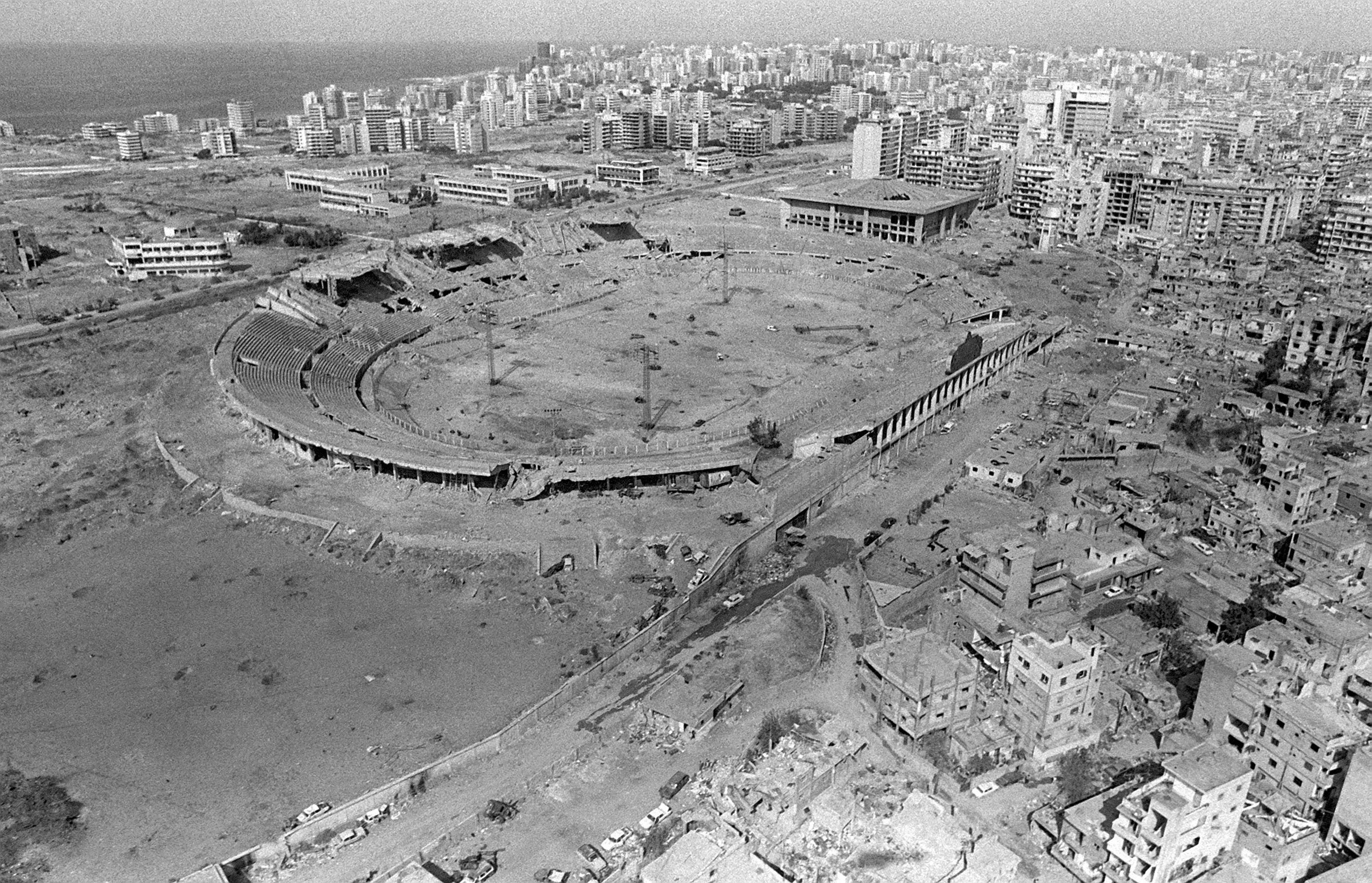

The Lebanese Civil War ( ar, الحرب الأهلية اللبنانية, translit=Al-Ḥarb al-Ahliyyah al-Libnāniyyah) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 120,000 fatalities and an exodus of almost one million people from

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

.

The diversity of the

Lebanese population played a notable role in the lead-up to and during the conflict:

Sunni Muslims and

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

comprised the majority in the coastal cities;

Shia Muslims were primarily based in

the south and the

Beqaa Valley in the east; and

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings o ...

and Christians populated the country's mountainous areas. The Lebanese government had been run under the significant influence of elites within the

Maronite Christian community. The link between politics and religion had been reinforced under the

French Mandate from 1920 to 1943, and the country's parliamentary structure favoured a leading position for

its Christian-majority population. However, the country had a large Muslim population to match, and many

pan-Arabist and

left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy. Left-wing politics typically involve a concern for those in so ...

groups opposed the Christian-dominated pro-

Western government. The influx of thousands of

Palestinians in

1948

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form British ...

and

1967 contributed to the shift of

Lebanon's demography in favour of the Muslim population. The

Cold War had a powerful disintegrative effect on Lebanon, which was closely linked to the

political polarization that preceded the

1958 Lebanese crisis, since Christians sided with the Western world while leftist, Muslim, and pan-Arabist groups sided with

Soviet-aligned

Arab countries.

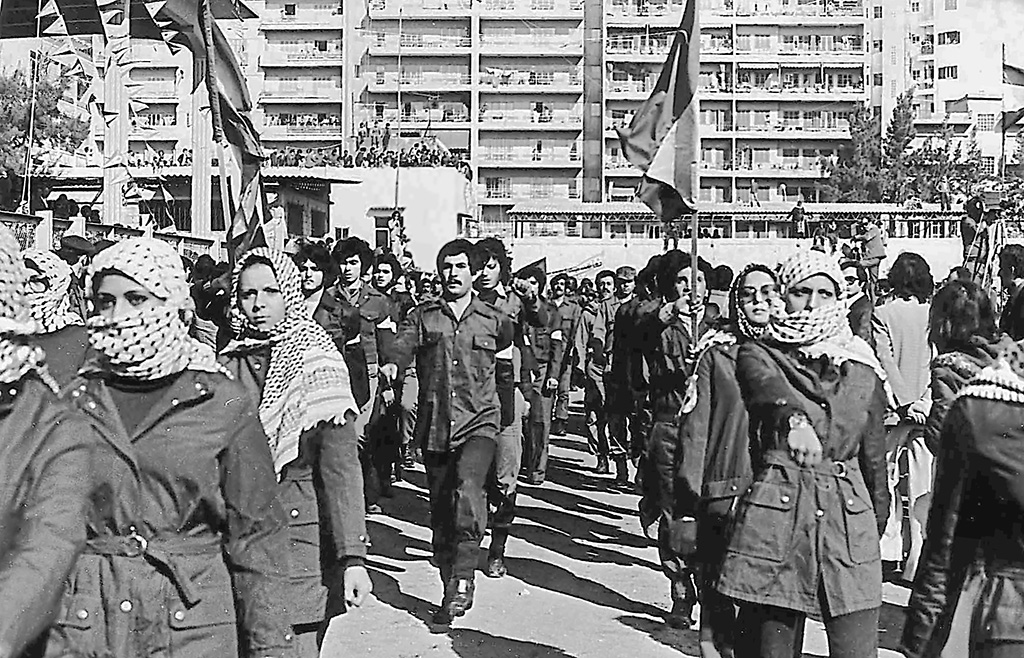

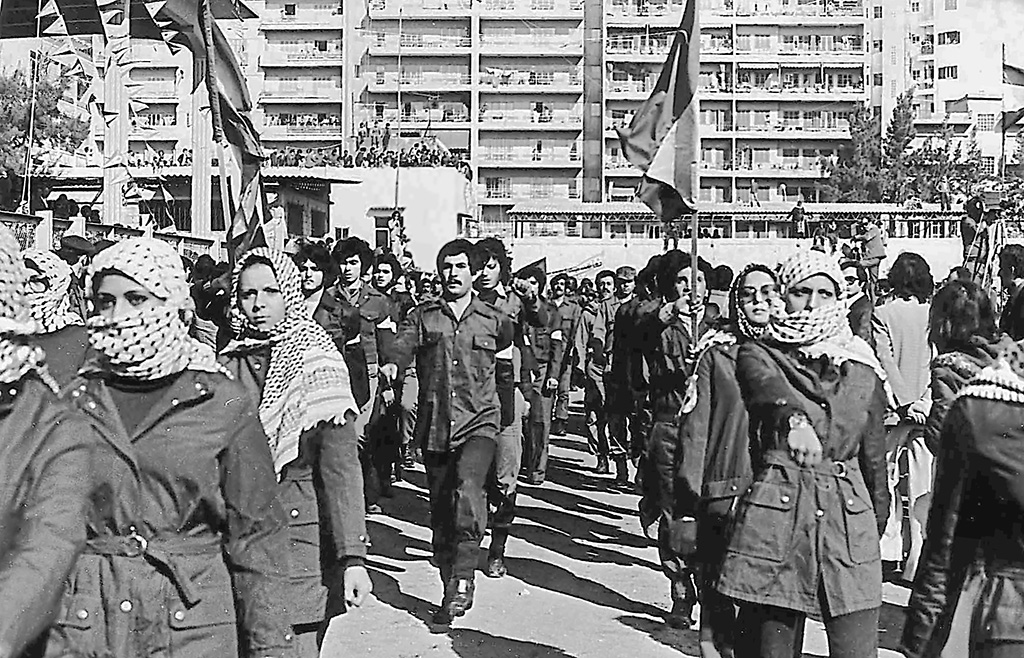

Fighting between Maronite-Christian and Palestinian forces (mainly from the

Palestine Liberation Organization) began in 1975; leftist, Muslim, and pan-Arabist Lebanese groups formed an alliance with the Palestinians in Lebanon. Over the course of the fighting, alliances shifted rapidly and unpredictably. Furthermore, foreign powers, such as

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

and

Syria, became involved in the war and fought alongside different factions. Various peacekeeping forces, such as the

Multinational Force in Lebanon and the

United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon

The United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon ( ar, قوة الأمم المتحدة المؤقتة في لبنان, he, כוח האו"ם הזמני בלבנון), or UNIFIL ( ar, يونيفيل, he, יוניפי״ל), is a UN peacekeeping m ...

, were also stationed in the country during the conflict.

The

Taif Agreement of 1989 marked the beginning of the end of the war. In January 1989, a committee appointed by the

Arab League began to formulate solutions to the conflict. In March 1991, the Lebanese parliament passed an amnesty law that pardoned all political crimes prior to its enactment. In May 1991, all of the militias in Lebanon were dissolved, with the exception of

Hezbollah, while the

Lebanese Armed Forces began to slowly rebuild as Lebanon's only major non-sectarian institution. Religious tensions between Sunnis and Shias remained after the war.

Background

Colonial rule

In 1860 a

civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

between Druze and Maronites erupted in the Ottoman

Mutasarrifate of

Mount Lebanon, which had been divided between them in 1842. The war resulted in the massacre of about 10,000 Christians and at least 6,000 Druzes. The 1860 war was considered by the Druze as a military victory and a political defeat.

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was hard for the Lebanese. While the rest of the world was occupied with the World War, the people in Lebanon were suffering from a

famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenomenon is usually accom ...

that would last nearly four years. With the

defeat and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire (1908–1922), Turkish rule ended.

France took control of the area under the

French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon under the

League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide Intergovernmental organization, intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by ...

. The French created the state of

Greater Lebanon as a safe haven for the Maronites, but included a large Muslim population within the borders. In 1926, Lebanon was declared a republic, and a constitution was adopted. However, the constitution was suspended in 1932. Various factions sought unity with Syria, or independence from the French. In 1934, the country's first (and only to date) census was conducted.

In 1936, the Maronite

Phalange party was founded by

Pierre Gemayel.

Independence

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and the 1940s brought great change to Lebanon and the Middle East. Lebanon was promised independence, which was achieved on 22 November 1943.

Free French troops, who had invaded Lebanon in 1941 to rid Beirut of the

Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its t ...

forces, left the country in 1946. The Maronites assumed power over the country and economy. A parliament was created in which both

Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abra ...

and

Christians

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

each had a set quota of seats. Accordingly, the President was to be a Maronite, the Prime Minister a

Sunni Muslim and the Speaker of Parliament a

Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the ...

Muslim.

The

United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as ...

in late 1947 led to

civil war in Palestine, the end of

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 i ...

, and the

Israeli Declaration of Independence on 14 May 1948. With nationhood, the ongoing civil war was transformed into a state conflict between Israel and the Arab states, the

1948 Arab–Israeli War. All this led to

Palestinian refugees crossing the border into Lebanon. Palestinians would go on to play a very important role in future Lebanese civil conflicts, while the establishment of Israel, radically changed the region around Lebanon.

In July 1958, Lebanon was

threatened by a civil war between

Maronite Christians and Muslims. President

Camille Chamoun had attempted to break the stranglehold on Lebanese politics exercised by traditional political families in Lebanon. These families maintained their electoral appeal by cultivating strong client-patron relations with their local communities. Although he succeeded in sponsoring alternative political candidates to enter the elections in 1957, causing the traditional families to lose their positions, these families then embarked upon a war with Chamoun, referred to as the ''War of the Pashas''.

In previous years, tensions with Egypt had escalated in 1956 when the non-aligned President, Camille Chamoun, did not break off diplomatic relations with the Western powers that attacked Egypt during the

Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

, angering Egyptian President

Gamal Abdel Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-r ...

. This was during the

Cold War and Chamoun has often been called pro-Western, though he had signed several trade deals with the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

(see Gendzier). However, Nasser had attacked Chamoun because of his suspected support for the U.S. led

Baghdad Pact. Nasser felt that the pro-western Baghdad Pact posed a threat to

Arab nationalism. However, president Chamoun looked to regional pacts to ensure protection from foreign armies: Lebanon historically had a small cosmetic army that was never effective in defending Lebanon's territorial integrity, and this is why in later years the PLO guerrilla factions had found it easy to enter Lebanon and set up bases, as well as take over army barracks on the border with Israel as early as 1968. Early skirmishes saw the army not only lose control over its barracks to the PLO but also lost many soldiers. Even prior to this, president Chamoun was aware of the country's vulnerability to outside forces.

But his Lebanese pan-Arabist Sunni Muslim Prime Minister

Rashid Karami supported Nasser in 1956 and 1958. Lebanese Muslims pushed the government to join the newly-created

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

, a country formed out of the unification of Syria and Egypt, while the majority of Lebanese and especially the Maronites wanted to keep Lebanon as an independent nation with its own independent parliament. President Camille feared the toppling of his government and asked for U.S. intervention. At the time the United States was engaged in the

Cold War. Chamoun asked for assistance proclaiming that

Communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, a ...

s were going to overthrow his government. Chamoun was responding not only to the revolt of former political bosses, but also to the fact that both Egypt and Syria had taken the opportunity to deploy proxies into the Lebanese conflict. Thus the

Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), led by

George Habash

George Habash ( ar, جورج حبش, Jūrj Ḥabash), also known by his laqab "al-Hakim" ( ar, الحكيم, al-Ḥakīm, "the wise one" or "the doctor"; 2 August 1926 – 26 January 2008) was a Palestinian Christian politician who founded the ...

and later to become the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) and a faction of the PLO, were deployed to Lebanon by Nasser. The ANM were a clandestine militia implicated in attempted coups against both the Jordanian monarchy and the Iraqi president throughout the 1950s at Nasser's bidding. The founding members of

Fatah, including

Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

and

Khalil Wazir

Khalil Ibrahim al-Wazir Standardized Arabic transliteration: '' / / '' ( ar, خليل إبراهيم الوزير, also known by his '' kunya'' Abu JihadStandardized Arabic transliteration: ' —"Jihad's Father"; 10 October 1935 – 16 April 1 ...

, also flew to Lebanon to use the insurrection as a means by which a war could be fomented toward Israel. They participated in the fighting by directing armed forces against the government security in the city of Tripoli according to

Yezid Sayigh's work.

In that year, President Chamoun was unable to convince the Maronite army commander,

Fuad Chehab, to use the armed forces against Muslim demonstrators, fearing that getting involved in internal politics would split his small and weak multi-confessional force. The

Phalange militia came to the president's aid instead to bring a final end to the road blockades which were crippling the major cities. Encouraged by its efforts during this conflict, later that year, principally through violence and the success of general strikes in Beirut, the Phalange achieved what journalists dubbed the "counterrevolution". By their actions the Phalangists brought down the government of Prime Minister Karami and secured for their leader,

Pierre Gemayel, a position in the four-man cabinet that was subsequently formed.

However, estimates of the Phalange's membership by Yezid Sayigh and other academic sources put them at a few thousand. Non-academic sources tend to inflate the Phalanges membership. What should be kept in mind was that this insurrection was met with widespread disapproval by many Lebanese who wanted no part in the regional politics and many young men aided the Phalange in their suppression of the insurrection, especially as many of the demonstrators were little more than proxy forces hired by groups such as the ANM and Fatah founders as well as being hired by the defeated parliamentary bosses.

Demographic tensions

During the 1960s Lebanon was relatively calm, but this would soon change. Fatah and other Palestinian Liberation Organization factions had long been active among the 400,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanese camps. Throughout the 1960s, the center for armed Palestinian activities had been in Jordan, but they were forced to relocate after being evicted by

King Hussein during the

Black September in Jordan. Fatah and other Palestinian groups had attempted to mount a coup in Jordan by incentivizing a split in the Jordanian army, something that the ANM had attempted to do a decade earlier by Nasser's bidding. Jordan, however, responded and expelled the forces into Lebanon. When they arrived they created "a State within the State". This action was not welcomed by the Lebanese government and this shook Lebanon's fragile sectarian climate.

Solidarity to the Palestinians was expressed through the Lebanese Sunni Muslims but with the aim to change the political system from one of consensus amongst different sects, towards one where their power share would increase. Certain groups in the Lebanese National Movement wished to bring about a more secular and democratic order, but as this group increasingly included Islamist groups, encouraged to join by the PLO, the more progressive demands of the initial agenda was dropped by January 1976. Islamists did not support a secular order in Lebanon and wished to bring about rule by Muslim clerics. These events, especially the role of Fatah and the Tripoli Islamist movement known as Tawhid, in changing the agenda being pursued by many groups, including Communists. This ragtag coalition has often been referred to as left-wing, but many participants were actually very conservative and had religious elements that did not share any broader ideological agenda; rather, they were brought together by the short-term goal of overthrowing the established political order, each motivated by their own grievances.

These forces enabled the PLO / Fatah (Fatah constituted 80% of the membership of the PLO and Fatah guerrillas controlled most of its institutions now) to transform the Western Part of Beirut into its stronghold. The PLO had taken over the heart of Sidon and Tyre in the early 1970s, it controlled great swathes of south Lebanon, in which the indigenous Shiite population had to suffer the humiliation of passing through PLO checkpoints and now they had worked their way by force into Beirut. The PLO did this with the assistance of so-called volunteers from Libya and Algeria shipped in through the ports it controlled, as well as a number of Sunni Lebanese groups who had been trained and armed by PLO/ Fatah and encouraged to declare themselves as separate militias. However, as Rex Brynen makes clear in his publication on the PLO, these militias were nothing more than "shop-fronts" or in Arabic "Dakakin" for Fatah, armed gangs with no ideological foundation and no organic reason for their existence save the fact their individual members were put on PLO/ Fatah payroll.

The strike of fishermen at Sidon in February 1975 could also be considered the first important episode that set off the outbreak of hostilities. That event involved a specific issue: the attempt of former President Camille Chamoun (also head of the Maronite-oriented National Liberal Party) to monopolize fishing along the coast of Lebanon. The injustices perceived by the fishermen evoked sympathy from many Lebanese and reinforced the resentment and antipathy that were widely felt against the state and the economic monopolies. The demonstrations against the fishing company were quickly transformed into a political action supported by the political left and their allies in the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). The state tried to suppress the demonstrators, and a sniper reportedly killed a popular figure in the city, the former Mayor of

Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast ...

,

Maarouf Saad

Maarouf Saad ( ar, معروف سعد) (1910. Maarouf Saad Cultural Center. or 1914–6 March 1975) was a Lebanese politician and activist. He served as Sidon's representative in the Parliament of Lebanon between 1957 and 1972. He founded the P ...

.

Many non-academic sources claim a government sniper killed Saad; however, there is no evidence to support such a claim, and it appears that whoever had killed him had intended that what began as a small and quiet demonstration to evolve into something more. The sniper targeted Saad right at the end of the demonstration as it was dissipating. Farid Khazen, sourcing the local histories of Sidon academics and eyewitnesses, gives a run-down of the puzzling events of the day that based on their research. Other interesting facts that Khazen reveals, based on the Sidon academic's work including that Saad was not in dispute with the fishing consortium made up of Yugoslav nationals. In fact, the Yugoslavian representatives in Lebanon had negotiated with the fisherman's union to make the fishermen shareholders in the company; the company offered to modernize the fishermen's equipment, buy their catch, and give their union an annual subsidy. Saad, as a union representative (and not the mayor of Sidon at the time as many erroneous sources claim), was offered a place on the company's board too. There has been some speculation that Saad's attempts to narrow the differences between the fishermen and the consortium, and his acceptance of a place on the board made him a target of attack by the conspirator who sought a full conflagration around the small protest. The events in Sidon were not contained for long. The government began to lose control of the situation in 1975.

Political groups and militias

In the run-up to the war and its early stages, militias tried to be politically-orientated non-sectarian forces, but due to the sectarian nature of Lebanese society, they inevitably gained their support from the same community as their leaders came from. In the long run almost all militias openly identified with a given community. The two main alliances were the Lebanese Front, consisting of nationalist Maronites who were against Palestinian militancy in Lebanon, and the Lebanese National Movement, which consisted of pro-Palestinian Leftists. The LNM dissolved after the Israeli invasion of 1982 and was replaced by the

Lebanese National Resistance Front, known as ''Jammoul'' in Arabic.

Throughout the war most or all militias operated with little regard for human rights, and the sectarian character of some battles, made

non-combatant civilians a frequent target.

Finances

As the war dragged on, the militias deteriorated ever further into

mafia

"Mafia" is an informal term that is used to describe criminal organizations that bear a strong similarity to the original “Mafia”, the Sicilian Mafia and Italian Mafia. The central activity of such an organization would be the arbitration of ...

-style organizations with many commanders turning to crime as their main occupation rather than fighting. Finances for the war effort were obtained in one or all of three ways:

# Outside support: Notably from

Syria or

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

. Other Arab governments and

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkm ...

also provided considerable funds. Alliances would shift frequently.

# Local population: The militias, and the political parties they served, believed they had legitimate

moral authority to raise taxes to defend their communities. Road checkpoints were a particularly common way to raise these (claimed) taxes. Such taxes were in principle viewed as legitimate by much of the population who identified with their community's militia. However, many militia fighters would use taxes/customs as a pretext to extort money. Furthermore, many people did not recognize militia's tax-raising authority, and viewed all militia money-raising activities as mafia-style extortion and theft.

# Smuggling: During the civil war, Lebanon turned into one of the world's largest

narcotics producers, with much of the

hashish production centered in the

Bekaa valley. However, much else was also smuggled, such as guns and supplies, all kinds of stolen goods, and regular trade – war or no war, Lebanon would not give up its role as the middleman in European-Arab business. Many battles were fought over Lebanon's ports, to gain smugglers access to the sea routes.

Cantons

As central government authority disintegrated and rival governments claimed national authority, the various parties/militias started to create comprehensive state administrations in their territory. These were known as

''cantons'',

Swiss-like autonomous provinces. The best known was "

Marounistan," which was the Phalangist/Lebanese Forces territory. The

Progressive Socialist Party's territory was the "

Civil Administration of the Mountain," commonly known as the ''Jebel-el-Druze'' (a name which had formerly been used for a Druze state in Syria). The Marada area around

Zghorta

Zgharta ( ar, زغرتا, syc, ܙܓܪܬܐ), also spelled Zghorta, is a city in North Lebanon, with an estimated population of around 50,000. It is the second biggest city in Northern Lebanon after Tripoli.

Zgharta is about 150 metres above sea ...

was known as the "

Northern Canton."

Wilton Wynn

Wilton may refer to:

Places Australia

* Wilton, New South Wales, a small town near Sydney

Canada

* Rural Municipality of Wilton No. 472, Saskatchewan

England

*Wilton, Cumbria

*Wilton, Herefordshire

**Wilton Castle

*Wilton, Ryedale, North ...

, a

TIME

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, t ...

correspondent, visited the

East Beirut Christian canton in 1976, the same year as its foundation. He reported that compared to the villages outside of the canton, in Maronite towns and villages no garbage littered the streets, gas was one-fifth the price charged in West Beirut and the price of bread was controlled to levels comparable to pre-war pricing.

Maronite groups

Maronite Christian militias acquired arms from

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

and

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

as well as from West Germany, Belgium and Israel, and drew supporters from the larger Maronite population in the north of the country, they were generally right-wing in their political outlook, and all the major Christian militias were

Maronite-dominated, and other Christian sects played a secondary role.

Initially, the most powerful of the Maronite militias was the National Liberal Party, locally known as "Ahrar", who were politically led by the former president

Camille Chamoun. The NLP had its own militia which was founded in 1968 and led by Camille's son

Dany Chamoun, the

Tigers Militia.

Another party was the

Kataeb Party, or Phalangists, which was founded by

Pierre Gemayel in 1936. Kataeb similarly had its own militia which was officially formed in 1961, the

Kataeb Regulatory Forces led by

William Hawi until 1976 when

Bachir Gemayel succeeded him. Kataeb Regulatory Forces merged with

Tigers Militia and several minor groups (

Al-Tanzim,

Guardians of the Cedars,

Lebanese Youth Movement,

Tyous Team of Commandos) and formed an umbrella militia known as the

Lebanese Forces (LF) which acted in unity, and were politically known as the

Lebanese Front coalition. Before 1975, Maronite militias were reportedly supplied by weapons from

Bulgaria

Bulgaria (; bg, България, Bǎlgariya), officially the Republic of Bulgaria,, ) is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the eastern flank of the Balkans, and is bordered by Romania to the north, Serbia and North Mac ...

, and by the onset of the war were receiving support from

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

,

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

,

Pahlavi Iran,

West Germany

West Germany is the colloquial term used to indicate the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG; german: Bundesrepublik Deutschland , BRD) between its formation on 23 May 1949 and the German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 O ...

, Israel, and

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

, who temporarily cut off their funding after

Black Saturday. This funding enabled the newly formed Lebanese Forces militia to establish itself in Maronite-dominated strongholds, and rapidly transformed from an unorganized and poorly equipped militia into a fearsome armed group that now had its own armor, artillery, commando units (SADM), a small Navy, and a highly advanced Intelligence branch. Meanwhile, in the north, the

Zgharta Liberation Army served as the private militia of the

Franjieh family in

Zgharta, which became allied with Syria after breaking with the

Lebanese Front in 1978.

In 1980, after months of intra Christian clashes, the Tigers militia of Dany Chamoun split with the Lebanese Forces which was dominated by the Kataeb members. Led by Bachir Gemayel, Kataeb launched a surprise attack on the Tigers in what became known as the

Safra massacre, which claimed the lives of up to 83 people, effectively bringing an end to the Tigers as a militia.

In 1985, under the leadership of

Samir Geagea and

Hobeika, the Lebanese Forces split from the Kataeb and other groups to form an independent militia by the name of

Lebanese Forces. The Command Council then elected Hobeika to be LF President, and he appointed Geagea to be LF Chief of Staff. In January 1986, Geagea and Hobeika's relationship broke down over Hobeika's support for the pro-Syrian

Tripartite Accord, and an internal civil war began. The

Geagea-Hobeika Conflict

On January 15, 1986, forces loyal to Lebanese president Amine Gemayel and Samir Geagea, intelligence chief of the Lebanese Forces (LF), ousted Elie Hobeika from his position as leader of the LF and replaced him with Geagea. The coup came in resp ...

resulted in 800 to 1000 casualties before Geagea secured himself as LF leader and Hobeika fled. Hobeika formed the

Lebanese Forces – Executive Command which remained allied with Syria until the end of the war.

Secular groups

Although several Lebanese militias claimed to be

secular, most were little more than vehicles for sectarian interests. Still, there existed a number of non-religious groups, primarily but not exclusively of the left and/or

Pan-Arab right.

Examples of this were the

Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) and the more radical and independent

Communist Action Organization

The Communist Action Organization in Lebanon – CAOL ( ar, منظمة العمل الشيوعي في لبنان , ''munaẓẓamah al-‘amal al-shuyū‘ī fī lubnān''), also known as Organization of Communist Action in Lebanon (OCAL) or Orga ...

(COA). Another notable example was the pan-Syrian

Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP), which promoted the concept of

Greater Syria

Syria ( Hieroglyphic Luwian: 𔒂𔒠 ''Sura/i''; gr, Συρία) or Sham ( ar, ٱلشَّام, ash-Shām) is the name of a historical region located east of the Mediterranean Sea in Western Asia, broadly synonymous with the Levant. Other ...

, in contrast to

Pan-Arab or Lebanese nationalism. The SSNP was generally aligned with the Syrian government, although it did not ideologically approve of the Ba'athist government (however, this has changed recently, under Bashar Al-Assad, the SSNP having been allowed to exert political activity in Syria as well). The multi-confessional SSNP was led by

Inaam Raad Inam ( ar, إنعام ) means ''gift''.

It may be used as a given name for a person. It is mainly female but also male when used in compound forms such as Inam-ul-Haq / Enamul Haque. The name is subject to varying transliterations such as Inaam, ...

, a Catholic and Abdallah Saadeh, a

Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the entire body of Orthodox (Chalcedonian) Christianity, sometimes also call ...

. It was active in North Lebanon (

Koura and

Akkar), West Beirut (around

Hamra Street), in Mount Lebanon (High

Metn,

Baabda,

Aley and

Chouf), in South Lebanon (Zahrani,

Nabatieh,

Marjayoun and

Hasbaya) and the Beqqa Valley (

Baalbeck,

Hermel and

Rashaya).

Another secular group was the

South Lebanon Army (SLA), led by

Saad Haddad. The SLA operated in South Lebanon in coordination with the Israelis, and worked for the Israeli-backed parallel government, called "the Government of Free Lebanon." The SLA began as a split from the

Army of Free Lebanon, a Maronite Christian faction within the

Lebanese Army. Their initial goal was to be a bulwark against PLO raids and attacks into the Galilee, although they later focused on fighting

Hezbollah. The officers tended to be mostly Christians, while the ordinary soldiers were an amalgam of Christians,

Shiites,

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings o ...

and

Sunnis. The SLA continued to operate after the civil war but collapsed after the Israeli army withdrew from South Lebanon in 2000. Many SLA soldiers fled to Israel, while others were captured in Lebanon and prosecuted for collaboration with Israel and treason.

Two competing

Ba'ath movement

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused B ...

s were involved in the early stages of the war: a nationalist one known as

"pro-Iraqi" headed by Abdul-Majeed Al-Rafei (

Sunni) and Nicola Y. Ferzli (

Greek Orthodox Christian), and a Marxist one known as

"pro-Syrian" headed by

Assem Qanso (

Shiite).

The

Kurdistan Workers' Party at the time had training camps in Lebanon, where they received support from the Syrians and the PLO. During the Israeli invasion, all PKK units were ordered to fight the Israeli forces. Eleven PKK fighters died in the conflict.

Mahsum Korkmaz was the commander of all PKK forces in Lebanon.

The Armenian

Marxist-Leninist militia

ASALA was founded in PLO-controlled territory of West Beirut in 1975. This militia was led by revolutionary fighter

Monte Melkonian and group-founder

Hagop Hagopian. Closely aligned with the Palestinians, ASALA fought many battles on the side of the

Lebanese National Movement and the PLO, most prominently against Israeli forces and their right-wing allies during the

1982 phase of the war. Melkonian was field commander during these battles, and assisted the PLO in

its defense of West Beirut.

[Melkonian, Markar (2005). My Brother's Road: An American's Fateful Journey to Armenia. New York: I. B. Tauris. p. x. .]

Palestinians

The

Palestinian movement relocated most of its fighting strength to Lebanon at the end of 1970 after being expelled from

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Ri ...

in the events known as

Black September. The umbrella organization, the

Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)—by itself undoubtedly Lebanon's most potent fighting force at the time—was little more than a loose

confederation

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a union of sovereign groups or states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

, but its leader,

Yassir Arafat, controlled the PLO's largest and most dominant faction,

Fatah, effectively making him the strongman of the PLO. Arafat allowed little oversight to be exercised over PLO finances as he was the ultimate source for all decisions made in directing financial matters. Arafat's control of funds, channeled directly to him by the oil producing countries like

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

,

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, and

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Su ...

meant that he had little real functional opposition to his leadership and although ostensibly rival factions in the PLO existed, this masked a stable loyalty towards Arafat so long as he was able to dispense financial rewards to his followers and members of the PLO guerrilla factions.

Unlike the Lebanese, the Palestinians were not sectarian.

Palestinian Christians similarly supported

Arab Nationalism and fought with their Muslim compatriots against the Maronite Lebanese militias.

The PLO mainstream was represented by Arafat's powerful

Fatah, which waged

guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run ...

but did not have a strong core ideology, except the claim to seek the liberation of Palestine. As a result, they gained broad appeal with a refugee population of moderately conservative Islamic values. The more ideological factions, however, included

George Habash

George Habash ( ar, جورج حبش, Jūrj Ḥabash), also known by his laqab "al-Hakim" ( ar, الحكيم, al-Ḥakīm, "the wise one" or "the doctor"; 2 August 1926 – 26 January 2008) was a Palestinian Christian politician who founded the ...

's Marxist-Leninist

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), and its splinter, the

Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) of

Nayef Hawatmeh. Both Habash and Hawatmeh were Christians.

Fatah was instrumental in splitting the DF from the PFLP in the early days of the PFLPs formation so as to diminish the appeal and competition the PFLP posed to Fatah. Lesser roles were played by the fractious

Palestinian Liberation Front (PLF) and another split-off from the PFLP, the Syrian-aligned

(PFLP-GC). To complicate things, the rival

Ba'athist

Ba'athism, also stylized as Baathism, (; ar, البعثية ' , from ' , meaning "renaissance" or "resurrection"Hans Wehr''Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic'' (4th ed.), page 80) is an Arab nationalist ideology which promotes the creation a ...

countries of Syria and Iraq both set up Palestinian puppet organizations within the PLO. The

as-Sa'iqa was a Syrian-controlled militia, paralleled by the

Arab Liberation Front (ALF) under Iraqi command. The Syrian government could also count on the Syrian brigades of the

Palestine Liberation Army (PLA), formally but not functionally the PLO's regular army. Some PLA units sent by

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

were under Arafat's command.

When the war officially started in 1975, Palestinian armed manpower numbered roughly 21,000, divided into:

Druze groups

The small

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings o ...

sect, strategically and dangerously seated on the

Chouf in central Lebanon, had no natural allies, and so were compelled to put much effort into building alliances. Under the leadership of the

Jumblatt family, first

Kamal Jumblatt (the

LNM leader) and then his son

Walid, the

Progressive Socialist Party

The Progressive Socialist Party ( ar, الحزب التقدمي الاشتراكي, translit=al-Hizb al-Taqadummi al-Ishtiraki) is a Lebanese political party. Its confessional base is in the Lebanese Druze, Druze sect and its regional base is in ...

(PSP) () served as an effective Druze militia, building excellent ties to the Soviet Union mainly, and with Syria upon the withdrawal of Israel to the south of the country. However, many Druze in Lebanon at the time were members of the non-religious party, the Syrian Social Nationalist Party.

Under the leadership of Jumblatt, the PSP was a major element in the Lebanese National Movement (LNM) which supported Lebanon's

Arab identity and sympathized with the Palestinians. Jumblatt built a powerful private militia, the

People's Liberation Army

The People's Liberation Army (PLA) is the principal military force of the People's Republic of China and the armed wing of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The PLA consists of five service branches: the Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, ...

, which was financed by the

USSR

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nation ...

and

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Su ...

, and boasted around 5,000 militiamen at the start of the war, subsequently increasing to 17,000 by early 1984 during the

Mountain War. It conquered much of Mount Lebanon and the Chouf District. Its main adversaries were the Maronite Christian Phalangist militia, and later the Lebanese Forces militia (which absorbed the Phalangists). The PSP suffered a major setback in 1977, when Kamal Jumblatt was assassinated. His son Walid succeeded him as leader of the party.

From the Israeli withdrawal from the Chouf in 1983 to the end of the civil war, the PSP ran a highly effective civil administration, the Civil Administration of the Mountain, in the area under its control. Tolls levied at PSP militia checkpoints provided a major source of income for the administration.

The PSP played an important role in the so-called "Mountain War" under the lead of Walid Jumblatt: after the Israeli Army retreated from the Lebanese Mountain, important battles took place between the PSP and Maronite militias. PSP armed members were accused of several massacres that took place during that war.

The PSP is still an active political party in Lebanon. Its current leader is Walid Jumblatt. It is in practice led and supported mostly by followers of the Druze faith.

Shia Muslim groups

The

Shiites were slow to form and join in the fighting. Shiites comprised Lebanon's disproportionately poorest community, and lacked a communal party that would address Shiite greviances. As a result, Shiites lent their big numbers to a wide variety of parties and organizations.

In the early 1960s–1970s, many Shiites migrated to the

southern suburbs of Beirut, which were known as "poverty belts". Prior 1975, slightly less than half of Shiites lived in Beirut's poverty belts (319,000 out of 668,500). The young Shia migrants joined many organizations, forming the main popular base and nucleus of secular

Leftist and

Pan-Arabist parties and simultaneously filling their rank-and-file; in particular communist parties, so much that a popular saying was "Shi'i, Shuyu'i" (a Shiite, a communist). The attraction was not so much for their secular ideology as much as it was due the lack of an alternative that would address Shia greviances.

Shiites formed 50% of the

LCP LCP may refer to:

Science, medicine and technology

*Large Combustion Plant, see Large Combustion Plant Directive

*Le Chatelier's principle, equilibrium law in chemistry

*Left Circular polarization, in radio communications

* Legg–Calvé–Perthes ...

's membership by 1975, and were overwhelmingly predominant in the

Communist Action Organization

The Communist Action Organization in Lebanon – CAOL ( ar, منظمة العمل الشيوعي في لبنان , ''munaẓẓamah al-‘amal al-shuyū‘ī fī lubnān''), also known as Organization of Communist Action in Lebanon (OCAL) or Orga ...

and the more hardline

ASAP, which advocated violence as the best means to end

class conflict

Class conflict, also referred to as class struggle and class warfare, is the political tension and economic antagonism that exists in society because of socio-economic competition among the social classes or between rich and poor.

The forms ...

.

Shiites also filled the ranks of

Ba'athist

Ba'athism, also stylized as Baathism, (; ar, البعثية ' , from ' , meaning "renaissance" or "resurrection"Hans Wehr''Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic'' (4th ed.), page 80) is an Arab nationalist ideology which promotes the creation a ...

factions, both the pro-Iraqi

SALVP and pro-Syrian

Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party

The Arab Socialist Baʿath Party ( ar, حزب البعث العربي الاشتراكي ' ) was a political party founded in Syria by Mishel ʿAflaq, Ṣalāḥ al-Dīn al-Bītār, and associates of Zaki al-ʾArsūzī. The party espoused B ...

led by Shiite

Assem Qanso, and for a while the Ja'fari school in

Tyre came to be known as a "

Ba'athist

Ba'athism, also stylized as Baathism, (; ar, البعثية ' , from ' , meaning "renaissance" or "resurrection"Hans Wehr''Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic'' (4th ed.), page 80) is an Arab nationalist ideology which promotes the creation a ...

fortress". Many Shiites also joined

Nasserite parties, most notably

al-Mourabitoun which had an estimated 45% Shiite membership as late as 1987, and the

Union of Working People's Forces

The Union of Working People's Forces – UWPF ( ar, اتحاد قوى الشعب العامل , ''Ittihâd qiwâ al-'amal al-cha'b al-'âmil''), also known as Union of Toiling Peoples' Forces (UTPF) or Union des Forces du Peuple Travailleur (UFPT) ...

which established training camps in

Nabatieh; as well as the Syrian nationalist

SSNP

The Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) or is a Syrian nationalist party operating in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine. It advocates the establishment of a Greater Syrian nation state spanning the Fertile Crescent, including presen ...

. Many Shiites also joined Palestinian factions, who set up more than 20 recruitment offices in the Shiite neighborhood of Naba'a, and reportedly constituted sizeable numbers in

Fatah, the

PFLP and

Arab Liberation Front.

Other parties included Jumblatt's

PSP, where Shias formed 20% of the membership as early as 1958, the

Islamic Dawa Party, and to a lesser extent the

NLP and

Kataeb, as Shiites formed 6% of Kataeb's membership in 1969.

For years without their own independent political organizations, there suddenly arose

Musa Sadr's

Amal Movement in 1974–75, which immediately attracted the unrepresented people, including some leftist Shias, and Amal's armed ranks grew rapidly to around 1,500–3,000 by 1975. The radical turnover occurred following the

1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon

The 1982 Lebanon War, dubbed Operation Peace for Galilee ( he, מבצע שלום הגליל, or מבצע של"ג ''Mivtsa Shlom HaGalil'' or ''Mivtsa Sheleg'') by the Israeli government, later known in Israel as the Lebanon War or the First L ...

, when Islamic groups such as

Islamic Amal,

Islamic Jihad Organization,

Imam Husayn Fedayeen

Fedayeen ( ar, فِدائيّين ''fidāʼīyīn'' "self-sacrificers") is an Arabic term used to refer to various military groups willing to sacrifice themselves for a larger campaign.

Etymology

The term ''fedayi'' is derived from Arabic: '' ...

, and eventually

Hezbollah were formed. Hezbollah's main objective was to end Israeli occupation and western influence in Lebanon. By 1984, thousands of Shiites had been enlisted into Hezbollah, as well as most of the important Shiite clergy, including

Ragheb Harb

Ragheb Harb ( ar, راغب حرب; 1952–1984 was a Lebanese leader and Muslim cleric. He was born in Jibchit in 1952, a village in the Jabal Amel region of Southern Lebanon. Harb was an imam and led the regional Shiite resistance against I ...

.

Between 1984 and 1991, there were 3,425 recorded military operations against Israeli forces and the SLA, most of them conducted by Hezbollah.

By the mid to late 1980s, Amal and Hezbollah emerged as the two main Shiite-based political groupings, who grew increasingly competitive over the recruitment of Shiites to their side.

Dahieh, where most Shiites lived, became a hub for recruition and party slogans. Support for Palestinian and Leftist groups declined, and many Shiites who supported other parties moved their support to their communal parties.

Tensions between the two groups arose following Hezbollah's opposition and support of the PLO in the

War of the Camps (1985–1988), and escalated into the

War of Brothers

The War of Brothers ( ar, حرب الأخوة; Harb al-Ikhwa) was a period of violent armed clashes between rivals Amal and Hezbollah, Lebanon's main Shiite militia movements, during the final stages of the Lebanese Civil War. The fighting b ...

between 1988 and 1990. By 1988, armed manpower of the Shia militias was roughly broken into:

The Lebanese

Alawites

The Alawis, Alawites ( ar, علوية ''Alawīyah''), or pejoratively Nusayris ( ar, نصيرية ''Nuṣayrīyah'') are an ethnoreligious group that lives primarily in Levant and follows Alawism, a sect of Islam that originated from Shia Isla ...

, followers of a sect of Shia Islam, were represented by the

Red Knights Militia

The Arab Democratic Party (ADP) ( ar, الحزب العربي الديمقراطي, translit=Al-Hizb Al-'Arabi Al-Dimuqrati) or Parti Démocratique Arabe (PDA) in French, is a Lebanese political party, based in Tripoli, in the North Lebanon Gove ...

of the

Arab Democratic Party, which was pro-Syrian due to the Alawites being dominant in Syria, and mainly acted in Northern Lebanon around

Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

.

Sunni Muslim groups

Some

Sunni factions received support from

Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to the east, Su ...

and

Iraq

Iraq,; ku, عێراق, translit=Êraq officially the Republic of Iraq, '; ku, کۆماری عێراق, translit=Komarî Êraq is a country in Western Asia. It is bordered by Turkey to Iraq–Turkey border, the north, Iran to Iran–Iraq ...

, and a number of minor militias existed due to a general reluctance on the part of Sunnis to join military organisations throughout the civil war. The more prominent groups were secular and holding a

Nasserist

Nasserism ( ) is an Arab nationalist and Arab socialist political ideology based on the thinking of Gamal Abdel Nasser, one of the two principal leaders of the Egyptian Revolution of 1952, and Egypt's second President. Spanning the domestic ...

ideology, or otherwise having

pan-Arab and

Arab nationalist leanings. A few

Islamist ones emerged at later stages of the war, such as the

Tawhid Movement

The Islamic Unification Movement – IUM ( ar, حركة التوحيد الإسلامي , ''Harakat al-Tawhid al-Islami''), also named Islamic Unity Movement or Mouvement d'unification islamique (MUI) in French language, French, but best known as ...

that took its base in Tripoli, and the Jama'a Islamiyya, which gave a Lebanese expression of the

Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar and schoolteacher Hassa ...

in terms of political orientations and practice. The main Sunni-led organization was the

al-Mourabitoun, a major west Beirut based force. They were led by

Ibrahim Kulaylat, fought with the Palestinians against the Israelis during the invasion of 1982. There was also the

Popular Nasserist Organization in

Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast ...

that was formed through the followers of

Maarouf Saad

Maarouf Saad ( ar, معروف سعد) (1910. Maarouf Saad Cultural Center. or 1914–6 March 1975) was a Lebanese politician and activist. He served as Sidon's representative in the Parliament of Lebanon between 1957 and 1972. He founded the P ...

, and who rallied later behind his son Mustafa Saad, and now are led by Usama Saad. The

Sixth of February Movement

The Sixth of February Movement or '6th FM' (Arabic: حركة السادس من فبراير , ''Harakat al-Sadis min Fibrayir''), also known as Mouvement du 6 février in French, was a small, predominantly Sunni Nasserist political party and mi ...

was another pro-Palestinian Nasserist minor militia that sided with the PLO in the

War of the Camps in the 1980s.

Armenian groups

The

Armenian parties tended to be Christian by religion and left-wing in outlook, and were therefore uneasy committing to either side of the fighting. As a result, the Armenian parties attempted, with some success, to follow a policy of militant neutrality, with their militias fighting only when required to defend the Armenian areas. However, it was not uncommon for individual Armenians to choose to fight in the Lebanese Forces, and a small number chose to fight on the other side for the

Lebanese National Movement/

Lebanese National Resistance Front.

The Beirut suburbs of Bourj Hamoud and Naaba were controlled by the Armenian

Dashnak

The Armenian Revolutionary Federation ( hy, Հայ Յեղափոխական Դաշնակցութիւն, ՀՅԴ ( classical spelling), abbr. ARF or ARF-D) also known as Dashnaktsutyun (collectively referred to as Dashnaks for short), is an Armenian ...

party. In September 1979, these were attacked by the

Kataeb in an attempt to bring all Christian areas under

Bashir Gemayel's control. The Armenian Dashnak militia defeated the Kataeb attacks and retained control. The fighting led to 40 deaths.

The

Armenian Revolutionary Federation in Lebanon refused to take sides in the conflict though its armed wing the

Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide

Justice Commandos of the Armenian Genocide (JCAG) ( hy, Հայկական Ցեղասպանութեան Արդարութեան Մարտիկներ, ՀՑԱՄ) was an Armenian militant organization active from 1975 to 1987.

JCAG conducted an interna ...

and the

Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia did carry out assassinations and operations during the war.

Chronology

First phase, 1975–77

Sectarian violence and massacres

Throughout the spring of 1975, minor clashes in

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to Lebanon–Syria border, the north and east and Israel to Blue ...

had been building up towards all-out conflict, with the

Lebanese National Movement (LNM) pitted against the

Phalange, and the ever-weaker national government wavering between the need to maintain order and cater to its constituency. On the morning of 13 April 1975, unidentified gunmen in a speeding car fired on a church in the Christian

East Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

suburb of Ain el-Rummaneh, killing four people, including two

Maronite Phalangists. Hours later, Phalangists led by the

Gemayels killed 30

Palestinians traveling in Ain el-Rummaneh. Citywide clashes erupted in response to this "

Bus Massacre". The

Battle of the Hotels began in October 1975, and lasted until March in 1976.

On 6 December 1975, a day later known as

Black Saturday, the killings of four

Phalange members led Phalange to quickly and temporarily set up

roadblocks throughout

Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

at which identification cards were inspected for religious affiliation. Many Palestinians or Lebanese Muslims passing through the roadblocks were killed immediately. Additionally, Phalange members took hostages and attacked Muslims in East Beirut. Muslim and Palestinian militias retaliated with force, increasing the total death count to between 200 and 600 civilians and militiamen. After this point, all-out fighting began between the militias.

On 18 January 1976 an estimated 1,000–1,500 people were killed by Maronite forces in the

Karantina Massacre, followed two days later by a

retaliatory strike on Damour by Palestinian militias. These two massacres prompted a mass exodus of Muslims and Christians, as people fearing retribution fled to areas under the control of their own sect. The ethnic and religious layout of the residential areas of the capital encouraged this process, and East and

West Beirut were increasingly transformed into what was in effect Christian and Muslim Beirut. Also, the number of Maronite

leftists who had allied with the LNM, and Muslim conservatives with the government, dropped sharply, as the war revealed itself as an utterly sectarian conflict. Another effect of the massacres was to bring in

Yassir Arafat's well-armed

Fatah and thereby the

Palestine Liberation Organisation on the side of the LNM, as Palestinian sentiment was by now completely hostile to the Maronite forces.

Syrian intervention

On 22 January 1976, Syrian President Hafez al-Assad brokered a truce between the two sides, while covertly beginning to move Syrian troops into Lebanon under the guise of the

Palestine Liberation Army in order to bring the PLO back under Syrian influence and prevent the disintegration of Lebanon. Despite this, the violence continued to escalate. In March 1976, Lebanese President Suleiman Frangieh requested that Syria formally intervene. Days later, Assad sent a message to the United States asking them not to interfere if he were to send troops into Lebanon.

On 8 May 1976, Elias Sarkis, who was supported by Syria, defeated Frangieh in a presidential election held by the Lebanese Parliament. However, Frangieh refused to step down. On 1 June 1976, 12,000 regular Syrian troops entered Lebanon and began conducting operations against Palestinian and leftist militias. This technically put Syria on the same side as

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

, as Israel had already begun to supply Maronite forces with arms, tanks, and military advisers in May 1976. Syria had its own political and territorial interests in Lebanon, which harbored cells of Sunni

Islamists and anti-Ba'athist

Muslim Brotherhood

The Society of the Muslim Brothers ( ar, جماعة الإخوان المسلمين'' ''), better known as the Muslim Brotherhood ( ', is a transnational Sunni Islamist organization founded in Egypt by Islamic scholar and schoolteacher Hassa ...

.

Since January, the Tel al-Zaatar refugee camp in East Beirut had been under siege by Maronite Christian militias. On 12 August 1976, supported by Syria, Maronite forces managed to overwhelm the Palestinian and leftist militias defending the camp. The Christian militia massacred 1,000–1,500 civilians, which unleashed heavy criticism against Syria from the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

.

On 19 October 1976, the Battle of Aishiya took place, when a combined force of

PLO

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establishing Arab unity and s ...

and a Communist militia attacked Aishiya, an isolated Maronite village in a mostly Muslim area. The Artillery Corps of the Israel Defense Forces fired 24 shells (66 kilograms of TNT each) from US-made 175-millimeter field artillery units at the attackers, repelling their first attempt. However, the PLO and Communists returned at night, when low visibility made Israeli artillery far less effective. The Maronite population of the village fled. They returned in 1982.

In October 1976, Syria accepted the proposal of the

Arab League summit in

Riyadh

Riyadh (, ar, الرياض, 'ar-Riyāḍ, Literal translation, lit.: 'The Gardens' Najdi Arabic, Najdi pronunciation: ), formerly known as Hajr al-Yamamah, is the capital and largest city of Saudi Arabia. It is also the capital of the Riyad ...

. This gave Syria a mandate to keep 40,000 troops in Lebanon as the bulk of an

Arab Deterrent Force charged with disentangling the combatants and restoring calm. Other Arab nations were also part of the ADF, but they lost interest relatively soon, and Syria was again left in sole control, now with the ADF as a diplomatic shield against international criticism. The Civil War was officially paused at this point, and an uneasy quiet settled over Beirut and most of the rest of Lebanon. In the south, however, the climate began to deteriorate as a consequence of the gradual return of PLO combatants, who had been required to vacate central Lebanon under the terms of the Riyadh Accords.

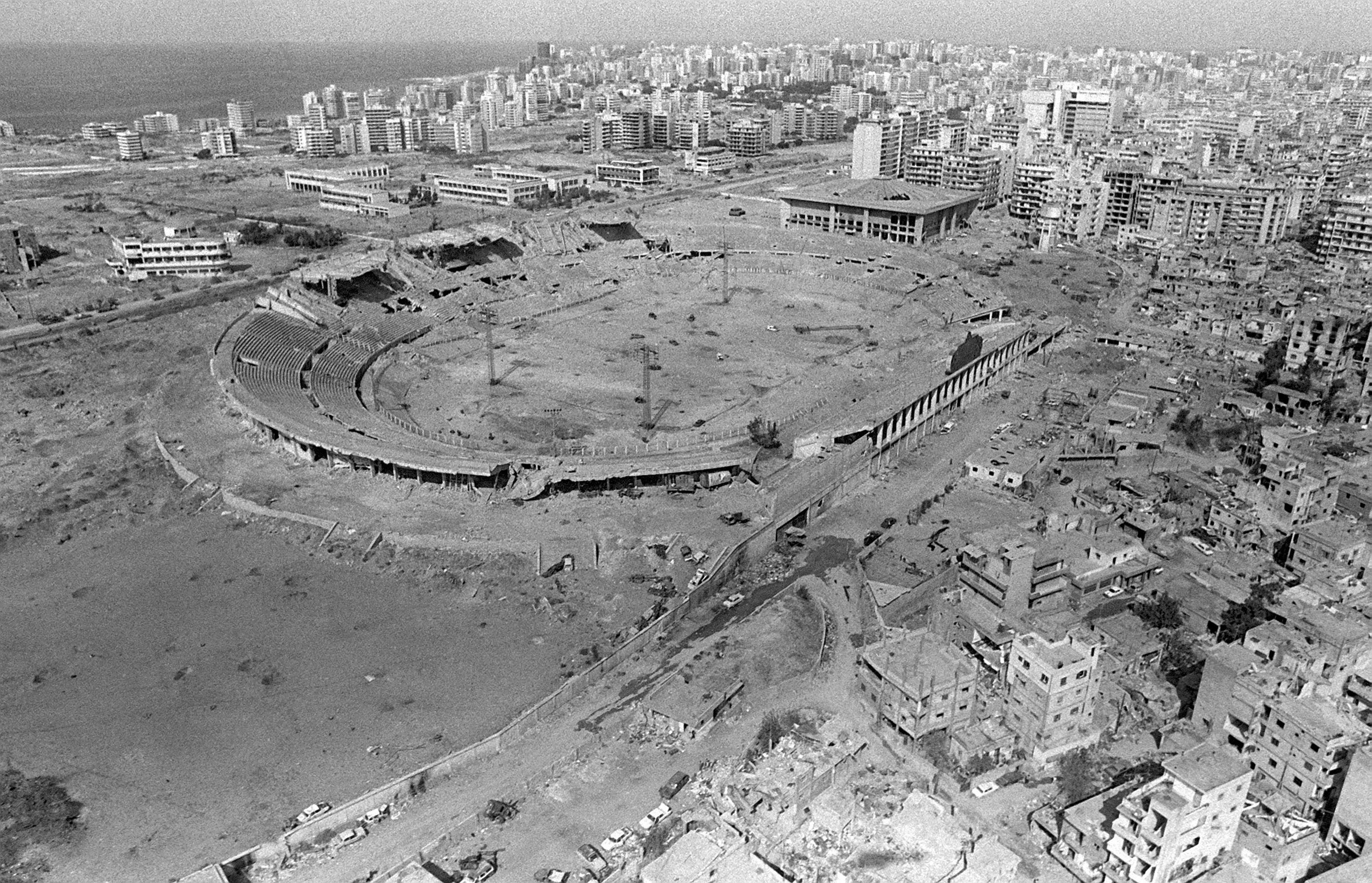

During 1975–1977, 60,000 people were killed.

Uneasy quiet

The nation was now effectively divided, with southern Lebanon and the western half of Beirut becoming bases for the PLO and Muslim-based militias, and the Christians in control of East Beirut and the Christian section of

Mount Lebanon. The main confrontation line in divided Beirut was known as the

Green Line

Green Line may refer to:

Places Military and political

* Green Line (France), the German occupation line in France during World War II

* Green Line (Israel), the 1949 armistice line established between Israel and its neighbours

** City Line ( ...

.

In East Beirut, in 1976, Maronite leaders of the

National Liberal Party (NLP), the

Kataeb Party and the

Lebanese Renewal Party joined in the

Lebanese Front, a political counterpoint to the LNM. Their militias – the

Tigers,

Kataeb Regulatory Forces (KRF) and

Guardians of the Cedars – entered a loose coalition known as the

Lebanese Forces, to form a military wing for the Lebanese Front. From the very beginning, the Kataeb and its Regulatory Forces' militia, under the leadership of

Bashir Gemayel, dominated the LF. In 1977–80, through absorbing or destroying smaller militias, he both consolidated control and strengthened the LF into the dominant Maronite force.

In March the same year,

Lebanese National Movement leader

Kamal Jumblatt was assassinated. The murder was widely blamed on the Syrian government. While Jumblatt's role as leader of the

Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings o ...

Progressive Socialist Party

The Progressive Socialist Party ( ar, الحزب التقدمي الاشتراكي, translit=al-Hizb al-Taqadummi al-Ishtiraki) is a Lebanese political party. Its confessional base is in the Lebanese Druze, Druze sect and its regional base is in ...

was filled surprisingly smoothly by his son,

Walid Jumblatt, the LNM disintegrated after his death. Although the anti-government pact of leftists, Shi'a, Sunni, Palestinians and Druze would stick together for some time more, their wildly divergent interests tore at opposition unity. Sensing the opportunity,

Hafez al-Assad

Hafez al-Assad ', , (, 6 October 1930 – 10 June 2000) was a Syrian statesman and military officer who served as President of Syria from taking power in 1971 until his death in 2000. He was also Prime Minister of Syria from 1970 to 19 ...

immediately began splitting up both the Maronite and Muslim coalitions in a game of divide and conquer.

Second phase, 1977–82

Hundred Days War

The

Hundred Days War

The Hundred Days War ( ar, حرب المئة يوم, ''Harb Al-Mia'at Yaoum,'' French: La Guerre des Cent Jours) was a subconflict within the 1977–82 phase of the Lebanese Civil War which occurred in the Lebanese capital Beirut. It was foug ...

was a sub-conflict within the Lebanese Civil War, which occurred in the Lebanese capital

Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

between February and April 1978.

The only political person who remained in East Beirut Achrafiyeh all the 100 days was the president Camille Chamoun, and refused to get out of the area. It was fought between the Maronite, and the Syrian troops of the

Arab Deterrent Force (ADF). The Syrian troops shelled the Christian Beirut area of Achrafiyeh for 100 days. The conflict resulted in

Syrian Army's expulsion from East Beirut, the end of

Arab Deterrent Force's task in Lebanon and revealed the true intentions of the Syrians in Lebanon. The conflict resulted in 160 dead and 400 injured.

1978 South Lebanon conflict

PLO attacks from Lebanon into Israel in 1977 and 1978 escalated tensions between the countries. On 11 March 1978, eleven Fatah fighters landed on a beach in northern Israel and proceeded to hijack two buses full of passengers on the Haifa – Tel-Aviv road, shooting at passing vehicles in what became known as the

Coastal Road massacre. They killed 37 and wounded 76 Israelis before being killed in a firefight with Israeli forces. Israel invaded Lebanon four days later in

Operation Litani. The

Israeli Army occupied most of the area south of the

Litani River. The

UN Security Council passed

Resolution 425

United Nations Security Council Resolution 425, adopted on 19 March 1978, five days after the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in the context of Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon and the Lebanese Civil War, called on Israel to withdraw immedi ...

calling for immediate Israeli withdrawal and creating the

UN Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), charged with attempting to establish peace.

Security Zone

Israeli forces withdrew later in 1978, but retained control of the southern region by managing a wide security zone along the border. These positions were held by the

South Lebanon Army (SLA), a Christian-Shi'a militia under the leadership of Major

Saad Haddad backed by Israel. The Israeli Prime Minister,

Likud

Likud ( he, הַלִּיכּוּד, HaLikud, The Consolidation), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement, is a major centre-right to right-wing political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Shar ...

's

Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'' (); pl, Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ''Menakhem Volfovich Begin''; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. ...

, compared the plight of the Christian minority in southern Lebanon (then about 5% of the population in SLA territory) to that of European Jews during World War II. The PLO routinely

attacked Israel during the period of the cease-fire, with over 270 documented attacks. People in Galilee regularly had to leave their homes during these shellings. Documents captured in PLO headquarters after the invasion showed they had come from Lebanon. Arafat refused to condemn these attacks on the grounds that the cease-fire was only relevant to Lebanon.

Between June and August 1979 the IDF increased its artillery bombardments and air strikes on targets in Southern Lebanon resulting in the killing of around forty people and a mass exodus of civilians. On 27 June four

Syrian planes were shot down over Southern Lebanon. One of them reportedly hit by Palestinian ground fire.

In April 1980 the presence of UNIFIL soldiers in the buffer zone led to the

At Tiri incident.

Day of the Long Knives

The

Safra massacre, known as the ''Day of the Long Knives'', occurred in the

coast

The coast, also known as the coastline or seashore, is defined as the area where land meets the ocean, or as a line that forms the boundary between the land and the coastline. The Earth has around of coastline. Coasts are important zones in n ...

al town Safra (north of

Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

) on 7 July 1980, as part of

Bashir Gemayel's effort to consolidate all the Maronite fighters under his leadership in the

Lebanese Forces. The

Phalangist forces launched a surprise attack on the

Tigers Militia, which claimed the lives of 83 people, most of whom were normal citizens and not from the militia.

Zahleh campaign

The first six months of 1981 brought Lebanon some of the worst violence since 1976. In the South, there was an increase in clashes between the

Antoine Haddad’s rebel militia and

UNIFIL. This followed an agreement reached in

Damascus between Lebanese President

Élias Sarkis and

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

officials on the deployment of

Lebanese army soldiers into areas where UNIFIL forces where stationed. The agreement, which was reached in early March, was rejected by Haddad. On 16 March three

Nigerian

Nigerians or the Nigerian people are citizens of Nigeria or people with ancestry from Nigeria. The name Nigeria was taken from the Niger River running through the country. This name was allegedly coined in the late 19th century by British jour ...

soldiers serving with UNIFIL were killed by artillery fire from Haddad’s forces.

Another factor was political activity in Israel ahead of elections in June which Prime Minister

Menachem Begin

Menachem Begin ( ''Menaḥem Begin'' (); pl, Menachem Begin (Polish documents, 1931–1937); ''Menakhem Volfovich Begin''; 16 August 1913 – 9 March 1992) was an Israeli politician, founder of Likud and the sixth Prime Minister of Israel. ...

and his

Likud

Likud ( he, הַלִּיכּוּד, HaLikud, The Consolidation), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement, is a major centre-right to right-wing political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Shar ...

party were expected to lose. Begin publicly acknowledged that Israel had an alliance with

Bashir Gemayel’s

Phalange militia and would intervene if the

Syrian Army attacked them. Defence Minister

Rafael Eitan visited

Jounieh on several occasions. In South Lebanon there were regular

airstrikes

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, fighters, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopters and drones. The offi ...

around

Nabatieh and

Beaufort Castle. On the night of 9 April

IDF commandos raided five different

PLO

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establishing Arab unity and s ...

positions in the South.

In Beirut sniper fire across the

Green Line

Green Line may refer to:

Places Military and political

* Green Line (France), the German occupation line in France during World War II

* Green Line (Israel), the 1949 armistice line established between Israel and its neighbours

** City Line ( ...

between East and West Beirut increased, climaxing in April with lengthy artillery exchanges. The main combatants were elements of the Lebanese Army and the Syrian

ADF.

Across the

mountains in

Zahleh, the

Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

town on the Western edge of the

Beqaa Valley, the

Phalangist militia had become dominant and were reinforcing outposts with artillery as well as opening a new road to the coast and their heartland. In early April clashes escalated around the town and the Syrian Army imposed a siege. There were also outbreaks of fighting in neighbouring

Baalbek.

Meanwhile in the South, on 19 April, Haddad’s militia shelled

Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast ...

, killing sixteen civilians. Some reports stated that the attack was in response to a request from

Bashir Gemayel in order to relieve the Syrian pressure on the Phalangists in Zahleh. On 27 April Syrian troops launched an offensive against the Phalagists' mountain outposts. The following day the

Israeli Air Force

The Israeli Air Force (IAF; he, זְרוֹעַ הָאֲוִיר וְהֶחָלָל, Zroa HaAvir VeHahalal, tl, "Air and Space Arm", commonly known as , ''Kheil HaAvir'', "Air Corps") operates as the aerial warfare branch of the Israel Defense ...