Italian partisans on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Italian Resistance ( ), or simply ''La'' , consisted of all the

The Italian Resistance has its roots in

The Italian Resistance has its roots in  In Italy, Mussolini's

In Italy, Mussolini's  After the murder of the socialist deputy

After the murder of the socialist deputy

Armed resistance to the German occupation following the

Armed resistance to the German occupation following the

One of the most important episodes of resistance by Italian Armed Forces after the armistice was the Battle of Piombino in

One of the most important episodes of resistance by Italian Armed Forces after the armistice was the Battle of Piombino in

In the days following 8 September 1943 most servicemen, left without orders from higher echelons (due to Wehrmacht units ceasing Italian radio communications), were disarmed and shipped to POW camps in the

In the days following 8 September 1943 most servicemen, left without orders from higher echelons (due to Wehrmacht units ceasing Italian radio communications), were disarmed and shipped to POW camps in the

Women played a large role. After the war, about 35,000 Italian women were recognised as female ''partigiane combattenti'' (partisan combatants) and 20,000 as ''patriote'' (patriots); they broke into these groups based on their activities. The majority were between 20 and 29. They were generally kept separate from male partisans. Few were attached to brigades and were even rarer in mountain brigades. Female countryside volunteers were generally rejected. Women still served in large numbers and had significant influence.

The groups were formed collaboratively by women from diverse political backgrounds. Prominent participants included communists Giovanna Barcellona, Lina Fibbi, Marisa Diena, and Caterina Picolato; socialists Laura Conti and Lina Merlin; actionists Elena Dreher and

Women played a large role. After the war, about 35,000 Italian women were recognised as female ''partigiane combattenti'' (partisan combatants) and 20,000 as ''patriote'' (patriots); they broke into these groups based on their activities. The majority were between 20 and 29. They were generally kept separate from male partisans. Few were attached to brigades and were even rarer in mountain brigades. Female countryside volunteers were generally rejected. Women still served in large numbers and had significant influence.

The groups were formed collaboratively by women from diverse political backgrounds. Prominent participants included communists Giovanna Barcellona, Lina Fibbi, Marisa Diena, and Caterina Picolato; socialists Laura Conti and Lina Merlin; actionists Elena Dreher and

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-476-2051-39A, Italien, Rom, erhängte Frau, deutsche Soldaten.jpg, A woman executed by public hanging in a street of

Not all resistance members were Italians; many foreigners had escaped

Not all resistance members were Italians; many foreigners had escaped

On 19 April 1945, the CLN called for an insurrection (the 25 April uprising). In

On 19 April 1945, the CLN called for an insurrection (the 25 April uprising). In

A score-settling campaign () ensued against pro-German collaborators, thousands of whom were rounded up by the vengeful partisans. Controversially, many of those detainees were speedily court martialed, condemned and shot, or killed without trial. Minister of Interior Mario Scelba later put the number of the victims of such executions at 732, but other estimates were much higher. Partisan leader Ferruccio Parri, who briefly served as Prime Minister after the war in 1945, said thousands were killed. Some partisans, such as perpetrators of the Schio massacre, were tried by an Allied Military Court.

During the waning hours of the war, Mussolini, accompanied by Marshal Graziani, headed to Milan to meet with Cardinal

A score-settling campaign () ensued against pro-German collaborators, thousands of whom were rounded up by the vengeful partisans. Controversially, many of those detainees were speedily court martialed, condemned and shot, or killed without trial. Minister of Interior Mario Scelba later put the number of the victims of such executions at 732, but other estimates were much higher. Partisan leader Ferruccio Parri, who briefly served as Prime Minister after the war in 1945, said thousands were killed. Some partisans, such as perpetrators of the Schio massacre, were tried by an Allied Military Court.

During the waning hours of the war, Mussolini, accompanied by Marshal Graziani, headed to Milan to meet with Cardinal

Today's Italian constitution is the result of the work of the

Today's Italian constitution is the result of the work of the

Italy , European Resistance Archive

ANPI – Associazione Nazionale Partigiani d'Italia

ANCFARGL – Associazione Nazionale Combattenti Forze Armate Regolari Guerra di Liberazione

INSMLI – Istituto Nazionale per la Storia del Movimento di Liberazione in Italia

Il portale della guerra di LiberazioneAnarchist partisans in the Italian Resistance

{{Authority control Anti-fascism in Italy Modern history of Italy World War II resistance movements

Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, a Romance ethnic group related to or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance languag ...

resistance groups who fought the occupying forces of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

and the fascist collaborationists of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

from 1943 to 1945. As a diverse anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

and anti-Nazist movement and organisation, the opposed Nazi Germany and its Fascist puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government is a State (polity), state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside Power (international relations), power and subject to its ord ...

regime, the Italian Social Republic, which the Germans created following the Nazi German invasion and military occupation

Military occupation, also called belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is temporary hostile control exerted by a ruling power's military apparatus over a sovereign territory that is outside of the legal boundaries of that ruling pow ...

of Italy by the and the from 8 September 1943 until 25 April 1945.

General underground Italian opposition to the Fascist Italian government existed even before World War II, but open and armed resistance followed the German invasion of Italy on 8 September 1943: in Nazi-occupied Italy, the Italian Resistance fighters, known as the ( partisans), fought a ('national liberation war') against the invading German forces; in this context, the anti-fascist of the Italian Resistance also simultaneously participated in the Italian Civil War

The Italian Civil War (, ) was a civil war in the Kingdom of Italy fought during the Liberation of Italy, Italian campaign of World War II between Italian fascists and Italian resistance movement, Italian partisans (mostly politically organized ...

, fighting against the Italian Fascist

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

s of the collaborationist Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

.

The Resistance was a diverse coalition of various Italian political parties, independent resistance fighters and soldiers, and partisan brigades and militias. The modern Italian Republic

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

was declared to be founded on the struggle of the Resistance: the Constituent Assembly

A constituent assembly (also known as a constitutional convention, constitutional congress, or constitutional assembly) is a body assembled for the purpose of drafting or revising a constitution. Members of a constituent assembly may be elected b ...

was mostly composed of representatives of the parties that had given life to the Italian Resistance's National Liberation Committee

The National Liberation Committee (, CLN) was a political umbrella organization and the main representative of the Italian resistance movement fighting against the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationist forces of the ...

. These former Italian Resistance fighters wrote the Constitution of Italy

The Constitution of the Italian Republic () was ratified on 22 December 1947 by the Constituent Assembly of Italy, Constituent Assembly, with 453 votes in favour and 62 against, before coming into force on 1 January 1948, one century after the p ...

at the end of the war based on a compromissory synthesis of their Resistance parties' respective principles of democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

and anti-fascism

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

.

Background

anti-fascism

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

, which progressively developed in the period from the mid-1920s, when weak forms of opposition to the fascist regime already existed, until the beginning of World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Furthermore, in the memory of the partisan fighters, especially those of communist and socialist inspiration, the memory of the '' Biennio Rosso'' and of the violent struggles against the fascist squads in the period 1919–1922, considered by some exponents of the left-wing parties (among which Palmiro Togliatti

Palmiro Michele Nicola Togliatti (; 26 March 1893 – 21 August 1964) was an Italian politician and statesman, leader of Italy's Italian Communist Party, Communist party for nearly forty years, from 1927 until his death. Born into a middle-clas ...

himself) a true "civil war" in defence of the popular classes against the reactionary forces.

In Italy, Mussolini's

In Italy, Mussolini's Fascist

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural soci ...

regime used the term ''anti-fascist'' to describe its opponents. Mussolini's secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

was officially known as the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism

The OVRA, unofficially known as the Organization for Vigilance and Repression of Anti-Fascism (), was the secret police of the Kingdom of Italy during the reign of King Victor Emmanuel III. It was founded in 1927 under the regime of Italian fas ...

. During the 1920s in the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, anti-fascists, many of them from the labor movement

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considere ...

, fought against the violent Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security (, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts (, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party, known as the Squadrismo, and after 1923 an all-vo ...

and against the rise of the fascist leader Benito Mussolini. After the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

(PSI) signed a pacification pact with Mussolini and his Fasces of Combat on 3 August 1921, and trade unions adopted a legalist and pacified strategy, members of the workers' movement who disagreed with this strategy formed '' Arditi del Popolo''.

The Italian General Confederation of Labour

The Italian General Confederation of Labour (, , CGIL ) is a national trade union centre in Italy. It was formed by an agreement between socialists, communists, and Christian democrats in the "Pact of Rome" of June 1944. In 1950, socialists and ...

(CGL) and the PSI refused to officially recognize the anti-fascist militia and maintained a non-violent, legalist strategy, while the Communist Party of Italy

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

(PCd'I) ordered its members to quit the organization. The PCd'I organized some militant groups, but their actions were relatively minor. The Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni, who exiled himself to Argentina following the 1922 March on Rome

The March on Rome () was an organized mass demonstration in October 1922 which resulted in Benito Mussolini's National Fascist Party (, PNF) ascending to power in the Kingdom of Italy. In late October 1922, Fascist Party leaders planned a march ...

, organized several bombings against the Italian fascist community. The Italian liberal anti-fascist Benedetto Croce

Benedetto Croce, ( , ; 25 February 1866 – 20 November 1952)

was an Italian idealist philosopher, historian, and politician who wrote on numerous topics, including philosophy, history, historiography, and aesthetics. A Cultural liberalism, poli ...

wrote his '' Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals'', which was published in 1925. Other notable Italian liberal anti-fascists around that time were Piero Gobetti and Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Alberto Rosselli (16 November 18999 June 1937) was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, non-Marxist socialism inspir ...

.

After the murder of the socialist deputy

After the murder of the socialist deputy Giacomo Matteotti

Giacomo Matteotti (; 22 May 1885 – 10 June 1924) was an Italian socialist politician and secretary of the Unitary Socialist Party (PSU). He was elected deputy of the Chamber of Deputies three times, in 1919, 1921 and in 1924. On 30 May 19 ...

(1924) and the decisive assumption of responsibility by Mussolini, the process of totalitarianization of the State began in the Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, which will give rise to ever greater control and severe persecution of opponents, at risk of imprisonment and confinement.

The anti-fascists therefore organized themselves clandestinely in Italy and abroad, creating with great difficulty a rudimentary network of connections, which however did not produce significant practical results, remaining fragmented into small uncoordinated groups, incapable of attacking or threatening the regime, if some attacks carried out in particular by anarchists are excluded. Their activity was limited to the ideological side; the production of writings was copious, particularly among the anti-fascist exile communities, which however did not reach the masses and did not influence public opinion.

Concentrazione Antifascista Italiana

(CAI; Italian Anti-Fascist Concentration), officially known as (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. B ...

(), officially known as Concentrazione d'Azione Antifascista (Anti-Fascist Action Concentration), was an Italian coalition of Anti-Fascist groups which existed from 1927 to 1934. Founded in Nérac

Nérac (; , ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Lot-et-Garonne Departments of France, department, Southwestern France. The composer and organist Louis Raffy was born in Nérac, as was the former Arsenal F.C., Arsenal and FC Girondins de Bo ...

, France, by expatriate Italians, the CAI was an alliance of non-communist anti-fascist forces (republican, socialist, nationalist) trying to promote and to coordinate expatriate actions to fight fascism in Italy; they published a propaganda paper entitled ''La Libertà''.

Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; ) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The movement was cofounded by ...

() was an Italian anti-fascist

Anti-fascism is a political movement in opposition to fascist ideologies, groups and individuals. Beginning in European countries in the 1920s, it was at its most significant shortly before and during World War II, where the Axis powers were op ...

resistance movement

A resistance movement is an organized group of people that tries to resist or try to overthrow a government or an occupying power, causing disruption and unrest in civil order and stability. Such a movement may seek to achieve its goals through ei ...

, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The movement was cofounded by Carlo Rosselli

Carlo Alberto Rosselli (16 November 18999 June 1937) was an Italian political leader, journalist, historian, philosopher and anti-fascist activist, first in Italy and then abroad. He developed a theory of reformist, non-Marxist socialism inspir ...

, Ferruccio Parri, who later became Prime Minister of Italy

The prime minister of Italy, officially the president of the Council of Ministers (), is the head of government of the Italy, Italian Republic. The office of president of the Council of Ministers is established by articles 92–96 of the Co ...

, and Sandro Pertini

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio "Sandro" Pertini (; 25 September 1896 – 24 February 1990) was an Italian socialist politician and statesman who served as President of Italy from 1978 to 1985.

Early life

Born in Stella (province of Savona) as t ...

, who became President of Italy

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Politics of Italy, Italian politics comply with the Consti ...

, were among the movement's leaders. The movement's members held various political beliefs but shared a belief in active, effective opposition to fascism, compared to the older Italian anti-fascist parties. ''Giustizia e Libertà'' also made the international community aware of the realities of fascism in Italy, thanks to the work of Gaetano Salvemini

Gaetano Salvemini (; 8 September 1873 – 6 September 1957) was an Italian socialist and anti-fascist politician, historian, and writer. Born into a family of modest means, he became a historian of note whose work drew attention in Italy and ab ...

.

Some historians have also underlined how the Resistance movement may have had links with the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

, in particular with those who had served in the International Brigades

The International Brigades () were soldiers recruited and organized by the Communist International to assist the Popular Front (Spain), Popular Front government of the Second Spanish Republic during the Spanish Civil War. The International Bri ...

. Many Italian anti-fascists participated in the Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War () was a military conflict fought from 1936 to 1939 between the Republican faction (Spanish Civil War), Republicans and the Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War), Nationalists. Republicans were loyal to the Left-wing p ...

with the hope of setting an example of armed resistance to Franco's dictatorship against Mussolini's regime; hence their motto: "Today in Spain, tomorrow in Italy".

Resistance by the Italian Armed Forces

In Italy

Rome

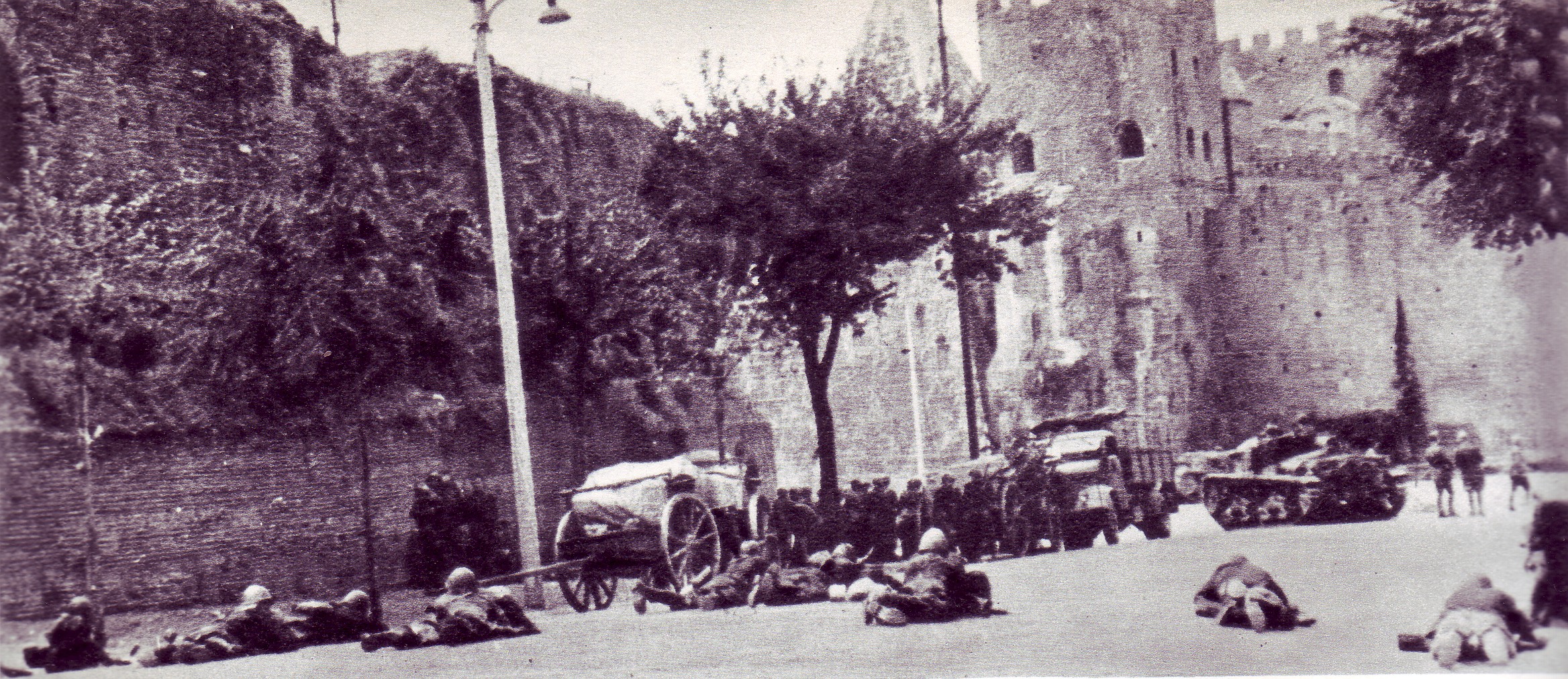

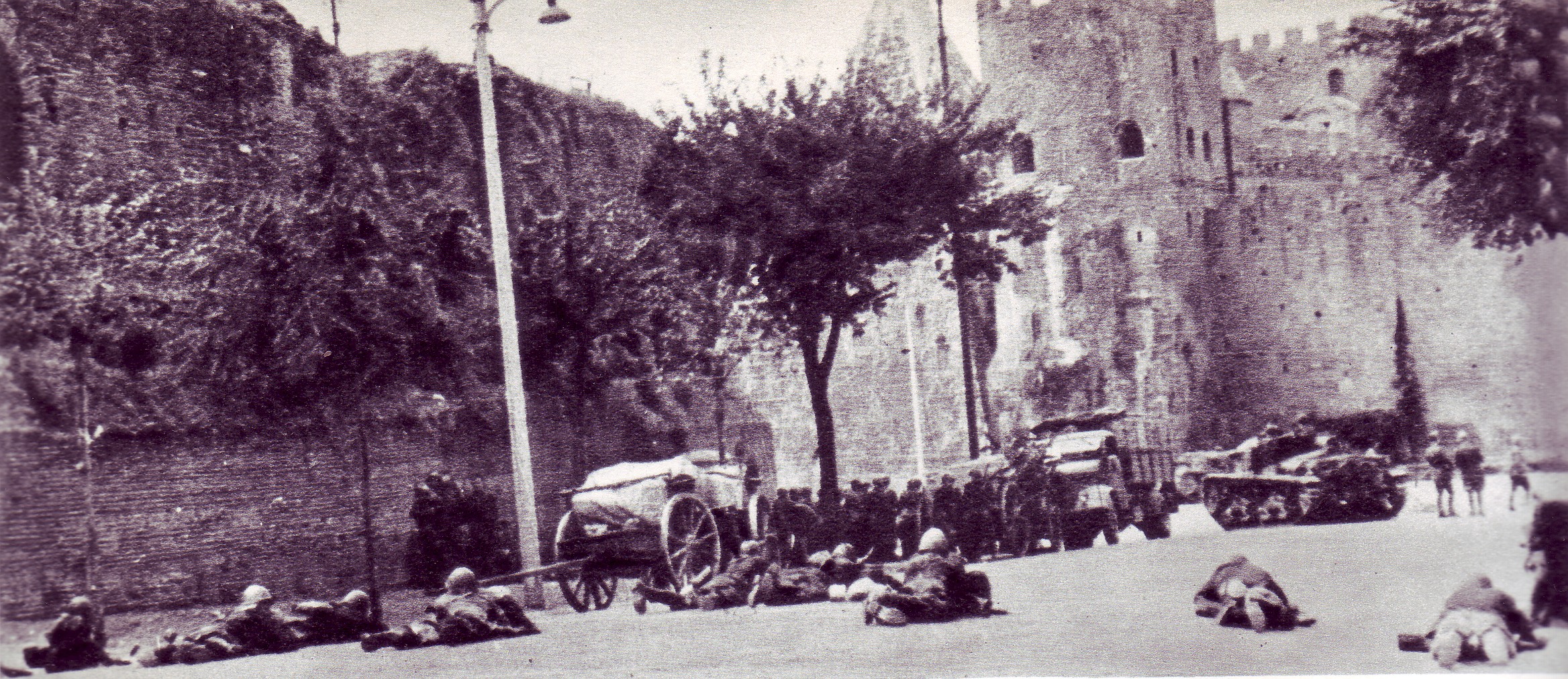

Armed resistance to the German occupation following the

Armed resistance to the German occupation following the armistice between Italy and Allied armed forces

The Armistice of Cassibile (Italian language, Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Kingdom of Italy, Italy and the Allies of World War II, Allies, marking the end of hostilities between It ...

of 3 September 1943 partially began with Italian regular forces: the Italian Armed Forces

The Italian Armed Forces (, ) encompass the Italian Army, the Italian Navy and the Italian Air Force. A fourth Military branch, branch of the armed forces, known as the Carabinieri, take on the role as the nation's Gendarmerie, military police an ...

and the Carabinieri

The Carabinieri (, also , ; formally ''Arma dei Carabinieri'', "Arm of Carabineers"; previously ''Corpo dei Carabinieri Reali'', "Royal Carabineers Corps") are the national gendarmerie of Italy who primarily carry out domestic and foreign poli ...

military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. Not to be confused with civilian police, who are legally part of the civilian populace. In wartime operations, the military police may supp ...

. The period's best-known battle broke out in Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

the day the armistice was announced. Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

units such as the Sassari Division, the Granatieri di Sardegna, the Piave Division, the Ariete II Division, the Centauro Division, the Piacenza Division and the "Lupi di Toscana" Division (in addition to Carabinieri, infantry and coastal artillery regiments) were deployed around the city and along surrounding roads.

Outnumbered German Fallschirmjäger

The () were the airborne forces branch of the Luftwaffe before and during World War II. They were the first paratroopers to be committed in large-scale airborne operations. They were commanded by Kurt Student, the Luftwaffe's second-in-comman ...

and Panzergrenadier

(), abbreviated as ''PzG'' (WWII) or ''PzGren'' (modern), meaning ''Armoured fighting vehicle, "Armour"-ed fighting vehicle "Grenadier"'', is the German language, German term for the military doctrine of mechanized infantry units in armoured fo ...

e were initially repelled and endured losses, but slowly gained the upper hand, aided by their experience and superior Panzer

{{CatAutoTOC, numerals=no

Words and phrases

Germanic words and phrases

Words and phrases by language

la:Categoria:Verba Theodisca ...

component. The defenders were hampered by a number of facts: Allied support was cancelled at the last minute since the Fallschirmjäger took the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division

The 82nd Airborne Division is an Airborne forces, airborne infantry division (military), division of the United States Army specializing in Paratrooper, parachute assault operations into hostile areasSof, Eric"82nd Airborne Division" ''Spec Ops ...

drop zone

A drop zone (DZ) is a place where parachutists or parachuted supplies land. It can be an area targeted for landing by paratroopers and airborne forces, or a base from which recreational parachutists and skydivers take off in aircraft and land ...

s ( Brigadier General Maxwell D. Taylor

Maxwell Davenport Taylor (26 August 1901 – 19 April 1987) was a senior United States Army Officer (armed forces), officer and diplomat during the Cold War. He served with distinction in World War II, most notably as commander of the 101st Air ...

had crossed enemy lines and gone to Rome to personally supervise the operation); King

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

, Marshal Pietro Badoglio

Pietro Badoglio, 1st Duke of Addis Abeba, 1st Marquess of Sabotino ( , ; 28 September 1871 – 1 November 1956), was an Italian general during both World Wars and the first viceroy of Italian East Africa. With the fall of the Fascist regim ...

and their staff fled to Brindisi

Brindisi ( ; ) is a city in the region of Apulia in southern Italy, the capital of the province of Brindisi, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. Historically, the city has played an essential role in trade and culture due to its strategic position ...

, which left the generals in charge of the city without a coordinated defence plan; also the absence of the Italian Centauro II Division, composed primarily of ex-Blackshirts

The Voluntary Militia for National Security (, MVSN), commonly called the Blackshirts (, CCNN, singular: ) or (singular: ), was originally the paramilitary wing of the National Fascist Party, known as the Squadrismo, and after 1923 an all-vo ...

and not trusted, with its German-made tanks, contributed to the defeat of the Italian forces by the Germans.

By 10 September, the Germans had penetrated downtown Rome and the Granatieri (aided by civilians) made their last stand at Porta San Paolo. At 4 pm, General Giorgio Calvi di Bergolo signed the order of surrender; the Italian divisions were disbanded and their troops taken prisoner. Although some officers participating in the battle later joined the resistance, the clash in Rome was not motivated by anti-German sentiment so much as the desire to control the Italian capital and resist the disarmament of Italian soldiers. Generals Raffaele Cadorna Jr. (commander of Ariete II) and Giuseppe Cordero Lanza di Montezemolo (later executed by the Germans) joined the underground; General Gioacchino Solinas (commander of the Granatieri) instead opted for the pro-German Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

.

Piombino

Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

. On 10 September 1943, during Operation Achse

Operation Achse (), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

Several German divisions had en ...

, a small German flotilla, commanded by Kapitänleutnant

, short: KptLt/in lists: KL, ( or ''lieutenant captain'') is an officer grade of the captains' military hierarchy group () of the modern German . The rank is rated Ranks and insignia of NATO navies' officers, OF-2 in NATO, and equivalent to i ...

Karl-Wolf Albrand, tried to enter the harbour of Piombino but was denied access by the port authorities. General and Fascist official Cesare Maria De Vecchi in command of the Italian 215th Coastal Division ordered the port authorities to allow the German flotilla to enter, against the advice of Commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

Amedeo Capuano, the Naval commander of the harbour. Once they entered and landed, the German forces showed a hostile behaviour, and it became clear that their intent was to occupy the town; the local population asked for a resolved reaction by the Italian forces, threatening an insurrection, but the senior Italian commander, general Fortunato Perni, instead ordered his tanks to open fire on the civilians – an order the tankers refused. Meanwhile, De Vecchi forbade any action against the Germans. This however did not stop the protests; some junior officers, acting on their own initiative and against the orders (Perni and De Vecchi even tried to dismiss them for this), assumed command and started distributing weapons to the population, and civilian volunteers joined the Italian sailors and soldiers in the defense.

A battle broke out at 21:15 on 10 September, between the German landing forces (who aimed to occupy the town centre) and the Italian coastal batteries, tanks of the XIX Tank Battalion "M", and civilian population. Italian tanks sank the German torpedo boat ''TA11''; Italian artillery also sank seven Marinefährprahme, the péniches ''Mainz'' and ''Meise'' (another péniche, ''Karin'', was scuttled at the harbour entrance as a blockship

A blockship is a ship deliberately sunk to prevent a river, channel, or canal from being used as a waterway. It may either be sunk by a navy defending the waterway to prevent the ingress of attacking enemy forces, as in the case of at Portland ...

) and six Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

service boats (''Fl.B.429'', ''Fl.B.538'', ''Fl.C.3046'', ''Fl.C.3099'', ''Fl.C.504'' e ''Fl.C.528''), and heavily damaged the torpedo boat ''TA9'' and the steamers ''Carbet'' and ''Capitano Sauro'' (former Italian ships). ''Sauro'' and ''Carbet'' were scuttled because of the damage they had suffered. The German attack was repelled; by the dawn of 11 September 120 Germans had been killed and about 200–300 captured, 120 of them wounded. Italian casualties had been 4 killed (two sailors, one Guardia di Finanza

The Guardia di Finanza (; G. di F. or GdF; or ) is an Italian militarised law enforcement agency under the Ministry of Economy and Finance (Italy), Ministry of Economy and Finance, instead of the Ministry of Defence (Italy), Ministry of Defence ...

brigadier, and one civilian) and a dozen wounded; four Italian submarine chaser

A submarine chaser or subchaser is a type of small naval vessel that is specifically intended for anti-submarine warfare. They encompass designs that are now largely obsolete, but which played an important role in the wars of the first half of th ...

s (''VAS 208'', ''214'', ''219'' and ''220'') were also sunk during the fighting. Later in the morning, however, De Vecchi ordered the prisoners to be released and had their weapons returned to them. New popular protests broke out, as the Italian units were disbanded and the senior commanders fled from the city; the divisional command surrendered Piombino to the Germans on 12 September, and the city was occupied. Many of the sailors, soldiers and citizens who had fought in the battle of Piombino retreated to the surrounding woods and formed the first partisan formations in the area. For the deeds of its citizens, the town received a gold medal for Military Valour from the President of the Italian Republic

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Italian politics comply with the Constitution. The presid ...

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (; 9 December 1920 – 16 September 2016) was an Italian politician, statesman and banker who was the President of Italy from 1999 to 2006 and the Prime Minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994.

A World War II veteran, C ...

.

Outside Italy

In the days following 8 September 1943 most servicemen, left without orders from higher echelons (due to Wehrmacht units ceasing Italian radio communications), were disarmed and shipped to POW camps in the

In the days following 8 September 1943 most servicemen, left without orders from higher echelons (due to Wehrmacht units ceasing Italian radio communications), were disarmed and shipped to POW camps in the Third Reich

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a totalitarian dictat ...

(often by smaller German outfits). However, some garrisons stationed in occupied Greece, Albania, Yugoslavia and Italy fought the Germans. Admirals Inigo Campioni

Inigo Campioni (14 November 1878 – 24 May 1944) was an Italians, Italian naval officer during most of the first half of the 20th century. He served in four wars, and is best known as an admiral in the Italian Royal Navy (''Regia Marina'') d ...

and Luigi Mascherpa led an attempt to defend Rhodes

Rhodes (; ) is the largest of the Dodecanese islands of Greece and is their historical capital; it is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, ninth largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Administratively, the island forms a separ ...

, Kos

Kos or Cos (; ) is a Greek island, which is part of the Dodecanese island chain in the southeastern Aegean Sea. Kos is the third largest island of the Dodecanese, after Rhodes and Karpathos; it has a population of 37,089 (2021 census), making ...

, Leros

Leros (), also called Lero (from the Italian language), is a Greek island and municipality in the Dodecanese in the southern Aegean Sea. It lies from Athens's port of Piraeus, from which it can be reached by a nine-hour ferry ride or by a 45-min ...

and other Dodecanese

The Dodecanese (, ; , ''Dodekánisa'' , ) are a group of 15 larger and 150 smaller Greek islands in the southeastern Aegean Sea and Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Anatolia, of which 26 are inhabited. This island group generally define ...

islands from their former allies. With reinforcements from SAS, SBS and British Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

troops under the command of Generals Francis Gerrard Russell Brittorous and Robert Tilney, the defenders held on for a month. However, the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

took the islands through air and sea landings by infantry and Fallschirmjäger supported by the Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

. Both Campioni and Mascherpa were captured and executed at Verona

Verona ( ; ; or ) is a city on the Adige, River Adige in Veneto, Italy, with 255,131 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region, and is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and in Northeast Italy, nor ...

for high treason.

On 13 September 1943, the Acqui Division stationed in Cefalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia (), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallonia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th-largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It is also a separate regio ...

chose to defend themselves from a German invasion during ongoing negotiations. After a ten-day battle, the Germans executed 5,155 officers and enlisted men in retaliation. Those killed in the massacre of the Acqui Division included division commander General Antonio Gandin. On 1 March 2001, the President of the Italian Republic

The president of Italy, officially titled President of the Italian Republic (), is the head of state of Italy. In that role, the president represents national unity and guarantees that Italian politics comply with the Constitution. The presid ...

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (; 9 December 1920 – 16 September 2016) was an Italian politician, statesman and banker who was the President of Italy from 1999 to 2006 and the Prime Minister of Italy from 1993 to 1994.

A World War II veteran, C ...

visited Cefalonia, giving a speech underlining how "their conscious choice f the Acqui Divisionwas the first act of the ''Resistenza'', of an Italy free from fascism".

Other Italian forces remained trapped in Yugoslavia following the armistice and some decided to fight alongside the local resistance. Elements of the Taurinense Division, the Venezia Division, the Aosta Division and the Emilia Division were assembled in the Italian Garibaldi Partisan Division, part of the Yugoslav People's Liberation Army

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

. When the unit finally returned to Italy at the end of the war, half its members had been killed or were listed as missing in action.

On 9 September 1943, Bastia

Bastia ( , , , ; ) is a communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Haute-Corse, Corsica, France. It is located in the northeast of the island of Corsica at the base of Cap Corse. It also has the second-highest popu ...

, in Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

, was the setting of a naval battle between Italian torpedo boats and an attacking German flotilla. It was one of the few successful Italian reactions to Operation Achse

Operation Achse (), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

Several German divisions had en ...

, and one of the first acts of resistance by the Italian armed forces against Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

after the armistice of Cassibile

The Armistice of Cassibile ( Italian: ''Armistizio di Cassibile'') was an armistice that was signed on 3 September 1943 by Italy and the Allies, marking the end of hostilities between Italy and the Allies during World War II. It was made public ...

.

Italian military internees

Italian soldiers captured by the Germans numbered around 650,000–700,000 (some 45,000 others were killed in combat, executed, or died during transport), of whom between 40,000 and 50,000 later died in the camps. Most refused cooperation with the Third Reich despite hardship, chiefly to maintain their oath of fidelity to the King. Their former allies designated them ''Italienische Militär-Internierte'' ("Italian military internees") to deny themprisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

status and the rights granted by the Geneva Convention

upright=1.15, The original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are international humanitarian laws consisting of four treaties and three additional protocols that establish international legal standards for humanitarian t ...

. Their actions were eventually recognized as an act of unarmed resistance on a par with the armed confrontation of other Italian servicemen.

After disarmament by the Germans, the Italian soldiers and officers were confronted with the choice to continue fighting as allies of the German army (either in the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic

The Italian Social Republic (, ; RSI; , ), known prior to December 1943 as the National Republican State of Italy (; SNRI), but more popularly known as the Republic of Salò (, ), was a List of World War II puppet states#Germany, German puppe ...

, the German puppet regime in northern Italy led by Mussolini, or in Italian "volunteer" units in the German armed forces) or, otherwise, be sent to detention camps in Germany. Those soldiers and officials who refused to recognize the "republic" led by Mussolini were taken as civilian prisoners too. Only 10 percent agreed to enroll.

The Nazis considered the Italians as traitors and not as prisoners of war. The former Italian soldiers were sent into forced labour

Forced labour, or unfree labour, is any work relation, especially in modern or early modern history, in which people are employed against their will with the threat of destitution, detention, or violence, including death or other forms of ...

in war industries (35.6%), heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

(7.1%), mining (28.5%), construction (5.9%) and agriculture (14.3%). The working conditions were very poor. The Italians were inadequately fed or clothed for the German winter. Many became sick and died. The death rate of the military internees at 6-7% was second only to that of Soviet prisoners of war The following articles deal with Soviet prisoners of war.

* Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–24)

*Soviet prisoners of war in Finland

Soviet prisoners of war in Finland during World War II were captured in two Soviet Un ...

although much lower.

Resistance by Italian partisans

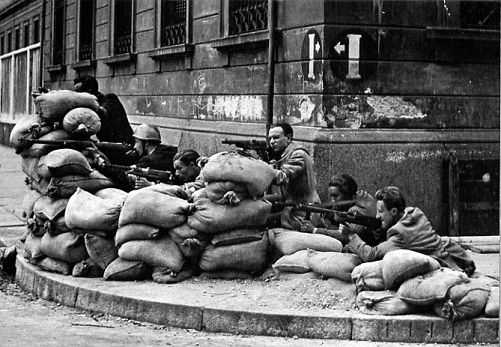

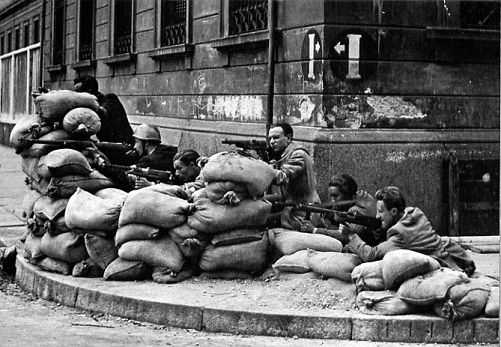

In the first major act of resistance following the German occupation, Italian partisans and local resistance fighters liberated the city ofNaples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

through a chaotic popular rebellion. Naples was the first of the major European cities to rise up against the German occupation, and successfully at that. The people of Naples revolted and held strong against Nazi occupiers in the last days of September 1943. The popular mass uprising and resistance in Naples against the occupying Nazi German forces, known as the Four days of Naples, consisted of four days of continuous open warfare and guerrilla actions by locals against the Nazi Germans. The spontaneous uprising of Neopolitan and Italian Resistance against German occupying forces (despite limited armament, organization, or planning) nevertheless successfully disrupted German plans to deport Neopolitans en masse, destroy the city, and prevent Allied forces from gaining a strategic foothold.

Elsewhere, the nascent movement began as independently operating groups were organized and led by previously outlawed political parties or by former officers of the Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

. Many partisan formations were initially founded by soldiers from disbanded units of the Royal Italian Army

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

that had evaded capture in Operation Achse

Operation Achse (), originally called Operation Alaric (), was the codename for the German operation to forcibly disarm the Italian armed forces after Italy's armistice with the Allies on 3 September 1943.

Several German divisions had en ...

, and were led by junior Army officers who had decided to resist the German occupation; they were subsequently joined and re-organized by Anti-Fascists, and became thus increasingly politicized.

Later the Comitato di Liberazione Nazionale

The National Liberation Committee (, CLN) was a political umbrella organization and the main representative of the Italian resistance movement fighting against the occupying forces of Nazi Germany and the fascist collaborationist forces of the ...

(Committee of National Liberation, or CLN), created by the Italian Communist Party

The Italian Communist Party (, PCI) was a communist and democratic socialist political party in Italy. It was established in Livorno as the Communist Party of Italy (, PCd'I) on 21 January 1921, when it seceded from the Italian Socialist Part ...

, the Italian Socialist Party

The Italian Socialist Party (, PSI) was a Social democracy, social democratic and Democratic socialism, democratic socialist political party in Italy, whose history stretched for longer than a century, making it one of the longest-living parti ...

, the Partito d'Azione (a republican liberal socialist party), Democrazia Cristiana

Christian Democracy (, DC) was a Christian democratic political party in Italy. The DC was founded on 15 December 1943 in the Italian Social Republic (Nazi-occupied Italy) as the nominal successor of the Italian People's Party (1919), Italian ...

and other minor parties, largely took control of the movement in accordance with King Victor Emmanuel III

Victor Emmanuel III (; 11 November 1869 – 28 December 1947) was King of Italy from 29 July 1900 until his abdication on 9 May 1946. A member of the House of Savoy, he also reigned as Emperor of Ethiopia from 1936 to 1941 and King of the Albani ...

's ministers and the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

. The CLN was set up by partisans behind German lines and had the support of most groups in the region.

The main CLN formations included three politically varied groups: the communist '' Brigate Garibaldi'' (Garibaldi Brigades), the ''Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; ) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The movement was cofounded by ...

'' (Justice and Freedom) Brigades related to the Partito d'Azione, and the socialist '' Brigate Matteotti'' ( Matteotti Brigades). Smaller groups included Christian democrats and, outside the CLN, monarchists

Monarchism is the advocacy of the system of monarchy or monarchical rule. A monarchist is an individual who supports this form of government independently of any specific monarch, whereas one who supports a particular monarch is a royalist. C ...

such as the '' Brigate Fiamme Verdi'' (Green Flame Brigades) and '' Fronte Militare Clandestino'' (Clandestine Military Front) headed by Colonel Montezemolo. Another sizeable partisan group, particularly strong in Piedmont (where the Fourth Army had disintegrated in September 1943), were the "autonomous" (''autonomi'') partisans, largely composed of former soldiers with no substantial alignment to any anti-Fascist party; an example was the ''1° Gruppo Divisioni Alpine'' led by Enrico Martini.

Relations among the groups varied. For example, in 1945, the Garibaldi partisans under Yugoslav Partisan

The Yugoslav Partisans,Serbo-Croatian, Macedonian language, Macedonian, and Slovene language, Slovene: , officially the National Liberation Army and Partisan Detachments of Yugoslavia sh-Latn-Cyrl, Narodnooslobodilačka vojska i partizanski odr ...

command attacked and killed several partisans of the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and ''azionista'' Osoppo groups in the province of Udine

The province of Udine (; ; ; ; ) was a province in the autonomous Friuli-Venezia Giulia region of Italy, bordering Austria and Slovenia, with the capital in the city of Udine. Abolished on 30 September 2017, it was reestablished in 2019 as the Re ...

. Tensions between the Catholics and the Communists in the movement led to the foundation of the ''Fiamme Verdi'' as a separate formation.

A further challenge to the 'national unity' embodied in the CLN came from anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that seeks to abolish all institutions that perpetuate authority, coercion, or hierarchy, primarily targeting the state and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state w ...

as well as dissident-communist Resistance formations, such as Turin's ''Stella Rossa'' movement and the ''Movimento Comunista d'Italia

The ''Movimento Comunista d'Italia'' (MCd'I), best-known after its newspaper ''Bandiera Rossa'', was a revolutionary partisan brigade, and the largest single formation of the 1943-44 Italian Resistance in Rome.

History

Growing out of communist und ...

'' (Rome's largest single anti-fascist force under Occupation), which sought a revolutionary outcome to the conflict and were thus unwilling to collaborate with 'bourgeois parties'.

Partisan movement

Rodolfo Graziani

Rodolfo Graziani, 1st Marquis of Neghelli ( , ; 11 August 1882 – 11 January 1955), was an Italian military officer in the Kingdom of Italy's Royal Italian Army, Royal Army, primarily noted for his campaigns in Africa before and during World Wa ...

estimated the partisan strength at around 70,000–80,000 by May 1944. Some 41% in the Garibaldi Brigades and 29% were Actionists of the ''Giustizia e Libertà'' Brigades. One of the strongest units, the 8th Garibaldi Brigade, had 8,050 men (450 without arms) and operated in the Romagna

Romagna () is an Italian historical region that approximately corresponds to the south-eastern portion of present-day Emilia-Romagna, in northern Italy.

Etymology

The name ''Romagna'' originates from the Latin name ''Romania'', which originally ...

area. The CLN mostly operated in the Alpine area, Apennine area and Po Valley

The Po Valley, Po Plain, Plain of the Po, or Padan Plain (, , or ) is a major geographical feature of northern Italy. It extends approximately in an east-west direction, with an area of including its Venetian Plain, Venetic extension not actu ...

of the RSI, and also in the German ''OZAK'' (the area northeast of the north end of the Adriatic Sea

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

) and '' OZAV'' (Trentino and South Tyrol) zones. Its losses amounted to 16,000 killed, wounded or captured between September 1943 and May 1944. On 15 June 1944, the General Staff of the ''Esercito Nazionale Repubblicano

The National Republican Army (; abbreviated ENR), colloquially known as the Army of the North (Italian language, Italian: ''Esercito del Nord'') was the army of the Italian Social Republic (, or RSI) from 1943 to 1945, fighting on the side of N ...

'' estimated that the partisan forces amounted to some 82,000 men, of whom about 25,000 operated in Piedmont

Piedmont ( ; ; ) is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the northwest Italy, Northwest of the country. It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the ...

, 14,200 in Liguria

Liguria (; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is roughly coextensive with ...

, 16,000 in the Julian March, 17,000 in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

and Emilia-Romagna

Emilia-Romagna (, , both , ; or ; ) is an Regions of Italy, administrative region of northern Italy, comprising the historical regions of Emilia (region), Emilia and Romagna. Its capital is Bologna. It has an area of , and a population of 4.4 m ...

, 5,600 in Veneto

Veneto, officially the Region of Veneto, is one of the 20 regions of Italy, located in the Northeast Italy, north-east of the country. It is the fourth most populous region in Italy, with a population of 4,851,851 as of 2025. Venice is t ...

, and 5,000 in Lombardy

The Lombardy Region (; ) is an administrative regions of Italy, region of Italy that covers ; it is located in northern Italy and has a population of about 10 million people, constituting more than one-sixth of Italy's population. Lombardy is ...

. Their ranks were gradually increased by the influx of young men escaping the Italian Social Republic's draft, as well as from deserters from the RSI armed forces.Giuseppe Fioravanzo, ''La Marina dall'8 settembre 1943 alla fine del conflitto'', p. 433. By August 1944, the number of partisans had grown to 100,000, and it escalated to more than 250,000 with the final insurrection in April 1945. The Italian resistance suffered 50,000 fighters killed throughout the conflict.

Partisan unit sizes varied, depending on logistics (such as the ability to arm, clothe and feed members) and the amount of local support. The basic unit was the ''squadra'' (squad), with three or more squads (usually five) forming a ''distaccamento'' (detachment). Three or more detachments made a ''brigata'' (brigade), of which two or more made a ''divisione'' (division). In some places, several divisions formed a ''gruppo divisione'' (divisional group). These divisional groups were responsible for a ''zona d'operazione'' (operational group).

While the largest contingents operated in mountainous districts of the Alps and the Apennine Mountains

The Apennines or Apennine Mountains ( ; or Ἀπέννινον ὄρος; or – a singular with plural meaning; )Latin ''Apenninus'' (Greek or ) has the form of an adjective, which would be segmented ''Apenn-inus'', often used with nouns s ...

, other large formations fought in the Po River

The Po ( , ) is the longest river in Italy. It flows eastward across northern Italy, starting from the Cottian Alps. The river's length is , or if the Maira (river), Maira, a right bank tributary, is included. The headwaters of the Po are forme ...

flatland. In the large towns of northern Italy, such as Piacenza

Piacenza (; ; ) is a city and (municipality) in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Piacenza, eponymous province. As of 2022, Piacenza is the ninth largest city in the region by population, with more ...

, and the surrounding valleys near the Gothic Line

The Gothic Line (; ) was a German and Italian defensive line of the Italian Campaign of World War II. It formed Field Marshal Albert Kesselring's last major line of defence along the summits of the northern part of the Apennine Mountains du ...

. Montechino Castle housed a key partisan headquarters. The '' Gruppi di Azione Patriottica'' (GAP; "Patriotic Action Groups") commanded by the Resistance's youngest officer, Giuseppe "Beppe" Ruffino, carried out acts of sabotage

Sabotage is a deliberate action aimed at weakening a polity, government, effort, or organization through subversion, obstruction, demoralization (warfare), demoralization, destabilization, divide and rule, division, social disruption, disrupti ...

and guerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

, and the ''Squadre di Azione Patriottica'' (SAP; "Patriotic Action Squads") arranged strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

s and propaganda campaigns. As in the French Resistance

The French Resistance ( ) was a collection of groups that fought the German military administration in occupied France during World War II, Nazi occupation and the Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy#France, collaborationist Vic ...

, women were often important members and couriers.

Like their counterparts elsewhere in Europe, Italian partisans seized whatever arms they could find. The first weapons were brought by ex-soldiers fighting German occupiers from the Regio Esercito

The Royal Italian Army () (RE) was the land force of the Kingdom of Italy, established with the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy. During the 19th century Italy started to unify into one country, and in 1861 Manfredo Fanti signed a decree c ...

inventory: Carcano rifles, Beretta M1934 and M1935 pistols, Bodeo M1889 revolvers, SRCM and OTO hand grenades, and Fiat–Revelli Modello 1935, Breda 30

The ''Fucile Mitragliatore Breda modello'' 30 also known as ''Breda 30'' was the standard light machine gun of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. The Breda Modello 30 was issued at the squad level in order to give Italian rifle squads ...

and Breda M37 machine guns. Later, captured K98ks, MG 34

The MG 34 (shortened from German: ''Maschinengewehr 34'', or "machine gun 34") is a German recoil-operated air-cooled general-purpose machine gun, first tested in 1929, introduced in 1934, and issued to units in 1936. It introduced an entirely ...

s, MG 42

The MG 42 (shortened from German: ''Maschinengewehr 42'', or "machine gun 42") is a German recoil-operated air-cooled general-purpose machine gun used extensively by the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS during the second half of World War II. Enter ...

s, the iconic potato-masher grenades, Lugers, and Walther P38

The Walther P38 (originally written Walther P.38) is a 9 mm semi-automatic pistol that was developed by Carl Walther GmbH as the service pistol of the Wehrmacht at the beginning of World War II. It was intended to replace the comparatively comp ...

s were added to partisan kits. Submachine guns (such as the MP 40

The MP 40 () is a submachine gun chambered for the 9×19mm Parabellum cartridge. Developed in Nazi Germany, it saw extensive service in the Axis powers , Axis forces during World War II.

Designed in 1938 by Heinrich Vollmer with inspiration ...

) were initially scarce, and usually reserved for squad leaders.

Automatic weapons became more common as they were captured in combat and as the Social Republic regime soldiers began defecting, bringing their own guns. Beretta MABs began appearing in larger numbers in October 1943, when they were spirited away ''en masse'' from the Beretta

Fabbrica d'Armi Pietro Beretta (; "Pietro Beretta Weapons Factory") is a privately held Italian firearms manufacturing company operating in several countries. Its firearms are used worldwide for various civilian, law enforcement, and military p ...

factory which was producing them for the Wehrmacht. Additional weapons (chiefly of British origin) were airdropped by the Allies: PIAT

The Projector, Infantry, Anti Tank (PIAT) Mk I was a British man-portable anti-tank weapon developed during the Second World War. The PIAT was designed in 1942 in response to the British Army's need for a more effective infantry anti-tank weapo ...

s, Lee–Enfield

The Lee–Enfield is a bolt-action, magazine-fed repeating rifle that served as the main firearm of the military forces of the British Empire and Commonwealth during the first half of the 20th century, and was the standard service rifle of th ...

rifles, Bren light machine gun

The Bren gun (Brno-Enfield) was a series of light machine guns (LMG) made by the United Kingdom in the 1930s and used in various roles until 1992. While best known for its role as the British and Commonwealth forces' primary infantry LMG in Worl ...

s and Sten gun

The STEN (or Sten gun) is a British submachine gun chambered in 9×19mm which was used extensively by British and Commonwealth forces throughout World War II and during the Korean War. The Sten paired a simple design with a low production co ...

s. U.S.-made weapons were provided on a smaller scale from the Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

(OSS): Thompson submachine gun

The Thompson submachine gun (also known as the "Tommy gun", "Chicago typewriter", or "trench broom") is a blowback-operated, selective-fire submachine gun, invented and developed by Brigadier General John T. Thompson, a United States Arm ...

s (both M1928 and M1), M3 submachine gun

The M3 is an American .45 ACP, .45-caliber submachine gun adopted by the U.S. Army on 12 December 1942, as the United States Submachine Gun, Cal. .45, M3.Iannamico, Frank, ''The U.S. M3-3A1 Submachine Gun'', Moose Lake Publishing, , (1999), pp. ...

s, United Defense M42s, and folding-stock M1 carbine

The M1 carbine (formally the United States carbine, caliber .30, M1) is a lightweight semi-automatic carbine chambered in the .30 carbine (7.62×33mm) cartridge that was issued to the U.S. military during World War II, the Korean War, and t ...

s. Other supplies included explosives, clothing, boots, food rations, and money (used to buy weapons or to compensate civilians for confiscations).

Countryside

The worst conditions and fighting took place in mountainous regions. Resources were scarce and living conditions were terrible. Due to limited supplies, the resistance adoptedguerrilla warfare

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include recruited children, use ambushes, sabotage, terrori ...

. This involved groups of 40–50 fighters ambushing and harassing the Nazis and their allies. The size of the brigades was reflective of the resources available to the partisans. Resource limits could not support large groups in one area. Mobility was key to their success. Their terrain knowledge enabled narrow escapes in small groups when nearly surrounded by the Germans. The partisans had no permanent headquarters or bases, making them difficult to destroy.

The resistance fighters themselves relied heavily on the local populace for support and supplies. They would often barter or just ask for food, blankets and medicine. When the partisans took supplies from families, they would often hand out promissory notes

A promissory note, sometimes referred to as a note payable, is a legal instrument (more particularly, a financing instrument and a debt instrument), in which one party (the ''maker'' or ''issuer'') promises in writing to pay a determinate sum of ...

that the peasants could convert after the war for money. The partisans slept in abandoned farms and farmhouses. One account from Paolino 'Andrea' Ranieri (a political commissar at the time) described fighters using donkeys to move equipment at night while during the day the peasants used them in the fields. The Nazis tried to split the populace from the resistance by adopting a reprisal policy of killing 10 Italians for every German killed by the Partisans. Those executed would come from the village near where an attack took place and sometimes from captive partisan fighters.

The German punishments backfired and instead strengthened the relationship. Because most resistance fighters were peasants, local populations felt a need to provide for their own. One of the larger engagements was the battle for Monte Battaglia (lit. "Battle Mountain"), a mountaintop that was a part of the Gothic Line. On 26 September 1944, a joint force of 250 Partisans and three companies of U.S. soldiers from the 88th Infantry Division attacked the hill occupied by elements of the German 290th Grenadier Regiment. The Germans were caught completely by surprise. The attackers captured the hill and held it for five days against reinforced German units, securing a path for the Allied advance.

Urban areas

Resistance activities were different in the cities. Some Italians ignored the struggle, while others organized, such as the Patriotic Action Squads and issued propaganda. Groups such as the Patriotic Action Groups carried out military actions. A more expansive support network was devised than in the countryside. Networks ofsafe house

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is a dwelling place or building whose unassuming appearance makes it an inconspicuous location where one can hide out, take shelter, or conduct clandestine activities.

Historical usage

It may also refer to ...

s were established to hide weapons and wounded fighters. Only sympathizers were involved, because compulsion was thought to encourage betrayal. People largely supported the resistance because of economic hardships, especially inflation. Pasta

Pasta (, ; ) is a type of food typically made from an Leavening agent, unleavened dough of wheat flour mixed with water or Eggs as food, eggs, and formed into sheets or other shapes, then cooked by boiling or baking. Pasta was originally on ...

prices tripled and bread prices had quintupled since 1938; hunger unified the underground and general population.

Female partisans

Women played a large role. After the war, about 35,000 Italian women were recognised as female ''partigiane combattenti'' (partisan combatants) and 20,000 as ''patriote'' (patriots); they broke into these groups based on their activities. The majority were between 20 and 29. They were generally kept separate from male partisans. Few were attached to brigades and were even rarer in mountain brigades. Female countryside volunteers were generally rejected. Women still served in large numbers and had significant influence.

The groups were formed collaboratively by women from diverse political backgrounds. Prominent participants included communists Giovanna Barcellona, Lina Fibbi, Marisa Diena, and Caterina Picolato; socialists Laura Conti and Lina Merlin; actionists Elena Dreher and

Women played a large role. After the war, about 35,000 Italian women were recognised as female ''partigiane combattenti'' (partisan combatants) and 20,000 as ''patriote'' (patriots); they broke into these groups based on their activities. The majority were between 20 and 29. They were generally kept separate from male partisans. Few were attached to brigades and were even rarer in mountain brigades. Female countryside volunteers were generally rejected. Women still served in large numbers and had significant influence.

The groups were formed collaboratively by women from diverse political backgrounds. Prominent participants included communists Giovanna Barcellona, Lina Fibbi, Marisa Diena, and Caterina Picolato; socialists Laura Conti and Lina Merlin; actionists Elena Dreher and Ada Gobetti

Ada Gobetti (later Marchesini; ; 14 July 1902 – 14 March 1968) was an Italian teacher, journalist and anti-fascist leader.

Biography

With her husband Piero Gobetti she contributed to several antifascist magazines, including '' La Rivoluzio ...

; as well as women associated with the Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; ) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The movement was cofounded by ...

(Justice and Freedom) movement. Republican and Catholic women, along with those without prior political or ideological commitments, also joined. These groups predominantly operated in the northern midlands of Italy. Scholars attribute this geographic spread to the influence of local women's clothing, which fostered individual initiative and civic awareness.

Initially, the women's groups aimed to support resistance efforts in auxiliary roles. However, they quickly assumed leadership responsibilities in areas such as information dissemination, propaganda, issuing orders, and handling ammunition. Some women even directly engaged in armed resistance as "gappistas". Ada Gobetti

Ada Gobetti (later Marchesini; ; 14 July 1902 – 14 March 1968) was an Italian teacher, journalist and anti-fascist leader.

Biography

With her husband Piero Gobetti she contributed to several antifascist magazines, including '' La Rivoluzio ...

was among the first to criticize the use of the term "assistance" in the group's name. In 1944, the organization's objectives were reformulated to prioritize activities that broadly promoted women's emancipation.

1944 uprising

During the summer and early fall of 1944, with Allied forces nearby, partisans attacked behind German lines, led by CLNAI. This rebellion led to provisional partisan governments throughout the mountainous regions.Ossola

The Ossola (; ), also Valle Ossola or Val d'Ossola (; ), is an area of Northwest Italy situated to the north of Lago Maggiore. It lies within the Province of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola. Its principal river is the Toce, and its most important town Do ...

was the most important of these, receiving recognition from Switzerland and Allied consulates there. An intelligence officer told Field Marshal Albert Kesselring

Albert Kesselring (30 November 1885 – 16 July 1960) was a German military officer and convicted war crime, war criminal who served in the ''Luftwaffe'' during World War II. In a career which spanned both world wars, Kesselring reached the ra ...

, Germany's commander of occupation forces in Italy, that he estimated German casualties fighting partisans in the summer of 1944 amounted to 30,000 to 35,000, including 5,000 confirmed killed. Kesselring considered the number to be exaggerated, and offered his own figure of 20,000: 5,000 killed, between 7,000 and 8,000 missing / "kidnapped" (including deserters), and a similar number seriously wounded. Both sources agreed that partisan losses were less. By the end of the year, German reinforcements and Mussolini's remaining forces crushed the uprising.

In their attempts to suppress the resistance, German and Italian Fascist forces (especially the SS, Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

, and paramilitary militias such as Xª MAS and Black Brigades) committed war crimes, including summary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

s and systematic reprisals against the civilian population. Resistance captives and suspects were often tortured and raped. Some of the most notorious mass atrocities included the Ardeatine massacre

The Ardeatine massacre, or Fosse Ardeatine massacre (), was a mass killing of 335 civilians and political prisoners carried out in Rome on 24 March 1944 by German occupation troops during the Second World War as a reprisal for the Via Rasell ...

(335 Jewish civilians and political prisoners executed without a trial in a reprisal operation after a resistance bomb attack in Rome), the Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre (about 560 random villagers brutally killed in an anti-partisan operation in the central mountains), the Marzabotto massacre (about 770 civilians killed in similar circumstances), the Ossola

The Ossola (; ), also Valle Ossola or Val d'Ossola (; ), is an area of Northwest Italy situated to the north of Lago Maggiore. It lies within the Province of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola. Its principal river is the Toce, and its most important town Do ...

massacre (24 partisans murdered during their retreat from Croveo to Switzerland) and the Salussola massacre (20 partisans murdered after being tortured, as a reprisal). In all, an estimated 15,000 Italian civilians were deliberately killed, including many women and children.

Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, early 1944

File:Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-477-2106-08, Bei Mailand, Soldat Zivilisten kontrollierend.jpg, German soldier examining the papers of an Italian civilian outside of Milan