

Non-coding DNA (ncDNA) sequences are components of an organism's DNA that do not encode protein sequences. Some non-coding DNA is transcribed into functional non-coding RNA molecules (e.g. transfer RNA, microRNA, piRNA, ribosomal RNA, and reg ...

* Whole genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing (WGS), also known as full genome sequencing or just genome sequencing, is the process of determining the entirety of the DNA sequence of an organism's genome at a single time. This entails sequencing all of an organism's ...

* Universal Declaration on the Human Genome and Human Rights

References

External links

Annotated (version 110) genome viewer of T2T-CHM13 v2.0

Complete human genome T2T-CHM13 v2.0 (no gaps)

Ensembl

The

Ensembl

Ensembl genome database project is a scientific project at the European Bioinformatics Institute, which provides a centralized resource for geneticists, molecular biologists and other researchers studying the genomes of our own species and other v ...

Genome Browser Project

National Library of Medicine Genome Data Viewer (GDV)

UCSC Genome Browser using T2T-CHM13 v2.0

Uniprot: per chromosome gene list

Human Genome Project

The National Human Genome Research Institute

Simple Human Genome viewer

{{DEFAULTSORT:Human Genome Genetic mapping Genomics

Genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

Genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...