Maniots on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Maniots () or Maniates () are an ethnic

Centre for Research of Greek Folklore of the Academy of Athens (in Greek)

2.581

Under the Mycenaeans, Mani flourished and a temple dedicated to the Greek god

While the

While the

During the

During the

34.29

. The allies went on to besiege Sparta and tried to force Nabis to surrender. As part of the terms of the peace treaty, the coastal cities of Mani were forced to become autonomous. The cities formed the Koinon of Free Laconians with Gythium as the capital under the Achaean League's protection. Nabis, not content with losing his land in Mani, built a fleet and strengthened his army and advanced upon Gythium in 192 BC.

Nabis

. The Achaean League's army and navy under Philopoemen, tried to relieve the city but the Achaean navy was defeated off Gythium and the army was forced to retreat to

35.35

. However, the Spartans, while searching for a port captured Las. The Achaeans responded by seizing Sparta and unsuccessfully forcing their laws on it..

On January 17, 395,

On January 17, 395,

There is a description of Mani and its inhabitants in

There is a description of Mani and its inhabitants in

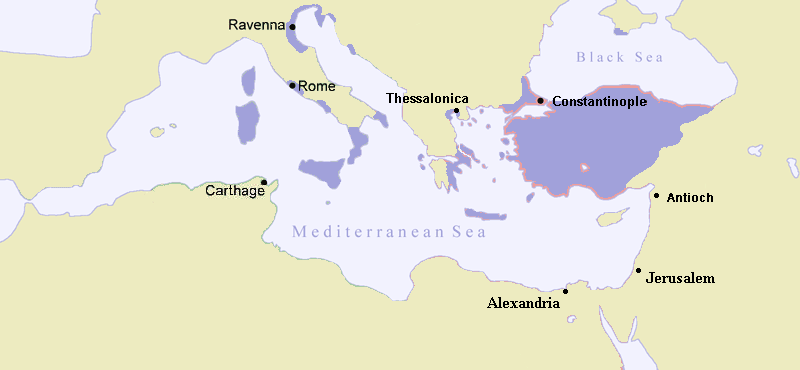

On July 25, 1261, the Byzantines under

On July 25, 1261, the Byzantines under

Krokodeilos Kladas, a Greek from Laconia, was granted lordship by Mehmed over

Krokodeilos Kladas, a Greek from Laconia, was granted lordship by Mehmed over

In 1603, the Maniots approached

In 1603, the Maniots approached

From Kastania, Hasan Ghazi advanced towards Skoutari and laid siege to the tower of the powerful Grigorakis clan. The tower contained fifteen men, who held out for three days until the Turks undermined the tower, placed gunpowder, and blew up the entire garrison. By this time, the main Maniot army of 5,000 men and 2,000 women had established a defensive position which was on mountainous terrain above the town of Parasyros. The entire army was under the command of Exarchos Grigorakis and his nephew Zanetos Grigorakis. The Ottoman army advanced to the plain of Agio Pigada (meaning "Holy Well"). They sent envoys to the Maniots telling them that Hasan wanted to negotiate. The Maniots knew that if they sent envoys to the Turks, they would be executed by Hasan if the negotiations failed. However, the Maniots sent six men to discuss the terms.

Six Maniot envoys were sent to Hasan and, without bowing, asked him what he wanted. Hasan's demands entailed the children of ten captains as hostages, all Maniot-held arms, and an annual head-tax to be paid as punishment for supporting the Russians. The Maniots answered Hasan's demands saying, "We prefer to die rather than give to you our guns and children. We don't pay taxes, because our land is poor." Hasan became furious and had the six men decapitated and impaled on stakes so that the Maniots could see them..

After the envoys were killed, the remaining Maniots attacked the Ottomans. The fighting was fierce, and only 6,000 Turks managed to reach

From Kastania, Hasan Ghazi advanced towards Skoutari and laid siege to the tower of the powerful Grigorakis clan. The tower contained fifteen men, who held out for three days until the Turks undermined the tower, placed gunpowder, and blew up the entire garrison. By this time, the main Maniot army of 5,000 men and 2,000 women had established a defensive position which was on mountainous terrain above the town of Parasyros. The entire army was under the command of Exarchos Grigorakis and his nephew Zanetos Grigorakis. The Ottoman army advanced to the plain of Agio Pigada (meaning "Holy Well"). They sent envoys to the Maniots telling them that Hasan wanted to negotiate. The Maniots knew that if they sent envoys to the Turks, they would be executed by Hasan if the negotiations failed. However, the Maniots sent six men to discuss the terms.

Six Maniot envoys were sent to Hasan and, without bowing, asked him what he wanted. Hasan's demands entailed the children of ten captains as hostages, all Maniot-held arms, and an annual head-tax to be paid as punishment for supporting the Russians. The Maniots answered Hasan's demands saying, "We prefer to die rather than give to you our guns and children. We don't pay taxes, because our land is poor." Hasan became furious and had the six men decapitated and impaled on stakes so that the Maniots could see them..

After the envoys were killed, the remaining Maniots attacked the Ottomans. The fighting was fierce, and only 6,000 Turks managed to reach

During Zanetos' rule, Mani became a base for many klephts and other Greek bandits. Among them was the famous Greek pirate and officer of the Russian army, Lambros Katsonis, who helped the Russians with their wars against the Ottomans, Andreas Androutsos (father of Odysseas), and Zacharias Barbitsiotis.. On January 9, 1792,

During Zanetos' rule, Mani became a base for many klephts and other Greek bandits. Among them was the famous Greek pirate and officer of the Russian army, Lambros Katsonis, who helped the Russians with their wars against the Ottomans, Andreas Androutsos (father of Odysseas), and Zacharias Barbitsiotis.. On January 9, 1792,

In 1805, Seremet attacked Zacharias Barbitsiotis at his fortress in the

In 1805, Seremet attacked Zacharias Barbitsiotis at his fortress in the

On March 21, an army of 2,000 Maniots under the command of Petros Mavromichalis,

On March 21, an army of 2,000 Maniots under the command of Petros Mavromichalis,  Ibrahim made good use of this turmoil and landed with his army (25-30,000 infantry, cavalry and artillery supported by the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet) at Methoni. Ibrahim soon had recaptured the Peloponnese except for

Ibrahim made good use of this turmoil and landed with his army (25-30,000 infantry, cavalry and artillery supported by the Ottoman-Egyptian fleet) at Methoni. Ibrahim soon had recaptured the Peloponnese except for

At the start of the 20th century, Greece was involved with the Macedonian Struggle, military conflicts against the Bulgarian organization known as the

At the start of the 20th century, Greece was involved with the Macedonian Struggle, military conflicts against the Bulgarian organization known as the

The Maniot dialect of Modern Greek has several archaic properties that distinguishes it from most mainstream varieties. One of them, shared with the highly divergent Tsakonian as well as with the old dialects spoken around Athens until the 19th century, is the divergent treatment of historical (written <υ>). Although this sound merged to everywhere else, these dialects have instead (e.g. versus standard 'wood').. These varieties are thought to be relic areas of a previously larger areal dialect group that used to share these features and was later divided by the penetration of

The Maniot dialect of Modern Greek has several archaic properties that distinguishes it from most mainstream varieties. One of them, shared with the highly divergent Tsakonian as well as with the old dialects spoken around Athens until the 19th century, is the divergent treatment of historical (written <υ>). Although this sound merged to everywhere else, these dialects have instead (e.g. versus standard 'wood').. These varieties are thought to be relic areas of a previously larger areal dialect group that used to share these features and was later divided by the penetration of

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

subgroup that traditionally inhabit the Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula (), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (), is a geographical and cultural region in the Peloponnese of Southern Greece and home to the Maniots (), who claim descent from the ancient Spartans. The capital ci ...

; located in western Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia (, , ) is a historical and Administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparti (municipality), Sparta. The word ...

and eastern Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

, in the southern Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. They were also formerly known as Mainotes, and the peninsula as ''Maina''.

The Maniots claim to be the descendants of the ancient Spartans

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the valley of Evrotas river in Laconia, in southeastern P ...

and they have often been described as such. The terrain is mountainous and inaccessible (until recently many Mani villages could be accessed only by sea), and the regional name "Mani" is thought to have meant originally "dry" or "barren". The name "Maniot" is a derivative meaning "of Mani". In the early modern period

The early modern period is a Periodization, historical period that is defined either as part of or as immediately preceding the modern period, with divisions based primarily on the history of Europe and the broader concept of modernity. There i ...

, Maniots had a reputation as fierce and proudly independent warrior

A warrior is a guardian specializing in combat or warfare, especially within the context of a tribal society, tribal or clan-based warrior culture society that recognizes a separate warrior aristocracy, social class, class, or caste.

History

...

s, who practiced piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

and fierce blood feuds. For the most part, the Maniots lived in fortified villages (and "house-towers") where they defended their lands against the armies of William II Villehardouin and later against those of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

.

Names

The surnames of the Maniots uniformly end in "eas" in what is now theMessenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

n ("outer" or northwestern) part of Mani, "akis" or "-akos" in what is now the Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia (, , ) is a historical and Administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparti (municipality), Sparta. The word ...

n ("inner" or southwestern and eastern) part of Mani and the occasional "-oggonas".Form and evolution of Maniot surnamesCentre for Research of Greek Folklore of the Academy of Athens (in Greek)

Ancient Mani

Mycenaean Mani

Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's "Catalogue of Ships

The Catalogue of Ships (, ''neōn katálogos'') is an epic catalogue in Book 2 of Homer's ''Iliad'' (2.494–759), which lists the contingents of the Achaean army that sailed to Troy. The catalogue gives the names of the leaders of each conting ...

" in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'' mentions the cities of Mani: Messi (Mezapos), Oetylus (Oitylo), Kardamili (or Skardamoula), Gerenia, Teuthrone (Kotronas), and Las ( Passavas).Homer. ''The Iliad''2.581

Under the Mycenaeans, Mani flourished and a temple dedicated to the Greek god

Apollo

Apollo is one of the Twelve Olympians, Olympian deities in Ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek and Ancient Roman religion, Roman religion and Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology. Apollo has been recognized as a god of archery, mu ...

was built at Cape Tenaron. The temple was of such importance that it rivaled Delphi

Delphi (; ), in legend previously called Pytho (Πυθώ), was an ancient sacred precinct and the seat of Pythia, the major oracle who was consulted about important decisions throughout the ancient Classical antiquity, classical world. The A ...

which was then a temple dedicated to Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

. Eventually, the temple of Tenaron was dedicated to Poseidon and the temple at Delphi was dedicated to Apollo. According to other legends, there is a cave near Tenaro that leads to Hades

Hades (; , , later ), in the ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, is the god of the dead and the king of the Greek underworld, underworld, with which his name became synonymous. Hades was the eldest son of Cronus and Rhea ...

. Mani was also featured in other tales such as when Helen of Troy

Helen (), also known as Helen of Troy, or Helen of Sparta, and in Latin as Helena, was a figure in Greek mythology said to have been the most beautiful woman in the world. She was believed to have been the daughter of Zeus and Leda (mythology), ...

(Queen of Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

), and Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

spent their first night together on the island of Cranae, off the coast of Gytheio..

During the 12th century BC, the Dorians

The Dorians (; , , singular , ) were one of the four major ethnic groups into which the Greeks, Hellenes (or Greeks) of Classical Greece divided themselves (along with the Aeolians, Achaeans (tribe), Achaeans, and Ionians). They are almost alw ...

invaded Laconia

Laconia or Lakonia (, , ) is a historical and Administrative regions of Greece, administrative region of Greece located on the southeastern part of the Peloponnese peninsula. Its administrative capital is Sparti (municipality), Sparta. The word ...

. The Dorians settled originally at Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

, but they soon started to expand their territory and by around 800 BC they had occupied Mani and the rest of Laconia. Mani was given the social caste of Perioeci

The Perioeci or Perioikoi (, ) were the second-tier citizens of the ''polis'' of Sparta until 200 BC. They lived in several dozen cities within Spartan territories (mostly Laconia and Messenia), which were dependent on Sparta. The ''perioeci'' ...

.. During that time, the Phoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

came to Mani and were thought to have established a colony at Gythion (Roman name: Gythium). This colony collected murex

''Murex'' is a genus of medium to large sized predatory tropical sea snails. These are carnivorous marine gastropod molluscs in the family Muricidae, commonly called "murexes" or "rock snails".Houart, R.; Gofas, S. (2010). Murex Linnaeus, 1 ...

, a sea shell that was used to make purple dye and was plentiful in the Laconian Gulf

The Laconian Gulf (), is a gulf in the south-eastern Peloponnese, in Greece. It is the southernmost gulf in Greece and the largest in the Peloponnese.

In the shape of an inverted "U", it is approximately wide east to west, and long north to so ...

..

Classical Mani

While the

While the Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

ns ruled Mani, Tenaron became an important gathering place for mercenaries.. Gythium became a major port under the Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

ns as it was only away from Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

. In 455 BC, during the First Peloponnesian War

The First Peloponnesian War (460–445 BC) was fought between Sparta as the leaders of the Peloponnesian League and Sparta's other allies, most notably Thebes, and the Delian League led by Athens with support from Argos. This war consisted o ...

, it was besieged and captured by the Athenian admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in many navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force. Admiral is ranked above vice admiral and below admiral of ...

Tolmides along with 50 triremes and 4,000 hoplites. The city and the dockyards were rebuilt and by the late Peloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

, Gythium was the main building place for the new Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

n fleet. The Spartan leadership of the Peloponnese lasted until 371 BC, when the Thebans

Thebes ( ; , ''Thíva'' ; , ''Thêbai'' .) is a city in Boeotia, Central Greece, and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world. It is the largest city in Boeotia and a major center for the area along with Livadeia and ...

under Epaminondas

Epaminondas (; ; 419/411–362 BC) was a Greeks, Greek general and statesman of the 4th century BC who transformed the Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek polis, city-state of Thebes, Greece, Thebes, leading it out of Spartan subjugation into a pre ...

defeated them at Leuctra. The Thebans began a campaign against Laconia and captured Gythium after a three-day siege. The Thebans only briefly managed to hold Gythium, which was captured by 100 elite warriors posing as athletes.

Hellenistic Mani

During the

During the Hellenistic period

In classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Greek history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the death of Cleopatra VII in 30 BC, which was followed by the ascendancy of the R ...

of Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Mani remained controlled by the Spartans. The Macedonians under the command of Philip V of Macedon

Philip V (; 238–179 BC) was king of the Ancient Greece, ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia (ancient kingdom), Macedon from 221 to 179 BC. Philip's reign was principally marked by the Social War (220–217 BC), Social War in Greece (220-217 BC) ...

tried to invade Mani and the rest of Laconia (219–218 BC) and unsuccessfully besieged the cities of Gythium, Las and Asine. When Nabis Nabis may refer to:

* Nabis of Sparta, reigned 207–192 BCE

* Nabis (art), a Parisian post-Impressionist artistic group

* ''Nabis'' (bug), a genus of insects

* NABIS, National Ballistics Intelligence Service, a British government agency

See a ...

took over the Spartan throne in 207 BC, he implemented some democratic reforms. One of these reforms entailed making Gythium into a major port and naval arsenal.. In 195 BC, during the Roman–Spartan War, the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and the Achaean League

The Achaean League () was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era confederation of polis, Greek city-states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea (ancient region), Achaea in the northwestern Pelopon ...

with assistance from a combined Pergamene and Rhodian force captured Gythium after a lengthy siege.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

. ''Ab urbe condita libri

The ''History of Rome'', perhaps originally titled , and frequently referred to as (), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by the Roman historian Titus Livius, better known in English as "Livy". ...

''34.29

. The allies went on to besiege Sparta and tried to force Nabis to surrender. As part of the terms of the peace treaty, the coastal cities of Mani were forced to become autonomous. The cities formed the Koinon of Free Laconians with Gythium as the capital under the Achaean League's protection. Nabis, not content with losing his land in Mani, built a fleet and strengthened his army and advanced upon Gythium in 192 BC.

Nabis

. The Achaean League's army and navy under Philopoemen, tried to relieve the city but the Achaean navy was defeated off Gythium and the army was forced to retreat to

Tegea

Tegea (; ) was a settlement in ancient Arcadia, and it is also a former municipality in Arcadia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the Tripoli municipality, of which it is a municipal unit with an area o ...

. A Roman fleet under Atilius managed to re-capture Gythium later that year. Nabis was murdered later that year and Sparta was made part of the Achaean League.Livy

Titus Livius (; 59 BC – AD 17), known in English as Livy ( ), was a Roman historian. He wrote a monumental history of Rome and the Roman people, titled , covering the period from the earliest legends of Rome before the traditional founding i ...

. ''Ab urbe condita libri

The ''History of Rome'', perhaps originally titled , and frequently referred to as (), is a monumental history of ancient Rome, written in Latin between 27 and 9 BC by the Roman historian Titus Livius, better known in English as "Livy". ...

''35.35

. However, the Spartans, while searching for a port captured Las. The Achaeans responded by seizing Sparta and unsuccessfully forcing their laws on it..

Roman Mani

The Maniots lived in peace until 146 BC when theAchaean League

The Achaean League () was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era confederation of polis, Greek city-states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea (ancient region), Achaea in the northwestern Pelopon ...

rebelled against Roman dominance, resulting in the Battle of Corinth. The conflict resulted in the destruction of Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

by the forces of Lucius Mummius Achaicus

Lucius Mummius (2nd century BC) was a Roman Republic, Roman statesman and general. He was consul in the year 146 BC along with Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus (consul 146 BC), Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus.

Mummius was the first of his family to rise to ...

and the annexation of the Achaean League

The Achaean League () was a Hellenistic period, Hellenistic-era confederation of polis, Greek city-states on the northern and central Peloponnese. The league was named after the region of Achaea (ancient region), Achaea in the northwestern Pelopon ...

by the Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

. Even though the Romans conquered the Peloponnese, the Koinon was allowed to retain its independence. The Maniots suffered from pirate raids by Cretans and Cilicia

Cilicia () is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilician plain (). The region inclu ...

ns who plundered Mani and pillaged the temple of Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

. The Maniots were delivered from the pirates when Pompey the Great defeated them. Most probably in gratitude, the Maniots supplied Pompey with archers in his battles against Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

during Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

(49–45 BC) and were defeated..

During the Civil war between Antony and Octavian (32–30 BC), the Maniots and the rest of the Laconians supplied Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

with troops for his confrontation with Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman people, Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the Crisis of the Roman Republic, transformation of the Roman Republic ...

and Cleopatra VII of Egypt at the Battle of Actium

The Battle of Actium was a naval battle fought between Octavian's maritime fleet, led by Marcus Agrippa, and the combined fleets of both Mark Antony and Cleopatra. The battle took place on 2 September 31 BC in the Ionian Sea, near the former R ...

(September 2, 31 BC) and in gratitude they officially recognized Augustus as Emperor and invited him at Psamathous (near modern Porto Kagio), and their Koinon stayed an independent state. This signified the beginning of the "Golden Age" of the Koinon..

Mani flourished under the Romans, because of its respectful obedience to Rome. The Koinon consisted of 24 cities (later 18), of which Gythium remained the most prominent. However, many parts of Mani remained under the also semi-independent (autonomous under Roman sovereignty) Sparta, the most notable being Asine and Kardamyli. Mani became a center for purple dye, which was popular in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, as well as being well known for its rose antique marble and porphyry. Las is recorded to have been a comfortable city with Roman baths and a gymnasium..

Pausanias has left us a description of Gythium as it existed during the reign of Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

(reigned 161–180). The agora, the Acropolis, the island of Cranae (Marathonisi) where Paris on his way to Troy celebrated his nuptials with Beautiful Helen after taking her from Sparta, the Migonium or precinct of Aphrodite

Aphrodite (, ) is an Greek mythology, ancient Greek goddess associated with love, lust, beauty, pleasure, passion, procreation, and as her syncretism, syncretised Roman counterpart , desire, Sexual intercourse, sex, fertility, prosperity, and ...

Migonitis (occupied by the modern town), and the hill Larysium (Koumaro) rising above it. Nowadays, the most noteworthy remains of the theatre and the buildings partially submerged by the sea all belong to the Roman period.

The Koinon remained semi-independent (autonomous under Roman sovereignty) until the provincial reforms of Roman Emperor Diocletian

Diocletian ( ; ; ; 242/245 – 311/312), nicknamed Jovius, was Roman emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305. He was born Diocles to a family of low status in the Roman province of Dalmatia (Roman province), Dalmatia. As with other Illyri ...

in 297. With the barbarian invasion affecting the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, Mani became a haven for refugees. In 375, a massive earthquake in the area took its toll on Gythium, which was severely devastated. Most of the ruins of ancient Gythium are now submerged in the Laconian Gulf.

Medieval Mani

From Theodosius I to the Avar invasion

Theodosius I

Theodosius I ( ; 11 January 347 – 17 January 395), also known as Theodosius the Great, was Roman emperor from 379 to 395. He won two civil wars and was instrumental in establishing the Nicene Creed as the orthodox doctrine for Nicene C ...

, who had managed to unite the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

under his control, died. His eldest son, Arcadius

Arcadius ( ; 377 – 1 May 408) was Roman emperor from 383 to his death in 408. He was the eldest son of the ''Augustus'' Theodosius I () and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla, and the brother of Honorius (). Arcadius ruled the eastern half of ...

, succeeded him in the Eastern Roman Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived the events that caused the fall of the Western Roman E ...

, while his younger son, Honorius

Honorius (; 9 September 384 – 15 August 423) was Roman emperor from 393 to 423. He was the younger son of emperor Theodosius I and his first wife Aelia Flaccilla. After the death of Theodosius in 395, Honorius, under the regency of Stilicho ...

, received the Western Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

. The Roman Empire had divided for the last time, and Mani became part of the Eastern or Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

. Between 395 and 397, Alaric I

Alaric I (; , 'ruler of all'; ; – 411 AD) was the first Germanic kingship, king of the Visigoths, from 395 to 410. He rose to leadership of the Goths who came to occupy Moesia—territory acquired a couple of decades earlier by a combine ...

and his Visigoths

The Visigoths (; ) were a Germanic people united under the rule of a king and living within the Roman Empire during late antiquity. The Visigoths first appeared in the Balkans, as a Roman-allied Barbarian kingdoms, barbarian military group unite ...

plundered the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

and destroyed what was left of Gythium. Alaric captured the most famous cities, Corinth

Corinth ( ; , ) is a municipality in Corinthia in Greece. The successor to the ancient Corinth, ancient city of Corinth, it is a former municipality in Corinthia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, which is located in south-central Greece. Sin ...

, Argos, and Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

. He was at last defeated by Stilicho

Stilicho (; – 22 August 408) was a military commander in the Roman army who, for a time, became the most powerful man in the Western Roman Empire. He was partly of Vandal origins and married to Serena, the niece of emperor Theodosius I. He b ...

and then crossed the Gulf of Corinth

The Gulf of Corinth or the Corinthian Gulf (, ) is a deep inlet of the Ionian Sea, separating the Peloponnese from western mainland Greece. It is bounded in the east by the Isthmus of Corinth which includes the shipping-designed Corinth Canal and ...

towards the north.

In 468, Gaiseric

Gaiseric ( – 25 January 477), also known as Geiseric or Genseric (; reconstructed Vandalic: ) was king of the Vandals and Alans from 428 to 477. He ruled over a kingdom and played a key role in the decline of the Western Roman Empire during ...

of the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who were first reported in the written records as inhabitants of what is now Poland, during the period of the Roman Empire. Much later, in the fifth century, a group of Vandals led by kings established Vand ...

attempted to conquer Mani with the purpose of using it as a base to raid and then conquer the Peloponnese. Gaiseric tried to land his fleet at Kenipolis (near modern village of Kyparissos in Cape Tenaron), but as his army disembarked, the inhabitants of the town attacked the Vandals and made them retreat after heavy casualties..

Decades later, the famed Byzantine general Belisarius

BelisariusSometimes called Flavia gens#Later use, Flavius Belisarius. The name became a courtesy title by the late 4th century, see (; ; The exact date of his birth is unknown. March 565) was a military commander of the Byzantine Empire under ...

, on the way to his victorious campaign against the Vandals, stopped at Kenipolis to get supplies, honor the Kenipolitans for their victory, and recruit some soldiers.. According to Greenhalgh and Eliopoulos, the Eurasian Avars (along with the Slavs

The Slavs or Slavic people are groups of people who speak Slavic languages. Slavs are geographically distributed throughout the northern parts of Eurasia; they predominantly inhabit Central Europe, Eastern Europe, Southeastern Europe, and ...

) attacked and occupied most of the western Peloponnese in 590.. However, there is no archaeological evidence for a Slavic (or Avar) penetration of imperial Byzantine territory before the end of the 6th century. Overall, traces of Slavic culture in Greece are very rare.

During the Macedonian dynasty

Constantine VII

Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (; 17 May 905 – 9 November 959) was the fourth Byzantine emperor of the Macedonian dynasty, reigning from 6 June 913 to 9 November 959. He was the son of Emperor Leo VI and his fourth wife, Zoe Karbonopsina, an ...

's ''De Administrando Imperio

(; ) is a Greek-language work written by the 10th-century Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII. It is a domestic and foreign policy manual for the use of Constantine's son and successor, the Emperor Romanos II. It is a prominent example of Byz ...

'':

The area inhabited by the Maniates (or Maniots) was first called by the name 'Maina' and was associated probably with the castle of Tigani (situated in the small peninsula of Tigani in Mezapos bay in northwestern Mani Peninsula

The Mani Peninsula (), also long known by its medieval name Maina or Maïna (), is a geographical and cultural region in the Peloponnese of Southern Greece and home to the Maniots (), who claim descent from the ancient Spartans. The capital ci ...

). The Maniots at that time were called 'Hellenes'—that is, pagans (see Names of the Greeks

The Greeks () have been identified by many ethnonyms. The most common native ethnonym is ''Hellene'' (), pl. ''Greeks, Hellenes'' (); the name ''Greeks'' () was used by the Ancient Rome, ancient Romans and gradually entered the European language ...

)—and were only Christianized

Christianization (or Christianisation) is a term for the specific type of change that occurs when someone or something has been or is being converted to Christianity. Christianization has, for the most part, spread through missions by individu ...

fully in the 9th century AD, though some church ruins from the 4th century AD indicate that Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

was practiced by some Maniots in the region at an earlier time. The Maniots were the last inhabitants of Greece to openly follow the pagan Hellenic religion. This can be explained by the mountainous nature of Mani's terrain, which enabled them to escape the attempts of the Eastern Roman Empire to Christianize Greece.

Under the Principality of Achaea

During theFourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

(1201–1204), the Crusaders captured Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. The Eastern Roman Empire was partitioned between several Greek and Latin successor states, notably including (from west to east) the Despotate of Epirus

The Despotate of Epirus () was one of the Greek Rump state, successor states of the Byzantine Empire established in the aftermath of the Fourth Crusade in 1204 by a branch of the Angelos dynasty. It claimed to be the legitimate successor of the ...

, the Latin Empire

The Latin Empire, also referred to as the Latin Empire of Constantinople, was a feudal Crusader state founded by the leaders of the Fourth Crusade on lands captured from the Byzantine Empire. The Latin Empire was intended to replace the Byzantin ...

, the Empire of Nicaea

The Empire of Nicaea (), also known as the Nicene Empire, was the largest of the three Byzantine Greeks, Byzantine Greek''A Short history of Greece from early times to 1964'' by Walter Abel Heurtley, W. A. Heurtley, H. C. Darby, C. W. Crawley, C ...

, and the Empire of Trebizond

The Empire of Trebizond or the Trapezuntine Empire was one of the three successor rump states of the Byzantine Empire that existed during the 13th through to the 15th century. The empire consisted of the Pontus, or far northeastern corner of A ...

. These four empires produced rival emperors, struggling for control over each other and the rest of the semi-independent states emerging in the area. William of Champlitte and Geoffrey I Villehardouin defeated the Peloponnesian Greeks at the Battle of the Olive Grove of Koundouros (1205), and the Peloponnese became the Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom of Thes ...

. In 1210, Mani was given to Baron Jean de Neuilly as Hereditary Marshal, and he built the castle of Passavas on the ruins of Las. The castle occupied a significant position, as it controlled an important pass from Gythium to Oitylo

Oitylo (), known as "Βίτσουλο", pronounced Vitsoulo, in the native Maniot dialect, is a village and a former Communities and Municipalities of Greece, municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local ...

and contained the Maniots...

The Maniots, however, were not easily contained, and they were not the only threat to the Frankish occupation of the Peloponnese. The Melengi, a Slavic tribe in the Taygetus

The Taygetus, Taugetus, Taygetos or Taÿgetus () is a mountain range on the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece. The highest mountain of the range is Mount Taygetus, also known as "Profitis Ilias", or "Prophet Elias" (Elijah).

The name is o ...

mountain range

A mountain range or hill range is a series of mountains or hills arranged in a line and connected by high ground. A mountain system or mountain belt is a group of mountain ranges with similarity in form, structure, and alignment that have aris ...

, raided Laconia from the west, and the Tsakonians also resisted the Franks. In 1249, the new prince, William II of Villehardouin

William of Villehardouin (; Kalamata, 1211 – 1 May 1278) was the fourth prince of Achaea in Frankish Greece, from 1246 to 1278. The younger son of Prince Geoffrey I, he held the Barony of Kalamata in fief during the reign of his ...

, acted against the raiders. He used the newly captured fortress of Monemvasia

Monemvasia (, or ) is a town and municipality in Laconia, Greece. The town is located in mainland Greece on a tied island off the east coast of the Peloponnese, surrounded by the Myrtoan Sea. Monemvasia is connected to the rest of the mainland by a ...

to keep the Tsakonians at bay, and he built the castle at Mystras

Mystras or Mistras (), also known in the '' Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzethras or Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mount Taygetus, above ancient Sparta, ...

in the Taygetus mountains overlooking Sparta in order to contain the Melengi. To stop the Maniot raids, he built the castle of Megali Maina, which is most probably Tigani. It is described as ''at a fearful cliff with a headland above''. A Latin bishop was appointed for Mani during the 1250s. In 1259, the bishop was captured during the Battle of Pelagonia by the renewed Byzantine Empire under the leadership of Nicaea..

Under the Despotate of Morea

Michael VIII Palaiologos

Michael VIII Palaiologos or Palaeologus (; 1224 – 11 December 1282) reigned as Byzantine emperor from 1261 until his death in 1282, and previously as the co-emperor of the Empire of Nicaea from 1259 to 1261. Michael VIII was the founder of th ...

recaptured Constantinople. Prince William was set free, on the condition that he had to surrender the fortresses of Megali Maina, Mystras, Geronthrae and Monemvasia, as well as surrender hostages including Lady Margaret, Baroness of Passavas. With the Franks gone from Laconia, the Maniots lived in peace under the Despotate of Morea

The Despotate of the Morea () or Despotate of Mystras () was a province of the Byzantine Empire which existed between the mid-14th and mid-15th centuries. Its territory varied in size during its existence but eventually grew to include almost a ...

, whose successive Despotes

Despot or ''despotes'' () was a senior Byzantine court title that was bestowed on the sons or sons-in-law of reigning emperors, and initially denoted the heir-apparent of the Byzantine emperor.

From Byzantium it spread throughout the late medie ...

governed the province. Mani seems to have been dominated by the Nikliani family, who were refugees. However, the peace was terminated when the Ottoman Turks started their attacks on the Peloponnese.

Ottoman times

15th century

After theOttoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

under Sultan Mehmed II

Mehmed II (; , ; 30 March 14323 May 1481), commonly known as Mehmed the Conqueror (; ), was twice the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from August 1444 to September 1446 and then later from February 1451 to May 1481.

In Mehmed II's first reign, ...

took Constantinople in May 1453, Mani remained under the control of the Despotate of Morea. In May 1460, Mehmed occupied the Peloponnese. The Despotate of Morea had been ruled by the two brothers of Constantine XI, who had died defending Constantinople. However, neither Demetrios Palaiologos

Demetrios Palaiologos or Demetrius Palaeologus (; 1407–1470) was Despot of the Morea together with his brother Thomas from 1449 until the fall of the despotate in 1460. Demetrios and Thomas were sons of Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiolog ...

nor Thomas Palaiologos chose to follow his example and defend the Peloponnese. Instead, Thomas fled to Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, while Demetrios sought refuge with Mehmed. Helena Palaiologina, a daughter of Demetrios and his second wife Theodora Asanina, was given in marriage to Mehmed II.

Krokodeilos Kladas, a Greek from Laconia, was granted lordship by Mehmed over

Krokodeilos Kladas, a Greek from Laconia, was granted lordship by Mehmed over Elos

Elos (, before 1930: Δουραλί - ''Dourali'') is a village and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Evrotas, of which it is a municipal unit. The municip ...

and Vardounia in 1461. Mehmed hoped that Kladas would defend Laconia from the Maniots. During that time, Mani's population grew as a result of an influx of refugees who came from other areas of Greece.. In 1463, Kladas joined the Venetians in their ongoing war against the Ottomans. He led the Maniots against the Ottomans with Venetian aid until 1479, when the Venetians made peace with the Ottomans and gave the Ottomans the right to rule the ''Brazzo di Maina''. Kladas refused to accept the conditions, and so the Venetians put a price on his head.

After the end of the Turko-Venetian War, the Venetians left the Maniots to fend for themselves. Many of the Greeks who had revolted alongside the Venetians were massacred by the Ottomans, but many of them fled to find refuge in Mani. The Maniots continued to resist, and Mehmed dispatched an army of 2,000 infantry and 300 cavalry under the command of Ale Boumico.. The Venetians, trying to gain favor with the Porte, handed over some Maniot rebels. The Ottomans reached Oitylo before Kladas, and the Maniots attacked and massacred them. Only a few escaped; amongst them was Ale Boumico. Kladas invaded the Laconian plain with 14,000 Maniots and killed the Turkish inhabitants..

A month later, a larger force under the command of Ahmed Bey invaded Mani and drove Kladas to Porto Kagio. There, he was picked up by three galleys of King Ferdinand I of Naples

Ferdinand I (2 June 1424 – 25 January 1494), also known as Ferrante, was king of Naples from 1458 to 1494.

The only son, albeit illegitimate, of Alfonso the Magnanimous, he was one of the most influential and feared monarchs in Europe at the ...

. To delay the Turks long enough for Kladas to escape, the Maniot rear guard attacked the Turkish army. Kladas reached the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, whence he became a mercenary leader. He returned to Mani in 1490 and was killed in a battle at Monemvasia.

16th century

From 1500 to 1570, Mani kept its autonomy without any invasion from the Ottomans. The Ottomans were busy driving the Venetians out of the Peloponnese and succeeded in 1540, when theyconquered

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or legal prohibitions against conquest ...

Monemvasia and Nafplio

Nafplio or Nauplio () is a coastal city located in the Peloponnese in Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Argolis and an important tourist destination. Founded in antiquity, the city became an important seaport in the Middle Ages du ...

. The Ottomans under Selim II, preparing to invade the Venetian island of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, built a fortress in Mani, at Porto Kagio, and they also garrisoned Passavas. The aim of this was to disrupt the Venetians' communication lines and to keep the Maniots at bay. Alarmed, the Maniots called upon Venetian assistance, and the Venetian navy in combination with the Maniot army captured the castle..

Cyprus fell later that year, but the fleet of the Holy League defeated the Ottoman fleet at the Battle of Lepanto (1571)

The Battle of Lepanto was a naval engagement that took place on 7 October 1571 when a fleet of the Holy League, a coalition of Catholic states arranged by Pope Pius V, inflicted a major defeat on the fleet of the Ottoman Empire in the Gulf o ...

. The Greeks assumed that John of Austria

John of Austria (, ; 24 February 1547 – 1 October 1578) was the illegitimate son of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Charles V recognized him in a codicil to his will. John became a military leader in the service of his half-brother, King Phi ...

would champion their revolt under the command of the bishop of Monemvasia. The promised army never arrived, and by 1572 the bishop was forced to retreat to Mani. The Maniots did not succeed when they appealed to Pope Gregory VIII

Pope Gregory VIII (; c. 1100/1105 – 17 December 1187), born Alberto di Morra, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States for two months in 1187. Becoming Pope after a long diplomatic career as Apostolic Chancellor, he ...

to convince Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

to provide military support..

17th century

In 1603, the Maniots approached

In 1603, the Maniots approached Pope Clement VIII

Pope Clement VIII (; ; 24 February 1536 – 3 March 1605), born Ippolito Aldobrandini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 30 January 1592 to his death in March 1605.

Born in Fano, Papal States to a prominen ...

, who had recently taken up the cross

A cross is a religious symbol consisting of two Intersection (set theory), intersecting Line (geometry), lines, usually perpendicular to each other. The lines usually run vertically and horizontally. A cross of oblique lines, in the shape of t ...

. Clement died two years later, and the Maniots began to seek a new champion, centering their attention on the King of Spain, Philip III. They urged him to land his army at Porto Kagio and promised to join him with 15,000 armed men as well as 80,000 other Peloponnesians. The Maniots also sent envoys to some major powers of the Mediterranean, as for example the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, the Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the Middle Ages, medieval and Early modern France, early modern period. It was one of the most powerful states in Europe from th ...

, the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

, the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The Grand Duchy of Tuscany (; ) was an Italian monarchy located in Central Italy that existed, with interruptions, from 1569 to 1860, replacing the Republic of Florence. The grand duchy's capital was Florence. In the 19th century the population ...

, and once again Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

. These states were interested and sent several expeditionary forces to Mani, but with the exception of a Spanish expedition that sacked Passavas, they all failed to achieve anything.

The Maniots found a champion in 1612, Charles Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua and Nevers. Charles was a descendant of the Byzantine Emperor Andronikos II Palaiologos

Andronikos II Palaiologos (; 25 March 1259 – 13 February 1332), Latinization of names, Latinized as Andronicus II Palaeologus, reigned as Byzantine emperor from 1282 to 1328. His reign marked the beginning of the recently restored em ...

through his grandmother, who was of the line of Theodore I of Montferrat

Theodore I Palaiologos or Palaeologus (Greek: Θεόδωρος Παλαιολόγος, full name: ''Theodoros Komnenos Doukas Angelos Palaiologos'') ( – 24 April 1338) was Marquis of Montferrat from 1306 until his death.

Life

Theodore was a son ...

, Andronikos' son.. Through this connection he claimed the throne of Constantinople. He began plotting with the Maniots, who addressed him as "King Constantine Palaiologos". When the Porte heard about this, they sent Arslan in command of an army of 20,000 men and 70 ships to invade Mani. He succeeded in ravaging Mani and imposing taxes on the Maniots (which they did not pay). This caused Nevers to move more actively for his crusade. Nevers sent envoys to the courts of Europe looking for support. In 1619, he recruited six ships and a number of men, but he was forced to abort the mission because of the beginning of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

. The idea of the crusade faded and Nevers died in 1637.

In 1645, a new Turkish-Venetian War, the so-called " Cretan War" began, during which the Republic of Venice was attempting to defend Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

, one of their provinces since 1204, from the Ottoman Empire, initially under Ibrahim I. The Maniots supported the Venetians by offering them ships. In 1659, Admiral Francesco Morosini

Francesco Morosini (26 February 1619 – 16 January 1694) was the Doge of Venice from 1688 to 1694, at the height of the Great Turkish War. He was one of the many Doges and generals produced by the Venetian noble Morosini family.Encyclopæd ...

, with 13,000 Maniots as his allies, occupied Kalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

, a large city near Mani. In 1667, during the Siege of Candia, some Maniot pirate ships sneaked into the Ottoman fleet and managed to loot and burn some ships. However, Candia fell in 1669, and Crete became part of the Ottoman Empire. The piracy of Maniots was also observed by Evliya Çelebi

Dervish Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi (), was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman explorer who travelled through his home country during its cultural zenith as well as neighboring lands. He travelled for over 40 years, rec ...

, who visited Mani with the Ottoman expedition and recorded numerous villages, castles and churches; he described the Maniots with the following words: "They capture the Frank and sell him to us, they capture us and sell us to the Franks."

With Crete captured, the Ottomans turned their attention to Mani. The Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

, Köprülü Fazıl Ahmet Pasha, sent the pirate Hasan Baba to subdue Mani. Baba arrived in Mani demanding that the Maniots surrender hostages, but instead he was answered with bullets. During the night, ten Maniots went and cut the hawsers of Hasan's ships. This caused some of Baba's ships to founder on some rocks, and the Maniots, taking advantage of the situation, attacked and killed the Turks and seized the ships. Baba managed to escape with only one ship..

In the Bagnio

Bagnio is a loan word into several languages (from ). In English, French, and so on, it has developed varying meanings: typically a brothel, bath-house, or prison for slaves.

In reference to the Ottoman Empire

The origin of this sense seems to ...

of Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

, there was a notorious twenty-five-year-old Maniot pirate named Limberakis Gerakaris. At the age of fifteen, he was in the Venetian galleys as a rower. After being released by the Venetians, he continued piracy and was captured by the Turks in 1667. The Grand Vizier decided to give him amnesty if he cooperated with the Turks and helped them conquer Mani. Gerakaris agreed and in 1670 became the bey of Mani. One of Gerakis' first acts was to exile his clan's enemies, the Iatriani family and the Stephanopoulos family from Oitylo. The Iatriani fled in 1670 and settled in Livorno

Livorno () is a port city on the Ligurian Sea on the western coast of the Tuscany region of Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Livorno, having a population of 152,916 residents as of 2025. It is traditionally known in English as Leghorn ...

, Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

. The Stephanopoulos clan was forced to leave Oitylo in 1676, and after having gained permission from the Republic of Genoa

The Republic of Genoa ( ; ; ) was a medieval and early modern Maritime republics, maritime republic from the years 1099 to 1797 in Liguria on the northwestern Italy, Italian coast. During the Late Middle Ages, it was a major commercial power in ...

, went to Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

. The Stephanopoulos family first lived in the town of Paomia before moving to Cargèse, and to this day consider themselves Greeks.. See also Nicholas, 2006.

Limberakis soon fell out of favor with the Turks since he joined his fellow Maniots in piracy and was captured in 1682.. With Ottoman forces preoccupied with the Austrians, the Venetians under Morosini saw their opportunity to take over Turkish-held territories in the Peloponnese, beginning the Morean War

The Morean war (), also known as the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War, was fought between 1684–1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the "Great Turkish War", between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Military operations ranged ...

. The Turkish general in the Peloponnese, Ismael, discovered this plan and attacked Mani with 10,000 men. The Turks ravaged the plains, but during the night the Maniots attacked and killed 1,800 Turks. The other Turks retreated to the castles of Kelefa and Zarnatas, where they were besieged by the Maniots. After brief sieges, the Maniots managed to capture both Koroni and Kelefa. However, Ismael returned with 10,000 infantry and 2,500 artillery and started besieging the Maniots at Kelefa. The Turks nearly succeeded in breaching the walls before 4,500 Venetians under the command of Morosini arrived and forced the Turks to retreat to Kastania with the Maniots in pursuit...

The Venetians, with assistance of the Greeks, conquered the rest of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

and then besieged Athens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

. During the siege of Athens, the Ottomans used the Parthenon as an ammunition depot. When artillery fire from the Venetians struck the depot, the resulting explosion damaged large portions of the Parthenon. The desperate Ottomans freed Limberakis and gave him the title "His Highness, the Ruler of Mani". Limberakis immediately launched several raids into Venetian-held territories of the Peloponnese. However, when the Ottomans attempted to poison Limberakis, he defected to the Venetian side... The Venetians made Limberakis a Knight of St. Mark and recognized him as ruler of Roumeli. Limberakis first attacked the city of Arta, when the Ottomans destroyed his estates at Karpenisi

Karpenisi (, ) is a town in central Greece. It is the capital of the regional unit of Evrytania. Karpenisi lies within the valley of the river Karpenisiotis (Καρπενησιώτης), a tributary of the Megdovas, in the southern part of the ...

. He captured and plundered the city before going back to Mani. The Arteans sent a committee to Venice and reported everything to the Doge

Doge, DoGE or DOGE may refer to:

Internet culture

* Doge (meme), an Internet meme primarily associated with the Shiba Inu dog breed

** Dogecoin, a cryptocurrency named after the meme

** Kabosu (dog), the dog portrayed in the original Doge image ...

. Ultimately, Limberakis moved to Italy where he died fourteen years later.

18th century

In 1715, the Ottomans attacked the Peloponnese and managed to drive out the Venetians within seventy days. The Venetians won some minor naval battles off Mani but abandoned the Peloponnese in 1715. The next year, the Treaty of Passarowitz was signed, and the Venetians abandoned their claim to the Peloponnese..Orlov Revolt

Georgios Papazolis, a Greek officer of the Russian army, was a friend of the Orlovs and had them convinceCatherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

to send an army to Mani and liberate Greece. A Russian fleet of five ships and 500 soldiers under the command of Aleksey Grigoryevich Orlov sailed from the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

in 1769 and reached Mani in 1770. The fleet landed at Oitylo, where it was met by the Maniots. It was decided to divide the army into two groups, the ''Western Legion'' and the ''Eastern Legion''. The Eastern Legion, under the command of Barkof, Grigorakis, and Psaros, consisted of 500 Maniots and 6 Russians. The Western Legion, under the command of John Mavromichalis (nicknamed ''The Dog''), Piotr Dolgorukov, and Panagiotis Koumoundouros, consisted of 200 Maniots and 12 Russians.

Meanwhile, the Russian fleet was besieging Koroni with assistance from the Western Legion. The siege proved to be difficult, and soon Orlov got into a dispute with John the Dog. Mavromichalis stated to Orlov that if they wanted to start a real war, they had to occupy Koroni, and that if they did not, they should not excite the Greeks in vain. Orlov replied by calling the Maniots "ragged" and "rude booty men". To this, Mavromichalis replied, "The last of these ragged booty men keeps his freedom with his own sword and deserves more than you, slave of a whore!". The Russians left and conducted their own operations until the end of the year, when they ultimately sailed back to Russia.

The Eastern Legion met with success when it defeated an army of 3,500 Turks. The Ottomans responded to this by sending an army of 8,000 to invade the Peloponnese. The Ottoman army first plundered Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

before entering the Peloponnese. At Rizomylos in Messenia, they were blocked by John Mavromichalis and 400 of his followers. The Maniots held them off for a while, but the Ottoman forces eventually did not lose due to their superior numbers. They captured John Mavromichalis, who was not only seriously wounded but also the last survivor of the battle. He was ultimately tortured to death. They then invaded Mani and began ravaging the land near Almiros (near the modern village of Kyparissos). During the night, an army of 5,000 Maniot men and women attacked the enemy camp. The Ottoman forces lost 1,700, while the Maniots only suffered thirty-nine casualties.

Ottoman invasion of Mani (1770)

Around 1770, the Ottoman commander Hasan Ghazi with 16,000 men besieged the two fighting towers (pyrgoi) of Venetsanakis clan in Kastania. The defenders were Constantine Kolokotronis and Panagiotis Venetsanakis with 150 men and women. The fight lasted for twelve days: most of the defenders were killed, and all prisoners of war were tortured and dismembered. The wife of Constantine Kolokotronis was dressed like a warrior and fought her way out carrying her baby,Theodoros Kolokotronis

Theodoros Kolokotronis (; 3 April 1770 – ) was a Greek general and the pre-eminent leader of the Greek War of Independence (1821–1829) against the Ottoman Empire.

The son of a klepht leader who fought the Ottomans during the Orlov revolt ...

, the future commander of the Greek War of Independence.

From Kastania, Hasan Ghazi advanced towards Skoutari and laid siege to the tower of the powerful Grigorakis clan. The tower contained fifteen men, who held out for three days until the Turks undermined the tower, placed gunpowder, and blew up the entire garrison. By this time, the main Maniot army of 5,000 men and 2,000 women had established a defensive position which was on mountainous terrain above the town of Parasyros. The entire army was under the command of Exarchos Grigorakis and his nephew Zanetos Grigorakis. The Ottoman army advanced to the plain of Agio Pigada (meaning "Holy Well"). They sent envoys to the Maniots telling them that Hasan wanted to negotiate. The Maniots knew that if they sent envoys to the Turks, they would be executed by Hasan if the negotiations failed. However, the Maniots sent six men to discuss the terms.

Six Maniot envoys were sent to Hasan and, without bowing, asked him what he wanted. Hasan's demands entailed the children of ten captains as hostages, all Maniot-held arms, and an annual head-tax to be paid as punishment for supporting the Russians. The Maniots answered Hasan's demands saying, "We prefer to die rather than give to you our guns and children. We don't pay taxes, because our land is poor." Hasan became furious and had the six men decapitated and impaled on stakes so that the Maniots could see them..

After the envoys were killed, the remaining Maniots attacked the Ottomans. The fighting was fierce, and only 6,000 Turks managed to reach

From Kastania, Hasan Ghazi advanced towards Skoutari and laid siege to the tower of the powerful Grigorakis clan. The tower contained fifteen men, who held out for three days until the Turks undermined the tower, placed gunpowder, and blew up the entire garrison. By this time, the main Maniot army of 5,000 men and 2,000 women had established a defensive position which was on mountainous terrain above the town of Parasyros. The entire army was under the command of Exarchos Grigorakis and his nephew Zanetos Grigorakis. The Ottoman army advanced to the plain of Agio Pigada (meaning "Holy Well"). They sent envoys to the Maniots telling them that Hasan wanted to negotiate. The Maniots knew that if they sent envoys to the Turks, they would be executed by Hasan if the negotiations failed. However, the Maniots sent six men to discuss the terms.

Six Maniot envoys were sent to Hasan and, without bowing, asked him what he wanted. Hasan's demands entailed the children of ten captains as hostages, all Maniot-held arms, and an annual head-tax to be paid as punishment for supporting the Russians. The Maniots answered Hasan's demands saying, "We prefer to die rather than give to you our guns and children. We don't pay taxes, because our land is poor." Hasan became furious and had the six men decapitated and impaled on stakes so that the Maniots could see them..

After the envoys were killed, the remaining Maniots attacked the Ottomans. The fighting was fierce, and only 6,000 Turks managed to reach Mystras

Mystras or Mistras (), also known in the '' Chronicle of the Morea'' as Myzethras or Myzithras (Μυζηθρᾶς), is a fortified town and a former municipality in Laconia, Peloponnese, Greece. Situated on Mount Taygetus, above ancient Sparta, ...

. No one knew exactly how many casualties the Maniots suffered, but the Turks definitively lost 10,000 men. In 1780, Hasan Ghazi, the Bey of the Peloponnese, tried to weaken the Grigorakis family by arranging the assassination of Exarchos Grigorakis. He invited him to Tripolitsa and treated him as an honored guest but then had him hanged.. On Easter Sunday, Exarchos' mother incited the men of Skoutari to take revenge for the death of her son.. Commanded by Zanetos Grigorakis, the men of Skoutari dressed as priests and were allowed into Passavas. Once inside, the Skoutariotes took out their concealed weapons and killed all the Turkish inhabitants of Passavas..

In 1782, the Ottomans lured Michalis Troupakis, Bey of Mani, onto a ship and sent him to Lesbos

Lesbos or Lesvos ( ) is a Greek island located in the northeastern Aegean Sea. It has an area of , with approximately of coastline, making it the third largest island in Greece and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, eighth largest ...

, where he was executed for piracy. The Porte tried to get Zanetos Grigorakis to replace him, but Zanetos refused until he was lured onto a ship and forced to become bey..

Soon after the Orlov Expedition, a number of Maniots entered Russian military service. Remnants of the two legions joined Russian sea forces as marines, participating in operations in the Aegean and the eastern Mediterranean. Two leaders of these volunteers, Stephanos Mavromichalis and Dimitrios Grigorakis, were scions of the main Maniot clans, each rising to the rank of major.

Lambros Katsonis

Catherine II of Russia

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

had her representative Alexander Bezborodko sign the Treaty of Jassy with Grand Vizier

Grand vizier (; ; ) was the title of the effective head of government of many sovereign states in the Islamic world. It was first held by officials in the later Abbasid Caliphate. It was then held in the Ottoman Empire, the Mughal Empire, the Soko ...

Koca Yusuf Pasha of the Ottoman Empire. The treaty ended the Russo-Turkish War, recognized Russia's 1783 annexation of the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

, and transferred Yedisan to Russia, making the Dniester

The Dniester ( ) is a transboundary river in Eastern Europe. It runs first through Ukraine and then through Moldova (from which it more or less separates the breakaway territory of Transnistria), finally discharging into the Black Sea on Uk ...

the Russo-Turkish frontier in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

while leaving the Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

tic frontier (Kuban River

The Kuban is a river in Russia that flows through the Western Caucasus and drains into the Sea of Azov. The Kuban runs mostly through Krasnodar Krai for , but also in the Karachay–Cherkess Republic, Stavropol Krai and the Republic of Adygea. ...

) unchanged.. Lambros Katsonis said: "Aikaterini (Greek: Catherine) made her treaty, but Katsonis didn't make his treaty with the enemy."