The region of

Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

is part of the wider region of the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, which represents the

land bridge

In biogeography, a land bridge is an isthmus or wider land connection between otherwise separate areas, over which animals and plants are able to cross and colonize new lands. A land bridge can be created by marine regression, in which sea le ...

between

Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and

Eurasia

Eurasia ( , ) is a continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. According to some geographers, Physical geography, physiographically, Eurasia is a single supercontinent. The concept of Europe and Asia as distinct continents d ...

.

[Steiner & Killebrew, p]

9

: "The general limits ..., as defined here, begin at the Plain of 'Amuq in the north and extend south until the Wâdī al-Arish, along the northern coast of Sinai. ... The western coastline and the eastern deserts set the boundaries for the Levant ... The Euphrates and the area around Jebel el-Bishrī mark the eastern boundary of the northern Levant, as does the Syrian Desert beyond the Anti-Lebanon range's eastern hinterland and Mount Hermon. This boundary continues south in the form of the highlands and eastern desert regions of Transjordan." The areas of the Levant traditionally serve as the "crossroads of

Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, the

Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

, and

Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa, or Northeastern Africa, or Northern East Africa as it was known in the past, encompasses the countries of Africa situated in and around the Red Sea. The region is intermediate between North Africa and East Africa, and encompasses ...

",

[The Ancient Levant]

UCL Institute of Archaeology, May 2008 and in

tectonic

Tectonics ( via Latin ) are the processes that result in the structure and properties of the Earth's crust and its evolution through time. The field of ''planetary tectonics'' extends the concept to other planets and moons.

These processes ...

terms are located in the "northwest of the

Arabian Plate". Palestine itself was among the earliest regions to see human habitation, agricultural communities and

civilization

A civilization (also spelled civilisation in British English) is any complex society characterized by the development of state (polity), the state, social stratification, urban area, urbanization, and symbolic systems of communication beyon ...

. Because of its location, it has historically been seen as a crossroads for religion, culture, commerce, and politics. In the

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

, the

Canaanites

{{Cat main, Canaan

See also:

* :Ancient Israel and Judah

Ancient Levant

Hebrew Bible nations

Ancient Lebanon

0050

Ancient Syria

Wikipedia categories named after regions

0050

0050

Phoenicia

Amarna Age civilizations ...

established

city-states

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

influenced by surrounding civilizations, among them Egypt, which ruled the area in the Late Bronze Age. During the

Iron Age

The Iron Age () is the final epoch of the three historical Metal Ages, after the Chalcolithic and Bronze Age. It has also been considered as the final age of the three-age division starting with prehistory (before recorded history) and progre ...

, two related

Israelite

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

kingdoms,

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and

Judah, controlled much of Palestine, while the

Philistines

Philistines (; LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philistines origi ...

occupied its southern coast. The

Assyrians

Assyrians (, ) are an ethnic group indigenous to Mesopotamia, a geographical region in West Asia. Modern Assyrians share descent directly from the ancient Assyrians, one of the key civilizations of Mesopotamia. While they are distinct from ot ...

conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

the region in the 8th century BCE, then the

Babylonians

Babylonia (; , ) was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as an Akkadian-populated but Amorite-ru ...

, followed by the Persian

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

that conquered the Babylonian Empire in 539 BCE.

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

conquered the Persian Empire in the late 330s BCE, beginning

Hellenization

Hellenization or Hellenification is the adoption of Greek culture, religion, language, and identity by non-Greeks. In the ancient period, colonisation often led to the Hellenisation of indigenous people in the Hellenistic period, many of the ...

.

In the late 2nd-century BCE

Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

, the Jewish

Hasmonean Kingdom

The Hasmonean dynasty (; ''Ḥašmōnāʾīm''; ) was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during the Hellenistic times of the Second Temple period (part of classical antiquity), from BC to 37 BC. Between and BC the dynasty rule ...

conquered most of Palestine; the kingdom subsequently became a vassal of

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, which annexed it in 63 BCE.

Roman Judea was troubled by

Jewish revolts in 66 CE, so Rome

destroyed Jerusalem and the

Second Jewish Temple in 70 CE. In the 4th century, as the

Roman Empire adopted Christianity, Palestine became a center for the religion, attracting pilgrims, monks and scholars. Following

Muslim conquest of the Levant

The Muslim conquest of the Levant (; ), or Arab conquest of Syria, was a 634–638 CE invasion of Byzantine Syria by the Rashidun Caliphate. A part of the wider Arab–Byzantine wars, the Levant was brought under Arab Muslim rule and develope ...

in 636–641, ruling dynasties succeeded each other: the

Rashiduns

The Rashidun () are the first four caliphs () who led the Ummah, Muslim community following the death of Muhammad: Abu Bakr (), Umar (), Uthman (), and Ali ().

The reign of these caliphs, called the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661), is considere ...

;

Umayyads,

Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 CE), from whom the dynasty takes i ...

; the semi-independent

Tulunids

The Tulunid State, also known as the Tulunid Emirate or The State of Banu Tulun, and popularly referred to as the Tulunids () was a Mamluk dynasty of Turkic peoples, Turkic origin who was the first independent dynasty to rule Egypt in the Middle ...

and

Ikhshidids;

Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate (; ), also known as the Fatimid Empire, was a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries CE under the rule of the Fatimid dynasty, Fatimids, an Isma'ili Shi'a dynasty. Spanning a large area of North Africa ...

; and the

Seljuks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; , ''Saljuqian'',) alternatively spelled as Saljuqids or Seljuk Turks, was an Oghuz Turkic, Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate and contributed to Turco-Persian culture.

The founder of th ...

. In 1099, the

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the Middle Ages. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Muslim conquest ...

resulted in

Crusaders

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding ...

establishing of the

Kingdom of Jerusalem

The Kingdom of Jerusalem, also known as the Crusader Kingdom, was one of the Crusader states established in the Levant immediately after the First Crusade. It lasted for almost two hundred years, from the accession of Godfrey of Bouillon in 1 ...

, which was

reconquered by the

Ayyubid Sultanate

The Ayyubid dynasty (), also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultan of Egypt, Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate, Fatimid Caliphate of Egyp ...

in 1187. Following the

invasion

An invasion is a Offensive (military), military offensive of combatants of one geopolitics, geopolitical Legal entity, entity, usually in large numbers, entering territory (country subdivision), territory controlled by another similar entity, ...

of the

Mongol Empire

The Mongol Empire was the List of largest empires, largest contiguous empire in human history, history. Originating in present-day Mongolia in East Asia, the Mongol Empire at its height stretched from the Sea of Japan to parts of Eastern Euro ...

in the late 1250s, the Egyptian

Mamluks

Mamluk or Mamaluk (; (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural); translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave") were non-Arab, ethnically diverse (mostly Turkic, Caucasian, Eastern and Southeastern European) enslaved mercenaries, slave-sold ...

reunified Palestine under its control, before the region was

conquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

by the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

in 1516, being ruled as

Ottoman Syria

Ottoman Syria () is a historiographical term used to describe the group of divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the region of the Levant, usually defined as being east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Ara ...

until the 20th century largely without dispute.

During

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, the British government issued the

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

, favoring the establishment of a

homeland for the Jewish people in Palestine, and

captured it from the Ottomans. The

League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

gave Britain

mandatory power over Palestine in 1922. British rule and Arab efforts to prevent Jewish migration led to growing

violence between Arabs and Jews, causing the British to announce

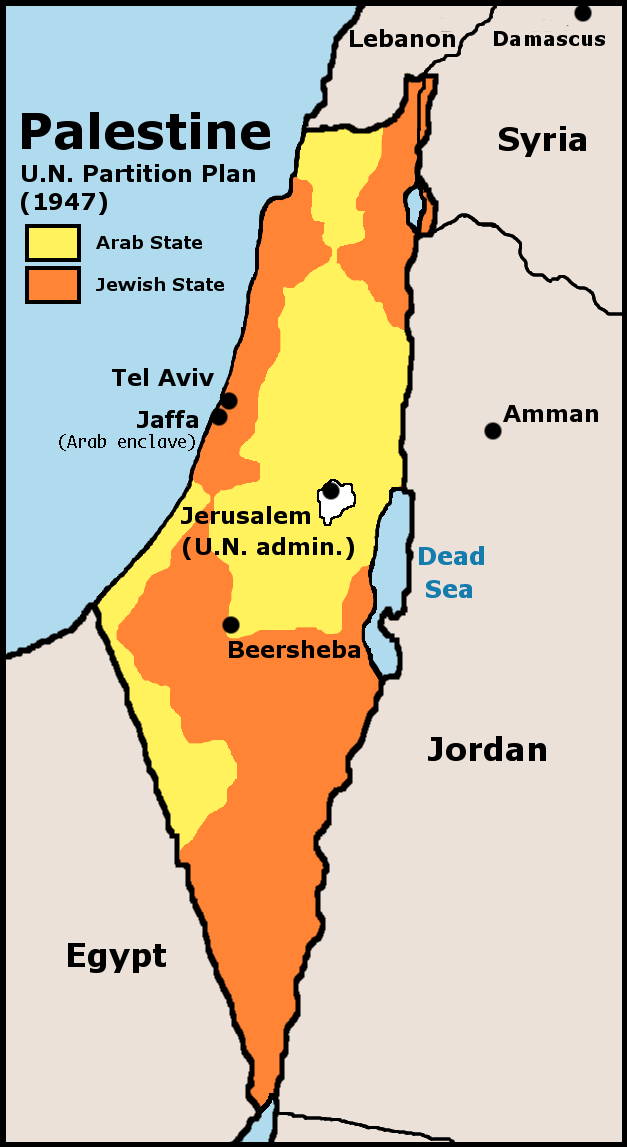

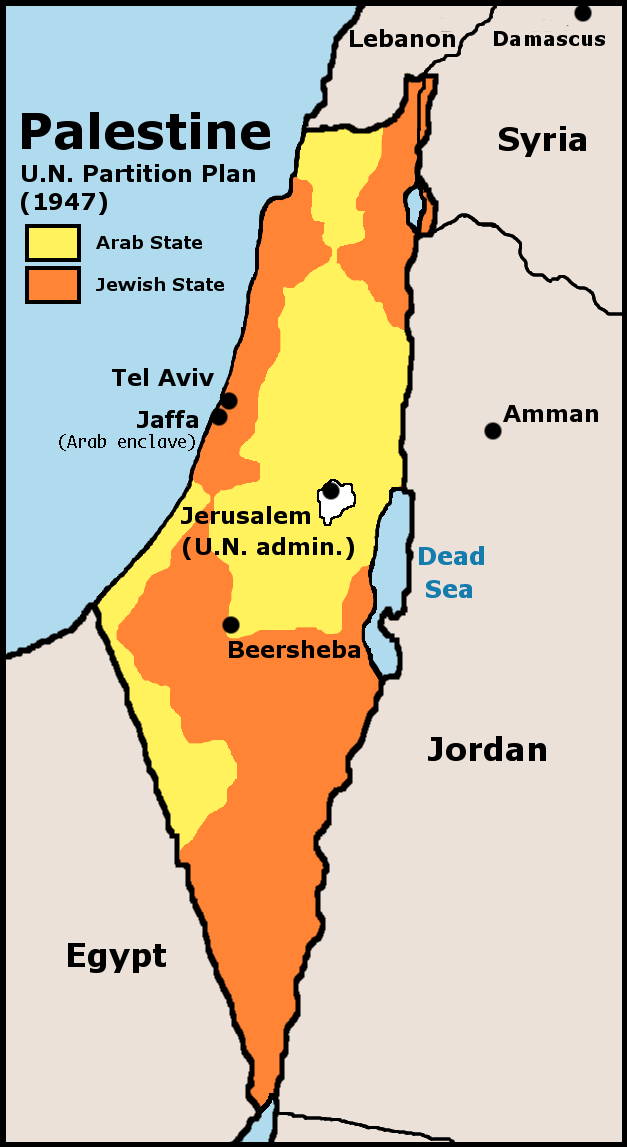

its intention to terminate the Mandate in 1947. The

UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; , AGNU or AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as its main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ. Currently in its 79th session, its powers, ...

recommended

partitioning Palestine into two states: Arab and Jewish. However, the situation deteriorated into a

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. The Arabs rejected the Partition Plan, the Jews

ostensibly accepted it, declaring the independence of the

State of Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

in May 1948 upon the

end of the British mandate. Nearby Arab countries invaded Palestine, Israel not only prevailed, but conquered more territory than envisioned by the Partition Plan. During the war, 700,000, or about 80% of all Palestinians

fled or were driven out of territory Israel conquered and were not allowed to return, an event known as the

Nakba

The Nakba () is the ethnic cleansing; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; of Palestinian Arabs through their violent displacement and dispossession of land, property, and belongings, along with the destruction of their s ...

(Arabic for 'catastrophe') to Palestinians. Starting in the late 1940s and continuing for decades,

about 850,000 Jews from the Arab world immigrated ("made

Aliyah

''Aliyah'' (, ; ''ʿălīyyā'', ) is the immigration of Jews from Jewish diaspora, the diaspora to, historically, the geographical Land of Israel or the Palestine (region), Palestine region, which is today chiefly represented by the Israel ...

") to Israel.

After the war, only two parts of Palestine remained in Arab control: the

West Bank

The West Bank is located on the western bank of the Jordan River and is the larger of the two Palestinian territories (the other being the Gaza Strip) that make up the State of Palestine. A landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and

East Jerusalem

East Jerusalem (, ; , ) is the portion of Jerusalem that was Jordanian annexation of the West Bank, held by Jordan after the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, as opposed to West Jerusalem, which was held by Israel. Captured and occupied in 1967, th ...

were

annexed by Jordan, and the

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

was

occupied by Egypt, which were conquered by Israel during the

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

in 1967. Despite international objections, Israel started to establish

settlements in these occupied territories. Meanwhile, the Palestinian national movement gained international recognition, thanks to the

Palestine Liberation Organisation

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ) is a Palestinian nationalist coalition that is internationally recognized as the official representative of the Palestinian people in both the occupied Palestinian territories and the diaspora. ...

(PLO), under

Yasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

. In 1993, the

Oslo Peace Accords

The Oslo I Accord or Oslo I, officially called the Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Government Arrangements or short Declaration of Principles (DOP), was an attempt in 1993 to set up a framework that would lead to the resolution of th ...

between Israel and the PLO established the

Palestinian Authority

The Palestinian Authority (PA), officially known as the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), is the Fatah-controlled government body that exercises partial civil control over the Palestinian enclaves in the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, ...

(PA), an interim body to run Gaza and the West Bank (but not East Jerusalem), pending a permanent solution. Further peace developments were not ratified and/or implemented, and relations between Israel and Palestinians has been marked by conflict, especially with Islamist

Hamas

The Islamic Resistance Movement, abbreviated Hamas (the Arabic acronym from ), is a Palestinian nationalist Sunni Islam, Sunni Islamism, Islamist political organisation with a military wing, the Qassam Brigades. It has Gaza Strip under Hama ...

, which rejects the PA. In 2007, Hamas

won control of Gaza from the PA, now limited to the West Bank. In 2012, the

State of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

(the name used by the PA) became a non-member observer state in the

UN, allowing it to take part in General Assembly debates and improving its chances of joining other UN agencies.

Prehistory

The earliest human remains in the region were found in

Ubeidiya, south of the

Sea of Galilee

The Sea of Galilee (, Judeo-Aramaic languages, Judeo-Aramaic: יַמּא דטבריא, גִּנֵּיסַר, ), also called Lake Tiberias, Genezareth Lake or Kinneret, is a freshwater lake in Israel. It is the lowest freshwater lake on Earth ...

, in the

Jordan Rift Valley

The Jordan Rift Valley, also Jordan Valley ( ''Bīqʿāt haYardēn'', Al-Ghor or Al-Ghawr), is an elongated endorheic basin located in modern-day Israel, Jordan and the West Bank, Palestine. This geographic region includes the entire length o ...

. The remains are dated to the

Pleistocene

The Pleistocene ( ; referred to colloquially as the ''ice age, Ice Age'') is the geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from to 11,700 years ago, spanning the Earth's most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change was fin ...

, c. 1.5 million years ago. These are traces of the

earliest migration of ''

Homo erectus

''Homo erectus'' ( ) is an extinction, extinct species of Homo, archaic human from the Pleistocene, spanning nearly 2 million years. It is the first human species to evolve a humanlike body plan and human gait, gait, to early expansions of h ...

'' out of Africa.

Excavations in

Skhul Cave

Es-Skhul (es-Skhūl, Hebrew language, Hebrew: מערת סחול; ; meaning ''kid'', ''young goat'') or the Skhul Cave is a prehistoric cave site situated about south of the city of Haifa, Israel, and about from the Mediterranean Sea.

Together ...

revealed the first evidence of the late Epipalaeolithic

Natufian

The Natufian culture ( ) is an archaeological culture of the late Epipalaeolithic Near East in West Asia from 15–11,500 Before Present. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentism, sedentary or semi-sedentary population even befor ...

culture, characterized by the presence of abundant

microliths

A microlith is a small Rock (geology), stone tool usually made of flint or chert and typically a centimetre or so in length and half a centimetre wide. They were made by humans from around 60,000 years ago, across Europe, Africa, Asia and Austral ...

, human burials and ground stone tools. This also represents one area where

Neanderthal

Neanderthals ( ; ''Homo neanderthalensis'' or sometimes ''H. sapiens neanderthalensis'') are an extinction, extinct group of archaic humans who inhabited Europe and Western and Central Asia during the Middle Pleistocene, Middle to Late Plei ...

spresent in the region between 200,000 and 45,000 years agolived alongside modern humans dating to 100,000 years ago. In the caves of

Shuqba

Shuqba () is a Palestinian town in the Ramallah and al-Bireh Governorate, located 17 kilometers northwest of the city of Ramallah in Palestinian National Authority, Palestine.

Shuqba has a total area of , and the built-up area comprises . Shuqba ...

near

Ramallah

Ramallah ( , ; ) is a Palestinians, Palestinian city in the central West Bank, that serves as the administrative capital of the State of Palestine. It is situated on the Judaean Mountains, north of Jerusalem, at an average elevation of abov ...

and

Wadi Khareitun near

Bethlehem

Bethlehem is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, located about south of Jerusalem, and the capital of the Bethlehem Governorate. It had a population of people, as of . The city's economy is strongly linked to Tourism in the State of Palesti ...

, tools were found and attributed to the

Natufian

The Natufian culture ( ) is an archaeological culture of the late Epipalaeolithic Near East in West Asia from 15–11,500 Before Present. The culture was unusual in that it supported a sedentism, sedentary or semi-sedentary population even befor ...

culture (c. 2,800–10,300 BCE). Other remains from this era have been found at Tel Abu Hureura, Ein Mallaha, Beidha and

Jericho

Jericho ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and the capital of the Jericho Governorate. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It had a population of 20,907 in 2017.

F ...

.

Between 10,000 and 5000 BCE, agricultural communities were established. Evidence of such settlements were found at Tel es-Sultan in Jericho and consisted of a number of walls, a religious shrine, and a tower with an internal staircase Jericho is believed to be one of the

oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, with evidence of settlement dating back to 9000 BCE. Along the Jericho–

Dead Sea

The Dead Sea (; or ; ), also known by #Names, other names, is a landlocked salt lake bordered by Jordan to the east, the Israeli-occupied West Bank to the west and Israel to the southwest. It lies in the endorheic basin of the Jordan Rift Valle ...

–

Bir es-Saba–

Gaza–

Sinai route, a culture originating in

Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, marked by the use of copper and stone tools, brought new migrant groups to the region contributing to an increasingly urban fabric.

Bronze and Iron Ages (3700–539 BCE)

Emergence of cities

In the Early Bronze Age (c. 3700–2500 BCE) period, the earliest formation of urban societies and cultures emerged in the region. The period is defined through archaeology, as it is absent from any historical record either from Palestine or contemporary Egyptian and Mesopotamian sources. It follows the demise of the

Ghassulian

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle and Late Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant (c. 4400 – c. 3500 BC). Its type-site, Teleilat el-Ghassul, is located in the eastern Jordan Valley near ...

village-culture of the late

Chalcolithic

The Chalcolithic ( ) (also called the Copper Age and Eneolithic) was an archaeological period characterized by the increasing use of smelted copper. It followed the Neolithic and preceded the Bronze Age. It occurred at different periods in di ...

period. It begins in a period of around 600 years of a stable rural society, economically based on a Mediterranean agriculture and with a slow growth in population. This period has been termed the Early Bronze Age I (), parallel to the

Late Uruk period of

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

and the pre-dynastic

Naqada culture

The Naqada culture is an archaeological culture of Chalcolithic Predynastic Egypt (c. 4000–3000 BC), named for the town of Naqada, Qena Governorate. A 2013 Oxford University radiocarbon dating study of the Predynastic period suggests a beginn ...

of

Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. The construction of several temple-like structures in that period attests to the accumulation of social power. Evidence of contact and immigration to

Lower Egypt

Lower Egypt ( ') is the northernmost region of Egypt, which consists of the fertile Nile Delta between Upper Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea, from El Aiyat, south of modern-day Cairo, and Dahshur. Historically, the Nile River split into sev ...

is found in the abundance of pottery vessels of southern–Levantine type, found in sites across the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

, such as

Abydos. During the last two hundred years of that period and following the

unification of Egypt and pharaoh

Narmer

Narmer (, may mean "painful catfish", "stinging catfish", "harsh catfish", or "fierce catfish"; ) was an ancient Egyptian king of the Early Dynastic Period, whose reign began at the end of the 4th millennium BC. He was the successor to the Prot ...

, an Egyptian colony appeared in the southern Levantine coast, with its center at

Tell es-Sakan (modern-day

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip, also known simply as Gaza, is a small territory located on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea; it is the smaller of the two Palestinian territories, the other being the West Bank, that make up the State of Palestine. I ...

). The overall nature of this colony as well as its relation with the hinterlands has been debated by archaeologists. The archaeologists who led the excavations at Tell es-Sakan,

Pierre de Miroschedji and

Moain Sadeq, suggest that Egyptian activity in the southern Levant can be divided into three areas: a core of permanent settlement in the south, a periphery of seasonal settlement extending north along the coast, and an area beyond this extending north and east where Egyptian culture interacted with local culture. Located in the area of permanent Egyptian settlement, Tell es-Sakan was likely an administrative centre.

Around 3100 BCE, the region saw radical change, with the abandonment and destruction of many settlements, including the Egyptian colony. These were quickly replaced by new walled settlements in plains and coastal regions, surrounded by mud-brick fortifications and reliant on nearby agricultural hamlets for their food.

The Canaanite city-states held trade and diplomatic relations with Egypt and Syria. Parts of the Canaanite urban civilization were destroyed around 2500 BCE, though there is no consensus as to why (for one theory, see

4.2-kiloyear event). Incursions by nomads from the east of the

Jordan River

The Jordan River or River Jordan (, ''Nahr al-ʾUrdunn''; , ''Nəhar hayYardēn''), also known as ''Nahr Al-Sharieat'' (), is a endorheic river in the Levant that flows roughly north to south through the Sea of Galilee and drains to the Dead ...

who settled in the hills followed soon thereafter, as well as cultural influence from the ancient Syrian city of

Ebla

Ebla (Sumerian language, Sumerian: ''eb₂-la'', , modern: , Tell Mardikh) was one of the earliest kingdoms in Syria. Its remains constitute a Tell (archaeology), tell located about southwest of Aleppo near the village of Mardikh. Ebla was ...

. That period known as the

Intermediate Bronze Age (2500–2000 BCE), was defined recently out of the tail of the Early Bronze Age and the head of the preceding Middle Bronze Age. Others date the destruction to the end of Early Bronze Age III (c. 2350/2300 BCE) and attribute it to Syrian

Amorites

The Amorites () were an ancient Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic-speaking Bronze Age people from the Levant. Initially appearing in Sumerian records c. 2500 BC, they expanded and ruled most of the Levant, Mesopotamia and parts of Eg ...

,

Kurgans, southern nomads

or internal conflicts within Canaan.

In the

Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

(2000–1500 BCE), Canaan was influenced by the surrounding civilizations of ancient Egypt,

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

,

Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

,

Minoan

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and Minoan art, energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan pa ...

Crete, and Syria. Diverse commercial ties and an agriculturally based economy led to the development of new pottery forms, the cultivation of grapes, and the extensive use of bronze. Burial customs from this time seemed to be influenced by a belief in the afterlife. The

Middle Kingdom Egyptian

Execration Texts

Execration texts, also referred to as proscription lists, are ancient Egyptian hieratic texts, listing enemies of the pharaoh, most often enemies of the Egyptian state or troublesome foreign neighbors. The texts were most often written upon stat ...

attest to Canaanite trade with Egypt during this period. The Minoan influence is apparent at

Tel Kabri

Tel Kabri (), or Tell al-Qahweh (), is an archaeological Tell (archaeology), tell (mound created by accumulation of remains) containing one of the largest Bronze Age, Middle Bronze Age (2,100–1,550 Common Era, BCE) Canaanite palaces in Israel ...

.

A DNA analysis published in May 2020 showed that migrants from the

Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

mixed with the local population to produce the Canaanite culture that existed during the Bronze Age.

Egyptian dominance

Between 1550 and 1400 BCE, the Canaanite city-states became vassals to the

New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also called the Egyptian Empire, refers to ancient Egypt between the 16th century BC and the 11th century BC. This period of History of ancient Egypt, ancient Egyptian history covers the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth, ...

. Political, commercial and military events towards the end of this period (1450–1350 BCE) were recorded by ambassadors and Canaanite proxy rulers for Egypt in 379 cuneiform tablets known as the

Amarna Letters. These refer to local chieftains, such as

Biridiya

Biridiya was the ruler of Megiddo, northern part of the southern Levant, in the 14th century BC. At the time Megiddo was a city-state submitting to the Egyptian Empire. He is part of the intrigues surrounding the rebel Labaya of Shechem.

History ...

of

Megiddo Megiddo may refer to:

Places and sites in Israel

* Tel Megiddo, site of an ancient city in Israel's Jezreel valley

* Megiddo Airport, a domestic airport in Israel

* Megiddo church (Israel)

* Megiddo, Israel, a kibbutz in Israel

* Megiddo Juncti ...

,

Lib'ayu of

Shechem

Shechem ( ; , ; ), also spelled Sichem ( ; ) and other variants, was an ancient city in the southern Levant. Mentioned as a Canaanite city in the Amarna Letters, it later appears in the Hebrew Bible as the first capital of the Kingdom of Israe ...

and

Abdi-Heba

Abdi-Ḫeba (Abdi-Kheba, Abdi-Ḫepat, or Abdi-Ḫebat) was a local chieftain of History of Jerusalem, Jerusalem during the Amarna period (mid-1330s BC). Ancient Egypt, Egyptian documents have him deny he was a mayor (''ḫazānu'') and assert he ...

in

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

. Abdi-Heba is a

Hurrian

The Hurrians (; ; also called Hari, Khurrites, Hourri, Churri, Hurri) were a people who inhabited the Ancient Near East during the Bronze Age. They spoke the Hurro-Urartian language, Hurrian language, and lived throughout northern Syria (region) ...

name, and enough Hurrians lived in Canaan at that time to warrant contemporary Egyptian texts naming the locals as ''Ḫurru''.

In the first year of his reign, the pharaoh

Seti I

Menmaatre Seti I (or Sethos I in Greek language, Greek) was the second pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt during the New Kingdom of Egypt, New Kingdom period, ruling or 1290 BC to 1279 BC. He was the son of Ramesses I and Sitre, and th ...

() waged a campaign to re-subordinate Canaan to Egyptian rule, thrusting north as far as

Beit She'an

Beit She'an ( '), also known as Beisan ( '), or Beth-shean, is a town in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. The town lies at the Beit She'an Valley about 120 m (394 feet) below sea level.

Beit She'an is believed to ...

, and installing local vassals to administer the area in his name. The

Egyptian Stelae in the Levant, most notably the

Beisan steles, and a burial site yielding a

scarab bearing the name Seti found within a Canaanite coffin excavated in the

Jezreel Valley

The Jezreel Valley (from the ), or Marj Ibn Amir (), also known as the Valley of Megiddo, is a large fertile plain and inland valley in the Northern District (Israel), Northern District of Israel. It is bordered to the north by the highlands o ...

, attests to Egypt's presence in the area.

Late Bronze Age collapse

The

Late Bronze Age collapse

The Late Bronze Age collapse was a period of societal collapse in the Mediterranean basin during the 12th century BC. It is thought to have affected much of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East, in particular Egypt, Anatolia, the Aegea ...

had greatly affected the Ancient Near East, including Canaan. The Egyptians withdrew from the area. Layers of destruction from the crisis period were found in several sites, including

Hazor, Beit She'an,

Megiddo Megiddo may refer to:

Places and sites in Israel

* Tel Megiddo, site of an ancient city in Israel's Jezreel valley

* Megiddo Airport, a domestic airport in Israel

* Megiddo church (Israel)

* Megiddo, Israel, a kibbutz in Israel

* Megiddo Juncti ...

,

Lachish

Lachish (; ; ) was an ancient Canaanite and later Israelite city in the Shephelah ("lowlands of Judea") region of Canaan on the south bank of the Lakhish River mentioned several times in the Hebrew Bible. The current '' tell'' by that name, kn ...

,

Ekron

Ekron (Philistine: 𐤏𐤒𐤓𐤍 ''*ʿAqārān'', , ), in the Hellenistic period known as Accaron () was at first a Canaanite, and later more famously a Philistine city, one of the five cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, located in pr ...

,

Ashdod

Ashdod (, ; , , or ; Philistine language, Philistine: , romanized: *''ʾašdūd'') is the List of Israeli cities, sixth-largest city in Israel. Located in the country's Southern District (Israel), Southern District, it lies on the Mediterranean ...

and

Ashkelon

Ashkelon ( ; , ; ) or Ashqelon, is a coastal city in the Southern District (Israel), Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border with the Gaza Strip.

The modern city i ...

. The layers of destruction in Lachish and Megiddo date back to about 1130 BCE, More than a hundred years after the destruction of Hazor circa 1250 BCE, and point to a prolonged period of decline in local civilization.

Beginning in the late 13th century and continuing to the early 11th century, hundreds of smaller, unprotected village settlements were founded in Canaan, many in the mountainous regions. In some of them, the characteristics identified in a later period with the inhabitants of Israel and Judah, such as the

four-room house, appear for the first time. The number of villages reduced in the 11th century, counterbalanced by other settlements reaching the status of fortified townships.

Early Israelites and Philistines

After the withdrawal of the Egyptians, Canaan became home to the Israelites and the

Philistines

Philistines (; LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philistines origi ...

. The Israelites

settled the central highlands, a loosely defined highland region stretching from the

Judean hills

The Judaean Mountains, or Judaean Hills (, or ,) are a mountain range in the West Bank and Israel where Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Hebron and several other biblical sites are located. The mountains reach a height of . The Judean Mountains can be div ...

in the south to the

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

n hills in the north. Based on the archaeological evidence, they did not overtake the region by force, but instead branched out of the indigenous Canaanite peoples.

During the 12th century BCE, the

Philistines

Philistines (; LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philistines origi ...

, who had immigrated from the

Aegean region

The Aegean region () is one of the 7 Geographical regions of Turkey, geographical regions of Turkey. The largest city in the region is İzmir. Other big cities are Manisa, Aydın, Denizli, Muğla, Afyonkarahisar and Kütahya.

Located in w ...

, settled in the southern coast of Palestine. Traces of Philistines appeared at about the same time as the Israelites. The Philistines are credited with introducing iron weapons, chariots, and new ways of fermenting wine to the local population. Over time, the Philistines integrated with the local population and they, like other people in Palestine, were engulfed by first the Assyrian empire and later the Babylonian empire. In the 6th century, they disappeared from written history.

Kingdoms of Israel and Judah

Two related Israelite kingdoms,

Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

and

Judah, emerged during the 10th and 9th centuries BCE: Israel in the north and Judah in the south. Israel was the more prosperous of the kingdoms and developed into a regional power. By the 8th century BCE, the Israelite population had grown to some 160,000 individuals over 500 settlements.

Israel and Judah continually clashed with the kingdoms of

Ammon

Ammon (; Ammonite language, Ammonite: 𐤏𐤌𐤍 ''ʻAmān''; '; ) was an ancient Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking kingdom occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Wadi Mujib, Arnon and Jabbok, in present-d ...

,

Edom

Edom (; Edomite language, Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian language, Akkadian: , ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomi ...

and

Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

, located in modern-day Jordan, and with the kingdom of

Aram-Damascus

Aram-Damascus ( ) was an Arameans, Aramean polity that existed from the late-12th century BCE until 732 BCE, and was centred around the city of Damascus in the Southern Levant. Alongside various tribal lands, it was bounded in its later years b ...

, located in modern-day Syria. The northwestern region of the Transjordan, known then as

Gilead

Gilead or Gilad (, ; ''Gilʿāḏ'', , ''Jalʻād'') is the ancient, historic, biblical name of the mountainous northern part of the region of Transjordan.''Easton's Bible Dictionary'Galeed''/ref> The region is bounded in the west by the J ...

, was also settled by the

Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

.

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

flourished as a spoken language in the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah during the period from to 586 BCE.

The

Omride dynasty greatly expanded the northern kingdom of Israel. In the mid-9th century, it stretched from the vicinity of

Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

in the north to the territory of

Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

in the south, ruling over a large number of non-Israelites. In 853 BCE, the Israelite king

Ahab

Ahab (; ; ; ; ) was a king of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), the son and successor of King Omri, and the husband of Jezebel of Sidon, according to the Hebrew Bible. He is depicted in the Bible as a Baal worshipper and is criticized for causi ...

led a coalition of anti-Assyrian forces at the

Battle of Qarqar

The Battle of Qarqar (or Ḳarḳar) was fought in 853 BC when the army of the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Emperor Shalmaneser III encountered an allied army of eleven kings at Qarqar led by Hadadezer, called in Assyrian ''Adad-idir'' and possib ...

that repelled an invasion by King

Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''Šulmānu-ašarēdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 859 BC to 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campaigns against the eastern tribes, the Babylonians, the nations o ...

of Assyria. Some years later, King

Mesha

King Mesha (Moabite language, Moabite: , vocalized as: ; Hebrew: מֵישַׁע ''Mēšaʿ'') was a king of Moab in the 9th century BC, known most famously for having the Mesha Stele inscribed and erected at Dhiban, Dibon, Jordan. In this inscrip ...

of Moab, a vassal of Israel, rebelled against it, destroying the main Israelite settlements in the Transjordan.

In the 830s BCE, king

Hazael

Hazael (; ; Old Aramaic 𐤇𐤆𐤀𐤋 ''Ḥzʔl'') was a king of Aram-Damascus mentioned in the Bible. Under his reign, Aram-Damascus became an empire that ruled over large parts of contemporary Syria and Israel-Samaria. While he was likely ...

of Aram Damascus conquered the fertile and strategically important northern parts of Israel which devastated the kingdom. He also destroyed the Philistine city of

Gath. During the late 9th century BCE, Israel under King

Jehu

Jehu (; , meaning "Jah, Yah is He"; ''Ya'úa'' 'ia-ú-a'' ) was the tenth king of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), northern Kingdom of Israel since Jeroboam I, noted for exterminating the house of Ahab. He was the son of Jehoshaphat (father ...

became a vassal to Assyria.

Assyrian invasions

King

Tiglath Pileser III of Assyria was discontent with the empire's system of vassal states and set to control them more directly or even turn then into Assyrian provinces. Tiglath Pileser and his successors conquered Palestine beginning in 734 BCE to about 645 BCE. This policy had lasting consequences for Palestine as its strongest kingdoms were crushed, inflicting heavy damage, and parts of the kingdoms' populations were deported.

The Kingdom of Israel was eradicated in 720 BCE as its capital,

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, fell to the Assyrians. The records of

Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

indicate that he deported 27,290 inhabitants of the kingdom to northern Mesopotamia. Many Israelites migrated to the southern kingdom of Judah. When

Hezekiah

Hezekiah (; ), or Ezekias (born , sole ruler ), was the son of Ahaz and the thirteenth king of Kingdom of Judah, Judah according to the Hebrew Bible.Stephen L Harris, Harris, Stephen L., ''Understanding the Bible''. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. "G ...

rose to power in Judah in 715 BCE, he forged an alliance with Egypt and Ashkelon, and revolted against the Assyrians by refusing to pay tribute. In 701 BCE,

Sennacherib laid siege to Jerusalem, though the city was never taken.

The Assyrian expansion continued southward, taking

Thebes in 664 BCE. The kingdom of Judah, along with a line of city-states on the coastal plain were allowed to remain independent; from an Assyrian standpoint, they were weak and nonthreatening.

Babylonian period

Struggles over succession following the death of King

Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

in 631 BCE weakened the Assyrian empire. This allowed

Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

to revolt and to eventually conquer most of Assyria's territory. Meanwhile, Egypt reasserted its power and created a system of vassal states in the region that were obliged to pay taxes in exchange for military protection.

In 616 BCE, Egypt sent its armies north to intervene on behalf of the fading Assyrian empire against the Babylonian threat. The intervention was unsuccessful; Babylon took Assyria's

Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

in 612 BCE and two years later

Harran

Harran is a municipality and Districts of Turkey, district of Şanlıurfa Province, Turkey. Its area is 904 km2, and its population is 96,072 (2022). It is approximately southeast of Urfa and from the Syrian border crossing at Akçakale.

...

. In 609 the Egyptian pharaoh

Necho II

Necho II (sometimes Nekau, Neku, Nechoh, or Nikuu; Greek: Νεκώς Β'; ) of Egypt was a king of the 26th Dynasty (610–595 BC), which ruled from Sais. Necho undertook a number of construction projects across his kingdom. In his reign, accor ...

again marched north with his army. He executed the Judahite king

Josiah

Josiah () or Yoshiyahu was the 16th king of Judah (–609 BCE). According to the Hebrew Bible, he instituted major religious reforms by removing official worship of gods other than Yahweh. Until the 1990s, the biblical description of Josiah’s ...

at the Egyptian base

Megiddo Megiddo may refer to:

Places and sites in Israel

* Tel Megiddo, site of an ancient city in Israel's Jezreel valley

* Megiddo Airport, a domestic airport in Israel

* Megiddo church (Israel)

* Megiddo, Israel, a kibbutz in Israel

* Megiddo Juncti ...

and a few months later he installed

Jehoiakim

Jehoiakim, also sometimes spelled Jehoikim was the eighteenth and antepenultimate King of Judah from 609 to 598 BC. He was the second son of King Josiah () and Zebidah, the daughter of Pedaiah of Rumah. His birth name was Eliakim.

Background

Af ...

as the king of Judah. At the

Battle of Carchemish

The Battle of Carchemish was a battle fought around 605 BCE between the armies of Egypt, allied with the remnants of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, against the armies of Babylonia. The forces would clash at Carchemish, an important military crossing a ...

in 605 BCE, the Babylonians routed the Egyptian forces, causing them to flee back to the

Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

. By 601 BCE, all the former states in the Levant had become Babylonian colonies.

The Babylonians continued the practices of their predecessors the Assyrians and deported populations that resisted its military might. Many of them were settled in Babylon and were used to rebuild the country which had been devastated through the long years of conflict with the Assyrians.

In 601 BCE Nebuchadnezzar launched a failed invasion of Egypt which forced him to withdraw to Babylon to rebuild his army. This failure was interpreted as a sign of weakness, causing some vassal states to defect, among them Judah, leading to the

Judahite–Babylonian War. Nebuchadnezzar responded by

laying siege to Jerusalem in 598 to end its revolt. In 597, the king

Jeconiah

Jeconiah ( meaning "Yahweh has established"; ; ), also known as Coniah and as Jehoiachin ( ''Yəhoyāḵin'' ; ), was the nineteenth and penultimate king of Judah who was dethroned by the King of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE ...

of Judah, together with Jerusalem's aristocracy and priesthood, were deported to Babylon.

In 587 BCE, Nebuchadnezzar

besieged and destroyed Jerusalem, bringing an end to the kingdom of Judah. A large number of Judahites were

exiled to Babylon. Judah and the Philistine city-states of Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, and Ekron, were dissolved and incorporated into the

Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC a ...

as provinces. Judah became the province of

Yehud Yehud may refer to:

* Yehud, the Levantine province of the Neo-Babylonian Empire

* Yehud Medinata, the Levantine province of the Achaemenid Persian Empire

* Yehud, the modern-day Israeli city

See also

*Yahud (disambiguation)

*Yehudi (disambiguatio ...

, a Jewish administrative division of the Neo-Babylonian Empire.

Achaemenid period

Following

Cyrus the Great

Cyrus II of Persia ( ; 530 BC), commonly known as Cyrus the Great, was the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. Achaemenid dynasty (i. The clan and dynasty) Hailing from Persis, he brought the Achaemenid dynasty to power by defeating the Media ...

's

conquest of Babylon in 539 BCE, Palestine became part of the Persian

Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. At least five Persian provinces existed in the region:

Yehud Medinata

Yehud Medinata, also called Yehud Medinta ( ) or simply Yehud, was an autonomous province of the Achaemenid Empire. Located in Judea, the territory was distinctly Jews, Jewish, with the High Priest of Israel emerging as a central religious and ...

, Samaria, Gaza, Ashdod, and Ascalon. The

Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n city-states continued to prosper in present-day Lebanon, while the Arabian tribes inhabited the southern deserts.

In contrast to his predecessors, who controlled conquered populations using mass deportations, Cyrus issued a

proclamation

A proclamation (Lat. ''proclamare'', to make public by announcement) is an official declaration issued by a person of authority to make certain announcements known. Proclamations are currently used within the governing framework of some nations ...

granting subjugated nations religious freedom. The Persians resettled exiles in their homelands and let them rebuilt their temples. According to scholars, this policy helped them to present themselves as liberators, gaining them the goodwill of the people.

In 538 BCE, the Persians allowed the

return of exiled Judeans to Jerusalem. The Judeans, who came to be known as

Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, settled in what became known as

Yehud Medinata

Yehud Medinata, also called Yehud Medinta ( ) or simply Yehud, was an autonomous province of the Achaemenid Empire. Located in Judea, the territory was distinctly Jews, Jewish, with the High Priest of Israel emerging as a central religious and ...

or Yehud, a self-governing Jewish province under Persian rule. The

First Temple

Solomon's Temple, also known as the First Temple (), was a biblical Temple in Jerusalem believed to have existed between the 10th and 6th centuries BCE. Its description is largely based on narratives in the Hebrew Bible, in which it was commis ...

in Jerusalem, which had been destroyed by the Babylonians, Second Temple, was rebuilt under the auspices of the returned Jewish population.

Major religious transformations took place in Yehud Medinata. it was during that period that the Yahwism, Israelite religion became exclusively monotheisticthe existence of other Gods was now denied. Previously, Yahweh, Israel's national god, had been seen as one god among many. Many customs and behavior that would come to characterize Judaism were adopted.

The region of Samaria was inhabited by the Samaritans, an ethno-religious group who worship Yahweh, like the Jews, and who claim descent from the original Israelites. The Samaritan temple cult, centered around Mount Gerizim, competed with the Jews' temple cult centered around Moriah, Mount Moriah in Jerusalem and led to long-lasting animosity between the two groups. Remnants of their temple at Mount Gerizim near

Shechem

Shechem ( ; , ; ), also spelled Sichem ( ; ) and other variants, was an ancient city in the southern Levant. Mentioned as a Canaanite city in the Amarna Letters, it later appears in the Hebrew Bible as the first capital of the Kingdom of Israe ...

dates to the 5th century.

Another people in Palestine was the Edomites. Originally, their kingdom occupied the southern area of modern-day Jordan but later they were pushed westward by nomadic tribes coming from the east, among them the Nabataeans, and therefore migrated into southern parts of Judea. This migration had already begun a generation or two before the Babylonian conquest of Judah, but as Judah was weakened the pace accelerated. Their territory became known as Idumea.

Around the turn of the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, the Persians gave the Phoenician kings of Tyre, Lebanon, Tyre and Sidon, based in modern-day Lebanon, control over the Israeli coastal plain, coastal plain all the way to Ashdod. Perhaps to facilitate maritime trade or as a repayment for their naval services. At about the same time, the Upper Galilee was also granted to Tyre. In the middle of the 4th century the Phoenicians occupied the entire coast as far as Ascalon in the southern coastal plain.

Nomadic Arabian tribes roamed the Negev desert. They were of paramount strategic and economic importance to the Persians due to their control of desert trade routes stretching from Gaza in the north, an important trading center, to the Arabian peninsula in the south. Unlike the people in the provinces, the tribes were considered "friends" with the empire rather than subjects and they enjoyed some independence from Persia. Until the middle of the 4th century, the Qedarites were the dominant tribe whose territory ran from the Hejaz in the south to the Negev in the north. Around 380 BCE, the Qedarites joined a failed revolt against the Persians and as a consequence they lost their frankincense trade privileges. The trade privileges were taken over by the Nabataeans, an Arab tribe whose capital was in Petra in Transjordan. They established themselves in the Negev where they built a flourishing civilization.

Despite the devastating Greco-Persian Wars, Greek cultural influences rose steadily. Ancient Greek coinage, Greek coins began to circulate in the late 6th and early 5th centuries. Greek traders established Emporium (antiquity), trading posts along the coast in the 6th century from which Greek ceramics, artworks, and other luxury items were imported. These items were popular and no well-to-do household in Palestine would have lacked Greek pottery. Local potters imitated the Greek merchandise, though the quality of their goods were inferior. The first coins in Palestine were minted by the Phoenicians. Yehud coinage, Yehud began minting coins in the second quarter of the 4th century.

In 404 BCE, Egypt threw off the Persian yoke and began extending its domain of influence and military might in Palestine and Phoenicia, leading to confrontations with Persia. The political pendulum swung back and forth as territory was conquered and reconquered. For a brief period of time, Egypt controlled both coastal Palestine and Phoenicia. Egypt was eventually reconquered by Persia in 343.

By the 6th century, Aramaic became the common language in the north, in Galilee and

Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized form of the Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

, replacing Hebrew as the spoken language in Palestine, and it became the region's ''lingua franca''.

Hebrew remained in use in Judah; however the returning exiles brought back Aramaic influence, and Aramaic was used for communicating with other ethnic groups during the Persian period.

Hebrew remained as a language for the upper class and as a Sacred language, religious language.

Hellenistic period

Hellenistic Palestine is the term for Palestine during the Hellenistic period, when Achaemenid Syria was conquered by

Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon (; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), most commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip ...

in 333 BCE and subsumed into his growing Macedonian empire. The conquest was relatively uncomplicated as Persian control of the region had already waned. After his death in 323 BCE, Alexander's empire was divided among his generals, the Diadochi, marking the beginning of Macedonian rule over various territories, including Coele-Syria. The region came under Ptolemaic dynasty, Ptolemaic rule beginning when Ptolemy I Soter took control of Egypt in 322 BCE and

Yehud Medinata

Yehud Medinata, also called Yehud Medinta ( ) or simply Yehud, was an autonomous province of the Achaemenid Empire. Located in Judea, the territory was distinctly Jews, Jewish, with the High Priest of Israel emerging as a central religious and ...

in 320 BCE due to its strategic significance. This period saw conflicts as former generals vied for control, leading to ongoing power struggles and territorial exchanges.

Ptolemaic rule brought stability and economic prosperity to the region. Ptolemy I and his successor, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, maintained control over Yehud Medinata, with the latter bringing the Ptolemaic dynasty to its zenith by winning the first and second Syrian Wars.

Despite these successes, ongoing conflicts with the Seleucids, particularly over the strategic region of Coele-Syria, led to more Syrian Wars.

The region's control fluctuated due to the military campaigns and political maneuvers.

Seleucid dynasty, Seleucid rule began in 198 BCE under Antiochus III the Great, who, like the Ptolemies, allowed the Jews to retain their customs and religion. However, financial strains due to obligations to Rome led to unpopular measures, such as temple robberies, which ultimately resulted in Antiochus III's death in 187 BCE. His successors faced similar challenges, with internal conflicts and external pressures leading to dissatisfaction among the local population. The

Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

, led by Judas Maccabeus, highlighted the growing unrest and resistance against Seleucid authority, eventually leading to significant shifts in power dynamics within the region.

The local Hasmonean dynasty emerged from the Maccabean Revolt, with Simon Thassi becoming high priest and ruler, establishing an independent Judea. His successors, notably John Hyrcanus, expanded the kingdom and maintained relations with Rome and Egypt. However, internal strife and external pressures, particularly from the Seleucids and later the Romans, led to the decline of the Hasmonean dynasty.

Roman period

In 63 BCE, a war of succession in the Hasmonean court provided the Roman general Pompey with the opportunity to make the Jewish kingdom a Client state, client of Rome, starting a centuries-long period of Roman rule. After Siege of Jerusalem (63 BC), sacking Jerusalem, he installed Hyrcanus II, one of the Hasmonean pretenders, as High Priest of Israel, High Priest but denied him the title of king. Most of the territory the Hasmoneans had conquered were awarded to other kingdoms, and Judea now only included Judea proper, Samaria (except for the city of Samaria which was renamed Sebastia, Nablus, Sebaste), southern Galilee, and eastern Idumaea. In 57 BCE, the Romans and Jewish loyalists stamped out an uprising organized by Hyrcanus' enemies. Hoping to quell further unrest, the Romans restructured the kingdom into five autonomous districts, each with its own Sanhedrin, religious council with centers in Jerusalem, Sepphoris,

Jericho

Jericho ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and the capital of the Jericho Governorate. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It had a population of 20,907 in 2017.

F ...

, Amathus, Transjordan, Amathus, and Gadara.

''Poleis'' that had been occupied or even destroyed by the Hasmoneans were rebuilt and they regained their self-governing status. This amounted to a Pompeian era, rebirth for many of the Greek cities and made them Rome's trusty allies in an otherwise unruly region. They expressed their gratitude by adopting new dating systems commemorating Rome's advent, renaming themselves after Roman officials, or minting coins with monograms and imprints of Roman officials.

The turmoil in the Roman world brought by the Liberators' civil war, Roman civil wars relaxed Rome's grip on Judea. In 40 BCE, the Parthian Empire and their Jewish ally Antigonus the Hasmonean defeated a pro-Roman Jewish force led by high priest Hyrcanus II, Phasael and Herod I, the son of Hyrcanus' leading partisan Antipater the Idumaean, Antipater. They managed to conquer Syria and Palestine. Antigonus was made King of Judea. Herod fled to Rome, where he was elected "Herodian Dynasty, King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate and was given the task of retaking Judea. In 37 BCE, with Roman support, Herod reclaimed Judea, and the short-lived reemergence of the Hasmonean dynasty came to an end.

Herodian dynasty and Roman Judea

Herod I, or as became known, Herod the Great, ruled from 37 to 4 BCE. He became known for his many building projects, for increasing the region's prosperity, but also for being a tyrant and involved in many political and familial intrigues.

Herod rebuilt Jerusalem from top to bottom, greatly increasing the city's prestige, including Second Temple#Herod's Temple, the reconstruction of the Second Temple. Herod also greatly expanded the port town of Caesarea Maritima,

[; ] making it by far the largest port in Roman Judea and one of the largest in the whole eastern Mediterranean.

Throughout this period, the Jewish population gradually increased, and the region saw a massive wave of urbanization. More than 30 towns and cities of different sizes were founded, rebuilt, or enlarged in a relatively short period. The Jewish population of the land on the eve of the great revolt may have been as high as 2.2 million. Jerusalem itself reached a peak in size and population at the end of the Second Temple period, when the city covered and had a population of 200,000.

Following Herod's death in 4 BCE, unrest shook the region. It was swiftly quashed by Herod's son Herod Archelaus, Archelaus with the help of the Romans. Herod's kingdom was divided and given to his Herodian Tetrarchy, three sons. In 6 CE Archelaus was banished for misrule and Judea came under direct Roman rule.

Jewish–Roman wars

In 66 CE, the First Jewish–Roman War, also known as the Great Jewish Revolt, erupted. The war lasted for four years and was crushed by the Roman emperors Vespasian and Titus. In 70 CE, the Romans Siege of Jerusalem (70 CE), captured the city of Jerusalem and destroyed both the city and the Second Temple. The events were described by the Jewish historian Josephus, who writes that 1,100,000 Jews perished during the revolt, while a further 97,000 were taken captive. The was imposed on Jews all across the Roman Empire as part of reparations.

In 132 CE, a second uprising, the Bar Kokhba revolt erupted and took three years to put down. It incurred massive costs on both sides, and saw a major shift in the population of Palestine. The sheer scale and scope of the overall destruction is described in a late epitome of Dio Cassius's ''Roman History'', where he states that Roman war operations in the country had left some 580,000 Jews dead, with many more dying of hunger and disease, while 50 of their most important outposts and 985 of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. According to Cassius, "nearly the whole of Judea (Roman province), Judaea was made desolate".

Province of Syria Palaestina

During or after the Bar Kohkba Revolt, Hadrian joined the province of Judea with Galilee and the Paralia (Palestine), Paralia to form the new province of Syria Palaestina. Some scholars view these actions as an attempt to disconnect the Jewish people from their homeland, but this theory is debated.

Jerusalem was re-established as the Aelia Capitolina, a greatly diminished military colony with perhaps no more than 4,000 residents. Jews were banned from the city and from settling in its vicinity as punishment for the Bar Kokbha revolt, though the ban was not strictly enforced and a slow trickle of Jews settled in the city over the subsequent centuries. In the late 2nd and early 3rd century, new cities were founded at Eleutheropolis, Lod, Diospolis, and Emmaus Nicopolis, Nicopolis.

In the 260s, the Palmyrene king Odaenathus helped the Romans defeat the Persians (Sasanian Empire) and became, though nominally still Rome's vassal, the real ruler of Syria Palaestina and Rome's other holdings in the Near East. His widow Zenobia declared herself the Empress of the breakaway Palmyrene Empire but she was Battle of Emesa, defeated by the Romans in 272.

Byzantine period

The tide turned in Christianity's favor in the 4th century. The century began with the Diocletianic Persecution, most intense persecution of Christians the empire had seen, but ended with Christianity becoming the State church of the Roman Empire, Roman state church. Perhaps more than half of the empire's population had then converted to Christianity. Instrumental to this transformation was Rome's first Christian emperor Constantine the Great. He had ascended the throne by defeating his competitors in a series of Civil wars of the Tetrarchy, civil wars and he credited his victories to Christianity. Constantine became a fervent supporter of Christianity and issued laws conveying upon the church and its clergy fiscal and legal privileges and immunities from civic burdens. He also sponsored ecumenical councils, such as the First Council of Nicaea, Council of Nicaea, to settle theological disputes between Christian factions.

Rome's Christianization had a profound impact on Palestine. Churches were built on sites venerated by Christians such as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem where Jesus was thought to have been crucified and buried, and the Church of the Nativity in

Bethlehem

Bethlehem is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, located about south of Jerusalem, and the capital of the Bethlehem Governorate. It had a population of people, as of . The city's economy is strongly linked to Tourism in the State of Palesti ...

where he was thought to have been born. Of the over 140 Christian monasteries built in Palestine in this period, some were among the Christian monasticism before 451, oldest in the world, including Mar Saba, which is still in use to this day, Monastery of Saints John and George of Choziba, Saint George's Monastery in Wadi Qelt, and the Monastery of the Temptation near Jericho. Men flocked to live as pious hermits in the Judean wilderness and soon Palestine became a center for eremitic life. The Council of Chalcedon, ecumenical council in Chalcedon in 451 elevated Jerusalem to a patriarchate and, together with Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, and Constantinpole, it became one of five self-governing centers for Christianity. This elevation greatly boosted the Palestinian church's international prestige.

The Byzantine era was a time of great prosperity and cultural flourishing in Palestine. New areas were cultivated, urbanization increased, and many cities reached their peak populations. Towns increasingly acquired new civic basilicas, porticoed streets with space for shops, and the erection of churches and other religious buildings invigorated their economies. The total population of Palestine may have exceeded one and a half million, its highest ever until the twentieth century.

Caesarea and Gaza became two of the most important centers of learning in the whole Mediterranean region, superseding and replacing those of Alexandria and Athens. Eusebius in his topographical work, ''Onomasticon (Eusebius), Onomasticon: On the Place Names in Divine Scripture'', attempted to correlate names and places from the biblical narratives with existing localities in Palestine. These works conceptualized the western view of Palestine as a Christian Holy Land.