Lentiviral Vector on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A viral vector is a modified

Adenoviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the family ''

Adenoviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the family ''

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are relatively small single-stranded DNA viruses belonging to ''

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are relatively small single-stranded DNA viruses belonging to ''

Of the nine herpesviruses that infect humans, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is the most well characterized and most commonly used as a viral vector. HSV-1 offers several advantages: it has broad tropism and can deliver therapeutics via specialized expression systems. Moreover, HSV-1 can cross the blood brain barrier if medically-disrupted, enabling it to target neurological diseases. Also, HSV-1 does not integrate into the host genome and can carry large amounts of foreign DNA. The former feature prevents harmful mutagenesis, as can occur with retroviral and adeno-associated vectors. Replication-deficient strains have been developed.

In 2015,

Of the nine herpesviruses that infect humans, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is the most well characterized and most commonly used as a viral vector. HSV-1 offers several advantages: it has broad tropism and can deliver therapeutics via specialized expression systems. Moreover, HSV-1 can cross the blood brain barrier if medically-disrupted, enabling it to target neurological diseases. Also, HSV-1 does not integrate into the host genome and can carry large amounts of foreign DNA. The former feature prevents harmful mutagenesis, as can occur with retroviral and adeno-associated vectors. Replication-deficient strains have been developed.

In 2015,

virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

designed to deliver genetic material into cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

. This process can be performed inside an organism or in cell culture

Cell culture or tissue culture is the process by which cell (biology), cells are grown under controlled conditions, generally outside of their natural environment. After cells of interest have been Cell isolation, isolated from living tissue, ...

. Viral vectors have widespread applications in basic research, agriculture, and medicine.

Viruses have evolved specialized molecular mechanisms to transport their genomes

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

into infected hosts, a process termed transduction. This capability has been exploited for use as viral vectors, which may integrate their genetic cargo—the transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

—into the host genome, although non-integrative vectors are also commonly used. In addition to agriculture and laboratory research, viral vectors are widely applied in gene therapy

Gene therapy is Health technology, medical technology that aims to produce a therapeutic effect through the manipulation of gene expression or through altering the biological properties of living cells.

The first attempt at modifying human DNA ...

: as of 2022, all approved gene therapies were viral vector-based. Further, compared to traditional vaccines

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an ag ...

, the intracellular antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

expression enabled by viral vector vaccines

A viral vector vaccine is a vaccine that uses a viral vector to deliver genetic material (DNA) that can be transcribed by the recipient's host cells as mRNA coding for a desired protein, or antigen, to elicit an immune response. , six viral vector ...

offers more robust immune activation.

Many types of viruses have been developed into viral vector platforms, ranging from retroviruses

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. After invading a host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase ...

to cytomegaloviruses. Different viral vector classes vary widely in strengths and limitations, suiting some to specific applications. For instance, relatively non-immunogenic and integrative vectors like lentiviral vectors are commonly employed for gene therapy. Chimeric viral vectors—such as hybrid vectors with qualities of both bacteriophages

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures tha ...

and eukaryotic viruses—have also been developed.

Viral vectors were first created in 1972 by Paul Berg

Paul Berg (June 30, 1926 – February 15, 2023) was an American biochemist and professor at Stanford University.

He was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980, along with Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger. The award recogniz ...

. Further development was temporarily halted by a recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

research moratorium following the Asilomar Conference and stringent National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in 1887 and is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Service ...

regulations. Once lifted, the 1980s saw both the first recombinant viral vector gene therapy and the first viral vector vaccine. Although the 1990s saw significant advances in viral vectors, clinical trials had a number of setbacks, culminating in Jesse Gelsinger

Jesse Gelsinger (June 18, 1981 – September 17, 1999) was the first person publicly identified as having died in a clinical trial for gene therapy. Gelsinger suffered from ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, an X-linked genetic disease of the ...

's death. However, in the 21st century, viral vectors experienced a resurgence and have been globally approved for the treatment of various diseases. They have been administered to billions of patients, notably during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

.

Characteristics

Viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are found in almo ...

, infectious agents

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ.

The term ...

composed of a protein coat that encloses a genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

, are the most numerous biological entities on Earth. As they cannot replicate independently, they must infect cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

and hijack the host

A host is a person responsible for guests at an event or for providing hospitality during it.

Host may also refer to:

Places

* Host, Pennsylvania, a village in Berks County

* Host Island, in the Wilhelm Archipelago, Antarctica

People

* ...

's replication machinery in order to produce copies of themselves. Viruses do this by inserting their genome—which can be DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

, either single-stranded or double-stranded—into the host. Some viruses may integrate their genome directly into that of the host in the form of a provirus

A provirus is a virus genome that is integrated into the DNA of a host cell. In the case of bacterial viruses (bacteriophages), proviruses are often referred to as prophages. However, proviruses are distinctly different from prophages and these te ...

.

This ability to transfer foreign genetic material has been exploited by genetic engineers

Genetic engineering, also called genetic modification or genetic manipulation, is the modification and manipulation of an organism's genes using technology. It is a set of technologies used to change the genetic makeup of cells, including th ...

to create viral vectors, which can transduce the desired transgene

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

into a target cell. Viral vectors consists of three components:

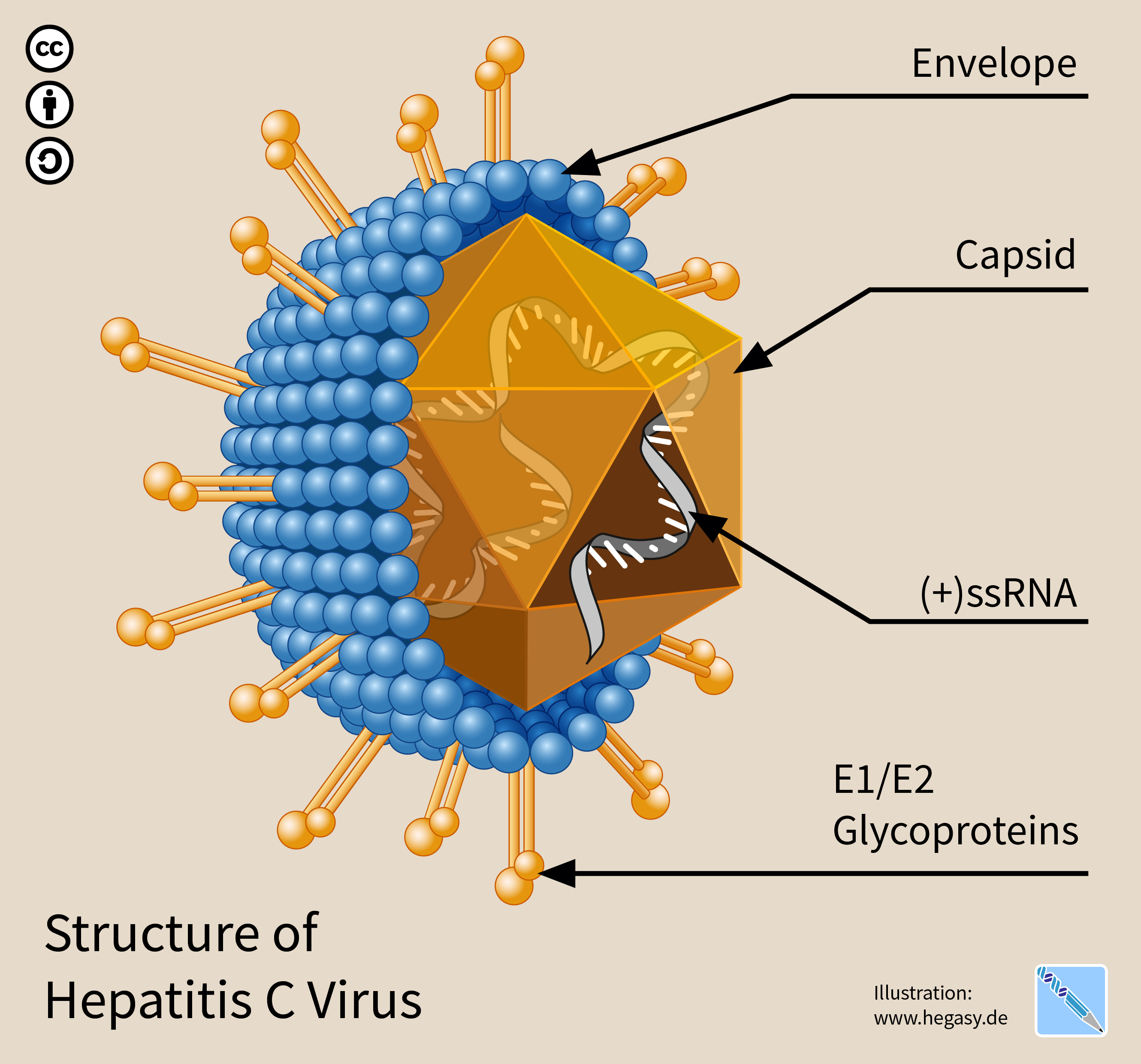

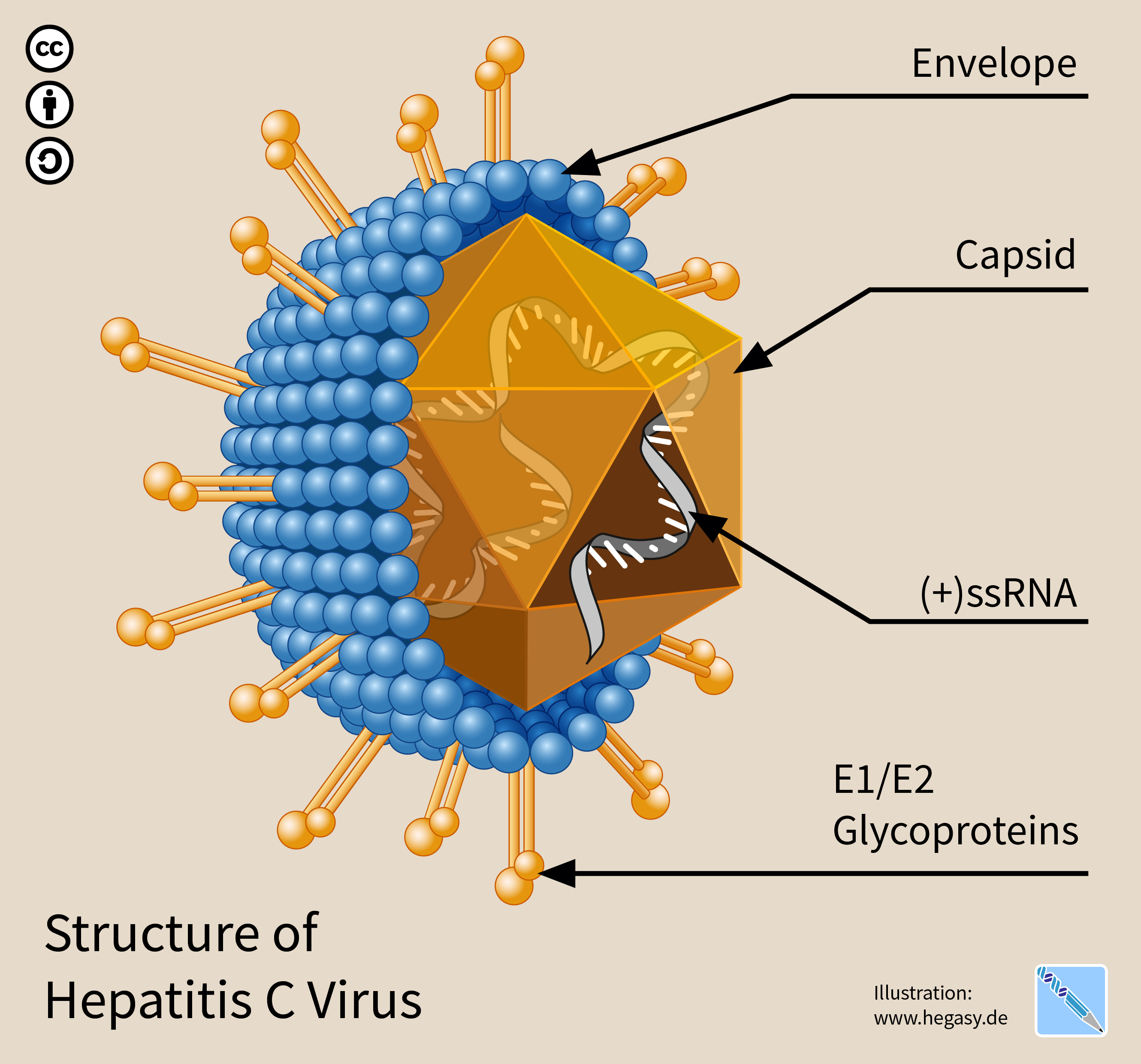

#A protein capsid and sometimes an envelope

An envelope is a common packaging item, usually made of thin, flat material. It is designed to contain a flat object, such as a letter (message), letter or Greeting card, card.

Traditional envelopes are made from sheets of paper cut to one o ...

that encapsidates the genetic payload. This determines the range of cell types

A cell type is a classification used to identify cells that share morphological or phenotypical features. A multicellular organism may contain cells of a number of widely differing and specialized cell types, such as muscle cells and skin cell ...

that the vector infects, termed its tropism

In biology, a tropism is a phenomenon indicating the growth or turning movement of an organism, usually a plant, in response to an environmental stimulus (physiology), stimulus. In tropisms, this response is dependent on the direction of the s ...

.

#A genetic payload: the transgene that results in the desired effect when expressed.

#A " regulatory cassette" that controls transgene expression, whether integrated into a host chromosome

A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most import ...

or as an episome

An episome is a special type of plasmid, which remains as a part of the eukaryotic genome without integration. Episomes manage this by replicating together with the rest of the genome and subsequently associating with metaphase chromosomes during m ...

. The cassette comprises an enhancer, a promoter, and auxiliary elements.

Applications

Basic research

Viral vectors are routinely used in abasic research

Basic research, also called pure research, fundamental research, basic science, or pure science, is a type of scientific research with the aim of improving scientific theories for better understanding and prediction of natural or other phenome ...

setting and can introduce genes encoding, for instance, complementary DNA

In genetics, complementary DNA (cDNA) is DNA that was reverse transcribed (via reverse transcriptase) from an RNA (e.g., messenger RNA or microRNA). cDNA exists in both single-stranded and double-stranded forms and in both natural and engin ...

, short hairpin RNA

A short hairpin RNA or small hairpin RNA (shRNA/Hairpin Vector) is an artificial RNA molecule with a tight hairpin turn that can be used to silence target gene expression via RNA interference (RNAi). Expression of shRNA in cells is typically acc ...

, or CRISPR/Cas9 systems for gene editing. Viral vectors are employed for cellular reprogramming, like inducing pluripotent stem cells or differentiating adult somatic cells into different cell types. Researchers also use viral vectors to create transgenic mice and rats for experiments. Viral vectors can be used for ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

'' imaging via the introduction of a reporter gene

Reporter genes are molecular tools widely used in molecular biology, genetics, and biotechnology to study gene function, expression patterns, and regulatory mechanisms. These genes encode proteins that produce easily detectable signals, such as ...

. Further, transduction of stem cells can permit the tracing of cell lineage during development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development (music), the process by which thematic material is reshaped

* Photographic development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

* Development hell, when a proje ...

.

Gene therapy

Gene therapy

Gene therapy is Health technology, medical technology that aims to produce a therapeutic effect through the manipulation of gene expression or through altering the biological properties of living cells.

The first attempt at modifying human DNA ...

seeks to modulate or otherwise affect gene expression via the introduction of a therapeutic transgene. Gene therapy by viral vectors can be performed by ''in vivo'' delivery by directly administering the vector to the patient, or ''ex vivo

refers to biological studies involving tissues, organs, or cells maintained outside their native organism under controlled laboratory conditions. By carefully managing factors such as temperature, oxygenation, nutrient delivery, and perfusi ...

'' by extracting cells from the patient, transducing them, and then reintroducing the modified cells into the patient. Viral vector gene therapies may also be used for plants, tentatively enhancing crop performance or promoting sustainable production.

There are four broad categories of gene therapy: gene replacement, gene silencing

Gene silencing is the regulation of gene expression in a cell to prevent the expression of a certain gene. Gene silencing can occur during either Transcription (genetics), transcription or Translation (biology), translation and is often used in res ...

, gene addition, or gene editing. Relative to other non-integrative gene therapy approaches, transgenes introduced by viral vectors offer multi-year long expression.

Vaccines

For use asvaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

platforms, viral vectors can be engineered to carry a specific antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

associated with an infectious disease or a tumor antigen

Tumor antigen is an antigenic substance produced in tumor cells, i.e., it triggers an immune response in the host. Tumor antigens are useful tumor markers in identifying tumor cells with diagnostic tests and are potential candidates for use in ...

. Conventional vaccines are not suitable for protection against some pathogens due to unique immune evasion strategies and differences in pathogenesis. Viral vector-based vaccines, for instance, could eventually offer immunity against HIV-1

The subtypes of HIV include two main subtypes, known as HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV type 2 (HIV-2). These subtypes have distinct genetic differences and are associated with different epidemiological patterns and clinical characteristics.

HIV-1 e ...

and malaria

Malaria is a Mosquito-borne disease, mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects vertebrates and ''Anopheles'' mosquitoes. Human malaria causes Signs and symptoms, symptoms that typically include fever, Fatigue (medical), fatigue, vomitin ...

.

While traditional subunit vaccines elicit a humoral response, viral vectors allow for intracellular antigen expression that activates MHC pathways via both direct and crosspresentation pathways. This induces a robust adaptive immune response. Viral vector vaccines also have intrinsic adjuvant properties via innate immune system activation and the expression of pathogen-associated molecular patterns

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are small molecular motifs conserved within a class of microbes, but not present in the host. They are recognized by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in both ...

, negating the need for any additional adjuvant. In addition to a more robust immune response in comparison to other vaccine types, viral vectors offer efficient gene transduction and can target specific cell types. Pre-existing immunity to the virus used as the vector, however, can be a significant issue.

Prior to 2020, viral vector vaccines were widely administered but confined to veterinary medicine. In the global response to the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, viral vector vaccines played a fundamental role and were administered to billions of people, particularly in low and middle-income nations.

Types

Retroviruses

Retroviruses

A retrovirus is a type of virus that inserts a DNA copy of its RNA genome into the DNA of a host cell that it invades, thus changing the genome of that cell. After invading a host cell's cytoplasm, the virus uses its own reverse transcriptase ...

—enveloped RNA viruses—are popular viral vector platforms due to their ability to integrate genetic material into the host genome. Retroviral vectors comprise two general classes: gamma retroviral and lentiviral vectors. The fundamental difference between the two are that gamma retroviral vectors can only infect dividing cells, while lentiviral vectors can infect both dividing and resting cells. Notably, retroviral genomes are composed of single-stranded RNA and must be converted to proviral double-stranded DNA, a process known as reverse transcription

A reverse transcriptase (RT) is an enzyme used to convert RNA genome to DNA, a process termed reverse transcription. Reverse transcriptases are used by viruses such as HIV and hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B to replicate their genomes, by retrot ...

—before it is integrated into the host genome via viral proteins like integrase

Retroviral integrase (IN) is an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme ...

.

The most commonly used gammaretroviral vector is a modified Moloney murine leukemia virus Moloney may refer to:

* Moloney (surname), people with the surname ''Moloney''

* ''Moloney'' (TV series), 1996–97 American television police drama

See also

* Maloney

*Moloney's Mimic Bat

Moloney's mimic bat (''Mimetillus moloneyi'') is a speci ...

(MMLV), able to transduce various mammalian cell types. MMLV vectors have been associated with some cases of carcinogenesis. Gammaretroviral vectors have been successfully applied to ''ex vivo'' hematopoietic stem cell to treat multiple genetic diseases.

Lentiviral vectors

Most lentiviral vectors are derived fromhuman immunodeficiency virus type 1

The subtypes of HIV include two main subtypes, known as HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV type 2 (HIV-2). These subtypes have distinct genetic differences and are associated with different epidemiological patterns and clinical characteristics.

HIV-1 e ...

(HIV-1), although modified simian immunodeficiency virus

Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) is a species of retrovirus that cause persistent infections in at least 45 species of non-human primates. Based on analysis of strains found in four species of monkeys from Bioko Island, which was isolated fr ...

(SIV), the feline immunodeficiency virus

Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a lentivirus that affects cats worldwide and 2.5% to 4.4% of felines are infected.

FIV was first isolated in 1986, by Niels C. Pedersen and Janet K. Yamamoto at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Med ...

(FIV), and the equine infectious anaemia virus

Equine infectious anemia or equine infectious anaemia (EIA), also known by horsemen as swamp fever, is a horse disease caused by a retrovirus (Equine infectious anemia virus) and transmitted by bloodsucking insects. The virus (EIAV) is endemic in ...

(EIAV) have also been utilized. As all functional genes are removed or otherwise mutated, the vectors are not cytopathic

Cytopathic effect (abbreviated CPE) refers to structural changes in host cells that are caused by viral invasion. The infecting virus causes lysis of the host cell or when the cell dies without lysis due to an inability to replicate. If a virus ca ...

and can be engineered to be non-integrative.

Lentiviral vectors are able to carry up to 10 kb of foreign genetic material, although 3-4 kb was reported as optimal as of 2023. Relative to other viral vectors, lentiviral vectors possess the greatest transduction capacity, due to the formation of a three-stranded "DNA flap" during retro-transcription of the single-strand lentiviral RNA to DNA within the host.

Although largely non-inflammatory, lentiviral vectors can induce robust adaptive immune responses by memory-type cytotoxic T cells

A cytotoxic T cell (also known as TC, cytotoxic T lymphocyte, CTL, T-killer cell, cytolytic T cell, CD8+ T-cell or killer T cell) is a T lymphocyte (a type of white blood cell) that kills cancer cells, cells that are infected by intracellular pa ...

and T helper cells

The T helper cells (Th cells), also known as CD4+ cells or CD4-positive cells, are a type of T cell that play an important role in the adaptive immune system. They aid the activity of other immune cells by releasing cytokines. They are considere ...

. This is largely due to lentiviral vectors' high tropism for dendritic cells

A dendritic cell (DC) is an antigen-presenting cell (also known as an ''accessory cell'') of the mammalian immune system. A DC's main function is to process antigen material and present it on the cell surface to the T cells of the immune system ...

, which activate T cells. However, they can infect all types of antigen-presenting cells. Moreover, as they are the only retroviral vectors able to efficiently transduce both dividing and non-dividing cells, make them the most promising vaccine platforms. They have also been trialed as vaccines against cancer.

Lentiviral vectors have been used as ''in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

'' therapies, such as directly treating genetic diseases like haemophilia B

Haemophilia B, also spelled hemophilia B, is a blood clotting disorder causing easy bruising and bleeding due to an inherited mutation of the gene for factor IX, and resulting in a deficiency of factor IX. It is less common than factor VIII defic ...

and for ''ex vivo

refers to biological studies involving tissues, organs, or cells maintained outside their native organism under controlled laboratory conditions. By carefully managing factors such as temperature, oxygenation, nutrient delivery, and perfusi ...

'' treatments like immune cell modification in CAR T cell therapy. In 2017, the US Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a federal agency of the Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is responsible for protecting and promoting public health through the control and supervision of food ...

(FDA) approved tisagenlecleucel

Tisagenlecleucel, sold under the brand name Kymriah, is a CAR T cells medication for the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) which uses the body's own T cells to fight cancer (adoptive cell transfer).

The most common serious ...

, a lentiviral vector, for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is a cancer of the lymphoid line of blood cells characterized by the development of large numbers of immature lymphocytes. Symptoms may include feeling tired, pale skin color, fever, easy bleeding or bruis ...

.

Adenoviruses

Adenoviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the family ''

Adenoviruses are double-stranded DNA viruses belonging to the family ''Adenoviridae

Adenoviruses (members of the family (biology), family ''Adenoviridae'') are medium-sized (90–100 nanometer, nm), nonenveloped (without an outer lipid bilayer) viruses with an icosahedral nucleocapsid containing a double-stranded DNA genome. ...

''. Their relatively large genomes, of approximately 30-45 kb, make them ideal candidates for genetic delivery; newer adenoviral vectors can carry up to 37 kb of foreign genetic material. Adenoviral vectors display high transduction efficiency and transgene expression, and can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells.

The adenoviral capsid, an icosahedron

In geometry, an icosahedron ( or ) is a polyhedron with 20 faces. The name comes . The plural can be either "icosahedra" () or "icosahedrons".

There are infinitely many non- similar shapes of icosahedra, some of them being more symmetrical tha ...

, features a fibre "knob" at each of its 12 vertices. These fibre proteins mediate cell entry—greatly affecting efficacy and contribute to its broad tropism—notably via coxsackie–adenovirus receptors (CARs). Adenoviral vectors can induce robust innate and adaptive immune responses. Its strong immunogenicity is particularly due to the transduction of dendritic cells (DC), upregulating the expression of both MHC I and II molecules and activating the DCs. They have a strong adjuvant effect, as they display several pathogen-associated molecular patterns

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are small molecular motifs conserved within a class of microbes, but not present in the host. They are recognized by toll-like receptors (TLRs) and other pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) in both ...

. One disadvantage is that pre-existing immunity to adenovirus serotypes is common, reducing efficacy. The use of chimpanzee adenoviruses may circumvent this issue.

While the activation of both innate and adaptive immune responses is an obstacle for many therapeutic applications, it makes adenenoviral vectors an ideal vaccine platform. The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic saw the development and use of multiple adenoviral vector vaccines, including Sputnik V

Sputnik V (, the brand name from the Russian Direct Investment Fund or RDIF) or Gam-COVID-Vac (, the name under which it is legally registered and produced) is an adenovirus viral vector vaccine for COVID-19 developed by the Gamaleya Resea ...

, the Oxford–AstraZeneca vaccine, and the Janssen vaccine.

Adeno-associated viruses

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are relatively small single-stranded DNA viruses belonging to ''

Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) are relatively small single-stranded DNA viruses belonging to ''Parvoviridae

Parvoviruses are a family of animal viruses that constitute the family ''Parvoviridae''. They have linear, single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genomes that typically contain two genes encoding for a replication initiator protein, called NS1, and the pr ...

'' and, like lentiviral vectors, AAVs can infect both dividing and non-dividing cells. AAVs, however, require the presence of a "helper virus" such as an adenovirus or herpes simplex virus to replicate within the host, although it can do so independently if cellular stress is induced or the helper virus genes are carried by the vector.

AAVs insert themselves into a specific site in the host genome, particularly ''AAVS1'' on chromosome 19

Chromosome 19 is one of the 23 pairs of chromosomes in humans. People normally have two copies of this chromosome. Chromosome 19 spans more than 61.7 million base pairs, the building material of DNA. It is considered the most Gene density, gene-ri ...

in humans. However, recombinant AAVs have been designed that do not integrate. These are instead stored as episomes that, in non-dividing cells, can last for years. One disadvantage is that they are not able to carry large amounts of foreign genetic materials. Furthermore, the need to express the complementary strand for its single-stranded genome may delay transgene expression.

As of 2020, 11 different AAV serotypes—differing by capsid structure and consequently by tropism—had been identified. The tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors can be tailored by creating recombinant versions from multiple serotypes, termed pseudotyping. Due to their ability to infect and induce longlasting effects within nondividing cells, AAVs are commonly used in basic neuroscience research. Following the approval of the AAV Alipogene tiparvovec

Alipogene tiparvovec, sold under the brand name Glybera, is a gene therapy treatment designed to reverse lipoprotein lipase deficiency (LPLD), a rare recessive disorder, due to mutations in LPL, which can cause severe pancreatitis. It was rec ...

in Europe in 2012, in 2017, the FDA approved the first AAV-based in vivo gene therapy— voretigene neparvovec—which treated RPE65-associated Leber congenital amaurosis. As of 2020, 230 clinical trials using AAV-based treatments were either underway or had been completed.

Vaccinia

Vaccinia virus

The vaccinia virus (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

, a poxvirus

''Poxviridae'' is a family of double-stranded DNA viruses. Vertebrates and arthropods serve as natural hosts. The family contains 22 genera that are assigned to two subfamilies: ''Chordopoxvirinae'' and ''Entomopoxvirinae''. ''Entomopoxvirinae'' ...

, is another promising candidate for viral vector development. Its use as the smallpox vaccine

The smallpox vaccine is used to prevent smallpox infection caused by the variola virus. It is the first vaccine to have been developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with th ...

—first reported by Edward Jenner

Edward Jenner (17 May 1749 – 26 January 1823) was an English physician and scientist who pioneered the concept of vaccines and created the smallpox vaccine, the world's first vaccine. The terms ''vaccine'' and ''vaccination'' are derived f ...

in 1798—led to the eradication of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

and demonstrated vaccinia as safe and effective in humans. Moreover, manufacturing procedures developed to mass-produce smallpox vaccine stockpiles may expedite vaccinia viral vector production.

Vaccinia possesses a large DNA genome and can consequently carry up to 40 kb of foreign DNA. Further, vaccinia are unlikely to integrate into the host genome, decreasing the chance of carcinogenesis. Attenuated strains—replicating and non-replicating—have been developed. Although widely characterized due to its use against smallpox, as of 2019 the function of 50 percent of the vaccinia genome was unknown. This may lead to unpredictable effects.

As a vaccine platform, vaccinia vectors display highly effective transgene expression and create a robust immune response. The virus fast-acting: its life cycle produces mature progeny vaccinia within 6 hours, and has three viral spread mechanisms. Vaccinia also has an adjuvant effect, activating a strong innate response via toll-like receptors

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a class of proteins that play a key role in the innate immune system. They are single-pass membrane protein, single-spanning receptor (biochemistry), receptors usually expressed on sentinel cells such as macrophages ...

. A significant disadvantage that can reduce its efficacy, however, is pre-existing immunity against vaccinia in those who received the smallpox vaccine.

Herpesviruses

Of the nine herpesviruses that infect humans, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is the most well characterized and most commonly used as a viral vector. HSV-1 offers several advantages: it has broad tropism and can deliver therapeutics via specialized expression systems. Moreover, HSV-1 can cross the blood brain barrier if medically-disrupted, enabling it to target neurological diseases. Also, HSV-1 does not integrate into the host genome and can carry large amounts of foreign DNA. The former feature prevents harmful mutagenesis, as can occur with retroviral and adeno-associated vectors. Replication-deficient strains have been developed.

In 2015,

Of the nine herpesviruses that infect humans, herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is the most well characterized and most commonly used as a viral vector. HSV-1 offers several advantages: it has broad tropism and can deliver therapeutics via specialized expression systems. Moreover, HSV-1 can cross the blood brain barrier if medically-disrupted, enabling it to target neurological diseases. Also, HSV-1 does not integrate into the host genome and can carry large amounts of foreign DNA. The former feature prevents harmful mutagenesis, as can occur with retroviral and adeno-associated vectors. Replication-deficient strains have been developed.

In 2015, talimogene laherparepvec

Talimogene laherparepvec, sold under the brand name Imlygic among others, is a biopharmaceutical medication used to treat melanoma that cannot be operated on; it is injected directly into a subset of lesions which generates a systemic immune re ...

—an HSV-1 vector that triggers an anti-tumor immune response—was approved by the FDA to treat melanoma

Melanoma is the most dangerous type of skin cancer; it develops from the melanin-producing cells known as melanocytes. It typically occurs in the skin, but may rarely occur in the mouth, intestines, or eye (uveal melanoma). In very rare case ...

. As of 2020, HSV-1 vectors have been experimentally applied against sarcomas

A sarcoma is a rare type of cancer that arises from cells of mesenchymal origin. Originating from mesenchymal cells means that sarcomas are cancers of connective tissues such as bone, cartilage, muscle, fat, or vascular tissues.

Sarcomas are ...

and cancers of the brain, colon, prostate, and skin.

Cytomegalovirus

''Cytomegalovirus'' (CMV) (from ''cyto-'' 'cell' via Greek - 'container' + 'big, megalo-' + -''virus'' via Latin 'poison') is a genus of viruses in the order '' Herpesvirales'', in the family '' Herpesviridae'', in the subfamily '' Betaherp ...

(CMV), a herpesvirus, has also been developed for use as a viral vector. CMV can infect most cell types and can thus proliferate throughout the body. Although a CMV-based vaccine provided significant immunity against SIV—closely related to HIV—in macaques, development of CMV as a reliable vector was reported to still be in early stages as of 2020.

Plant viruses

Plant viruses are also engineered viral vectors for use in agriculture, horticulture, and biologic production. These vectors have been employed for a range of applications, from increasing the aesthetic quality ofornamental plants

Ornamental plants or ''garden plants'' are plants that are primarily grown for their beauty but also for qualities such as scent or how they shape physical space. Many flowering plants and garden varieties tend to be specially bred cultivars th ...

to pest biocontrol, rapid expression of recombinant proteins and peptides, and to accelerate crop breeding. The use of engineered plant viruses has been proposed to enhance crop performance and promote sustainable production.

Replicating virus-based vectors are typically used. RNA viruses used for monocots include wheat streak mosaic virus

Wheat streak mosaic virus (WSMV) is a plant pathogenic virus of the family ''Potyviridae'' that infects plants in the family Poaceae, especially wheat (''Triticum spp.''); it is globally distributed and vectored by the wheat curl mite, particula ...

and barley stripe mosaic virus

Barley stripe mosaic virus (BSMV), of genus ''Hordevirus'', is an RNA viral plant pathogen whose main hosts are barley and wheat. The common symptoms for BSMV are yellow streaks or spots, mosaic, leaves and stunted growth. It is spread primaril ...

and, for dicots, tobacco rattle virus

Tobacco rattle virus (TRV) is a pathogenic plant virus. Over 400 species of plants from 50 families are susceptible to infection.geminiviruses have also been utilized. Viral vectors can be administered to plants via several pathways termed "agro-inoculation", including via rubbing, a biolistic delivery system, agrospray, agroinjection, and even via

Viral vector manufacturing methods often vary by vector, although most utilize an adherent or suspension-based system with mammalian cells. For viral vector production on a smaller, laboratory setting, static cell culture systems like Petri dishes are typically used.

Those techniques used in the laboratory are difficult to scale, requiring different approaches on an industrial scale. Large single-use disposable culture systems and

Viral vector manufacturing methods often vary by vector, although most utilize an adherent or suspension-based system with mammalian cells. For viral vector production on a smaller, laboratory setting, static cell culture systems like Petri dishes are typically used.

Those techniques used in the laboratory are difficult to scale, requiring different approaches on an industrial scale. Large single-use disposable culture systems and

In film, viral vectors are often portrayed as unintentionally causing a pandemic and civilizational catastrophe. The 2007 film '' I Am Legend'' depicts a cancer-targeting viral vector as unleashing a

In film, viral vectors are often portrayed as unintentionally causing a pandemic and civilizational catastrophe. The 2007 film '' I Am Legend'' depicts a cancer-targeting viral vector as unleashing a

insect vectors

In epidemiology, a disease vector is any living agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen such as a parasite or microbe, to another living organism. Agents regarded as vectors are mostly blood-sucking (hematophagous) arthropods such ...

. However, ''Agrobacterium

''Agrobacterium'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria established by Harold J. Conn, H. J. Conn that uses horizontal gene transfer to cause tumors in plants. ''Agrobacterium tumefaciens'' is the most commonly studied species in this genus. ''Agr ...

''-mediated delivery of viral vectors—in which bacteria are transformed with plasmid DNA encoding the viral vector construct—is the most common approach.

Bacteriophages

Chimeric vectors combining both bacteriophages and eukaryotic viruses have been developed and are capable of infecting eukaryotic cells. Unlike eukaryotic virus-based vectors, such bacteriophage vectors have no innate tropism for eukaryotic cells, allowing them to be engineered to be highly specific for cancer cells. Bacteriophage vectors are also commonly used in molecular biology. For instance, bacteriophage vectors are used in phage-assisted continuous evolution, promoting rapid mutagenesis of bacteria. Although limited tomycobacteriophages

A mycobacteriophage is a member of a group of bacteriophages known to have mycobacteria as host bacterial species. While originally isolated from the bacterial species ''Mycobacterium smegmatis'' and ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'', the causative ...

and some phages of gram-negative bacteria

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the Crystal violet, crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelo ...

, bacteriophages can be used for direct cloning.

Manufacture

bioreactors

A bioreactor is any manufactured device or system that supports a biologically active environment. In one case, a bioreactor is a vessel in which a chemical process is carried out which involves organisms or biochemically active substances derive ...

are commonly used by manufacturers. Vessels such as those with gas permeable surfaces are used to maximize cell culture density and solution transducing units. Depending on the vessel, viruses can be directly isolated from the supernatant or isolated via chemical lysis of the cultured cells or microfluidization. In 2017, ''The New York Times'' reported a manufacturing backlog of inactivated viruses, delaying some gene therapy trials by years.

History

In 1972,Stanford University

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a Private university, private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth ...

biochemist Paul Berg

Paul Berg (June 30, 1926 – February 15, 2023) was an American biochemist and professor at Stanford University.

He was the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1980, along with Walter Gilbert and Frederick Sanger. The award recogniz ...

developed the first viral vector, incorporating DNA from the lambda phage

Lambda phage (coliphage λ, scientific name ''Lambdavirus lambda'') is a bacterial virus, or bacteriophage, that infects the bacterial species ''Escherichia coli'' (''E. coli''). It was discovered by Esther Lederberg in 1950. The wild type of ...

into the polyomavirus SV40

SV40 is an abbreviation for simian vacuolating virus 40 or simian virus 40, a polyomavirus that is found in both monkeys and humans. Like other polyomaviruses, SV40 is a DNA virus that is found to cause tumors in humans and animals, but most ofte ...

to infect kidney cells maintained in culture. The implications of this achievement troubled scientists like Robert Pollack, who convinced Berg not to transduce DNA from SV40 into ''E. coli'' via a bacteriophage vector. They feared that introducing the purportedly cancer-causing genes of SV40 would create carcinogenic bacterial strains. These concerns and others in the emerging field of recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

led to the Asilomar Conference of 1975, where attendees agreed to a voluntary moratorium on cloning DNA.

In 1977, the National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in 1887 and is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Service ...

(NIH) issued formal guidelines confining viral DNA cloning to rigid BSL-4 conditions, practically preventing such research. However, the NIH loosened these rules in 1979, permitting Bernard Moss to develop a viral vector utilizing vaccinia

The vaccinia virus (VACV or VV) is a large, complex, enveloped virus belonging to the poxvirus family. It has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kbp in length, which encodes approximately 250 genes. The dimensions of the ...

. In 1982, Moss reported the first use of a viral vector for transient gene expression. The following year, Moss used the vaccinia vector to express a hepatitis B

Hepatitis B is an infectious disease caused by the '' hepatitis B virus'' (HBV) that affects the liver; it is a type of viral hepatitis. It can cause both acute and chronic infection.

Many people have no symptoms during an initial infection. ...

antigen, creating the first viral vector vaccine.

Although a failed gene therapy attempt utilizing wild-type Shope papilloma virus

The Shope papilloma virus (SPV), also known as cottontail rabbit papilloma virus (CRPV) or ''Kappapapillomavirus 2'', is a papillomavirus which infects certain leporids, causing keratinous carcinomas resembling horns, typically on or near t ...

had been made as early as 1972, Martin Cline attempted the first gene therapy utilizing recombinant DNA in 1980. It proved unsuccessful. In the 1990s, as genetic diseases were further characterized and viral vector technology improved, there was overoptimism about the capabilities the technology. Many clinical trials proved failures. There were some successes, such as the first effective gene therapy for severe combined immunodeficiency

Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), also known as Swiss-type agammaglobulinemia, is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the disturbed development of functional T cells and B cells caused by numerous genetic mutations that result in diff ...

(SCID); it employed a retroviral vector.

However, during a 1999 clinical trial at the University of Pennsylvania

The University of Pennsylvania (Penn or UPenn) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. One of nine colonial colleges, it was chartered in 1755 through the efforts of f ...

, Jesse Gelsinger

Jesse Gelsinger (June 18, 1981 – September 17, 1999) was the first person publicly identified as having died in a clinical trial for gene therapy. Gelsinger suffered from ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, an X-linked genetic disease of the ...

died from a fatal reaction to an adenoviral vector-based gene therapy. It was the first death related to any form of gene therapy. Consequently, the FDA suspended all gene therapy trials at the University of Pennsylvania and investigated 60 others across the US. An anonymous editorial in ''Nature Medicine

''Nature Medicine'' is a monthly peer-reviewed medical journal published by Nature Portfolio covering all aspects of medicine. It was established in 1995. The journal seeks to publish research papers that "demonstrate novel insight into disease p ...

'' noted that it represented a "loss of innocence" for viral vectors. Shortly thereafter, the field's reputation was further damaged when 5 children treated with a SCID gene therapy developed leukemia

Leukemia ( also spelled leukaemia; pronounced ) is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and produce high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called ''blasts'' or '' ...

due to an issue with the retroviral vector.

Viral vectors experienced a resurgence when they were successfully employed for ''ex vivo'' hematopoietic gene delivery in clinical settings. In 2003, China approved the first gene therapy for clinical use: Gendicine

Gendicine is a gene therapy medication used to treat patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma linked to mutations in the ''TP53'' gene. It consists of recombinant adenovirus engineered to code for p53 protein (rAd-p53) and is manuf ...

, an adenoviral vector encoding p53

p53, also known as tumor protein p53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory transcription factor protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thou ...

. In 2012, the European Union issued its first approval of a gene therapy, an adeno-associated viral vector. During the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic (also known as the coronavirus pandemic and COVID pandemic), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began with an disease outbreak, outbreak of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China, in December ...

, viral vector vaccines were used to an unprecedented extent: administered to billions of people. As of 2022, all approved gene therapies were viral vector-based and over 1000 viral vector clinical trials targeting cancer were underway.

In popular culture

In film, viral vectors are often portrayed as unintentionally causing a pandemic and civilizational catastrophe. The 2007 film '' I Am Legend'' depicts a cancer-targeting viral vector as unleashing a

In film, viral vectors are often portrayed as unintentionally causing a pandemic and civilizational catastrophe. The 2007 film '' I Am Legend'' depicts a cancer-targeting viral vector as unleashing a zombie apocalypse

Zombie apocalypse is a subgenre of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction in which society collapses due to overwhelming swarms of zombies. Usually, only a few individuals or small bands of human survivors are left living.

There are many d ...

. Similarly, a viral vector therapy for Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

in ''Rise of the Planet of the Apes

''Rise of the Planet of the Apes'' is a 2011 American science fiction action film directed by Rupert Wyatt from a screenplay by Rick Jaffa and Amanda Silver. It is a reboot of the ''Planet of the Apes'' film series and is the seventh install ...

'' (2011) becomes a deadly pathogen and causes an ape uprising. Other films featuring viral vectors include '' The Bourne Legacy'' (2012) and '' Resident Evil: The Final Chapter'' (2016).

Notes and references

Notes

Citations

Works cited

Journal articles

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *News articles

* * *Books and protocols

* * * {{Self-replicating organic structures, state=collapsed Cell culture techniques Gene delivery Molecular genetics Virotherapy