Pictavia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now

The Picts were a group of peoples in what is now

Dál Riata was subject to the Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa (reigned 729–761), and although it had its own kings beginning in the 760s, does not appear to have recovered its political independence from the Picts. A later Pictish king, Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820), placed his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riata (811–835). Pictish attempts to achieve a similar dominance over the Britons of

Dál Riata was subject to the Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa (reigned 729–761), and although it had its own kings beginning in the 760s, does not appear to have recovered its political independence from the Picts. A later Pictish king, Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820), placed his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riata (811–835). Pictish attempts to achieve a similar dominance over the Britons of

The archaeological record gives insight into the Picts'

The archaeological record gives insight into the Picts'  The early Picts are associated with piracy and raiding along the coasts of

The early Picts are associated with piracy and raiding along the coasts of

Pictish art is primarily associated with monumental stones, but also includes smaller objects of stone and bone, and metalwork such as

Pictish art is primarily associated with monumental stones, but also includes smaller objects of stone and bone, and metalwork such as

File:Pictish Stones in the Museum of ScotlandDSCF6254.jpg, Pictish cross from the Monifieth Sculptured Stones, Museum of Scotland

File:Rodney02.JPG,

ePrints

server, including Katherine Forsyth's *

''Language in Pictland''

(PDF) and *

''Literacy in Pictland''

(PDF) *

The language of the Picts

, article by Paul Kavanagh, 2012-02-04

a

University College Cork

Bede's ''Ecclesiastical History'' and its Continuation (pdf)

a

CCEL

translated by A. M. Sellar.

at th

*

Proceedings

' of the

Tarbat Discovery Programme

with reports on excavations at Portmahomack

SPNS

the

Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

north of the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is a firth in Scotland, an inlet of the North Sea that separates Fife to its north and Lothian to its south. Further inland, it becomes the estuary of the River Forth and several other rivers.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate ...

, in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

. Where they lived and details of their culture can be gleaned from early medieval texts and Pictish stones

A Pictish stone is a type of monumental stele, generally carved or incised with symbols or designs. A few have ogham inscriptions. Located in Scotland, mostly north of the River Clyde, Clyde-River Forth, Forth line and on the Eastern side of the ...

. The name appears in written records as an exonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

from the late third century AD. They are assumed to have been descendants of the Caledonii

The Caledonians (; or '; , ''Kalēdōnes'') or the Caledonian Confederacy were a Brittonic-speaking (Celtic) tribal confederacy in what is now Scotland during the Iron Age and Roman eras.

The Greek form of the tribal name gave rise to the ...

and other northern Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

tribes. Their territory is referred to as "Pictland" by modern historians. Initially made up of several chiefdom

A chiefdom is a political organization of people representation (politics), represented or government, governed by a tribal chief, chief. Chiefdoms have been discussed, depending on their scope, as a stateless society, stateless, state (polity) ...

s, it came to be dominated by the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

from the seventh century. During this Verturian hegemony, ''Picti'' was adopted as an endonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

. This lasted around 160 years until the Pictish kingdom merged with that of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

to form the Kingdom of Alba

The Kingdom of Alba (; ) was the Kingdom of Scotland between the deaths of Donald II in 900 and of Alexander III in 1286. The latter's death led indirectly to an invasion of Scotland by Edward I of England in 1296 and the First War of Scotti ...

, ruled by the House of Alpin

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpinid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from Constantine II (Causantín mac Áeda) ...

. The concept of "Pictish kingship" continued for a few decades until it was abandoned during the reign of Caustantín mac Áeda.

Pictish society was typical of many early medieval societies in northern Europe and had parallels with neighbouring groups. Archaeology gives some impression of their culture. Medieval sources report the existence of a Pictish language

Pictish is an extinct Brittonic Celtic language spoken by the Picts, the people of eastern and northern Scotland from late antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. Virtually no direct attestations of Pictish remain, short of a limited number of geo ...

, and evidence shows that it was an Insular Celtic language

Insular Celtic languages are the group of Celtic languages spoken in Brittany, Great Britain, Ireland, and the Isle of Man. All surviving Celtic languages are in the Insular group, including Breton, which is spoken on continental Europe in Br ...

related to the Brittonic spoken by the Celtic Britons

The Britons ( *''Pritanī'', , ), also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons, were the Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age until the High Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, ...

to the south. Pictish was gradually displaced by Middle Gaelic

Middle Irish, also called Middle Gaelic (, , ), is the Goidelic language which was spoken in Ireland, most of Scotland and the Isle of Man from AD; it is therefore a contemporary of Late Old English and Early Middle English. The modern Goidelic ...

as part of the wider Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaels, Gaelic or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of Celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread fro ...

from the late ninth century. Much of their history is known from outside sources, including Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

, hagiographies

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian ...

of saints such as that of Columba

Columba () or Colmcille (7 December 521 – 9 June 597 AD) was an Irish abbot and missionary evangelist credited with spreading Christianity in what is today Scotland at the start of the Hiberno-Scottish mission. He founded the important abbey ...

by Adomnán

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (; , ''Adomnanus''; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and Christian saint, saint. He was the author of the ''Life ...

, and the Irish annals

A number of Irish annals, of which the earliest was the Chronicle of Ireland, were compiled up to and shortly after the end of the 17th century. Annals were originally a means by which monks determined the yearly chronology of feast days. Over ti ...

.

Definitions

There has been substantial critical reappraisal of the concept of "Pictishness" over recent decades. The popular view at the beginning of the twentieth century was that they were exotic "lost people". It was noted in the highly influential work of 1955, ''The Problem of the Picts'', that the subject area was difficult, with the archaeological and historical records frequently being at odds with the conventionalessentialist

Essentialism is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to their identity. In early Western thought, Platonic idealism held that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In '' Categories'', Aristotle s ...

expectations about historical peoples. Since then, the culture-historical paradigm of archaeology dominant since the late nineteenth century gave way to the processual archaeology

Processual archaeology (formerly, the New Archaeology) is a form of archaeological theory. It had its beginnings in 1958 with the work of Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips, ''Method and Theory in American Archaeology,'' in which the pair stated ...

(formerly known as the ''New Archaeology'') theory. Moreover, there has been significant reappraisal of textual sources written, for example by Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

and Adomnán

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (; , ''Adomnanus''; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and Christian saint, saint. He was the author of the ''Life ...

in the seventh and eighth centuries. These works relate events of previous centuries, but current scholarship recognises their often allegorical, pseudo-historical nature, and their true value often lies in an appraisal of the time period in which they were written.

The difficulties with Pictish history and archaeology arise from the fact that the people who were called Picts were a fundamentally heterogeneous group with little cultural uniformity. Care is needed to avoid viewing them through the lens of what the cultural historian Gilbert Márkus calls the "Ethnic Fallacy". The people known as "Picts" by outsiders in late antiquity were very different from those who later adopted the name, in terms of language, culture, religion and politics.

The term "Pict" is found in Roman sources from the end of the third century AD, when it was used to describe unromanised people in northern Britain. The term is most likely to have been pejorative, emphasising their supposed barbarism in contrast to the Britons under Roman rule. It has been argued, most notably by James Fraser, that the term "Pict" would have had little meaning to the people to whom it was being applied. Fraser posits that it was adopted as an endonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

only in the late seventh century, as an inclusive term for people under rule of the Verturian hegemony, centered in Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

(the area around modern-day Inverness

Inverness (; ; from the , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness") is a city in the Scottish Highlands, having been granted city status in 2000. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highland ...

and Moray

Moray ( ; or ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland. Its council is based in Elgin, the area' ...

), particularly following the Battle of Dun Nechtain

The Battle of Dun Nechtain or Battle of Nechtansmere (; ) was fought between the Picts, led by King Bridei Mac Bili, and the Northumbrians, led by King Ecgfrith, on 20 May 685.

The Northumbrian hegemony over northern Britain, won by Ecgfrith ...

. This view is, however, not universal. Gordon Noble and Nicholas Evans consider it plausible, if not provable, that "Picts" may have been used as an endonym by those northern Britons in closest contact with Rome as early as the fourth century.

The bulk of written history

Recorded history or written history describes the historical events that have been recorded in a written form or other documented communication which are subsequently evaluated by historians using the historical method. For broader world his ...

dates from the seventh century onwards. The Irish annalists and contemporary scholars, like Bede, use "Picts" to describe the peoples under the Verturian hegemony. This encompassed most of Scotland north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus and to the exclusion of territory occupied by Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

in the west. To the south lay the Brittonic kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (, "valley of the River Clyde, Clyde"), also known as Cumbria, was a Celtic Britons, Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Scotland in the Middle Ages, Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland an ...

, with Lothian occupied by Northumbrian Angles. The use of "Picts" as a descriptive term continued to the formation of the Alpínid dynasty

The House of Alpin, also known as the Alpinid dynasty, Clann Chináeda, and Clann Chinaeda meic Ailpín, was the kin-group which ruled in Pictland, possibly Dál Riata, and then the kingdom of Alba from Constantine II (Causantín mac Áeda) i ...

in the ninth century, and the merging of the Pictish Kingdom with that of Dál Riata.

Etymology

TheLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

word first occurs in a panegyric

A panegyric ( or ) is a formal public speech or written verse, delivered in high praise of a person or thing. The original panegyrics were speeches delivered at public events in ancient Athens.

Etymology

The word originated as a compound of - ' ...

, a formal eulogising speech from 297 and is most commonly explained as meaning 'painted' (from Latin 'to paint'; , 'painted', cf. Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, 'picture'). This is generally understood to be a reference to the practice of tattooing. Claudian

Claudius Claudianus, known in English as Claudian (Greek: Κλαυδιανός; ), was a Latin poet associated with the court of the Roman emperor Honorius at Mediolanum (Milan), and particularly with the general Stilicho. His work, written almo ...

, in his account of the Roman commander Stilicho

Stilicho (; – 22 August 408) was a military commander in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was partly of Vandal origins and married to Serena, the niece of emperor Theodosius I. He b ...

, written around 404, speaks of designs on the bodies of dying Picts, presumably referring to tattoos or body paint. Isidore of Seville

Isidore of Seville (; 4 April 636) was a Spania, Hispano-Roman scholar, theologian and Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Seville, archbishop of Seville. He is widely regarded, in the words of the 19th-century historian Charles Forbes René de Montal ...

reports in the early seventh century that the practice was continued by the Picts. An alternative suggestion is that the Latin ''Picti'' was derived from a native form, perhaps related etymologically to the Gallic Pictones

The Pictones were a Gallic tribe dwelling south of the Loire river, in the modern departments of Vendée, Deux-Sèvres and Vienne, during the Iron Age and Roman period.

Name

They are mentioned as ''Pictonibus'' and ''Pictones'' by Julius Caes ...

.

The Picts were called ''Cruithni'' in Old Irish

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic (, Ogham, Ogham script: ᚌᚑᚔᚇᚓᚂᚉ; ; ; or ), is the oldest form of the Goidelic languages, Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from 600 to 900. The ...

and ''Prydyn'' in Old Welsh

Old Welsh () is the stage of the Welsh language from about 800 AD until the early 12th century when it developed into Middle Welsh.Koch, p. 1757. The preceding period, from the time Welsh became distinct from Common Brittonic around 550, ha ...

. These are lexical cognates

In historical linguistics, cognates or lexical cognates are sets of words that have been inherited in direct descent from an etymological ancestor in a common parent language.

Because language change can have radical effects on both the sound ...

, from the proto-Celtic *''kwritu'' 'form', from which *''Pretania'' (Britain) also derives. ''Pretani'' (and with it ''Cruithni'' and ''Prydyn'') is likely to have originated as a generalised term for any native inhabitant of Britain. This is similar to the situation with the Gaelic name of Scotland, ''Alba

''Alba'' ( , ) is the Scottish Gaelic name for Scotland. It is also, in English-language historiography, used to refer to the polity of Picts and Scots united in the ninth century as the Kingdom of Alba, until it developed into the Kingd ...

'', which originally seems to have been a generalised term for Britain. It has been proposed that the Picts may have called themselves ''Albidosi'', a name found in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba

The ''Chronicle of the Kings of Alba'', or ''Scottish Chronicle'', is a short written chronicle covering the period from the time of Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpín) (d. 858) until the reign of Kenneth II (Cináed mac Maíl Coluim) (r. 971� ...

during the reign of Máel Coluim mac Domnaill.

Origins

The origin myth presented inBede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

's ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' (), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the growth of Christianity. It was composed in Latin, and ...

'' describes the Picts as settlers from Scythia

Scythia (, ) or Scythica (, ) was a geographic region defined in the ancient Graeco-Roman world that encompassed the Pontic steppe. It was inhabited by Scythians, an ancient Eastern Iranian equestrian nomadic people.

Etymology

The names ...

who arrived on the northern coast of Ireland by chance. Local Scoti

''Scoti'' or ''Scotti'' is a Latin name for the Gaels,Duffy, Seán. ''Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia''. Routledge, 2005. p.698 first attested in the late 3rd century. It originally referred to all Gaels, first those in Ireland and then those ...

leaders redirected them to northern Britain where they settled, taking Scoti wives. The ''Pictish Chronicle

The Pictish Chronicle is a name used to refer to a pseudo-historical account of the kings of the Picts beginning many thousand years before history was recorded in Pictavia and ending after Pictavia had been enveloped by Scotland.

Version A

The ...

'', repeating this story, further names the mythical founding leader ''Cruithne'' (the Gaelic word for ''Pict''), followed by his sons, whose names correspond with the seven provinces of Pictland: ''Circin

Circin was a Pictish territory recorded in contemporary sources between the 6th and 9th centuries, located north of the Firth of Tay and south of the Grampian mountains within modern-day Scotland. It is associated with the nominative plural for ...

'', ''Fidach'', ''Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

'', '' Fotla'' (''Atholl''), ''Cat

The cat (''Felis catus''), also referred to as the domestic cat or house cat, is a small domesticated carnivorous mammal. It is the only domesticated species of the family Felidae. Advances in archaeology and genetics have shown that the ...

'', '' Ce'' and '' Fib''. Bede's account has long been recognised as pseudohistorical literary invention, and is thought to be of Pictish origin, composed around 700. Its structure is similar to the origin myths of other peoples and its main purpose appears to have been to legitimise the annexation of Pictish territories by Fortriu and the creation of a wider Pictland.

A study published in 2023 sequenced the whole genomes from eight individuals associated with the Pictish period, excavated from cemeteries at Lundin Links

Lundin Links is a small village in the parish of Largo on the south coast of Fife in eastern central Scotland.

The village was largely built in the 19th century to accommodate tourists visiting the village of Lower Largo. Lundin Links is conti ...

in Fife and Balintore, Easter Ross

__NOTOC__

Balintore (from the meaning "The Bleaching Town") is a village near Tain in Easter Ross, Scotland. It is one of three villages on this northern stretch of the Moray Firth

The Moray Firth (; , or ) is a roughly triangular inlet (o ...

. The study observed "broad affinities" between the mainland Pictish genomes, Iron Age Britons and the present-day people living in western Scotland, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

, Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ; ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, part of the United Kingdom in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It has been #Descriptions, variously described as a country, province or region. Northern Ireland shares Repub ...

and Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

, but less with the rest of England, supporting the current archaeological theories of a "local origin" of the Pictish people.

History

The area occupied by the Picts had previously been described by Roman writers and geographers as the home of the ''Caledonii

The Caledonians (; or '; , ''Kalēdōnes'') or the Caledonian Confederacy were a Brittonic-speaking (Celtic) tribal confederacy in what is now Scotland during the Iron Age and Roman eras.

The Greek form of the tribal name gave rise to the ...

''. These Romans also used other names to refer to Britannic tribes living in the area, including ''Verturiones

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and Ea ...

'', ''Taexali

The Taexali () or Taezali () were people on the eastern coast of Britannia Barbara in ancient Scotland, known only from a single mention of them by the geographer Ptolemy c. 150. From his general description and the approximate location of their ...

'' and ''Venicones

The Venicones were a people of ancient Britain, known only from a single mention of them by the geographer Ptolemy c. 150 AD. He recorded that their town was 'Orrea'. This has been identified as the Roman fort of Horrea Classis, located by Rivet a ...

''.

Written history relating to the Picts as a people emerges in the Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages (historiography), Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start o ...

. At that time, the Gael

The Gaels ( ; ; ; ) are an Insular Celtic ethnolinguistic group native to Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man. They are associated with the Gaelic languages: a branch of the Celtic languages comprising Irish, Manx, and Scottish Gaelic ...

s of Dál Riata

Dál Riata or Dál Riada (also Dalriada) () was a Gaels, Gaelic Monarchy, kingdom that encompassed the Inner Hebrides, western seaboard of Scotland and north-eastern Ireland, on each side of the North Channel (Great Britain and Ireland), North ...

controlled what is now Argyll

Argyll (; archaically Argyle; , ), sometimes called Argyllshire, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county of western Scotland. The county ceased to be used for local government purposes in 1975 and most of the area ...

, as part of a kingdom straddling the sea between Britain and Ireland. The Angles

Angles most commonly refers to:

*Angles (tribe), a Germanic-speaking people that took their name from the Angeln cultural region in Germany

*Angle, a geometric figure formed by two rays meeting at a common point

Angles may also refer to:

Places ...

of Bernicia

Bernicia () was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was approximately equivalent to the modern English cou ...

, which merged with Deira

Deira ( ; Old Welsh/ or ; or ) was an area of Post-Roman Britain, and a later Anglian kingdom.

Etymology

The name of the kingdom is of Brythonic origin, and is derived from the Proto-Celtic , meaning 'oak' ( in modern Welsh), in which case ...

to form Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

, overwhelmed the adjacent British kingdoms, and for much of the 7th century Northumbria was the most powerful kingdom in Britain. The Picts were probably tributary to Northumbria until the reign of Bridei mac Beli, when, in 685, the Anglians suffered a defeat at the Battle of Dun Nechtain

The Battle of Dun Nechtain or Battle of Nechtansmere (; ) was fought between the Picts, led by King Bridei Mac Bili, and the Northumbrians, led by King Ecgfrith, on 20 May 685.

The Northumbrian hegemony over northern Britain, won by Ecgfrith ...

that halted their northward expansion. The Northumbrians continued to dominate southern Scotland for the remainder of the Pictish period.

Dál Riata was subject to the Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa (reigned 729–761), and although it had its own kings beginning in the 760s, does not appear to have recovered its political independence from the Picts. A later Pictish king, Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820), placed his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riata (811–835). Pictish attempts to achieve a similar dominance over the Britons of

Dál Riata was subject to the Pictish king Óengus mac Fergusa (reigned 729–761), and although it had its own kings beginning in the 760s, does not appear to have recovered its political independence from the Picts. A later Pictish king, Caustantín mac Fergusa (793–820), placed his son Domnall on the throne of Dál Riata (811–835). Pictish attempts to achieve a similar dominance over the Britons of Alt Clut

Dumbarton Castle (, ; ) has the longest recorded history of any stronghold in Scotland. It sits on a volcanic plug of basalt known as Dumbarton Rock which is high and overlooks the Scottish town of Dumbarton.

History

Dumbarton Rock was forme ...

(Strathclyde

Strathclyde ( in Welsh language, Welsh; in Scottish Gaelic, Gaelic, meaning 'strath

) were not successful.

The alley

An alley or alleyway is a narrow lane, footpath, path, or passageway, often reserved for pedestrians, which usually runs between, behind, or within buildings in towns and cities. It is also a rear access or service road (back lane), or a path, w ...

of the River Clyde') was one of nine former Local government in Scotland, local government Regions and districts of Scotland, regions of Scotland cre ...Viking Age

The Viking Age (about ) was the period during the Middle Ages when Norsemen known as Vikings undertook large-scale raiding, colonising, conquest, and trading throughout Europe and reached North America. The Viking Age applies not only to their ...

brought significant change to Britain and Ireland, no less in Scotland than elsewhere, with the Vikings conquering and settling the islands and various mainland areas, including Caithness

Caithness (; ; ) is a Shires of Scotland, historic county, registration county and Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area of Scotland.

There are two towns, being Wick, Caithness, Wick, which was the county town, and Thurso. The count ...

, Sutherland

Sutherland () is a Counties of Scotland, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area in the Scottish Highlands, Highlands of Scotland. The name dates from the Scandinavian Scotland, Viking era when t ...

and Galloway

Galloway ( ; ; ) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the counties of Scotland, historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council areas of Scotland, council area of Dumfries and Gallow ...

. In the middle of the 9th century Ketil Flatnose

Ketill Björnsson, nicknamed Flatnose (Old Norse: ''Flatnefr''), was a Norse King of the Isles of the 9th century.

Primary sources

The story of Ketill and his daughter Auðr, or Aud the Deep-Minded, was probably first recorded by the Icelande ...

is said to have founded the Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles, also known as Sodor, was a Norse–Gaelic kingdom comprising the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries. The islands were known in Old Norse as the , or "Southern I ...

, governing many of these territories, and by the end of that century the Vikings had destroyed the Kingdom of Northumbria, greatly weakened the Kingdom of Strathclyde

Strathclyde (, "valley of the River Clyde, Clyde"), also known as Cumbria, was a Celtic Britons, Brittonic kingdom in northern Britain during the Scotland in the Middle Ages, Middle Ages. It comprised parts of what is now southern Scotland an ...

, and founded the Kingdom of York

Scandinavian York or Viking York () is a term used by historians for what is now Yorkshire during the period of Scandinavian domination from late 9th century until it was annexed and integrated into England after the Norman Conquest; in parti ...

. In a major battle in 839, the Vikings killed the King of Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

, Eógan mac Óengusa, the King of Dál Riata Áed mac Boanta

Áed mac Boanta (died 839) is believed to have been a king of Dál Riata.

The only reference to Áed in the Irish annals is found in the Annals of Ulster, where it is recorded that " Eóganán mac Óengusa, Bran mac Óengusa, Áed mac Boanta, a ...

, and many others. In the aftermath, in the 840s, Kenneth MacAlpin

Kenneth MacAlpin (; ; 810 – 13 February 858) or Kenneth I was King of Dál Riada (841–850), and King of the Picts (848–858), of likely Gaelic origin. According to the traditional account, he inherited the throne of Dál Riada from his fa ...

() became king of the Picts.

During the reign of Cínaed's grandson, Caustantín mac Áeda (900–943), outsiders began to refer to the region as the Kingdom of Alba rather than the Kingdom of the Picts, but it is not known whether this was because a new kingdom was established or Alba was simply a closer approximation of the Pictish name for the Picts. However, though the Pictish language did not disappear suddenly, a process of Gaelicisation

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaels, Gaelic or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of Celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread fro ...

(which may have begun generations earlier) was clearly underway during the reigns of Caustantín and his successors.

By a certain point, probably during the 11th century, all the inhabitants of northern Alba had become fully Gaelicised Scots, and Pictish identity was forgotten. Henry of Huntingdon

Henry of Huntingdon (; 1088 – 1157), the son of a canon in the diocese of Lincoln, was a 12th-century English historian and the author of ''Historia Anglorum'' (Medieval Latin for "History of the English"), as "the most important Anglo- ...

was one of the first (surviving) historians to note this disappearance in the mid-12th century ''Historia Anglorum''. Later, the idea of Picts as a tribe was revived in myth

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

and legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of a narrative featuring human actions, believed or perceived to have taken place in human history. Narratives in this genre may demonstrate human values, and possess certain qualities that give the ...

.

Kings and kingdoms

The early history of Pictland is unclear. In later periods, multiple kings ruled over separate kingdoms, with one king, sometimes two, more or less dominating their lesser neighbours. ''De Situ Albanie

''De Situ Albanie'' (or ''dSA'' for short) is the name given to the first of seven Scottish documents found in the so-called Poppleton Manuscript, now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. It was probably written sometime between 1202 ...

'', a 13th century document, the Pictish Chronicle

The Pictish Chronicle is a name used to refer to a pseudo-historical account of the kings of the Picts beginning many thousand years before history was recorded in Pictavia and ending after Pictavia had been enveloped by Scotland.

Version A

The ...

, the 11th century ''Duan Albanach

The Duan Albanach (Song of the Scots) is a Middle Gaelic poem. Written during the reign of Mael Coluim III, who ruled between 1058 and 1093, it is found in a variety of Irish sources, and the usual version comes from the ''Book of Lecan'' and ' ...

'', along with Irish legends, have been used to argue the existence of seven Pictish kingdoms. These are: Cait, or Cat, situated in modern Caithness

Caithness (; ; ) is a Shires of Scotland, historic county, registration county and Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area of Scotland.

There are two towns, being Wick, Caithness, Wick, which was the county town, and Thurso. The count ...

and Sutherland

Sutherland () is a Counties of Scotland, historic county, registration county and lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area in the Scottish Highlands, Highlands of Scotland. The name dates from the Scandinavian Scotland, Viking era when t ...

; Ce, situated in modern Mar

Mar, mar or MAR may refer to:

Culture

* Mar (title), or Mor, an honorific in Syriac

* Earl of Mar, an earldom in Scotland

* Mar., an abbreviation for March, the third month of the year in the Gregorian calendar

* Biblical abbreviation for the ...

and Buchan

Buchan is a coastal district in the north-east of Scotland, bounded by the Ythan and Deveron rivers. It was one of the original provinces of the Kingdom of Alba. It is now one of the six committee areas of Aberdeenshire.

Etymology

The ge ...

; Circin

Circin was a Pictish territory recorded in contemporary sources between the 6th and 9th centuries, located north of the Firth of Tay and south of the Grampian mountains within modern-day Scotland. It is associated with the nominative plural for ...

, perhaps situated in modern Angus

Angus may refer to:

*Angus, Scotland, a council area of Scotland, and formerly a province, sheriffdom, county and district of Scotland

* Angus, Canada, a community in Essa, Ontario

Animals

* Angus cattle, various breeds of beef cattle

Media

* ...

and the Mearns

Kincardineshire or the County of Kincardine, also known as the Mearns (from the Scottish Gaelic meaning "the stewartry"), is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area on the coast of north-east Scotland. It is bounded by Abe ...

; Fib, the modern Fife

Fife ( , ; ; ) is a council areas of Scotland, council area and lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area in Scotland. A peninsula, it is bordered by the Firth of Tay to the north, the North Sea to the east, the Firth of Forth to the s ...

; Fidach, location unknown, but possibly near Inverness

Inverness (; ; from the , meaning "Mouth of the River Ness") is a city in the Scottish Highlands, having been granted city status in 2000. It is the administrative centre for The Highland Council and is regarded as the capital of the Highland ...

; Fotla, modern Atholl

Atholl or Athole () is a district in the heart of the Scottish Highlands, bordering (in clockwise order, from north-east) Marr, Gowrie, Perth, Strathearn, Breadalbane, Lochaber, and Badenoch. Historically it was a Pictish kingdom, becoming ...

(''Ath-Fotla''); and Fortriu

Fortriu (; ; ; ) was a Pictish kingdom recorded between the 4th and 10th centuries. It was traditionally believed to be located in and around Strathearn in central Scotland, but is more likely to have been based in the north, in the Moray and ...

, cognate with the ''Verturiones'' of the Romans, recently shown to be centred on Moray

Moray ( ; or ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland. Its council is based in Elgin, the area' ...

.

More small kingdoms may have existed. Some evidence suggests that a Pictish kingdom also existed in Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

. ''De Situ Albanie'' is not the most reliable of sources, and the number of kingdoms, one for each of the seven sons of ''Cruithne'', the eponym

An eponym is a noun after which or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word ''eponym'' include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovati ...

ous founder of the Picts, may well be grounds enough for disbelief. Regardless of the exact number of kingdoms and their names, the Pictish nation was not a united one.

For most of Pictish recorded history, the kingdom of Fortriu appears dominant, so much so that ''king of Fortriu'' and ''king of the Picts'' may mean one and the same thing in the annals. This was previously thought to lie in the area around Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

and southern Strathearn

Strathearn or Strath Earn (), also the Earn Valley, is the strath of the River Earn, which flows from Loch Earn to meet the River Tay in the east of Scotland.

The area covers the stretch of the river, containing a number of settlements in ...

; however, recent work has convinced those working in the field that Moray (a name referring to a very much larger area in the High Middle Ages than the county of Moray

Moray ( ; or ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland. It lies in the north-east of the country, with a coastline on the Moray Firth, and borders the council areas of Aberdeenshire and Highland. Its council is based in Elgin, the area' ...

) was the core of Fortriu.

The Picts are often thought to have practised matrilineal

Matrilineality, at times called matriliny, is the tracing of kinship through the female line. It may also correlate with a social system in which people identify with their matriline, their mother's lineage, and which can involve the inheritan ...

kingship succession on the basis of Irish legends and a statement in Bede

Bede (; ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, Bede of Jarrow, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the most known writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most f ...

's history. The kings of the Picts when Bede was writing were Bridei and Nechtan, sons of Der Ilei, who indeed claimed the throne through their mother Der Ilei, daughter of an earlier Pictish king.

In Ireland, kings were expected to come from among those who had a great-grandfather who had been king. Kingly fathers were not frequently succeeded by their sons, not because the Picts practised matrilineal succession, but because they were usually followed by their own brothers or cousins (agnatic seniority

Agnatic seniority is a patrilineality, patrilineal principle of inheritance where the order of succession to the throne prefers the monarch's younger brother over the monarch's own sons. A monarch's children (the next generation) succeed only ...

), more likely to be experienced men with the authority and the support necessary to be king. This was similar to tanistry

Tanistry is a Gaelic system for passing on titles and lands. In this system the Tanist (; ; ) is the office of heir-apparent, or second-in-command, among the (royal) Gaelic patrilineal dynasties of Ireland, Scotland and Mann, to succeed to ...

.

The only woman ruler, mentioned in early Scottish history

The recorded history of Scotland begins with the Scotland during the Roman Empire, arrival of the Roman Empire in the 1st century, when the Roman province, province of Roman Britain, Britannia reached as far north as the Antonine Wall. No ...

, is the Pictish Queen in 617, who summoned pirates to massacre Donnán and his companions on the island of Eigg

Eigg ( ; ) is one of the Small Isles in the Scotland, Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the island of Isle of Skye, Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is long from north to south, and east to west. With ...

.

The nature of kingship changed considerably during the centuries of Pictish history. While earlier kings had to be successful war leaders to maintain their authority, kingship became rather less personalised and more institutionalised during this time. Bureaucratic kingship was still far in the future when Pictland became Alba, but the support of the church, and the apparent ability of a small number of families to control the kingship for much of the period from the later 7th century onwards, provided a considerable degree of continuity. In much the same period, the Picts' neighbours in Dál Riata and Northumbria faced considerable difficulties, as the stability of succession and rule that previously benefited them ended.

The later Mormaer

In early medieval Scotland, a mormaer was the Gaelic name for a regional or provincial ruler, theoretically second only to the King of Scots, and the senior of a '' Toísech'' (chieftain). Mormaers were equivalent to English earls or Continenta ...

s are thought to have originated in Pictish times, and to have been copied from, or inspired by, Northumbrian usages. It is unclear whether the Mormaers were originally former kings, royal officials, or local nobles, or some combination of these. Likewise, the Pictish shires and thanage

A thanage was an area of land held by a thegn in Anglo-Saxon England.

Thanage can also denote the rank held by such a thegn

In later Anglo-Saxon England, a thegn or thane (Latin minister) was an aristocrat who ranked at the third level in lay ...

s, traces of which are found in later times, are thought to have been adopted from their southern neighbours.

Society

The archaeological record gives insight into the Picts'

The archaeological record gives insight into the Picts' material culture

Material culture is culture manifested by the Artifact (archaeology), physical objects and architecture of a society. The term is primarily used in archaeology and anthropology, but is also of interest to sociology, geography and history. The fie ...

, and suggest a society not readily distinguishable from its

British, Gaelic, or Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

neighbours. Although analogy and knowledge of other Celtic societies may be a useful guide, these extend across a very large area. Relying on knowledge of pre-Roman Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

, or 13th-century Ireland, as a guide to the Picts of the 6th century may be misleading if the analogy is pursued too far.

Like most northern European people in Late Antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

, the Picts were farmers living in small communities. Cattle and horses were an obvious sign of wealth and prestige. Sheep and pigs were kept in large numbers, and place names suggest that transhumance

Transhumance is a type of pastoralism or Nomad, nomadism, a seasonal movement of livestock between fixed summer and winter pastures. In montane regions (''vertical transhumance''), it implies movement between higher pastures in summer and low ...

was common. Animals were small by later standards, although horses from Britain were imported into Ireland as breeding stock to enlarge native horses. From Irish sources, it appears that the elite engaged in competitive cattle breeding for size, and this may have been the case in Pictland also. Carvings show hunting with dogs, and also, unlike in Ireland, with falcons. Cereal crops included wheat

Wheat is a group of wild and crop domestication, domesticated Poaceae, grasses of the genus ''Triticum'' (). They are Agriculture, cultivated for their cereal grains, which are staple foods around the world. Well-known Taxonomy of wheat, whe ...

, barley

Barley (), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains; it was domesticated in the Fertile Crescent around 9000 BC, giving it nonshattering spikele ...

, oat

The oat (''Avena sativa''), sometimes called the common oat, is a species of cereal grain grown for its seed, which is known by the same name (usually in the plural). Oats appear to have been domesticated as a secondary crop, as their seeds ...

s and rye

Rye (''Secale cereale'') is a grass grown extensively as a grain, a cover crop and a forage crop. It is grown principally in an area from Eastern and Northern Europe into Russia. It is much more tolerant of cold weather and poor soil than o ...

. Vegetables included kale

Kale (), also called leaf cabbage, belongs to a group of cabbage (''Brassica oleracea'') cultivars primarily grown for their Leaf vegetable, edible leaves; it has also been used as an ornamental plant. Its multiple different cultivars vary quite ...

, cabbage

Cabbage, comprising several cultivars of '' Brassica oleracea'', is a leafy green, red (purple), or white (pale green) biennial plant grown as an annual vegetable crop for its dense-leaved heads. It is descended from the wild cabbage ( ''B.& ...

, onion

An onion (''Allium cepa'' , from Latin ), also known as the bulb onion or common onion, is a vegetable that is the most widely cultivated species of the genus '' Allium''. The shallot is a botanical variety of the onion which was classifie ...

s and leek

A leek is a vegetable, a cultivar of ''Allium ampeloprasum'', the broadleaf wild leek (synonym (taxonomy), syn. ''Allium porrum''). The edible part of the plant is a bundle of Leaf sheath, leaf sheaths that is sometimes erroneously called a "s ...

s, pea

Pea (''pisum'' in Latin) is a pulse or fodder crop, but the word often refers to the seed or sometimes the pod of this flowering plant species. Peas are eaten as a vegetable. Carl Linnaeus gave the species the scientific name ''Pisum sativum' ...

s and beans

A bean is the seed of some plants in the legume family (Fabaceae) used as a vegetable for human consumption or animal feed. The seeds are often preserved through drying (a ''pulse''), but fresh beans are also sold. Dried beans are tradition ...

and turnip

The turnip or white turnip ('' Brassica rapa'' subsp. ''rapa'') is a root vegetable commonly grown in temperate climates worldwide for its white, fleshy taproot. Small, tender varieties are grown for human consumption, while larger varieties a ...

s, and some types no longer common, such as skirret. Plants such as wild garlic Plant species in the genus ''Allium

''Allium'' is a large genus of monocotyledonous flowering plants with around 1000 accepted species, making ''Allium'' the largest genus in the family Amaryllidaceae and among the largest plant genera in the wo ...

, nettle

Nettle refers to plants with stinging hairs, particularly those of the genus '' Urtica''. It can also refer to plants which resemble ''Urtica'' species in appearance but do not have stinging hairs. Plants called "nettle" include:

* ball nettle ...

s and watercress

Watercress or yellowcress (''Nasturtium officinale'') is a species of aquatic flowering plant in the cabbage family, Brassicaceae.

Watercress is a rapidly growing perennial plant native to Eurasia. It is one of the oldest known leaf vegetabl ...

may have been gathered in the wild. The pastoral economy meant that hides and leather were readily available. Wool

Wool is the textile fiber obtained from sheep and other mammals, especially goats, rabbits, and camelids. The term may also refer to inorganic materials, such as mineral wool and glass wool, that have some properties similar to animal w ...

was the main source of fibres for clothing, and flax

Flax, also known as common flax or linseed, is a flowering plant, ''Linum usitatissimum'', in the family Linaceae. It is cultivated as a food and fiber crop in regions of the world with temperate climates. In 2022, France produced 75% of t ...

was also common, although it is not clear if they grew it for fibres, for oil, or as a foodstuff. Fish, shellfish, seals, and whales were exploited along coasts and rivers. The importance of domesticated animals suggests that meat and milk products were a major part of the diet of ordinary people, while the elite would have eaten a diet rich in meat from farming and hunting.

No Pictish counterparts to the areas of denser settlement around important fortresses in Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

and southern Britain, or any other significant urban settlements, are known. Larger, but not large, settlements existed around royal forts, such as at Burghead Fort

Burghead Fort was a Pictish promontory fort on the site now occupied by the small town of Burghead in Moray, Scotland. It was one of the earliest power centres of the Picts and was three times the size of any other enclosed site in Early Medieval ...

, or associated with religious foundations. No towns are known in Scotland until the 12th century.

The technology of everyday life is not well recorded, but archaeological evidence shows it to have been similar to that in Ireland and Anglo-Saxon England. Recently evidence has been found of watermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as mill (grinding), milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in ...

s in Pictland. Kilns

A kiln is a thermally insulated chamber, a type of oven, that produces temperatures sufficient to complete some process, such as hardening, drying, or chemical changes. Kilns have been used for millennia to turn objects made from clay into ...

were used for drying kernels of wheat or barley, not otherwise easy in the changeable, temperate climate.

The early Picts are associated with piracy and raiding along the coasts of

The early Picts are associated with piracy and raiding along the coasts of Roman Britain

Roman Britain was the territory that became the Roman province of ''Britannia'' after the Roman conquest of Britain, consisting of a large part of the island of Great Britain. The occupation lasted from AD 43 to AD 410.

Julius Caes ...

. Even in the Late Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

, the line between traders and pirates was unclear, so that Pictish pirates were probably merchants on other occasions. It is generally assumed that trade collapsed with the Roman Empire, but this is to overstate the case. There is only limited evidence of long-distance trade with Pictland, but tableware and storage vessels from Gaul, probably transported up the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

, have been found. This trade may have been controlled from Dunadd

Dunadd (Scottish Gaelic ''Dún Ad'', "fort on the iverAdd", Old Irish ''Dún Att'') is a hillfort in Argyll and Bute, Scotland, dating from the Iron Age and early medieval period and is believed to be the capital of the ancient kingdom of Dál R ...

in Dál Riata, where such goods appear to have been common. While long-distance travel was unusual in Pictish times, it was far from unknown as stories of missionaries, travelling clerics and exiles show.

Broch

In archaeology, a broch is an British Iron Age, Iron Age drystone hollow-walled structure found in Scotland. Brochs belong to the classification "complex Atlantic roundhouse" devised by Scottish archaeologists in the 1980s.

Brochs are round ...

s are popularly associated with the Picts. Although built earlier in the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, with construction ending around 100 AD, they remained in use beyond the Pictish period. Crannogs

A crannog (; ; ) is typically a partially or entirely artificial island, usually constructed in lakes, bogs and estuarine waters of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Unlike the prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, which were built on shore ...

, which may originate in Neolithic

The Neolithic or New Stone Age (from Ancient Greek, Greek 'new' and 'stone') is an archaeological period, the final division of the Stone Age in Mesopotamia, Asia, Europe and Africa (c. 10,000 BCE to c. 2,000 BCE). It saw the Neolithic Revo ...

Scotland, may have been rebuilt, and some were still in use in the time of the Picts. The most common sort of buildings would have been roundhouses and rectangular timbered halls. While many churches were built in wood, from the early 8th century, if not earlier, some were built in stone.

The Picts are often said to have tattooed themselves, but evidence for this is limited. Naturalistic depictions of Pictish nobles, hunters and warriors, male and female, without obvious tattoos, are found on monumental stones. These include inscriptions in Latin and ogham

Ogham (also ogam and ogom, , Modern Irish: ; , later ) is an Early Medieval alphabet used primarily to write the early Irish language (in the "orthodox" inscriptions, 4th to 6th centuries AD), and later the Old Irish language ( scholastic ...

script, not all of which have been deciphered. The well-known Pictish symbols found on standing stones and other artefacts have defied attempts at translation over the centuries. Pictish art can be classed as "Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

" and later as Insular. Irish poets portrayed their Pictish counterparts as very much like themselves.

Religion

Early Pictish religion is presumed to have resembledCeltic polytheism

Ancient Celtic religion, commonly known as Celtic paganism, was the religion of the ancient Celts, Celtic peoples of Europe. Because there are no extant native records of their beliefs, evidence about their religion is gleaned from archaeology, ...

in general, although only place names remain from the pre-Christian era. When the Pictish elite converted to Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

is uncertain, but traditions place Saint Palladius in Pictland after he left Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

, and link Abernethy with Saint Brigid of Kildare

Saint Brigid of Kildare or Saint Brigid of Ireland (; Classical Irish: ''Brighid''; ; ) is the patroness saint (or 'mother saint') of Ireland, and one of its three national saints along with Patrick and Columba. According to medieval Irish ...

. Saint Patrick

Saint Patrick (; or ; ) was a fifth-century Romano-British culture, Romano-British Christian missionary and Archbishop of Armagh, bishop in Gaelic Ireland, Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Irelan ...

refers to "apostate Picts", while the poem ''Y Gododdin

''Y Gododdin'' () is a medieval Welsh poem consisting of a series of elegies to the men of the Brittonic kingdom of Gododdin and its allies who, according to the conventional interpretation, died fighting the Angles of Deira and Bernicia ...

'' does not remark on the Picts as pagans. Bede wrote that Saint Ninian

Ninian is a Christian saint, first mentioned in the 8th century as being an early missionary among the Pictish peoples of what is now Scotland. For this reason, he is known as the Apostle to the Southern Picts, and there are numerous dedicatio ...

(confused by some with Saint Finnian of Moville

Finnian of Movilla (–589) was an Irish Christian missionary. His feast day is 10 September.

Origins and life

Finnian (sometimes called Finbarr "the white head", a reference to his fair hair), was a Christian missionary in medieval Ir ...

, who died ), had converted the southern Picts. Recent archaeological work at Portmahomack

Portmahomack (; 'Haven of My .e. 'Saint'Colmóc') is a small fishing village in Easter Ross, Scotland. It is situated in the Tarbat Peninsula in the parish of Tarbat. Tarbat Ness Lighthouse is about from the village at the end of the Tar ...

places the foundation of the monastery

A monastery is a building or complex of buildings comprising the domestic quarters and workplaces of Monasticism, monastics, monks or nuns, whether living in Cenobitic monasticism, communities or alone (hermits). A monastery generally includes a ...

there, an area once assumed to be among the last converted, in the late 6th century. This is contemporary with Bridei mac Maelchon and Columba, but the process of establishing Christianity throughout Pictland will have extended over a much longer period.

Pictland was not solely influenced by Iona

Iona (; , sometimes simply ''Ì'') is an island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaeli ...

and Ireland. It also had ties to churches in Northumbria, as seen in the reign of Nechtan mac Der Ilei

Naiton son of Der-Ilei (; died 732), also called Naiton son of Dargart (), was king of the Picts between 706–724 and between 728–729. He succeeded his brother Bridei IV in 706. He is associated with significant religious reforms in Pictlan ...

. The reported expulsion of Ionan monks and clergy by Nechtan in 717 may have been related to the controversy over the dating of Easter

Easter, also called Pascha ( Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in t ...

, and the manner of tonsure

Tonsure () is the practice of cutting or shaving some or all of the hair on the scalp as a sign of religious devotion or humility. The term originates from the Latin word ' (meaning "clipping" or "shearing") and referred to a specific practice in ...

, where Nechtan appears to have supported the Roman usages, but may equally have been intended to increase royal power over the church. Nonetheless, the evidence of place names suggests a wide area of Ionan influence in Pictland. Likewise, the ''Cáin Adomnáin

The ''Cáin Adomnáin'' (, , "Law of Adomnán"), also known as the ''Lex Innocentium'' (Law of Innocents), was promulgated amongst a gathering of Gaels, Gaelic and Picts, Pictish notables at the Synod of Birr in 697 in Ireland, 697. It is named ...

'' (Law of Adomnán

Adomnán or Adamnán of Iona (; , ''Adomnanus''; 624 – 704), also known as Eunan ( ; from ), was an abbot of Iona Abbey ( 679–704), hagiographer, statesman, canon jurist, and Christian saint, saint. He was the author of the ''Life ...

, ''Lex Innocentium'') counts Nechtan's brother Bridei among its guarantors.

The importance of monastic centres in Pictland was not as great as in Ireland. In areas that have been studied, such as Strathspey and Perthshire

Perthshire (Scottish English, locally: ; ), officially the County of Perth, is a Shires of Scotland, historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore, Angus and Perth & Kinross, Strathmore ...

, it appears that the parochial structure of the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

existed in early medieval times. Among the major religious sites of eastern Pictland were Portmahomack, Cennrígmonaid (later St Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ʰʲɪʎˈrˠiː.ɪɲ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

), Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, , from , "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to the geological Highland Boundar ...

, Abernethy and Rosemarkie

Rosemarkie (, from meaning "promontory of the horse stream") is a village on the south coast of the Black Isle peninsula in Ross-shire (Ross and Cromarty), northern Scotland.

Geography

Rosemarkie lies a quarter of a mile east of the town of ...

. It appears that these are associated with Pictish kings, which argue for a considerable degree of royal patronage and control of the church. Portmahomack in particular has been the subject of recent excavation and research, published by Martin Carver

Martin Oswald Hugh Carver, FSA, Hon FSA Scot, (born 8 July 1941) is Emeritus Professor of Archaeology at the University of York, England, director of the Sutton Hoo Research Project and a leading exponent of new methods in excavation and sur ...

.

The cult of saints was, as throughout Christian lands, of great importance in later Pictland. While kings might venerate great saints, such as Saint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

in the case of Nechtan, and perhaps Saint Andrew

Andrew the Apostle ( ; ; ; ) was an apostle of Jesus. According to the New Testament, he was a fisherman and one of the Twelve Apostles chosen by Jesus.

The title First-Called () used by the Eastern Orthodox Church stems from the Gospel of Jo ...

in the case of the second Óengus mac Fergusa, many lesser saints, some now obscure, were important. The Pictish Saint Drostan

Saint Drostan (d. early 7th century), also known as Drustan, was the founder and abbot of the monastery of Old Deer in Aberdeenshire. His relics were later translated to the church at New Aberdour and his holy well lies nearby.

Biography

Dros ...

appears to have had a wide following in the north in earlier times, although he was all but forgotten by the 12th century. Saint Serf

Saint Serf or Serbán (''Servanus'') () is a saint of Scotland. Serf was venerated in western Fife. He is called the apostle of Orkney, with less historical plausibility. Saint Serf is connected with Saint Mungo's Church near Simonburn, Northumbe ...

of Culross

Culross (/ˈkurəs/) (Scottish Gaelic: ''Cuileann Ros'', 'holly point or promontory') is a village and former royal burgh, and parish, in Fife, Scotland.

According to the 2006 estimate, the village has a population of 395. Originally, Culross ...

was associated with Nechtan's brother Bridei. It appears, as is well known in later times, that noble kin groups had their own patron saints, and their own churches or abbeys.

Art

Pictish art is primarily associated with monumental stones, but also includes smaller objects of stone and bone, and metalwork such as

Pictish art is primarily associated with monumental stones, but also includes smaller objects of stone and bone, and metalwork such as brooches

A brooch (, ) is a decorative jewellery item designed to be attached to garments, often to fasten them together. It is usually made of metal, often silver or gold or some other material. Brooches are frequently decorated with enamel or with gem ...

. It uses a distinctive form of the general Celtic early medieval development of La Tène style with increasing influences from the Insular art

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the sub-Roman Britain, post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from ''insula'', the Latin language, Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland ...

of 7th and 8th century Ireland and Northumbria

Northumbria () was an early medieval Heptarchy, kingdom in what is now Northern England and Scottish Lowlands, South Scotland.

The name derives from the Old English meaning "the people or province north of the Humber", as opposed to the Sout ...

, and then Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

and Irish art

Irish art is art produced in the island of Ireland, and by artists from Ireland. The term normally includes Irish-born artists as well as expatriates settled in Ireland. Its history starts around 3200 BC with Neolithic stone carvings at the Newg ...

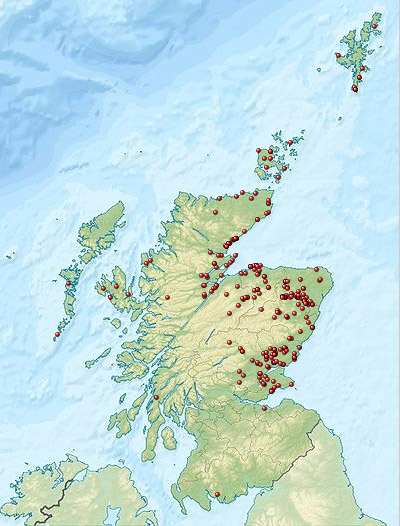

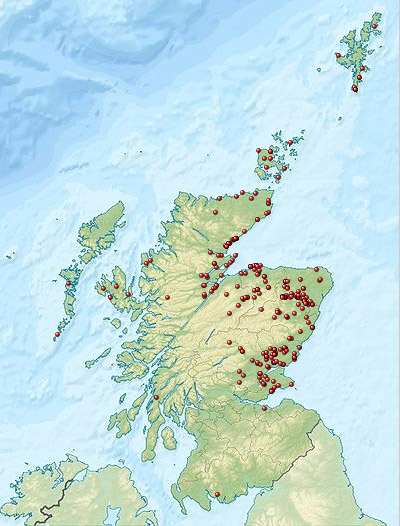

as the early medieval period continues. The most well-known surviving examples are the many Pictish stones located across Pictland.

The symbols and patterns consist of animals including the Pictish Beast

The Pictish Beast (sometimes Pictish Dragon or Pictish Elephant) is a conventional representation of an animal, distinct to the early medieval culture of the Picts of Scotland. The great majority of surviving examples are on Pictish stones.

T ...

, the "rectangle", the "mirror and comb", "double-disc and Z-rod" and the "crescent and V-rod", among many others. There are also bosses and lenses with pelta and spiral designs. The patterns are curvilinear with hatchings. The cross-slabs are carved with Pictish symbols, Insular-derived interlace and Christian imagery, though interpretation is often difficult due to wear and obscurity. Several of the Christian images carved on various stones, such as David the harpist, Daniel and the lion, or scenes of St Paul and St Anthony meeting in the desert, have been influenced by the Insular manuscript tradition.

Pictish metalwork is found throughout Pictland (modern-day Scotland) and also further south; the Picts appeared to have a considerable amount of silver available, probably from raiding further south, or the payment of subsidies to keep them from doing so. The very large hoard of late Roman hacksilver

Hacksilver (sometimes referred to as hacksilber) consists of fragments of cut and bent silver items that were used as bullion or as currency by weight during the Middle Ages.

Use

Hacksilver was common among the Norsemen or Vikings, as a result ...

found at Traprain Law

Traprain Law is a hill east of Haddington, East Lothian, Scotland. It is the site of a hill fort or possibly ''oppidum'', which covered at its maximum extent about . It is the site of the Traprain Law Treasure, the largest Roman silver hoard ...

may have originated in either way. The largest hoard of early Pictish metalwork was found in 1819 at Norrie's Law

Norrie's Law hoard is a sixth century silver hoard discovered in 1819 at a small mound in Largo, Fife, Scotland. Found by an unknown person or persons, most of the hoard was illegally sold or given away, and has disappeared. Remaining items of ...

in Fife, but unfortunately much was dispersed and melted down ( Scots law on treasure finds has always been unhelpful to preservation). A famous 7th century silver and enamel plaque from the hoard has a "Z-rod", one of the Pictish symbols, in a particularly well-preserved and elegant form; unfortunately few comparable pieces have survived.

Over ten heavy silver chains, some over 0.5m long, have been found from this period; the double-linked Whitecleuch Chain

The Whitecleuch Chain is a large Pictish silver chain that was found in Whitecleuch, Lanarkshire, Scotland in 1869. A high status piece, it is likely to have been worn as a choker neck ornament for ceremonial purposes. It dates from around 400 ...

is one of only two that have a penannular linking piece for the ends, with symbol decoration including enamel, which shows how these were probably used as "choker" necklaces.

In the 8th and 9th centuries, after Christianization, the Pictish elite adopted a particular form of the Irish Celtic brooch

The Celtic brooch, more properly called the penannular brooch, and its closely related type, the pseudo-penannular brooch, are types of brooch clothes fasteners, often rather large; penannular means formed as an incomplete ring. They are especial ...

, preferring true penannular brooches with lobed terminals. Some older Irish brooches were adapted to the Pictish style, for example, the c. 8th century Breadalbane Brooch now in the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

. The St Ninian's Isle Treasure

The St Ninian's Isle Treasure, found on St Ninian's Isle, Shetland, Scotland, in 1958, is the best example of surviving silver metalwork from the early medieval period in Scotland. The 28-piece hoard includes various silver metalwork items, inc ...

(c. 750–825 AD) contains the best collection of Pictish forms. Other characteristics of Pictish metalwork are dotted backgrounds or designs and animal forms influenced by Insular art. The 8th century Monymusk Reliquary

The Monymusk Reliquary is an eighth century Scottish House-shaped shrine, house-shape reliquaryMoss (2014), p. 286 made of wood and metal characterised by an Hiberno-Saxon art, Insular fusion of Gaels, Gaelic and Picts, Pictish design and Anglo-S ...

has elements of Pictish and Irish styles.

Rodney's Stone

Rodney's Stone is a high Pictish cross slab now located close on the approach way to Brodie Castle, near Forres, Moray, Scotland. It was originally found nearby in the grounds of the old church of Dyke and Moy.

Description

Rodney's Stone is ...

(back-face), Brodie Castle

Brodie Castle is a well-preserved Z-plan tower house located about west of Forres, in Moray, Scotland. The castle is a Category A listed building, and the grounds are included in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland.

...

, Forres

Forres (; ) is a town and former royal burgh in the north of Scotland on the County of Moray, Moray coast, approximately northeast of Inverness and west of Elgin, Moray, Elgin. Forres has been a winner of the Scotland in Bloom award on several ...

File:Aberlemnokirkyardcropped.jpg, The Aberlemno

Aberlemno (, IPA: �opəɾˈʎɛunəx is a Civil parishes in Scotland, parish and small village in the Scotland, Scottish council area of Angus, Scotland, Angus. It is noted for three large carved Pictish stones (and one fragment) dating from t ...

Kirkyard Stone, Class II Pictish stone

File:ArtCelteScotlandFibuleExpoClunydetail.jpg, The Rogart Brooch