Mental chronometry is the scientific study of processing speed or reaction time on cognitive tasks to infer the content, duration, and temporal sequencing of mental operations. Reaction time (RT; also referred to as "response time") is measured by the elapsed time between stimulus onset and an individual's response on elementary cognitive tasks (ECTs), which are relatively simple perceptual-motor tasks typically administered in a laboratory setting. Mental chronometry is one of the core methodological paradigms of human

Mental chronometry is the scientific study of processing speed or reaction time on cognitive tasks to infer the content, duration, and temporal sequencing of mental operations. Reaction time (RT; also referred to as "response time") is measured by the elapsed time between stimulus onset and an individual's response on elementary cognitive tasks (ECTs), which are relatively simple perceptual-motor tasks typically administered in a laboratory setting. Mental chronometry is one of the core methodological paradigms of human History and early observations

Purely psychological inquiries into the nature of reaction time came about in the mid-1850s. Psychology as a quantitative, experimental science has historically been considered as principally divided into two disciplines: Experimental and differential psychology. The scientific study of mental chronometry, one of the earliest developments in scientific psychology, has taken on a microcosm of this division as early as the mid-1800s, when scientists such as Hermann von Helmholtz and Wilhelm Wundt designed reaction time tasks to attempt to measure the speed of neural transmission. Wundt, for example, conducted experiments to test whether emotional provocations affected pulse and breathing rate using a kymograph.

Sir Francis Galton is typically credited as the founder of differential psychology, which seeks to determine and explain the mental differences between individuals. He was the first to use rigorous RT tests with the express intention of determining averages and ranges of individual differences in mental and behavioral traits in humans. Galton hypothesized that differences in

Purely psychological inquiries into the nature of reaction time came about in the mid-1850s. Psychology as a quantitative, experimental science has historically been considered as principally divided into two disciplines: Experimental and differential psychology. The scientific study of mental chronometry, one of the earliest developments in scientific psychology, has taken on a microcosm of this division as early as the mid-1800s, when scientists such as Hermann von Helmholtz and Wilhelm Wundt designed reaction time tasks to attempt to measure the speed of neural transmission. Wundt, for example, conducted experiments to test whether emotional provocations affected pulse and breathing rate using a kymograph.

Sir Francis Galton is typically credited as the founder of differential psychology, which seeks to determine and explain the mental differences between individuals. He was the first to use rigorous RT tests with the express intention of determining averages and ranges of individual differences in mental and behavioral traits in humans. Galton hypothesized that differences in Sensory factors

Early researchers noted that varying the sensory qualities of the stimulus affected response times, wherein increasing the perceptual salience of stimuli tends to decrease reaction times. This variation can be brought about by a number of manipulations, several of which are discussed below. In general, the variation in reaction times produced by manipulating sensory factors is likely more a result of differences in peripheral mechanisms than of central processes.Strength of stimulus

One of the earliest attempts to mathematically model the effects of the sensory qualities of stimuli on reaction time duration came from the observation that increasing the intensity of a stimulus tended to produce shorter response times. For example, Henri Piéron (1920) proposed formulae to model this relationship of the general form: :, where represents stimulus intensity, represents a reducible time value, represents an irreducible time value, and represents a variable exponent that differs across senses and conditions. This formulation reflects the observation that reaction time will decrease as stimulus intensity increases down to the constant , which represents a theoretical lower limit below which human physiology cannot meaningfully operate. The effects of stimulus intensity on reducing RTs was found to be relative rather than absolute in the early 1930s. One of the first observations of this phenomenon comes from the research of Carl Hovland, who demonstrated with a series of candles placed at different focal distances that the effects of stimulus intensity on RT depended on previous level of adaptation. In addition to stimulus intensity, varying stimulus strength (that is, "amount" of stimulus available to the sensory apparatus per unit time) can also be achieved by increasing both the ''area'' and ''duration'' of the presented stimulus in an RT task. This effect was documented in early research for response times to sense of taste by varying the area over taste buds for detection of a taste stimulus, and for the size of visual stimuli as amount of area in the visual field. Similarly, increasing the duration of a stimulus available in a reaction time task was found to produce slightly faster reaction times to visual and auditory stimuli, though these effects tend to be small and are largely consequent of the sensitivity to sensory receptors.Sensory modality

The sensory modality over which a stimulus is administered in a reaction time task is highly dependent on the afferent conduction times, state change properties, and range of sensory discrimination inherent to our different senses. For example, early researchers found that an auditory signal is able to reach central processing mechanisms within 8–10 ms, while visual stimulus tends to take around 20–40 ms. Animal senses also differ considerably in their ability to rapidly change state, with some systems able to change almost instantaneously and others much slower. For example, the vestibular system, which controls the perception of one's position in space, updates much more slowly than does the auditory system. The range of sensory discrimination of a given sense also varies considerably both within and across sensory modality. For example, Kiesow (1903) found in a reaction time task of taste that human subjects are more sensitive to the presence of salt on the tongue than of sugar, reflected in a faster RT by more than 100 ms to salt than to sugar.Response characteristics

Early studies of the effects of response characteristics on reaction times were chiefly concerned with the physiological factors that influence the speed of response. For example, Travis (1929) found in a key-pressing RT task that 75% of participants tended to incorporate the down-phase of the common tremor rate of an extended finger, which is about 8–12 tremors per second, in depressing a key in response to a stimulus. This tendency suggested that response times distributions have an inherent periodicity, and that a given RT is influenced by the point during the tremor cycle at which a response is solicited. This finding was further supported by subsequent work in the mid-1900s showing that responses were less variable when stimuli were presented near the top or bottom points of the tremor cycle. Anticipatory muscle tension is another physiological factor that early researchers found as a predictor of response times, wherein muscle tension is interpreted as an index of cortical arousal level. That is, if physiological arousal state is high upon stimulus onset, greater preexisting muscular tension facilitates faster responses; if arousal is low, weaker muscle tension predicts slower response. However, too much arousal (and therefore muscle tension) was also found to negatively affect performance on RT tasks as a consequence of an impaired signal-to-noise ratio. As with many sensory manipulations, such physiological response characteristics as predictors of RT operate largely outside of central processing, which differentiates these effects from those of preparation, discussed below.Preparation

Another observation first made by early chronometric research was that a "warning" sign preceding the appearance of a stimulus typically resulted in shorter reaction times. This short warning period, referred to as "expectancy" in this foundational work, is measured in simple RT tasks as the length of the intervals between the warning and the presentation of the stimulus to be reacted to. The importance of the length and variability of expectancy in mental chronometry research was first observed in the early 1900s, and remains an important consideration in modern research. It is reflected today in modern research in the use of a variable ''foreperiod'' that precedes stimulus presentation. This relationship can be summarized in simple terms by the equation: : where and are constants related to the task and denotes the probability of a stimulus appearing at any given time. In simple RT tasks, constant foreperiods of about 300 ms over a series of trials tends to produce the fastest responses for a given individual, and responses lengthen as the foreperiod becomes longer, an effect that has been demonstrated up to foreperiods of many hundreds of seconds. Foreperiods of variable interval, if presented in equal frequency but in random order, tend to produce slower RTs when the intervals are shorter than the mean of the series, and can be faster or slower when greater than the mean. Whether held constant or variable, foreperiods of less than 300 ms may produce delayed RTs because processing of the warning may not have had time to complete before the stimulus arrives. This type of delay has significant implications for the question of serially-organized central processing, a complex topic that has received much empirical attention in the century following this foundational work.Choice

The number of possible options was recognized early as a significant determinant of response time, with reaction times lengthening as a function of both the number of possible signals and possible responses. The first scientist to recognize the importance of response options on RT was Franciscus Donders (1869). Donders found that simple RT is shorter than recognition RT, and that choice RT is longer than both. Donders also devised a subtraction method to analyze the time it took for mental operations to take place. By subtracting simple RT from choice RT, for example, it is possible to calculate how much time is needed to make the connection. This method provides a way to investigate the cognitive processes underlying simple perceptual-motor tasks, and formed the basis of subsequent developments. (Original work published in 1868.) Although Donders' work paved the way for future research in mental chronometry tests, it was not without its drawbacks. His insertion method, often referred to as "pure insertion", was based on the assumption that inserting a particular complicating requirement into an RT paradigm would not affect the other components of the test. This assumption—that the incremental effect on RT was strictly additive—was not able to hold up to later experimental tests, which showed that the insertions were able to interact with other portions of the RT paradigm. Despite this, Donders' theories are still of interest and his ideas are still used in certain areas of psychology, which now have the statistical tools to use them more accurately.)Conscious accompaniments

The interest in the content of consciousness that typified early studies of Wundt and other structuralist psychologists largely fell out of favor with the advent of behaviorism in the 1920s. Nevertheless, the study of conscious accompaniments in the context of reaction time was an important historical development in the late 1800s and early 1900s. For example, Wundt and his associate Oswald Külpe often studied reaction time by asking participants to describe the conscious process that occurred during performance on such tasks.Measurement and mathematical descriptions

Chronometric measurements from standard reaction time paradigms are raw values of time elapsed between stimulus onset and motor response. These times are typically measured in milliseconds (ms), and are considered to be ratio scale measurements with equal intervals and a true zero. Response time on chronometric tasks are typically concerned with five categories of measurement: Central tendency of response time across a number of individual trials for a given person or task condition, usually captured by theDistribution of response times

Reaction times trials of any given individual are always distributed non-symmetrically and skewed to the right, therefore rarely following a normal (Gaussian) distribution. The typical observed pattern is that mean RT will always be a larger value than median RT, and median RT will be a greater value than the maximum height of the distribution (mode). One of the most obvious reasons for this standard pattern is that while it is possible for any number of factors to extend the response time of a given trial, it is not physiologically possible to shorten RT on a given trial past the limits of human perception (typically considered to be somewhere between 100 and 200 ms), nor is it logically possible for the duration of a trial to be negative. One reason for variability that extends the right tail of an individual's RT distribution is momentary attentional lapses. To improve the reliability of individual response times, researchers typically require a subject to perform multiple trials, from which a measure of the 'typical' or baseline response time can be calculated. Taking the mean of the raw response time is rarely an effective method of characterizing the typical response time, and alternative approaches (such as modeling the entire response time distribution) are often more appropriate. A number of different approaches have been developed to analyze RT measurements, particularly in how to effectively deal with issues that arise from trimming outliers, data transformations, measurement reliability speed-accuracy tradeoffs, mixture models, convolution models, stochastic orders related comparisons, and the mathematical modeling ofHick's law

Building on Donders' early observations of the effects of number of response options on RT duration, W. E. Hick (1952) devised an RT experiment which presented a series of nine tests in which there are ''n'' equally possible choices. The experiment measured the subject's RT based on the number of possible choices during any given trial. Hick showed that the individual's RT increased by a constant amount as a function of available choices, or the "uncertainty" involved in which reaction stimulus would appear next. Uncertainty is measured in "bits", which are defined as the quantity of information that reduces uncertainty by half inDrift-diffusion model

The drift-diffusion model (DDM) is a well-defined mathematical formulation to explain observed variance in response times and accuracy across trials in a (typically two-choice) reaction time task. This model and its variants account for these distributional features by partitioning a reaction time trial into a non-decision residual stage and a stochastic "diffusion" stage, where the actual response decision is generated. The distribution of reaction times across trials is determined by the rate at which evidence accumulates in neurons with an underlying "random walk" component. The drift rate (''v'') is the average rate at which this evidence accumulates in the presence of this random noise. The decision threshold (''a'') represents the width of the decision boundary, or the amount of evidence needed before a response is made. The trial terminates when the accumulating evidence reaches either the correct or the incorrect boundary.Standard reaction time paradigms

Modern chronometric research typically uses variations on one or more of the following broad categories of reaction time task paradigms, which need not be mutually exclusive in all cases.Simple RT paradigms

''Simple'' reaction time is the motion required for an observer to respond to the presence of a stimulus. For example, a subject might be asked to press a button as soon as a light or sound appears. Mean RT for college-age individuals is about 160 milliseconds to detect an auditory stimulus, and approximately 190 milliseconds to detect visual stimulus. The mean RTs for sprinters at the Beijing Olympics were 166 ms for males and 169 ms for females, but in one out of 1,000 starts they can achieve 109 ms and 121 ms, respectively. This study also concluded that longer female RTs can be an artifact of the measurement method used, suggesting that the starting block sensor system might overlook a female false-start due to insufficient pressure on the pads. The authors suggested compensating for this threshold would improve false-start detection accuracy with female runners. The IAAF has a controversial rule that if an athlete moves in less than 100 ms, it counts as aRecognition or go/no-go paradigms

''Recognition'' or ''go/no-go'' RT tasks require that the subject press a button when one stimulus type appears and withhold a response when another stimulus type appears. For example, the subject may have to press the button when a green light appears and not respond when a blue light appears.Discrimination paradigms

''Discrimination'' RT involves comparing pairs of simultaneously presented visual displays and then pressing one of two buttons according to which display appears brighter, longer, heavier, or greater in magnitude on some dimension of interest. Discrimination RT paradigms fall into three basic categories, involving stimuli that are administered simultaneously, sequentially, or continuously. In a classic example of a simultaneous discrimination RT paradigm, conceived by social psychologist Leon Festinger, two vertical lines of differing lengths are shown side-by-side to participants simultaneously. Participants are asked to identify as quickly as possible whether the line on the right is longer or shorter than the line on the left. One of these lines would retain a constant length across trials, while the other took on a range of 15 different values, each one presented an equal number of times across the session. An example of the second type of discrimination paradigm, which administers stimuli successfully or serially, is a classic 1963 study in which participants are given two sequentially lifted weights and asked to judge whether the second was heavier or lighter than the first. The third broad type of discrimination RT task, wherein stimuli are administered continuously, is exemplified by a 1955 experiment in which participants are asked to sort packs of shuffled playing cards into two piles depending on whether the card had a large or small number of dots on its back. Reaction time in such a task is often measured by the total amount of time it takes to complete the task.Choice RT paradigms

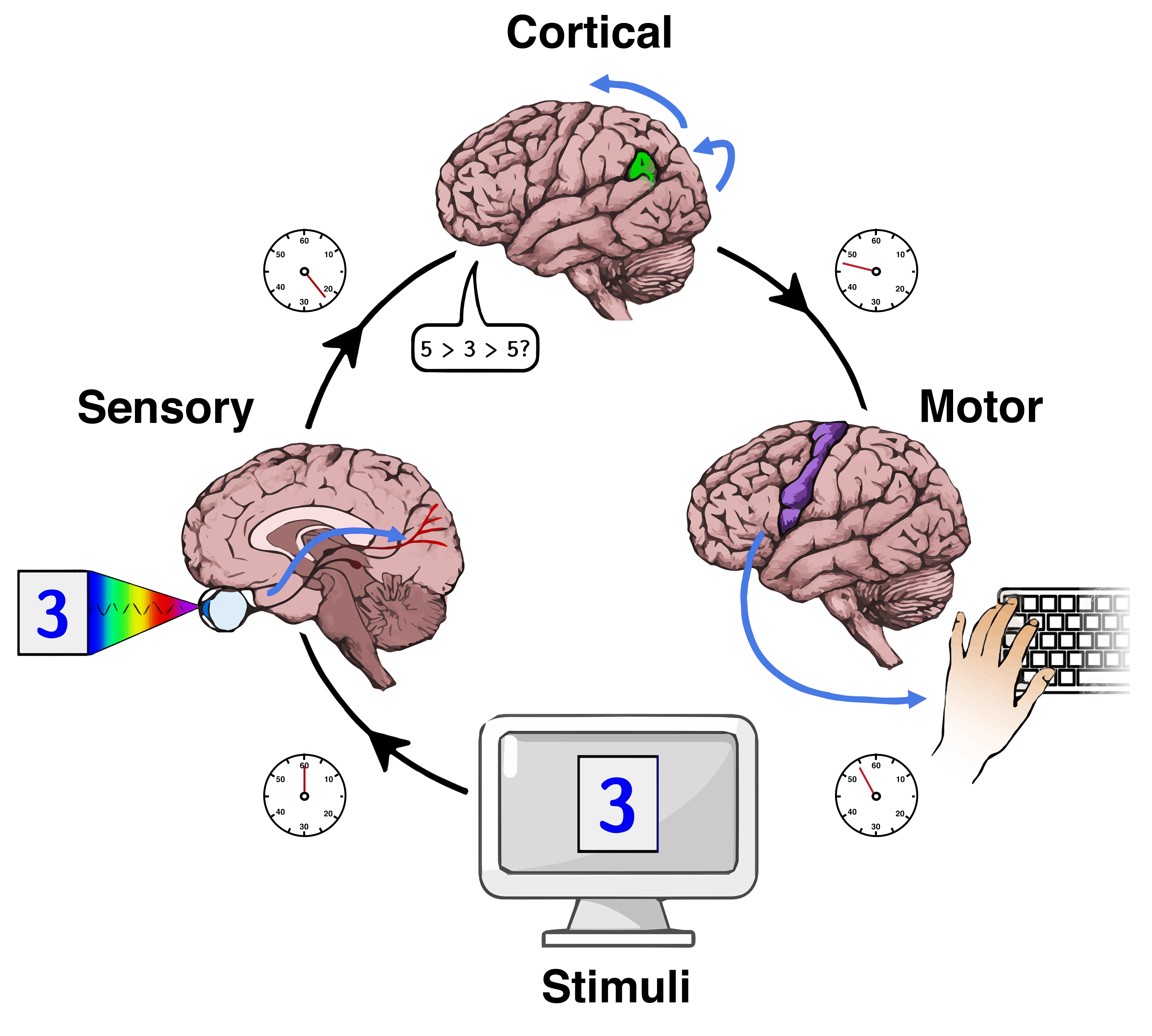

''Choice'' reaction time (CRT) tasks require distinct responses for each possible class of stimulus. In a choice reaction time task which calls for a single response to several different signals, four distinct processes are thought to occur in sequence: First, the sensory qualities of the stimuli are received by the sensory organs and transmitted to the brain; second, the signal is identified, processed, and reasoned by the individual; third, the choice decision is made; and fourth, the motor response corresponding to that choice is initiated and carried out by an action. CRT tasks can be highly variable. They can involve stimuli of any sensory modality, most typically of visual or auditory nature, and require responses that are typically indicated by pressing a key or button. For example, the subject might be asked to press one button if a red light appears and a different button if a yellow light appears. The Jensen box is an example of an instrument designed to measure choice RT with visual stimuli and keypress response. Response criteria can also be in the form of vocalizations, such as the original version of the Stroop task, where participants are instructed to read the names of words printed in colored ink from lists. Modern versions of the Stroop task, which use single stimulus pairs for each trial, are also examples of a multi-choice CRT paradigm with vocal responding. Models of choice reaction time are closely aligned with Hick's Law, which posits that average reaction times lengthen as a function of more available choices. Hick's law can be reformulated as: :, where denotes mean RT across trials, is a constant, and represents the sum of possibilities including "no signal". This accounts for the fact that in a choice task, the subject must not only make a choice but also first detect whether a signal has occurred at all (equivalent to in the original formulation).Application in biological psychology/cognitive neuroscience

With the advent of the functionalReaction time as a function of experimental conditions

The assumption that mental operations can be measured by the time required to perform them is considered foundational to modern cognitive psychology. To understand how different brain systems acquire, process and respond to stimuli through the time course of information processing by the nervous system, experimental psychologists often use response times as a dependent variable under different experimental conditions. This approach to the study of mental chronometry is typically aimed at testing theory-driven hypotheses intended to explain observed relationships between measured RT and some experimentally manipulated variable of interest, which often make precisely formulated mathematical predictions. The distinction between this experimental approach and the use of chronometric tools to investigate individual differences is more conceptual than practical, and many modern researchers integrate tools, theories and models from both areas to investigate psychological phenomena. Nevertheless, it is a useful organizing principle to distinguish the two areas in terms of their research questions and the purposes for which a number of chronometric tasks were devised. The experimental approach to mental chronometry has been used to investigate a variety of cognitive systems and functions that are common to all humans, including memory, language processing and production, attention, and aspects of visual and auditory perception. The following is a brief overview of several well-known experimental tasks in mental chronometry.Sternberg's memory-scanning task

Shepard and Metzler's mental rotation task

Shepard and Metzler (1971) presented a pair of three-dimensional shapes that were identical or mirror-image versions of one another. RT to determine whether they were identical or not was a linear function of the angular difference between their orientation, whether in the picture plane or in depth. They concluded that the observers performed a constant-rate mental rotation to align the two objects so they could be compared. Cooper and Shepard (1973) presented a letter or digit that was either normal or mirror-reversed, and presented either upright or at angles of rotation in units of 60 degrees. The subject had to identify whether the stimulus was normal or mirror-reversed. Response time increased roughly linearly as the orientation of the letter deviated from upright (0 degrees) to inverted (180 degrees), and then decreases again until it reaches 360 degrees. The authors concluded that the subjects mentally rotate the image the shortest distance to upright, and then judge whether it is normal or mirror-reversed.Sentence-picture verification

Mental chronometry has been used in identifying some of the processes associated with understanding a sentence. This type of research typically revolves around the differences in processing four types of sentences: true affirmative (TA), false affirmative (FA), false negative (FN), and true negative (TN). A picture can be presented with an associated sentence that falls into one of these four categories. The subject then decides if the sentence matches the picture or does not. The type of sentence determines how many processes need to be performed before a decision can be made. According to the data from Clark and Chase (1972) and Just and Carpenter (1971), the TA sentences are the simplest and take the least time, than FA, FN, and TN sentences.Models of memory

Hierarchical network models of memory were largely discarded due to some findings related to mental chronometry. The Teachable Language Comprehender (TLC) model proposed by Collins and Quillian (1969) had a hierarchical structure indicating that recall speed in memory should be based on the number of levels in memory traversed in order to find the necessary information. But the experimental results did not agree. For example, a subject will reliably answer that a robin is a bird more quickly than he will answer that an ostrich is a bird despite these questions accessing the same two levels in memory. This led to the development of spreading activation models of memory (e.g., Collins & Loftus, 1975), wherein links in memory are not organized hierarchically but by importance instead.Posner's letter matching studies

In the late 1960s, Michael Posner developed a series of letter-matching studies to measure the mental processing time of several tasks associated with recognition of a pair of letters. The simplest task was the physical match task, in which subjects were shown a pair of letters and had to identify whether the two letters were physically identical or not. The next task was the name match task where subjects had to identify whether two letters had the same name. The task involving the most cognitive processes was the rule match task in which subjects had to determine whether the two letters presented both were vowels or not vowels. The physical match task was the most simple; subjects had to encode the letters, compare them to each other, and make a decision. When doing the name match task subjects were forced to add a cognitive step before making a decision: they had to search memory for the names of the letters, and then compare those before deciding. In the rule based task they had to also categorize the letters as either vowels or consonants before making their choice. The time taken to perform the rule match task was longer than the name match task which was longer than the physical match task. Using the subtraction method experimenters were able to determine the approximate amount of time that it took for subjects to perform each of the cognitive processes associated with each of these tasks.Reaction time as a function of individual differences

Differential psychologists frequently investigate the causes and consequences of information processing modeled by chronometric studies from experimental psychology. While traditional experimental studies of RT are conducted within-subjects with RT as a dependent measure affected by experimental manipulations, a differential psychologist studying RT will typically hold conditions constant to ascertain between-subjects variability in RT and its relationships with other psychological variables.Cognitive ability

Researchers spanning more than a century have generally reported medium-sized correlations between RT and measures ofMechanistic properties of the RT-cognitive ability relationship

Researchers have yet to develop consensus for a unified neurophysiological theory that fully explains the basis of the relationship between RT and cognitive ability. It may reflect more efficient information processing, better attentional control, or the integrity of neuronal processes. Such a theory would need to explain several unique features of the relationship, several of which are discussed below. # The serial components of a reaction time trial are not equally dependent on general intelligence or psychometric ''g''. For example, researchers have found that the perceptual processing of multiple stimuli, which necessarily precedes the decision to respond and the response itself, can be processed in parallel, while the decision component must be processed serially. Moreover, variation in general intelligence is chiefly represented in this decision component of RT, while sensory processing and movement time appear to be mostly reflective of non-''g'' individual differences. # The correlation between cognitive ability and RT increases as a function of task complexity. The difference in the correlation between intelligence and RT in simple and multi-choice RT paradigms exemplifies the much-replicated finding that this association is largely mediated by the number of choices available in the task. Much of the theoretical interest in RT was driven by Hick's Law, relating the slope of RT increases to the complexity of decision required (measured in units of uncertainty popularized by Claude Shannon as the basis of information theory). This promised to link intelligence directly to the resolution of information even in very basic information tasks. There is some support for a link between the slope of the RT curve and intelligence, as long as reaction time is tightly controlled. The notion of "bits" of information affecting the size of this relationship has been popularized by Arthur Jensen and the Jensen box tool, and the " choice reaction apparatus" associated with his name became a common standard tool in RT-IQ research. # Mean response time and variability in RT trials both contribute independent variance in their association with ''g''. Standard deviations of RTs have been found to be as strongly or more strongly correlated with measures of general intelligence (''g'') than mean RTs, with greater variance or "spread-outedness" in an individual's distribution of RTs more strongly associated with lower ''g'', while higher-''g'' individuals tend to have less variable responses. # When multiple measures of RT are studied in a population, factor analysis indicates the existence of a general factor of reaction time, sometimes labeled as ''G'', which is both related to and distinct from psychometric ''g''. This big-''G'' of RT has been found to explain over 50% of the variance in RTs when meta-analyzed over four studies, which included nine separate RT paradigms. The biological and neurophysiological underpinnings of this general factor have yet to be firmly established, though research is ongoing. # The slowest of an individual's RT trials tend to be more strongly associated with cognitive ability than the individual's fastest responses, a phenomenon known as the "worst performance rule".Biological and neurophysiological manifestations of the RT-''g'' relationship

Twin and adoption studies have shown that performance on chronometric tasks isDiffusion modeling of RT and cognitive ability

Although a unified theory of reaction time and intelligence has yet to achieve consensus among psychologists, diffusion modeling provides one promising theoretical model. Diffusion modeling partitions RT into residual "non-decision" and stochastic "diffusion" stages, the latter of which represents the generation of a decision in a two-choice task. This model successfully integrates the roles of mean reaction time, response time variability, and accuracy in modeling the rate of diffusion as a variable representing the accumulated weight of evidence that generates a decision in an RT task. Under the diffusion model, this evidence accumulates by undertaking a continuous random walk between two boundaries that represent each response choice in the task. Applications of this model have shown that the basis of the ''g''-RT relationship is specifically the relationship of ''g'' with the rate of the diffusion process, rather than with the non-decision residual time. Diffusion modeling can also successfully explain the worst performance rule by assuming that the same measure of ability (diffusion rate) mediates performance on both simple and complex cognitive tasks, which has been theoretically and empirically supported. This section elaborates on how the diffusion model helps explain the RT-cognitive ability relationship. Increased clarity could involve a mixture of technical vocabulary with some particularly evocative examples. For instance, a metaphor from a balance scale beginning to tip one way or another as accumulating evidence is one way to make it clearer. And the vivid examples can be real-world situations, like deliberating on a decision being compared with analyzing evidence in a courtroom. This blend of technical vocabulary with practical examples allows the reader to gain a deeper understanding of how the diffusion model works in relation to cognitive studies.Cognitive development

There is extensive recent research using mental chronometry for the study ofHealth and mortality

Performance on simple and choice reaction time tasks is associated with a variety of health-related outcomes, including general, objective health composites as well as specific measures like cardiorespiratory integrity. The association between IQ and earlier all-cause mortality has been found to be chiefly mediated by a measure of reaction time. These studies generally find that faster and more accurate responses to reaction time tasks are associated with better health outcomes and longer lifespan.Big-Five personality traits

Several researchers have reported associations between RT and the Big Five personality factors ofReaction time as a function of different analytical choices

Metascientists frequently investigate the order in which our analytical choices affect the analyses on reaction time. The effect of preprocessing weakens inferences scientific evidence, it can be seen as different but rational, leading to conflicting results, false positives and negatives. The effect of choosing certain pre-processing methods needs to be considered first, and then, secondly, one needs to disclose this choice as to allow for future replication studies. As a result, a systematic literature review on the Simon effect revealed that the order in which analytical choices are conducted are rarely reported and findings within the Simon effects was affected different analytical choices. As a result, a checklist to report reaction time pre-processing to make the decisions more explicit and transparency has been recommended to make the reaction time data more transparent in order to maximise transparency within reaction time data.See also

* CDR computerized assessment system * Implicit-association test * Inspection time * Jensen box * Movement in learning * Psychomotor agitation * Psychomotor learning * Psychomotor retardation * Timed antagonistic response alethiometerReferences

Further reading

* * * *External links

Reaction Time Test

– Measuring Mental Chronometry on the Web

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mental Chronometry Cognition Time in life