Johnston Atoll on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johnston Atoll is an

Johnston Atoll is a atoll in the

Johnston Atoll is a atoll in the  The four islands compose a total land area of . Due to the atoll's tilt, much of the reef on the southeast portion has subsided. But even though it does not have an encircling reef crest, the reef crest on the northwest portion of the atoll does provide for a shallow

The four islands compose a total land area of . Due to the atoll's tilt, much of the reef on the southeast portion has subsided. But even though it does not have an encircling reef crest, the reef crest on the northwest portion of the atoll does provide for a shallow

Seabird species recorded as breeding on the atoll include Bulwer's petrel,

Seabird species recorded as breeding on the atoll include Bulwer's petrel,

File:Starr 080606-6956 Lepturus repens.jpg, '' Lepturus repens''

File:Punar-nava (Telugu- పునర్నవ) (4938290660).jpg, '' Boerhavia diffusa''

File:Starr 080605-6704 Tribulus cistoides.jpg, '' Tribulus cistoides''

The first Western record of the atoll was on September 2, 1796, when the Boston-based American

The first Western record of the atoll was on September 2, 1796, when the Boston-based American

In 1935, personnel from the US Navy's Patrol Wing Two carried out some minor construction to develop the atoll for seaplane operation. In 1936, the Navy began the first of many changes to enlarge the atoll's land area. They erected some buildings and a boat landing on Sand Island and blasted coral to clear a seaplane landing. Several seaplanes made flights from Hawaii to Johnston, such as that of a squadron of six aircraft in November 1935.

In November 1939, civilian contractors commenced further work on Sand Island to allow the operation of one squadron of patrol planes with tender support. Part of the lagoon was dredged, and the excavated material was used to make a parking area connected by a causeway to Sand Island. Three seaplane landings were cleared, one by and two cross-landings each by and dredged to a depth of . Sand Island had barracks built for 400 men, a mess hall, an underground hospital, a radio station, water tanks, and a steel control tower. In December 1943 an additional of parking was added to the seaplane base.

On May 26, 1942, a

In 1935, personnel from the US Navy's Patrol Wing Two carried out some minor construction to develop the atoll for seaplane operation. In 1936, the Navy began the first of many changes to enlarge the atoll's land area. They erected some buildings and a boat landing on Sand Island and blasted coral to clear a seaplane landing. Several seaplanes made flights from Hawaii to Johnston, such as that of a squadron of six aircraft in November 1935.

In November 1939, civilian contractors commenced further work on Sand Island to allow the operation of one squadron of patrol planes with tender support. Part of the lagoon was dredged, and the excavated material was used to make a parking area connected by a causeway to Sand Island. Three seaplane landings were cleared, one by and two cross-landings each by and dredged to a depth of . Sand Island had barracks built for 400 men, a mess hall, an underground hospital, a radio station, water tanks, and a steel control tower. In December 1943 an additional of parking was added to the seaplane base.

On May 26, 1942, a

By September 1941, construction of an

By September 1941, construction of an

On January 25, 1957, the Department of Treasury was granted a 5-year permit for the

On January 25, 1957, the Department of Treasury was granted a 5-year permit for the

The "Fishbowl" series included four failures, all deliberately disrupted by range safety officers when the missiles' systems failed during launch and were aborted. The second launch of the Fishbowl series, "

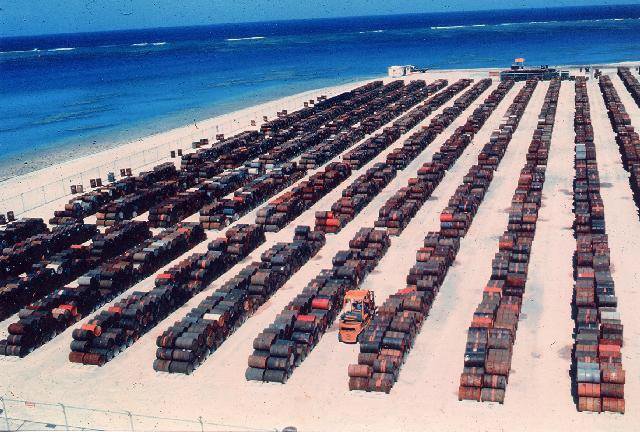

The "Fishbowl" series included four failures, all deliberately disrupted by range safety officers when the missiles' systems failed during launch and were aborted. The second launch of the Fishbowl series, " Afterward, the Johnston Island launch complex was heavily damaged and contaminated with plutonium. Missile launches and nuclear testing halted until the radioactive debris was dumped, soils were recovered, and the launch emplacement rebuilt. Before tests could resume, three months of repairs, decontamination, and rebuilding of the LE1 and the backup pad LE2 were necessary. To continue with the testing program, U.S. troops were sent in to do a rapid cleanup. The troops scrubbed down the revetments and launch pad, carted away debris, and removed the top layer of coral around the contaminated launch pad. The plutonium-contaminated rubbish was dumped in the lagoon, polluting the surrounding marine environment. Over 550 drums of contaminated material were dumped in the ocean off Johnston from 1964 to 1965. At the time of the Bluegill Prime disaster, a bulldozer and grader scraped the top fill around the launch pad. It was then dumped into the lagoon to make a ramp so the rest of the debris could be loaded onto the landing craft to be dumped into the ocean. An estimated 10 percent of the plutonium from the test device was in the fill used to make the ramp. Then, the ramp was covered and placed into a landfill on the island during 1962 dredging to extend the island. The lagoon was again dredged in 1963–1964 and used to expand Johnston Island from , recontaminating additional portions of the island.

Afterward, the Johnston Island launch complex was heavily damaged and contaminated with plutonium. Missile launches and nuclear testing halted until the radioactive debris was dumped, soils were recovered, and the launch emplacement rebuilt. Before tests could resume, three months of repairs, decontamination, and rebuilding of the LE1 and the backup pad LE2 were necessary. To continue with the testing program, U.S. troops were sent in to do a rapid cleanup. The troops scrubbed down the revetments and launch pad, carted away debris, and removed the top layer of coral around the contaminated launch pad. The plutonium-contaminated rubbish was dumped in the lagoon, polluting the surrounding marine environment. Over 550 drums of contaminated material were dumped in the ocean off Johnston from 1964 to 1965. At the time of the Bluegill Prime disaster, a bulldozer and grader scraped the top fill around the launch pad. It was then dumped into the lagoon to make a ramp so the rest of the debris could be loaded onto the landing craft to be dumped into the ocean. An estimated 10 percent of the plutonium from the test device was in the fill used to make the ramp. Then, the ramp was covered and placed into a landfill on the island during 1962 dredging to extend the island. The lagoon was again dredged in 1963–1964 and used to expand Johnston Island from , recontaminating additional portions of the island.

On October 15, 1962, the " Bluegill Double Prime" test also misfired. During the test, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned 90 seconds into the flight. U.S. Defense Department officials confirm that the rocket's destruction contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

In 1963, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which contained a provision known as "Safeguard C". Safeguard C was the basis for maintaining Johnston Atoll as a "ready to test" above-ground nuclear testing site should atmospheric nuclear testing ever be deemed necessary again. In 1993, Congress appropriated no funds for the Johnston Atoll "Safeguard C" mission, ending it.

On October 15, 1962, the " Bluegill Double Prime" test also misfired. During the test, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned 90 seconds into the flight. U.S. Defense Department officials confirm that the rocket's destruction contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

In 1963, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which contained a provision known as "Safeguard C". Safeguard C was the basis for maintaining Johnston Atoll as a "ready to test" above-ground nuclear testing site should atmospheric nuclear testing ever be deemed necessary again. In 1993, Congress appropriated no funds for the Johnston Atoll "Safeguard C" mission, ending it.

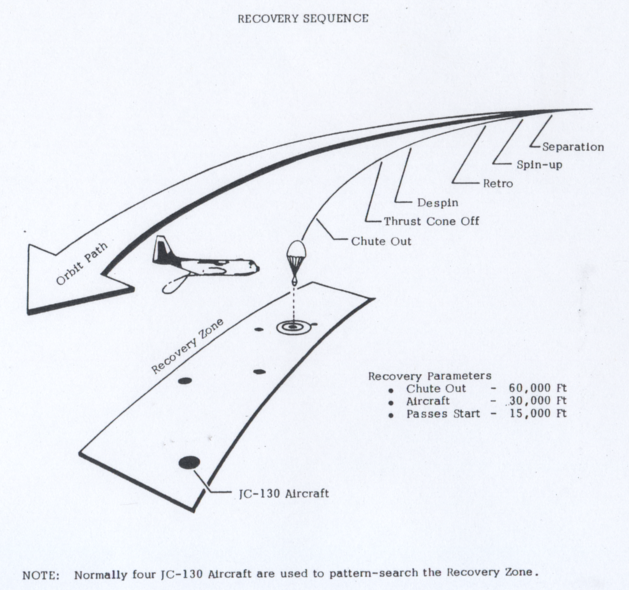

Satellite and Missile Observation System Project (SAMOS-E) or "E-6" was a relatively short-lived series of

Satellite and Missile Observation System Project (SAMOS-E) or "E-6" was a relatively short-lived series of  During the early months of the SAMOS program, it was essential not only to hide the Corona and GAMBIT technical efforts under a screen of SAMOS activity but also to make the orbital vehicle portions of the two systems resemble one another in outward appearance. Thus, some of the configuration details of SAMOS were decided less by engineering logic than by the need to camouflage GAMBIT. Hence, theoretically, a GAMBIT could be launched without alerting many people to its real nature.

Problems relative to tracking networks, communications, and recovery were resolved with the decision in late February 1961 to use Johnston Island as the program's film capsule descent and recovery zone.

On July 10, 1961, work was initiated on four buildings of the Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center for the

During the early months of the SAMOS program, it was essential not only to hide the Corona and GAMBIT technical efforts under a screen of SAMOS activity but also to make the orbital vehicle portions of the two systems resemble one another in outward appearance. Thus, some of the configuration details of SAMOS were decided less by engineering logic than by the need to camouflage GAMBIT. Hence, theoretically, a GAMBIT could be launched without alerting many people to its real nature.

Problems relative to tracking networks, communications, and recovery were resolved with the decision in late February 1961 to use Johnston Island as the program's film capsule descent and recovery zone.

On July 10, 1961, work was initiated on four buildings of the Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center for the

The Army's Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) was the first full-scale chemical weapons disposal facility. Built to incinerate chemical munitions on the island, planning started in 1981, construction began in 1985, and it was completed five years later. Following construction and facility characterization, JACADS began operational verification testing (OVT) in June 1990. From 1990 until 1993, the Army conducted four planned periods of Operational Verification Testing (OVT), required by Public Law 100–456. OVT was completed in March 1993, demonstrating that the reverse assembly incineration technology was adequate and that JACADS operations met all environmental parameters. The transition to full-scale operations started in May 1993, but the facility did not begin full-scale operations until August 1993.

All of the chemical weapons once stored on Johnston Island were demilitarized, and the agents incinerated at JACADS, with the process completed in the year 2000. Later, the destruction of legacy hazardous waste material associated with chemical weapon storage and cleanup was completed. JACADS was demolished by 2003, and the island was stripped of its remaining infrastructure and environmentally remediated.

The Army's Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) was the first full-scale chemical weapons disposal facility. Built to incinerate chemical munitions on the island, planning started in 1981, construction began in 1985, and it was completed five years later. Following construction and facility characterization, JACADS began operational verification testing (OVT) in June 1990. From 1990 until 1993, the Army conducted four planned periods of Operational Verification Testing (OVT), required by Public Law 100–456. OVT was completed in March 1993, demonstrating that the reverse assembly incineration technology was adequate and that JACADS operations met all environmental parameters. The transition to full-scale operations started in May 1993, but the facility did not begin full-scale operations until August 1993.

All of the chemical weapons once stored on Johnston Island were demilitarized, and the agents incinerated at JACADS, with the process completed in the year 2000. Later, the destruction of legacy hazardous waste material associated with chemical weapon storage and cleanup was completed. JACADS was demolished by 2003, and the island was stripped of its remaining infrastructure and environmentally remediated.

In 2003, structures and facilities, including those used in JACADS, were removed, and the runway was marked closed. The last flight out for official personnel was June 15, 2004. After this date, the base was completely deserted, with the only structures left standing being the Joint Operations Center (JOC) building at the east end of the runway, chemical bunkers in the weapon storage area, and at least one

In 2003, structures and facilities, including those used in JACADS, were removed, and the runway was marked closed. The last flight out for official personnel was June 15, 2004. After this date, the base was completely deserted, with the only structures left standing being the Joint Operations Center (JOC) building at the east end of the runway, chemical bunkers in the weapon storage area, and at least one

The atoll was placed up for auction via the U.S.

The atoll was placed up for auction via the U.S.

Plateshack.com: Johnston Atoll

(Accessed July 25, 2009)

Video from 1923 USS ''Tanager'' Expedition

Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Multi-Agency Education Project of the University of Hawaii

"Cleaning up Johnston Atoll"

(2005), Plutonium contamination on the Island.

Johnston Island Memories Site

– the personal website of an AFRTS serviceman stationed there in 1975 to 1976

Coast Guard Medevac from Johnston Island

– photo from December 2007 medevac operation

– Pictorial evidence of chemical weapons disposal

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Johnston Island National Wildlife Refuge

– Contains additional information on wildlife and clean-up efforts

– website about the end of Johnston Atoll

Flickr: Laysan at Johnston Island

– Photographs of stop-over on abandoned Johnston Atoll in 2012

The Sovereignty of Guano Islands in the Pacific Ocean

, U.S. Department of State Legal Advisor, January 9, 1933. {{authority control Pacific Ocean atolls of the United States United States Minor Outlying Islands American nuclear test sites Bird sanctuaries of the United States Former populated places in Oceania Geography of Micronesia Islands of Oceania Pacific islands claimed under the Guano Islands Act National Wildlife Refuges in the United States insular areas Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument Protected areas established in 2009 Uninhabited Pacific islands of the United States Important Bird Areas of United States Minor Outlying Islands Important Bird Areas of Oceania Seabird colonies

unincorporated territory

Territories of the United States are sub-national administrative divisions and dependent territory, dependent territories overseen by the federal government of the United States. The American territories differ from the U.S. states and Indi ...

of the United States, under the jurisdiction of the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

(USAF). The island is closed to public entry, and limited access for management needs is only granted by a letter of authorization from the USAF. A special use permit is also required from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS or FWS) is a List of federal agencies in the United States, U.S. federal government agency within the United States Department of the Interior which oversees the management of fish, wildlife, ...

(USFWS) to access the island by boat or enter the waters surrounding the island, which are designated as a National Wildlife Refuge

The National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS) is a system of protected areas of the United States managed by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), an agency within the United States Department of the Interior, Department of the Interi ...

and part of the Pacific Islands Heritage Marine National Monument. The Johnston Atoll National Wildlife Refuge extends from the shore out to 12 nautical miles, continuing as part of the National Wildlife Refuge System out to 200 nautical miles. The Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument extends from the shore out to 200 nautical miles.

The isolated atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical parts of the oceans and seas where corals can develop. Most ...

has been under the control of the U.S. military since 1934. During that time, it was variously used as a naval refueling depot, an airbase

An airbase (stylised air base in American English), sometimes referred to as a military airbase, military airfield, military airport, air station, naval air station, air force station, or air force base, is an aerodrome or airport used as a mi ...

, a testing site for nuclear

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

*Nuclear ...

and biological weapons

Biological agents, also known as biological weapons or bioweapons, are pathogens used as weapons. In addition to these living or replicating pathogens, toxins and biotoxins are also included among the bio-agents. More than 1,200 different kin ...

, a secret missile base, and a site for the storage and disposal of chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as ...

s and Agent Orange

Agent Orange is a chemical herbicide and defoliant, one of the tactical uses of Rainbow Herbicides. It was used by the U.S. military as part of its herbicidal warfare program, Operation Ranch Hand, during the Vietnam War from 1962 to 1971. T ...

. Those activities left the area environmentally contaminated. The USAF completed remediating the contamination in 2004 and performs only periodic monitoring today.

The island is home to thriving communities of nesting seabirds and has significant marine biodiversity. USAF and USFWS teams conduct environmental monitoring

Environmental monitoring is the processes and activities that are done to characterize and describe the state of the environment. It is used in the preparation of environmental impact assessments, and in many circumstances in which human activit ...

and maintenance to protect the native wildlife. In the 21st century, one ecological problem was yellow crazy ants that were killing seabirds, but by the 2020s these were eradicated.

The atoll originally consisted of two islands, Johnston and Sand island surrounded partially by a coral reef. Over the 20th century, those two islands were expanded, and two new islands, North (Akau) and East (Hikina) were created mostly by coral dredging. A long airstrip was built on Johnston, and there are also various channels through the coral reef.

Geography

Johnston Atoll is a atoll in the

Johnston Atoll is a atoll in the North Pacific Ocean

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''north'' ...

, located about southwest of the island of Hawaiʻi, and is grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands

The United States Minor Outlying Islands is a statistical designation applying to the minor outlying islands and groups of islands that comprise eight United States insular areas in the Pacific Ocean (Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Isla ...

. The atoll, which is located on a coral reef

A coral reef is an underwater ecosystem characterized by reef-building corals. Reefs are formed of colonies of coral polyps held together by calcium carbonate. Most coral reefs are built from stony corals, whose polyps cluster in group ...

platform, has four islands. Johnston Island and Sand Island are both enlarged natural features, while ''Akau'' (North) and ''Hikina'' (East) are two artificial island

An artificial island or man-made island is an island that has been Construction, constructed by humans rather than formed through natural processes. Other definitions may suggest that artificial islands are lands with the characteristics of hum ...

s formed by coral dredging

Dredging is the excavation of material from a water environment. Possible reasons for dredging include improving existing water features; reshaping land and water features to alter drainage, navigability, and commercial use; constructing d ...

. By 1964, dredge and fill operations had increased the size of Johnston Island to from its original , increased the size of Sand Island from , and added the two new islands, North and East, of respectively.

lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') an ...

, with depths ranging from .

The climate is tropical but generally dry. Northeast trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisphere ...

are consistent. There is little seasonal temperature variation. With elevation ranging from sea level to at Summit Peak, the islands contain some low-growing vegetation and palm trees on mostly flat terrain, and no natural freshwater resources.

Climate

Johnston Atoll has ahot semi-arid climate

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of sem ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

: ''BSh''; Trewartha: ''BSha''). It is a dry atoll with just over of annual rainfall.

Wildlife

About 300 species offish

A fish (: fish or fishes) is an aquatic animal, aquatic, Anamniotes, anamniotic, gill-bearing vertebrate animal with swimming fish fin, fins and craniate, a hard skull, but lacking limb (anatomy), limbs with digit (anatomy), digits. Fish can ...

have been recorded from the reefs and inshore waters of the atoll. It is also visited by green turtle

The green sea turtle (''Chelonia mydas''), also known as the green turtle, black (sea) turtle or Pacific green turtle, is a species of large sea turtle of the family Cheloniidae. It is the only species in the genus ''Chelonia''. Its range exte ...

s and Hawaiian monk seals. The possibility of humpback whale

The humpback whale (''Megaptera novaeangliae'') is a species of baleen whale. It is a rorqual (a member of the family Balaenopteridae) and is the monotypic taxon, only species in the genus ''Megaptera''. Adults range in length from and weigh u ...

s using the waters as a breeding ground has been suggested, albeit in small numbers and with irregular occurrences. Many other cetacean

Cetacea (; , ) is an infraorder of aquatic mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla that includes whales, dolphins and porpoises. Key characteristics are their fully aquatic lifestyle, streamlined body shape, often large size and exclusively c ...

s possibly migrate through the area, including Cuvier's beaked whale

Cuvier's beaked whale, goose-beaked whale, or ziphius (''Ziphius cavirostris'') is the most widely distributed of all beaked whales in the family Beaked whale, Ziphiidae. It is smaller than most baleen whales—and indeed the larger Toothed whal ...

s.

Birds

Seabird species recorded as breeding on the atoll include Bulwer's petrel,

Seabird species recorded as breeding on the atoll include Bulwer's petrel, wedge-tailed shearwater

The wedge-tailed shearwater (''Ardenna pacifica'') is a medium-large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. It is one of the shearwater species that is sometimes referred to as a muttonbird, like the sooty shearwater of New Zealand and ...

, Christmas shearwater

The Christmas shearwater or ''aoū'' (''Puffinus nativitatis'') is a medium-sized shearwater of the tropical Central Pacific. It is a poorly known species due to its remote nesting habits, and it has not been extensively studied at sea either. ...

, white-tailed tropicbird

The white-tailed tropicbird (''Phaethon lepturus'') or yellow-billed tropicbird is a tropicbird. It is the smallest of three closely related seabirds of the tropical oceans and smallest member of the order Phaethontiformes. It is found in the tro ...

, red-tailed tropicbird, brown booby

The brown booby (''Sula leucogaster'') is a large seabird of the booby family Sulidae, of which it is perhaps the most common and widespread species. It has a pantropical range, which overlaps with that of other booby species. The gregarious bro ...

, red-footed booby, masked booby

The masked booby (''Sula dactylatra''), also called the masked gannet or the blue-faced booby, is a large seabird of the booby and gannet family, Sulidae. First described by the French naturalist René-Primevère Lesson in 1831, the masked boob ...

, great frigatebird

The great frigatebird (''Fregata minor'') is a large seabird in the frigatebird family (biology), family. There are major nesting populations in the tropical Pacific Ocean, such as Hawaii and the Galápagos Islands; in the Indian Ocean, colonies ...

, spectacled tern

The spectacled tern (''Onychoprion lunatus''), also known as the grey-backed tern, is a seabird in the family Laridae.

Description

A close relative of the bridled and sooty terns (with which it is sometimes confused), the spectacled tern is l ...

, sooty tern, brown noddy, black noddy, and white tern

The white tern or common white tern (''Gygis alba'') is a small seabird found across the tropical oceans of the world. It is sometimes known as the fairy tern, although this name is potentially confusing as it is also the common name of ''Sternul ...

. It is the world's largest colony of red-tailed tropicbirds, with 10,800 nests in 2020. It is visited by migratory shorebirds

FIle:Vadare - Ystad-2021.jpg, 245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflats in order to foraging, forage for food c ...

, including the Pacific golden plover, wandering tattler

The wandering tattler (''Tringa incana''; formerly ''Heteroscelus incanus'': Pereira & Baker, 2005; Banks ''et al.'', 2006), is a medium-sized wading bird. It is similar in appearance to the closely related gray-tailed tattler, ''T. brevipes'' ...

, bristle-thighed curlew

The bristle-thighed curlew (''Numenius tahitiensis'') is a medium-sized shorebird that breeds in Alaska and winters on tropical Pacific islands.

It is known in Mangareva as ''kivi'' or ''kivikivi'' and in Rakahanga as ''kihi''; it is said to b ...

, ruddy turnstone and sanderling. The island, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognized as an Important Bird Area

An Important Bird and Biodiversity Area (IBA) is an area identified using an internationally agreed set of criteria as being globally important for the conservation of bird populations.

IBA was developed and sites are identified by BirdLife Int ...

by BirdLife International

BirdLife International is a global partnership of non-governmental organizations that strives to conserve birds and their habitats. BirdLife International's priorities include preventing extinction of bird species, identifying and safeguarding i ...

for its seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adaptation, adapted to life within the marine ecosystem, marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent ...

colonies

A colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule, which rules the territory and its indigenous peoples separated from the foreign rulers, the colonizer, and their '' metropole'' (or "mother country"). This separated rule was often or ...

.

Flora

The first list of plants cataloged on Johnston Atoll was published in ''Vascular Plants of Johnston and Wake Islands'' (1931), based on the Tanager Expedition (1923) collections. Three species were described: '' Lepturus repens'', '' Boerhavia diffusa'', and '' Tribulus cistoides''. In the 1940s, when the island was used for aviation activities for the war, '' Pluchea odorata'' was introduced fromHonolulu

Honolulu ( ; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, located in the Pacific Ocean. It is the county seat of the Consolidated city-county, consolidated City and County of Honol ...

.

History

Early history

The first Western record of the atoll was on September 2, 1796, when the Boston-based American

The first Western record of the atoll was on September 2, 1796, when the Boston-based American brig

A brig is a type of sailing vessel defined by its rig: two masts which are both square rig, square-rigged. Brigs originated in the second half of the 18th century and were a common type of smaller merchant vessel or warship from then until the l ...

''Sally'' accidentally grounded on a shoal near the islands. The ship's captain, Joseph Pierpont, published his experience in several American newspapers the following year, accurately portraying Johnston and Sand Island along with part of the reef. Still, he did not name or lay claim to the area. The islands were not officially named until Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

Charles J. Johnston of the Royal Naval ship sighted them on December 14, 1807. The ship's journal recorded: "on the 14th ecembermade a new discovery, viz. two very low islands, in lat. 16° 52′ N. long. 190° 26′ E., having a dangerous reef to the east of them, and the whole not exceeding four miles in extent".

In 1856, the United States enacted the Guano Islands Act, which allowed US citizens to take possession of uninhabited and unclaimed islands containing guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

deposits. Under this act, William Parker and R. F. Ryan chartered the schooner ''Palestine'' specifically to find Johnston Atoll. They located guano on the atoll on March 19, 1858. They proceeded to claim the island as U.S. territory. That same year, S. C. Allen, sailing on the ''Kalama'' under a commission from King Kamehameha IV of Hawaii, sailed to Johnston Atoll, removed the American flag, and claimed the atoll for the Kingdom of Hawaii

The Hawaiian Kingdom, also known as the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ɛ ɐwˈpuni həˈvɐjʔi, was an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country from 1795 to 1893, which eventually encompassed all of the inhabited Hawaii ...

(June 14–19, 1858). Allen named the atoll "Kalama" and the nearby smaller island "Cornwallis."

Returning on July 22, 1858, the captain of the ''Palestine'' again hoisted the American flag to re-assert US sovereignty over the island. On July 27, however, the "derelict and abandoned" atoll was declared part of the domain of Kamehameha IV. On its July visit, however, the ''Palestine'' left two crew members on the island to gather phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

. Later that year, Kamehameha revoked the lease granted to Allen when he learned the atoll had been claimed previously by the United States.

In 1872, Parker's widow sued for title to the island based on her husband's development work there. The US Attorney General denied that claim because Parker had sold his share several years before.

By 1890, the atoll's guano deposits had been almost entirely depleted (mined out) by U.S. interests operating under the Guano Islands Act. In 1892, surveyed and mapped the island to determine its suitability as a telegraph cable station. (This investigation was dropped when it was decided to run the cable via Fanning Island

Tabuaeran, also known as Fanning Island, is an atoll that is part of the Line Islands of the central Pacific Ocean and part of the island nation of Kiribati. The land area is , and the population in 2015 was 2,315. The maximum elevation is abou ...

).

By 1898, the United States had taken possession, and a US Territorial Government was established. On September 11, 1909, this office leased Johnston Atoll to a private citizen, Max Schlemmen of Honolulu, for agricultural purposes. The lease stipulated planting of coconut trees, and that "lessee will not allow use of explosives . . in the water immediately adjacent . . for the purposes of killing or capturing fish . . lessee will not allow destruction or capturing of birds . . " The lessee soon abandoned the project, however, and on August 9, 1918, the lease was reassigned to a Honolulu-based Japanese fishing company. A sampan carried a work party to the island; they built a wood shed on the SE coast of the larger island and ran a small tramline up the slope of the low hill to facilitate the removal of guano. Neither the quantity nor the quality of the guano was sufficient to cover the cost of gathering it, and the project was soon abandoned.

National Wildlife Refuge since 1926

TheTanager Expedition

The ''Tanager'' Expedition was a series of five biological surveys of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands conducted in partnership between the Bureau of Biological Survey and the Bishop Museum, with the assistance of the United States Navy. Four ex ...

was a joint expedition sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Bishop Museum

The Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum, designated the Hawaii State Museum of Natural and Cultural History, is a museum of history and science in the historic Kalihi district of Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu on the Hawaiian island of Oʻahu. Founded in 1 ...

of Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

, which visited the atoll in 1923. The expedition to the atoll consisted of two teams accompanied by destroyer convoys, with the first departing Honolulu on July 7, 1923, aboard the , which conducted the first survey of Johnston Island in the 20th century. Aerial survey and mapping flights over Johnston were conducted with a Douglas DT-2 floatplane

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

carried on her fantail, which was hoisted into the water for takeoff. July 10–22, 1923, the atoll was recorded in a pioneering aerial photograph

Aerial photography (or airborne imagery) is the taking of photographs from an aircraft or other airborne platforms. When taking motion pictures, it is also known as aerial videography.

Platforms for aerial photography include fixed-wing ai ...

y project. The left Honolulu on July 16 and joined up with the ''Whippoorwill'' to complete the survey and then traveled to Wake Island to complete surveys there. Tents were pitched on the southwest beach of fine white sand, and a thorough biological survey was made. Hundreds of sea birds of a dozen kinds were the principal inhabitants, together with lizards, insects, and hermit crabs. The reefs and shallow water abounded with fish and other marine life.

On June 29, 1926, by , President Calvin Coolidge

Calvin Coolidge (born John Calvin Coolidge Jr.; ; July 4, 1872January 5, 1933) was the 30th president of the United States, serving from 1923 to 1929. A Republican Party (United States), Republican lawyer from Massachusetts, he previously ...

established Johnston Island Reservation as a federal bird refuge and placed it under the U.S. Department of Agriculture, as a "refuge and breeding ground for native birds." Johnston Atoll was added to the United States National Wildlife Refuge system in 1926, and renamed the Johnston Island National Wildlife Refuge in 1940. The Johnston Atoll National Wildlife Refuge was established to protect the tropical ecosystem and the wildlife that it harbors. However, the Department of Agriculture had no ships, and the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

was interested in the atoll for strategic reasons, so with on December 29, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed the islands under the "control and jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

for administrative purposes", but subject to use as a refuge and breeding ground for native birds, under the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation ...

.

On February 14, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

issued to create naval defense areas in the central Pacific territories. The proclamation established the "Johnston Island Naval Defensive Sea Area", encompassing the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding the atoll. "Johnston Island Naval Airspace Reservation" was also established to restrict access to the airspace over the naval defense sea area. Only U.S. government ships and aircraft were permitted to enter the naval defense areas at Johnston unless authorized by the Secretary of the Navy

The Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department within the United States Department of Defense. On March 25, 2025, John Phelan was confirm ...

.

In 1990, two full-time U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel, a Refuge Manager and a biologist, were stationed on Johnston Atoll to handle increased biological, contaminant, and resource conflict activities.

After the military mission on the island ended in 2004, the atoll was administered by the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. The outer islets and water rights were managed cooperatively by the Fish and Wildlife Service, with some of the actual Johnston Island land mass remaining under the control of the United States Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

(USAF) for environmental remediation and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) for plutonium cleanup purposes. However, on January 6, 2009, under the authority of section 2 of the Antiquities Act

The Antiquities Act of 1906 (, , ) is an act that was passed by the United States Congress and signed into law by Theodore Roosevelt on June 8, 1906. This law gives the president of the United States the authority to, by presidential proclam ...

, the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument was established by President George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

to administer and protect Johnston Island along with six other Pacific islands. The national monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure. The term may also refer to a sp ...

includes Johnston Atoll National Wildlife Refuge within its boundaries and contains of land and over of water area. The Administration of President Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

in 2014 extended the protected area to encompass the entire Exclusive Economic Zone

An exclusive economic zone (EEZ), as prescribed by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, is an area of the sea in which a sovereign state has exclusive rights regarding the exploration and use of marine natural resource, reso ...

, by banning all commercial fishing activities. Under a 2017 review of all national monuments extended since 1996, then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke

Ryan Keith Zinke ( ; born November 1, 1961) is an American politician and businessman serving as the U.S. representative for since 2023. A member of the Republican Party, Zinke served in the Montana Senate from 2009 to 2013 and as the U.S. re ...

recommended permitting fishing outside the 12-mile limit.

Military control 1934–2004

On December 29, 1934, PresidentFranklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

with transferred control of Johnston Atoll to the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

under the 14th Naval District, Pearl Harbor, to establish an air station, and also to the United States Department of the Interior

The United States Department of the Interior (DOI) is an United States federal executive departments, executive department of the Federal government of the United States, U.S. federal government responsible for the management and conservation ...

to administer the bird refuge. In 1948, the USAF assumed control of the atoll.

During the Operation Hardtack nuclear test series from April 22 to August 19, 1958, the administration of Johnston Atoll was assigned to the Commander of Joint Task Force 7. After the tests were completed, the island reverted to the command of the US Air Force.

From 1963 to 1970, the Navy's Joint Task force 8 and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) held joint operational control of the island during high-altitude nuclear testing operations.

In 1970, operational control was handed back to the Air Force until July 1973, when Defense Special Weapons Agency was given host-management responsibility by the Secretary of Defense. Over the years, sequential descendant organizations have been the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA) from 1959 to 1971, the Defense Nuclear Agency (DNA) from 1971 to 1996, and the Defense Special Weapons Agency (DSWA) from 1996 to 1998. In 1998, Defense Special Weapons Agency and selected elements of the Office of Secretary of Defense were combined to form the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA). In 1999, host-management responsibility transferred from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency once again to the Air Force until the Air Force mission ended in 2004 and the base was closed.

Sand Island seaplane base

In 1935, personnel from the US Navy's Patrol Wing Two carried out some minor construction to develop the atoll for seaplane operation. In 1936, the Navy began the first of many changes to enlarge the atoll's land area. They erected some buildings and a boat landing on Sand Island and blasted coral to clear a seaplane landing. Several seaplanes made flights from Hawaii to Johnston, such as that of a squadron of six aircraft in November 1935.

In November 1939, civilian contractors commenced further work on Sand Island to allow the operation of one squadron of patrol planes with tender support. Part of the lagoon was dredged, and the excavated material was used to make a parking area connected by a causeway to Sand Island. Three seaplane landings were cleared, one by and two cross-landings each by and dredged to a depth of . Sand Island had barracks built for 400 men, a mess hall, an underground hospital, a radio station, water tanks, and a steel control tower. In December 1943 an additional of parking was added to the seaplane base.

On May 26, 1942, a

In 1935, personnel from the US Navy's Patrol Wing Two carried out some minor construction to develop the atoll for seaplane operation. In 1936, the Navy began the first of many changes to enlarge the atoll's land area. They erected some buildings and a boat landing on Sand Island and blasted coral to clear a seaplane landing. Several seaplanes made flights from Hawaii to Johnston, such as that of a squadron of six aircraft in November 1935.

In November 1939, civilian contractors commenced further work on Sand Island to allow the operation of one squadron of patrol planes with tender support. Part of the lagoon was dredged, and the excavated material was used to make a parking area connected by a causeway to Sand Island. Three seaplane landings were cleared, one by and two cross-landings each by and dredged to a depth of . Sand Island had barracks built for 400 men, a mess hall, an underground hospital, a radio station, water tanks, and a steel control tower. In December 1943 an additional of parking was added to the seaplane base.

On May 26, 1942, a United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina wrecked at Johnston Atoll. The Catalina pilot made a normal power landing and immediately applied the throttle for take-off. At about 50 knots, the plane swerved to the left and continued into a violent waterloop. The plane's hull was broken open, and the Catalina sank immediately.

After the war, on March 27, 1949, a PBY-6A Catalina had to make a forced landing during a flight from Kwajalein to Johnston Island. The plane was damaged beyond repair, and the crew of 11 was rescued nine hours later by a Navy ship, which sank the plane using gunfire.

In 1958, a proposed support agreement for Navy Seaplane operations at Johnston Island was under discussion, though it was never completed because a requirement for the operation failed to materialize.

Airfield

By September 1941, construction of an

By September 1941, construction of an airfield

An aerodrome, airfield, or airstrip is a location from which aircraft flight operations take place, regardless of whether they involve air cargo, passengers, or neither, and regardless of whether it is for public or private use. Aerodromes in ...

on Johnston Island commenced. A runway was built with two 400-man barracks, two mess halls, a cold-storage building, an underground hospital, a fresh-water plant, shop buildings, and fuel storage. The runway was complete by December 7, 1941, though in December 1943, the 99th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at the atoll and proceeded to lengthen the runway to . The runway was lengthened and improved as the island was enlarged.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Johnston Atoll was used as a refueling base for submarines and also as an aircraft refueling stop for American bombers transiting the Pacific Ocean, including the Boeing B-29 Enola Gay

The ''Enola Gay'' () is a Boeing B-29 Superfortress bomber, named after Enola Gay Tibbets, the mother of the pilot, Colonel (United States), Colonel Paul Tibbets. On 6 August 1945, during the final stages of World War II, it became the Atomi ...

. By 1944, the atoll was one of the busiest air transport terminals in the Pacific. Air Transport Command

Air Transport Command (ATC) was a United States Air Force unit that was created during World War II as the strategic airlift component of the United States Army Air Forces.

It had two main missions, the first being the delivery of supplies a ...

aeromedical evacuation planes stopped at Johnston en route to Hawaii. Following V-J Day on August 14, 1945, Johnston Atoll saw the flow of men and aircraft coming from the mainland into the Pacific turn around. By 1947, over 1,300 B-29 and B-24

The Consolidated B-24 Liberator is an American heavy bomber, designed by Consolidated Aircraft of San Diego, California. It was known within the company as the Model 32, and some initial production aircraft were laid down as export models desi ...

bombers had passed through the Marianas

The Mariana Islands ( ; ), also simply the Marianas, are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly Volcano#Dormant and reactivated, dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean ...

, Kwajalein, Johnston Island, and Oahu

Oahu (, , sometimes written Oahu) is the third-largest and most populated island of the Hawaiian Islands and of the U.S. state of Hawaii. The state capital, Honolulu, is on Oahu's southeast coast. The island of Oahu and the uninhabited Northwe ...

en route to Mather Field and civilian life.

Following World War II, Johnston Atoll Airport was used commercially by Continental Air Micronesia, touching down between Honolulu and Majuro

Majuro (; Marshallese language, Marshallese: ' ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the Marshall Islands. It is also a large coral atoll of 64 islands in the Pacific Ocean. It forms a legislative district of the Ratak Chain, Ratak ( ...

. When the aircraft landed, soldiers surrounded the aircraft, and passengers were not allowed to leave the aircraft. Aloha Airlines also made weekly scheduled flights to the island carrying civilian and military personnel. In the 1990s, there were flights almost daily. Some days saw up to three arrivals. Just before movement of the chemical munitions to Johnston Atoll, the Surgeon General, Public Health Service, reviewed the shipment and the Johnston Atoll storage plans. His recommendations caused the Secretary of Defense to issue instructions in December 1970 to suspend missile launches and all non-essential aircraft flights. As a result, Air Micronesia's service was immediately discontinued, and missile firings were terminated, except for two 1975 satellite launches deemed critical to the island's mission.

There were many times when the runway was needed for emergency landings for civil and military aircraft. When the runway was decommissioned, it could no longer be a potential emergency landing place when planning flight routes across the Pacific Ocean. As of 2003, the airfield at Johnston Atoll consisted of an unmaintained closed single asphalt/concrete runway 5/23, a parallel taxiway, and a large paved ramp along the southeast side of the runway.

World War II 1941–1945

In February 1941, Johnston Atoll was designated a Naval Defensive Sea Area and Airspace Reservation. On the day the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, was out of her home port ofPearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

to make a simulated bombardment at Johnston Island. Japan's strike at Pearl Harbor occurred as the ship was unloading marines, civilians, and stores on the atoll. On December 15, 1941, the atoll was shelled outside the reef by a Japanese submarine, which had been part of the attack on Pearl Harbor eight days earlier. Several buildings, including the power station, were hit, but no personnel were injured. Additional Japanese shelling occurred on December 22 and 23, 1941. On all occasions, Johnston Atoll's coastal artillery returned fire, driving off the sub.

In July 1942, the civilian contractors at the atoll were replaced by 500 men from the 5th and 10th Naval Construction Battalions, who expanded the fuel storage and water production at the base and built additional facilities. The 5th Battalion departed in January 1943. In December 1943, the 99th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at the atoll. It proceeded to lengthen the runway to and add of parking to the seaplane base.

Coast Guard mission 1957–1992

United States Coast Guard

The United States Coast Guard (USCG) is the maritime security, search and rescue, and Admiralty law, law enforcement military branch, service branch of the armed forces of the United States. It is one of the country's eight Uniformed services ...

(USCG) to operate and maintain a Long Range Aid to Navigation (LORAN) transmitting station on Johnston Atoll. Two years later, in December 1959, the Secretary of Defense approved the Secretary of the Treasury's request to use Sand Island for U.S. Coast Guard LORAN A and C station sites. The USCG was granted permission to install a LORAN A and C station on Sand Island to be staffed by U.S. Coast Guard personnel through June 30, 1992. The permit for a LORAN station to operate on Johnston Island was terminated in 1962. On November 1, 1957, a new United States Coast Guard LORAN-A station was commissioned. By 1958, the Coast Guard LORAN Station at Johnston Island began transmitting on a 24-hour basis, thus establishing a new LORAN rate in the Central Pacific. The new rate between Johnston Island and French Frigate Shoals

The French Frigate Shoals (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: Kānemilohai) is the largest atoll in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, located about northwest of Honolulu, Hawaii, Honolulu. Its name commemorates France, French explorer Jean-Fran ...

gave a higher order of accuracy for fixing positions in the steamship lanes from Oahu, Hawaii, to Midway Island. In the past, this was impossible in some areas along this important shipping route. The original U.S. Coast Guard LORAN-A Station on Johnston Island ceased operations on June 30, 1961, when the new station on nearby Sand Island began transmitting using a larger 180-foot antenna.

The LORAN-C station was disestablished on July 1, 1992, and all Coast Guard personnel, electronic equipment, and property departed that month. Buildings on Sand Island were transferred to other activities. LORAN whip antennas on Johnston and Sand Islands were removed, and the 625-foot LORAN tower and antenna were demolished on December 3, 1992. The LORAN A and C stations and buildings on Sand Island were then dismantled and removed.

National nuclear weapon test site 1958–1963

Successes

Between 1958 and 1975, Johnston Atoll was used as an American nationalnuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine the performance of nuclear weapons and the effects of their explosion. Nuclear testing is a sensitive political issue. Governments have often performed tests to signal strength. Bec ...

site for atmospheric and extremely high-altitude nuclear explosions in outer space. In 1958, Johnston Atoll was the location of the two "Hardtack I" nuclear tests firings. One conducted August 1, 1958, was codenamed " Hardtack Teak", and one conducted August 12, 1958, was codenamed "Orange." Both tests detonated 3.8- megaton hydrogen bombs launched to high altitudes by rockets from Johnston Atoll.

Johnston Island was also used as the launch site of 124 sounding rocket

A sounding rocket or rocketsonde, sometimes called a research rocket or a suborbital rocket, is an instrument-carrying rocket designed to take measurements and perform scientific experiments during its sub-orbital flight. The rockets are often ...

s going up as high as . These carried scientific instruments and telemetry

Telemetry is the in situ collection of measurements or other data at remote points and their automatic transmission to receiving equipment (telecommunication) for monitoring. The word is derived from the Greek roots ''tele'', 'far off', an ...

equipment, either in support of the nuclear bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear exp ...

tests or in experimental antisatellite technology.

Eight PGM-17 Thor

The PGM-17A Thor was the first operative ballistic missile of the United States Air Force (USAF). It was named after the Thor, Norse god of thunder. It was deployed in the United Kingdom between 1959 and September 1963 as an intermediate-range b ...

missiles deployed by the U.S. Air Force (USAF) were launched from Johnston Island in 1962 as part of " Operation Fishbowl," a part of " Operation Dominic" nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific. The first launch in "Operation Fishbowl" was a successful research and development launch with no warhead

A warhead is the section of a device that contains the explosive agent or toxic (biological, chemical, or nuclear) material that is delivered by a missile, rocket (weapon), rocket, torpedo, or bomb.

Classification

Types of warheads include:

*E ...

. In the end, "Operation Fishbowl" produced four successful high-altitude detonations: " Starfish Prime," "Checkmate

Checkmate (often shortened to mate) is any game position in chess and other chess-like games in which a player's king is in check (threatened with ) and there is no possible escape. Checkmating the opponent wins the game.

In chess, the king is ...

," " Bluegill Triple Prime," and " Kingfish." In addition, it produced one atmospheric nuclear explosion, "Tightrope

Tightrope walking, also called funambulism, is the skill of walking along a thin wire or rope. It has a long tradition in various countries and is commonly associated with the circus. Other skills similar to tightrope walking include slack rope ...

."

On July 9, 1962, "Starfish Prime" had a 1.4- megaton explosion, using a W49 warhead at an altitude of about . It created a very brief fireball visible over a wide area, plus bright artificial auroras visible in Hawaii for several minutes. "Starfish Prime" also produced an electromagnetic pulse

An electromagnetic pulse (EMP), also referred to as a transient electromagnetic disturbance (TED), is a brief burst of electromagnetic energy. The origin of an EMP can be natural or artificial, and can occur as an electromagnetic field, as an ...

that disrupted some electric power

Electric power is the rate of transfer of electrical energy within a electric circuit, circuit. Its SI unit is the watt, the general unit of power (physics), power, defined as one joule per second. Standard prefixes apply to watts as with oth ...

and communication system

A communications system is a collection of individual telecommunications networks systems, relay stations, tributary stations, and terminal equipment usually capable of interconnection and interoperation to form an integrated whole. Communic ...

s in Hawaii. It pumped enough radiation into the Van Allen belts

The Van Allen radiation belt is a zone of energy, energetic charged particles, most of which originate from the solar wind, that are captured by and held around a planet by that planet's magnetosphere. Earth has two such belts, and sometimes ot ...

to destroy or damage seven satellite

A satellite or an artificial satellite is an object, typically a spacecraft, placed into orbit around a celestial body. They have a variety of uses, including communication relay, weather forecasting, navigation ( GPS), broadcasting, scient ...

s in orbit.

The final Fishbowl launch that used a Thor missile carried the "Kingfish" 400-kiloton warhead up to its detonation altitude. Although it was officially one of the Operation Fishbowl tests, it is sometimes not listed among high-altitude nuclear tests because of its lower detonation altitude. "Tightrope" was the final test of Operation Fishbowl and detonated on November 3, 1962. It launched on a nuclear-armed Nike-Hercules missile and was detonated at a lower altitude than the other tests:

"At Johnston Island, there was an intense white flash. Even with high-density goggles, the burst was too bright to view, even for a few seconds. A distinct thermal pulse was felt on bare skin. A yellow-orange disc was formed, and transformed itself into a purple doughnut. A glowing purple cloud was faintly visible for a few minutes." Defense Nuclear Agency. Operation Dominic I 1962. Report DNA 6040F. (First published as an unclassified document on February 1, 1983.) Page 247. The nuclear yield was reported in most official documents as "less than 20 kilotons." One report by the U.S. government reported the yield of the "Tightrope" test as ten kilotons. Seven sounding rockets were launched from Johnston Island in support of the ''Tightrope'' test, and this was the final American nuclear atmospheric test.

Failures

Bluegill

The bluegill (''Lepomis macrochirus''), sometimes referred to as "bream", "brim", "sunny", or, in Texas, "copper nose", is a species of North American freshwater fish, native to and commonly found in streams, rivers, lakes, ponds and wetlands ea ...

", carried an active warhead. Bluegill was "lost" by a defective range safety tracking radar and had to be destroyed 10 minutes after liftoff, even though it probably ascended successfully. The subsequent nuclear weapon launch failures from Johnston Atoll caused severe contamination to the island and surrounding areas with weapons-grade

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon and has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nuc ...

plutonium

Plutonium is a chemical element; it has symbol Pu and atomic number 94. It is a silvery-gray actinide metal that tarnishes when exposed to air, and forms a dull coating when oxidized. The element normally exhibits six allotropes and four ...

and americium

Americium is a synthetic element, synthetic chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Am and atomic number 95. It is radioactive and a transuranic member of the actinide series in the periodic table, located under the lanthanide element e ...

that remains an issue to this day.

The failure of the "Bluegill" launch created in effect a dirty bomb but did not release the nuclear warhead's plutonium debris onto Johnston Atoll as the missile fell into the ocean south of the island and was not recovered. However, the "Starfish", "Bluegill Prime", and "Bluegill Double Prime" test launch failures in 1962 scattered radioactive debris over Johnston Island contaminating it, the lagoon, and Sand Island with plutonium for decades.

"Starfish

Starfish or sea stars are Star polygon, star-shaped echinoderms belonging to the class (biology), class Asteroidea (). Common usage frequently finds these names being also applied to brittle star, ophiuroids, which are correctly referred to ...

", a high altitude Thor launched nuclear test scheduled for June 20, 1962, was the first to contaminate the atoll. The rocket with the 1.45-megaton Starfish device (W49 warhead and the MK-4 re-entry vehicle

Atmospheric entry (sometimes listed as Vimpact or Ventry) is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. Atmospheric entry may be ''uncontrolled entry ...

) on its nose was launched that evening, but the Thor missile engine cut out only 59 seconds after launch. The range safety officer sent a destruct signal 65 seconds after launch, and the missile was destroyed at approximately altitude—the warhead high explosive detonated in a 1-point safe fashion, destroying the warhead without producing nuclear yield. Large pieces of the plutonium-contaminated missile, including fragments of the warhead, booster rocket, engine, re-entry vehicle, and missile parts, fell back on Johnston Island. More wreckage, along with plutonium contamination, was found on nearby Sand Island.

" Bluegill Prime," the second attempt to launch the payload, which failed last time, was scheduled for 23:15 (local) on July 25, 1962. It, too, was a genuine disaster and caused the most severe plutonium contamination on the island. The Thor missile carried one pod, two re-entry vehicles, and the W50 nuclear warhead. The missile engine malfunctioned immediately after ignition, and the range safety officer fired the destruct system while the missile was still on the launch pad. The Johnston Island launch complex was demolished in the subsequent explosions and fire, which burned through the night. The launch emplacement and portions of the island were contaminated with radioactive plutonium spread by the blast, fire, and wind-blown smoke.

Afterward, the Johnston Island launch complex was heavily damaged and contaminated with plutonium. Missile launches and nuclear testing halted until the radioactive debris was dumped, soils were recovered, and the launch emplacement rebuilt. Before tests could resume, three months of repairs, decontamination, and rebuilding of the LE1 and the backup pad LE2 were necessary. To continue with the testing program, U.S. troops were sent in to do a rapid cleanup. The troops scrubbed down the revetments and launch pad, carted away debris, and removed the top layer of coral around the contaminated launch pad. The plutonium-contaminated rubbish was dumped in the lagoon, polluting the surrounding marine environment. Over 550 drums of contaminated material were dumped in the ocean off Johnston from 1964 to 1965. At the time of the Bluegill Prime disaster, a bulldozer and grader scraped the top fill around the launch pad. It was then dumped into the lagoon to make a ramp so the rest of the debris could be loaded onto the landing craft to be dumped into the ocean. An estimated 10 percent of the plutonium from the test device was in the fill used to make the ramp. Then, the ramp was covered and placed into a landfill on the island during 1962 dredging to extend the island. The lagoon was again dredged in 1963–1964 and used to expand Johnston Island from , recontaminating additional portions of the island.

Afterward, the Johnston Island launch complex was heavily damaged and contaminated with plutonium. Missile launches and nuclear testing halted until the radioactive debris was dumped, soils were recovered, and the launch emplacement rebuilt. Before tests could resume, three months of repairs, decontamination, and rebuilding of the LE1 and the backup pad LE2 were necessary. To continue with the testing program, U.S. troops were sent in to do a rapid cleanup. The troops scrubbed down the revetments and launch pad, carted away debris, and removed the top layer of coral around the contaminated launch pad. The plutonium-contaminated rubbish was dumped in the lagoon, polluting the surrounding marine environment. Over 550 drums of contaminated material were dumped in the ocean off Johnston from 1964 to 1965. At the time of the Bluegill Prime disaster, a bulldozer and grader scraped the top fill around the launch pad. It was then dumped into the lagoon to make a ramp so the rest of the debris could be loaded onto the landing craft to be dumped into the ocean. An estimated 10 percent of the plutonium from the test device was in the fill used to make the ramp. Then, the ramp was covered and placed into a landfill on the island during 1962 dredging to extend the island. The lagoon was again dredged in 1963–1964 and used to expand Johnston Island from , recontaminating additional portions of the island.

On October 15, 1962, the " Bluegill Double Prime" test also misfired. During the test, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned 90 seconds into the flight. U.S. Defense Department officials confirm that the rocket's destruction contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

In 1963, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which contained a provision known as "Safeguard C". Safeguard C was the basis for maintaining Johnston Atoll as a "ready to test" above-ground nuclear testing site should atmospheric nuclear testing ever be deemed necessary again. In 1993, Congress appropriated no funds for the Johnston Atoll "Safeguard C" mission, ending it.

On October 15, 1962, the " Bluegill Double Prime" test also misfired. During the test, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned 90 seconds into the flight. U.S. Defense Department officials confirm that the rocket's destruction contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

In 1963, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which contained a provision known as "Safeguard C". Safeguard C was the basis for maintaining Johnston Atoll as a "ready to test" above-ground nuclear testing site should atmospheric nuclear testing ever be deemed necessary again. In 1993, Congress appropriated no funds for the Johnston Atoll "Safeguard C" mission, ending it.

Anti-satellite mission 1962–1975

Program 437 turned thePGM-17 Thor

The PGM-17A Thor was the first operative ballistic missile of the United States Air Force (USAF). It was named after the Thor, Norse god of thunder. It was deployed in the United Kingdom between 1959 and September 1963 as an intermediate-range b ...

into an operational anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon system, a capability that was kept top secret even after it was deployed. The Program 437 mission was approved for development by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

Robert Strange McNamara (; June 9, 1916 – July 6, 2009) was an American businessman and government official who served as the eighth United States secretary of defense from 1961 to 1968 under presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ...

on November 20, 1962, and based at the atoll. Program 437 used modified Thor missiles that had been returned from deployment in Great Britain and was the second deployed U.S. operational nuclear anti-satellite operation. Eighteen more suborbital Thor launches took place from Johnston Island from 1964 to 1975 in support of Program 437. In 1965–1966, four Program 437 Thors were launched with 'Alternate Payloads' for satellite inspection. This was an elaboration of the system to allow visual verification of the target before destroying it. These flights may have been related to the late 1960s Program 922, a non-nuclear version of Thor with infrared homing and a high-explosive warhead. Thors were active near the two Johnston Island launch pads after 1964. However, partly because of the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

, in October 1970, the Department of Defense transferred Program 437 to standby status as an economic measure. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks

The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (SALT) were two rounds of bilateral conferences and corresponding international treaties involving the United States and the Soviet Union. The Cold War superpowers dealt with arms control in two rounds of ...

led to Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty

The Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, also known as the ABM Treaty or ABMT, was an arms control treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union on the limitation of the anti-ballistic missile (ABM) systems used in defending areas against ball ...

that prohibited 'interference with national means of verification', which meant that ASATs were not allowed, by treaty, to attack Soviet spy satellites. Thors were removed from Johnston Atoll and were stored in mothballed war-reserve condition at Vandenberg Air Force Base

Vandenberg may refer to:

* Vandenberg (surname), including a list of people with the name

* USNS ''General Hoyt S. Vandenberg'' (T-AGM-10), transport ship in the United States Navy, sank as an artificial reef in Key West, Florida

* Vandenberg S ...

from 1970 until the anti-satellite mission of Johnston Island facilities ceased on August 10, 1974. The program was officially discontinued on April 1, 1975, when any possibility of restoring the ASAT program was finally terminated. Eighteen Thor launches in support of the Program 437 Alternate Payload (AP) mission took place from Johnston Atoll's Launch emplacements.

Two Thor missiles were launched from the Island in late 1975, months after the "officially discontinued" date.

Baker–Nunn satellite tracking camera station

TheSpace Detection and Tracking System Space Detection and Tracking System, or SPADATS, was built in 1960 to integrate defense systems built by different branches of the United States Armed Forces and was placed under North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). The Air Force had a ...

or SPADATS was operated by North American Aerospace Defense Command

North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD ; , CDAAN), known until March 1981 as the North American Air Defense Command, is a Combined operations, combined organization of the United States and Canada that provides aerospace warning, air ...

(NORAD

North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD ; , CDAAN), known until March 1981 as the North American Air Defense Command, is a combined organization of the United States and Canada that provides aerospace warning, air sovereignty, and pr ...

) along with the U.S. Air Force Spacetrack system, The Navy Space Surveillance System and Canadian Forces Air Defense Command Satellite Tracking Unit. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory

The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (SAO) is a research institute of the Smithsonian Institution, concentrating on Astrophysics, astrophysical studies including Galactic astronomy, galactic and extragalactic astronomy, cosmology, Sun, solar ...

also operated a dozen 3.5 ton Baker-Nunn Camera

A Schmidt camera, also referred to as the Schmidt telescope, is a catadioptric Astrophotography, astrophotographic Optical telescope, telescope designed to provide wide Field of view, fields of view with limited Aberration in optical systems, abe ...

systems (none at Johnston) for cataloging of artificial satellites. The U.S. Air Force had ten Baker-Nunn camera stations worldwide, mostly from 1960 to 1977, with a phase-out beginning in 1964.

The Baker-Nunn space camera station was constructed on Sand Island. It was functioning by 1965. USAF 18th Surveillance Squadron operated the Baker-Nunn camera at a station built along the causeway on Sand Island until 1975 when a contract to operate the four remaining Air Force stations was awarded to Bendix Field Engineering Corporation. In about 1977, the camera at Sand Island was moved to Daegu

Daegu (; ), formerly spelled Taegu and officially Daegu Metropolitan City (), is a city in southeastern South Korea. It is the third-largest urban agglomeration in South Korea after Seoul and Busan; the fourth-largest List of provincial-level ci ...