Iron Confederation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Iron Confederacy or Iron Confederation (also known as Cree-Assiniboine in English or in

The

The

In the south little political or economic history is recorded for several decades. Recounting his story to David Thompson many years later, a Cree man named Saukamappee told of a band of Cree aiding the Piegan (Blackfoot) in their conflict with the

In the south little political or economic history is recorded for several decades. Recounting his story to David Thompson many years later, a Cree man named Saukamappee told of a band of Cree aiding the Piegan (Blackfoot) in their conflict with the

From around 1850, the decline of the bison herds began to weaken the Iron Confederacy. The bison migrated seasonally, creating the potential for conflict over the right to harvest them.

This meant that many Plains peoples would often rely on the same herd; overhunting by one party (or European settlers) affected them all in a

From around 1850, the decline of the bison herds began to weaken the Iron Confederacy. The bison migrated seasonally, creating the potential for conflict over the right to harvest them.

This meant that many Plains peoples would often rely on the same herd; overhunting by one party (or European settlers) affected them all in a  By 1878 the buffalo crisis was now critical and despite the treaties, little material support was given by the Canadian government, forcing increasing numbers of both treaty and non-treaty bands from Canadian territory to hunt in Montana. In 1879 or 1880 the last remaining buffalo disappeared from Canadian territory, after this time many Cree and Assiniboine bands moved south, making frequent hunting trips into American-claimed territory, or even camping there year-round.

This was seen as a threat by white settlers in Montana in light of

By 1878 the buffalo crisis was now critical and despite the treaties, little material support was given by the Canadian government, forcing increasing numbers of both treaty and non-treaty bands from Canadian territory to hunt in Montana. In 1879 or 1880 the last remaining buffalo disappeared from Canadian territory, after this time many Cree and Assiniboine bands moved south, making frequent hunting trips into American-claimed territory, or even camping there year-round.

This was seen as a threat by white settlers in Montana in light of

In 1885, the Métis were soliciting aid in the lead-up to the 1885

In 1885, the Métis were soliciting aid in the lead-up to the 1885

Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

) was a political and military alliance

A military alliance is a formal Alliance, agreement between nations that specifies mutual obligations regarding national security. In the event a nation is attacked, members of the alliance are often obligated to come to their defense regardless ...

of Plains Indians

Plains Indians or Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies are the Native American tribes and First Nations peoples who have historically lived on the Interior Plains (the Great Plains and Canadian Prairies) of North ...

of what is now Western Canada

Western Canada, also referred to as the Western provinces, Canadian West, or Western provinces of Canada, and commonly known within Canada as the West, is a list of regions of Canada, Canadian region that includes the four western provinces and t ...

and the northern United States

The Northern United States, commonly referred to as the American North, the Northern States, or simply the North, is a geographical and historical region of the United States.

History Early history

Before the 19th century westward expansion, the ...

. This confederacy

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

included various individual bands Bands may refer to:

* Bands (song), song by American rapper Comethazine

* Bands (neckwear), form of formal neckwear

* Bands (Italian Army irregulars)

Bands () was an Italian military term for Irregular military, irregular forces, composed of nati ...

that formed political, hunting and military alliances in defense against common enemies. The ethnic groups that made up the Confederacy were the branches of the Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

that moved onto the Great Plains

The Great Plains is a broad expanse of plain, flatland in North America. The region stretches east of the Rocky Mountains, much of it covered in prairie, steppe, and grassland. They are the western part of the Interior Plains, which include th ...

around 1740 (the southern half of this movement eventually became the " Plains Cree" and the northern half the "Woods Cree

Woods Cree is an indigenous language spoken in Northern Manitoba, Northern Saskatchewan and Northern Alberta, Canada. It is part of the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi dialect continuum. The dialect continuum has around 116,000 speakers; the exact popul ...

"), the Saulteaux

The Saulteaux (pronounced , or in imitation of the French pronunciation , also written Salteaux, Saulteau and Ojibwa ethnonyms, other variants), otherwise known as the Plains Ojibwe, are a First Nations in Canada, First Nations band governm ...

(Plains Ojibwa), the Nakoda or Stoney people also called Pwat or Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakoda ...

, and the Métis

The Métis ( , , , ) are a mixed-race Indigenous people whose historical homelands include Canada's three Prairie Provinces extending into parts of Ontario, British Columbia, the Northwest Territories and the northwest United States. They ha ...

and Haudenosaunee

The Iroquois ( ), also known as the Five Nations, and later as the Six Nations from 1722 onwards; alternatively referred to by the Endonym and exonym, endonym Haudenosaunee ( ; ) are an Iroquoian languages, Iroquoian-speaking Confederation#Ind ...

(who had come west with the fur trade). The Confederacy rose to predominance on the northern Plains during the height of the North American fur trade

The North American fur trade is the (typically) historical Fur trade, commercial trade of furs and other goods in North America, beginning in the eastern provinces of French Canada and the northeastern Thirteen Colonies, American colonies (soon- ...

when they operated as middlemen controlling the flow of European goods, particularly guns and ammunition, to other Indigenous nations (the "Indian Trade Indian Trade could refer to:

* Native American trade, historic trading between the Indigenous people of North America and European settlers

* Foreign trade of India

Foreign may refer to:

Government

* Foreign policy, how a country interacts with o ...

"), and the flow of furs to the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

(HBC) and North West Company

The North West Company was a Fur trade in Canada, Canadian fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in the regions that later became Western Canada a ...

(NWC) trading posts. Its peoples would take part in the bison (buffalo) hunt, and the pemmican

Pemmican () (also pemican in older sources) is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigeno ...

trade. The decline of the fur trade and the collapse of the bison herds sapped the power of the Confederacy after the 1860’s.

Origins

The

The Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakoda ...

are believed to have originated on the southern edge of the Laurentian Shield

The Canadian Shield ( ), also called the Laurentian Shield or the Laurentian Plateau, is a geologic shield, a large area of exposed Precambrian igneous and high-grade metamorphic rocks. It forms the North American Craton (or Laurentia), the a ...

in present-day Minnesota

Minnesota ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Upper Midwestern region of the United States. It is bordered by the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario to the north and east and by the U.S. states of Wisconsin to the east, Iowa to the so ...

. They became a separate people from their closest linguistic cousins, the Yanktonai Dakota

The Dakota (pronounced , or ) are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into the Eastern Dakota and the Wester ...

, sometime prior to 1640 when they are first mentioned by Europeans in the Jesuit Relation

''The Jesuit Relations'', also known as ''Relations des Jésuites de la Nouvelle-France (Relation de ce qui s'est passé ..'', are chronicles of the Jesuit Mission (Christian), missions in New France. The works were written annually and print ...

. They were not a member of the "Seven Fires Council" of the Great Sioux Nation

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin ( ; Dakota/Lakota: ) are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples (translatio ...

by this time and were referred to by other Sioux speakers as the ''Hohe'' or "rebels". By 1806, the historical evidence definitively locates them in the Assiniboine River

The Assiniboine River ( ; ) is a long river that runs through the prairies of Western Canada in Saskatchewan and Manitoba. It is a tributary of the Red River. The Assiniboine is a typical meandering river with a single main channel embanked ...

valley in present-day Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

The Cree

The Cree, or nehinaw (, ), are a Indigenous peoples of the Americas, North American Indigenous people, numbering more than 350,000 in Canada, where they form one of the country's largest First Nations in Canada, First Nations. They live prim ...

had been in contact with Europeans since around 1611 when Henry Hudson

Henry Hudson ( 1565 – disappeared 23 June 1611) was an English sea explorer and navigator during the early 17th century, best known for his explorations of present-day Canada and parts of the Northeastern United States.

In 1607 and 16 ...

reached their ancestral homeland around Hudson

Hudson may refer to:

People

* Hudson (given name)

* Hudson (surname)

* Hudson (footballer, born 1986), Hudson Fernando Tobias de Carvalho, Brazilian football right-back

* Hudson (footballer, born 1988), Hudson Rodrigues dos Santos, Brazilian f ...

and James Bay

James Bay (, ; ) is a large body of water located on the southern end of Hudson Bay in Canada. It borders the provinces of Quebec and Ontario, and is politically part of Nunavut. Its largest island is Akimiski Island.

Numerous waterways of the ...

s." The traditional view of historians, based on the accounts of European traders, is that once the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC), originally the Governor and Company of Adventurers of England Trading Into Hudson’s Bay, is a Canadian holding company of department stores, and the oldest corporation in North America. It was the owner of the ...

(HBC) began to establish itself in the Hudson Bay region, two branches of the Cree began moving west and south to act as middlemen traders. They denied other plains peoples access to the HBC, except for the Assiniboine, in exchange for peaceful relations.Milloy, 5 A more recent view, based on oral history and linguistic evidence, suggests that the Cree were already established west of Lake Winnipeg

Lake Winnipeg () is a very large, relatively shallow lake in North America, in the Canadian province of Manitoba. Its southern end is about north of the city of Winnipeg. Lake Winnipeg is Canada's sixth-largest freshwater lake and the third- ...

when the HBC arrived, and were likely present as far west as the Peace River Region

The Peace River Country (or Peace Country; ) is an aspen parkland region centring on the Peace River in Canada. It extends from northwestern Alberta to the Rocky Mountains in northeastern British Columbia, where a certain portion of the region is ...

of present-day Alberta.

When the Hudson's Bay Company opened its first bayside posts in 1668 and 1688, the Cree became their main customers and resellers. Prior to this the Cree had been at the northwestern edge of a trade system linked to the French, from which they received only the secondhand goods others were ready to discard. Once in possession of direct access to European tools and weapons, the Cree were able to expand rapidly West.

The earliest written record of the military and political relations of the nations west of Hudson's Bay comes from Henry Kelsey

Henry Kelsey ( – 1 November 1724) was an English fur trader, explorer, and sailor who played an important role in establishing the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada.

He is the first recorded European to have visited the present-day provin ...

's journal . In it, he states that the Cree and the Assiniboine had good relations with the Blackfoot

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'', or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or " Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up the Blackfoot or Bl ...

and were already allies against the "Eagle Birch Indians, Mountain Poets, and Nayanwattame Poets" (the identities of these groups are uncertain but they may have been other Siouan-speakers, or Gros Ventre

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning 'big belly'), also known as the A'aninin, Atsina, or White Clay, are a historically Algonquian-speaking Native American tribe located in northcentral Montana. Today, the Gros Ventre people are enrolled in the Fort ...

s).

The history of the Stoney

Stoney may refer to:

Places

* Stoney, Kansas, an unincorporated community in the United States

* Stoney Creek (disambiguation)

* Stoney Pond, a man-made lake located by Bucks Corners, New York

* Stoney (lunar crater)

* Stoney (Martian crater)

...

before the mid-eighteenth century are obscure. They speak a Siouan language they call , which is little different from Assiniboine

The Assiniboine or Assiniboin people ( when singular, Assiniboines / Assiniboins when plural; Ojibwe: ''Asiniibwaan'', "stone Sioux"; also in plural Assiniboine or Assiniboin), also known as the Hohe and known by the endonym Nakota (or Nakoda ...

. The present-day Stoney Nation of Alberta believes that Kelsey's mention of the "Mountain Poets" may refer to their ancestors. However, the consensus view is that they were not yet a separate people from the Assiniboine. There is clear evidence of them as a separate group from 1754–1755 when Anthony Henday

Anthony Henday (fl. c. 1725–1762) was one of the first Europeans to explore the interior of what would eventually become western Canada. He ventured farther into the interior of western Canada than any European had before him.

As an employe ...

wrote of camping with "Stone" families near present-day Red Deer, Alberta

Red Deer is a city in Alberta, Canada, located midway on the Calgary–Edmonton Corridor. Red Deer serves central Alberta, and its key industries include health care, retail trade, construction, oil and gas, hospitality, manufacturing and educati ...

. The Stoney were already trading with the Cree fur traders at this point and were military allies.

Early expansion and the fur trade

American ethnographer and historianEdward S. Curtis

Edward Sheriff Curtis (February 19, 1868 – October 19, 1952; sometimes given as Edward Sherriff Curtis) was an American photographer and ethnologist whose work focused on the American West and Native American people. Sometimes referred to a ...

wrote about the close but unstable relationship between the Assiniboine and the Plains Cree, and how, after the Plains and Woods Cree territories diverged, the Woods Cree were no longer a part of this military alliance:

During this early period the north front of expansion is better documented. By the early 1700s the Cree had come into conflict with the Chipewyan

The Chipewyan ( , also called ''Denésoliné'' or ''Dënesųłı̨né'' or ''Dënë Sųłınë́'', meaning "the original/real people") are a Dene group of Indigenous Canadian people belonging to the Athabaskan language family, whose ancest ...

to their northwest. With the help of a Chipewyan interpreter, Thanadelthur

Thanadelthur "Thanadeltth'er" (c. 1697 – 5 February 1717) was a woman of the Chipewyan Dënesųłı̨ne nation who served as a guide and interpreter for the Hudson's Bay Company. She was instrumental in forging a peace agreement between th ...

(a woman who had learned the Cree language as a captive), the HBC was able to help broker a peace between the Cree and Chipewyan in 1715. By 1760, the western front of Cree expansion reached the Lesser Slave Lake

Lesser Slave Lake is located in northern Alberta, Canada, northwest of Edmonton. It is the second largest lake entirely within Alberta boundaries (and the largest easily accessible by vehicle), covering and measuring over long and at its wid ...

region of what is now northern Alberta

Northern Alberta is a geographic region located in the Canadian province of Alberta.

An informally defined cultural region, the boundaries of Northern Alberta are not fixed. Under some schemes, the region encompasses everything north of the ce ...

where the Cree eventually pushed out the Beaver (Danezaa) people. The Cree-Beaver conflicts lasted until the smallpox epidemic

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by Variola virus (often called Smallpox virus), which belongs to the genus ''Orthopoxvirus''. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO ...

in 1781 decimated the Cree in the region, leading to a peace treaty ratified by a pipe

Pipe(s), PIPE(S) or piping may refer to:

Objects

* Pipe (fluid conveyance), a hollow cylinder following certain dimension rules

** Piping, the use of pipes in industry

* Smoking pipe

** Tobacco pipe

* Half-pipe and quarter pipe, semi-circular ...

ceremony at Peace Point, which gave its name to the Peace River

The Peace River () is a river in Canada that originates in the Rocky Mountains of northern British Columbia and flows to the northeast through northern Alberta. The Peace River joins the Athabasca River in the Peace-Athabasca Delta to form the ...

. The river became the boundary with the Beavers on the left bank (to the north and west) and the Cree on the right bank (the south and east).

In the south little political or economic history is recorded for several decades. Recounting his story to David Thompson many years later, a Cree man named Saukamappee told of a band of Cree aiding the Piegan (Blackfoot) in their conflict with the

In the south little political or economic history is recorded for several decades. Recounting his story to David Thompson many years later, a Cree man named Saukamappee told of a band of Cree aiding the Piegan (Blackfoot) in their conflict with the Snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

near the Eagle Hills around 1723. The battle was fought on foot with bows-and-arrows tipped with obsidian

Obsidian ( ) is a naturally occurring volcanic glass formed when lava extrusive rock, extruded from a volcano cools rapidly with minimal crystal growth. It is an igneous rock. Produced from felsic lava, obsidian is rich in the lighter element ...

, and neither guns nor horses were involved at this point. By 1732 the Snakes had horses, which they were using to great effect against the Piegan, and so the Piegan called upon the Cree and Assiniboine for assistance. This time, however, Sukamappee says that Cree and Assiniboine muskets turned the battle in their favour. By 1750, Legardeur de Saint Pierre noted that the Cree and Assiniboine were successfully raiding the "Hyactljlini" "Brochets" and "Gros Ventres", and despite his peacemaking efforts the Assiniboine massacred a group of the "Hyactljlini" (whose identity is unknown).

In 1754 Henday reported that he was able to buy a horse from the Assiniboine camped near present-day Battleford, Saskatchewan

Battleford ( 2021 population 4,400) is a town located across the North Saskatchewan River from the city of North Battleford, in Saskatchewan, Canada.

Battleford and North Battleford are collectively referred to as "The Battlefords". Although ...

, and was the first European witness to Cree-Assiniboine trade with the "Archithinue" (Blackfoot Confederacy

The Blackfoot Confederacy, ''Niitsitapi'', or ''Siksikaitsitapi'' (ᖹᐟᒧᐧᒣᑯ, meaning "the people" or "Blackfoot language, Blackfoot-speaking real people"), is a historic collective name for linguistically related groups that make up ...

). From this and later accounts, the content of the trade is well known: the Cree and Assiniboine gave European goods including guns, knives, kettles, hatchets, and gunpowder to the Blackfoot people in exchange for horses, buffalo-skin robes, and wolf, beaver, and fox furs, which they would take to York Factory

York Factory was a settlement and Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) factory (trading post) on the southwestern shore of Hudson Bay in northeastern Manitoba, Canada, at the mouth of the Hayes River, approximately south-southeast of Churchill.

York ...

(the Blackfoot people refused HBC proposals that they go to the Bay directly, as it was too far and, as a plains people, they were not experienced canoeists). A gun was worth roughly fifty beavers, and a horse was worth one gun according to Henday. In 1772, Mathew Cocking reported that the Cree and Assiniboine with whom he travelled were always alarmed when they saw an unknown horse, fearing that they might belong to the Snakes. Cocking also suggests that at this time the Cree-Assiniboine held an annual gathering with the Blackfoot in March near Saskatchewan River Forks

Saskatchewan River Forks is a provincial recreation site in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan at the confluence of the North Saskatchewan and South Saskatchewan Rivers. The rivers, which have their headwaters in the Rocky Mountains, com ...

where they would trade and the Blackfoot would ask for volunteers for their wars with the Snakes.

Transition to Plains Culture

As the HBC and NWC moved inland to the West, the Confederacy also moved inland and west so that they would not lose their control of the trade. As the HBC and NWC moved northwards and inland after 1760, the Crees were no longer required as intermediaries to ferry furs from place to another, but they gained new opportunities in the supply ofpemmican

Pemmican () (also pemican in older sources) is a mixture of tallow, dried meat, and sometimes dried berries. A calorie-rich food, it can be used as a key component in prepared meals or eaten raw. Historically, it was an important part of indigeno ...

(dried bison meat) and other provisions that European fur traders needed when travelling to the companies' new posts in the subarctic

The subarctic zone is a region in the Northern Hemisphere immediately south of the true Arctic, north of hemiboreal regions and covering much of Alaska, Canada, Iceland, the north of Fennoscandia, Northwestern Russia, Siberia, and the Cair ...

. Some Cree, historically a woodland people, adopted the ways of the plains people, including nomadic bison hunting

Bison hunting (hunting of the American bison, also commonly known as the American buffalo) was an lifeway, activity fundamental to the economy and society of the Plains Indians peoples who inhabited the Great bison belt, vast grasslands on the ...

and horsemanship. These emerging Plains Cree were initially allies of the Blackfoot, helping them to drive the Kootenay and Snakes across the Rocky Mountains. At the same time, many Assiniboine people moved farther west, eventually spawning the Nakoda (Stoney)

The Nakoda (also known as Stoney, , or Stoney Nakoda) are an Indigenous people in Western Canada and the United States.

Their territory used to be large parts of what is now Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Montana, but their reserves are now in Al ...

people, who were a separate group by about 1744.

The Confederacy fought a series of wars over the control of the trade in major commodities on the plains. Before 1790, the Cree relied on the Mandan

The Mandan () are a Native American tribe of the Great Plains who have lived for centuries primarily in what is now North Dakota. They are enrolled in the Three Affiliated Tribes of the Fort Berthold Reservation. About half of the Mandan still ...

as a source of horses, for their own use and to trade to the isolated European fur trade posts. They were allies of the Blackfoot and Mandan against the Sioux in the great horse wars of this period. The Cree made significant profits from the trade with the Blackfoot; one HBC journal entry notes that a Cree trader bought a musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually dis ...

from the HBC for 14 prime beaver pelts and sold it to a Blackfoot warrior for 50 prime beaver pelts. From the Mandan they also received beans, maize, and tobacco, in exchange for European goods.

By the mid-19th century, the Confederacy had lost control of the trade with the Mandan. From 1790 to 1810, intermittent wars were fought between the Confederacy and its former horse suppliers to the south. As the Confederacy reached out to the Arapaho

The Arapaho ( ; , ) are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

By the 1850s, Arapaho bands formed t ...

as a potential new source of horses, they were blocked by the Gros Ventres

The Gros Ventre ( , ; meaning 'big belly'), also known as the A'aninin, Atsina, or White Clay, are a historically Algonquian languages, Algonquian-speaking Native Americans in the United States, Native American tribe located in northcentral Monta ...

. In 1790, the Gros Ventres joined the Blackfoot Confederacy, making the Iron Confederacy and the Blackfoot enemies for the first time. In response, the Plains Cree allied with the "Flathead" (Salish) Indians as a new source of horses. In the 1810s, Peter Fidler

Peter Fidler (16 August 1769 – 17 December 1822) was a British surveyor, map-maker, fur trader and explorer who had a long career in the employ of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) in what later became Canada. He was born in Bolsover, Derbyshir ...

described the Cree and Sacree peacefully sharing the Beaver Hills, but he also records that a new geographical place name had been added to the region, the Battle River

Battle River is a river in central Alberta and western Saskatchewan, Canada. It is a major tributary of the North Saskatchewan River.

The Battle River flows for and drains a total area of . Its mean discharge at the mouth is 10 m³/s. ...

, which had not been mentioned by this name before, was so-called to commemorate a battle between the Cree and Blackfoot, who would go on to be long-term rivals. By the 1830s, the mixed buffalo-hunting parties of Crees, Assiniboine, and Métis reached what is now northern Montana, and the United States government gave the Crees some limited recognition when U.S. officials invited the Cree leader "Broken Arm" (Maskepetoon) as one of the representatives of tribes living near Fort Union to meet President Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before Presidency of Andrew Jackson, his presidency, he rose to fame as a general in the U.S. Army and served in both houses ...

in Washington D.C.

Histories of this later period do not clearly state which bands are being referred to when it is said that "the Cree" were in a particular place. Neal McLeod makes clear that these bands were loose, temporary groupings that were often multiethnic and multilingual, so that most mentions of "the Cree" by historians of previous decades actually refers to mixed Cree-Assiniboine-Saulteax groups. Further, the whooping cough

Whooping cough ( or ), also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious, Vaccine-preventable diseases, vaccine-preventable Pathogenic bacteria, bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common c ...

outbreak of 1819–1820 and the smallpox outbreak of 1780–1781 decimated many bands, forcing them to merge with neighbours.

In 1846, travelling artist Paul Kane

Paul Kane (September 3, 1810 – February 20, 1871) was an Irish-born Canadian painter whose paintings and especially field sketches were known as one of the first visual documents of Western indigenous life.

A largely self-educated artist, P ...

identified a man he met at Fort Pitt, Kee-a-kee-ka-sa-coo-way, as "head chief" of the Cree, though it is doubtful that any such title existed. Kane mentions a man named Mukeetoo as his associate, but historians believe this person to be Black Powder, who was Plains Ojibwa rather than Cree. This may indicate how intertwined the two peoples were at this time.

By the 1850s, two bands, the "Cree-Assiniboine" or (also called the "Cree-speaking Assiniboine" or the "Young Dogs"), and the Qu'Appelle were established in the region between Wood Mountain and the Cypress Hills and traded on both sides of the international border.

From around 1800 to 1850, the Iron Confederacy was at its apogee, controlling the trade with HBC posts such as Fort Pitt and Fort Edmonton

Fort Edmonton (also named Edmonton House) was the name of a series of Trading post, trading posts of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) from 1795 to 1914, all of which were located on the north banks of the North Saskatchewan River in what is now ce ...

. Their southern expansion peaked in the 1860s when the Plains Cree controlled most of present-day southern Saskatchewan and east-central Alberta with the Assiniboine also moving south.

Decline

tragedy of the commons

The tragedy of the commons is the concept that, if many people enjoy unfettered access to a finite, valuable resource, such as a pasture, they will tend to overuse it and may end up destroying its value altogether. Even if some users exercised vo ...

. The bison would frequently move across tribal boundaries, and desperate hunters would be tempted to follow, leading to frequent disputes. The bison declined sooner in the parkland belt where the Cree lived then on the shortgrass prairie

The shortgrass prairie is an ecosystem located in the Great Plains of North America. The two most dominant grasses in the shortgrass prairie are blue grama (''Bouteloua gracilis'') and buffalograss (''Bouteloua dactyloides''), the two less domin ...

s to the south. The Cree blamed the HBC and Métis for this, but still needed them for trade. Bison could still be found on Blackfoot territories, forcing Cree hunting bands to stray into Blackfoot territory, leading to conflict. During these buffalo wars, alliances shifted once again, however the Iron Confederacy was never able to regain (permanent) access to the bison herds.

A legendary (perhaps fictional) story tells of a peace between the Cree and the Blackfoot made at the future site of Wetaskiwin

Wetaskiwin ( ) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. The city is located south of the provincial capital of Edmonton. The city name comes from the Cree word , meaning "the hills where peace was made".

Wetaskiwin is home to the Reyn ...

, Alberta, in 1867; even if true, this peace did not hold. Around 1870 the Gros Ventre, formerly part of the Blackfoot Confederacy for some 90 years, defected and became allies of the Assiniboine. The Plains Cree engaged in one last battle against the Blackfoot, the Battle of the Belly River

The Battle of the Belly River was the last major conflict between the Cree (the Iron Confederacy) and the Blackfoot Confederacy, and the last major battle between First Nations on Canadian soil.

The battle took place within the present limits ...

on October 25, 1870, near present-day Lethbridge

Lethbridge ( ) is a city in the province of Alberta, Canada. With a population of 106,550 in the 2023 Alberta municipal censuses, 2023 municipal census, Lethbridge became the fourth Alberta city to surpass 100,000 people. The nearby Canadian ...

, Alberta, but lost at least 200 warriors. Following this, in 1873, Blackfoot leader Crowfoot

Crowfoot (c. 1830 – 25 April 1890) or Isapo-Muxika (; syllabics: ) was a chief of the Siksika. His father, (Packs a Knife), and mother, (Attacked Towards Home), were Kainai. He was five years old when was killed during a raid on the Crow ...

ceremonially adopted Poundmaker

Poundmaker ( – 4 July 1886), also known as ''pîhtokahânapiwiyin'' (), was a Plains Cree chief known as a peacemaker and defender of his people, the Poundmaker Cree Nation. His name denotes his special craft at leading buffalo into buf ...

of mixed Cree and Assiniboine parentage, creating a final peace between the Cree and Blackfoot.Dempsey, H. A. (1972). Crowfoot, chief of the Blackfeet, (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, P. 72

In 1869 the Canadian government bought the HBC's claim to what is now western Canada. The Métis objected to not having been consulted and negotiated the ''Manitoba Act

The ''Manitoba Act, 1870'' ()Originally entitled (until renamed in 1982) ''An Act to amend and continue the Act 32 and 33 Victoria, chapter 3; and to establish and provide for the Government of the Province of Manitoba.'' is an act of the Parli ...

''. The Métis were not able to rally the Cree or Assiniboine to their cause, and the Wolseley expedition

The Wolseley expedition was a military force authorized by Canadian Prime Minister John A. Macdonald to confront Louis Riel and the Métis in 1870, during the Red River Rebellion, at the Red River Colony in what is now the province of Manitoba. ...

instead put down the Red River Resistance

The Red River Rebellion (), also known as the Red River Resistance, Red River uprising, or First Riel Rebellion, was the sequence of events that led up to the 1869 establishment of a provisional government by Métis leader Louis Riel and his f ...

with military force during the annual buffalo hunt rather than overseeing the implementation of the ''Manitoba Act'' as had been negotiated.

The decline of the buffalo had become a subsistence crisis

A subsistence crisis affects individuals or communities unable to obtain basic necessities due to either man-made or natural factors such as inflation, drought or war."The European subsistence crisis of 1845–1850: a comparative perspective", h ...

for the member bands of the Confederacy by the 1870s which led them to seek help from the Canadian government. The Canadian government was only willing to give this in exchange for treaties which they believed would extinguish their aboriginal title

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the Indigenous land rights, land rights of indigenous peoples to customary land, customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another Colonization, colonising state. ...

. The Confederacy was always a loose grouping, and when the Canadian government negotiated treaties in the region in the 1870s, the agreements were made with groups of bands, not with any central leadership. Each band, consisting of a few dozen or at most a few hundred people nominated its own leader to sign treaties on the group's behalf. Member bands of the Confederacy were signatories to Treaty 1

''Treaty 1'' (also known as the "Stone Fort Treaty") is an agreement established on August 3, 1871, between the Crown and the Anishinaabe and Swampy Cree, Canadian based First Nations. The first of a series of treaties called the Numbered Treatie ...

(1871, southern Manitoba), Treaty 4

Treaty 4 is a treaty established between Queen Victoria and the Cree and Saulteaux First Nation band governments. The area covered by Treaty 4 represents most of current day southern Saskatchewan, plus small portions of what are today western M ...

(signings 1874–1877, now southern Saskatchewan), Treaty 5

''Treaty Five'' is a treaty between Queen Victoria and Saulteaux and Swampy Cree non-treaty band governments and peoples around Lake Winnipeg in the District of Keewatin.

A written text is included in ; see also Much of what is today ce ...

(signings 1875–1879 plus later additions, now northern Manitoba), and Treaty 6

Treaty 6 is the sixth of the numbered treaties that were signed by the Canadian Crown and various First Nations between 1871 and 1877. It is one of a total of 11 numbered treaties signed between the Canadian Crown and First Nations. Specifi ...

(signings 1876–1879, many later additions, now central Saskatchewan and Alberta). Notably, these were negotiated separately from Treaty 7

Treaty 7 is an agreement between the Crown and several, mainly Blackfoot, First Nation band governments in what is today the southern portion of Alberta. The idea of developing treaties for Blackfoot lands was brought to Blackfoot chief Cro ...

(1877) with the Blackfoot Confederacy, showing that the Canadian government recognized the differences between the two groups. Under the terms of these treaties, the member bands of the Iron Confederacy accepted the presence of Canadian settlers on their lands in exchange for emergency and ongoing aid to deal with the starvation being experienced by the plains people due to the disappearance of the bison herds. Not all bands were equally reconciled to the ideas of the treaties. Piapot's band signed into a treaty but refused to choose a site for a reserve, preferring to remain nomadic. The "Battle River

Battle River is a river in central Alberta and western Saskatchewan, Canada. It is a major tributary of the North Saskatchewan River.

The Battle River flows for and drains a total area of . Its mean discharge at the mouth is 10 m³/s. ...

Crees" under the leadership of Big Bear and Little Pine refused to sign altogether.

By 1878 the buffalo crisis was now critical and despite the treaties, little material support was given by the Canadian government, forcing increasing numbers of both treaty and non-treaty bands from Canadian territory to hunt in Montana. In 1879 or 1880 the last remaining buffalo disappeared from Canadian territory, after this time many Cree and Assiniboine bands moved south, making frequent hunting trips into American-claimed territory, or even camping there year-round.

This was seen as a threat by white settlers in Montana in light of

By 1878 the buffalo crisis was now critical and despite the treaties, little material support was given by the Canadian government, forcing increasing numbers of both treaty and non-treaty bands from Canadian territory to hunt in Montana. In 1879 or 1880 the last remaining buffalo disappeared from Canadian territory, after this time many Cree and Assiniboine bands moved south, making frequent hunting trips into American-claimed territory, or even camping there year-round.

This was seen as a threat by white settlers in Montana in light of Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull ( ; December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota people, Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against Federal government of the United States, United States government policies. Sitting Bull was killed by Indian ...

leading his Sioux into Canada in 1876 to escape the American military: it was feared that Indian groups from either side could attack Americans and then use Canada as a safe haven. In response the United States began to militarize its frontier in the region, constructing Fort Assinniboine

Fort Assinniboine was a United States Army fort located in present-day north central Montana (historically within the military Department of Dakota). It was built in 1879 and operated by the Army through 1911. The 10th Cavalry Buffalo Soldie ...

near the Bears Paw Mountains

The Bears Paw Mountains (Bear Paw Mountains, Bear's Paw Mountains or Bearpaw Mountains) are an insular-montane island range in the Central Montana Alkalic Province in north-central Montana, United States, located approximately 10 miles south o ...

in 1879 and Fort Maginnis

Fort Maginnis was established during the Indian wars in the Department of Dakota by the U.S. Army. It was the last of five forts: Fort Keogh, Keogh (1876), Fort Custer (Montana), Custer (1877), Fort Missoula, Missoula (1877), Fort Assinniboine, Ass ...

in the Judith Basin in 1880. In that same year a Canadian report estimated seven to eight thousand "British Indians" were hunting in Montana, including three of the most famous Aboriginal leaders in Western Canadian history who were encamped together: a Cree band under Big Bear, the Blackfoot under Crowfoot, and a group of Metis hunters including Louis Riel

Louis Riel (; ; 22 October 1844 – 16 November 1885) was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis in Canada, Métis people. He led two resistance movements against the Government of ...

. Governmental opinion in both Canada and the US quickly turned against the previous policy of allowing the free movement of native people across the frontier. Authorities in both countries wanted natives to "civilize", by ending their nomadic hunting traditions, and take up agriculture on reserves, thereby opening the land up for white ranchers and farmers. Both countries wanted to symbolically enforce their control of the land and its native inhabitants. Cree and Metis parties continued to hunt in Montana until late 1881 when the US Army began to arrest and deport them, effectively cutting them off from one of the last remaining bison populations and ensuring their dependence on government-supplied rations.

Defeat

In 1885, the Métis were soliciting aid in the lead-up to the 1885

In 1885, the Métis were soliciting aid in the lead-up to the 1885 North-West Rebellion

The North-West Rebellion (), was an armed rebellion of Métis under Louis Riel and an associated uprising of Cree and Assiniboine mostly in the District of Saskatchewan, against the Government of Canada, Canadian government. Important events i ...

. Many Cree and Assiniboine were dissatisfied with their situation, believing that the Canadian government was not living up to its treaty obligations, but it was not a straightforward decision to take up arms. Different leaders of First Nations people held different positions on the usefulness of rebellion. Notable war leaders of the era, such as Big Bear

Big Bear, also known as (; – 17 January 1888), was a powerful and popular Cree chief who played many pivotal roles in Canadian history. He was appointed to chief of his band at the age of 40 upon the death of his father, Black Powder, u ...

and Poundmaker

Poundmaker ( – 4 July 1886), also known as ''pîhtokahânapiwiyin'' (), was a Plains Cree chief known as a peacemaker and defender of his people, the Poundmaker Cree Nation. His name denotes his special craft at leading buffalo into buf ...

, led their people to battle, albeit reluctantly; Wandering Spirit was very militant; others kept their people out of the conflict. This was one of few instances of armed conflict between the Canadian government (post-1867) and First Nations peoples.

Following the involvement of the Cree-Assiniboine alliance in the 1885 Battle of Cut Knife

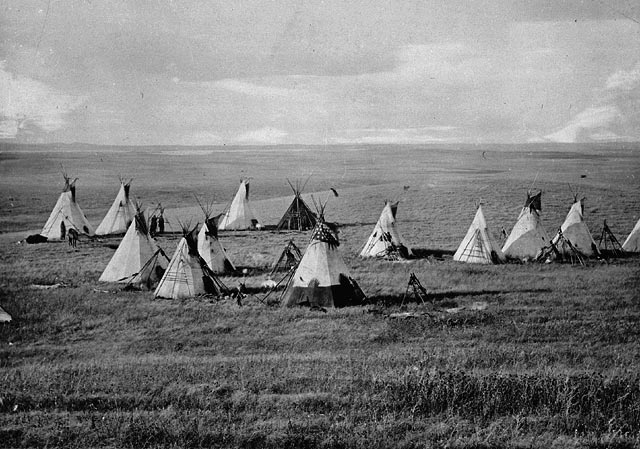

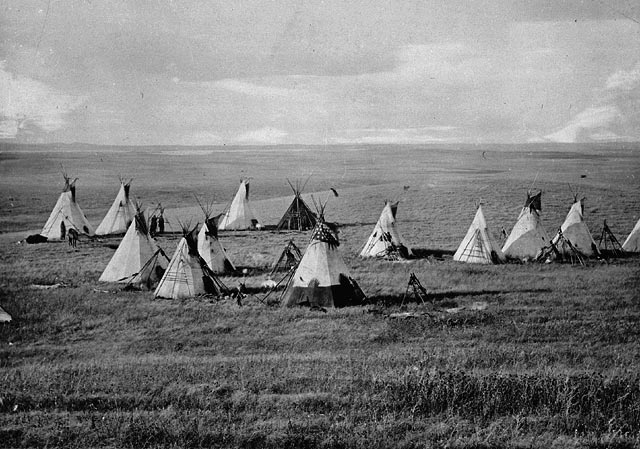

The Battle of Cut Knife, fought on May 2, 1885, during the North-West Rebellion, occurred when a flying column of North-West Mounted Police, Canadian militia, and Canadian regulars attacked a Cree and Assiniboine teepee settlement near Batt ...

, Canada used the new railway and telegraph connections to deploy Ontario and Quebec militias to the West, where they applied superior numbers, mobility, and firepower against the loose alliance of Cree, Assiniboine, and Métis. The Métis were defeated at Batoche

Batoche, which lies between Prince Albert and Saskatoon in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, was the site of the historic Battle of Batoche during the North-West Rebellion of 1885. The battle resulted in the defeat of Louis Riel and his M ...

, leaving the Cree-Assiniboine without allies. Poundmaker's mixed Cree-Assiniboine war party surrendered. Three weeks later, Big Bear's band won a victory at Frenchman's Butte, but this was in vain. The last band holding out (Big Bear and Wandering Spirit's) was dispersed at Loon Lake on 3 June 1885. After the rebellion Big Bear and Poundmaker were briefly imprisoned; Wandering Spirit and six other natives were hanged. A few members of Big Bear's band and other Cree sought refuge in the United States. They were extradited back to Canada, but most soon returned to the US and settled on the Rocky Boy Indian Reservation

Rocky Boy's Indian Reservation (also known as Rocky Boy Reservation) is one of seven Native American reservations in the U.S. state of Montana. Established by an act of Congress on September 7, 1916, it was named after ''Ahsiniiwin'' ( Stone C ...

, where their descendants live to this day. Big Bear's son eventually returned to Canada and helped found a reservation at Hobbema.

The decline of the buffalo, the treaties it signed with the Queen, and its fighters' defeat in the First Nations portion of the North-West Rebellion heralded, and contributed, to the Iron Confederacy's growing impotence as an economic, social and sovereign unit.

References

Sources

* {{Fur trade regions First Nations history in Canada 18th-century military alliances Fur trade Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains 19th-century military alliances History of Western Canada Assiniboine Cree Saulteaux Nakoda (Stoney) Former confederations Plains tribes Tribal Confederacies of indigenous peoples of North America