Peloneustes on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Peloneustes'' (meaning ) is a

The

The  Naturalist

Naturalist  The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist

The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', '' P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a ''

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', '' P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a '' In 1998, palaeontologist Frank Robin O'Keefe proposed that a pliosaurid specimen from the Lower Jurassic

In 1998, palaeontologist Frank Robin O'Keefe proposed that a pliosaurid specimen from the Lower Jurassic

''Peloneustes'' is a small- to medium-sized member of Pliosauridae. NHMUK R3318, the mounted skeleton in the Natural History Museum in London, is long, while the mounted skeleton in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen measures in length. Plesiosaurs typically can be described as being of the small-headed, long-necked "plesiosauromorph" morphotype or the large-headed, short-necked "pliosauromorph" morphotype. ''Peloneustes'' is of the latter morphotype, with its skull making up a little less than a fifth of the animal's total length. ''Peloneustes'', like all plesiosaurs, had a short tail, massive torso, and all of its limbs modified into large flippers.

''Peloneustes'' is a small- to medium-sized member of Pliosauridae. NHMUK R3318, the mounted skeleton in the Natural History Museum in London, is long, while the mounted skeleton in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen measures in length. Plesiosaurs typically can be described as being of the small-headed, long-necked "plesiosauromorph" morphotype or the large-headed, short-necked "pliosauromorph" morphotype. ''Peloneustes'' is of the latter morphotype, with its skull making up a little less than a fifth of the animal's total length. ''Peloneustes'', like all plesiosaurs, had a short tail, massive torso, and all of its limbs modified into large flippers.

While the holotype of ''Peloneustes'' lacks the rear portion of its cranium, many additional well-preserved specimens, including one that has not been crushed from top to bottom, have been assigned to this genus. These crania vary in size, measuring in length. The cranium of ''Peloneustes'' is elongated, and slopes upwards towards its back end. Viewed from above, the cranium is shaped like an

While the holotype of ''Peloneustes'' lacks the rear portion of its cranium, many additional well-preserved specimens, including one that has not been crushed from top to bottom, have been assigned to this genus. These crania vary in size, measuring in length. The cranium of ''Peloneustes'' is elongated, and slopes upwards towards its back end. Viewed from above, the cranium is shaped like an  Characteristically, the

Characteristically, the  The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved

The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for  Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like ''Peloneustes'' are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in ''Peloneustes'' as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like ''Peloneustes'' are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in ''Peloneustes'' as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.

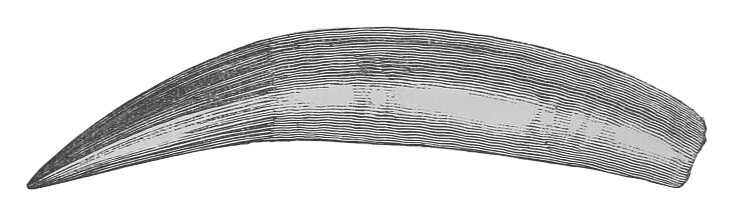

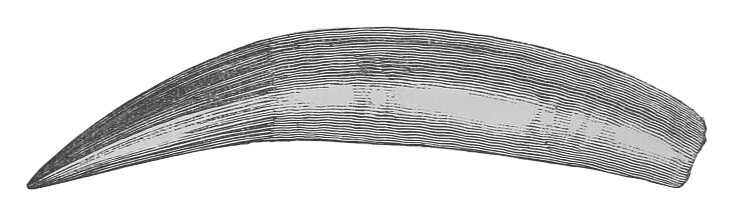

The numerous teeth of ''Peloneustes'' rarely are broken, but often show signs of wear at their tips. Their sharp points, slightly curved, gracile shape, and prominent spacing indicate that they were built for piercing. The slender, elongated snout is similar in shape to that of a dolphin. Both the snout and tooth morphologies led Noè to suggest that ''Peloneustes'' was a

The numerous teeth of ''Peloneustes'' rarely are broken, but often show signs of wear at their tips. Their sharp points, slightly curved, gracile shape, and prominent spacing indicate that they were built for piercing. The slender, elongated snout is similar in shape to that of a dolphin. Both the snout and tooth morphologies led Noè to suggest that ''Peloneustes'' was a

''Peloneustes'' is known from the Peterborough Member (formerly known as the Lower Oxford Clay) of the Oxford Clay Formation. While ''Peloneustes'' has been listed as coming from the Oxfordian stage (spanning from about 164 to 157 million years ago) of the Upper Jurassic, the Peterborough Member actually dates to the

''Peloneustes'' is known from the Peterborough Member (formerly known as the Lower Oxford Clay) of the Oxford Clay Formation. While ''Peloneustes'' has been listed as coming from the Oxfordian stage (spanning from about 164 to 157 million years ago) of the Upper Jurassic, the Peterborough Member actually dates to the  The surrounding land would have had a

The surrounding land would have had a

Plesiosaurs are common in the Peterborough Member, and besides pliosaurids, are represented by cryptoclidids, including ''Cryptoclidus'', ''

Plesiosaurs are common in the Peterborough Member, and besides pliosaurids, are represented by cryptoclidids, including ''Cryptoclidus'', '' More pliosaurid species are known from the Peterborough Member than any other assemblage. Besides ''Peloneustes'', these pliosaurids include ''Liopleurodon ferox'', ''Simolestes vorax'', ''"Pliosaurus" andrewsi'', '' Marmornectes candrewi'', '' Eardasaurus powelli'', and, potentially, '' Pachycostasaurus dawni''. However, there is considerable variation in the anatomy of these species, indicating that they fed on different prey, thereby avoiding competition (

More pliosaurid species are known from the Peterborough Member than any other assemblage. Besides ''Peloneustes'', these pliosaurids include ''Liopleurodon ferox'', ''Simolestes vorax'', ''"Pliosaurus" andrewsi'', '' Marmornectes candrewi'', '' Eardasaurus powelli'', and, potentially, '' Pachycostasaurus dawni''. However, there is considerable variation in the anatomy of these species, indicating that they fed on different prey, thereby avoiding competition (

genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

of pliosaurid plesiosaur

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

from the Middle Jurassic

The Middle Jurassic is the second Epoch (geology), epoch of the Jurassic Period (geology), Period. It lasted from about 174.1 to 161.5 million years ago. Fossils of land-dwelling animals, such as dinosaurs, from the Middle Jurassic are relativel ...

of England. Its remains are known from the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation, which is Callovian

In the geologic timescale, the Callovian is an age and stage in the Middle Jurassic, lasting between 165.3 ± 1.1 Ma (million years ago) and 161.5 ± 1.0 Ma. It is the last stage of the Middle Jurassic, following the Bathonian and preceding the ...

in age. It was originally described as a species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable by ...

'' by palaeontologist Harry Govier Seeley

Harry Govier Seeley (18 February 1839 – 8 January 1909) was a British paleontologist.

Early life

Seeley was born in London on 18 February 1839, the second son of Richard Hovill Seeley, a goldsmith, and his second wife Mary Govier. When his fa ...

in 1869, before being given its own genus by naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

in 1889. While many species have been assigned to ''Peloneustes'', ''P. philarchus'' is currently the only one still considered valid, with the others moved to different genera, considered ''nomina dubia

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

'', or synonymised with ''P. philarchus''. Some of the material formerly assigned to ''P. evansi'' has since been reassigned to "''Pliosaurus''" ''andrewsi''. ''Peloneustes'' is known from many specimens, including some very complete material.

With a total length of , ''Peloneustes'' is not a large pliosaurid. It had a large, triangular skull, which occupied about a fifth of its body length. The front of the skull is elongated into a narrow rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

(snout). The mandibular symphysis

A symphysis (, : symphyses) is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is a type of cartilaginous joint, specifically a secondary cartilaginous joint.

# A symphysis is an amphiarthrosis, a slightly movable joint.

# A growing together o ...

, where the front ends of each side of the mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

(lower jaw) fuse, is elongated in ''Peloneustes'', and helped strengthen the jaw. An elevated ridge is located between the tooth rows on the mandibular symphysis. The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' are conical and have circular cross-sections, bearing vertical ridges on all sides. The front teeth are larger than the back teeth. With only 19 to 21 cervical (neck) vertebrae, ''Peloneustes'' had a short neck for a plesiosaur. The limbs of ''Peloneustes'' were modified into flippers, with the back pair larger than the front.

''Peloneustes'' has been interpreted as both a close relative of ''Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent ...

'' or as a more basal (early-diverging) pliosaurid within Thalassophonea

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages). The family is more inclusive than the archetypal short-necked large headed species that are placed in ...

, with the latter interpretation finding more support. Like other plesiosaurs, ''Peloneustes'' was well-adapted to aquatic life, using its flippers for a method of swimming known as subaqueous flight. Pliosaurid skulls were reinforced to better withstand the stresses of feeding. The long, narrow snout of ''Peloneustes'' could have been swung quickly through the water to catch fish, which it pierced with its numerous sharp teeth. ''Peloneustes'' would have inhabited an epicontinental (inland) sea that was around deep. It shared its habitat with a variety of other animals, including invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, fish, thalattosuchians, ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

s, and other plesiosaurs. At least five other pliosaurids are known from the Peterborough Member, but they were quite varied in anatomy, indicating that they would have eaten different food sources, thereby avoiding competition.

History of research

strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

of the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation have long been mined for brickmaking

A brick is a type of construction material used to build walls, pavements and other elements in masonry construction. Properly, the term ''brick'' denotes a unit primarily composed of clay. But is now also used informally to denote building un ...

. Ever since the late 19th century, when these operations began, the fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserve ...

s of many marine animals have been excavated from the rocks. Among these was the specimen which would become the holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

of ''Peloneustes philarchus'', discovered by geologist Henry Porter in a clay pit

A clay pit is a quarry or Mining, mine for the extraction of clay, which is generally used for manufacturing pottery, bricks or Portland cement. Quarries where clay is mined to make bricks are sometimes called brick pits.

A brickyard or brickwor ...

close to Peterborough

Peterborough ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in the City of Peterborough district in the Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county of Cambridgeshire, England. The city is north of London, on the River Nene. A ...

, England. The specimen includes a mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

, the front part of the upper jaw, various vertebrae

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

from throughout the body, elements from the shoulder girdle

The shoulder girdle or pectoral girdle is the set of bones in the appendicular skeleton which connects to the arm on each side. In humans, it consists of the clavicle and scapula; in those species with three bones in the shoulder, it consists o ...

and pelvis

The pelvis (: pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of an Anatomy, anatomical Trunk (anatomy), trunk, between the human abdomen, abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also c ...

, humeri

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of ...

(upper arm bones), femora

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The top of the femur fits in ...

(upper leg bones), and various other limb bones. In 1866, geologist Adam Sedgwick

Adam Sedgwick FRS (; 22 March 1785 – 27 January 1873) was a British geologist and Anglican priest, one of the founders of modern geology. He proposed the Cambrian and Devonian period of the geological timescale. Based on work which he did ...

purchased the specimen for the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

's Woodwardian Museum

The Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, is the geology museum of the University of Cambridge. It is part of the Department of Earth Sciences and is located on the university's Downing Site in Downing Street, central Cambridge, England. The Sedg ...

(now the Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Cambridge), with the specimen being catalogued as CAMSM J.46913 and stored in the university's lecture room within cabinet D. Palaeontologist Harry Govier Seeley

Harry Govier Seeley (18 February 1839 – 8 January 1909) was a British paleontologist.

Early life

Seeley was born in London on 18 February 1839, the second son of Richard Hovill Seeley, a goldsmith, and his second wife Mary Govier. When his fa ...

described the specimen as a new species of the preexisting genus ''Plesiosaurus'', ''Plesiosaurus

''Plesiosaurus'' (Greek: ' ('), near to + ' ('), lizard) is a genus of extinct, large marine sauropterygian reptile that lived during the Early Jurassic. It is known by nearly complete skeletons from the Lias of England. It is distinguishable by ...

philarchus'', in 1869. The specific name means , possibly due to its large, powerful skull. Seeley did not describe this specimen in detail, mainly just giving a list of the known material. While later publications would further describe these remains, CAMSM J.46913 remained poorly described.

Alfred Leeds and his brother Charles Leeds had been collecting fossils from the Oxford Clay since around 1867, encouraged by geologist John Phillips of the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, assembling what became known as the Leeds Collection. While Charles eventually left, Alfred, who collected the majority of the specimens, continued to gather fossils until 1917. Eventually, after a visit by Henry Woodward of the British Museum of Natural History

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum (Lo ...

(now the Natural History Museum in London) to Leeds' collection in Eyebury in 1885, the museum bought around of fossils in 1890. This brought Leeds' collection to wider renown, and he would later sell specimens to museums throughout Europe, and even some in the United States. The carefully prepared material was usually in good condition, although it quite frequently had been crushed and broken by geological processes. Skulls were particularly vulnerable to this.

Naturalist

Naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

was informed of a plesiosaur skeleton in the British Museum of Natural History by geologist George Charles Crick, who worked there. The specimen, catalogued under NHMUK PV R1253, had been discovered in the Oxford Clay Formation in Green End, Kempston, near Bedford

Bedford is a market town in Bedfordshire, England. At the 2011 Census, the population was 106,940. Bedford is the county town of Bedfordshire and seat of the Borough of Bedford local government district.

Bedford was founded at a ford (crossin ...

. While Lydekker speculated that the skeleton was once complete, it was damaged during excavation. The limb girdles had been heavily fragmented when the specimen arrived at the museum, but a worker named Lingard in the Geology Department managed to restore much of them. In addition to the limb girdles, the specimen also consists of a partial mandible, teeth, multiple vertebrae (although none from the neck), and much of the limbs. Lydekker identified this specimen as an individual of ''Plesiosaurus philarchus'' and published a description of it in 1889. After studying this and other specimens in the Leeds Collection, he concluded that plesiosaurs

The Plesiosauria or plesiosaurs are an Order (biology), order or clade of extinct Mesozoic marine reptiles, belonging to the Sauropterygia.

Plesiosaurs first appeared in the latest Triassic Period (geology), Period, possibly in the Rhaetian st ...

with shortened necks and large heads could not be classified as species of ''Plesiosaurus'', meaning that ''"P." philarchus'' belonged to a different genus. He initially assigned it to '' Thaumatosaurus'' in 1888, but later decided that it was distinct enough to warrant its own genus, which he named ''Peloneustes'' in his 1889 publication. The name ''Peloneustes'' comes from the Greek words , meaning or , in reference to the Oxford Clay Formation, and , meaning . Seeley, however, lumped ''Peloneustes'' into ''Pliosaurus

''Pliosaurus'' (meaning 'more lizard') is an extinct genus of thalassophonean pliosaurid known from the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages) of Europe and South America. This genus has contained many species in the past but recent ...

'' in 1892, claiming that the two were insufficiently different to warrant separate genera. Seeley and Lydekker could not agree on which genus to classify ''P. philarchus'' in, representing part of a feud between the two scientists. However, ''Peloneustes'' has since become the accepted name.

The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist

The Leeds Collection contained multiple ''Peloneustes'' specimens. In 1895, palaeontologist Charles William Andrews

Charles William Andrews (30 October 1866 – 25 May 1924) F.R.S., was a British palaeontologist whose career as a vertebrate paleontologist, both as a curator and in the field, was spent in the services of the British Museum, Department of Ge ...

described the anatomy of the skull of ''Peloneustes'' based on four partial skulls in the Leeds Collection. In 1907, geologist Frédéric Jaccard published a description of two ''Peloneustes'' specimens from the Oxford Clay near Peterborough, housed in the Musée Paléontologique de Lausanne, Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. The more complete of the two specimens includes a complete skull preserving both jaws; multiple isolated teeth; 13 cervical (neck), 5 pectoral (shoulder), and 7 caudal (tail) vertebrae; ribs; both scapulae, a coracoid

A coracoid is a paired bone which is part of the shoulder assembly in all vertebrates except therian mammals (marsupials and placentals). In therian mammals (including humans), a coracoid process is present as part of the scapula, but this is n ...

; a partial interclavicale; a complete pelvis save for an ischium

The ischium (; : is ...

; and all four limbs, which were nearly complete. The other specimen preserved 33 vertebrae and some associated ribs. Since the specimen Lydekker described was in some need of restoration, and missing information was filled in with data from other specimens in his publication, Jaccard found it pertinent to publish a description containing photographs of the more complete specimen in Lausanne to better illustrate the anatomy of ''Peloneustes''.

In 1913, naturalist Hermann Linder described multiple specimens of ''Peloneustes philarchus'' housed in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (; ), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

The University of Tübingen is one of eleven German Excellenc ...

and State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart

The State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart (), abbreviated SMNS, is one of the two state of Baden-Württemberg's natural history museums. Together with the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe (Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karls ...

, Germany. These specimens had also come from the Leeds Collection. Among the specimens he described from the former institution was a nearly complete mounted skeleton, lacking two cervical vertebrae, some caudal vertebrae from the end of the tail, and some distal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position provi ...

phalanges. Only the rear part of the cranium

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

was in good condition, but the mandible was mostly undamaged. Another of the specimens Linder described was a well-preserved skull (GPIT RE/3409), also from the University of Tübingen, preserving a sclerotic ring

The scleral ring or sclerotic ring is a hardened ring of plates, often derived from bone, that is found in the eyes of many animals in several groups of vertebrates. Some species of mammals, amphibians, and crocodilians lack scleral rings. The rin ...

(the set of small bones that support the eye), only the fourth time these bones had been reported in a plesiosaur.

Andrews later described the marine reptile

Marine reptiles are reptiles which have become secondarily adapted for an aquatic or semiaquatic life in a marine environment. Only about 100 of the 12,000 extant reptile species and subspecies are classed as marine reptiles, including mari ...

specimens of the Leeds Collection that were in the British Museum of Natural History, publishing two volumes, one in 1910 and the other in 1913. The anatomy of the ''Peloneustes'' specimens was described in the second volume, based primarily on the well-preserved skulls NHMUK R2679 and NHMUK R3808 and NHMUK R3318, an almost complete skeleton. NHMUK R3318 was so well preserved that it could be rearticulated and mounted, although the missing parts of the pelvis and limbs had to be filled in. The mounted skeleton was put on display in the museum's Gallery of Fossil Reptiles. Andrews had described this mount in 1910, remarking that it was the first skeletal mount of a pliosaurid, thus providing important information about the overall anatomy of the group.

In 1960, palaeontologist Lambert Beverly Tarlo published a review of pliosaurid species that had been reported from the Upper Jurassic

The Late Jurassic is the third epoch of the Jurassic Period, and it spans the geologic time from 161.5 ± 1.0 to 143.1 ± 0.8 million years ago (Ma), which is preserved in Upper Jurassic strata.Owen 1987.

In European lithostratigraphy, the name ...

. Many pliosaurids species had been named based on isolated fragments, creating confusion. Tarlo also found that inaccurate descriptions of the material and palaeontologists ignoring each other's work only made this confusion worse. Of the 36 species he reviewed, he found only nine of them to be valid, including ''Peloneustes philarchus''. In 2011, palaeontologists Hilary Ketchum and Roger Benson described the anatomy of the skull of ''Peloneustes''. Since the previous anatomical studies of Andrews and Linder, more specimens had been found, including NHMUK R4058, a skull preserved in three dimensions, providing a better idea of the skull's shape.

Formerly assigned species and specimens

Many further species have been assigned to ''Peloneustes'' throughout itstaxonomic

280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme of classes (a taxonomy) and the allocation ...

history, but these have all since been reassigned to different genera or considered invalid. In the same publication in which he named ''P. philarchus'', Seeley also named another species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of ''Plesiosaurus'', ''P. sterrodeirus'' based on seven specimens in the Woodwardian Museum consisting of cranial and vertebral material. When Lydekker erected the genus ''Peloneustes'' for ''P. philarchus'', he also reclassified ''"Plesiosaurus" sterrodeirus'' and ''" Pleiosaurus" aequalis'' (a species named by John Phillips in 1871) as members of this genus. In his 1960 review of pliosaurid taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

, Tarlo considered ''P. aequalis'' to be invalid, since it was based on propodials (upper limb bones), which cannot be used to differentiate different pliosaurid species. He considered ''Peloneustes sterrodeirus'' to instead belong to ''Pliosaurus'', possibly within ''P. brachydeirus''.

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', '' P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a ''

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was ''Pliosaurus evansi'', based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum. These consisted of cervical and dorsal (back) vertebrae, ribs, and a coracoid. Due to it being a smaller species of ''Pliosaurus'' and its similarity to ''Peloneustes philarchus'', Lydekker reassigned it to ''Peloneustes'' in 1890, noting that it was larger than ''Peloneustes philarchus''. He also thought that a large mandible and paddle attributed to ''Pleiosaurus ?grandis'' by Phillips in 1871 belonged to this species instead. In 1913, Andrews assigned a partial skeleton of another large pliosaur found by Leeds to ''Peloneustes evansi'', noting that while the mandible and vertebrae were similar to other ''Peloneustes evansi'' specimens, they were quite different from those of ''Peloneustes philarchus''. Consequently, Andrews considered it possible that ''P. evansi'' really belonged to a separate genus that was morphologically intermediate between ''Peloneustes'' and ''Pliosaurus''. In his 1960 review of pliosaurids, Tarlo synonymised ''Peloneustes evansi'' with ''Peloneustes philarchus'' due to their cervical vertebrae being identical (save for a difference in size). He considered the larger specimens of ''Peloneustes evansi'' distinct, and assigned them to a new species of ''Pliosaurus'', '' P. andrewsi'' (although this species is no longer considered to belong in ''Pliosaurus''). Hilary F. Ketchum and Roger B. J. Benson disagreed with this synonymy, and in 2011 considered that since the holotype of ''Peloneustes evansi'' is nondiagnostic (lacking distinguishing features), ''P. evansi'' is a ''nomen dubium

In binomial nomenclature, a ''nomen dubium'' (Latin for "doubtful name", plural ''nomina dubia'') is a scientific name that is of unknown or doubtful application.

Zoology

In case of a ''nomen dubium,'' it may be impossible to determine whether a ...

'' and therefore an indeterminate pliosaurid.

Palaeontologist Ernst Koken described in 1905 another species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. kanzleri'', from the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

Wealden Group

The Wealden Group, occasionally also referred to as the Wealden Supergroup, is a group (stratigraphy), group (a sequence of rock strata) in the lithostratigraphy of southern England. The Wealden group consists of wiktionary:paralic, paralic to c ...

of northern Germany. In 1960, Tarlo reidentified this species as an elasmosaurid

Elasmosauridae, often called elasmosaurs or elasmosaurids, is an extinct family of plesiosaurs that lived from the Hauterivian stage of the Early Cretaceous to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period (c. 130 to 66 mya). The taxo ...

. In 1913, Linder created a subspecies of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. philarchus'' var. ''spathyrhynchus'', differentiating it based on its spatulate mandibular symphysis

A symphysis (, : symphyses) is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is a type of cartilaginous joint, specifically a secondary cartilaginous joint.

# A symphysis is an amphiarthrosis, a slightly movable joint.

# A growing together o ...

(where the two sides of the mandible meet and fuse). Tarlo considered it to be a synonym of ''Peloneustes philarchus'' in 1960, and the mandibular symphysis of ''Peloneustes'' is proportionately wider in larger specimens, making this trait more likely to be due to intraspecific variation

Biological specificity is the tendency of a characteristic such as a behavior or a biochemical variation to occur in a particular species.

Biochemist Linus Pauling stated that "Biological specificity is the set of characteristics of living organism ...

(variation within species). Crushing makes accurate measurement of these proportions difficult. In 1948, palaeontologist Nestor Novozhilov

Nestor Ivanovich Novozhilov was a Soviet paleontologist. In 1948, Novozhilov described a pliosaur specimen discovered on the banks of Russia's Volga Riveras a new species, '' Pliosaurus rossicus''. The specimen, while large, was damaged during the ...

named a new species of ''Peloneustes'', ''P. irgisensis'', based on PIN 426, a partial skeleton consisting of a large, incomplete skull, vertebrae, and a partial hind limb, with stomach contents preserved. The specimen was unearthed in the Lower Volga Basin in Russia. In his 1960 review, Tarlo considered this species to be too different from ''Peloneustes philarchus'' to belong to ''Peloneustes'', tentatively placing it in ''Pliosaurus''. He speculated that Novozhilov had incorrectly thought ''Peloneustes'' to be the sole long-snouted pliosaurid, hence the initial assignment. In 1964 Novozhilov erected a new genus, '' Strongylokrotaphus'', for this species, but further studies concurred with Tarlo and reassigned the species to ''Pliosaurus'', possibly a synonym of ''Pliosaurus rossicus''. More recent studies considered the taxon as a ''nomen dubium'' given its currently undiagnostic character, but nevertheless recommend a new description of the holotype. However, this suggestion risks being tainted by the current state of conservation of specimen PIN 426, the skull and notably the mandible having since been seriously damaged by pyrite

The mineral pyrite ( ), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

decay, and the associated elements being noted as lost.

Posidonia Shale

The Posidonia Shale (, also called Schistes Bitumineux in Luxembourg) geologically known as the Sachrang Formation, is an Early Jurassic (Early to Late Toarcian) geological formation in Germany, northern Switzerland, northwestern Austria, souther ...

of Germany might represent a new species of ''Peloneustes''. However, in 2001, he considered it to belong to a separate genus and species, naming it '' Hauffiosaurus zanoni''. Palaeontologists Zulma Gasparini and Manuel A. Iturralde-Vinent assigned a pliosaurid from the Upper Jurassic Jagua Formation of Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

to ''Peloneustes'' sp. in 2006. In 2009, Gasparini redescribed it as '' Gallardosaurus iturraldei''. In 2011, Ketchum and Benson considered ''Peloneustes'' to contain only one species, ''P. philarchus''. They recognised twenty one definite specimens of ''Peloneustes philarchus'', all from the Peterborough Member of the Oxford Clay Formation. They considered some specimens from the Peterborough Member and Marquise

A marquess (; ) is a nobleman of high hereditary rank in various European peerages and in those of some of their former colonies. The German-language equivalent is Markgraf (margrave). A woman with the rank of a marquess or the wife (or wid ...

, France previously assigned to ''Peloneustes'' to belong to different, currently unnamed pliosaurids. In 1972, paleontologist Teresa Maryańska

Teresa Maryańska (1937 – 3 October 2019) was a Polish paleontologist who specialized in Mongolian dinosaurs, particularly pachycephalosaurians and ankylosaurians. She is considered not only as one of Poland's but also one of the world's leadin ...

attributed cranial fragments to ''Peloneustes'' sp. which were discovered in an Oxfordian quarry in Załęcze Wielkie, Poland. In 2011, Ketchum and Benson reidentified this specimen as actually coming from an undetermined marine teleosaurid crocodylomorph

Crocodylomorpha is a group of pseudosuchian archosaurs that includes the crocodilians and their extinct relatives. They were the only members of Pseudosuchia to survive the end-Triassic extinction. Extinct crocodylomorphs were considerably mor ...

.

Description

Skull

isosceles triangle

In geometry, an isosceles triangle () is a triangle that has two Edge (geometry), sides of equal length and two angles of equal measure. Sometimes it is specified as having ''exactly'' two sides of equal length, and sometimes as having ''at le ...

, with the back of the cranium broad and the front elongated into a narrow rostrum

Rostrum may refer to:

* Any kind of a platform for a speaker:

**dais

**pulpit

** podium

* Rostrum (anatomy), a beak, or anatomical structure resembling a beak, as in the mouthparts of many sucking insects

* Rostrum (ship), a form of bow on naval ...

. The rearmost part of the cranium has roughly parallel sides, unlike the tapering front regions. The external nares (openings for the nostrils) are small and located about halfway along the length of the cranium. The kidney-shaped eye sockets face forwards and outwards and are located on the back half of the cranium. The sclerotic rings are composed of at least 16 individual elements, an unusually high number for a reptile. The temporal fenestrae

Temporal fenestrae are openings in the temporal region of the skull of some amniotes, behind the orbit (eye socket). These openings have historically been used to track the evolution and affinities of reptiles. Temporal fenestrae are commonly ( ...

(openings in the back of the cranium) are enlarged, elliptical, and located on the cranium's rearmost quarter.

Characteristically, the

Characteristically, the premaxillae

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals has ...

(front upper tooth-bearing bones) of ''Peloneustes'' bear six teeth each, and the diastemata (gaps between teeth) of the upper jaw are narrow. While it has been stated that ''Peloneustes'' had nasals (bones bordering the external nares), well-preserved specimens indicate that this is not the case. The frontals (bones bordering the eye sockets) of ''Peloneustes'' contact both the eye sockets and the external nares, a distinctive trait of ''Peloneustes''. There has been some contention as to whether or not ''Peloneustes'' had lacrimals (bones bordering the lower front edges of the eye sockets), due to poor preservation. However, well preserved specimens indicate that the lacrimals are distinct bones as in other pliosaurids, as opposed to extensions of the jugal

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by species.

Anatomy ...

s (bones bordering the lower rear edges of the eye sockets). The palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sep ...

of ''Peloneustes'' is flat and bears many openings, including the internal nares (the opening of the nasal passage into the mouth). These openings are contacted by palatal bones known as palatines

Palatines () were the citizens and princes of the Palatinates, Holy Roman States that served as capitals for the Holy Roman Emperor. After the fall of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the nationality referred more specifically to residents of the ...

, a configuration used to identify this genus. The parasphenoid

The parasphenoid is a bone which can be found in the cranium of many vertebrates. It is an unpaired dermal bone which lies at the midline of the roof of the mouth. In many reptiles (including birds), it fuses to the endochondral (cartilage-derived ...

(a bone that forms the lower front part of the braincase

In human anatomy, the neurocranium, also known as the braincase, brainpan, brain-pan, or brainbox, is the upper and back part of the skull, which forms a protective case around the brain. In the human skull, the neurocranium includes the calv ...

) bears a long cultriform process (a frontwards projection of the braincase) that is visible when the palate is viewed from below, another distinctive characteristic of ''Peloneustes''. The occiput

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lobes of the ...

(rear part of the cranium) of ''Peloneustes'' is open, bearing large fenestrae.

''Peloneustes'' is known from many mandibles, some of which are well-preserved. The longest of these measures . The mandibular symphysis is elongated, making up about a third of the total mandibular length. Behind the symphysis, the two sides of the mandible diverge before gently curving back inwards near the hind end. Each dentary

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone ...

(the tooth-bearing bone in the mandible) has between 36 and 44 teeth, 13 to 15 of which are located on the symphysis. The second to seventh tooth sockets (tooth sockets) are larger than those located further back, and the symphysis is the widest around the fifth and sixth. In addition to the characteristics of its mandibular teeth, ''Peloneustes'' can also be identified by its coronoids (upper inner mandibular bones), which contribute to the mandibular symphysis. Between the tooth rows, the mandibular symphysis bears an elevated ridge where the dentaries meet. This is a unique feature of ''Peloneustes'', not seen in any other plesiosaurs. The mandibular glenoid (socket of the jaw joint) is broad, kidney-shaped, and angled upwards and inwards.

The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved

The teeth of ''Peloneustes'' have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age. The teeth have the shape of recurved cone

In geometry, a cone is a three-dimensional figure that tapers smoothly from a flat base (typically a circle) to a point not contained in the base, called the '' apex'' or '' vertex''.

A cone is formed by a set of line segments, half-lines ...

s. The enamel of the crowns bears regularly-spaced vertical ridges of varying length on all sides. These ridges are more concentrated on the concave edge of the teeth. Most of the ridges extend to one half to two-thirds of the total crown height, with few actually reaching the tooth's apex. The dentition of ''Peloneustes'' is heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

Human dentition is heterodont and diphyodont as an example.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals wher ...

, that is, it has teeth of different shapes. The larger teeth are caniniform

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dogteeth, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or fangs, are the relatively long, pointed tooth, teeth. In the context of the upper jaw, they are also known as ''fangs''. They can appear mo ...

and located at the front of the jaws, while the smaller teeth are more sharply recurved, stouter, and located further back.

Postcranial skeleton

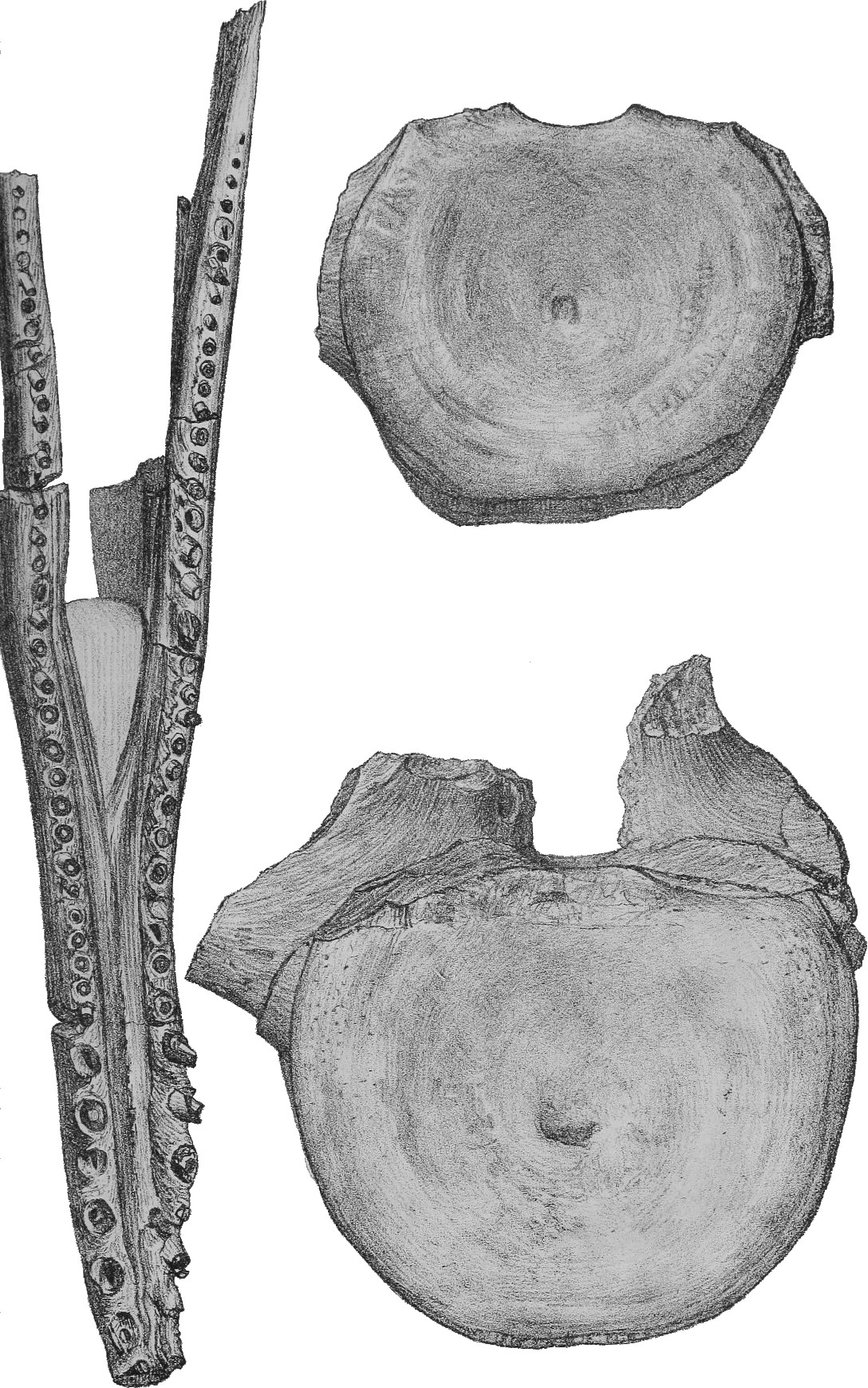

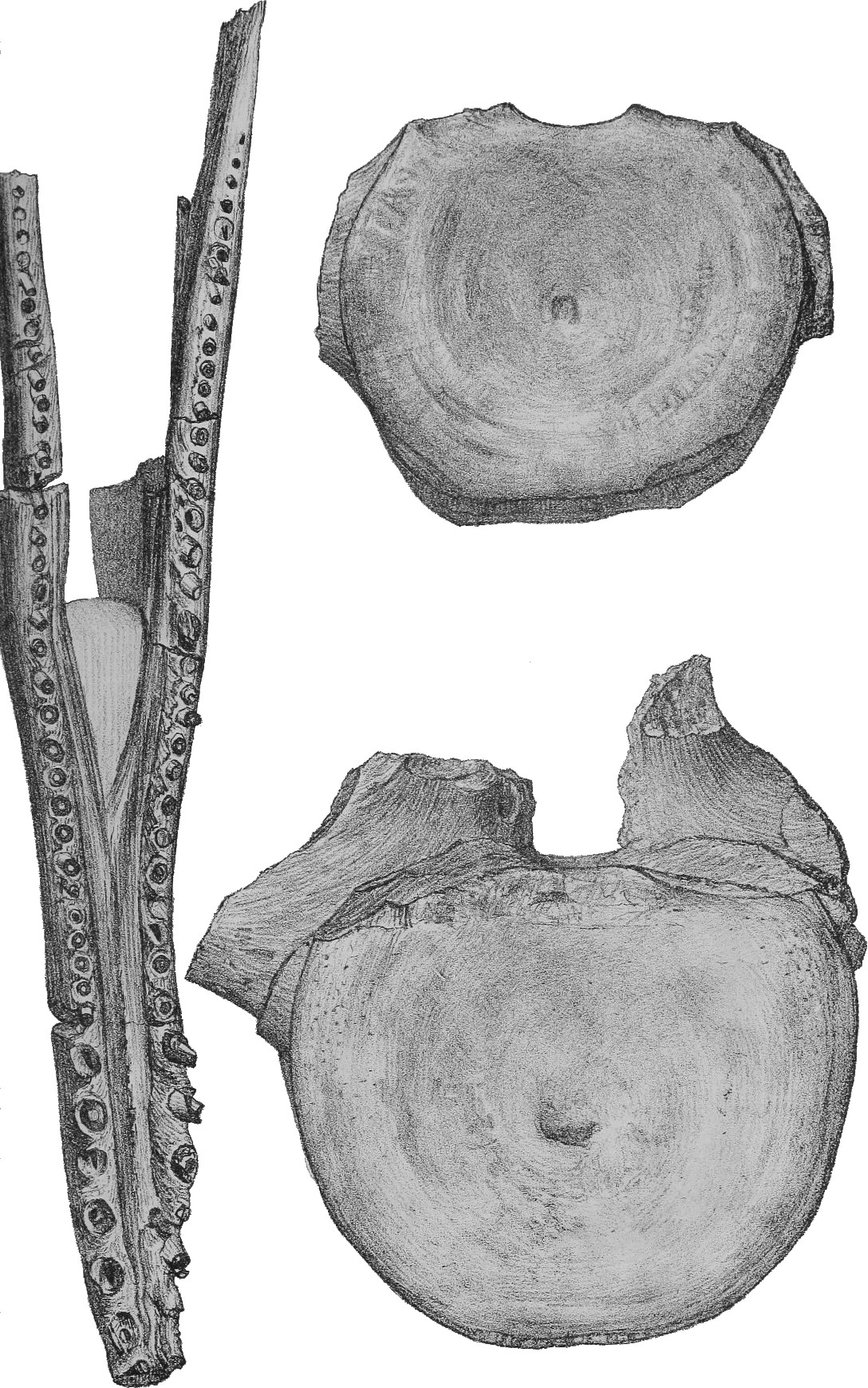

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

In 1913, Andrews reported that ''Peloneustes'' had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20 dorsal

Dorsal (from Latin ''dorsum'' ‘back’) may refer to:

* Dorsal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location referring to the back or upper side of an organism or parts of an organism

* Dorsal, positioned on top of an aircraft's fuselage

The fus ...

vertebrae, with the exact number of sacral (hip) and caudal vertebrae unknown, based on specimens in the Leeds Collection. However, in the same year, Linder reported 19 cervical, 5 pectoral, 20 dorsal, 2 sacral, and at least 17 caudal vertebrae in ''Peloneustes'', based on a specimen in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen. The first two cervical vertebrae, the atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

and axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

, are fused in adults, but in juveniles they are present as several unfused elements. The intercentrum (part of the vertebral body) of the axis is roughly rectangular, extending beneath the centrum (vertebral body) of the atlas. The cervical vertebrae bear tall neural spine

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

s that are compressed from side to side. The cervical centra are about half as long as wide. They bear strongly concave articular surfaces, with a prominent rim around the lower edge in the vertebrae located towards the front of the series. Each cervical centrum has a strong keel along the midline of its underside. Most of the cervical rib Cervical ribs are the ribs of the neck in many tetrapods. In most mammals, including humans, cervical ribs are not normally present as separate structures. They can, however, occur as a pathology. In humans, pathological cervical ribs are usually no ...

s bear two heads that are separated by a notch.

The pectoral vertebrae bear articulations for their respective ribs partially on both their centra and neural arches. Following these vertebrae are the dorsal vertebrae, which are more elongated than the cervical vertebrae and have shorter neural spines. The sacral and caudal vertebrae both have less elongated centra that are wider than tall. Many of the ribs from the hip and the base of the tail bear enlarged outer ends that seem to articulate with each other. Andrews hypothesised in 1913 that this configuration would have stiffened the tail, possibly to support the large hind limbs. The terminal (last) caudal vertebrae sharply decrease in size and would have supported proportionately larger chevrons than the caudal vertebrae located further forwards. In 1913, Andrews speculated that this morphology may have been present to support a small tail fin-like structure. Other plesiosaurs have also been hypothesised to have tail fins, with impressions of such a structure possibly known in one species.

The shoulder girdle of ''Peloneustes'' was large, although not as heavily built as in some other plesiosaurs. The coracoids are the largest bones in the shoulder girdle, and are plate-like in form. The shoulder joint is formed by both the scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

(shoulder balde) and the coracoid, with the two bones forming a 70° angle with each other. The scapulae are typical in form for a pliosaurid and triradiate, bearing three prominent projections, or rami. The dorsal (upper) ramus is directed outwards, upwards, and backwards. The underside of each scapula bears a ridge directed towards the front edge of its ventral (lower) ramus. The ventral rami of the two scapulae were separated from each other by a triangular bone known as the interclavicle

An interclavicle is a bone which, in most tetrapods, is located between the clavicles. Therian mammals ( marsupials and placentals) are the only tetrapods which never have an interclavicle, although some members of other groups also lack one. In ...

. As seen in other pliosaurs, the pelvis of ''Peloneustes'' bears large and flat ischia and pubic bones

In vertebrates, the pubis or pubic bone () forms the lower and anterior part of each side of the hip bone. The pubis is the most forward-facing (ventral and anterior) of the three bones that make up the hip bone. The left and right pubic bones ar ...

. The third pelvic bone, the ilium, is smaller and elongated, articulating with the ischium. The upper end of the ilium shows a large amount of variation within ''P. philarchus'', with two forms known, one with a rounded upper edge, the other with a flat upper edge and more angular shape.

The hind limbs of ''Peloneustes'' are longer than its forelimbs, with the femur being longer than the humerus, although the humerus is the more robust of the two elements. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

(one of the lower forelimb bones) is approximately as wide as it is long, unlike the ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

(the other lower forelimb bone), which is wider than long. The radius is the larger of these two elements. The tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

is larger than the fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

(lower hindlimb bones) and longer than wide, while the fibula is wider than long in some specimens. The metacarpal

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones ( wrist bones), which articulate ...

s, metatarsal

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

s, and the proximal manual phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

(some of the bones making up the outer part of the paddle) are flattened. Most of the phalanges in both limbs have rounded cross-sections, and all of them have prominent constrictions in their middles. The number of phalanges in each digit is unknown in both the fore- and hind limbs.

Classification

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for

Seeley initially described ''Peloneustes'' as a species of ''Plesiosaurus'', a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for families

Family (from ) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictability, structure, and safety as ...

). In 1874, Seeley named a new family of plesiosaurs, Pliosauridae, to contain forms similar to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1890, Lydekker placed ''Peloneustes'' in this family, to which it has been consistently assigned since. Exactly how pliosaurids are related to other plesiosaurs is uncertain. In 1940, palaeontologist Theodore E. White considered pliosaurids to be close relatives of Elasmosauridae

Elasmosauridae, often called elasmosaurs or elasmosaurids, is an extinct family of plesiosaurs that lived from the Hauterivian stage of the Early Cretaceous to the Maastrichtian stage of the Late Cretaceous period (c. 130 to 66 mya). The taxo ...

based on shoulder anatomy. Palaeontologist Samuel P. Welles, however, thought that pliosaurids were more similar to Polycotylidae

Polycotylidae is a family of plesiosaurs from the Cretaceous, a sister group to Leptocleididae. They are known as false pliosaurs. Polycotylids first appeared during the Albian stage of the Early Cretaceous, before becoming abundant and widesprea ...

, as they both had large skulls and short necks, among other characteristics. He grouped these two families into the superfamily Pliosauroidea

Pliosauroidea is an extinct clade of plesiosaurs, known from the earliest Jurassic to early Late Cretaceous. They are best known for the subclade Thalassophonea, which contained crocodile-like short-necked forms with large heads and massive toot ...

, with other plesiosaurs forming the superfamily Plesiosauroidea

Plesiosauroidea (; Greek: 'near, close to' and 'lizard') is an extinct clade of carnivorous marine reptiles. They have the snake-like longest neck to body ratio of any reptile. Plesiosauroids are known from the Jurassic and Cretaceous perio ...

. Another plesiosaur family, Rhomaleosauridae, has since been assigned to Pliosauroidea, while Polycotylidae has been reassigned to Plesiosauroidea. However, in 2012, Benson and colleagues recovered a different topology, with Pliosauridae being more closely related to Plesiosauroidea than Rhomaleosauridae. This pliosaurid-plesiosauroid clade was termed Neoplesiosauria.

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of ''Peloneustes'' is uncertain. In 1889, Lydekker considered ''Peloneustes'' to represent a transitional form between ''Pliosaurus'' and earlier plesiosaurs, although he found it unlikely that ''Peloneustes'' was ancestral to ''Pliosaurus''. In 1960, Tarlo considered ''Peloneustes'' to be a close relative of ''Pliosaurus'', since both taxa had elongated mandibular symphyses. In 2001, O'Keefe recovered it as a basal (early-diverging) member of this family, outside of a group including ''Liopleurodon

''Liopleurodon'' (; meaning 'smooth-sided teeth') is an extinct genus of carnivorous pliosaurid pliosaurs that lived from the Callovian stage of the Middle Jurassic to the Kimmeridgian stage of the Late Jurassic period (c. 166 to 155 mya). T ...

'', ''Pliosaurus'', and '' Brachauchenius''. However, in 2008, palaeontologists Adam S. Smith and Gareth J. Dyke found ''Peloneustes'' to be the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of ''Pliosaurus''. In 2013, Benson and palaeontologist Patrick S. Druckenmiller named a new clade within Pliosauridae, Thalassophonea

Pliosauridae is a family of plesiosaurian marine reptiles from the Latest Triassic to the early Late Cretaceous (Rhaetian to Turonian stages). The family is more inclusive than the archetypal short-necked large headed species that are placed in ...

. This clade included the "classic", short-necked pliosaurids while excluding the earlier, long-necked, more gracile forms. ''Peloneustes'' was found to be the most basal thalassophonean. Subsequent studies have uncovered a similar position for ''Peloneustes''.

The following cladogram

A cladogram (from Greek language, Greek ''clados'' "branch" and ''gramma'' "character") is a diagram used in cladistics to show relations among organisms. A cladogram is not, however, an Phylogenetic tree, evolutionary tree because it does not s ...

follows Ketchum and Benson, 2022.

Palaeobiology

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life. They grew at rates comparable to those of birds and had high metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

s, indicating homeothermy

Homeothermy, homothermy, or homoiothermy () is thermoregulation that maintains a stable internal body temperature regardless of external influence. This internal body temperature is often, though not necessarily, higher than the immediate envir ...

or even endothermy

An endotherm (from Greek ἔνδον ''endon'' "within" and θέρμη ''thermē'' "heat") is an organism that maintains its body at a metabolically favorable temperature, largely by the use of heat released by its internal bodily functions inste ...

. The bony labyrinth

The bony labyrinth (also osseous labyrinth or otic capsule) is the rigid, bony outer wall of the inner ear in the temporal bone. It consists of three parts: the vestibule, semicircular canals, and cochlea. These are cavities hollowed out of the ...

, a hollow within the skull which held a sensory organ associated with balance and orientation, of ''Peloneustes'' and other plesiosaurs is similar in shape to that of sea turtle

Sea turtles (superfamily Chelonioidea), sometimes called marine turtles, are reptiles of the order Testudines and of the suborder Cryptodira. The seven existing species of sea turtles are the flatback, green, hawksbill, leatherback, loggerh ...

s. Palaeontologist James Neenan and colleagues hypothesised in 2017 that this shape probably evolved alongside the flapping motions used by plesiosaurs to swim. ''Peloneustes'' and other short-necked plesiosaurs also had smaller labyrinths than plesiosaurs with longer necks, a pattern also seen in cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s. Additionally, ''Peloneustes'' probably had salt gland

The salt gland is an organ (anatomy), organ for excreting excess salt (chemistry), salts. It is found in the cartilaginous fishes subclass elasmobranchii (sharks, rays, and skates), seabirds, and some reptiles. Salt glands can be found in the r ...

s in its head to cope with excess amount of salt within its body. However, ''Peloneustes'' appears to have been a predator of vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s, which contain less salt than invertebrate

Invertebrates are animals that neither develop nor retain a vertebral column (commonly known as a ''spine'' or ''backbone''), which evolved from the notochord. It is a paraphyletic grouping including all animals excluding the chordata, chordate s ...

s, therefore leading palaeontologist Leslie Noè to suggest in a 2001 dissertation that these glands would not have had to be especially large. ''Peloneustes'', like many other pliosaurs, displayed a reduced level of ossification

Ossification (also called osteogenesis or bone mineralization) in bone remodeling is the process of laying down new bone material by cells named osteoblasts. It is synonymous with bone tissue formation. There are two processes resulting in t ...

of its bones. Palaeontologist Arthur Cruickshank and colleagues in 1966 proposed that this may have helped ''Peloneustes'' maintain its buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is the force exerted by a fluid opposing the weight of a partially or fully immersed object (which may be also be a parcel of fluid). In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of t ...

or improved its manoeuvrability. A 2019 study by palaeontologist Corinna Fleischle and colleagues found that plesiosaurs had enlarged red blood cell

Red blood cells (RBCs), referred to as erythrocytes (, with -''cyte'' translated as 'cell' in modern usage) in academia and medical publishing, also known as red cells, erythroid cells, and rarely haematids, are the most common type of blood cel ...

s, based on the morphology of their vascular canals, which would have aided them while diving.

Plesiosaurs such as ''Peloneustes'' employed a method of swimming known as subaqueous flight, using their flippers as hydrofoil

A hydrofoil is a lifting surface, or foil, that operates in water. They are similar in appearance and purpose to aerofoils used by aeroplanes. Boats that use hydrofoil technology are also simply termed hydrofoils. As a hydrofoil craft gains sp ...

s. Plesiosaurs are unusual among marine reptiles in that they used all four of their limbs, but not movements of the vertebral column, for propulsion. The short tail, while unlikely to have been used to propel the animal, could have helped stabilise or steer the plesiosaur. The front flippers of ''Peloneustes'' have aspect ratio

The aspect ratio of a geometry, geometric shape is the ratio of its sizes in different dimensions. For example, the aspect ratio of a rectangle is the ratio of its longer side to its shorter side—the ratio of width to height, when the rectangl ...

s of 6.36, while the rear flippers have aspect ratios of 8.32. These ratios are similar to those of the wings of modern falcon

Falcons () are birds of prey in the genus ''Falco'', which includes about 40 species. Some small species of falcons with long, narrow wings are called hobbies, and some that hover while hunting are called kestrels. Falcons are widely distrib ...

s. In 2001, O'Keefe proposed that, much like falcons, pliosauromorph plesiosaurs such as ''Peloneustes'' probably were capable of moving quickly and nimbly, albeit inefficiently, to capture prey. Computer modelling by palaeontologist Susana Gutarra and colleagues in 2022 found that due to their large flippers, a plesiosaur would have produced more drag than a comparably-sized cetacean or ichthyosaur

Ichthyosauria is an order of large extinct marine reptiles sometimes referred to as "ichthyosaurs", although the term is also used for wider clades in which the order resides.

Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era; based on fo ...

. However, plesiosaurs counteracted this with their large trunks and body size. Due to the reduction in drag by their shorter, deeper bodies, palaeontologist Judy Massare proposed in 1988 that plesiosaurs could actively search for and pursue their food instead of having to lie in wait for it.

Feeding mechanics

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like ''Peloneustes'' are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in ''Peloneustes'' as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.