The history of Denmark as a

unified kingdom began in the 8th century, but historic documents describe the geographic area and the people living there—the

Danes

Danes (, ), or Danish people, are an ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

History

Early history

Denmark ...

—as early as 500 AD. These early documents include the writings of

Jordanes

Jordanes (; Greek language, Greek: Ιορδάνης), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat, claimed to be of Goths, Gothic descent, who became a historian later in life.

He wrote two works, one on R ...

and

Procopius

Procopius of Caesarea (; ''Prokópios ho Kaisareús''; ; – 565) was a prominent Late antiquity, late antique Byzantine Greeks, Greek scholar and historian from Caesarea Maritima. Accompanying the Roman general Belisarius in Justinian I, Empe ...

. With the

Christianization of the Danes c. 960 AD, it is clear that there existed a kingship. King

Frederik X

Frederik X (Frederik André Henrik Christian, ; born 26 May 1968) is King of Denmark. He acceded to the throne following Abdication of Margrethe II, his mother's abdication in 2024.

Frederik is the eldest son of Margrethe II and Prince Henri ...

can trace his lineage back to the

Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

kings

Gorm the Old

Gorm the Old (; ; ), also called Gorm the Languid (), was List of Danish monarchs, ruler of Denmark, reigning from to his death or a few years later.Lund, N. (2020), p. 147 and

Harald Bluetooth

Harald "Bluetooth" Gormsson (; , died c. 985/86) was a king of Denmark and Norway.

The son of King Gorm the Old and Thyra Dannebod, Harald ruled as king of Denmark from c. 958 – c. 986, introduced Christianization of Denmark, Christianity to D ...

from this time, thus making the

Monarchy of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous territories of the Faroe Islands and Greenland. The Kingdom of Denmark was alrea ...

the oldest in Europe. The area now known as Denmark has a rich

prehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, having been populated by several prehistoric cultures and people for about 12,000 years, since the end of the

last ice age.

Denmark's history has particularly been influenced by its geographical location between the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and

Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

seas, a strategically and economically important placement between

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, at the center of mutual struggles for control of the Baltic Sea (). Denmark was long in disputes with Sweden over control of

Skånelandene and with Germany over control of

Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been di ...

(a Danish

fief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

) and

Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

(a German fief).

Eventually, Denmark lost these conflicts and ended up ceding first

Skåneland

Skåneland is a region on the southern Scandinavian Peninsula. It includes the Sweden, Swedish provinces of Sweden, provinces of Blekinge, Halland, and Skåne, Scania. The Denmark, Danish island of Bornholm is traditionally also included.For pop ...

to Sweden and later

Schleswig-Holstein

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the Northern Germany, northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of S ...

to the

German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

. After the eventual cession of

Norway in 1814

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of Norway. Bouvet ...

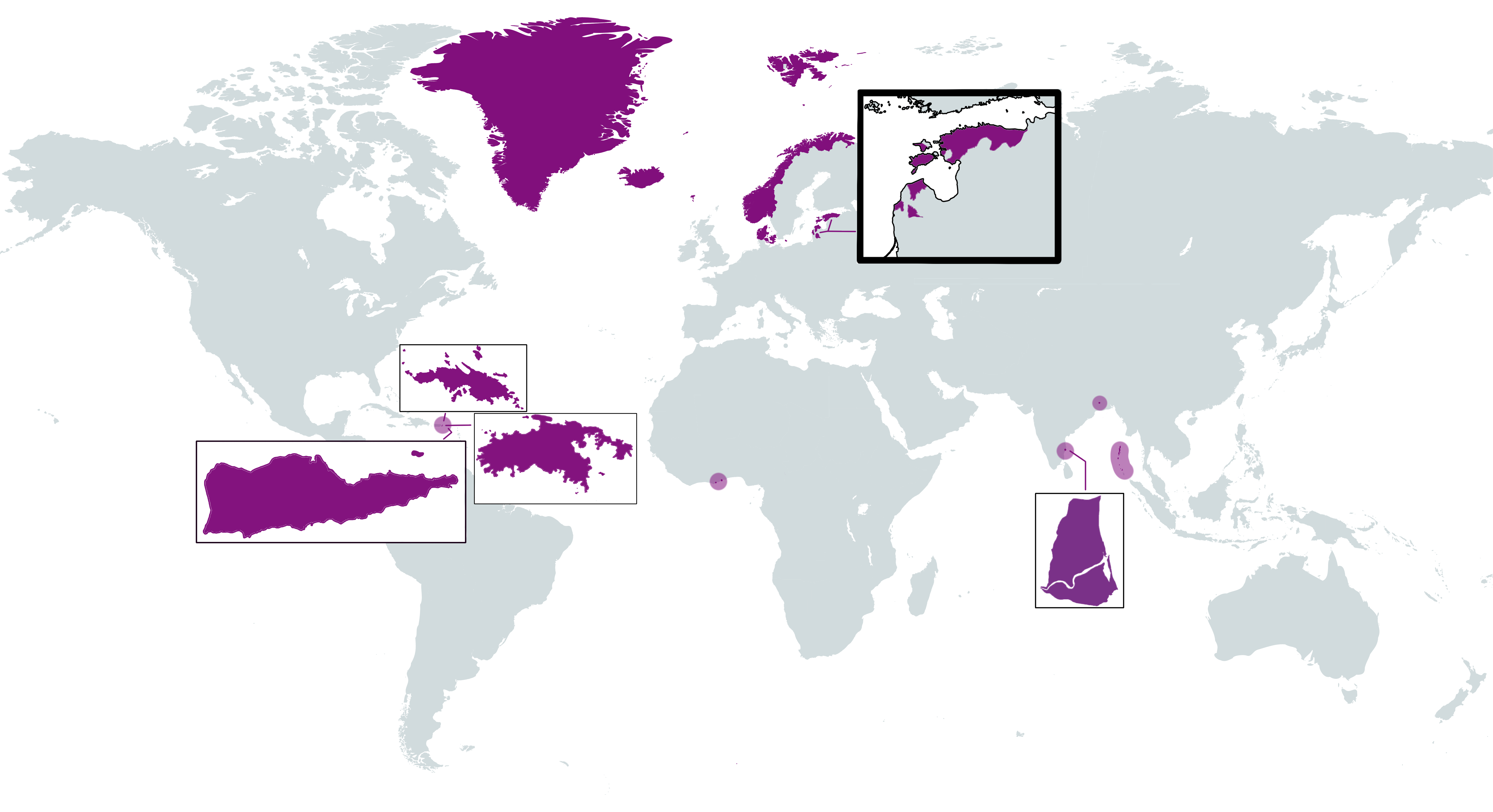

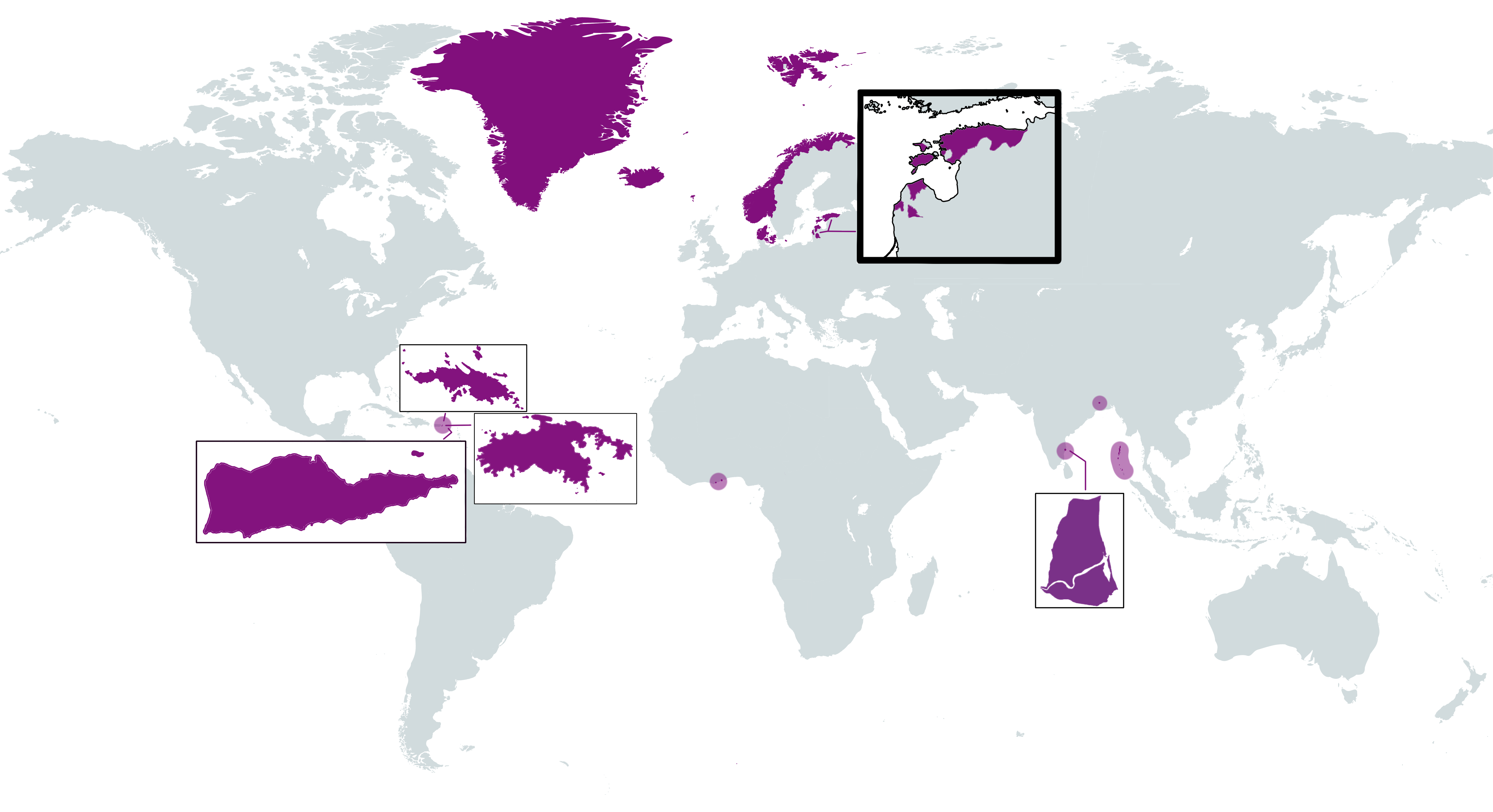

, Denmark retained control of the old Norwegian colonies of the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

,

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and

Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

. During the 20th century, Iceland gained independence, Greenland and the Faroes became integral parts of the

Kingdom of Denmark

The Danish Realm, officially the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply Denmark, is a sovereign state consisting of a collection of constituent territories united by the Constitution of Denmark, Constitutional Act, which applies to the entire territor ...

and

North Schleswig

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' is ...

reunited with Denmark in 1920 after a referendum. During

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Denmark was

occupied by

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, but was eventually liberated by British forces of the

Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

in 1945, after which it joined the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

. In the aftermath of World War II, and with the emergence of the subsequent

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, Denmark was quick to join the military alliance of

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO ; , OTAN), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental Transnationalism, transnational military alliance of 32 Member states of NATO, member s ...

as a founding member in 1949.

Prehistoric Denmark

The Scandinavian region has a rich

prehistory

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the first known use of stone tools by hominins million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use ...

, having been populated by several prehistoric cultures and people for about 12,000 years, since the end of the

last ice age. During the ice age, all of Scandinavia was covered by

glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s most of the time, except for the southwestern parts of what we now know as Denmark. When the ice began retreating, the barren tundras were soon inhabited by reindeer and elk, and

Ahrenburg and

Swiderian hunters from the south followed them here to hunt occasionally. The geography then was very different from what we know today. Sea levels were much lower; the island of

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-west coast of continental Europe, consisting of the countries England, Scotland, and Wales. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the List of European ...

was connected by a land bridge to mainland Europe and the large area between Great Britain and the

Jutlandic peninsula – now beneath the

North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

and known as

Doggerland

Doggerland was a large area of land in Northern Europe, now submerged beneath the southern North Sea. This region was repeatedly exposed at various times during the Pleistocene epoch due to the lowering of sea levels during glacial periods. Howe ...

– was inhabited by tribes of hunter-gatherers. As the climate warmed up, forceful rivers of meltwater started to flow and shape the virgin lands, and more stable flora and fauna gradually began emerging in Scandinavia, and Denmark in particular. The first human settlers to inhabit Denmark and Scandinavia permanently were the

Maglemosian people, residing in seasonal camps and exploiting the land, sea, rivers and lakes. It was not until around 6,000 BC that the approximate geography of Denmark as we know it today had been shaped.

Denmark has some unique natural conditions for preservation of artifacts, providing

a rich and diverse archeological record from which to understand the prehistoric cultures of this area.

Stone and Bronze Age

History of Denmark

The

Weichsel glaciation Weichsel may refer to:

* Vistula river (Weichsel in German)

* Weichselian glaciation

* Peter Weichsel

Peter M. Weichsel (born 1943) is an American professional bridge player from Encinitas, California.

College and war years

Early Weichsel st ...

covered all of Denmark most of the time, except the western coasts of Jutland. It ended around 13,000 years ago, allowing humans to move back into the previously ice-covered territories and establish permanent habitation. During the first post-glacial millennia, the landscape gradually changed from

tundra

In physical geography, a tundra () is a type of biome where tree growth is hindered by frigid temperatures and short growing seasons. There are three regions and associated types of tundra: #Arctic, Arctic, Alpine tundra, Alpine, and #Antarctic ...

to light forest, and varied fauna including now-extinct

megafauna

In zoology, megafauna (from Ancient Greek, Greek μέγας ''megas'' "large" and Neo-Latin ''fauna'' "animal life") are large animals. The precise definition of the term varies widely, though a common threshold is approximately , this lower en ...

appeared. Early prehistoric cultures uncovered in modern Denmark include the

Maglemosian culture

Maglemosian ( 9000 – 6000 BC) is the name given to a culture of the early Mesolithic period in Northern Europe. In Scandinavia, the culture was succeeded by the Kongemose culture.

Environment and location

The name originates fr ...

(9,500–6,000 BC); the

Kongemose culture

The Kongemose culture (''Kongemosekulturen'') was a Mesolithic hunter-gatherer culture in southern Scandinavia ca. 6000 BC– 5200 BC and the origin of the Ertebølle culture. It was preceded by the Maglemosian culture. In the north it bordere ...

(6,000–5,200 BC), the

Ertebølle culture

The Ertebølle culture ( BCE – 3,950 BCE) () is a hunter-gatherer and fisher, pottery-making culture dating to the end of the Mesolithic period. The culture was concentrated in Southern Scandinavia. It is named after the type site, a loc ...

(5,300–3,950 BC), and the

Funnelbeaker culture

The Funnel(-neck-)beaker culture, in short TRB or TBK (, ; ; ), was an archaeological culture in north-central Europe.

It developed as a technological merger of local neolithic and mesolithic techno-complexes between the lower Elbe and middle V ...

(4,100–2,800 BC).

The first inhabitants of this early post-glacial landscape in the so-called

Boreal period, were very small and scattered populations living from hunting of

reindeer

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, taiga, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only re ...

and other land mammals and gathering whatever fruits the climate was able to offer. Around 8,300 BC the temperature rose drastically, now with summer temperatures around 15 degrees Celsius (59 degrees Fahrenheit), and the landscape changed into dense forests of

aspen

Aspen is a common name for certain tree species in the Populus sect. Populus, of the ''Populus'' (poplar) genus.

Species

These species are called aspens:

* ''Populus adenopoda'' – Chinese aspen (China, south of ''P. tremula'')

* ''Populus da ...

,

birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

and

pine

A pine is any conifer tree or shrub in the genus ''Pinus'' () of the family Pinaceae. ''Pinus'' is the sole genus in the subfamily Pinoideae.

''World Flora Online'' accepts 134 species-rank taxa (119 species and 15 nothospecies) of pines as cu ...

and the reindeer moved north, while

aurochs

The aurochs (''Bos primigenius''; or ; pl.: aurochs or aurochsen) is an extinct species of Bovini, bovine, considered to be the wild ancestor of modern domestic cattle. With a shoulder height of up to in bulls and in cows, it was one of t ...

and

elk

The elk (: ''elk'' or ''elks''; ''Cervus canadensis'') or wapiti, is the second largest species within the deer family, Cervidae, and one of the largest terrestrial mammals in its native range of North America and Central and East Asia. ...

arrived from the south. The

Koelbjerg Man

The Koelbjerg Man, formerly known as "Koelbjerg Woman", is the oldest known bog body and also the oldest set of human bones found in Denmark,Museum OdenseDen ældste dansker er en mand.Retrieved 3 April 2017. dated to the time of the Maglemosian ...

is the oldest known

bog body

A bog body is a human cadaver that has been naturally mummified in a peat bog. Such bodies, sometimes known as bog people, are both geographically and chronologically widespread, having been dated to between 8000 BC and the Second World War. Fi ...

in the world and also the oldest set of human bones found in

Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, dated to the time of the

Maglemosian culture

Maglemosian ( 9000 – 6000 BC) is the name given to a culture of the early Mesolithic period in Northern Europe. In Scandinavia, the culture was succeeded by the Kongemose culture.

Environment and location

The name originates fr ...

around 8,000 BC. With a continuing rise in temperature the

oak

An oak is a hardwood tree or shrub in the genus ''Quercus'' of the beech family. They have spirally arranged leaves, often with lobed edges, and a nut called an acorn, borne within a cup. The genus is widely distributed in the Northern Hemisp ...

,

elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

and

hazel

Hazels are plants of the genus ''Corylus'' of deciduous trees and large shrubs native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. The genus is usually placed in the birch family, Betulaceae,Germplasmgobills Information Network''Corylus''Rushforth, K ...

arrived in Denmark around 7,000 BC. Now

boar

The wild boar (''Sus scrofa''), also known as the wild swine, common wild pig, Eurasian wild pig, or simply wild pig, is a Suidae, suid native to much of Eurasia and North Africa, and has been introduced to the Americas and Oceania. The speci ...

,

red deer

The red deer (''Cervus elaphus'') is one of the largest deer species. A male red deer is called a stag or Hart (deer), hart, and a female is called a doe or hind. The red deer inhabits most of Europe, the Caucasus Mountains region, Anatolia, Ir ...

, and

roe deer also began to abound.

A burial from Bøgebakken at

Vedbæk

Vedbæk is a wealthy suburban neighbourhood on the coast north of Copenhagen, Denmark. It belongs to Rudersdal Municipality and has merged with the town of Hørsholm to the north. The area has been inhabited for at least 7,000 years, as evidenced ...

dates to c. 6,000 BC and contains 22 persons – including four newborns and one toddler. Eight of the 22 had died before reaching 20 years of age – testifying to the hardness of hunter-gatherer life in the cold north. Based on estimates of the amount of game animals, scholars estimate the population of Denmark to have been between 3,300 and 8,000 persons in the time around 7,000 BC. It is believed that the early hunter-gatherers lived nomadically, exploiting different environments at different times of the year, gradually shifting to the use of semi permanent base camps.

With the rising temperatures, sea levels also rose, and during the

Atlantic period

The Atlantic in palaeoclimatology was the warmest and moistest Blytt–Sernander period, pollen zone and chronozone of Holocene northern Europe. The climate was generally warmer than today. It was preceded by the Boreal, with a climate similar ...

, Denmark evolved from a contiguous landmass around 11,000 BC to a series of islands by 4,500 BC. The inhabitants then shifted to a seafood based diet, which allowed the population to increase.

Agricultural

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created f ...

settlers made inroads around 4,000 BC. Many

dolmen

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber Megalith#Tombs, megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (4000 ...

s and rock tombs (especially

passage grave

A passage grave or passage tomb consists of one or more burial chambers covered in earth or stone and having a narrow access passage made of large stones. These structures usually date from the Neolithic Age and are found largely in Western Europ ...

s) date from this period. The

Funnelbeaker farmers replaced the Ertebølle culture, which had maintained a

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic (Ancient Greek language, Greek: μέσος, ''mesos'' 'middle' + λίθος, ''lithos'' 'stone') or Middle Stone Age is the Old World archaeological period between the Upper Paleolithic and the Neolithic. The term Epipaleolithic i ...

lifestyle for about 1500 years after farming arrived in Central Europe. The Neolithic Funnelbeaker population persisted for around 1,000 years until people with

Steppe-derived ancestry started to arrive from Eastern Europe. The

Single Grave culture

The Single Grave culture () was a Chalcolithic culture which flourished on the western North European Plain from ca. 2,800 BC to 2,200 BC. It is characterized by the practice of single burial, the deceased usually being accompanied by a battle ax ...

was a local variant of the

Corded Ware culture

The Corded Ware culture comprises a broad archaeological horizon of Europe between – 2350 BC, thus from the Late Neolithic, through the Copper Age, and ending in the early Bronze Age. Corded Ware culture encompassed a vast area, from t ...

, and appears to have emerged as a result of a migration of peoples from the Pontic–Caspian steppe. The

Nordic Bronze Age

The Nordic Bronze Age (also Northern Bronze Age, or Scandinavian Bronze Age) is a period of Scandinavian prehistory from .

The Nordic Bronze Age culture emerged about 1750 BC as a continuation of the Late Neolithic Dagger period, which is root ...

period in Denmark, from about 1,500 BC, featured a culture that buried its dead, with their worldly goods, beneath

burial mounds

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found throughout much of the world. ...

. The many finds of gold and bronze from this era include beautiful religious artifacts and musical instruments, and provide the earliest evidence of

social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

es and

stratification.

Iron Age

During the

Pre-Roman Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Northern Germany, Poland, the Netherlands and Belgium.

...

(from the

4th

Fourth or the fourth may refer to:

* the ordinal form of the number 4

* ''Fourth'' (album), by Soft Machine, 1971

* Fourth (angle), an ancient astronomical subdivision

* Fourth (music), a musical interval

* ''The Fourth'', a 1972 Soviet drama

...

to the

1st century BC

The 1st century Before Christ, BC, also known as the last century BC and the last century Common Era , BCE, started on the first day of 100 BC, 100 BC and ended on the last day of 1 BC, 1 BC. The Anno Domini, AD/BC notation does not ...

), the climate in Denmark and southern

Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

became cooler and wetter, limiting agriculture and setting the stage for local groups to migrate southward into

Germania

Germania ( ; ), also more specifically called Magna Germania (English: ''Great Germania''), Germania Libera (English: ''Free Germania''), or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman provinces of Germania Inferior and Germania Superio ...

. At around this time people began to extract iron from the

ore

Ore is natural rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the concentration ...

in

peat bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muske ...

s. Evidence of strong

Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

*Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Foot ...

cultural influence dates from this period in Denmark, and in much of northwest Europe, and survives in some of the older place names.

The

Roman provinces

The Roman provinces (, pl. ) were the administrative regions of Ancient Rome outside Roman Italy that were controlled by the Romans under the Roman Republic and later the Roman Empire. Each province was ruled by a Roman appointed as gover ...

, whose frontiers stopped short of Denmark, nevertheless maintained trade routes and relations with Danish or proto-Danish peoples, as attested by finds of Roman coins. The earliest known

runic

Runes are the letters in a set of related alphabets, known as runic rows, runic alphabets or futharks (also, see '' futhark'' vs ''runic alphabet''), native to the Germanic peoples. Runes were primarily used to represent a sound value (a ...

inscriptions date back to c. 200 AD. Depletion of cultivated land in the last century BC seems to have contributed to increasing migrations in northern Europe and increasing conflict between Teutonic tribes and Roman settlements in

Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

. Roman artifacts are especially common in finds from the 1st century. It seems clear that some part of the Danish warrior

aristocracy

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocracy (class), aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense Economy, economic, Politics, political, and soc ...

served in the

Roman army

The Roman army () served ancient Rome and the Roman people, enduring through the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC), the Roman Republic (509–27 BC), and the Roman Empire (27 BC–AD 1453), including the Western Roman Empire (collapsed Fall of the W ...

.

Occasionally during this time, both animal and

human sacrifice

Human sacrifice is the act of killing one or more humans as part of a ritual, which is usually intended to please or appease deity, gods, a human ruler, public or jurisdictional demands for justice by capital punishment, an authoritative/prie ...

occurred and bodies were immersed in

bog

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and musk ...

s. In some of these

bog bodies

A bog body is a human cadaver that has been Natural mummy, naturally mummified in a Bog, peat bog. Such bodies, sometimes known as bog people, are both geographically and chronologically widespread, having been dated to between 8000 BC and the S ...

have emerged very well-preserved, providing valuable information about the religion and people who lived in Denmark during this period. Some of the most well-preserved bog bodies from the Nordic Iron Age are the

Tollund Man

The Tollund Man (died 405–384 BC) is a naturally mummified corpse of a man who lived during the 5th century BC, during the period characterised in Scandinavia as the Pre-Roman Iron Age. He was found in 1950, preserved as a bog body near Sil ...

and the

Grauballe Man

The Grauballe Man is a bog body that was uncovered in 1952 from a peat bog near the village of Grauballe in Jutland, Denmark. The body is that of a man dating from the late 3rd century BC, during the early Germanic Iron Age. Based on the evidenc ...

.

From around the 5th to the 7th century,

Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54th parallel north, 54°N, or may be based on other ge ...

experienced mass migrations. This period and its

material culture

Material culture is culture manifested by the Artifact (archaeology), physical objects and architecture of a society. The term is primarily used in archaeology and anthropology, but is also of interest to sociology, geography and history. The fie ...

are referred to as the

Germanic Iron Age

The archaeology of Northern Europe studies the prehistory of Scandinavian Peninsula, Scandinavia and the adjacent North European Plain,

roughly corresponding to the territories of modern Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Northern Germany, Poland, the Net ...

.

File:Tollundmannen.jpg, The face of Tollundmanden, one of the best preserved bog body finds.

File:Dejbjerg wagon, Nationalmuseet Copenhagen.jpg, The Dejbjerg wagon

The Dejbjerg wagon (Danish ''Dejbjergvognen'') is a composite of two ceremonial wagons found in a peat bog in Dejbjerg near Ringkøbing in western Jutland, Denmark. These votive deposits were dismantled and ritually placed in the bog around 100 BCE ...

from the Pre-Roman Iron Age, thought to be a ceremonial wagon.

File:Nydamboat.2.jpg, The Nydam oak boat, a ship burial

A ship burial or boat grave is a burial in which a ship or boat is used either as the tomb for the dead and the grave goods, or as a part of the grave goods itself. If the ship is very small, it is called a boat grave. This style of burial was pr ...

from the Roman Iron Age. At Gottorp Castle, Schleswig

The Duchy of Schleswig (; ; ; ; ; ) was a duchy in Southern Jutland () covering the area between about 60 km (35 miles) north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been di ...

, now in Germany.

File:Guldhornene DO-10765 original.jpg, Copies of the Golden Horns of Gallehus from the Germanic Iron Age, thought to be ceremonial horns but of a raid purpose.

Middle Ages

Earliest literary sources

In his description of

Scandza

Scandza was described as a "great island" by Gothic-Byzantine historian Jordanes in his work ''Getica''. The island was located in the Arctic regions of the sea that surrounded the world. The location is usually identified with Scandinavia.

Jor ...

(from the 6th-century work, ''

Getica

''De origine actibusque Getarum'' (''The Origin and Deeds of the Getae''), commonly abbreviated ''Getica'' (), written in Late Latin by Jordanes in or shortly after 551 AD, claims to be a summary of a voluminous account by Cassiodorus of the ori ...

''), the ancient writer

Jordanes

Jordanes (; Greek language, Greek: Ιορδάνης), also written as Jordanis or Jornandes, was a 6th-century Eastern Roman bureaucrat, claimed to be of Goths, Gothic descent, who became a historian later in life.

He wrote two works, one on R ...

says that the Dani were of the same stock as the ''Suetidi'' (Swedes, ''

Suithiod''?) and expelled the

Heruli

The Heruli (also Eluri, Eruli, Herules, Herulians) were one of the smaller Germanic peoples of Late Antiquity, known from records in the third to sixth centuries AD.

The best recorded group of Heruli established a kingdom north of the Middle Danu ...

and took their lands.

The

Old English

Old English ( or , or ), or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. It developed from the languages brought to Great Britain by Anglo-S ...

poems ''

Widsith

"Widsith" (, "far-traveller", lit. "wide-journey"), also known as "The Traveller's Song", is an Old English poem of 143 lines. It survives only in the '' Exeter Book'' (''pages 84v–87r''), a manuscript of Old English poetry compiled in the la ...

'' and ''

Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ) is an Old English poetry, Old English poem, an Epic poetry, epic in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translat ...

'', as well as works by later Scandinavian writers — notably by

Saxo Grammaticus

Saxo Grammaticus (), also known as Saxo cognomine Longus, was a Danish historian, theologian and author. He is thought to have been a clerk or secretary to Absalon, Archbishop of Lund, the main advisor to Valdemar I of Denmark. He is the author ...

(c. 1200) — provide some of the earliest references to Danes.

Viking Age

With the beginning of the Viking Age in the 9th century, the prehistoric period in Denmark ends. The Danish people were among those known as

Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

s, during the 8th–11th centuries. Viking explorers first discovered and settled in

Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

in the 9th century, on their way from the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

. From there,

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

and

Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland () was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. The name appears in the V ...

(probably

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region of Labrador, having a total size of . As of 2025 the population ...

) were also settled. Utilizing their great skills in shipbuilding and navigation they raided and conquered parts of

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and the

British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

.

They also excelled in trading along the coasts and rivers of Europe, running trade routes from Greenland in the north to

Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

in the south via

Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

n and

Ukrainian rivers, most notably along the River

Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

and via Kiev, then being the capital of

Kiev Rus

Kievan Rus', also known as Kyivan Rus,.

* was the first East Slavs, East Slavic state and later an amalgam of principalities in Eastern Europe from the late 9th to the mid-13th century.John Channon & Robert Hudson, ''Penguin Historical At ...

, which was founded by Viking conquerors. The Danish Vikings were most active in Britain,

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

,

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

, Portugal and Italy where they raided, conquered and settled (their earliest settlements included sites in the

Danelaw

The Danelaw (, ; ; ) was the part of History of Anglo-Saxon England, England between the late ninth century and the Norman Conquest under Anglo-Saxon rule in which Danes (tribe), Danish laws applied. The Danelaw originated in the conquest and oc ...

,

Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

and

Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

). The Danelaw encompassed the Northeastern half of what now constitutes

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

, where Danes settled and Danish law and rule prevailed. Prior to this time, England consisted of approximately seven independent

Anglo-Saxon

The Anglo-Saxons, in some contexts simply called Saxons or the English, were a Cultural identity, cultural group who spoke Old English and inhabited much of what is now England and south-eastern Scotland in the Early Middle Ages. They traced t ...

kingdoms. The Danes conquered (terminated) all of these except for the kingdom of

Wessex

The Kingdom of the West Saxons, also known as the Kingdom of Wessex, was an Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from around 519 until Alfred the Great declared himself as King of the Anglo-Saxons in 886.

The Anglo-Sa ...

.

Alfred the Great

Alfred the Great ( ; – 26 October 899) was King of the West Saxons from 871 to 886, and King of the Anglo-Saxons from 886 until his death in 899. He was the youngest son of King Æthelwulf and his first wife Osburh, who both died when Alfr ...

, king of Wessex, emerged from these trials as the sole remaining English king, and thereby as the first English

Monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

.

In the early 9th century,

Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

's Christian empire had expanded to the southern border of the Danes, and Frankish sources (e.g.

Notker of St Gall

Notker the Stammerer ( – 6 April 912), Notker Balbulus, or simply Notker, was a Benedictine monk at the Abbey of Saint Gall active as a composer, poet and scholar. Described as "a significant figure in the Western Church", Notker made substan ...

) provide the earliest historical evidence of the Danes. These report a King

Gudfred

Gudfred was a ninth century Danish king who reigned from at least 804 to 810. Alternate spellings include ''Godfred'' (Danish), ''Göttrick'' (German), ''Gøtrik'' (Danish), ''Gudrød'' (Danish), and ''Godofredus'' (Latin). He stands at the thre ...

, who appeared in present-day

Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

with a navy in 804 where diplomacy took place with the

Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

; In 808, King Gudfred attacked the

Obotrites

The Obotrites (, ''Abodritorum'', ''Abodritos'') or Obodrites, also spelled Abodrites (), were a confederation of medieval West Slavic tribes within the territory of modern Mecklenburg and Holstein in northern Germany (see Polabian Slavs). For ...

and conquered the city of

Reric

Reric or Rerik was one of the Viking Age multi-ethnic Slavic- Scandinavian emporia on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, located near Wismar in the present-day German state of Mecklenburg-VorpommernOle Harck, Christian Lübke, Zwischen Reri ...

whose population was displaced or abducted to

Hedeby

Hedeby (, Old Norse: ''Heiðabýr'', German: ''Haithabu'') was an important Danish Viking Age (8th to the 11th centuries) trading settlement near the southern end of the Jutland Peninsula, now in the Schleswig-Flensburg district of Schleswig ...

. In 809, King Godfred and emissaries of Charlemagne failed to negotiate peace, despite the sister of Godfred being a concubine of Charlemagne, and the next year King Godfred attacked the

Frisians

The Frisians () are an ethnic group indigenous to the German Bight, coastal regions of the Netherlands, north-western Germany and southern Denmark. They inhabit an area known as Frisia and are concentrated in the Dutch provinces of Friesland an ...

with 200 ships.

Viking raids along the coast of France and the Netherlands were large-scale. Paris was besieged and the Loire Valley devastated during the 10th century. One group of Danes was granted permission to settle in northwestern France under the condition that they defend the place from future attacks. As a result, the region became known as "Normandy" and it was the descendants of these settlers who conquered England in 1066.

The oldest parts of the defensive works of Danevirke near

Hedeby

Hedeby (, Old Norse: ''Heiðabýr'', German: ''Haithabu'') was an important Danish Viking Age (8th to the 11th centuries) trading settlement near the southern end of the Jutland Peninsula, now in the Schleswig-Flensburg district of Schleswig ...

at least date from the summer of 755 and were expanded with large works in the 10th century. The size and number of troops needed to man it indicates a quite powerful ruler in the area, which might be consistent with the kings of the Frankish sources. In 815 AD, Emperor

Louis the Pious

Louis the Pious (; ; ; 16 April 778 – 20 June 840), also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and Holy Roman Emperor, co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only ...

attacked Jutland apparently in support of a contender to the throne, perhaps

Harald Klak

Harald 'Klak' Halfdansson (c. 785 – c. 852) was a king in Jutland (and possibly other parts of Denmark) around 812–814 and again from 819–827."Carolingian Chronicles: Royal Frankish Annals and Nithard's Histories" (1970), translation by Bernh ...

, but was turned back by the sons of Godfred, who most likely were the sons of the above-mentioned Godfred. At the same time

St. Ansgar

Ansgar (8 September 801 – 3 February 865), also known as Anskar, Saint Ansgar, Saint Anschar or Oscar, was Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen in the northern part of the Kingdom of the East Franks. Ansgar became known as the "Apostle of the North" ...

travelled to Hedeby and started the Catholic

Christianisation of Scandinavia.

Gorm the Old

Gorm the Old (; ; ), also called Gorm the Languid (), was List of Danish monarchs, ruler of Denmark, reigning from to his death or a few years later.Lund, N. (2020), p. 147 was the first

historical

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

ly recognized

ruler of Denmark, reigning from to his death .

He ruled from

Jelling

Jelling is a railway town in Denmark with a population of 4,038 (1 January 2025), located in Jelling Parish, approximately 10 km northwest of Vejle. The town lies 105 metres above sea level.

Location

Jelling is located in Vejle municipality ...

, and made the oldest of the

Jelling Stones

The Jelling stones () are massive carved runestones from the 10th century, found at the town of Jelling in Denmark. The older of the two Jelling stones was raised by King Gorm the Old in memory of his wife Thyra. The larger of the two stones ...

in honour of his wife

Thyra

Thyra or Thyri (Old Norse: Þyri or Þyre) was the wife of King Gorm the Old of Denmark, and one of the first queens of Denmark believed by scholars to be historical rather than legendary. She is presented in medieval sources as a wise and power ...

. Gorm was born before 900 and died . His rule marks the start of the Danish monarchy and royal house (see

Danish monarchs' family tree

This is a family tree of List of Danish monarchs, Danish monarchs from the semi-legendary king Harthacnut I of Denmark, Harthacnut I in the 10th century to the present monarch, Monarchy of Denmark, King Frederik X.

House of Gorm

...

).

The Danes were united and officially Christianized in 965 AD by Gorm's son

Harald Bluetooth

Harald "Bluetooth" Gormsson (; , died c. 985/86) was a king of Denmark and Norway.

The son of King Gorm the Old and Thyra Dannebod, Harald ruled as king of Denmark from c. 958 – c. 986, introduced Christianization of Denmark, Christianity to D ...

(see below), the story of which is recorded on the

Jelling stones

The Jelling stones () are massive carved runestones from the 10th century, found at the town of Jelling in Denmark. The older of the two Jelling stones was raised by King Gorm the Old in memory of his wife Thyra. The larger of the two stones ...

. The extent of Harald's Danish Kingdom is unknown, although it is reasonable to believe that it stretched from the defensive line of Dannevirke, including the Viking city of Hedeby, across Jutland, the Danish isles and into southern present day

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

;

Scania

Scania ( ), also known by its native name of Skåne (), is the southernmost of the historical provinces of Sweden, provinces () of Sweden. Located in the south tip of the geographical region of Götaland, the province is roughly conterminous w ...

and perhaps

Halland

Halland () is one of the traditional provinces of Sweden (''landskap''), on the western coast of Götaland, southern Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Småland, Skåne, Scania and the sea of Kattegat. Until 1645 and the Second Treaty of Br ...

and

Blekinge

Blekinge () is one of the traditional Swedish provinces (), situated in the southern coast of the geographic region of Götaland, in southern Sweden. It borders Småland, Scania and the Baltic Sea. It is the country's second-smallest provin ...

. Furthermore, the Jelling stones attest that Harald had also "won"

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

.

[Staff]

Saint Brices Day massacre

Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

. Retrieved 26 December 2007.

In retaliation for the

St. Brice's Day massacre of Danes in England, the son of Harald,

Sweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard ( ; ; 17 April 963 – 3 February 1014) was King of Denmark from 986 until his death, King of England for five weeks from December 1013 until his death, and King of Norway from 999/1000 until 1014. He was the father of King Ha ...

mounted a series of wars of conquest against England. By 1014, England had completely submitted to the Danes. However, distance and a lack of common interests prevented a lasting union, and Sweyn's son

Cnut the Great

Cnut ( ; ; – 12 November 1035), also known as Canute and with the epithet the Great, was King of England from 1016, King of Denmark from 1018, and King of Norway from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rul ...

barely maintained the link between the two countries, which completely broke up during the reign of his son

Hardecanute. A final attempt by the Norwegians under

Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' in the sagas, was List of Norwegian monarchs, King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. He unsuccessfully claimed the Monarchy of Denma ...

to reconquer England failed, but did pave the way for William the Conqueror's takeover in 1066.

Christianity, expansion and the establishment of the Kingdom of Denmark

The history of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

in Denmark overlaps with that of the Viking Age. Various petty kingdoms existed throughout the area now known as Denmark for many years. Between c. 960 and the early 980s,

Harald Bluetooth

Harald "Bluetooth" Gormsson (; , died c. 985/86) was a king of Denmark and Norway.

The son of King Gorm the Old and Thyra Dannebod, Harald ruled as king of Denmark from c. 958 – c. 986, introduced Christianization of Denmark, Christianity to D ...

appears to have established a kingdom in the lands of the Danes which stretched from Jutland to Skåne. Around the same time, he received a visit from a German

missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

who, according to legend, survived an

ordeal by fire

Trial by ordeal was an ancient judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused (called a "proband") was determined by subjecting them to a painful, or at least an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience.

In medieval Europe, like ...

, which convinced Harald to convert to

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

.

Sweyn Estridson

Sweyn II ( – 28 April 1076), also known as Sweyn Estridsson (, ) and Sweyn Ulfsson, was King of Denmark from 1047 until his death in 1076. He was the son of Ulf Thorgilsson and Estrid Svendsdatter, and the grandson of Sweyn Forkbeard through hi ...

(1020–1074) re-established strong royal Danish authority and built a good relationship with

Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are many archbishops who either have jurisdiction over an ecclesiastical province in addition to their own archdi ...

Adalbert of Hamburg

Adalbert (also Adelbert or Albert; c. 1000 – 16 March 1072) was Archbishop of Bremen from 1043 until his death. Called ''Vikar des Nordens'', he was an important political figure of the Holy Roman Empire, papal legate, and one of the regent ...

-

Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

– at that time the archbishop of all of

Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

.

The new

religion

Religion is a range of social system, social-cultural systems, including designated religious behaviour, behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, religious text, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics in religion, ethics, or ...

, which replaced the old

Norse religious practices, had many advantages for the king. Christianity brought with it some support from the

Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

. It also allowed the king to dismiss many of his opponents who adhered to the old mythology. At this early stage there is no evidence that the Danish Church was able to create a stable administration that Harald could use to exercise more effective control over his kingdom, but it may have contributed to the development of a centralising political and religious ideology among the social elite which sustained and enhanced an increasingly powerful kingship.

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

broke away from Danish control in 1035 and Denmark fell into disarray for some time. Sweyn Estridsen's son,

Canute IV

Canute IV ( – 10 July 1086), later known as Canute the Holy () or Saint Canute (''Sankt Knud''), was King of Denmark from 1080 until 1086. Canute was an ambitious king who sought to strengthen the Danish monarchy, devotedly supported the ...

, raided England for the last time in 1085. He planned another invasion to take the

throne of England

The Throne of England is the throne of the Monarch of England. "Throne of England" also refers metonymically to the office of monarch, and monarchy itself.Gordon, Delahay. (1760) ''A General History of the Lives, Trials, and Executions of All t ...

from an aging

William I William I may refer to:

Kings

* William the Conqueror (–1087), also known as William I, King of England

* William I of Sicily (died 1166)

* William I of Scotland (died 1214), known as William the Lion

* William I of the Netherlands and Luxembour ...

. He called up a fleet of 1,000 Danish ships, 60 Norwegian

long boats

A longboat is a type of ship's boat that was in use from ''circa'' 1500 or before. Though the Royal Navy replaced longboats with launches from 1780, examples can be found in merchant ships after that date. The longboat was usually the largest boa ...

, with plans to meet with another 600 ships under

Duke Robert of Flanders in the summer of 1086. Canute, however, was beginning to realise that the imposition of the tithe on Danish peasants and nobles to fund the expansion of monasteries and churches and a new

head tax

A poll tax, also known as head tax or capitation, is a tax levied as a fixed sum on every liable individual (typically every adult), without reference to income or resources. ''Poll'' is an archaic term for "head" or "top of the head". The sen ...

() had brought his people to the verge of rebellion. Canute took weeks to arrive where the fleet had assembled at Struer, but he found only the

Norwegians

Norwegians () are an ethnic group and nation native to Norway, where they form the vast majority of the population. They share a common culture and speak the Norwegian language. Norwegians are descended from the Norsemen, Norse of the Early ...

still there.

Canute thanked the Norwegians for their patience and then went from assembly to assembly () outlawing any sailor, captain or soldier who refused to pay a fine, which amounted to more than a year's harvest for most farmers. Canute and his

housecarl

A housecarl (; ) was a non- servile manservant or household bodyguard in medieval Northern Europe.

The institution originated amongst the Norsemen of Scandinavia, and was brought to Anglo-Saxon England by the Danish conquest in the 11th centur ...

s fled south with a growing army of rebels on his heels. Canute fled to the royal property outside the town of Odense on Funen with his two brothers. After several attempts to break in and then bloody hand-to-hand fighting in the church, Benedict was cut down, and Canute was struck in the head by a large stone and then speared from the front. He died at the base of the main altar on 10 July 1086, where he was buried by the Benedictines. When Queen Edele came to take Canute's body to Flanders, a light allegedly shone around the church and it was taken as a sign that Canute should remain where he was.

The death of St. Canute marks the end of the Viking Age. Never again would massive flotillas of

Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

ns meet each year to ravage the rest of Christian Europe.

In the early 12th century, Denmark became the seat of an independent

church province

An ecclesiastical province is one of the basic forms of jurisdiction in Christian churches, including those of both Western Christianity and Eastern Christianity, that have traditional hierarchical structures. An ecclesiastical province consists ...

of Scandinavia. Not long after that,

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and

Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the archipelago of Svalbard also form part of the Kingdom of ...

established their own archbishoprics, free of Danish control. The mid-12th century proved a difficult time for the kingdom of Denmark. Violent

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

s rocked the land. Eventually,

Valdemar the Great (1131–82), gained control of the kingdom, stabilizing it and reorganizing the administration. King Valdemar and

Absalon

Absalon (21 March 1201) was a Danish statesman and prelate of the Catholic Church who served as the bishop of Roskilde from 1158 to 1192 and archbishop of Lund from 1178 until his death. He was the foremost politician and church father of De ...

(''ca'' 1128–1201), the

bishop of Roskilde

The former Diocese of Roskilde () was a diocese within the Roman-Catholic Church which was established in Denmark some time before 1022. The diocese was dissolved with the Reformation of Denmark and replaced by the Protestant Diocese of Zealand ...

, rebuilt the country.

During Valdemar's reign construction began of a castle in the village of Havn, leading eventually to the foundation of

Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

, the modern capital of Denmark. Valdemar and Absalon built Denmark into a major power in the

Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

, a power which later competed with the

Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

, the counts of

Holstein

Holstein (; ; ; ; ) is the region between the rivers Elbe and Eider (river), Eider. It is the southern half of Schleswig-Holstein, the northernmost States of Germany, state of Germany.

Holstein once existed as the German County of Holstein (; 8 ...

, and the

Teutonic Knights

The Teutonic Order is a Catholic religious institution founded as a military society in Acre, Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Order of Brothers of the German House of Saint Mary in Jerusalem was formed to aid Christians on their pilgrimages to t ...

for trade, territory, and influence throughout the Baltic. In 1168, Valdemar and Absalon gained a foothold on the southern shore of the Baltic, when they subdued the

Principality of Rügen

The Principality of Rügen was a Medieval Denmark, Danish principality, formerly a duchy, consisting of the island of Rügen and the adjacent mainland from 1168 until 1325. It was governed by a local dynasty of princes of the ''Wizlawiden'' (''Hou ...

.

In the 1180s,

Mecklenburg

Mecklenburg (; ) is a historical region in northern Germany comprising the western and larger part of the federal-state Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. The largest cities of the region are Rostock, Schwerin, Neubrandenburg, Wismar and Güstrow. ...

and the

Duchy of Pomerania

The Duchy of Pomerania (; ; Latin: ''Ducatus Pomeraniae'') was a duchy in Pomerania on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, ruled by dukes of the House of Pomerania (''Griffins''). The country existed in the Middle Ages between years 1121–11 ...

came under Danish control, too. In the new southern provinces, the Danes promoted Christianity (mission of the

Rani

''Rani'' () is a female title, equivalent to queen, for royal or princely rulers in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia. It translates to 'queen' in English. It is also a Sanskrit Hindu feminine given name. The term applies equally to a ...

, monasteries like

Eldena Abbey

Eldena Abbey (), originally Hilda Abbey () is a former Cistercian monastery near the present town of Greifswald in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Germany. Only ruins survive, which are well known as a frequent subject of Caspar David Friedrich's paintin ...

) and settlement (Danish participation in the ''

Ostsiedlung

(, ) is the term for the Early Middle Ages, early medieval and High Middle Ages, high medieval migration of Germanic peoples and Germanisation of the areas populated by Slavs, Slavic, Balts, Baltic and Uralic languages, Uralic peoples; the ...

''). The Danes lost most of their southern gains after the

Battle of Bornhöved (1227)

The (second) Battle of Bornhöved took place on 22 July 1227 near Bornhöved in Holstein. Count Adolf IV of Schauenburg and Holstein — leading an army consisting of troops from the cities of Lübeck and Hamburg, Dithmarschen, Holstein, a ...

, but the Rugian principality stayed with Denmark until 1325.

In 1202,

Valdemar II

Valdemar II Valdemarsen (28 June 1170 – 28 March 1241), later remembered as Valdemar the Victorious () and Valdemar the Conqueror, was King of Denmark from 1202 until his death in 1241.

In 1207, Valdemar invaded and conquered Lybeck and Hol ...

became king and launched various "

crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

" to claim territories, notably modern

Estonia

Estonia, officially the Republic of Estonia, is a country in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the Baltic Sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, and to the east by Ru ...

. Once these efforts were successful, a period in history known as the Danish Estonia began. Legend has it that the Danish flag, the Flag of Denmark, Dannebrog fell from the sky during the Battle of Lyndanisse, Battle of Lindanise in Estonia in 1219. A series of Danish defeats culminating in the Battle of Bornhöved on 22 July 1227 cemented the loss of Denmark's north German territories. Valdemar himself was saved only by the courageous actions of a German knight who carried Valdemar to safety on his horse.

From that time on, Valdemar focused his efforts on domestic affairs. One of the changes he instituted was the feudal system where he gave properties to men with the understanding that they owed him service. This increased the power of the noble families () and gave rise to the lesser nobles () who controlled most of Denmark. Free peasants lost the traditional rights and privileges they had enjoyed since Viking times.

The king of Denmark had difficulty maintaining control of the kingdom in the face of opposition from the nobility and from the Church. An extended period of strained relations between the crown and the Popes of Rome took place, known as the "archiepiscopal conflicts".

By the late 13th century, royal power had waned, and the nobility forced the king to grant a charter, considered Denmark's first constitution. Following the Battle of Bornhöved (1227), Battle of Bornhöved in 1227, a weakened Denmark provided windows of opportunity to both the Hanseatic League and the count of Holstein, Counts of Holstein. The Holstein Counts gained control of large portions of Denmark because the king would grant them fiefs in exchange for money to finance royal operations.

Valdemar spent the remainder of his life putting together a code of laws for Jutland, Zealand and Skåne. These codes were used as Denmark's legal code until 1683. This was a significant change from the local law making at the regional assemblies (), which had been the long-standing tradition. Several methods of determining guilt or innocence were outlawed including trial by ordeal and trial by combat. The Code of Jutland () was approved at meeting of the nobility at Vordingborg in 1241 just prior to Valdemar's death. Because of his position as "the king of Dannebrog" and as a legislator, Valdemar enjoys a central position in Danish history. To posterity the civil wars and dissolution that followed his death made him appear to be the last king of a golden age.

The Middle Ages saw a period of close cooperation between the The Crown, Crown and the Roman Catholic Church. Thousands of church buildings sprang up throughout the country during this time. The economy expanded during the 12th century, based mostly on the lucrative herring-trade, but the 13th century turned into a period of difficulty and saw the temporary collapse of royal authority.

Count rule

During the disastrous reign of Christopher II of Denmark, Christopher II (1319–1332), most of the country was seized by the provincial counts (except Skåne, which was taken over by Sweden) after numerous peasant revolts and conflicts with the Church. For eight years after Christopher's death, Denmark had no king, and was instead controlled by the counts. After one of them, Gerhard III of Holstein-Rendsburg, was assassinated in 1340, Christopher's son Valdemar IV of Denmark, Valdemar was chosen as king, and gradually began to recover the territories, which was finally completed in 1360.

The Black Death in Denmark, which came to Denmark during these years, also aided Valdemar's campaign. His continued efforts to expand the kingdom after 1360 brought him into open conflict with the Hanseatic League. He conquered Gotland, much to the displeasure of the League, which lost Visby, an important trading town located there.

The Hanseatic alliance with Sweden to attack Denmark initially proved a fiasco since Danish forces captured a large Hanseatic fleet, and ransomed it back for an enormous sum. Luckily for the League, the Jutland nobles revolted against the heavy taxes levied to fight the expansionist war in the Baltic; the two forces worked against the king, forcing him into exile in 1370. For several years, the Hanseatic League controlled the fortresses on Öresund, the Sound, the strait between Skåne and Zealand.

Margaret and the Kalmar Union (1397–1523)

Margaret I of Denmark, Margaret I, the daughter of Valdemar Atterdag, found herself married off to Haakon VI of Norway, Håkon VI of Norway in an attempt to join the two kingdoms, along with Sweden, since Håkon had kinship ties to the Swedish royal family. The dynastic plans called for her son, Olaf IV of Norway, Olaf II to rule the three kingdoms, but after his early death in 1387 she took on the role herself (1387–1412). During her lifetime (1353–1412) the three kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (including the

Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ) (alt. the Faroes) are an archipelago in the North Atlantic Ocean and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. Located between Iceland, Norway, and the United Kingdom, the islands have a populat ...

, as well as

Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

,

Greenland

Greenland is an autonomous territory in the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark. It is by far the largest geographically of three constituent parts of the kingdom; the other two are metropolitan Denmark and the Faroe Islands. Citizens of Greenlan ...

, and present-day Finland) became linked under her capable rule, in what became known as the Kalmar Union, made official in 1397.

Her successor, Eric VII of Denmark, Eric of Pomerania (King of Denmark from 1412 to 1439), lacked Margaret's skill and thus directly caused the breakup of the Kalmar Union. Eric's foreign policy engulfed Denmark in a succession of wars with the Holstein counts and the city of Lübeck. When the Hanseatic League imposed a trade embargo on Scandinavia, the Swedes (who saw their mining industry adversely affected) rose up in revolt. The three countries of the Kalmar Union all declared Eric deposed in 1439.

However, support for the idea of regionalism continued, so when Eric's nephew Christopher of Bavaria came to the throne in 1440, he managed to get himself elected in all three kingdoms, briefly reuniting Scandinavia (1442–1448). The Swedish nobility grew increasingly unhappy with Danish rule and the union soon became merely a legal concept with little practical application. During the subsequent reigns of Christian I (1450–1481) and Hans (1481–1513), tensions grew, and several wars between Sweden and Denmark erupted.

In the early 16th century, Christian II of Denmark, Christian II (reigned 1513–1523) came to power. He allegedly declared, "If the hat on my head knew what I was thinking, I would pull it off and throw it away." This quotation apparently refers to his devious and Niccolò Machiavelli, machiavellian political dealings. He conquered Sweden in an attempt to reinforce the union, and had about 100 leaders of the Swedish anti-unionist forces killed in what came to be known as the Stockholm Bloodbath of November 1520. The bloodbath destroyed any lingering hope of Scandinavian union.

In the aftermath of

Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

's definitive secession from the Kalmar Union in 1521,

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...