phospholipid bilayers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of

The lipid bilayer is very thin compared to its lateral dimensions. If a typical mammalian cell (diameter ~10 micrometers) were magnified to the size of a watermelon (~1 ft/30 cm), the lipid bilayer making up the plasma membrane would be about as thick as a piece of office paper. Despite being only a few nanometers thick, the bilayer is composed of several distinct chemical regions across its cross-section. These regions and their interactions with the surrounding water have been characterized over the past several decades with x-ray reflectometry, neutron scattering, and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques.

The first region on either side of the bilayer is the hydrophilic headgroup. This portion of the membrane is completely hydrated and is typically around 0.8-0.9 nm thick. In

The lipid bilayer is very thin compared to its lateral dimensions. If a typical mammalian cell (diameter ~10 micrometers) were magnified to the size of a watermelon (~1 ft/30 cm), the lipid bilayer making up the plasma membrane would be about as thick as a piece of office paper. Despite being only a few nanometers thick, the bilayer is composed of several distinct chemical regions across its cross-section. These regions and their interactions with the surrounding water have been characterized over the past several decades with x-ray reflectometry, neutron scattering, and nuclear magnetic resonance techniques.

The first region on either side of the bilayer is the hydrophilic headgroup. This portion of the membrane is completely hydrated and is typically around 0.8-0.9 nm thick. In  Next to the hydrated region is an intermediate region that is only partially hydrated. This boundary layer is approximately 0.3 nm thick. Within this short distance, the water concentration drops from 2M on the headgroup side to nearly zero on the tail (core) side. The hydrophobic core of the bilayer is typically 3-4 nm thick, but this value varies with chain length and chemistry. Core thickness also varies significantly with temperature, in particular near a phase transition.

Next to the hydrated region is an intermediate region that is only partially hydrated. This boundary layer is approximately 0.3 nm thick. Within this short distance, the water concentration drops from 2M on the headgroup side to nearly zero on the tail (core) side. The hydrophobic core of the bilayer is typically 3-4 nm thick, but this value varies with chain length and chemistry. Core thickness also varies significantly with temperature, in particular near a phase transition.

At a given temperature a lipid bilayer can exist in either a liquid or a gel (solid) phase. All lipids have a characteristic temperature at which they transition (melt) from the gel to liquid phase. In both phases the lipid molecules are prevented from flip-flopping across the bilayer, but in liquid phase bilayers a given lipid will exchange locations with its neighbor millions of times a second. This

At a given temperature a lipid bilayer can exist in either a liquid or a gel (solid) phase. All lipids have a characteristic temperature at which they transition (melt) from the gel to liquid phase. In both phases the lipid molecules are prevented from flip-flopping across the bilayer, but in liquid phase bilayers a given lipid will exchange locations with its neighbor millions of times a second. This

The lipid bilayer is a difficult structure to study because it is so thin and fragile. To overcome these limitations, techniques have been developed to allow investigations of its structure and function.

The lipid bilayer is a difficult structure to study because it is so thin and fragile. To overcome these limitations, techniques have been developed to allow investigations of its structure and function.

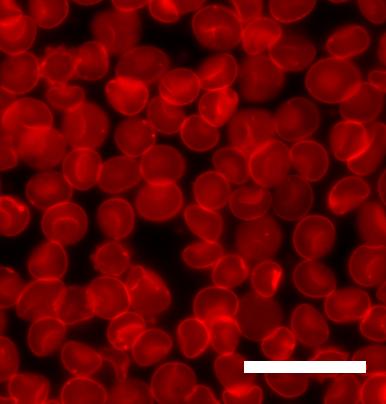

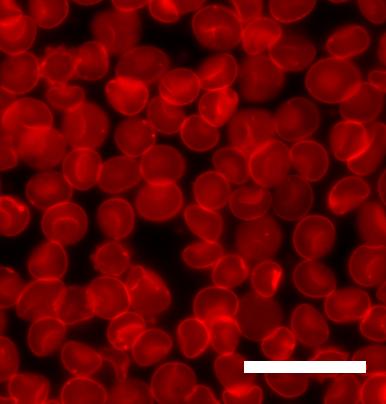

A lipid bilayer cannot be seen with a traditional microscope because it is too thin, so researchers often use fluorescence microscopy. A sample is excited with one wavelength of light and observed in another, so that only fluorescent molecules with a matching excitation and emission profile will be seen. A natural lipid bilayer is not fluorescent, so at least one fluorescent dye needs to be attached to some of the molecules in the bilayer. Resolution is usually limited to a few hundred nanometers, which is unfortunately much larger than the thickness of a lipid bilayer.

A lipid bilayer cannot be seen with a traditional microscope because it is too thin, so researchers often use fluorescence microscopy. A sample is excited with one wavelength of light and observed in another, so that only fluorescent molecules with a matching excitation and emission profile will be seen. A natural lipid bilayer is not fluorescent, so at least one fluorescent dye needs to be attached to some of the molecules in the bilayer. Resolution is usually limited to a few hundred nanometers, which is unfortunately much larger than the thickness of a lipid bilayer.

A new method to study lipid bilayers is Atomic force microscopy (AFM). Rather than using a beam of light or particles, a very small sharpened tip scans the surface by making physical contact with the bilayer and moving across it, like a record player needle. AFM is a promising technique because it has the potential to image with nanometer resolution at room temperature and even under water or physiological buffer, conditions necessary for natural bilayer behavior. Utilizing this capability, AFM has been used to examine dynamic bilayer behavior including the formation of transmembrane pores (holes) and phase transitions in supported bilayers. Another advantage is that AFM does not require fluorescent or isotopic labeling of the lipids, since the probe tip interacts mechanically with the bilayer surface. Because of this, the same scan can image both lipids and associated proteins, sometimes even with single-molecule resolution. AFM can also probe the mechanical nature of lipid bilayers.

A new method to study lipid bilayers is Atomic force microscopy (AFM). Rather than using a beam of light or particles, a very small sharpened tip scans the surface by making physical contact with the bilayer and moving across it, like a record player needle. AFM is a promising technique because it has the potential to image with nanometer resolution at room temperature and even under water or physiological buffer, conditions necessary for natural bilayer behavior. Utilizing this capability, AFM has been used to examine dynamic bilayer behavior including the formation of transmembrane pores (holes) and phase transitions in supported bilayers. Another advantage is that AFM does not require fluorescent or isotopic labeling of the lipids, since the probe tip interacts mechanically with the bilayer surface. Because of this, the same scan can image both lipids and associated proteins, sometimes even with single-molecule resolution. AFM can also probe the mechanical nature of lipid bilayers.

Exocytosis in prokaryotes: Membrane vesicular exocytosis, popularly known as membrane vesicle trafficking, a Nobel prize-winning (year, 2013) process, is traditionally regarded as a prerogative of

Exocytosis in prokaryotes: Membrane vesicular exocytosis, popularly known as membrane vesicle trafficking, a Nobel prize-winning (year, 2013) process, is traditionally regarded as a prerogative of

Lipid bilayers are large enough structures to have some of the mechanical properties of liquids or solids. The area compression modulus Ka, bending modulus Kb, and edge energy , can be used to describe them. Solid lipid bilayers also have a shear modulus, but like any liquid, the shear modulus is zero for fluid bilayers. These mechanical properties affect how the membrane functions. Ka and Kb affect the ability of proteins and small molecules to insert into the bilayer, and bilayer mechanical properties have been shown to alter the function of mechanically activated ion channels. Bilayer mechanical properties also govern what types of stress a cell can withstand without tearing. Although lipid bilayers can easily bend, most cannot stretch more than a few percent before rupturing.

As discussed in the Structure and organization section, the hydrophobic attraction of lipid tails in water is the primary force holding lipid bilayers together. Thus, the elastic modulus of the bilayer is primarily determined by how much extra area is exposed to water when the lipid molecules are stretched apart. It is not surprising given this understanding of the forces involved that studies have shown that Ka varies strongly with

Lipid bilayers are large enough structures to have some of the mechanical properties of liquids or solids. The area compression modulus Ka, bending modulus Kb, and edge energy , can be used to describe them. Solid lipid bilayers also have a shear modulus, but like any liquid, the shear modulus is zero for fluid bilayers. These mechanical properties affect how the membrane functions. Ka and Kb affect the ability of proteins and small molecules to insert into the bilayer, and bilayer mechanical properties have been shown to alter the function of mechanically activated ion channels. Bilayer mechanical properties also govern what types of stress a cell can withstand without tearing. Although lipid bilayers can easily bend, most cannot stretch more than a few percent before rupturing.

As discussed in the Structure and organization section, the hydrophobic attraction of lipid tails in water is the primary force holding lipid bilayers together. Thus, the elastic modulus of the bilayer is primarily determined by how much extra area is exposed to water when the lipid molecules are stretched apart. It is not surprising given this understanding of the forces involved that studies have shown that Ka varies strongly with

Fusion is the process by which two lipid bilayers merge, resulting in one connected structure. If this fusion proceeds completely through both leaflets of both bilayers, a water-filled bridge is formed and the solutions contained by the bilayers can mix. Alternatively, if only one leaflet from each bilayer is involved in the fusion process, the bilayers are said to be hemifused. Fusion is involved in many cellular processes, in particular in

Fusion is the process by which two lipid bilayers merge, resulting in one connected structure. If this fusion proceeds completely through both leaflets of both bilayers, a water-filled bridge is formed and the solutions contained by the bilayers can mix. Alternatively, if only one leaflet from each bilayer is involved in the fusion process, the bilayers are said to be hemifused. Fusion is involved in many cellular processes, in particular in

The situation is further complicated when considering fusion ''in vivo'' since biological fusion is almost always regulated by the action of membrane-associated proteins. The first of these proteins to be studied were the viral fusion proteins, which allow an enveloped

The situation is further complicated when considering fusion ''in vivo'' since biological fusion is almost always regulated by the action of membrane-associated proteins. The first of these proteins to be studied were the viral fusion proteins, which allow an enveloped

Biacore Inc. Retrieved Feb 12, 2009. and Nanion Inc., which has developed an Planar patch clamp, automated patch clamping system. A supported lipid bilayer (SLB) as described above has achieved commercial success as a screening technique to measure the permeability of drugs. This parallel artificial membrane permeability assay ( PAMPA) technique measures the permeability across specifically formulated lipid cocktail(s) found to be highly correlated with Caco-2 cultures, the

LIPIDAT

An extensive database of lipid physical properties

Simulations and publication links related to the cross sectional structure of lipid bilayers. {{DEFAULTSORT:Lipid Bilayer Biological matter Membrane biology

lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

s. These membranes form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

s of almost all organisms

An organism is any living thing that functions as an individual. Such a definition raises more problems than it solves, not least because the concept of an individual is also difficult. Many criteria, few of them widely accepted, have been pr ...

and many virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es are made of a lipid bilayer, as are the nuclear membrane surrounding the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

, and membranes of the membrane-bound organelles in the cell. The lipid bilayer is the barrier that keeps ions, protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s and other molecules where they are needed and prevents them from diffusing into areas where they should not be. Lipid bilayers are ideally suited to this role, even though they are only a few nanometers in width, because they are impermeable to most water-soluble ( hydrophilic) molecules. Bilayers are particularly impermeable to ions, which allows cells to regulate salt concentrations and pH by transporting ions across their membranes using proteins called ion pumps.

Biological bilayers are usually composed of amphiphilic phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s that have a hydrophilic phosphate head and a hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

tail consisting of two fatty acid chains. Phospholipids with certain head groups can alter the surface chemistry of a bilayer and can, for example, serve as signals as well as "anchors" for other molecules in the membranes of cells. Just like the heads, the tails of lipids can also affect membrane properties, for instance by determining the phase of the bilayer. The bilayer can adopt a solid gel phase state at lower temperatures but undergo phase transition

In physics, chemistry, and other related fields like biology, a phase transition (or phase change) is the physical process of transition between one state of a medium and another. Commonly the term is used to refer to changes among the basic Sta ...

to a fluid state at higher temperatures, and the chemical properties of the lipids' tails influence at which temperature this happens. The packing of lipids within the bilayer also affects its mechanical properties, including its resistance to stretching and bending. Many of these properties have been studied with the use of artificial "model" bilayers produced in a lab. Vesicles made by model bilayers have also been used clinically to deliver drugs.

The structure of biological membranes typically includes several types of molecules in addition to the phospholipids comprising the bilayer. A particularly important example in animal cells is cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

, which helps strengthen the bilayer and decrease its permeability. Cholesterol also helps regulate the activity of certain integral membrane proteins. Integral membrane proteins function when incorporated into a lipid bilayer, and they are held tightly to the lipid bilayer with the help of an annular lipid shell. Because bilayers define the boundaries of the cell and its compartments, these membrane proteins are involved in many intra- and inter-cellular signaling processes. Certain kinds of membrane proteins are involved in the process of fusing two bilayers together. This fusion allows the joining of two distinct structures as in the acrosome reaction during fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give ...

of an egg by a sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

, or the entry of a virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

into a cell. Because lipid bilayers are fragile and invisible in a traditional microscope, they are a challenge to study. Experiments on bilayers often require advanced techniques like electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy.

Structure and organization

When phospholipids are exposed to water, they self-assemble into a two-layered sheet with the hydrophobic tails pointing toward the center of the sheet. This arrangement results in two 'leaflets' that are each a single molecular layer. The center of this bilayer contains almost no water and excludes molecules likesugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecul ...

s or salts that dissolve in water. The assembly process and maintenance are driven by aggregation of hydrophobic molecules (also called the hydrophobic effect). This complex process includes non-covalent interactions such as van der Waals force

In molecular physics and chemistry, the van der Waals force (sometimes van der Waals' force) is a distance-dependent interaction between atoms or molecules. Unlike ionic or covalent bonds, these attractions do not result from a chemical elec ...

s, electrostatic and hydrogen bonds.

Cross-section analysis

phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

bilayers the phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

group is located within this hydrated region, approximately 0.5 nm outside the hydrophobic core. In some cases, the hydrated region can extend much further, for instance in lipids with a large protein or long sugar chain grafted to the head. One common example of such a modification in nature is the lipopolysaccharide coat on a bacterial outer membrane.

Next to the hydrated region is an intermediate region that is only partially hydrated. This boundary layer is approximately 0.3 nm thick. Within this short distance, the water concentration drops from 2M on the headgroup side to nearly zero on the tail (core) side. The hydrophobic core of the bilayer is typically 3-4 nm thick, but this value varies with chain length and chemistry. Core thickness also varies significantly with temperature, in particular near a phase transition.

Next to the hydrated region is an intermediate region that is only partially hydrated. This boundary layer is approximately 0.3 nm thick. Within this short distance, the water concentration drops from 2M on the headgroup side to nearly zero on the tail (core) side. The hydrophobic core of the bilayer is typically 3-4 nm thick, but this value varies with chain length and chemistry. Core thickness also varies significantly with temperature, in particular near a phase transition.

Asymmetry

In many naturally occurring bilayers, the compositions of the inner and outer membrane leaflets are different. In human red blood cells, the inner (cytoplasmic) leaflet is composed mostly of phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylserine and phosphatidylinositol and its phosphorylated derivatives. By contrast, the outer (extracellular) leaflet is based on phosphatidylcholine, sphingomyelin and a variety of glycolipids. In some cases, this asymmetry is based on where the lipids are made in the cell and reflects their initial orientation. The biological functions of lipid asymmetry are imperfectly understood, although it is clear that it is used in several different situations. For example, when a cell undergoesapoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, the phosphatidylserine – normally localised to the cytoplasmic leaflet – is transferred to the outer surface: There, it is recognised by a macrophage

Macrophages (; abbreviated MPhi, φ, MΦ or MP) are a type of white blood cell of the innate immune system that engulf and digest pathogens, such as cancer cells, microbes, cellular debris and foreign substances, which do not have proteins that ...

that then actively scavenges the dying cell.

Lipid asymmetry arises, at least in part, from the fact that most phospholipids are synthesised and initially inserted into the inner monolayer: those that constitute the outer monolayer are then transported from the inner monolayer by a class of enzymes called flippases. Other lipids, such as sphingomyelin, appear to be synthesised at the external leaflet. Flippases are members of a larger family of lipid transport molecules that also includes floppases, which transfer lipids in the opposite direction, and scramblases, which randomize lipid distribution across lipid bilayers (as in apoptotic cells). In any case, once lipid asymmetry is established, it does not normally dissipate quickly because spontaneous flip-flop of lipids between leaflets is extremely slow. It has recently been shown that cholesterol also seems to play an important role in creating and maintaining bilayer assymetry.

It is possible to mimic this asymmetry in the laboratory in model bilayer systems. Certain types of very small artificial vesicle will automatically make themselves slightly asymmetric, although the mechanism by which this asymmetry is generated is very different from that in cells. By utilizing two different monolayers in Langmuir–Blodgett deposition or a combination of Langmuir–Blodgett and vesicle rupture deposition it is also possible to synthesize an asymmetric planar bilayer. This asymmetry may be lost over time as lipids in supported bilayers can be prone to flip-flop. However, it has been reported that lipid flip-flop is slow compare to cholesterol and other smaller molecules.

It has been reported that the organization and dynamics of the lipid monolayers in a bilayer are coupled. For example, introduction of obstructions in one monolayer can slow down the lateral diffusion in both monolayers. In addition, phase separation in one monolayer can also induce phase separation in other monolayer even when other monolayer can not phase separate by itself.

Phases and phase transitions

random walk

In mathematics, a random walk, sometimes known as a drunkard's walk, is a stochastic process that describes a path that consists of a succession of random steps on some Space (mathematics), mathematical space.

An elementary example of a rand ...

exchange allows lipid to diffuse and thus wander across the surface of the membrane.Unlike liquid phase bilayers, the lipids in a gel phase bilayer have less mobility.

The phase behavior of lipid bilayers is determined largely by the strength of the attractive Van der Waals interactions between adjacent lipid molecules. Longer-tailed lipids have more area over which to interact, increasing the strength of this interaction and, as a consequence, decreasing the lipid mobility. Thus, at a given temperature, a short-tailed lipid will be more fluid than an otherwise identical long-tailed lipid. Transition temperature can also be affected by the degree of unsaturation of the lipid tails. An unsaturated double bond can produce a kink in the alkane chain, disrupting the lipid packing. This disruption creates extra free space within the bilayer that allows additional flexibility in the adjacent chains. An example of this effect can be noted in everyday life as butter, which has a large percentage saturated fats, is solid at room temperature while vegetable oil, which is mostly unsaturated, is liquid.

Most natural membranes are a complex mixture of different lipid molecules. If some of the components are liquid at a given temperature while others are in the gel phase, the two phases can coexist in spatially separated regions, rather like an iceberg floating in the ocean. This phase separation plays a critical role in biochemical phenomena because membrane components such as proteins can partition into one or the other phase and thus be locally concentrated or activated. One particularly important component of many mixed phase systems is cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

, which modulates bilayer permeability, mechanical strength, and biochemical interactions.

Surface chemistry

While lipid tails primarily modulate bilayer phase behavior, it is the headgroup that determines the bilayer surface chemistry. Most natural bilayers are composed primarily ofphospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s, but sphingolipids and sterol

A sterol is any organic compound with a Skeletal formula, skeleton closely related to Cholestanol, cholestan-3-ol. The simplest sterol is gonan-3-ol, which has a formula of , and is derived from that of gonane by replacement of a hydrogen atom on ...

s such as cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

are also important components. Of the phospholipids, the most common headgroup is phosphatidylcholine (PC), accounting for about half the phospholipids in most mammalian cells. PC is a zwitterion

In chemistry, a zwitterion ( ; ), also called an inner salt or dipolar ion, is a molecule that contains an equal number of positively and negatively charged functional groups.

:

(1,2- dipolar compounds, such as ylides, are sometimes excluded from ...

ic headgroup, as it has a negative charge on the phosphate group and a positive charge on the amine but, because these local charges balance, no net charge.

Other headgroups are also present to varying degrees and can include phosphatidylserine (PS) phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) and phosphatidylglycerol (PG). These alternate headgroups often confer specific biological functionality that is highly context-dependent. For instance, PS presence on the extracellular membrane face of erythrocytes is a marker of cell apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, whereas PS in growth plate vesicles is necessary for the nucleation

In thermodynamics, nucleation is the first step in the formation of either a new Phase (matter), thermodynamic phase or Crystal structure, structure via self-assembly or self-organization within a substance or mixture. Nucleation is typically def ...

of hydroxyapatite

Hydroxyapatite (International Mineralogical Association, IMA name: hydroxylapatite) (Hap, HAp, or HA) is a naturally occurring mineral form of calcium apatite with the Chemical formula, formula , often written to denote that the Crystal struc ...

crystals and subsequent bone mineralization. Unlike PC, some of the other headgroups carry a net charge, which can alter the electrostatic interactions of small molecules with the bilayer.

Biological roles

Containment and separation

The primary role of the lipid bilayer in biology is to separateaqueous

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, also known as sodium chloride (NaCl), in wat ...

compartments from their surroundings. Without some form of barrier delineating "self" from "non-self", it is difficult to even define the concept of an organism or of life. This barrier takes the form of a lipid bilayer in all known life forms except for a few species of archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

that utilize a specially adapted lipid monolayer. It has even been proposed that the very first form of life may have been a simple lipid vesicle with virtually its sole biosynthetic capability being the production of more phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s. The partitioning ability of the lipid bilayer is based on the fact that hydrophilic molecules cannot easily cross the hydrophobic

In chemistry, hydrophobicity is the chemical property of a molecule (called a hydrophobe) that is seemingly repelled from a mass of water. In contrast, hydrophiles are attracted to water.

Hydrophobic molecules tend to be nonpolar and, thu ...

bilayer core, as discussed in Transport across the bilayer below. The nucleus, mitochondria and chloroplasts have two lipid bilayers, while other sub-cellular structures are surrounded by a single lipid bilayer (such as the plasma membrane, endoplasmic reticula, Golgi apparatus and lysosomes). See Organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

.

Prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s have only one lipid bilayer - the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

(also known as the plasma membrane). Many prokaryotes also have a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

, but the cell wall is composed of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s or long chain carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s, not lipids. In contrast, eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s have a range of organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s including the nucleus, mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

, lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

s and endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a part of a transportation system of the eukaryote, eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. The word endoplasmic means "within the cytoplasm", and reticulum is Latin for ...

. All of these sub-cellular compartments are surrounded by one or more lipid bilayers and, together, typically comprise the majority of the bilayer area present in the cell. In liver hepatocyte

A hepatocyte is a cell of the main parenchymal tissue of the liver. Hepatocytes make up 80% of the liver's mass.

These cells are involved in:

* Protein synthesis

* Protein storage

* Transformation of carbohydrates

* Synthesis of cholesterol, bi ...

s for example, the plasma membrane accounts for only two percent of the total bilayer area of the cell, whereas the endoplasmic reticulum contains more than fifty percent and the mitochondria a further thirty percent.

Signaling

The most familiar form of cellular signaling is likely synaptic transmission, whereby a nerve impulse that has reached the end of oneneuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

is conveyed to an adjacent neuron via the release of neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

s. This transmission is made possible by the action of synaptic vesicle

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles (or neurotransmitter vesicles) store various neurotransmitters that are exocytosis, released at the chemical synapse, synapse. The release is regulated by a voltage-dependent calcium channel. Vesicle (biology), Ves ...

s which are, inside the cell, loaded with the neurotransmitters to be released later. These loaded vesicles fuse with the cell membrane at the pre-synaptic terminal and their contents are released into the space outside the cell. The contents then diffuse across the synapse to the post-synaptic terminal.

Lipid bilayers are also involved in signal transduction through their role as the home of integral membrane proteins. This is an extremely broad and important class of biomolecule. It is estimated that up to a third of the human proteome

A proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. P ...

are membrane proteins. Some of these proteins are linked to the exterior of the cell membrane. An example of this is the CD59 protein, which identifies cells as "self" and thus inhibits their destruction by the immune system. The HIV virus evades the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

in part by grafting these proteins from the host membrane onto its own surface. Alternatively, some membrane proteins penetrate all the way through the bilayer and serve to relay individual signal events from the outside to the inside of the cell. The most common class of this type of protein is the G protein-coupled receptor

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), also known as seven-(pass)-transmembrane domain receptors, 7TM receptors, heptahelical receptors, serpentine receptors, and G protein-linked receptors (GPLR), form a large group of evolutionarily related ...

(GPCR). GPCRs are responsible for much of the cell's ability to sense its surroundings and, because of this important role, approximately 40% of all modern drugs are targeted at GPCRs.

In addition to protein- and solution-mediated processes, it is also possible for lipid bilayers to participate directly in signaling. A classic example of this is phosphatidylserine-triggered phagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

. Normally, phosphatidylserine is asymmetrically distributed in the cell membrane and is present only on the interior side. During programmed cell death a protein called a scramblase equilibrates this distribution, displaying phosphatidylserine on the extracellular bilayer face. The presence of phosphatidylserine then triggers phagocytosis to remove the dead or dying cell.

Characterization methods

The lipid bilayer is a difficult structure to study because it is so thin and fragile. To overcome these limitations, techniques have been developed to allow investigations of its structure and function.

The lipid bilayer is a difficult structure to study because it is so thin and fragile. To overcome these limitations, techniques have been developed to allow investigations of its structure and function.

Electrical measurements

Electrical measurements are a straightforward way to characterize an important function of a bilayer: its ability to segregate and prevent the flow of ions in solution. By applying a voltage across the bilayer and measuring the resulting current, the resistance of the bilayer is determined. This resistance is typically quite high (108 Ohm-cm2 or more) since the hydrophobic core is impermeable to charged species. The presence of even a few nanometer-scale holes results in a dramatic increase in current. The sensitivity of this system is such that even the activity of singleion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by Gating (electrophysiol ...

s can be resolved.

Fluorescence microscopy

A lipid bilayer cannot be seen with a traditional microscope because it is too thin, so researchers often use fluorescence microscopy. A sample is excited with one wavelength of light and observed in another, so that only fluorescent molecules with a matching excitation and emission profile will be seen. A natural lipid bilayer is not fluorescent, so at least one fluorescent dye needs to be attached to some of the molecules in the bilayer. Resolution is usually limited to a few hundred nanometers, which is unfortunately much larger than the thickness of a lipid bilayer.

A lipid bilayer cannot be seen with a traditional microscope because it is too thin, so researchers often use fluorescence microscopy. A sample is excited with one wavelength of light and observed in another, so that only fluorescent molecules with a matching excitation and emission profile will be seen. A natural lipid bilayer is not fluorescent, so at least one fluorescent dye needs to be attached to some of the molecules in the bilayer. Resolution is usually limited to a few hundred nanometers, which is unfortunately much larger than the thickness of a lipid bilayer.

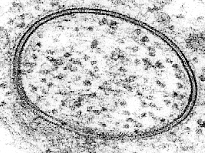

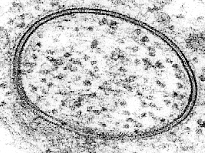

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy offers a higher resolution image. In anelectron microscope

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing it ...

, a beam of focused electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s interacts with the sample rather than a beam of light as in traditional microscopy. In conjunction with rapid freezing techniques, electron microscopy has also been used to study the mechanisms of inter- and intracellular transport, for instance in demonstrating that exocytotic vesicles are the means of chemical release at synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

s.

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

31P-Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, most commonly known as NMR spectroscopy or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), is a Spectroscopy, spectroscopic technique based on re-orientation of Atomic nucleus, atomic nuclei with non-zero nuclear sp ...

is widely used for studies of phospholipid bilayers and biological membranes in native conditions. The analysis of 31P-NMR spectra of lipids could provide a wide range of information about lipid bilayer packing, phase transitions (gel phase, physiological liquid crystal phase, ripple phases, non bilayer phases), lipid head group orientation/dynamics, and elastic properties of pure lipid bilayer and as a result of binding of proteins and other biomolecules.

Atomic force microscopy

A new method to study lipid bilayers is Atomic force microscopy (AFM). Rather than using a beam of light or particles, a very small sharpened tip scans the surface by making physical contact with the bilayer and moving across it, like a record player needle. AFM is a promising technique because it has the potential to image with nanometer resolution at room temperature and even under water or physiological buffer, conditions necessary for natural bilayer behavior. Utilizing this capability, AFM has been used to examine dynamic bilayer behavior including the formation of transmembrane pores (holes) and phase transitions in supported bilayers. Another advantage is that AFM does not require fluorescent or isotopic labeling of the lipids, since the probe tip interacts mechanically with the bilayer surface. Because of this, the same scan can image both lipids and associated proteins, sometimes even with single-molecule resolution. AFM can also probe the mechanical nature of lipid bilayers.

A new method to study lipid bilayers is Atomic force microscopy (AFM). Rather than using a beam of light or particles, a very small sharpened tip scans the surface by making physical contact with the bilayer and moving across it, like a record player needle. AFM is a promising technique because it has the potential to image with nanometer resolution at room temperature and even under water or physiological buffer, conditions necessary for natural bilayer behavior. Utilizing this capability, AFM has been used to examine dynamic bilayer behavior including the formation of transmembrane pores (holes) and phase transitions in supported bilayers. Another advantage is that AFM does not require fluorescent or isotopic labeling of the lipids, since the probe tip interacts mechanically with the bilayer surface. Because of this, the same scan can image both lipids and associated proteins, sometimes even with single-molecule resolution. AFM can also probe the mechanical nature of lipid bilayers.

Dual polarisation interferometry

Lipid bilayers exhibit high levels ofbirefringence

Birefringence, also called double refraction, is the optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light. These optically anisotropic materials are described as birefrin ...

where the refractive index in the plane of the bilayer differs from that perpendicular by as much as 0.1 refractive index

In optics, the refractive index (or refraction index) of an optical medium is the ratio of the apparent speed of light in the air or vacuum to the speed in the medium. The refractive index determines how much the path of light is bent, or refrac ...

units. This has been used to characterise the degree of order and disruption in bilayers using dual polarisation interferometry to understand mechanisms of protein interaction.

Quantum chemical calculations

Lipid bilayers are complicated molecular systems with many degrees of freedom. Thus, atomistic simulation of membrane and in particular ab initio calculations of its properties is difficult and computationally expensive. Quantum chemical calculations has recently been successfully performed to estimatedipole

In physics, a dipole () is an electromagnetic phenomenon which occurs in two ways:

* An electric dipole moment, electric dipole deals with the separation of the positive and negative electric charges found in any electromagnetic system. A simple ...

and quadrupole moments of lipid membranes.

Transport across the bilayer

Passive diffusion

Most polar molecules have low solubility in thehydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and Hydrophobe, hydrophobic; their odor is usually fain ...

core of a lipid bilayer and, as a consequence, have low permeability coefficients across the bilayer. This effect is particularly pronounced for charged species, which have even lower permeability coefficients than neutral polar molecules. Anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

s typically have a higher rate of diffusion through bilayers than cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s. Compared to ions, water molecules actually have a relatively large permeability through the bilayer, as evidenced by osmotic swelling. When a cell or vesicle with a high interior salt concentration is placed in a solution with a low salt concentration it will swell and eventually burst. Such a result would not be observed unless water was able to pass through the bilayer with relative ease. The anomalously large permeability of water through bilayers is still not completely understood and continues to be the subject of active debate. Small uncharged apolar molecules diffuse through lipid bilayers many orders of magnitude faster than ions or water. This applies both to fats and organic solvents like chloroform

Chloroform, or trichloromethane (often abbreviated as TCM), is an organochloride with the formula and a common solvent. It is a volatile, colorless, sweet-smelling, dense liquid produced on a large scale as a precursor to refrigerants and po ...

and ether. Regardless of their polar character larger molecules diffuse more slowly across lipid bilayers than small molecules.

Ion pumps and channels

Two special classes of protein deal with the ionic gradients found across cellular and sub-cellular membranes in nature-ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by Gating (electrophysiol ...

s and ion pumps. Both pumps and channels are integral membrane proteins that pass through the bilayer, but their roles are quite different. Ion pumps are the proteins that build and maintain the chemical gradients by utilizing an external energy source to move ions against the concentration gradient to an area of higher chemical potential

In thermodynamics, the chemical potential of a Chemical specie, species is the energy that can be absorbed or released due to a change of the particle number of the given species, e.g. in a chemical reaction or phase transition. The chemical potent ...

. The energy source can be ATP, as is the case for the Na+-K+ ATPase. Alternatively, the energy source can be another chemical gradient already in place, as in the Ca2+/Na+ antiporter. It is through the action of ion pumps that cells are able to regulate pH via the pumping of protons.

In contrast to ion pumps, ion channels do not build chemical gradients but rather dissipate them in order to perform work or send a signal. Probably the most familiar and best studied example is the voltage-gated Na+ channel, which allows conduction of an action potential

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific Cell (biology), cell rapidly ri ...

along neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

s. All ion pumps have some sort of trigger or "gating" mechanism. In the previous example it was electrical bias, but other channels can be activated by binding a molecular agonist or through a conformational change in another nearby protein.

Endocytosis and exocytosis

Some molecules or particles are too large or too hydrophilic to pass through a lipid bilayer. Other molecules could pass through the bilayer but must be transported rapidly in such large numbers that channel-type transport is impractical. In both cases, these types of cargo can be moved across the cell membrane through fusion or budding of vesicles. When a vesicle is produced inside the cell and fuses with the plasma membrane to release its contents into the extracellular space, this process is known as exocytosis. In the reverse process, a region of the cell membrane will dimple inwards and eventually pinch off, enclosing a portion of the extracellular fluid to transport it into the cell. Endocytosis and exocytosis rely on very different molecular machinery to function, but the two processes are intimately linked and could not work without each other. The primary mechanism of this interdependence is the large amount of lipid material involved. In a typical cell, an area of bilayer equivalent to the entire plasma membrane travels through the endocytosis/exocytosis cycle in about half an hour. Exocytosis in prokaryotes: Membrane vesicular exocytosis, popularly known as membrane vesicle trafficking, a Nobel prize-winning (year, 2013) process, is traditionally regarded as a prerogative of

Exocytosis in prokaryotes: Membrane vesicular exocytosis, popularly known as membrane vesicle trafficking, a Nobel prize-winning (year, 2013) process, is traditionally regarded as a prerogative of eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

cells. This ''myth'' was however broken with the revelation that nanovesicles, popularly known as bacterial outer membrane vesicles

Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) are vesicle (biology and chemistry), vesicles released from the bacterial outer membrane, outer membranes of Gram-negative bacteria. While Gram-positive bacteria release vesicles as well, those vesicles fall under ...

, released by gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelope consists ...

microbes, translocate bacterial signal molecules to host or target cells to carry out multiple processes in favour of the secreting microbe e.g., in ''host cell invasion'' and microbe-environment interactions, in general.

Electroporation

Electroporation is the rapid increase in bilayer permeability induced by the application of a large artificial electric field across the membrane. Experimentally, electroporation is used to introduce hydrophilic molecules into cells. It is a particularly useful technique for large highly charged molecules such asDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

, which would never passively diffuse across the hydrophobic bilayer core. Because of this, electroporation is one of the key methods of transfection as well as bacterial transformation. It has even been proposed that electroporation resulting from lightning

Lightning is a natural phenomenon consisting of electrostatic discharges occurring through the atmosphere between two electrically charged regions. One or both regions are within the atmosphere, with the second region sometimes occurring on ...

strikes could be a mechanism of natural horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

.

Mechanics

osmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a Solution (chemistry), solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a soluti ...

but only weakly with tail length and unsaturation. Because the forces involved are so small, it is difficult to experimentally determine Ka. Most techniques require sophisticated microscopy and very sensitive measurement equipment.

In contrast to Ka, which is a measure of how much energy is needed to stretch the bilayer, Kb is a measure of how much energy is needed to bend or flex the bilayer. Formally, bending modulus is defined as the energy required to deform a membrane from its intrinsic curvature to some other curvature. Intrinsic curvature is defined by the ratio of the diameter of the head group to that of the tail group. For two-tailed PC lipids, this ratio is nearly one so the intrinsic curvature is nearly zero. If a particular lipid has too large a deviation from zero intrinsic curvature it will not form a bilayer and will instead form other phases such as micelles or inverted micelles. Addition of small hydrophilic molecules like sucrose into mixed lipid lamellar liposomes made from galactolipid-rich thylakoid membranes destabilises bilayers into the micellar phase.

is a measure of how much energy it takes to expose a bilayer edge to water by tearing the bilayer or creating a hole in it. The origin of this energy is the fact that creating such an interface exposes some of the lipid tails to water, but the exact orientation of these border lipids is unknown. There is some evidence that both hydrophobic (tails straight) and hydrophilic (heads curved around) pores can coexist.

Fusion

eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s, since the eukaryotic cell is extensively sub-divided by lipid bilayer membranes. Exocytosis, fertilization

Fertilisation or fertilization (see American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give ...

of an egg by sperm activation, and transport of waste products to the lysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

are a few of the many eukaryotic processes that rely on some form of fusion. Even the entry of pathogens can be governed by fusion, as many bilayer-coated virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es have dedicated fusion proteins to gain entry into the host cell.

There are four fundamental steps in the fusion process. First, the involved membranes must aggregate, approaching each other to within several nanometers. Second, the two bilayers must come into very close contact (within a few angstroms). To achieve this close contact, the two surfaces must become at least partially dehydrated, as the bound surface water normally present causes bilayers to strongly repel. The presence of ions, in particular divalent cations like magnesium and calcium, strongly affects this step. One of the critical roles of calcium in the body is regulating membrane fusion. Third, a destabilization must form at one point between the two bilayers, locally distorting their structures. The exact nature of this distortion is not known. One theory is that a highly curved "stalk" must form between the two bilayers. Proponents of this theory believe that it explains why phosphatidylethanolamine, a highly curved lipid, promotes fusion. Finally, in the last step of fusion, this point defect grows and the components of the two bilayers mix and diffuse away from the site of contact.

The situation is further complicated when considering fusion ''in vivo'' since biological fusion is almost always regulated by the action of membrane-associated proteins. The first of these proteins to be studied were the viral fusion proteins, which allow an enveloped

The situation is further complicated when considering fusion ''in vivo'' since biological fusion is almost always regulated by the action of membrane-associated proteins. The first of these proteins to be studied were the viral fusion proteins, which allow an enveloped virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

to insert its genetic material into the host cell (enveloped viruses are those surrounded by a lipid bilayer; some others have only a protein coat). Eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

cells also use fusion proteins, the best-studied of which are the SNAREs. SNARE proteins are used to direct all vesicular intracellular trafficking. Despite years of study, much is still unknown about the function of this protein class. In fact, there is still an active debate regarding whether SNAREs are linked to early docking or participate later in the fusion process by facilitating hemifusion.

In studies of molecular and cellular biology it is often desirable to artificially induce fusion. The addition of polyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG; ) is a polyether compound derived from petroleum with many applications, from industrial manufacturing to medicine. PEG is also known as polyethylene oxide (PEO) or polyoxyethylene (POE), depending on its molecular wei ...

(PEG) causes fusion without significant aggregation or biochemical disruption. This procedure is now used extensively, for example by fusing B-cells with myeloma cells. The resulting " hybridoma" from this combination expresses a desired antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

as determined by the B-cell involved, but is immortalized due to the melanoma component. Fusion can also be artificially induced through electroporation in a process known as electrofusion. It is believed that this phenomenon results from the energetically active edges formed during electroporation, which can act as the local defect point to nucleate stalk growth between two bilayers.

Model systems

Lipid bilayers can be created artificially in the lab to allow researchers to perform experiments that cannot be done with natural bilayers. They can also be used in the field ofSynthetic Biology

Synthetic biology (SynBio) is a multidisciplinary field of science that focuses on living systems and organisms. It applies engineering principles to develop new biological parts, devices, and systems or to redesign existing systems found in nat ...

, to define the boundaries of artificial cells. These synthetic systems are called model lipid bilayers. There are many different types of model bilayers, each having experimental advantages and disadvantages. They can be made with either synthetic or natural lipids. Among the most common model systems are:

* Black lipid membranes (BLM)

* Supported lipid bilayers (SLB)

* Vesicles

* Droplet Interface Bilayers (DIBs)

Commercial applications

To date, the most successful commercial application of lipid bilayers has been the use of liposomes for drug delivery, especially for cancer treatment. (Note- the term "liposome" is in essence synonymous with " vesicle" except that vesicle is a general term for the structure whereas liposome refers to only artificial not natural vesicles) The basic idea of liposomal drug delivery is that the drug is encapsulated in solution inside the liposome then injected into the patient. These drug-loaded liposomes travel through the system until they bind at the target site and rupture, releasing the drug. In theory, liposomes should make an ideal drug delivery system since they can isolate nearly any hydrophilic drug, can be grafted with molecules to target specific tissues and can be relatively non-toxic since the body possesses biochemical pathways for degrading lipids. The first generation of drug delivery liposomes had a simple lipid composition and suffered from several limitations. Circulation in the bloodstream was extremely limited due to both renal clearing andphagocytosis

Phagocytosis () is the process by which a cell (biology), cell uses its plasma membrane to engulf a large particle (≥ 0.5 μm), giving rise to an internal compartment called the phagosome. It is one type of endocytosis. A cell that performs ph ...

. Refinement of the lipid composition to tune fluidity, surface charge density, and surface hydration resulted in vesicles that adsorb fewer proteins from serum and thus are less readily recognized by the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

. The most significant advance in this area was the grafting of polyethylene glycol

Polyethylene glycol (PEG; ) is a polyether compound derived from petroleum with many applications, from industrial manufacturing to medicine. PEG is also known as polyethylene oxide (PEO) or polyoxyethylene (POE), depending on its molecular wei ...

(PEG) onto the liposome surface to produce "stealth" vesicles, which circulate over long times without immune or renal clearing.

The first stealth liposomes were passively targeted at tumor

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

tissues. Because tumors induce rapid and uncontrolled angiogenesis they are especially "leaky" and allow liposomes to exit the bloodstream at a much higher rate than normal tissue would. More recently work has been undertaken to graft antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

or other molecular markers onto the liposome surface in the hope of actively binding them to a specific cell or tissue type. Some examples of this approach are already in clinical trials.

Another potential application of lipid bilayers is the field of biosensors. Since the lipid bilayer is the barrier between the interior and exterior of the cell, it is also the site of extensive signal transduction. Researchers over the years have tried to harness this potential to develop a bilayer-based device for clinical diagnosis or bioterrorism detection. Progress has been slow in this area and, although a few companies have developed automated lipid-based detection systems, they are still targeted at the research community. These include Biacore (now GE Healthcare Life Sciences), which offers a disposable chip for utilizing lipid bilayers in studies of binding kineticsBiacore Inc. Retrieved Feb 12, 2009. and Nanion Inc., which has developed an Planar patch clamp, automated patch clamping system. A supported lipid bilayer (SLB) as described above has achieved commercial success as a screening technique to measure the permeability of drugs. This parallel artificial membrane permeability assay ( PAMPA) technique measures the permeability across specifically formulated lipid cocktail(s) found to be highly correlated with Caco-2 cultures, the

gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

, blood–brain barrier

The blood–brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective semipermeable membrane, semipermeable border of endothelium, endothelial cells that regulates the transfer of solutes and chemicals between the circulatory system and the central nervous system ...

and skin.

History

By the early twentieth century scientists had come to believe that cells are surrounded by a thin oil-like barrier, but the structural nature of this membrane was not known. Two experiments in 1925 laid the groundwork to fill in this gap. By measuring thecapacitance

Capacitance is the ability of an object to store electric charge. It is measured by the change in charge in response to a difference in electric potential, expressed as the ratio of those quantities. Commonly recognized are two closely related ...

of erythrocyte solutions, Hugo Fricke determined that the cell membrane was 3.3 nm thick.

Although the results of this experiment were accurate, Fricke misinterpreted the data to mean that the cell membrane is a single molecular layer. Prof. Dr. Evert Gorter (1881–1954) and F. Grendel of Leiden University approached the problem from a different perspective, spreading the erythrocyte lipids as a monolayer on a Langmuir–Blodgett trough. When they compared the area of the monolayer to the surface area of the cells, they found a ratio of two to one. Later analyses showed several errors and incorrect assumptions with this experiment but, serendipitously, these errors canceled out and from this flawed data Gorter and Grendel drew the correct conclusion- that the cell membrane is a lipid bilayer.

This theory was confirmed through the use of electron microscopy in the late 1950s. Although he did not publish the first electron microscopy study of lipid bilayers J. David Robertson was the first to assert that the two dark electron-dense bands were the headgroups and associated proteins of two apposed lipid monolayers. In this body of work, Robertson put forward the concept of the "unit membrane." This was the first time the bilayer structure had been universally assigned to all cell membranes as well as organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

membranes.

Around the same time, the development of model membranes confirmed that the lipid bilayer is a stable structure that can exist independent of proteins. By "painting" a solution of lipid in organic solvent across an aperture, Mueller and Rudin were able to create an artificial bilayer and determine that this exhibited lateral fluidity, high electrical resistance and self-healing in response to puncture, all of which are properties of a natural cell membrane. A few years later, Alec Bangham showed that bilayers, in the form of lipid vesicles, could also be formed simply by exposing a dried lipid sample to water. This demonstrated that lipid bilayers form spontaneously via self assembly and do not require a patterned support structure. In 1977, a totally synthetic bilayer membrane was prepared by Kunitake and Okahata, from a single organic compound, didodecyldimethylammonium bromide. This showed that the bilayer membrane was assembled by the intermolecular force

An intermolecular force (IMF; also secondary force) is the force that mediates interaction between molecules, including the electromagnetic forces of attraction

or repulsion which act between atoms and other types of neighbouring particles (e.g. ...

s.

See also

*Surfactant

Surfactants are chemical compounds that decrease the surface tension or interfacial tension between two liquids, a liquid and a gas, or a liquid and a solid. The word ''surfactant'' is a Blend word, blend of "surface-active agent",

coined in ...

* Membrane biophysics

* Lipid polymorphism

* Lipidomics

References

External links

LIPIDAT

An extensive database of lipid physical properties

Simulations and publication links related to the cross sectional structure of lipid bilayers. {{DEFAULTSORT:Lipid Bilayer Biological matter Membrane biology