The following list is composed of (largely) unknown lands that were discovered by people from the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, or being the first documented Europeans to discover certain areas.

Explorations

Orange Islands (1594)

During his first journey in 1594, Dutch explorer

Willem Barentsz

Willem Barentsz (; – 20 June 1597), anglicized as William Barents or Barentz, was a Dutch Republic, Dutch navigator, cartographer, and Arctic explorer.

Barentsz went on three expeditions to the far north in search for a Northern Sea Route, N ...

discovered the

Orange Islands, at the northern extremity of

Nova Zembla.

Svalbard (1596)

On 10 June 1596, Barentsz and Dutchman

Jacob van Heemskerk

Jacob van Heemskerck (3 March 1567 – 25 April 1607) was a Dutch explorer and naval officer. He is generally known for his victory over the Spanish at the Battle of Gibraltar, where he ultimately lost his life.

Early life

Jacob van Hee ...

discovered

Bear Island,

[Grimbly, Shona (2001). ''Atlas of Exploration'', p. 47][Mills, William J. (2003). ''Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1'', p. 62–65][Pletcher, Kenneth (2010). ''The Britannica Guide to Explorers and Explorations That Changed the Modern World'', p. 162] a week before their discovery of Spitsbergen Island.

The first undisputed discovery of the archipelago was an expedition led by the Dutch mariner

Willem Barentsz

Willem Barentsz (; – 20 June 1597), anglicized as William Barents or Barentz, was a Dutch Republic, Dutch navigator, cartographer, and Arctic explorer.

Barentsz went on three expeditions to the far north in search for a Northern Sea Route, N ...

, who was looking for the

Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (, shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route about long. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is the shortest shipping route between the western part of Eurasia and the Asia-Pacific region.

Ad ...

to China.

[Arlov (1994): 9] He first spotted

Bjørnøya on 10 June 1596 and the northwestern tip of

Spitsbergen

Spitsbergen (; formerly known as West Spitsbergen; Norwegian language, Norwegian: ''Vest Spitsbergen'' or ''Vestspitsbergen'' , also sometimes spelled Spitzbergen) is the largest and the only permanently populated island of the Svalbard archipel ...

on 17 June.

The sighting of the archipelago was included in the accounts and maps made by the expedition and Spitsbergen was quickly included by cartographers. The name ''Spitsbergen'', meaning "pointed mountains" (from the

Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

''spits'' – pointed, ''bergen'' – mountains), was at first applied to both the

main island and the

Svalbard archipelago

Svalbard ( , ), previously known as Spitsbergen or Spitzbergen, is a Norway, Norwegian archipelago that lies at the convergence of the Arctic Ocean with the Atlantic Ocean. North of continental Europe, mainland Europe, it lies about midway be ...

as a whole.

Winter surviving in the High Arctic (1596–1597)

The search for the

Northern Sea Route

The Northern Sea Route (NSR) (, shortened to Севморпуть, ''Sevmorput'') is a shipping route about long. The Northern Sea Route (NSR) is the shortest shipping route between the western part of Eurasia and the Asia-Pacific region.

Ad ...

in the 16th century led to its exploration.

Dutch explorer

Willem Barentsz

Willem Barentsz (; – 20 June 1597), anglicized as William Barents or Barentz, was a Dutch Republic, Dutch navigator, cartographer, and Arctic explorer.

Barentsz went on three expeditions to the far north in search for a Northern Sea Route, N ...

reached the west coast of

Novaya Zemlya

Novaya Zemlya (, also , ; , ; ), also spelled , is an archipelago in northern Russia. It is situated in the Arctic Ocean, in the extreme northeast of Europe, with Cape Flissingsky, on the northern island, considered the extreme points of Europe ...

in 1594,

and in a subsequent expedition of 1596 rounded the Northern point and wintered on the Northeast coast.

Willem Barentsz

Willem Barentsz (; – 20 June 1597), anglicized as William Barents or Barentz, was a Dutch Republic, Dutch navigator, cartographer, and Arctic explorer.

Barentsz went on three expeditions to the far north in search for a Northern Sea Route, N ...

,

Jacob van Heemskerck

Jacob van Heemskerck (3 March 1567 – 25 April 1607) was a Dutch explorer and naval officer. He is generally known for his victory over the Spanish at the Battle of Gibraltar, where he ultimately lost his life.

Early life

Jacob van Hee ...

and their crew were blocked by the pack ice in the

Kara Sea

The Kara Sea is a marginal sea, separated from the Barents Sea to the west by the Kara Strait and Novaya Zemlya, and from the Laptev Sea to the east by the Severnaya Zemlya archipelago. Ultimately the Kara, Barents and Laptev Seas are all ...

and forced to winter on the east coast of Novaya Zemlya. The wintering of the shipwrecked crew in the 'Saved House' was the first successful wintering of Europeans in the High Arctic. Twelve of the 17 men managed to survive the polar winter (De Veer, 1917). Barentsz died during the expedition, and may have been buried on the northern island.

Falkland Islands/Sebald Islands (1600)

In 1600 the Dutch navigator

Sebald de Weert

Sebald or Sebald de Weert (May 2, 1567 – May 30 or June 1603) was a Flemish captain and vice-admiral of the Dutch East India Company (known in Dutch as ''Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie'', VOC). He is most widely remembered for accurately p ...

made the first undisputed sighting of the

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

. It was on his homeward leg back to the

Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

after having left the

Straits of Magellan

The Strait of Magellan (), also called the Straits of Magellan, is a navigable sea route in southern Chile separating mainland South America to the north and the Tierra del Fuego archipelago to the south. Considered the most important natural ...

that

Sebald De Weert

Sebald or Sebald de Weert (May 2, 1567 – May 30 or June 1603) was a Flemish captain and vice-admiral of the Dutch East India Company (known in Dutch as ''Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie'', VOC). He is most widely remembered for accurately p ...

noticed some unnamed and uncharted islands, at least islands that did not exist on his

nautical chart

A nautical chart or hydrographic chart is a graphic representation of a sea region or water body and adjacent coasts or river bank, banks. Depending on the scale (map), scale of the chart, it may show depths of water (bathymetry) and heights of ...

s. There he attempted to stop and replenish but was unable to land due to harsh conditions. The

islands

This is a list of the lists of islands in the world grouped by country, by continent, by body of water, and by other classifications. For rank-order lists, see the #Other lists of islands, other lists of islands below.

Lists of islands by count ...

Sebald de Weert charted were a small group off the northwest coast of the

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

and are in fact part of the Falklands. De Weert then named these islands the "Sebald de Weert Islands" and the Falklands as a whole were known as the

Sebald Islands

The history of the Falkland Islands () goes back at least five hundred years, with active exploration and colonisation only taking place in the 18th century. Nonetheless, the Falkland Islands have been a matter of controversy, as they have been ...

until well into the 18th century.

Pennefather River, Northern Australia (1606)

The Dutch ship,

Duyfken

''Duyfken'' (; ), also in the form ''Duifje'' or spelled ''Duifken'' or ''Duijfken'', was a small ship built in the Dutch Republic. She was a fast, lightly armed ship probably intended for shallow water, small valuable cargoes, bringing messages ...

, led by

Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ) was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. He served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 1603–1611 and 1612–1616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of Solor. During his voyage of 1605–1606 ...

, made the first documented European landing in Australia in 1606. Although a

theory of Portuguese discovery in the 1520s exists, it lacks definitive evidence. Precedence of discovery has also been claimed for

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

,

France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

,

[Credit for the discovery of Australia was given to Frenchman ]Binot Paulmier de Gonneville

Binot Paulmier, sieur de Gonneville, French navigator of the early 16th century, was widely believed in 17th and 18th century France to have been the discoverer of the Terra Australis. Some history books from the French region of Normandy have tau ...

(1504) in Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

,

[In the early 20th century, ]Lawrence Hargrave

Lawrence Hargrave, MRAeS, (29 January 18506 July 1915) was an Australian engineer, explorer, astronomer, inventor and aeronautical pioneer. He was perhaps best known for inventing the box kite, which was quickly adopted by other aircraft desig ...

argued from archaeological evidence that Spain had established a colony in Botany Bay in the 16th century. India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

,

and even

Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

.

[This claim was made by Allan Robinson in his self-published ''In Australia, Treasure is not for the Finder'' (1980); for discussion, see ]

The

Janszoon voyage of 1605–06 Janszoon usually abbreviated to Jansz was a Dutch language, Dutch patronym ("son of Jan (name), Jan"). While Janse, Janssens, and especially Jansen (surname), Jansen and Janssen (surname), Janssen, are very common surnames derived from this patronym ...

led to the first undisputed sighting of Australia by a European was made on 26 February 1606. Dutch vessel ''

Duyfken

''Duyfken'' (; ), also in the form ''Duifje'' or spelled ''Duifken'' or ''Duijfken'', was a small ship built in the Dutch Republic. She was a fast, lightly armed ship probably intended for shallow water, small valuable cargoes, bringing messages ...

'', captained by Janszoon, followed the coast of

New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu: ''Niu Gini''; , fossilized , also known as Papua or historically ) is the List of islands by area, world's second-largest island, with an area of . Located in Melanesia in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, the island is ...

, missed

Torres Strait

The Torres Strait (), also known as Zenadh Kes ( Kalaw Lagaw Ya#Phonology 2, �zen̪ad̪ kes, is a strait between Australia and the Melanesian island of New Guinea. It is wide at its narrowest extent. To the south is Cape York Peninsula, ...

, and explored perhaps of western side of

Cape York, in the

Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria is a sea off the northern coast of Australia. It is enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea, which separates Australia and New Guinea. The northern boundary ...

, believing the land was still part of New Guinea. The Dutch made one landing, but were promptly attacked by

Maoris mpossible - Maoris are from New Zealandand subsequently abandoned further exploration.

The first recorded European sighting of the Australian mainland, and the first recorded European landfall on the Australian continent, are attributed to the Dutch navigator

Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ) was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. He served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 1603–1611 and 1612–1616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of Solor. During his voyage of 1605–1606 ...

. He sighted the coast of

Cape York Peninsula

The Cape York Peninsula is a peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth's last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación Sierra Madre, ...

in early 1606, and made landfall on 26 February at the

Pennefather River

The Pennefather River is a river located on the western Cape York Peninsula in Far North Queensland, Australia.

Location and features

Formed by the confluence of a series of waterways including the Fish Creek in the Port Musgrave Aggregation ...

near the modern town of

Weipa

Weipa () is a coastal mining town in the local government area of Weipa Town in Queensland. It is one of the largest towns on the Cape York Peninsula. It exists because of the enormous bauxite deposits along the coast. The Port of Weipa is main ...

on Cape York.

[ p. 233.] The Dutch charted the whole of the western and northern coastlines and named the island continent "

New Holland" during the 17th century, but made no attempt at settlement.

[

]

First charting of Manhattan, New York (1609)

The area that is now Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

was long inhabited by the Lenape

The Lenape (, , ; ), also called the Lenni Lenape and Delaware people, are an Indigenous peoples of the Northeastern Woodlands, Indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands, who live in the United States and Canada.

The Lenape's historica ...

Indians. In 1524, Florentine explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano

Giovanni da Verrazzano ( , ; often misspelled Verrazano in English; 1491–1528) was an Italian ( Florentine) explorer of North America, who led most of his later expeditions, including the one to America, in the service of King Francis I of ...

– sailing in service of the king Francis I of France

Francis I (; ; 12 September 1494 – 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoulême, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis&nbs ...

– was the first European to visit the area that would become New York City. It was not until the voyage of Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the Northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

, an Englishman who worked for the Dutch East India Company, that the area was mapped.

Hudson Valley (1609)

At the time of the arrival of the first Europeans in the 17th century, the Hudson Valley

The Hudson Valley or Hudson River Valley comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. The region stretches from the Capital District (New York), Capital District includi ...

was inhabited primarily by the Algonquian-speaking Mahican

The Mohicans ( or ) are an Eastern Algonquian Native American tribe that historically spoke an Algonquian language. As part of the Eastern Algonquian family of tribes, they are related to the neighboring Lenape, whose indigenous territory was ...

and Munsee

The Munsee () are a subtribe and one of the three divisions of the Lenape. Historically, they lived along the upper portion of the Delaware River, the Minisink, and the adjacent country in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. They were prom ...

Native American people, known collectively as River Indians. The first Dutch settlement was in the 1610s at Fort Nassau, a trading post (factorij) south of modern-day Albany, that traded European goods for beaver

Beavers (genus ''Castor'') are large, semiaquatic rodents of the Northern Hemisphere. There are two existing species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers are the second-large ...

pelts. Fort Nassau was later replaced by Fort Orange

Fort Orange () was the first permanent Dutch settlement in New Netherland; the present-day city and state capital Albany, New York developed near this site. It was built in 1624 as a replacement for Fort Nassau, which had been built on n ...

. During the rest of the 17th century, the Hudson Valley formed the heart of the New Netherland

New Netherland () was a colony of the Dutch Republic located on the East Coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod. Settlements were established in what became the states ...

colony operations, with the New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam (, ) was a 17th-century Dutch Empire, Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''Factory (trading post), fac ...

settlement on Manhattan serving as a post for supplies and defense of the upriver operations.

Brouwer Route (1610–1611)

The Brouwer Route

The Brouwer Route was a 17th-century route used by ships sailing from the Cape of Good Hope to the Dutch East Indies, as the eastern leg of the Cape Route. The route took ships south from the Cape (which is at 34° latitude south) into the Roari ...

was a route for sailing from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

to Java

Java is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea (a part of Pacific Ocean) to the north. With a population of 156.9 million people (including Madura) in mid 2024, proje ...

. The Route took ships south from the Cape into the Roaring Forties

The Roaring Forties are strong westerlies, westerly winds that occur in the Southern Hemisphere, generally between the latitudes of 40th parallel south, 40° and 50th parallel south, 50° south. The strong eastward air currents are caused by ...

, then east across the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or approximately 20% of the water area of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia (continent), ...

, before turning northwest for Java. Thus it took advantage of the strong westerly winds for which the Roaring Forties are named, greatly increasing travel speed. It was devised by Dutch sea explorer Hendrik Brouwer

Hendrik Brouwer (; 1581 – 7 August 1643) was a Dutch explorer and governor of the Dutch East Indies.

East Indies

Brouwer is thought to first have sailed to the Dutch East Indies for the Dutch East India Company in 1606. In 1610, he lef ...

in 1611, and found to halve the duration of the journey from Europe to Java, compared to the previous Arab and Portuguese monsoon

A monsoon () is traditionally a seasonal reversing wind accompanied by corresponding changes in precipitation but is now used to describe seasonal changes in Atmosphere of Earth, atmospheric circulation and precipitation associated with annu ...

route, which involved following the coast of East Africa northwards, sailing through the Mozambique Channel

The Mozambique Channel (, , ) is an arm of the Indian Ocean located between the Southeast African countries of Madagascar and Mozambique. The channel is about long and across at its narrowest point, and reaches a depth of about off the coa ...

and then across the Indian Ocean, sometimes via India. The Brouwer Route played a major role in the discovery of the west coast of Australia.

Jan Mayen Island (1614)

After unconfirmed reports of Dutch discovery as early as 1611, the island was named after Dutchman Jan Jacobszoon May van Schellinkhout

Jan Jacobszoon May van Schellinkhout () was a Dutch seafarer and explorer.

Family

May was born in the small village of Schellinkhout, just east of the town of Hoorn in North Holland. He appears to be the brother of Cornelis Jacobsz May, the fir ...

, who visited the island in July 1614. As locations of these islands were kept secret by the whalers, Jan Mayen got its current name only in 1620.

Hell Gate, Long Island Sound, Connecticut River and Fisher's Island (1614)

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'', which could mean either "hell's hole" or "bright gate/passage". It was originally applied to the entirety of the

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'', which could mean either "hell's hole" or "bright gate/passage". It was originally applied to the entirety of the East River

The East River is a saltwater Estuary, tidal estuary or strait in New York City. The waterway, which is not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates Long Island, ...

. The strait

A strait is a water body connecting two seas or water basins. The surface water is, for the most part, at the same elevation on both sides and flows through the strait in both directions, even though the topography generally constricts the ...

was described in the journals of Dutch explorer Adriaen Block

Adriaen Courtsen Block (c. 1567 – 27 April 1627) was a Dutch private trader, privateer, and ship's captain who is best known for exploring the coastal and river valley areas between present-day New Jersey and Massachusetts during four voyages ...

, who is the first European known to have navigated the strait, during his 1614 voyage aboard the ''Onrust

The ''Onrust'' (; ) was a Dutch ship built by Adriaen Block and the crew of the '' Tyger'', which had been destroyed by fire in the winter of 1613. The ''Onrust'' was the first ship to be built in what is now New York State, and the first fur tra ...

''.

The first European to record the existence of Long Island Sound

Long Island Sound is a sound (geography), marine sound and tidal estuary of the Atlantic Ocean. It lies predominantly between the U.S. state of Connecticut to the north and Long Island in New York (state), New York to the south. From west to east, ...

and the Connecticut River

The Connecticut River is the longest river in the New England region of the United States, flowing roughly southward for through four states. It rises 300 yards (270 m) south of the U.S. border with Quebec, Canada, and discharges into Long Isl ...

was Dutch explorer Adriaen Block

Adriaen Courtsen Block (c. 1567 – 27 April 1627) was a Dutch private trader, privateer, and ship's captain who is best known for exploring the coastal and river valley areas between present-day New Jersey and Massachusetts during four voyages ...

, who entered it from the East River in 1614.

Fishers Island

Fishers Island is an island within the town of Southold in Suffolk County, New York. It lies at the eastern end of Long Island Sound, off the southeastern coast of Connecticut, across Fishers Island Sound. About long and wide, it is about ...

was called ''Munnawtawkit'' by the Native American

Native Americans or Native American usually refers to Native Americans in the United States.

Related terms and peoples include:

Ethnic groups

* Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the pre-Columbian peoples of North, South, and Central America ...

Pequot

The Pequot ( ) are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut includin ...

nation. Block named it ''Visher's Island'' in 1614, after one of his companions. For the next 25 years, it remained a wilderness, visited occasionally by Dutch traders.

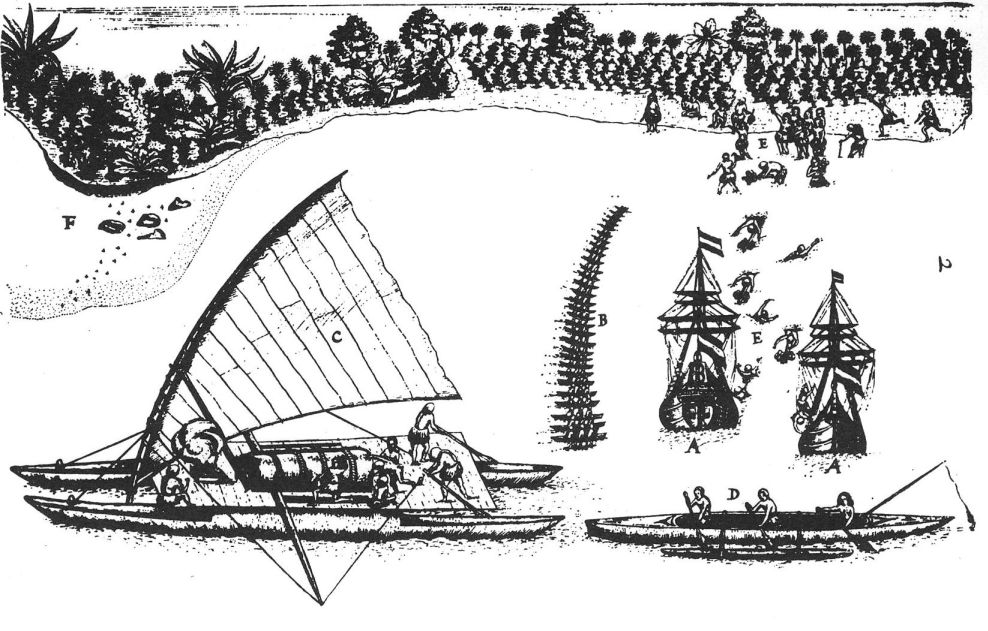

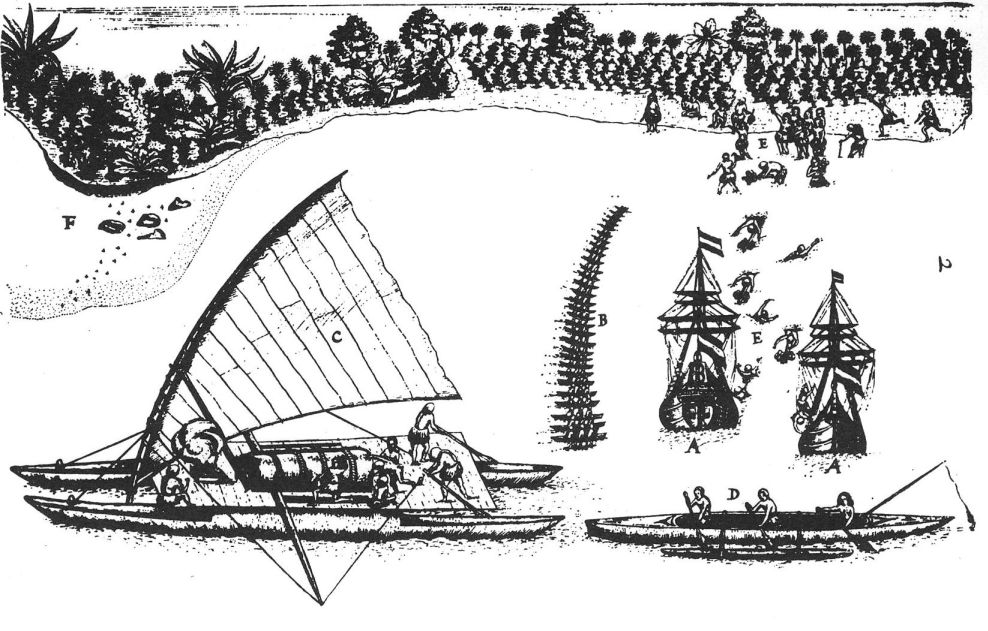

Staten Island (Argentina), Cape Horn, Tonga, Hoorn Islands (1615)

On 25 December 1615, Dutch explorers Jacob le Maire

Jacob Le Maire (c. 1585 – 22 December 1616) was a Dutch mariner who circumnavigated the Earth in 1615 and 1616. The strait between Tierra del Fuego and Isla de los Estados was named the Le Maire Strait in his honour, though not without contro ...

and Willem Schouten

Willem Cornelisz Schouten (1625) was a Dutch navigator for the Dutch East India Company. He was the first to sail the Cape Horn route to the Pacific Ocean.

Biography

Willem Cornelisz Schouten was born around 1567 in Hoorn, Holland, Seve ...

aboard the Eendracht, discovered Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

, close to Cape Horn.

On 29 January 1616, they sighted land they called

On 29 January 1616, they sighted land they called Cape Horn

Cape Horn (, ) is the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago of southern Chile, and is located on the small Hornos Island. Although not the most southerly point of South America (which is Águila Islet), Cape Horn marks the nor ...

, after the city of Hoorn. Aboard the Eendracht was the crew of the recently wrecked ship called Hoorn.

They discovered

They discovered Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

on 21 April 1616 and the Hoorn Islands

The Hoorn Islands (also Futuna Islands, French: îles Horn) are one of the two island groups of which the French overseas collectivity (''collectivité d'outre-mer'', or ''COM'') of Wallis and Futuna is geographically composed. The aggregate are ...

on 28 April 1616.

They discovered New Ireland around May–July 1616.

They discovered the Schouten Islands

The Biak Islands (, also Schouten Islands or Geelvink Islands) are an island group of Southwest Papua province, eastern Indonesia in the Cenderawasih Bay (or Geelvink Bay) 50 km off the north-western coast of the island of New Guinea. Th ...

(also known as ''Biak Islands'' or ''Geelvink Islands'') on 24 July 1616.

The Schouten Islands (also known as ''Eastern Schouten Islands'' or ''Le Maire Islands'') of Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea, officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea, is an island country in Oceania that comprises the eastern half of the island of New Guinea and offshore islands in Melanesia, a region of the southwestern Pacific Ocean n ...

, were named after Schouten, who visited them in 1616.

Dirk Hartog Island (1616)

Hendrik Brouwer

Hendrik Brouwer (; 1581 – 7 August 1643) was a Dutch explorer and governor of the Dutch East Indies.

East Indies

Brouwer is thought to first have sailed to the Dutch East Indies for the Dutch East India Company in 1606. In 1610, he lef ...

's discovery that sailing east from the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

until land was sighted, and then sailing north along the west coast of Australia was a much quicker route than around the coast of the Indian Ocean made Dutch landfalls on the west coast inevitable. The first such landfall was in 1616, when Dirk Hartog

Dirk Hartog (; baptised 30 October 1580 – buried 11 October 1621) was a 17th-century Dutch sailor and explorer. Dirk Hartog's expedition was the second European group to land in Australia and the first to leave behind an artifact to record hi ...

landed at Cape Inscription on what is now known as Dirk Hartog Island

Dirk Hartog Island is an island off the Gascoyne (Western Australia), Gascoyne coast of Western Australia, within the Shark Bay, Western Australia, Shark Bay World Heritage Area. It is about long and between wide and is Western Australia's ...

, off the coast of Western Australia, and left behind an inscription on a pewter

Pewter () is a malleable metal alloy consisting of tin (85–99%), antimony (approximately 5–10%), copper (2%), bismuth, and sometimes silver. In the past, it was an alloy of tin and lead, but most modern pewter, in order to prevent lead poi ...

plate. In 1697 the Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh

Willem Hesselsz de Vlamingh (baptized 28 November 1640 – after 7 August 1702) was a Dutch sea captain who explored the central west coast of New Holland (Australia) in the late 17th century, where he landed in what is now Perth on the Swan ...

landed on the island and discovered Hartog's plate. He replaced it with one of his own, which included a copy of Hartog's inscription, and took the original plate home to Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , ; ; ) is the capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, largest city of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. It has a population of 933,680 in June 2024 within the city proper, 1,457,018 in the City Re ...

, where it is still kept in the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

The Rijksmuseum () is the national museum of the Netherlands dedicated to Dutch arts and history and is located in Amsterdam. The museum is located at the Museumplein, Museum Square in the stadsdeel, borough of Amsterdam-Zuid, Amsterdam South, ...

.

Houtman Abrolhos (1619)

The first sighting of the Houtman Abrolhos

The Houtman Abrolhos (often called the Abrolhos Islands) is a chain of 122 islands and associated coral reefs in the Indian Ocean off the west coast of Australia about west of Geraldton, Western Australia. It is the southernmost true coral r ...

by Europeans was by Dutch VOC ships ''Dordrecht'' and ''Amsterdam'' in 1619, three years after Hartog made the first authenticated sighting of what is now Western Australia, 13 years after the first authenticated voyage to Australia, that of the ''Duyfke'' in 1606. Discovery of the islands was credited to Frederick de Houtman

Frederick de Houtman ( – 21 October 1627) was a Dutch explorer, navigator, and colonial governor who sailed on the first Dutch expedition to the East Indies from 1595 until 1597, during which time he made observations of the southern cel ...

, Captain-General of the ''Dordrecht'', as it was Houtman who later wrote of the discovery in a letter to Company directors.

Carstensz Glacier, Carstensz Pyramid/Puncak Jaya (1623)

The first person to spot Carstensz Pyramid

Puncak Jaya (; literally "Victorious Peak", Amungme: ''Nemangkawi Ninggok'') or Carstensz Pyramid (, , ) on the island of New Guinea, with an elevation of , is the highest mountain peak of an island on Earth, and the highest peak in Indones ...

(or Puncak Jaya

Puncak Jaya (; literally "Victorious Peak", Amungme: ''Nemangkawi Ninggok'') or Carstensz Pyramid (, , ) on the island of New Guinea, with an elevation of , is the highest mountain peak of an island on Earth, and the highest peak in Indones ...

) is reported to be the Dutch navigator and explorer Jan Carstensz

Jan Carstenszoon or more commonly Jan Carstensz In Dutch patronyms ending in -szoon were almost universally abbreviated to -sz was a 17th-century Dutch explorer. In 1623, Carstenszoon was commissioned by the Dutch East India Company to lead an ex ...

in 1623, for whom the mountain is named. Carstensz was the first non-native to sight the glaciers

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

on the peak of the mountain

A mountain is an elevated portion of the Earth's crust, generally with steep sides that show significant exposed bedrock. Although definitions vary, a mountain may differ from a plateau in having a limited summit area, and is usually higher t ...

on a rare clear day. The sighting went unverified for over two centuries, and Carstensz was ridiculed in Europe when he said he had seen snow

Snow consists of individual ice crystals that grow while suspended in the atmosphere—usually within clouds—and then fall, accumulating on the ground where they undergo further changes.

It consists of frozen crystalline water througho ...

and glacier

A glacier (; or ) is a persistent body of dense ice, a form of rock, that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires ...

s near the equator

The equator is the circle of latitude that divides Earth into the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Southern Hemisphere, Southern Hemispheres of Earth, hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about in circumferen ...

. The snowfield

A snow field, snowfield or neve is an accumulation of permanent snow and ice, typically found above the snow line, normally in mountainous and glacial terrain.

Glaciers originate in snowfields. The lower end of a glacier is usually free from ...

of Puncak Jaya was reached as early as 1909 by a Dutch explorer, Hendrik Albert Lorentz

Hendrikus Albertus Lorentz (18 September 1871 – 2 September 1944) was a Dutch explorer in New Guinea and diplomat in South Africa.

He was born to Theodorus Apolonius Ninus Lorentz, a tobacco grower in East Java who had returned to the ...

with six of his indigenous Dayak Kenyah porters recruited from the Apo Kayan

The Apo Kayan people are one of the Dayak people groups that are spread throughout Sarawak of Malaysia, North Kalimantan and East Kalimantan of Indonesia. The earliest Apo Kayan people are from the riverside of the Kayan River, Bulungan Regenc ...

in Borneo

Borneo () is the List of islands by area, third-largest island in the world, with an area of , and population of 23,053,723 (2020 national censuses). Situated at the geographic centre of Maritime Southeast Asia, it is one of the Greater Sunda ...

. The now highest Carstensz Pyramid summit was not climbed until 1962, by an expedition led by the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer

Heinrich Harrer (; 6 July 1912 – 7 January 2006) was an Austrian mountaineer, explorer, writer, sportsman, geographer, and briefly SS sergeant. He was a member of the four-man climbing team that made the first ascent of the North Face of the ...

with three other expedition members – the New Zealand mountaineer Philip Temple, the Australian rock climber Russell Kippax, and the Dutch patrol officer Albertus (Bert) Huizenga.

Gulf of Carpentaria (Northern Australia) (1623)

The first known European explorer to visit the region was Dutch Willem Janszoon

Willem Janszoon (; ) was a Dutch navigator and colonial governor. He served in the Dutch East Indies in the periods 1603–1611 and 1612–1616, including as governor of Fort Henricus on the island of Solor. During his voyage of 1605–1606 ...

(also known as ''Willem Jansz'') on his 1605–06 voyage. His fellow countryman, Jan Carstenszoon

Jan Carstenszoon or more commonly Jan Carstensz In Dutch patronyms ending in -szoon were almost universally abbreviated to -sz was a 17th-century Dutch explorer. In 1623, Carstenszoon was commissioned by the Dutch East India Company to lead an e ...

(also known as ''Jan Carstensz''), visited in 1623 and named the gulf in honour of Pieter de Carpentier

Pieter de Carpentier (19 February 1586 – 5 September 1659) was a Dutch administrator of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) who served as Governor-General there from 1623 to 1627. The Gulf of Carpentaria in northern Australia is named after him. ...

, at that time the governor-general of Dutch East Indies. Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch sea explorer, seafarer and exploration, explorer, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first European to reach New ...

explored the coast in 1644.

Staaten River (Cape York Peninsula, Northern Australia) (1623)

The Staaten River is a river in the Cape York Peninsula

The Cape York Peninsula is a peninsula located in Far North Queensland, Australia. It is the largest wilderness in northern Australia.Mittermeier, R.E. et al. (2002). Wilderness: Earth's last wild places. Mexico City: Agrupación Sierra Madre, ...

, Australia that rises more than to the west of Cairns

Cairns (; ) is a city in the Cairns Region, Queensland, Australia, on the tropical north east coast of Far North Queensland. In the , Cairns had a population of 153,181 people.

The city was founded in 1876 and named after William Cairns, Sir W ...

and empties into the Gulf of Carpentaria

The Gulf of Carpentaria is a sea off the northern coast of Australia. It is enclosed on three sides by northern Australia and bounded on the north by the eastern Arafura Sea, which separates Australia and New Guinea. The northern boundary ...

. The river was first named by Carstenszoon in 1623.

Arnhem Land and Groote Eylandt (Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Australia) (1623)

In 1623 Dutch East India Company captain Willem van Colster sailed into the Gulf of Carpentaria. Cape Arnhem is named after his ship, the ''Arnhem'', which itself was named after the city of Arnhem

Arnhem ( ; ; Central Dutch dialects, Ernems: ''Èrnem'') is a Cities of the Netherlands, city and List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands, near the German border. It is the capita ...

.

Groote Eylandt

Groote Eylandt ( Anindilyakwa: ''Ayangkidarrba''; meaning "island" ) is the largest island in the Gulf of Carpentaria and the fourth largest island in Australia. It was named by the explorer Abel Tasman in 1644 and is Dutch for "large island" ...

was first sighted the ''Arnhem''. Only in 1644, when Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch sea explorer, seafarer and exploration, explorer, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first European to reach New ...

arrived, was the island given a European name, Dutch for "Great Island" in an archaic spelling. The modern Dutch spelling is ''Groot Eiland''.

Hermite Islands (1624)

In February 1624, Dutch admiral Jacques l'Hermite discovered the Hermite Islands

__NOTOC__

The Hermite Islands () are the islands ''Hermite'', ''Herschel'', ''Deceit'' and ''Hornos'' as well as the islets ''Maxwell'', ''Jerdán'', ''Arrecife'', ''Chanticleer'', ''Hall'', ''Deceit (islet)'', and ''Hasse'' at almost the southe ...

at Cape Horn.

Southern Australia coast (1627)

In 1627, Dutch explorers François Thijssen

François Thijssen or Frans Thijsz (died 13 October 1638?) was a Dutch- French explorer who explored the southern coast of Australia.

He was the captain of the ship t Gulden Zeepaerdt'' (''The Golden Seahorse'') when sailing from Cape of Good ...

and Pieter Nuyts

Pieter Nuyts or Nuijts (159811 December 1655) was a Dutch Exploration, explorer, diplomat and politician.

He was part of a landmark expedition of the Dutch East India Company in 1626–1627 which mapped the southern coast of Australia. He bec ...

discovered the south coast of Australia and charted about of it between Cape Leeuwin

Cape Leeuwin is the most south-westerly (but not most southerly) mainland point of the Australian continent, in the state of Western Australia.

Description

A few small islands and rocks, the St Alouarn Islands, extend further in Flinders ...

and the Nuyts Archipelago

The Nuyts Archipelago is an island group in South Australia in the Great Australian Bight, to the south of the town of Ceduna on the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula. It consists of mostly granitic islands and reefs that provide breedin ...

.[Garden 1977, p.8.] François Thijssen

François Thijssen or Frans Thijsz (died 13 October 1638?) was a Dutch- French explorer who explored the southern coast of Australia.

He was the captain of the ship t Gulden Zeepaerdt'' (''The Golden Seahorse'') when sailing from Cape of Good ...

, captain of the ship '''t Gulden Zeepaert

() was a ship belonging to the Dutch East India Company. It sailed along the south coast of Australia from Cape Leeuwin in Western Australia to the Nuyts Archipelago in South Australia early in 1627.

The captain was François Thijssen.

Det ...

'' (The Golden Seahorse), sailed to the east as far as Ceduna in South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

. The first known ship to have visited the area is the ''Leeuwin'' ("Lioness"), a Dutch vessel that charted some of the nearby coastline in 1622. The log of the ''Leeuwin'' has been lost, so very little is known of the voyage. However, the land discovered by the ''Leeuwin'' was recorded on a 1627 map by Hessel Gerritsz

Hessel Gerritsz (buried 4 September 1632) was a Dutch engraver, cartographer, and publisher. A notable figure in the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography, despite strong competition Gerritsz is considered by some "unquestionably the chief ...

: Caert van't Landt van d'Eendracht

() is a 1627 map by Hessel Gerritsz. One of the earliest maps of Australia, it shows what little was then known of the west coast, based on a number of voyages beginning with the 1616 voyage of Dirk Hartog, when he named Eendrachtsland after hi ...

("Chart of the Land of Eendracht"), which appears to show the coast between present-day Hamelin Bay

Hamelin Bay is a bay and a locality on the southwest coast of Western Australia between Cape Leeuwin and Cape Naturaliste. It is named after French explorer Jacques Félix Emmanuel Hamelin, who sailed through the area in about 1801. It is ...

and Point D’Entrecasteaux. Part of Thijssen's map shows the islands St Francis and St Peter, now known collectively with their respective groups as the Nuyts Archipelago

The Nuyts Archipelago is an island group in South Australia in the Great Australian Bight, to the south of the town of Ceduna on the west coast of the Eyre Peninsula. It consists of mostly granitic islands and reefs that provide breedin ...

. Thijssen's observations were included as soon as 1628 by the VOC cartographer Hessel Gerritsz

Hessel Gerritsz (buried 4 September 1632) was a Dutch engraver, cartographer, and publisher. A notable figure in the Golden Age of Netherlandish cartography, despite strong competition Gerritsz is considered by some "unquestionably the chief ...

in a chart of the Indies and New Holland. This voyage defined most of the southern coast of Australia and discouraged the notion that "New Holland", as it was then known, was linked to Antarctica.

St Francis Island

St Francis Island (originally in Dutch: ''Eyland St. François'') is an island on the south coast of South Australia near Ceduna. It is part of the Nuyts Archipelago. It was one of the first parts of South Australia to be discovered and nam ...

(originally in Dutch: ''Eyland St. François'') is an island on the south coast of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

near Ceduna. It is now part of the Nuyts Archipelago Wilderness Protection Area

Nuyts Archipelago Wilderness Protection Area is a protected area in the Australian state of South Australia located in the Nuyts Archipelago off the west coast of Eyre Peninsula within to south-west of Ceduna.

The wilderness protection a ...

. It was one of the first parts of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

to be discovered and named by Europeans, along with St Peter Island. Thijssen named it after his patron saint, St. Francis.

St Peter Island is an island on the south coast of South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

near Ceduna to the south of Denial Bay

Denial Bay (formerly McKenzie) is a town and an associated locality in the Australian state of South Australia located on the state's west coast about north-west of the state capital of Adelaide and about west of the municipal seat of Ceduna. ...

. It is the second largest island in South Australia at about 13 km long. It was named in 1627 by Thijssen after Pieter Nuyts

Pieter Nuyts or Nuijts (159811 December 1655) was a Dutch Exploration, explorer, diplomat and politician.

He was part of a landmark expedition of the Dutch East India Company in 1626–1627 which mapped the southern coast of Australia. He bec ...

' patron saint.

Western Australia (1629)

The Weibbe Hayes Stone Fort, remnants of improvised

The Weibbe Hayes Stone Fort, remnants of improvised defensive wall

A defensive wall is a fortification usually used to protect a city, town or other settlement from potential aggressors. The walls can range from simple palisades or earthworks to extensive military fortifications such as curtain walls with t ...

s and stone shelters built by Wiebbe Hayes

Wiebbe Hayes (born ) was a Dutch soldier known for his leading role in the suppression of Jeronimus Cornelisz's massacre of shipwreck survivors in 1629, after the merchant ship was wrecked in the Houtman Abrolhos, a chain of coral islands off ...

and his men on the West Wallabi Island

West Wallabi Island is an island in the Wallabi Group of the Houtman Abrolhos, in the Indian Ocean off the west coast of mainland Australia.

History

West Wallabi Island was important in the story of the '' Batavia'' shipwreck and massacre. F ...

, are Australia's oldest known European structures, more than 150 years before expeditions to the Australian continent by James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

and Arthur Phillip

Arthur Phillip (11 October 1738 – 31 August 1814) was a British Royal Navy officer who served as the first Governor of New South Wales, governor of the Colony of New South Wales.

Phillip was educated at Royal Hospital School, Gree ...

.

Tasmania and the surrounding islands (1642)

In 1642,

In 1642, Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch sea explorer, seafarer and exploration, explorer, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first European to reach New ...

sailed from Mauritius

Mauritius, officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island country in the Indian Ocean, about off the southeastern coast of East Africa, east of Madagascar. It includes the main island (also called Mauritius), as well as Rodrigues, Ag ...

and on 24 November, sighted Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

. He named Tasmania Van Diemen's Land

Van Diemen's Land was the colonial name of the island of Tasmania during the European exploration of Australia, European exploration and colonisation of Australia in the 19th century. The Aboriginal Tasmanians, Aboriginal-inhabited island wa ...

, after Anthony van Diemen

Anthony van Diemen (also ''Antonie'', ''Antonio'', ''Anton'', ''Antonius''; 1593 – 19 April 1645) was a Dutch colonial governor.

Early life

Van Diemen was born in Culemborg (now in the Netherlands, then in a county in the Holy Roman Empire) ...

, the Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

's governor-general, who had commissioned his voyage. It was officially renamed Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

in honour of its first European discoverer on 1 January 1856.

Maatsuyker Islands, a group of small islands that are the southernmost point of the Australian continent

The continent of Australia, sometimes known in technical contexts as Sahul (), Australia-New Guinea, Australinea, or Meganesia to distinguish it from the country of Australia, is located within the Southern and Eastern hemispheres, near t ...

. were discovered and named by Tasman in 1642 after a Dutch official. The main islands of the group are De Witt Island

De Witt Island, also known as Big Witch, is an island located close to the south-western coast of Tasmania, Australia. The island is the largest of the Maatsuyker Islands Group, and comprises part of the Southwest National Park and the Tasma ...

(354 m), Maatsuyker Island

Maatsuyker Island is an island located close to the south coast of Tasmania, Australia. The island is part of the Maatsuyker Islands Group, and comprises part of the Southwest National Park and the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Site. ...

(296 m), Flat Witch Island, Flat Top Island, Round Top Island, Walker Island, Needle Rocks

The Needle Rocks, also known as the Needles, are a group of five main islet, rock islets located close to the South West Tasmania, south-western coast of Tasmania, Australia. With a combined area of approximately , the islets are part of the Ma ...

and Mewstone

Mewstone is an unpopulated island, composed of muscovite granite, located close to the south coast of Tasmania, Australia. The island has steep cliffs and a small flat summit and is part of the Pedra Branca group, lying southeast of Maatsuyk ...

.

Maria Island

Maria Island or wukaluwikiwayna in palawa kani is a mountainous island located in the Tasman Sea, off the east coast of Tasmania, Australia. The island is entirely occupied by the Maria Island National Park, which includes a marine area of o ...

was discovered and named in 1642 by Tasman after Maria van Diemen (née van Aelst), wife of Anthony. The island was known as ''Maria's Isle'' in the early 19th century.

Tasman's journal entry for 29 November 1642 records that he observed a rock which was similar to a rock named Pedra Branca off China, presumably referring to the Pedra Branca in the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by South China, in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan island, Taiwan and northwestern Philippines (mainly Luz ...

.

Schouten Island

Schouten Island (formerly Schouten's Isle), part of the Schouten Island Group, is an island with an area of approximately lying close to the eastern coast of Tasmania, Australia, located south of the Freycinet Peninsula and is a part of Frey ...

is a island in eastern Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, Australia. It lies 1.6 kilometres south of Freycinet Peninsula

The Freycinet Peninsula is a large peninsula located on the eastern coast of Tasmania, Australia. The peninsula is located north of Schouten Island and is contained within the Freycinet National Park.

The locality of Freycinet is in the local g ...

and is a part of Freycinet National Park

Freycinet National Park is a national park on the east coast of Tasmania, Australia, northeast of Hobart. It occupies a large part of the Freycinet Peninsula, named after French navigator Louis de Freycinet, and Schouten Island. Founded in 1916 ...

. In 1642, while surveying the south-west coast of Tasmania, Tasman named the island after Joost Schouten, a member of the Council of the Dutch East India Company.

Tasman also reached Storm Bay

The Storm Bay is a large bay in the south-east region of Tasmania, Australia.

The bay is the river mouth to the Derwent River estuary and serves as the main port of Hobart, the capital city of Tasmania.

The bay is bordered by Bruny Island to ...

, a large bay

A bay is a recessed, coastal body of water that directly connects to a larger main body of water, such as an ocean, a lake, or another bay. A large bay is usually called a ''gulf'', ''sea'', ''sound'', or ''bight''. A ''cove'' is a small, ci ...

in the south-east of Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

, Australia. It is the entrance to the Derwent River estuary

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime enviro ...

and the port of Hobart

Hobart ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the island state of Tasmania, Australia. Located in Tasmania's south-east on the estuary of the River Derwent, it is the southernmost capital city in Australia. Despite containing nearly hal ...

, the capital city of Tasmania

Tasmania (; palawa kani: ''Lutruwita'') is an island States and territories of Australia, state of Australia. It is located to the south of the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland, and is separated from it by the Bass Strait. The sta ...

. It is bordered by Bruny Island

Bruny Island is a coastal island of Tasmania, Australia, located at the mouths of the Derwent River and Huon River estuaries on Storm Bay on the Tasman Sea, south of Hobart. The island is separated from the mainland by the D'Entrecasteaux C ...

to the west and the Tasman Peninsula

The Tasman Peninsula, officially Turrakana / Tasman Peninsula, is a peninsula located in south-east Tasmania, Australia, approximately by the Arthur Highway, south-east of Hobart.

The Tasman Peninsula lies south and west of Forestier Peninsu ...

to the east.

New Zealand and Fiji (1642)

In 1642, the first Europeans known to reach

In 1642, the first Europeans known to reach New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

were the crew of Dutch explorer Abel Tasman

Abel Janszoon Tasman (; 160310 October 1659) was a Dutch sea explorer, seafarer and exploration, explorer, best known for his voyages of 1642 and 1644 in the service of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). He was the first European to reach New ...

who arrived in his ships ''Heemskerck'' and ''Zeehaen''. Tasman anchored at the northern end of the South Island

The South Island ( , 'the waters of Pounamu, Greenstone') is the largest of the three major islands of New Zealand by surface area, the others being the smaller but more populous North Island and Stewart Island. It is bordered to the north by ...

in Golden Bay Golden Bay may refer to:

* Golden Bay / Mohua

Golden Bay / Mohua is a large shallow bay in New Zealand's Tasman District, near the northern tip of the South Island. An arm of the Tasman Sea, the bay lies northwest of Tasman Bay / Te Tai-o-Aore ...

(he named it Murderers' Bay) in December 1642 and sailed northward to Tonga

Tonga, officially the Kingdom of Tonga, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania. The country has 171 islands, of which 45 are inhabited. Its total surface area is about , scattered over in the southern Pacific Ocean. accordin ...

following a clash with local Māori. Tasman sketched sections of the two main islands' west coasts. Tasman called them ''Staten Landt'', after the ''States General of the Netherlands

The States General of the Netherlands ( ) is the Parliamentary sovereignty, supreme Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of the Netherlands consisting of the Senate (Netherlands), Senate () and the House of Representatives (Netherlands), House of R ...

'', and that name appeared on his first maps of the country. In 1645 Dutch cartographers changed the name to '' Nova Zeelandia'' in Latin, from ''Nieuw Zeeland'', after the Dutch province of ''Zeeland

Zeeland (; ), historically known in English by the Endonym and exonym, exonym Zealand, is the westernmost and least populous province of the Netherlands. The province, located in the southwest of the country, borders North Brabant to the east ...

''. It was subsequently Anglicised as ''New Zealand'' by British naval captain James Cook

Captain (Royal Navy), Captain James Cook (7 November 1728 – 14 February 1779) was a British Royal Navy officer, explorer, and cartographer famous for his three voyages of exploration to the Pacific and Southern Oceans, conducted between 176 ...

Various claims have been made that New Zealand was reached by other non-Polynesian voyagers before Tasman, but these are not widely accepted. Peter Trickett, for example, argues in '' Beyond Capricorn'' that the Portuguese explorer Cristóvão de Mendonça

Cristóvão de Mendonça ( Mourão, 1475 – Ormus, 1532) was a Portuguese noble and explorer who was active in South East Asia in the 16th century.

Mendonça in João de Barros's Décadas da Ásia

Mendonça is known from a small number of Por ...

reached New Zealand in the 1520s, and the Tamil bell discovered by missionary

A missionary is a member of a Religious denomination, religious group who is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thoma ...

William Colenso

William Colenso (17 November 1811 – 10 February 1899) FRS was a Cornish Christian missionary to New Zealand, and also a printer, botanist, explorer and politician. He attended the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and later wrote an acco ...

has given rise to a number of theories,Fiji

Fiji, officially the Republic of Fiji, is an island country in Melanesia, part of Oceania in the South Pacific Ocean. It lies about north-northeast of New Zealand. Fiji consists of an archipelago of more than 330 islands—of which about ...

.

Tongatapu and Haʻapai (Tonga) (1643)

Tasman discovered Tongatapu

Tongatapu is the main island of Tonga and the site of its capital, Nukuʻalofa, Nukualofa. It is located in Tonga's southern island group, to which it gives its name, and is the country's most populous island, with 74,611 residents (2016), 70.5% o ...

and Haʻapai

Haʻapai is a group of islands, islets, reefs, and shoals in the central part of Tonga. It has a combined land area of . The Tongatapu island group lies to its south, and the Vavaʻu group lies to its north. Seventeen of the Haʻapai islands are ...

in 1643 commanding two ships, the ''Heemskerck'' and the ''Zeehaen'' commissioned by the Dutch East India Company. The expedition's goals were to chart the unknown southern and eastern seas and to find a possible passage through the South Pacific and Indian Ocean providing a faster route to Chile.

Sakhalin (Cape Patience) (1643)

The first European known to visit Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. An islan ...

was Martin Gerritz de Vries, who mapped Cape Patience

Cape Patience (, ''Poluostrov Terpeniya'') is a peninsula protruding km of east-central Sakhalin Island into the Sea of Okhotsk. It forms the eastern boundary of the Gulf of Patience. The width of the peninsula varies from less than , at the L ...

and Cape Aniva on the island's east coast in 1643.

Kuril Islands (1643)

In the summer of 1643, the under Martin Gerritz de Vries explored the waters north of Japan. They are sometimes credited with the discovery of various parts of the

In the summer of 1643, the under Martin Gerritz de Vries explored the waters north of Japan. They are sometimes credited with the discovery of various parts of the Kuril Islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands are a volcanic archipelago administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the Russian Far East. The islands stretch approximately northeast from Hokkaido in Japan to Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, separating the ...

but in fact recorded exaggerated nonsense or phantom island

A phantom island is a purported island which was included on maps for a period of time, but was later found not to exist. They usually originate from the reports of early sailors exploring new regions, and are commonly the result of navigati ...

s. The Company Land

Urup (; , ) is an uninhabited volcanic island in the Kuril Islands chain in the south of the Sea of Okhotsk, northwest Pacific Ocean. Its name is derived from the Ainu language word ''urup'', meaning "sockeye salmon".

Geography and climate

U ...

named for the VOC

VOC, VoC or voc may refer to:

Science and technology

* Open-circuit voltage (VOC), the voltage between two terminals when there is no external load connected

* Variant of concern, a category used during the assessment of a new variant of a virus

* ...

is sometimes presented as Urup

Urup (; , ) is an uninhabited volcanic island in the Kuril Islands chain in the south of the Sea of Okhotsk, northwest Pacific Ocean. Its name is derived from the Ainu language word ''urup'', meaning "sockeye salmon".

Geography and climate

U ...

but was actually describing an enormous nonexistent extension of Asia or North America that filled European maps for the next century until well after Martin Spanberg

Martin Spanberg (; died 1761) was a Danish-born Russian naval officer who took part with his compatriot Vitus Bering in both Kamchatka expeditions as second in command. He is best known for finding a sea route to Japan from Russian territory an ...

proved its nonexistence. Similarly, Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is the southernmost of the boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County and situated at the southernmost point of New York (state), New York. The borough is separated from the ad ...

named for the States Generalis sometimes connected to Iturup

Iturup (; ), also historically known by #Names, other names, is an island in the Kuril Archipelago separating the Sea of Okhotsk from the North Pacific Ocean. The town of Kurilsk, administrative center of Kurilsky District, is located roughly mi ...

but was actually described as a large and prosperous island similar to Japan.

Having long occupied maps, Vries Strait

Vries Strait (, ''Proliv Friza''), historically also known as the De Vries Strait, is a strait between two main islands of the Kurils. It is located between the northeastern end of the island of Iturup and the southwestern headland of Urup Islan ...

the supposed division between these imaginary placessurvived as the name for the strait separating Urup and Iturup, a main division within the Kurils. Similarly, Cape Patience

Cape Patience (, ''Poluostrov Terpeniya'') is a peninsula protruding km of east-central Sakhalin Island into the Sea of Okhotsk. It forms the eastern boundary of the Gulf of Patience. The width of the peninsula varies from less than , at the L ...

and the Gulf of Patience

Gulf of Patience is a large body of water off the southeastern coast of Sakhalin, Russia.

Geography

The Gulf of Patience is located in the southern Sea of Okhotsk, between the main body of Sakhalin Island in the west and Cape Patience in the e ...

southeast of Sakhalin in the Sea of Okhotsk preserves the legacy of the sailors on the who had to wait out thick fog when they first entered the area.

Rottnest Island and Swan River (1696)

The first Europeans known to land on the Rottnest Island

Rottnest Island (), often colloquially referred to as "Rotto", is a Islands of Perth, Western Australia, island off the coast of Western Australia, located west of Fremantle. A sandy, low-lying island formed on a base of aeolianite limestone, ...

were 13 Dutch sailors including Abraham Leeman from the ''Waeckende Boey'' who landed near Bathurst Point on 19 March 1658 while their ship was nearby. The ship had sailed from Batavia in search of survivors of the missing ''Vergulde Draeck

''Vergulde Draeck'' (), also spelled ''Vergulde Draak'' and ''Vergulde Draek'' (meaning ''Gilt Dragon''), was a , ship constructed in 1653 by the Dutch East India Company (, commonly abbreviated to VOC). The ship was lost off the coast of West ...

'' which was later found wrecked north near present-day Ledge Point

Ledge or Ledges may refer to:

* Ridge, a geological feature

* Reef, an underwater feature

* Stratum, a layer of rock

* Ledge, in civil engineering, a type of earthmoving cut

* Slang for legend

A legend is a genre of folklore that consists of ...

. The island was given the name "Rotte nest" (meaning "rat nest" in the 17th century Dutch language) by Dutch captain Willem de Vlamingh

Willem Hesselsz de Vlamingh (baptized 28 November 1640 – after 7 August 1702) was a Dutch sea captain who explored the central west coast of New Holland (Australia) in the late 17th century, where he landed in what is now Perth on the Swan ...

who spent six days exploring the island from 29 December 1696, mistaking the quokka

The quokka (; ''Setonix brachyurus'') is a small macropod about the size of a domestic cat. It is the only member of the genus ''Setonix''. Like other marsupials in the macropod family (such as kangaroos and wallabies), the quokka is herbiv ...

s for giant rat

Rats are various medium-sized, long-tailed rodents. Species of rats are found throughout the order Rodentia, but stereotypical rats are found in the genus ''Rattus''. Other rat genera include '' Neotoma'' (pack rats), '' Bandicota'' (bandicoo ...

s. De Vlamingh led a fleet of three ships, ''De Geelvink'', ''De Nijptang'' and ''Weseltje'' and anchored on the northern side of the island, near The Basin.

On 10 January 1697, de Vlamingh ventured up the Swan River. He and his crew are believed to have been the first Europeans to do so. He named the '' Swan River'' (''Zwaanenrivier'' in Dutch) after the large numbers of black swan

The black swan (''Cygnus atratus'') is a large Anatidae, waterbird, a species of swan which breeds mainly in the southeast and southwest regions of Australia. Within Australia, the black swan is nomadic, with erratic migration patterns dependent ...

s that he observed there.

Easter Island and Samoa (1722)

On Easter Sunday, 5 April 1722, Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen

Jacob Roggeveen (1 February 1659 – 31 January 1729) was a Dutch explorer who was sent to find Terra Australis and Davis Land, but instead found Easter Island (called so because he landed there on Easter Sunday). Jacob Roggeveen also found Bor ...

discovered Easter Island. Easter Island

Easter Island (, ; , ) is an island and special territory of Chile in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, at the southeasternmost point of the Polynesian Triangle in Oceania. The island is renowned for its nearly 1,000 extant monumental statues, ...

is one of the most remote inhabited islands in the world. The nearest inhabited land (50 residents) is Pitcairn Island

Pitcairn Island is the only inhabited island of the Pitcairn Islands, in the southern Pacific Ocean, of which many inhabitants are descendants of mutineers of HMS ''Bounty''.

Geography

The island is of volcanic origin, with a rugged cliff ...

away, the nearest town with a population over 500 is Rikitea

Rikitea is a small town on Mangareva, which is part of the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia. A majority of the islanders live in Rikitea. The island was a protectorate of France in 1871 and was annexed in 1881.

History

The town's history dates ...

on island Mangareva

Mangareva is the central and largest island of the Gambier Islands in French Polynesia. It is surrounded by smaller islands: Taravai in the southwest, Aukena and Akamaru in the southeast, and islands in the north. Mangareva has a permanent p ...

away, and the nearest continental point lies in central Chile, away.

The name "Easter Island" was given by the island's first recorded European visitor, the Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

explorer Jacob Roggeveen

Jacob Roggeveen (1 February 1659 – 31 January 1729) was a Dutch explorer who was sent to find Terra Australis and Davis Land, but instead found Easter Island (called so because he landed there on Easter Sunday). Jacob Roggeveen also found Bor ...

, who encountered it on Easter Sunday

Easter, also called Pascha (Aramaic: פַּסְחָא , ''paskha''; Greek language, Greek: πάσχα, ''páskha'') or Resurrection Sunday, is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, de ...

(5 April"Calculate the Date of Easter Sunday

, Astronomical Society of South Australia. Retrieved 7 February 2013.) 1722, while searching for

Davis or David's island. Roggeveen named it ''Paasch-Eyland'' (18th century

Dutch

Dutch or Nederlands commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

** Dutch people as an ethnic group ()

** Dutch nationality law, history and regulations of Dutch citizenship ()

** Dutch language ()

* In specific terms, i ...

for "Easter Island").

[An English translation of the originally Dutch journal by Jacob Roggeveen, with additional significant information from the log by Cornelis Bouwman, was published in: Andrew Sharp (ed.), The Journal of Jacob Roggeveen (Oxford 1970).] The island's official Spanish name, ''Isla de Pascua'', also means "Easter Island".

On 13 June Roggeveen discovered the islands of

Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa and known until 1997 as Western Samoa, is an island country in Polynesia, part of Oceania, in the South Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu), two smaller, inhabited ...

.

Orange River (1779)

The Orange River was named by

Colonel Robert Gordon, commander of the Dutch East India Company garrison at

Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, on a trip to the interior in 1779.

References

External links

Daily Dutch Innovation

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dutch Explorations

Explorations

Dutch exploration in the Age of Discovery

Expeditions from the Netherlands

List of Dutch Explorations

The following list is composed of (largely) unknown lands that were discovered by people from the Netherlands, or being the first documented Europeans to discover certain areas.

Explorations Orange Islands (1594)

During his first journe ...

Lists of expeditions

The first undisputed discovery of the archipelago was an expedition led by the Dutch mariner

The first undisputed discovery of the archipelago was an expedition led by the Dutch mariner  The Dutch ship,

The Dutch ship,  The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'', which could mean either "hell's hole" or "bright gate/passage". It was originally applied to the entirety of the

The name "Hell Gate" is a corruption of Dutch phrase ''Hellegat'', which could mean either "hell's hole" or "bright gate/passage". It was originally applied to the entirety of the  On 29 January 1616, they sighted land they called

On 29 January 1616, they sighted land they called  They discovered

They discovered

In 1642, the first Europeans known to reach

In 1642, the first Europeans known to reach  In the summer of 1643, the under Martin Gerritz de Vries explored the waters north of Japan. They are sometimes credited with the discovery of various parts of the

In the summer of 1643, the under Martin Gerritz de Vries explored the waters north of Japan. They are sometimes credited with the discovery of various parts of the