Koch–Pasteur Rivalry on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The French

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880

In 1883, responding to a

In 1883, responding to a

"Louis Pasteur"

''History Learning Site'', 2000–2011, Web. (Even without vaccination, not everyone bitten by a rabid dog develops rabies.) After other apparently successful cases, donations poured in from across the globe, funding the establishment of the

"Pasteur Institutes USA: A turn-of-the-century phenomenon"

, ''Remembrance of Things Pasteur'', Accessed 5 Sep 2012 on Web. A number of American copycats appeared, however, starting with "Chicago Pasteur Institute" in 1890, and "New York Pasteur Institute" in 1891. In 1897 a "Pasteur Institute" opened in

"Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Global Health & Novel Intervention Strategies"

, Institute of Medicine of National Academies, Apr 2010.

Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist, pharmacist, and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, Fermentation, microbial fermentation, and pasteurization, the la ...

(1822–1895) and German Robert Koch

Heinrich Hermann Robert Koch ( ; ; 11 December 1843 – 27 May 1910) was a German physician and microbiologist. As the discoverer of the specific causative agents of deadly infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and anthrax, he i ...

(1843–1910) are the two greatest figures in medical microbiology

Medical microbiology, the large subset of microbiology that is applied to medicine, is a branch of medical science concerned with the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of infectious diseases. In addition, this field of science studies various ...

and in establishing acceptance of the germ theory of disease

The germ theory of disease is the currently accepted scientific theory for many diseases. It states that microorganisms known as pathogens or "germs" can cause disease. These small organisms, which are too small to be seen without magnification, ...

(germ theory). In 1882, fueled by national rivalry and a language barrier, the tension between Pasteur and the younger Koch erupted into an acute conflict.

Pasteur had already discovered molecular chirality

Chirality () is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is distinguishable fro ...

, investigated fermentation

Fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolism which harnesses the redox potential of the reactants to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and organic end products. Organic molecules, such as glucose or other sugars, are catabolized and reduce ...

, refuted spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation is a superseded scientific theory that held that living creatures could arise from non-living matter and that such processes were commonplace and regular. It was hypothesized that certain forms, such as fleas, could ...

, inspired Lister's introduction of antisepsis

An antiseptic ( and ) is an antimicrobial substance or compound that is applied to living tissue to reduce the possibility of sepsis, infection, or putrefaction. Antiseptics are generally distinguished from ''antibiotics'' by the latter's abili ...

to surgery, introduced pasteurization

In food processing, pasteurization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), also pasteurisation) is a process of food preservation in which packaged foods (e.g., milk and fruit juices) are treated wi ...

to France's wine industry, answered the silkworm

''Bombyx mori'', commonly known as the domestic silk moth, is a moth species belonging to the family Bombycidae. It is the closest relative of '' Bombyx mandarina'', the wild silk moth. Silkworms are the larvae of silk moths. The silkworm is of ...

diseases blighting France's silkworm industry, attenuate

In physics, attenuation (in some contexts, extinction) is the gradual loss of flux intensity through a medium. For instance, dark glasses attenuate sunlight, lead attenuates X-rays, and water and air attenuate both light and sound at variable at ...

d a ''Pasteurella

__NOTOC__

''Pasteurella'' is a genus of Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacteria. ''Pasteurella'' species are non motile and pleomorphic, and often exhibit bipolar staining ("safety pin" appearance). Most species are catalase- and oxidas ...

'' species of bacteria to develop vaccine to chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis and avian hemorrhagic septicemia.K. R. Rhoades and R. B. Rimler, Avian pasteurellosis, in "Diseases of poultry", ed. by M. S. Hofstad, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa , p. 141 ...

(1879), and introduced anthrax vaccine

Anthrax vaccines are vaccines to prevent the livestock and human disease anthrax, caused by the bacterium ''Bacillus anthracis''.

They have had a prominent place in the history of medicine, from Pasteur's pioneering 19th-century work with cattle ...

(1881).

Koch had transformed bacteriology

Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the Morphology (biology), morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the iden ...

by introducing the technique of pure culture

A microbiological culture, or microbial culture, is a method of multiplying microbial organisms by letting them reproduce in predetermined culture medium under controlled laboratory conditions. Microbial cultures are foundational and basic diag ...

, whereby he established the microbial cause of the disease anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis'' or ''Bacillus cereus'' biovar ''anthracis''. Infection typically occurs by contact with the skin, inhalation, or intestinal absorption. Symptom onset occurs between one ...

(1876), had introduced both staining and solid culture plates to bacteriology (1881), had identified the microbial cause of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

(1882), had incidentally popularized Koch's postulates

Koch's postulates ( ) are four criteria designed to establish a causality, causal relationship between a microbe and a disease. The postulates were formulated by Robert Koch and Friedrich Loeffler in 1884, based on earlier concepts described by ...

for identifying the microbial cause of a disease, and would later identify the microbial cause of cholera (1883).

Although Koch had briefly and, thereafter, his bacteriological followers regarded a bacterial species' properties as unalterable, Pasteur's modification of virulence to develop vaccine demonstrated this doctrine's falsity. At an 1882 conference, a mistranslated term from French to German during Pasteur's lecture triggered Koch's indignation, whereupon Koch's two bacteriologist colleagues, Friedrich Loeffler

Friedrich August Johannes Loeffler (; 24 June 18529 April 1915) was a German bacteriologist at the University of Greifswald.

Biography

He obtained his M.D. degree from the University of Berlin in 1874. He worked with Robert Koch from 1879 to 188 ...

and Georg Gaffky, published denigration of the entirety of Pasteur's research on anthrax since 1877.

Tensions between France and Germany

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the

Germany had unified by way of its victory in the Franco-Prussian War

The Franco-Prussian War or Franco-German War, often referred to in France as the War of 1870, was a conflict between the Second French Empire and the North German Confederation led by the Kingdom of Prussia. Lasting from 19 July 1870 to 28 Janua ...

(1870–71), seizing Alsace-Lorraine from France. Pasteur was professor in the University of Strasbourg

The University of Strasbourg (, Unistra) is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Johannes Sturm, it was a center of intellectual life during ...

, located in Alsace, where he married the daughter of the rector. Jean Baptiste Pasteur, the only son of Louis and Marie Pasteur, was a soldier in the Franco-Prussian War. The tone set by this war contributed to the rivalry between Koch and Pasteur. The "German Problem", as Germany increasingly gained scientific, technological, and industrial dominance, fed tensions among European nations. Germ theory's applications were embedded in the heightening quest by France, Germany, Britain, and Italy to colonize Africa and Asia with the aid of tropical medicine

Tropical medicine is an interdisciplinary branch of medicine that deals with health issues that occur uniquely, are more widespread, or are more difficult to control in tropical and subtropical regions.

Physicians in this field diagnose and tr ...

, a new variant of colonial medicine, while medical scientist

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for patients, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care practic ...

s in respective nations vied to lead advances.

Koch's bacteriology and anthrax

In 1863, influenced by Pasteur's research on fermentation, fellow FrenchmanCasimir Davaine

Casimir-Joseph Davaine (19 March 1812 – 14 October 1882) was a French physician known for his work in the field of microbiology. He was a native of Saint-Amand-les-Eaux, department of Nord.

In 1850, Davaine along with French pathologist Pier ...

mostly explained the cause of anthrax, but Davaine's explanation was opposed by those who opposed the idea that infection with a microorganism could explain it. In 1840, Jakob Henle

Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle (; 9 July 1809 – 13 May 1885) was a German physician, pathologist, and anatomist. He is credited with the discovery of the loop of Henle in the kidney. His essay, "On Miasma and Contagia," was an early argument for ...

had proposed microorganism infections caused diseases, and in 1875 German botanist Ferdinand Cohn

Ferdinand Julius Cohn (24 January 1828 – 25 June 1898) was a German biologist. He is one of the founders of modern bacteriology and microbiology.

Biography

Ferdinand Julius Cohn was born in the Jewish quarter of Breslau in the Prussian Pro ...

weighed in on a controversy in microbiology by declaring that the elementary unit was the cell and that each form of bacteria was constant and naturally divided from the other forms. Influenced by Henle and by Cohn, Koch developed a pure culture

A microbiological culture, or microbial culture, is a method of multiplying microbial organisms by letting them reproduce in predetermined culture medium under controlled laboratory conditions. Microbial cultures are foundational and basic diag ...

of the bacteria described by Davaine, traced its spore stage, inoculated it into animals, and showed it caused anthrax. Pasteur called this a "remarkable achievement". In pure culture, bacteria tend to keep constant traits, and Koch reported having already observed constancy.

Pasteur undertook investigation, yet gave much credit to Davaine. Meanwhile, Pasteur's researchers always reported variation in their cultures. In 1879, Henri Toussaint identified a bacterial species involved in chicken cholera

Fowl cholera is also called avian cholera, avian pasteurellosis and avian hemorrhagic septicemia.K. R. Rhoades and R. B. Rimler, Avian pasteurellosis, in "Diseases of poultry", ed. by M. S. Hofstad, Iowa State University Press, Ames, Iowa , p. 141 ...

and named the genus in honor of Pasteur, ''Pasteurella

__NOTOC__

''Pasteurella'' is a genus of Gram-negative, facultatively anaerobic bacteria. ''Pasteurella'' species are non motile and pleomorphic, and often exhibit bipolar staining ("safety pin" appearance). Most species are catalase- and oxidas ...

''. In Pasteur's laboratory, a culture of ''Pasteurella multocida

''Pasteurella multocida'' is a Gram-negative, nonmotile, penicillin-sensitive coccobacillus of the family Pasteurellaceae. Strains of the species are currently classified into five serogroups (A, B, D, E, F) based on capsular composition and 16 ...

'' was left out over a weekend exposed to air, and Pasteur and Emile Roux

Emile or Émile may refer to:

* Émile (novel) (1827), autobiographical novel based on Émile de Girardin's early life

* Emile, Canadian film made in 2003 by Carl Bessai

* '' Emile: or, On Education'' (1762) by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, a treatise o ...

noticed upon return to the laboratory that its virulence to chickens was diminished. Pasteur applied the discovery to develop chicken cholera vaccine, introduced in a public experiment, an empirical challenge to the stance of Koch's bacteriologists that bacterial traits were unalterable.

Pasteur's attenuation and vaccines

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880

From 1878 to 1880, when publishing on anthrax, Pasteur referred to the bacteria by the name given it by Frenchman Davaine, but in one footnote called it "''Bacillus anthracis'' of the Germans". In July 1880 Toussaint

''Toussaint'' (French for All Saints' Day, literally: "All Saints") may refer to:

* Toussaint (name)

* Toussaint, Seine-Maritime, a commune in the arrondissement of Le Havre in the Seine-Maritime département of France

* Toussaint hierarchy, a mat ...

reported developing a technique of chemical deactivation to produce anthrax vaccine that successfully protected dogs and cattle, and was praised by the Academy of Science, but Pasteur attacked the feat—chemical deactivation and not virulence attenuation to make a vaccine—as impossible. Pasteur soon introduced his own anthrax vaccine in a highly successful public experiment, and entered commerce with it. Pasteur was criticized by Koch and colleagues. (Pasteur had not used attenuation, but secretly used Toussaint's technique.)

Microbe hunting, cholera, and public health

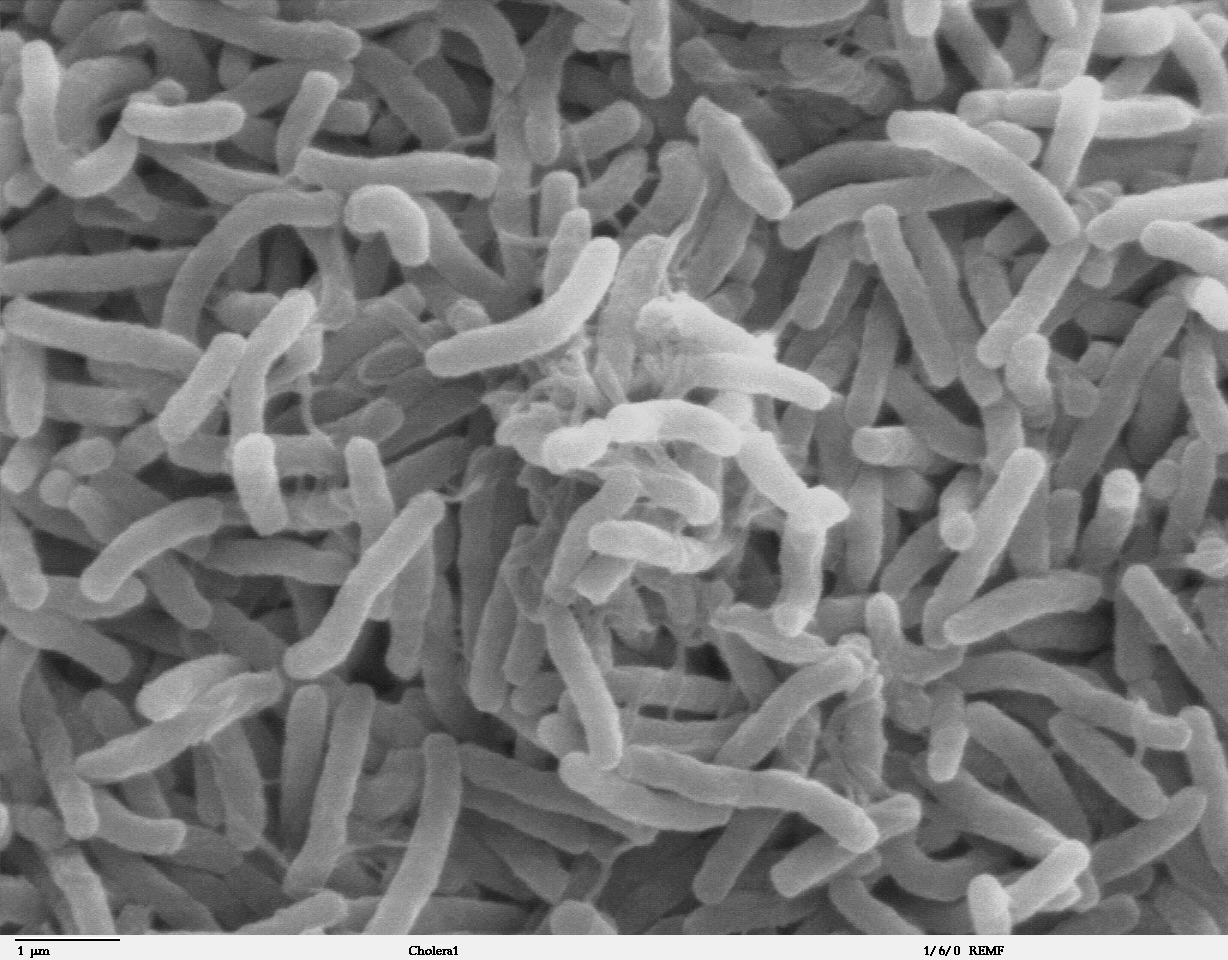

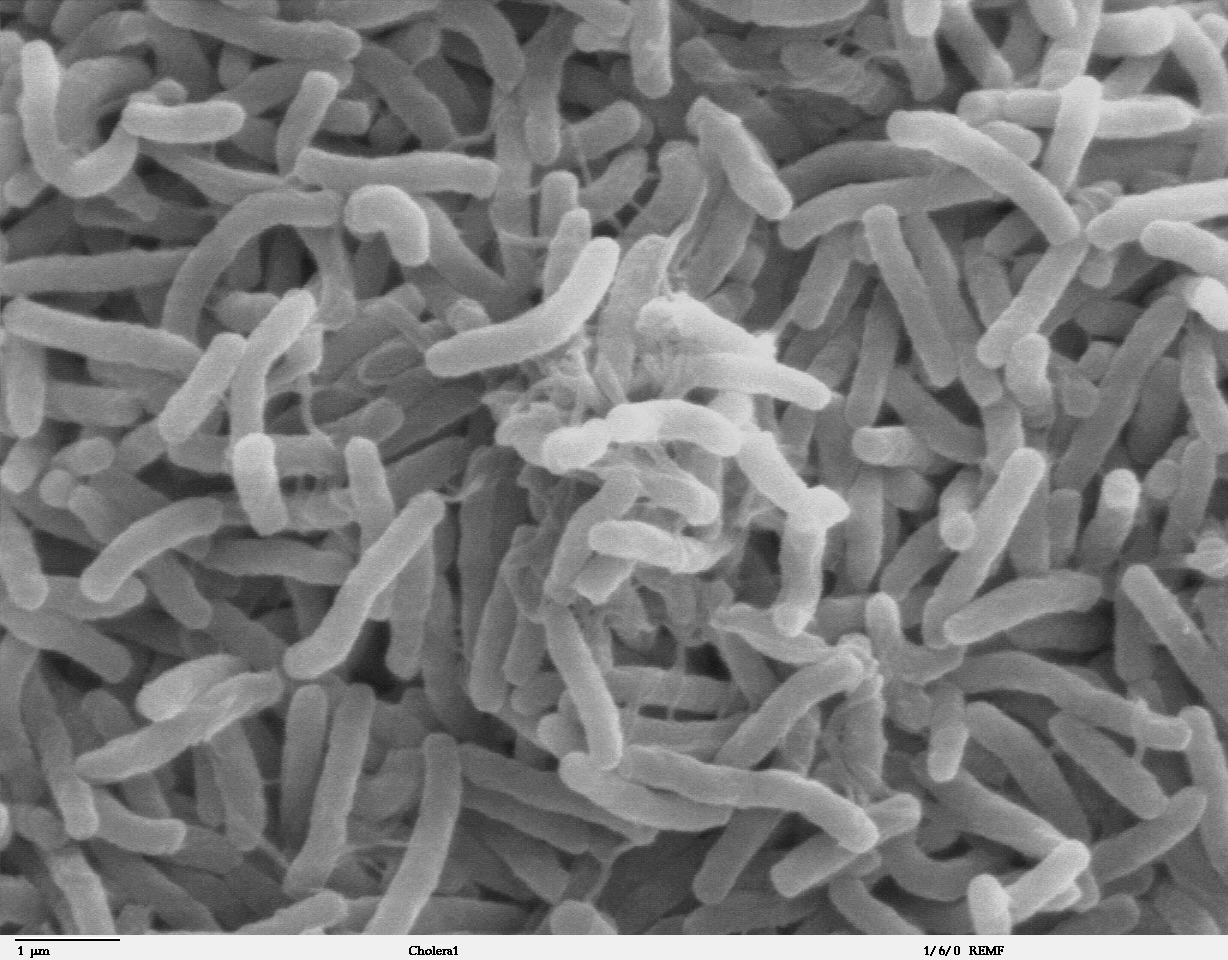

In 1883, responding to a

In 1883, responding to a cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemic in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

, Egypt, both Pasteur and Koch sent missions vying to identify its cause. Koch returned victorious, whereupon Pasteur switched research direction and began development of rabies vaccine. As to public health, Koch's bacteriologists feuded with Max von Pettenkofer

Max Joseph Pettenkofer, ennobled in 1883 as Max Joseph von Pettenkofer (3 December 1818 – 10 February 1901) was a Bavarian chemist and hygienist. He is known for his work in practical hygiene, as an apostle of good water, fresh air and proper ...

—whose miasmatic theory claimed the bacteria was but one causal factor among at least several—but von Pettenkoffer stubbornly opposed water treatment, and the massive cholera epidemic in Hamburg, Germany, in 1892 devastated von Pettenkofer's position, and German public health was grounded on Koch's bacteriology. Meanwhile, Pasteur led introduction of pasteurization in France.

Rabies vaccine and Pasteur Institute

Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease that causes encephalitis in humans and other mammals. It was historically referred to as hydrophobia ("fear of water") because its victims panic when offered liquids to drink. Early symptoms can include fever and abn ...

, uncommon but excruciating and almost invariably fatal, was dreaded. Amid anthrax vaccine's success, Pasteur introduced rabies vaccine

The rabies vaccine is a vaccine used to prevent rabies. There are several rabies vaccines available that are both safe and effective. Vaccinations must be administered prior to rabies virus exposure or within the Latent period (epidemiology), l ...

(1885), the first human vaccine since Jenner's smallpox vaccine

The smallpox vaccine is used to prevent smallpox infection caused by the variola virus. It is the first vaccine to have been developed against a contagious disease. In 1796, British physician Edward Jenner demonstrated that an infection with th ...

(1796). On 6 July 1885, the vaccine was tested on 9-year old Joseph Meister

Joseph Meister (21 February 1876 – 24 June 1940) was the first person to be inoculated against rabies by Louis Pasteur, and likely the first person to be successfully treated for the infection, which has a >99% fatality rate once symptoms ...

who had been bitten by a rabid dog but failed to develop rabies, and Pasteur was called a hero.Trueman C"Louis Pasteur"

''History Learning Site'', 2000–2011, Web. (Even without vaccination, not everyone bitten by a rabid dog develops rabies.) After other apparently successful cases, donations poured in from across the globe, funding the establishment of the

Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (, ) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. Th ...

, the globe's first biomedical institute, which opened in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

in 1888.

Pasteur Institute trained military physicians in colonial medicine, although French government soon took over this role. The success of Pasteur's modification of bacterial virulence inspired confidence in the universality of Pasteurian science, though Pasteur's researchers preferred the term ''microbiology'' over the term ''bacteriology''. Koch discouraged use of rabies vaccine, whose production later became a premise for opening Pasteur Institutes abroad, as in Shanghai

Shanghai, Shanghainese: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: is a direct-administered municipality and the most populous urban area in China. The city is located on the Chinese shoreline on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the ...

, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. The first overseas Pasteur Institute was opened by Albert Calmette

Léon Charles Albert Calmette ForMemRS (; 12 July 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He co-discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, an attenuat ...

in Saigon

Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) ('','' TP.HCM; ), commonly known as Saigon (; ), is the most populous city in Vietnam with a population of around 14 million in 2025.

The city's geography is defined by rivers and canals, of which the largest is Saigo ...

in French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China), officially known as the Indochinese Union and after 1941 as the Indochinese Federation, was a group of French dependent territories in Southeast Asia from 1887 to 1954. It was initial ...

in 1891, although Pasteur's nephew Adrien Loir

Adrien Loir (15 December 1862 – 1941) was a French bacteriologist born in Lyon. He was a nephew of Louis Pasteur, and for much of his career was associated with the Pasteur Institute.

From 1882 to 1888 Loir was an assistant in Pasteur's labo ...

was already planning to open one in Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

.

Tuberculin and Robert Koch Institute

In 1882, Koch reported identification of the ''tubercle bacillus

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis.

First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' ha ...

'' as the cause of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, cementing germ theory. Koch took his research into a new direction—applied research

Applied science is the application of the scientific method and scientific knowledge to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines, such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted with basic science, ...

—to develop a tuberculosis treatment and use the profits to found his own research institute, autonomous from government. In 1890 Koch introduced the intended drug, tuberculin

Tuberculin, also known as purified protein derivative, is a combination of proteins that are used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. This use is referred to as the tuberculin skin test and is recommended only for those at high risk. Reliable adm ...

, but it soon proved ineffective, and accounts of deaths followed in news press. Amid Koch's reluctance to disclose tuberculin's formula, Koch's reputation sustained damage, but Koch retained lasting acclaim and received the 1905 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

"for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis". Koch accepted government's offer to direct the Institute for Infectious Diseases (1891), in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

, a prestigious position but not the kind of institute that Koch had sought. It was later renamed the Robert Koch Institute

The Robert Koch Institute (RKI) is a German federal government agency and research institute responsible for disease control and prevention. It is located in Berlin and Wernigerode. As an upper federal agency, it is subordinate to the Federa ...

, which remains a government organization.

American medicine embraces Koch

The monomorphist doctrine of Koch's bacteriologists suggested public health interventions to eliminate bacteria, whereas Pasteur's acceptance of variation suggested attenuating bacterial virulence in the laboratory to develop vaccines. Although inspired by Pasteur's applications suggesting medicine's potential, American physicians traveled to Germany to learn Koch's bacteriology asbasic science

Basic research, also called pure research, fundamental research, basic science, or pure science, is a type of scientific research with the aim of improving scientific theories for better understanding and prediction of natural or other phenomen ...

, though Pasteur emphasized the fuzzy boundary between basic science and applied science

Applied science is the application of the scientific method and scientific knowledge to attain practical goals. It includes a broad range of disciplines, such as engineering and medicine. Applied science is often contrasted with basic science, ...

.

From 1876 to 1878, the American William Henry Welch

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

trained in Germany pathology, and in 1879 opened America's first scientific laboratory, a pathology laboratory in Bellevue Bellevue means "beautiful view" in French.

Bellevue or Belle Vue may refer to:

Places

Australia

* Bellevue, Queensland

* Bellevue, Western Australia

* Bellevue Hill, New South Wales

Canada

* Bellevue, Alberta

* Bellevue, Newfoundlan ...

's medical school in New York. While in Germany, Welch had met John Shaw Billings

John Shaw Billings (April 12, 1838 – March 11, 1913) was an American librarian, building designer, and surgeon who modernized the Library of the Surgeon General's Office in the United States Army. His work with Andrew Carnegie led to the de ...

who had been appointed by Daniel Coit Gilman

Daniel Coit Gilman (; July 6, 1831 – October 13, 1908) was an American educator and academic. Gilman was instrumental in founding the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale College, and subsequently served as the second president of the University ...

—the first president of the newly forming Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

—to plan Hopkins' hospital and medical school. Named the medical school's first dean in 1883, Welch promptly traveled for training in Koch's bacteriology, and returned to America eager to transform medicine with the "secrets of nature". Hopkins medical school opened in 1894 with Welch emphasizing Koch's bacteriology, which became the foundation of modern medicine.

As "dean of American medicine", William H Welch became the first scientific director of Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classified ...

(1901), and appointed his former Hopkins student Simon Flexner

Simon Flexner (March 25, 1863 – May 2, 1946) was a physician, scientist, administrator, and professor of experimental pathology at the University of Pennsylvania (1899–1903). He served as the first director of the Rockefeller Institute for ...

the first director of pathology and bacteriology laboratories. Aided by the "Flexner report

The ''Flexner Report'' is a book-length landmark report of medical education in the United States and Canada, written by Abraham Flexner and published in 1910 under the aegis of the Carnegie Foundation. Flexner not only described the state of m ...

", published in 1910 while Welch was president of the American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ...

, Welch's view of science and medicine became the national standard, a transformation of American medical education completed around 1930. As first dean of America's first public health school, founded in 1916 at Hopkins, Welch set the standard for public health, and with Simon Flexner exported the Hopkins model internationally.

Pasteur's image ascends

Although Pasteur died in 1895, eventually over thirty official Pasteur Institutes opened across the globe. Pasteur's team had planned in 1885 to open a rabies-treatment facility inSt. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

, and an American Pasteur Institute in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, but the plans were abandoned, and America has never hosted an official Pasteur Institute.Pasteur Foundation"Pasteur Institutes USA: A turn-of-the-century phenomenon"

, ''Remembrance of Things Pasteur'', Accessed 5 Sep 2012 on Web. A number of American copycats appeared, however, starting with "Chicago Pasteur Institute" in 1890, and "New York Pasteur Institute" in 1891. In 1897 a "Pasteur Institute" opened in

Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, in 1900 in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. It is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania#Municipalities, second-most populous city in Pennsylvania (after Philadelphia) and the List of Un ...

and St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

, in 1903 in Ann Arbor

Ann Arbor is a city in Washtenaw County, Michigan, United States, and its county seat. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census recorded its population to be 123,851, making it the List of municipalities in Michigan, fifth-most populous cit ...

and Austin

Austin refers to:

Common meanings

* Austin, Texas, United States, a city

* Austin (given name), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin (surname), a list of people and fictional characters

* Austin Motor Company, a British car manufac ...

, and in 1904 perhaps in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

. In 1908, Georgia Department of Public Health opened a "Pasteur Department" in Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

, California State Hygienic Laboratory opened a "Pasteur Division" in Berkeley

Berkeley most often refers to:

*Berkeley, California, a city in the United States

**University of California, Berkeley, a public university in Berkeley, California

*George Berkeley (1685–1753), Anglo-Irish philosopher

Berkeley may also refer to ...

, and a "Pasteur Institute" opened in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

In 1900, Paul Gibier

Paul Gibier (October 9, 1851–June 23, 1900) was a French medical doctor, bacteriologist, and researcher of contagious diseases who founded the New York Pasteur Institute. This pioneering private research laboratory was concerned with developing b ...

, the French medical scientist who opened "New York Pasteur Institute", accidentally died, but his nephew, George Gibier Rambaud

George may refer to:

Names

* George (given name)

* George (surname)

People

* George (singer), American-Canadian singer George Nozuka, known by the mononym George

* George Papagheorghe, also known as Jorge / GEØRGE

* George, stage name of Giorg ...

, continued it on reduced scale until he closed it when US Medical Corps commissioned him overseas in 1918. While MDs ascended in American public health, it was thought that "the greatest contribution of all, the foundation upon which modern sanitary science is built, was made by Pasteur."

Nationalism flares

Koch was celebrated by the American medical community, including by Welch, when at last Koch visited America in 1908. Soon, however, America was influenced by the British and French view that although their denizens appreciated Germany's progress in science and arts, Germany was elitist and dismissive while socially and politically antiquated, so authoritarian and aggressive as to resemble medieval tyranny. In 1917, when America enteredWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

(1914–18), US government seized German-owned property and assets, including Bayer AG

Bayer AG (English: , commonly pronounced ; ) is a German multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company and is one of the largest pharmaceutical companies and biomedical companies in the world. Headquartered in Leverkusen, Bayer's ...

's American trademarks and the 80% of Merck & Co's shares owned by George Merck. Welch exhibited gratuitous anti-German bias despite the debt of his own career, thus American medicine, to Germany, especially to Koch's bacteriology.

After World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

(1939–45), and more of the "German Problem", Merck & Co became the global leader in vaccinology

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an ag ...

.

Two legacies

Tuberculin

Tuberculin, also known as purified protein derivative, is a combination of proteins that are used in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. This use is referred to as the tuberculin skin test and is recommended only for those at high risk. Reliable adm ...

's main use rapidly became in determining ''M tuberculosis

''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (M. tb), also known as Koch's bacillus, is a species of pathogenic bacteria in the family Mycobacteriaceae and the causative agent of tuberculosis.

First discovered in 1882 by Robert Koch, ''M. tuberculosis'' ha ...

'' infection—a use remaining till today—but this use soon revealed that in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, 9 of 10 individuals were infected, whereas only 1 in 10 of the infected developed the disease. In 1901 at the London Congress on Tuberculosis, Koch stated on theoretical grounds that '' M bovis'', which infects cows, was not transmissible to humans. British attendees disagreed, and later Theobald Smith

Theobald Smith Royal Society of London, FRS(For) HFRSE (July 31, 1859 – December 10, 1934) was a pioneering epidemiology, epidemiologist, bacteriologist, pathology, pathologist and professor. Smith is widely considered to be America's first int ...

and the English Royal Commission empirically established that ''M bovis'' was transmissible and could result in human disease. Though widely considered ineffective as treatment, tuberculin might have remained in use for this purpose until the 1940s and maybe had some effectiveness.

Milk pasteurization

In food processing, pasteurization (American and British English spelling differences#-ise, -ize (-isation, -ization), also pasteurisation) is a process of food preservation in which packaged foods (e.g., milk and fruit juices) are treated wi ...

became popular in America around 1920. In 1921 Albert Calmette

Léon Charles Albert Calmette ForMemRS (; 12 July 1863 – 29 October 1933) was a French physician, bacteriologist and immunologist, and an important officer of the Pasteur Institute. He co-discovered the Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, an attenuat ...

and Camille Guérin

Jean-Marie Camille Guérin (; 22 December 18729 June 1961) was a French veterinarian, bacteriologist and immunologist who, together with Albert Calmette, developed the Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG), a vaccine for immunization against tuber ...

of Pasteur Institute

The Pasteur Institute (, ) is a French non-profit private foundation dedicated to the study of biology, micro-organisms, diseases, and vaccines. It is named after Louis Pasteur, who invented pasteurization and vaccines for anthrax and rabies. Th ...

introduced tuberculosis vaccine

Tuberculosis (TB) vaccines are vaccinations intended for the prevention of tuberculosis. Immunotherapy as a defence against TB was first proposed in 1890 by Robert Koch. As of 2021, the only effective tuberculosis vaccine in common use is the B ...

, whose virulence of strains varied in the late 1920s. BCG vaccine was not used in the public health of America, which virtually eliminated tuberculosis without it. BCG vaccine's effectiveness preventing tuberculosis remains uncertain, but appears to confer nonspecific survival gains, as perhaps by preventing leprosy, and is a cancer treatment.

Pasteur had highlighted a new threat—microorganisms benign to humans passing among and multiplying in nonhuman animals while gaining new virulence for humans—that is thought to loom and to have approximately materialized with AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

. Although Koch's postulates are often inapplicable, they remain heuristic

A heuristic or heuristic technique (''problem solving'', '' mental shortcut'', ''rule of thumb'') is any approach to problem solving that employs a pragmatic method that is not fully optimized, perfected, or rationalized, but is nevertheless ...

, and the authority of "fulfilling Koch's postulates" is still invoked in medical science, though often in modified form, as in the identification of HIV-1

The subtypes of HIV include two main subtypes, known as HIV type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV type 2 (HIV-2). These subtypes have distinct genetic differences and are associated with different epidemiological patterns and clinical characteristics.

HIV-1 e ...

as the cause of AIDS or the identification of SARS coronavirus

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1), previously known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV), is a strain of coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), the respiratory illn ...

as the cause of SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease of zoonotic origin caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1, the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus. The first known cases occurred in November 2002, and the ...

.

Germ theory's stance that the "germ" was the disease's ''necessary and sufficient cause''—the single factor both required and complete to result in the disease—proved false. Germ theory gradually evolved to include other factors, whereupon germ theory resembled miasmatic theory

The miasma theory (also called the miasmic theory) is an abandoned medical theory that held that diseases—such as cholera, chlamydia, or plague—were caused by a ''miasma'' (, Ancient Greek for 'pollution'), a noxious form of "bad air", al ...

, which had had to recognize bacteria as a causal factor, and so the two competing explanations merged without true, decisive victor. Twentieth-century philosophy, inspired by revolutions in physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, establishment of molecular biology

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

, and advances in epidemiology

Epidemiology is the study and analysis of the distribution (who, when, and where), patterns and Risk factor (epidemiology), determinants of health and disease conditions in a defined population, and application of this knowledge to prevent dise ...

, revealed that any claim of a single causal factor both necessary (required) and sufficient (complete), ''the'' cause, is untenable. French-born microbiologist René Dubos

René Jules Dubos (February 20, 1901 – February 20, 1982) was a French-American microbiologist, experimental pathologist, environmentalist, humanist, and winner of the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction for his book '' So Human An Animal ...

, a biographer of Pasteur, discussed tuberculosis to illustrate disease's social causes and to illustrate the failure of germ theory, whose apparent successes were aided by improvements in nutrition and living conditions but sparked scientific research that brought a wealth of new understandings.Meeting summary"Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications for Global Health & Novel Intervention Strategies"

, Institute of Medicine of National Academies, Apr 2010.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Koch-Pasteur Rivalry Scientific rivalry Microbiology 19th century in science France–Germany relations Robert Koch