Tzav, Tsav, Zav, Sav, or Ṣaw (—

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

for "command," the sixth word, and the first distinctive word, in the parashah) is the 25th

weekly Torah portion

The weekly Torah portion refers to a lectionary custom in Judaism in which a portion of the Torah (or Pentateuch) is read during Jewish prayer services on Monday, Thursday, and Saturday. The full name, ''Parashat HaShavua'' (), is popularly abbre ...

(, ''parashah'') in the annual

Jewish

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

cycle of

Torah reading

Torah reading (; ') is a Jewish religious tradition that involves the public reading of a set of passages from a Torah scroll. The term often refers to the entire ceremony of removing the scroll (or scrolls) from the Torah ark, chanting the ap ...

and the second in the

Book of Leviticus

The Book of Leviticus (, from , ; , , 'And He called'; ) is the third book of the Torah (the Pentateuch) and of the Old Testament, also known as the Third Book of Moses. Many hypotheses presented by scholars as to its origins agree that it de ...

. The parashah teaches how the

priests

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in particular, ...

performed the

sacrifices

Sacrifice is an act or offering made to a deity. A sacrifice can serve as propitiation, or a sacrifice can be an offering of praise and thanksgiving.

Evidence of ritual animal sacrifice has been seen at least since ancient Hebrews and Greeks ...

and describes the ordination of

Aaron

According to the Old Testament of the Bible, Aaron ( or ) was an Israelite prophet, a high priest, and the elder brother of Moses. Information about Aaron comes exclusively from religious texts, such as the Hebrew Bible, the New Testament ...

and his sons. The parashah constitutes Leviticus 6:1–8:36. The parashah is made up of 5,096 Hebrew letters, 1,353 Hebrew words, 97

verses, and 170 lines in a Torah scroll (, ''

Sefer Torah

file:SeferTorah.jpg, A Sephardic Torah scroll rolled to the first paragraph of the Shema

file:Köln-Tora-und-Innenansicht-Synagoge-Glockengasse-040.JPG, An Ashkenazi Torah scroll rolled to the Decalogue

file:Keneseth Eliyahoo Synagogue, Inte ...

'').

Jew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

s read it the 24th or 25th

Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, Ten Commandments, commanded by God to be kept as a Holid ...

after

Simchat Torah

Simchat Torah (; Ashkenazi: ), also spelled Simhat Torah, is a Jewish holiday that celebrates and marks the conclusion of the annual cycle of public Torah readings, and the beginning of a new cycle. Simchat Torah is a component of the Hebrew Bible ...

, generally in the second half of March or the first half of April.

Readings

In traditional Shabbat Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings called ''

aliyot'' ().

First reading—Leviticus 6:1–11

In the first reading,

God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

told

Moses

In Abrahamic religions, Moses was the Hebrews, Hebrew prophet who led the Israelites out of slavery in the The Exodus, Exodus from ancient Egypt, Egypt. He is considered the most important Prophets in Judaism, prophet in Judaism and Samaritani ...

to command Aaron and the priests about the rituals of the sacrifices (, ''qārbānoṯ'').

The

burnt offering

A holocaust is a religious animal sacrifice that is completely consumed by fire, also known as a burnt offering. The word derives from the ancient Greek ''holokaustos'', the form of sacrifice in which the victim was reduced to ash, as distingui ...

(, ''ʿolā'') was to burn on the

altar

An altar is a table or platform for the presentation of religion, religious offerings, for sacrifices, or for other ritualistic purposes. Altars are found at shrines, temples, Church (building), churches, and other places of worship. They are use ...

until morning, when the priest was to clear the ashes to a place outside the camp. The priests were to keep the

fire

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a fuel in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction Product (chemistry), products.

Flames, the most visible portion of the fire, are produced in the combustion re ...

burning, every morning feeding it

wood

Wood is a structural tissue/material found as xylem in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulosic fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin t ...

.

The

gift offering

A meal offering, grain offering, or gift offering (, ), is a type of Biblical sacrifice, specifically a sacrifice that did not include sacrificial animals. In older English it is sometimes called an oblation, from Latin.

The Hebrew noun () is ...

(, ''minḥā'') was to be presented before the altar, a handful of it burned on the altar, and the balance eaten by the priests as

unleavened cakes in the Tent of Meeting.

Second reading—Leviticus 6:12–7:10

In the second reading, on the occasion of the

High Priest's anointment, the meal offering was to be prepared with oil on a griddle and then entirely burned on the altar.

The

sin offering

A sin offering (, ''korban ḥatat'', , lit: "purification offering") is a sacrificial offering described and commanded in the Torah (Lev. 4.1-35); it could be fine flour or a proper animal.Leviticus 5:11 A sin offering also occurs in 2 Chronicl ...

(, ''ḥaṭoṯ'') was to be slaughtered at the same place as the burnt offering, and the priest who offered it was to eat it in the Tent of Meeting. If the sin offering was cooked in an earthen vessel, that vessel was to be broken afterward. A copper vessel could be rinsed with water and reused. If

blood

Blood is a body fluid in the circulatory system of humans and other vertebrates that delivers necessary substances such as nutrients and oxygen to the cells, and transports metabolic waste products away from those same cells.

Blood is com ...

of the sin offering was brought into the

Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle (), also known as the Tent of the Congregation (, also Tent of Meeting), was the portable earthly dwelling of God used by the Israelites from the Exodus until the conquest of Canaan. Moses was instru ...

for expiation, the entire offering was to be burned on the altar.

[.]

The

guilt offering

A guilt offering (; plural ), also referred to as a trespass offering (KJV, 1611), was a type of Biblical sacrifice, specifically a sacrifice made as a compensation payment for unintentional and certain intentional transgressions. It was distinct ...

(, ''āšām'') was to be slaughtered at the same place as the burnt offering, the priest was to dash its blood on the altar, burn its

fat

In nutrition science, nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such chemical compound, compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

The term often refers specif ...

, broad tail,

kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s, and protuberance on the

liver

The liver is a major metabolic organ (anatomy), organ exclusively found in vertebrates, which performs many essential biological Function (biology), functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of var ...

on the altar, and the priest who offered it was to eat the balance of its meat in the Tent of Meeting.

The priest who offered a burnt offering kept the skin. The priest who offered it was to eat any baked or grilled meal offering, but every other meal offering was to be shared among all the priests.

Third reading—Leviticus 7:11–38

In the third reading, the

peace offering

The peace offering () was one of the sacrifices and offerings in the Hebrew Bible (Leviticus 3; 7.11–34). The term "peace offering" is generally constructed from "slaughter offering" and the plural of ( ), but is sometimes found without as ...

(, ''šəlāmim''), if offered for thanksgiving, was to be offered with unleavened cakes or wafers with oil, which would go to the priest, who would dash the blood of the peace offering upon the altar. All the meat of the peace offering had to be eaten on the day it was offered.

[.] If offered as a votive or a freewill offering, it could be eaten for two days, and what was then left on the third day was to be burned.

Meat that touched anything unclean could not be eaten; it had to be burned.

[.] Only an unclean person could not eat meat from peace offerings, with punishment for transgression being banishment from the community. One could eat no fat or blood, with transgression also leading to exile.

The person offering the peace offering had to present the offering and its fat himself; the priest would burn the fat on the altar, the breast would go to the priests, and the right thigh would go to the priest who offered the sacrifice.

Fourth reading—Leviticus 8:1–13

In the fourth reading, God instructed Moses to assemble the whole community at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting for the priests' ordination. Moses brought Aaron and his sons forward, washed them, and dressed Aaron in his vestments. Moses anointed and consecrated the

Tabernacle

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tabernacle (), also known as the Tent of the Congregation (, also Tent of Meeting), was the portable earthly dwelling of God used by the Israelites from the Exodus until the conquest of Canaan. Moses was instru ...

and all that was in it, and then anointed and consecrated Aaron and his sons.

Fifth reading—Leviticus 8:14–21

In the fifth reading, Moses led forward a

bull

A bull is an intact (i.e., not Castration, castrated) adult male of the species ''Bos taurus'' (cattle). More muscular and aggressive than the females of the same species (i.e. cows proper), bulls have long been an important symbol cattle in r ...

for a sin offering, Aaron and his sons laid their hands on the bull's head, and it was slaughtered. Moses put the bull's blood on the horns and the base of the altar, burned the fat, the protuberance of the liver, and the kidneys on the altar, and burned the rest of the bull outside the camp. Moses then brought forward a

ram

Ram, ram, or RAM most commonly refers to:

* A male sheep

* Random-access memory, computer memory

* Ram Trucks, US, since 2009

** List of vehicles named Dodge Ram, trucks and vans

** Ram Pickup, produced by Ram Trucks

Ram, ram, or RAM may also ref ...

for a burnt offering, Aaron and his sons laid their hands on the ram's head, and it was slaughtered. Moses dashed the blood against the altar and burned all of the rams on the altar.

Sixth reading—Leviticus 8:22–29

In the sixth reading, Moses then brought forward a second ram for ordination; Aaron and his sons laid their hands on the ram's head, and it was slaughtered. Moses put some of its blood on Aaron and his sons, on the ridges of their right ears, on the thumbs of their right hands, and on the big toes of their right feet. Moses then burned the animal's fat, broad tail, protuberance of the liver, kidneys, and right thigh on the altar with a cake of unleavened bread, a cake of oil bread, and a wafer as an ordination offering. Moses raised the breast before God and then took it as his portion.

Seventh reading—Leviticus 8:30–36

In the seventh reading, Moses sprinkled oil and blood on Aaron and his sons and their vestments. And Moses told Aaron and his sons to boil the meat at the entrance of the Tent of Meeting and eat it there, and remain at the Tent of Meeting for seven days to complete their ordination, and they did all the things that God had commanded through Moses.

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the

triennial cycle

The Triennial cycle of Torah reading may refer to either

* The historical practice in ancient Israel by which the entire Torah was read in serial fashion over a three-year period, or

* The practice adopted by many Reform, Conservative, Reconstruct ...

of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:

In inner-Biblical interpretation

This parashah and the preceding one (

Vayikra

The Book of Leviticus (, from , ; , , 'And He called'; ) is the third book of the Torah (the Pentateuch) and of the Old Testament, also known as the Third Book of Moses. Many hypotheses presented by scholars as to its origins agree that it de ...

) have parallels or are discussed in these Biblical sources:

Leviticus chapters 1–7

In

Psalm 50

Psalm 50, a Psalm of Asaph, is the 50th psalm from the Book of Psalms in the Bible, beginning in English in the King James Version: "The mighty God, even the LORD, hath spoken, and called the earth from the rising of the sun unto the going down ...

, God clarifies the purpose of sacrifices. God states that correct sacrifice was not the taking of a bull out of the sacrificer's house, nor the taking of a goat out of the sacrificer's fold, to convey to God, for every animal was already God's possession. The sacrificer was not to think of the sacrifice as food for God, for God neither feels hunger nor eats. Rather, the worshiper was to offer God the sacrifice of thanksgiving and call upon God in times of trouble, and thus God would deliver the worshiper, and the worshiper would honor God.

And Psalm 107 enumerates four occasions on which a thank-offering (, ''zivchei todah''), as described in Leviticus 7:12–15 (referring to a , ''zevach todah'') would be appropriate: (1) passage through the

desert

A desert is a landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions create unique biomes and ecosystems. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About one-third of the la ...

, (2) release from

prison

A prison, also known as a jail, gaol, penitentiary, detention center, correction center, correctional facility, or remand center, is a facility where Prisoner, people are Imprisonment, imprisoned under the authority of the State (polity), state ...

, (3) recovery from serious

disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

, and (4) surviving a

storm

A storm is any disturbed state of the natural environment or the atmosphere of an astronomical body. It may be marked by significant disruptions to normal conditions such as strong wind, tornadoes, hail, thunder and lightning (a thunderstor ...

at sea.

The

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

. '' Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

8:20 reports that

Noah

Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

offered burnt-offerings (, ''olot'') of every clean beast and bird on an altar after the waters of

the Flood subsided. The story of the

Binding of Isaac

The Binding of Isaac (), or simply "The Binding" (), is a story from Book of Genesis#Patriarchal age (chapters 12–50), chapter 22 of the Book of Genesis in the Hebrew Bible. In the biblical narrative, God in Abrahamic religions, God orders A ...

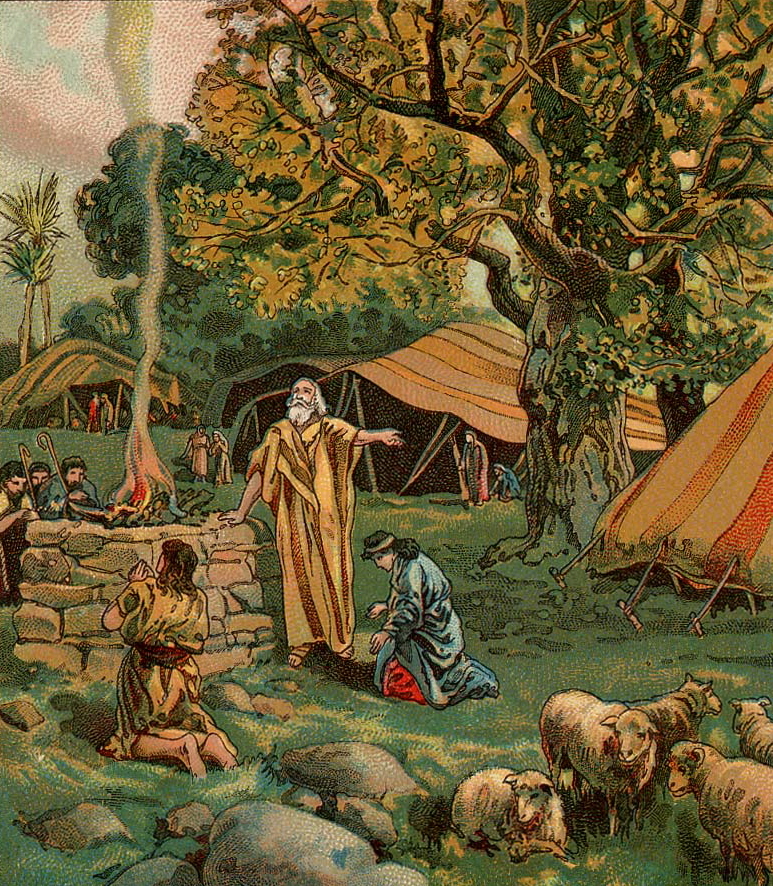

includes three references to the burnt offering (, ''olah''). In Genesis 22:2, God told

Abraham

Abraham (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew Patriarchs (Bible), patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father who began the Covenant (biblical), covenanta ...

to take

Isaac

Isaac ( ; ; ; ; ; ) is one of the three patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs of the Israelites and an important figure in the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith. Isaac first appears in the Torah, in wh ...

and offer him as a burnt-offering (, ''olah''). Genesis 22:3 then reports that Abraham rose early in the morning and split the wood for the burnt offering (, ''olah''). And after the

angel

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

of the Lord averted Isaac's sacrifice, Genesis 22:13 reports that Abraham lifted his eyes and saw a ram caught in a thicket, and Abraham then offered the ram as a burnt offering (, ''olah'') instead of his son.

Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

10:25 reports that Moses pressed

Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

for Pharaoh to give the Israelites "sacrifices and burnt offerings" (, ''zevachim v'olot'') to offer to God. And Exodus 18:12 reports that after

Jethro heard all that God did to Pharaoh and the

Egyptians

Egyptians (, ; , ; ) are an ethnic group native to the Nile, Nile Valley in Egypt. Egyptian identity is closely tied to Geography of Egypt, geography. The population is concentrated in the Nile Valley, a small strip of cultivable land stretchi ...

, Jethro offered a burnt offering and sacrifices (, ''olah uzevachim'') to God.

While Leviticus 2 and Leviticus 6:7–16 set out the procedure for the meal offering (, ''minchah''), before then, in Genesis 4:3,

Cain

Cain is a biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He was a farmer who gave an offering of his crops to God. How ...

brought an offering (, ''minchah'') of the fruit of the ground. And then Genesis 4:4–5 reports that God had respect for Abel and his offering (, ''minchato''), but for Cain and his offering (, ''minchato''), God had no respect.

And while

Numbers

A number is a mathematical object used to count, measure, and label. The most basic examples are the natural numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and so forth. Numbers can be represented in language with number words. More universally, individual numbers can ...

15:4–9 indicates that one bringing an animal sacrifice needed also to bring a drink offering (, ''nesech''), before then, in Genesis 35:14,

Jacob

Jacob, later known as Israel, is a Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions. He first appears in the Torah, where he is described in the Book of Genesis as a son of Isaac and Rebecca. Accordingly, alongside his older fraternal twin brother E ...

poured out a drink offering (, ''nesech'') at

Bethel

Bethel (, "House of El" or "House of God",Bleeker and Widegren, 1988, p. 257. also transliterated ''Beth El'', ''Beth-El'', ''Beit El''; ; ) was an ancient Israelite city and sacred space that is frequently mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

Bet ...

.

More generally, the Hebrew Bible addressed "sacrifices" (, ''zevachim'') generically in connection with Jacob and Moses. After Jacob and

Laban reconciled, Genesis 31:54 reports that Jacob offered a sacrifice (, ''zevach'') on the mountain and shared a meal with his relatives. And after Jacob learned that

Joseph

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

was still alive in Egypt, Genesis 46:1 reports that Jacob journeyed to

Beersheba

Beersheba ( / ; ), officially Be'er-Sheva, is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. Often referred to as the "Capital of the Negev", it is the centre of the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in Israel, the eighth-most p ...

and offered sacrifices (, ''zevachim'') to the God of his father, Isaac. And Moses and Aaron argued repeatedly with Pharaoh over their request to go three days' journey into the wilderness and sacrifice (, ''venizbechah'') to God.

The Hebrew Bible also includes several ambiguous reports in which Abraham or Isaac built or returned to an altar and "called upon the name of the Lord." In these cases, the text implies but does not explicitly state that the Patriarch offered a sacrifice. And at God's request, Abraham conducted an unusual sacrifice at the

Covenant between the Pieces () in Genesis 15:9–21.

Leviticus chapter 8

This is the pattern of instruction and construction of the Tabernacle and its furnishings:

Gordon Wenham

Gordon J. Wenham (; 21 May 1943 – 13 May 2025) was a Reformed British Old Testament scholar and writer. He authored several books about the Bible. Tremper Longman called him "one of the finest evangelical commentators today."

Early life and ...

noted that the phrase "as the Lord commanded Moses" or a similar phrase "recurs with remarkable frequency" in Leviticus 8–10, appearing in Leviticus 8:4, 5, 9, 13, 17, 21, 29, 34, 36; 9:6, 7, 10, 21; 10:7, 13, and 15.

The Hebrew Bible refers to the

Urim and Thummim

In the Hebrew Bible, the Urim ( ''ʾŪrīm'', "lights") and the Thummim ( ''Tummīm'', "perfection" or "truth") are elements of the '' hoshen'', the breastplate worn by the High Priest attached to the ephod, a type of apron or garment. The pair ...

in Exodus 28:30; Leviticus 8:8; Numbers 27:21;

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

33:8;

1 Samuel

The Book of Samuel () is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Samuel) in the Old Testament. The book is part of the Deuteronomistic history, a series of books (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) that constitute a theological ...

14:41 ("Thammim") and 28:6;

Ezra

Ezra ( fl. fifth or fourth century BCE) is the main character of the Book of Ezra. According to the Hebrew Bible, he was an important Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen'') in the early Second Temple period. In the Greek Septuagint, t ...

2:63; and

Nehemiah

Nehemiah (; ''Nəḥemyā'', "Yahweh, Yah comforts") is the central figure of the Book of Nehemiah, which describes his work in rebuilding Jerusalem during the Second Temple period as the governor of Yehud Medinata, Persian Judea under Artaxer ...

7:65; and may refer to them in references to "sacred utensils" in Numbers 31:6 and the Ephod in 1 Samuel 14:3 and 19; 23:6 and 9; and 30:7–8; and

Hosea

In the Hebrew Bible, Hosea ( or ; ), also known as Osee (), son of Beeri, was an 8th-century BC prophet in Israel and the nominal primary author of the Book of Hosea. He is the first of the Twelve Minor Prophets, whose collective writing ...

3:4.

The Torah mentions the combination of ear, thumb, and toe in three places. In Exodus 29:20, God instructed Moses how to initiate the priests, telling him to kill a ram, take some of its blood, and put it on the tip of the right ear of Aaron and his sons, on the thumb of their right hand, and the great toe of their right foot, and dash the remaining blood against the altar round about. And then Leviticus 8:23–24 reports that Moses followed God's instructions to initiate Aaron and his sons. Then, Leviticus 14:14, 17, 25, and 28 set forth a similar procedure for the cleansing of a person with skin disease (, ''

tzara'at''). In Leviticus 14:14, God instructed the priest on the day of the person's cleansing to take some of the blood of a guilt-offering and put it upon the tip of the right ear, the thumb of the right hand, and the great toe of the right foot of the one to be cleansed. And then in Leviticus 14:17, God instructed the priest to put oil on the tip of the right ear, the thumb of the right hand, and the great toe of the right foot of the one to be cleansed, on top of the blood of the guilt-offering. Finally, in Leviticus 14:25 and 28, God instructed the priest to repeat the procedure on the eighth day to complete the person's cleansing.

In early non-Rabbinic interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these early non-

Rabbinic

Rabbinic Judaism (), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, Rabbanite Judaism, or Talmudic Judaism, is rooted in the many forms of Judaism that coexisted and together formed Second Temple Judaism in the land of Israel, giving birth to classical rabb ...

sources:

Leviticus chapter 8

Reading Leviticus 8:23–24,

Philo

Philo of Alexandria (; ; ; ), also called , was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who lived in Alexandria, in the Roman province of Egypt.

The only event in Philo's life that can be decisively dated is his representation of the Alexandrian J ...

noted that Moses took some blood from the sacrificed ram, holding a vial under it to catch it, and with it, he anointed three parts of the body of the initiated priests—the tip of the ear, the extremity of the hand, and the extremity of the foot, all on the right side. Philo taught that this signified that the perfect person must be pure in every word, action, and all of one's life. For it is hearing that judges a person's words, the hand is the symbol of action and the foot of the way in which a person walks in life. Philo taught that since each of these parts is an extremity of the body, and on the right side, this indicates that improvement in everything is to be arrived at by dexterity, being a portion of felicity, and being the true aim in life, which a person must necessarily labor to attain, and to which a person ought to refer all actions, aiming at them in life as an archer aims at a target.

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in the

Rabbinic literature

Rabbinic literature, in its broadest sense, is the entire corpus of works authored by rabbis throughout Jewish history. The term typically refers to literature from the Talmudic era (70–640 CE), as opposed to medieval and modern rabbinic ...

from the era of the

Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; , from the verb ''šānā'', "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first written collection of the Jewish oral traditions that are known as the Oral Torah. Having been collected in the 3rd century CE, it is ...

and the

Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

:

Leviticus chapter 6

Tractate

Zevachim

Zevachim (; lit. "Sacrifices") is the first tractate of Seder Kodashim ("Holy Things") of the Mishnah, the Talmud and the Tosefta. This tractate discusses the topics related to the sacrificial system of the Temple in Jerusalem, namely the laws f ...

in the Mishnah,

Tosefta

The Tosefta ( "supplement, addition") is a compilation of Jewish Oral Law from the late second century, the period of the Mishnah and the Jewish sages known as the '' Tannaim''.

Background

Jewish teachings of the Tannaitic period were cha ...

, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the law of animal sacrifices in Leviticus 1–5. The Mishnah taught that a sacrifice was slaughtered for the sake of six things: (1) for the sake of the sacrifice for which it was consecrated, (2) for the sake of the offerer, (3) for the sake of the Divine Name, (4) for the sake of the altar fires, (5) for the sake of an aroma, and (6) for the sake of pleasing God, and a sin-offering and a guilt-offering for the sake of sin. Rabbi Jose taught that even if the offerer did not have any of these purposes at heart, the offering was valid because it was a court regulation since the intention was determined only by the priest who performed the service. The Mishnah taught that the intention of the priest conducting the sacrifice determined whether the offering would prove valid.

Rabbi Simeon taught that the Torah generally required a burnt offering only as expiation for sinful meditation of the heart.

A

Midrash

''Midrash'' (;["midrash"]

. ''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. ; or ''midrashot' ...

taught that if people repent, it is accounted as if they had gone up to

Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

, built the

Temple

A temple (from the Latin ) is a place of worship, a building used for spiritual rituals and activities such as prayer and sacrifice. By convention, the specially built places of worship of some religions are commonly called "temples" in Engli ...

and the altars, and offered all the sacrifices ordained in the Torah.

Rabbi Aha

Rabbi Aha (, read as ''Rabbi Achah'') was a rabbi of the Land of Israel, of the fourth century (fourth generation of amoraim).

Biography

He resided at Lod, but later settled in Tiberias where Huna II, Judah ben Pazi, and himself eventually cons ...

said in the name of Rabbi

Hanina ben Pappa that God accounts studying the sacrifices as equivalent to offering them.

Rav Huna

Rav Huna (Hebrew: רב הונא) was a Jewish Talmudist and Exilarch who lived in Babylonia, known as an amora of the second generation and head of the Academy of Sura; he was born about 216 CE (212 CE according to Gratz) and died in 296–297 ...

taught that God said that engaging in studying Mishnah is as if one were offering up sacrifices.

Samuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

taught that God said that engaging in the study of the law is like building the Temple. And the

Avot of Rabbi Natan

Avot of Rabbi Natan, also known as Avot de-Rabbi Nathan (ARN) (), the first and longest of the minor tractates of the Talmud, is a Jewish aggadic work probably compiled in the geonic era (c.700–900 CE). It is a commentary on an early form of the ...

taught that God loves Torah study more than sacrifice.

[Avot of Rabbi Natan, chapter 4.]

Rabbi Ammi taught that Abraham asked God if Israel would come to sin, would God punish them as God punished the generation of the Flood and the generation of the Tower of Babel. God answered that God would not. Abraham then asked God in Genesis 15:8: "How shall I know?" God replied in Genesis 15:9: "Take Me a heifer of three years old . . ." (indicating that Israel would obtain forgiveness through sacrifices). Abraham then asked God what Israel would do when the Temple no longer existed. God replied that whenever Jews read the Biblical text dealing with sacrifices, God would reckon it as if they were bringing an offering and exonerate all their iniquities.

The

Gemara

The Gemara (also transliterated Gemarah, or in Yiddish Gemore) is an essential component of the Talmud, comprising a collection of rabbinical analyses and commentaries on the Mishnah and presented in 63 books. The term is derived from the Aram ...

taught that when Rav

Sheshet

Rav Sheshet () was an amora of the third generation of the Talmudic academies in Babylonia (then Asoristan, now Lower Mesopotamia, Iraq). His name is sometimes read Shishat or Bar Shishat.

Biography

He was a colleague of Rav Nachman, with whom ...

fasted, on concluding his prayer, he added a prayer that God knew that when the Temple still stood, if people sinned, they used to bring sacrifices (pursuant to Leviticus 4:27–35 and 7:2–5), and though they offered only the animal's fat and blood, atonement was granted. Rav Sheshet continued that he had fasted and his fat and blood had diminished, so he asked that it be God's will to account for Rav Sheshet's fat and blood that had been diminished as if he had offered them on the Altar.

Rabbi Isaac declared that prayer is greater than sacrifice.

The Avot of Rabbi Natan taught that as Rabban

Joḥanan ben Zakai and

Rabbi Joshua

Joshua ben Hananiah ( ''Yəhōšūaʿ ben Ḥănanyā''; d. 131 CE), also known as Rabbi Yehoshua, was a leading tanna of the first half-century following the destruction of the Second Temple. He is the eighth-most-frequently mentioned sage in th ...

were leaving Jerusalem, Rabbi Joshua expressed sorrow that the place where the Israelites had atoned for their iniquities had been destroyed. But Rabban Joḥanan ben Zakai told him not to grieve, for we have in acts of loving-kindness another atonement as effective as a sacrifice at the Temple, as Hosea 6:6 says, "For I desire mercy and not sacrifice."

[

Rabbi Mani of Sheab and Rabbi Joshua of Siknin, in the name of Rabbi Levi, explained the origin of Leviticus 6:1. Moses prayed on Aaron's behalf, noting that the beginning of Leviticus repeatedly referred to Aaron's sons, barely mentioning Aaron himself. Moses asked whether God could love well water but hate the well. Moses noted that God honored the olive tree and the vine for the sake of their offspring, teaching that the priests could use all trees' wood for the altar fire except that of the olive and vine. Moses thus asked God whether God might honor Aaron for the sake of his sons, and God replied that God would reinstate Aaron and honor him above his sons. And thus, God said to Moses the words of Leviticus 6:1, "Command Aaron and his sons."

Rabbi Abin deduced from Leviticus 6:1 that burnt offerings were wholly given to the flames.

The School of ]Rabbi Ishmael

Rabbi Yishmael ben Elisha Nachmani (Hebrew: רבי ישמעאל בן אלישע), often known as Rabbi Yishmael and sometimes given the title "Ba'al HaBaraita" (Hebrew: בעל הברייתא, “Master of the Outside Teaching”), was a rabbi of ...

taught that whenever Scripture uses the word "command" (, ''tzav'') (as Leviticus 6:2 does), it denotes exhortation to obedience immediately and for all time. A Baraita

''Baraita'' ( "external" or "outside"; pl. ''bārayāṯā'' or in Hebrew ''baraitot''; also baraitha, beraita; Ashkenazi pronunciation: berayse) designates a tradition in the Oral Torah of Rabbinical Judaism that is not incorporated in the Mi ...

deduced exhortation to immediate obedience from the use of the word "command" in Deuteronomy 3:28, which says, "charge Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

, and encourage him, and strengthen him." The Baraita deduced exhortation to obedience for all time from the use of the word "command" in Numbers 15:23, which says, "Even all that the Lord has commanded you by the hand of Moses, from the day that the Lord gave the commandment, and onward throughout your generations."

Rabbi Joshua of Siknin said in Rabbi Levi's name that the wording of Leviticus 6:2 supports the argument of Rabbi Jose bar Hanina

Rabbi Jose bar Hanina (, read as ''Rabbi Yossi bar Hanina'') was an '' amora'' of the Land of Israel, from the second generation of the Amoraim.

Biography

He was a disciple of R. Yochanan bar Nafcha, and served as a dayan (religious judge). He w ...

(on which he differed with Rabbi Eleazar) that the descendants of Noah offered only burnt offerings (and not peace-offerings, as before the Revelation at Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai, also known as Jabal Musa (), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is one of several locations claimed to be the Mount Sinai (Bible), biblical Mount Sinai, the place where, according to the sacred scriptures of the thre ...

, people were unworthy to consume any part of an animal consecrated to God). Rabbi Joshua of Siknin noted that Leviticus 6:2 says, "This is the law of the burnt-offering: that is the burnt-offering," which Rabbi Joshua of Siknin read to mean "that is the burnt-offering" that the Noahides used to offer. But when Leviticus 7:11 addresses peace-offerings, it says, "And this is the law of the sacrifice of peace-offerings," and does not say, "that they offered" (which would indicate that they offered it in the past, before Revelation). Rabbi Joshua of Siknin thus read Leviticus 7:11 to teach that they would offer the peace offering only after the events of Leviticus 7:11.

Reading the words of Leviticus 6:2, "This is the law of the burnt-offering: it is that which goes up on its firewood upon the altar all night to the morning," the Mishnah concluded that the altar sanctified whatever was eligible for it. Rabbi Joshua taught that whatever was eligible for the altar fire did not descend once it had ascended. Thus, just as the burnt offering, which was eligible for the altar fire, did not descend once it had ascended, whatever was eligible for the altar fire did not descend.

The Gemara interpreted the words in Leviticus 6:2, "This is the law of the burnt-offering: It is that which goes up on its firewood upon the altar all night into the morning." From the passage, "which goes up on its firewood upon the altar all night," the Rabbis deduced that once a thing had been placed upon the altar, it could not be taken down all night. Rabbi Judah taught that the words "''This'' . . . goes up on . . . the altar all night" exclude three things. According to Rabbi Judah, they exclude (1) an animal slaughtered at night, (2) an animal whose blood was spilled, and (3) an animal whose blood was carried out beyond the curtains. Rabbi Judah taught that if any of these things had been placed on the altar, it was brought down. Rabbi Simeon noted that Leviticus 6:2 says "burnt-offering." From this, Rabbi Simeon taught that one can only know that a fit burnt offering remained on the altar. But Rabbi Simeon taught that the phrase "the law of the burnt offering" intimates one law for all burnt offerings: if they were placed on the altar, they were not removed. Rabbi Simeon taught that this law applied to animals that were slaughtered at night, whose blood was spilled, or whose blood passed out of the curtains, or whose flesh spent the night away from the altar, or whose flesh went out, or was unclean, or was slaughtered with the intention of burning its flesh after time or out of bounds, or whose blood was received and sprinkled by unfit priests, or whose blood was applied below the scarlet line when it should have been applied above, or whose blood was applied above when it should have been applied below, or whose blood was applied outside when it should have been applied within, or whose blood was applied within when it should have been applied outside, or a Passover-offering or a sin-offering that one slaughtered for a different purpose. Rabbi Simeon suggested that one might think that law would also include an animal used for bestiality, set aside for an idolatrous sacrifice or worshipped, a harlot's hire or the price of a dog (as referred to in Deuteronomy 23:19), or a mixed breed, or a ''trefah'' (a torn or otherwise disqualified animal), or an animal calved through a cesarean section. But Rabbi Simeon taught that the word "''This''" serves to exclude these. Rabbi Simeon explained that he included the former in the general rule because their disqualification arose in the sanctuary, while he excluded the latter because their disqualification did not arise in the sanctuary.

The Gemara taught that it is from the words of Leviticus 6:2, "upon the altar all night into the morning," that the Mishnah[Mishnah Megillah 2:6Babylonian Talmud Megillah 20b]

concludes that "the whole of the night is proper time for ... burning fat and limbs (on the altar)." And the Mishnah then set forth as a general rule: "Any commandment which is to be performed by night may be performed during the whole of the night."[

] The Rabbis taught a story reflecting the importance of the regular offering required by Leviticus 6:2: When the Hasmonean brothers Hyrcanus and Aristobulus were contending with one another, and one was within Jerusalem's city wall and the other was outside, those within would let down a basket of money to their besiegers every day, and in return the besiegers would send up kosher animals for the regular sacrifices. But an older man among the besiegers argued that they could not be defeated as long as those within were allowed to continue to perform sacrifices. So, the next day, when those inside sent down the money basket, the besiegers sent up a pig. When the pig reached the center of the wall, it stuck its hooves into the wall, and an earthquake shook the entire

The Rabbis taught a story reflecting the importance of the regular offering required by Leviticus 6:2: When the Hasmonean brothers Hyrcanus and Aristobulus were contending with one another, and one was within Jerusalem's city wall and the other was outside, those within would let down a basket of money to their besiegers every day, and in return the besiegers would send up kosher animals for the regular sacrifices. But an older man among the besiegers argued that they could not be defeated as long as those within were allowed to continue to perform sacrifices. So, the next day, when those inside sent down the money basket, the besiegers sent up a pig. When the pig reached the center of the wall, it stuck its hooves into the wall, and an earthquake shook the entire Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

. On that occasion, the Rabbis cursed those who bred pigs.

It was taught in the name of Rabbi Nehemiah

Rabbi Nehemiah was a rabbi who lived circa 150 AD (fourth generation of tannaim).

He was one of the great students of Rabbi Akiva, and one of the rabbis who received semicha from R' Judah ben Baba

The Talmud equated R' Nechemiah with Rabbi Ne ...

that in obedience to Leviticus 6:2, the Israelites kept the fire burning on the altar for about 116 years. Yet, the wood of the altar did not burn, and the brass did not melt, even though it was taught in the name of Rabbi Hoshaiah that the metal was only as thick as a coin.

Rabbi Levi read Leviticus 6:2 homiletically to mean: "This is the law regarding a person striving to be high: It is that it goes up on its burning place." Thus, Rabbi Levi read the verse to teach that a person who behaves boastfully should be punished by fire.

A Midrash deduced the importance of peace from the way that the listing of the individual sacrifices in Leviticus 6–7 concludes with the peace offering. Leviticus 6:2–6 gives "the law of the burnt-offering," Leviticus 6:7–11 gives "the law of the meal-offering," Leviticus 6:18–23 gives "the law of the sin-offering," Leviticus 7:1–7 gives "the law of the guilt-offering," and Leviticus 7:11–21 gives "the law of the sacrifice of peace-offerings." Similarly, the Midrash found evidence for the importance of peace in the summary of Leviticus 7:37, which concludes with "the sacrifice of the peace offering."

Rabbi Judah the Levite, the son of Rabbi Shalom, taught that God's arrangements are not like those of mortals. For example, the cook of a human master dons fair apparel when going out but puts on ragged things and an apron when working in the kitchen. Moreover, when sweeping the stove or oven, the cook wears even worse clothing. But in God's presence, when the priest swept the altar and removed the ashes from it, he donned fine garments, as Leviticus 6:3 says: "And the priest shall put on his linen garment," so that "he shall take up the ashes." This is to teach that pride has no place with the Omnipresent.

A Baraita interpreted the term "his fitted linen garment" (, ''mido'') in Leviticus 6:3 to teach that each priestly garment in Exodus 28 had to be fitted to the particular priest, and had to be neither too short nor too long.

The Gemara interpreted the words "upon his body" in Leviticus 6:3 to teach that there would be nothing between the priest's body and his priestly garment.

left, 300px, The Tabernacle, with the laver and altar (2009 illustration by Gabriel L. Fink)

Elaborating on the procedure in Leviticus 6:3–4 for removing ash from the altar, the Mishnah taught that the priests would get up early and cast lots for the right to remove the ashes. The priest who won the right to clear the ashes would prepare to do so. They warned him not to touch any vessel until he washed his hands and feet. No one entered with him. He did not carry any light but proceeded by the light of the altar fire. No one saw or heard a sound from him until they heard the noise of the wooden wheel Ben Katin made for the laver. When they told him the time had come, he washed his hands and feet with water from the laver, took the silver fire pan, went to the top of the altar, cleared away the cinders on either side and scooped up the ashes in the center. He then came down, and when he reached the floor, he turned to the north (toward the altar) and went along the east side of the ramp for about ten cubits, and he then piled the cinders on the pavement three handbreadths away from the ramp, in the place where they used to put the crop of the birds, the ashes from the inner altar, and the ash from the menorah.

Rabbi Joḥanan called his garments "my honor." Rabbi Aha bar Abba said in Rabbi Joḥanan's name that Leviticus 6:4, "And he shall put off his garments, and put on other garments," teaches that a change of garments is an act of honor in the Torah. The School of Rabbi Ishmael taught that the Torah teaches us manners: In the garments in which one cooks a dish for one's master, one should not pour a cup of wine for one's master. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba

Ḥiyya bar Abba (), Ḥiyya bar Ba (), or Ḥiyya bar Wa () was a third-generation amoraic sage of the Land of Israel, of priestly descent, who flourished at the end of the third century.

Biography

In both Talmuds he is frequently called me ...

said in Rabbi Joḥanan's name that it is a disgrace for a scholar to go into the marketplace with patched shoes. The Gemara objected that Rabbi Aha bar Hanina went out that way; Rabbi Aha, son of Rav Naḥman, clarified that the prohibition is of patches upon patches. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba also said in Rabbi Joḥanan's name that any scholar who has a grease stain on a garment is worthy of death, for Wisdom

Wisdom, also known as sapience, is the ability to apply knowledge, experience, and good judgment to navigate life’s complexities. It is often associated with insight, discernment, and ethics in decision-making. Throughout history, wisdom ha ...

says in Proverbs

A proverb (from ) or an adage is a simple, traditional saying that expresses a perceived truth based on common sense or experience. Proverbs are often metaphorical and are an example of formulaic language. A proverbial phrase or a proverbial ...

8:36, "All they that hate me (, ''mesanne'ai'') love (merit) death," and we should read not , ''mesanne'ai'', but , ''masni'ai'' (that make me hated, that is, despised). Thus, a scholar who has no pride in personal appearance brings contempt upon learning. Ravina taught that this was stated about a thick patch (or, others say, a bloodstain). The Gemara harmonized the two opinions by teaching that one referred to an outer garment, the other to an undergarment. Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba also said in Rabbi Joḥanan's name that in Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

20:3, "As my servant Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

walked naked and barefoot," "naked" means in worn-out garments, and "barefoot" means in patched shoes.

Tractate Menachot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the law of meal offerings in Leviticus 6:7–16.

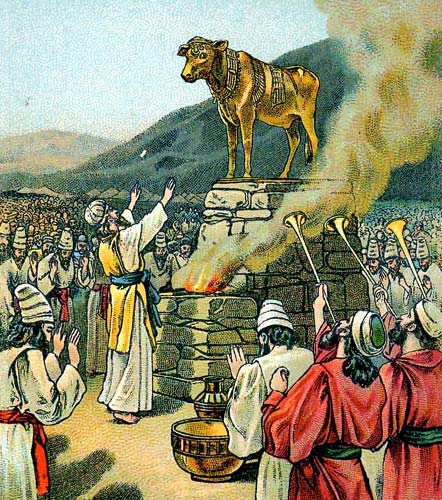

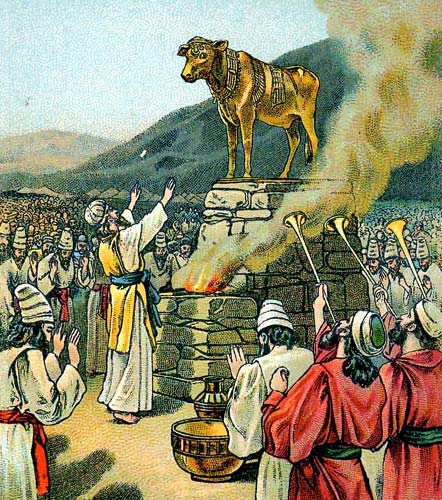

The Rabbis taught that through the word "this," Aaron became degraded, as it is said in Exodus 32:22–24, "And Aaron said: '. . . I cast it into the fire, and there came out ''this'' calf,'" and through the word "this," Aaron was also elevated, as it is said in Leviticus 6:13, "''This'' is the offering of Aaron and of his sons, which they shall offer to the Lord on the day when he is anointed" to become High Priest.

And noting the similarity of language between "This is the sacrifice of Aaron" in Leviticus 6:13 and "This is the sacrifice of

Tractate Menachot in the Mishnah, Tosefta, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the law of meal offerings in Leviticus 6:7–16.

The Rabbis taught that through the word "this," Aaron became degraded, as it is said in Exodus 32:22–24, "And Aaron said: '. . . I cast it into the fire, and there came out ''this'' calf,'" and through the word "this," Aaron was also elevated, as it is said in Leviticus 6:13, "''This'' is the offering of Aaron and of his sons, which they shall offer to the Lord on the day when he is anointed" to become High Priest.

And noting the similarity of language between "This is the sacrifice of Aaron" in Leviticus 6:13 and "This is the sacrifice of Nahshon

In the Hebrew Bible, Nahshon ( ''Naḥšon'') was a tribal leader of the Tribe of Judah, Judahites during the wilderness wanderings of the Book of Numbers. In the King James Version, the name is spelled Naashon, and is within modern Rabbinical c ...

the son of Amminadab" and each of the other princes of the 12 tribes in Numbers 7:17–83, the Rabbis concluded that Aaron's sacrifice was as beloved to God as the sacrifices of the princes of the 12 tribes.

A Midrash noted that the commandment of Leviticus 6:13 that Aaron offer sacrifices paralleled Samson

SAMSON (Software for Adaptive Modeling and Simulation Of Nanosystems) is a computer software platform for molecular design being developed bOneAngstromand previously by the NANO-D group at the French Institute for Research in Computer Science an ...

's riddle "out of the eater came forth food", for Aaron was to eat the sacrifices, and by virtue of Leviticus 6:13, a sacrifice was to come from him.

Leviticus chapter 7

A Midrash read the words of Psalm 50:23, "Whoso offers the sacrifice of thanksgiving honors Me," to teach that the thanksgiving offerings of Leviticus 7:12 honored God more than sin offerings or guilt offerings. Rabbi Huna said in the name of Rabbi Aha that Psalm 50:23 taught that one who gave a thanksgiving offering gave God honor upon honor. Rabbi Berekiah said in the name of Rabbi Abba bar Kahana that the donor honored God in this world and will honor God in the World to Come

The world to come, age to come, heaven on Earth, and the Kingdom of God are eschatology, eschatological phrases reflecting the belief that the World (theology), current world or Dispensation (period), current age is flawed or cursed and will be r ...

. The continuation of Psalm 50:23, "to him who sets right the way," refers to those who clear stones from roads. Alternatively, the Midrash taught that it refers to teachers of Scripture and the Oral Law

An oral law is a code of conduct in use in a given culture, religion or community application, by which a body of rules of human behaviour is transmitted by oral tradition and effectively respected, or the single rule that is orally transmitted.

M ...

who sincerely instruct the young. Alternatively, Jose ben Judah said in the name of Rabbi Menahem, the son of Rabbi Jose, that it refers to shopkeepers who sell produce that has already been tithed. Alternatively, the Midrash taught that it refers to people who light lamps to provide light for the public.

Rabbi Phinehas compared the thanksgiving offerings of Leviticus 7:12 to the case of a king whose tenants and intimates came to pay him honor. From his tenants and entourage, the king merely collected their tribute. But when another who was neither a tenant nor a member of the king's entourage came to offer him homage, the king offered him a seat. Thus, Rabbi Phinehas read Leviticus 7:12 homiletically, which means: "If it be for a thanksgiving, He odwill bring him he offerernear o God

Oh God may refer to:

* An exclamation; similar to "oh no", "oh yes", "oh my", "aw goodness", "ah gosh", "ah gawd"; see interjection

An interjection is a word or expression that occurs as an utterance on its own and expresses a spontaneous feeling ...

" Rabbi Phinehas, Rabbi Levi, and Rabbi Joḥanan said in the name of Rabbi Menahem of Gallia that in the Time to Come, all sacrifices will be annulled, but the thanksgiving sacrifice of Leviticus 7:12 will not be annulled, and all prayers will be annulled, but the Thanksgiving (, ''Modim'') prayer will not be annulled.

In reading the requirement of Leviticus 7:12 for the loaves of the thanksgiving sacrifice, the Mishnah interpreted that if one made them for oneself, then they were exempt from the requirement to separate challah

Challah or hallah ( ; , ; 'c'''hallot'', 'c'''halloth'' or 'c'''hallos'', ), also known as berches in Central Europe, is a special bread in Jewish cuisine, usually braided and typically eaten on ceremonial occasions such as Shabbat ...

, but if one made them to sell in the market, then they were subject to the requirement to separate challah.

The Mishnah taught that a vow offering, as in Leviticus 7:16, was when one said, "It is incumbent upon me to bring a burnt offering" (without specifying a particular animal). A freewill offering was when one said, "''This'' animal shall serve as a burnt offering" (specifying a particular animal). In the case of vow offerings, one was responsible for the replacement of the animal if the animal died or was stolen, but in the case of freewill obligations, one was not held responsible for the animal's replacement if the specified animal died or was stolen.

Rabbi Eliezer

Eliezer ben Hurcanus (or Hyrcanus) () was one of the most prominent Judean ''tannaitic'' Sages of 1st- and 2nd-century Judaism, a disciple of Rabban Yohanan ben Zakkai,Avot of Rabbi Natan 14:5 and a colleague of Gamaliel II (whose sister, I ...

taught that the prohibition of eating the meat of a peace offering on the third day in Leviticus 7:18 also applied to invalidate the sacrifice of one who merely ''intended'' to eat sacrificial meat on the third day.

The Sages taught that one may trust butchers to remove chelev

Chelev (, ''ḥēleḇ''), "suet", is the animal fats that the Torah prohibits Jews and Israelites from eating. Only the ''chelev'' of animals that are of the sort from which offerings can be brought in the Tabernacle or Temple are prohibited () ...

, the fat that Leviticus 3:17 and 7:23 forbid.

Rabbi Berekiah said in the name of Rabbi Isaac that in the Time to Come, God will make a banquet for God's righteous servants, and whoever had not eaten meat from an animal that died other than through ritual slaughtering (, ''neveilah'', prohibited by Leviticus 17:1–4) in this world will have the privilege of enjoying it in the World to Come. This is indicated by Leviticus 7:24, which says, "And the fat of that which dies of itself (, ''neveilah'') and the fat of that which is torn by beasts (, ''tereifah''), may be used for any other service, but you shall not eat it," so that one might eat it in the Time to Come. (By one's present self-restraint, one might merit partaking in the banquet in the Hereafter.) For this reason, Moses admonished the Israelites in Leviticus 11:2, "This is the animal that you shall eat."

A Baraita explained how the priests performed the waiving. A priest placed the sacrificial portions on the palm of his hand, the breast and thigh on top of the sacrificial portions, and whenever there was a bread offering, the bread on top of the breast and thigh. Rav Papa

Rav Pappa () (c. 300 – died 375) was a Babylonian rabbi, of the fifth generation of amoraim.

Biography

He was a student of Rava and Abaye. After the death of his teachers he founded a school at Naresh, a city near Sura, in which he officiat ...

found authority for the Baraita's teaching in Leviticus 8:26–27, which states that they placed the bread on top of the thigh. And the Gemara noted that Leviticus 10:15 implies that the breast and thigh were on top of the offerings of fat. But the Gemara noted that Leviticus 7:30 says the priest "shall bring the fat upon the breast." Abaye

Abaye () was an amora of the fourth generation of the Talmudic academies in Babylonia. He was born about the close of the third century and died in 337.

Biography

Abaye, according to Talmudic tradition, was the head of the Pumbedita Academy unt ...

reconciled the verses by explaining that Leviticus 7:30 refers to how the priest brought the parts from the slaughtering place. The priest then turned them over and placed them into the hands of a second priest, who waived them. Noting further that Leviticus 9:20 says that "they put the fat upon the breasts," the Gemara deduced that this second priest then handed the parts over to a third priest, who burned them. The Gemara thus concluded that these verses taught that three priests were required for this part of the service, giving effect to the teaching of Proverbs 14:28, "In the multitude of people is the king's glory."

Rabbi Aha compared the listing of Leviticus 7:37 to a ruler who entered a province, escorting many bands of robbers as captives. Upon seeing the scene, one citizen expressed his fear of the ruler. A second citizen answered that they had no reason to fear if their conduct was good. Similarly, when the Israelites heard the section of the Torah dealing with sacrifices, they became afraid. But Moses told them not to be afraid; if they occupied themselves with the Torah, they would have no reason to fear.[Leviticus Rabbah 9:8.]

A Midrash asked why Leviticus 7:37 mentions peace offerings last in its list of sacrifices and suggested that it was because there are many kinds of peace offerings. Rabbi Simon said that assorted desserts always come last because they consist of many kinds of things.Judah ben Bathyra

Judah ben Bathyra or simply Judah Bathyra (also Beseira, ) was an eminent tanna. The Mishnah quotes 17 laws by R. Judah, and the Baraita about 40; he was also a prolific aggadist. He was a member of the Bnei Bathyra family. Biography

He must have ...

counted Leviticus 7:38 among 13 limiting phrases recorded in the Torah to inform us that God spoke not to Aaron but to Moses with instruction that he should tell Aaron. Rabbi Judah ben Bathyra taught that these 13 limiting phrases correspond to and limit 13 Divine communications recorded in the Torah as having been made to both Moses and Aaron.

Leviticus chapter 8

Rabbi Samuel bar Naḥman taught that Moses first incurred his fate of dying in the wilderness from his conduct at the Burning Bush

The burning bush (or the unburnt bush) refers to an event recorded in the Jewish Torah (as also in the biblical Old Testament and Islamic scripture). It is described in the third chapter of the Book of Exodus as having occurred on Mount Horeb ...

, for there God tried for seven days to persuade Moses to go on his errand to Egypt, as Exodus 4:10 says, “And Moses said to the Lord: ‘Oh Lord, I am not a man of words, neither yesterday, nor the day before, nor since you have spoken to your servant’” (which the Midrash interpreted to indicate seven days of conversation). And in the end, Moses told God in Exodus 4:13, "Send, I pray, by the hand of him whom You will send." God replied that God would keep this in store for Moses. Rabbi Berekiah, in Rabbi Levi's name, and Rabbi Helbo give different answers on when God repaid Moses. One said that during all seven days of the consecration of the priesthood in Leviticus 8, Moses functioned as a high priest, and he came to think that the office belonged to him. But in the end, God told Moses that the job was not his, but his brother's, as Leviticus 9:1 says, “And it came to pass on the eighth day, that Moses called Aaron.” The other taught that all the first seven days of Adar

Adar (Hebrew: , ; from Akkadian ''adaru'') is the sixth month of the civil year and the twelfth month of the religious year on the Hebrew calendar, roughly corresponding to the month of March in the Gregorian calendar. It is a month of 29 days. ...

of the fortieth year, Moses beseeched God to enter the Promised Land

In the Abrahamic religions, the "Promised Land" ( ) refers to a swath of territory in the Levant that was bestowed upon Abraham and his descendants by God in Abrahamic religions, God. In the context of the Bible, these descendants are originally ...

, but in the end, God told him in Deuteronomy 3:27, “You shall not go over this Jordan.”

Rabbi Jose noted that even though Exodus 27:18 reported that the Tabernacle's courtyard was just 100 cubits by 50 cubits (about 150 feet by 75 feet), a little space held a lot, as Leviticus 8:3 implied that the space miraculously held the entire Israelite people.

The Tosefta deduced from the congregation's placement in Leviticus 8:4 that in a synagogue

A synagogue, also called a shul or a temple, is a place of worship for Jews and Samaritans. It is a place for prayer (the main sanctuary and sometimes smaller chapels) where Jews attend religious services or special ceremonies such as wed ...

, as well, the people face toward the sanctuary.

The Mishnah taught that the High Priest inquired of the Urim and Thummim, as noted in Leviticus 8:8, only for the king, for the court, or for one whom the community needed.[Mishnah Yoma 7:5Babylonian Talmud Yoma 71b]

A Baraita explained why the Urim and Thummim noted in Leviticus 8:8 were called by those names: The term "Urim" is like the Hebrew word for "lights," and thus it was called "Urim" because it enlightened. The term "Thummim" is like the Hebrew word ''tam'' meaning "to be complete," and thus, it was called "Thummim" because its predictions were fulfilled. The Gemara discussed how they used the Urim and Thummim: Rabbi Joḥanan said that the letters of the stones in the breastplate stood out to spell out the answer. Resh Lakish said that the letters joined each other to spell words. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter , ''tsade

Tsade (also spelled , , , , tzadi, sadhe, tzaddik) is the eighteenth Letter (alphabet), letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician alphabet, Phoenician ''ṣādē'' 𐤑, Hebrew alphabet, Hebrew ''ṣādī'' , Aramaic alphabet, Aramaic ''� ...

'', was missing from the list of the 12 tribes of Israel. Rabbi Samuel bar Isaac said that the stones of the breastplate also contained the names of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. But the Gemara noted that the Hebrew letter , ''teth

Teth, also written as or Tet, is the ninth letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician ''ṭēt'' 𐤈, Hebrew, Aramaic

''ṭēṯ'' 𐡈, and Syriac ''ṭēṯ'' ܛ, and Arabic ''ṭāʾ'' . It is also related to the Ancient North ...

'', was also missing. Rav Aha bar Jacob

Rav Aha bar Jacob (or R. Aha bar Ya'akov; ) was a Babylonian rabbi of the third and fourth generations of Amoraim.

He was one of the disciples of Rav Huna. He was also one of the prominent Jewish leaders of Papunia. In the Talmud it is said th ...

said that they also contained the words: "The tribes of Jeshurun

Jeshurun ( ''Yəšurūn'') is a poetic name for Israel used in the Hebrew Bible.

Etymology

A hypocoristicon of the name ''Israel'' (יִשְׂרָאֵל ''Yiśrāʾēl''). The vocalization of this name reflects the Phoenician Shift, so may be ...

." The Gemara taught that although the decree of a prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

could be revoked, the decree of the Urim and Thummim could not be revoked, as Numbers 27:21 says, "By the judgment of the Urim."

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer

Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer (, 'Chapters of Rabbi Eliezer'; abbreviated , 'PRE') is an aggadic-midrashic work of Torah exegesis and retellings of biblical stories. Traditionally, the work is attributed to the tanna Eliezer ben Hurcanus and his scho ...

taught that when Israel sinned in the matter of the devoted things, as reported in Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

7:11, Joshua looked at the 12 stones corresponding to the 12 tribes that were upon the High Priest's breastplate. For every tribe that had sinned, the light of its stone became dim, and Joshua saw that the stone's light for the tribe of Judah

According to the Hebrew Bible, the tribe of Judah (, ''Shevet Yehudah'') was one of the twelve Tribes of Israel, named after Judah (son of Jacob), Judah, the son of Jacob. Judah was one of the tribes to take its place in Canaan, occupying it ...

had become dim. So Joshua knew that the tribe of Judah had transgressed in the matter of the devoted things. Similarly, the Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer taught that Saul

Saul (; , ; , ; ) was a monarch of ancient Israel and Judah and, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament, the first king of the United Monarchy, a polity of uncertain historicity. His reign, traditionally placed in the late eleventh c ...

saw the Philistines

Philistines (; LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philistines origi ...

turning against Israel, and he knew that Israel had sinned in the matter of the ban. Saul looked at the 12 stones, and for each tribe that had followed the law, its stone (on the High Priest's breastplate) shined with its light, and for each tribe that had transgressed, the light of its stone was dim. So Saul knew that the tribe of Benjamin

According to the Torah, the Tribe of Benjamin () was one of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. The tribe was descended from Benjamin, the youngest son of the Patriarchs (Bible), patriarch Jacob (later given the name Israel) and his wife Rachel. In the ...

had trespassed in the matter of the ban.

The Mishnah reported that with the death of the former prophets

The (; ) is the second major division of the Hebrew Bible (the ''Tanakh''), lying between the () and (). The Nevi'im are divided into two groups. The Former Prophets ( ) consists of the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings ...

, the Urim and Thummim ceased. In this connection, the Gemara reported differing views of who the former prophets were. Rav Huna

Rav Huna (Hebrew: רב הונא) was a Jewish Talmudist and Exilarch who lived in Babylonia, known as an amora of the second generation and head of the Academy of Sura; he was born about 216 CE (212 CE according to Gratz) and died in 296–297 ...

said they were David, Samuel

Samuel is a figure who, in the narratives of the Hebrew Bible, plays a key role in the transition from the biblical judges to the United Kingdom of Israel under Saul, and again in the monarchy's transition from Saul to David. He is venera ...

, and Solomon

Solomon (), also called Jedidiah, was the fourth monarch of the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and Judah, according to the Hebrew Bible. The successor of his father David, he is described as having been the penultimate ...

. Rav Naḥman noted that during the days of David, they were sometimes successful and sometimes not (getting an answer from the Urim and Thummim), for Zadok

Zadok (), also spelled Ṣadok, Ṣadoc, Zadoq, Tzadok or Tsadoq (; lit. 'righteous, justified'), was a Kohen (priest), biblically recorded to be a descendant of Eleazar the son of Aaron. He was the High Priest of Israel during the reigns of Dav ...

consulted it and succeeded, while Abiathar

Abiathar ( ''ʾEḇyāṯār'', "father (of) abundance"/"abundant father"), in the Hebrew Bible, is a son of Ahimelech or Ahijah, Kohen Gadol, High Priest at Nob, Israel, Nob, the fourth in descent from Eli (Bible), Eli and the last of Eli's Ho ...

consulted it and was not successful, as 2 Samuel 15:24 reports, "And Abiathar went up." (He retired from the priesthood because the Urim and Thummim gave him no reply.) Rabbah bar Samuel asked whether the report of 2 Chronicles

The Book of Chronicles ( , "words of the days") is a book in the Hebrew Bible, found as two books (1–2 Chronicles) in the Christian Old Testament. Chronicles is the final book of the Hebrew Bible, concluding the third section of the Jewish Tan ...

26:5, "And he (King Uzziah

Uzziah (; ''‘Uzzīyyāhū'', meaning "my strength is Yah"; ; ), also known as Azariah (; ''‘Azaryā''; ; ), was the tenth king of the ancient Kingdom of Judah, and one of Amaziah's sons. () Uzziah was 16 when he became king of Judah and ...

of Judah) set himself to seek God all the days of Zechariah, who had understanding in the vision of God," did not refer to the Urim and Thummim. But the Gemara answered that Uzziah did so through Zechariah's prophecy. A Baraita said that when the first Temple was destroyed, the Urim and Thummim ceased, and explained Ezra 2:63 (reporting events after the Jews returned from the Babylonian Captivity

The Babylonian captivity or Babylonian exile was the period in Jewish history during which a large number of Judeans from the ancient Kingdom of Judah were forcibly relocated to Babylonia by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The deportations occurred ...

), "And the governor said to them that they should not eat of the most holy things till there stood up a priest with Urim and Thummim," as a reference to the remote future, as when one speaks of the time of the Messiah

In Abrahamic religions, a messiah or messias (; ,

; ,

; ) is a saviour or liberator of a group of people. The concepts of '' mashiach'', messianism, and of a Messianic Age originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible, in which a ''mashiach ...

. Rav Naḥman concluded that the term "former prophets" referred to a period before Haggai

Haggai or Aggeus (; – ''Ḥaggay''; ; Koine Greek: Ἀγγαῖος; ) was a Hebrew prophet active during the building of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, one of the twelve minor prophets in the Hebrew Bible, and the author or subject of the ...

, Zechariah, and Malachi

Malachi or Malachias (; ) is the name used by the author of the Book of Malachi, the last book of the Nevi'im (Prophets) section of the Hebrew Bible, Tanakh. It is possible that ''Malachi'' is not a proper name, because it means "messenger"; ...

, who were among the latter prophets. And the Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud (, often for short) or Palestinian Talmud, also known as the Talmud of the Land of Israel, is a collection of rabbinic notes on the second-century Jewish oral tradition known as the Mishnah. Naming this version of the Talm ...

taught that the "former prophets" referred to Samuel and David, and thus the Urim and Thummim did not function in the period of the First Temple, either.

The Gemara taught that the early scholars were called ''sofer

A sofer, sopher, sofer SeTaM, or sofer ST"M (, "scribe"; plural , ) is a Jewish scribe who can transcribe Sifrei Kodesh (holy scrolls), tefillin (phylacteries), Mezuzah, mezuzot (ST"M, , is an abbreviation of these three terms) and other religio ...

im'' (related to the original sense of its root ''safar'', "to count") because they used to count all the letters of the Torah (to ensure the correctness of the text). They used to say the '' vav'' () in , ''gachon'' ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 marks the half-way point of the letters in the Torah. (And in a Torah Scroll, scribes write that ''vav'' () larger than the surrounding letters.) They used to say the words , ''darosh darash'' ("diligently inquired"), in Leviticus 10:16 mark the half-way point of the words in the Torah. And they used to say Leviticus 13:33 marks the halfway point of the verses in the Torah. Rav Joseph asked whether the ''vav'' () in , ''gachon'' ("belly"), in Leviticus 11:42 belonged to the first half or the second half of the Torah. (Rav Joseph presumed that the Torah contains an even number of letters.) The scholars replied that they could bring a Torah Scroll and count, for Rabbah bar bar Hana said on a similar occasion that they did not stir from where they were until a Torah Scroll was brought, and they counted. Rav Joseph replied that they (in Rabbah bar bar Hanah's time) were thoroughly versed in the proper defective and full spellings of words (that could be spelled in variant ways), but they (in Rav Joseph's time) were not. Similarly, Rav Joseph asked whether Leviticus 13:33 belongs to the first or second half of verses. Abaye replied that for verses, we can at least bring a scroll and count them. But Rav Joseph replied that they could no longer be certain even with verses. For when Rav Aha bar Adda came (from the Land of Israel to Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

), he said that in the West (in the Land of Israel), they divided Exodus 19:9 into three verses. Nonetheless, the Rabbis taught in a Baraita that there are 5,888 verses in the Torah. (Note that others say the middle letter in our current Torah text is the ''aleph

Aleph (or alef or alif, transliterated ʾ) is the first Letter (alphabet), letter of the Semitic abjads, including Phoenician alphabet, Phoenician ''ʾālep'' 𐤀, Hebrew alphabet, Hebrew ''ʾālef'' , Aramaic alphabet, Aramaic ''ʾālap'' � ...

'' () in , ''hu'' ("he") in Leviticus 8:28; the middle two words are , ''el yesod'' ("at the base of") in Leviticus 8:15; the half-way point of the verses in the Torah is Leviticus 8:7; and there are 5,846 verses in the Torah text we have today.)

The Sifra

Sifra () is the Midrash halakha to the Book of Leviticus. It is frequently quoted in the Talmud and the study of it followed that of the Mishnah. Like Leviticus itself, the midrash is occasionally called Torat Kohanim, and in two passages ''Sifr ...

taught that the words "and put it upon the tip of Aaron's right ear" in Leviticus 8:23 refer to the middle ridge of the ear. And the Sifra taught that the words "and upon the thumb of his right hand" in Leviticus 8:23 refer to the middle knuckle.

A Master said in a Baraita that using the thumb for service in Leviticus 8:23–24 and 14:14, 17, 25, and 28 showed that every finger has its own unique purpose.