iron furnace on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A blast furnace is a type of

Blast furnaces operate on the principle of

Blast furnaces operate on the principle of

Cast iron has been found in

Cast iron has been found in

metallurgical furnace

A metallurgical furnace, often simply referred to as a furnace when the context is known, is an industrial furnace used to heat, melt, or otherwise process metals. Furnaces have been a central piece of equipment throughout the history of metallurg ...

used for smelting

Smelting is a process of applying heat and a chemical reducing agent to an ore to extract a desired base metal product. It is a form of extractive metallurgy that is used to obtain many metals such as iron-making, iron, copper extraction, copper ...

to produce industrial metals, generally pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

, but also others such as lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

or copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

. ''Blast'' refers to the combustion air being supplied above atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as air pressure or barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1,013. ...

.

In a blast furnace, fuel ( coke), ores

Ore is natural Rock (geology), rock or sediment that contains one or more valuable minerals, typically including metals, concentrated above background levels, and that is economically viable to mine and process. The grade of ore refers to the ...

, and flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications in physics. For transport phe ...

(limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

) are continuously supplied through the top of the furnace, while a hot blast of (sometimes oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

enriched) air

An atmosphere () is a layer of gases that envelop an astronomical object, held in place by the gravity of the object. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A stellar atmosph ...

is blown into the lower section of the furnace through a series of pipes called tuyeres

A tuyere or tuyère (; ) is a tube, nozzle or pipe allowing the blowing of air into a furnace or hearth.W. K. V. Gale, The iron and Steel industry: a dictionary of terms (David and Charles, Newton Abbot 1972), 216–217.

Air or oxygen is i ...

, so that the chemical reactions

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an energy change as new products ...

take place throughout the furnace as the material falls downward. The end products are usually molten metal and slag

The general term slag may be a by-product or co-product of smelting (pyrometallurgical) ores and recycled metals depending on the type of material being produced. Slag is mainly a mixture of metal oxides and silicon dioxide. Broadly, it can be c ...

phases tapped from the bottom, and flue gases exiting from the top. The downward flow of the ore along with the flux in contact with an upflow of hot, carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

-rich combustion gases is a countercurrent exchange

Countercurrent exchange is a mechanism between two flowing bodies flowing in opposite directions to each other, in which there is a transfer of some property, usually heat or some chemical. The flowing bodies can be liquids, gases, or even solid ...

and chemical reaction process.

In contrast, air furnaces (such as reverberatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

s) are naturally aspirated, usually by the convection

Convection is single or Multiphase flow, multiphase fluid flow that occurs Spontaneous process, spontaneously through the combined effects of material property heterogeneity and body forces on a fluid, most commonly density and gravity (see buoy ...

of hot gases in a chimney flue

A chimney is an architectural ventilation structure made of masonry, clay or metal that isolates hot toxic exhaust gases or smoke produced by a boiler, stove, furnace, incinerator, or fireplace from human living areas. Chimneys are typically ...

. According to this broad definition, bloomeries for iron, blowing house

A blowing house or blowing mill was a building used for smelting tin in Cornwall and on Dartmoor in Devon, in South West England. Blowing houses contained a furnace and a pair of bellows that were powered by an adjacent water wheel, and they w ...

s for tin

Tin is a chemical element; it has symbol Sn () and atomic number 50. A silvery-colored metal, tin is soft enough to be cut with little force, and a bar of tin can be bent by hand with little effort. When bent, a bar of tin makes a sound, the ...

, and smelt mill

Smeltmills were water-powered mills used to smelt lead or other metals.

The older method of smelting lead on wind-blown bole hills began to be superseded by artificially-blown smelters. The first such furnace was built by Burchard Kranich at ...

s for lead

Lead () is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol Pb (from Latin ) and atomic number 82. It is a Heavy metal (elements), heavy metal that is density, denser than most common materials. Lead is Mohs scale, soft and Ductility, malleabl ...

would be classified as blast furnaces. However, the term has usually been limited to those used for smelting iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty red. The iron is usually found in the f ...

to produce pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

, an intermediate material used in the production of commercial iron and steel

Steel is an alloy of iron and carbon that demonstrates improved mechanical properties compared to the pure form of iron. Due to steel's high Young's modulus, elastic modulus, Yield (engineering), yield strength, Fracture, fracture strength a ...

, and the shaft furnaces used in combination with sinter plant

Sinter plants agglomerate iron ore

Iron ores are rocks and minerals from which metallic iron can be economically extracted. The ores are usually rich in iron oxides and vary in color from dark grey, bright yellow, or deep purple to rusty r ...

s in base metals

A base metal is a common and inexpensive metal, as opposed to a precious metal such as gold or silver. In numismatics, coins often derived their value from the precious metal content; however, base metals have also been used in coins in the past ...

smelting.

Blast furnaces are estimated to have been responsible for over 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities intensify the greenhouse effect. This contributes to climate change. Carbon dioxide (), from burning fossil fuels such as coal, petroleum, oil, and natural gas, is the main cause of climate chan ...

between 1900 and 2015, and are difficult to decarbonize.

Process engineering and chemistry

Blast furnaces operate on the principle of

Blast furnaces operate on the principle of chemical reduction

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

whereby carbon monoxide converts iron oxides to elemental iron.

Blast furnaces differ from bloomeries and reverberatory furnace

A reverberatory furnace is a metallurgy, metallurgical or process Metallurgical furnace, furnace that isolates the material being processed from contact with the fuel, but not from contact with combustion gases. The term ''reverberation'' is use ...

s in that in a blast furnace, flue gas is in direct contact with the ore and iron, allowing carbon monoxide to diffuse into the ore and reduce the iron oxide. The blast furnace operates as a countercurrent exchange

Countercurrent exchange is a mechanism between two flowing bodies flowing in opposite directions to each other, in which there is a transfer of some property, usually heat or some chemical. The flowing bodies can be liquids, gases, or even solid ...

process whereas a bloomery does not. Another difference is that bloomeries operate as a batch process whereas blast furnaces operate continuously for long periods. Continuous operation is also preferred because blast furnaces are difficult to start and stop. Also, the carbon in pig iron lowers the melting point below that of steel or pure iron; in contrast, iron does not melt in a bloomery.

Silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

has to be removed from the pig iron. It reacts with calcium oxide

Calcium oxide (formula: Ca O), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term '' lime'' connotes calcium-containing ...

(burned limestone) and forms silicates, which float to the surface of the molten pig iron as slag. Historically, iron was produced with charcoal to prevent sulfur contamination.

In a blast furnace, a downward-moving column of ore, flux, coke (or charcoal) and their reaction products must be sufficiently porous for the flue gas to pass through, upwards. To ensure this permeability the particle size of the coke or charcoal is of great relevance. Therefore, the coke must be strong enough so it will not be crushed by the weight of the material above it. Besides the physical strength of its particles, the coke must also be low in sulfur, phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

, and ash.

The main chemical reaction producing the molten iron is:

:Fe2O3 + 3CO → 2Fe + 3CO2

This reaction might be divided into multiple steps, with the first being that preheated air blown into the furnace reacts with the carbon in the form of coke to produce carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

and heat:

:2 C(s) + O2(g) → 2 CO(g)

Hot carbon monoxide is the reducing agent

In chemistry, a reducing agent (also known as a reductant, reducer, or electron donor) is a chemical species that "donates" an electron to an (called the , , , or ).

Examples of substances that are common reducing agents include hydrogen, carbon ...

for the iron ore and reacts with the iron oxide

An iron oxide is a chemical compound composed of iron and oxygen. Several iron oxides are recognized. Often they are non-stoichiometric. Ferric oxyhydroxides are a related class of compounds, perhaps the best known of which is rust.

Iron ...

to produce molten iron and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

. Depending on the temperature in the different parts of the furnace (warmest at the bottom) the iron is reduced in several steps. At the top, where the temperature usually is in the range between 200 °C and 700 °C, the iron oxide is partially reduced to iron(II,III) oxide, Fe3O4.

:3 Fe2O3(s) + CO(g) → 2 Fe3O4(s) + CO2(g)

The temperatures 850 °C, further down in the furnace, the iron(II,III) is reduced further to iron(II) oxide:

:Fe3O4(s) + CO(g) → 3 FeO(s) + CO2(g)

Hot carbon dioxide, unreacted carbon monoxide, and nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

from the air pass up through the furnace as fresh feed material travels down into the reaction zone. As the material travels downward, the counter-current gases both preheat the feed charge and decompose the limestone to calcium oxide

Calcium oxide (formula: Ca O), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term '' lime'' connotes calcium-containing ...

and carbon dioxide:

:CaCO3(s) → CaO(s) + CO2(g)

The calcium oxide formed by decomposition reacts with various acidic impurities in the iron (notably silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , commonly found in nature as quartz. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is one of the most complex and abundant f ...

), to form a fayalitic slag which is essentially calcium silicate

Calcium silicate can refer to several silicates of calcium including:

*CaO·SiO2, wollastonite (CaSiO3)

*2CaO·SiO2, larnite (Ca2SiO4)

*3CaO·SiO2, alite or (Ca3SiO5)

*3CaO·2SiO2, (Ca3Si2O7).

This article focuses on Ca2SiO4, also known as calci ...

, :

:SiO2 + CaO → CaSiO3

As the iron(II) oxide moves down to the area with higher temperatures, ranging up to 1200 °C degrees, it is reduced further to iron metal:

:FeO(s) + CO(g) → Fe(s) + CO2(g)

The carbon dioxide formed in this process is re-reduced to carbon monoxide by the coke:

:C(s) + CO2(g) → 2 CO(g)

The temperature-dependent equilibrium controlling the gas atmosphere in the furnace is called the Boudouard reaction

The Boudouard reaction, named after Octave Leopold Boudouard, is the redox reaction of a chemical equilibrium mixture of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide at a given temperature. It is the disproportionation of carbon monoxide into carbon dioxide ...

:

::2CO CO2 + C

The pig iron

Pig iron, also known as crude iron, is an intermediate good used by the iron industry in the production of steel. It is developed by smelting iron ore in a blast furnace. Pig iron has a high carbon content, typically 3.8–4.7%, along with si ...

produced by the blast furnace has a relatively high carbon content of around 4–5% and usually contains too much sulphur, making it very brittle, and of limited immediate commercial use. Some pig iron is used to make cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

. The majority of pig iron produced by blast furnaces undergoes further processing to reduce the carbon and sulphur content and produce various grades of steel used for construction materials, automobiles, ships and machinery. Desulphurisation usually takes place during the transport of the liquid steel to the steelworks. This is done by adding ''calcium oxide'', which reacts with the iron sulfide

Iron sulfide or iron sulphide can refer to range of chemical compounds composed of iron and sulfur.

Minerals

By increasing order of stability:

* Iron(II) sulfide, FeS

* Greigite, Fe3S4 (cubic)

* Pyrrhotite, Fe1−xS (where x = 0 to 0.2) (monocli ...

contained in the pig iron to form calcium sulfide

Calcium sulfide is the chemical compound with the formula Ca S. This white material crystallizes in cubes like rock salt. CaS has been studied as a component in a process that would recycle gypsum, a product of flue-gas desulfurization. Like ...

(called ''lime desulfurization''). In a further process step, the so-called basic oxygen steelmaking

Basic oxygen steelmaking (BOS, BOP, BOF, or OSM), also known as Linz-Donawitz steelmaking or the oxygen converter process,Brock and Elzinga, p. 50. is a method of primary steelmaking in which carbon-rich molten pig iron is made into steel. Blowin ...

, the carbon is oxidized by blowing oxygen onto the liquid pig iron to form ''crude steel''.

History

Cast iron has been found in

Cast iron has been found in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

dating to the 5th century BC, but the earliest extant blast furnaces in China date to the 1st century AD and in the West from the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

. They spread from the region around Namur

Namur (; ; ) is a city and municipality in Wallonia, Belgium. It is the capital both of the province of Namur and of Wallonia, hosting the Parliament of Wallonia, the Government of Wallonia and its administration.

Namur stands at the confl ...

in Wallonia

Wallonia ( ; ; or ), officially the Walloon Region ( ; ), is one of the three communities, regions and language areas of Belgium, regions of Belgium—along with Flemish Region, Flanders and Brussels. Covering the southern portion of the c ...

(Belgium) in the late 15th century, being introduced to England in 1491. The fuel used in these was invariably charcoal. The successful substitution of coke for charcoal is widely attributed to British inventor Abraham Darby Abraham Darby may refer to:

People

*Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) the first of several men of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution. He developed a new method of producing pig iron with ...

in 1709. The efficiency of the process was further enhanced by the practice of preheating the combustion air (hot blast

Hot blast is the preheated air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. This technology, which considerably reduces the fuel consumed, was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. Hot b ...

), patented by British inventor James Beaumont Neilson

James Beaumont Neilson (22 June 1792 – 18 January 1865) was a British inventor whose hot-blast process greatly increased the efficiency of smelting iron.

Life

He was the son of the engineer Walter Neilson, a millwright and later engine ...

in 1828.

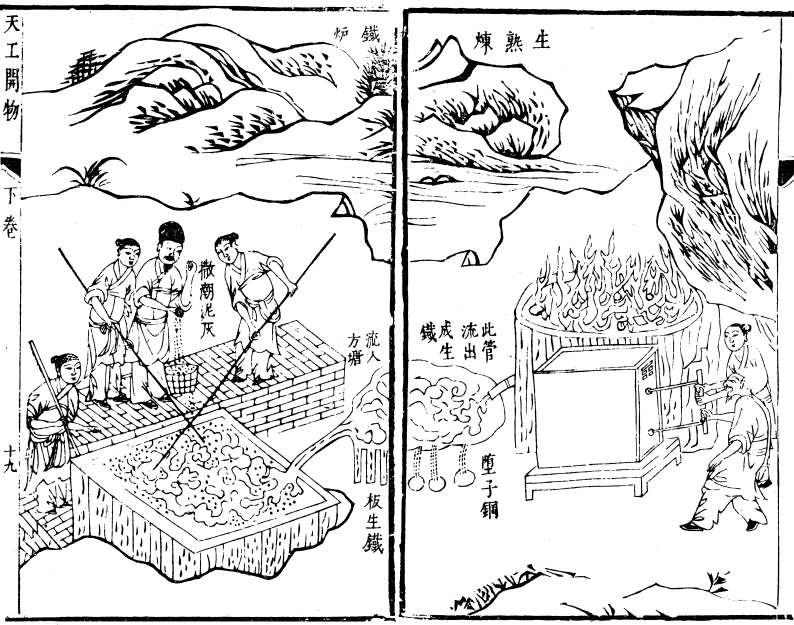

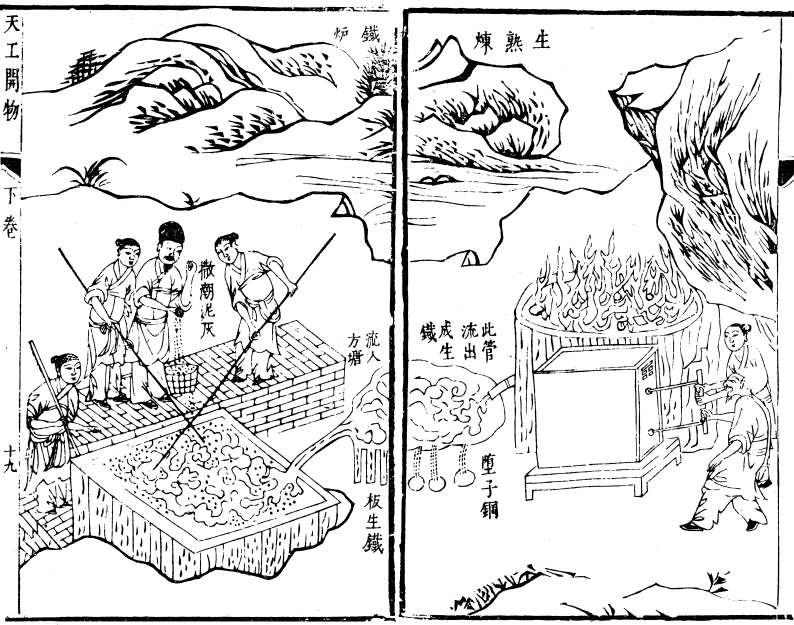

China

Archaeological evidence shows that iron-smelting techniques and bloomeries were brought to China by nomadic peoples around 800 BC. Wrought iron artifacts were originally only found in the northwest, but by the 6th century BC, luxury items such as wrought iron swords and knives were widespread in China. Bloomery iron co-existed with blast furnaces and cast iron, which were invented shortly after wrought iron technology entered China, for quite some time. Cast iron pieces have been found alongside wrought iron inShanxi Province

Shanxi; formerly romanised as Shansi is a province in North China. Its capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-level cities are Changzhi and Datong. Its one-character abbreviation is ( ...

dating to the 9th-8th centuries BC, however it is uncertain if these cast iron pieces were accidental byproducts of the iron smelting process. Adze

An adze () or adz is an ancient and versatile cutting tool similar to an axe but with the cutting edge perpendicular to the handle rather than parallel. Adzes have been used since the Stone Age. They are used for smoothing or carving wood in ha ...

s made using cast iron with a decarburised layer of steel have been found in Luoyang

Luoyang ( zh, s=洛阳, t=洛陽, p=Luòyáng) is a city located in the confluence area of the Luo River and the Yellow River in the west of Henan province, China. Governed as a prefecture-level city, it borders the provincial capital of Zheng ...

dating to the 5th century BC. Cast iron farming tools that had undergone an annealing process to decrease brittleness were found in burials and smelting cites dating to the 4th century BC. Bloomery iron disappeared in China after the 3rd century AD with the exception of Xinjiang, where bloomery iron objects could be found as late as the 9th century AD. In China, blast furnaces produced cast iron, which was then either converted into finished implements in a cupola furnace, or turned into wrought iron in a fining hearth.

Although cast iron

Cast iron is a class of iron–carbon alloys with a carbon content of more than 2% and silicon content around 1–3%. Its usefulness derives from its relatively low melting temperature. The alloying elements determine the form in which its car ...

farm tools and weapons were widespread in China by the 5th century BC, employing workforces of over 200 men in iron smelters from the 3rd century onward, the earliest blast furnaces constructed were attributed to the Han dynasty

The Han dynasty was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC9 AD, 25–220 AD) established by Liu Bang and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by the short-lived Qin dynasty (221–206 BC ...

in the 1st century AD.Ebrey, p. 30. These early furnaces had clay walls and used phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

-containing minerals as a flux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications in physics. For transport phe ...

. Chinese blast furnaces ranged from around two to ten meters in height, depending on the region. The largest ones were found in modern Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

and Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

, while the 'dwarf" blast furnaces were found in Dabieshan. In construction, they are both around the same level of technological sophistication.

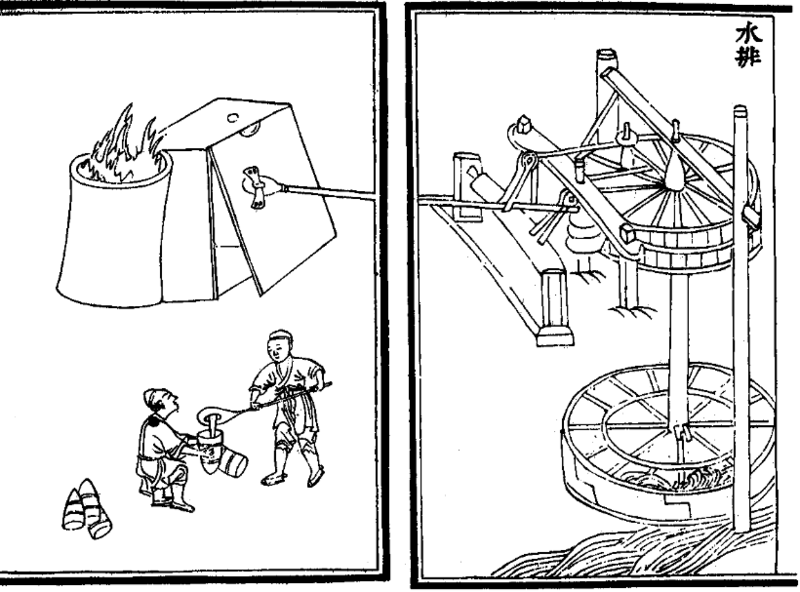

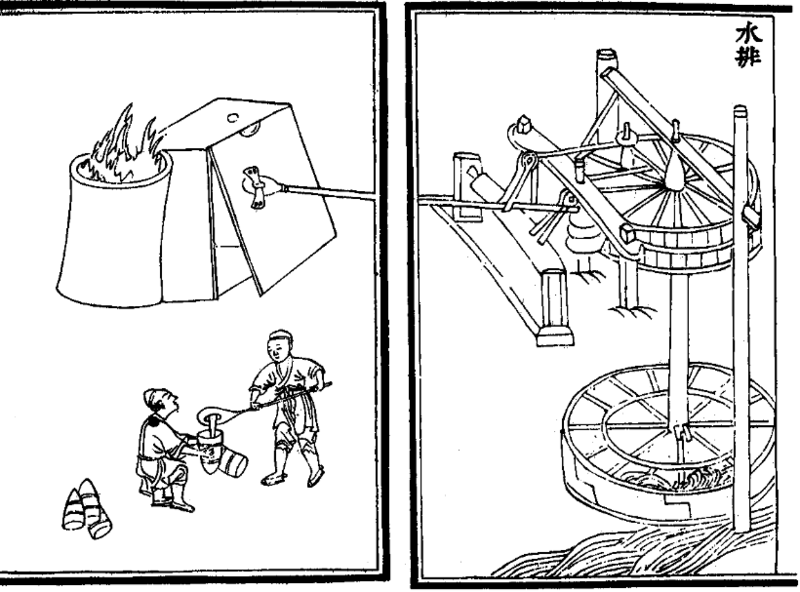

The effectiveness of the Chinese human and horse powered blast furnaces was enhanced during this period by the engineer Du Shi

Du Shi (, d. 38'' Book of Later Han'', vol. 31Crespigny, 183.) was a Chinese hydrologist, inventor, mechanical engineer, metallurgist, and politician of the Eastern Han dynasty. Du Shi is credited with being the first to apply hydraulic power ...

(c. AD 31), who applied the power of waterwheel

A water wheel is a machine for converting the kinetic energy of flowing or falling water into useful forms of power, often in a watermill. A water wheel consists of a large wheel (usually constructed from wood or metal), with numerous blade ...

s to piston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder (engine), cylinder a ...

-bellows

A bellows or pair of bellows is a device constructed to furnish a strong blast of air. The simplest type consists of a flexible bag comprising a pair of rigid boards with handles joined by flexible leather sides enclosing an approximately airtig ...

in forging cast iron. Early water-driven reciprocators for operating blast furnaces were built according to the structure of horse powered reciprocators that already existed. That is, the circular motion of the wheel, be it horse driven or water driven, was transferred by the combination of a belt drive

A belt is a loop of flexible material used to link two or more rotating shafts mechanically, most often parallel. Belts may be used as a source of motion, to transmit power efficiently or to track relative movement. Belts are looped over pull ...

, a crank-and-connecting-rod, other connecting rods

A connecting rod, also called a 'con rod', is the part of a piston engine which connects the piston to the crankshaft. Together with the crank, the connecting rod converts the reciprocating motion of the piston into the rotation of the crankshaf ...

, and various shafts, into the reciprocal motion necessary to operate push bellows.. Donald Wagner suggests that early blast furnace and cast iron production evolved from furnaces used to melt bronze

Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12–12.5% tin and often with the addition of other metals (including aluminium, manganese, nickel, or zinc) and sometimes non-metals (such as phosphorus) or metalloid ...

. Certainly, though, iron was essential to military success by the time the State of Qin

Qin (, , or ''Ch'in'') was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty. It is traditionally dated to 897 BC. The state of Qin originated from a reconquest of western lands that had previously been lost to the Xirong. Its location at ...

had unified China (221 BC). Usage of the blast and cupola furnace remained widespread during the Song

A song is a musical composition performed by the human voice. The voice often carries the melody (a series of distinct and fixed pitches) using patterns of sound and silence. Songs have a structure, such as the common ABA form, and are usu ...

and Tang dynasties. By the 11th century, the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

Chinese iron industry made a switch of resources from charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

to coke in casting iron and steel, sparing thousands of acres of woodland from felling. This may have happened as early as the 4th century AD.

The primary advantage of the early blast furnace was in large scale production and making iron implements more readily available to peasants. Cast iron is more brittle than wrought iron or steel, which required additional fining and then cementation or co-fusion to produce, but for menial activities such as farming it sufficed. By using the blast furnace, it was possible to produce larger quantities of tools such as ploughshares more efficiently than the bloomery. In areas where quality was important, such as warfare, wrought iron and steel were preferred. Nearly all Han period weapons are made of wrought iron or steel, with the exception of axe-heads, of which many are made of cast iron.

Blast furnaces were also later used to produce gunpowder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, charcoal (which is mostly carbon), and potassium nitrate, potassium ni ...

weapons such as cast iron bomb shells and cast iron cannon

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during th ...

s during the Song dynasty

The Song dynasty ( ) was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 960 to 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song, who usurped the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty and went on to conquer the rest of the Fiv ...

.

Medieval Europe

The simplestforge

A forge is a type of hearth used for heating metals, or the workplace (smithy) where such a hearth is located. The forge is used by the smith to heat a piece of metal to a temperature at which it becomes easier to shape by forging, or to the ...

, known as the Corsican, was used prior to the advent of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

. Examples of improved bloomeries are the Stuckofen, sometimes called wolf-furnace, which remained until the beginning of the 19th century. Instead of using natural draught, air was pumped in by a ''trompe

A trompe is a water-powered air compressor, commonly used before the advent of the electric-powered compressor. A trompe is somewhat like an airlift pump working in reverse.

Trompes were used to provide compressed air for bloomery furnaces ...

'', resulting in better quality iron and an increased capacity. This pumping of air in with bellows is known as ''cold blast'', and it increases the fuel efficiency

Fuel efficiency (or fuel economy) is a form of thermal efficiency, meaning the ratio of effort to result of a process that converts chemical energy, chemical potential energy contained in a carrier (fuel) into kinetic energy or Mechanical work, w ...

of the bloomery and improves yield. They can also be built bigger than natural draught bloomeries.

Oldest European blast furnaces

The oldest known blast furnaces in the West were built inDurstel

Durstel (; ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Bas-Rhin Departments of France, department in Grand Est in north-eastern France.

See also

* Communes of the Bas-Rhin department

References

Communes of Bas-Rhin

{{BasRhin-geo-s ...

in Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

, the Märkische Sauerland

The Sauerland () is a rural, hilly area spreading across most of the south-eastern part of the States of Germany, German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, in parts heavily forested and, apart from the major valleys, sparsely inhabited.

...

in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

, and at Lapphyttan

Lapphyttan or Lapphyttejarn in Norberg Municipality, Sweden, may be regarded as the type site for the Medieval Blast Furnace. Its date is probably between 1150 and 1350. It produced cast iron, which was then fined to make ferritic wrought iron ...

in Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

, where the complex was active between 1205 and 1300. At Noraskog in the Swedish parish of Järnboås, traces of even earlier blast furnaces have been found, possibly from around 1100. These early blast furnaces, like the Chinese

Chinese may refer to:

* Something related to China

* Chinese people, people identified with China, through nationality, citizenship, and/or ethnicity

**Han Chinese, East Asian ethnic group native to China.

**'' Zhonghua minzu'', the supra-ethnic ...

examples, were very inefficient compared to those used today. The iron from the Lapphyttan complex was used to produce balls of wrought iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

known as osmonds, and these were traded internationally – a possible reference occurs in a treaty with Novgorod

Veliky Novgorod ( ; , ; ), also known simply as Novgorod (), is the largest city and administrative centre of Novgorod Oblast, Russia. It is one of the oldest cities in Russia, being first mentioned in the 9th century. The city lies along the V ...

from 1203 and several certain references in accounts of English customs from the 1250s and 1320s. Other furnaces of the 13th to 15th centuries have been identified in Westphalia

Westphalia (; ; ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the region is almost identical with the h ...

.

The technology required for blast furnaces may have either been transferred from China, or may have been an indigenous innovation. Al-Qazvini Qazwini with two possible derivations:

* Qazwini (Persian: قزويني ''qazwīni''), the name derived from "Qazvin" (versions of the topographical surname: Qazvini, Qazwini, Qazvini, al-Quazvini), formerly the Safavid dynastic capital (1555-1598) ...

in the 13th century and other travellers subsequently noted an iron industry in the Alburz Mountains to the south of the Caspian Sea

The Caspian Sea is the world's largest inland body of water, described as the List of lakes by area, world's largest lake and usually referred to as a full-fledged sea. An endorheic basin, it lies between Europe and Asia: east of the Caucasus, ...

. This is close to the silk route

The Silk Road was a network of Asian trade routes active from the second century BCE until the mid-15th century. Spanning over , it played a central role in facilitating economic, cultural, political, and religious interactions between the ...

, so that the use of technology derived from China is conceivable. Much later descriptions record blast furnaces about three metres high. As the Varangian

The Varangians ( ; ; ; , or )Varangian

," Online Etymology Dictionary were

'Henry "Stamped Out Industrial Revolution"'

, ''

Due to the increased demand for iron for casting cannons, the blast furnace came into widespread use in France in the mid 15th century.

The direct ancestor of those used in France and England was in the

Due to the increased demand for iron for casting cannons, the blast furnace came into widespread use in France in the mid 15th century.

The direct ancestor of those used in France and England was in the

Stone wool or

Stone wool or

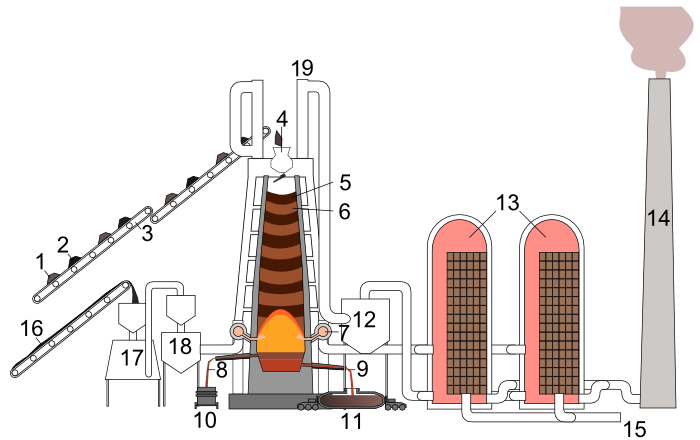

Modern furnaces are equipped with an array of supporting facilities to increase efficiency, such as ore storage yards where barges are unloaded. The raw materials are transferred to the stockhouse complex by ore bridges, or rail hoppers and ore transfer cars. Rail-mounted scale cars or computer controlled weight hoppers weigh out the various raw materials to yield the desired hot metal and slag chemistry. The raw materials are brought to the top of the blast furnace via a

Modern furnaces are equipped with an array of supporting facilities to increase efficiency, such as ore storage yards where barges are unloaded. The raw materials are transferred to the stockhouse complex by ore bridges, or rail hoppers and ore transfer cars. Rail-mounted scale cars or computer controlled weight hoppers weigh out the various raw materials to yield the desired hot metal and slag chemistry. The raw materials are brought to the top of the blast furnace via a

How a Blast Furnace Works

steel.org. There are different ways in which the raw materials are charged into the blast furnace. Some blast furnaces use a "double bell" system where two "bells" are used to control the entry of raw material into the blast furnace. The purpose of the two bells is to minimize the loss of hot gases in the blast furnace. First, the raw materials are emptied into the upper or small bell which then opens to empty the charge into the large bell. The small bell then closes, to seal the blast furnace, while the large bell rotates to provide specific distribution of materials before dispensing the charge into the blast furnace. A more recent design is to use a "bell-less" system. These systems use multiple hoppers to contain each raw material, which is then discharged into the blast furnace through valves. These valves are more accurate at controlling how much of each constituent is added, as compared to the skip or conveyor system, thereby increasing the efficiency of the furnace. Some of these bell-less systems also implement a discharge chute in the throat of the furnace (as with the Paul Wurth top) in order to precisely control where the charge is placed. The iron making blast furnace itself is built in the form of a tall structure, lined with

File:Alto horno antiguo Sestao.jpg, Abandoned blast furnace in

American Iron and Steel InstituteBlast Furnace animation Extensive picture gallery about all methods of making and shaping of iron and steel in North America and Europe. In German and English.Schematic diagram of blast furnace and Cowper stove

{{DEFAULTSORT:Blast Furnace Chinese inventions Firing techniques Industrial buildings and structures Industrial furnaces Industrial Revolution Metallurgy Smelting Steelmaking

," Online Etymology Dictionary were

Rus' people

The Rus, also known as Russes, were a people in early medieval Eastern Europe. The scholarly consensus holds that they were originally Norsemen, mainly originating from present-day Sweden, who settled and ruled along the river-routes between t ...

from Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

traded with the Caspian (using their Volga trade route

In the Middle Ages, the Volga trade route connected Northern Europe and Northwestern Russia with the Caspian Sea and the Sasanian Empire, via the Volga River. The Rus' (people), Rus used this route to trade with Muslim history#The Umayyad Calipha ...

), it is possible that the technology reached Sweden by this means. The Vikings are known to have used double bellows, which greatly increases the volumetric flow of the blast.

The Caspian region may also have been the source for the design of the furnace at Ferriere

Ferriere (; Piacentino: ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Piacenza in the Italian region Emilia-Romagna, located about west of Bologna and about southwest of Piacenza, in the Val Nure of the Ligurian Apennines.

Ferriere bor ...

, described by Filarete

Antonio di Pietro Aver(u)lino (; – ), known as Filarete (; from , meaning "lover of excellence"), was a Florentine Renaissance architect, sculptor, medallist, and architectural theorist. He is perhaps best remembered for his design of the ide ...

, involving a water-powered bellows at Semogo in Valdidentro

Valdidentro is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Province of Sondrio in the Italian region Lombardy, located about northeast of Milan and about northeast of Sondrio, in the upper Alta Valtellina on the border with Switzerland.

It is the se ...

in northern Italy in 1226. In a two-stage process the molten iron was tapped twice a day into water, thereby granulating it.

Cistercian contributions

The General Chapter of theCistercian

The Cistercians (), officially the Order of Cistercians (, abbreviated as OCist or SOCist), are a Catholic religious order of monks and nuns that branched off from the Benedictines and follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, as well as the contri ...

monks spread some technological advances across Europe. This may have included the blast furnace, as the Cistercians are known to have been skilled metallurgists

Metallurgy is a domain of materials science and engineering that studies the physical and chemical behavior of metallic elements, their inter-metallic compounds, and their mixtures, which are known as alloys.

Metallurgy encompasses both the ...

.Woods, p. 34. According to Jean Gimpel, their high level of industrial technology facilitated the diffusion of new techniques: "Every monastery had a model factory, often as large as the church and only several feet away, and waterpower drove the machinery of the various industries located on its floor." Iron ore deposits were often donated to the monks along with forges to extract the iron, and after a time surpluses were offered for sale. The Cistercians became the leading iron producers in Champagne

Champagne (; ) is a sparkling wine originated and produced in the Champagne wine region of France under the rules of the appellation, which demand specific vineyard practices, sourcing of grapes exclusively from designated places within it, spe ...

, France, from the mid-13th century to the 17th century,Gimpel, p. 67. also using the phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

-rich slag from their furnaces as an agricultural fertilizer

A fertilizer or fertiliser is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from liming materials or other non-nutrient soil amendments. Man ...

.

Archaeologists are still discovering the extent of Cistercian technology.Woods, p. 36. At Laskill

Laskill is a small hamlet in Bilsdale, 5 miles (8 km) north-west of Helmsley, North Yorkshire, England, on the road from Helmsley to Stokesley and is located within the North York Moors National Park. Archaeological investigations ...

, an outstation of Rievaulx Abbey

Rievaulx Abbey ( ) was a Cistercian abbey in Rievaulx, near Helmsley, in the North York Moors National Park, North Yorkshire, England. It was one of the great abbeys in England until it was seized in 1538 under Henry VIII during the Dissolu ...

and the only medieval blast furnace so far identified in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, the slag produced was low in iron content.Woods, p. 37. Slag from other furnaces of the time contained a substantial concentration of iron, whereas Laskill is believed to have produced cast iron quite efficiently.David Derbyshire'Henry "Stamped Out Industrial Revolution"'

, ''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

'' (21 June 2002); cited by Woods. Its date is not yet clear, but it probably did not survive until Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

's Dissolution of the Monasteries in the late 1530s, as an agreement (immediately after that) concerning the "smythes" with the Earl of Rutland

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ''countess'' is used.

The titl ...

in 1541 refers to blooms. Nevertheless, the means by which the blast furnace spread in medieval Europe has not finally been determined.

Origin and spread of early modern blast furnaces

Namur

Namur (; ; ) is a city and municipality in Wallonia, Belgium. It is the capital both of the province of Namur and of Wallonia, hosting the Parliament of Wallonia, the Government of Wallonia and its administration.

Namur stands at the confl ...

region, in what is now Wallonia

Wallonia ( ; ; or ), officially the Walloon Region ( ; ), is one of the three communities, regions and language areas of Belgium, regions of Belgium—along with Flemish Region, Flanders and Brussels. Covering the southern portion of the c ...

(Belgium). From there, they spread first to the Pays de Bray

The Pays de Bray (, literally ''Land of Bray'') is a small (about 750 km2) natural region of France situated to the north-east of Rouen, straddling the French departments of the Seine-Maritime and the Oise (historically divided among the Pr ...

on the eastern boundary of Normandy

Normandy (; or ) is a geographical and cultural region in northwestern Europe, roughly coextensive with the historical Duchy of Normandy.

Normandy comprises Normandy (administrative region), mainland Normandy (a part of France) and insular N ...

and from there to the Weald

The Weald () is an area of South East England between the parallel chalk escarpments of the North and the South Downs. It crosses the counties of Hampshire, Surrey, West Sussex, East Sussex, and Kent. It has three parts, the sandstone "High W ...

of Sussex

Sussex (Help:IPA/English, /ˈsʌsɪks/; from the Old English ''Sūþseaxe''; lit. 'South Saxons'; 'Sussex') is an area within South East England that was historically a kingdom of Sussex, kingdom and, later, a Historic counties of England, ...

, where the first furnace (called Queenstock) in Buxted

Buxted is a village and civil parish in the Wealden District, Wealden district of East Sussex in England. The parish is situated on the Weald, north of Uckfield; the settlements of Five Ash Down, Heron's Ghyll and High Hurstwood are included wit ...

was built in about 1491, followed by one at Newbridge in Ashdown Forest

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald National Landscape. It is situated south of London in the county East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation

of above sea level, its ...

in 1496. They remained few in number until about 1530 but many were built in the following decades in the Weald, where the iron industry perhaps reached its peak about 1590. Most of the pig iron from these furnaces was taken to finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and decarburization, removing carbon from the molten cast iron through Redo ...

s for the production of bar iron

Wrought iron is an iron alloy with a very low carbon content (less than 0.05%) in contrast to that of cast iron (2.1% to 4.5%), or 0.25 for low carbon "mild" steel. Wrought iron is manufactured by heating and melting high carbon cast iron in an ...

.

The first British furnaces outside the Weald appeared during the 1550s, and many were built in the remainder of that century and the following ones. The output of the industry probably peaked about 1620, and was followed by a slow decline until the early 18th century. This was apparently because it was more economic to import iron from Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

and elsewhere than to make it in some more remote British locations. Charcoal that was economically available to the industry was probably being consumed as fast as the wood to make it grew.

The first blast furnace in Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

opened in 1637 near Tula and was called the Gorodishche Works. The blast furnace spread from there to central Russia and then finally to the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

.

Coke blast furnaces

In 1709, atCoalbrookdale

Coalbrookdale is a town in the Ironbridge Gorge and the Telford and Wrekin borough of Shropshire, England, containing a settlement of great significance in the history of iron ore smelting. It lies within the civil parish called The Gorge, Shro ...

in Shropshire, England, Abraham Darby Abraham Darby may refer to:

People

*Abraham Darby I (1678–1717) the first of several men of that name in an English Quaker family that played an important role in the Industrial Revolution. He developed a new method of producing pig iron with ...

began to fuel a blast furnace with coke instead of charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

. Coke's initial advantage was its lower cost, mainly because making coke required much less labor than cutting trees and making charcoal, but using coke also overcame localized shortages of wood, especially in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. Metallurgical grade coke will bear heavier weight than charcoal, allowing larger furnaces.

A disadvantage is that coke contains more impurities than charcoal, with sulfur being especially detrimental to the iron's quality. Coke's impurities were more of a problem before hot blast reduced the amount of coke required and before furnace temperatures were hot enough to make slag from limestone free flowing. (Limestone ties up sulphur. Manganese may also be added to tie up sulphur.)

Coke iron was initially only used for foundry

A foundry is a factory that produces metal castings. Metals are cast into shapes by melting them into a liquid, pouring the metal into a mold, and removing the mold material after the metal has solidified as it cools. The most common metals pr ...

work, making pots and other cast iron goods. Foundry work was a minor branch of the industry, but Darby's son built a new furnace at nearby Horsehay, and began to supply the owners of finery forge

A finery forge is a forge used to produce wrought iron from pig iron by decarburization in a process called "fining" which involved liquifying cast iron in a fining hearth and decarburization, removing carbon from the molten cast iron through Redo ...

s with coke pig iron for the production of bar iron. Coke pig iron was by this time cheaper to produce than charcoal pig iron. The use of a coal-derived fuel in the iron industry was a key factor in the British Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. However, in many areas of the world charcoal was cheaper while coke was more expensive even after the Industrial Revolution: e. g., in the US charcoal-fueled iron production fell in share to about a half but still continued to increase in absolute terms until , while in João Monlevade

João Monlevade is a Brazilian municipality located in the state of Minas Gerais. The city belongs to the mesoregion Metropolitana de fim do mundo Belo Horizonte and to the microregion of Itabira. As of 2020, the estimated population was 80,41 ...

in the Brazilian Highlands

The Brazilian Highlands or Brazilian Plateau () is an extensive geographical region covering most of the eastern, southern and central portions of Brazil, in all some 4,500,000 km2 (1,930,511 sq mi) or approximately half of the country's la ...

charcoal-fired blast furnaces were built as late as the 1930s and only phased out in 2000.

Darby's original blast furnace has been archaeologically excavated and can be seen in situ at Coalbrookdale, part of the Ironbridge Gorge

The Ironbridge Gorge is a deep gorge, containing the River Severn in Shropshire, England. It was first formed by a glacial overflow from the long drained away Lake Lapworth, at the end of the last ice age. The deep exposure of the rocks cut ...

Museums. Cast iron from the furnace was used to make girder

A girder () is a Beam (structure), beam used in construction. It is the main horizontal support of a structure which supports smaller beams. Girders often have an I-beam cross section composed of two load-bearing ''flanges'' separated by a sta ...

s for the world's first cast iron bridge in 1779. The Iron Bridge

The Iron Bridge is a cast iron arch bridge that crosses the River Severn in Shropshire, England. Opened in 1781, it was the first major bridge in the world to be made of cast iron. Its success inspired the widespread use of cast iron as a str ...

crosses the River Severn

The River Severn (, ), at long, is the longest river in Great Britain. It is also the river with the most voluminous flow of water by far in all of England and Wales, with an average flow rate of at Apperley, Gloucestershire. It rises in t ...

at Coalbrookdale and remains in use for pedestrians.

Steam-powered blast

The steam engine was applied to power blast air, overcoming a shortage of water power in areas where coal and iron ore were located. This was first done at Coalbrookdale where asteam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs Work (physics), mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a Cylinder (locomotive), cyl ...

replaced a horse-powered pump in 1742. Such engines were used to pump water to a reservoir above the furnace. The first engines used to blow cylinders directly was supplied by Boulton and Watt

Boulton & Watt was an early British engineering and manufacturing firm in the business of designing and making marine and stationary steam engines. Founded in the English West Midlands around Birmingham in 1775 as a partnership between the Engl ...

to John Wilkinson's New Willey Furnace. This powered a cast iron blowing cylinder, which had been invented by his father Isaac Wilkinson. He patented such cylinders in 1736, to replace the leather bellows, which wore out quickly. Isaac was granted a second patent, also for blowing cylinders, in 1757. The steam engine and cast iron blowing cylinder led to a large increase in British iron production in the late 18th century.

Hot blast

Hot blast

Hot blast is the preheated air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. This technology, which considerably reduces the fuel consumed, was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. Hot b ...

was the single most important advance in fuel efficiency of the blast furnace and was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

. Hot blast was patented by James Beaumont Neilson

James Beaumont Neilson (22 June 1792 – 18 January 1865) was a British inventor whose hot-blast process greatly increased the efficiency of smelting iron.

Life

He was the son of the engineer Walter Neilson, a millwright and later engine ...

at Wilsontown Ironworks in Britain in 1828. Within a few years of the introduction, hot blast was developed to the point where fuel consumption was cut by one-third using coke or two-thirds using coal, while furnace capacity was also significantly increased. Within a few decades, the practice was to have a "stove" as large as the furnace next to it into which the waste gas (containing CO) from the furnace was directed and burnt. The resultant heat was used to preheat the air blown into the furnace.Birch, pp. 181–189.

Hot blast enabled the use of raw anthracite

Anthracite, also known as hard coal and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a lustre (mineralogy)#Submetallic lustre, submetallic lustre. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy densit ...

coal, which was difficult to light, in the blast furnace. Anthracite was first tried successfully by George Crane at Ynyscedwyn Ironworks

Ynyscedwyn Ironworks is an industrial complex located in Ystradgynlais, near Swansea, Wales. Smelting was first established here in seventeenth century. In the 1820s, with the arrival of George Crane, production was expanded. Crane was the first i ...

in south Wales in 1837. It was taken up in America by the Lehigh Crane Iron Company

The Lehigh Crane Iron Company, later renamed Crane Iron Company, was a major ironmaking firm in the Lehigh Valley from its founding in 1839 until its sale in 1899. It was based in Catasauqua, Pennsylvania, and was founded by Josiah White and Ers ...

at Catasauqua, Pennsylvania

Catasauqua, referred to colloquially as Catty, is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, United States. Catasauqua's population was 6,518 at the 2020 census. It is a suburb of Allentown, Pennsylvania, Allentown in the ...

, in 1839. Anthracite use declined when very high capacity blast furnaces requiring coke were built in the 1870s.

Modern applications of the blast furnace

Iron blast furnaces

The blast furnace remains an important part of modern iron production. Modern furnaces are highly efficient, includingCowper stove

A regenerative heat exchanger, or more commonly a regenerator, is a type of heat exchanger where heat from the hot fluid is intermittently stored in a thermal storage medium before it is transferred to the cold fluid. To accomplish this the hot fl ...

s to pre-heat the blast air and employ recovery systems to extract the heat from the hot gases exiting the furnace. Competition in industry drives higher production rates. The largest blast furnace in the world is in South Korea, with a volume around . It can produce around of iron per year.

This is a great increase from the typical 18th-century furnaces, which averaged about per year. Variations of the blast furnace, such as the Swedish electric blast furnace, have been developed in countries which have no native coal resources.

According to ''Global Energy Monitor

Global Energy Monitor (GEM) is a San Francisco–based non-governmental organization which catalogs fossil fuel and renewable energy projects worldwide. GEM shares information in support of clean energy and its data and reports on energy trend ...

'', the blast furnace is likely to become obsolete to meet climate change

Present-day climate change includes both global warming—the ongoing increase in Global surface temperature, global average temperature—and its wider effects on Earth's climate system. Climate variability and change, Climate change in ...

objectives of reducing carbon dioxide emission, but BHP

BHP Group Limited, founded as the Broken Hill Proprietary Company, is an Australian multinational mining and metals corporation. BHP was established in August 1885 and is headquartered in Melbourne, Victoria.

As of 2024, BHP was the world� ...

disagrees. An alternative process involving direct reduced iron

Direct reduced iron (DRI), also called sponge iron, is produced from the direct reduction of iron ore (in the form of lumps, pellets, or fines) into iron by a reducing gas which contains elemental carbon (produced from natural gas or coal) and/o ...

(DRI) is likely to succeed it, but this also needs to use a blast furnace to melt the iron and remove the gangue

Gangue () is the commercially worthless material that surrounds, or is closely mixed with, a wanted mineral in an ore deposit. It is thus distinct from overburden, which is the waste rock or materials overlying an ore or mineral body that are di ...

(impurities) unless the ore is very high quality.

Oxygen blast furnace

The oxygen blast furnace (OBF) process, developed from the 1970s to the 1990s, has been extensively studied theoretically because of the potentials of promising energy conservation and emission reduction. This type may be the most suitable for use with CCS. The main blast furnace has of three levels; the reduction zone (), slag formation zone (), and the combustion zone (). OBFs are usually combined with top gas recycling. The problem with this, besides significant oxygen expenditures, is the uneven distribution of gas recycled from the top of the furnace to the middle, which collides with the hot gas from below. As of 2023, the technology is only practiced on the experimental level in Sweden, Japan and China.Blast furnaces in copper and lead smelting

Blast furnaces are currently rarely used in copper smelting, but modern lead smelting blast furnaces are much shorter than iron blast furnaces and are rectangular in shape.R J Sinclair, ''The Extractive Metallurgy of Lead'' (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2009), 77. Modern lead blast furnaces are constructed using water-cooled steel or copper jackets for the walls, and have no refractory linings in the side walls.R J Sinclair, ''The Extractive Metallurgy of Lead'' (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2009), 75. The base of the furnace is a hearth ofrefractory material

In materials science, a refractory (or refractory material) is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat or chemical attack and that retains its strength and rigidity at high temperatures. They are inorganic, non-metallic compound ...

(bricks or castable refractory). Lead blast furnaces are often open-topped rather than having the charging bell used in iron blast furnaces.

The blast furnace used at the Nyrstar

Nyrstar is an international producer of minerals and metals. It was founded in August 2007 and listed on the Euronext Brussels that October.

Nyrstar has mining, smelting and other operations located in Europe, the United States and Australia an ...

Port Pirie

Port Pirie is a small city on the east coast of the Spencer Gulf in South Australia, north of the state capital, Adelaide. Port Pirie is the largest city and the main retail centre of the Mid North region of South Australia. The city has an ex ...

lead smelter differs from most other lead blast furnaces in that it has a double row of tuyeres rather than the single row normally used. The lower shaft of the furnace has a chair shape with the lower part of the shaft being narrower than the upper. The lower row of tuyeres being located in the narrow part of the shaft. This allows the upper part of the shaft to be wider than the standard.

Zinc blast furnaces

The blast furnaces used in the Imperial Smelting Process ("ISP") were developed from the standard lead blast furnace, but are fully sealed.R J Sinclair, ''The Extractive Metallurgy of Lead'' (The Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Melbourne, 2009), 89. This is because the zinc produced by these furnaces is recovered as metal from the vapor phase, and the presence of oxygen in the off-gas would result in the formation of zinc oxide. Blast furnaces used in the ISP have a more intense operation than standard lead blast furnaces, with higher air blast rates per m2 of hearth area and a higher coke consumption. Zinc production with the ISP is more expensive than with electrolytic zinc plants, so several smelters operating this technology have closed in recent years. However, ISP furnaces have the advantage of being able to treat zinc concentrates containing higher levels of lead than can electrolytic zinc plants.Manufacture of stone wool

Stone wool or

Stone wool or rock wool

Rock most often refers to:

* Rock (geology), a naturally occurring solid aggregate of minerals or mineraloids

* Rock music, a genre of popular music

Rock or Rocks may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Rock, Caerphilly, a location in Wale ...

is a spun mineral fibre

Fiber (spelled fibre in British English; from ) is a natural or artificial substance that is significantly longer than it is wide. Fibers are often used in the manufacture of other materials. The strongest engineering materials often incorp ...

used as an insulation

Insulation may refer to:

Thermal

* Thermal insulation, use of materials to reduce rates of heat transfer

** List of insulation materials

** Building insulation, thermal insulation added to buildings for comfort and energy efficiency

*** Insulated ...

product and in hydroponic

Hydroponics is a type of horticulture and a subset of hydroculture which involves growing plants, usually crops or medicinal plants, without soil, by using water-based mineral nutrient solutions in an artificial environment. Terrestrial or ...

s. It is manufactured in a blast furnace fed with diabase

Diabase (), also called dolerite () or microgabbro,

is a mafic, holocrystalline, subvolcanic rock equivalent to volcanic basalt or plutonic gabbro. Diabase dikes and sills are typically shallow intrusive bodies and often exhibit fine-gra ...

rock which contains very low levels of metal oxides. The resultant slag is drawn off and spun to form the rock wool product. Very small amounts of metals are also produced which are an unwanted by-product

A by-product or byproduct is a secondary product derived from a production process, manufacturing process or chemical reaction; it is not the primary product or service being produced.

A by-product can be useful and marketable or it can be cons ...

.

Modern iron process

Modern furnaces are equipped with an array of supporting facilities to increase efficiency, such as ore storage yards where barges are unloaded. The raw materials are transferred to the stockhouse complex by ore bridges, or rail hoppers and ore transfer cars. Rail-mounted scale cars or computer controlled weight hoppers weigh out the various raw materials to yield the desired hot metal and slag chemistry. The raw materials are brought to the top of the blast furnace via a

Modern furnaces are equipped with an array of supporting facilities to increase efficiency, such as ore storage yards where barges are unloaded. The raw materials are transferred to the stockhouse complex by ore bridges, or rail hoppers and ore transfer cars. Rail-mounted scale cars or computer controlled weight hoppers weigh out the various raw materials to yield the desired hot metal and slag chemistry. The raw materials are brought to the top of the blast furnace via a skip

Skip or Skips may refer to:

Acronyms

* SKIP (Skeletal muscle and kidney enriched inositol phosphatase), a human gene

* Simple Key-Management for Internet Protocol

* SKIP of New York (Sick Kids need Involved People), a non-profit agency aiding ...

car powered by winches or conveyor belts.American Iron and Steel Institute (2005)How a Blast Furnace Works

steel.org. There are different ways in which the raw materials are charged into the blast furnace. Some blast furnaces use a "double bell" system where two "bells" are used to control the entry of raw material into the blast furnace. The purpose of the two bells is to minimize the loss of hot gases in the blast furnace. First, the raw materials are emptied into the upper or small bell which then opens to empty the charge into the large bell. The small bell then closes, to seal the blast furnace, while the large bell rotates to provide specific distribution of materials before dispensing the charge into the blast furnace. A more recent design is to use a "bell-less" system. These systems use multiple hoppers to contain each raw material, which is then discharged into the blast furnace through valves. These valves are more accurate at controlling how much of each constituent is added, as compared to the skip or conveyor system, thereby increasing the efficiency of the furnace. Some of these bell-less systems also implement a discharge chute in the throat of the furnace (as with the Paul Wurth top) in order to precisely control where the charge is placed. The iron making blast furnace itself is built in the form of a tall structure, lined with

refractory

In materials science, a refractory (or refractory material) is a material that is resistant to decomposition by heat or chemical attack and that retains its strength and rigidity at high temperatures. They are inorganic, non-metallic compound ...

brick, and profiled to allow for expansion of the charged materials as they heat during their descent, and subsequent reduction in size as melting starts to occur. Coke, limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

flux, and iron ore (iron oxide) are charged into the top of the furnace in a precise filling order which helps control gas flow and the chemical reactions inside the furnace. Four "uptakes" allow the hot, dirty gas high in carbon monoxide content to exit the furnace throat, while "bleeder valves" protect the top of the furnace from sudden gas pressure surges. The coarse particles in the exhaust gas settle in the "dust catcher" and are dumped into a railroad car or truck for disposal, while the gas itself flows through a venturi scrubber

A venturi scrubber is designed to effectively use the energy from a high-velocity inlet gas stream to atomize the liquid being used to scrub the gas stream. This type of technology is a part of the group of air pollution controls collectively ref ...

and/or electrostatic precipitators and a gas cooler to reduce the temperature of the cleaned gas.

The "casthouse" at the bottom half of the furnace contains the bustle pipe (a large-diameter annular pipe to deliver heated air under pressure to the tuyere

A tuyere or tuyère (; ) is a tube, nozzle or pipe allowing the blowing of air into a furnace or hearth.W. K. V. Gale, The iron and Steel industry: a dictionary of terms (David and Charles, Newton Abbot 1972), 216–217.

Air or oxygen is i ...

s) and the equipment for casting the liquid iron and slag. Once a "taphole" is drilled through the refractory clay plug, liquid iron and slag flow down a trough through a "skimmer" opening, separating the iron and slag. Modern, larger blast furnaces may have as many as four tapholes and two casthouses. Once the pig iron and slag has been tapped, the taphole is again plugged with refractory clay.

The tuyeres are used to implement a hot blast

Hot blast is the preheated air blown into a blast furnace or other metallurgical process. This technology, which considerably reduces the fuel consumed, was one of the most important technologies developed during the Industrial Revolution. Hot b ...

, which is used to increase the efficiency of the blast furnace. The hot blast is directed into the furnace through water-cooled copper nozzles called tuyeres near the base. The hot blast temperature can be from depending on the stove design and condition. The temperatures they deal with may be . Oil

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) and lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

, tar

Tar is a dark brown or black viscous liquid of hydrocarbons and free carbon, obtained from a wide variety of organic materials through destructive distillation. Tar can be produced from coal, wood, petroleum, or peat. "a dark brown or black b ...

, natural gas

Natural gas (also fossil gas, methane gas, and gas) is a naturally occurring compound of gaseous hydrocarbons, primarily methane (95%), small amounts of higher alkanes, and traces of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, hydrogen sulfide and helium ...

, powdered coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

and oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

can also be injected into the furnace at tuyere level to combine with the coke to release additional energy and increase the percentage of reducing gases present which is necessary to increase productivity.

The exhaust gasses of a blast furnace are generally cleaned in the dust collector

A dust collector is a system used to enhance the quality of air released from industrial and commercial processes by collecting dust particle and other impurities from air or gas. Designed to handle high-volume dust loads, a dust collector syste ...

– such as an inertia

Inertia is the natural tendency of objects in motion to stay in motion and objects at rest to stay at rest, unless a force causes the velocity to change. It is one of the fundamental principles in classical physics, and described by Isaac Newto ...

l separator, a baghouse

A baghouse, also known as a baghouse filter, bag filter, or fabric filter is an air pollution control device and dust collector that removes particulates entrained in gas released from commercial processes. Power plants, steel mills, pharmaceutical ...

, or an electrostatic precipitator

An electrostatic precipitator (ESP) is a filterless device that removes fine particles, such as dust and smoke, from a flowing gas using the force of an induced electrostatic charge minimally impeding the flow of gases through the unit.

In c ...

. Each type of dust collector has strengths and weaknesses – some collect fine particles, some coarse particles, some collect electrically charged particles. Effective exhaust clearing relies on multiple stages of treatment. Waste heat is usually collected from the exhaust gases, for example by the use of a Cowper stove