Mughrabi Quarter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Mughrabi Quarter, also known as the

The Mughrabi Quarter, also known as the

The Ottoman taxation registers listed 13 households in the quarter in 1525–26, 69 households, 1 bachelor and 1 imam in 1538–39, 84 households and 11 bachelors in 1553–34, 130 households and 2 bachelors in 1562–63, and 126 households and 7 bachelors in 1596–97. Originally developed for

The Ottoman taxation registers listed 13 households in the quarter in 1525–26, 69 households, 1 bachelor and 1 imam in 1538–39, 84 households and 11 bachelors in 1553–34, 130 households and 2 bachelors in 1562–63, and 126 households and 7 bachelors in 1596–97. Originally developed for

The Mughrabi Quarter, also known as the

The Mughrabi Quarter, also known as the Maghrebi

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan, Algerian, Tunisian, Libyan, Hassaniya and Saharan Arabic di ...

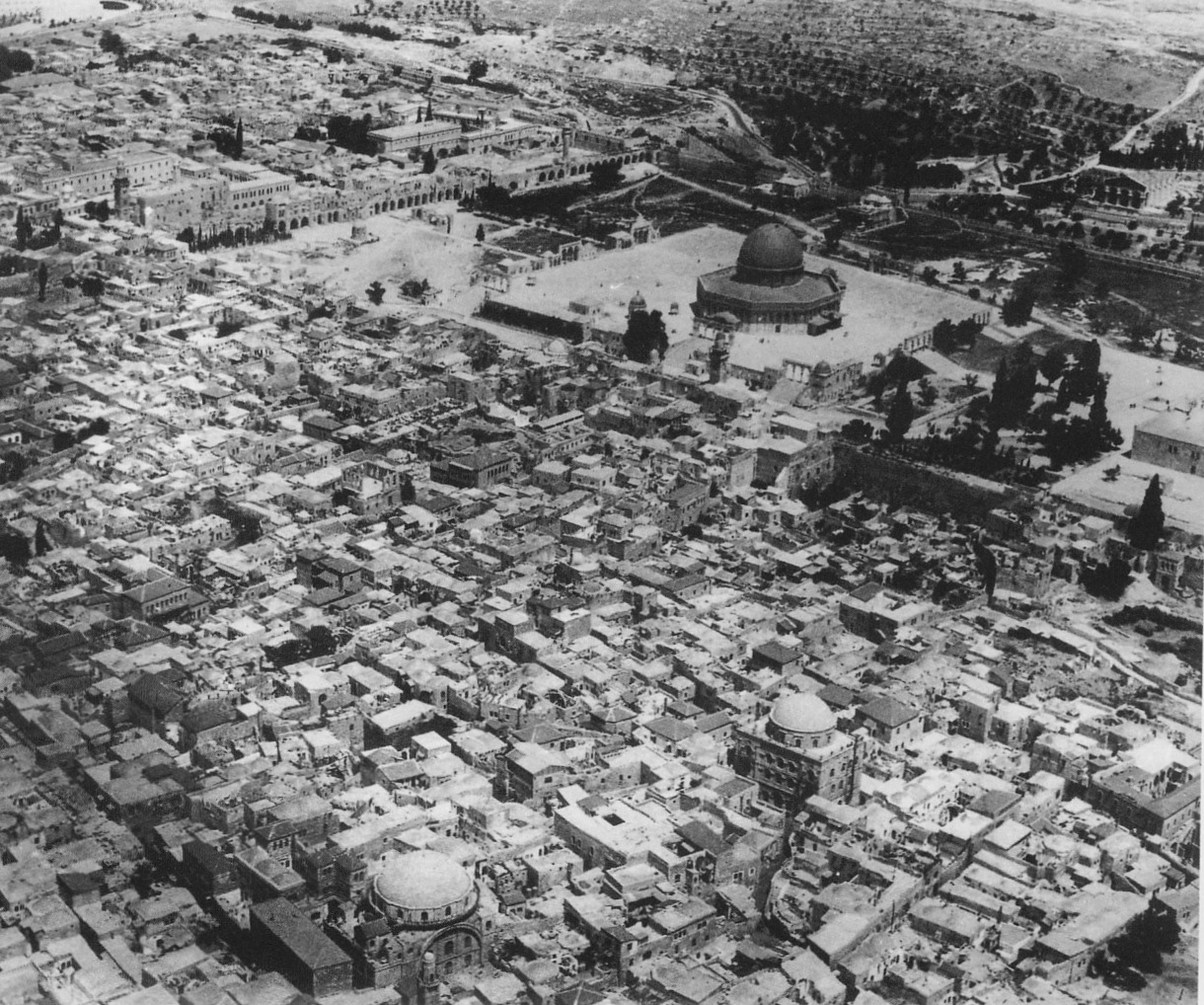

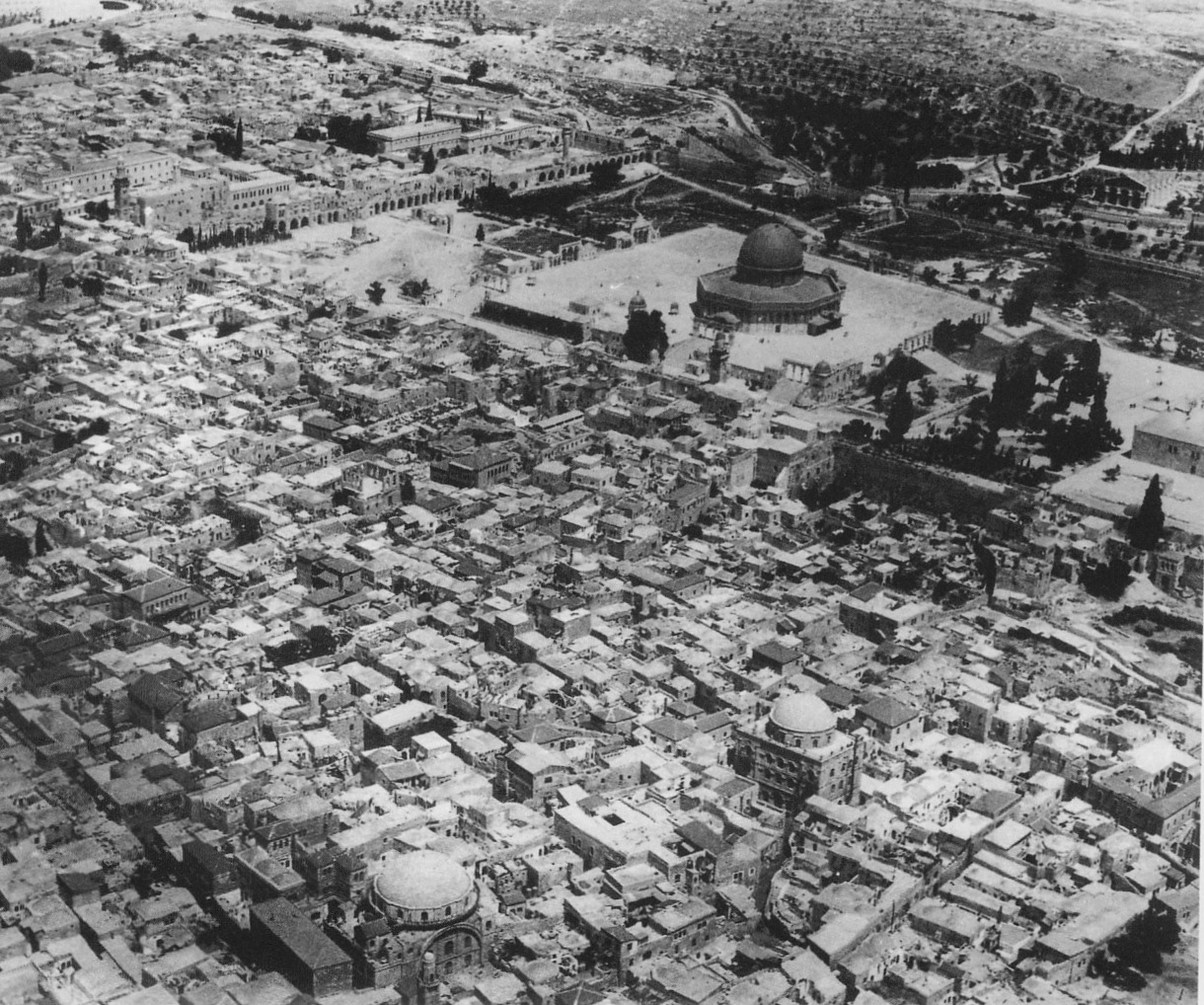

Quarter or Moroccan Quarter, was a neighbourhood in the southeast corner of the Old City of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, established in the late 12th century. It bordered the Western Wall

The Western Wall (; ; Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: ''HaKosel HaMa'arovi'') is an ancient retaining wall of the built-up hill known to Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount of Jerusalem. Its most famous section, known by the same name ...

of the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount (), also known as the Noble Sanctuary (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, 'Haram al-Sharif'), and sometimes as Jerusalem's holy esplanade, is a hill in the Old City of Jerusalem, Old City of Jerusalem that has been venerated as a ...

on the east, the Old City walls on the south (including the Dung Gate

The Dung Gate (), also known as Bab al-Maghariba (), Mughrabi Gate, Moroccan Gate or Silwan Gate, is one of the Gates of the Old City of Jerusalem. It was built as a small postern gate in the 16th century by the Ottomans, first widened for vehic ...

) and the Jewish Quarter Jewish Quarter may refer to:

*Jewish quarter (diaspora), areas of many cities and towns traditionally inhabited by Jews

*Jewish Quarter (Jerusalem), one of the four traditional quarters of the Old City of Jerusalem

*Jewish Quarter (), a popular name ...

to the west. It was an extension of the Muslim Quarter to the north, and was founded as an endowed Islamic waqf

A (; , plural ), also called a (, plural or ), or ''mortmain'' property, is an Alienation (property law), inalienable charitable financial endowment, endowment under Sharia, Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot ...

or religious property by a son of Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

.

The quarter was razed by Israeli forces, at the behest of Teddy Kollek

Theodor "Teddy" Kollek (; 27 May 1911 – 2 January 2007) was an Israeli politician who served as the mayor of Jerusalem from 1965 to 1993, and founder of the Jerusalem Foundation. Kollek was re-elected five times, in 1969, 1973, 1978 Jerusalem ...

, the mayor of West Jerusalem

West Jerusalem or Western Jerusalem (, ; , ) refers to the section of Jerusalem that was controlled by Israel at the end of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. As the city was divided by the Green Line (Israel's erstwhile border, established by ...

, three days after the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

of 1967, in order to broaden the narrow alley leading to the Western Wall and prepare it for public access by Jews seeking to pray there. It is now the site of the Western Wall Plaza

The Western Wall Plaza is a large public square situated adjacent to the Western Wall in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel. It was formed in 1967 as a result of the razing of the Mughrabi Quarter neighborhood at the very ...

.

History

Ayyubid and Mamluk eras

According to the 15th-century historian Mujir ad-Dīn, soon after the Arabs had wrested back Jerusalem from the Crusaders the quarter was established in 1193 bySaladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

's son al-Malik al-Afḍal Nurud-Dīn 'Ali, as a ''waqf

A (; , plural ), also called a (, plural or ), or ''mortmain'' property, is an Alienation (property law), inalienable charitable financial endowment, endowment under Sharia, Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot ...

'' (a mortmain

Mortmain () is the perpetual, inalienable ownership of real estate by a corporation or legal institution; the term is usually used in the context of its prohibition. Historically, the land owner usually would be the religious office of a church ...

consisting of a charitable trust) dedicated to all North African

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

immigrants. The boundaries of this ''ḥārat'' or quarter, according to a later document, were the outer wall of the Haram al-Sharif

Al-Aqsa (; ) or al-Masjid al-Aqṣā () and also is the compound of Islamic religious buildings that sit atop the Temple Mount, also known as the Haram al-Sharif, in the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock, many mosques and ...

to the east; south to the public thoroughfare leading to the Siloan spring; west as far as the residence of the qadi

A qadi (; ) is the magistrate or judge of a Sharia court, who also exercises extrajudicial functions such as mediation, guardianship over orphans and minors, and supervision and auditing of public works.

History

The term '' was in use from ...

of Jerusalem, Shams al-Din; the northern limit ran to the ''Arcades of Umm al-Banat'', otherwise known as the Qanṭarat Umam al-Banāt/Wilson's Arch causeway. It was set aside for "the benefit of all the community of the Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ), also known as the Arab Maghreb () and Northwest Africa, is the western part of the Arab world. The region comprises western and central North Africa, including Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, and Tunisia. The Maghreb al ...

of all description and different occupations, male and female, old and young, the low and the high, to settle on it in its residences and to benefit from its uses according to their different needs." Soon after, Jews, many also from North Africa, were also allowed to settle in the city. By 1303, Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

were well established there, a fact attested by the endowment of a ''Zāwiyah'', or religious institution such as a monastery, made by for this quarter.

Al-Afḍal's waqf was not only religious and charitable in its aims, but also provided for the establishment of a madrassa

Madrasa (, also , ; Arabic: مدرسة , ), sometimes romanized as madrasah or madrassa, is the Arabic word for any type of educational institution, secular or religious (of any religion), whether for elementary education or higher learning. ...

law school there, thereafter called eponym

An eponym is a noun after which or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word ''eponym'' include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovati ...

ously the ''Afḍaliyyah'', for the benefit of the Malikite Islamic jurists (''fuqaha'') in the city. On 2 November 1320, a distinguished scion of an Andalusian Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

family of mystics, Abū Madyan, who had settled in Jerusalem in the early 14th century, drew up a larger waqf endowment consisting of a ''Zāwiyah'' near the Bāb al-Silsilah, or Chain Gate, of the Harat, for the Maghrebis

Maghrebis or Maghrebians () are the inhabitants of the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is a modern Arabic term meaning "Westerners", denoting their location in the western part of the Arab world. Maghrebis are predominantly of Arab and Berber ...

. This second document became the foundational act which was to form the legal cornerstone and richest funding source from that time on until 1967 for the Maghrebi Quarter. It consisted in a waqf property at 'Ain Kārim and another at Qanṭarat Umam al-Banāt at the Gate of the Chain—the latter as a hospice exclusively for newly arrived immigrants—the usufruct

Usufruct () is a limited real right (or ''in rem'' right) found in civil law and mixed jurisdictions that unites the two property interests of ''usus'' and ''fructus'':

* ''Usus'' (''use'', as in usage of or access to) is the right to use or en ...

(''manfa'ah'') of both to be set aside in perpetuity for the Maghrebis

Maghrebis or Maghrebians () are the inhabitants of the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is a modern Arabic term meaning "Westerners", denoting their location in the western part of the Arab world. Maghrebis are predominantly of Arab and Berber ...

in Jerusalem. The Qanṭarat Umam al-Banāt endowment consisted of a hall, two apartments, a yard, private conveniences, and, below, a store and a cave (''qabw''). Attached to the document was a stipulation that the properties be placed, after the donor's death, under the care of an administrator (''mutawalli'') and supervisor (''nāzir'') selected on the basis of the community's recognition of his outstanding qualities of piety and wisdom. The Ain Karim properties alone were extensive, 15,000 dunam

A dunam ( Ottoman Turkish, Arabic: ; ; ; ), also known as a donum or dunum and as the old, Turkish, or Ottoman stremma, was the Ottoman unit of area analogous in role (but not equal) to the Greek stremma or English acre, representing the amo ...

s, and covered most of the village.

Some time in the early 1350s, a third ''waqf'' was instituted by the Marinid Dynasty

The Marinid dynasty ( ) was a Berbers, Berber Muslim dynasty that controlled present-day Morocco from the mid-13th to the 15th century and intermittently controlled other parts of North Africa (Algeria and Tunisia) and of the southern Iberian P ...

's King 'Ali Ibn 'Uthmān Ibn Ya'qūb Ibn 'Abdul-Ḥaqq al-Marini. This consisted of a codex of the Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

copied by his own hand Further endowments to the quarter took place in 1595 and 1630.

Until the advent of Muslims in Jerusalem, most of the area below the Western Wall was crammed with rubble, and Jewish prayer throughout the Islamic period appears to have been performed inside synagogues in the Jewish Quarter, or, on public occasions, on the Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives or Mount Olivet (; ; both lit. 'Mount of Olives'; in Arabic also , , 'the Mountain') is a mountain ridge in East Jerusalem, east of and adjacent to Old City of Jerusalem, Jerusalem's Old City. It is named for the olive, olive ...

. The narrow space dividing the Western Wall from the houses of the Mughrabi Quarter was created at the behest of Suleiman the Magnificent

Suleiman I (; , ; 6 November 14946 September 1566), commonly known as Suleiman the Magnificent in the Western world and as Suleiman the Lawgiver () in his own realm, was the List of sultans of the Ottoman Empire, Ottoman sultan between 1520 a ...

in the sixteenth century in order to allow prayers to be said there.

Ottoman era

The Ottoman taxation registers listed 13 households in the quarter in 1525–26, 69 households, 1 bachelor and 1 imam in 1538–39, 84 households and 11 bachelors in 1553–34, 130 households and 2 bachelors in 1562–63, and 126 households and 7 bachelors in 1596–97. Originally developed for

The Ottoman taxation registers listed 13 households in the quarter in 1525–26, 69 households, 1 bachelor and 1 imam in 1538–39, 84 households and 11 bachelors in 1553–34, 130 households and 2 bachelors in 1562–63, and 126 households and 7 bachelors in 1596–97. Originally developed for Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

, over the centuries Jewish, Christian and Muslim people from Palestine and elsewhere had at various times taken up residence there. By the time Israel decided to demolish their houses, roughly half of the zone's inhabitants could trace their origins back to Maghreb immigrants.

According to the French traveller Chateaubriand who visited in 1806, some of the residents of the quarter were descended from Moors who had been expelled from Spain in the late 15th century. They had been well received by the local community and a mosque had been built for them. Residents of the neighborhood held on to their culture in the way of food, clothing and traditions until it became assimilated with the rest of the Old City in the 19th century. Thus it also became a natural place of stay to Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

who came on pilgrimage to the al-Aqsa Mosque

The Aqsa Mosque, also known as the Qibli Mosque or Qibli Chapel is the main congregational mosque or Musalla, prayer hall in the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City (Jerusalem), Old City of Jerusalem. In some sources the building is also n ...

.

Over the years a small number of schools and mosques were established in the quarter and Muslim clerics who performed religious duties at the al-Aqsa Mosque lived there.

The site of Jewish prayer and lamentation was a stretch of some along the wall, accessed via a narrow passage from King David's Street. In depth from the wall the paved area extended 11 feet. At the southern end lay one of the two ''zāwiyyah'' dedicated there in medieval times and the lane to the Wailing Wall sector ended in a blind alley closed off by the houses of the Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

beneficiaries. In 1840 a proposal by a British Jew, the first attempt to change the ''status quo,'' was conveyed via the British consul, and requested that Jews be allowed to repave the 120 sq. metre (1300 sq. ft.) area. The plan was rejected both by the Abu Madyan ''waqf'' administrator and by Muhammad Ali Pasha Mehmed Ali Pasha may refer to:

* Muhammad Ali of Egypt (1769–1849), considered the founder of modern Egypt

* Çerkes Mehmed Pasha (died 1625), Ottoman statesman and grand vizier

* Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha (1815–1871), Ottoman statesman and gra ...

. Muslims in the area also complained of the excessive noise, as opposed to past practice, caused by recent Jewish pilgrims. Jews at prayer were asked to continue their traditional practices quietly, and to refrain from proclaiming on doctrinal matters there.

By the beginning of the 19th century Jewish worshippers were few, and according to Yehoshua Ben Arieh, lacked any special distinction. In an account of his travels to the Holy Land in 1845, T. Tobler noted the existence of a mosque in the Mughrabi quarter.

According to Yeohoshua Ben-Arieh, the Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

regarded the Jews as infidels. They were subjected to harassment and were required to pay a sum in exchange for the right to pray there undisturbed. Increased friction at the site between Jews and Muslims arose with the onset of Zionism and the resulting fear among the Muslims that the Jews would claim the entire Temple Mount. Attempts were made at various times, by Moses Montefiore

Sir Moses Haim Montefiore, 1st Baronet, (24 October 1784 – 28 July 1885) was a British financier and banker, activist, Philanthropy, philanthropist and Sheriffs of the City of London, Sheriff of London. Born to an History ...

and Baron Rothschild to buy the whole area, without success. In 1887 Rothschild's bid to purchase the Quarter came with a project to rebuild it as "a merit and honor to the Jewish People" relocating the inhabitants in better accommodation elsewhere. The Ottoman authorities appeared to be ready to give their approval. According to some sources, the highest secular and Muslim religious authorities in Jerusalem, such as the ''Mutasarrıf'' or Ottoman Governor of Jerusalem, Şerif Mehmed Rauf Paşa, and the Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including Al-Aqsa. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadership in Jerusal ...

, Mohammed Tahir Husseini

Mohammed Tahir Mustafa Tahir al-Husayni (alternatively transliterated al-Husseini) (, 1842–1908) was the ''Qadi'' (Chief Justice) of the Sharia courts of Jerusalem and was the father of Kamil al-Husayni and Mohammad Amin al-Husayni, both of wh ...

, actually gave their approval. The plan foundered on Jewish, rather than Muslim objections was shelved after the chief rabbinical Haham

''Hakham'' (or ''Chakam(i), Haham(i), Hacham(i), Hach''; ) is a term in Judaism meaning a wise or skillful man; it often refers to someone who is a great Torah scholar. It can also refer to any cultured and learned person: "He who says a wise th ...

of the Jerusalemite Sephardi

Sephardic Jews, also known as Sephardi Jews or Sephardim, and rarely as Iberian Peninsular Jews, are a Jewish diaspora population associated with the historic Jewish communities of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal) and their descendant ...

community stated that he had had a "providential intimation" that, were the sale to go through, a terrible massacre of Jews would ensue. His opinion might have reflected a Sephardi fear that the Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that Ethnogenesis, emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium Common era, CE. They traditionally spe ...

s would thereby take possession of the holiest site in Judaism.

In the first two months after the Ottoman Empire's entry into the First World War, the Turkish governor of Jerusalem, Zakey Bey, offered to sell the quarter to Jews, requesting a sum of £20,000 which, he said, would be used to both rehouse the Muslim families and to create a public garden in front of the Wall. However, the Jews of the city lacked the necessary funds.

British Mandate era

A hospice, the ''Dar al-Magharibah'', existed in the quarter to extend lodgings for Mughrabi Muslims on pilgrimage to the Islamic sites of Jerusalem. In April 1918,Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( ; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born Israeli statesman, biochemist, and Zionist leader who served as president of the World Zionist Organization, Zionist Organization and later as the first pre ...

, then a prominent Zionist leader on a visit to Jerusalem, sent a letter via Ronald Storrs

Sir Ronald Henry Amherst Storrs (19 November 1881 – 1 November 1955) was an official in the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, Foreign Office. He served as Oriental Secretary in Cairo, Military Governor of Jerusalem, Governor of Britis ...

offering the sheikhs £70,000 in exchange for the Wall and the buildings of the Mughrabi quarter. This was immediately rejected when the Muslim authorities got wind of the proposal. Nothing daunted, Weizmann then addressed his petition to Arthur Balfour

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (; 25 July 184819 March 1930) was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary ...

, asking him to resolve the issue by ruling in favour of the Jews. In a letter of 30 May that year, headed ''THE HANDING OVER OF THE WAILING WALL TO THE JEWS'', he gave his reasons as follows:

We Jews have many holy places in Palestine, but the Wailing Wall-believed to be part of the old Temple Wall-is the only one which is in some sense left to us. All the others are in the hands of Christians or Moslems. And even the Wailing Wall is not really ours. It is surrounded by a group of miserable, dirty cottages and derelict buildings, which make the whole place from the hygienic point of view a positive danger, and from the sentimental point of view a source of constant humiliation to the Jews of the world. Our most sacred monument, in our most sacred city, is in the hands of some doubtful Moghreb religious community, which keeps these cottages as a source of income. We are willing to compensate this community very liberally, but we should like the place to be cleaned up; we should like to give it a dignified and respectable appearance.The wall as well as the Mughrabi Quarter nonetheless, throughout the British Mandatory period, remained Waqf property, while Jews retained their longstanding right to visit it. During the

1929 Palestine riots

The 1929 Palestine riots, Buraq Uprising (, ) or the Events of 1929 (, , ''lit.'' Events of 5689 Anno Mundi), was a series of demonstrations and riots in late August 1929 in which a longstanding dispute between Palestinian Arabs and Jews ove ...

Jews and Muslims did however clash over competing claims on the area adjacent to the Mughrabi Quarter, with Jews denying they had no aims regarding the Haram al-Sharif

Al-Aqsa (; ) or al-Masjid al-Aqṣā () and also is the compound of Islamic religious buildings that sit atop the Temple Mount, also known as the Haram al-Sharif, in the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock, many mosques and ...

but demanding the British authorities expropriate and raze the Mughrabi quarter. Jewish Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

and Muslim Maghrebi people

Maghrebi Arabic, often known as ''ad-Dārija'' to differentiate it from Modern Standard Arabic, Literary Arabic, is a vernacular Arabic Varieties of Arabic, dialect continuum spoken in the Maghreb. It includes the Moroccan Arabic, Moroccan, Alge ...

pilgrims, both groups on a visit to Jerusalem, were present at the riots, and several of the former were killed or injured. Great Britain appointed a commission under the approval of the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

to settle the issue. The Commission again reaffirmed the status quo, while placing certain restrictions on activities, including forbidding Jews from conducting the Yom Kippur

Yom Kippur ( ; , ) is the holiest day of the year in Judaism. It occurs annually on the 10th of Tishrei, corresponding to a date in late September or early October.

For traditional Jewish people, it is primarily centered on atonement and ...

prayers (the holiest holiday in Judaism), which involved the blowing of the Shofar

A shofar ( ; from , ) is an ancient musical horn, typically a ram's horn, used for Jewish ritual purposes. Like the modern bugle, the shofar lacks pitch-altering devices, with all pitch control done by varying the player's embouchure. The ...

, and Muslims from carrying out the Dhikr

(; ; ) is a form of Islamic worship in which phrases or prayers are repeatedly recited for the purpose of remembering God. It plays a central role in Sufism, and each Sufi order typically adopts a specific ''dhikr'', accompanied by specific ...

(Islamic prayers) close to the wall or to cause annoyance to the Jews.

Jordanian era

When Jordanian forces emerged as the victors in the battle for possession of the Old City in the1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, also known as the First Arab–Israeli War, followed the 1947–1948 civil war in Mandatory Palestine, civil war in Mandatory Palestine as the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. The civil war becam ...

, 1,500 Jewish residents, coinciding with the flight or expulsion of 70,000 Palestinians from Israeli-occupied areas of Jerusalem, were expelled from the Jewish Quarter, which was in the vicinity of the Mughrabi zone.

Disputes were not infrequent between the quarter's inhabitants and Palestinian landlords, squabbling over property rights. In 1965, Palestinian squatters in Jewish properties on the edge of the Mughrabi Quarter were evicted by the Jordanian government and resettled in the Shu'afat refugee camp, four kilometers north of the Old City. The motives behind this ejection are unknown.

According to French historian Vincent Lemire, during the period of Jordanian control the French Fourth and Fifth Republics claimed extraterritorial jurisdiction

Extraterritorial jurisdiction (ETJ) is the legal ability of a government to exercise authority beyond its normal boundaries.

Any authority can claim ETJ over any external territory they wish. However, for the claim to be effective in the external ...

over the Waqf Abu Madyan, an Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

n ''waqf'' located in the Mughrabi Quarter. France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

had claimed jurisdiction over the ''waqf'' on 6 July 1949. In the aftermath of the Arab–Israeli War, Israel annexed the village of Ein Karem

Ein Karem (; )Sharon, 2004, p155/ref> also Ein Kerem or Ain Karem, is a historic mountain village southwest of Jerusalem, presently a neighborhood in the outskirts of the modern city, within the Jerusalem District in Israel. It is the site of th ...

. The Waqf Abu Madyan depended on the village's agricultural output for income and was thus left in a precarious financial situation, precipitating France's sovereignty claim.

The French Ministry of Foreign Affairs

The Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs (, MEAE) is the ministry of the Government of France that handles France's foreign relations. Since 1855, its headquarters have been located at 37 Quai d'Orsay, close to the National Assembly. The term ...

used its position in Jerusalem to curry favor with Israel, Algeria, Tunisia

Tunisia, officially the Republic of Tunisia, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered by Algeria to the west and southwest, Libya to the southeast, and the Mediterranean Sea to the north and east. Tunisia also shares m ...

, and Morocco by providing financial support to the ''waqf'' and, therefore, North African Muslim pilgrims. For example, in 1954 French intellectual Louis Massignon

Louis Massignon (25 July 1883 – 31 October 1962) was a French Catholic scholar of Islam and a pioneer of Catholic-Muslim mutual understanding. He was an influential figure in the twentieth century with regard to the Catholic Church's relatio ...

organized a charitable collection at the gates of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen

The Great Mosque of Tlemcen (, ''el-Jemaa el-Kebir litilimcen'') is a major historic mosque in Tlemcen, Algeria. It was founded and first built in 1082 but modified and embellished several times afterwards. It is considered one of the most import ...

in Algeria in support of the ''waqf'' in an effort to improve Franco-Algerian relations. On 12 February 1962—four days after the Charonne Métro station massacre and about one month prior to the signing of the Évian Accords

The Évian Accords were a set of declarations between the French Government and the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic on 18 March 1962 in Évian-les-Bains which outlined the agreements for Algeria's Independence alongside coope ...

, a ceasefire agreement between France and Algeria

Algeria, officially the People's Democratic Republic of Algeria, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It is bordered to Algeria–Tunisia border, the northeast by Tunisia; to Algeria–Libya border, the east by Libya; to Alger ...

—France abandoned its claim to the ''waqf''.

Demolition

Preparations

The razing of the quarter took place without any official authorization. Responsibility for demolishing the Mughrabi Quarter is contested between several figures:Teddy Kollek

Theodor "Teddy" Kollek (; 27 May 1911 – 2 January 2007) was an Israeli politician who served as the mayor of Jerusalem from 1965 to 1993, and founder of the Jerusalem Foundation. Kollek was re-elected five times, in 1969, 1973, 1978 Jerusalem ...

, Moshe Dayan

Moshe Dayan (; May 20, 1915 – October 16, 1981) was an Israeli military leader and politician. As commander of the Jerusalem front in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, Chief of General Staff (Israel), Chief of the General Staff of the Israel Defe ...

, Colonel Shlomo Lahat, Uzi Narkiss

Uzi Narkiss (; January 6, 1925 – December 17, 1997) was an Israeli general. Narkiss was commander of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) units in the Central Region during the 1967 Six-Day War. Narkiss appears in the famous photograph of Defense Mi ...

and David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary List of national founders, national founder and first Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency ...

. The precise details of how the operation was carried out are not clear, since no paper trail was left by the participants. According to one source, the retired Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary List of national founders, national founder and first Prime Minister of Israel, prime minister of the State of Israel. As head of the Jewish Agency ...

played a pivotal role in the decision to demolish the quarter. He visited the Wall on 8 June, with Teddy Kollek, Shimon Peres

Shimon Peres ( ; ; born Szymon Perski, ; 2 August 1923 – 28 September 2016) was an Israeli politician and statesman who served as the prime minister of Israel from 1984 to 1986 and from 1995 to 1996 and as the president of Israel from 2007 t ...

and Ya'akov Yannai, head of the National Parks Authority at the time Ben-Gurion was upset at seeing a sign in Arabic on 9 June, the day after the Old City had been captured and protested at the presence of a sign in Arabic.

He noticed a tile sign in front of the Wall, which read "Al-Burak Road" in English and Arabic but not in Hebrew. It was a reminder of the prophet Mohammad's legendary horse,Ben-Gurion also proposed the following day that the walls of the Old City be demolished since they weren't Jewish, but the government did not take up the idea. Teddy Kollek in his memoirs wrote that it was necessary to knock down the quarter because a pilgrimage to the wall was being organized with hundreds of thousands of Jews, and their passage through the "dangerous narrow alleys" of the "slum hovels" was unthinkable: they needed a clear bright space to celebrate their return to the site after 19 years. To that end, archaeologists and planners had examined the area the day before to map out what had to be demolished. The operations had a larger scope, not only to clear the Mughrabi quarter, but also expel all the Palestinian inhabitants of the contiguous, predominantly Arab-ownedBuraq The Buraq ( "lightning") is a supernatural equine-esque creature in Islamic tradition that served as the mount of the Islamic prophet Muhammad during his Isra and Mi'raj journey from Mecca to Jerusalem and up through the heavens and back by ..., left tethered by the Wall as the prophet took his journey to heaven from the famous rock above. Ben-Gurion looked at the sign with disapproval and asked if anyone had a hammer. A soldier tried to pry off the tile with a bayonet, but Ben-Gurion was concerned about damage to the stone. An axe was produced and the name on the tile carefully removed. The symbolism of expunging Arabic from the redeemed Jewish holy site was not lost on the surrounding crowd, or on Ben-Gurion. They cheered, and Ben-Gurion exclaimed, "This is the greatest moment of my life since I came to Israel."

Jewish Quarter Jewish Quarter may refer to:

*Jewish quarter (diaspora), areas of many cities and towns traditionally inhabited by Jews

*Jewish Quarter (Jerusalem), one of the four traditional quarters of the Old City of Jerusalem

*Jewish Quarter (), a popular name ...

, who, he claimed, had "no special feeling" for the place and would be satisfied to receive ample compensation for their expulsion. ''The Jerusalem Post

''The Jerusalem Post'' is an English language, English-language Israeli broadsheet newspaper based in Jerusalem, Israel, founded in 1932 during the Mandate for Palestine, British Mandate of Mandatory Palestine, Palestine by Gershon Agron as ''Th ...

'' described the area as a jumble of hovels on the same day bulldozing operations began, and a writer later commented on this designation as follows:

The day the bulldozing began the quarter was described in ''The Jerusalem Post'' as a slum. Two days later it was reported as having been by and large abandoned during the siege. I expect in time that its existence will vanish altogether from the pages of developing Zionist history.Shlomo Lahat, who had just flown back from a fund-raising campaign in South America, recalled that on his arrival at 4 am 7 June, Moshe Dayan informed him of the imminent conquest of Jerusalem, and that he wanted Lahat, a stickler for discipline, as military governor of the city. He needed someone "prepared to shoot Jews if need be". Once the city was taken, at a meeting involving himself, Dayan, Kollek and

Uzi Narkiss

Uzi Narkiss (; January 6, 1925 – December 17, 1997) was an Israeli general. Narkiss was commander of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) units in the Central Region during the 1967 Six-Day War. Narkiss appears in the famous photograph of Defense Mi ...

, Lahat suggested that the programmed visit of Jews on Shavuot

(, from ), or (, in some Ashkenazi Jews, Ashkenazi usage), is a Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday, one of the biblically ordained Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It occurs on the sixth day of the Hebrew month of Sivan; in the 21st century, it may ...

meant that there would be a crush of people crowding in, risking a higher casualty rate than that sustained by the war, and suggested the area be cleared, an idea that met Dayan's approval. This is disputed by Ya'akov Salman who stated that it was he who raised the problem of the courtyard's limitations.

Demolition

There were 135 houses in the quarter, and the destruction left at least 650 people refugees. According to one eyewitness, after its capture by Israel, the entire Old City was placed under a strict curfew. On Saturday evening 10 June, the last day of theSix-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

, coinciding with the end of the Jewish Sabbath

Shabbat (, , or ; , , ) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism's day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Friday–Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stories describing the cre ...

, a number of searchlights were positioned and floodlit up the quarter's warrens. Twenty-odd Jerusalem building contractors, hired by Kollek, first knocked down a public lavatory with sledgehammers. Army bulldozers were then brought in to raze the houses.

The residents were given either a few minutes, fifteen minutes or three hours to evacuate their homes. They initially refused to budge. In the face of this reluctance, lieutenant Colonel Ya'akov Salman, the deputy military governor, issued an order to an Engineering Corps officer to start bulldozing, and, on striking one particular structure, caused the whole building to collapse. It was this act which caused the remaining residents to flee their apartments and enter vehicles that were stationed outside to bus them away. Amidst the rubble, a middle-aged, or elderly woman, , was discovered in her death throes. One of the engineers, Yohanan Montsker, had her rushed to hospital but by midnight she was dead. According to an interview given two decades later by

Eitan Ben-Moshe, the engineer attached to the IDF Central Command who oversaw the operation, she was not the only victim. He recalled recovering three bodies that were transported to the Bikur Cholim Hospital

Bikur Cholim Hospital () was a 200-bed general hospital in West Jerusalem, established in the 19th century and closed around 2020. Until then, it was the oldest hospital in the country still operating.

Bikur Cholim had obstetrics and cardiac depa ...

, and while some other bodies were buried with the disposed rubble:

I had thrown out all the garbage. We threw out the wreckage of houses together with the Arab corpses. We threw Arab corpses and not Jewish, so that they would not convert the area to a place where it is forbidden to tread.The following morning, Colonel Lahat described the demolition workers as mostly being drunk "on wine and joy". Permission to salvage their personal belongings was denied. The reason given by an Israeli soldier was that they were pressed for time, since only two days remained before the feast of the "Passover" (actually

Shavuot

(, from ), or (, in some Ashkenazi Jews, Ashkenazi usage), is a Jewish holidays, Jewish holiday, one of the biblically ordained Three Pilgrimage Festivals. It occurs on the sixth day of the Hebrew month of Sivan; in the 21st century, it may ...

), and many Jews were expected to arrive on the following Tuesday at the Western Wall. The haste of demolition was necessary, it was argued, to prepare a yard for the festive worshippers. The prime minister at the time, Levi Eshkol

Levi Eshkol ( ; 25 October 1895 – 26 February 1969), born Levi Yitzhak Shkolnik (), was the prime minister of Israel from 1963 until his death from a heart attack in 1969. A founder of the Israeli Labor Party, he served in numerous seni ...

, was completely unaware of the operation, and phoned Narkiss on the 11th asking the reason why the houses were being demolished. Narkiss, pretending not to know, replied that he'd look into the matter.

Historic buildings razed

In addition to 135 houses, the demolition destroyed the ''Bou Medyan''zaouia

A ''zawiya'' or ''zaouia'' (; ; also spelled ''zawiyah'' or ''zawiyya'') is a building and institution associated with Sufis in the Islamic world. It can serve a variety of functions such a place of worship, school, monastery and/or mausoleum. ...

, the Sheikh Eid Mosque, – claimed to survive from the time of Saladin. In destroying the small mosque near the Buraq section of the Wall, associated with the ascent of Mohammad on his steed Buraq

The Buraq ( "lightning") is a supernatural equine-esque creature in Islamic tradition that served as the mount of the Islamic prophet Muhammad during his Isra and Mi'raj journey from Mecca to Jerusalem and up through the heavens and back by ...

to heaven, the engineer Ben Moshe is quoted as having exclaimed: "Why shouldn't the mosque be sent to Heaven, just as the magic horse did?"

Two years later, another complex of buildings close to the wall, that included ''Madrasa Fakhriya'' (''Fakhriyyah zawiyya'') and the house in front of the Bab al-Magharibah that the Abu al-Sa'ud family had built and inhabited since the 16th century but which had been spared in the 1967 destruction, were demolished in June 1969. The Abu al-Sa'ud building was a well-known example of Mamluk architecture

Mamluk architecture was the architectural style that developed under the Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517), which ruled over Egypt, the Levant, and the Hijaz from their capital, Cairo. Despite their often tumultuous internal politics, the Mamluk su ...

, and there were several reasons given for its demolition. Its removal enabled Israeli archaeologists to excavate in the area; to provide open ground to enable the IDF to access the area rapidly should troubles arise at the Wall, and finally, while the antiquity of the housing complex was admitted, the fact too that extensive repairs to the roof and balconies had been made using railway track beams and concrete was adduced to assert that they had sufficient modern traces to be accidental to the area's history. Yasser Arafat

Yasser Arafat (4 or 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), also popularly known by his Kunya (Arabic), kunya Abu Ammar, was a Palestinian political leader. He was chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from 1969 to 2004, Presid ...

's mother was of al-Sa'ud heritage, and it appears that Arafat had lived in the house during his childhood, in the years 1933 to 1936.

On 12 June, at a Ministerial Meeting on the Status of Jerusalem, when the issue of demolitions in the Old City was broached, the Justice Minister Ya'akov Shapira judged that: "They are illegal demolitions but it's good that they are being done." Lieutenant Colonel Yaakov Salman, the deputy military governor in charge of the operation, aware of possible legal trouble on account of the Fourth Geneva Convention

The Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (), more commonly referred to as the Fourth Geneva Convention and abbreviated as GCIV, is one of the four treaties of the Geneva Conventions. It was adopted in August 1 ...

forearmed himself with documents from the East Jerusalem municipality testifying to the poor sanitary conditions in the neighborhood and Jordanian plans to eventually evacuate it. By the 14th, some 200,000 Israelis had come to visit the site.

Aftermath

On 18 April 1968, the Israeli government expropriated the land for public use and paid from 100 to 200Jordanian dinar

The Jordanian dinar (; ISO 4217, code: JOD; unofficially abbreviated as JD) has been the currency of Jordan since 1950. The dinar is divided into 100 qirsh (also called piastres) or 1000 fils (currency), fulus. Fils are effectively obsolete; howe ...

s to each family that had been displaced. 41 heads of families who had been evicted from the area wrote to Kollek to thank him for his assistance in resettling them in better housing conditions. The rest of the families have refused compensation on the grounds that it would lend legitimacy to what Israel did to them.

In the post-1967 period, many of the evicted refugees managed to emigrate to Morocco via Amman

Amman ( , ; , ) is the capital and the largest city of Jordan, and the country's economic, political, and cultural center. With a population of four million as of 2021, Amman is Jordan's primate city and is the largest city in the Levant ...

due to the intervention of King Hassan II

Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

*Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scotti ...

. Other refugee families resettled in the Shu'afat refugee camp and other parts of Jerusalem. The prayer site was extended southwards to double its length from 28 to 60 meters, and the original plaza of four meters to 40 meters: the small 120 square meter area in front of the wall became the Western Wall Plaza

The Western Wall Plaza is a large public square situated adjacent to the Western Wall in the Jewish Quarter of the Old City of Jerusalem, Israel. It was formed in 1967 as a result of the razing of the Mughrabi Quarter neighborhood at the very ...

, now in use as an open-air synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

covering 20,000 square meters.

In a letter to the United Nations, the Israeli government stated nine months later that the buildings were demolished after the Jordanian government had allowed the neighborhood to become a slum

A slum is a highly populated Urban area, urban residential area consisting of densely packed housing units of weak build quality and often associated with poverty. The infrastructure in slums is often deteriorated or incomplete, and they are p ...

area.

The expelled community continues to elect an administrator or mukhtar

A mukhtar (; ) is a village chief in the Levant: "an old institution that goes back to the time of the Ottoman rule". According to Amir S. Cheshin, Bill Hutman and Avi Melamed, the mukhtar "for centuries were the central figures". They "were ...

for the no-longer existing Mughrabi Quarter.

Archeological excavations in early January 2023 revealed walls nearly a metre (3 ft) high, traces of paint, a cobbled courtyard and a system to drain rainwater.

Interpretations

According toGershom Gorenberg

Gershom Gorenberg () is an American-born Israeli journalist and historian specializing in Middle Eastern politics and the interaction of religion and politics.

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Coord, 31, 46, 36, N, 35, 14, 3, E, display=title 1190s establishments in the Ayyubid Sultanate 1967 disestablishments Former neighbourhoods Historic sites in Jerusalem Moroccan diaspora Neighbourhoods of Jerusalem Old City (Jerusalem) Quarters (urban subdivision)