Irish Language In Britain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The

/ref> and those emigrants came in the 19th century from areas where Irish was already in retreat. An interest in the language has persisted among a minority in the diaspora countries, and even in countries where there was never a significant Irish presence. This has been shown in the founding of language classes (including some at tertiary level), in the use of the Internet, and in contributions to journalism and literature.

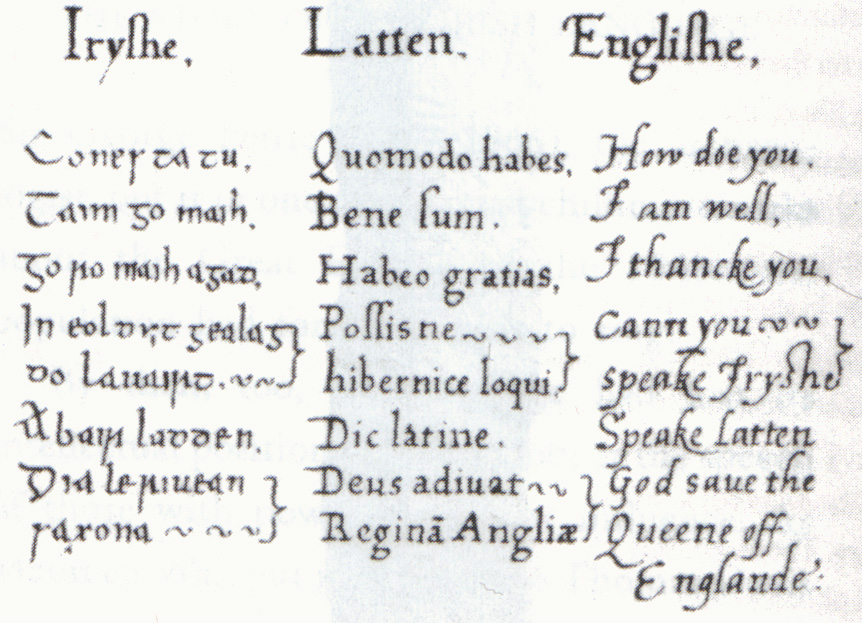

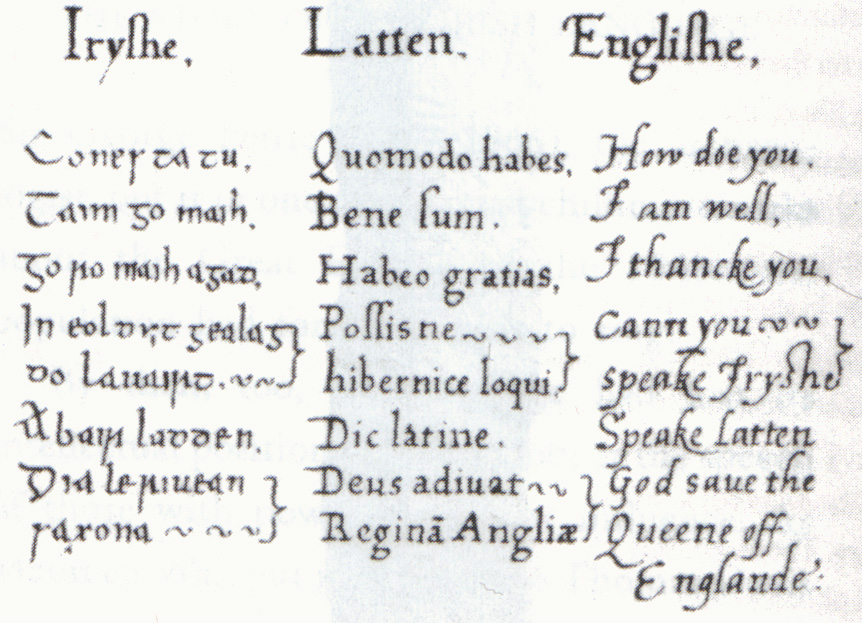

Irish speakers of all social classes were to be found in early modern Britain. Irish beggars were common in 16th century England, and from the late 16th century many unskilled Irish labourers settled in Liverpool, Bristol and London. Aristocratic Irish speakers included the Nugent brothers, members of Ireland's "Old English" community: Christopher Nugent, 9th Baron Delvin, who wrote an Irish-language primer for Elizabeth I, and William Nugent, an Irish language poet who is known to have been at Oxford in 1571. Shakespeare's plays contain one line in Irish, " Caleno custore me" in Act IV Scene 4 of

Irish speakers of all social classes were to be found in early modern Britain. Irish beggars were common in 16th century England, and from the late 16th century many unskilled Irish labourers settled in Liverpool, Bristol and London. Aristocratic Irish speakers included the Nugent brothers, members of Ireland's "Old English" community: Christopher Nugent, 9th Baron Delvin, who wrote an Irish-language primer for Elizabeth I, and William Nugent, an Irish language poet who is known to have been at Oxford in 1571. Shakespeare's plays contain one line in Irish, " Caleno custore me" in Act IV Scene 4 of

Irish immigrants were a notable element of London life from the early seventeenth century. They engaged in seasonal labour and street selling, and became common around

Irish immigrants were a notable element of London life from the early seventeenth century. They engaged in seasonal labour and street selling, and became common around

Diarmuid na Bolgaí Ó Sé

(c.1755–1846), Máire Bhuidhe Ní Laoghaire (1774-c.1848), and

by Sinéad Ní Mheallaigh, ''The Irish Times'', March 16, 2016. Sinéad Ní Mheallaigh further wrote, "An important part of my role here in Newfoundland is organising Irish language events, both in the university and the community. We held an Irish language film festival on four consecutive Mondays throughout November. Each evening consisted of a short film, and a

The Irish language reached Australia in 1788, along with English. Irish, when used by convicts in the early colonial period, was seen as a language of covert opposition, and was therefore viewed with suspicion by colonial authorities.

The Irish constituted a larger proportion of the European population than in any other British colony, and there has been debate about the extent to which Irish was used in Australia. The historian

The Irish language reached Australia in 1788, along with English. Irish, when used by convicts in the early colonial period, was seen as a language of covert opposition, and was therefore viewed with suspicion by colonial authorities.

The Irish constituted a larger proportion of the European population than in any other British colony, and there has been debate about the extent to which Irish was used in Australia. The historian

Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

originated in Ireland and has historically been the dominant language of the Irish people. They took it with them to a number of other countries, and in Scotland and the Isle of Man it gave rise to Scottish Gaelic and Manx

Manx (; formerly sometimes spelled Manks) is an adjective (and derived noun) describing things or people related to the Isle of Man:

* Manx people

**Manx surnames

* Isle of Man

It may also refer to:

Languages

* Manx language, also known as Manx ...

, respectively.

In the late 19th century, English became widespread in Ireland, but Irish-speakers had already shown their ability to deal with modern political and social changes through their own language at a time when emigration was strongest. Irish was the language that a large number of emigrants took with them from the 17th century (when large-scale emigration, forced or otherwise, became noticeable) to the 19th century, when emigration reached new levels.

The Irish diaspora mainly settled in English-speaking countries, chiefly Britain and North America. In some instances the Irish language was retained for several generations. Argentina was the only non-English-speaking country to which the Irish went in large numbers,Viva Irlanda! Exploring the Irish in Argentina/ref> and those emigrants came in the 19th century from areas where Irish was already in retreat. An interest in the language has persisted among a minority in the diaspora countries, and even in countries where there was never a significant Irish presence. This has been shown in the founding of language classes (including some at tertiary level), in the use of the Internet, and in contributions to journalism and literature.

Britain

Irish speakers of all social classes were to be found in early modern Britain. Irish beggars were common in 16th century England, and from the late 16th century many unskilled Irish labourers settled in Liverpool, Bristol and London. Aristocratic Irish speakers included the Nugent brothers, members of Ireland's "Old English" community: Christopher Nugent, 9th Baron Delvin, who wrote an Irish-language primer for Elizabeth I, and William Nugent, an Irish language poet who is known to have been at Oxford in 1571. Shakespeare's plays contain one line in Irish, " Caleno custore me" in Act IV Scene 4 of

Irish speakers of all social classes were to be found in early modern Britain. Irish beggars were common in 16th century England, and from the late 16th century many unskilled Irish labourers settled in Liverpool, Bristol and London. Aristocratic Irish speakers included the Nugent brothers, members of Ireland's "Old English" community: Christopher Nugent, 9th Baron Delvin, who wrote an Irish-language primer for Elizabeth I, and William Nugent, an Irish language poet who is known to have been at Oxford in 1571. Shakespeare's plays contain one line in Irish, " Caleno custore me" in Act IV Scene 4 of Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (c. 1173–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (121 ...

. This was the title of a popular Sean nos song, ''Cailín Óg a Stór

Cailín Óg a Stór (Irish for "O Darling Young Girl") is a traditional Irish melody, originally accepted for publication in March 1582. It may be the source of Pistol's cryptic line in Henry V, '' Caleno custure me''.

It is part of a broadside co ...

'' ("I'm a young girl from the River Suir").

Irish speakers were among the Cavaliers

The term Cavalier () was first used by Roundheads as a term of abuse for the wealthier royalist supporters of King Charles I and his son Charles II of England during the English Civil War, the Interregnum, and the Restoration (1642 – ). It ...

brought over from Ireland during the English Civil War. Language and cultural differences were partly responsible for the great hostility they encountered in England. Among them were troops commanded by Murrough O'Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin

Murrough MacDermod O'Brien, 1st Earl of Inchiquin (September 1614 – 9 September 1673), was an Irish nobleman and soldier, who came from one of the most powerful families in Munster. Known as "''Murchadh na dTóiteán''" ("Murrough the Burner" ...

and who followed him when he later sided with Parliament.

Large-scale Irish immigration, including many Irish speakers, began with the building of canals from the 1780s and of railways in the nineteenth century. More Irish settled in industrial towns in Lancashire in the late eighteenth century than in any other county. Many Irish were attracted to Birmingham in the mid-1820s by rapid industrial expansion. The city had large households of Irish speakers, often from the same parts of Mayo, Roscommon, Galway and Sligo

Sligo ( ; ga, Sligeach , meaning 'abounding in shells') is a coastal seaport and the county town of County Sligo, Ireland, within the western province of Connacht. With a population of approximately 20,000 in 2016, it is the List of urban areas ...

. In Manchester a sixth of the family heads were Irish by 1835. By the 1830s Irish speakers were to be found in Manchester, Glasgow and the larger towns of South Wales

South Wales ( cy, De Cymru) is a loosely defined region of Wales bordered by England to the east and mid Wales to the north. Generally considered to include the historic counties of Glamorgan and Monmouthshire, south Wales extends westwards ...

. Friedrich Engels heard Irish being spoken in the most crowded areas of Manchester in 1842. Irish speakers from Roscommon, Galway and Mayo were also to be found in Stafford

Stafford () is a market town and the county town of Staffordshire, in the West Midlands region of England. It lies about north of Wolverhampton, south of Stoke-on-Trent and northwest of Birmingham. The town had a population of 70,145 in t ...

from the 1830s.Camp, pp. 8–10

The Great Famine of the later 1840s brought an influx of Irish speakers to England, Wales and Scotland. Many arrived from such counties as Mayo, Cork

Cork or CORK may refer to:

Materials

* Cork (material), an impermeable buoyant plant product

** Cork (plug), a cylindrical or conical object used to seal a container

***Wine cork

Places Ireland

* Cork (city)

** Metropolitan Cork, also known as G ...

, Waterford and Limerick to Liverpool, Bristol, and the towns of South Wales and Lancashire, and often moved on to London. Navvies found work on the South Wales Railway. There are reports of Irish-speaking communities in some quarters of Liverpool in the Famine years (1845–52). Irish speakers from Munster were common among London immigrants, with many women speaking little or no English. Around 100,000 Irish had arrived in London by 1851. The Irish Nationalist politician and lawyer A.M. Sullivan described an 1856 visit to the industrial "Black Country" of the West Midlands where "in very many of the houses not one of the women could speak English, and I doubt that in a single house the Irish was not the prevalent language".

The Gaelic Revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

in Ireland at the turn of the 20th century led to formation of branches of the Gaelic League abroad, including British cities. There were three branches of the Gaelic League in Glasgow by 1902 and a branch was also founded in Manchester.

In the aftermath of the Second World War there were a large number of Irish working in Britain in the construction industry, rebuilding the cities destroyed by Luftwaffe bombs, and as nurses. Many of them, both in provincial towns and in London, were from the Gaeltachtaí, and Irish was commonly heard on building sites, in Irish pubs, and in dance halls.

While rebuilding the bombed damaged cities of postwar Britain, Dónall Mac Amhlaigh

Dónall Peadar Mac Amhlaigh (10 December 1926 – 27 January 1989) was an Irish writer active during the 20th century. A native of County Galway, he is best known for his Irish-language works about life as a labourer in the post-Second Wo ...

, a native of Barna

Barna (Bearna in Irish) is a coastal village on the R336 regional road in Connemara, County Galway, Ireland. It has become a satellite village of Galway city. The village is Irish speaking and is therefore a constituent part of the regions ...

, County Galway, kept an Irish-language diary, which he published as, ''Dialann Deoraí''. It was translated into English by Valentine Iremonger and published in 1964 under the title ''An Irish Navvy: The Diary of an Exile''.

London

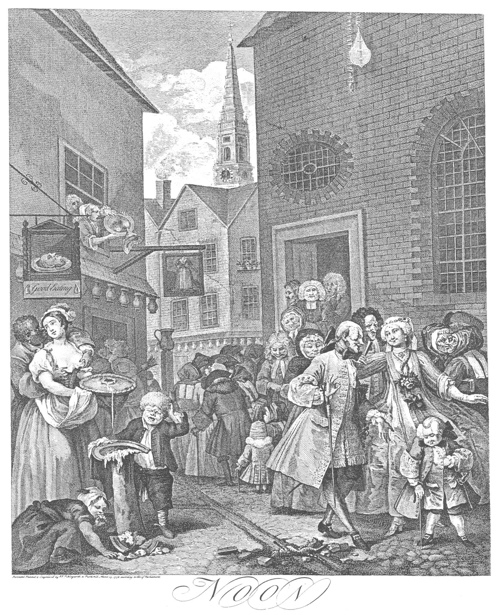

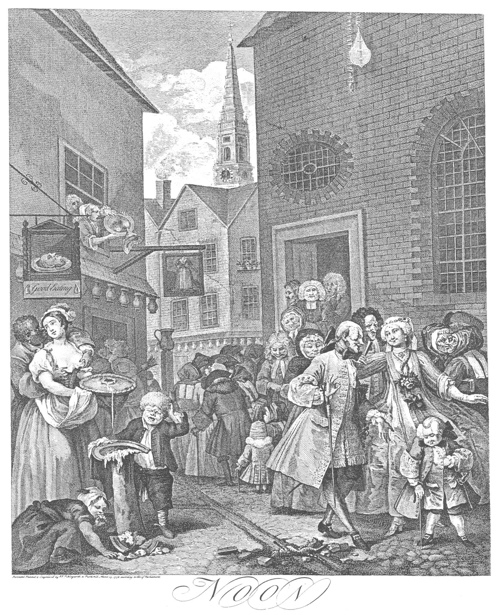

Irish immigrants were a notable element of London life from the early seventeenth century. They engaged in seasonal labour and street selling, and became common around

Irish immigrants were a notable element of London life from the early seventeenth century. They engaged in seasonal labour and street selling, and became common around St Giles in the Fields

St Giles in the Fields is the Anglican parish church of the St Giles district of London. It stands within the London Borough of Camden and belongs to the Diocese of London. The church, named for St Giles the Hermit, began as a monastery and ...

during the eighteenth century, being prominent among the London poor. Many of them were discharged soldiers. The Old Bailey

The Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, commonly referred to as the Old Bailey after the street on which it stands, is a criminal court building in central London, one of several that house the Crown Court of England and Wales. The s ...

trial records give a glimpse of the use of Irish in London backstreets, including an instance where a court interpreter was required (1768).

The first Irish colony was in St Giles in the Fields and Seven Dials. By the early nineteenth century Irish communities existed in Whitechapel, Saffron Hill, Poplar and Southwark

Southwark ( ) is a district of Central London situated on the south bank of the River Thames, forming the north-western part of the wider modern London Borough of Southwark. The district, which is the oldest part of South London, developed ...

, and especially in Marylebone. Typical occupations were hawking and costermongering. Henry Mayhew estimated in the 1850s that around 10,000 Irish men and women were so employed. The writer and linguist George Borrow gives an account (1851) of his father venturing into the Irish-speaking slums of London in the early years of the nineteenth century.

The use of the language was affected by a decline in the number of immigrants. By the middle of the nineteenth century the Irish-born numbered around 109,000 individuals (4.5% of Londoners). By 1861 their number had fallen to 107,000, in 1871 to 91,000, and in 1901 to 60,000.

The Gaelic League was active in London as elsewhere. The London branch had a number of notable London Irish figures as members, and it was a pioneer in the publication of Irish-language material.

Irish language in contemporary Britain

The current estimate of fluent Irish speakers permanently resident in Britain is 9,000. The Gaelic League retains a presence in Britain (the current Glasgow branch was founded in 1895), and the Irish-language organization Coláiste na nGael and its allies run language classes and other events all over Britain. The areas concerned include London, Essex, Leicestershire and Somerset. There is an active Irish language scene in Manchester with two groups, Conradh na Gaeilge (Manchester branch) and the Manchester Irish Language Group, who have organised an annual arts festival since 2007. The British Association for Irish Studies (established 1985) aims to support Irish cultural activities and the study of Ireland in Britain. This includes promotion of the Irish language.North America

Irish people brought the language with them to North America as early as the 17th century (when it is first mentioned). In the 18th century it had many speakers in Pennsylvania. Immigration from Irish-speaking counties to America was strong throughout the 19th century, particularly after the Great Famine of 1840s, and many manuscripts in Irish came with the immigrants. TheIrish language in Newfoundland

The Irish language was once widely spoken on the island of Newfoundland before largely disappearing there by the early 20th century.

was introduced in the late 17th century and was widely spoken there until the early 20th century. Local place names in the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

include Newfoundland (''Talamh an Éisc'', ''Land of the Fish'') and St. John's (''Baile Sheáin'') Ballyhack (''Baile Hac''), Cappahayden

Renews–Cappahayden is a small fishing town on the southern shore of Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland, south of St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, St. John's.

The town was incorporated in the mid-1960s by amalgamating the formerly inde ...

(''Ceapach Éidín''), Kilbride and St. Bride's (''Cill Bhríde''), Duntara, Port Kirwan

Port Kirwan is a small incorporated fishing community located on the southern shore of the Avalon Peninsula, Newfoundland, Canada.

Demographics

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Port Kirwan had a population of ...

and Skibbereen (''Scibirín'').

In the oral tradition of County Waterford

County Waterford ( ga, Contae Phort Láirge) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Munster and is part of the South-East Region, Ireland, South-East Region. It is named ...

, the poet Donnchadh Ruadh Mac Conmara

Donnchadh Ruadh Mac Conmara (1715–1810) was an Irish schoolmaster of a hedge school, Jacobite propagandist, anti-hero in Irish folklore, and composer of poetry in both Munster Irish and in the Irish language outside Ireland.

Life

He was born ...

, a hedge school teacher and notorious rake

Rake may refer to:

* Rake (stock character), a man habituated to immoral conduct

* Rake (theatre), the artificial slope of a theatre stage

Science and technology

* Rake receiver, a radio receiver

* Rake (geology), the angle between a feature on a ...

from the district of Sliabh gCua

Sliabh gCua (formerly anglicized as 'Slieve Gua' or 'Slieve Goe')Tempan, Paul"Sliabh in Irish Place-Names". Queen's University Belfast, 2008. p.29 is a traditional district of west County Waterford, Ireland, between Clonmel and Dungarvan, covering ...

, is said to have sailed for Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

around 1743, allegedly to escape the wrath of a man whose daughter the poet had impregnated.

For a long time, it was doubted whether the poet ever made the trip. During the 21st century, however, linguists discovered that several of Donnchadh Ruadh's poems in the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

Gaelicize many words and terms known to be unique to Newfoundland English. For this reason, Donnchadh Ruadh's poems are considered the earliest solid evidence of the Irish language in Newfoundland

The Irish language was once widely spoken on the island of Newfoundland before largely disappearing there by the early 20th century.

.

In Philadelphia, County Galway-born lexicographer Maitias Ó Conbhuí spent thirty years attempting to compile a dictionary of the Irish language, which remained unfinished upon his death in 1842.

The Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

poet and monoglot

Monoglottism (Greek μόνος ''monos'', "alone, solitary", + γλῶττα , "tongue, language") or, more commonly, monolingualism or unilingualism, is the condition of being able to speak only a single language, as opposed to multilingualism. ...

speaker Pádraig Phiarais Cúndún

Pádraig Phiarais Cúndún (1777–1856) was an Irish people, Irish immigrant to the United States, where he continued composing Irish poetry, poetry in Munster Irish and contributed to literature in the Irish language outside Ireland.

Life

Cún ...

(1777–1856), a native of Ballymacoda

Ballymacoda () is a small village in County Cork, Ireland. As of the 2016 census, the village had a population of 185 people.

Located in East Cork, the village is home to one pub, a post office, and Saint Peter in Chains Roman Catholic church. T ...

, County Cork, emigrated to America around 1826 and settled with his family on a homestead near Deerfield, New York

Deerfield is a town in Oneida County, New York, United States. The population was 4,273 at the 2010 census.

The Town of Deerfield is on the eastern border of the county and northeast of the City of Utica.

History

Deerfield was formed from t ...

. There were many other Irish-speakers in and around Deerfield and Cúndún never had to learn English. He died in Deerfield in 1857Edited by Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle (2020), ''North American Gaels: Speech, Song, and Story in the Diaspora'', McGill-Queen's University Press. Pages 108–136. and lies buried at St. Agnes Cemetery in Utica, New York. Cúndún's many works of American poetry composed in Munster Irish have survived through the letters he wrote to his relatives and former neighbors in Ballymacoda and due to the fact that his son, "Mr. Pierce Condon of South Brooklyn", arranged for two of his father's poems to be published by the ''Irish-American'' in 1858. The first collection of Cúndún's poetry was edited by Risteard Ó Foghludha and published in 1932. Kenneth E. Nilsen

Kenneth is an English given name and surname. The name is an Anglicised form of two entirely different Gaelic personal names: ''Cainnech'' and '' Cináed''. The modern Gaelic form of ''Cainnech'' is ''Coinneach''; the name was derived from a byna ...

, an American linguist who specialized in Celtic languages in North America, referred to Cúndún as, "the most notable Irish monoglot speaker to arrive in this country", and added that, "his letters and poems, written in upstate New York to his neighbours in Ballymacoda

Ballymacoda () is a small village in County Cork, Ireland. As of the 2016 census, the village had a population of 185 people.

Located in East Cork, the village is home to one pub, a post office, and Saint Peter in Chains Roman Catholic church. T ...

, County Cork, represent the most important body of Pre-Famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food, caused by several factors including war, natural disasters, crop failure, Demographic trap, population imbalance, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. Th ...

writing in Irish from the United States."

In 1851, the ''Irish-American'', a weekly newspaper published in New York City, published what is believed to be, "the first original composition in Irish to be published in the United States". It was a three stanza poem describing an Irish pub on Duane Street in what is now the Tribeca neighborhood of Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan (also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York) is the southernmost part of Manhattan, the central borough for business, culture, and government in New York City, which is the most populated city in the United States with ...

. The poem's style is that of the Irish-language poetry of the 18th and early 19th centuries, the only difference is that it describes a pub located in the Irish diaspora

The Irish diaspora ( ga, Diaspóra na nGael) refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner and Meeder, The ...

.

In 1857, the ''Irish-American'' added a regular column in the Irish-language. The first five original poems which were published in the column were submitted by Irish poets living in present-day Ontario.Edited by Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle (2020), ''North American Gaels: Speech, Song, and Story in the Diaspora'', McGill-Queen's University Press. Page 10-11.

During the 1860s in South Boston, Massachusetts

South Boston is a densely populated neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, located south and east of the Fort Point Channel and abutting Dorchester Bay. South Boston, colloquially known as Southie, has undergone several demographic transformati ...

, Bríd Ní Mháille, an immigrant from the village of Trá Bhán, on the island of Garmna

Gorumna () is an island on the west coast of Ireland, forming part of County Galway.

Geography

Gorumna Island is linked with the mainland through the Béal an Daingin Bridge.

Gorumna properly consists of three individual islands in close pr ...

, County Galway, composed the Irish-language '' caoineadh'' '' Amhrán na Trá Báine'', which is about the drowning of her three brothers, whose '' currach'' was rammed and sunk while they were out at sea. Ní Mháille's lament for her brothers was first performed at a ceilidh in South Boston before being brought back to her native district in Connemara, where it is considered one of the ''amhráin mhóra'' ("Big Songs") and it remains a very popular song among performers and fans of Irish traditional music.

Beginning in the 1870s, the more politicized Irish-Americans began taking interest in their ancestral language. Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

organizations like the Philo-Celtic Society

The Philo-Celtic Society (Irish: Cumann Carad na Gaeilge) is a North American society founded as part of the Gaelic revival in 1873. Its aims are the promotion of the Irish language as a living tongue in America and throughout the world, and the r ...

began springing up throughout the United States. Irish-American newspapers and magazines also began adding columns in the Irish-language. These same publications circulated widely among Irish-Canadians. Furthermore, the sixth President of St. Bonaventure's College

St. Bonaventure's College (commonly called St. Bon's) is an independent kindergarten to grade 12 Catholic School in St. John's, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. It is located in the St. John's Ecclesiastical District, adjacent to the Roman Cat ...

in St John's, Newfoundland

St. John's is the capital and largest city of the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador, located on the eastern tip of the Avalon Peninsula on the island of Newfoundland.

The city spans and is the easternmost city in North America ...

was not only a member of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language, but also taught Irish-language classes there during the 1870s. Although the subject still remains to be explored, Kenneth E. Nilsen

Kenneth is an English given name and surname. The name is an Anglicised form of two entirely different Gaelic personal names: ''Cainnech'' and '' Cináed''. The modern Gaelic form of ''Cainnech'' is ''Coinneach''; the name was derived from a byna ...

, an American linguist specializing in the Celtic languages, argued in a posthumously published essay that "closer inspection would likely reveal a Canadian counterpart to the American language revival movement."

In 1881, "", the first newspaper anywhere which was largely in Irish, was founded as part of the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

by the Philo-Celtic Society

The Philo-Celtic Society (Irish: Cumann Carad na Gaeilge) is a North American society founded as part of the Gaelic revival in 1873. Its aims are the promotion of the Irish language as a living tongue in America and throughout the world, and the r ...

chapter in Brooklyn, New York. It continued appearing until 1904 and it's published contributions included many works of Irish folklore collected in both Ireland and the United States. According to Tomás Ó hÍde, however, old issues of ''An Gaodhal'', while a priceless resource, are very difficult for modern readers of Irish to understand due to the publishers' use of Gaelic type and an obsolete orthography.''An Gaodhal'', however, now has an on-line successor in ''An Gael

''An Gael'' is a quarterly literary magazine in the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European l ...

'', which is edited by American-born Irish-language essayist and poet Séamas Ó Neachtain

Séamas Ó Neachtain (Jim Norton) is an Irish-American writer who has published journalism, poetry and fiction in the Irish language.

Ó Neachtain is an American of Irish descent whose family have been in America for over five generations. He fir ...

.

Many other Irish immigrant newspapers in the English language in the 19th and 20th century similarly added Irish language columns.

The Philo-Celtic Society

The Philo-Celtic Society (Irish: Cumann Carad na Gaeilge) is a North American society founded as part of the Gaelic revival in 1873. Its aims are the promotion of the Irish language as a living tongue in America and throughout the world, and the r ...

chapter in Boston published the bilingual newspaper, ''The Irish Echo'', from 1886 to 1894. Every issue bore an Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

quote as the tagline, "No people will look forward to posterity who do not look backward to their ancestors." Every issue contained many works of Irish language literature and poetry submitted by Irish-Americans in and around Boston. Some were composed locally, but many others were transcribed and submitted from centuries-old heirloom Irish-language manuscripts which had been brought to the Boston area by recent immigrants.

Also during the Gaelic revival, a regular Irish-language column titled ''Ón dhomhan diar'', generally about the hardships faced by immigrants to the United States, was contributed to Patrick Pearse's '' An Claidheamh Soluis'' by Pádraig Ó hÉigeartaigh

Pádraig Ó hÉigeartaigh (1871–1936) was an Irish poet.

Life

Early life

A native of Uíbh Ráthach, County Kerry, Ó hÉigeartaigh emigrated with his father, Patrick, a laborer, and his mother, Mary Lynch, to the United States when he was ...

(1871–1936). Ó hÉigeartaigh, an immigrant from Uíbh Ráthach

The Iveragh Peninsula () is located in County Kerry in Ireland. It is the largest peninsula in southwestern Ireland. A mountain range, the MacGillycuddy's Reeks, lies in the centre of the peninsula. Carrauntoohil, its highest mountain, is a ...

, County Kerry, worked in the clothing business and lived with his family in Springfield, Massachusetts

Springfield is a city in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, United States, and the seat of Hampden County. Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the ...

. Ó hÉigeartaigh also wrote poetry for the same publication in Munster Irish. His poem ''Ochón! a Dhonncha'' ("My Sorrow, Dhonncha!"), a lament for the drowning of his six-year-old son on 22 August 1905, appeared in Pearse's magazine in 1906. Although the early authors of the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

preferred to write in the literary language once common to both Ireland and Scotland and felt scorn for the oral poetry

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

Background

Oral poetry is ...

of the Gaeltachtaí, Ó hÉigeartaigh drew upon that very tradition to express his grief and proved that it could still be used effectively by a 20th-century poet. Ó hÉigeartaigh's lament for his son has a permanent place in the literary canon of Irish poetry

Irish poetry is poetry written by poets from Ireland. It is mainly written in Irish language, Irish and English, though some is in Scottish Gaelic literature, Scottish Gaelic and some in Hiberno-Latin. The complex interplay between the two mai ...

in the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

and has been translated into English by both Patrick Pearse and Thomas Kinsella.

One of the most talented 20th-century Irish-language poets and folklore collectors in the New World was Seán Gaelach Ó Súilleabháin (Sean "Irish" O'Sullivan) (1882–1957). Ó Súilleabháin, whom literary scholar Ciara Ryan has dubbed "Butte's Irish Bard", was born into the Irish-speaking fishing community upon Inishfarnard

Inishfarnard () meaning ''Island of the tall fern'' is a small island and a townland off Kilcatherine Point, in County Cork, Ireland.

Geography

Near the northern tip of the island there are pleasant cliffs; the best landing place for boats (n ...

, a now-uninhabited island off the Beara Peninsula in West County Cork. In 1905, Ó Súilleabháin sailed aboard the ocean liner ''RMS Lucania

RMS ''Lucania'' was a British ocean liner owned by the Cunard Line, Cunard Steamship Line Shipping Company, built by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company of Govan, Scotland, and launched on Thursday, 2 February 1893.

Identical in dime ...

'' from Queenstown to Ellis Island and settled in the heavily Irish-American mining community in Butte, Montana

Butte ( ) is a consolidated city-county and the county seat of Silver Bow County, Montana, United States. In 1977, the city and county governments consolidated to form the sole entity of Butte-Silver Bow. The city covers , and, according to the ...

. Following his arrival in America, Ó Súilleabháin never returned to Ireland. In the State of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbia ...

, however, he learned through classes taught by the Butte chapter of Conradh na Gaeilge to read and write in his native language for the first time. Ó Súilleabháin also married and raised a family. Seán Ó Súilleabháin remained a very influential figure in Butte's Irish-American literary, Irish republican

Irish republicanism ( ga, poblachtánachas Éireannach) is the political movement for the unity and independence of Ireland under a republic. Irish republicans view British rule in any part of Ireland as inherently illegitimate.

The develop ...

, and Pro- Fianna Fáil circles for the rest of his life.

In the O'Sullivan Collection in the Butte-Silver Bow Archives, Ó Súilleabháin is also revealed to have transcribed many folksongs and oral poetry

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

Background

Oral poetry is ...

from his childhood memories of Inishfarnard

Inishfarnard () meaning ''Island of the tall fern'' is a small island and a townland off Kilcatherine Point, in County Cork, Ireland.

Geography

Near the northern tip of the island there are pleasant cliffs; the best landing place for boats (n ...

and the Beara Peninsula. Seán Gaelach Ó Súilleabháin was also a highly talented poet in his own right who drew inspiration froDiarmuid na Bolgaí Ó Sé

(c.1755–1846), Máire Bhuidhe Ní Laoghaire (1774-c.1848), and

Pádraig Phiarais Cúndún

Pádraig Phiarais Cúndún (1777–1856) was an Irish people, Irish immigrant to the United States, where he continued composing Irish poetry, poetry in Munster Irish and contributed to literature in the Irish language outside Ireland.

Life

Cún ...

(1777–1857), who had previously adapted the tradition of Aisling

The aisling (, , approximately ), or vision poem, is a poetic genre that developed during the late 17th and 18th centuries in Irish language Irish poetry, poetry. The word may have a number of variations in pronunciation, but the ''is'' of t ...

, or "Vision poetry", from the Jacobite Risings of the 18th century to more recent struggles by the Irish people. For this reason, Ó Súilleabháin's surviving Aisling poems; such as ''Cois na Tuinne'' ("Beside the Wave"), ''Bánta Mín Éirinn Glas Óg'' ("The Lush Green Plains of Ireland"), and the highly popular 1919 poem ''Dáil Éireann''; adapted the same tradition to the events of the Easter Rising

The Easter Rising ( ga, Éirí Amach na Cásca), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the a ...

of 1916 and the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence () or Anglo-Irish War was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and British forces: the British Army, along with the quasi-mil ...

(1919–1921).Edited by Natasha Sumner and Aidan Doyle (2020), ''North American Gaels: Speech, Song, and Story in the Diaspora'', McGill-Queen's University Press. Pages 238–240.

According to Ó Súilleabháin scholar Ciara Ryan, "Like many ''aisling

The aisling (, , approximately ), or vision poem, is a poetic genre that developed during the late 17th and 18th centuries in Irish language Irish poetry, poetry. The word may have a number of variations in pronunciation, but the ''is'' of t ...

í'' of the eighteenth century, Seán's work is replete with historical and literary reference] to Irish and Classical mythology, Classical literary characters."

According to the poet's son, Fr. John Patrick Sarsfield O'Sullivan ("Fr. Sars") of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Helena, his father read the ''Aisling'' poem ''Dáil Éireann'' aloud during Éamon de Valera's 1919 visit to Butte. The future Taoiseach of the Irish Republic was reportedly so impressed that he urged Ó Súilleabháin to submit the poem to ''Féile Craobh Uí Gramnaigh'' ("O'Growney's Irish Language Competition") in San Francisco. Ó Súilleabháin took de Valera's advice and won both first prize and the gold medal for the poem.

Seán Gaelach Ó Súilleabháin's papers in the Butte-Silver Bow Archives also include many transcriptions of the verse of other local Irish-language poets. One example is the poem ''Amhrán na Mianach'' ("The Song of the Mining"), which, "lays bare the hardships of a miner's life", was composed in Butte by Séamus Feiritéar (1897–1919), his brother Mícheál, and their childhood friend Seán Ruiséal. Another local Irish-language poem transcribed in Ó Súilleabháin's papers was composed in 1910 by Séamus Ó Muircheartaigh, a Butte mine worker from Corca Dhuibhne, County Kerry, who was nicknamed ''An Spailpín'' ("The Farmhand"). The poem, which has eight stanzas and is titled, ''Beir mo Bheannacht leat, a Nellie'' ("Bring My Blessings with You, Nellie") recalls the poet's happy childhood in Corca Dhuibhne and was composed while Ó Muircheartaigh's wife, Nellie, and their son, Oisín, were on an extended visit there.

At the end of his life, Micí Mac Gabhann

Micí Mac Gabhann (22 November 1865 – 29 November 1948) was a seanchaí and memoirist from the County Donegal Gaeltacht. He is best known for his posthumously published emigration memoir ''Rotha Mór an tSaoil'' (1959). It was dictated to his ...

(1865–1948), a native Irish-speaker from Cloughaneely, County Donegal, dictated his life experiences in Scotland, the Wild West, Alaska, and the Yukon to his folklorist

Folklore studies, less often known as folkloristics, and occasionally tradition studies or folk life studies in the United Kingdom, is the branch of anthropology devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currenc ...

son-in-law, Seán Ó hEochaidh

Seán Ó hEochaidh (9 February 1913 – 18 January 2002) was an Irish folklorist.

Biography

A native of Teelin, County Donegal, Ó hEochaidh worked as a fisherman in his youth. Despite a basic education, from an early age he made a written rec ...

, who published the posthumously in the 1958 emigration memoir, ''Rotha Mór an tSaoil'' (" The Great Wheel of Life"). An English translation by Valentine Iremonger appeared in 1962 as, ''The Hard Road to Klondike''.

The title of the English version refers to the Klondike gold rush, ''Ruathar an Óir'', at the end of the 19th century, and the hardships Irish-speakers endured working in the mines of ''Tír an Airgid'' ("The Land of Silver", or Montana) and ''Tír an Óir'' ("The Land of Gold", or the Yukon). After making a fortune mining gold from his claim in the Yukon, Mac Gabhann returned to Cloughaneely, married, and bought the estate of a penniless Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

landlord, and raised a family there.

Irish retains some cultural importance in the northeast United States. According to the 2000 Census, 25,661 people in the U.S. spoke Irish in the home. The 2005 Census reported 18,815. The 2009-13 American Community Survey reported 20,590 speakers

Furthermore, the tradition of Irish language literature and journalism in American newspapers continued with the weekly column of Barra Ó Donnabháin

Barra Ó Donnabháin (1941–2003) was a columnist with the New York Irish Echo newspaper. His weekly article in Irish entitled ''Macalla'' spoke of the Irish language and its people in Ireland and the United States. A selection of his articles we ...

in New York City's ''Irish Echo

''The Irish Echo'' is a weekly Irish Americans, Irish-American newspaper based in Manhattan in the United States. In 2007, Máirtín Ó Muilleoir, Irish businessman and publisher of the ''Andersonstown News'', purchased the paper.

Founded in 1 ...

''.

Derry

Derry, officially Londonderry (), is the second-largest city in Northern Ireland and the fifth-largest city on the island of Ireland. The name ''Derry'' is an anglicisation of the Old Irish name (modern Irish: ) meaning 'oak grove'. The ...

-born Pádraig Ó Siadhail

Pádraig Ó Siadhail was born in Derry, Northern Ireland, in 1957, and now lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. He is a scholar and writer and has published prolifically in the Irish language.

Among his works are the murder mystery ''Peaca an ...

(b. 1968) has been living in Halifax, Nova Scotia, since 1987. In this period, he has published ten works in Irish, including a collection of short stories and two novels.

In 2007 a number of Canadian speakers founded the first officially designated "Gaeltacht" outside Ireland in an area near Kingston, Ontario (see main article Permanent North American Gaeltacht

The North American Gaeltacht () is a gathering place for Irish language, Irish speakers in the community of Tamworth, Ontario, Tamworth, Ontario, in Canada. The nearest main township is Erinsville, Ontario. Unlike in Ireland, where the term "" r ...

). Despite its designation, the area has no permanent Irish-speaking inhabitants. The site (named ''Gaeltacht Bhaile na hÉireann'') is located in Tamworth, Ontario, and is to be a retreat centre for Irish-speaking Canadians and Americans.

University and college courses

The Irish government provides funding for suitably qualified Irish speakers to travel to Canada and the United States to teach the language at universities. This program has been coordinated by the Fulbright Commission in the United States and the Ireland Canada University Foundation in Canada. A number of North American universities have full-time lecturers in Modern Irish. These includeBoston College

Boston College (BC) is a private Jesuit research university in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. Founded in 1863, the university has more than 9,300 full-time undergraduates and nearly 5,000 graduate students. Although Boston College is classifie ...

, Harvard University, Lehman College

Lehman College is a public college in the Bronx borough of New York City. Founded in 1931 as the Bronx campus of Hunter College, the school became an independent college within CUNY in September 1967. The college is named after Herbert H. Lehma ...

-CUNY, New York University, Saint Mary's University in Halifax, the University of Pittsburgh, Concordia University in Montreal, Elms College

The College of Our Lady of the Elms, often called Elms College, is a Private college, private Catholic church, Roman Catholic in Chicopee, Massachusetts.

History

The Sisters of St. Joseph and the Diocese of Springfield co-founded Elms as a g ...

, Catholic University of America

The Catholic University of America (CUA) is a private Roman Catholic research university in Washington, D.C. It is a pontifical university of the Catholic Church in the United States and the only institution of higher education founded by U.S. ...

and most notably the University of Notre Dame. Two of these institutions offer undergraduate degrees with advanced Irish language coursework, the University of Notre Dame with a BA in Irish Language and Literature and Lehman College-CUNY with a BA in Comparative Literature, while the University of Pittsburgh offers an undergraduate Irish Minor. Irish language courses are also offered at St Michael's College in the University of Toronto, at Cape Breton University

, "Diligence Will Prevail"

, mottoeng = Perseverance Will Triumph

, established = 1951 as Xavier Junior College 1968 as NSEIT 1974 as College Of Cape Breton 1982 as University College of Cape Breton 2005 as Cape Breton ...

, and at Memorial University in Newfoundland.

In a 2016 article for '' The Irish Times'', Sinéad Ní Mheallaigh, who teaches Irish at Memorial University in St. John's, wrote, "There is a strong interest in the Irish language. Irish descendent and farmer Aloy O’Brien, who died in 2008 at the age of 93, taught himself Irish using the ''Buntús Cainte'' books and with help from his Irish-speaking grandmother. Aloy taught Irish in Memorial University for a number of years, and a group of his students still come together on Monday nights. One of his first students, Carla Furlong, invites the others to her house to speak Irish together as the “Aloy O’Brien Conradh na Gaeilge”’ group."Teaching Irish in Newfoundland, the most Irish place outside Irelandby Sinéad Ní Mheallaigh, ''The Irish Times'', March 16, 2016. Sinéad Ní Mheallaigh further wrote, "An important part of my role here in Newfoundland is organising Irish language events, both in the university and the community. We held an Irish language film festival on four consecutive Mondays throughout November. Each evening consisted of a short film, and a

TG4

TG4 ( ga, TG Ceathair, ) is an Irish free-to-air public service television network. The channel launched on 31 October 1996 and is available online and through its on demand service TG4 Player in Ireland and beyond.

TG4 was formerly known a ...

feature-length film, preceded by an Irish lesson. These events attracted people from all parts of society, not just those interested in Ireland and the language. The students took part in the international ''Conradh na Gaeilge'' events for ‘Gaeilge 24’ and we will have Gaelic sports

Gaelic games ( ga, Cluichí Gaelacha) are a set of sports played worldwide, though they are particularly popular in Ireland, where they originated. They include Gaelic football, hurling, Gaelic handball and rounders. Football and hurling, ...

and a huge Céilí mór later in March."

Australia

Patrick O'Farrell

Patrick James O'Farrell (17 September 1933 – 25 December 2003) was an historian known for his histories of Roman Catholicism in Australia, Irish history and Irish Australian history.

Early life and family

O'Farrell was born on 17 Septembe ...

argued that the language was soon discarded; other historians, including Dymphna Lonergan and Val Noone

Valentine Gabriel Noone (born 9 May 1940) is an Australian writer-editor, historian, social activist and academic. He is a recognised authority on Irish emigration to Australia, especially Victoria, since the time of the great Irish Famine (1845 ...

, have argued that its use was widespread among the first generation, with some transmission to the second and occasional evidence of literacy. Most Irish immigrants came from counties in the west and south-west where Irish was strong (e.g. County Clare and County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

). It has been argued that at least half the approximately 150,000 Irish emigrants to Victoria in the 19th century spoke Irish, helping to make Irish the most widely used European language in Australia after English.

English was essential to the Irish for their integration into public life. Irish, however, retained some cultural and symbolic importance, and the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

was reflected in Australia in the work of local students and scholars. The language was taught in several Catholic schools in Melbourne in the 1920s, and a bilingual magazine called ''An Gael'' was published. In the following years a small group of enthusiasts in the major cities continued to cultivate the language.

In the 1970s there was a more general renewal of interest, supported by both local and immigrant activists. The Irish National Association, with support from the Sydney branch of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge), ran free classes in Sydney from the 1960s through to 2007, when the language group became independent. In 1993 Máirtín Ó Dubhlaigh, a Sydney-based Irish speaker, founded the first Irish language summer school, Scoil Samhraidh na hAstráile. This brought together for the first time Irish speakers and teachers from all over the country. The language also attracted some wider public attention.

There is presently a network of Irish learners and users spread out across the country. The primary organised groups are the Irish Language Association of Australia (Cumann Gaeilge na hAstráile), Sydney Irish School and the Canberra Irish Language Association (Cumann Gaeilge Canberra). Multiple day courses are available twice a year in the states of Victoria and New South Wales. The association has won several prestigious prizes (the last in 2009 in a global competition run by Glór na nGael

Glór na nGael (; "voice of the Gaels") is an Irish-language organisation funded by Foras na Gaeilge which promotes Irish in three sectors: the family, community development, and business. It was established as a competition between community gro ...

and sponsored by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs).

The 2011 census indicated that 1,895 people used Irish as a household language in Australia. This marks an increase from the 2001 census, which gave a figure of 828. The census does not count those who use Irish or other languages outside the household context.

The Department of Celtic Studies at the University of Sydney offers courses in Modern Irish linguistics, Old Irish and Modern Irish language. The University of Melbourne houses a collection of nineteenth and early twentieth century books and manuscripts in Irish.

Australians continue to contribute poetry, fiction, and journalism to Irish-language literary magazines, both in print and on-line. There is also a widely distributed electronic newsletter in Irish called ''An Lúibín''.

The Irish language poet Louis De Paor lived with his family in Melbourne from 1987 to 1996 and published his first two poetry collections during his residence there. De Paor also gave poetry readings and other broadcasts in Irish on the Special Broadcasting Service (a network set up for speakers of minority languages). He was given scholarships by the Australia Council

The Australia Council for the Arts, commonly known as the Australia Council, is the country's official arts council, serving as an arts funding and advisory body for the Government of Australia. The council was announced in 1967 as the Austra ...

in 1990, 1991 and 1995.

Colin Ryan is an Australian whose short stories, set mostly in Australia and Europe, have appeared in the journals ''Feasta

''Feasta'' is an Irish-language magazine that was established in 1948. Its purpose is the furtherance of the aims of Conradh na Gaeilge (Gaelic League), an objective reflecting the cultural nationalism of the language movement, and the promotion ...

'', ''Comhar

''Comhar'' (; "partnership") is a prominent literary journal in the Irish language, published by the company Comhar Teoranta. It was founded in 1942, and has published work by some of the most notable writers in Irish, including Máirtín Ó Cadha ...

'' and ''An Gael

''An Gael'' is a quarterly literary magazine in the Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European l ...

''. He has also published poetry. Cló Iar-Chonnacht

Cló Iar-Chonnacht (CIC; ; "West Connacht Press") is an Irish language publishing company founded in 1985 by writer Micheál Ó Conghaile, a native speaker of Irish from Inis Treabhair in Connemara. He set the company up while still a student.

...

has published two collections of short stories by him: ''Teachtaireacht'' (2015) and ''Ceo Bruithne'' (2019). Two collections of his poetry have been published by Coiscéim: ''Corraí na Nathrach'' (2017) and ''Rogha'' (2022)

Julie Breathnach-Banwait is an Australian citizen of Irish origin living in Western Australia. She is the author of a collection called ''Dánta Póca'' (''Pocket Poems''), published by Coiscéim in 2020 and ''Ar Thóir Gach Ní'', published by Coiscéim in 2022. She has regularly published her poetry in ''The Irish Scene'' magazine in Western Australia. Her poetry has been published in ''Comhar'' (Ireland) and ''An Gael'' (New York) as well as on idler.ie. She is a native of Ceantar na nOileán

Ceantar na nOileán is an Irish-speaking district in the West of County Galway. There are about 2,000 people living in the area, located 56 km west of Galway city.

In 2016, 71.7% (1,474) of the population aged 3 years and over spoke Irish ...

in Connemara, County Galway

"Righteousness and Justice"

, anthem = ()

, image_map = Island of Ireland location map Galway.svg

, map_caption = Location in Ireland

, area_footnotes =

, area_total_km2 = ...

.

New Zealand

Irish migration to New Zealand was strongest in the 1840s, the 1860s (at the time of the gold rush) and the 1870s. These immigrants arrived at a time when theIrish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

was still widely spoken in Ireland, particularly in the south-west and west. In the 1840s the New Zealand Irish included many discharged soldiers: over half those released in Auckland (the capital) in the period 1845–1846 were Irish, as were 56.8% of those released in the 1860s. There was, however, a fall in Irish immigration from the 1880s. At first the Irish clustered in certain occupations, with single women in domestic service and men working as navvies or miners. By the 1930s Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

were to be found in government service, in transport and in the liquor industry, and assimilation was well advanced.

The use of Irish was influenced by immigrants' local origins, the time of their arrival and the degree to which a sense of Irishness survived. In 1894 the '' New Zealand Tablet'', a Catholic newspaper, published articles on the study of Irish. In 1895 it was resolved at a meeting in the city of Dunedin that an Irish-language society on the lines of the Philo-Celtic Society

The Philo-Celtic Society (Irish: Cumann Carad na Gaeilge) is a North American society founded as part of the Gaelic revival in 1873. Its aims are the promotion of the Irish language as a living tongue in America and throughout the world, and the r ...

of the United States should be established in New Zealand. Chapters of the Gaelic League were founded in both Milton

Milton may refer to:

Names

* Milton (surname), a surname (and list of people with that surname)

** John Milton (1608–1674), English poet

* Milton (given name)

** Milton Friedman (1912–2006), Nobel laureate in Economics, author of '' Free t ...

and Balclutha and items in Irish were published by the ''Southern Cross'' of Invercargill. In 1903 Fr. William Ganly, a native speaker of Connacht Irish from the Aran Islands who was very prominent in the Gaelic Revival

The Gaelic revival ( ga, Athbheochan na Gaeilge) was the late-nineteenth-century Romantic nationalism, national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including Irish folklore, folklore, Iri ...

in Melbourne, visited Milton, where he met a large number of Irish speakers.

The dwindling of Irish immigration, the decay of the Gaeltachtaí in Ireland and the passing of earlier generations were accompanied by a loss of the language. Interest is maintained among an activist minority.

Argentina

Between 40,000 and 45,000 Irish emigrants went to Argentina in the 19th century. Of these, only about 20,000 settled in the country, the remainder returning to Ireland or re-emigrating to North America, Australia and other destinations. Of the 20,000 that remained, between 10,000 and 15,000 left no descendants or lost any link they had to the local Irish community. The nucleus of the Irish-Argentine community therefore consisted of only four to five thousand settlers. Many came from a quadrangle on theLongford

Longford () is the county town of County Longford in Ireland. It has a population of 10,008 according to the 2016 census. It is the biggest town in the county and about one third of the county's population lives there. Longford lies at the meet ...

/ Westmeath border, its perimeter marked by Athlone

Athlone (; ) is a town on the border of County Roscommon and County Westmeath, Ireland. It is located on the River Shannon near the southern shore of Lough Ree. It is the second most populous town in the Midlands Region with a population of ...

, Edgeworthstown, Mullingar and Kilbeggan

Kilbeggan () is a town in the barony of Moycashel, County Westmeath, Ireland.

Geography

Kilbeggan is situated on the River Brosna, in the south of County Westmeath. It lies south of Lough Ennell, and Castletown Geoghegan, north of the boundar ...

.Murray, 'The Irish Road to South America', p.1, from McKenna, Patrick (1992), 'Irish Migration to Argentina' in: O’Sullivan, Patrick (ed.) ''The Irish World Wide: History, Heritage, Identity'', Vol. 1, London and Washington: Leicester University Press. It has been estimated that 43.35% of emigrants were from Westmeath, 14.57% from Longford and 15.51% from Wexford. Such migrants tended to be younger sons and daughters of the larger tenant farmers and leaseholders, but labourers also came, their fares paid by sheep-farmers seeking skilled shepherds.

Irish census figures for the 19th century give an indication of the percentage of Irish speakers in the areas in question. Allowing for underestimation, it is clear that most immigrants would have been English speakers. Census figures for Westmeath, a major source of Argentinian immigrants, show the following percentages of Irish speakers: 17% in the period 1831–41, 12% in 1841–51, and 8% in 1851–61.

In the 1920s, there came a new wave of immigrants from Ireland, most being educated urban professionals who included a high proportion of Protestants. It is unlikely that there were many Irish speakers among them.

The persistence of an interest in Irish is indicated by the fact that the Buenos Aires branch of the Gaelic League was founded as early as 1899. It continued to be active for several decades thereafter, but evidence is lacking for organised attempts at language maintenance into the present day, though the Fahy Club in Buenos Aires continues to host Irish classes.

See also

*Irish language

Irish ( Standard Irish: ), also known as Gaelic, is a Goidelic language of the Insular Celtic branch of the Celtic language family, which is a part of the Indo-European language family. Irish is indigenous to the island of Ireland and was ...

* Modern literature in Irish

Although Irish has been used as a literary language for more than 1,500 years (see Irish literature), and modern literature in Irish dates – as in most European languages – to the 16th century, modern Irish literature owes much of its populari ...

* ''Teastas Eorpach na Gaeilge

(TEG) or ''European Certificate in Irish'' is a set of examinations for adult learners of Irish. TEG is linked to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages ( Council of Europe, 2001). It examines four skills: speaking, listening, ...

''

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Irish Language Outside Ireland American literature in the Irish language Irish language Irish diaspora Diaspora languages Irish language outside Ireland Immigrant languages of the United States