Postcolonial Literature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Postcolonial literature is the

Postcolonial fiction writers deal with the traditional colonial

Postcolonial fiction writers deal with the traditional colonial

The ''

The ''

Amadou Hampâté Bâ (1901–1991), a

Amadou Hampâté Bâ (1901–1991), a

"The Many Dimensions of Wole Soyinka"

, ''Vistas'', Loyola Marymount University. Retrieved 17 April 2012. Soyinka has been a strong critic of successive Nigerian governments, especially the country's many military dictators, as well as other political tyrannies, including the Mugabe regime in

Elleke Boehmer writes, "Nationalism, like patriarchy, favours singleness—one identity, one growth pattern, one birth and blood for all ... ndwill promote specifically unitary or 'one-eyed' forms of consciousness." The first problem any student of South African literature is confronted with, is the diversity of the literary systems. Gerrit Olivier notes, "While it is not unusual to hear academics and politicians talk about a 'South African literature', the situation at ground level is characterised by diversity and even fragmentation". Robert Mossman adds that "One of the enduring and saddest legacies of the apartheid system may be that no one – White, Black, Coloured (meaning of mixed-race in South Africa), or Asian – can ever speak as a 'South African. The problem, however, pre-dates

Elleke Boehmer writes, "Nationalism, like patriarchy, favours singleness—one identity, one growth pattern, one birth and blood for all ... ndwill promote specifically unitary or 'one-eyed' forms of consciousness." The first problem any student of South African literature is confronted with, is the diversity of the literary systems. Gerrit Olivier notes, "While it is not unusual to hear academics and politicians talk about a 'South African literature', the situation at ground level is characterised by diversity and even fragmentation". Robert Mossman adds that "One of the enduring and saddest legacies of the apartheid system may be that no one – White, Black, Coloured (meaning of mixed-race in South Africa), or Asian – can ever speak as a 'South African. The problem, however, pre-dates

The term "

The term "

American David Henry Hwang's play '' M. Butterfly'' addresses the Western perspective on China and the French as well as the American perspectives on

American David Henry Hwang's play '' M. Butterfly'' addresses the Western perspective on China and the French as well as the American perspectives on

"Interviews: Jhumpa Lahiri"

"African-American Theory and Criticism"

. Retrieved July 6, 2005.

Major figures in the postcolonial literature of the Middle East included Egyptian novelist

Major figures in the postcolonial literature of the Middle East included Egyptian novelist

''

The English language was introduced to

The English language was introduced to

Postcolonial Readings of Romanian Identity Narratives

/ref>

literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

by people from formerly colonized countries, originating from all continent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention (norm), convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as ...

s except Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean (also known as the Antarctic Ocean), it contains the geographic South Pole. ...

. Postcolonial

Postcolonialism (also post-colonial theory) is the critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic consequences of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and extractivism, exploitation of colonized pe ...

literature often addresses the problems and consequences of the colonization

475px, Map of the year each country achieved List of sovereign states by date of formation, independence.

Colonization (British English: colonisation) is a process of establishing occupation of or control over foreign territories or peoples f ...

and subsequent decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

of a country, especially questions relating to the political and cultural independence of formerly subjugated people, and themes such as racialism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that the human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called " races", and that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racial discri ...

and colonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

. A range of literary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

has evolved around the subject. It addresses the role of literature in perpetuating and challenging what postcolonial critic Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of Postcolonialism, post-co ...

refers to as cultural imperialism

Cultural imperialism (also cultural colonialism) comprises the culture, cultural dimensions of imperialism. The word "imperialism" describes practices in which a country engages culture (language, tradition, ritual, politics, economics) to creat ...

. It is at its most overt in texts that write back to the European canon (Thieme 2001).

Migrant literature

Migrant literature, sometimes written by migrants themselves, tells stories of immigration.

Settings

Although any experience of migration would qualify an author to be classed under migrant literature, the main focus of recent research has been on ...

and postcolonial literature show some considerable overlap. However, not all migration takes place in a colonial setting, and not all postcolonial literature deals with migration. A question of current debate is the extent to which postcolonial theory also speaks to migration literature in non-colonial settings.

Terminology

The significance of the prefix "post-" in "postcolonial" is a matter of contention among scholars and historians. In postcolonial studies, there has not been a unified consensus on whencolonialism

Colonialism is the control of another territory, natural resources and people by a foreign group. Colonizers control the political and tribal power of the colonised territory. While frequently an Imperialism, imperialist project, colonialism c ...

began and when it has ended (with numerous scholars contending that it has not). The contention has been influenced by the history of colonialism

The phenomenon of colonization is one that stretches around the globe and across time. Ancient and medieval colonialism was practiced by various civilizations such as the Phoenicians, Babylonia, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Roman Empire, Rom ...

, which is commonly divided into several major phases; the European colonization of the Americas

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. The Norse explored and colonized areas of Europe a ...

began in the 15th century and lasted until the 19th, while the colonisation of Africa

External colonies were first founded in Africa Colonies in antiquity, during antiquity. Ancient Greece, Ancient Greeks and Ancient Rome, Romans established colonies on the African continent in North Africa, similar to how they established settl ...

and Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

reached their peak in the 19th century. By the dawn of the 20th century, the vast majority of non-European regions were under European colonial rule; this would last until after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

when anti-colonial independence movements led to the decolonization of Africa, Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

and the Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.'' Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sin ...

. Historians have also expressed differing opinions in regards to the postcolonial status of nations established through settler colonialism

Settler colonialism is a logic and structure of displacement by Settler, settlers, using colonial rule, over an environment for replacing it and its indigenous peoples with settlements and the society of the settlers.

Settler colonialism is ...

, such as the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

and New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. Ongoing neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

in the Global South

Global North and Global South are terms that denote a method of grouping countries based on their defining characteristics with regard to socioeconomics and politics. According to UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Global South broadly com ...

and the effects of colonialism (many of which have persisted after the end of direct colonial rule) have made it difficult to determine whether or not a nation being no longer under colonial rule guarantees its postcolonial status.

Pramod Nayar defines postcolonial literature as "that which negotiates with, contests, and subverts Euro-American ideologies and representations"

Evolution of the term

Before the term "postcolonial literature" gained currency among scholars, "commonwealth literature" was used to refer to writing in English from colonies or nations which belonged to theBritish Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, often referred to as the British Commonwealth or simply the Commonwealth, is an international association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire

The B ...

. Even though the term included literature from Britain, it was most commonly used for writing in English written in British colonies. Scholars of commonwealth literature used the term to designate writing in English that dealt with the topic of colonialism. They advocated for its inclusion in literary curricula, hitherto dominated by the British canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

. However, the succeeding generation of postcolonial critics, many of whom belonged to the post-structuralist

Post-structuralism is a philosophical movement that questions the objectivity or stability of the various interpretive structures that are posited by structuralism and considers them to be constituted by broader systems of Power (social and poli ...

philosophical tradition, took issue with the "commonwealth" label for separating non-British writing from "English" language literature written in Britain. They also suggested that texts in this category frequently presented a short-sighted view on the legacy of colonialism.

Other terms used for English-language literature from former British colonies include terms that designate a national corpus of writing such as Australian

Australian(s) may refer to:

Australia

* Australia, a country

* Australians, citizens of the Commonwealth of Australia

** European Australians

** Anglo-Celtic Australians, Australians descended principally from British colonists

** Aboriginal Aus ...

or Canadian literature

Canadian literature is written in several languages including Canadian English, English, Canadian French, French, and various Indigenous Canadian languages. It is often divided into French- and English-language literatures, which are rooted in th ...

; numerous terms such as "English Literature Other than British and American", "New Literatures in English", "International Literature in English"; and "World Literatures" were coined. These, however, have been dismissed either as too vague or too inaccurate to represent the vast body of dynamic writing emerging from British colonies during and after the period of direct colonial rule. The term "colonial" and "postcolonial" continue to be used for writing emerging during and after the period of colonial rule respectively.

"Post-colonial" or "postcolonial"?

The consensus in the field is that "post-colonial" (with a hyphen) signifies a period that comes chronologically "after" colonialism. "Postcolonial," on the other hand, signals the persisting impact of colonization across time periods and geographical regions. While the hyphen implies that history unfolds in neatly distinguishable stages from pre- to post-colonial, omitting the hyphen creates a comparative framework by which to understand the varieties of local resistance to colonial impact. Arguments in favor of the hyphen suggest that the term "postcolonial" dilutes differences between colonial histories in different parts of the world and that it homogenizes colonial societies. The body of critical writing that participates in these debates is called Postcolonial theory.Critical approaches

Postcolonial fiction writers deal with the traditional colonial

Postcolonial fiction writers deal with the traditional colonial discourse

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. F ...

, either by modifying or by subverting it, or both. Postcolonial literary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

re-examines colonial and postcolonial literature, especially concentrating upon the social discourse between the colonizer and the colonized that shaped and produced the literature. In ''Orientalism

In art history, literature, and cultural studies, Orientalism is the imitation or depiction of aspects of the Eastern world (or "Orient") by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. Orientalist painting, particularly of the Middle ...

'' (1978), Edward Said

Edward Wadie Said (1 November 1935 – 24 September 2003) was a Palestinian-American academic, literary critic, and political activist. As a professor of literature at Columbia University, he was among the founders of Postcolonialism, post-co ...

analyzed the fiction of Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

, Charles Baudelaire

Charles Pierre Baudelaire (, ; ; 9 April 1821 – 31 August 1867) was a French poet, essayist, translator and art critic. His poems are described as exhibiting mastery of rhythm and rhyme, containing an exoticism inherited from the Romantics ...

, and Lautréamont (Isidore-Lucien Ducasse), exploring how they shaped and were influenced by the societal fantasy of European racial superiority. He pioneered the branch of postcolonial criticism called colonial discourse analysis.

Another important theorist of colonial discourse is Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

professor Homi K. Bhabha

Homi Kharshedji Bhabha (; born 1 November 1949) is an Indian people, Indian scholar and Critical Theorist, critical theorist. He is the Anne F. Rothenberg Professor of the Humanities at Harvard University. He is one of the most important figur ...

, (born 1949). He has developed a number of the field's neologisms and key concepts, such as hybridity

Hybridity, in its most basic sense, refers to mixture. The term originates from biology and was subsequently employed in linguistics and in racial theory in the nineteenth century. Young, Robert. ''Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and ...

, third-space, mimicry

In evolutionary biology, mimicry is an evolved resemblance between an organism and another object, often an organism of another species. Mimicry may evolve between different species, or between individuals of the same species. In the simples ...

, difference, and ambivalence.Huddart, David. "Homi K. Bhabha", Routledge Critical Thinkers, 2006 Western canonical works like Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

's ''The Tempest

''The Tempest'' is a Shakespeare's plays, play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, th ...

,'' Charlotte Brontë

Charlotte Nicholls (; 21 April 1816 – 31 March 1855), commonly known as Charlotte Brontë (, commonly ), was an English novelist and poet, the eldest of the three Brontë family, Brontë sisters who survived into adulthood and whose novel ...

's ''Jane Eyre

''Jane Eyre'' ( ; originally published as ''Jane Eyre: An Autobiography'') is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The firs ...

,'' Jane Austen

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for #List of works, her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment on the English landed gentry at the end of the 18th century ...

's ''Mansfield Park

''Mansfield Park'' is the third published novel by the English author Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton (publisher), Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray (publishing house), John Murray, st ...

,'' Rudyard Kipling

Joseph Rudyard Kipling ( ; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)''The Times'', (London) 18 January 1936, p. 12. was an English journalist, novelist, poet, and short-story writer. He was born in British Raj, British India, which inspired much ...

's '' Kim,'' and Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

's ''Heart of Darkness

''Heart of Darkness'' is an 1899 novella by Polish-British novelist Joseph Conrad in which the sailor Charles Marlow tells his listeners the story of his assignment as steamer captain for a Belgium, Belgian company in the African interior. Th ...

'' have been targets of colonial discourse analysis. The succeeding generation of postcolonial critics focus on texts that " write back" to the colonial center. In general, postcolonial theory analyzes how anti-colonial ideas, such as anti-conquest, national unity, ''négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, mainly developed by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians in the Africa ...

'', pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

and postcolonial feminism

Postcolonial feminism is a form of feminism that developed as a response to feminism focusing solely on the experiences of women in Western cultures and former colonies. Postcolonial feminism seeks to account for the way that racism and the long- ...

were forged in and promulgated through literature. Prominent theorists include Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (; born 24 February 1942) is an Indian scholar, literary theorist, and feminist critic. She is a University Professor at Columbia University and a founding member of the establishment's Institute for Comparative ...

, Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

, Bill Ashcroft, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (; born James Ngugi; 5January 193828May 2025) was a Kenyan author and academic, who has been described as East Africa's leading novelist and an important figure in modern African literature.

Ngũgĩ wrote primarily in Eng ...

, Chinua Achebe, Leela Gandhi, Gareth Griffiths, Abiola Irele, John McLeod, Hamid Dabashi, Helen Tiffin, Khal Torabully, and Robert J. C. Young.

Nationalism

The sense of identification with a nation, ornationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

, fueled anti-colonial movements that sought to gain independence from colonial rule. Language and literature were factors in consolidating this sense of national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language".

National identity ...

to resist the impact of colonialism. With the advent of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in whi ...

, newspapers and magazines helped people across geographical barriers identify with a shared national community. This idea of the nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

as a homogeneous imagined community

An imagined community is a concept developed by Benedict Anderson in his 1983 book '' Imagined Communities'' to analyze nationalism. Anderson depicts a nation as a socially-constructed community, imagined by the people who perceive themselves a ...

connected across geographical barriers through the medium of language became the model for the modern nation. Postcolonial literature not only helped consolidate national identity in anti-colonial struggles but also critiqued the European colonial pedigree of nationalism. As depicted in Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie ( ; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British and American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern wor ...

's novels for example, the homogeneous nation was built on European models by the exclusion of marginalized voices. They were made up of religious or ethnic elites who spoke on behalf of the entire nation, silencing minority groups.

Negritude, pan-Africanism and pan-nationalism

''Négritude

''Négritude'' (from French "nègre" and "-itude" to denote a condition that can be translated as "Blackness") is a framework of critique and literary theory, mainly developed by francophone intellectuals, writers, and politicians in the Africa ...

'' is a literary and ideological philosophy, developed by francophone African intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

, writers, and politicians in France during the 1930s. Its initiators included Martinican poet Aimé Césaire

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (; ; 26 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a French poet, author, and politician from Martinique. He was "one of the founders of the Négritude movement in Francophone literature" and coined the word in French. He ...

, Léopold Sédar Senghor (a future President of Senegal), and Léon Damas of French Guiana. Négritude intellectuals disapproved of French colonialism and claimed that the best strategy to oppose it was to encourage a common racial identity for native Africans worldwide.

Pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

was a movement among English-speaking black intellectuals who echoed the principles négritude. Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

(1925–1961), a Martinique

Martinique ( ; or ; Kalinago language, Kalinago: or ) is an island in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the eastern Caribbean Sea. It was previously known as Iguanacaera which translates to iguana island in Carib language, Kariʼn ...

-born Afro-Caribbean

Afro-Caribbean or African Caribbean people are Caribbean people who trace their full or partial ancestry to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the modern Afro-Caribbean people descend from the Indigenous peoples of Africa, Africans (primarily fr ...

psychiatrist, philosopher, revolutionary, and writer, was one of the proponents of the movement. His works are influential in the fields of postcolonial studies, critical theory

Critical theory is a social, historical, and political school of thought and philosophical perspective which centers on analyzing and challenging systemic power relations in society, arguing that knowledge, truth, and social structures are ...

, and Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

. As an intellectual, Fanon was a political radical and Marxist humanist concerned with the psychopathology

Psychopathology is the study of mental illness. It includes the signs and symptoms of all mental disorders. The field includes Abnormal psychology, abnormal cognition, maladaptive behavior, and experiences which differ according to social norms ...

of colonization, and the human, social, and cultural consequences of decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

.

Back to Africa movement

Marcus Mosiah Garvey, Jr. (1887–1940), another proponent of Pan-Africanism, was a Jamaican political leader, publisher, journalist, entrepreneur, andorator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14 ...

. He founded the Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League (UNIA-ACL). He also founded the Black Star Line, a shipping and passenger line which promoted the return of the African diaspora

The African diaspora is the worldwide collection of communities descended from List of ethnic groups of Africa, people from Africa. The term most commonly refers to the descendants of the native West Africa, West and Central Africans who were ...

to their ancestral lands. Prior to the 20th century, leaders such as Prince Hall

Prince Hall (December 7, 1807) was an American Abolitionism in the United States, abolitionist and leader in the Free negro, free black community in Boston. He founded Prince Hall Freemasonry and lobbied for Right to education, education rights ...

, Martin Delany, Edward Wilmot Blyden, and Henry Highland Garnet advocated the involvement of the African diaspora in African affairs. However, Garvey was unique in advancing a Pan-African philosophy to inspire a global mass movement and economic empowerment focusing on Africa. The philosophy came to be known as Garveyism. Promoted by the UNIA as a movement of ''African Redemption'', Garveyism would eventually inspire others, ranging from the Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam (NOI) is a religious organization founded in the United States by Wallace Fard Muhammad in 1930. A centralized and hierarchical organization, the NOI is committed to black nationalism and focuses its attention on the Afr ...

to the Rastafari

Rastafari is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic religion that developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It is classified as both a new religious movement and a social movement by Religious studies, scholars of religion. There is no central authori ...

movement (some sects of which proclaim Garvey as a prophet).

Against advocates of literature that promoted African racial solidarity in accordance with negritude principles, Frantz Fanon

Frantz Omar Fanon (, ; ; 20 July 1925 – 6 December 1961) was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, and Marxist from the French colony of Martinique (today a French department). His works have become influential in the ...

argued for a national literature aimed at achieving national liberation. Paul Gilroy argued against reading literature both as an expression of a common black racial identity and as a representation of nationalist sentiments. Rather, he argued that black cultural forms—including literature—were diasporic and transnational formations born out of the common historical and geographical effects of transatlantic slavery.

Anti-conquest

The "anti-conquest narrative" recasts the indigenous inhabitants of colonized countries as victims rather than foes of the colonisers. This depicts the colonised people in a more human light but risks absolving colonisers of responsibility by assuming that native inhabitants were "doomed" to their fate. In her book ''Imperial Eyes,'' Mary Louise Pratt analyzes the strategies by which European travel writing portrays Europe as a secure home space against a contrasting representation of colonized outsiders. She proposes a completely different theorization of "anti-conquest" than the ideas discussed here, one that can be traced to Edward Said. Instead of referring to how natives resist colonization or are victims of it, Pratt analyzes texts in which a European narrates his adventures and struggles to survive in the land of the non-European Other."Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation" (1992). In chapters 3 and 4, titled, "Narrating the Anti-Conquest" and "Anti-Conquest II: Mystique of Reciprocity". This secures the innocence of the imperialist even as he exercises his dominance, a strategy Pratt terms "anti-conquest." The anti-conquest is a function of how the narrator writes him or her self out of being responsible for or an agent, direct or indirect, of colonization and colonialism. This different notion of anti-conquest is used to analyze the ways in which colonialism and colonization are legitimized through stories of survival and adventure that purport to inform or entertain. Pratt created this unique notion in association with concepts of contact zone andtransculturation

Transculturation is a term coined by Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz in 1940 to describe the phenomenon of merging and converging cultures. Transculturation encompasses more than transition from one culture to another; it does not consist me ...

, which have been very well received in Latin America social and human science circles. The terms refer to the conditions and effects of encounter between the colonizer and the colonized.

Postcolonial feminist literature

Postcolonial feminism

Postcolonial feminism is a form of feminism that developed as a response to feminism focusing solely on the experiences of women in Western cultures and former colonies. Postcolonial feminism seeks to account for the way that racism and the long- ...

emerged as a response to the Eurocentric focus of feminism

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

. It accounts for the way that racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

and the long-lasting political, economic, and cultural effects of colonialism affect non-white, non-Western women in the postcolonial world. Postcolonial feminism is not simply a subset of postcolonial studies or another variety of feminism. Rather, it seeks to act as an intervention that changes the assumptions of both postcolonial and feminist studies.Audre Lorde

Audre Lorde ( ; born Audrey Geraldine Lorde; February 18, 1934 – November 17, 1992) was an American writer, professor, philosopher, Intersectional feminism, intersectional feminist, poet and civil rights activist. She was a self-described "Bl ...

's foundational essay, "The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House", uses the metaphor of the master's tools and master's house to explain that western feminism fails to make positive change for third world women because it uses the same tools as the patriarchy. Postcolonial feminist fiction seeks to decolonize the imagination and society. With global debt, labor, and environmental crises one the rise, the precarious position of women (especially in the global south) has become a prevalent concern of postcolonial feminist novels. Common themes include women's roles in globalized societies and the impact of mass migration to metropolitan urban centers. Pivotal texts, including Nawal El Saadawi's The Fall of the Iman about the lynching of women, Chimamanda Adichie's ''Half of a Yellow Sun

''Half of a Yellow Sun'' is a 2006 novel by Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It became instantly successful after its publication; in the United States and Nigeria, it is widely read in high schools and middle schools. ''Half of a Y ...

'' about two sisters in pre and post war Nigeria, and Giannina Braschi

Giannina Braschi (born February 5, 1953) is a Puerto Rican poet, novelist, dramatist, and scholar. Her notable works include '' Empire of Dreams'' (1988), '' Yo-Yo Boing!'' (1998), '' United States of Banana'' (2011), and '' Putinoika'' (2024). ...

's United States of Banana which declares the independence of Puerto Rico. Other major voices include Maryse Condé, Fatou Diome, and Marie NDiaye.

Postcolonial feminist cultural theorists include Rey Chow, Maria Lugones, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (; born 24 February 1942) is an Indian scholar, literary theorist, and feminist critic. She is a University Professor at Columbia University and a founding member of the establishment's Institute for Comparative ...

, and Trinh T. Minh-ha

Trinh T. Minh-ha (born 1952 in Hanoi; Vietnamese: Trịnh Thị Minh Hà) is a Vietnamese filmmaker, writer, literary theorist, composer, and professor. She has been making films since the 1980s and is best known for her films Reassemblage (film ...

.

Pacific Islands

The ''

The ''Pacific Islands

The Pacific islands are a group of islands in the Pacific Ocean. They are further categorized into three major island groups: Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Depending on the context, the term ''Pacific Islands'' may refer to one of several ...

'' comprise 20,000 to 30,000 island

An island or isle is a piece of land, distinct from a continent, completely surrounded by water. There are continental islands, which were formed by being split from a continent by plate tectonics, and oceanic islands, which have never been ...

s in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. Depending on the context, it may refer to countries and islands with common Austronesian origins, islands once or currently colonized, or Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

.

There is a burgeoning group of young pacific writers who respond and speak to the contemporary Pasifika experience, including writers Lani Wendt Young, Courtney Sina Meredith and Selina Tusitala Marsh. Reclamation of culture, loss of culture, diaspora

A diaspora ( ) is a population that is scattered across regions which are separate from its geographic place of birth, place of origin. The word is used in reference to people who identify with a specific geographic location, but currently resi ...

, all themes common to postcolonial literature, are present within the collective Pacific writers. Pioneers of the literature include two of the most influential living authors from this region: Witi Ihimaera

Witi Tame Ihimaera-Smiler (; born 7 February 1944) is a New Zealand author. Raised in the small town of Waituhi, he decided to become a writer as a teenager after being convinced that Māori people, Māori people were ignored or mischaracteri ...

, New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

's first published Māori novelist, and Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

n poet Albert Wendt (born 1939). Wendt lives in New Zealand. Among his works is ''Leaves of the Banyan Tree'' (1979). He is of German heritage through his paternal great-grandfather, which is reflected in some of his poems. He describes his family heritage as "totally Samoan", even though he has a German surname. However, he does not explicitly deny his German heritage.

Another notable figure from the region is Sia Figiel (born 1967), a contemporary Samoan novelist, poet, and painter, whose debut novel ''Where We Once Belonged'' won the Commonwealth Writers' Prize ''Best First Book of 1997,'' ''South East Asia and South Pacific Region''. Sia Figiel grew up amidst traditional Samoan singing and poetry, which heavily influenced her writing. Figiel's greatest influence and inspiration in her career is the Samoan novelist and poet, Albert Wendt.

Australia

At the point of the first colonization of Australia from 1788,Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are people with familial heritage from, or recognised membership of, the various ethnic groups living within the territory of contemporary Australia prior to History of Australia (1788–1850), British colonisation. The ...

( Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Torres Strait Islanders ( ) are the Indigenous Melanesians, Melanesian people of the Torres Strait Islands, which are part of the state of Queensland, Australia. Ethnically distinct from the Aboriginal Australians, Aboriginal peoples of the res ...

people) had not developed a system of writing, so the first literary accounts of Aboriginal peoples come from the journals of early European explorers, which contain descriptions of first contact, both violent and friendly. Early accounts by Dutch explorers and the English buccaneer William Dampier wrote of the "natives of New Holland" as being "barbarous savages", but by the time of Captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

and First Fleet

The First Fleet were eleven British ships which transported a group of settlers to mainland Australia, marking the beginning of the History of Australia (1788–1850), European colonisation of Australia. It consisted of two Royal Navy vessel ...

marine Watkin Tench (the era of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

), accounts of Aboriginal peoples were more sympathetic and romantic: "these people may truly be said to be in the pure state of nature, and may appear to some to be the most wretched upon the earth; but in reality they are far happier than ... we Europeans", wrote Cook in his journal on 23 August 1770.

While his father, James Unaipon (c. 1835–1907), contributed to accounts of Aboriginal mythology

Australian Aboriginal religion and mythology is the sacred spirituality represented in the stories performed by Aboriginal Australians within each of the Aboriginal Australian languages, language groups across Australia in their Aboriginal c ...

written by the South Australian missionary George Taplin, David Unaipon

David Ngunaitponi (28 September 1872 – 7 February 1967), known as David Unaipon, was an Aboriginal Australian preacher, inventor, and author. A Ngarrindjeri man, his contribution to Australian society helped to break many stereotypes of Abo ...

(1872–1967) provided the first accounts of Aboriginal mythology written by an Aboriginal person in his ''Legendary Tales of the Australian Aborigines''. For this he is known as the first Aboriginal author.

Oodgeroo Noonuccal (born Kath Walker, 1920–1995) was an Australian poet, political activist, artist and educator. She was also a campaigner for Aboriginal rights. Oodgeroo was best known for her poetry, and was the first Aboriginal Australian to publish a book of verse, ''We Are Going'' (1964).

Sally Morgan's novel '' My Place'' (1987) was considered a breakthrough memoir in terms of bringing Indigenous stories to wider notice. Leading Aboriginal activists Marcia Langton ('' First Australians'', 2008) and Noel Pearson (''Up From the Mission'', 2009) are active contemporary contributors to Australian literature

Australian literature is the literature, written or literary work produced in the area or by the people of the Australia, Commonwealth of Australia and its preceding colonies. During its early Western culture, Western history, Australia was a ...

.

The voices of Indigenous Australians continue to be increasingly noticed, and include the playwright Jack Davis and Kevin Gilbert. Writers coming to prominence in the 21st century include Kim Scott, Alexis Wright

Alexis Wright (born 25 November 1950) is an Aboriginal Australian writer. She is best known for winning the Miles Franklin Award for her 2006 novel '' Carpentaria''. She was the first writer to win the Stella Prize twice, in 2018 for her "colle ...

, Kate Howarth, Tara June Winch, in poetry Yvette Holt and in popular fiction Anita Heiss.

Indigenous authors who have won Australia's high prestige Miles Franklin Award

The Miles Franklin Literary Award is an annual literary prize awarded to "a novel which is of the highest literary merit and presents Australian life in any of its phases". The award was set up according to the Will (law), will of Miles Franklin ...

include Kim Scott who was joint winner (with Thea Astley) in 2000 for '' Benang'' and again in 2011 for '' That Deadman Dance.'' Alexis Wright won the award in 2007 for her novel '' Carpentaria''.

Bruce Pascoe's '' Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident?'' (2014), which, based on research already done by others but rarely included in standard historical narratives, reexamines colonial accounts of Aboriginal people in Australia and cites evidence of pre-colonial agriculture

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created ...

, engineering

Engineering is the practice of using natural science, mathematics, and the engineering design process to Problem solving#Engineering, solve problems within technology, increase efficiency and productivity, and improve Systems engineering, s ...

and building construction

Construction are processes involved in delivering buildings, infrastructure, industrial facilities, and associated activities through to the end of their life. It typically starts with planning, financing, and design that continues until the a ...

by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. The book won much acclaim, winning the Book of the Year in the NSW Premier's Literary Award and others, as well as selling very well: by 2019 it was in its 28the printing and had sold over 100,000 copies.

Many notable works have been written by non-Indigenous Australians on Aboriginal themes. Eleanor Dark's (1901–1985) '' The Timeless Land'' (1941) is the first of ''The Timeless Land'' trilogy of novels about European settlement and exploration of Australia. The narrative is told from European and Aboriginal points of view. Other examples include the poems of Judith Wright, ''The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith

''The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith'' is a 1972 Booker Prize-nominated Australian novel by Thomas Keneally, and a 1978 Australian film of the same name directed by Fred Schepisi. The novel is based on the life of bushranger Jimmy Governor, the ...

'' by Thomas Keneally

Thomas Michael Keneally, Officer of the Order of Australia, AO (born 7 October 1935) is an Australian novelist, playwright, essayist, and actor. He is best known for his historical fiction novel ''Schindler's Ark'', the story of Oskar Schindler' ...

, ''Ilbarana'' by Donald Stuart, and the short story by David Malouf

David George Joseph Malouf (; born 20 March 1934) is an Australian poet, novelist, short story writer, playwright and Libretto, librettist. Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2008, Malouf has lectured at both the University ...

: "The Only Speaker of his Tongue".

Africa

Mali

Mali, officially the Republic of Mali, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is the List of African countries by area, eighth-largest country in Africa, with an area of over . The country is bordered to the north by Algeria, to the east b ...

an writer and ethnologist, and Ayi Kwei Armah (born 1939) from Ghana

Ghana, officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa. It is situated along the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, and shares borders with Côte d’Ivoire to the west, Burkina Faso to the north, and Togo to t ...

, author of '' Two Thousand Seasons'' have tried to establish an African perspective to their own history. Another significant African novel is ''Season of Migration to the North

''Season of Migration to the North'' ( ) is novel by the Sudanese writer Tayeb Salih, first published serially in the Beirut journal '' Hiwâr'' in 1966. It became Salih's best known work and is considered a classic of postcolonial literature. T ...

'' by Tayib Salih from the Sudan

Sudan, officially the Republic of the Sudan, is a country in Northeast Africa. It borders the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, Libya to the northwest, Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the east, Eritrea and Ethiopi ...

.

Doris Lessing (1919–2013) from Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing British Crown colony in Southern Africa, established in 1923 and consisting of British South Africa Company (BSAC) territories lying south of the Zambezi River. The region was informally known as South ...

, now Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

, published her first novel '' The Grass is Singing'' in 1950, after immigrating to England. She initially wrote about her African experiences. Lessing soon became a dominant presence in the English literary scene, frequently publishing right through the century, and won the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 2007. Yvonne Vera

Yvonne Vera (19 September 1964 – 7 April 2005) was an author from Zimbabwe. Her first published book was a collection of short stories, ''Why Don't You Carve Other Animals'' (1992), which was followed by five novels: ''Nehanda'' (1993), ''With ...

(1964–2005) was an author from Zimbabwe. Her novels are known for their poetic prose, difficult subject-matter, and their strong women characters, and are firmly rooted in Zimbabwe's difficult past. Tsitsi Dangarembga (born 1959) is a notable Zimbabwean author and filmmaker.

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o (; born James Ngugi; 5January 193828May 2025) was a Kenyan author and academic, who has been described as East Africa's leading novelist and an important figure in modern African literature.

Ngũgĩ wrote primarily in Eng ...

(born 1938) is a Kenyan writer, formerly working in English and now working in Gikuyu. His work includes novels, plays, short stories, and essays, ranging from literary and social criticism to children's literature. He is the founder and editor of the Gikuyu-language journal '' Mũtĩiri''.

Stephen Atalebe (born 1983) is a Ghanaian Fiction writer who wrote the Hour of Death in Harare, detailing the post-colonial struggles in Zimbabwe as they navigate through sanctions imposed by the British Government under George Blair.

Bate Besong (1954–2007) was a Cameroon

Cameroon, officially the Republic of Cameroon, is a country in Central Africa. It shares boundaries with Nigeria to the west and north, Chad to the northeast, the Central African Republic to the east, and Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, and the R ...

ian playwright, poet and critic, who was described by Pierre Fandio as "one of the most representative and regular writers of what might be referred to as the second generation of the emergent Cameroonian literature in English". Other Cameroonian playwrights are Anne Tanyi-Tang, and Bole Butake.

Dina Salústio (born 1941) is a Cabo Verdean novelist and poet, whose works are considered an important contribution to Lusophone postcolonial literature, with a particular emphasis on their promotion of women's narratives.

Nigeria

Nigerian author Chinua Achebe (1930–2013) gained worldwide attention for ''Things Fall Apart

''Things Fall Apart'' is a 1958 novel by Nigerian author Chinua Achebe. It is Achebe's debut novel and was written when he was working at the Nigerian Broadcasting Corporation. The novel was first published in London by Heinemann (publisher), ...

'' in the late 1950s. Achebe wrote his novels in English and defended the use of English, a "language of colonisers", in African literature. In 1975, his lecture " An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad's ''Heart of Darkness''" featured a famous criticism of Joseph Conrad

Joseph Conrad (born Józef Teodor Konrad Korzeniowski, ; 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Poles in the United Kingdom#19th century, Polish-British novelist and story writer. He is regarded as one of the greatest writers in the Eng ...

as "a thoroughgoing racist". A titled Igbo chieftain

A tribal chief, chieftain, or headman is a leader of a tribe, tribal society or chiefdom.

Tribal societies

There is no definition for "tribe".

The concept of tribe is a broadly applied concept, based on tribal concepts of societies of weste ...

himself, Achebe's novels focus on the traditions of Igbo society, the effect of Christian influences, and the clash of Western and traditional African values during and after the colonial era. His style relies heavily on the Igbo oral tradition, and combines straightforward narration with representations of folk stories, proverbs, and oratory. He also published a number of short stories, children's books, and essay collections.

Wole Soyinka

Wole Soyinka , (born 13 July 1934) is a Nigerian author, best known as a playwright and poet. He has written three novels, ten collections of short stories, seven poetry collections, twenty five plays and five memoirs. He also wrote two transla ...

(born 1934) is a playwright and poet, who was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

, the first African to be honored in that category. Soyinka was born into a Yoruba family in Abeokuta. After studying in Nigeria

Nigeria, officially the Federal Republic of Nigeria, is a country in West Africa. It is situated between the Sahel to the north and the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to the south. It covers an area of . With Demographics of Nigeria, ...

and Great Britain, he worked with the Royal Court Theatre

The Royal Court Theatre, at different times known as the Court Theatre, the New Chelsea Theatre, and the Belgravia Theatre, is a West End theatre#London's non-commercial theatres, non-commercial theatre in Sloane Square, London, England, opene ...

in London. He went on to write plays that were produced in both countries, in theatres and on radio. He took an active role in Nigeria's political history and its campaign for independence from British colonial rule. In 1965, he seized the Western Nigeria Broadcasting Service studio and broadcast a demand for the cancellation of the Western Nigeria Regional Elections. In 1967 during the Nigerian Civil War

The Nigerian Civil War (6 July 1967 – 15 January 1970), also known as the Biafran War, Nigeria-Biafra War, or Biafra War, was fought between Nigeria and the Republic of Biafra, a Secession, secessionist state which had declared its independen ...

, he was arrested by the federal government of General Yakubu Gowon and put in solitary confinement for two years.Theresia de Vroom"The Many Dimensions of Wole Soyinka"

, ''Vistas'', Loyola Marymount University. Retrieved 17 April 2012. Soyinka has been a strong critic of successive Nigerian governments, especially the country's many military dictators, as well as other political tyrannies, including the Mugabe regime in

Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

. Much of his writing has been concerned with "the oppressive boot and the irrelevance of the colour of the foot that wears it".

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie (born Grace Ngozi Adichie; 15 September 1977) is a Nigerians, Nigerian writer of novels, short stories, poem, and children's books; she is also a book reviewer and literary critic. Her most famous works include ''Purple ...

(born 1977) is a novelist, nonfiction writer and short story writer. A MacArthur Genius Grant recipient, Adichie has been called "the most prominent" of a "procession of critically acclaimed young anglophone authors hat

A hat is a Headgear, head covering which is worn for various reasons, including protection against weather conditions, ceremonial reasons such as university graduation, religious reasons, safety, or as a fashion accessory. Hats which incorpor ...

is succeeding in attracting a new generation of readers to African literature".

Buchi Emecheta OBE (1944–2017) was a Nigerian novelist based in Britain who published more than 20 books, including ''Second-Class Citizen

A second-class citizen is a person who is systematically and actively discriminated against within a state or other political jurisdiction, despite their nominal status as a citizen or a legal resident there. While not necessarily slaves, ou ...

'' (1974), '' The Bride Price'' (1976), '' The Slave Girl'' (1977) and '' The Joys of Motherhood'' (1979). Her themes of child slavery, motherhood, female independence and freedom through education won her considerable critical acclaim and honours.

South Africa

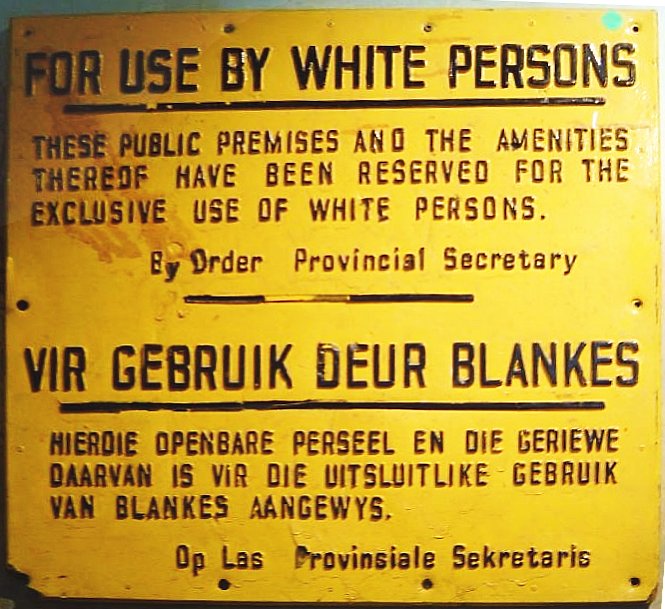

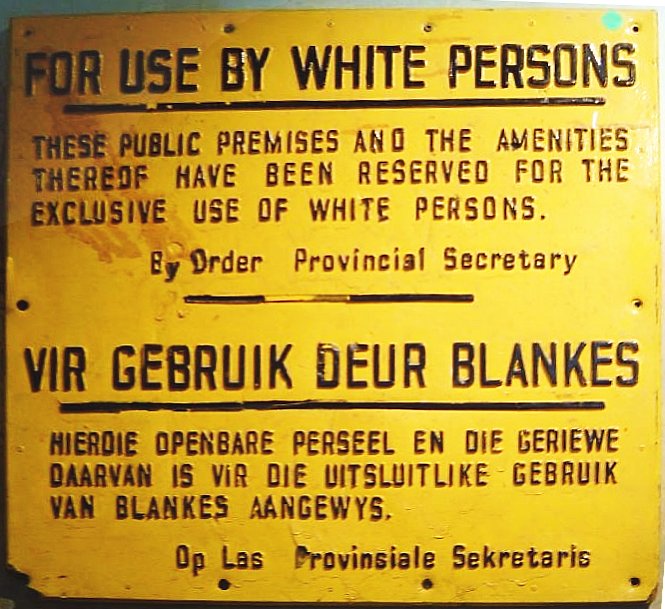

Elleke Boehmer writes, "Nationalism, like patriarchy, favours singleness—one identity, one growth pattern, one birth and blood for all ... ndwill promote specifically unitary or 'one-eyed' forms of consciousness." The first problem any student of South African literature is confronted with, is the diversity of the literary systems. Gerrit Olivier notes, "While it is not unusual to hear academics and politicians talk about a 'South African literature', the situation at ground level is characterised by diversity and even fragmentation". Robert Mossman adds that "One of the enduring and saddest legacies of the apartheid system may be that no one – White, Black, Coloured (meaning of mixed-race in South Africa), or Asian – can ever speak as a 'South African. The problem, however, pre-dates

Elleke Boehmer writes, "Nationalism, like patriarchy, favours singleness—one identity, one growth pattern, one birth and blood for all ... ndwill promote specifically unitary or 'one-eyed' forms of consciousness." The first problem any student of South African literature is confronted with, is the diversity of the literary systems. Gerrit Olivier notes, "While it is not unusual to hear academics and politicians talk about a 'South African literature', the situation at ground level is characterised by diversity and even fragmentation". Robert Mossman adds that "One of the enduring and saddest legacies of the apartheid system may be that no one – White, Black, Coloured (meaning of mixed-race in South Africa), or Asian – can ever speak as a 'South African. The problem, however, pre-dates Apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

significantly, as South Africa is a country made up of communities that have always been linguistically and culturally diverse. These cultures have all retained autonomy to some extent, making a compilation such as the controversial ''Southern African Literatures'' by Michael Chapman, difficult. Chapman raises the question:

ose language, culture, or story can be said to have authority in South Africa when the end of apartheid has raised challenging questions as to what it is to be a South African, what it is to live in a new South Africa, whether South Africa is a nation, and, if so, what its mythos is, what requires to be forgotten and what remembered as we scour the past in order to understand the present and seek a path forward into an unknown future.South Africa has 11 national languages:

Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

, English, Zulu, Xhosa, Sotho, Pedi, Tswana, Venda, SiSwati, Tsonga

Tsonga may refer to:

* Tsonga language, a Bantu language spoken in southern Africa

* Tsonga people, a large group of people living mainly in southern Mozambique and South Africa.

* Jo-Wilfried Tsonga

Jo-Wilfried Tsonga (; born 17 April 1985) ...

, and Ndebele. Any definitive literary history of South Africa should, it could be argued, discuss literature produced in all eleven languages. But the only literature ever to adopt characteristics that can be said to be "national" is Afrikaans. Olivier argues: "Of all the literatures in South Africa, Afrikaans literature has been the only one to have become a national literature in the sense that it developed a clear image of itself as a separate entity, and that by way of institutional entrenchment through teaching, distribution, a review culture, journals, etc. it could ensure the continuation of that concept." Part of the problem is that English literature has been seen within the greater context of English writing in the world, and has, because of English's global position as ''lingua franca'', not been seen as autonomous or indigenous to South Africa – in Olivier's words: "English literature in South Africa continues to be a sort of extension of British or international English literature." The African languages, on the other hand, are spoken across the borders of Southern Africa - for example, Tswana is spoken in Botswana, and Tsonga in Zimbabwe, and Sotho in Lesotho. South Africa's borders were established during the colonial era and, as with all other colonies, these borders were drawn without regard for the people living within them. Therefore: in a history of South African literature, do we include all Tswana writers, or only the ones with South African citizenship? Chapman bypasses this problem by including "Southern" African literatures. The second problem with the African languages is accessibility, because since the African languages are regional languages, none of them can claim the readership on a national scale comparable to Afrikaans and English. Sotho, for instance, while transgressing the national borders of the RSA, is on the other hand mainly spoken in the Free State, and bears a great amount of relation to the language of Natal for example, Zulu. So the language cannot claim a national readership, while on the other hand being "international" in the sense that it transgresses the national borders.

Olivier argues that "There is no obvious reason why it should be unhealthy or abnormal for different literatures to co-exist in one country, each possessing its own infrastructure and allowing theoreticians to develop impressive theories about polysystems". Yet political idealism proposing a unified "South Africa" (a remnant of the plans drawn up by Sir Henry Bartle Frere) has seeped into literary discourse and demands a unified national literature, which does not exist and has to be fabricated. It is unrealistic to ever think of South Africa and South African literature as homogenous, now or in the near or distant future, since the only reason it is a country at all is the interference of European colonial powers. This is not a racial issue, but rather has to do with culture, heritage and tradition (and indeed the constitution celebrates diversity). Rather, it seems more sensible to discuss South African literature as literature produced within the national borders by the different cultures and language groups inhabiting these borders. Otherwise the danger is emphasising one literary system at the expense of another, and more often than not, the beneficiary is English, with the African languages being ignored. The distinction "black" and "white" literature is further a remnant of colonialism that should be replaced by drawing distinctions between literary systems based on language affiliation rather than race.

The first texts produced by black authors were often inspired by missionaries and frequently deal with African history, in particular the history of kings such as Chaka. Modern South African writing in the African languages tends to play at writing realistically, at providing a mirror to society, and depicts the conflicts between rural and urban settings, between traditional and modern norms, racial conflicts and most recently, the problem of AIDS.

In the first half of the 20th century, epics largely dominated black writing: historical novels, such as Sol T. Plaatje's '' Mhudi: An Epic of South African Native Life a Hundred Years Ago'' (1930), Thomas Mofolo's '' Chaka'' (trans. 1925), and epic plays including those of H. I. E. Dhlomo, or heroic epic poetry such as the work of Mazizi Kunene. These texts "evince black African patriarchy in its traditional form, with men in authority, often as warriors or kings, and women as background figures of dependency, and/or mothers of the nation". Female literature in the African languages is severely limited because of the strong influence of patriarchy, but over the last decade or two society has changed much and it can be expected that more female voices will emerge.

The following are notable white South African writers in English: Athol Fugard

Harold Athol Lanigan Fugard (; 11 June 19328 March 2025) was a South African playwright, novelist, actor and director. Widely regarded as South Africa's greatest playwright and acclaimed as "the greatest active playwright in the English-speaki ...

, Nadine Gordimer

Nadine Gordimer (20 November 192313 July 2014) was a South African writer and political activist. She received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1991, recognised as a writer "who through her magnificent epic writing has ... been of very great ben ...

, J. M. Coetzee

John Maxwell Coetzee Order of Australia, AC Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, FRSL Order of Mapungubwe, OMG (born 9 February 1940) is a South African and Australian novelist, essayist, linguist, and translator. The recipient of the 2003 ...

, and Wilbur Smith

Wilbur Addison Smith (9 January 1933 – 13 November 2021) was a Northern Rhodesian-born British-South African novelist specializing in historical fiction about international involvement in Southern Africa across four centuries.

He gained a f ...

. André Brink has written in both Afrikaans and English while Breyten Breytenbach

Breyten Breytenbach (; 16 September 193924 November 2024) was a South African writer, poet, and painter. He became internationally well-known as a dissident poet and vocal critic of South Africa under apartheid, and as a political prisoner of ...

writes primarily in Afrikaans, though many of their works have been translated into English. Dalene Matthee's (1938–2005) is another Afrikaner, best known for her four ''Forest Novels'', written in and around the Knysna Forest, including '' Fiela se Kind'' (1985) (''Fiela's Child''). Her books have been translated into fourteen languages, including English, French, and German. and over a million copies have been sold worldwide.

The Americas

Caribbean Islands

Maryse Condé (born 1937) is a French (Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

an) author of historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which a fictional plot takes place in the Setting (narrative), setting of particular real past events, historical events. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literatur ...

, best known for her novel '' Segu'' (1984–1985).

West Indies

The term "

The term "West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

" first began to achieve wide currency in the 1950s, when writers such as Samuel Selvon

Samuel Dickson Selvon (20 May 1923 – 16 April 1994)"Samuel Selvon"

''Encyclop ...

, John Hearne, Edgar Mittelholzer, V.S. Naipaul, and George Lamming began to be published in the United Kingdom. A sense of a single literature developing across the islands was also encouraged in the 1940s by the ''Encyclop ...

BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

radio programme '' Caribbean Voices'', which featured stories and poems written by West Indian authors, recorded in London under the direction of producer Henry Swanzy, and broadcast back to the islands. Magazines such as '' Kyk-Over-Al'' in Guyana, ''Bim

Building information modeling (BIM) is an approach involving the generation and management of digital representations of the physical and functional characteristics of buildings or other physical assets and facilities. BIM is supported by vario ...

'' in Barbados, and ''Focus

Focus (: foci or focuses) may refer to:

Arts

* Focus or Focus Festival, former name of the Adelaide Fringe arts festival in East Australia Film

*Focus (2001 film), ''Focus'' (2001 film), a 2001 film based on the Arthur Miller novel

*Focus (2015 ...

'' in Jamaica, which published work by writers from across the region, also encouraged links and helped build an audience.

Some West Indian writers have found it necessary to leave their home territories and base themselves in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, or Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

in order to make a living from their work—in some cases spending the greater parts of their careers away from the territories of their birth. Critics in their adopted territories might argue that, for instance, V. S. Naipaul ought to be considered a British writer instead of a Trinidadian writer, or Jamaica Kincaid and Paule Marshall American writers, but most West Indian readers and critics still consider these writers "West Indian".

West Indian literature ranges over subjects and themes as wide as those of any other "national" literature, but in general many West Indian writers share a special concern with questions of identity, ethnicity, and language that rise out of the Caribbean historical experience.

One unique and pervasive characteristic of Caribbean literature is the use of "dialect

A dialect is a Variety (linguistics), variety of language spoken by a particular group of people. This may include dominant and standard language, standardized varieties as well as Vernacular language, vernacular, unwritten, or non-standardize ...

" forms of the national language, often termed creole. The various local variations in the European languages

There are over 250 languages indigenous to Europe, and most belong to the Indo-European language family. Out of a total European population of 744 million as of 2018, some 94% are native speakers of an Indo-European language. The three larges ...

which became established in the West Indies during the period of European colonial rule. These languages have been modified over the years within each country and each has developed a blend that is unique to their country. Many Caribbean authors in their writing switch liberally between the local variation – now commonly termed nation language – and the standard form of the language. Two West Indian writers have won the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

: Derek Walcott (1992), born in St. Lucia, resident mostly in Trinidad during the 1960s and '70s, and partly in the United States since then; and V. S. Naipaul, born in Trinidad and resident in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

since the 1950. ( Saint-John Perse, who won the Nobel Prize in 1960, was born in the French territory of Guadeloupe

Guadeloupe is an Overseas departments and regions of France, overseas department and region of France in the Caribbean. It consists of six inhabited islands—Basse-Terre Island, Basse-Terre, Grande-Terre, Guadeloupe, Grande-Terre, Marie-Galant ...

.)

Other notable names in (anglophone) Caribbean literature have included Earl Lovelace, Austin Clarke, Claude McKay

Festus Claudius "Claude" McKay OJ (September 15, 1890See Wayne F. Cooper, ''Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner In The Harlem Renaissance'' (New York, Schocken, 1987) p. 377 n. 19. As Cooper's authoritative biography explains, McKay's family predate ...

, Orlando Patterson, Andrew Salkey, Edward Kamau Brathwaite (who was born in Barbados and has lived in Ghana and Jamaica), Linton Kwesi Johnson, and Michelle Cliff. In more recent times, a number of literary voices have emerged from the Caribbean as well as the Caribbean diaspora, including Kittitian Caryl Phillips (who has lived in the UK since one month of age), Edwidge Danticat, a Haiti