Outer Hebridean on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Outer Hebrides ( ) or Western Isles ( , or ), sometimes known as the Long Isle or Long Island (), is an

The islands form an archipelago whose major islands are

The islands form an archipelago whose major islands are

SNH Information and Advisory Note Number 4. Retrieved 1 January 2010. North and South Uist and Lewis, in particular, have landscapes with a high percentage of fresh water and a maze and complexity of loch shapes. Harris has fewer large bodies of water but has innumerable small lochans. Loch Langavat on Lewis is long, and has several large islands in its midst, including

Much of the archipelago is a protected habitat, including both the islands and the surrounding waters. There are 53

Much of the archipelago is a protected habitat, including both the islands and the surrounding waters. There are 53

The islands' total population was 26,502 at the 2001 census, and the 2011 figure was 27,684. During the same period

The islands' total population was 26,502 at the 2001 census, and the 2011 figure was 27,684. During the same period

. . Retrieved 20 July 2013. which has a population of about 8,100. The population estimate for 2019 was 26,720 according to a Comhairle nan Eilean Siar report which added that "the population of the Outer Hebrides is ageing" and that "young adults ..leave the islands for further education or employment purposes". Of the total population, 6,953 people reside in the "Stornoway settlement Laxdale (Lacasdal), Sandwick (Sanndabhaig) and Newmarket" with the balance distributed over 280 townships. In addition to the major North Ford (') and South Ford causeways that connect North Uist to Benbecula via the northern of the

There are more than fifty uninhabited islands greater in size than in the Outer Hebrides, including the

There are more than fifty uninhabited islands greater in size than in the Outer Hebrides, including the

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from

The Hebrides were originally settled in the

The Hebrides were originally settled in the

As the Norse era drew to a close the Norse-speaking princes were gradually replaced by Gaelic-speaking

As the Norse era drew to a close the Norse-speaking princes were gradually replaced by Gaelic-speaking

With the implementation of the

With the implementation of the

Undiscovered Scotland. Retrieved 8 July 2010. The work of the

Modern commercial activities centre on tourism,

Modern commercial activities centre on tourism,

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 4 July 2010. There is some optimism about the possibility of future developments in, for example, renewable energy generation, tourism, and education, and after declines in the 20th century the population has stabilised since 2003, although it is ageing. A 2019 report, using key assumptions, (mortality, fertility and migration) was less optimistic. It predicted that the population is "projected to fall to 22,709 by 2043"; that translates to a 16% decline, or 4,021 people, between 2018 and 2043. The UK’s largest community-owned wind farm, Beinn Ghrideag, is located outside Stornoway, and operated by Point and Sandwick Trust (PST). Beinn Ghrideag is a 9 MW project (consisting of three 3 MW

The local authority is

The local authority is

Scheduled

Scheduled

The archipelago is exposed to wind and tide, and

The archipelago is exposed to wind and tide, and

''Adventure Guide to Scotland''

Hunter Publishing. Retrieved 19 May 2010. * Miers, Mary (2008) ''The Western Seaboard: An Illustrated Architectural Guide.'' The Rutland Press. * * W. H. Murray, Murray, W.H. (1966) ''The Hebrides''. London. Heinemann. * Murray, W.H. (1973) ''The Islands of Western Scotland: the Inner and Outer Hebrides.'' London. Eyre Methuen. * Ross, David (2005) ''Scotland – History of a Nation''. Lomond. * Rotary Club of Stornoway (1995) ''The Outer Hebrides Handbook and Guide''. Machynlleth. Kittiwake. * Thompson, Francis (1968) ''Harris and Lewis, Outer Hebrides''. Newton Abbot. David & Charles. * William J. Watson, Watson, W. J. (1994) ''The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland''. Edinburgh; Birlinn. . First published 1926.

Stornoway Port Authority

Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

2001 Census Results for the Outer Hebrides

MacTV

Reefnet

Hebrides.com

Photographic website from ex-Eolas Sam Maynard

www.visithebrides.com

Western Isles Tourist Board site from Reefnet

Virtual Hebrides.com

Content from the VH, which went its own way and became Virtual Scotland.

hebrides.ca

Home of the Quebec-Hebridean Scots who were cleared from Lewis to Quebec 1838–1920s {{DEFAULTSORT:Outer Hebrides Outer Hebrides, Hebrides, . Archipelagoes of Scotland Archipelagoes of the Atlantic Ocean Council areas of Scotland Lieutenancy areas of Scotland Regions of Scotland Former Norwegian colonies Gaelic culture

island chain

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

off the west coast of mainland Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

.

It is the longest archipelago in the British Isles. The islands form part of the archipelago of the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

, separated from the Scottish mainland and from the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides ( ; ) is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which experience a mild oceanic climate. The Inner Hebrides compri ...

by the waters of the Minch

The Minch () is a strait in north-west Scotland that separates the mainland from Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides. It was known as ("Scotland's firth") in Old Norse.

The Minch's southern extension, which separates Skye from the middle ...

, the Little Minch

The Minch () is a strait in north-west Scotland that separates the mainland from Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides. It was known as ("Scotland's firth") in Old Norse.

The Minch's southern extension, which separates Skye from the middle ...

, and the Sea of the Hebrides

The Sea of the Hebrides (, ) is a small and partly sheltered section of the North Atlantic Ocean, indirectly off the southern part of the north-west coast of Scotland. To the east are the mainland of Scotland and the northern Inner Hebrides (i ...

. The Outer Hebrides are considered to be the traditional heartland of the Gaelic language. The islands form one of the 32 council areas of Scotland

For local government purposes, Scotland is divided into 32 areas designated as "council areas" (), which are all governed by single-tier authorities designated as "councils". They have the option under the Local Government (Gaelic Names) (Sc ...

, which since 1998 has used only the Gaelic form of its name, including in English language contexts. The council area is called Na h-Eileanan an Iar ('the Western Isles') and its council is ('Council of the Western Isles').

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from ancient metamorphic

Metamorphic rocks arise from the transformation of existing rock to new types of rock in a process called metamorphism. The original rock (protolith) is subjected to temperatures greater than and, often, elevated pressure of or more, causi ...

rocks, and the climate is mild and oceanic. The 15 inhabited islands had a total population of in and there are more than 50 substantial uninhabited islands. The distance from Barra Head

Barra Head, also known as Berneray (), is the southernmost island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. Within the Outer Hebrides, it forms part of the Barra Isles archipelago. Originally, Barra Head only referred to the southernmost headland ...

to the Butt of Lewis

The Butt of Lewis () is the most northerly point on the Island of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. The headland, which lies in the North Atlantic, is frequently battered by heavy swells and storms and is marked by the Butt of Lewis Lig ...

is roughly .

There are various important prehistoric structures, many of which pre-date the first written references to the islands by Roman and Greek authors. The Western Isles became part of the Norse kingdom of the ', which lasted for over 400 years, until sovereignty over the Outer Hebrides was transferred to Scotland by the Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus the Lawmender of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had become Norwegian t ...

in 1266. Control of the islands was then held by clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

chiefs, principal amongst whom were the MacLeods, MacDonalds, and the MacNeils. The Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

of the 19th century had a devastating effect on many communities, and it is only in recent years that population levels have ceased to decline. Much of the land is now under local control, and commercial activity is based on tourism, crofting

Crofting (Scottish Gaelic: ') is a form of land tenure and small-scale food production peculiar to the Scottish Highlands, the islands of Scotland, and formerly on the Isle of Man. Within the 19th-century townships, individual crofts were est ...

, fishing, and weaving.

Sea transport is crucial for those who live and work in the Outer Hebrides, and a variety of ferry services operate between the islands and to mainland Scotland. Modern navigation systems now minimise the dangers, but in the past the stormy seas in the region have claimed many ships. The Gaelic language, religion, music and sport are important aspects of local culture, and there are numerous designated conservation areas to protect the natural environment.

Etymology

The earliest surviving written references relating to the islands were made byPliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

in his ''Natural History'', in which he states that there are 30 ', and makes a separate reference to ''Dumna'', which Watson (1926) concludes is unequivocally the Outer Hebrides. Writing about 80 years later, in 140–150 AD, Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, drawing on the earlier naval expeditions of , also distinguished between the ', of which he writes there were only five (and thus possibly meaning the Inner Hebrides

The Inner Hebrides ( ; ) is an archipelago off the west coast of mainland Scotland, to the south east of the Outer Hebrides. Together these two island chains form the Hebrides, which experience a mild oceanic climate. The Inner Hebrides compri ...

) and .Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11–13Watson (1926) pp. 40–41 ' is cognate with the Early Celtic ''dumnos'' and means the "deep-sea isle". Pliny probably took his information from Pytheas

Pytheas of Massalia (; Ancient Greek: Πυθέας ὁ Μασσαλιώτης ''Pythéās ho Massaliōtēs''; Latin: ''Pytheas Massiliensis''; born 350 BC, 320–306 BC) was a Greeks, Greek List of Graeco-Roman geographers, geographer, explo ...

of Massilia

Massalia (; ) was an ancient Greek colony (''apoikia'') on the Mediterranean coast, east of the Rhône. Settled by the Ionians from Phocaea in 600 BC, this ''apoikia'' grew up rapidly, and its population set up many outposts for trading in mode ...

who visited Britain sometime between 322 and 285 BC. It is possible that Ptolemy did as well, as Agricola's information about the west coast of Scotland was of poor quality. Breeze also suggests that might be Lewis and Harris

Lewis and Harris (), or Lewis with Harris, is a Scottish island in the Outer Hebrides, around from the Scottish mainland.

With an area of (approximately 1% the size of Great Britain) it is the largest island in Scotland and the list of isl ...

, the largest island of the Outer Hebrides although he conflates this single island with the name "Long Island". Watson (1926) states that the meaning of Ptolemy's ' is unknown and that the root may be pre-Celtic. Murray (1966) claims that Ptolemy's ' was originally derived from the Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

', meaning "isles on the edge of the sea". This idea is often repeated but no firm evidence of this derivation has emerged.

Other early written references include the flight of the Nemed

Nemed or Nimeth () is a character in medieval Irish legend. According to the '' Lebor Gabála Érenn'' (compiled in the 11th century), he was the leader of the third group of people to settle in Ireland: the ''Muintir Nemid'' (or ''Muintir Neim ...

people from Ireland to ''Domon'', which is mentioned in the 12th-century ' and a 13th-century poem concerning , then the heir to the throne of Mann and the Isles, who is said to have "broken the gate of '". ' means "the plain of Domhna (or Domon)", but the precise meaning of the text is not clear.

In Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths indigenous to the island of Ireland. It was originally Oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era. In the History of Ireland (795–1169), early medieval era, myths were ...

the islands were the home of the Fomorians

The Fomorians or Fomori (, Modern ) are a supernatural race in Irish mythology, who are often portrayed as hostile and monstrous beings. Originally they were said to come from under the sea or the earth. Later, they were portrayed as sea raider ...

, described as "huge and ugly" and "ship men of the sea". They were pirates, extracting tribute from the coasts of Ireland and one of their kings was (i.e. Indech, son of the goddess Domnu, who ruled over the deep seas).

Geography

The islands form an archipelago whose major islands are

The islands form an archipelago whose major islands are Lewis and Harris

Lewis and Harris (), or Lewis with Harris, is a Scottish island in the Outer Hebrides, around from the Scottish mainland.

With an area of (approximately 1% the size of Great Britain) it is the largest island in Scotland and the list of isl ...

, North Uist

North Uist (; ) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Etymology

In Donald Munro's ''A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides'' of 1549, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist are described as one isla ...

, Benbecula

Benbecula ( ; or ) is an island of the Outer Hebrides in the Atlantic Ocean off the west coast of Scotland. In the 2011 census, it had a resident population of 1,283 with a sizable percentage of Roman Catholics. It is in a zone administered by ...

, South Uist

South Uist (, ; ) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the rest of the Hebrides, is one of the ...

, and Barra

Barra (; or ; ) is an island in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland, and the second southernmost inhabited island there, after the adjacent island of Vatersay to which it is connected by the Vatersay Causeway.

In 2011, the population was 1,174. ...

. Lewis and Harris has an area of and is the largest island in Scotland and the third-largest in the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, after Great Britain and Ireland. It incorporates Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

in the north and Harris

Harris may refer to:

Places Canada

* Harris, Ontario

* Northland Pyrite Mine (also known as Harris Mine)

* Harris, Saskatchewan

* Rural Municipality of Harris No. 316, Saskatchewan

Scotland

* Harris, Outer Hebrides (sometimes called the Isle ...

in the south, both of which are frequently referred to as individual islands, although they are connected by land. The island does not have a single name in either English or Gaelic, and is referred to as "Lewis and Harris", "Lewis with Harris", "Harris with Lewis" etc.Thompson (1968) p. 13

The largest islands are deeply indented by arms of the sea such as Loch Ròg

Loch Ròg or Loch Roag is a large sea loch on the west coast of Isle of Lewis, Lewis, Outer Hebrides. It is broadly divided into East Loch Roag and West Loch Roag with other branches which include Little Loch Roag. The loch is dominated by the on ...

, Loch Seaforth

Loch Seaforth () is a sea loch in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It consists of three distinct sections; the most seaward is aligned northwest–southeast, a middle section is aligned northeast–southwest and the inner and most northerly sect ...

and Loch nam Madadh

''Loch'' ( ) is a word meaning "lake" or " sea inlet" in Scottish and Irish Gaelic, subsequently borrowed into English. In Irish contexts, it often appears in the anglicized form "lough". A small loch is sometimes called a lochan. Lochs which ...

. There are also more than 7,500 freshwater lochs in the Outer Hebrides, about 24% of the total for the whole of Scotland."Botanical survey of Scottish freshwater lochs"SNH Information and Advisory Note Number 4. Retrieved 1 January 2010. North and South Uist and Lewis, in particular, have landscapes with a high percentage of fresh water and a maze and complexity of loch shapes. Harris has fewer large bodies of water but has innumerable small lochans. Loch Langavat on Lewis is long, and has several large islands in its midst, including

Eilean Mòr

Eilean Mòr, literally meaning "large island" in Scottish Gaelic, is the name of several Scottish islands. In some areas, the term merely refers to the large island of a group, and may be used in place of the actual name:

Saltwater

* Eilean Mòr, ...

. Although Loch Suaineabhal has only 25% of Loch Langavat's surface area, it has a mean depth of and is the most voluminous on the island. Of Loch Sgadabhagh on North Uist

North Uist (; ) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Etymology

In Donald Munro's ''A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides'' of 1549, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist are described as one isla ...

it has been said that "there is probably no other loch in Britain which approaches Loch Scadavay in irregularity and complexity of outline." Loch Bì is South Uist's largest loch and at long it all but cuts the island in two.

Much of the western coastline of the islands is machair

A machair (; sometimes machar in English) is a fertile low-lying grassy plain found on part of the northwestern coastlines of Ireland and Scotland, particularly the Outer Hebrides. The best examples are found on North and South Uist, Harris ...

, a fertile low-lying dune pastureland. Lewis is comparatively flat, and largely consists of treeless moors of blanket peat

Peat is an accumulation of partially Decomposition, decayed vegetation or organic matter. It is unique to natural areas called peatlands, bogs, mires, Moorland, moors, or muskegs. ''Sphagnum'' moss, also called peat moss, is one of the most ...

. The highest eminence is Mealisval at in the south west. Most of Harris

Harris may refer to:

Places Canada

* Harris, Ontario

* Northland Pyrite Mine (also known as Harris Mine)

* Harris, Saskatchewan

* Rural Municipality of Harris No. 316, Saskatchewan

Scotland

* Harris, Outer Hebrides (sometimes called the Isle ...

is mountainous, with large areas of exposed rock and Clisham

The Clisham () is a mountain on North Harris, Lewis and Harris in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. At , it is the highest mountain in the Outer Hebrides and the archipelago's only Corbett. Climbers often encounter light rain and boggy and mudd ...

, the archipelago's only Corbett, reaches in height.Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 289 North and South Uist and Benbecula (sometimes collectively referred to as The Uists

Uist is a group of six islands that are part of the Outer Hebridean Archipelago, which is part of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

North Uist and South Uist ( or ; ) are two of the islands and are linked by causeways running via the isles of Ben ...

) have sandy beaches and wide cultivated areas of machair to the west and virtually uninhabited mountainous areas to the east. The highest peak here is Beinn Mhòr at . The Uists and their immediate outliers have a combined area of . This includes the Uists themselves and the islands linked to them by causeways and bridges. Barra is in extent and has a rugged interior, surrounded by machair and extensive beaches.

The scenic qualities of the islands are reflected in the fact that three of Scotland's forty national scenic areas

National may refer to:

Common uses

* Nation or country

** Nationality – a ''national'' is a person who is subject to a nation, regardless of whether the person has full rights as a citizen

Places in the United States

* National, Maryland, ce ...

(NSAs) are located here. The national scenic areas are defined so as to identify areas of exceptional scenery and to ensure its protection from inappropriate development, and are considered to represent the type of scenic beauty "popularly associated with Scotland and for which it is renowned". The three NSA within the Outer Hebrides are:

* South Lewis, Harris and North Uist National Scenic Area covers the mountainous south west of Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

, all of Harris

Harris may refer to:

Places Canada

* Harris, Ontario

* Northland Pyrite Mine (also known as Harris Mine)

* Harris, Saskatchewan

* Rural Municipality of Harris No. 316, Saskatchewan

Scotland

* Harris, Outer Hebrides (sometimes called the Isle ...

, the Sound of Harris and the northern part of North Uist

North Uist (; ) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Etymology

In Donald Munro's ''A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides'' of 1549, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist are described as one isla ...

.

*An area of the south west coast of South Uist

South Uist (, ; ) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the rest of the Hebrides, is one of the ...

is designated as the ''South Uist Machair National Scenic Area''.

*The archipelago of St Kilda is also listed as an NSA, alongside many other conservation designations.

Flora and fauna

Much of the archipelago is a protected habitat, including both the islands and the surrounding waters. There are 53

Much of the archipelago is a protected habitat, including both the islands and the surrounding waters. There are 53 Sites of Special Scientific Interest

A Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) in Great Britain, or an Area of Special Scientific Interest (ASSI) in the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland, is a conservation designation denoting a protected area in the United Kingdom and Isle ...

of which the largest are Loch an Duin, North Uist () and North Harris (). South Uist

South Uist (, ; ) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the rest of the Hebrides, is one of the ...

is considered the best place in the UK for the aquatic plant Slender Naiad, which is a European Protected Species.

There has been considerable controversy over hedgehog

A hedgehog is a spiny mammal of the subfamily Erinaceinae, in the eulipotyphlan family Erinaceidae. There are 17 species of hedgehog in five genera found throughout parts of Europe, Asia, and Africa, and in New Zealand by introduction. The ...

s on the Uists. Hedgehogs are not native to the islands but were introduced in the 1970s to reduce garden pests. Their spread posed a threat to the eggs of ground-nesting wading birds. In 2003 Scottish Natural Heritage undertook culls of hedgehogs in the area, but these were halted in 2007; trapped animals are now relocated to the mainland.

Nationally important populations of breeding waders are present in the Outer Hebrides, including common redshank

The common redshank or simply redshank (''Tringa totanus'') is a Eurasian wader in the large family Scolopacidae.

Taxonomy

The common redshank was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of hi ...

, dunlin

The dunlin (''Calidris alpina'') is a small wader in the genus '' Calidris''. The English name is a dialect form of "dunling", first recorded in 1531–1532. It derives from ''dun'', "dull brown", with the suffix ''-ling'', meaning a person or ...

, lapwing

Lapwings (subfamily Vanellinae) are any of various ground-nesting birds (Family (biology), family Charadriidae) akin to plovers and dotterels. They range from in length, and are noted for their slow, irregular wingbeats in flight and a shrill, ...

and ringed plover

The common ringed plover or ringed plover (''Charadrius hiaticula'') is a species of bird in the family Charadriidae. It breeds across much of northern Eurasia, as well as Greenland.

Taxonomy

The common ringed plover was Species description, f ...

. The islands also provide a habitat for other important species such as corncrake

The corn crake, corncrake or landrail (''Crex crex'') is a bird in the Rallidae, rail family. It breeds in Europe and Asia as far east as western China, and bird migration, migrates to Africa for the Northern Hemisphere's winter. It is a medium ...

, hen harrier

The hen harrier (''Circus cyaneus'') is a bird of prey. It breeds in Palearctic, Eurasia. The term "hen harrier" refers to its former habit of preying on free-ranging fowl.

It bird migration, migrates to more southerly areas in winter. Eurasian ...

, golden eagle

The golden eagle (''Aquila chrysaetos'') is a bird of prey living in the Northern Hemisphere. It is the most widely distributed species of eagle. Like all eagles, it belongs to the family Accipitridae. They are one of the best-known bird of pr ...

and otter

Otters are carnivorous mammals in the subfamily Lutrinae. The 13 extant otter species are all semiaquatic, aquatic, or marine. Lutrinae is a branch of the Mustelidae family, which includes weasels, badgers, mink, and wolverines, among ...

. Offshore, basking shark

The basking shark (''Cetorhinus maximus'') is the second-largest living shark and fish, after the whale shark. It is one of three Planktivore, plankton-eating shark species, along with the whale shark and megamouth shark. Typically, basking sh ...

and various species of whale and dolphin can often be seen, and the remoter islands' seabird populations are of international significance. St Kilda has 60,000 northern gannet

The northern gannet (''Morus bassanus'') is a seabird, the largest species of the gannet family, Sulidae. It is native to the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, breeding in Western Europe and Northeastern North America. It is the largest seabird in t ...

s, amounting to 24% of the world population; 49,000 breeding pairs of Leach's petrel

Leach's storm petrel or Leach's petrel (''Hydrobates leucorhous'') is a small seabird of the tubenose order. It is named after the British zoologist William Elford Leach. The scientific name is derived from Ancient Greek. ''Hydrobates'' is from ...

, up to 90% of the European population; and 136,000 pairs of puffin

Puffins are any of three species of small alcids (auks) in the bird genus ''Fratercula''. These are pelagic seabirds that feed primarily by diving in the water. They breed in large colonies on coastal cliffs or offshore islands, nesting in crev ...

and 67,000 northern fulmar

The northern fulmar (''Fulmarus glacialis''), fulmar, or Arctic fulmar is an abundant seabird found primarily in subarctic regions of the North Atlantic and North Pacific oceans. There has been one confirmed sighting in the Southern Hemisphere, ...

pairs, about 30% and 13% of the respective UK totals. Mingulay

Mingulay () is the second largest of the Bishop's Isles in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. Located south of Barra, it is known for an extensive Gaelic oral tradition incorporating folklore, song and stories and its important seabird populations ...

is an important breeding ground for razorbill

The razorbill (''Alca torda'') is a North Atlantic colonial seabird and the only extant member of the genus ''Alca (bird), Alca'' of the family Alcidae, the auks. It is the closest living relative of the extinct great auk (''Pinguinus impennis' ...

s, with 9,514 pairs, 6.3% of the European population.

The bumblebee

A bumblebee (or bumble bee, bumble-bee, or humble-bee) is any of over 250 species in the genus ''Bombus'', part of Apidae, one of the bee families. This genus is the only Extant taxon, extant group in the tribe Bombini, though a few extinct r ...

''Bombus jonellus'' var. ''hebridensis'' is endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to the Hebrides and there are local variants of the dark green fritillary

The dark green fritillary (''Speyeria aglaja'') is a species of butterfly in the family Nymphalidae. The insect has a wide range in the Palearctic realm - Europe, Morocco, Iran, Siberia, Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan.

Taxonomy

The dark g ...

and green-veined white

The green-veined white (''Pieris napi'') is a butterfly of the family Pieridae.

Appearance and distribution

A Circumboreal Region, circumboreal species widespread across Europe and Asia, including the Indian subcontinent, Japan, the Maghreb and ...

butterflies. The St Kilda wren

The St Kilda wren (''Troglodytes troglodytes hirtensis'') is a small passerine bird in the wren family. It is a distinctive subspecies of the Eurasian wren endemic to the islands of the isolated St Kilda archipelago, in the Atlantic Ocean wes ...

is a subspecies of wren

Wrens are a family, Troglodytidae, of small brown passerine birds. The family includes 96 species and is divided into 19 genera. All species are restricted to the New World except for the Eurasian wren that is widely distributed in the Old Worl ...

whose range is confined to the islands whose name it bears.

Population

The islands' total population was 26,502 at the 2001 census, and the 2011 figure was 27,684. During the same period

The islands' total population was 26,502 at the 2001 census, and the 2011 figure was 27,684. During the same period Scottish island

This is a list of islands of Scotland, the mainland of which is part of the island of Great Britain. Also included are various other related tables and lists. The definition of an offshore island used in this list is "land that is surrounded by ...

populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702. The largest settlement in the Outer Hebrides is Stornoway

Stornoway (; ) is the main town, and by far the largest, of the Outer Hebrides (or Western Isles), and the capital of Lewis and Harris in Scotland.

The town's population is around 6,953, making it the third-largest island town in Scotlan ...

on Lewis,"Factfile:Population". . Retrieved 20 July 2013. which has a population of about 8,100. The population estimate for 2019 was 26,720 according to a Comhairle nan Eilean Siar report which added that "the population of the Outer Hebrides is ageing" and that "young adults ..leave the islands for further education or employment purposes". Of the total population, 6,953 people reside in the "Stornoway settlement Laxdale (Lacasdal), Sandwick (Sanndabhaig) and Newmarket" with the balance distributed over 280 townships. In addition to the major North Ford (') and South Ford causeways that connect North Uist to Benbecula via the northern of the

Grimsay

Grimsay () is a tidal island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Geography

Grimsay is the largest of the low-lying stepping-stones which convey the Oitir Mhòr (North Ford) causeway, a arc of single track road linking North Uist and Benbecul ...

s, and another causeway from Benbecula to South Uist, several other islands are linked by smaller causeways or bridges. Great Bernera

Great Bernera (; ), often known just as Bernera (), is an island and community council, community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. With an area of just over , it is the thirty-fourth largest List of islands of Scotland, Scottish island.

Great ...

and Scalpay have bridge connections to Lewis and Harris respectively, with causeways linking Baleshare and Berneray to North Uist; Eriskay

Eriskay (), from the Old Norse for "Eric's Isle", is an island and community council area of the Outer Hebrides in northern Scotland with a population of 143, as of the United Kingdom Census 2011, 2011 census. It lies between South Uist and Bar ...

to South Uist; , and the southern Grimsay

Grimsay () is a tidal island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Geography

Grimsay is the largest of the low-lying stepping-stones which convey the Oitir Mhòr (North Ford) causeway, a arc of single track road linking North Uist and Benbecul ...

to Benbecula; and the Vatersay Causeway

The Vatersay Causeway () is a 250-metre-long causeway that links the Scottish Hebridean Islands of Vatersay and Barra across the Sound of Vatersay ().

The causeway was constructed between 1989 and 1991, and provides a direct link between V ...

linking Vatersay

The island of Vatersay (; ) is the southernmost and westernmost inhabited island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, and the settlement of Caolas on the north coast of the island is the westernmost permanently inhabited place in Scotland. The m ...

to Barra."Get-a-map"Ordnance Survey

The Ordnance Survey (OS) is the national mapping agency for Great Britain. The agency's name indicates its original military purpose (see Artillery, ordnance and surveying), which was to map Scotland in the wake of the Jacobite rising of ...

. Retrieved 1–15 August 2009."Fleet Histories"Caledonian MacBrayne

Caledonian MacBrayne (), in short form CalMac, is the trade name of CalMac Ferries Ltd, the major operator of passenger and vehicle ferries to the west coast of Scotland, serving ports on the mainland and 22 of the major islands. It is a subsid ...

. Retrieved 3 August 2009. This means that all the inhabited islands are now connected to at least one other island by a land transport route.

Uninhabited islands

There are more than fifty uninhabited islands greater in size than in the Outer Hebrides, including the

There are more than fifty uninhabited islands greater in size than in the Outer Hebrides, including the Barra Isles

The Barra Isles, also known as the Bishop's Isles, are a small archipelago in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. They lie south of the island of Barra, for which they are named. The group consists of nine islands and numerous rocky islets, skerries ...

, Flannan Isles

The Flannan Isles () or the Seven Hunters are a small island group in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland, approximately west of the Isle of Lewis. They may take their name from Saint Flannan, the 7th century Irish preacher and abbot.

The islan ...

, Monach Islands

The Monach Islands, also known as Heisker ( / , ), are an island group west of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. The islands are not to be confused with Hyskeir in the Inner Hebrides, or Haskeir which is also off North Uist and ...

, the Shiant Islands

The Shiant Islands (; or ) or Shiant Isles are a privately owned island group in the Minch, east of Harris, Outer Hebrides, Harris in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. They are southeast of the Isle of Lewis.Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) ''Collin ...

and the islands of . In common with the other main island chains of Scotland, many of the more remote islands were abandoned during the 19th and 20th centuries, in some cases after continuous habitation since the prehistoric period. More than 35 such islands have been identified in the Outer Hebrides alone. On Barra Head, for example, Historic Scotland

Historic Scotland () was an executive agency of the Scottish Government, executive agency of the Scottish Office and later the Scottish Government from 1991 to 2015, responsible for safeguarding Scotland's built heritage and promoting its und ...

have identified eighty-three archaeological sites on the island, the majority being of a pre-medieval date. In the 18th century, the population was over fifty, but the last native islanders had left by 1931. The island became completely uninhabited by 1980 with the automation of the lighthouse.

Some of the smaller islands continue to contribute to modern culture. The "Mingulay Boat Song

The "Mingulay Boat Song" is a song written by Sir Hugh S. Roberton (1874–1952) in the 1930s. The melody is described in Roberton's ''Songs of the Isles'' as a traditional Gaelic tune, probably titled "Lochaber". The tune was part of an old Gael ...

", although evocative of island life, was written after the abandonment of the island in 1938 and Taransay

Taransay (, ) is an island in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland. It was the host of the British television series ''Castaway 2000''. Uninhabited since 1974, except for holidaymakers, Taransay is the largest List of islands of Scotland, Scottish is ...

hosted the BBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

television series ''Castaway 2000

''Castaway 2000'' is a reality television programme broadcast on BBC One throughout 2000. The programme followed a group of thirty-six men, women, and children who were tasked with building a community on the Scottish island of Taransay, off th ...

''. Others have played a part in Scottish history. On 4 May 1746, the "Young Pretender" Charles Edward Stuart

Charles Edward Louis John Sylvester Maria Casimir Stuart (31 December 1720 – 30 January 1788) was the elder son of James Francis Edward Stuart, making him the grandson of James VII and II, and the Stuart claimant to the thrones of England, ...

hid on with some of his men for four days whilst Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

vessels patrolled the Minch.

Smaller isles and skerries

A skerry is a small rocky island, usually defined to be too small for habitation.

Skerry, skerries, or The Skerries may also refer to:

Geography

Northern Ireland

*Skerries, County Armagh, a List of townlands in County Armagh#S, townland in Coun ...

and other island groups pepper the North Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

surrounding the main islands. Some are not geologically part of the Outer Hebrides, but are administratively and in most cases culturally, part of . to the west of Lewis lies St Kilda, now uninhabited except for a small military base. A similar distance to the north of Lewis are North Rona

Rona () is an uninhabited Scottish island in the North Atlantic. It is often referred to as North Rona to distinguish it from the island of South Rona in the Inner Hebrides. It has an area of and a maximum elevation of .

It is the most isolat ...

and , two small and remote islands. While Rona used to support a small population who grew grain and raised cattle, is an inhospitable rock. Thousands of northern gannet

The northern gannet (''Morus bassanus'') is a seabird, the largest species of the gannet family, Sulidae. It is native to the coasts of the Atlantic Ocean, breeding in Western Europe and Northeastern North America. It is the largest seabird in t ...

s nest here, and by special arrangement some of their young, known as ', are harvested annually by the men of Ness

Ness or NESS may refer to:

Places Australia

* Ness, Wapengo, a heritage-listed natural coastal area in New South Wales

United Kingdom

* Ness, Cheshire, England, a village

* Ness, Lewis, the most northerly area on Lewis, Scotland, UK

* Cuspate ...

. The status of Rockall

Rockall () is a high, uninhabitable granite islet in the North Atlantic Ocean. It is west of Soay, St Kilda, Scotland; northwest of Tory Island, Ireland; and south of Iceland.

The nearest permanently inhabited place is North Uist, east in ...

, which is to the west of North Uist and which the Island of Rockall Act 1972

The Island of Rockall Act 1972 (c. 2) is a British act of Parliament formally incorporating the island of Rockall into the United Kingdom to protect it from Irish and Icelandic claims. The act as originally passed declared that the Island of R ...

decreed to be a part of the Western Isles, remains a matter of international dispute.

Settlements

A 2018 development plan divides the Outer Hebrides settlements into four types: Stornoway core, main settlements, rural settlements and outwith settlements. The main settlements areTarbert

Tarbert () is a place name in Scotland and Ireland. Places named Tarbert are characterised by a narrow strip of land, or isthmus. This can be where two lochs nearly meet, or a causeway out to an island.

Etymology

All placenames that variously s ...

, Lochmaddy

Lochmaddy ( , "Loch of the Hounds") is the administrative centre of North Uist in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. ''Na Madaidhean'' (the wolves/hounds) are rocks in the bay after which the loch, and subsequently the village, are named. Lochmaddy i ...

, Balivanich

Balivanich ( ) is a village on the island of Benbecula in the Outer Hebrides off the west coast of Scotland. It is the main centre for Benbecula and the adjacent islands of North Uist, South Uist and several smaller islands. Balivanich is with ...

, Lochboisdale

Lochboisdale ( ) is the main village and port on the island of South Uist, Outer Hebrides, Scotland. Lochboisdale is within the parish of South Uist, and is situated on the shore of Loch Baghasdail at the southern end of the A865.

History

The ...

/Daliburgh

Daliburgh () is a crofting township on South Uist, in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. Daliburgh is situated west from Lochboisdale, has the second largest population of any township in South Uist, and is also in the parish of South Uist. Dalibur ...

, Greater Castlebay and greater Stornoway (excluding Stornoway core).

Combining with data from the National Records of Scotland

National Records of Scotland () is a non-ministerial department of the Scottish Government. It is responsible for civil registration, the census in Scotland, demography and statistics, family history, as well as the national archives and hist ...

, the principal settlements are:

The dispersed settlements consisting of rural settlements and outwith settlements account for about two-thirds of the population of the council area, since the total population of the table is about 9,000.

Geology

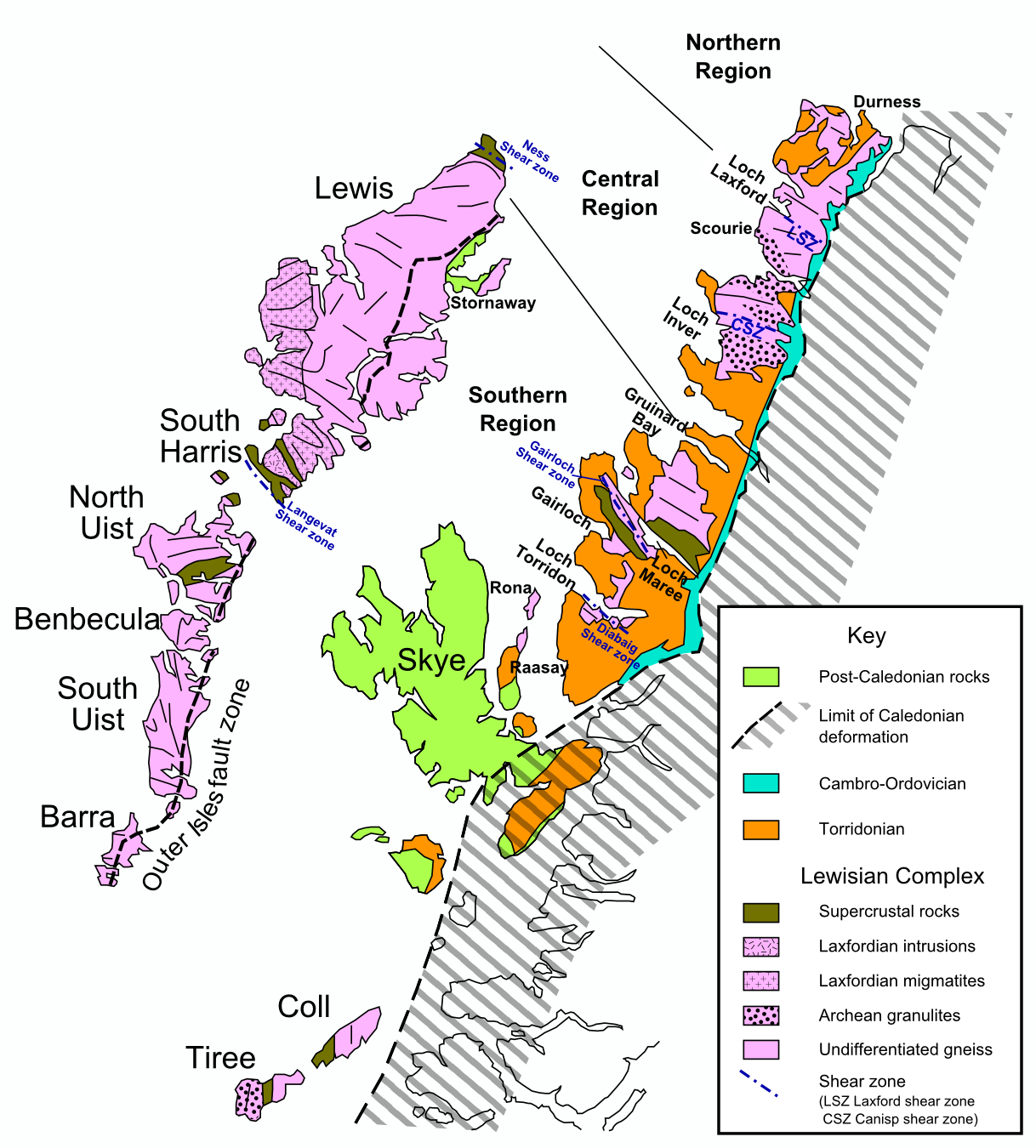

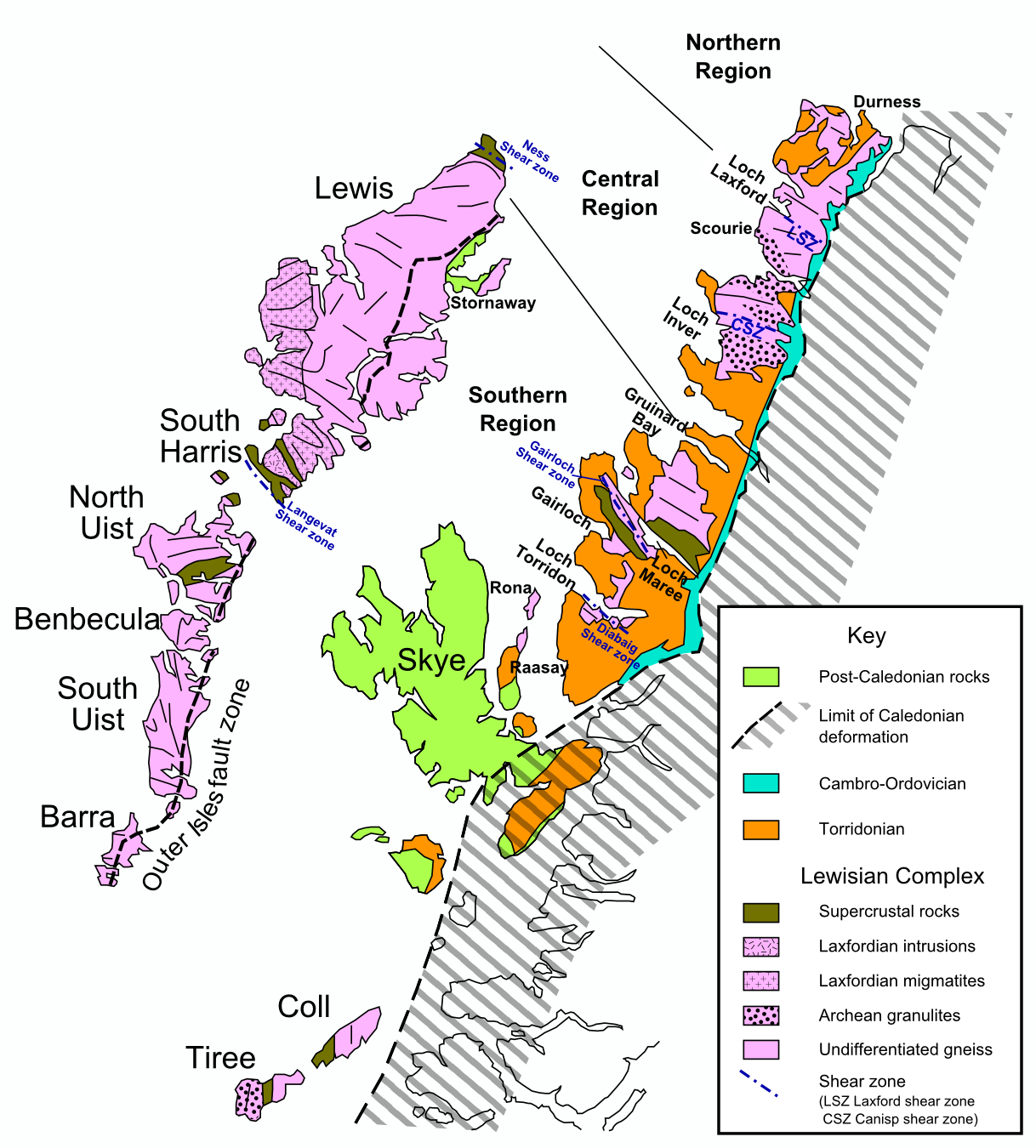

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from Lewisian gneiss

The Lewisian complex or Lewisian gneiss is a suite of Precambrian metamorphic rocks that outcrop in the northwestern part of Scotland, forming part of the Hebridean terrane and the North Atlantic Craton. These rocks are of Archaean and Paleopr ...

. These are amongst the oldest rocks in Europe, having been formed in the Precambrian

The Precambrian ( ; or pre-Cambrian, sometimes abbreviated pC, or Cryptozoic) is the earliest part of Earth's history, set before the current Phanerozoic Eon. The Precambrian is so named because it preceded the Cambrian, the first period of t ...

period up to three billion years ago. In addition to the Outer Hebrides, they form basement deposits on the Scottish mainland west of the Moine Thrust

The Moine Thrust Belt or Moine Thrust Zone is a linear tectonic feature in the Scottish Highlands which runs from Loch Eriboll on the north coast southwest to the Sleat peninsula on the Isle of Skye. The thrust belt consists of a series of thr ...

and on the islands of Coll

Coll (; )Mac an Tàilleir (2003) p. 31 is an island located west of the Isle of Mull and northeast of Tiree in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Coll is known for its sandy beaches, which rise to form large sand dunes, for its corncrakes, and fo ...

and Tiree

Tiree (; , ) is the most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The low-lying island, southwest of Coll, has an area of and a population of around 650.

The land is highly fertile, and crofting, alongside tourism, and fishing are ...

. These rocks are largely igneous in origin, mixed with metamorphosed marble

Marble is a metamorphic rock consisting of carbonate minerals (most commonly calcite (CaCO3) or Dolomite (mineral), dolomite (CaMg(CO3)2) that have recrystallized under the influence of heat and pressure. It has a crystalline texture, and is ty ...

, quartzite

Quartzite is a hard, non- foliated metamorphic rock that was originally pure quartz sandstone.Essentials of Geology, 3rd Edition, Stephen Marshak, p 182 Sandstone is converted into quartzite through heating and pressure usually related to tecton ...

and mica schist

Schist ( ) is a medium-grained metamorphic rock generally derived from fine-grained sedimentary rock, like shale. It shows pronounced ''schistosity'' (named for the rock). This means that the rock is composed of mineral grains easily seen with a l ...

and intruded by later basaltic dykes and granite magma. The gneiss's delicate pink colours are exposed throughout the islands and it is sometimes referred to by geologists as "The Old Boy".Murray (1966) p. 2

Granite intrusions are found in the parish of Barvas

Barvas (Scottish Gaelic: ''Barabhas'' or ''Barbhas'', ) is a settlement, community and civil parish on the Isle of Lewis in Scotland. It developed around a road junction. The A857 and A858 meet at the southern end of Barvas. North is the road ...

in west Lewis, and another forms the summit plateau of the mountain Roineabhal in Harris. The granite here is anorthosite

Anorthosite () is a phaneritic, intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock characterized by its composition: mostly plagioclase feldspar (90–100%), with a minimal mafic component (0–10%). Pyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, and olivine are the mafic ...

, and is similar in composition to rocks found in the mountains of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

. There are relatively small outcrops of Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

sandstone at Broad Bay near Stornoway. The Shiant Islands and St Kilda are formed from much later tertiary basalt

Basalt (; ) is an aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained) extrusive igneous rock formed from the rapid cooling of low-viscosity lava rich in magnesium and iron (mafic lava) exposed at or very near the planetary surface, surface of a terrestrial ...

and basalt and gabbro

Gabbro ( ) is a phaneritic (coarse-grained and magnesium- and iron-rich), mafic intrusive igneous rock formed from the slow cooling magma into a holocrystalline mass deep beneath the Earth's surface. Slow-cooling, coarse-grained gabbro is ch ...

s respectively. The sandstone at Broad Bay was once thought to be Torridonian

The Torridonian is the informal name given to a sequence of Mesoproterozoic to Neoproterozoic sedimentary rocks that outcrop in a strip along the northwestern coast of Scotland and some parts of the Inner Hebrides from the Isle of Mull in the sou ...

or Old Red Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone, abbreviated ORS, is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the eastern seaboard of North America. It ...

.

Climate

The Outer Hebrides have a cool temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerlylatitude

In geography, latitude is a geographic coordinate system, geographic coordinate that specifies the north-south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from −90° at t ...

, due to the influence of the North Atlantic Current

The North Atlantic Current (NAC), also known as North Atlantic Drift and North Atlantic Sea Movement, is a powerful warm western boundary current within the Atlantic Ocean that extends the Gulf Stream northeastward.

Characteristics

The NAC ...

. The average temperature is 6 °C (44 °F) in January and 14 °C (57 °F) in summer. The average annual rainfall in Lewis is and sunshine hours range from 1,100 to 1,200 per year. The summer days are relatively long and May to August is the driest period. Winds are a key feature of the climate and even in summer there are almost constant breezes. According to the writer W. H. Murray if a visitor asks an islander for a weather forecast "he will not, like a mainlander answer dry, wet or sunny, but quote you a figure from the Beaufort Scale

The Beaufort scale ( ) is an empirical measure that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea or on land. Its full name is the Beaufort wind force scale. It was devised in 1805 by Francis Beaufort a hydrographer in the Royal Navy. It ...

." There are gales one day in six at the Butt of Lewis

The Butt of Lewis () is the most northerly point on the Island of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland. The headland, which lies in the North Atlantic, is frequently battered by heavy swells and storms and is marked by the Butt of Lewis Lig ...

and small fish are blown onto the grass on top of 190 metre (620 ft) high cliffs at Barra Head

Barra Head, also known as Berneray (), is the southernmost island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. Within the Outer Hebrides, it forms part of the Barra Isles archipelago. Originally, Barra Head only referred to the southernmost headland ...

during winter storms.

Prehistory

The Hebrides were originally settled in the

The Hebrides were originally settled in the Mesolithic era

The Mesolithic (Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic is often used synonymous ...

and have a diversity of important prehistoric

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use o ...

sites. in on North Uist

North Uist (; ) is an island and community in the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

Etymology

In Donald Munro's ''A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland Called Hybrides'' of 1549, North Uist, Benbecula and South Uist are described as one isla ...

was constructed around 3200–2800 BC and may be Scotland's earliest crannog

A crannog (; ; ) is typically a partially or entirely artificial island, usually constructed in lakes, bogs and estuary, estuarine waters of Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. Unlike the prehistoric pile dwellings around the Alps, which were built ...

(a type of artificial island). The Callanish Stones

The Calanais Stones (or "Calanais I": or ) are an arrangement of menhir, standing stones placed in a cruciform pattern with a central stone circle, located on the Isle of Lewis, Scotland. They were erected in the late Neolithic British Isles, Ne ...

, dating from about 2900 BC, are the finest example of a stone circle

A stone circle is a ring of megalithic standing stones. Most are found in Northwestern Europe – especially Stone circles in the British Isles and Brittany – and typically date from the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, with most being ...

in Scotland, the 13 primary monolith

A monolith is a geological feature consisting of a single massive stone or rock, such as some mountains. Erosion usually exposes the geological formations, which are often made of very hard and solid igneous or metamorphic rock. Some monolit ...

s of between one and five metres high creating a circle about in diameter. on South Uist

South Uist (, ; ) is the second-largest island of the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. At the 2011 census, it had a usually resident population of 1,754: a decrease of 64 since 2001. The island, in common with the rest of the Hebrides, is one of the ...

, the only site in the UK where prehistoric mummies

A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and Organ (biology), organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to Chemical substance, chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the ...

have been found, and the impressive ruins of Dun Carloway

Dun Carloway () is a broch situated in the district of Carloway, on the west coast of the Isle of Lewis, Scotland (). It is a remarkably well preserved broch – on the east side parts of the old wall still reach to 9 metres tall.

History

Mo ...

on Lewis both date from the Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

.

History

In Scotland, the CelticIron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

way of life, often troubled but never extinguished by Rome, re-asserted itself when the legions abandoned any permanent occupation in 211 AD. Hanson (2003) writes: "For many years it has been almost axiomatic in studies of the period that the Roman conquest must have had some major medium or long-term impact on Scotland. On present evidence that cannot be substantiated either in terms of environment, economy, or, indeed, society. The impact appears to have been very limited. The general picture remains one of broad continuity, not of disruption ... The Roman presence in Scotland was little more than a series of brief interludes within a longer continuum of indigenous development." The Romans' direct impact on the Highlands and Islands was scant and there is no evidence that they ever actually landed in the Outer Hebrides.

The later Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

inhabitants of the northern and western Hebrides were probably Pict

PICT is a graphics file format introduced on the original Apple Macintosh computer as its standard metafile format. It allows the interchange of graphics (both bitmapped and vector), and some limited text support, between Mac applications, an ...

ish, although the historical record is sparse. Hunter (2000) states that in relation to King Bridei I of the Picts

Bridei son of Maelchon (died 586) was King of the Picts from 554 to 584. Sources are vague or contradictory regarding him, but it is believed that his court was near Loch Ness and that he may have been a Christian. Several contemporaries als ...

in the sixth century AD: "As for Shetland, Orkney, Skye and the Western Isles, their inhabitants, most of whom appear to have been Pictish in culture and speech at this time, are likely to have regarded Bridei as a fairly distant presence." The island of Pabbay is the site of the Pabbay Stone, the only extant Pictish symbol stone in the Outer Hebrides. This 6th century stele

A stele ( ) or stela ( )The plural in English is sometimes stelai ( ) based on direct transliteration of the Greek, sometimes stelae or stelæ ( ) based on the inflection of Greek nouns in Latin, and sometimes anglicized to steles ( ) or stela ...

shows a flower, V-rod and lunar crescent to which has been added a later and somewhat crude cross.

Norse control

Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

raids began on Scottish shores towards the end of the 8th century AD and the Hebrides came under Norse control and settlement during the ensuing decades, especially following the success of Harald Fairhair

Harald Fairhair (; – ) was a Norwegian king. According to traditions current in Norway and Iceland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, he reigned from 872 to 930 and was the first Monarchy of Norway, King of Norway. Supposedly, two ...

at the Battle of Hafrsfjord

The Battle of Hafrsfjord () was a naval battle fought in Hafrsfjord sometime between 872 and 900 that resulted in the unification of Norway, later known as the Kingdom of Norway (872–1397), Kingdom of Norway. After the battle, the victorious Vi ...

in 872. In the Western Isles Ketill Flatnose

Ketill Björnsson, nicknamed Flatnose (Old Norse: ''Flatnefr''), was a Norse King of the Isles of the 9th century.

Primary sources

The story of Ketill and his daughter Auðr, or Aud the Deep-Minded, was probably first recorded by the Icelande ...

was the dominant figure of the mid 9th century, by which time he had amassed a substantial island realm and made a variety of alliances with other Norse leaders. These princelings nominally owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown, although in practice the latter's control was fairly limited. Norse control of the Hebrides was formalised in 1098 when Edgar, King of Scotland

Edgar or Étgar mac Maíl Choluim ( Modern Gaelic: ''Eagar mac Mhaoil Chaluim''), nicknamed Probus, "the Valiant" (c. 1074 – 8 January 1107), was King of Alba (Scotland) from 1097 to 1107. He was the fourth son of Malcolm III and Margaret o ...

formally signed the islands over to Magnus III of Norway

Magnus III Olafsson (Old Norse: ''Magnús Óláfsson'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Olavsson''; 1073 – 24 August 1103), better known as Magnus Barefoot (Old Norse: ''Magnús berfœttr'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Berrføtt''), was the King of Norway ...

.Hunter (2000) p. 102 The Scottish acceptance of Magnus III as King of the Isles came after the Norwegian king had conquered Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

in a swift campaign earlier the same year, directed against the local Norwegian leaders of the various islands‘ petty kingdoms. By capturing the islands Magnus imposed a more direct royal control, although at a price. His skald

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry in alliterative verse, the other being Eddic poetry. Skaldic poems were traditionally compo ...

Bjorn Cripplehand recorded that in Lewis "fire played high in the heaven" as "flame spouted from the houses" and that in the Uists "the king dyed his sword red in blood". Thompson (1968) provides a more literal translation: "Fire played in the fig-trees of Liodhus; it mounted up to heaven. Far and wide the people were driven to flight. The fire gushed out of the houses".Thompson (1968) p 39

The Hebrides were now part of Kingdom of the Isles, whose rulers were themselves vassals of the Kings of Norway. The Kingdom had two parts: the ' or South Isles encompassing the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

and the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man ( , also ), or Mann ( ), is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, between Great Britain and Ireland. As head of state, Charles III holds the title Lord of Mann and is represented by a Lieutenant Govern ...

; and the ' or North Isles of Orkney and Shetland

Shetland (until 1975 spelled Zetland), also called the Shetland Islands, is an archipelago in Scotland lying between Orkney, the Faroe Islands, and Norway, marking the northernmost region of the United Kingdom. The islands lie about to the ...

. This situation lasted until the partitioning of the Western Isles in 1156, at which time the Outer Hebrides remained under Norwegian control while the Inner Hebrides broke out under Somerled

Somerled (died 1164), known in Middle Irish as Somairle, Somhairle, and Somhairlidh, and in Old Norse as Sumarliði , was a mid-12th-century Norse-Gaelic lord who, through marital alliance and military conquest, rose in prominence to create the ...

, the Norse-Celtic kinsman of the Manx royal house.

Following the ill-fated 1263 expedition of Haakon IV of Norway

Haakon IV Haakonsson ( – 16 December 1263; ; ), sometimes called Haakon the Old in contrast to his namesake son, was King of Norway from 1217 to 1263. His reign lasted for 46 years, longer than any Norwegian king since Harald Fairhair. Haak ...

, the Outer Hebrides along with the Isle of Man, were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth

The Treaty of Perth, signed 2 July 1266, ended military conflict between Magnus the Lawmender of Norway and Alexander III of Scotland over possession of the Hebrides and the Isle of Man.

The Hebrides and the Isle of Man had become Norwegian t ...

. Although their contribution to the islands can still be found in personal and placenames, the archaeological record of the Norse period is very limited. The best known find from this time is the Lewis chessmen

The Lewis chessmen ( ) or Uig chessmen, named after the island or the bay where they were found, are a group of distinctive 12th-century chess pieces, along with other game pieces, most of which are carved from walrus ivory. Discovered in 1831 ...

, which date from the mid 12th century.

Scots rule

As the Norse era drew to a close the Norse-speaking princes were gradually replaced by Gaelic-speaking

As the Norse era drew to a close the Norse-speaking princes were gradually replaced by Gaelic-speaking clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

chiefs including the MacLeods of Lewis and Harris, the MacDonalds of the Uist

Uist is a group of six islands that are part of the Outer Hebridean Archipelago, which is part of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

North Uist and South Uist ( or ; ) are two of the islands and are linked by causeways running via the isles of Ben ...

s and MacNeil of Barra

Clan MacNeil, also known in Scotland as Clan Niall, is a Scottish Highlands, highland Scottish clan of Irish people, Irish origin. According to their early genealogies and some sources they're descended from Eógan mac Néill and Niall of the Ni ...

. This transition did little to relieve the islands of internecine strife although by the early 14th century the MacDonald Lords of the Isles

Lord of the Isles or King of the Isles

( or ; ) is a title of nobility in the Baronage of Scotland with historical roots that go back beyond the Kingdom of Scotland. It began with Somerled in the 12th century and thereafter the title was ...

, based on Islay

Islay ( ; , ) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll and Bute just south west of Jura, Scotland, Jura and around north of the Northern Irish coast. The island's cap ...

, were in theory these chiefs' feudal superiors and managed to exert some control.

The growing threat that Clan Donald posed to the Scottish crown led to the forcible dissolution of the Lordship of the Isles by James IV

James IV (17 March 1473 – 9 September 1513) was King of Scotland from 11 June 1488 until his death at the Battle of Flodden in 1513. He inherited the throne at the age of fifteen on the death of his father, James III, at the Battle of Sauch ...

in 1493, but although the king had the power to subdue the organised military might of the Hebrides, he and his immediate successors lacked the will or ability to provide an alternative form of governance. The House of Stuart

The House of Stuart, originally spelled Stewart, also known as the Stuart dynasty, was a dynasty, royal house of Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland and later Kingdom of Great Britain, Great ...

's attempts to control the Outer Hebrides were then at first desultory and little more than punitive expeditions. In 1506 the Earl of Huntly

Marquess of Huntly is a title in the Peerage of Scotland that was created on 17 April 1599 for George Gordon, 6th Earl of Huntly. It is the oldest existing marquessate in Scotland, and the second-oldest in the British Isles; only the English ma ...

besieged and captured Stornoway Castle using cannon. In 1540 James V

James V (10 April 1512 – 14 December 1542) was List of Scottish monarchs, King of Scotland from 9 September 1513 until his death in 1542. He was crowned on 21 September 1513 at the age of seventeen months. James was the son of King James IV a ...

himself conducted a royal tour, forcing the clan chiefs to accompany him. There followed a period of peace, but all too soon the clans were at loggerheads again.

In 1598 King James VI

James may refer to:

People

* James (given name)

* James (surname)

* James (musician), aka Faruq Mahfuz Anam James, (born 1964), Bollywood musician

* James, brother of Jesus

* King James (disambiguation), various kings named James

* Prince Ja ...

authorised some " Gentleman Adventurers" from Fife to civilise the "most barbarous Isle of Lewis". Initially successful, the colonists were driven out by local forces commanded by Murdoch and Neil MacLeod, who based their forces on in . The colonists tried again in 1605 with the same result but a third attempt in 1607 was more successful, and in due course Stornoway became a Burgh of Barony

A burgh of barony was a type of Scottish town (burgh).

Burghs of barony were distinct from royal burghs, as the title was granted to a landowner who, as a tenant-in-chief, held his estates directly from the crown. (In some cases, they might also ...

. By this time Lewis was held by the Mackenzies of Kintail, (later the Earls of Seaforth), who pursued a more enlightened approach, investing in fishing in particular. The historian W. C. MacKenzie was moved to write:

The Seaforth's royalist inclinations led to Lewis becoming garrisoned during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities in a personal union un ...

by Cromwell's troops, who destroyed the old castle in Stornoway and in 1645 Lewismen fought on the royalist side at the Battle of Auldearn

The Battle of Auldearn was an engagement of the Scotland in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, Wars of the Three Kingdoms. It took place on 9 May 1645, in and around the village of Auldearn in Nairnshire. It resulted in a victory for the royalis ...

.Thompson (1968) pp. 41–42 A new era of Hebridean involvement in the affairs of the wider world was about to commence.

British era

With the implementation of the

With the implementation of the Treaty of Union

The Treaty of Union is the name usually now given to the treaty which led to the creation of the new political state of Great Britain. The treaty, effective since 1707, brought the Kingdom of England (which already included Wales) and the Ki ...

in 1707 the Hebrides became part of the new Kingdom of Great Britain

Great Britain, also known as the Kingdom of Great Britain, was a sovereign state in Western Europe from 1707 to the end of 1800. The state was created by the 1706 Treaty of Union and ratified by the Acts of Union 1707, which united the Kingd ...

, but the clans' loyalties to a distant monarch were not strong. A considerable number of islandmen "came out" in support of the Jacobite Earl of Mar

There are currently two earldoms of Mar in the Peerage of Scotland, and the title has been created seven times. The first creation of the earldom is currently held by Margaret of Mar, 31st Countess of Mar, who is also clan chief of Clan Mar. Th ...

in the "15" although the response to the 1745 rising

The Jacobite rising of 1745 was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the Monarchy of Great Britain, British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took place during the War of the Austrian Succession, when the bulk of t ...

was muted. Nonetheless the aftermath of the decisive Battle of Culloden

The Battle of Culloden took place on 16 April 1746, near Inverness in the Scottish Highlands. A Jacobite army under Charles Edward Stuart was decisively defeated by a British government force commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, thereby endi ...

, which effectively ended Jacobite hopes of a Stuart restoration, was widely felt. The British government's strategy was to estrange the clan chiefs from their kinsmen and turn their descendants into English-speaking landlords whose main concern was the revenues their estates brought rather than the welfare of those who lived on them. This may have brought peace to the islands, but in the following century it came at a terrible price.

The Highland Clearances

The Highland Clearances ( , the "eviction of the Gaels") were the evictions of a significant number of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands, mostly in two phases from 1750 to 1860.

The first phase resulted from Scottish Agricultural R ...

of the 19th century destroyed communities throughout the Highlands and Islands

The Highlands and Islands is an area of Scotland broadly covering the Scottish Highlands, plus Orkney, Shetland, and the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles).

The Highlands and Islands are sometimes defined as the area to which the Crofters' Act o ...

as the human populations were evicted and replaced with sheep farms. For example, Colonel Gordon

Gordon may refer to:

People

* Gordon (given name), a masculine given name, including list of persons and fictional characters

* Gordon (surname), the surname

* Gordon (slave), escaped to a Union Army camp during the U.S. Civil War

* Gordon Heuck ...

of Cluny

Cluny () is a commune in the eastern French department of Saône-et-Loire, in the region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté. It is northwest of Mâcon.

The town grew up around the Benedictine Abbey of Cluny, founded by Duke William I of Aquitaine in ...

, owner of Barra, South Uist and Benbecula, evicted thousands of islanders using trickery and cruelty, and even offered to sell Barra to the government as a penal colony. Islands such as were completely cleared of their populations and even today the subject is recalled with bitterness and resentment in some areas. The position was exacerbated by the failure of the islands' kelp

Kelps are large brown algae or seaweeds that make up the order (biology), order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genus, genera. Despite its appearance and use of photosynthesis in chloroplasts, kelp is technically not a plant but a str ...

industry, which thrived from the 18th century until the end of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

in 1815 and large scale emigration became endemic. For example, hundreds left North Uist for Cape Breton

Cape Breton Island (, formerly '; or '; ) is a rugged and irregularly shaped island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18.7% of Nova Scotia's total area. Although ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia is a Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Canada, located on its east coast. It is one of the three Maritime Canada, Maritime provinces and Population of Canada by province and territory, most populous province in Atlan ...

. The pre-clearance population of the island had been almost 5,000, although by 1841 it had fallen to 3,870 and was only 2,349 by 1931.

The Highland potato famine

The Highland Potato Famine () was a period of 19th-century Scottish Highland history (1846 to roughly 1856) over which the agricultural communities of the Hebrides and the western Scottish Highlands () saw their potato crop (upon which they ha ...