Kepler Spacecraft on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German

Kepler was born on 27 December 1571, in the Free Imperial City of

Kepler was born on 27 December 1571, in the Free Imperial City of

On 4 February 1600, Kepler met

On 4 February 1600, Kepler met

In October 1604, a bright new evening star (

In October 1604, a bright new evening star (

In Linz, Kepler's primary responsibilities (beyond completing the ''Rudolphine Tables'') were teaching at the district school and providing astrological and astronomical services. In his first years there, he enjoyed financial security and religious freedom relative to his life in Prague—though he was excluded from

In Linz, Kepler's primary responsibilities (beyond completing the ''Rudolphine Tables'') were teaching at the district school and providing astrological and astronomical services. In his first years there, he enjoyed financial security and religious freedom relative to his life in Prague—though he was excluded from  On 8 October 1630, Kepler set out for Regensburg, hoping to collect interest on work he had done previously. A few days after reaching Regensburg, he became sick and progressively worsened. Kepler died on 15 November 1630, just over a month after his arrival. He was buried in a Protestant churchyard in Regensburg, which was completely destroyed during the

On 8 October 1630, Kepler set out for Regensburg, hoping to collect interest on work he had done previously. A few days after reaching Regensburg, he became sick and progressively worsened. Kepler died on 15 November 1630, just over a month after his arrival. He was buried in a Protestant churchyard in Regensburg, which was completely destroyed during the

Kepler's first major astronomical work was '' Mysterium Cosmographicum'' (''The Cosmographic Mystery'', 1596). Kepler claimed to have had an

Kepler's first major astronomical work was '' Mysterium Cosmographicum'' (''The Cosmographic Mystery'', 1596). Kepler claimed to have had an

The extended line of research that culminated in '' Astronomia Nova'' (''A New Astronomy'')—including the first two laws of planetary motion—began with the analysis, under Tycho's direction, of the orbit of Mars. In this work Kepler introduced the revolutionary concept of planetary orbit, a path of a planet in space resulting from the action of physical causes, distinct from previously held notion of planetary orb (a spherical shell to which planet is attached). As a result of this breakthrough astronomical phenomena came to be seen as being governed by physical laws. Kepler calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars's orbit using an

The extended line of research that culminated in '' Astronomia Nova'' (''A New Astronomy'')—including the first two laws of planetary motion—began with the analysis, under Tycho's direction, of the orbit of Mars. In this work Kepler introduced the revolutionary concept of planetary orbit, a path of a planet in space resulting from the action of physical causes, distinct from previously held notion of planetary orb (a spherical shell to which planet is attached). As a result of this breakthrough astronomical phenomena came to be seen as being governed by physical laws. Kepler calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars's orbit using an

In the years following the completion of ''Astronomia Nova'', most of Kepler's research was focused on preparations for the ''Rudolphine Tables'' and a comprehensive set of

In the years following the completion of ''Astronomia Nova'', most of Kepler's research was focused on preparations for the ''Rudolphine Tables'' and a comprehensive set of

Like

Like

Kepler was convinced "that the geometrical things have provided the Creator with the model for decorating the whole world". In ''Harmonice Mundi'' (1619), he attempted to explain the proportions of the natural world—particularly the astronomical and astrological aspects—in terms of music. The central set of "harmonies" was the ''

Kepler was convinced "that the geometrical things have provided the Creator with the model for decorating the whole world". In ''Harmonice Mundi'' (1619), he attempted to explain the proportions of the natural world—particularly the astronomical and astrological aspects—in terms of music. The central set of "harmonies" was the ''

As Kepler slowly continued analyzing Tycho's Mars observations—now available to him in their entirety—and began the slow process of tabulating the ''

As Kepler slowly continued analyzing Tycho's Mars observations—now available to him in their entirety—and began the slow process of tabulating the ''

As a New Year's gift that year (1611), he also composed for his friend and some-time patron, Baron Wackher von Wackhenfels, a short pamphlet entitled ''Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula'' (''A New Year's Gift of Hexagonal Snow''). In this treatise, he published the first description of the hexagonal symmetry of snowflakes and, extending the discussion into a hypothetical atomistic physical basis for their symmetry, posed what later became known as the

As a New Year's gift that year (1611), he also composed for his friend and some-time patron, Baron Wackher von Wackhenfels, a short pamphlet entitled ''Strena Seu de Nive Sexangula'' (''A New Year's Gift of Hexagonal Snow''). In this treatise, he published the first description of the hexagonal symmetry of snowflakes and, extending the discussion into a hypothetical atomistic physical basis for their symmetry, posed what later became known as the

Beyond his role in the historical development of astronomy and natural philosophy, Kepler has loomed large in the

Beyond his role in the historical development of astronomy and natural philosophy, Kepler has loomed large in the

Kepler has acquired a popular image as an icon of scientific modernity and a man before his time; science popularizer

Kepler has acquired a popular image as an icon of scientific modernity and a man before his time; science popularizer

On Firmer Fundaments of Astrology

') (1601) * * '' De Stella nova in pede Serpentarii'' (''On the New Star in Ophiuchus's Foot'') (1606) * '' Astronomia nova'' (''New Astronomy'') (1609) * ''Tertius Interveniens'' (''Third-party Interventions'') (1610) * ''Dissertatio cum Nuncio Sidereo'' (''Conversation with the Starry Messenger'') (1610) *

Dioptrice

' (1611) * ''De nive sexangula'' (

On the Six-Cornered Snowflake

') (1611) * ''De vero Anno, quo aeternus Dei Filius humanam naturam in Utero benedictae Virginis Mariae assumpsit'' (1614)"... in 1614, Johannes Kepler published his book ''De vero anno quo aeternus dei filius humanum naturam in utero benedictae Virginis Mariae assumpsit'', on the chronology related to the Star of Bethlehem."

The Star of Bethlehem

''Ephemerides nouae motuum coelestium''

(1617–30) * * ** ** * * ''

Harmony of the Worlds

') (1619) * '' Mysterium cosmographicum'' (''The Sacred Mystery of the Cosmos''), 2nd edition (1621) * ''

''The Dream''

(1634)

English translation on Google Books preview

* ** ** ** ** ** ** ** ** A critical edition of Kepler's collected works (''Johannes Kepler Gesammelte Werke'', KGW) in 22 volumes is being edited by the ''Kepler-Kommission'' (founded 1935) on behalf of the

bookpage.com

* Gingerich, Owen. ''The Eye of Heaven: Ptolemy, Copernicus, Kepler''. American Institute of Physics, 1993. (Masters of modern physics; v. 7) * Gingerich, Owen: "Kepler, Johannes" in ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography'', Volume VII. Charles Coulston Gillispie, editor. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973 * Jardine, Nick: "Koyré's Kepler/Kepler's Koyré," ''History of Science'', Vol. 38 (2000), pp. 363–376 * Kepler, Johannes. ''Johannes Kepler New Astronomy'' trans. W. Donahue, foreword by O. Gingerich,

vol. 1, 1858vol. 2, 1859vol. 3, 1860vol. 6, 1866vol. 7, 1868

Frankfurt am Main and Erlangen, Heyder & Zimmer, –

Kepler's Conversation with the Starry Messenger (English translation of ''Dissertation cum Nuncio Sidereo'')

* * * (1920 book, part of ''Men of Science'' series) * * Plant, David

* * - Kepler's three laws of planetary motion in the historic context of developing the Heliocentric model {{DEFAULTSORT:Kepler, Johannes 1571 births 1630 deaths People from Weil der Stadt 16th-century German male writers 16th-century German writers 17th-century German male writers 16th-century writers in Latin 16th-century German mathematicians 17th-century writers in Latin 17th-century German mathematicians 17th-century German novelists German expatriates in Austria Scientists from Prague Austrian Lutherans Christian astrologers German cosmologists German astrologers 17th-century German astronomers German Lutherans German music theorists Natural philosophers Copernican Revolution Mathematicians from Prague Members of the Lincean Academy German writers about music Austrian writers about music University of Tübingen alumni 17th-century German philosophers 16th-century German astronomers

astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses on a specific question or field outside the scope of Earth. Astronomers observe astronomical objects, such as stars, planets, natural satellite, moons, comets and galaxy, galax ...

, mathematician

A mathematician is someone who uses an extensive knowledge of mathematics in their work, typically to solve mathematical problems. Mathematicians are concerned with numbers, data, quantity, mathematical structure, structure, space, Mathematica ...

, astrologer

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, natural philosopher

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the developme ...

and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

, best known for his laws of planetary motion, and his books '' Astronomia nova'', ''Harmonice Mundi

''Harmonice Mundi'' (Latin: ''The Harmony of the World'', 1619) is a book by Johannes Kepler. In the work, written entirely in Latin, Kepler discusses harmony and congruence in geometrical forms and physical phenomena. The final section of t ...

'', and ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae

The ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae'' is an astronomy book on the heliocentric system published by Johannes Kepler in the period 1618 to 1621. The first volume (books I–III) was printed in 1618, the second (book IV) in 1620, and the third ...

'', influencing among others Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

, providing one of the foundations for his theory of universal gravitation

Newton's law of universal gravitation describes gravity as a force by stating that every particle attracts every other particle in the universe with a force that is Proportionality (mathematics)#Direct proportionality, proportional to the product ...

. The variety and impact of his work made Kepler one of the founders and fathers of modern astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, the scientific method

The scientific method is an Empirical evidence, empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has been referred to while doing science since at least the 17th century. Historically, it was developed through the centuries from the ancient and ...

, natural

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the laws, elements and phenomena of the physical world, including life. Although humans are part ...

and modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as al ...

. He has been described as the "father of science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

" for his novel '' Somnium''.

Kepler was a mathematics teacher at a seminary

A seminary, school of theology, theological college, or divinity school is an educational institution for educating students (sometimes called seminarians) in scripture and theology, generally to prepare them for ordination to serve as cle ...

school in Graz

Graz () is the capital of the Austrian Federal states of Austria, federal state of Styria and the List of cities and towns in Austria, second-largest city in Austria, after Vienna. On 1 January 2025, Graz had a population of 306,068 (343,461 inc ...

, where he became an associate of Prince Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg. Later he became an assistant to the astronomer Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

, and eventually the imperial mathematician to Emperor Rudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Kingdom of Croatia (Habsburg), Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–16 ...

and his two successors Matthias Matthias is a name derived from the Greek Ματθαίος, in origin similar to Matthew.

Notable people

Notable people named Matthias include the following:

Religion

* Saint Matthias, chosen as an apostle in Acts 1:21–26 to replace Judas Isca ...

and Ferdinand II. He also taught mathematics in Linz

Linz (Pronunciation: , ; ) is the capital of Upper Austria and List of cities and towns in Austria, third-largest city in Austria. Located on the river Danube, the city is in the far north of Austria, south of the border with the Czech Repub ...

, and was an adviser to General Wallenstein.

Additionally, he did fundamental work in the field of optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

, being named the father of modern optics, in particular for his ''Astronomiae pars optica''. He also invented an improved version of the refracting telescope

A refracting telescope (also called a refractor) is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens (optics), lens as its objective (optics), objective to form an image (also referred to a dioptrics, dioptric telescope). The refracting telescope d ...

, the Keplerian telescope, which became the foundation of the modern refracting telescope, while also improving on the telescope design by Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

, who mentioned Kepler's discoveries in his work. He is also known for postulating the Kepler conjecture

The Kepler conjecture, named after the 17th-century mathematician and astronomer Johannes Kepler, is a mathematical theorem about sphere packing in three-dimensional Euclidean space. It states that no arrangement of equally sized spheres filling s ...

.

Kepler lived in an era when there was no clear distinction between astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

and astrology

Astrology is a range of Divination, divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions ...

, but there was a strong division between astronomy (a branch of mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

within the liberal arts

Liberal arts education () is a traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''skill, art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the fine arts. ''Liberal arts education'' can refe ...

) and physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

(a branch of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe, while ignoring any supernatural influence. It was dominant before the develop ...

). Kepler also incorporated religious arguments and reasoning into his work, motivated by the religious conviction and belief that God had created the world according to an intelligible plan that is accessible through the natural light of reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing valid conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, religion, scien ...

. Kepler described his new astronomy as "celestial physics", as "an excursion into Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

's ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

''", and as "a supplement to Aristotle's ''On the Heavens

''On the Heavens'' (Greek: ''Περὶ οὐρανοῦ''; Latin: ''De Caelo'' or ''De Caelo et Mundo'') is Aristotle's chief cosmological treatise: written in 350 BCE, it contains his astronomical theory and his ideas on the concrete workings o ...

'', transforming the ancient tradition of physical cosmology by treating astronomy as part of a universal mathematical physics.

Early life

Childhood (1571–1590)

Kepler was born on 27 December 1571, in the Free Imperial City of

Kepler was born on 27 December 1571, in the Free Imperial City of Weil der Stadt

Weil der Stadt () is a town of about 19,000 inhabitants in the Stuttgart Region of the German state of Baden-Württemberg. It is about west of Stuttgart city centre, in the valley of the River Würm, and is often called the "Gate to the Black Fo ...

(now part of the Stuttgart Region

Stuttgart Region (Baden-Württemberg, Germany) is an urban agglomeration at the heart of the Stuttgart Metropolitan Region. It consists of the city of Stuttgart and the surrounding Districts of Germany, districts of Ludwigsburg (district), Ludwig ...

in the German state of Baden-Württemberg

Baden-Württemberg ( ; ), commonly shortened to BW or BaWü, is a states of Germany, German state () in Southwest Germany, east of the Rhine, which forms the southern part of Germany's western border with France. With more than 11.07 million i ...

). His grandfather, Sebald Kepler, had been Lord Mayor of the city. By the time Johannes was born, the Kepler family fortune was in decline. His father, Heinrich Kepler, earned a precarious living as a mercenary

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rather t ...

, and he left the family when Johannes was five years old. He was believed to have died in the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt (; 1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish Empire, Spanish government. The Origins of the Eighty Years' War, causes of the w ...

in the Netherlands. His mother, Katharina Guldenmann, an innkeeper's daughter, was a healer

Healer may refer to:

Conventional medicine

*Doctor of Medicine

*Health professional

Alternative medicine

* Faith healer

* Folk healer

* Healer (alternative medicine), someone who purports to aid recovery from ill health

* Spiritual healer

F ...

and herbalist

Herbal medicine (also called herbalism, phytomedicine or phytotherapy) is the study of pharmacognosy and the use of medicinal plants, which are a basis of traditional medicine. Scientific evidence for the effectiveness of many herbal treatments ...

. Johannes had six siblings, of which two brothers and one sister survived to adulthood. Born prematurely, he claimed to have been weak and sickly as a child. Nevertheless, he often impressed travelers at his grandfather's inn with his phenomenal mathematical faculty.

He was introduced to astronomy at an early age and developed a strong passion for it that would span his entire life. At age six, he observed the Great Comet of 1577

The Great Comet of 1577 (designated as C/1577 V1 in modern nomenclature) is a non-periodic comet that passed close to Earth with first observation being possible in Peru on 1 November 1577. Final observation was made on 26 January 1578.

Tycho Br ...

, writing that he "was taken by ismother to a high place to look at it." In 1580, at age nine, he observed another astronomical event, a lunar eclipse

A lunar eclipse is an astronomical event that occurs when the Moon moves into the Earth's shadow, causing the Moon to be darkened. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six months, during the full moon phase, ...

, recording that he remembered being "called outdoors" to see it and that the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

"appeared quite red".Koestler. ''The Sleepwalkers'', p. 234 (translated from Kepler's family horoscope). However, childhood smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus '' Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (W ...

left him with weak vision and crippled hands, limiting his ability in the observational aspects of astronomy.

In 1589, after moving through grammar school, Latin school

The Latin school was the grammar school of 14th- to 19th-century Europe, though the latter term was much more common in England. Other terms used include Lateinschule in Germany, or later Gymnasium. Latin schools were also established in Colon ...

, and seminary at Maulbronn, Kepler attended Tübinger Stift

The Tübinger Stift () is a hall of residence and teaching; it is owned and supported by the Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Württemberg, and located in the university city of Tübingen, in South West Germany. The Stift was founded as an Augu ...

at the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (; ), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

The University of Tübingen is one of eleven German Excellenc ...

. There, he studied philosophy under Vitus Müller and theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

under Jacob Heerbrand (a student of Philipp Melanchthon

Philip Melanchthon (born Philipp Schwartzerdt; 16 February 1497 – 19 April 1560) was a German Lutheran reformer, collaborator with Martin Luther, the first systematic theologian of the Protestant Reformation, an intellectual leader of the ...

at Wittenberg

Wittenberg, officially Lutherstadt Wittenberg, is the fourth-largest town in the state of Saxony-Anhalt, in the Germany, Federal Republic of Germany. It is situated on the River Elbe, north of Leipzig and south-west of the reunified German ...

), who also taught Michael Maestlin

Michael Maestlin (; also ''Mästlin'', ''Möstlin'', or ''Moestlin''; 30 September 1550 – 26 October 1631) was a German astronomer and mathematician, best known as the mentor of Johannes Kepler. A student of Philipp Apian, Maestlin is recogniz ...

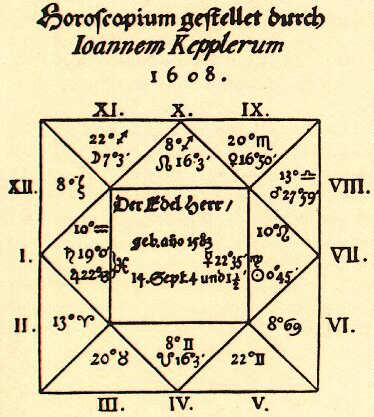

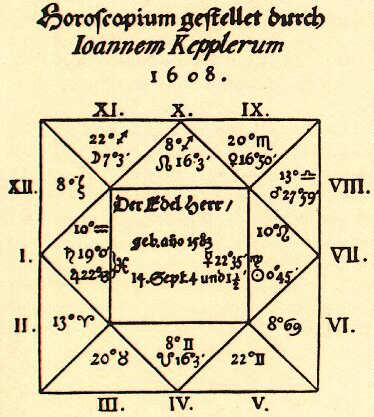

while he was a student, until he became Chancellor at Tübingen in 1590.Barker, Peter; Goldstein, Bernard R. "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy", Osiris, 2nd Series, Vol. 16, Science'' in Theistic Contexts: Cognitive Dimensions'' (2001), p. 96. He proved himself to be a superb mathematician and earned a reputation as a skillful astrologer, casting horoscope

A horoscope (or other commonly used names for the horoscope in English include natal chart, astrological chart, astro-chart, celestial map, sky-map, star-chart, cosmogram, vitasphere, radical chart, radix, chart wheel or simply chart) is an ast ...

s for fellow students. Under the instruction of Michael Maestlin, Tübingen's professor of mathematics from 1583 to 1631, he learned both the Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

and the Copernican system of planetary motion. He became a Copernican at that time. In a student disputation, he defended heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the heliocentric model) is a superseded astronomical model in which the Earth and planets orbit around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed t ...

from both a theoretical and theological perspective, maintaining that the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

was the principal source of motive power in the universe. Despite his desire to become a minister in the Lutheran church, he was denied ordination because of beliefs contrary to the Formula of Concord

Formula of Concord (1577) (; ; also the "''Bergic Book''" or the "''Bergen Book''") is an authoritative Lutheran statement of faith (called a confession, creed, or "symbol") that, in its two parts (''Epitome'' and ''Solid Declaration''), makes up ...

. Near the end of his studies, Kepler was recommended for a position as teacher of mathematics and astronomy at the Protestant school in Graz. He accepted the position in April 1594, at the age of 22.

Graz (1594–1600)

Before concluding his studies at Tübingen, Kepler accepted an offer to teach mathematics as a replacement to Georg Stadius at the Protestant school in Graz (now in Styria, Austria). During this period (1594–1600), he issued many official calendars and prognostications that enhanced his reputation as an astrologer. Although Kepler had mixed feelings about astrology and disparaged many customary practices of astrologers, he believed deeply in a connection between the cosmos and the individual. He eventually published some of the ideas he had entertained while a student in the ''Mysterium Cosmographicum'' (1596), published a little over a year after his arrival at Graz. In December 1595, Kepler was introduced to Barbara Müller, a 23-year-old widow (twice over) with a young daughter, Regina Lorenz, and he began courting her. Müller, an heiress to the estates of her late husbands, was also the daughter of a successful mill owner. Her father Jobst initially opposed a marriage. Even though Kepler had inherited his grandfather's nobility, Kepler's poverty made him an unacceptable match. Jobst relented after Kepler completed work on ''Mysterium'', but the engagement nearly fell apart while Kepler was away tending to the details of publication. However, Protestant officials—who had helped set up the match—pressured the Müllers to honor their agreement. Barbara and Johannes were married on 27 April 1597. In the first years of their marriage, the Keplers had two children (Heinrich and Susanna), both of whom died in infancy. In 1602, they had a daughter (Susanna); in 1604, a son (Friedrich); and in 1607, another son (Ludwig).Other research

Following the publication of ''Mysterium'' and with the blessing of the Graz school inspectors, Kepler began an ambitious program to extend and elaborate his work. He planned four additional books: one on the stationary aspects of the universe (the Sun and the fixed stars); one on the planets and their motions; one on the physical nature of planets and the formation of geographical features (focused especially on Earth); and one on the effects of the heavens on the Earth, to include atmospheric optics, meteorology, and astrology. He also sought the opinions of many of the astronomers to whom he had sent ''Mysterium'', among them Reimarus Ursus (Nicolaus Reimers Bär)—the imperial mathematician toRudolf II

Rudolf II (18 July 1552 – 20 January 1612) was Holy Roman Emperor (1576–1612), King of Hungary and Croatia (as Rudolf I, 1572–1608), King of Bohemia (1575–1608/1611) and Archduke of Austria (1576–1608). He was a member of the H ...

and a bitter rival of Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

. Ursus did not reply directly, but republished Kepler's flattering letter to pursue his priority dispute over (what is now called) the Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the universe published by Tycho Brahe in 1588, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican heliocentrism, Copernican system with the philosophical and "physic ...

with Tycho. Despite this black mark, Tycho also began corresponding with Kepler, starting with a harsh but legitimate critique of Kepler's system; among a host of objections, Tycho took issue with the use of inaccurate numerical data taken from Copernicus. Through their letters, Tycho and Kepler discussed a broad range of astronomical problems, dwelling on lunar phenomena and Copernican theory (particularly its theological viability). But without the significantly more accurate data of Tycho's observatory, Kepler had no way to address many of these issues.

Instead, he turned his attention to chronology

Chronology (from Latin , from Ancient Greek , , ; and , ''wikt:-logia, -logia'') is the science of arranging events in their order of occurrence in time. Consider, for example, the use of a timeline or sequence of events. It is also "the deter ...

and "harmony," the numerological

Numerology (known before the 20th century as arithmancy) is the belief in an occult, divine or mystical relationship between a number and one or more coinciding events. It is also the study of the numerical value, via an alphanumeric system, ...

relationships among music, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

and the physical world, and their astrological

Astrology is a range of divinatory practices, recognized as pseudoscientific since the 18th century, that propose that information about human affairs and terrestrial events may be discerned by studying the apparent positions of celesti ...

consequences. By assuming the Earth to possess a soul (a property he would later invoke to explain how the Sun causes the motion of planets), he established a speculative system connecting astrological aspects

In astrology, an aspect is an angle that planets make to each other in the horoscope; as well as to the Ascendant, Midheaven, Descendant, Lower Midheaven, and other points of astrological interest. As viewed from Earth, aspects are measured ...

and astronomical distances to weather

Weather is the state of the atmosphere, describing for example the degree to which it is hot or cold, wet or dry, calm or stormy, clear or cloud cover, cloudy. On Earth, most weather phenomena occur in the lowest layer of the planet's atmo ...

and other earthly phenomena. By 1599, however, he again felt his work limited by the inaccuracy of available data—just as growing religious tension was also threatening his continued employment in Graz. In December of that year, Tycho invited Kepler to visit him in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

; on 1 January 1600 (before he even received the invitation), Kepler set off in the hopes that Tycho's patronage could solve his philosophical problems as well as his social and financial ones.

Scientific career

Prague (1600–1612)

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe, ; 14 December 154624 October 1601), generally called Tycho for short, was a Danish astronomer of the Renaissance, known for his comprehensive and unprecedentedly accurate astronomical observations. He ...

and his assistants Franz Tengnagel and Longomontanus at Benátky nad Jizerou

Benátky nad Jizerou (; ) is a town in Mladá Boleslav District in the Central Bohemian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 7,900 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected as an urban monument zone.

Administr ...

(35 km from Prague), the site where Tycho's new observatory was being constructed. Over the next two months, he stayed as a guest, analyzing some of Tycho's observations of Mars; Tycho guarded his data closely, but was impressed by Kepler's theoretical ideas and soon allowed him more access. Kepler planned to test his theory from ''Mysterium Cosmographicum'' based on the Mars data, but he estimated that the work would take up to two years (since he was not allowed to simply copy the data for his own use). With the help of Johannes Jessenius

Jan Jesenius, also written as Jessenius (, , ; December 27, 1566 – June 21, 1621), was a Bohemian physician, politician and philosopher.

Life Early years

He was from an old noble family, the House of Jeszenszky, originally from the Kingdom of ...

, Kepler attempted to negotiate a more formal employment arrangement with Tycho, but negotiations broke down in an angry argument and Kepler left for Prague on 6 April. Kepler and Tycho soon reconciled and eventually reached an agreement on salary and living arrangements, and in June, Kepler returned home to Graz to collect his family.

Political and religious difficulties in Graz dashed his hopes of returning immediately to Brahe; in hopes of continuing his astronomical studies, Kepler sought an appointment as a mathematician to Archduke Ferdinand. To that end, Kepler composed an essay—dedicated to Ferdinand—in which he proposed a force-based theory of lunar motion: "In Terra inest virtus, quae Lunam ciet" ("There is a force in the earth which causes the moon to move"). Though the essay did not earn him a place in Ferdinand's court, it did detail a new method for measuring lunar eclipses, which he applied during the 10 July eclipse in Graz. These observations formed the basis of his explorations of the laws of optics that would culminate in ''Astronomiae Pars Optica''.

On 2 August 1600, after refusing to convert to Catholicism, Kepler and his family were banished from Graz. Several months later, Kepler returned, now with the rest of his household, to Prague. Through most of 1601, he was supported directly by Tycho, who assigned him to analyzing planetary observations and writing a tract against Tycho's (by then deceased) rival, Ursus. In September, Tycho secured him a commission as a collaborator on the new project he had proposed to the emperor: the ''Rudolphine Tables

The ''Rudolphine Tables'' () consist of a star catalogue and planetary tables published by Johannes Kepler in 1627, using observational data collected by Tycho Brahe (1546–1601). The tables are named in memory of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emper ...

'' that should replace the ''Prutenic Tables

The ''Prutenic Tables'' ( from ''Prutenia'' meaning "Prussia", ), were an ephemeris (astronomical tables) by the astronomer Erasmus Reinhold published in 1551 (reprinted in 1562, 1571 & 1585). They are sometimes called the ''Prussian Tables'' af ...

'' of Erasmus Reinhold

Erasmus Reinhold (22 October 1511 – 19 February 1553) was a German astronomer and mathematician, considered to be the most influential astronomical pedagogue of his generation. He was born and died in Saalfeld, Saxony.

He was educated, un ...

. Two days after Tycho's unexpected death on 24 October 1601, Kepler was appointed his successor as the imperial mathematician with the responsibility to complete his unfinished work. The next 11 years as imperial mathematician would be the most productive of his life.

Imperial Advisor

Kepler's primary obligation as imperial mathematician was to provide astrological advice to the emperor. Though Kepler took a dim view of the attempts of contemporary astrologers to precisely predict the future or divine specific events, he had been casting well-received detailed horoscopes for friends, family, and patrons since his time as a student in Tübingen. In addition to horoscopes for allies and foreign leaders, the emperor sought Kepler's advice in times of political trouble. Rudolf was actively interested in the work of many of his court scholars (including numerousalchemists

Alchemy (from the Arabic word , ) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first ...

) and kept up with Kepler's work in physical astronomy as well.

Officially, the only acceptable religious doctrines in Prague were Catholic and Utraquist

Utraquism (from the Latin ''sub utraque specie'', meaning "under both kinds"), also called Calixtinism (from chalice; Latin: ''calix'', borrowed from Greek ''kalyx'', "shell, husk"; Czech: ''kališníci''), was a belief amongst Hussites, a pre-P ...

, but Kepler's position in the imperial court allowed him to practice his Lutheran faith unhindered. The emperor nominally provided an ample income for his family, but the difficulties of the over-extended imperial treasury meant that actually getting hold of enough money to meet financial obligations was a continual struggle. Partly because of financial troubles, his life at home with Barbara was unpleasant, marred with bickering and bouts of sickness. Court life, however, brought Kepler into contact with other prominent scholars ( Johannes Matthäus Wackher von Wackhenfels, Jost Bürgi

Jost Bürgi (also ''Joost, Jobst''; Latinized surname ''Burgius'' or ''Byrgius''; 28 February 1552 – 31 January 1632), active primarily at the courts in Kassel and Prague, was a Swiss clockmaker, mathematician, and writer.

Life

Bürgi w ...

, David Fabricius

David Fabricius (9 March 1564 – 7 May 1617) was a Frisian pastor who made two major discoveries in the early days of telescopic astronomy, jointly with his eldest son, Johannes Fabricius (1587–1615).

David Fabricius (Latinization of his prope ...

, Martin Bachazek, and Johannes Brengger, among others) and astronomical work proceeded rapidly.

Supernova of 1604

In October 1604, a bright new evening star (

In October 1604, a bright new evening star (SN 1604

SN 1604, also known as Kepler's Supernova, Kepler's Nova or Kepler's Star, was a Type Ia supernova that occurred in the Milky Way, in the constellation Ophiuchus. Appearing in 1604, it is the most recent supernova in the Milky Way galaxy to have ...

) appeared, but Kepler did not believe the rumors until he saw it himself. Kepler began systematically observing the supernova. Astrologically, the end of 1603 marked the beginning of a fiery trigon, the start of the about 800-year cycle of great conjunction

A great conjunction is a conjunction of the planets Jupiter and Saturn, when the two planets appear closest together in the sky. Great conjunctions occur approximately every 20 years when Jupiter "overtakes" Saturn in its orbit. They are named ...

s; astrologers associated the two previous such periods with the rise of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

(c. 800 years earlier) and the birth of Christ (c. 1600 years earlier), and thus expected events of great portent, especially regarding the emperor.

It was in this context, as the imperial mathematician and astrologer to the emperor, that Kepler described the new star two years later in his ''De Stella Nova

''De Stella Nova in Pede Serpentarii'' (On the New Star in the Foot of the Serpent Handler), generally known as ''De Stella Nova'' was a book written by Johannes Kepler between 1605 and 1606, when the book was published in Prague.

Kepler wrote th ...

''. In it, Kepler addressed the star's astronomical properties while taking a skeptical approach to the many astrological interpretations then circulating. He noted its fading luminosity, speculated about its origin, and used the lack of observed parallax to argue that it was in the sphere of fixed stars, further undermining the doctrine of the immutability of the heavens (the idea accepted since Aristotle that the celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed star ...

were perfect and unchanging). The birth of a new star implied the variability of the heavens. Kepler also attached an appendix where he discussed the recent chronology work of the Polish historian Laurentius Suslyga; he calculated that, if Suslyga was correct that accepted timelines were four years behind, then the Star of Bethlehem

The Star of Bethlehem, or Christmas Star, appears in the nativity of Jesus, nativity story of the Gospel of Matthew Matthew 2, chapter 2 where "wise men from the East" (biblical Magi, Magi) are inspired by the star to travel to Jerusalem. There, ...

—analogous to the present new star—would have coincided with the first great conjunction of the earlier 800-year cycle.

Over the following years, Kepler attempted (unsuccessfully) to begin a collaboration with Italian astronomer Giovanni Antonio Magini

Giovanni Antonio Magini (in Latin, Maginus) (13 June 1555 – 11 February 1617) was an Italian astronomer, astrologer, cartographer, and mathematician.

His Life

He was born in Padua, and completed studies in philosophy in Bologna in 1579. His ...

, and dealt with chronology, especially the dating of events in the life of Jesus. Around 1611, Kepler circulated a manuscript of what would eventually be published (posthumously) as '' Somnium'' he Dream

He or HE may refer to:

Language

* He (letter), the fifth letter of the Semitic abjads

* He (pronoun), a pronoun in Modern English

* He (kana), one of the Japanese kana (へ in hiragana and ヘ in katakana)

* Ge (Cyrillic), a Cyrillic letter c ...

Part of the purpose of ''Somnium'' was to describe what practicing astronomy would be like from the perspective of another planet, to show the feasibility of a non-geocentric system. The manuscript, which disappeared after changing hands several times, described a fantastic trip to the Moon; it was part allegory, part autobiography, and part treatise on interplanetary travel (and is sometimes described as the first work of science fiction). Years later, a distorted version of the story may have instigated the witchcraft trial against his mother, as the mother of the narrator consults a demon to learn the means of space travel. Following her eventual acquittal, Kepler composed 223 footnotes to the story—several times longer than the actual text—which explained the allegorical aspects as well as the considerable scientific content (particularly regarding lunar geography) hidden within the text.

Later life

Troubles

In 1611, the growing political-religious tensions in Prague came to a head. Emperor Rudolf's health was failing, and he was forced to abdicate asKing of Bohemia

The Duchy of Bohemia was established in 870 and raised to the Kingdom of Bohemia in Golden Bull of Sicily, 1198. Several Bohemian monarchs ruled as non-hereditary kings and first gained the title in 1085. From 1004 to 1806, Bohemia was part of th ...

by his brother Matthias Matthias is a name derived from the Greek Ματθαίος, in origin similar to Matthew.

Notable people

Notable people named Matthias include the following:

Religion

* Saint Matthias, chosen as an apostle in Acts 1:21–26 to replace Judas Isca ...

. Both sides sought Kepler's astrological advice, an opportunity he used to deliver conciliatory political advice (with little reference to the stars, except in general statements to discourage drastic action). However, it was clear that Kepler's future prospects in the court of Matthias were bleak.

Also in that year, Kepler's wife Barbara contracted Hungarian spotted fever

''Rickettsia'' is a genus of nonmotile, gram-negative, nonspore-forming, highly pleomorphic bacteria that may occur in the forms of cocci (0.1 μm in diameter), bacilli (1–4 μm long), or threads (up to about 10 μm long). The genus was n ...

and began having seizure

A seizure is a sudden, brief disruption of brain activity caused by abnormal, excessive, or synchronous neuronal firing. Depending on the regions of the brain involved, seizures can lead to changes in movement, sensation, behavior, awareness, o ...

s. While she was recovering, all three of their children fell sick with smallpox; six-year-old Friedrich died. Following his son's death, Kepler sent letters to potential patrons in Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Province of Hohenzollern, Hohenzollern, two other histo ...

and Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

. At the University of Tübingen

The University of Tübingen, officially the Eberhard Karl University of Tübingen (; ), is a public research university located in the city of Tübingen, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

The University of Tübingen is one of eleven German Excellenc ...

in Württemberg, concerns over Kepler's perceived Calvinist

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

heresies in violation of the Augsburg Confession

The Augsburg Confession (), also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, ''Confessio Augustana'', is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheranism, Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of th ...

and the Formula of Concord

Formula of Concord (1577) (; ; also the "''Bergic Book''" or the "''Bergen Book''") is an authoritative Lutheran statement of faith (called a confession, creed, or "symbol") that, in its two parts (''Epitome'' and ''Solid Declaration''), makes up ...

prevented his return. The University of Padua

The University of Padua (, UNIPD) is an Italian public research university in Padua, Italy. It was founded in 1222 by a group of students and teachers from the University of Bologna, who previously settled in Vicenza; thus, it is the second-oldest ...

—on the recommendation of the departing Galileo—sought Kepler to fill the mathematics professorship, but Kepler, preferring to keep his family in German territory, instead travelled to Austria to arrange a position as teacher and district mathematician in Linz

Linz (Pronunciation: , ; ) is the capital of Upper Austria and List of cities and towns in Austria, third-largest city in Austria. Located on the river Danube, the city is in the far north of Austria, south of the border with the Czech Repub ...

. However, Barbara relapsed into illness and died shortly after Kepler's return.

Postponing the move to Linz, Kepler remained in Prague until Rudolf's death in early 1612, though political upheaval, religious tension, and family tragedy (along with the legal dispute over his wife's estate) prevented him from doing any research. Instead, he pieced together a chronology manuscript, ''Eclogae Chronicae'', from correspondence and earlier work. Upon his succession as Holy Roman Emperor, Matthias re-affirmed Kepler's position (and salary) as imperial mathematician but allowed him to move to Linz.

Linz (1612–1630)

In Linz, Kepler's primary responsibilities (beyond completing the ''Rudolphine Tables'') were teaching at the district school and providing astrological and astronomical services. In his first years there, he enjoyed financial security and religious freedom relative to his life in Prague—though he was excluded from

In Linz, Kepler's primary responsibilities (beyond completing the ''Rudolphine Tables'') were teaching at the district school and providing astrological and astronomical services. In his first years there, he enjoyed financial security and religious freedom relative to his life in Prague—though he was excluded from Eucharist

The Eucharist ( ; from , ), also called Holy Communion, the Blessed Sacrament or the Lord's Supper, is a Christianity, Christian Rite (Christianity), rite, considered a sacrament in most churches and an Ordinance (Christianity), ordinance in ...

by his Lutheran church over his theological scruples. It was during his time in Linz that Kepler had to deal with the accusation and ultimate verdict of witchcraft against his mother Katharina in the Protestant town of Leonberg

Leonberg (; ) is a town in the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg about to the west of Stuttgart, the state capital. About 45,000 people live in Leonberg, making it the third-largest borough in the rural district () of Böblingen (afte ...

. That blow, happening only a few years after his excommunication

Excommunication is an institutional act of religious censure used to deprive, suspend, or limit membership in a religious community or to restrict certain rights within it, in particular those of being in Koinonia, communion with other members o ...

, is not seen as a coincidence but as a symptom of the full-fledged assault waged by the Lutherans against Kepler.

His first publication in Linz was ''De vero Anno'' (1613), an expanded treatise on the year of Christ's birth. He also participated in deliberations on whether to introduce Pope Gregory Gregory has been the name of sixteen Roman Catholic Popes and two Antipopes:

*Pope Gregory I ("the Great"; saint; 590–604), after whom the Gregorian chant is named

*Pope Gregory II (saint; 715–731)

*Pope Gregory III (saint; 731–741)

*Pope Gre ...

's reformed calendar to Protestant German lands. On 30 October 1613, Kepler married Susanna Reuttinger. Following the death of his first wife Barbara, Kepler had considered 11 different matches over two years (a decision process formalized later as the marriage problem). He eventually returned to Reuttinger (the fifth match) who, he wrote, "won me over with love, humble loyalty, economy of household, diligence, and the love she gave the stepchildren." The first three children of this marriage (Margareta Regina, Katharina, and Sebald) died in childhood. Three more survived into adulthood: Cordula (born 1621); Fridmar (born 1623); and Hildebert (born 1625). According to Kepler's biographers, this was a much happier marriage than his first.

On 8 October 1630, Kepler set out for Regensburg, hoping to collect interest on work he had done previously. A few days after reaching Regensburg, he became sick and progressively worsened. Kepler died on 15 November 1630, just over a month after his arrival. He was buried in a Protestant churchyard in Regensburg, which was completely destroyed during the

On 8 October 1630, Kepler set out for Regensburg, hoping to collect interest on work he had done previously. A few days after reaching Regensburg, he became sick and progressively worsened. Kepler died on 15 November 1630, just over a month after his arrival. He was buried in a Protestant churchyard in Regensburg, which was completely destroyed during the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

.

Christianity

Kepler's belief that God created the cosmos in an orderly fashion caused him to attempt to determine and comprehend the laws that govern the natural world, most profoundly in astronomy. The phrase "I am merely thinking God's thoughts after Him" has been attributed to him, although this is probably a capsulized version of a writing from his hand:Those lawsKepler advocated for tolerance among Christian denominations, for example arguing that Catholics and Lutherans should be able to take communion together. He wrote, "Christ the Lord neither was nor is Lutheran, nor Calvinist, nor Papist."f nature F, or f, is the sixth letter of the Latin alphabet and many modern alphabets influenced by it, including the modern English alphabet and the alphabets of all other modern western European languages. Its name in English is ''ef'' (pronounc ...are within the grasp of the human mind; God wanted us to recognize them by creating us after his own image so that we could share in his own thoughts.

Astronomy

''Mysterium Cosmographicum''

Kepler's first major astronomical work was '' Mysterium Cosmographicum'' (''The Cosmographic Mystery'', 1596). Kepler claimed to have had an

Kepler's first major astronomical work was '' Mysterium Cosmographicum'' (''The Cosmographic Mystery'', 1596). Kepler claimed to have had an epiphany

Epiphany may refer to:

Psychology

* Epiphany (feeling), an experience of sudden and striking insight

Religion

* Epiphany (holiday), a Christian holiday celebrating the revelation of God the Son as a human being in Jesus Christ

** Epiphany seaso ...

on 19 July 1595, while teaching in Graz

Graz () is the capital of the Austrian Federal states of Austria, federal state of Styria and the List of cities and towns in Austria, second-largest city in Austria, after Vienna. On 1 January 2025, Graz had a population of 306,068 (343,461 inc ...

, demonstrating the periodic conjunction of Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant, with an average radius of about 9 times that of Earth. It has an eighth the average density of Earth, but is over 95 tim ...

and Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

in the zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north and south celestial latitude of the ecliptic – the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. Within this zodiac ...

: he realized that regular polygon

In Euclidean geometry, a regular polygon is a polygon that is Equiangular polygon, direct equiangular (all angles are equal in measure) and Equilateral polygon, equilateral (all sides have the same length). Regular polygons may be either ''convex ...

s bound one inscribed and one circumscribed circle at definite ratios, which, he reasoned, might be the geometrical basis of the universe. After failing to find a unique arrangement of polygons that fit known astronomical observations (even with extra planets added to the system), Kepler began experimenting with 3-dimensional polyhedra

In geometry, a polyhedron (: polyhedra or polyhedrons; ) is a three-dimensional figure with flat polygonal faces, straight edges and sharp corners or vertices. The term "polyhedron" may refer either to a solid figure or to its boundary su ...

. He found that each of the five Platonic solid

In geometry, a Platonic solid is a Convex polytope, convex, regular polyhedron in three-dimensional space, three-dimensional Euclidean space. Being a regular polyhedron means that the face (geometry), faces are congruence (geometry), congruent (id ...

s could be inscribed and circumscribed by spherical orbs; nesting these solids, each encased in a sphere, within one another would produce six layers, corresponding to the six known planets— Mercury, Venus

Venus is the second planet from the Sun. It is often called Earth's "twin" or "sister" planet for having almost the same size and mass, and the closest orbit to Earth's. While both are rocky planets, Venus has an atmosphere much thicker ...

, Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to Planetary habitability, harbor life. This is enabled by Earth being an ocean world, the only one in the Solar System sustaining liquid surface water. Almost all ...

, Mars

Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun. It is also known as the "Red Planet", because of its orange-red appearance. Mars is a desert-like rocky planet with a tenuous carbon dioxide () atmosphere. At the average surface level the atmosph ...

, Jupiter, and Saturn. By ordering the solids selectively—octahedron

In geometry, an octahedron (: octahedra or octahedrons) is any polyhedron with eight faces. One special case is the regular octahedron, a Platonic solid composed of eight equilateral triangles, four of which meet at each vertex. Many types of i ...

, icosahedron

In geometry, an icosahedron ( or ) is a polyhedron with 20 faces. The name comes . The plural can be either "icosahedra" () or "icosahedrons".

There are infinitely many non- similar shapes of icosahedra, some of them being more symmetrical tha ...

, dodecahedron

In geometry, a dodecahedron (; ) or duodecahedron is any polyhedron with twelve flat faces. The most familiar dodecahedron is the regular dodecahedron with regular pentagons as faces, which is a Platonic solid. There are also three Kepler–Po ...

, tetrahedron

In geometry, a tetrahedron (: tetrahedra or tetrahedrons), also known as a triangular pyramid, is a polyhedron composed of four triangular Face (geometry), faces, six straight Edge (geometry), edges, and four vertex (geometry), vertices. The tet ...

, cube

A cube or regular hexahedron is a three-dimensional space, three-dimensional solid object in geometry, which is bounded by six congruent square (geometry), square faces, a type of polyhedron. It has twelve congruent edges and eight vertices. It i ...

—Kepler found that the spheres could be placed at intervals corresponding to the relative sizes of each planet's path, assuming the planets circle the Sun. Kepler also found a formula relating the size of each planet's orb to the length of its orbital period

The orbital period (also revolution period) is the amount of time a given astronomical object takes to complete one orbit around another object. In astronomy, it usually applies to planets or asteroids orbiting the Sun, moons orbiting planets ...

: from inner to outer planets, the ratio of increase in orbital period is twice the difference in orb radius.

Kepler thought the ''Mysterium'' had revealed God's geometrical plan for the universe. Much of Kepler's enthusiasm for the Copernican system stemmed from his theological

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of an ...

convictions about the connection between the physical and the spiritual; the universe itself was an image of God, with the Sun corresponding to the Father, the stellar sphere to the Son

A son is a male offspring; a boy or a man in relation to his parents. The female counterpart is a daughter. From a biological perspective, a son constitutes a first degree relative.

Social issues

In pre-industrial societies and some current ...

, and the intervening space between them to the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit, otherwise known as the Holy Ghost, is a concept within the Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, the Holy Spirit is understood as the divine quality or force of God manifesting in the world, particularly in acts of prophecy, creati ...

. His first manuscript of ''Mysterium'' contained an extensive chapter reconciling heliocentrism with biblical passages that seemed to support geocentrism. With the support of his mentor Michael Maestlin, Kepler received permission from the Tübingen university senate to publish his manuscript, pending removal of the Bible exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

and the addition of a simpler, more understandable, description of the Copernican system as well as Kepler's new ideas. ''Mysterium'' was published late in 1596, and Kepler received his copies and began sending them to prominent astronomers and patrons early in 1597; it was not widely read, but it established Kepler's reputation as a highly skilled astronomer. The effusive dedication, to powerful patrons as well as to the men who controlled his position in Graz, also provided a crucial doorway into the patronage system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a rewar ...

.

In 1621, Kepler published an expanded second edition of ''Mysterium'', half as long again as the first, detailing in footnotes the corrections and improvements he had achieved in the 25 years since its first publication. In terms of impact, the ''Mysterium'' can be seen as an important first step in modernizing the theory proposed by Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

in his ''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book ...

''. While Copernicus sought to advance a heliocentric system in this book, he resorted to Ptolemaic Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

*Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining t ...

devices (viz., epicycles and eccentric circles) in order to explain the change in planets' orbital speed, and also continued to use as a point of reference the center of the Earth's orbit rather than that of the Sun "as an aid to calculation and in order not to confuse the reader by diverging too much from Ptolemy." Modern astronomy owes much to ''Mysterium Cosmographicum'', despite flaws in its main thesis, "since it represents the first step in cleansing the Copernican system of the remnants of the Ptolemaic theory still clinging to it." Kepler never abandoned his five solids theory, publishing the second edition of ''Mysterium'' in 1621 and affirming his continued belief in the validity of the model. Although he noted that there were discrepancies between the observational data and his model's predictions, he did not think they were large enough to invalidate the theory.

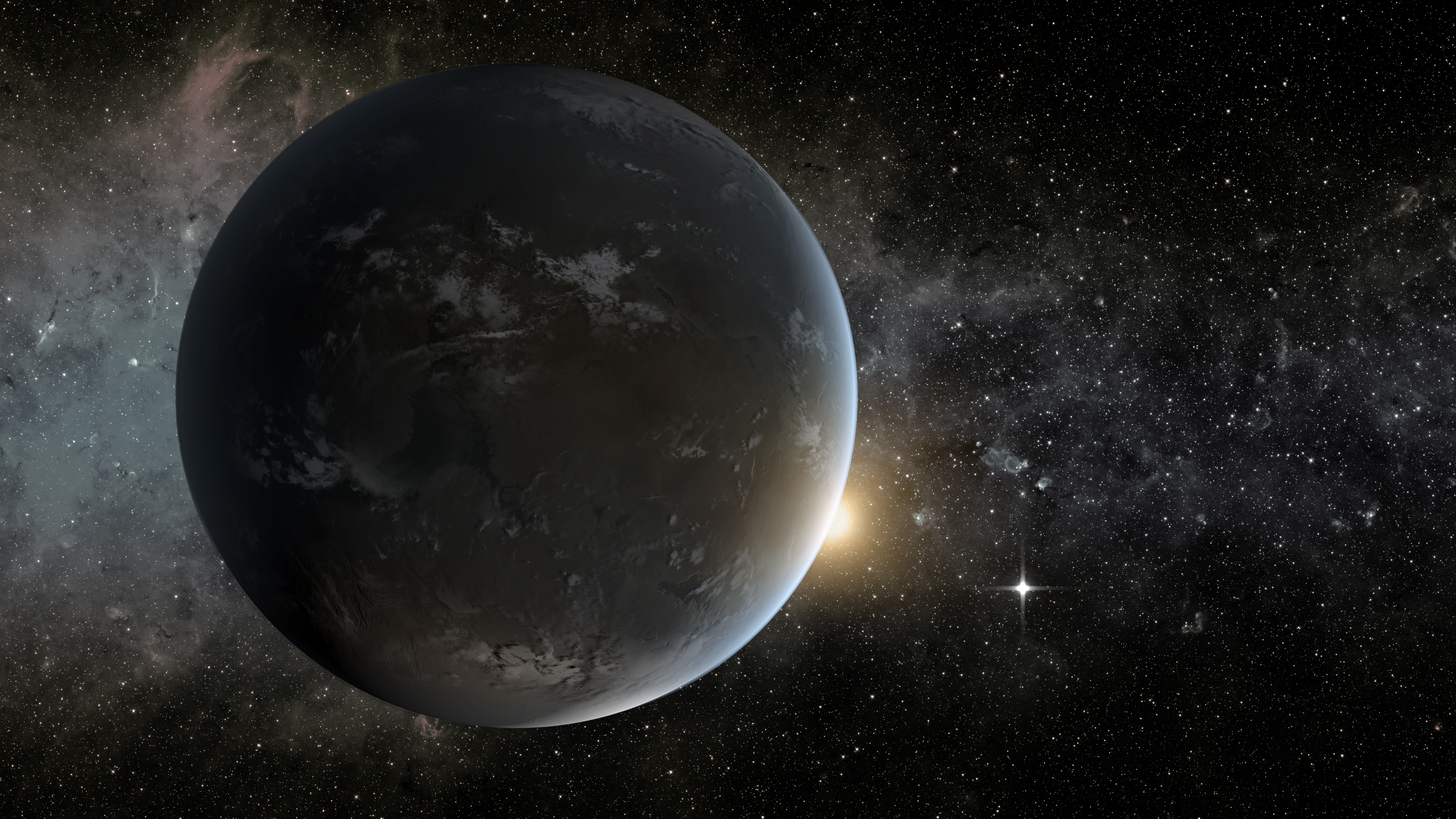

''Astronomia Nova''

The extended line of research that culminated in '' Astronomia Nova'' (''A New Astronomy'')—including the first two laws of planetary motion—began with the analysis, under Tycho's direction, of the orbit of Mars. In this work Kepler introduced the revolutionary concept of planetary orbit, a path of a planet in space resulting from the action of physical causes, distinct from previously held notion of planetary orb (a spherical shell to which planet is attached). As a result of this breakthrough astronomical phenomena came to be seen as being governed by physical laws. Kepler calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars's orbit using an

The extended line of research that culminated in '' Astronomia Nova'' (''A New Astronomy'')—including the first two laws of planetary motion—began with the analysis, under Tycho's direction, of the orbit of Mars. In this work Kepler introduced the revolutionary concept of planetary orbit, a path of a planet in space resulting from the action of physical causes, distinct from previously held notion of planetary orb (a spherical shell to which planet is attached). As a result of this breakthrough astronomical phenomena came to be seen as being governed by physical laws. Kepler calculated and recalculated various approximations of Mars's orbit using an equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plane ...

(the mathematical tool that Copernicus had eliminated with his system), eventually creating a model that generally agreed with Tycho's observations to within two arcminute

A minute of arc, arcminute (abbreviated as arcmin), arc minute, or minute arc, denoted by the symbol , is a unit of angular measurement equal to of a degree. Since one degree is of a turn, or complete rotation, one arcminute is of a tu ...

s (the average measurement error). But he was not satisfied with the complex and still slightly inaccurate result; at certain points the model differed from the data by up to eight arcminutes. The wide array of traditional mathematical astronomy methods having failed him, Kepler set about trying to fit an ovoid

An oval () is a closed curve in a plane which resembles the outline of an egg. The term is not very specific, but in some areas of mathematics (projective geometry, technical drawing, etc.), it is given a more precise definition, which may inc ...

orbit to the data.

In Kepler's religious view of the cosmos, the Sun (a symbol of God the Father

God the Father is a title given to God in Christianity. In mainstream trinitarian Christianity, God the Father is regarded as the first Person of the Trinity, followed by the second person, Jesus Christ the Son, and the third person, God th ...

) was the source of motive force in the Solar System. As a physical basis, Kepler drew by analogy on William Gilbert's theory of the magnetic soul of the Earth from ''De Magnete

''De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure'' (''On the Magnet and Magnetic Bodies, and on That Great Magnet the Earth'') is a scientific work published in 1600 by the English physician and scientist William Gilbert. A hi ...

'' (1600) and on his own work on optics. Kepler supposed that the motive power (or motive ''species'') radiated by the Sun weakens with distance, causing faster or slower motion as planets move closer or farther from it. Using a physical model to derive a trajectory as a major breakthrough. Kepler did not simply assume a circular orbit but attempted to come up with it cause, and did this before discovering the area law Perhaps this assumption entailed a mathematical relationship that would restore astronomical order. Based on measurements of the aphelion

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. The line of apsides (also called apse line, or major axis of the orbit) is the line connecting the two extreme values.

Apsides perta ...

and perihelion

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. The line of apsides (also called apse line, or major axis of the orbit) is the line connecting the two extreme values.

Apsides perta ...

of the Earth and Mars, he created a formula in which a planet's rate of motion is inversely proportional to its distance from the Sun. Verifying this relationship throughout the orbital cycle required very extensive calculation; to simplify this task, by late 1602 Kepler reformulated the proportion in terms of geometry: ''planets sweep out equal areas in equal times''—his second law of planetary motion.

He then set about calculating the entire orbit of Mars, using the geometrical rate law and assuming an egg-shaped ovoid

An oval () is a closed curve in a plane which resembles the outline of an egg. The term is not very specific, but in some areas of mathematics (projective geometry, technical drawing, etc.), it is given a more precise definition, which may inc ...

orbit. After approximately 40 failed attempts, in late 1604 he at last hit upon the idea of an ellipse

In mathematics, an ellipse is a plane curve surrounding two focus (geometry), focal points, such that for all points on the curve, the sum of the two distances to the focal points is a constant. It generalizes a circle, which is the special ty ...

, which he had previously assumed to be too simple a solution for earlier astronomers to have overlooked. Finding that an elliptical orbit fit the Mars data (the Vicarious Hypothesis

The Vicarious Hypothesis, or ''hypothesis vicaria'', was a Planetary habitability, planetary hypothesis proposed by Johannes Kepler to describe the motion of Mars. The hypothesis adopted the circular orbit and equant of Geocentric model, Ptolemy's ...

), Kepler immediately concluded that ''all planets move in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus''—his first law of planetary motion. Because he employed no calculating assistants, he did not extend the mathematical analysis beyond Mars. By the end of the year, he completed the manuscript for ''Astronomia nova'', though it would not be published until 1609 due to legal disputes over the use of Tycho's observations, the property of his heirs.

''Epitome of Copernican Astronomy''

Since completing the ''Astronomia Nova'', Kepler had intended to compose an astronomy textbook that would cover all the fundamentals of heliocentric astronomy. Kepler spent the next several years working on what would become ''Epitome Astronomiae Copernicanae'' (''Epitome of Copernican Astronomy''). Despite its title, which merely hints at heliocentrism, the ''Epitome'' is less about Copernicus's work and more about Kepler's own astronomical system. The ''Epitome'' contained all three laws of planetary motion and attempted to explain heavenly motions through physical causes.Gingerich, "Kepler, Johannes" from ''Dictionary of Scientific Biography'', pp. 302–304 Although it explicitly extended the first two laws of planetary motion (applied to Mars in ''Astronomia nova'') to all the planets as well as the Moon and the Medicean satellites of Jupiter, it did not explain how elliptical orbits could be derived from observational data. Originally intended as an introduction for the uninitiated, Kepler sought to model his ''Epitome'' after that of his masterMichael Maestlin

Michael Maestlin (; also ''Mästlin'', ''Möstlin'', or ''Moestlin''; 30 September 1550 – 26 October 1631) was a German astronomer and mathematician, best known as the mentor of Johannes Kepler. A student of Philipp Apian, Maestlin is recogniz ...

, who published a well-regarded book explaining the basics of geocentric astronomy to non-experts. Kepler completed the first of three volumes, consisting of Books I–III, by 1615 in the same question-answer format of Maestlin's and have it printed in 1617. However, the banning of Copernican books by the Catholic Church, as well as the start of the Thirty Years' War

The Thirty Years' War, fought primarily in Central Europe between 1618 and 1648, was one of the most destructive conflicts in History of Europe, European history. An estimated 4.5 to 8 million soldiers and civilians died from battle, famine ...

, meant that publication of the next two volumes would be delayed. In the interim, and to avoid being subject to the ban, Kepler switched the audience of the ''Epitome'' from beginners to that of expert astronomers and mathematicians, as the arguments became more and more sophisticated and required advanced mathematics to be understood. The second volume, consisting of Book IV, was published in 1620, followed by the third volume, consisting of Books V–VII, in 1621.

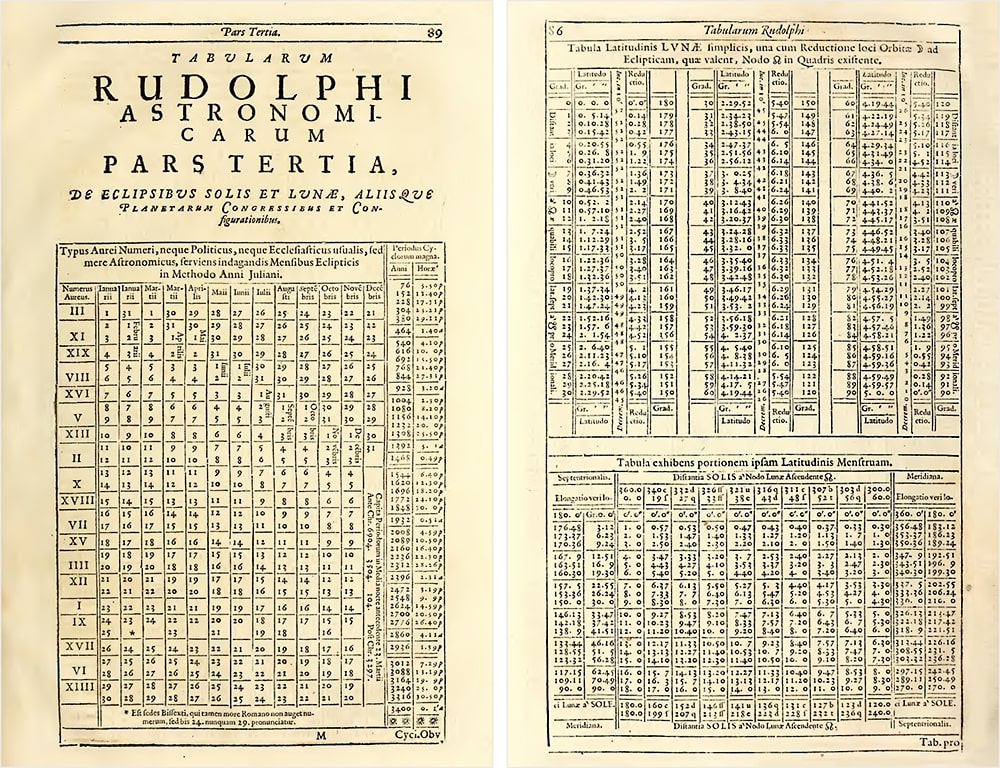

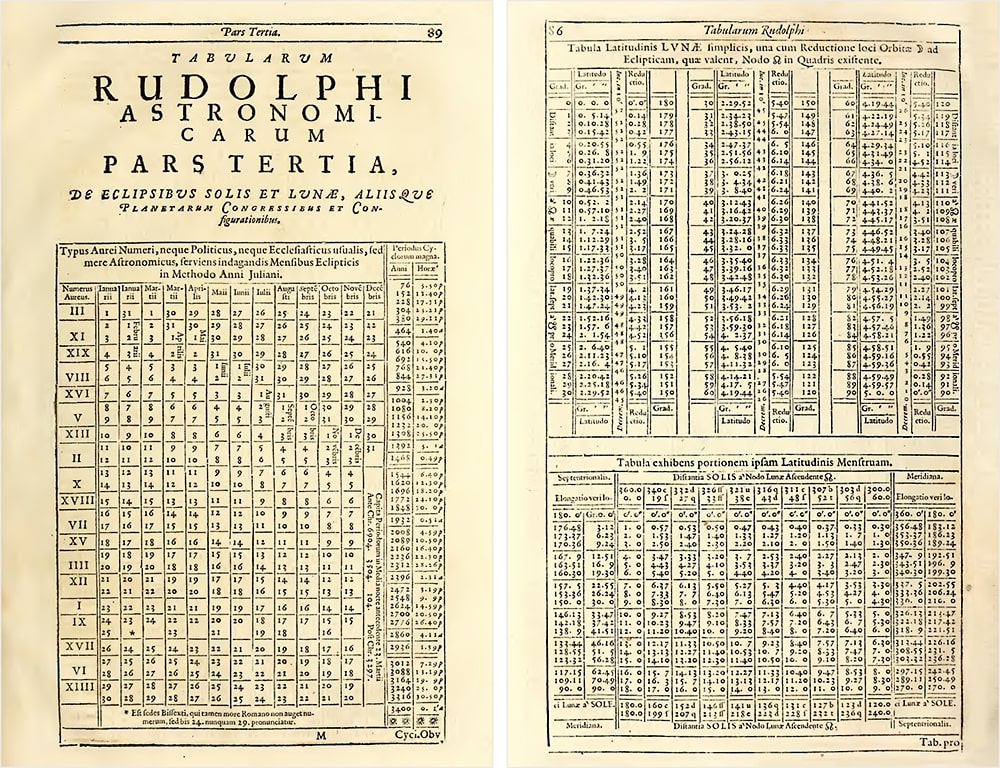

''Rudolphine Tables''

In the years following the completion of ''Astronomia Nova'', most of Kepler's research was focused on preparations for the ''Rudolphine Tables'' and a comprehensive set of

In the years following the completion of ''Astronomia Nova'', most of Kepler's research was focused on preparations for the ''Rudolphine Tables'' and a comprehensive set of ephemerides

In astronomy and celestial navigation, an ephemeris (; ; , ) is a book with tables that gives the trajectory of naturally occurring astronomical objects and artificial satellites in the sky, i.e., the position (and possibly velocity) over time. ...

(specific predictions of planet and star positions) based on the table, though neither would be completed for many years.

Kepler, at last, completed the ''Rudolphine Tables

The ''Rudolphine Tables'' () consist of a star catalogue and planetary tables published by Johannes Kepler in 1627, using observational data collected by Tycho Brahe (1546–1601). The tables are named in memory of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emper ...

'' in 1623, which at the time was considered his major work. However, due to the publishing requirements of the emperor and negotiations with Tycho Brahe's heir, it would not be printed until 1627.

Astrology

Like

Like Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; – 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, Kepler considered astrology as the counterpart to astronomy, and as being of equal interest and value. However, in the following years, the two subjects drifted apart until astrology was no longer practiced among professional astronomers.

Sir Oliver Lodge