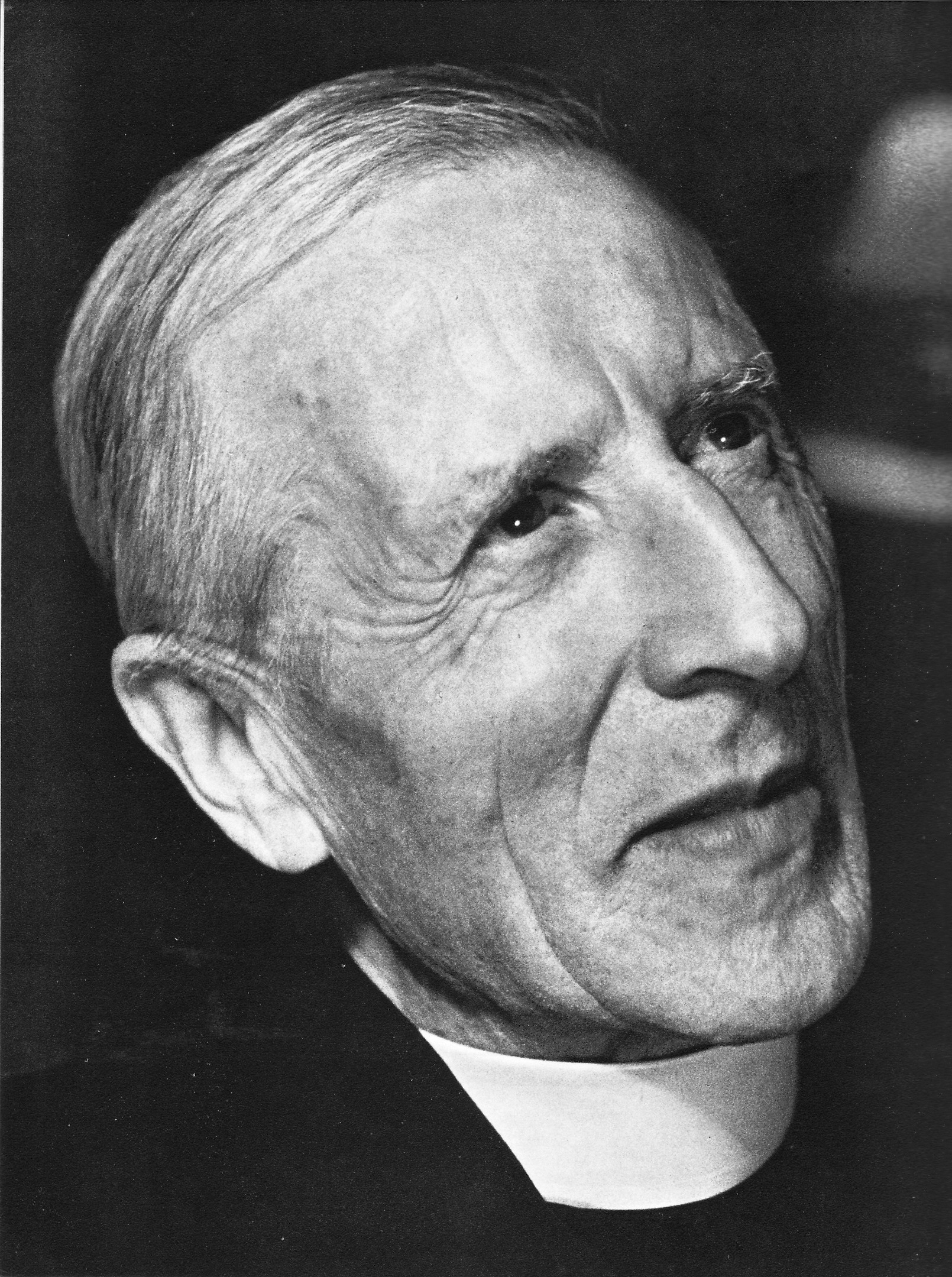

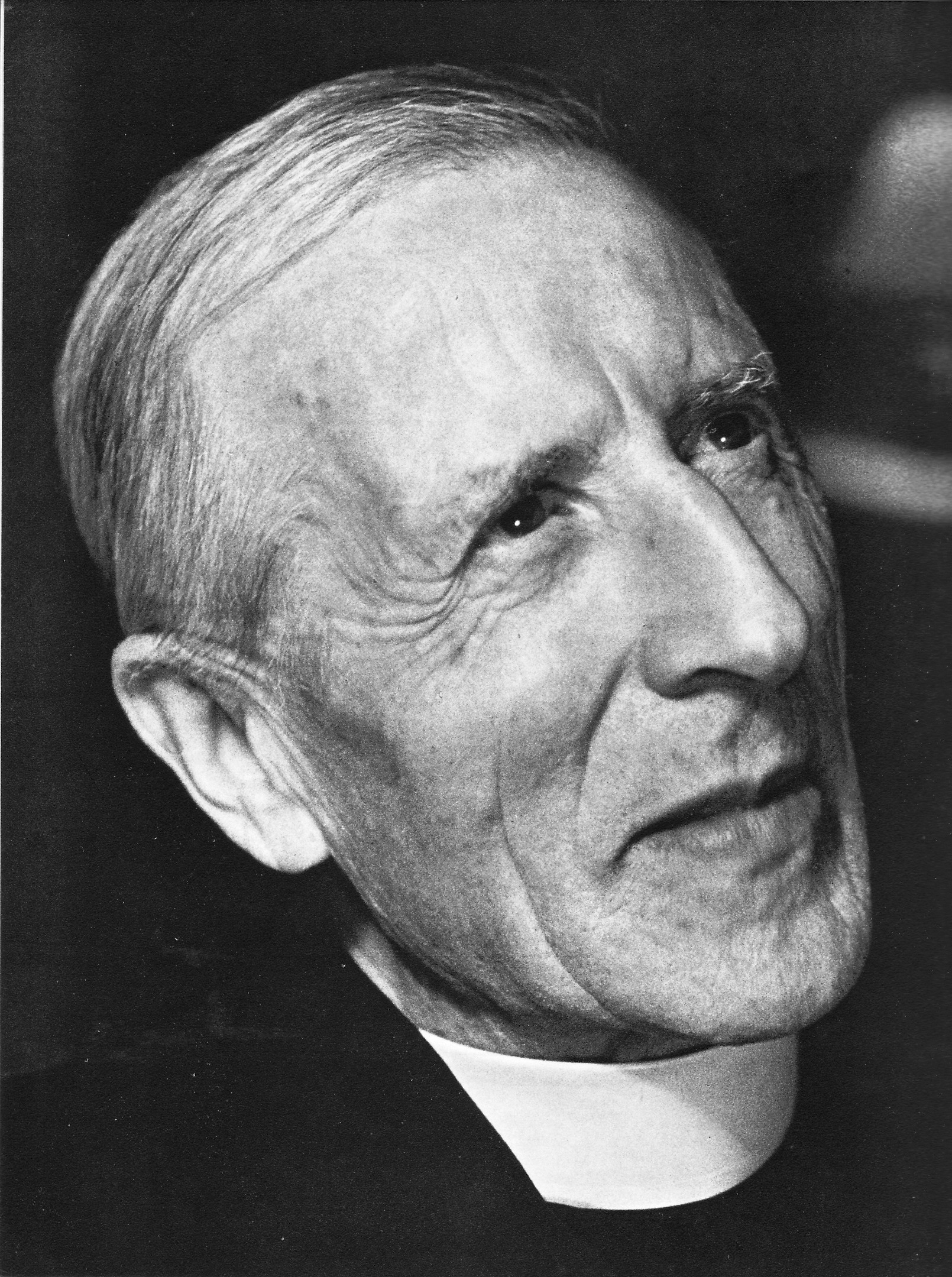

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (; 1 May 1881 – 10 April 1955) was a French

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

,

Catholic priest, scientist,

palaeontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

,

theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

, and teacher. He was

Darwinian and

progressive in outlook and the author of several influential theological and philosophical books. His mainstream scientific achievements include his palaeontological research in China, taking part in the discovery of the significant

Peking Man fossils from the

Zhoukoudian cave complex near Beijing. His more speculative ideas, sometimes criticized as

pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

, have included a

vitalist

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

conception of the

Omega Point. Along with

Vladimir Vernadsky

Vladimir Ivanovich Vernadsky (), also spelt Volodymyr Ivanovych Vernadsky (; – 6 January 1945), was a Russian, Ukrainian, and Soviet mineralogist and geochemist who is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and radio ...

, they also contributed to the development of the concept of a

noosphere.

In 1962, the

Holy Office

The Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) is a department of the Roman Curia in charge of the religious discipline of the Catholic Church. The Dicastery is the oldest among the departments of the Roman Curia. Its seat is the Palace o ...

condemned several of Teilhard's works based on their alleged ambiguities and doctrinal errors. Some eminent Catholic figures, including

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

and

Pope Francis

Pope Francis (born Jorge Mario Bergoglio; 17 December 1936 – 21 April 2025) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 13 March 2013 until Death and funeral of Pope Francis, his death in 2025. He was the fi ...

, have made positive comments on some of his ideas since. The response to his writings by scientists has been divided. Teilhard served in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as a stretcher-bearer. He received several citations, and was awarded the

Médaille militaire and the

Legion of Honor, the highest French

order of merit

The Order of Merit () is an order of merit for the Commonwealth realms, recognising distinguished service in the armed forces, science, art, literature, or the promotion of culture. Established in 1902 by Edward VII, admission into the order r ...

, both military and civil.

Life

Early years

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born in the Château of Sarcenat,

Orcines, about 2.5 miles north-west of

Clermont-Ferrand

Clermont-Ferrand (, , ; or simply ; ) is a city and Communes of France, commune of France, in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes regions of France, region, with a population of 147,284 (2020). Its metropolitan area () had 504,157 inhabitants at the 2018 ...

,

Auvergne,

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

, on 1 May 1881, as the fourth of eleven children of librarian Emmanuel Teilhard de Chardin (1844–1932) and Berthe-Adèle, née de Dompierre d'Hornoys of

Picardy

Picardy (; Picard language, Picard and , , ) is a historical and cultural territory and a former regions of France, administrative region located in northern France. The first mentions of this province date back to the Middle Ages: it gained it ...

. His mother was a great-grandniece of the philosopher

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

. He inherited the double surname from his father, who was descended on the Teilhard side from an ancient family of magistrates from

Auvergne originating in

Murat, Cantal

Murat () is a commune in the Cantal department in the Auvergne region in south-central France. On 1 January 2017, the former commune of Chastel-sur-Murat was merged into Murat. Murat is the administrative seat of this new commune.

Histo ...

, ennobled under

Louis XVIII of France.

His father, a graduate of the

École Nationale des Chartes, served as a regional librarian and was a keen

naturalist

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

with a strong interest in natural science. He collected rocks, insects and plants and encouraged nature studies in the family. Pierre Teilhard's

spirituality

The meaning of ''spirituality'' has developed and expanded over time, and various meanings can be found alongside each other. Traditionally, spirituality referred to a religious process of re-formation which "aims to recover the original shape o ...

was awakened by his mother. When he was twelve, he went to the

Jesuit college of Mongré in

Villefranche-sur-Saône, where he completed the

Baccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

in

philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

and

mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

. In 1899, he entered the Jesuit novitiate in

Aix-en-Provence

Aix-en-Provence, or simply Aix, is a List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, city and Communes of France, commune in southern France, about north of Marseille. A former capital of Provence, it is the Subprefectures in France, s ...

.

In October 1900, he began his junior studies at the Collégiale Saint-Michel de Laval. On 25 March 1901, he made his first vows. In 1902, Teilhard completed a licentiate in literature at the

University of Caen.

In 1901 and 1902, due to an anti-clerical movement in the French Republic, the government banned the Jesuits and other religious orders from France. This forced the Jesuits to go into exile on the island of

Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

in the United Kingdom. While there, his brother and sister in France died of illnesses and another sister was incapacitated by illness. The unexpected losses of his siblings at young ages caused Teilhard to plan to discontinue his Jesuit studies in science, and change to studying theology. He wrote that he changed his mind after his Jesuit novice master encouraged him to follow science as a legitimate way to God. Due to his strength in science subjects, he was despatched to teach physics and chemistry at the

Collège de la Sainte Famille in

Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

,

Khedivate of Egypt

The Khedivate of Egypt ( or , ; ') was an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire, established and ruled by the Muhammad Ali Dynasty following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brought an end to the short- ...

from 1905 until 1908. From there he wrote in a letter: "

is the dazzling of the East foreseen and drunk greedily ... in its lights, its vegetation, its fauna and its deserts."

For the next four years he was a

Scholastic at ''

Ore Place'' in

Hastings, East Sussex

Hastings ( ) is a seaside town and borough in East Sussex on the south coast of England,

east of Lewes and south east of London. The town gives its name to the Battle of Hastings, which took place to the north-west at Senlac Hill in 1066. ...

where he acquired his theological formation.

There he synthesized his scientific, philosophical and theological knowledge in the light of

evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

. At that time he read ''

Creative Evolution'' by

Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; ; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of analytic philosophy and continental philosophy, especially during the first half of the 20th century until the S ...

, about which he wrote that "the only effect that brilliant book had upon me was to provide fuel at just the right moment, and very briefly, for a fire that was already consuming my heart and mind." Bergson was a French philosopher who was influential in the traditions of

analytic philosophy

Analytic philosophy is a broad movement within Western philosophy, especially English-speaking world, anglophone philosophy, focused on analysis as a philosophical method; clarity of prose; rigor in arguments; and making use of formal logic, mat ...

and

continental philosophy

Continental philosophy is a group of philosophies prominent in 20th-century continental Europe that derive from a broadly Kantianism, Kantian tradition.Continental philosophers usually identify such conditions with the transcendental subject or ...

. His ideas were influential on Teilhard's views on matter, life, and energy. On 24 August 1911, aged 30, Teilhard was

ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

a priest.

In the ensuing years, Bergson’s protege, the mathematician and philosopher

Édouard Le Roy

Édouard Louis Emmanuel Julien Le Roy (; 18 June 1870 in Paris – 10 November 1954 in Paris) was a French philosopher and mathematician.

Life

Le Roy entered the ''École Normale Supérieure'' in 1892, and received the '' agrégation'' in mathema ...

, was appointed successor to Bergson at the College de France. In 1921, Le Roy and Teilhard became friends and met weekly for long discussions. Teilhard wrote: "I loved him like a father, and owed him a very great debt . . . he gave me confidence, enlarged my mind, and served as a spokesman for my ideas, then taking shape, on “hominization” and the “noosphere.” Le Roy later wrote in one of his books: "I have so often and for so long talked over with Pierre Teilhard the views expressed here that neither of us can any longer pick out his own contribution.”

Academic and scientific career

Geology

His father's strong interest in natural science and geology instilled the same in Teilhard from an early age, and would continue throughout his lifetime. As a child, Teilhard was intensely interested in the stones and rocks on his family's land and the neighboring regions. His father helped him develop his skills of observation. At the University of Paris, he studied geology, botany and zoology. After the French government banned all religious orders from France and the Jesuits were exiled to the island of Jersey in the UK, Teilhard deepened his geology knowledge by studying the rocks and landscape of the island.

In 1920, he became a lecturer in geology at the Catholic University of Paris, and later a professor. He earned his doctorate in 1922. In 1923 he was hired to do geological research on expeditions in China by the Jesuit scientist and priest

Emile Licent. In 1914, Licent with the sponsorship of the Jesuits founded one of the first museums in China and the first museum of natural science: the

Musée Hoangho Paiho. In its first eight years, the museum was housed in the

Chongde Hall of the Jesuits. In 1922, with the support of the Catholic Church and the French Concession, Licent built a special building for the museum on the land adjacent to the

Tsin Ku University, which was founded by the Jesuits in China.

With help from Teilhard and others, Licent collected over 200,000 paleontology, animal, plant, ancient human, and rock specimens for the museum, which still make up more than half of its 380,000 specimens. Many of the publications and writings of the museum and its related institute were included in the world's database of

zoological

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

,

botanical

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, and palaeontological literature, which is still an important basis for examining the early scientific records of the various disciplines of biology in northern China.

Teilhard and Licent were the first to discover and examine the

Shuidonggou (水洞沟) (

Ordos Upland,

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

) archaeological site in northern China. Recent analysis of flaked stone artifacts from the most recent (1980) excavation at this site has identified an assemblage which constitutes the southernmost occurrence of an Initial Upper Paleolithic blade technology proposed to have originated in the Altai region of Southern Siberia. The lowest levels of the site are now dated from 40,000 to 25,000 years ago.

Teilhard spent the periods between 1926-1935 and 1939-1945 studying and researching the geology and palaeontology of the region. Among other accomplishments, he improved understanding of China’s sedimentary deposits and established approximate ages for various layers. He also produced a geological map of China. It was during the period 1926-1935 that he joined the excavation that discovered Peking Man.

Paleontology

From 1912 to 1914, Teilhard began his

palaeontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geo ...

education by working in the laboratory of the

French National Museum of Natural History, studying the

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s of the middle

Tertiary. Later he studied elsewhere in Europe. This included spending 5 days over the course of a 3-month period in the middle of 1913 as a volunteer assistant helping to dig with

Arthur Smith Woodward and

Charles Dawson at the

Piltdown site. Teilhard’s brief time assisting with digging there occurred many months after the discovery of the first fragments of the fraudulent "

Piltdown Man".

Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

judged that Pierre Teilhard de Chardin conspired with Dawson in the Piltdown forgery. Most Teilhard experts (including all three Teilhard biographers) and many scientists (including the scientists who uncovered the hoax and investigated it) have rejected the suggestion that he participated, and say that he did not.

Anthropologist

H. James Birx wrote that Teilhard "had questioned the validity of this fossil evidence from the very beginning, one positive result was that the young geologist and seminarian now became particularly interested in palaeoanthropology as the science of fossil hominids.“

, an

palaeontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

and

anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

, who as early as 1915 had recognized the non-

hominid origins of the Piltdown finds, gradually guided Teilhard towards human paleontology. Boule was the editor of the journal ''L’Anthropologie'' and the founder of two other scientific journals. He was also a professor at the Parisian

Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle for 34 years, and for many years director of the museum's Institute of Human Paleontology.

It was there that Teilhard became a friend of

Henri Breuil

Henri Édouard Prosper Breuil (28 February 1877 – 14 August 1961), often referred to as Abbé Breuil (), was a French Catholic Church, Catholic priest, archaeologist, anthropologist, ethnologist and geologist. He studied cave art in the Somme ( ...

, a

Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

,

archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

,

anthropologist

An anthropologist is a scientist engaged in the practice of anthropology. Anthropologists study aspects of humans within past and present societies. Social anthropology, cultural anthropology and philosophical anthropology study the norms, values ...

,

ethnologist and

geologist

A geologist is a scientist who studies the structure, composition, and History of Earth, history of Earth. Geologists incorporate techniques from physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics, and geography to perform research in the Field research, ...

. In 1913, Teilhard and Breuil did excavations at the prehistoric painted

Cave of El Castillo in Spain. The cave contains the oldest known cave painting in the world. The site is divided into about 19 archeological layers in a sequence beginning in the

Proto-Aurignacian and ending in the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

.

Later after his return to China in 1926, Teilhard was hired by the Cenozoic Laboratory at the Peking Union Medical College. Starting in 1928, he joined other geologists and palaeontologists to excavate the sedimentary layers in the Western Hills near Zhoukoudian. At this site, the scientists discovered the so-called Peking man (Sinanthropus pekinensis), a fossil hominid dating back at least 350,000 years, which is part of the Homo erectus phase of human evolution. Teilhard became world-known as a result of his accessible explanations of the Sinanthropus discovery. He also himself made major contributions to the geology of this site. Teilhard's long stay in China gave him more time to think and write about evolution, as well as continue his scientific research.

After the

Peking Man discoveries, Breuil joined Teilhard at the site in 1931 and confirmed the presence of stone tools.

Scientific writings

During his career, Teilhard published many dozens of scientific papers in scholarly scientific journals. When they were published in collections as books, they took up 11 volumes.

, the co-founder and co-director of the

Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, said: "I think you have to distinguish between the hundreds of papers that Teilhard wrote in a purely scientific vein, about which there is no controversy. In fact, the papers made him one of the top two or three geologists of the Asian continent. So this man knew what science was. What he's doing in ''The Phenomenon'' and most of the popular essays that have made him controversial is working pretty much alone to try to synthesize what he's learned about through scientific discovery - more than with scientific method - what scientific discoveries tell us about the nature of ultimate reality.” Grim said those writing were controversial to some scientists because Teilhard combined theology and metaphysics with science, and controversial to some religious leaders for the same reason.

Service in World War I

Mobilized in December 1914, Teilhard served in

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

as a stretcher-bearer in the

8th Moroccan Rifles. Priests were mobilized in the France of the First World War era, and not as military chaplains but as either stretcher-bearers or actual fighting soldiers. For his valor, he received several citations, including the

Médaille militaire and the

Legion of Honor.

During the war, he developed his reflections in his diaries and in letters to his cousin, Marguerite Teillard-Chambon, who later published a collection of them. (See section below)

He later wrote: "...the war was a meeting ... with the Absolute." In 1916, he wrote his first essay: ''La Vie Cosmique'' (''Cosmic life''), where his scientific and philosophical thought was revealed just as his mystical life. While on leave from the military he pronounced his solemn vows as a Jesuit in

Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon on 26 May 1918. In August 1919, in

Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

, he wrote ''Puissance spirituelle de la Matière'' (''The Spiritual Power of Matter'').

At the

University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793–1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, Teilhard pursued three unit degrees of natural science:

geology

Geology (). is a branch of natural science concerned with the Earth and other astronomical objects, the rocks of which they are composed, and the processes by which they change over time. Modern geology significantly overlaps all other Earth ...

,

botany

Botany, also called plant science, is the branch of natural science and biology studying plants, especially Plant anatomy, their anatomy, Plant taxonomy, taxonomy, and Plant ecology, ecology. A botanist or plant scientist is a scientist who s ...

, and

zoology

Zoology ( , ) is the scientific study of animals. Its studies include the anatomy, structure, embryology, Biological classification, classification, Ethology, habits, and distribution of all animals, both living and extinction, extinct, and ...

. His thesis treated the mammals of the French lower

Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

and their

stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

. After 1920, he lectured in geology at the

Catholic Institute of Paris and after earning a science doctorate in 1922 became an assistant professor there.

Research in China

In 1923 he traveled to China with Father

Émile Licent, who was in charge of a significant laboratory collaboration between the National Museum of Natural History and

Marcellin Boule's laboratory in

Tianjin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in North China, northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the National Central City, nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the ...

. Licent carried out considerable basic work in connection with Catholic missionaries who accumulated observations of a scientific nature in their spare time.

Teilhard wrote several essays, including ''La Messe sur le Monde'' (the ''Mass on the World''), in the

Ordos Desert

The Ordos Desert () is a desert/ steppe region in Northwest China, administered under the prefecture of Ordos City in the Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region (centered ca. ). It extends over an area of approximately , and comprises two sub-de ...

. In the following year, he continued lecturing at the Catholic Institute and participated in a cycle of conferences for the students of the Engineers' Schools. Two theological essays on

original sin

Original sin () in Christian theology refers to the condition of sinfulness that all humans share, which is inherited from Adam and Eve due to the Fall of man, Fall, involving the loss of original righteousness and the distortion of the Image ...

were sent to a theologian at his request on a purely personal basis:

* ''Chute, Rédemption et Géocentrie'' (''Fall, Redemption and Geocentry'') (July 1920)

* ''Notes sur quelques représentations historiques possibles du Péché originel'' (''Note on Some Possible Historical Representations of Original Sin'') (Works, Tome X, Spring 1922)

The Church required him to give up his lecturing at the Catholic Institute in order to continue his geological research in China. Teilhard traveled again to China in April 1926. He would remain there for about twenty years, with many voyages throughout the world. He settled until 1932 in Tianjin with Émile Licent, then in

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

. Teilhard made five geological research expeditions in China between 1926 and 1935. They enabled him to establish a general geological map of China.

In 1926–27, after a missed campaign in

Gansu

Gansu is a provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeastern part of the province. The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibetan Plateau, Ti ...

, Teilhard traveled in the

Sanggan River Valley near Kalgan (

Zhangjiakou) and made a tour in Eastern

Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

. He wrote ''Le Milieu Divin'' (''

The Divine Milieu''). Teilhard prepared the first pages of his main work ''Le Phénomène Humain'' (''

The Phenomenon of Man''). The Holy See refused the Imprimatur for ''Le Milieu Divin'' in 1927.

He joined the ongoing excavations of the

Peking Man Site at

Zhoukoudian as an advisor in 1926 and continued in the role for the

Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the

China Geological Survey following its founding in 1928. Teilhard resided in

Manchuria

Manchuria is a historical region in northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day northeast China and parts of the modern-day Russian Far East south of the Uda (Khabarovsk Krai), Uda River and the Tukuringra-Dzhagdy Ranges. The exact ...

with Émile Licent, staying in western

Shanxi

Shanxi; Chinese postal romanization, formerly romanised as Shansi is a Provinces of China, province in North China. Its capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-level cities are Changzhi a ...

and northern

Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

with the Chinese paleontologist

Yang Zhongjian and with

Davidson Black

Davidson Black, (July 25, 1884 – March 15, 1934) was a Canadian paleoanthropologist, best known for his naming of ''Sinanthropus pekinensis'' (now '' Homo erectus pekinensis''). He was Chairman of the Geological Survey of China and a Fel ...

, Chairman of the China Geological Survey.

After a tour in Manchuria in the area of

Greater Khingan with Chinese geologists, Teilhard joined the team of American Expedition Center-Asia in the

Gobi Desert, organized in June and July by the

American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

with

Roy Chapman Andrews

Roy Chapman Andrews (January 26, 1884 – March 11, 1960) was an American explorer, adventurer, and Natural history, naturalist who became the director of the American Museum of Natural History. He led a series of expeditions through the politi ...

. Henri Breuil and Teilhard discovered that the

Peking Man, the nearest relative of ''

Anthropopithecus'' from

Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

, was a ''faber'' (worker of stones and controller of fire). Teilhard wrote ''L'Esprit de la Terre'' (''The Spirit of the Earth'').

Teilhard took part as a scientist in the

Croisière Jaune (Yellow Cruise) financed by

André Citroën in

Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

. Northwest of Beijing in Kalgan, he joined the Chinese group who joined the second part of the team, the

Pamir group, in

Aksu City. He remained with his colleagues for several months in

Ürümqi

Ürümqi, , is the capital of the Xinjiang, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region in Northwestern China. With a census population of 4 million in 2020, Ürümqi is the second-largest city in China's northwestern interior after Xi'an, also the ...

, capital of

Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

. In 1933, Rome ordered him to give up his post in Paris. Teilhard subsequently undertook several explorations in the south of China. He traveled in the valleys of the

Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ) is the longest river in Eurasia and the third-longest in the world. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows including Dam Qu River the longest source of the Yangtze, i ...

and

Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

in 1934, then, the following year, in

Guangxi

Guangxi,; officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam (Hà Giang Province, Hà Giang, Cao Bằn ...

and

Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

.

During all these years, Teilhard contributed considerably to the constitution of an international network of research in human paleontology related to the whole of eastern and southeastern Asia. He would be particularly associated in this task with two friends,

Davidson Black

Davidson Black, (July 25, 1884 – March 15, 1934) was a Canadian paleoanthropologist, best known for his naming of ''Sinanthropus pekinensis'' (now '' Homo erectus pekinensis''). He was Chairman of the Geological Survey of China and a Fel ...

and the

Scot George Brown Barbour. Often he would visit France or the United States, only to leave these countries for further expeditions.

World travels

From 1927 to 1928, Teilhard was based in Paris. He journeyed to

Leuven

Leuven (, , ), also called Louvain (, , ), is the capital and largest City status in Belgium, city of the Provinces of Belgium, province of Flemish Brabant in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is located about east of Brussels. The municipalit ...

, Belgium, and to

Cantal

Cantal (; or ) is a rural Departments of France, department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes Regions of France, region of France, with its Prefectures in France, prefecture in Aurillac. Its other principal towns are Saint-Flour, Cantal, Saint-Flou ...

and

Ariège, France. Between several articles in reviews, he met new people such as

Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher.

In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, m ...

and , who were to help him in issues with the Catholic Church.

Answering an invitation from

Henry de Monfreid, Teilhard undertook a journey of two months in

Obock, in

Harar

Harar (; Harari language, Harari: ሀረር / ; ; ; ), known historically by the indigenous as Harar-Gey or simply Gey (Harari: ጌይ, ݘٛىيْ, ''Gēy'', ), is a List of cities with defensive walls, walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is al ...

in the

Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire, historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia, was a sovereign state that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak a ...

, and in

Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

with his colleague Pierre Lamarre, a geologist, before embarking in

Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

to return to Tianjin. While in China, Teilhard developed a deep and personal friendship with

Lucile Swan.

During 1930–1931, Teilhard stayed in France and in the United States. During a conference in Paris, Teilhard stated: "For the observers of the Future, the greatest event will be the sudden appearance of a collective humane

conscience

A conscience is a Cognition, cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual's ethics, moral philosophy or value system. Conscience is not an elicited emotion or thought produced by associations based on i ...

and a human work to make." From 1932 to 1933, he began to meet people to clarify issues with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith regarding ''Le Milieu divin'' and ''L'Esprit de la Terre''. He met

Helmut de Terra, a

German geologist in the

International Geology Congress in

Washington, D.C.

Teilhard participated in the 1935

Yale–

Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

expedition in northern and central India with the geologist

Helmut de Terra and Patterson, who verified their assumptions on Indian

Paleolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

civilisations in

Kashmir

Kashmir ( or ) is the Northwestern Indian subcontinent, northernmost geographical region of the Indian subcontinent. Until the mid-19th century, the term ''Kashmir'' denoted only the Kashmir Valley between the Great Himalayas and the Pir P ...

and the

Salt Range Valley. He then made a short stay in

Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

, on the invitation of

Dutch paleontologist

Gustav Heinrich Ralph von Koenigswald to the site of

Java Man. A second

cranium, more complete, was discovered. Professor von Koenigswald had also found a tooth in a Chinese

apothecary

''Apothecary'' () is an Early Modern English, archaic English term for a medicine, medical professional who formulates and dispenses ''materia medica'' (medicine) to physicians, surgeons and patients. The modern terms ''pharmacist'' and, in Brit ...

shop in 1934 that he believed belonged to a three-meter-tall

ape, ''

Gigantopithecus

''Gigantopithecus'' ( ) is an extinct genus of ape that lived in southern China from 2 million to approximately 300,000–200,000 years ago during the Early Pleistocene, Early to Middle Pleistocene, represented by one species, ''Gigantopithecus ...

,'' which lived between one hundred thousand and around a million years ago. Fossilized teeth and bone (''

dragon bones

''Long gu'' are remains of ancient life (such as fossils) prescribed for a variety of ailments in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chinese medicine and Chinese herbalism, herbalism. They were historically believed, and are traditionally considere ...

'') are often ground into powder and used in some branches of

traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medicine, alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. A large share of its claims are pseudoscientific, with the majority of treatments having no robust evidence ...

.

In 1937, Teilhard wrote ''Le Phénomène spirituel'' (''The Phenomenon of the Spirit'') on board the boat Empress of Japan, where he met

Sylvia Brett,

Ranee of

Sarawak

Sarawak ( , ) is a States and federal territories of Malaysia, state of Malaysia. It is the largest among the 13 states, with an area almost equal to that of Peninsular Malaysia. Sarawak is located in East Malaysia in northwest Borneo, and is ...

The ship took him to the United States. He received the

Mendel Medal granted by

Villanova University

Villanova University is a Private university, private Catholic Church, Catholic research university in Villanova, Pennsylvania, United States. It was founded by the Order of Saint Augustine in 1842 and named after Thomas of Villanova, Saint Thom ...

during the Congress of

Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, in recognition of his works on human paleontology. He made a speech about

evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

, the origins and the destiny of man. ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' dated 19 March 1937 presented Teilhard as the Jesuit who held that

man

A man is an adult male human. Before adulthood, a male child or adolescent is referred to as a boy.

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the f ...

descended from

monkeys

Monkey is a common name that may refer to most mammals of the infraorder Simiiformes, also known as simians. Traditionally, all animals in the group now known as simians are counted as monkeys except the apes. Thus monkeys, in that sense, co ...

. Some days later, he was to be granted the ''

Doctor Honoris Causa'' distinction from

Boston College

Boston College (BC) is a private university, private Catholic Jesuits, Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1863 by the Society of Jesus, a Catholic Religious order (Catholic), religious order, t ...

.

Rome banned his work ''L'Énergie Humaine'' in 1939. By this point Teilhard was based again in France, where he was immobilized by

malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

. During his return voyage to Beijing he wrote ''L'Energie spirituelle de la Souffrance'' (''Spiritual Energy of Suffering'') (Complete Works, tome VII).

In 1941, Teilhard submitted to Rome his most important work, ''Le Phénomène Humain''. By 1947, Rome forbade him to write or teach on philosophical subjects. The next year, Teilhard was called to Rome by the Superior General of the Jesuits who hoped to acquire permission from the Holy See for the publication of ''Le Phénomène Humain''. However, the prohibition to publish it that was previously issued in 1944 was again renewed. Teilhard was also forbidden to take a teaching post in the Collège de France. Another setback came in 1949, when permission to publish ''Le Groupe Zoologique'' was refused.

Teilhard was nominated to the

French Academy of Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

in 1950. He was forbidden by his superiors to attend the International Congress of Paleontology in 1955. The Supreme Authority of the Holy Office, in a decree dated 15 November 1957, forbade the works of de Chardin to be retained in libraries, including those of

religious institute

In the Catholic Church, a religious institute is "a society in which members, according to proper law, pronounce public religious vows, vows, either perpetual or temporary which are to be renewed, however, when the period of time has elapsed, a ...

s. His books were not to be sold in Catholic bookshops and were not to be translated into other languages.

Further resistance to Teilhard's work arose elsewhere. In April 1958, all Jesuit publications in Spain ("Razón y Fe", "Sal Terrae","Estudios de Deusto", etc.) carried a notice from the Spanish Provincial of the Jesuits that Teilhard's works had been published in Spanish without previous ecclesiastical examination and in defiance of the decrees of the Holy See. A decree of the Holy Office dated 30 June 1962, under the authority of

Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII (born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death on 3 June 1963. He is the most recent pope to take ...

, warned:

The

Diocese of Rome on 30 September 1963 required Catholic booksellers in Rome to withdraw his works as well as those that supported his views.

Death

Teilhard died in New York City, where he was in residence at the Jesuit

Church of St. Ignatius Loyola,

Park Avenue

Park Avenue is a boulevard in New York City that carries north and southbound traffic in the borough (New York City), boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. For most of the road's length in Manhattan, it runs parallel to Madison Avenue to the wes ...

. On 15 March 1955, at the house of his diplomat cousin Jean de Lagarde, Teilhard told friends he hoped he would die on

Easter Sunday

Easter, also called Pascha (Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek language, Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, de ...

.

On the evening of Easter Sunday, 10 April 1955, during an animated discussion at the apartment of Rhoda de Terra, his personal assistant since 1949, Teilhard suffered a heart attack and died.

[ He was buried in the cemetery for the New York Province of the Jesuits at the Jesuit novitiate, St. Andrew-on-Hudson, in Hyde Park, New York. With the moving of the novitiate, the property was sold to the Culinary Institute of America in 1970.

]

Teachings

Teilhard de Chardin wrote two comprehensive works, '' The Phenomenon of Man'' and ''The Divine Milieu''.

His posthumously published book, ''The Phenomenon of Man'', set forth a sweeping account of the unfolding of the cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

and the evolution of matter to humanity, to ultimately a reunion with Christ. In the book, Teilhard abandoned literal interpretations of creation in the Book of Genesis

The Book of Genesis (from Greek language, Greek ; ; ) is the first book of the Hebrew Bible and the Christian Old Testament. Its Hebrew name is the same as its incipit, first word, (In the beginning (phrase), 'In the beginning'). Genesis purpor ...

in favor of allegorical and theological interpretations. The unfolding of the material cosmos

The cosmos (, ; ) is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos is studied in cosmologya broad discipline covering ...

is described from primordial particles to the development of life, human beings and the noosphere, and finally to his vision of the Omega Point in the future, which is "pulling" all creation towards it. He was a leading proponent of orthogenesis

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is an Superseded theories in science, obsolete biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolution, evolve ...

, the idea that evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

occurs in a directional, goal-driven way. Teilhard argued in Darwinian terms with respect to biology, and supported the synthetic model of evolution, but argued in Lamarckian terms for the development of culture, primarily through the vehicle of education.

Teilhard made a total commitment to the evolutionary process in the 1920s as the core of his spirituality, at a time when other religious thinkers felt evolutionary thinking challenged the structure of conventional Christian faith. He committed himself to what he thought the evidence showed.

Teilhard made sense of the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

by assuming it had a vitalist

Vitalism is a belief that starts from the premise that "living organisms are fundamentally different from non-living entities because they contain some non-physical element or are governed by different principles than are inanimate things." Wher ...

evolutionary process.paleontology

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure ge ...

and Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

allowed him to develop a highly progressive, cosmic theology which took into account his evolutionary studies. Teilhard recognized the importance of bringing the Church into the modern world, and approached evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

as a way of providing ontological meaning for Christianity, particularly creation theology. For Teilhard, evolution was "the natural landscape where the history of salvation is situated."teleological

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Applet ...

process towards union with the Godhead, effected through the incarnation and redemption of Christ, 'in whom all things hold together' (Colossians 1:17)."Pleroma

Pleroma (, literally "fullness") generally refers to the totality of divine powers. It is used in Christian theological contexts, as well as in Gnosticism. The term also appears in the Epistle to the Colossians, which is traditionally attributed ...

, when God will be 'all in all' (1 Corinthians 15:28)."faith

Faith is confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept. In the context of religion, faith is " belief in God or in the doctrines or teachings of religion".

According to the Merriam-Webster's Dictionary, faith has multiple definitions, inc ...

with his academic interests as a paleontologist

Paleontology, also spelled as palaeontology or palæontology, is the scientific study of the life of the past, mainly but not exclusively through the study of fossils. Paleontologists use fossils as a means to classify organisms, measure geolo ...

.[Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, ''The Phenomenon of Man'' (New York: Harper and Row, 1959), 250–75.] One particularly poignant observation in Teilhard's book entails the notion that evolution

Evolution is the change in the heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. It occurs when evolutionary processes such as natural selection and genetic drift act on genetic variation, re ...

is becoming an increasingly optional process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

.marginalization

Social exclusion or social marginalisation is the social disadvantage and relegation to the fringe of society. It is a term that has been used widely in Europe and was first used in France in the late 20th century. In the EU context, the Euro ...

as huge inhibitors of evolution, especially since evolution requires a unification of consciousness

Consciousness, at its simplest, is awareness of a state or object, either internal to oneself or in one's external environment. However, its nature has led to millennia of analyses, explanations, and debate among philosophers, scientists, an ...

. He states that "no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else."God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

.

Teilhard also used his perceived correlation between spiritual and material to describe Christ, arguing that Christ not only has a mystical

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight ...

dimension but also takes on a physical dimension as he becomes the organizing principle of the universe—that is, the one who "holds together" the universe. For Teilhard, Christ formed not only the eschatological end toward which his mystical/ecclesial body is oriented, but he also "operates physically in order to regulate all things" becoming "the one from whom all creation receives its stability." In other words, as the one who holds all things together, "Christ exercises a supremacy over the universe which is physical, not simply juridical. He is the unifying center of the universe and its goal. The function of holding all things together indicates that Christ is not only man and God; he also possesses a third aspect—indeed, a third nature—which is cosmic."

In this way, the Pauline description of the Body of Christ

In Christian theology, the term Body of Christ () has two main but separate meanings: it may refer to Jesus Christ's words over the bread at the celebration of the Jewish feast of Passover that "This is my body" in (see Last Supper), or it ...

was not simply a mystical or ecclesial concept for Teilhard; it is cosmic. This cosmic Body of Christ "extend throughout the universe and compris sall things that attain their fulfillment in Christ o that... the Body of Christ is the one single thing that is being made in creation." Teilhard describes this cosmic amassing of Christ as "Christogenesis". According to Teilhard, the universe is engaged in Christogenesis as it evolves toward its full realization at Omega

Omega (, ; uppercase Ω, lowercase ω; Ancient Greek ὦ, later ὦ μέγα, Modern Greek ωμέγα) is the twenty-fourth and last letter in the Greek alphabet. In the Greek numerals, Greek numeric system/isopsephy (gematria), it has a value ...

, a point which coincides with the fully realized Christ.

Eugenics and racism

Teilhard has been criticized for incorporating elements of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

, social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

, and eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

into his optimistic thinking about unlimited human progress.racial

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of va ...

inequality was rooted in biological difference: "Do the yellows— he Chinese��have the same human value as the whites? r.Licent and many missionaries say that their present inferiority is due to their long history of Paganism. I'm afraid that this is only a 'declaration of pastors.' Instead, the cause seems to be the natural racial foundation…"[ In a letter from 1936 explaining his Omega Point conception, he rejected both the ]Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

quest for particularistic hegemony and the Christian/Communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

insistence on egalitarianism

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all hum ...

: "As not all ethnic groups have the same value, they must be dominated, which does not mean they must be despised—quite the reverse … In other words, ''at one and the same time'' there should be official recognition of: (1) the primacy/priority of the earth over nations; (2) the inequality of peoples and races. Now the ''second'' point is currently reviled by Communism … and the Church, and the ''first'' point is similarly reviled by the Fascist systems (and, of course, by less gifted peoples!)".[ In the essay 'Human Energy' (1937), he asked, "What fundamental attitude … should the advancing wing of humanity take to fixed or definitely unprogressive ethnical groups? The earth is a closed and limited surface. To what extent should it tolerate, racially or nationally, areas of lesser activity? More generally still, how should we judge the efforts we lavish in all kinds of hospitals on saving what is so often no more than one of life's rejects? … To what extent should not the development of the strong … take precedence over the preservation of the weak?"][ The theologian John P. Slattery interprets this last remark to suggest " genocidal practices for the sake of eugenics".][

Even after ]World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

Teilhard continued to argue for racial and individual eugenics in the name of human progress, and denounced the United Nations declaration of the Equality of Races (1950) as "scientifically useless" and "practically dangerous" in a letter to the agency's director Jaime Torres Bodet. In 1953, he expressed his frustration at the Church's failure to embrace the scientific possibilities for optimising human nature

Human nature comprises the fundamental dispositions and characteristics—including ways of Thought, thinking, feeling, and agency (philosophy), acting—that humans are said to have nature (philosophy), naturally. The term is often used to denote ...

, including by the separation of sexuality from reproduction (a notion later developed e.g. by the second-wave feminist Shulamith Firestone in her 1970 book '' The Dialectic of Sex''), and postulated "the absolute right … to try everything right to the end—even in the matter of human biology".[

The theologian John F. Haught has defended Teilhard from Slattery's charge of "persistent attraction to racism, fascism, and genocidal ideas" by pointing out that Teilhard's philosophy was not based on racial exclusion but rather on union through differentiation, and that Teilhard took seriously the human responsibility for continuing to remake the world. With regard to union through differentiation, he underlined the importance of understanding properly a quotation used by Slattery in which Teilhard writes, "I hate ]nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

and its apparent regressions to the past. But I am very interested in the primacy it returns to the collective. Could a passion for 'the race' represent a first draft of the Spirit of the Earth?" Writing from China in October 1936, shortly after the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, Teilhard expressed his stance towards the new political movement in Europe, "I am alarmed at the attraction that various kinds of Fascism exert on intelligent (?) people who can see in them nothing but the hope of returning to the Neolithic". He felt that the choice between what he called "the American, the Italian, or the Russian type" of political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

(i.e. liberal capitalism, Fascist corporatism

Corporatism is an ideology and political system of interest representation and policymaking whereby Corporate group (sociology), corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, come toget ...

, Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

Communism) had only "technical" relevance to his search for overarching unity and a philosophy of action.

Relationship with the Catholic Church

In 1925, Teilhard was ordered by the Superior General of the Society of Jesus, Włodzimierz Ledóchowski, to leave his teaching position in France and to sign a statement withdrawing his controversial statements regarding the doctrine of original sin. Rather than quit the Society of Jesus, Teilhard obeyed and departed for China.

This was the first of a series of condemnations by a range of ecclesiastical officials that would continue until after Teilhard's death. In August 1939, he was told by his Jesuit superior in Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

, "Father, as an evolutionist and a Communist, you are undesirable here, and will have to return to France as soon as possible". The climax of these condemnations was a 1962 '' monitum'' (warning) of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith cautioning on Teilhard's works. It said:

The Holy Office

The Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith (DDF) is a department of the Roman Curia in charge of the religious discipline of the Catholic Church. The Dicastery is the oldest among the departments of the Roman Curia. Its seat is the Palace o ...

did not, however, place any of Teilhard's writings on the ''Index Librorum Prohibitorum

The (English: ''Index of Forbidden Books'') was a changing list of publications deemed heretical or contrary to morality by the Sacred Congregation of the Index (a former dicastery of the Roman Curia); Catholics were forbidden to print or re ...

'' (Index of Forbidden Books), which still existed during Teilhard's lifetime and at the time of the 1962 decree.

Shortly thereafter, prominent clerics mounted a strong theological defense of Teilhard's works. Henri de Lubac

Henri-Marie Joseph Sonier de Lubac (; 20 February 1896 – 4 September 1991), better known as Henri de Lubac, was a French Jesuit priest and Cardinal (Catholicism), cardinal who is considered one of the most influential Theology, theologia ...

(later a Cardinal) wrote three comprehensive books on the theology of Teilhard de Chardin in the 1960s. While de Lubac mentioned that Teilhard was less than precise in some of his concepts, he affirmed the orthodoxy of Teilhard de Chardin and responded to Teilhard's critics: "We need not concern ourselves with a number of detractors of Teilhard, in whom emotion has blunted intelligence". Later that decade Joseph Ratzinger, a German theologian who became Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

, spoke glowingly of Teilhard's Christology in Ratzinger's ''Introduction to Christianity'':

On 20 July 1981, the Holy See stated that, after consultation of cardinals Casaroli and Šeper, the letter did not change the position of the warning issued by the Holy Office on 30 June 1962, which pointed out that Teilhard's work contained ambiguities and grave doctrinal errors.

Cardinal Ratzinger in his book '' The Spirit of the Liturgy'' incorporates Teilhard's vision as a touchstone of the Catholic Mass:

Cardinal Avery Dulles said in 2004:

Cardinal Christoph Schönborn wrote in 2007:

In July 2009, Vatican spokesman Federico Lombardi said, "By now, no one would dream of saying that eilhardis a heterodox author who shouldn't be studied."

Pope Francis

Pope Francis (born Jorge Mario Bergoglio; 17 December 1936 – 21 April 2025) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 13 March 2013 until Death and funeral of Pope Francis, his death in 2025. He was the fi ...

refers to Teilhard's eschatological contribution in his encyclical ''Laudato si'

''Laudato si'' (''Praise Be to You'') is the second encyclical of Pope Francis, subtitled "on care for our common home". In it, the Pope criticizes consumerism and irresponsible economic development, laments environmental degradation and gl ...

''.

Evaluations by scientists

Julian Huxley

Julian Huxley, the evolutionary biologist, in the preface to the 1955 edition of ''The Phenomenon of Man'', praised the thought of Teilhard de Chardin for looking at the way in which human development needs to be examined within a larger integrated universal sense of evolution, though admitting he could not follow Teilhard all the way. In the publication Encounter, Huxley wrote: "The force and purity of Teilhard's thought and expression ... has given the world a picture not only of rare clarity but pregnant with compelling conclusions."

Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Dobzhansky

Theodosius Grigorievich Dobzhansky (; ; January 25, 1900 – December 18, 1975) was a Russian-born American geneticist and evolutionary biologist. He was a central figure in the field of evolutionary biology for his work in shaping the modern ...

, writing in 1973, drew upon Teilhard's insistence that evolutionary theory provides the core of how man understands his relationship to nature, calling him "one of the great thinkers of our age".[ Reprinted in J. Peter Zetterberg (ed.), ''Evolution versus Creationism'' (1983), ORYX Press.] Dobzhansky was renowned as the president of four prestigious scientific associations: the Genetics Society of America, the American Society of Naturalists, the Society for the Study of Evolution and the American Society of Zoologists. He also called Teilhard "one of the greatest intellects of our time."

Daniel Dennett

Daniel Dennett

Daniel Clement Dennett III (March 28, 1942 – April 19, 2024) was an American philosopher and cognitive scientist. His research centered on the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of biology, particularly as those ...

claimed "it has become clear to the point of unanimity among scientists that Teilhard offered nothing serious in the way of an alternative to orthodoxy; the ideas that were peculiarly his were confused, and the rest was just bombastic redescription of orthodoxy."

David Sloan Wilson

In 2019, evolutionary biologist David Sloan Wilson praised Teilhard's book ''The Phenomenon of Man'' as "scientifically prophetic in many ways", and considers his own work as an updated version of it, commenting that " dern evolutionary theory shows that what Teilhard meant by the Omega Point is achievable in the foreseeable future."

Robert Francoeur

Robert Francoeur (1931-2012), the American biologist, said the Phenomenon of Man "will be one of the few books that will be remembered after the dust of the century has settled on many of its companions."

Stephen Jay Gould

In an essay published in the magazine ''Natural History

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

'' (and later compiled as the 16th essay in his book '' Hen's Teeth and Horse's Toes''), American biologist Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

made a case for Teilhard's guilt in the Piltdown Hoax, arguing that Teilhard has made several compromising slips of the tongue in his correspondence with paleontologist Kenneth Oakley, in addition to what Gould termed to be his "suspicious silence" about Piltdown despite having been, at that moment in time, an important milestone in his career.New Scientist

''New Scientist'' is a popular science magazine covering all aspects of science and technology. Based in London, it publishes weekly English-language editions in the United Kingdom, the United States and Australia. An editorially separate organ ...

saying: "There is no proved factual evidence known to me that supports the premise that Father Teilhard de Chardin gave Charles Dawson a piece of fossil elephant molar tooth as a souvenir of his time spent in North Africa. This faulty thread runs throughout the reconstruction ... After spending a year thinking about this accusation, I have at last become convinced that it is erroneous." Oakley also pointed out that after Teilhard got his degree in paleontology and gained experience in the field, he published scientific articles that show he found the scientific claims of the two Piltdown leaders to be incongruous, and that Teilhard did not agree they had discovered an ape-man that was a missing link between apes and humans.

In a comprehensive rebuttal of Gould in America magazine, Mary Lukas said his claims about Teilhard were "patently ridiculous” and “wilder flights of fancy” that were easily disprovable and weak. For example, she notes Teilhard was only briefly and minimally involved in the Piltdown project for four reasons: 1) He was only a student in his early days of studying paleontology. 2) His college was in France and he was at the Piltdown site in Britain for a total of just 5 days over a short period of three months out of the 7-year project. 3) He was simply a volunteer assistant, helping with basic digging. 4) This limited involvement ended prior to the most important claimed discovery, due to his being conscripted to serve in the French army. She added: "Further, according to his letters, both published and unpublished, to friends, Teilhard's relationship to Dawson was anything but close."

Lukas said Gould made the claims for selfish reasons: “The charge gained Mr. Gould two weeks of useful publicity and prepared reviewers to give a friendly reception to the collection of essays” that he was about to publish. She said Teilhard was “beyond doubt the most famous of” all the people who were involved in the excavations” and “the one who could gather headlines most easily…. The shock value of the suggestion that the philosopher-hero was also a criminal was stunning.” Two years later, Lukas published a more detailed article in the British scholarly journal Antiquity in which she further refuted Gould, including an extensive timeline of events.

Peter Medawar

In 1961, British immunologist and Nobel laureate Peter Medawar wrote a scornful review of ''The Phenomenon of Man'' for the journal ''Mind

The mind is that which thinks, feels, perceives, imagines, remembers, and wills. It covers the totality of mental phenomena, including both conscious processes, through which an individual is aware of external and internal circumstances ...